Abstract

Chiral, nonracemic amines are valuable synthetic building blocks for diverse bioactive molecules. Asymmetric C─H amination via transition metal-catalyzed nitrene transfer (NT) is a popular strategy to access enantioenriched benzylamines, but many useful chemocatalysts for this transformation are based on precious metals or require elaborate ligands. Iron catalysts supported by simple ligands capable of asymmetric aminations of diverse sulfamates would be valuable but are surprisingly rare. Herein, we study features of the asymmetric iron-catalyzed NT of homo- and bis-homobenzylic sulfamates to better understand why the development of such reactions has proven challenging. Diverse parameters were examined, including ligand, iron source, oxidant, additive, and solvent. Reactions of the preoxidized iminoiodinane revealed some unexpected relationships between the pKa of acid additives and the enantiomeric ratio (er). Computational models show that radical rebound is the enantiodetermining step and highlight noncovalent interactions (NCIs) between the ligand and aryl ring of the substrate that drive the er. These insights, combined with experimental data, provide a foundation for the design of second-generation chemocatalysts for iron-catalyzed asymmetric C─H amidation via NT.

Keywords: Iron, nitrene transfer, asymmetric, amidation, C─H functionalization

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The asymmetric transformation of C─H bonds into new C─N bonds is a powerful method for the synthesis of amine motifs that occur frequently in bioactive natural products and pharmaceuticals.1,2 Transition metal-catalyzed nitrene transfer (NT)3 is a useful strategy to streamline access to enantioenriched amines; however, this approach would be even more attractive if chemocatalysts based on Earth-abundant metals, particularly iron, could be used without the need for azides or preoxidized nitrene precursors.

Enantioselective aminations of benzylic C─H bonds with a variety of nitrene precursors have been reported to form nitrogen-containing heterocycles and acyclic derivatives that include lactams,4-6 sulfamides,7-9 sulfamates,10-12 diamines,13 and amino alcohols.11,12,14,15 However, many of these reactions employ expensive transition metal chemocatalysts or sophisticated ligand scaffolds that are not commercially available. Given these limitations, the use of chiral Fe catalysts supported by non-heme ligands for asymmetric C─H aminations is very attractive.16 As an Earth-abundant metal, Fe is cheap, has minimal impact on human health, and is more sustainable and environmentally friendly compared to precious metals.17 Moreover, as a 3d metal, Fe has diverse oxidation states and a rich coordination chemistry that can promote a range of elementary mechanistic steps, including oxidative addition, reductive elimination, single-electron transfer, σ-bond metathesis, and, relevant to this work, group transfers.18

To date, the most successful examples of asymmetric Fe-catalyzed NT into C─H bonds involve the directed evolution of enzymes from nature.19 For example, Arnold and co-workers20 evolved P450 and P411 enzymes capable of promoting the enantioselective intermolecular NT into protic α-proton in carboxylic esters,20a benzylic20b,c and unactivated aliphatic20d C─H bonds, as well as intramolecular C─H aminations with organoazides. Arnold further demonstrated that cytochrome P411 variants and α-ketoglutarate-dependent iron enzymes can be evolved for nitrene C─H insertions.21 Fasan reported the use of evolved P450 enzymes with dioxazolones as the nitrene source for the stereoselective construction of β-, γ-, and δ-lactam rings.22 Finally, the Ward group employed an artificial metalloenzyme to catalyze enantioselective amidation via nitrene insertion into unactivated C(sp3)─H bonds.23

While racemic Fe-catalyzed NT reactions have been extensively studied,24 only a few examples of asymmetric NT reactions promoted by Fe-based chemocatalysts not based on enzymes (Scheme 1) are known. The Meggers group reported an enantioconvergent amination of C(sp3)─H bonds using an N4-supported Fe catalyst and preoxidized N-aroyloxyureas to generate chiral five-membered 2-imidazolidinones.25 The same group reported an elegant asymmetric, Fe-catalyzed directed α-amination of carboxylic acids to furnish novel amino acids.26 In these cases, a modified N4-ligand was employed where two of the pyridine arms were replaced with benzimidazoles. Che and co-workers described an enantioselective intramolecular C─H amination of aryl- and sulfonylazides with Fe─porphyrins under visible-light irradiation27 in up to 93% ee. Finally, the Chattopadhyay group reported an example of asymmetric intramolecular NT using a 1,2,3,4-tetrazole with a highly decorated chiral Fe─porphyrin complex to furnish an azaindoline in 46% ee.28 We were curious why these examples required use of an azide or preoxidized nitrene precursor, as opposed to treating sulfamates derived from readily available alcohols with a hypervalent iodine oxidant. These conditions are well-known to give high yields in achiral, Fe-catalyzed intramolecular C─H aminations,24e,j as well as in enantioselective reactions with metals that include Rh, Ru, and Mn.11,12 In this work, we report a systematic study of asymmetric Fe-catalyzed NT of homo- and bis-homobenzylic sulfamates that merges experiment, mechanism, and computation to better understand the challenges in this chemistry, as well as the roles of diverse parameters that impact ee. We expect these insights will inform future designs of new chemocatalysts for Fe-catalyzed asymmetric intra- and intermolecular NT.

Scheme 1. Reported Fe-Based Chemocatalysts for Asymmetric C─H Nitrene Transfer.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Initial studies commenced using bis-homobenzylic sulfamate 1a in the presence of Fe(OTf)2 and various nitrogen-based ligands, most of which are commercially available (Table 1). Treatment of 1a with 10 mol% Fe(OTf)2 and 15 mol% of the C2-symmetric chiral bis(oxazoline) (BOX) ligand L1 in the presence of 4 Å MS (50 mg), PhI(OPiv)2 (1.2 equiv) in MeCN at 70 °C afforded the desired product 2a in 7% yield and 54:46 er (entry 1). Changing the ligand to the chiral pyridine oxazoline (PyOX) L2 gave a slight improvement in both yield and er to afford 2a in 30% yield and 42:58 er (entry 2). A variety of other nitrogen-based bidentate ligands gave lower reactivities (SI). However, tridentate pyridine-2,6-bisoxazoline (PyBOX) ligand L3 furnished 2a in 94% isolated yield and 79:21 er (entry 3). Inspired by the significant improvement in both yield and er using L3, various commercially available PyBOX ligands were explored (see the Supporting Information (SI) for details); however, no further improvements were noted. From these initial results, it appeared that the rigid indane moiety of L3 was key to both the reactivity and enantioselectivity.

