Abstract

Preeclampsia is a pregnancy-specific syndrome, linked to oxidative stress, affecting 5–8% of pregnancies, with no effective treatment available. Here, diaryl-hydrazones have been designed, synthesized, and investigated as mitochondria-targeting antioxidants to reduce placental oxidative stress and mitigate preeclampsia symptoms. The design, based on density functional theory studies, revealed that conjugated electron structure with the NH-motif appeared to explain their effect. Thirty compounds were synthesized and tested in three assays, where they exhibited excellent radical scavenging activity, significantly greater than that of the standard, Trolox. Based on the data, eight compounds were selected for cell-based assays. Oxidative stress was induced in human trophoblast cells and assessed whether the compounds reduced downstream antiangiogenic responses using ascorbic acid and MitoTEMPO as standards. The pretreatment with the hydrazones reduced mitochondrial superoxide and sFLT-1 production in H2O2-exposed trophoblast cells, indicating that mitochondrial oxidative stress and the anti-angiogenic response can be alleviated by these compounds.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia (PE) is a common, life-threatening complication in pregnancy, characterized by high blood pressure putting the mother at risk of eclampsia and kidney dysfunction.1 PE affects about 5–8% of pregnancies and is highly prevalent among African American women. It is estimated to cause 70,000–80,000 maternal and 500,000 perinatal deaths worldwide annually.2 There is no clear pathogenesis or cure, thus an effective treatment for PE is an unmet medical need. It has been shown that placental oxidative stress is a major contributor to PE.3–5 In previous studies, several natural antioxidants and synthetic derivatives have been tested with limited success mostly due to delivery issues.6 The presence of oxidative species, such as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS, RNS) are both crucial for cell survival and reactive enough to cause cell death, thus the body needs to maintain balanced redox homeostasis.7 To control the levels of free radicals, the body utilizes endogenous and exogenous antioxidants to scavenge the radicals when necessary to avoid oxidative stress and damage onto the cells.8 Oxidative stress causes damage to a wide variety of biomolecules (i.e., lipids and DNA), potentially causing cellular death.9 Overproduction of ROS and RNS contributes to the development and progression of many ailments, such as aging, cardiovascular diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, cancer, or multiple sclerosis.10–14 Among these disorders, preeclampsia is one of the most serious complications of pregnancy, characterized by hypertension and proteinuria occurring after 20 weeks.1 It is associated with significant maternal, fetal, and neonatal morbidity and mortality.2 No disease-altering treatments are available, current care is limited to treating symptoms: mitigating hypertension and alleviating eclampsia. While the etiology and pathogenesis of PE is elusive, it is currently believed that placental ischemia, due to impaired spiral artery remodeling, is the primary culprit.5a It has been proposed that the ischemic state will cause oxidative stress and impair endothelial and trophoblast function that may contribute to the pathogenesis of PE. In PE, pregnancy significant ROS production in the placenta has also been reported.15 In addition, the mitochondrial electron transport chain enzyme, cytochrome c oxidase, activity is diminished in the syncytiotrophoblast cells of the placenta, implicating mitochondrial damage/dysfunction as a potential contributor to pathogenesis of PE.14 The release of ROS/RNS can stabilize hypoxia inducible factor (HIF-1α) which will induce transcription of antiangiogenic factors such as soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFLT-1) and soluble endoglin (sEng).16,17 The antiangiogenic factors are released into the maternal circulation; and their actions are thought to disrupt the maternal endothelium and result in hypertension, proteinuria, and other systemic manifestation of PE (Figure 1).18

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of human preeclampsia development and the potential intervention used in this work.

Given that placental oxidative stress may be an early trigger in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia, therapies that enhance antioxidant pathways have been proposed as treatments. The first attempts in clinical trials have shown that maternal vitamin C and E therapy do not prevent PE,19 likely due to the inability of the antioxidants to reach the site of oxidative stress (i.e., mitochondrial matrix).20 Therefore, there is an interest in developing alternate strategies to reverse oxidative stress in the placenta. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants21 have been used in22,23 In models of ischemia-reperfusion injury22,23 and are an attractive alternative treatment as preeclamptic tissue is characterized by profound mitochondrial oxidative stress.24,25 Data has also shown promise that delivery of H2S to the mitochondria of primary trophoblast cells could alleviate oxidant stress and sFLT-1 upregulation in a hypoxia model in vitro.3c This data implicate that the use of antioxidants at an early stage have potential to prevent the trophoblast and endothelial injury that is observed in PE.

In our earlier work, we reported the design, synthesis and application of hydrazone-based antioxidants that acted as multifunctional anti-AD agents and exhibited excellent radical scavenging effects. The starting point was resveratrol (Figure 2), a biologically active natural product26,27 and effective antioxidant.28

Figure 2.

General structures and electrostatic potential maps of hydrazones and resveratrol.

However, resveratrol is too polar to reach most target sites. In contrast, the diaryl hydrazones offer a large degree of structural similarity with more hydrophobic character, showing excellent radical scavenging, often three times higher than that of the controls.29 Density functional theory (DFT) studies also provided insights into the origin of their high antioxidant potential.30 In addition to being potent radical scavengers,29–31 hydrazones are nontoxic and possess a variety of biological activities, yet their potential as a drug candidate is underexplored.32,33

Continuing our efforts34 on the development of synthetic hydrazones for mitochondrial antioxidant therapy to alleviate PE, herein we describe the design, synthesis, and evaluation of organofluorine hydrazones as potential PE therapeutics.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemistry: Design and Synthesis.

As mentioned above, resveratrol (Figure 2), a natural polyphenolic antioxidant with a stilbene core, served as a starting point in our inhibitor design. Hydrazones are highly similar molecular entities, exhibiting comparable size and structural rigidity with an overall higher lipophilicity. Another important factor is that the potential tautomeric equilibrium (Forms I and II, Figure 2) would provide the same continuous conjugation and nearly uniform π-electron delocalization similar to resveratrol, via a 4 atom-4-electron system that includes the two nitrogen atoms. The conjugation appears to be important due to the likely hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) radical scavenging mechanism,35 the hydrazones presumably act through. Our extensive DFT calculations on the electronic and structural features of hydrazones provided more insight into the role of the substituents in affecting activity. It has been found that the N–H bond dissociation energy (BDE, the main driver of the HAT mechanism), ionization potential (IP), and the partition coefficient (logP) of the compounds showed strong correlation with the experimental activity.30a In addition to these characteristics, the HOMO energy, the HOMO–LUMO gap, dipole moment (DP), proton affinity (PA), and the Hammett constant of the substituents showed good to excellent correlation with the experimental activities and related to the delocalized electron structure. Thus, we included hydrazones with extended network of conjugation adding additional aromatic rings to the design as shown in Figure 3. This involved two ways; (i) using terephthalaldehyde-linked with two hydrazine molecules, or (ii) changing the starting benzaldehyde unit to naphthyl and anthracenyl or coumarin-based aldehydes.

