Abstract

Early detection through screening is critical for reducing gastric cancer (GC) mortality. However, in most high-prevalence regions, large-scale screening remains challenging due to limited resources, low compliance and suboptimal detection rate of upper endoscopic screening. Therefore, there is an urgent need for more efficient screening protocols. Noncontrast computed tomography (CT), routinely performed for clinical purposes, presents a promising avenue for large-scale designed or opportunistic screening. Here we developed the Gastric Cancer Risk Assessment Procedure with Artificial Intelligence (GRAPE), leveraging noncontrast CT and deep learning to identify GC. Our study comprised three phases. First, we developed GRAPE using a cohort from 2 centers in China (3,470 GC and 3,250 non-GC cases) and validated its performance on an internal validation set (1,298 cases, area under curve = 0.970) and an independent external cohort from 16 centers (18,160 cases, area under curve = 0.927). Subgroup analysis showed that the detection rate of GRAPE increased with advancing T stage but was independent of tumor location. Next, we compared the interpretations of GRAPE with those of radiologists and assessed its potential in assisting diagnostic interpretation. Reader studies demonstrated that GRAPE significantly outperformed radiologists, improving sensitivity by 21.8% and specificity by 14.0%, particularly in early-stage GC. Finally, we evaluated GRAPE in real-world opportunistic screening using 78,593 consecutive noncontrast CT scans from a comprehensive cancer center and 2 independent regional hospitals. GRAPE identified persons at high risk with GC detection rates of 24.5% and 17.7% in 2 regional hospitals, with 23.2% and 26.8% of detected cases in T1/T2 stage. Additionally, GRAPE detected GC cases that radiologists had initially missed, enabling earlier diagnosis of GC during follow-up for other diseases. In conclusion, GRAPE demonstrates strong potential for large-scale GC screening, offering a feasible and effective approach for early detection. ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT06614179.

Subject terms: Machine learning, Computed tomography, Cancer screening, Gastric cancer

Artificial intelligence-based detection of gastric cancer at different stages from noncontrast computed tomography is suggested to be feasible in a retrospective analysis of large and diverse cohorts, including real-world populations in opportunistic and targeted screening scenarios.

Main

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide1, with nearly 75% of new cases and related deaths occurring in Asian countries, particularly China, Japan and Korea2,3. Effective screening is crucial to reduce mortality rate as studies show that the 5-year survival rate for early-stage, resectable GC (EGC) is 95–99%, compared with less than 30% for advanced stages (AGC)4,5. Endoscopy is the standard diagnostic test for GC because it allows direct visualization of the gastric mucosa and biopsy sampling for histologic evaluation. Japan and Korea have implemented national GC screening programs via endoscopy since 1983 and 1999, respectively, leading to higher early diagnosis rates and reduced mortality, with survival rates significantly higher in Japan (60.3%) and Korea (68.9%) compared with China (35.9%)6,7.

However, in most countries with high GC prevalence rates, large-scale GC screening in the general population via endoscopy is not feasible or cost-effective, leading to a high mortality rate. This is due mainly to the high cost, suboptimal detection rate (the percentage of detected GC cases out of the total number of people screened) and the invasive nature of endoscopy, resulting in low compliance among the population8. Screening high-risk people is preferable, as they are more likely to undergo endoscopic screening following positive test results. Currently, serological tests, including Helicobacter pylori serology, serum pepsinogen levels and gastrin-17 testing, are the methods used most commonly for identifying people at high risk for GC. However, the detection rate of GC by gastroscopy after serological screening and risk stratification was only 1.25%, showing limited improvement compared with the detection rate of gastroscopy screening in the general population (1.20%)9. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop new noninvasive, low-cost, efficient and reliable screening techniques to identify people at high risk for GC. Such techniques could prioritize endoscopic examinations for high-risk populations, improving cost-effectiveness of large-scale screening programs and ultimately reducing GC-related mortality10.

Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) is a low-cost and widely used imaging protocol in physical examination centers and hospitals (especially in low-resource regions)11,12. Low-dose noncontrast chest CT has become an established diagnostic paradigm for pulmonary nodule surveillance in clinical practice13,14. Noncontrast abdominal CT is usually indicated for rapid diagnosis of acute conditions, evaluating traumatic injuries and assessing patients who have contraindications to contrast agents, which serves as a critical tool for the initial clinical evaluation of abdominal pathologies. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have shown promising results in cancer screening via noncontrast CT, notably in the detection of pancreatic cancer15. Currently, contrast-enhanced CT is used to evaluate GC16, including invasion depth, lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis. However, identifying the primary GC lesion, particularly assessing the invasion depth, is often influenced by stomach filling and gastrointestinal peristalsis. These limitations have hindered the exploration of the role of CT scans in GC evaluation. Routine CT imaging, although a valuable tool for opportunistic screening11, faces substantial challenges in detecting GC. The value of routine CT imaging in GC detection, especially noncontrast CT, has the potential to be explored further by AI.

In this study, we proposed GRAPE (GC risk assessment procedure with AI), using noncontrast CT and deep learning to identify patients with GC. The study was conducted in three distinct phases. First, we developed GRAPE using a cohort from two centers across China, including 3,470 GC cases and 3,250 non-GC (NGC) cases. Its effectiveness and utility were validated using internal validation cohorts (1,298 cases) and an independent external validation cohort from 16 centers (18,160 cases). Then, we compared the interpretations of GRAPE with those of radiologists and explored its potential in assisting radiologists during interpretation. Finally, we validated the performance of GRAPE in opportunistic screening using two real-world study cohorts comprising 78,593 consecutive participants with noncontrast CT from one comprehensive cancer center and two independent regional hospitals. We aim to validate the ability of GRAPE in incidental GC detection in opportunistic screening on routine patients included from various scenarios (physical examination, emergency, inpatient and outpatient department) in the first real-world cohort and on patients treated or being followed up for other cancer in the second real-world cohort (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Overview of the development, evaluation and clinical translation of GRAPE.

a, Model development. GRAPE takes noncontrast CT as input and outputs the probability and the segmentation mask of possible primary gastric lesions. GRAPE was trained with noncontrast CT from gastroscope-confirmed GC patients. The performance of GRAPE was evaluated via GRAPE scores, ROC curves and so on. b, Overview of the training cohort, internal validation cohort and external validation cohort. c, Overview of reader studies. d, Real-word study. The performance of GRAPE in realistic hospital opportunistic screening was validated using two real-world study cohorts, including a regional hospital cohort and a cancer center cohort.