Table 1.

Initial Exploration of the Asymmetric Amination of Benzylic C(sp3)─H Bonds

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrya | Oxidant | L* | Temp (°C) | Yieldb (%) | er c |

| 1 | PhI(OPiv)2 | L1 | 70 | 7 | 54:46 |

| 2 | PhI(OPiv)2 | L2 | 70 | 30 | 42:58 |

| 3 | PhI(OPiv)2 | L3 | 25 | 93 (94)f | 79:21 |

| 4 | PhI(OPiv)2 | L4 | 25 | 34 | 51:49 |

| 5 | PhI(OPiv)2 | L5 | 25 | 76 | 75:25 |

| 6 | PhI(OPiv)2 | L6 | 25 | 67 | 80:20 |

| 7 | PhI(OPiv)2 | L7 | 25 | 66 | 79:21 |

| 8 | PhI(OPiv)2 | L8 | 25 | 33 | 75:25 |

| 9 | PhI(OPiv)2 | L9 | 25 | 49 | 60:40 |

| 10 | PhI(OPiv)2 | L10 | 25 | 64 | 76:24 |

| 11 | PhI(OPic)2 | L11 | 25 | 54 | 76:24 |

| 12 | PhI(OAc)2 | L3 | 25 | 86 | 76:24 |

| 13 | PhIO | L3 | 25 | 46 | 75:25 |

| 14 | PhI(OTFA)2 | L3 | 25 | 34 | 59:41 |

| 15d | PhI(OPiv)2 | L3 | −5 | 43 | 88:12 |

| 16d | PhI(OPiv)2 | L3 | −10 | 22 | 89:11 |

| 17d,e | PhI(OPiv)2 | L3 | −10 | 48 (49)f | 88:12 |

Procedure: A solution of Fe(OTf)2 and L* in MeCN was treated with 4 Å MS (50 mg), 1a (1 equiv), and oxidant (1.2 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred for 18 h.

Determined by 1H NMR with 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene as internal standard.

Determined by HPLC.

Reaction for 72 h.

Portionwise addition of catalyst (20 mol%).

Isolated yield.

With a promising L3 ligand scaffold in hand, systematic modifications to the indane scaffold were explored, with the goal of employing computational studies to both rationalize experimental results and improve er. First, the backbone of L3 was systematically modified at C7, C6, and the position para to the pyridine nitrogen. Introducing a methyl group at C7 in L4 led to lower conversion and a complete loss of er (Table 1, entry 4), presumably due to steric hindrance between the sulfamate and ligand. Installing a Br group at the C7 position in L5 recovered some of the er (entry 5); however, results were inferior to those in L3. The influence of sterics at the C6 position of the indane PyBOX ligand was examined next. While modifications at C6 with aryl groups gave no improvement in er (see the SI for details), introduction of an isopropyl group in L6 gave er (entry 6) similar to that of L3. Unfortunately, a further increase in the steric demand resulted in decreased selectivity (entries 7–9). Modifications at the para position of the pyridine moiety in L10–L11 also did not yield further improvements (entries 10–11). These disappointing results prompted us to investigate other parameters in addition to the ligand identity that might be tuned to increase er.

Moving ahead with L3 as the best ligand, the impact of the hypervalent iodine oxidant on er was examined. Interestingly, the oxidant identity played a key role in determining both the yield and the er. While PhI(OAc)2 gave only a slight reduction in yield and er (entry 12), the yield was substantially decreased using PhIO (entry 13). The impact on yield and er using PhI(OTFA)2 was even more striking (entry 14), with er dropping to only 59:41. This was an unexpected result, suggesting that the counteranion of the oxidant is important to the reaction success; this effect was examined in more detail (Scheme 3, vide infra). The impact of temperature on the yield and er of the NT was explored by using PhI(OPiv)2 as the optimal commercially available oxidant. Time course monitoring experiments at rt (see SI for details) implied that the desired NT occurs at a faster rate than competing oxidative degradation of the Fe catalyst. While conducting the reaction at lower temperatures would be expected to increase the er, competing catalyst degradation at extended reaction times could decrease conversion. Indeed, while reaction at −5 °C noticeably improved the er to 88:12, 2a was obtained in only 43% yield (entry 15). A decrease to −10 °C afforded 22% yield with little impact on er (entry 16); however, portion-wise catalyst addition (total of 20 mol%) improved the yield of 2a to 49% in 88:12 er (entry 17). However, given the extended reaction times at low temperatures, the reaction scope was first explored at rt, with the option for further optimization of promising er.

Scheme 3. Investigation on Oxidant Effect via Fe Catalysis with Iminoiodinane.

aThe Fe salt (10 mol%), L3 (15 mol%), 4 Å MS (50 mg), and the acid additive (0–1 equiv) in MeCN were treated with iminoiodinane (1 equiv, 0.100 mmol) at 25 °C for 18 h. bIn situ generated with Fe(L3)Cl2 (10 mol%) and AgOPiv (20 mol%). cCrude NMR yield determined with 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene as the internal standard. dDetermined by HPLC analysis. e38% isolated yield. fFe(OTf)2 was used. g74% isolated yield.

Exploration of the scope of the asymmetric NT (Scheme 2) showed that both the yield and er are sensitive to the electronic properties of the aromatic group. The presence of electrondonating groups in 1b and 1c gave excellent yields of 2b and 2c but lower er as compared to the parent precursor 1a. In contrast, electron-withdrawing groups in 1d–1f furnished lower overall yields and conversions to 2d–2f but with no obvious impact on er. Moving the Me and OMe groups on the ring from a para to a meta position was instructive. While m-Me-substituted 1g afforded 2g in 82% yield with only slightly higher er (78:22 er) compared to 2c (76:24 er), m-OMe 1h furnished 2h in much better er (79:21 er) compared to 2b (68:32 er). The sensitivity of the er to electronic effects may signal a potential C─H─π interaction in the enantiodetermining transition state, a possibility that was examined in computational studies (Figures 1-3, vide infra). A 3,5-disubstitution on the aromatic ring (1i and 1j) was attempted to determine if further improvement in er could be achieved; however, the er decreased compared to those of the monosubstituted 2d and 2h. This implies a fine balance between electronic and steric interactions. The same observation was noted with ortho-substitution on the aryl ring, as 1k afforded 2k in 62% yield with 61:39 er, but installation of a smaller o-F substituent gave 2l in a similar yield and slightly improved er (66:34 er).

