Abstract

Purpose

To determine the characteristics and outcome of patients with refractory gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) after primary chemotherapy (CTx).

Methods

The outcome of low- and high-risk patients with refractory GTN (n = 14, 37%) was compared to those with non-refractory GTN (n = 24, 63%). Methotrexate treatment was used for patients with low-risk disease and EMA/CO for patients with high-risk disease.

Results

Median follow-up time was 53 months (range 1–173 months). All non-refractory patients and 11 refractory patients (79%) survived (p = 0.015). Factors related to resistance to primary CTx was age (p = 0.012), duration between causal pregnancy and initial treatment (p = 0.003), surgery (p = 0.014), hCG level before CTx (p = 0.09) and half-life of hCG (p = 0.061). Six out of 10 low-risk refractory patients treated with EMA/CO regimen in the second-line setting had been followed by no evidence of disease. Nine of 38 (24%) patients underwent surgery (TAH ± BSO) for GTN. All of the patients treated with surgery were in the non-refractory group, but none of refractory patients underwent surgery (p = 0.014).

Conclusions

Surgery and EMA/CO regimen are one of the main factors that play a role in the management of refractory low-risk GTN.

Keywords: Gestational trophoblastic disease, Refractory, EMA/CO, Surgery

Introduction

Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) is a spectrum of cellular proliferations arising from the placental villous trophoblast encompassing 4 main clinicopathologic forms: hydatidiform mole (complete and partial), invasive mole, choriocarcinoma and placental site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT). The term “gestational trophoblastic neoplasia” (GTN) has been applied collectively to the latter 3 conditions, which can progress, invade, metastasize and lead to death (Lurain 2010). The incidence of GTD differs widely in different regions of the world, for example, in Netherlands, the incidence is 1.34/1,000 deliveries, while in Brazil, the incidence is 8.5/1,000 deliveries (Lybol et al. 2011; Soares et al. 2010). Highest incidence of 12.1/1,000 deliveries is reported from Turkey (Harma et al. 2005).

The outcomes for GTN were poor before the introduction of chemotherapy into their management approximately 50 years ago. The mortality rate for invasive mole approached 15%, most often due to sepsis, hemorrhage, embolic phenomena, or complications from surgery. Mortality from metastatic choriocarcinoma approached 100% and was still 60% when hysterectomy was done for apparent non-metastatic disease (Hoekstra et al. 2008). As a result of effective chemotherapy (CTx), the ability to monitor treatment response with human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels and individualization of CTx based on prognostic factors, GTN has become a highly curable tumor (Feng et al. 2010; Eiriksson et al. 2012; Alazzam et al. 2011). Although the overall survival of patients receiving CTx is high (>90%) (Feng et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2008; Tse et al. 2008; Lurain and Nejad 2005), this is dependent on the risk of developing resistance to CTx determined by the Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO) scoring system (Seckl et al. 2010). Patients scored as low risk that were treated with methotrexate (mtx) and folinic acid have a excellent survival rate (nearly 100%), but a third of the patients required second-line CT with either a single-agent actinomycin D or a combination CTx such as etoposide, mtx and actinomycin D alternating with cyclophosphamide and vincristine (EMA/CO) (McNeish et al. 2002; Osborne et al. 2011). Patients that have a high-risk score (score ≥ 7) can receive EMA/CO as first-line therapy and have a survival rate of approximately 90% (Bower et al. 1997; Chauhan et al. 2010; Lurain et al. 2010). Kim et. al reported a retrospective, comparative study in which 227 high-risk GTT patients were treated with four different chemotherapy regimens in the period 1971–1995 [these regimens were methotrexate, folinic acid and actinomycin D; MAC (methotrexate, actinomycin D and cyclophosphamide); CHAMOCA (cyclophosphamide, hydroxyurea, actinomycin D, methotrexate, vincristine, leucovorin and doxorubicin); EMA-CO]. The remission rate of the EMA-CO regimen was 90.6% (87/96). However, the remission rates of the other regimens of MTX plus folinic acid plus actinomycin D, MAC and CHAMOCA were 63.3% (31/49), 67.5% (27/40) and 76.2% (32/45), respectively (Kim et al. 1998a, b). There are no randomized controlled trials comparing EMA-CO chemotherapy with any other combination chemotherapies.