Results

The GRAPE model

The GRAPE model is a deep-learning framework designed to analyze three-dimensional (3D) noncontrast CT scans for GC detection and segmentation. GRAPE was trained on the internal training cohort, including 3,470 GC cases and 3,250 NGC cases (Extended Data Table 1). It generates two outputs: a pixel-level segmentation mask of the stomach and tumors, and a classification score distinguishing GC patients from NGC. The model follows a two-stage approach (Extended Data Fig. 1a). In the first stage, a segmentation network is used to locate the stomach within the full CT scan, generating a segmentation mask that is then used to crop and isolate the stomach region. This cropped region is fed into the second stage, where a joint classification and segmentation network with dual branches is employed. The segmentation branch detects tumors within the identified stomach region, whereas the classification branch integrates multilevel features to classify the patient as either GC-positive or NGC. Detailed description, the architecture and the interpretability analysis of GRAPE are illustrated in Methods and Extended Data Fig. 1.

Extended Data Table 1.

Data characteristics of the GC and non-GC participants in the training cohort, internal validation cohort and external validation cohort

Extended Data Fig. 1. The GRAPE model and its interpretability analysis.

a. Model workflow and architecture. The GRAPE model takes the input of a non-contrast CT scan and first segment the stomach with a U-Net to obtain the ROI of the stomach region. It then processes the ROI region with a joint segmentation and classification network which extracts the multi-level feature of a U-Net backbone and perform classification after global pooling (GP) and fully connected layers (FC). b. Examples of interpretability analysis and three GC cases. The GRAPE model outputs the localization of the detected GC and aligns well with its heatmap visualization via the Grad-CAM approach.

Internal and external evaluation

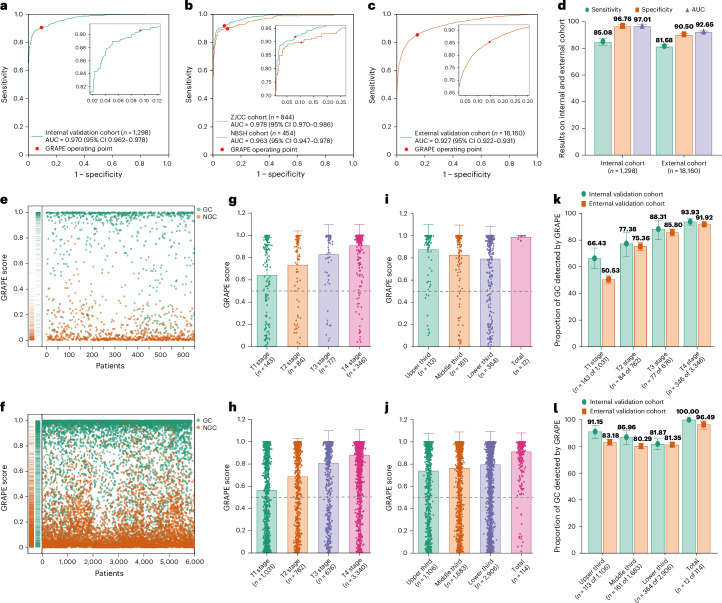

GRAPE achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) of 0.970 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.962–0.978), sensitivity of 0.851 (95% CI 0.825–0.877) and specificity of 0.968 (95% CI 0.953–0.980) in the internal validation cohort (Fig. 2a,d), whereas external validation confirmed stable performance with an AUC of 0.927 (95% CI 0.922–0.931), sensitivity 0.817 (95% CI 0.807–0.827), specificity 0.905 (95% CI 0.900–0.910) (Fig. 2c,d and Extended Data Table 2). No statistically significant differences emerged between Zhejiang Cancer Center (ZJCC) and Ningbo Second Hospital (NBSH) cohorts (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Table 2). Multicenter analysis (n ≥ 100 per center) showed a consistent AUC range of 0.902–0.995 (Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3a and Extended Data Table 2).

Fig. 2. GRAPE performance in internal and external validation cohorts.

a, ROC curve of GRAPE in an internal validation cohort. b, ROC curve of GRAPE in ZJCC and NBSH in internal validation cohort. c, ROC curve of GRAPE in external validation cohort. d, Sensitivity, specificity and AUC of GRAPE in internal and external validation cohorts. e,f, Distribution of GRAPE scores of GC and NGC in the internal (e) and external (f) validation cohorts. g,h, GRAPE scores in different T stages in internal (g) and external (h) validation cohorts. i,j, GRAPE scores in different locations in internal (i) and external (j) validation cohorts. k, Proportion of GC detected by GRAPE in different T stages in internal and external validation cohorts. l, Proportion of GC detected by GRAPE in different locations of the stomach in internal and external validation cohorts.

Extended Data Table 2.

The performance of GRAPE models in internal validation cohort and external validation

Extended Data Fig. 2. ROC curves of individual centers.

The ROC curves show the performance of GRAPE in centers with more than 100 participants in the external validation cohort.

Extended Data Fig. 3. The performance of GRAPE in the internal and external cohorts.

a. The sensitivity, specificity and AUC of GRAPE in centers with more than 100 participants in the external validation cohort. b-e. The sensitivity of GRAPE in GC detection stratified by T stages and tumor locations. f. The sensitivity of GRAPE in GC detection in different status of stomach filing. g. The sensitivity of GRAPE in GC detection stratified by TNM stage. h. The sensitivity of GRAPE in GC detection in patients younger or older than 60. i. The sensitivity of GRAPE in GC detection stratified by sex. Subgroups with less than 10 samples were omitted.

