Abstract

Purpose:

With surgery being the only potential cure for pancreatic cancer, high-risk premalignant pancreatic lesions often go unnoticed by palpation or white light visualization, leading to recurrence. We asked whether near-infrared fluorescence imaging of tumor-associated inflammation could identify high-risk premalignant lesions, leveraging the tumor microenvironment (TME) as a sentinel of local disease and, thus, enhance surgery outcomes.

Experimental Design:

Fluorescence-guided surgery was performed on genetically engineered mice (Ptf1a-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+; Smad4flox/flox [KSC]) at discrete stages of disease progression, histologically confirmed high-risk, premalignant lesions in postnatal mice to locally advanced pancreatic tumors in adults, using the imaging agent V-1520, a translocator protein (TSPO) ligand. Age-matched wild-type littermates were used as controls, while Ptf1a-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+ (KC) mice modeled pancreatitis and precursors of low penetrance. Localization of V-1520 and tumor-associated macrophages amongst the TME was detected by immunofluorescence imaging.

Results:

V-1520 exhibited robust accumulation in the pancreata of KSC mice from the early postnatal stage. Increased accumulation was observed in the pancreata of adolescent- and adult-aged mice with greater ductal lesion and stromal burden. Confocal microscopy of ex vivo pancreas specimens co-localized V-1520 accumulation primarily with CD68-expressing macrophage in KSC mice. Unlike the pancreata of KSC mice, accumulation of V-1520 did not exceed background levels in the pancreata of KC mice with pancreatitis.

Conclusion:

V-1520 exhibited differential accumulation in pancreatic cancer-associated inflammation compared to pancreatitis. Given the robust tracer uptake in tissues associated with early yet high-risk lesions, we envision V-1520 could enhance surgical resection and reduce the potential for recurrence from residual disease.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, with a 5-year survival rate of 12.8% (1), and is projected to become the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States by 2030 (2). Owing to its aggressive nature, standard of care continues to involve surgical resection of the localized tumor, which has improved 5-year survival rates to 18–24% (3). However, even with timely surgery, clinical trials and large-cohort retrospective studies demonstrated recurrence rates of up to 80% (4), which can be attributed to incomplete resection. Accurately identifying small, high risk pre-malignant lesions during surgical resection could significantly decrease the likelihood of tumor recurrence (5) and enhance survival (6). Despite the presence of enhanced desmoplastic activity, many premalignant lesions are small and challenging to detect by white light illumination or by palpation; thus, new techniques are required to identify and eliminate lesions likely to form the basis of future recurrence. Fluorescence-guided surgery (FGS) has emerged as a promising imaging approach, improving the surgeon’s ability to clearly distinguish malignant tissue from healthy tissues during surgery, thus promoting complete removal of small lesions not visible with conventional white light (7,8). The FDA approval of imaging agents such as 5-aminolevulinic acid HCl (in 2017 [glioma]), hexaminolevulinate HCl (in 2010 [bladder cancer]), pafolacianine (in 2021 [ovarian cancer] and 2022 [lung cancer]), and pegulicianine (in 2024 [breast cancer]), has been a catalyst for FGS-related research and clinical advancement in various fields including oncology and beyond (9). However, no promising FGS agents are currently available for pancreatic premalignant lesions.

The tumor microenvironment (TME), which includes the cancer cells along with the stroma surrounding the tumor, provides structural support for the tumor and facilitates interaction between cancer cells and stromal components, promoting tumor growth, invasion, and therapy resistance (10–12). Desmoplastic activity is initiated early in the progression of pancreatic cancer and often results in extensive tumor stroma, which can account for up to 90% of the total tumor volume (13) Within the pancreatic TME, chemokines, cytokines, and growth factors secreted from cancer cells and associated fibroblasts promote infiltration of monocytes and their differentiation into tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) (14,15). Because TAMs occupy a significant niche in tumor margins, we hypothesized that these cells could serve as imaging sentinels for even small populations of transformed cells that are likely to progress and should be considered for removal at surgery.

Previously, we reported translocator protein (TSPO) as a potential biomarker of pancreatic cancer and the subsequent development of V-1520, a near-infrared fluorescence tracer targeting TSPO aimed at FGS (16). In the prior study, we found that V-1520 accumulated in tumors of adult Ptf1a-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+; Smad4flox/flox (KSC) mice, rendering these lesions suitable for FGS (16). The present study was motivated by the observation of early recruitment of TAMs to developing lesions. We hypothesized that V-1520 accumulation in sentinel inflammation especially in early lesions could support future improved surgical resection. To this end, we used V-1520 to image KSC mice, which develop pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) through all major stages of disease as a function of age; importantly, early postnatal, adolescent, and adult mice were imaged to follow tracer accumulation as a function of age and longitudinal progression in comparison to age-matched littermates. Furthermore, we compared V-1520 accumulation in KSC mice and Ptf1a-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+ (KC) mice to determine whether gross V-1520 accumulation was restricted to TAMs in the high-risk, high tumor penetrance setting, and could thus discriminate tumor-associated inflammation from pancreatitis. Discriminating TAMs from pancreatitis could allow physicians to expand suspicious surgical fields accordingly.

Materials and Methods

Chemistry.

V-1520 was prepared as described previously (16). The crude obtained was purified via high-performance liquid chromatography using a C18 column with 50/50 (acetonitrile/water) as the mobile phase.

Molecular docking.

The crystal structure of Bacillus cereus TSPO (BcTSPO, PDB ID: 4RYI) was used as a target for molecular docking of ligand V-1520, which was performed on the Maestro platform (version 13.8; Schrödinger; RRID:SCR_014879) using the default standard precision docking method. A grid box for docking was generated using the maximum size (diameter midpoint box: 40 Å, dock ligands with length 36 Å). Constrained docking with the pyrazolopyrimidine unit of V-1520 (based on the structure of 5b in ref. (17)), in TSPO was performed first followed by addition of the alkyl linker and infrared dye moiety (Fig. 1A and 1B). Among the maximum 20 docking poses, the docking score of the top pose shown was −14.384 kcal/mol.

