Abstract

Evidence is lacking for guiding optimal combination hypertension therapy in South Asian patients. Here we investigated the blood pressure (BP)-lowering efficacy and safety of three commonly recommended antihypertensive dual combinations in a multicenter, single-blinded trial conducted in India. We randomized Indians aged 30–79 years (mean age, 52 years) with mean sitting systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 150–179 mmHg on no treatment or an SBP of 140–159 mmHg on monotherapy 1:1:1 to a single-pill combination of amlodipine–perindopril, perindopril–indapamide or amlodipine–indapamide. The primary outcome was the mean change in 24-hour ambulatory SBP at 6 months. Of the 1,981 participants (42% females) enrolled in the trial, 1,637 completed a 24-hour ambulatory BP measurement. All three drug combinations produced similar large reductions in the primary outcome, namely ambulatory (~14/8 mmHg) and office (~30/14 mmHg) BPs after 6 months, such that hypertension control rates (sitting BP < 140/90 mmHg) were achieved in approximately 70% of participants in all three groups. Furthermore, no significant differences in secondary outcomes, such as mean day and night ambulatory and office BPs and hypertension control rates, were observed among the study groups. Thus, in Indian patients, amlodipine–perindopril, perindopril–indapamide and amlodipine–indapamide were all equally well tolerated and equally highly effective in reducing 24-hour ambulatory and office BPs (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT05683301).

Subject terms: Randomized controlled trials, Renovascular hypertension, Preventive medicine

To address an evidence gap for the efficacy of hypertension therapy using dual drug combinations in patients of South Asian origin, a randomized clinical trial conducted in India found that three types of dual drug combinations, each administered in a single pill, had similarly large effects on reducing blood pressure.

Main

Hypertension affects over 1.3 billion adults worldwide1. Elevated BP is the single largest contributor to the global burden of disease and mortality, annually causing 7.8% of the disability-adjusted life years lost and one in six deaths (10.9 million)2. It is critical that treatment and control rates of hypertension be improved given that its adverse effects are increasing in absolute terms3. Initiating dual combinations of BP-lowering therapy, ideally as single-pill combinations (SPCs), is one of the proposed mechanisms for improving BP management3–6.

The usual dual combinations recommended are any two of a renin-angiotensin system blocker (angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB)), a calcium channel blocker and a diuretic (thiazide or thiazide-like)3–6. Some randomized trial data are available to compare the cardiovascular protective effects of different combinations of BP-lowering agents7–9. However, the BP-lowering efficacy of the major drug classes appears to differ among ethnic groups10–12, and the CREOLE trial13 identified significant differences in BP lowering caused by three dual combinations of agents taken by Black patients with hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa.

Nevertheless, no robust data are available to inform optimal dual combinations for the treatment of hypertension in patients of South Asian origin, who constitute a quarter of the world’s population. India has an enormous burden of hypertension, with an estimated 300 million individuals with high BP, among whom poor BP control in both rural (7–11%) and urban (11–20%) populations is reported14–16.

We, therefore, conducted the Treatment Optimisation of blood Pressure with Single-Pill combinations in INdia (TOPSPIN) trial to compare the efficacy of amlodipine plus perindopril, amlodipine plus indapamide and perindopril plus indapamide in reducing the BP of Indian patients aged 30–79 years with hypertension.

Results

Study participants

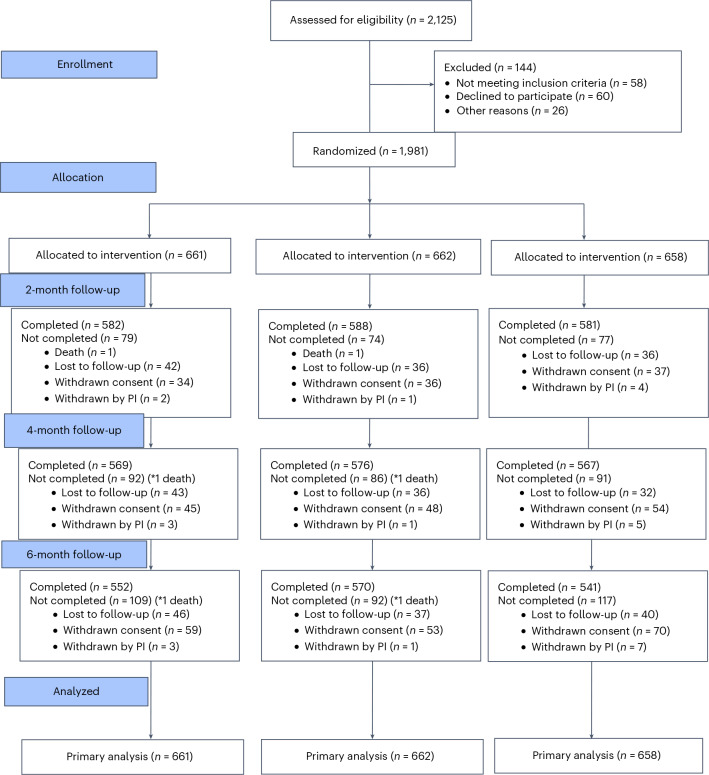

We screened 2,125 patients with hypertension and randomized 1,981 participants. Of these, 661 participants received amlodipine and perindopril, 662 received perindopril and indapamide and 658 received amlodipine and indapamide as SPCs. At 6 months, 1,663 (84.0%) participants completed follow-up, with a 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) in 1,637 (82.6%). During follow-up, two participants died, 123 were lost to follow-up and 182 withdrew consent, and the treating physician withdrew the study medication in 11 participants (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Design and follow-up of the TOPSPIN trial.