GRAPE score distribution analysis revealed clear differentiation between GC and NGC groups (Fig. 2e,f and Extended Data Table 1), with >0.5 scores predominating in GC. T stage progression showed significant score escalation (Fig. 2g,h), whereas tumor location demonstrated no correlation (Fig. 2g–j). Detection rates increased with T stage advancement in both cohorts. Location-specific analysis showed optimal detection for whole-stomach lesions, with similar performance across different locations (Fig. 2k,l). Sensitivity remained consistent across locations within identical T stages (Extended Data Fig. 3b–e). Notably, well-filled stomachs showed 10.72% higher EGC detection versus poor filling (Extended Data Fig. 3f). Additionally, the detection rate of GC was associated with TNM stage but showed no correlation with gender or age (Extended Data Fig. 3g–i).

Reader studies

In a multicenter reader study (n = 13 radiologists) interpreting 297 noncontrast CT scans, GRAPE surpassed all readers in diagnostic accuracy (AUC, GRAPE 0.92 versus readers’ range 0.76–0.85), demonstrating significant performance advantages in both sensitivity and specificity. When reassessing cases with AI assistance after a ≥1-month washout, radiologists achieved mean improvements of 6.6% sensitivity and 13.3% specificity. Notably, while both senior and junior radiologists showed significant accuracy gains (P < 0.05), their augmented performance remained below GRAPE’s standalone results (Fig. 3a–c).

Fig. 3. Reader study.

a, Comparison between GRAPE and 13 readers with 13 radiologists with different levels of expertise on GC. b, Performance in GC discrimination of the same set of radiologists with the assistance of GRAPE on noncontrast CT. c, Balanced accuracy improvement in radiologists with different levels of expertise for GC discrimination. d, Detection rate of EGC and AGC by radiologists alone, radiologists with the assistance of GRAPE and GRAPE alone. e, Detection rate of GC in different locations by radiologists alone, radiologists with the assistance of GRAPE and GRAPE alone. f, Examples of T1 and T2 GC discrimination by GRAPE, which were missed by readers.

We then analyzed the proportion of GC detected by GRAPE, radiologists alone and radiologist with GRAPE assistant in EGC and AGC. GRAPE showed a higher proportion of EGC detected compared with radiologists alone or with GRAPE assistance (Fig. 3d). We also found that GRAPE performed significantly better in the middle-third location compared with radiologists alone or with GRAPE assistance (Fig. 3e), which may result from the difficulty in identifying GC at this location with various degrees of stomach filling. Figure 3f shows that representative CT scans of T1/T2 stage GC that radiologists failed to identify.

Real-world study of hospital opportunistic screening

We further validated the performance of GRAPE in opportunistic screening using two real-world study cohorts comprising 78,593 consecutive participants with noncontrast CT between 2018 and 2024 from two independent regional hospitals and one comprehensive cancer center.

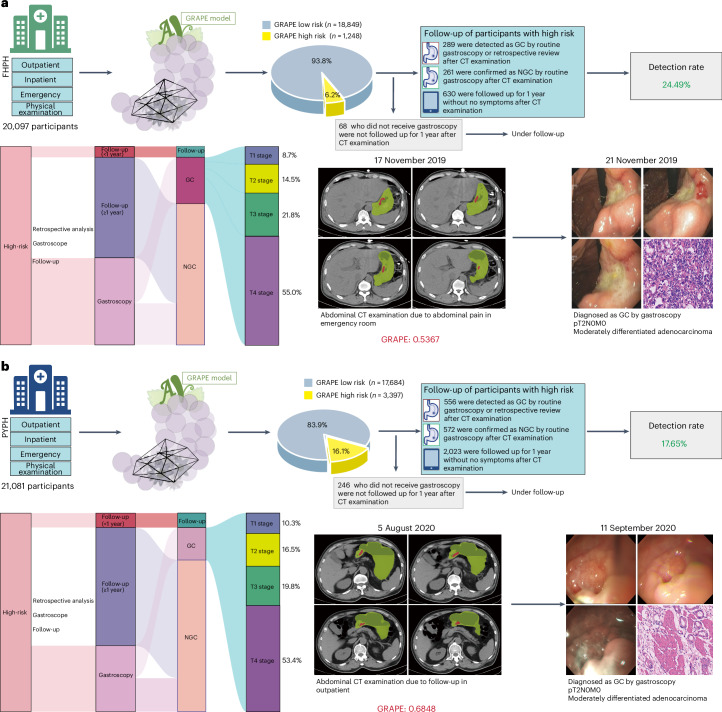

First, we validated the opportunistic screening capacity of GRAPE in a real-world cohort comprising 41,178 routine patients from diverse clinical settings (physical examination, emergency, inpatient and outpatient departments) across regional hospitals. GRAPE identified 11.28% (4,645) as high risk, with distinct proportions across cohorts: 6.2% (1,248 of 20,097) in Fenghua Peopleʼs Hospital (FHPH) versus 16.1% (3,397 of 21,081) in Pinyang Peopleʼs Hospital (PYPH) (Fig. 4). Through comprehensive medical record review and follow-up, we stratified GRAPE-identified high-risk patients into four clinical trajectories: confirmed GC via gastroscopy, NGC diagnoses, asymptomatic patients with 1-year follow-up and those lacking both gastroscopy and follow-up documentation. Finally, among the high-risk population, gastroscopic and follow-up verification revealed that 289 GC cases were confirmed in FHPH, while 556 GC in PYPH (Fig. 4a,b and Extended Data Table 4). The detection rate was 24.49% (289 of 1,180) and 17.65% (556 of 3,151) in FHPH and PYPH, respectively. Furthermore, we retrospectively analyzed the patients with confirmed GC in the ‘high-risk’ population and found that 40.48% (117 of 289) and 38.31% (213 of 556) patients did not have abdominal symptoms in FHPH and PYPH, respectively. The multidisciplinary team (MDT) searched and reviewed the available electronical health record of low-risk patients in the FHPH and PYPH cohorts, including all existing follow-up information, and found 37 and 49 GCs patients, respectively, confirmed by pathology. Thus, the estimated sensitivity and specificity are 0.887 (95% CI 0.850–0.920) and 0.951 (95% CI 0.949–0.954) for the FHPH cohort, and 0.919 (95% CI 0.899–0.939) and 0.861 (95% CI 0.857–0.866) for the PYPH cohort, respectively.