Scheme 2. Scope for Asymmetric Iron-Catalyzed Amination of Benzylic C─H Bondsa.

a Procedure: A solution of Fe(OTf)2 (10 mol%) and L3 (15 mol%) with 4 Å MS (50 mg) and 1 (0.100 mmol, 1 equiv) in MeCN (total concentration of 0.05 M) was treated with PhI(OPiv)2 (1.2 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 18 h. bIsolated yield. cDetermined by HPLC analysis.dAbsolute stereochemistry was determined by obtaining an X-ray crystal structure of 2d (see the SI). eDetermined by crude NMR. frac-L3 was used. gMinor diastereomer was not observed. h53% crude NMR yield with 77:23 er when L8 was used instead of L3.

Figure 1.

Hydrogen atom transfer transition states with different Fe─nitrenoid complexes. All Gibbs free energies are in kcal/mol, with respect to the most stable Fe─nitrenoid complex 7.

Figure 3.

Enantioselectivity-determining radical rebound transition states and ligand effects on enantioselectivity.

The impact of substitution in the tether on the yield and er of the NT was explored. The tertiary sulfamate substrate 1m afforded 2m in near-quantitative yield in 72:28 er, while the β-gem-Me of 1n furnished 2n in lower yield and a higher 77:23 er. Interestingly, carrying out the NT reaction using secondary alcohols (S)-1o and (R)-1p to furnish 2o and 2p highlighted the ability of (L3)Fe(OTf)2 to provide access to both the syn- and anti-aminoalcohol precursors. (S)-1o represents a matched case between the catalyst and substrate to give high dr for the syn product 2o in near-quantitative yield. In contrast, the mismatched case between (R)-1p and the catalyst gave no selectivity between the syn and anti-diastereomers of 2p. This is significant, as nearly all catalysts for the intramolecular NT of sulfamates to furnish the six-membered heterocyclic products give only the syn-diastereomer. In addition, the observed diastereomeric ratio for 2o and 2p suggested a chair-like TS in the matched case, where both Ph and Me groups reside in equatorial positions. In contrast, the mismatched case is expected to have a less favorable TS geometry. The use of rac-L3, bearing a Me substituent at the β-position of the tether, afforded 2q in 76% yield with excellent anti-selectivity.

Finally, the optimized conditions were tested for asymmetric amidations of other activated benzylic C─H bonds. Interestingly, the NT reaction to give enantioenriched 1,2-amino-alcohols (1r–1t) appeared to be insensitive to the electronics of the aromatic ring, affording 2r–2t in similar yield and er. Notably, employing L8 instead of L3 improved the er, albeit with a much lower conversion. Asymmetric NT of 1u bearing a tertiary benzylic C─H bond afforded 2u in 83% yield in 61:39 er, highlighting the potential for stereoablation at a racemic chiral carbon, followed by resetting of the chirality via catalyst control. A 2-naphthyl-substituted precursor 1v and a Boc-protected indole 1w gave 2v in 73% yield with 77:23 er and 2w in 75% yield with 79:21 er, respectively. Even an electron-poor ortho-Me substituted pyridine substrate 1x tolerated the reaction conditions to afford 2x in 40% yield and 75:25 er.

Several puzzling effects were encountered during optimization studies; for example, the oxidant influenced both the yield and er of the NT. Differences in reaction outcome could be attributed to the relative oxidation potentials of diverse hypervalent iodines or to competition between the oxidation of the sulfamate to iminoiodinane and catalyst degradation. Prestirring (L3)Fe(OTf)2 with PhI(OPiv)2 prior to conducting the reaction gave only 6% conversion to 2a, indicating that catalyst degradation is indeed a concern. In our previous extensive investigations of asymmetric Ag-catalyzed NT, iodosobenzene (PhIO) proved to be the optimal oxidant, while PhI(OAc)2 and PhI(OPiv)2 resulted in reduced control over the site-selectivity of the NT event and a lower er. However, in the case of iron catalysis, soluble oxidants were superior in terms of conversion and yield. To eliminate the effect of the oxidant on the reaction outcome, 1a was preoxidized to the iminoiodinane 3 and purified. To our surprise, subjecting 3 to typical reactions conditions in the absence of oxidant (Scheme 3A) with Fe(L3)(OTf)2 gave 2a in a decreased 37% yield, but more interestingly, in only 20% ee, as compared to 59% ee for the reaction conducted under standard conditions. We initially hypothesized that perhaps an anion exchange between the Fe complex and the hypervalent iodine counteranion played a role in the catalysis; however, reactions employing either Fe(OAc)2 or Fe(OPiv)2 resulted in no reaction. While the addition of 1 equiv of CF3CO2H showed similar yield and er to the use of PhI(OTFA)2 as the oxidant, the addition of 1 equiv of acetic acid to 3 afforded 2a in 73% yield and 59% ee (Scheme 3B), similar to the result using PhI(OAc)2 as the oxidant with 1a. Finally, the addition of 1 equiv of pivalic acid to the reaction of 3 increased the ee to 67%, similar to results in the reaction of 1a with PhI(OPiv)2. These results imply that in addition to the pKa of the acid produced from the hypervalent iodine oxidant, its steric bulk may have an impact on the er. Thus, iminoiodinane 3 was treated with Fe(L3)(OTf)2 in the presence of 1 equiv of carboxylic acids of differing pKa and steric bulk (Scheme 3C). Interestingly, a correlation between the pKa of the acid additive and the observed ee was noted, but no correlation with the steric bulk of the acid was seen. Weak acids with pKa values of ~4.94 showed the highest ee, while acid additives with pKa values higher or lower than 4.9 displayed diminished ee. Other non-carboxylic acid additives were tested, but no correlation between the pKa and ee was noted (details and additives in the SI). Based on these results, we postulated that the role of the oxidant was not limited solely to forming the intermediate iminoiodinane, leading to an incomplete mechanistic picture. The use of different anions may also impact the solubility of the catalyst, and this possibility cannot be ruled out.