The CONSORT flow diagram of the TOPSPIN trial. PI, principal investigator.

We included 1,981 participants in the primary analysis using multiple imputation for 344 participants who did not complete ABPM recording at 6 months. No difference was observed in the participant characteristics among those who completed and did not complete the ABPM measurement at 6 months (Extended Data Table 1). Overall, the participants had a mean age of 52.1±11.1 years; 42.1% were women; 18.6% had self-reported diabetes; and 58.1% had previously diagnosed hypertension. The baseline characteristics, 24-hour ambulatory and office BPs and laboratory parameters were similar across the groups (Table 1 and Extended Data Table 2). The demographic and clinical characteristics of those who did and did not provide 24-hour ambulatory recordings at 6 months were similar (Extended Data Table 1).

Extended Data Table 1.

Comparison of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants with and without ABPM at 6 months

Plus–minus values are means±s.d.

†BMI is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

‡Self-reported history

§Average of the last two of three office BP readings

¶24-hour ambulatory BP was measured (one reading every 30 minutes) using a TM-2440 device (A&D Medical). Daytime ambulatory BP was estimated as the average of values between 9:00 and 21:00 and nighttime ambulatory BP as the average of values between 24:00 and 6:00.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants at baseline

| Characteristic | Amlodipine–perindopril | Perindopril–indapamide | Amlodipine–indapamide |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 661) | (n = 662) | (n = 658) | |

| Age | |||

| Mean (years) | 52.2±11.1 | 52.2±11.2 | 51.8±11.4 |

| Distribution – no. (%) | |||

| ≥55 years | 267 (40.4) | 270 (40.8) | 260 (39.5) |

| <55 years | 394 (59.6) | 392 (59.2) | 398 (60.5) |

| Sex | |||

| Females – no. (%) | 278 (42.1) | 265(40.0) | 260 (44.2) |

| BMI (kg m−2)a | 26.5±4.1 | 26.3±4.1 | 26.6±4.3 |

| Current smoker – no. (%) | 40 (6.1) | 46 (6.9) | 38 (5.8) |

| Diabetes – no. (%)b | 125 (18.9) | 125 (18.9) | 120 (18.2) |

| Dyslipidemia – no. (%)b | 48 (7.3) | 47 (7.1) | 49 (7.4) |

| Previously diagnosed hypertension – no. (%)b | 393 (59.5) | 384 (58.0) | 372 (56.5) |

| BP (mmHg) | |||

| Office systolicc | 155.1±9.6 | 155.6±10.0 | 155.4±9.6 |

| Office diastolic | 92.3±10.8 | 91.9±10.6 | 91.8±11.1 |

| 24-hour ambulatory systolicd | 135.9±16.9 | 135.4±17.1 | 135.3±17.0 |

| 24-hour ambulatory diastolic | 85.0±11.0 | 84.2±10.8 | 84.2±11.0 |

| Daytime ambulatory systolic | 140.3±17.3 | 140.1±17.4 | 139.6±16.7 |

| Daytime ambulatory diastolic | 88.5±11.4 | 87.8±11.5 | 87.5±11.0 |

| Nighttime ambulatory systolic | 126.8±19.9 | 126.2±20.4 | 126.5±20.6 |

| Nighttime ambulatory diastolic | 78.4±12.8 | 77.7±12.4 | 77.8±13.2 |

| Previous antihypertensive therapy – no. (%) | |||

| ARB | 225 (34.0) | 195 (29.5) | 193 (29.2) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 103 (15.6) | 127 (19.2) | 120 (18.2) |

| Beta-blocker | 40 (6.1) | 35 (5.3) | 31 (4.7) |

| ACE inhibitor | 7 (1.1) | 8 (1.2) | 7 (1.1) |

| Diuretic | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

Plus–minus values are mean ± s.d.

aBMI is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

bSelf-reported.

cAverage of the last two of three office BP readings.

d24-hour ambulatory BP was measured (one reading every 30 minutes) using a TM-2440 device (A&D Medical). Daytime ambulatory BP was estimated as the average of values between 9:00 and 21:00 and nighttime ambulatory BP as the average of values between 24:00 and 6:00.

Extended Data Table 2.

Baseline laboratory parameters

Values are presented as mean±s.d. or median (interquartile range).

Treatment combinations and ambulatory BP

At 6 months, the unadjusted reduction in the primary outcome of 24-hour ambulatory SBP was 14.5 mmHg (95% confidence interval (CI): −16.0 to −13.2 mmHg) for amlodipine–perindopril; 13.3 mmHg (95% CI: −14.7 to −11.9 mmHg) for perindopril–indapamide; and 13.9 mmHg (95% CI: −15.3 to −12.4 mmHg) for amlodipine–indapamide (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Unadjusted mean change in BP.

a–d, Bar graphs with error bars showing ambulatory SBP (a), ambulatory DBP (b), office SBP (c) and office DBP (d). In c and d, the bars represent mean change in BP at 2 months, 4 months and 6 months. Error bars denote 95% CI.