Fig. 4. Performance of GRAPE in realistic hospital opportunistic screening in regional hospitals validated using a real-world study cohort.

a, Overview of GRAPE’s performance in FHPH cohort and a case study. b, Overview of GRAPE’s performance in PYPH cohort and a case study.

Extended Data Table 4.

Data characteristics of the GRAPE-high risk group in the real world study

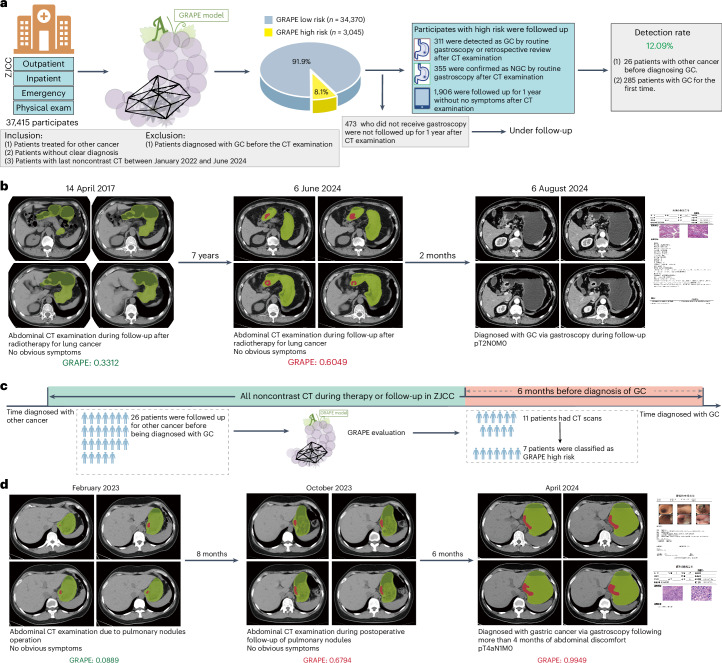

Next, we aimed to validate the ability of GRAPE in GC detection on a comprehensive cancer center, where most patients were diagnosed with or suspected of having tumors. We consecutively collected the abdominal noncontrast CT between January 2022 and June 2024 from ZJCC. GRAPE identified 8.1% (3,045) as high risk. Comprehensive medical review stratified that 311 GC cases were confirmed (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Table 4), including 34.41% (107 of 311) patients without obvious abdominal symptoms. The overall detection rate was 12.1%. Notably, one patient was predicted high risk by GRAPE on an abdominal noncontrast CT scan in June 2024. MDT review showed that the patient underwent gastroscopy, and was diagnosed as GC in August 2024. Surgical pathology confirmed the GC was pT2N0M0 (AJCC Stage IB) (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5. Performance of GRAPE in realistic hospital opportunistic screening in cancer center validated using a real-world study cohort.

a, Overview of GRAPE’s performance in the ZJCC cohort. b, Illustration of GC patient diagnosed after detection using GRAPE. This patient was being followed up for lung cancer treatment in June 2024 but was detected by GRAPE. MDT review showed that the patient underwent gastroscopy and was diagnosed with moderately differentiated to well-differentiated GC in August 2024. c, Data collection process of prediagnosis CT scans. Among 26 patients under follow-up for other cancers, 11 had prediagnostic CT scans taken in the 6 months before GC diagnosis. GRAPE suggested GC in 63.64% (7 of 11) patients in the 6 months before their diagnosis. d, A patient underwent 2 abdominal CT examinations at 14 and 6 months before diagnosis of GC due to pulmonary nodules, with no notable abnormalities of stomach reported in 2023. Later, this patient was diagnosed with poorly differentiated GC in T4aN1M0 stage via gastroscopy after more than 4 months of abdominal discomfort in April 2024. We evaluated the noncontrast CT before and at the time of diagnosis, and the results showed that the GRAPE indicated GC in noncontrast CT 6 months before diagnoses. Based on the GRAPE prediction and retrospective review of the image, the MDT suspected the patient was in stage T2, which was detected successfully by GRAPE 6 months in advance.

We validated the ability of GRAPE in early diagnosis. Among 311 GC cases in the second real-world cohort (ZJCC), 26 patients were under follow-up, being reviewed or under treatment for other cancer, whereas the other 285 patients visited the hospital for the first time before diagnoses with GC. Among the 26 patients, 11 had prediagnostic abdominal noncontrast CT scans taken during the 6 months before GC diagnosis. GRAPE was tested on 11 prediagnostic scans and predicted GC in 63.64% (7 of 11) patients (Fig. 5c). A patient underwent two abdominal CT examinations at 14 and 6 months before diagnosis of GC due to pulmonary nodules, with no notable abnormalities of stomach reported in 2023. Later, this patient was diagnosed with poorly differentiated GC in T4aN1M0 stage via gastroscopy after more than 4 months of abdominal discomfort in April 2024. We evaluated the noncontrast CT before and at the time of diagnosis and the results showed that the GRAPE indicated GC in noncontrast CT 6 months before diagnoses. Based on the GRAPE prediction and retrospective review of the image, the MDT suspected the patient was in stage T2, which was detected successfully by GRAPE 6 months in advance (Fig. 5d).