Figure 1.

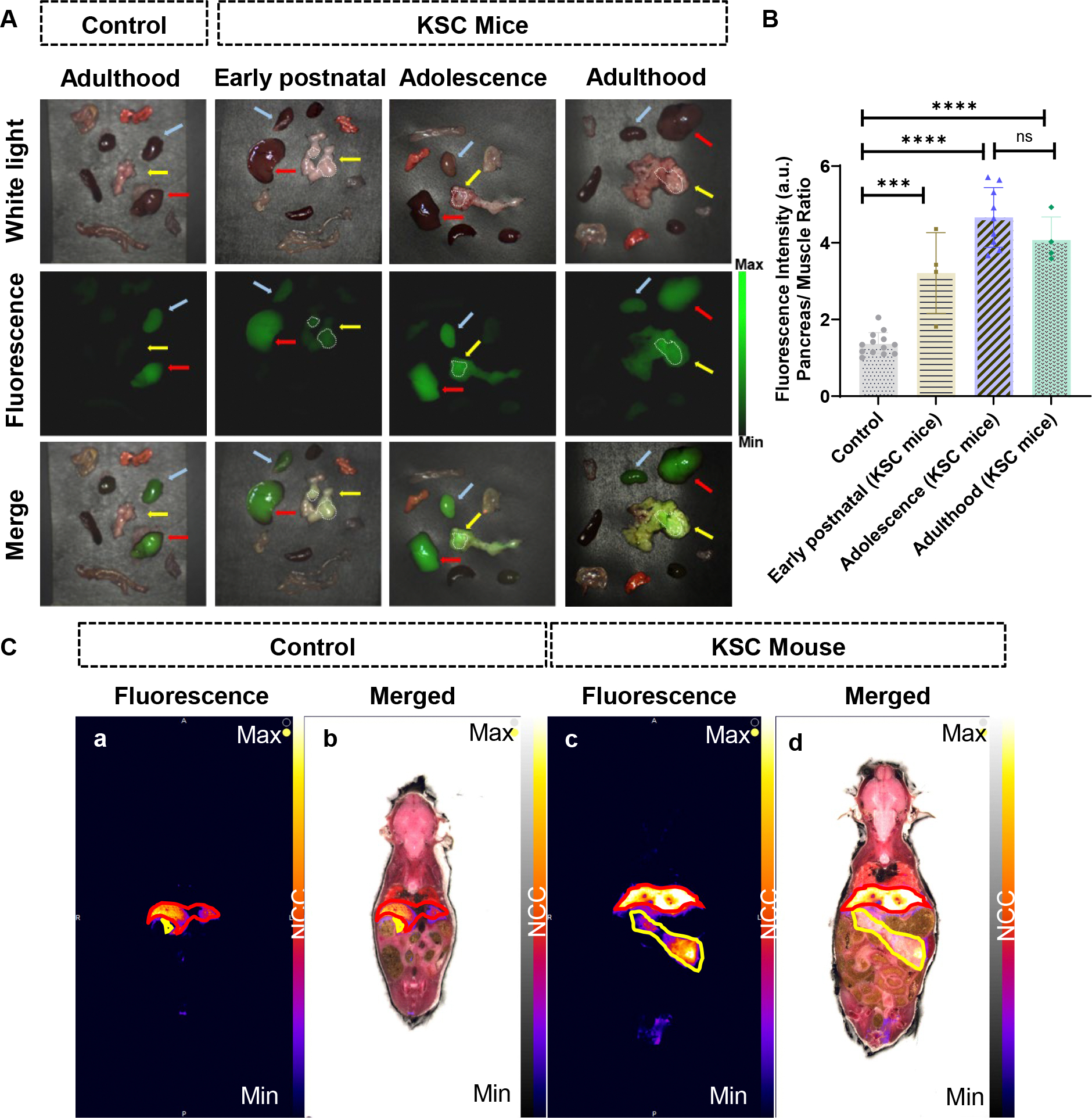

Chemical structure, TSPO docking, and in vivo real-time intraoperative FGS using V-1520 in mice with pancreatic cancer at different disease stages. A, Chemical structure of V-1520 illustrating the targeting ligand, linker, and fluorophore (IRDye 800CW). B, Lowest-energy docking of V-1520 to TSPO protein. C, Representative real-time images of an adult control mouse and KSC mice at different stages of development (early postnatal, adolescence, and adulthood) captured during FGS. Mice were intravenously injected with 20 nmol V-1520, 24 hours prior to surgery. The pancreata are outlined in red for enhanced visualization.

Molecular dynamics simulations.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of protein-ligand interactions was performed using the Desmond module implemented with the Maestro interface (Schrödinger release 2023‐4; RRID:SCR_014879). The top pose of the TSPO ligand V-1520 docking complex achieved with the standard precision method was used for the MD simulation procedure. The complex was solvated with the default simple point charge (SPC) model and placed in the center of an orthorhombic box using appropriate size. A sufficient number of counter-ions and a 0.15 M solution of NaCl were used to neutralize the simulation system. The OPLS4 force field was selected. Regarding MD simulation settings, the total simulation time was 1000 ns, the recording interval was 100 ps per trajectory, and the energy was 10 kcal/mol. In total, 10,000 frames were stored after the simulation. The temperature of the simulation system was set at 300 K, and the pressure was set at 1.01325 bar. MD simulations were performed using the default NpT ensemble. The dynamic behavior of the simulation system was analyzed by calculating the root mean square deviation (RMSD).

Genetically engineered mouse models.