No significant difference was observed in the primary outcome of mean change in ambulatory SBP adjusted for baseline value, stratification variables and sex among the three groups (Table 2). Similarly, the unadjusted reductions in 24-hour ambulatory DBP were similar across the groups (Fig. 2). Other secondary outcome measures of ABPM also revealed no significant difference in changes from baseline values between any two groups (Table 2). No differences were noted in the ambulatory BP in the complete case analysis (Extended Data Table 3). No significant interactions were apparent between any of the prespecified subgroups and the three treatment arms for the primary outcome except among body mass index (BMI) strata (Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted mean between-group differences in changes from baseline in ambulatory BP

| Ambulatory BP | Amlodipine–perindopril | Amlodipine–perindopril | Perindopril–indapamide | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| versus Perindopril–indapamide | versus Amlodipine–indapamide | versus Amlodipine–indapamide | ||||

| Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | |

| Model 1a | ||||||

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| 24-hour systolic | −0.81 (−2.28 to 0.65) | 0.27 | −0.33 (−1.77 to 1.12) | 0.65 | 0.49 (−0.96 to 1.94) | 0.54 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| 24-hour diastolic | −0.30 (−1.25 to 0.65) | −0.40 (−1.31 to 0.51) | −0.10 (−1.03 to 0.84) | |||

| Daytime systolic | −0.98 (−2.55 to 0.60) | −0.65 (−2.2 to 0.89) | 0.32 (−1.24 to 1.89) | |||

| Nighttime systolic | 0.00 (−1.80 to 1.80) | 0.26 (−1.53 to 2.05) | 0.26 (−1.49 to 2.01) | |||

| Daytime diastolic | −0.42 (−1.53 to 0.69) | −0.50 (−1.60 to 0.59) | −0.09 (−1.22 to 1.05) | |||

| Nighttime diastolic | 0.17 (−0.92 to 1.26) | 0.42 (−0.66 to 1.51) | 0.25 (−0.82 to 1.33) | |||

| Model 2b | ||||||

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| 24-hour systolic | −0.88 (−2.35 to 0.59) | 0.24 | −0.31 (−1.76 to 1.14) | 0.67 | 0.57 (−0.88 to 2.01) | 0.49 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| 24-hour diastolic | −0.39 (−1.34 to 0.55) | −0.48 (−1.39 to 0.43) | −0.08 (−1.02 to 0.85) | |||

| Daytime systolic | −1.04 (−2.62 to 0.54) | −0.63 (−2.18 to 0.92) | 0.41 (−1.16 to 1.98) | |||

| Nighttime systolic | −0.06 (−1.86 to 1.75) | 0.29 (−1.51 to 2.09) | 0.34 (−1.41 to 2.10) | |||

| Daytime diastolic | −0.52 (−1.63 to 0.60) | −0.56 (−1.66 to 0.55) | −0.04 (−1.17 to 1.09) | |||

| Nighttime diastolic | 0.08 (−1.01 to 1.16) | 0.36 (−0.73 to 1.45) | 0.28 (−0.80 to 1.35) | |||

aModel 1: The primary outcome analysis was performed using a multiple linear regression model adjusted for the ambulatory SBP at baseline, sex and stratification variables (age (<55 years and ≥55 years) and recruiting center) according to the intention-to-treat principle. A P value of 0.0167 was considered significant for adjustment for multiple hypothesis testing.

bModel 2 was a sensitivity analysis performed with stratification variables (age and recruiting center), sex, respective baseline ambulatory BP values, presence of diabetes mellitus, BMI, heart rate and duration of hypertension.

Extended Data Table 3.

Adjusted mean between-group differences in changes from baseline in ambulatory BP (complete case analysis)

†Model 1 was performed using a multiple linear regression model adjusted for the ambulatory SBP at baseline, age (<55 years and ≥55 years), clinical site and sex among participants who completed the follow-up.

‡Model 2 was a sensitivity analysis performed with stratification variables (age and clinical site), sex, respective baseline ambulatory BP values, presence of diabetes mellitus, BMI, heart rate and duration of hypertension among participants who completed the follow-up.

Extended Data Fig. 1. Changes in Ambulatory Systolic Blood Pressure by Pre-Specified Sub-Groups.

Plots showing mean difference with 95% CI and p-value for interaction.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Changes in Ambulatory Diastolic Blood Pressure by Pre-Specified Sub-Groups.

Plots showing mean difference with 95% CI and p-value for interaction.

Treatment combinations and office BP

The unadjusted mean reduction in office SBP and DBP at 6 months was 30.4 mmHg (95% CI: −31.7 to −29.2 mmHg), 30.4 mmHg (95% CI: −31.6 to −29.2 mmHg) and 30.5 (95% CI: −31.7 to −29.2 mmHg) and 14.7 mmHg (95% CI: −15.8 to −13.6 mmHg), 14.0 mmHg (95% CI: −15.1 to −13.0 mmHg) and 13.9 mmHg (95% CI: −15.0 to −12.8 mmHg) in the amlodipine–perindopril, perindopril–-indapamide and amlodipine–indapamide groups, respectively.