Discussion

CT provides a comprehensive and objective evaluation of anatomical structures, irrespective of clinical indications, establishing its significance as an effective cancer detection tool17. The emergence of AI methods has enabled the automatic segmentation and processing of underutilized data through deep learning, facilitating fast, objective algorithms for accurate lesion identification18,19. In this study, we present GRAPE: an AI model based on routine noncontrast CT scans for GC detection. The effectiveness of this model was further validated in an independent, external multicenter study. GRAPE demonstrated superior detection performance for GC compared with previous models based on clinical information and serological diagnostics (AUC 0.757–0.79)20–22, and the performance was comparable to liquid biopsy23,24, including circular RNAs25, microRNAs26,27, cell-free DNA28 and metabolites23 in blood samples, which reported AUC values between 0.83 and 0.94. The subgroup analysis demonstrated GRAPE sensitivity of approximately 50% for EGC, and more than 90% for GC at T3 and T4 stages. Although GRAPE demonstrated superior performance in advanced GC detection, it may allow GC to be detected at an earlier stage, which can also improve the overall survival of GC patients.

To validate the value of GRAPE in realistic hospital opportunistic screening, we conducted two real-world studies comprising 78,593 consecutive participants. GRAPE achieved high detection rates, significantly surpassing the 0.9% detection rate of all GC from questionnaire-based methods29. GRAPE also showed good performance on prediagnosis scans performed in the 6 months before GC diagnosis. Despite its advantage, GRAPE is not intended to replace endoscopic evaluation. We believe it provides a valuable alternative for symptomatic patients hesitant to undergo initial endoscopic screening.

Currently, no other new GC screening methods have been implemented in large-scale screening cohorts, although similar studies have been conducted for other malignancies. The National Lung Screening Trial in the United States reported a lung cancer detection rate of 2.4–5.2% using low-dose helical CT30. The detection rate of ovarian and fallopian tube cancers was 5.5% using transvaginal ultrasound31. In liquid screening, the detection rate of nasopharyngeal carcinoma was 11.0% using Epstein–Barr virus DNA levels in plasma samples32, and the detection rate of colorectal cancer was 3.2% via cell-free DNA detection in plasma in the theoretical ECLIPSE study population33. As a highly accurate high-risk identification tool, GRAPE has the potential to enable large-scale screening programs by boosting the detection rate for the secondary endoscopy examinations, thus reducing GC mortality.

The GRAPE model adopts a simple yet effective architecture to the detection of GC on noncontrast CT scans by integrating both classification and segmentation into a single deep-learning framework. Traditional methods often fall short by focusing solely on segmentation, which limits the ability to provide patient-level probability assessments, or by relying exclusively on classification approaches applied directly to organ regions of interest (ROIs), thereby reducing the interpretability of predictions. In contrast, our joint model leverages the advantages of both strategies, allowing us to benefit from detailed local textural pattern recognition of tumors while maintaining a comprehensive understanding of the stomach’s overall shape and structure. By adapting the nnUNet backbone—a proven architecture known for its robust and high-performance visual feature extraction capabilities—our model achieved enhanced capacity to handle the complex visual characteristics present in medical images specific to GC. GRAPE’s overall design not only ensures efficient feature learning but also offers improved generalization across diverse datasets. Moreover, in terms of interpretability, GRAPE combined segmentation and classification pipeline, providing clinicians with detailed images where tumor segmentation masks are explicitly delineated while simultaneously offering decisive classification outputs. We also visually analyzed interpretability through Grad-CAM and found the coarse heatmap corresponded well with the tumor region. Although noncontrast CT is not a routine modality for GC diagnosis, the performance of radiologists can be improved significantly via the assistance of GRAPE. This improvement could be attributed to GRAPE’s tumor segmentation output, which is easy for radiologists to interpret.

Despite GRAPE’s promising results, further research is required to address key aspects of its applicability. First, a large prospective screening cohort is necessary to validate GRAPE’s effectiveness in GC screening more robustly. We are implementing large-scale prospective validation of GRAPE’s performance through a nationwide GC screening program. Due to scenario difference, for example, high-risk versus opportunistic screening, the optimal cutoff value is expected to be selected to balance the sensitivity and specificity during clinical implementation. Second, enhancing the sensitivity of the model for early-stage GC remains a priority. We will amplify the training dataset of GRAPE with more EGC, thereby improving model sensitivity. We will also utilize more information from endoscopic and pathology reports as additional supervision to train the GRAPE model to further improve sensitivity, for example, the description of shape, texture, size and degree of invasion of the tumor. As mentioned before, patients with better gastric filling had higher sensitivity in early GC detection. As a result, we would recommend distension of the stomach before noncontrast CT imaging in our prospective trial. Third, although the prevalence of non-GC tumors such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors and gut-associated lymphoid tissue tumors are relatively low, GRAPE could be expanded to detect and diagnose these rare tumors, making it a more comprehensive screening tool. Finally, to address generalization challenges, future direction would be the incorporation of training data from more centers. From the technical aspect, the test-time adaptation34 technique is a recent machine-learning approach for better model generalizability and has the potential to boost external validation performance for GRAPE. Overall, GRAPE represents a new approach for mass GC screening, demonstrating high sensitivity, specificity and detection rates, thus enhancing both the cost-effectiveness and compliance of GC screening efforts.

Methods

Trial design and population

This study employed a phase design and included three independent cohorts (Fig. 1). The study was approved by the centralized institutional review board (IRB) covering 20 participating centers (IRB-2024-279, Clinicaltrials.gov registration NCT06614179). The training cohort was enrolled between September 2006 and June 2024 across 2 centers in China, comprising 3,470 participants with GC and 3,250 participants with NGC, aged 18–99 years. The internal validation cohort was enrolled between December 2006 and April 2024 across 2 centers in China, comprising 650 participants with GC and 648 participants with NGC, aged 20–94 years. Moreover, between January 2011 and August 2024, we conducted an independent external validation cohort, enrolled 18,160 participants from 16 centers who underwent gastroscopic examination, aged 18–80 years. The inclusion criteria for the GC group required participants to have a diagnosis of GC confirmed by gastroscopic pathological biopsy and to have undergone a noncontrast CT examination before receiving any treatment at the time of diagnosis. Participants were excluded if they underwent the noncontrast CT examination after receiving treatment. For the NGC group, inclusion criteria required participants to be confirmed as not having GC by gastroscopy and to have undergone a noncontrast CT examination within 6 months of the gastroscopy. Alternatively, NGC participants were included if they underwent a noncontrast CT examination and were confirmed without GC based on a 1-year follow-up. We conducted a comprehensive review of the medical records for all enrolled patients, including age, sex, T stage, location and so on. Full details of the internal and external cohorts, including patients’ clinical information and CT acquisition parameters, are shown in Extended Data Table 1.