All animal procedures followed institutional, state, and federal regulations and were approved by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee prior to implementation. GEM models with mutations relevant to human pancreatic cancer models were bred. All mice were maintained in filter-topped cages on autoclaved food and water at MD Anderson Cancer Center animal facility and were used in accordance with AALAS and NIH guidelines and regulations. KSC and KC mice were used to induce tumor growth and pancreatitis, respectively. The stop codon between two loxP sites excised using Cre-Lox recombination to activate the Kras mutation (KrasG12D) were used. The Cre-loxP system is driven by the endogenous pancreas-specific locus Ptf1a (pancreatic transcription factor-1a), which plays an essential role in human pancreatic development and differentiation. Ptf1a-Cre and Ptf1a-Cre; Smad4fl/fl mice were mated with LSL-KrasG12D/+ mice to obtain the KC and KSC mice, respectively (18,19). The KSC mice with loss of Smad4 gene and KrasG12D/+mutation was compared to control mice (Smad4fl/fl) with intact Smad4 and wild-type Kras gene. Genotyping of the mice was performed using polymerase chain reaction at 3 weeks of age to identify the tumor-bearing mice and control mice needed for the experiments. Control and KSC mice of both sexes aged 4–12 weeks were used for the studies, whereas KC mice of both sexes aged 15–23 weeks were used.

In vivo imaging with FGS.

In vivo imaging of the study mice was carried out using a Curadel RP-1 OSN system. This system is combined with FLARE® imaging systems to enable fluorescent imaging during surgery. The FGS was visualized in real time using a merge of both white light and fluorescence imaging with an 800 nm wavelength filter. Control, KSC, and KC mice were injected via the tail vein with 100 μL of 0.2 mM (1.5 mg/kg) V-1520 solution in PBS, 24 hours prior to imaging. Each animal was anesthetized using isoflurane and positioned for imaging. Next, an incision was made to expose the abdominal cavity and the pancreas. Images of abdominal cavity and the pancreas were acquired using white light, fluorescence light with an 800 nm wavelength and the merged of white and fluorescent light. Following FGS and in vivo imaging, the animals were euthanized via cervical dislocation, and their pancreata and other major organs were collected for ex vivo imaging.

Ex vivo imaging.

After the in vivo imaging described above, excised murine pancreata and other major organs were imaged using the Curadel RP-1 OSN system. Quantification of pancreata was done by manually selecting the region of interest on pancreas and other major organs and graphs of fluorescence intensity were constructed using Graph Prism (version 10.3; GraphPad Software; RRID:SCR_002798). The tissue sections were imaged using Odyssey Imaging Systems (LI-COR Biosciences) using the 800 nm filter.

Tissue processing and histological examination of pancreatic tissue.

After whole pancreata were excised from the KSC and control mice, pancreatic tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Following fixation, the tissue samples were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin blocks. The blocks were sliced at a thickness of 5 μm, and the slices were deparaffinized for staining. Standard staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and a trichrome staining kit (cat. #Ab150686; Abcam) was performed to examine morphological changes, tumor progression, and fibrosis. The staining was carried out according to the staining kit manufacturer’s recommendations. Images were digitally scanned using Aperio AT2 Microscope (Leica). Tissue samples were reviewed by an expert pathologist (S.J.-H. Lin). Quantification of acinar cells, ductal lesions, and stromal areas in the pancreatic tissue of KSC mice was done on trichrome-stained whole slide images using a random forest-based machine learning algorithm from HALO image analysis platform version 3.6.4134 (Indica Labs, Inc). We employed machine learning techniques to quantitatively assess color intensity in fluorescence images of the TSPO, using a Python-based analysis pipeline.

Immunofluorescent and immunohistochemical staining.

Paraffin-embedded tumor sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Sections were then incubated with TSPO recombinant rabbit monoclonal antibody (Clone: 4H2, cat#MA5–24844, Invitrogen; RRID:AB_2717282), and rat recombinant monoclonal CD68 antibody (CloneFA-11, cat. # ab53444, Abcam; RRID:AB_869007) at 4°C overnight. After rinse with phosphate-buffered saline, sections were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor Plus 488 (cat. #A32731; Invitrogen; RRID:AB_2633280) and goat anti-rat IgG (H+L) cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 633 (cat. #A-21094, Invitrogen; RRID:AB_141553). Sections were then mounted using ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant with DNA Stain DAPI (cat. #P3693, Invitrogen) to stain the nuclei. To image the pancreatic tissue sections, they were excited at 730 nm to induce NIR emission in the range of 780–810 nm. The NIR emission had a pseudocolor of red. Co-localization of TSPO and V-1520 was observed as yellow on merging green and red color. Immunofluorescent images were captured using an FV3000 confocal microscope (Olympus). To perform immunohistochemical staining for analyzing CD68, CD80 and CD163 expression KC/KSC mice, paraffin-embedded tumor sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Sections were then incubated with rabbit polyclonal CD68 antibody (Clone: FA-11, cat#. ab125212, Abcam, RRID: AB_10975465), CD80/B7–1 monoclonal antibody (cat. #66406–1-Ig, Proteintech, RRID:AB_2827408) and CD163 polyclonal antibody (cat. #16646–1-AP, Proteintech, RRID:AB_2756528) at 4°C overnight. After rinse with phosphate-buffered saline, sections were incubated with Ready-to-Use (R.T.U.) biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (cat. #BP-9100–50, Vector Laboratories, RRID:AB_3665891) for 30 min at room temperature. After wash with phosphate-buffered saline, sections were incubated with R.T.U. VECTASTAIN® Elite® ABC-HRP Reagent, Peroxidase, (cat. #PK-7100, Vector Laboratories, RRID:AB_2336827). For CD80 monoclonal antibody immunohistochemical staining, M.O.M.® (Mouse on Mouse) ImmPRESS® HRP Polymer Kit (cat. #MP-2400, Vector Laboratories) was used as per manufacture’s protocol. Finally, the sections were visualized with the DAB substrate under an optical microscope. Images were scanned using KEYENCE BZ-X810 All-in-One Fluorescence Microscope and BZ-X800 software.

Cryo-fluorescence tomography.