At 2 months, participants who received amlodipine–perindopril had greater reductions in office DBP than participants who received perindopril–indapamide with a mean difference between groups of −1.25 mmHg (95% CI: −2.31 to −0.20), but there were no other significant differences among treatment groups at 2 months, 4 months and 6 months (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted mean between-group differences in changes from baseline in office BP

| Office BP | Amlodipine–perindopril versus perindopril–indapamide | Amlodipine–perindopril versus amlodipine–indapamide | Perindopril–indapamide versus amlodipine–indapamide |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference (95% CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

| Systolic | |||

| Month 2 | −1.40 (−2.79 to 0.00) | −1.03 (−2.43 to 0.37) | 0.37 (−1.02 to 1.76) |

| Month 4 | −0.45 (−1.86 to 0.96) | −0.07 (−1.49 to 1.34) | 0.37 (−1.03 to 1.78) |

| Month 6 | −0.49 (−1.91 to 0.93) | −0.67 (−2.11 to 0.76) | −0.18 (−1.61 to 1.25) |

| Diastolic | |||

| Month 2 | −1.25 (−2.31 to −0.20) | −0.97 (−2.03 to 0.09) | 0.29 (−0.77 to 1.34) |

| Month 4 | −0.61 (−1.68 to 0.45) | 0.34 (−0.73 to 1.41) | 0.96 (−0.11 to 2.02) |

| Month 6 | −0.37 (−1.44 to 0.71) | −0.51 (−1.61 to 0.58) | −0.15 (−1.23 to 0.93) |

Office BP was measured at baseline and at 2 months, 4 months and 6 months (the average of the last two of three office BP readings is shown). The between-group differences in mean change in BP from baseline were estimated using a linear mixed-effects model adjusting for baseline value, gender and randomization stratification variables (age and site) as fixed effects and participant as a random effect, time-by-arm interaction.

We did not observe differences in the response rates or in conservative and more current office BP control rates among the treatment groups (Table 4 and Extended Data Table 4). At 6 months, based on office BPs, almost half of the participants were classified as responders; over two-thirds achieved conservative BP control targets; and over 40% achieved more current BP control targets (Table 4 and Extended Data Table 4).

Table 4.

Secondary outcome analysis—office BP response and control rates

| Amlodipine–perindopril | Perindopril–indapamide | Amlodipine–indapamide | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 661 | n = 662 | n = 658 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Response ratea | |||

| 2-month | 266 (40.2) | 243 (36.7) | 237 (36.0) |

| 4-month | 301 (45.5) | 302 (45.6) | 307 (46.7) |

| 6-month | 315 (47.7) | 317 (47.9) | 306 (46.5) |

| Proportion of respondersb | 266 (40.2) | 260 (39.3) | 248 (37.7) |

|

Control ratec (<140 and 90 mmHg) | |||

| 2-month | 424 (64.1) | 411 (62.1) | 417 (63.4) |

| 4-month | 464 (70.2) | 478 (72.2) | 470 (71.4) |

| 6-month | 470 (71.1) | 486 (73.4) | 454 (69.0) |

| Proportion with BP controld | 440 (66.6) | 457 (69.0) | 429 (65.2) |

|

Control ratec (<130 and 80 mmHg) | |||

| 2-month | 221 (33.4) | 196 (29.6) | 199 (30.2) |

| 4-month | 267 (40.4) | 266 (40.2) | 285 (43.3) |

| 6-month | 282 (42.7) | 274 (41.4) | 262 (39.8) |

| Proportion with BP controld | 194 (29.3) | 195 (29.5) | 191 (29.0) |

Office BP was measured at baseline and at 2 months, 4 months and 6 months (the average of the last two of three office BP readings is used).

aThe response rate is the proportion of patients with a reduction in office SBP ≥20 mmHg and office DBP ≥10 mmHg at a given time.

bThe proportion of patients classified as ‘responders’ is defined as those who had a reduction of office SBP ≥20 mmHg and office DBP ≥10 mmHg at any of their office visits, with maintenance of this reduction at the 6-month office visit.

cThe control rate is the proportion of patients with an office BP of less than (140 and 90 mmHg or 130 and 80 mmHg) at a given time.

dThe proportion of patients who achieve BP control is defined as achieving target BP (less than 140 and 90 mmHg or 130 and 80 mmHg) at any of their office visits, with maintenance of this reduction at the 6-month office visit.

Extended Data Table 4.

Adjusted mean differences in BP response and control between the groups

Office BP was measured at baseline and at 2 months, 4 months and 6 months (average of the last two of three office BP readings). The between-group differences in mean change in BP from baseline to 6 months were estimated using a linear mixed-effects model adjusting for baseline value and randomization stratification variables (age and site) as fixed effects and participant as a random effect, time-by-arm interaction.

†The response rate is the proportion of patients with a reduction in the office SBP ≥20 mmHg and office DBP ≥10 mmHg at a given time.

‡ The proportion of patients classified as ‘responders’ was defined as those who had a reduction of office SBP ≥20 mmHg and office DBP ≥10 mmHg at any of their clinic visits and maintained at the 6-month clinic visit.

§The control rate is the proportion of patients with an office BP of less than (140 and 90 mmHg or 130 and 80 mmHg) at a given time.

¶The proportion of patients who achieve BP control is defined as achieving target BP (140 and 90 mmHg or 130 and 80 mmHg) at any of their clinic visits and maintained at the 6-month clinic visit.

Laboratory measures

The changes in various laboratory parameters are shown in Extended Data Table 5. A significant decrease was observed in fasting blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin levels in the amlodipine–perindopril group compared to the amlodipine–indapamide group. There were other clinically small but significant between-group differences in serum sodium, potassium, uric acid, urea and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), in keeping with established effects of ACE inhibitors and diuretics on these variables. Overall hypokalemia (<3.5 mmol l−1) was detected at 6 months in 7.4% of participants for whom intervention was not required. However, differential effects across drug groups were apparent, with 15.2% of recipients of amlodipine plus indapamide having hypokalemia at 6 months.