Despite the success of CTx, when inducing clinical complete responses in most patients with GTN, approximately 5% of low-risk patients and 25% of high-risk patients will have an incomplete response to the first-line sequential single-agent or multi-agent CTx, respectively, or will relapse after achieving remission (Lurain and Nejad 2005). To date, there is limited data comparing patients with non-refractory and refractory GTN after a failure of first-line CTx. In addition, the role of surgery in refractory patients is still undefined. In this study, we analyzed and evaluated the treatment outcomes of patients with non-refractory and refractory GTN.

Patients and methods

This retrospective study was conducted between April 9, 1996, and October 23, 2009, at the Department of Medical Oncology, Institute of Oncology, University of Istanbul. The cutoff date of follow-up was October 1, 2010. The patient records were screened for patients who had primary refractory or non-refractory GTN during primary CTx. Evaluated parameters were age, antecedent pregnancy, interval months from index pregnancy, largest tumor size including uterus, site of metastasis, number of metastasis, pretreatment serum hCG level, hCG half-life, FIGO prognostic score, stage, type of CTx, treatments of refractory disease, duration of treatments, histology, surgical details, follow-up and mortality.

Details at initial diagnosis of GTN

On admission to the hospital, each patient underwent a complete clinical history and physical examination, a complete blood count, renal and liver function tests, serum hCG and AFP levels, pelvic and liver ultrasonography, and computed tomography (CT) of abdomen and chest. If the chest CT showed the presence of pulmonary metastases, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or CT brain scans were done. Patients were staged according to the internationally accepted criteria for GTN and were then classified into low-risk or high-risk categories (Seckl et al. 2010).

Treatment protocols

Patients were treated in a uniform manner using the standard well-established treatment protocols. All of the low-risk patients received intramuscular mtx 50 mg (day 1, 3, 5 and 7) and folinic acid 15 mg (day 2, 4, 6 and 8) on alternating days every 2 weeks as primary treatment except one. One patient was treated with mtx again because of inadequate doses in the first-line CTx consisting of mtx (see Table 1, patient no: 10). In the event of mtx resistance, if the hCG reaches a plateau below 100 IU/l, the treatment was switched to single-agent actinomycin D (McNeish et al. 2002). For those whose disease becomes resistant at 100 IU/l, the treatment was changed to combination CTx with EMA/CO (McNeish et al. 2002).

Table 1.

Management and outcome of refractory pts

| Patients no | Histology | WHO risk status | First-line CTx | hCG level after first-line CTx | Second-line CTx | Third-line CTx | Last status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MH | Low | Mtx | 22 | Lost | – | Lost |

| 2 | MH | Low | Mtx | 17 | Act D | – | NED |

| 3 | MH | Low | Mtx | 39 | Act D | – | NED |

| 4 | MH | Low | Mtx | 811 | EMA/CO | – | NED |

| 5 | MH | Low | Mtx | 457 | EMA/CO | – | NED |

| 6 | MH | Low | Mtx | 419 | EMA/CO | – | NED |

| 7 | MH | Low | Mtx | 284 | EMA/CO | – | NED |

| 8 | MH | Low | Mtx | 12,000 | EMA/CO | – | NED |

| 9 | CC | Low | Mtx | 914 | EMA/CO | – | NED |

| 10 | MH | Low | Mtx | 102 | Mtx | – | NED |

| 11 | MH | High | Mtx | 14,685 | EMA/CO | – | NED |

| 12 | CC | High | EMA/CO | 426,000 | BEP | – | Died |

| 13 | CC | High | EMA/CO | 9,430 | BEP | VIP | Died |

| 14 | CC | High | EMA/CO | 2,200 | BEP | VIP | Died |

WHO World Health Organization, hCG human chorionic gonadotropin, CTx chemotherapy, MH mole hydatidiform, CC choriocarcinoma, Mtx methotrexate, EMA/CO methotrexate and actinomycin D alternating with cyclophosphamide and vincristine, Acd D actinomycin D, BEP bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin, VIP etoposide, ifosfamide and cisplatin, NED no evidence of disease

All of patients with high-risk disease were commenced EMA/CO at initial diagnosis. Second-line CTx regimens for refractory high-risk patients were BEP, VIP and mtx every 21 days (Table 2). Complete remission was diagnosed after weekly hCG levels were within normal range (<15 mIU/ml) for three consecutive weeks on chemotherapy. After remission, hCG levels were determined monthly for 12 months, every other month for the next 6 months, every 3 months for the next 12 months and every 6 months thereafter.