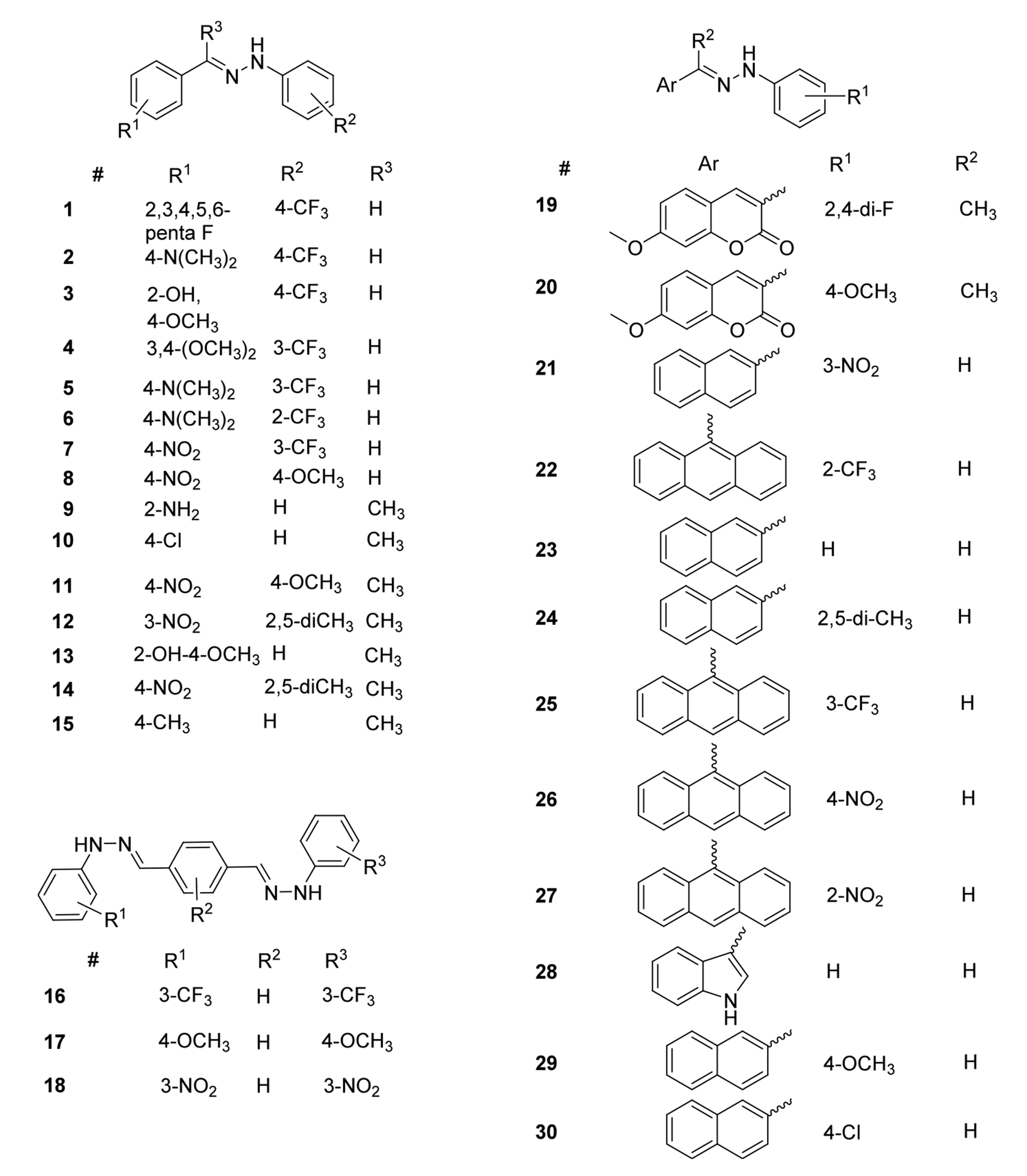

Figure 3.

Structures of synthesized hydrazones used in this study.

The other crucial element in our design was the introduction of fluorine into the hydrazone core that is expected to further enhance the biological properties via electronic effects as well as improving the membrane permeability of the compounds. The beneficial effects of fluorine incorporation into small molecule drugs are known to improve their biological properties.36 As a result, fluorine substitution became a mainstream approach in drug development to enhance the membrane permeability of therapeutic candidates.37,38 Fluorine containing groups used in this study will include CF3 and aryl-F which are highly stable and would not yield toxic products as they are largely resistant to metabolic degradation. The presence of polar groups ensures proper water solubility, and the fluorine addition improves lipophilicity, thus resulting in favorable pharmacokinetic properties.39

The above detailed considerations led to the design of several compounds. The structures of the hydrazones synthesized for this study are illustrated in Figure 3.

After the design, the structures were subjected to a SwissADME screening40 to evaluate their drug-like properties and synthetic accessibility. The full set of data is tabulated in Table S1 (see Supporting Information). The analysis of the data indicates that the design appears appropriate, all compounds show proper drug-like properties. Most molecules have no or just 1 Lipinski violation,41 other violations such as Ghose-,42 Veber-,43 Egan-,44 and Muegge-violations45 are also minimal (mostly zero or 1) for the above set of compounds. The number of PAINS alerts46 are also quite favorable, most compounds have zero PAINS alerts, and no compound received more than 1, indicating that the design resulted in reasonable structures. The compounds also exhibit relatively easy synthetic accessibility scores between about 2.5–3 indicating that their synthesis is likely achievable. In addition, the hydrazones appear to be highly stable in a powder/crystalline form for an extended period of time (>1 year). When dissolved for the assays they are stable for several hours, up to a day. After 7 days of storage in solution, independently of the conditions, they show some signs of deterioration.47

Based on the above design and analysis, a variety of hydrazones were synthesized from commercially available arylaldehydes (including the bifunctional terephthalaldehyde) and arylhydrazines. The basic synthetic procedure for preparation of these compounds is a simple rapid, catalyst-free reaction that yields the crystalline products upon cooling the reactions to −20 °C, as has been described before29 (Figure 4).