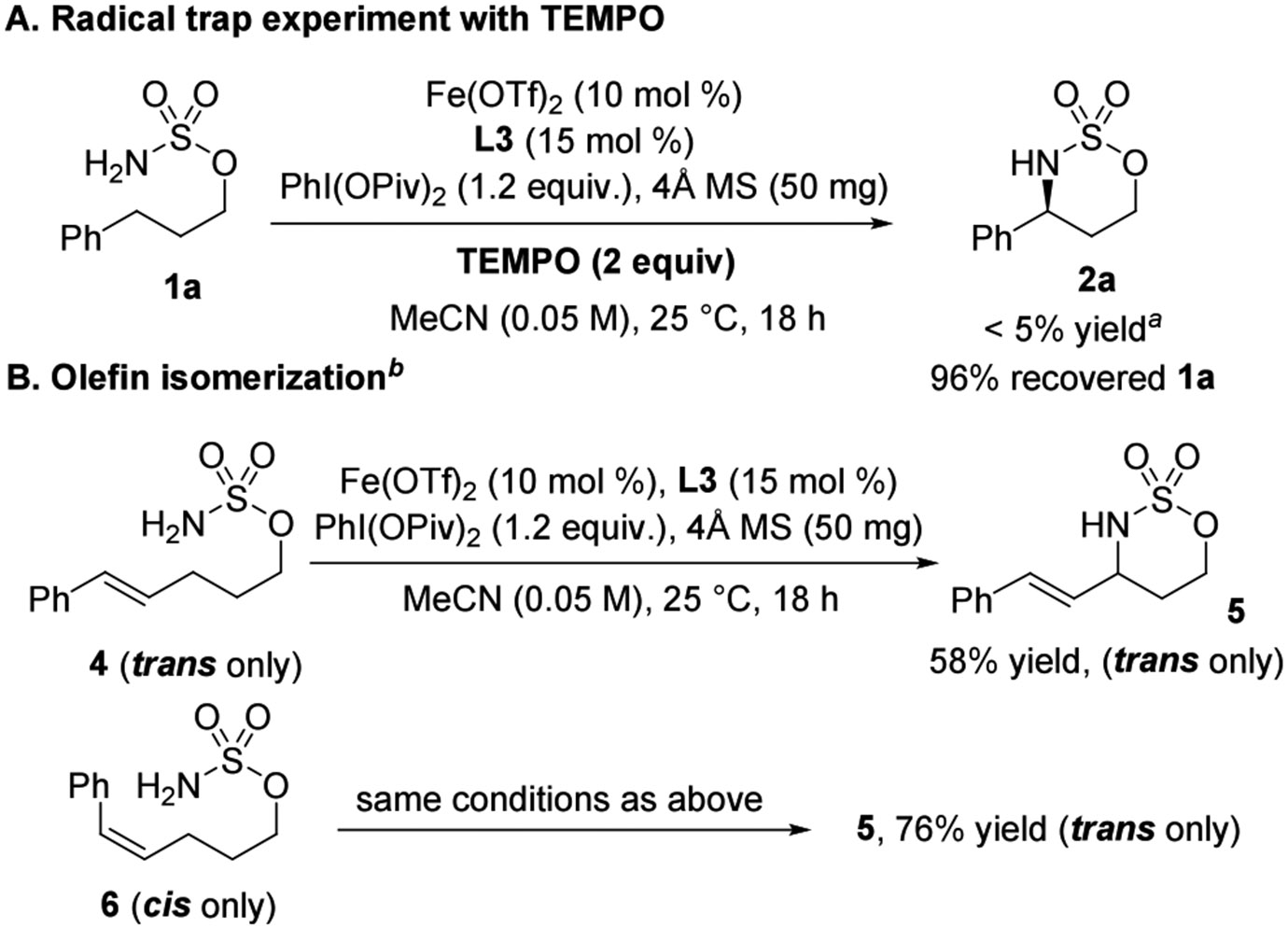

Fe-catalyzed NT reactions are postulated to proceed via a stepwise mechanism that involves a hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) to form a radical intermediate, followed by rapid radical rebound to form the C─N bond of the product.29 In our chemistry, the addition of TEMPO (2 equiv) to the reaction mixture under standard conditions hampered the C─H amination, resulting in the recovery of 96% 1a (Scheme 4A) and suggesting the likelihood of a radical intermediate. To further elucidate the details of the formation of postulated radical intermediates, an olefin isomerization experiment was conducted. While trans-alkene 4 furnished the trans isomer of 5 in 58% yield, reaction of cis-alkene 6 gave the trans isomer of 5 in 76% yield. The complete cis-to-trans isomerization observed in the reaction of the cis-alkene precursor to the product suggested the intermediacy of a long-lived radical (Scheme 4B) in these reactions.30

Scheme 4. Mechanistic Investigations.

aDetermined by crude 1H NMR using mesitylene as the internal standard. bIndicated yields are isolated yields.

To elucidate the rate- and selectivity-determining steps of the enantioselective NT reaction, kinetic isotope effect (KIE) experiments were conducted. Intramolecular KIE experiments (Scheme 5A) gave a KIE value of 1.56 ± 0.02 using the monodeuterated sulfamate [D]1-1a and a slightly larger value of 1.75 ± 0.01 using the preoxidized monodeuterated iminoiodinane [D]1-3. Both of these values are significantly smaller than the reported KIE values for most other Fe-catalyzed intramolecular NT reactions, which are typically on the order of 3–4.24h,28

Scheme 5. Intra- and Intermolecular KIE Experiments.

aee was determined by molecular rotational resonance spectroscopy. bDetermined by crude NMR with 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene as internal standard. cAverage isolated yield. dee was based on [D]1-1a. eConversion was determined based on D-labeled sulfamate obtained by decomposition of D-labeled iminoiodinane.

Competitive intermolecular experiments to study the KIE were also conducted (Scheme 5B). The KIE value using a 1:1 mixture of sulfamate 1a and sulfamate [D]2-1a in the presence of PhI(OPiv)2 (0.5 equiv) was measured as 1.00 ± 0.06, while the KIE value employing a 1:1 mixture of the iminoiodinane 3 and the iminoiodinane [D]2-3 was determined to be 1.07 ± 0.003. The absence of an isotope effect for reaction of 1a and [D]2-1a clearly indicates that in this case C─H bond cleavage does not occur in the rate-determining step (RDS); however, the small observed KIE using the iminoiodinane precursors does not provide conclusive evidence when the C─H bond cleavage occurs. The lack of a KIE in these experiments would rule out the C─H bond cleavage occurring during the RDS, but observation of a KIE does not mean that C─H bond cleavage must occur during this step.