Table 2.

The chemotherapy regimens used for patients with gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

| EMA/CO | |

| Week 1 | EMA and CO are alternated at weekly intervals |

| Regimen 1 (EMA) | |

| Day 1 | |

| Etoposide 100 mg/m2 | |

| Actinomycin D 0.5 mg | |

| Methotrexate 300 mg/m2 | |

| Day 2 | |

| Etoposide 100 mg/m2 | |

| Actinomycin D 0.5 mg | |

| Folinic acid rescue 15 mg | |

| Week 2 | |

| Regimen 2 (CO) | |

| Day 1 | |

| Cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 | |

| Vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 (maximum 2 mg) | |

| BEP | |

| Cisplatin 20 mg/m2 days 1–5 | Repeat every 21 days |

| Etoposide 100 mg/m2 days 1–5 | |

| Bleomycin 30 mg days 1, 8 and 15 | |

| VIP | |

| Cisplatin 20 mg/m2 days 1–5 | Repeat every 21 days |

| Etoposide 100 mg/m2 days 1–5 | |

| Ifosfamide 1.5 g/m2 days 1–5 | |

| Mesna 1.5 g/m2 days 1–5 | |

Definition of refractory disease

This group includes low- and high-risk GTN patients whose hCG levels had increased or failed to decrease (plateau) on CTx. Serum hCG levels were assessed once a week during treatment. Since hCG levels can initially increase and/or take 2–4 weeks to fall following the commencement of CTx, patients were given at least 3 weeks of CTx before a diagnosis of refractory GTN could be made.

Refractory disease was defined as follows:

1. Two or more increasing plasma hCG levels despite receiving at least 2 courses of standard CTx.

2. Three or more consecutive hCG values that had failed to fall more than 10% below the preceding hCG level. These patients were considered to have a plateau in their hCG.

3. Increased size of tumor or development of new metastases during CTx.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with placental site trophoblastic tumors (PSTT) were excluded from this analysis because the treatment and outcomes for these patients are different (Schmid et al. 2009).

Statistical analysis

Survival was calculated from the day of diagnosis until death or the date of last follow-up. Variables between groups were compared by X2 test for nominal variables and Mann–Whitney U-test for nonparametric variables, and log-rank tests were used to compare overall survival over time. All analyses were performed using the SPSS 15.0 statistical software package (Chicago, IL, USA), with p < 0.05 considered to be significant.

Results

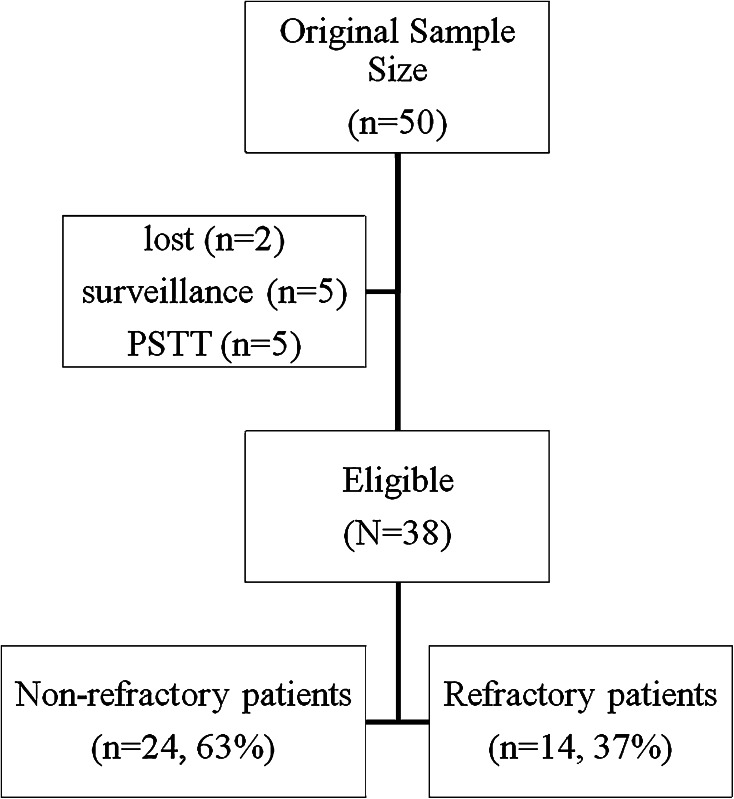

A total of 50 patients were recorded as having CTx for GTN. Twelve patients were excluded in the analyses (Fig. 1). Finally, 24 (63%) out of 38 patients that had non-refractory and 14 (37%) that had refractory disease were analyzed.