Finally, we validated the performance of GRAPE in realistic hospital opportunistic screening using 2 real-world study cohorts, including a cohort comprising 41,178 consecutive participants with noncontrast CT between 2018 and 2024 from 2 regional hospitals and a cohort comprising 37,415 participants with last noncontrast CT between 2022 and 2024 from a cancer center. In total, 45.19% (9,083 of 20,097) patients came from the outpatient and emergency departments and physical examination center, while 54.80% (11,014 of 20,097) patients came from department of inpatient in FHPH; 41.56% (8,761 of 21,081) patients came from the outpatient and emergency departments and physical examination center, whereas 58.44% (12,320 of 21,081) patients came from the inpatient department in PYPH. In ZJCC, we additionally excluded 4,573 patients diagnosed with GC before routine CT examination. In total, 30.66% (11,472 of 37,415) patients came from the outpatient and emergency departments and physical examination center, while 39.34% (25,943 of 37,415) patients came from the inpatient department.

Image acquisition and processing

CT images in the training cohort, internal validation cohort and external validation cohort were collected before gastroscopy. Stomach segmentation was obtained via a semi-supervised self-training approach using a combination of publicly available dataset35 with manually annotated masks and our internal training set. Tumor segmentation was performed meticulously by two proficient radiologists using ITK-SNAP software (v.3.8, available at http://www.itksnap.org)36. As GC can be distinguished readily from normal gastric tissues in portal venous-phase CT images, we delineated two-dimensional sections containing tumors to effectively outline tumor boundaries in venous-phase CT images. In cases where marked discrepancies in the delineation of the ROI arose between the two radiologists, resolution was achieved through constructive discussion, resulting in a consensus. To obtain tumor annotations on noncontrast images, we employed the DEEDS37 registration algorithm to align venous-phase images with noncontrast images. The resulting deformation fields were then applied to the annotations on the venous phase, thereby generating the transformed tumor annotations for the noncontrast phase. Finally, the transferred tumor annotations on the noncontrast phase were again delineated and confirmed via the same procedure as on the venous phase.

AI model: GRAPE

GRAPE model was developed to analyze 3D noncontrast CT scans aimed at the detection and segmentation of GC. The model yields two outputs: a pixel-level segmentation mask outlining the stomach and potential tumors, and a classification score that categorizes patients into those with GC and normal controls. The model employs a two-stage strategy. The first stage involves the localization of the stomach region within the entire CT scan. This stage is implemented using a segmentation network, nnUNet38, with the configuration for 3D full resolution. The output stomach segmentation mask is used to generate a 3D bounding box of the stomach region, which is cropped and served as input for the second stage. This cropping enhances the efficiency and simplification of the subsequent stage by focusing the tumor segmentation specifically on the area of interest. In the second stage, a joint classification and segmentation network with dual branches is employed. The segmentation branch focuses on segmenting tumors in this identified stomach region. Meanwhile, the classification branch, which integrates multilevel feature maps from the segmentation branch, is designed to classify the patients as either having GC or as normal controls. Whereas noncontrast CT has inherent resolution limitations (~0.5–1 mm), GRAPE detects early GCs not through direct lesion visualization but by integrating subtle 3D morphometric patterns (for example, local wall thickening, mucosal heterogeneity) and contextual radiological features (for example, perigastric fat stranding, lymph node microcalcifications).

To address variations in CT imaging parameters across several centers, we adopted a robust preprocessing pipeline as follows. First, all scans were resampled to the median voxel spacing of the training dataset, specifically 0.717 mm × 0.717 mm × 5.0 mm, to harmonize differences in slice thickness and spatial resolution. Next, all intensity values were normalized using the mean and s.d. calculated from the training dataset to minimize interscanner intensity discrepancies. During training, fixed-size 3D patches with a size of 256 × 256 × 28 were extracted randomly from the resampled volumes, and random Gaussian noise was injected before feeding into the deep network to increase model robustness. At test time, predictions were generated using a sliding window strategy across the entire resampled volume, ensuring consistent performance regardless of original scan dimensions.

The training procedure involved a fivefold cross-validation approach by dividing the training set into five folds. Five models were trained individually using four folds, with validation on the one remaining fold, following the standard nnUNet cross-validation protocol. In the testing phase, ensemble learning was applied, averaging classification probabilities across five models to determine the classification score, and using pixel-level voting to determine segmentation output. The class with the higher probability between the two categories was chosen as the final classification for each test case. In addition, different status of stomach filling is challenging for the recognition of GC. GRAPE inherently addresses stomach filling variability through comprehensive training on a wide range of gastric volumes (fasting, <100 cm3 to over-distended, >800 cm3).

An advantage of the GRAPE model is its inherent interpretability. Given that it produces both segmentation and classification outputs, the segmentation output provides a pixel-level visual map that aids in understanding and confirming the classification results. To further enhance interpretability, we visualized the heatmap of the convolutional feature map in the classification branch using Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping)39, which is a widely applicable technique to identify the regions contribute most importantly to the classification.

Evaluation metrics

Our main goal is a binary classification task to determine whether a patient has GC. A GRAPE score greater than 0.5 is considered as the ‘high risk’ category for calculating AUC, sensitivity, specificity and accuracy. Furthermore, we access the proportion of GC detection stratified by T stage, TNM stage, lesion location and stomach filling during CT examination.