Values obtained from the intramolecular and competitive intermolecular KIE experiments suggest that the HAT step is unlikely to be the RDS. We postulated that formation of the iminoiodinane might be the RDS in this Fe-catalyzed NT; as precedent, Du Bois and co-workers reported formation of an iminoiodinane was the RDS in a NT reaction catalyzed by a dinuclear Rh(II) complex.31 However, a firm conclusion as to whether iminoiodinane formation is rate-determining cannot be drawn from the KIE values obtained in our Fe-catalyzed NT of sulfamate [D]1-1a and iminoiodinane [D]1-3. This is because intramolecular competition experiments measure differences in product distributions resulting from differences in the rates of irreversible C─H bond cleavage; this can give rise to a KIE, even if that step is not rate-determining. Thus, iminoiodinane formation could still be rate-determining,32,33 with C─H bond cleavage occurring in the product-determining step instead of the RDS.

Computational Explorations of Asymmetric Iron-Catalyzed C─H Bond Amination Using PyBOX Ligands.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to gain insights into the mechanism and the factors that control the ee of our Fe-catalyzed benzylic C─H amination.34 Calculations were carried out with the sulfamate 1a as a model substrate at the M0635/SDD36-6-311+G(d,p)/SMD37-(CH3CN)//B3LYP-D3(BJ)38/SDD-6-31G(d) level of theory. We first considered the relative stability and reactivity of several Fe─nitrenoid complexes to identify the catalytically active species involved in the NT (Figure 1).39 All four Fe─nitrenoid species (7, 7a–7c) favor the quintet spin state.40 The closed-shell singlet and triplet states are more than 51.2 and 24.4 kcal/mol less stable, respectively (Figure S1). Among the four Fe─nitrenoid complexes that were considered, the C2-symmetric octahedral trans-ditriflate complex 7 is the most stable and requires the lowest activation free energy in intramolecular hydrogen atom transfer via TS1-R and TS1-S (ΔG⧧ = 4.0 and 2.8 kcal/mol with respect to 7). In 7, the nitrene moiety is coplanar with the PyBOX ligand (L3). The cis-ditriflate isomer 7a is 7.1 kcal/mol less stable than 7 and requires higher barriers for intramolecular HAT (ΔG⧧ = 7.3 and 8.1 kcal/mol for TS1a-R and TS1a-S with respect to 7). Monocationic square-based pyramidal Fe─nitrenoid complexes 7b and 7c were also considered (Figure 1B). Both 7b and 7c are less stable than 7 and require higher activation free energies for HAT. Taken together, our DFT calculations indicate that the catalytically active Fe─nitrenoid species in NT is C2-symmetric octahedral complex 7.

Next, we computed the reaction free energy profiles leading to the two enantiomeric NT products from Fe─nitrenoid 7 (Figure 2). The initial hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) step prefers abstraction from the pro-S benzylic C─H bond via TS1-S (ΔG⧧ = 2.8 kcal, Figure 1A). Although the HAT is exergonic and irreversible, the resulting benzylic radical intermediate 8-S can undergo rapid interconversion with conformer 8-R, which points the opposite π-face of the prochiral radical center toward the Fe─sulfamate. Thus, the enantioselectivity-determining step is expected to be the subsequent intramolecular radical rebound (TS2-S vs TS2-R) that forms the new C─N bond of the product. The computed Gibbs free energy barriers of radical rebound transition states TS2-S and TS2-R are 3.5 and 5.2 kcal/mol with respect to 8-S, respectively. TS-2S and TS-2R both have a chair-like six-membered ring with the Ph group placed at the equatorial position. Ring-flip conformers placing the Ph at the axial position were located and were found to be higher in energy (SI, Figure S4). The computed activation Gibbs free energy difference of 1.7 kcal/mol indicates good enantioselectivity. Although the computed ΔΔG⧧ overestimates the ee compared with experiment (95:5 er vs 79:21 er), the predicted preference for the (S)-product is consistent with the experimentally observed major enantiomer.

Figure 2.

Computed reaction free energy profiles of the Fe-catalyzed asymmetric intramolecular nitrene transfer with an L3-supported Fe catalyst.

We next analyzed the ligand–substrate noncovalent interactions (NCIs) that contribute to the greater stability of TS-2S as compared to TS-2R (Figure 3A). When the nitrogen approaches the Si-face of the benzylic radical in TS2-S, the equatorial Ph group is placed close to the indane moiety on PyBOX ligand L3 in the top-left quadrant. This is evidenced by a shorter distance between the indane C─H bond and the centroid of the benzene ring (2.28 and 2.40 Å in TS2-S and TS2-R, respectively). This indicates more favorable ligand–substrate NCIs in TS2-S compared to TS2-R that contribute to the lower energy of TS2-S in relation to TS2-R. We next computed the radical rebound transition states with the 7-Me-substituted PyBOX ligand L4 (Figure 3B). The computed activation free energy difference between the two transition states leading to the two enantiomers (TS2-S′ and TS2-R′) is only 0.7 kcal/mol, which is consistent with the decreased er that is observed experimentally (51:49 er with L4 compared to 79:21 er with L3). Using the more sterically hindered ligand L4 leads to longer C─N bond distances in the transition states (2.71 and 3.01 Å) compared to those with L3 (2.61 and 2.83 Å in TS2-S and TS2-R). In the earlier transition states, the NCIs between the Ph on the substrate and the indane moiety on the ligand become weaker in both TS2-S′ and TS2-R′, as evidenced by the slightly longer C─H⋯π distances compared to those in TS2-S and TS2-R. In addition, the C7-Me substituent causes steric clashing with the sulfamate oxygen atoms. This steric effect is more pronounced in TS2-S′ that leads to the major enantiomer, which also contributes to the diminished enantioselectivity observed with this substrate.