Fig. 1.

The diagram of the study

Patients with non-refractory disease (Table 1)

Twenty-four patients had not progressed on first-line CTx. The median age was 32 (19–52), and the median prognostic score was 5.5 (1–11). Fifteen of them had low-risk risk disease, and all of them were treated with mtx; 9 had high-risk disease, and all of them were treated with EMA/CO. The predominant tumor type was mole hydatidiform (62.5%), and the majority of the patients had stage I disease (68%). Antecedent pregnancy in majority of patients was mole, duration between causal pregnancy and initial treatment in majority of patients was less than 4 months, uterine size in majority of patients was greater than 5 cm, and the majority of patients had no metastasis.

Patients with refractory disease (Table 1)

Fourteen patients progressed on CTx and fulfilled the criteria for refractory disease. Four of them had increasing plasma hCG levels, and ten had a plateau in their hCG. The median age was 24 (20–43), and the median prognostic score was 4.5 (2–12). Ten of the refractory patients had low-risk disease, and all of them were treated with mtx, whereas four had high-risk disease, and 3 patients were treated with EMA/CO. One of refractory patients who had high-risk disease was treated with mtx at initial diagnosis because of poor performance status. The predominant tumor type was mole hydatidiform (71%), and the majority of the patients had stage I disease (57%). Antecedent pregnancy in majority of patients was mole, duration between causal pregnancy and initial treatment in majority of patients was less than 4 months, uterine size (by MRI) in majority of patients was 3–5 cm, and majority of patients had no metastasis.

Chemotherapy regimens for patients with refractory disease (Table 3)

Table 3.

Patients characteristics at initial presentation (n = 38)

| Characteristic | Non-refractory pts (n = 24, 63%) |

Refractory pts (n = 14, 37%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median) | 32 ± 8.4 (19–52) | 24 ± 6.9 (20–43) |

| Median prognostic score at diagnosis | 5.5 (range 1–11) | 4.5 (range 2–12) |

| Modified WHO prognostic score | ||

| 0–6 | 15 | 10 |

| ≥7 | 9 | 4 |

| Initial treatment regimens | ||

| Mtx | 15 | 11 |

| EMA/CO | 9 | 3 |

| Histology | ||

| MH | 15 | 10 |

| CC | 9 | 4 |

| Stage | ||

| 1 | 16 | 8 |

| 3 | 8 | 6 |

| Antecedent pregnancy | ||

| Term | 4 | 1 |

| Abortion | 8 | 5 |

| Mole | 12 | 8 |

|

Duration between causal pregnancy and initial treatment (months) | ||

| <4 | 10 | 12 |

| 4–7 | 8 | – |

| 7–13 | 2 | 2 |

| >13 | 4 | – |

| Uterine size (cm) | ||

| 0–3 | 7 | 2 |

| 3–5 | 8 | 7 |

| >5 | 9 | 5 |

| Site of metastasis | ||

| None | 16 | 8 |

| Lung only | 7 | 4 |

| Other sites | 1a | 2b |

| Number of metastasis | ||

| – | 16 | 8 |

| 1–4 | 5 | 3 |

| 5–8 | 2 | 2 |

| >8 | 1 | 1 |

| Surgery | ||

| No | 15 | 14 |

| Yes | 9 | 0 |

pts patients, WHO World Health Organization, Mtx methotrexate, EMA/CO methotrexate and actinomycin D alternating with cyclophosphamide and vincristine, MH mole hydatidiform, CC choriocarcinoma

a Lung and vagina; b Lung and vagina, lung and peritoneal implants

Two of refractory patients who had low-risk disease at initial presentation treated with actinomycin D after diagnosis had refractory disease, six of them were treated with EMA/CO, one of them treated with mtx, and one of them lost during follow-up.