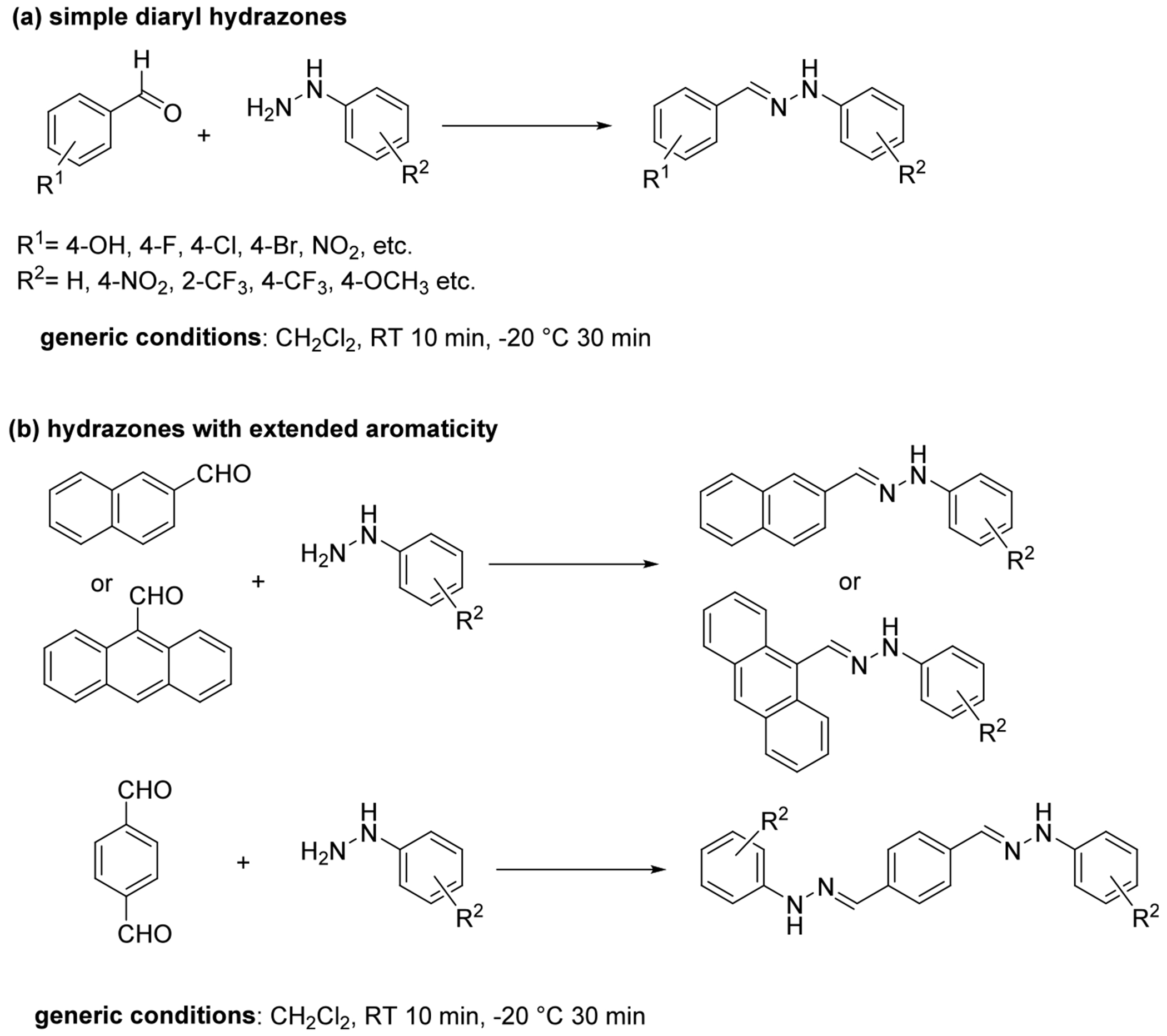

Figure 4.

Synthesis of the hydrazones used in this study.

The starting aldehydes and hydrazines were all commercially readily available chemicals and were selected to ensure a broad substituent scope for the hydrazones including electron donating or electron withdrawing substituents, including fluorine-containing moiety (Ar–F, or CF3) to enhance the lipophilicity of the compounds. Overall, 30 compounds were prepared and characterized for this study.

Biochemical Evaluation.

After the syntheses were completed, the antioxidant activity of the compounds was evaluated by three common antioxidant assays such as the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH),14 2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethyl-benzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS)48, and oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assays.49 In order to put the observed effects into context, the activity of hydrazones is presented as Trolox equivalents (in DPPH and ABTS assays) or Trolox equivalent concentration (in ORAC assay) as described in the Experimental section below. Trolox (Figure 5), a vitamin E analog, is a well-known reference antioxidant commonly used for this purpose.50 Other reference antioxidants that were applied in the cell biology assays were ascorbic acid, and MitoTEMPO (Figure 5). The data is shown in Figures 5–8. It must be noted that the concentrations used in these assays were different and selected based on earlier works.30 These concentrations allowed for the most variety in radical scavenging percentages so that all the antioxidants show radical scavenging that is neither near 100% nor 0%, thus reflecting the differences between the hydrazones as well as the standards in scavenging the target radicals. In addition, it allows for better standardization to the reference antioxidant, Trolox. Standardizing the radical scavenging percentages to that of Trolox takes into account any small deviations that could result from the assays. In the DPPH and ABTS assays, their respective antioxidant concentrations give a Trolox radical scavenging percentage that is ideal for identifying potent antioxidants. In the ORAC assay, Trolox is an extremely good radical scavenger thus a calibration curve of it is needed but the hydrazones still show a variety of radical scavenging performance. Higher antioxidant concentrations in this assay would lead to nearly 100% radical scavenging for many hydrazones, eliminating the potential for comparison.

Figure 5.

Structure of Trolox, ascorbic acid and MitoTEMPO reference compounds used for comparison in the assays.

Figure 8.

ORAC radical scavenging potential of the hydrazone derivatives (1–30) used in this study, measured at 80 μM antioxidant concentration, expressed in Trolox equivalent concentration. The values are shown as the means of the Trolox equivalent concentration ± standard deviation, where the number of independent repeats is three.