Control and KSC mice were intravenously injected with V-1520 and euthanized 24 hours later. Euthanized mice were then frozen using a hexane/dry ice mixture and embedded in optimal cutting temperature blocks. The blocks were mounted on a stage and maintained at temperature below −80°C during the tomography process. Cryo-tomography and imaging of the blocks were performed using the Xerra platform (EMIT Imaging). The blocks were then sliced into 20 μM sections, and images of whole mouse body were obtained using an auto adjusted camera. For each sliced section, white-light and fluorescent images with laser excitation at 780 nm and emission at 835 nm were acquired. Images were processed and analyzed using VivoQuant software.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using Graph Prism software (version 10.3; GraphPad Software; RRID:SCR_002798) and include unpaired t-test and one-way analysis of variance. Details of the statistical tests performed, including P-values, are reported in the figure legends. The numbers of replicates are represented by dots in quantification graphs. The asterisks in the figures indicate significance. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant in all experiments.

Data Availability.

All data supporting the findings of this study are included in the article and its supplementary materials or are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

TSPO ligand V-1520 accumulates in the pancreas of early postnatal, adolescent, and adult KSC as imaged by intraoperative FGS.

A derivative of the 1,3 diethylpyrazolopyrimidine TSPO ligand V-1008 (17,20–22), V-1520 tethers the ligand to an FDA-approved NIR dye (23) through an eight-carbon linker and exhibits nanomolar affinity (16) (Fig. 1A). In the present study, we docked V-1520 to the TSPO protein in silico in a constrained manner, observing that the pyrazolopyrimidine targeting unit resided deep within the binding lobby, whereas the nonbinding fluorescent moiety was peripheral to the binding lobby (Fig. 1B). We further investigated the molecular interactions between V-1520 and TSPO, performing classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. We found that the docked complex was stable over a long simulation time (1000 ns) with low root mean square deviation values (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Movie S1). To evaluate V-1520 accumulation as a function of age and tumor development, KSC mice and age-matched littermate controls 4–12 weeks of age were randomized into three cohorts as follows: early postnatal (4–5 weeks), adolescence (6–10 weeks), and adulthood (11–12 weeks) (Supplementary Fig. S2) (24). For FGS, V-1520 was administered 24 h prior to imaging, as described in the methods section. Real-time images of pancreata under white light and fluorescent light during surgery were collected using a Curadel RP-1 OSN system. At all development stages, KSC mice qualitatively exhibited robust fluorescent signal over background emanating from the pancreata, whereas age-matched controls exhibited little to no signal at the same exposure settings (Fig. 1C).

In vivo biodistribution of V-1520 in KSC mice.

To evaluate the overall biodistribution of V-1520 during FGS, mice were sacrificed and major organs collected for ex vivo NIR fluorescence imaging (Fig. 2A). As expected, liver and kidney were the major normal organs that exhibited retention of V-1520, with other healthy organs exhibiting very little fluorescence. The pancreata of KSC mice exhibited marked fluorescence, with elevated, focal accumulation in the pancreas of early postnatal and adolescent mice that correlated with developing lesions. In adult mice, the accumulation was elevated, but given the advanced nature of disease, pancreata were widely fluorescent throughout. In contrast, control mice did not exhibit V-1520 uptake in the pancreas (Fig. 2A). When the pancreatic fluorescence following V-1520 uptake was quantified, we found that the pancreata of control mice did not exceed a tumor: muscle ratio of 1.3, while V-1520 uptake in early postnatal, adolescent, and adult mice was 2.3, 3.4 and 2.7, respectively and followed progression-related TSPO expression profiles as previously reported (Fig. 2B) (16).

Figure 2.

Ex vivo imaging performed to validate localization of V-1520 in pancreatic lesions in KSC mice. A, Representative NIR images of the pancreata and major organs excised from control (first column) and KSC (second-fourth columns) mice, captured 24 hours after V-1520 injection and following FGS. The images were captured using white light (first row), fluorescent light (second row), and merged of white light and fluorescent light (third row). The liver, kidneys, and pancreas are indicated with red, blue, and yellow arrows, respectively. The white encircled regions highlight the pancreatic lesions with maximum V-1520 uptake. B, Uptake of V-1520 in the pancreas quantified and expressed as the pancreas/muscle ratio in control and KSC mice at different development stages. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance. ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, ns= not significant. C, CFT images of the control and KSC mice at 4 and 8 weeks of age, respectively, 24 hours after injection of V-1520. (a) Fluorescent (λex780/λem835) image of a control mouse, (b) fluorescent and white light merged image of the control mouse, (c) fluorescent (λex780/λem835) image of a KSC mouse, (d) and fluorescent and white light merged image of the KSC mouse are shown.

We performed CFT to analyze the whole-body spatial distribution of V-1520 in control and KSC mice (Fig. 2C). CFT facilitates high-resolution 3D mapping of the spatial distribution of fluorescent probes within the tissue environment. The coronal view of whole body under 780 nm excitation demonstrates significant uptake of V-1520 in the pancreas of a KSC mouse (encircled) but no uptake in the pancreas of a control mouse was observed (Fig. 2C). In addition, the accumulation of V-1520 in liver and kidneys of both KSC and control mice were found to be in agreement with the in vivo biodistribution data (Supplementary Movie S2). Similar to ex vivo imaging, CFT of KSC pancreas revealed higher uptake of V-1520 in areas that appeared to be more advanced.

Histological examination of the pancreas in KSC mice demonstrated premalignant lesions at the early postnatal stage.