One of the high-risk refractory patients who received mtx in first-line CTx was treated with EMA/CO even though it was high risk. Another high-risk refractory patient that had no evidence of disease was treated with BEP protocol in the second line. Two of four high-risk refractory patients were treated with BEP protocol in the second line and with VIP protocol in the third line. The patients who progressed during third-line CTx regimens died because of disease. Histology of this patient was CC.

Surgery

Nine of 38 (24%) patients underwent surgery (total abdominal hysterectomy ± bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) for GTN. Operation was performed before CTx in all patients. All of the patients treated with surgery were in the non-refractory group, but none of refractory patients underwent surgery (p = 0.014).

Comparison of refractory and non-refractory patients using univariate analysis (Table 4)

Table 4.

Univariate analysis for patients with relapsed disease

| Non-refractory pts (n = 24) |

Refractory pts (n = 14) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 32 | 24 | 0.012 |

| Median hCG at presentation | 3,460 | 14,247 | 0.090 |

| Median hCG half-life | 3.73 | 4.97 | 0.061 |

| Stage | |||

| 1 | 16 | 8 | |

| 3 | 8 | 5 | |

| 4 | – | 1 | 0.560 |

| Median prognostic score at diagnosis | 5.5 | 4.5 | 0.552 |

| WHO risk score | |||

| Low | 15 | 10 | |

| High | 9 | 4 | 0.576 |

| Histology | |||

| MH | 15 | 10 | |

| CC | 9 | 4 | 0.576 |

| Antecedent pregnancy | |||

| Term | 4 | 1 | |

| Abortion | 8 | 5 | |

| Mole | 12 | 8 | 0.701 |

|

Duration between causal pregnancy and initial treatment (months) | |||

| <4 | 10 | 12 | |

| 4–7 | 8 | – | |

| 7–13 | 2 | 2 | |

| >13 | 4 | – | 0.003 |

| Uterine size (cm) | |||

| 0–3 | 7 | 2 | |

| 3–5 | 8 | 7 | |

| >5 | 9 | 5 | 0.483 |

| Site of metastasis | |||

| None | 16 | 8 | |

| Lung only | 7 | 5 | |

| Other sites | 1 | 2 | 0.395 |

| Number of metastasis | |||

| – | 16 | 8 | |

| 1–4 | 5 | 3 | |

| 5–8 | 2 | 2 | |

| >8 | 1 | 1 | 0.902 |

| Initial treatment regimens | |||

| Methotrexate | 15 | 11 | |

| EMA/CO | 9 | 3 | 0.304 |

| Surgery | |||

| No | 15 | 14 | |

| Yes | 9 | 0 | 0.014 |

pts patients, hCG human chorionic gonadotropin, WHO World Health Organization, MH mole hydatidiform, CC choriocarcinoma, EMA/CO methotrexate and actinomycin D alternating with cyclophosphamide and vincristine

Age (p = 0.012), time between causal pregnancy and initial treatment (p = 0.003), and surgery (p = 0.014) displayed a statistically significant difference between non-refractory and refractory patients. There was a nonsignificant trend favor in non-refractory patients with lower hCG levels at initiation of CTx and half-life of hCG (p = 0.09, p = 0.061, respectively). Other than these findings, there was no statistically significant difference between groups.

Follow-up and survival

Median follow-up time was 53 months (range 1–173). All of the non-refractory patients followed with no evidence of disease, whereas 11 of the refractory patients (78.6%) followed with no evidence of disease (p = 0.015).

Discussion

The refractory rate following CTx is high, and the majority of these patients can be cured with further treatment (77%). However, patients with disease refractory to high-risk treatment have a significantly less favorable outcome. Three of 4 patients with high-risk treatment died because of disease. Histology all of dead patients had CC. Age, time between causal pregnancy and initial treatment and surgery was found to be statistically significant predicting factor in univariate analysis. There was a nonsignificant trend for hCG level at initiation of CTx and hCG half-life favor for non-refractory patients. Interestingly, none of patients who obtained a complete serological remission with CTx relapsed during follow-up. Therefore, obtaining a complete serological remission with CTx is crucial for these patients.