The results in Figures 6–8 are expressed in comparison to the activity of Trolox used as the reference antioxidant, either in Trolox equivalents (DPPH, ABTS, Figures 6, 7) or Trolox equivalent concentration (ORAC, Figure 8) due to the kinetic nature of the ORAC assay. The data indicate that the hydrazones are highly potent radical scavengers as the majority of the tested compounds show higher activity than that of Trolox. It is also clear from Figures 6–8 that the activity and behavior of the hydrazones toward the different radicals used in the assays changes significantly. While the hydrazones exhibit activity that is several times higher than that of Trolox in the DPPH and ABTS assays (Figures 6, 7), they show similar or somewhat lower activity than the reference in the ORAC assay (Figure 8). That is the main reason to test the antioxidants in different assays, to obtain a more holistic evaluation. The assays have their own strengths and limitations, as well as the radical scavenging mechanism of the various antioxidants affects their activity in the assays, for instance Trolox (or phenols in general) shows an outsized effect in the ORAC assay. The error bars plotted in Figures 6–8 also (within 5–10%) confirm that the assays provided sufficiently reproducible data.

Figure 6.

DPPH radical scavenging potential of the hydrazone derivatives (1–30) used in this study, measured at 200 μM antioxidant concentration, expressed in Trolox equivalents. The values are shown as the means of the Trolox equivalents ± standard deviation, where the number of independent repeats is four.

Figure 7.

ABTS radical scavenging potential of the hydrazone derivatives (1–30) used in this study, measured at 500 μM antioxidant concentration, expressed in Trolox equivalents. The values are shown as the means of the Trolox equivalents ± standard deviation, where the number of independent repeats is three.

The combination of the data from the three assays also revealed that the most potent compounds are at the beginning of the list, compounds 1-17, and the compounds with extended aromatic structures do not appear to stand out in the assays except 20 in the ORAC assay (Figure 8). Considering the structure–activity relationship (vide infra) and potential physical parameters of the compounds that significantly contribute to their ADME properties, particularly potential membrane permeability, eight compounds have been selected for cell-based assays.

Biological Evaluation.

As discussed in the introduction, oxidative stress appears to be an important factor in PE pathogenesis; therefore, novel antioxidant therapy is expected to improve trophoblast and/or endothelial cell function and may lead to improved angiogenic balance in vitro. The hydrazones showed significant antioxidant potential in the above radical scavenging assays and their in silico predicted pharmacokinetic features (Table S1) appeared to be superior to those of natural antioxidants. Thus, the cell biology assays were designed to reveal whether the compounds can also be effective in cellular environment. Based on the radical scavenging assay results described above, eight compounds (and 2 reference antioxidants: ascorbic acid and Trolox) were subjected to cell-based assays. The selected structures are summarized in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Structures of hydrazones selected for cell biology assays.

The compounds have been tested to observe whether the antioxidant pretreatment was able to reduce the sFLT-1 protein expression in H2O2-exposed human trophoblast cells. Pregnancy complications are associated with placental oxidative stress, which induces the stabilization of the transcription factor HIF1A and the expression of downstream antiangiogenic factors such as sFLT-1 expression in PE. In fact, the use of these biomarkers has recently been approved by the FDA to predict PE development risk early in pregnancy.51 Therefore, we employed the human trophoblast HTR8/SVneo cell line to determine the effect of various hydrazone-based antioxidants on sFLT-1 expression.

First, we evaluated the oxidative stress response in HTR-8/SVneo cells. Cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of H2O2 (40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 μM) for 24 h. CCK-8 assay was used to assess cell viability, as shown in Figure S106. We detected a dose-dependent increase in cytotoxicity of HTR-8/SVneo cells in response to H2O2. The IC50 value of H2O2 concentration in this system was 100 μM (which depicts 50% killing of the HTR-8/SVneo cells). Based on this finding, in subsequent experiments 100 μM H2O2 treatment was used to induce oxidative stress. The corresponding sFLT1 levels were also measured and showed H2O2 concentration-dependent increase when normalized for viable cell count (Figure S107).

Cells were pretreated with hydrazones 0.1–50 μM 30 min before the addition of 100 μM H2O2 to the cells. The cells were then incubated for a further 20 h in the same medium (containing hydrazones and hydrogen peroxide). We found that the various hydrazone pretreatments all reduced sFLT-1 protein expression but with different efficiencies in H2O2-exposed human trophoblast cells as depicted in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Antioxidant pretreatment reduced sFLT-1 protein expression in H2O2-exposed human trophoblast cells. sFLT-1 ELISA in HTR8 cells pretreated with compounds 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 16 or reference antioxidant MitoTEMPO (MT) for 30 min, then exposed to 100 μM H2O2 or sham (summary of 5 repeat experiments). *P < 0.05 compared to H2O2; **P < 0.01 compared to H2O2, ***: p < 0.001 compared to H2O2 by Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc.

The results indicate that H2O2 increased the sFLT-1 expression in the trophoblast cells, as expected (Figure 10 red column). The pretreatment with all hydrazones reduced sFLT-1 expression in HTR8/SVneo cells to a varied extent. The most significant mitigating effect was achieved with compounds 4 and 5. The effect of these compounds is about 10–40% better than that of the reference antioxidant, MitoTEMPO (a mitochondria targeting antioxidant52,53). This is a significant result since sFLT-1 is known to induce the cardinal features of preeclampsia in vivo;18 therefore, the reduction observed here could have significant therapeutic benefits in the in vivo models as well.

