Abstract

Stridor, choking episodes and recurrent respiratory infections are common causes of referral for echocardiographic evaluation of the cardiovascular system. Vascular anomalies are rare but important causes of airway symptoms and/or feeding difficulty in young infants and should be carefully evaluated during echocardiogram.

Keywords: Aberrant left pulmonary artery, left pulmonary artery sling, recurrent respiratory tract infection

INTRODUCTION

Vascular ring and sling anomalies are commonly discussed during the evaluation of young infants for frequent airway symptoms, specifically stridor. A left pulmonary artery (LPA) sling is a rare congenital vascular anomaly in which the LPA arises from the right pulmonary artery (RPA) instead of the pulmonary trunk and courses toward the hilum of the left lung, lying between the esophagus and the trachea. Its prevalence is estimated to be 1 in 17,000 among school-aged children.[1,2]

The aberrantly coursing artery compresses the esophagus on its anterior aspect and trachea from behind. Although there is no vascular ring because the trachea’s left aspect is free, the LPA sling is often associated with significant tracheal stenosis and maldevelopment of the bronchial tree. We present the case of a 3-month-old male infant with recurrent respiratory symptoms diagnosed with an LPA sling.

CASE

A 3-month-old boy presented with a history of recurrent cough and respiratory distress for which he was hospitalized two times in the past. He was born at term, with a birth weight of 2.5 kg, and had an uneventful perinatal period. There was no history of feeding difficulty. The first respiratory tract illness was reported after the age of 1 month. He was referred to our center to exclude important congenital cardiac defects.

At the time of presentation, the patient had bilateral rhonchi and tachypnea. Echocardiogram on the parasternal short-axis plane showed pulmonary artery bifurcation occurring more distally and LPA coursing posterior to the trachea, marked by its echo-bright tracheal cartilage [Figure 1]. There was no associated intracardiac defect or evidence of pulmonary hypertension. Chest x-ray showed normal lung parenchyma without cardiomegaly.

Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiogram in parasternal short-axis view showing left pulmonary artery originating from the right pulmonary artery and coursing posterior to the trachea. RPA: Right pulmonary artery, LPA: Left pulmonary artery

With the echocardiographic features suggestive of an LPA sling, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with angiogram was performed to define the anatomy further and characterize the associated airway malformation. There were patchy alveolar opacities in bilateral lungs, predominantly in bilateral lower lobes, on plain film, while the contrast study revealed the aberrant origin of the LPA from the RPA, which then traversed between trachea anteriorly and esophagus posteriorly, with segmental narrowing and rightward bending of the lower one-third of trachea [Figures 2-4].

Figure 2.

Axial plane computed tomography angiography image showing left pulmonary artery (asterisk) arising from the right pulmonary artery and coursing anterior to the esophagus (thick arrow) and starts compressing the trachea (thin arrow) from the posterior aspect

Figure 4.

Axial computed tomography angiography image showing tracheal dimensions at its narrowest part

Figure 3.

Coronal MinIP image showing segmental narrowing (arrow) and rightward bending of the lower one-third of the trachea

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was attempted to further characterize the airway involvement. A flexible pediatric bronchoscope with a tip diameter of 3.1 mm failed to pass through the stenosed mid-tracheal segment, which measured 2.6 mm × 2 mm [Figures 5 and 6]. In our experience, fixed mild narrowing is enough to prevent the bronchoscope from passing through it compared to dynamic tracheomalacia. Severe tracheal stenosis was in our case due to a complete tracheal ring, which is a known airway abnormality with LPA sling. Abdominal ultrasound excluded associated gastrointestinal and renal malformations. The infant underwent successful LPA reimplantation and airway reconstructive surgery.

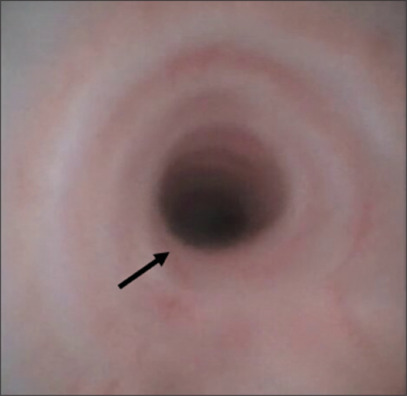

Figure 5.

Video bronchoscopy showing normal proximal trachea. Arrow shows normal proximal tracheal lumen

Figure 6.

Video bronchoscopy showing slit-like appearance of the distal trachea due to severe stenosis. Arrow shows slit like opening of distal trachea

DISCUSSION

The two distinct types of this malformation are described: type 1, which is less complex and associated with tracheobronchomalacia and type 2, characterized by long-segment tracheal stenosis. The word “sling” is used due to the looping appearance of the LPA around the central airways.[1]

LPA sling is associated with respiratory symptoms in the 1st year of life, due to tracheal compression, which can be life-threatening.[2] There may be expiratory stridor, recurrent respiratory infections, pulmonary air trapping, and esophageal compression, which causes dysphagia and vomiting. Failure to recognize these symptoms can lead to sudden death in neonates and infants. Currently, the most important prognostic factor is an associated tracheobronchial tree anomaly rather than cardiac defects, especially a long segmental tracheobronchial stenosis, which makes type 2 more severe.[3] Evaluation of patients with clinically suspected PA sling should include echocardiography, CT/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and bronchoscopy[3] to comprehensively assess all cardiac structures, including their relationship with the trachea and the esophagus, to determine the appropriate surgical approach. An echocardiogram is often the first line of investigation for suspecting the condition. On the other hand, CT angiography is effective in delineating the pulmonary vasculature and bronchial anatomy.[4] Important anatomic description includes the location, severity and nature of stenosis (focal vs diffuse) as well as the relationship of the aberrant LPA with trachea and esophagus. Cardiac MRI is also an effective option. However, it often requires general anesthesia, which may not be advisable in patients experiencing respiratory symptoms.[4] While bronchoscopy can identify the presence of tracheal rings, it is often unable to evaluate the distal bronchi due to stenosis of the airways. Computational fluid dynamics analysis has been proposed to assess the effect of tracheobronchial stenosis on the airway; however, its clinical utility remains to be seen.[5] In patients with apparent symptoms, surgical intervention is essential and effective. Surgical management involves transection of the LPA and reimplantation into the main pulmonary artery and concomitant repair of tracheal stenosis and coexisting cardiac lesions, if present.[2] It is the type and severity of airway involvement that determines the prognosis and probability of surgical success.[4]

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the parents have given their consent for their baby’s images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The parents understand that their baby’s name and initial will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee KH, Yoon CS, Choe KO, Kim MJ, Lee HM, Yoon HK, et al. Use of imaging for assessing anatomical relationships of tracheobronchial anomalies associated with left pulmonary artery sling. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:269–78. doi: 10.1007/s002470000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu JM, Liao CP, Ge S, Weng ZC, Hsiung MC, Chang JK, et al. The prevalence and clinical impact of pulmonary artery sling on school-aged children: A large-scale screening study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43:656–61. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yong MS, Zhu MZL, Bell D, Alphonso N, Brink J, d'Udekem Y, et al. Long-term outcomes of surgery for pulmonary artery sling in children. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;56:367–76. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezz012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong YM, Jaffe RB, Zhu M, Gao W, Sun AM, Wang Q. CT assessment of tracheobronchial anomaly in left pulmonary artery sling. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1755–62. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1682-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qi S, Li Z, Yue Y, van Triest HJ, Kang Y. Computational fluid dynamics simulation of airflow in the trachea and main bronchi for the subjects with left pulmonary artery sling. Biomed Eng Online. 2014;13:85. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-13-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]