Expression of mutant KrasG12D and loss of Smad4 result in accelerated, persistent differentiation of acinar-to-ductal metaplasia. This leads to the development of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), which eventually leads to the development PDAC over time (18). PanIN and IPMNs are premalignant lesions with a high risk of transforming to cancer (25). KSC mice are known to have extensive PanIN and IPMNs by the time they reach 8 weeks in age (18). To evaluate the morphology of pancreatic tissue in KSC mice, we harvested the pancreata from KSC and control mice after FGS and performed H&E and trichrome staining to examine their tissue morphology and collagen fibers (Fig. 3A). The H&E staining of the control mice demonstrated well-defined pancreatic tissue structures composed of exocrine acinar cells, ducts, along with islets of Langerhans. In contrast, we observed dysregulated tissue morphology in the pancreata of the KSC mice with glandular epithelial proliferation of the pancreatic ducts surrounded by a dense stroma. Furthermore, the pancreata of early postnatal KSC mice showed lesions of mouse PanIN (mPanIN) and cystic papillary neoplasms with apical mucins in the lumen, resembling human PanIN and IPMNs, respectively (Fig. 3A). PanIN and IPMNs are considered premalignant lesions until they are in their early grade of progression with minimal cytological and architectural atypia (26,27). Adolescence stage KSC mice exhibit more aggressive disease morphology than early postnatal KSC mice, with few acinar cells, more mPanIN lesions, cystic papillary neoplasms, and invasive adenocarcinomas, while increased tumor cell proliferation with invasive PDAC is observed in adult KSC. Histopathologic grading of pancreatic lesions in KSC mice is shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 3.

Histopathological examination demonstrating pancreatic tumor progression in KSC mice. A, Representative H&E-stained digital images of whole pancreas tissue sections from control mice (adulthood stage) and KSC mice (early postnatal, adolescence, and adulthood stages). Regular acinar cells and pancreatic ducts were observed in the pancreata of control mice, whereas KSC mice exhibited ductal dysplasia in the early postnatal stage, advanced lesions resembling PanIN and IPMNs in the adolescence stage, and malignancy surrounded by a dense stroma with PDAC in the adulthood stage. The trichrome-stained images (magnification, 20x) highlight higher collagen levels in the KSC mice than in the control mice, which increased with age. The TSPO immunofluorescence images (magnification, 20x) show elevated TSPO expression in stroma. Scale bar (second, third and fourth rows), 200 μm. B-D, Area quantification of ductal lesions (B), stroma (C), and acinar cells (D) in pancreatic tissue in KSC mice as shown on trichrome-stained whole slide images using HALO software. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; ns= not significant (Student t-test).

To study the desmoplastic activity in the pancreatic tissue of KSC mice, we performed trichrome staining (Fig. 3A). We found that progression of desmoplasia was correlated with advancement of pancreatic cancer in KSC mice. In contrast, we observed only fibrous stroma and collagen deposition around pancreatic ducts and blood vessels of control mice. In early postnatal KSC mice, we noted fibrous stroma and collagen deposition around pancreatic lesions that became more pronounced and excessive in adolescence, concentrating around large pancreatic lesions, and even more pronounced in adults.

To further investigate TSPO expression across different stages in KSC mice, we performed TSPO immunofluorescence staining of tissue sections collected from KSC mice at all development ages (Fig. 3A). We observed elevated TSPO expression in the stroma surrounding the tumor lesions, and quantitative analysis confirmed a statistically significant increase in both adulthood and adolescence stage mice compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. S3). Furthermore, disease progression in mice was associated with enhanced TSPO expression in the stroma, while control mice exhibited little to no TSPO expression. To confirm the localization of V-1520 within tumor region, consecutive pancreatic tissue sections from KSC mice were imaged using the Odyssey Imaging System with 800 nm filter. The resulting fluorescence signal was compared to corresponding H&E and trichrome-stained sections. The comparison revealed specific accumulation of V-1520 in tumor area, with no detectable signal in tumor-free regions, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S4.

Furthermore, we quantified ductal lesions and acinar and stromal cells in trichrome-stained sections of the pancreas in KSC mice. We observed a noteworthy change in these cell types as a function of age. Specifically, we observed significant increases in the number of ductal lesions and stromal cells and decreases in the number of acinar cells with age and tumor progression (Fig. 3B–D).

V-1520 co-localized with TSPO-expressing TAMs in the stroma of KSC mice.

PDAC is often characterized by immune cell infiltration, and TAMs are the predominant immune cells in tumor stroma (28). TSPO expression is reported to be significantly elevated in TAMs, indicating its role as a marker for TAMs in the TME (29–31). Therefore, we co-stained pancreatic tissues with V-1520 and anti-TSPO and anti-CD68 antibodies as we aim to identify the specific localization of V-1520 within the tumor stroma (Fig. 4). The immunofluorescent images show co-localization of V-1520 with CD68-positive and TSPO-positive cells in stroma of pancreatic tissue, indicating uptake of V-1520 in TSPO-expressing macrophages. Fluorescence quantification of V-1520, TSPO, and CD68-stained tissues revealed no statistically significant differences in fluorescence signal intensity among the markers (Supplementary Fig. S5). These findings suggest that the specificity of V-1520 toward TSPO-expressing TAMs in the tumor stroma can be exploited to mark clear tumor boundaries for pancreatic lesions in FGS.

Figure 4.

TSPO-expressing CD68-positive TAMs readily take up V-1520 in tumor stroma. Immunofluorescent staining of pancreatic tissues sections excised from KSC mice following surgery, showing co-localization of V-1520 with TSPO- and CD68-expressing cells. Images 1 and 2 are taken from adulthood stage mice. White arrows in Image 1 indicate co-localization of V-1520 with TSPO- and CD68-expressing cells. Image 3 is the zoomed view of Image 2. Scale bar, 200 μm.

V-1520 accumulation differentiates tumor-associated inflammation from pancreatitis.