Reader studies

The aim of the reader study was to assess the difference in performance between GRAPE and radiologists in detecting GC on noncontrast CT. A total of 13 radiologists were enrolled in this study, comprising 5 senior radiologists and 8 junior radiologists. Details of the radiologists is shown in Extended Data Table 3. The study comprised two sessions. In the first session, GRAPE’s performance was compared with that of radiologists with varying levels of expertise in GC imaging. The second session evaluated GRAPE’s potential to assist radiologists where we provided the radiologists with GRAPE’s prediction in addition to the noncontrast image. A washout period of at least 1 month was maintained between the 2 sessions for each radiologist.

Extended Data Table 3.

Reader experience

Readers were stratified into senior vs. junior radiologists endorsed by the National Health Commission’s Physician Title Evaluation Standards (2021 Edition) and the Chinese Medical Association Radiology Branch certification guidelines. Senior status required either: (1) attainment of associate chief physician or higher academic rank; or (2) accumulated ≥8 years of independent diagnostic reporting experience, as verified through institutional credentialing databases.

Statistical analysis

The performance of the GC and NGC classification was evaluated using the AUC, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and balanced accuracy. Confidence intervals were calculated based on 1,000 bootstrap replications of the corresponding data. The significance comparisons of sensitivity, specificity and balanced accuracy were conducted using permutation tests to calculate two-sided P values with 10,000 permutations. The threshold to determine statistical significance is P < 0.05. Data analysis was conducted in Python using the numpy (v.1.26.2), scipy (v.1.11.4) and scikit-learn (v.1.3.2) packages.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41591-025-03785-6.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the International Scientific and Technological Cooperation Base for tumor molecular diagnosis and intelligent screening. X.C. was supported by The National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA0910100) and Healthy Zhejiang One Million People Cohort (K-20230085). C.H. was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82304946), postdoctoral Innovative Talent Support Program (BX2023375), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M733563) and Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LMS25H160006). Z.X. was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82473489), Medical Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (WKJ-ZJ-2323) and Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LBD24H290001); S.P. was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82403546).

Extended data

Author contributions

X.C., Ling Zhang, C.H., Y.X. and Z.X. conceived of and designed the study. C.H., M.C., G. Zheng, S.C., J.S., W.C., Q.Z., S.P., Y.Z., J. Chen, P.Y., Jingli Xu, C.G., X.K., K.C., Z.W., G. Zhu, J.Q., Y.P., H.L., X.G., Z.Y., W.A., Lei Zhang, X. Yan, Y.T., X. Yang, X. Zheng, S.F., J. Cao, C.Y., K.X., Yao Wang, L. Zheng, Y. Wu, Z.G., X.T., X. Zhang, Yan Wang, R.Z., Y. Wei, W.Z., H.Q., M.S., S.Z. and L.S. carried out data acquisition. C.H., Y.X., Z.Z., M.C., Jianwei Xu, Z.Q., T.L., B.Y., J.Y. and W.G. carried out the data preprocessing. Y.X. and Z.Z. developed the AI model. C.H., Y.X., Z.Z., M.C., Jianwei Xu, Z.Q., T.L., B.Y., W.G., L.S., Z.X., Ling Zhang, J.Z. and X.C. analyzed and interpreted the data. X.C., Z.X. and C.H. carried out the clinical deployment. C.H., Y.X., Z.Z., M.C., Jianwei Xu, Z.Q., T.L., B.Y. and W.G. carried out the statistical analysis. C.H., Y.X. and Z.Z. wrote and revised the paper.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Florian Lordick and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Lorenzo Righetto, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are not publicly available due to restrictions imposed by the respective IRBs. Researchers may request access to the anonymized data and supporting clinical documentation by contacting corresponding author X.C. (chengxd@zjcc.org.cn). Access will be granted subject to IRB approval, a signed data-use agreement and will be for noncommercial academic purposes only. Requests will be processed within 6 weeks.

Code availability

The code used for the implementation of GRAPE has dependencies on internal tooling and infrastructure and is under patent protection (CN116188392; the other application number is not currently in the public domain), and thus is not able to be publicly released. All experiments and implementation details are described in sufficient detail in Methods to support replication with nonproprietary libraries. Several principal components of GRAPE are available in open-source repositories: PyTorch (https://pytorch.org/,v2.2.0) and nnU-NetV1 (https://github.com/MIC-DKFZ/nnUNet/tree/nnunetv1).

Competing interests

Alibaba Group has filed for patent protection (CN116188392; the other application number is not currently in the public domain) for the work related to the methods of detection of GC in noncontrast CT. Y.X., Z.Z., Jianwei Xu, Z.Q., T.L., B.Y., J.Y., W.G., J.Z. and Ling Zhang are employees of Alibaba Group and own Alibaba stock as part of the standard compensation package. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Can Hu, Yingda Xia, Zhilin Zheng, Mengxuan Cao, Guoliang Zheng, Shangqi Chen, Jiancheng Sun.

Contributor Information

Hanjun Qiu, Email: 289971282@qq.com.

Miaoguang Su, Email: 39265825@qq.com.

Lei Shi, Email: shilei@zjcc.org.cn.

Zhiyuan Xu, Email: xuzy@zjcc.org.cn.

Ling Zhang, Email: ling.z@alibaba-inc.com.

Xiangdong Cheng, Email: chengxd@zjcc.org.cn.

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41591-025-03785-6.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41591-025-03785-6.