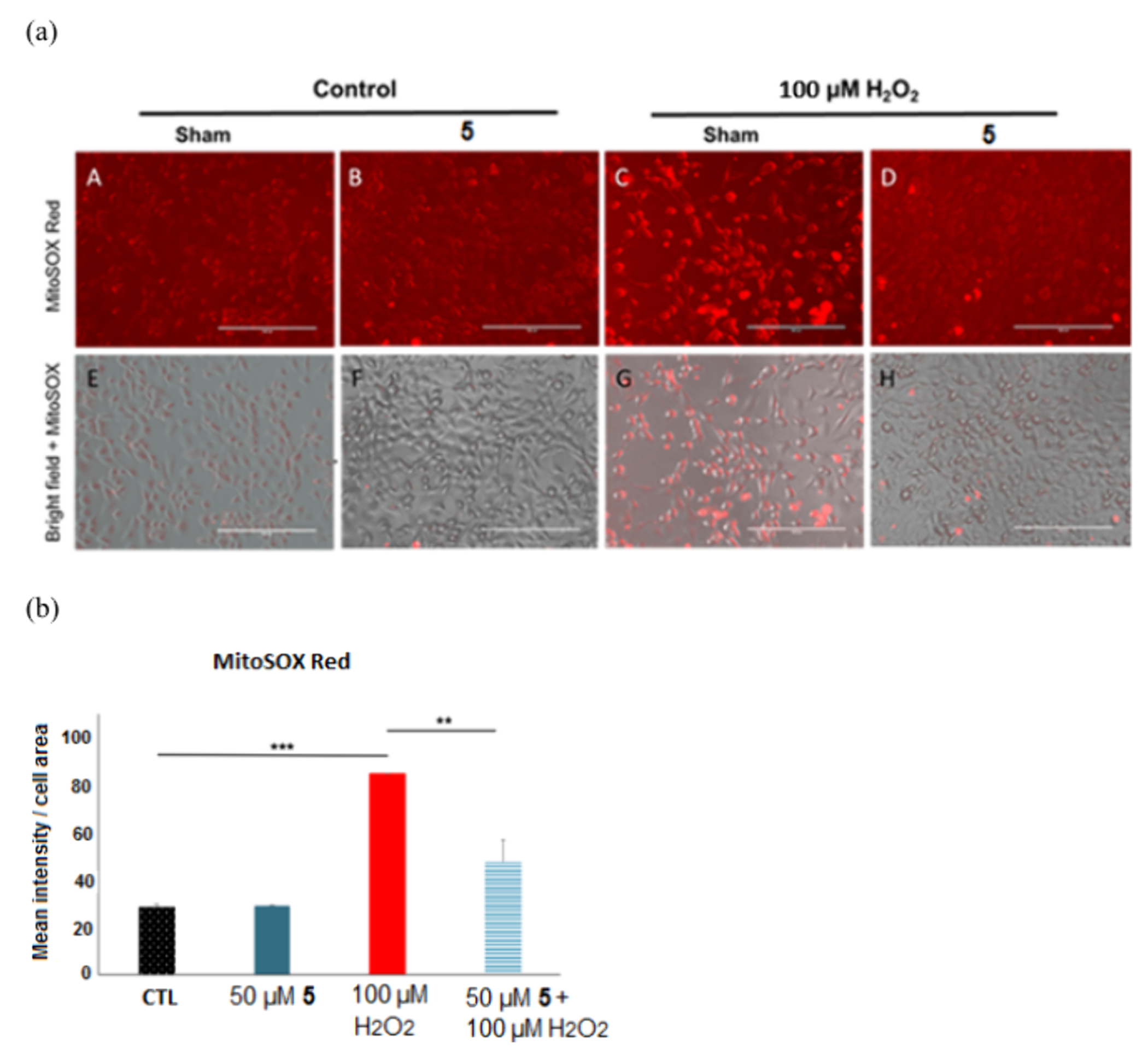

Based on the above in vitro antioxidant assays compound 5 was proven to be the one with the highest activity therefore we selected this compound for further cell-based assays. Immunofluorescence analysis of MitoSOX Red (A-D, superoxide production) in HTR8 cells was carried out, with 50 μM 5 treatment for 30 min, which was then exposed to 20 h H2O2.

The data in Figure 11 clearly indicates that a pretreatment by 5 reduced mitochondrial-derived ROS production in H2O2-exposed trophoblasts cells (HTR8). Comparing the H2O2-treated cells with those where compound 5 was also applied, about 50% reduction can be observed in the production of ROS in the mitochondria. While the positive effects of 5 have been established above, this data supports the original hypothesis that the organofluorine hydrazone acts via a mitochondrial antioxidant process.

Figure 11.

Immunofluorescence analysis of MitoSOX Red (a) A-D: Immunofluorescence analysis of MitoSOX Red: mitochondrially derived superoxide production in HTR8 cells treated with vehicle (A) or 50 μM compound 5 (B) for 30 min, then exposed to 20 h with 100 μM H2O2 with compound 5 (D) or without (C) (Bars: 50 μm). E-H: MitoSOX Red images overlaid on bright field images of the trophoblast cell culture (E-H) demonstrating maintained cell viability at all concentrations; vehicle (E), 50 μM compound 5 (F), 100 μM H2O2 (G), 100 μM H2O2 with compound 5 (H). (b) Quantitation of MitoSOX Red (I) immunofluorescence in trophoblasts: OD per area (pixels2) of cell surface area was calculated in 3 high-power fields per sample (n = 4 per group). Mann–Whitney-U-test, median [IQR]. Control vs 100 μM H2O2: ***: p < 0.001, 100 μM H2O2 vs H2O2 + 5: **: p < 0.01.

Structure–Activity Relationship.

In the above experimental data, we described the efficacy of the compounds in a variety of chemical and biological assays. The radical scavenging mechanism of antioxidants can be broken down into two main processes: single electron transfer (SET) or hydrogen atom transfer (HAT). Depending on how these events are sequenced, we can classify radical scavenging pathways as sequential electron transfer-proton transfer (SET-PT), sequential proton loss-electron transfer (SPLET), sequential proton loss–hydrogen atom transfer (SPLHAT) or a hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) and radical adduct formation (RAF).54 Different antioxidant assays associated with different mechanisms, for instance, while ORAC is based on hydrogen atom transfer, ABTS and DPPH are considered mixed assays that include both electron and hydrogen transfer.55 Therefore, it is critical to investigate the antioxidant activity of compounds across different assay environments.

Upon closer examination of Figures 6, 7, and 8, it is evident that compounds 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 13, and 17 demonstrated superior scavenging activity across all three assays, even outperforming the reference antioxidant, Trolox. Generally, most compounds showed higher activity in the ABTS assay compared to the DPPH assay. Within compounds 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, a push–pull-like system is observed, where one phenyl ring is substituted with electron-donating groups such as −N(Me)2, hydroxyl, or methoxy groups, while the other phenyl ring is substituted with an electron-withdrawing (− CF3) group.56 On the other hand, the pattern is not determining, compounds 1 and 7, which have electron-withdrawing substituents on both aryl groups of the molecule, also exhibited notable antioxidant activity. The introduction of a methyl group to the hydrazone moiety showed mixed activity results in compounds 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, depending on the substitution pattern. Compounds 11, 12, and 14 exhibited the weakest activity in the DPPH and ABTS assays, with a common feature being the NO2 group substituent. Extending the π system linearly in compounds 15, 16 and 17, particularly with electron-donating substituents like −OMe, resulted in a superior overall activity profile. Interestingly, asymmetric expansion of the π system did not consistently enhance the activity. Notable discrepancies were observed among compounds 20, 21, 22, 28, and 29. Compounds 21 and 22 exhibited strong activity in the ABTS and DPPH assays but performed poorly in the ORAC assay. Conversely, compounds 20, 28, and 29 demonstrated excellent activity in the ORAC assay but showed limited effectiveness in the ABTS and DPPH assays. In comparing the naphthyl and anthryl derivatives, the former group’s compounds 21, 23, 24, 29, and 30 matched in performance the reference antioxidant Trolox in the DPPH and ABTS assays but exhibited a mixed activity profile in the ORAC assay, depending on the substitution pattern. Specifically, compounds 23, 24 (2,5-diMe), and 29 (4-OMe), either unsubstituted or with electron-donating groups, showed good performance in ORAC. In contrast, compounds 21 (3-NO2) and 30 (4-Cl), which contain electron-withdrawing groups, demonstrated minimal activity in the ORAC assay. Overall, while the anthryl derivatives generally underperformed compared to the naphthyl derivatives, they exhibited moderate activity in both the DPPH and ABTS assays, except for compound 27.