In our studies, KSC mice exhibited 100% tumor penetrance and survival of 14–18 weeks. In contrast, KC mice develop pancreatitis, with low-grade PanINs that rarely progress to pancreatic cancer and have a typical survival greater than a year (32–34). To determine if the V-1520 accumulation profile could discriminate tumor -associated inflammation from benign pancreatitis, we compared the KSC mice to KC mice. As expected, V-1520 accumulation in the pancreata of KSC mice was found to exhibit a tumor: muscle ratio of approximately 4:1, while the accumulation in KC mice did not exceed background (Fig. 5A and 5B). A similar distribution among groups was observed whether ratiometric (lesion/muscle; Fig. 5B) or raw fluorescence intensity (Supplementary Fig. S6) was utilized. To determine macrophage influx into the stroma of KC, KSC (adulthood an adolescence stage) and control mice, we performed immunohistochemical analysis of pancreatic tissues using an anti-CD68 antibody, a marker for pan-macrophages. Quantification of CD68 positivity in the stroma demonstrated a higher level of infiltration of macrophages into the tumor stroma in KC mice and KSC mice than in control mice. (Fig. 5C and 5D). To evaluate macrophage polarization, immunohistochemical staining was conducted using CD80 (a pro-inflammatory, M1 macrophage marker) and CD163 (an anti-inflammatory, M2 macrophages marker). Notably, KSC mice exhibited elevated infiltration of M2 macrophages in stroma, whereas in contrast, KC mice showed elevated level of M1 macrophages (Supplementary Fig. S7), suggesting distinct immune microenvironment between both mice models. Interestingly, these results also suggest that V-1520 accumulation is associated with pro-tumorigenic M2 macrophage.

Figure 5.

Comparison of V-1520 accumulation in TAMs in control, KSC mice and pancreatitis-associated inflammatory macrophages in KC mice. A, Representative images of major organs from KSC and KC mice captured using the Curadel RP-1 OSN system with white light (first row), fluorescent light (second row), and a merge of white light and fluorescent light (third row). Pancreata are indicated with yellow arrows. B, Quantitative uptake values for V-1520 according to Curadel RP-1 OSN–based imaging of mouse pancreata expressed as the pancreas/muscle ratio. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, ns= non significance. C, Images of pancreatic tissue immunohistochemically stained for CD68 comparing the influx of macrophages in the pancreata of control, KSC and KC mice. Scale bar, 50 μm. D, Quantification of percentage of CD68 positivity in the stroma of pancreatic tissue of control, KSC and KC mice using HALO software. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance ****P < 0.0001, ns= non significance.

Discussion

One of the challenges during surgical resection of pancreatic tumors is the identification of premalignant lesions which have the potential to progress to more aggressive PDAC over time and thereby increase the chance of recurrence (35). In the present study, we explore V-1520, a targeted intraoperative FGS tracer targeting TSPO (16) for preclinical identification of pancreatic cancer. To evaluate the capability of V-1520 in identifying high-risk premalignant pancreatic lesions at an early stage, we used early postnatal (4–5 weeks) KSC mice in which we observe histologically confirmed lesions resembling PanIN and IPMNs. In vivo and ex vivo studies demonstrate that V-1520 can be used for identification of premalignant lesions in these mice (35). The efficacy of an FGS tracer is dependent upon its specificity in delineating tumors from healthy tissue (36). Through in vivo and ex vivo imaging, we demonstrated that V-1520 localizes specifically to diseased pancreatic tissue but not healthy pancreas. We thus anticipate the use of V-1520 as a fluorescent probe for FGS to enable visualization of high-risk premalignant lesions, which often go unidentified in conventional surgery. We found that V-1520 exhibited hepatobiliary and renal clearance. Under some circumstances, non-tumor fluorescence from these organs might interfere with tumor imaging. This condition is expected to be much less pronounced in larger animals or humans, where the pancreas is well-exposed, and background signal from adjacent organs is typically manageable during intraoperative imaging.

The TME surrounding tumor cells plays a crucial role in regulating tumor behavior, including proliferation, invasion, and metastasis (37). It encompasses not only stromal cells but also immune cells, tumor cells, and signaling molecules (38). A significant challenge in surgical resection of pancreatic tumor is ensuring the complete removal of cancerous tissue (39). Thus, achieving a clear resection margin during tumor removal is crucial for precise surgery. We hypothesized that imaging TME components during cancer surgery could guide surgeons in locating and resecting all malignant lesions. Among the various cell types in the TME, TAMs are of great interest owing to their dual roles in promoting tumor growth and mediating immune response (40). Whereas traditional FGS agents selectively target cancer cells with fluorescent dyes, the infiltration of TAMs in TME indicates that imaging of TAMs specifically could significantly enhance intraoperative identification and excision of malignant tissues. The expression of TSPO in TAMs encouraged us to explore the potential of V-1520 in identification and tracking of TAMs in the pancreatic TME (31,41,42). In the present study, we demonstrated that V-1520 identified macrophages expressing TSPO in pancreatic tumor. Thus, we anticipate that V-1520 can mark tumor boundaries by its uptake in TAMs, which could help achieve complete resection of pancreatic tumors and their TMEs while preserving healthy pancreatic tissue. Our study aligns well with the Mirna et al., where they tracked macrophage infiltration in pancreatic cancer using the TSPO radiotracer [11C]PBR28 for microPET imaging (30). Furthermore, we found that pancreatic uptake of V-1520 in KC mice with an intact Smad4 gene, which develop pancreatitis and low-grade PanIN but rarely develop pancreatic cancer (34) did not exceed background. The present study demonstrates that V-1520 was readily taken up by TSPO-expressing TAMs but not readily by macrophages within the context of pancreatitis, suggesting the utility of V-1520 for FGS. These data suggest that TAMs are useful surrogates for identifying very early-stage pancreatic lesions, which is conceptually analogous to other approaches targeting the TME, such as imaging fibroblast activated protein (FAP) (43,44) and using FAP as a marker for FGS (45,46). Due to the limited expression of FAP in normal tissues, it has emerged as an attractive target for detecting tumor in dense stromal components such as pancreatic, breast and colorectal cancer. Similarly, considering the critical role of TAMs in TME of stromal rich tumors, we anticipate that V-1520 may serve as a valuable tool for tracking TAM and enhancing lesion detection in comparable oncogenic settings.