The primary refractory rate to primary CTx of patients with low- and high-risk GTN was variable between 30–35.6% and 17–18.2% in the literature, respectively (McNeish et al. 2002; Bower et al. 1997; Growdon et al. 2010; Turan et al. 2006; Garrett et al. 2002). In the present study, the refractory rate of low- and high-risk patients was 40 and 31%, respectively. When the refractory rate of low-, intermediate- and high-risk GTD patients was considered separately, the rate of low-, intermediate- and high-risk patients was 41.2, 37.5 and 30.8%, respectively (data not shown). These discordant results may be due to the small sample size and the heterogeneous patient populations. Another major limitation of most of these studies (including the present) is their retrospective nature.

Owing to the lack of published data, there is no specific scoring/prognostic system for refractory patients. The WHO and FIGO scoring systems do include prognostic scores (points) for previous treatment (up to six points), the scoring systems were not widely evaluated or validated for these rare patients. Although numbers are small, the data presented here do show that most of the common used factors for women in high- and low-risk disease at initial presentation can predict refractory to primary CTx. A study shows that FIGO prognostic scores were not significantly different between the treatment success group and the failure group in univariate analysis (Feng et al. 2009). Kim et al. (1998a) presented a study for evaluated risk factors for the prediction of treatment failure in GTNs treated with EMA/CO regimen. Tumor age, number of metastatic organs, metastatic site and previously inadequate CTx were found to be independent statistical significant prognostic factors for treatment failure in this study. In addition, Kim et al. says that patients with scores of less than 12 can be treated favorably with EMA/CO, whereas in patients with scores of 12 or more, this treatment was unfavorable. However, this study showed that 41.8% of heterogeneous patient populations had inadequate previous CTx.

Salvage CTx with drug regimens employing etoposide and a platinum agent with or without bleomycin or ifosfamide, often combined with surgical resection of sites of persistent tumor, will result in cure for some of patients with resistant GTN. Various regimens have been reported, often in a small series, with a response rate ranging from 30 to 93% (Feng et al. 2009). Our study demonstrated that all of the low-risk patients survived during follow-up even when some of these patients were treated with salvage CTx. Lurain et al. show that of the 26 patients with persistent/resistant GTN who received platinum-based salvage CTx, 73% (n = 19) had a complete response and 61.5% (n = 16) survived (Lurain and Nejad 2005). Another conclusion of our study was based on the effect of histology on disease course.

Surgical procedures often play an important role in the management of GTN. Approximately one half of patients with high-risk GTN will require one surgical procedure. Adjuvant surgical procedures, especially hysterectomy and pulmonary resection, are used most frequently to remove foci of CTx-resistant disease in patients with persistent or recurrent (Lurain et al. 2006). We demonstrated that surgery is one of the important variables for chemoresistance. All patients treated with surgery had no resistance to CTx. This result may explain why non-refractory patients are older than refractory patients. Median age was statistically different between the patients treated with/without surgery (39 vs. 27, p = 0.006) (data not shown). These results might lead to the desire to maintain fertility in refractory patients.

The Sheffield group recently updated their data on the role of hysterectomy in managing persistent GTN at their institution (Alazzam et al. 2008). Of 8,860 registered patients, 62 (0.7%) underwent hysterectomy for GTN and 22 (35.5%) for resistance to CTx and 21 (33.9%) for major hemorrhage, while the remainder had hysterectomy as part of their primary treatment for other indications. The overall remission rate in these patients was 93.5%; however, 7 relapsed and 4 (18%) of 22 patients with resistant disease subsequently died. Another study was performed by Doumplis et al. to evaluate the role of hysterectomy in the management of 25 patients with GTN, and they found that the two main reasons for surgery were chemoresistance during initial treatment and the relapse after treatment (Doumplis et al. 2007). Survival was found 88% (22/25) in this study.

In conclusion, despite the success achieved in the treatment of GTN, there is still a challenge in the management of chemoresistant patients. The outcome of patients who are refractory to high-risk treatment regimen is less favorable than low-risk regimens. Surgery is one of the modalities that should be considered in the management of GTN.