Computational studies to better understand the impact of the carboxylic acid additive on the enantioselectivity of the C─H amination are also of interest to us but will be a focus of future efforts. We are exploring other ligand scaffolds and other potential mechanisms and seeking to both experimentally and computationally probe further details of structure and speciation of Fe complexes in solution.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we have reported efforts to identify simple Fe catalysts for asymmetric nitrene transfer reactions of bis-homobenzylic and homobenzylic sulfamates to furnish enantioenriched precursors to 1,3- and 1,2-aminoalcohols. The design of non-heme ligands to support iron catalysts promoting NT in high er proved challenging, and the amidation was highly sensitive to multiple parameters. Notably, the unexpected relationship between the pKa of acid additives and the enantioselectivity provided valuable mechanistic insights. Computational studies identified radical rebound as the enantiodetermining step of the mechanism and highlighted the role of noncovalent interactions between the ligand and substrate in driving the selectivity. These findings establish a foundation for next-generation catalyst design that will enable more sustainable NT processes using iron-based catalysts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Chemicals were obtained from commercial sources and were used as received unless otherwise specified (see the SI for more details).

Methods.

An oven-dried 4 mL vial was charged with Fe(OTf)2 (3.5 mg, 0.010 mmol, 10 mol%) and L3 (5.9 mg, 0.015 mmol, 15 mol%), followed by addition of MeCN (1 mL) in a drybox equipped with slow-flow of N2. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h and then 4 Å MS (50 mg) were added in a single portion, followed by the addition of the sulfamate (0.100 mmol, 1 equiv) in MeCN (1 mL, total concentration of solvent, 0.05 M) and PhI(OPiv)2 (48.8 mg, 0.120 mmol, 1.2 equiv) in a single portion. The reaction mixture was stirred for 18 h at 25 °C and then filtered through a pad of silica gel with EtOAc (100 mL) and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to afford the desired product (see the SI for more details).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Prof. Brooks H. Pate at the University of Virginia and Dr. Reilly E. Sonstrom at BrightSpec Inc. for performing EE measurements on the IsoMRR instrument. Dr. Heike Hofstetter at UW-Madison is thanked for help with NMR techniques. Dr. Martha M. Vestling at UW-Madison is thanked for mass spectrometry characterization. UCSF Chimera is developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (supported by NIH P41-GM103311).

Funding

J.M.S. is grateful to NSF (CHE-1954325) and the University of Wisconsin Vilas Associates Award for financial support of this research. The Paul Bender Chemistry Instrumentation Center includes: Thermo Q Exactive Plus by NIH 1S10 OD020022-1; Bruker Avance-500 by a generous gift from Paul J. and Margaret M. Bender; Bruker Avance-600 by NIH S10 OK012245; Bruker Avance-400 by NSF CHE-1048642. P.L. acknowledges the NSF (CHE-2247505) for financial support. DFT calculations were carried out at the University of Pittsburgh Center for Research Computing and the Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS) program, supported by NSF award numbers OAC-2117681 and OAC-2138259. J.R.C. is grateful to the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health for research support under Award R35 GM147441.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.5c00222.

Characterization data, optimization tables, additional substrates/catalysts, and details of computational methods (PDF)

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the NIH.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Kyeongdeok Seo, Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, United States; Infectious Diseases Therapeutic Research Center, Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology, Daejeon 34114, Republic of Korea.

Yu Zhang, Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

Tuan Anh Trinh, Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, United States.

Jed Kim, Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, United States.

Lihan Qi, Department of Chemistry, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996, United States.

Ilia A. Guzei, Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, United States

Joseph R. Clark, Department of Chemistry, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996, United States

Peng Liu, Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

Jennifer M. Schomaker, Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Heravi M; Zadsirjan V Prescribed Drugs Containing Nitrogen Heterocycles: An Overview. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 44247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ricci A. Amino Group Chemistry: From Synthesis to the Life Sciences; Wiley: Weinheim, 2008; p 55. [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) For selected reviews, see: Ju M; Schomaker JM Nitrene Transfer Catalysts for Enantioselective C─N Bond Formation. Nat. Rev. Chem 2021, 5, 580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Uchida T; Hayashi H Recent Development in Asymmetric C-H Amination via Nitrene Transfer Reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2020, 2020, 909. [Google Scholar]; (c) Collet F; Lescot C; Dauban P Catalytic C-H Amination: The Stereoselectivity Issue. Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Park Y; Chang S Asymmetric Formation of γ-Lactams via C─H Amination Enabled by Chiral Hydrogen-Bond-Donor Catalysts. Nat. Catal 2019, 2, 219. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Xing Q; Chan CM; Yeung YW; Yu WY Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Enantioselective γ-Lactams Formation by Intramolecular C-H Amination of 1,4,2-Dioxazol-5-Ones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kim S; Song SL; Zhang J; Kim D; Hong S; Chang S Regio- and Enantioselective Catalytic δ-C-H Amidation of Dioxazolones Enabled by Open-Shell Copper-Nitrenoid Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2023, 145, 16238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Li C; Lang K; Lu H; Hu Y; Cui X; Wojtas L; Zhang XP Catalytic Radical Process for Enantioselective Amination of C(sp3)─H Bonds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 16837. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lang K; Torker S; Wojtas L; Zhang XP Asymmetric Induction and Enantiodivergence in Catalytic Radical C-H Amination via Enantiodifferentiative H-Atom Abstraction and Stereoretentive Radical Substitution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 12388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lang K; Li C; Kim I; Zhang XP Enantioconvergent Amination of Racemic Tertiary C─H Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 20902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Nasrallah A; Lazib Y; Boquet V; Darses B; Dauban P Catalytic Intermolecular C(sp3)-H Amination with Sulfamates for the Asymmetric Synthesis of Amines. Org. Process Res. Dev 2020, 24, 724. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zalatan DN; Du Bois J A chiral rhodium carboxamidate catalyst for enantioselective C-H amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Milczek E; Boudet N; Blakey S Enantioselective C-H Amination Using Cationic Ruthenium(II)-Pybox Catalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2008, 47, 6825. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang J; Chan PWH; Che C-M Enantioselective intramolecular amidation of sulfamate esters catalyzed by chiral manganese(III) Schiff-base complexes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 5403. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lang K; Torker S; Wojtas L; Zhang XP Asymmetric Induction and Enantiodivergence in Catalytic Radical C-H Amination via Enantiodifferentiative H-Atom Abstraction and Stereoretentive Radical Substitution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 12388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Reddy RP; Davies HM Dirhodium tetracarboxylates derived from adamantylglycine as chiral catalysts for enantioselective C-H aminations. Org. Lett 2006, 8, 5013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Zhou Z; Tan Y; Shen X; Ivlev S; Meggers E Catalytic Enantioselective Synthesis of β-Amino Alcohols by Nitrene Insertion. Sci. China Chem 2021, 64, 452. [Google Scholar]