To elucidate the reasons behind the compounds’ activity profiles, a theoretical analysis was performed using density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B3LYP/6–311++G(d,p) (Table 1)57 as well as M06–2X/6–311++G(d,p) (Table 2) level of theories in gas phase, utilizing the Gaussian 09 program suite.58 The ORCA 6.0,59 global optimizer and conformer generator GOAT program was utilized for the initial conformation analysis. As previously mentioned, eight promising compounds were selected for further biological testing and detailed theoretical analysis.

Table 1.

Calculated Molecular Descriptors for the Selected Hydrazone Derivativesa

| Compound |

N–H distance (Å) |

Dipole moment (Debye) |

LogPo/wb |

HOMO (hartree) |

LUMO (hartree) |

HOMO–LUMO gap (eV) |

BDE (kcal/mol) |

PA (kcal/mol) |

IP (eV)/(kcal/mol) |

Spin density N radicalc |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0170 | 3.9999 | 2.16 | −0.2331 | −0.0926 | 3.8251 | 79 | 323.68 | 7.71 | 177.80 | 0.5005 |

| 2 | 1.0155 | 8.5192 | 2.77 | −0.1918 | −0.0548 | 3.7282 | 75 | 337.89 | 6.43 | 148.31 | 0.4707 |

| 3 | 1.0165 | 8.2403 | 2.46 | −0.2022 | −0.0553 | 3.9951 | 76 | 338.44 | 6.77 | 156.13 | 0.5216 |

| 4 | 1.0153 | 5.4930 | 2.92 | −0.2002 | −0.0572 | 3.8912 | 75 | 337.24 | 6.69 | 154.22 | 0.4913 |

| 5 | 1.0153 | 6.4249 | 2.78 | −0.1889 | −0.0509 | 3.7565 | 74 | 339.32 | 6.37 | 146.83 | 0.4767 |

| 6 | 1.0167 | 4.1790 | 3.09 | −0.1877 | −0.0476 | 3.8120 | 74 | 340.27 | 6.30 | 145.17 | 0.4272 |

| 7 | 1.0163 | 8.6191 | 2.05 | −0.2317 | −0.1138 | 3.2098 | 77 | 320.23 | 7.65 | 176.44 | 0.4877 |

| 16 | 1.0158 | 5.4401 | 3.31 | −0.2063 | −0.0867 | 3.2531 | 75 | 327.49 | 6.68 | 176.44 | 0.4700 |

(Bond distance (in Å), Dipole moment in Debye, logPo/w, HOMO and LUMO energies in hartree, band gap in eV, bond dissociation energy (BDE, in kcal/mol), proton affinity (PA, in kcal/mol), ionization potential (IP, in eV and kcal/mol). Level of theory and basis set B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p).

SwissADME, consensus.

Mulliken atomic spin densities.

Table 2.

Calculated Molecular Descriptors for the Selected Hydrazone Derivativesa

| Compound | N–H distance (Å) | Dipole moment (Debye) | HOMO (hartree) | LUMO (hartree) | HOMO–LUMO gap (eV) | BDE (kcal/mol) | PA (kcal/mol) | IP (kcal/mol) | Spin density N radicalb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0123 | 3.9522 | −0.2729 | −0.0531 | 5.9811 | 83 | 325.19 | 182.09 | 0.5262 |

| 2 | 1.0111 | 7.8066 | −0.2340 | −0.0204 | 5.8128 | 79 | 336.57 | 153.69 | 0.4988 |

| 3 | 1.0110 | 4.9488 | −0.2529 | −0.0284 | 6.1100 | 78 | 327.99 | 165.91 | 0.5271 |

| 4 | 1.0116 | 5.2512 | −0.2446 | −0.0217 | 6.0649 | 79 | 335.85 | 160.65 | 0.5180 |

| 5 | 1.0117 | 6.9349 | −0.2334 | −0.0191 | 5.8341 | 78 | 337.29 | 152.66 | 0.5018 |

| 6 | 1.0103 | 4.8829 | −0.2325 | −0.0168 | 5.8681 | 80.0 | 391.56 | 152.21 | 0.5125 |

| 7 | 1.0118 | 2.9485 | −0.2724 | −0.0746 | 5.3821 | 82 | 393.05 | 181.39 | 0.5207 |

| 16 | 1.0117 | 3.2754 | −0.2489 | −0.0524 | 5.3470 | 80.0 | 327.53 | 162.29 | 0.5117 |

(Bond distance (in Å), Dipole moment in Debye, logPo/w, HOMO and LUMO energies in hartree, band gap in eV, bond dissociation energy (BDE, in kcal/mol), proton affinity (PA, in kcal/mol), ionization potential (IP, in eV and kcal/mol). Level of theory and basis set: M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p).

Mulliken atomic spin densities.

Then, the obtained values describing physical properties have been analyzed in connection to the experimental antioxidant potential. The experimental radical scavenging data were plotted as a function of the above calculated properties, respectively, and analyzed to reveal a potential fit between the data that may help to describe the relationship between structure and activity. All plots are depicted in SI, here we only show and analyze those that exhibited a meaningful correlation (Figure 12). Several physicochemical and quantum parameters exhibited promising correlations, particularly with intrinsic reactivity indices such as BDE (referenced in Figure 12, a, b, c), IP (Figure 12, j, k, l), and PA (Figure 12, m, n, o). Generally, lower values in these variables are indicative of better antioxidant activity. The calculated BDE values showed the strongest correlation with scavenging activity in the ABTS assay (R2 = 0.81 (B3LYP), R2 = 0.88 (M06–2X)), and moderate correlations in the ORAC (R2 = 0.49 (B3LYP), R2 = 0.28 (M06–2X)) and DPPH (R2 = 0.47 (B3LYP), R2 = −0.22 (M06–2X)) assays. IP displayed high and nearly identical correlations in the ABTS (R2 = 0.69 (B3LYP), R2 = 0.67 (M06–2X)) and DPPH (R2 = 0.68 (B3LYP), R2 = 0.62 (M06–2X)) assays, and a slightly lower correlation in the ORAC assay (R2 = 0.54 (B3LYP), R2 = 0.52 (M06–2X)). PA demonstrated excellent correlation in both the ORAC (R2 = 0.94 (B3LYP), R2 = 0.57 (M06–2X)) and DPPH (R2 = 0.72 (B3LYP), R2 = 0.13 (M06–2X)) assays. The greatest difference was observed between the two calculation methods for determining PA values.