Extended Data Table 5.

Six-month and mean change in laboratory parameters

*Comparisons that were statistically significant

Safety outcomes

A total of 51 participants experienced adverse events causing withdrawal of the study drug. Of these, 14 were in the amlodipine–perindopril group, 19 were in the perindopril–indapamide group and 18 were in the amlodipine–indapamide group. These participants reported a total of 77 adverse symptoms, of which dizziness (23 participants), pedal swelling (12 participants) and headache (10 participants) were the most common (Extended Data Table 6). Serious adverse events, defined as death or hospitalizations for any cause, occurred in 21 participants, but none was considered related to the study drugs.

Extended Data Table 6.

Serious adverse events and adverse events leading to drug withdrawal

*Serious adverse events were defined as death or all-cause hospitalizations.

Per-protocol analyses

Among the participants completing the 6-month follow-up, 1,307 (66.0%) were classified as adherent. We found no differences in the mean ambulatory BP changes among treatment groups in patients who were adherent (Extended Data Table 7).

Extended Data Table 7.

Adjusted mean between-group differences in changes from baseline in ambulatory BP (per-protocol analysis)

†Model 1 was performed using a multiple linear regression model adjusted for the ambulatory SBP at baseline, age (<55 years and ≥55 years), clinical site and sex among participants who adhered to the study protocol.

‡Model 2 was a sensitivity analysis performed with stratification variables (age and clinical site), sex, respective baseline ambulatory BP values, presence of diabetes mellitus, BMI, heart rate and duration of hypertension among participants who adhered to the study protocol.

Discussion

In this randomized trial of three commonly recommended dual combinations of antihypertensive agents, we found no differences in the ambulatory and office BPs of South Asian patients after 6 months of follow-up. Similarly, we found no differences in responder and control rates among the three treatment groups.

Our trial suggests that, in South Asian patients with untreated or uncontrolled hypertension while taking monotherapy, the use of any of the three dual combinations evaluated causes large reductions in 24-hour ambulatory and clinic BPs such that, at 6 months, the clinic BPs of approximately 70% of participants were controlled to less than 140/90 mmHg, and over 40% were controlled to less than 130/80 mmHg. The control rates are superior to most of those reported in patients worldwide17–19.

These results contrast with those observed in the similarly designed CREOLE trial13 involving Black patients in sub-Saharan Africa, where a calcium channel blocker combined with either an ACE inhibitor or a diuretic was superior to an ACE inhibitor and diuretic combination. However, in the South Asian context, the findings were compatible with several current guidelines that recommend using any dual combination from among a renin-angiotensin system blocker, a calcium channel blocker and a diuretic3–6.

All three dual combinations were well tolerated, with less than 3% of participants having their therapy withdrawn due to side effects. However, an unknown proportion of those lost to follow-up may have been affected by side effects that were not reported. Notably, no serious cases of angioedema were reported. Furthermore, none of the 21 serious adverse events recorded was attributed to study drugs, and two-thirds of participants were classified as similarly compliant in all three groups, having consumed 80% or more of the prescribed medications throughout the trial.

Several clinically minor but statistically significant differential changes in laboratory parameters were apparent, particularly in renal function, potassium and uric acid on expected lines (Extended Data Table 5). Fasting blood glucose levels and glycated hemoglobin levels were lowest with the amlodipine–perindopril combination and were significantly lower than in the amlodipine–indapamide combination at 6 months. This finding may have clinical implications for this population with a high propensity to diabetes and a substantial burden of dysglycemia20–22. The differential effects of the three drug combinations on serum potassium highlights that routine monitoring of electrolytes should be carried out particularly among those taking a diuretic.

Similar reductions in 24-hour ambulatory BPs achieved in all three treatment groups were also observed in the per-protocol analyses, post hoc controlled multiple imputation analyses and prespecified subgroups of age strata, sex, diabetes status and previously diagnosed hypertension at baseline. Although borderline significant interactions among the treatment groups by BMI strata were apparent, the inconsistent differences observed most likely reflect the play of chance.

Limitations of this trial include that 17.4% of participants did not provide 24-hour ambulatory recording at 6 months. However, the demographic and clinical characteristics of those who did and did not provide 24-hour ambulatory recordings at 6 months did not differ. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses including only those who completed 24-hour ambulatory recordings at baseline and 6 months confirmed the findings of the primary analyses, which included all participants via multiple imputations. Additional limitations of this trial include that all possible two-drug combinations (including agents such as beta-blockers or ARBs) were not evaluated and the uncertainty of translating these equivalent BP-lowering data to having no differential impact of the three dual combinations on major adverse cardiovascular events. However, pending a much-needed cardiovascular outcome trial in South Asian patients, it seems reasonable to expect similar outcomes with the three combinations evaluated in this trial.

Another potential limitation of the trial was that the drug dosing was not wholly symmetrical across the treatment groups for the first 2 months because indapamide sustained release (SR) is only available at a dose of 1.5 mg in an SPC with amlodipine. However, the BP-lowering efficacy of the indapamide SR 1.5 mg formulation is equivalent to the indapamide 2.5 mg formulation combined with perindopril23,24. Hence, between months 2 and 6, all medicines in the SPCs were at the usual maximum clinical dosage.