Within the scope of the current study, we did not establish a threshold lesion detection; further surgery-based studies in an operating theater-like setting will be required. Additionally, future studies should likely progress beyond the murine systems here and consider larger, more human-scale animal models such as swine. We anticipate that such studies would be well-suited to evaluate the smallest detectable lesion during pancreatic tumor resection with V-1520. Additionally, while NIR dyes offers high contrast, their limited tissue penetration remains a challenge, particularly in larger animal models. To overcome this, we propose integrating preoperative PET imaging with [18F]V-1008 (16,17,21) for deeper anatomical context, while intraoperative exposure of the pancreas is also expected to mitigate penetration tissues. Clinical trials using IRDye 800CW (e.g., NCT02736578, NCT03384238) have already demonstrated the feasibility of NIR imaging in pancreatic cancer for margin assessment, and lymphadenectomy. We also acknowledge that, while V-1520 is designed as a ligand to TSPO, its accumulation profile may extend beyond TAMs. Other cell types in the TME, which contribute to tumor heterogeneity, may also accumulate the tracer. Minimal uptake in KC mice further suggests a heterogenous cellular distribution. Future studies will be necessary to map V-1520 localization at single cell resolution, especially in systems that better reflect human immunity.

In summary, we demonstrated that V-1520 can be used intraoperatively to identify high-risk pancreatic lesions among their respective TME. We propose that additional studies to exploit the translational value of this approach are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Surgery remains the only curative option for pancreatic cancer. However, during surgical procedures, premalignant, frequently microscopic lesions of high-risk potential are often missed, leading to recurrence. Identification and subsequent removal of such lesions could enhance the overall efficacy of resection, thereby reducing the likelihood of recurrence and improving outcomes. We previously identified translocator protein (TSPO) as a biomarker of high-risk premalignant lesions. Here, we carried out preclinical studies using a genetically engineered pancreatic cancer mouse model. We demonstrate that TSPO targeted near-infrared fluorescence imaging using V-1520 is capable of identifying early pancreatic lesions demarcated by surrounding cancer-associated inflammation in contrast to benign inflammation and pancreatitis.

Acknowledgements

H.C. Manning is a Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Scholar in Cancer Research. This study was supported by a Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas grant (RR200046). The authors thank Jennifer Meyer and Charles Kingsley from the MD Anderson Small Animal Imaging Facility for their assistance with CFT. This Small Animal Imaging Facility was supported in part by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and P30CA016672. The authors acknowledge the Houston Methodist Research Institute Microscopy-ACTM core for help with confocal studies. The authors also acknowledge the MD Anderson Department of Veterinary Medicine and Surgery for their help with digital pathology. The authors thank Donald R Norwood and Editing Services, Research Medical Library, at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for editorial assistance. Supplementary Figure S2 was created using BioRender.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: Vanderbilt University has filed for patent protection for V-1520 of which H. C. Manning is a co-inventor. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by other authors.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 9]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: The unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the united states. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Cancer Institute. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 9]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/types/pancreatic/hp/pancreatic-treatment-pdq#section_1.10