Figure 12.

Correlation between the experimental radical scavenging activity and the indicated physical properties of the hydrazones (B3LYP – blue, M06–2X -red). (a) Activity in ABTS assay as a function of bond dissociation energy (BDE), (b) Activity in ORAC assay as a function of BDE, (c) Activity in DPPH assay as a function of BDE; (d) Activity in ABTS assay as a function of HOMO energy, (e) Activity in ORAC assay as a function of HOMO energy, (f) Activity in DPPH assay as a function of HOMO energy, (g) Activity in ABTS assay as a function of LUMO energy, (h) Activity in ORAC assay as a function of LUMO energy, (i) Activity in DPPH assay as a function of LUMO energy, (j) Activity in ABTS assay as a function of ionization potential (IP), (k) Activity in ORAC assay as a function of IP, (l) Activity in DPPH assay as a function of IP, (m) Activity in ABTS assay as a function of proton affinity (PA), (n) Activity in ORAC assay as a function of PA, (o) Activity in DPPH assay as a function of PA.

The energies of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) also significantly correlated with antioxidant activities. HOMO exhibited the strongest correlation in the DPPH assay (R2 = 0.82 (B3LYP), R2 = 0.65 (M06–2X)), with slightly lower correlations in the ABTS (R2 = 0.67 (B3LYP), R2 = 0.67 (M06–2X)) and ORAC (R2 = 0.68 (B3LYP), R2 = 0.53 (M06–2X)) assays. Meanwhile, LUMO showed the highest correlation in the ORAC assay (R2 = 0.9 (B3LYP), R2 = 0.80 (M06–2X)) and maintained good correlation in the DPPH assay (R2 = 0.72 (B3LYP), R2 = 0.58 (M06–2X)). Although these analyses were conducted on a small sample size, they suggest directions for further investigation.

The analysis of the data in Tables 1 and 2 clearly showed that compound 5, a compound that emerged with the best overall performance from the study, exhibited parameters that position this compound in the high activity region in all of the meaningful activity-physicochemical variable relationships (Figure 11). For example, its BDE (73.58 kcal/mol) was in line with the highest activities in Figure 11 (b) and (c), same was true for the HOMO energy (0.1889 hartree, Figure 12 (d), (e) and (f)), LUMO energy (−0.0509 hartree, Figure 12 (h) and (i)), proton affinity (PA, 339.32 kcal/mol, Figure 12 (n) and (o)) and ionization potential (146.83 kcal/mol, Figure 11 (k) and (l)). These positive correlations indicated that the theory was very much in line with the experimental observations that described the antioxidant activity. Based on similar studies we have conducted on hydrazones,30 as well as on phenols, thiophenols and anilines30 it appeared that a selected group of physicochemical descriptors provided a meaningful tool for predicting antioxidant activity of these compounds. It must be mentioned, however, that compound 5 was the best in the studied series only, in addition to showing strong drug like properties, such as high GI absorption, zero Lipinksi-, Ghose-, Veber-, Egan-, and Muegge-violations and zero PAINS alerts, and a relatively modest 2.65 synthetic accessibility score, indicating straightforward synthesis. Thus, these observations could be highly supportive in designing a broad SAR study using compound 5 as a lead compound and using the above physicochemical properties in the iterative design.

To validate the above used DFT methods we have assessed our results obtained with B3LYP and M06–2X approaches by comparing four out of the eight lead compounds to their ab initio BDE, PA, IP, and HOMO, LUMO values. For this validation, we selected the Domain-Based Local Pair Natural Orbital CCSD(T) for single point calculations on the geometries obtained using the M06–2X/6–311++G(d,p), based on prior benchmark studies on antioxidant DFT methods.60–62 Since H has only one electron, Hartree–Fock (HF) was considered as exact solution (−0.49980 hartree), and for H+, since has no electron, the total electronic energy was considered as zero. The chosen four compounds were 1, 3, 4, and 5. Table 1 below includes data compared in our analysis. The mean absolute deviation (MAD) was calculated for all analyzed descriptors according to the following equation.

| (1) |

The comparisons and summary of the MAD results for B3LYP and M06–2X are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Comparison of the two DFT functionals (B3LYP (green) and M06–2X (magenta)) and the reference data collected with DLPNO–CCSD(T) DEF2-TZVPP DEF2-TZVPP/C//M062X//6–311++(d,p).

When comparing our results to the benchmark study by de Souza et al.,60 we found strong agreement (Table S3). The M06–2X method exhibited better overall alignment with ab initio results compared to B3LYP. In terms of trend analysis within our calculations, both B3LYP and M06–2X methods show good alignment with the CCSD(T) trends in most cases. The detailed trends are presented in Figure S105.

CONCLUSIONS

A broad variety of structurally diverse hydrazone derivatives were designed and synthesized to alleviate oxidative stress in trophoblast cells exposed to hydrogen peroxide—an in vitro model of preeclampsia–via potential mitochondrial antioxidant therapy. The compounds represented hydrazones with a variety of electron withdrawing and donating groups in the diaryl hydrazone skeleton, and larger derivatives with more extended delocalized electron structures. The compounds were evaluated in a diverse selection of assays, including antioxidant assays to determine in vitro activity, as well as in cell biology assays to assess the effect of the compounds on human trophoblast cells exposed to oxidative stress. Based on the experimental results, compound 5 showed the best overall results in the biochemical as well as cell-based assays and emerged as a lead compound. The computational analysis was also in agreement with the experimental data. In addition, the in silico prediction of the pharmacokinetic properties of the compounds revealed that compound 5 possesses highly desirable molecular descriptors that suggest that the compound would be able to reach the site of action, in contrast to natural antioxidants, vitamins C and E, that have been tested for antioxidant therapy. It has a nearly ideal lipophilicity (e.g., logP = 4); significantly higher than that of Vitamin C (logP = −2) that is completely water-soluble, that would enable compound 5 to pass through cell membranes. At the same time, it is partially soluble in water, unlike vitamin E (logP = 12) that is completely insoluble in aqueous medium. Pretreatment with this compound reduced mitochondrial-derived ROS production in H2O2-exposed trophoblasts cells (HTR8) confirming its mode of action and more importantly reduced sFLT-1 expression which is a key element among biomarkers of PE development. These key data suggest the potential of hydrazones in antioxidant therapy which may have future implications in preeclampsia and hypertensive disorders, which remains to be confirmed in in vivo studies.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and General Procedures.