The study has important strengths. The three individual components of dual combinations evaluated in this trial—amlodipine, perindopril and indapamide—were used alone, in combination or with other drugs in several previous cardiovascular outcome trials8–11. These trials showed substantial benefit on various major cardiovascular endpoints and in different subgroups of patients (for example, diabetes, post-stroke and very elderly). Along with the BP-lowering efficacy reported here, these trials provide reassurance and support for the use of the dual combinations evaluated in this trial on South Asian patients, at least in the context of India.

The results of this trial may reasonably be extrapolated to a broad spectrum of Indian patients with hypertension because trial participants were recruited from 32 sites across the country with a wide age range (30–79 years); both men and women were well represented; and the trial included a mixture of treated and untreated patients.

In conclusion, in this trial involving South Asian patients in India, we found similar safety and efficacy in lowering ambulatory and office BPs with dual combinations of amlodipine–perindopril, perindopril–indapamide and amlodipine–indapamide. The study findings provide novel evidence to inform the choice of dual combination therapies for hypertension treatment among South Asians in India and potentially the diaspora.

Methods

Trial design and oversight

TOPSPIN was a prospective, single-blind, randomized three-arm trial conducted in 32 centers across India (3 of the 35 centers did not recruit any participants (Supplementary Table 1)). The detailed protocol of the study is published elsewhere25. A Trial Operations Committee managed the day-to-day running; a Trial Steering Committee oversaw the study’s progress; and a Data Safety and Monitoring Committee reviewed patient safety (see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 for committee membership).

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the participating centers and the coordinating center and was approved by the national regulatory authority.

Trial population and recruitment

Men and women 30–79 years of age were eligible if their sitting office SBP was between 140 and 159 mmHg on one antihypertensive medication or between 150 and 179 mmHg in drug-naive patients. Patients with a history of coronary artery and cerebrovascular diseases, congestive heart failure, serum creatinine above 1.5 mg dl−1, current pregnancy and secondary hypertension were excluded (see the study protocol in the Supplementary Information for a full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria). All participants provided written informed consent. Three sitting office BP measurements were recorded using standard methods with a fully automated oscillometric device (HEM-7201; Omron). The mean of the last two office BP recordings was used for patient eligibility and subsequent evaluations. Standard biochemical tests were performed for all patients. A 24-hour ABPM with readings taken every 30 minutes was performed using a validated device (TM-2440; A&D Medical). A minimum of 34 valid readings were needed to qualify as an adequate ABPM, and inadequate recordings were repeated. The mean of all valid readings was used in the analysis.

Randomization and treatment

Eligible participants were randomly allocated to one of the three study arms in a 1:1:1 ratio using variable permuted block electronic randomization. The randomization was stratified by age (<55 years or ≥55 years) and recruiting center. The investigators were unaware of the trial group assignments (single-blind randomization). The pills provided to the patients were not identical because of cost and logistical reasons; however, repackaging them in opaque packs minimized potential bias. After randomization, the patients discontinued their previous antihypertensive medications without a washout period and received one of the following once-daily SPCs: amlodipine 5 mg plus perindopril 4 mg or perindopril 4 mg plus indapamide 1.25 mg or amlodipine 5 mg plus indapamide SR 1.5 mg. For the first 2 months, it was not possible to provide equivalent dosing of indapamide in combination with perindopril and with amlodipine because amlodipine 5 mg is only produced in combination with indapamide SR at a dose of 1.5 mg, whereas perindopril 4 mg is combined with the non-SR formulation of indapamide at 1.25 mg. At 2 months, the doses were up-titrated to amlodipine 10 mg plus perindopril 8 mg or perindopril 8 mg plus indapamide 2.5 mg or amlodipine 10 mg plus indapamide SR 1.5 mg if the office SBP was ≥120 mmHg. At 4 months, a beta-blocker (bisoprolol 5 mg) was added if the SBP was ≥160 mmHg or the DBP was ≥100 mmHg. Spironolactone 12.5 mg or doxazosin 2 mg was added in patients for whom a beta-blocker was contraindicated. A pill count was done to assess adherence at scheduled visits (2, 4 and 6 months). Participants taking 80% or more of the prescribed doses throughout the trial were defined as adherent.

Trial outcomes

The primary outcome was the difference among the treatment groups in the mean reduction in the 24-hour ambulatory SBP at 6 months adjusted for baseline ambulatory SBP. Secondary outcomes included a reduction in ambulatory DBP; mean change in the daytime (9:00 to 21:00) and nighttime (24:00 to 6:00) ambulatory BPs; change in office BP at 2, 4 and 6 months; the proportion of participants achieving conservative (<140/90 mmHg) or more current (<130/80 mmHg) BP control level at any of the office visits and maintained at 6 months; the proportion of ‘responders’ to treatment (defined as a reduction of SBP of ≥20 mmHg and DBP of ≥10 mmHg at any of the office visits and maintained at 6 months); and changes in laboratory investigations, fasting blood glucose, lipid profile, serum sodium, potassium, urea, creatinine and eGFR. The safety endpoint of the study was the occurrence of adverse or serious adverse events leading to withdrawal of the study drug at any of the follow-ups. Prespecified subgroup analysis for the primary outcomes were age (<55 years and ≥55 years), sex (male and female), self-reported history of diabetes at baseline and previously or newly diagnosed hypertension at baseline and BMI of <23, 23–24.9 and ≥25 kg m−2.