- (16).For selected reviews on iron-catalyzed nitrene transfer reactions, see:Liu Y; Shing K-P; Lo VK-Y; Che C-M Iron- and Ruthenium-Catalyzed C-N Bond Formation Reactions. Reactive Metal Imido/Nitrene Intermediates. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 1103.Casnati A; Lanzi M; Cera G Recent Advances in Asymmetric Iron Catalysis. Molecules 2020, 25, 3889. Gopalaiah K. Chiral Iron Catalysts for Asymmetric Synthesis. Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 3248. Liu Y; You T; Wang T-T; Che C-M Iron-Catalyzed C-H Amination and its Application in Organic Synthesis. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 130607.Possenti D; Olivo G Homogeneous Iron-Catalyzed C-H Amination. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, No. e202400353.

- (17).(a) Bolm C. A new iron age. Nat. Chem 2009, 1, 420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Feig AL; Lippard SJ Reactions of Non-Heme Iron(II) Centers with Dioxygen in Biology and Chemistry. Chem. Rev 1994, 94, 759. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wang P; Deng L Recent Advances in Iron-Catalyzed C-H bond Amination via Iron Imido Intermediate. Chin. J. Chem 2018, 36, 1222. [Google Scholar]

- (19).For recent reviews on Fe-catalyzed NT with enzymes from nature, see:Xu W-N; Gao Y-D; Su P; Huang L; He Z-L; Yang L-C Progress in Enzyme-Catalyzed C(sp3)-H Amination. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 14139.Coin G; Latour J-M Nitrene transfers mediated by natural and artificial iron enzymes. J. Inorg. Biochem 2021, 225, 111613. Yang Y; Arnold FH Navigating the Unnatural Reaction Space: Directed Evolution of Heme Proteins for Selective Carbene and Nitrene Transfer. Acc. Chem. Res 2021, 54, 1209. Ren X; Fasan R Engineered and artificial metalloenzymes for selective C-H functionalization. Curr. Opin. Green. Sust 2021, 31, 100494.

- (20).(a) Alfonzo E; Hanley D; Li Z-Q; Sicinski KM; Gao S; Arnold FH Biocatalytic Synthesis of α-Amino Esters via Nitrene CH insertion. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2024, 146, 27267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Das A; Long Y; Maar RR; Roberts JM; Arnold FH Expanding Biocatalysis for Organosilane Functionalization: Enantioselective Nitrene Transfer to Benzylic Si-C-H Bonds. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 148. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gao S; Das A; Alfonzo E; Sicinski K; Rieger D; Arnold FH Enzymatic Nitrogen Incorporation Using Hydroxylamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2023, 145, 20196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Athavale SV; Gao S; Das A; Mallojjala SC; Alfonzo E; Long Y; Hirschi JS; Arnold FH Enzymatic Nitrogen Insertion into Unactivated C-H bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 19097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Qin Z-Y; Gao S; Zou Y; Liu Z; Wang JB; Houk KN; Arnold FH Biocatalytic Construction of Chiral Pyrrolidines and Indolines via Intramolecular C(sp3)-H Amination. ACS Cent. Sci 2023, 9, 2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Goldberg NW; Knight AM; Zhang RK; Arnold FH Nitrene Transfer Catalyzed by a Non-Heme Iron Enzyme and Enhanced by Non-Native Small-Molecule Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 19585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Roy S; Vargas DA; Ma P; Sengupta A; Zhu L; Houk KN; Fasan R Stereoselective construction of β-, γ- and δ-lactam rings via enzymatic C-H amidation. Nat. Catal 2024, 7, 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Yu K; Zou Z; Igareta NV; Tachibana R; Bechter J; Kohler V; Chen D; Ward TR Artificial Metalloenzyme-Catalyzed Enantioselective Amidation via Nitrene Insertion in Unactivated C(sp3)-H bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2023, 145, 16621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).For selected examples of iron-catalyzed C─N bond formation, see:Fan J; Wang Y; Hu X; Liu Y; Che C-M Iron porphyrin-catalysed C(sp3)-H amination with alkyl azides for the synthesis of complex nitrogen-containing compounds. Org. Chem. Front 2023, 10, 1368.Wang J; Xiao R; Lin Z; Zheng Z; Zheng K Mechanistic and chemoselective investigations on nitrene transfer reactions mediated by a novel iron-mesoionic carbene catalyst. Mol. Catal 2023, 536, 112922.Kweon J; Kim D; Kang S; Chang S Access to β-lactams via Iron-Catalyzed Olefin Oxyamidation Enabled by the π-Accepting Phthalocyanine ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 1872. Kweon J; Chang S Highly Robust Iron Catalyst System for Intramolecular C(sp3)-H Amidation Leading ton γ-Lactams. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2021, 60, 2909.Liu W; Zhong D; Yu C-L; Zhang Y; Wu D; Feng Y-L; Cong H; Lu X; Liu W-B Iron-Catalyzed Intramolecular Amination of Aliphatic C-H bonds of Sulfamate Esters with High Reactivity and Chemoselectivity. Org. Lett 2019, 21, 2673. Shing K-P; Liu Y; Cao B; Chang X-Y; You T; Che C-M N-Heterocyclic Carbene Iron(III) Porphyrin-Catalyzed Intramolecular C(sp3)-H Amination of Alkyl Azides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 11947.Hennessy ET; Betley TA Complex N-Heterocycle Synthesis via Iron-Catalyzed, Direct C-H Bond Amination. Science 2013, 340, 591. Paradine SM; White MC Iron-Catalyzed Intramolecular Allylic C-H Amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 2036. Breslow R; Gellman SH Intramolecular nitrene carbon-hydrogen insertions mediated by transition-metal complexes as nitrogen analogs of cytochrome P-450 reactions.J. Am. Chem. Soc 1983, 105, 6728.Zhong D; Wu D; Zhang Y; Lu Z; Usman M; Liu W; Lu X; Liu W-B Synthesis of Sultams and Cyclic N-Sulfonyl Ketimines via Iron-Catalyzed Intramolecular C─H Amidation. Org. Lett 2019, 21, 5808.