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- Alazzam M, Hancock BW, Tidy J (2008) Role of hysterectomy in managing persistent gestational trophoblastic disease. J Reprod Med 53:519–524 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alazzam M, Young T, Coleman R et al (2011) Predicting gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN): is urine hCG the answer? Gynecol Oncol 122:595–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower M, Newlands ES, Holden L et al (1997) EMA/CO for high-risk gestational trophoblastic tumors: results from a cohort of 272 patients. J Clin Oncol 15:2636–2643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan A, Dave K, Desai A, Mankad M, Patel S, Dave P (2010) High-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia at Gujarat Cancer and Research Institute: thirteen years of experience. J Reprod Med 55:333–340 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumplis D, Al-Khatib K, Sieunarine K et al (2007) A review of the management by hysterectomy of 25 cases of gestational trophoblastic tumours from March 1993 to January 2006. BJOG 114:1168–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiriksson L, Wells T, Steed H et al (2012) Combined methotrexate-dactinomycin: an effective therapy for low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol 124:553–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng F, Xiang Y, Li L, Wan X, Yang X (2009) Clinical parameters predicting therapeutic response to surgical management in patients with chemotherapy-resistant gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol 113:312–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng F, Xiang Y, Wan X, Zhou Y (2010) Prognosis of patients with relapsed and chemoresistant gestational trophoblastic neoplasia transferred to the Peking Union Medical College Hospital. BJOG 117:47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett AP, Garner EO, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS (2002) Methotrexate infusion and folinic acid as primary therapy for nonmetastatic and low-risk metastatic gestational trophoblastic tumors. 15 years of experience. J Reprod Med 47:355–362 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Growdon WB, Wolfberg AJ, Goldstein DP et al (2010) Low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia and methotrexate resistance: predictors of response to treatment with actinomycin D and need for combination chemotherapy. J Reprod Med 55:279–284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harma M, Yurtseven S, Gungen N (2005) Gestational trophoblastic disease in Sanliurfa, southeast Anatolia, Turkey. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 26:306–308 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra AV, Lurain JR, Rademaker AW, Schink JC (2008) Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: treatment outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 112:251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Bae SN, Kim JH, Kim CJ, Jung JK (1998a) Risk factors for the prediction of treatment failure in gestational trophoblastic tumors treated with EMA/CO regimen. Gynecol Oncol 71:247–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Bae SN, Kim JH et al (1998b) Effects of multiagent chemotherapy and independent risk factors in the treatment of high-risk GTT–25 years experiences of KRI-TRD. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 60(Suppl 1):S85–S96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurain JR (2010) Gestational trophoblastic disease I: epidemiology, pathology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of gestational trophoblastic disease, and management of hydatidiform mole. Am J Obstet Gynecol 203:531–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurain JR, Nejad B (2005) Secondary chemotherapy for high-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol 97:618–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurain JR, Singh DK, Schink JC (2006) Role of surgery in the management of high-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. J Reprod Med 51:773–776 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurain JR, Singh DK, Schink JC (2010) Management of metastatic high-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: FIGO stages II-IV: risk factor score > or = 7. J Reprod Med 55:199–207 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lybol C, Thomas CM, Bulten J, van Dijck JA, Sweep FC, Massuger LF (2011) Increase in the incidence of gestational trophoblastic disease in The Netherlands. Gynecol Oncol 121:334–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeish IA, Strickland S, Holden L et al (2002) Low-risk persistent gestational trophoblastic disease: outcome after initial treatment with low-dose methotrexate and folinic acid from 1992 to 2000. J Clin Oncol 20:1838–1844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne RJ, Filiaci V, Schink JC et al (2011) Phase III trial of weekly methotrexate or pulsed dactinomycin for low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 29:825–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid P, Nagai Y, Agarwal R et al (2009) Prognostic markers and long-term outcome of placental-site trophoblastic tumours: a retrospective observational study. Lancet 374:48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seckl MJ, Sebire NJ, Berkowitz RS (2010) Gestational trophoblastic disease. Lancet 376:717–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares PD, Maesta I, Costa OL, Charry RC, Dias A, Rudge MV (2010) Geographical distribution and demographic characteristics of gestational trophoblastic disease. J Reprod Med 55:305–310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse KY, Chan KK, Tam KF, Ngan HY (2008) Gestational trophoblastic disease. Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med 19:89–97 [Google Scholar]

- Turan T, Karacay O, Tulunay G et al (2006) Results with EMA/CO (etoposide, methotrexate, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide, vincristine) chemotherapy in gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Cancer 16:1432–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Short D, Sebire NJ et al (2008) Salvage chemotherapy of relapsed or high-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) with paclitaxel/cisplatin alternating with paclitaxel/etoposide (TP/TE). Ann Oncol 19:1578–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]