Statistical analysis

With a planned sample size of 1,968 participants, the TOPSPIN trial had 85% power to detect a clinically meaningful difference of 3 mmHg in the 24-hour ambulatory SBP among the three groups. The assumptions included an s.d. of 15.0 mmHg, a two-sided significance level of 0.0167 (considered significant for adjustment of multiple hypothesis testing26 for the three comparisons) and a 10% dropout rate.

Data from clinical sites were collected using Clinion software version 3.0, and statistical analyses were conducted at the research coordinating center using Stata version 16.0. Baseline characteristics and key safety outcomes were compared between the study groups using the chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test and the two-sample t-test.

The primary outcome analysis was performed using a multiple linear regression model adjusted for the ambulatory SBP at baseline, age strata (<55 years and ≥55 years), recruiting center and sex according to the intention-to-treat principle. We performed multiple imputations for the primary analysis using multiple imputation chained equations for participants with a missing primary endpoint value. We generated 50 imputed datasets with a maximum of 1,000 iterations with linear imputation, including the treatment group, ambulatory SBP and DBP, office BP measurements, age, sex, recruiting center, BMI, presence of diabetes, duration of hypertension and pulse rate. This approach was repeated for the ambulatory DBP analysis27,28. We also performed analyses following the complete case scenario and per-protocol analyses, including only adherent participants.

We used a linear mixed-effect model to estimate the between-group mean difference in change in office BP measurement from baseline. The model included the participant as a random effect and age, site, sex and time-by-arm interaction as fixed effects. The same models were used for other continuous variable secondary outcomes. We compared the between-group differences in response and control rate, adjusting for age, recruiting center, sex and time-by-arm interaction using logistic regression. We did not plan for multiple comparison adjustments for secondary outcomes. Hence, we estimated the treatment effects in secondary outcomes as point estimates with 95% CIs (see the statistical analysis plan in the Supplementary Information).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41591-025-03854-w.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables 1–3, Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Trial Steering Committee and Data Safety and Monitoring Committee members of the TOPSPIN trial. We thank the TOPSPIN trial participants and their caregivers. The trial was supported by Imperial College London, the Centre for Chronic Disease Control, New Delhi and Servier International, France (unrestricted educational grant and in-kind logistical support). Servier had no role in the study’s design, data collection, analysis or manuscript preparation.

Extended data

Author contributions

D.P., A.R. and N.P. designed the study, coordinated the research and wrote the first draft of the paper. The TOPSPIN Clinical Consortia members conducted the trial in their hospitals. D.K. conducted the statistical analysis. V.R.C. reviewed the statistical analysis. S.M. and A.M.C. coordinated the conduct of the trial. All authors vouch for the accuracy and credibility of the data and the fidelity of the trialʼs conduct to the study protocol.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks David Flood, Andrew Moran, Gurpreet Singh Wander and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Michael Basson, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Data availability

Raw data cannot be publicly shared as per the Health Ministry Screening Committee of the Indian Government (National Regulatory Authority for human research with contributions from other countries), which mandates that no data can be shared beyond the borders without necessary approvals. Anonymized and tabulated or curated data will be made available to bona fide researchers for the purpose of meta-analysis and similar research interests with necessary approvals. Requests may be made to D.P. (dprabhakaran@ccdcindia.org). All such requests will be responded to within a 2-week timeframe.

Competing interests

N.P. has received financial support from several pharmaceutical companies that manufacture BP-lowering agents. N.P. has received consultancy fees (Servier and Aktiia), funding for research projects and staff (Servier and Pfizer) and fees for arranging and speaking at educational meetings (AstraZeneca, Lri Therapharma, Napi, Servier, Sanofi, Eva Pharma, Pfizer, Emcure India, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories and Zydus). He holds no stocks or shares in any such company. D.P.’s institution, the Centre for Chronic Disease Control, has received research grants from Sun Pharmaceuticals, Lupin Limited and Intas Pharmaceuticals in India for capacity building of primary care physicians in cardiovascular diseases. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Dorairaj Prabhakaran, Ambuj Roy.

A list of authors and their affiliations appear at the end of the paper.

Contributor Information

Dorairaj Prabhakaran, Email: dprabhakaran@ccdcindia.org.

TOPSPIN Clinical Consortia:

Bishav Mohan, Aman Khanna, Amit Malviya, Satish G. Patil, Vinod K. Abichandani, Bhupinder Singh, Shantanu Sengupta, Sunil Kumar, Neil Bardoloi, Nagendra Boopathy Senguttuvan, Rakesh Kumar Sahay, Suvarna Patil, Surender Deora, Rajpurohit Prahalad, Justin Paul Gnanaraj, Mallika Khanna, Animesh Mishra, Kiran Aithal, Vipul Chavda, Kyrshanglang G. Lynrah, Gurpreet Singh Wander, Gautam Singal, Akash Batta, Ankush Mittal, Suraj Kumar, Deepak Chaudhary, Maninder Kansal, B. K. Gupta, Jigyasa Gupta, Balsubramaniam Yellapantula, Ankita Kapse, D. Shailendra, M. Sneha Manju, M. Suchitra Uikey, Aniket Wazade, Prathibha Pereira, K. M. Srinath, K. C. Shashidhara, Vinay Kumar, Ajay Hanumamthu, K. S. Poornima, Dhanjit Nath, Amitava Misra, Mohini Singh, S. Lekshmi, Said Jabir, Sachin Surnar, Pranav Shamraj, Jyoti L. Iyer, Deepti Mathur, M. B. Shalini, S. V. Partha Saradhi, Rajendran Velayudham, Sudha Kulur Mukhyaprana, Hariharan Chellapandy, Vivek Jaganathan, Ramadevi Kanakasabapathi, E. Theranirajan, Debomallya Bhuyan, Barnali Bhuyan, Shoubhik Bhattacharjee, Sindhuja Kunapareddy, Ambuj Roy, Sandeep Singh, Sayavir Yadav, Kamar Ali, P. B. Jayagopal, Vinit Kr Shah, L. Sreenivasa Murthy, G. Pramod Bagali, P. V. Raghav Sarma, Chinta Srinivasarao, Sharan Badiger, Avinash V. Jugati, Saptarshi Bhattacharya, O. R. Kumaran, Anitha Kolukula, Harika Menti, H. C. Kalita, Hemant Thacker, Abhishek Subhas, Sudhir Varma, Harpreet Kalra, Sanchit Sood, Navjot Kaur, Prabh Simranpal, Taniya Aggarwal, Jabir Abdullakutty, Prashant Kr Sahoo, Sharmila Moharana, Yusuf A. Kumble, and P. N. Sandhya Rani

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41591-025-03854-w.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41591-025-03854-w.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global report on hypertension: the race against a silent killer. WHOhttps://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240081062 (2023).

- 2.Brauer, M. et al. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet403, 2162–2203 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whelton, P. K. et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension71, 1269–1324 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unger, T. et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. Hypertension75, 1334–1357 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McEvoy, J. W. et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Eur. Heart J.45, 3912–4018 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah, S. N. et al. Indian guidelines on hypertension-IV (2019). J. Hum. Hypertens.34, 745–758 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahlöf, B. et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet366, 895–906 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Julius, S. et al. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial. Lancet363, 2022–2031 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jamerson, K. et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N. Engl. J. Med.359, 2417–2428 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA288, 2981–2997 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Gupta, A. K. et al. Ethnic differences in blood pressure response to first and second-line antihypertensive therapies in patients randomized in the ASCOT trial. Am. J. Hypertens.23, 1023–1030 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Materson, B. J. et al. Single-drug therapy for hypertension in men—a comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo. N. Engl. J. Med.328, 914–921 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ojji, D. B. et al. Comparison of dual therapies for lowering blood pressure in black Africans. N. Engl. J. Med.380, 2429–2439 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anchala, R. et al. Hypertension in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension. J. Hypertens.32, 1170–1177 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy, A. et al. Changes in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control rates over 20 years in National Capital Region of India: results from a repeat cross-sectional study. BMJ Open7, e015639 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varghese, J. S. et al. Hypertension diagnosis, treatment, and control in India. JAMA Netw. Open6, e2339098 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou, B. et al. Long-term and recent trends in hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in 12 high-income countries: an analysis of 123 nationally representative surveys. Lancet394, 639–651 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geldsetzer, P. et al. The state of hypertension care in 44 low-income and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study of nationally representative individual-level data from 1.1 million adults. Lancet394, 652–662 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Beaney, T. et al. May Measurement Month 2019. Hypertension76, 333–341 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deepa, M. et al. High burden of prediabetes and diabetes in three large cities in South Asia: the Center for cArdio-metabolic Risk Reduction in South Asia (CARRS) Study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract.110, 172–182 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anjana, R. M. et al. Metabolic non-communicable disease health report of India: the ICMR-INDIAB national cross-sectional study (ICMR-INDIAB-17). Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.11, 474–489 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oza-Frank, R. & Narayan, K. M. V. Overweight and diabetes prevalence among US immigrants. Am. J. Public Health100, 661–668 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asmar, R. et al. Therapeutic benefit of a low dose of indapamide: results of a double-blind against placebo European controlled study. Arch. Mal. Coeur Vaiss.88, 1083–1087 (1995). [PubMed]

- 24.Ambrosioni, E. et al. Low-dose antihypertensive therapy with 1.5 mg sustained-release indapamide: results of randomised double-blind controlled studies. European study group. J. Hypertens.16, 1677–1684 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiru, G. et al. Treatment optimisation for blood pressure with single-pill combinations in India (TOPSPIN)—protocol design and baseline characteristics. Int. J. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Risk Prev.23, 200346 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hommel, G. A stagewise rejective multiple test procedure based on a modified Bonferroni test. Biometrika75, 383 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cro, S., Morris, T. P., Kenward, M. G. & Carpenter, J. R. Sensitivity analysis for clinical trials with missing continuous outcome data using controlled multiple imputation: a practical guide. Stat. Med.39, 2815–2842 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austin, P. C., White, I. R., Lee, D. S. & van Buuren, S. Missing data in clinical research: a tutorial on multiple imputation. Can. J. Cardiol.37, 1322–1331 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Tables 1–3, Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

Data Availability Statement

Raw data cannot be publicly shared as per the Health Ministry Screening Committee of the Indian Government (National Regulatory Authority for human research with contributions from other countries), which mandates that no data can be shared beyond the borders without necessary approvals. Anonymized and tabulated or curated data will be made available to bona fide researchers for the purpose of meta-analysis and similar research interests with necessary approvals. Requests may be made to D.P. (dprabhakaran@ccdcindia.org). All such requests will be responded to within a 2-week timeframe.