- (25).Cui T; Ye C-X; Thelemann J; Jenisch D; Meggers E Enantioselective and Enantioconvergent Iron-Catalyzed C(sp3)-H Aminations to Chiral 2-Imidazolidinones. Chin. J. Chem 2023, 41, 2065. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ye C-X; Dansby DR; Chen S; Meggers E Expedited synthesis of α-amino acids by single-step enantioselective α-amination of carboxylic acids. Nat. Synth 2023, 2, 645. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Wang H-H; Shao H; Huang G; Fan J; To W.-p.; Dang L; Liu Y; Che C-M Chiral Iron Porphyrins Catalyze Enantioselective Intramolecular C(sp3)-H Bond Amination Upon Visible-Light Irradiation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2023, 62, No. e202218577. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Das SK; Roy S; Khatua H; Chattopadhyay B Iron-Catalyzed Amination of Strong Aliphatic C(sp3)-H bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 16211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29). Zhang L; Deng L C-H bond amination by iron-imido/nitrene species. Chin. Sci. Bull 2012, 57, 2352. See also refs 25-27

- (30).(a) Sousa e Silva FC; Doktor K; Michaudel Q Modular Synthesis of Alkene Sulfamates and β-Ketosulfonamides via Sulfur (VI) Flouride Exchange (SuFEx) Click Chemistry and Photomediated 1,3-Rearrangement. Org. Lett 2021, 23, 5271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xin H; Duan X-H; Yang M; Zhang Y; Guo L-N Visible Light-Driven, Copper-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidative Cleavage of Cyclo-alkanones. J. Org. Chem 2021, 86, 8263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Deng L; Fu Y; Lee SY; Wang C; Liu P; Dong G Kinetic Resolution via Rh-Catalyzed C-C Activation of Cyclobutanones at Room Temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 16260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kim S; Joe GH; Do JY Highly efficient intramolecular addition of aminyl radicals to carbonyl groups: a new ring expansion reaction leading to lactams. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1993, 115, 3328. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Fiori KW; Espino CG; Brodsky BH; Du Bois J A mechanistic analysis of the Rh-catalyzed intramolecular C-H amination reaction. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 3042. [Google Scholar]

- (32).(a) Li P; Cao Z Mechanism Insights into the Csp3-H Amination Catalyzed by the Metal Phthalocyanine. Organometallics 2019, 38, 343. [Google Scholar]; (b) Simmons E; Hartwig JF On the Interpretation of Deuterium Kinetic Isotope Effects in C-H Bond Functionalization by Transition-Metal Complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 3066. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Our KIE experiments indicate that the HAT step is not rate-determining. Computational studies in Figure 2 showed low barriers for both the HAT and radical rebound steps (<5 kcal/mol). In contrast, a previous report (ref 32) suggested a much higher barrier for iminoiodinane formation, pointing to this step as the likely rate-determining step.

- (34). Li P; Cao Z Mechanism Insights into the Csp3-H Amination Catalyzed by the Metal Phthalocyanine. Organometallics 2019, 38, 343. Vila MA; Steck V; Rodriguez Giordano S; Carrera I; Fasan R C-H Amination via Nitrene Transfer Catalyzed by Mononuclear Non-Heme Iron-Dependent Enzymes. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 1981. Mahajan M; Mondal B How Axial Coordination Regulates the Electronic Structure and C─H Amination Reactivity of Fe─Porphyrin─Nitrene? JACS Au 2023, 3, 3494–3505. Zhang Y; Chu JM Computational Mechanistic Investigations of Biocatalytic Nitrenoid C─H Functionalizations via Engineered Heme Proteins. ChemBioChem 2023, 24, No. e202300260. (e) See refs20d, 21a, 22, and 26.

- (35).Zhao Y; Truhlar DG The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc 2008, 120, 215. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Dolg M; Wedig U; Stoll H; Preuss H Energy-adjusted ab initio pseudopotentials for the first-row transition elements. J. Chem. Phys 1987, 86, 866–872. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Marenich AV; Cramer CJ; Truhlar DG Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).(a) Lee C; Yang W; Parr RG Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785. [Google Scholar]; (b) Becke AD Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys 1993, 98, 5648. [Google Scholar]; (c) Grimme S; Ehrlich S; Goerigk L Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem 2011, 32, 1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).For previous studies on the mechanisms to form Fe─nitrenoid complexes, see: (a)Zhu S-Y; He W-J; Shen G-C; Bai Z-Q; Song F-F; He G; Wang H; Chen G Ligand-Promoted Iron-Catalyzed Nitrene Transfer for the Synthesis of Hydrazines and Triazanes through N-Amidation of Arylamines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2024, 63, No. e202312465.Su S; Zhang Y; Liu P; Wink DJ; Lee D Intramolecular Carboxyamidation of Alkyne-Tethered O-Acylhydroxamates through Formation of Fe(III)-Nitrenoids. Chem.—Eur. J 2024, 30, No. e202303428. Brandenberg OF; Fasan R; Arnold FH Exploiting and Engineering Hemoproteins for Abiological Carbene and Nitrene Transfer Reactions. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 2017, 47, 102. Natoli SN; Hartwig JF Noble–Metal Substitution in Hemoproteins: An Emerging Strategy for Abiological Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res 2019, 52, 326. Yang Y; Arnold FH Navigating the Unnatural Reaction Space: Directed Evolution of Heme Proteins for Selective Carbene and Nitrene Transfer. Acc. Chem. Res 2021, 54, 1209.

- (40).(a) Shepard SG; Fatur SM; Rappé AK; Damrauer NH Highly Strained Iron(II) Polypyridines: Exploiting the Quintet Manifold To Extend the Lifetime of MLCT Excited States. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Antalík A; Nachtigallová D; Lo R; Matoušek M; Lang J; Legeza O; Pittner J; Hobza P; Veis L Ground State of the Fe(II)-Porphyrin Model System Corresponds To Quintet: A DFT and DMRG-Based Tailored CC Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2020, 22, 17033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Khvostichenko D; Choi A; Boulatov R Density Functional Theory Calculations of the Lowest Energy Quintet and Triplet States of Model Hemes: Role of Functional, Basis Set, and Zero-Point Energy Corrections. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 3700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.