- 4.Daamen LA, Dorland G, Brada LJH, Groot VP, van Oosten AF, Besselink MG, et al. Preoperative predictors for early and very early disease recurrence in patients undergoing resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. HPB. 2022;24:535–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quero G, De Sio D, Fiorillo C, Lucinato C, Panza E, Biffoni B, et al. Resection margin status and long-term outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma: A tertiary referral center analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16:2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chari ST. Detecting Early Pancreatic Cancer: Problems and Prospects. Semin Oncol. 2007. Aug;34(4):284–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagaya T, Nakamura YA, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Fluorescence-guided surgery. Front Oncol. 2017;7:314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qi B, Crawford AJ, Wojtynek NE, Talmon GA, Hollingsworth MA, Ly QP, et al. Tuned near infrared fluorescent hyaluronic acid conjugates for delivery to pancreatic cancer for intraoperative imaging. Theranostics. 2020;10:3413–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barth CW, Gibbs S. Fluorescence image-guided surgery: a perspective on contrast agent development. In SPIE-Intl Soc Optical Eng; 2020. p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witz IP, Levy-Nissenbaum O. The tumor microenvironment in the post-PAGET era. Cancer Lett. 2006;242:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber CE, Kuo PC. The tumor microenvironment. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:172–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin MZ, Jin WL. The updated landscape of tumor microenvironment and drug repurposing. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie D, Xie K. Pancreatic cancer stromal biology and therapy. Genes Dis. 2015;2:133–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boelaars K, Rodriguez E, Huinen ZR, Liu C, Wang D, Springer BO, et al. Pancreatic cancer-associated fibroblasts modulate macrophage differentiation via sialic acid-Siglec interactions. Commun Biol. 2024;7:430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong C, Zhu Y, Xue M, Jiang Y, Zhong Y, Jiang L, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages promote pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression by inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Aging. 2021;13:3386–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen AS, Li J, Hight MR, McKinley E, Fu A, Payne A, et al. TSPO-targeted PET and optical probes for the detection and localization of premalignant and malignant pancreatic lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5914–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang D, McKinley ET, Hight MR, Uddin MI, Harp JM, Fu A, et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 5,6,7-substituted pyrazolopyrimidines: Discovery of a novel TSPO PET ligand for cancer imaging. J Med Chem. 2013;56:3429–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bardeesy N, Cheng KH, Berger JH, Chu GC, Pahler J, Olson P, et al. Smad4 is dispensable for normal pancreas development yet critical in progression and tumor biology of pancreas cancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20(22):3130–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ijichi H, Chytil A, Gorska AE, Aakre ME, Fujitani Y, Fujitani S, et al. Aggressive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice caused by pancreas-specific blockade of transforming growth factor-β signaling in cooperation with active Kras expression. Genes Dev. 2006;20(22):3147–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang D, Nickels ML, Tantawy MN, Buck JR, Manning HC. Preclinical Imaging Evaluation of Novel TSPO-PET Ligand 2-(5,7-Diethyl-2-(4-(2-[18F]fluoroethoxy)phenyl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl)-N,N-diethylacetamide ([18F]VUIIS1008) in Glioma. Mol Imaging Biol. 2014;16(6):813–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tantawy MN, Charles Manning H, Peterson TE, Colvin DC, Gore JC, Lu W, et al. Translocator Protein PET Imaging in a Preclinical Prostate Cancer Model. Mol Imaging Biol. 2018;20(2):200–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell AE, Vlacich G, Zhao ZY, McKinley ET, Kay Washington M, Charles Manning H, et al. Inducible loss of one Apc allele in Lrig1-expressing progenitor cells results in multiple distal colonic tumors with features of familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol [Internet]. 2014;307:16–23. Available from: http://www.ajpgi.org [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall M V, Draney D, Sevick-Muraca EM, Olive DM. Single-dose intravenous toxicity study of IRDye 800CW in sprague-dawley Rats. Mol Imaging Biol. 2010. Dec;12(6):583–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mytidou C, Koutsoulidou A, Zachariou M, Prokopi M, Kapnisis K, Spyrou GM, et al. Age-Related Exosomal and Endogenous Expression Patterns of miR-1, miR-133a, miR-133b, and miR-206 in Skeletal Muscles. Front Physiol. 2021;12:708278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zamboni G, Hirabayashi K, Castelli P, Lennon AM. Precancerous lesions of the pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:299–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Distler M, Aust D, Weitz J, Pilarsky C, Grützmann R. Precursor lesions for sporadic pancreatic cancer: PanIN, IPMN, and MCN. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:474905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takaori K Current understanding of precursors to pancreatic cancer. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007. May;14(3):217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muller M, Haghnejad V, Schaefer M, Gauchotte G, Caron B, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. The immune landscape of human pancreatic ductal carcinoma: Key players, clinical implications, and challenges. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foss CA, Liu L, Mease RC, Wang H, Pasricha P, Pomper MG. Imaging macrophage accumulation in a murine model of chronic pancreatitis with 125I-Iodo-DPA-713 SPECT/CT. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:1685–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanfranca MP, Lazarus J, Shao X, Nathan H, Di Magliano MP, Zou W, et al. Tracking macrophage infiltration in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer with the positron emission tomography tracer [11C]PBR28. J Surg Res. 2018;232:570–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weidner L, Lorenz J, Quach S, Braun FK, Rothhammer-Hampl T, Ammer LM, et al. Translocator protein (18kDA) (TSPO) marks mesenchymal glioblastoma cell populations characterized by elevated numbers of tumor-associated macrophages. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2023;11:147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz MA, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhalerao N, Chakraborty A, Marciel MP, Hwang J, Britain CM, Silva AD, et al. ST6GAL1 sialyltransferase promotes acinar to ductal metaplasia and pancreatic cancer progression. JCI Insight. 2023;8:e161563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang HH, Moro A, Takakura K, Su HY, Mo A, Nakanishi M, et al. Incidence of pancreatic cancer is dramatically increased by a high fat, high calorie diet in KrasG12D mice. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kolbeinsson HM, Chandana S, Wright GP, Chung M. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review of Current Treatment and Novel Therapies. J Invest Surg. 2023;36:2129884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenthal EL, Warram JM, De Boer E, Basilion JP, Biel MA, Bogyo M, et al. Successful translation of fluorescence navigation during oncologic surgery: A consensus report. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:144–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Q, Shao X, Zhang Y, Zhu M, Wang FXC, Mu J, et al. Role of tumor microenvironment in cancer progression and therapeutic strategy. Cancer Med. 2023;12:11149–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J, Zhang J, Gao Y, Jiang Y, Guan Z, Xie Y, et al. Barrier permeation and improved nanomedicine delivery in tumor microenvironments. Cancer Lett. 2023;562:216166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tachezy M, Bockhorn M, Gebauer F, Vashist YK, Kaifi JT, Izbicki JR. Bypass surgery versus intentionally incomplete resection in palliation of pancreatic cancer: Is resection the lesser evil? J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(5):829–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan Y, Yu Y, Wang X, Zhang T. Tumor-Associated macrophages in tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 2020;11:583084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cosenza-Nashat M, Zhao ML, Suh HS, Morgan J, Natividad R, Morgello S, et al. Expression of the translocator protein of 18 kDa by microglia, macrophages and astrocytes based on immunohistochemical localization in abnormal human brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2009. Jun;35(3):306–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng J, Boisgard R, Siquier-Pernet K, Decaudin D, Dollé F, Tavitian B. Differential expression of the 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO) by neoplastic and inflammatory cells in mouse tumors of breast cancer. Mol Pharm. 2011;8:823–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, Huang J, Gong F, Cai Z, Liu Y, Tang G, et al. Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of a novel PET/fluorescence dual-modality probe targeting fibroblast activation protein. Bioorg Chem. 2024;146:107275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watabe T, Liu Y, Kaneda-Nakashima K, Shirakami Y, Lindner T, Ooe K, et al. Theranostics targeting fibroblast activation protein in the tumor stroma: 64Cu- And 225Ac-labeled FAPI-04 in pancreatic cancer xenograft mouse models. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:563–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roy J, Hettiarachchi SU, Kaake M, Mukkamala R, Low PS. Design and validation of fibroblast activation protein alpha targeted imaging and therapeutic agents. Theranostics. 2020;10:5778–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mukkamala R, Lindeman SD, Kragness KA, Shahriar I, Srinivasarao M, Low PS. Design and characterization of fibroblast activation protein targeted pan-cancer imaging agent for fluorescence-guided surgery of solid tumors. J Mater Chem B. 2022;10:2038–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included in the article and its supplementary materials or are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.