References

- 1.Smyth, E. C., Nilsson, M., Grabsch, H. I., van Grieken, N. C. & Lordick, F. Gastric cancer. Lancet396, 635–648 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold, M. et al. Is gastric cancer becoming a rare disease? A global assessment of predicted incidence trends to 2035. Gut69, 823–829 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin, J.-L. et al. Global incidence and mortality trends of gastric cancer and predicted mortality of gastric cancer by 2035. BMC Public Health24, 1763 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xia, J. Y. & Aadam, A. A. Advances in screening and detection of gastric cancer. J. Surg. Oncol.125, 1104–1109 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang, Y. et al. Predicting peritoneal recurrence and disease-free survival from CT images in gastric cancer with multitask deep learning: a retrospective study. Lancet Digit Health4, e340–e350 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun, D. et al. The effect of nationwide organized cancer screening programs on gastric cancer mortality: a synthetic control study. Gastroenterology166, 503–514 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allemani, C. et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet391, 1023–1075 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia, R. et al. Estimated cost-effectiveness of endoscopic screening for upper gastrointestinal tract cancer in high-risk areas in China. JAMA Netw. Open4, e2121403 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu, Y. et al. Performance evaluation of four prediction models for risk stratification in gastric cancer screening among a high-risk population in China. Gastric Cancer24, 1194–1202 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, Z. et al. Nationwide gastric cancer prevention in China, 2021–2035: a decision analysis on effect, affordability and cost-effectiveness optimisation. Gut71, 2391–2400 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickhardt, P. J. et al. Opportunistic screening: radiology scientific expert panel. Radiology307, e222044 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pickhardt, P. J. et al. Automated CT biomarkers for opportunistic prediction of future cardiovascular events and mortality in an asymptomatic screening population: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Digit Health2, e192–e200 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McWilliams, A. et al. Probability of cancer in pulmonary nodules detected on first screening CT. N. Engl. J. Med.369, 910–919 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prosper, A. E., Kammer, M. N., Maldonado, F., Aberle, D. R. & Hsu, W. Expanding role of advanced image analysis in CT-detected indeterminate pulmonary nodules and early lung cancer characterization. Radiology309, e222904 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao, K. et al. Large-scale pancreatic cancer detection via non-contrast CT and deep learning. Nat. Med.29, 3033–3043 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang, Y. et al. Radiographical assessment of tumour stroma and treatment outcomes using deep learning: a retrospective, multicohort study. Lancet Digit Health3, e371–e382 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillies, R. J. & Schabath, M. B. Radiomics improves cancer screening and early detection. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev.29, 2556–2567 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, Z., Liu, Y. & Niu, X. Application of artificial intelligence for improving early detection and prediction of therapeutic outcomes for gastric cancer in the era of precision oncology. Semin Cancer Biol.93, 83–96 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moor, M. et al. Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence. Nature616, 259–265 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, Z., Mo, T.-M., Tian, L. & Chen, J.-Q. Gastrin-17 combined with CEA, CA12-5 and CA19-9 improves the sensitivity for the diagnosis of gastric cancer. Int J. Gen. Med14, 8087–8095 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorscher, S. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer screening. J. Clin. Oncol.42, 3162–3163 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai, Q. et al. Development and validation of a prediction rule for estimating gastric cancer risk in the Chinese high-risk population: a nationwide multicentre study. Gut68, 1576–1587 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu, Z. et al. Efficient plasma metabolic fingerprinting as a novel tool for diagnosis and prognosis of gastric cancer: a large-scale, multicentre study. Gut72, 2051–2067 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu, P. et al. Genomic and immune microenvironment features influencing chemoimmunotherapy response in gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis: a retrospective cohort study. Int J. Surg.110, 3504–3517 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy, S. et al. Diagnostic efficacy of circular RNAs as noninvasive, liquid biopsy biomarkers for early detection of gastric cancer. Mol. Cancer21, 42 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.So, J. B. Y. et al. Development and validation of a serum microRNA biomarker panel for detecting gastric cancer in a high-risk population. Gut70, 829–837 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mok, J. W., Oh, Y. H., Magge, D. & Padmanabhan, S. Racial disparities of gastric cancer in the USA: an overview of epidemiology, global screening guidelines, and targeted screening in a heterogeneous population. Gastric Cancer27, 426–438 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu, P. et al. Multi-dimensional cell-free DNA-based liquid biopsy for sensitive early detection of gastric cancer. Genome Med16, 79 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu, X. et al. Development, validation, and evaluation of a risk assessment tool for personalized screening of gastric cancer in Chinese populations. BMC Med21, 159 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aberle, D. R. et al. Results of the two incidence screenings in the National Lung Screening Trial. N. Engl. J. Med.369, 920–931 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menon, U. et al. Sensitivity and specificity of multimodal and ultrasound screening for ovarian cancer, and stage distribution of detected cancers: results of the prevalence screen of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). Lancet Oncol.10, 327–340 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan, K. C. A. et al. Analysis of plasma Epstein–Barr virus DNA to screen for nasopharyngeal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.377, 513–522 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung, D. C. et al. A cell-free DNA blood-based test for colorectal cancer screening. N. Engl. J. Med.390, 973–983 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, M., Levine, S. & Finn, C. Memo: test time robustness via adaptation and augmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst.35, 38629–38642 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibson, E. et al. Automatic multi-organ segmentation on abdominal CT with dense V-networks. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging37, 1822–1834 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yushkevich, P. A., Yang, G. & Gerig, G. ITK-SNAP: an interactive tool for semi-automatic segmentation of multi-modality biomedical images. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc.2016, 3342–3345 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heinrich, M. P., Jenkinson, M., Brady, M. & Schnabel, J. A. MRF-based deformable registration and ventilation estimation of lung CT. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging32, 1239–1248 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isensee, F., Jaeger, P. F., Kohl, S. A. A., Petersen, J. & Maier-Hein, K. H. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods18, 203–211 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang, H. & Ogasawara, K. Grad-CAM-based explainable artificial intelligence related to medical text processing. Bioengineering10, 1070 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are not publicly available due to restrictions imposed by the respective IRBs. Researchers may request access to the anonymized data and supporting clinical documentation by contacting corresponding author X.C. (chengxd@zjcc.org.cn). Access will be granted subject to IRB approval, a signed data-use agreement and will be for noncommercial academic purposes only. Requests will be processed within 6 weeks.

The code used for the implementation of GRAPE has dependencies on internal tooling and infrastructure and is under patent protection (CN116188392; the other application number is not currently in the public domain), and thus is not able to be publicly released. All experiments and implementation details are described in sufficient detail in Methods to support replication with nonproprietary libraries. Several principal components of GRAPE are available in open-source repositories: PyTorch (https://pytorch.org/,v2.2.0) and nnU-NetV1 (https://github.com/MIC-DKFZ/nnUNet/tree/nnunetv1).