The aldehydes and hydrazine derivatives, the NMR reference compounds, were all acquired from Aldrich. NMR solvents, including DMSO-d6 and CDCl3 (99.8%), were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich and Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. Additional materials and supplies were acquired from Fisher Scientific and Oakwood Chemical.

GC-MS measurements were conducted using an Agilent 6850 gas chromatograph coupled to an Agilent 5973 mass spectrometer system, operating with 70 eV electron impact ionization and equipped with a 30 m DB-5 column (J&W Scientific). The HRMS data were collected using an Agilent 7250 GC-QTOF mass spectrometer, also in electron impact ionization (EI, 70 eV) mode.

The 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz Agilent MM2 NMR spectrometer using DMSO-d6 and CDCl3 as solvents. Tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as internal standards, or the residual solvent signal served as a reference. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm. The following abbreviations are used to denote signal multiplicity in 1H NMR spectra: s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), and m (multiplet). All measurements were conducted at 25 °C with a temperature accuracy of ± 1 °C.

According to the ACS Ethical Guidelines, we confirm that this work does not include animal or human studies.

Synthesis and Characterization.

Synthesis of the Hydrazones – General Procedure.

During the synthesis our earlier procedure was followed.33 In a 15 mL round-bottom flask, 1 mmol of substituted benzaldehyde and 1 mmol of phenylhydrazine were dissolved in 2 mL of dichloromethane (DCM). The reaction mixture was allowed to stay at room temperature for 10 min then was cooled down to – 20 °C for 30 min. By the end of the cooling period, the hydrazone began to precipitate from the mixture. The crystalline product was filtered and dried at ambient temperature. The products were purified by recrystallization or preparative TLC to obtain sufficient purity, which was verified using GC–MS, and NMR. Depending on the structure of the products (mono vs dihydrazones) either substituted benzaldehydes (Method 1) or terephthaldehyde (Method 2) was used for the synthesis.

Synthesis of 3-(1-(2-Phenylhydrazineylidene)ethyl)aniline (9), 1-(1-(4-Chlorophenyl) ethylidene)-2-phenylhydrazine (10), 1-Phenyl-2-(1-(p-tolyl)ethylidene)hydrazine (15) (Method 1).

To synthesize the acetophenone based hydrazone derivatives, weigh the aldehyde (1 mmol) and sodium acetate (NaCOOCH3, 1.5 mmol) into a microwave reaction tube with a stir bar. Add 2 mL of ethanol, and then introduce phenylhydrazine (1.5 mmol) dropwise. Seal the tube and run the reaction at 200 W and 80 °C for 15 min while stirring. After cooling to room temperature, evaporate the ethanol using a rotary evaporator. Add 10 mL of diethyl ether to the residue, stir briefly, and filter to remove sodium acetate. Concentrate the filtrate by evaporating the diethyl ether to obtain the crude product, which can be characterized by GC-MS and, if necessary, recrystallized from an ethanol/water mixture.

Synthesis of the 1,4-Bis((E)-(2-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-hydrazinylidene)-methyl)benzene (16) (Method 2).

Terepthaldehyde (0.67 g, 0.5 mmol; 0.13 mL) and 4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-hydrazine (0.176 g, 1 mmol) were mixed in 2 mL of DCM. After 30 min at RT and 30 min at – 20 °C the product hydrazone was isolated by filtration and purified by preparative TLC.

Computational Methods.

Density functional theory has been employed to understand the electronic structure of hydrazones. All calculations were carried out at B3LYP58 as well as M06–2X level of theories and 6–311++G(d,p) basis set using Gaussian 09 program suite.56 These methods were selected based on recent literature.54 B3LYP, a widely used method for these systems, allows for comparison with previous studies. While it tends to underestimate energies, it reliably preserves reactivity trends when using the same basis set. Meanwhile, Minnesota functionals are gaining prominence due to their strong performance in thermochemistry and calculating reaction energies involving free radicals.

To find the conformational ensemble, ORCA 6.059,62 Global Optimizer Algorithm (GOAT) was applied. Frequency calculations were performed at the same level of theory to confirm the minima on potential energy surfaces. The radical or cationic electronic structures were calculated using the Kohn–Sham formalism with unrestricted spin DFT/UB3LYP. Key thermochemical indices such as bond dissociation energy (BDE), ionization potential (IP), and proton affinity (PA) values were determined (eqs 2–4).

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Additionally, further physicochemical and quantum parameters were predicted, including the N–H distance, dipole moment, logP value, and the energies of the HOMO and LUMO orbitals, as well as their gap energy, to explore possible correlations with experimental scavenging activity.

Statistical Analysis.

The activity values shown in Figure 6, 7, 8 were measured four times for the DPPH assay, three times for the ABTS assay and three times for ORAC assay. All data points were included in the statistical analysis. The data in Figure 6, 7, 8 are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

The Python programming language was used to develop the code for both regression analysis and visualization. The code is publicly available on GitHub at https://github.com/curve-fit/curvefit.git under the repository named curvefit, maintained by BernadetteVlo.

Regression analysis was performed using the method of least squares, and the quality of the fit was assessed using the coefficient of determination (R2), calculated as shown in eq 5:

| (5) |

Where:

RSS: Residual Sum of Squares

TSS: Total Sum of Squares

This approach ensures accurate fitting and provides a quantitative measure of how well the model explains the observed data.

Compound Characterization.

The methods described above were applied to synthesize of all other hydrazones. The structure of the molecules was confirmed by using mass spectrometry and 1H, 19F, and 13C NMR spectroscopy. All compounds were >95% pure by GC and/or HPLC analysis. The spectra are displayed in the Supporting Information. Several organofluorine hydrazones can be found in the literature, and their NMR data including 19F NMR were in agreement with the earlier spectra.33,47

(E)-1-((perf luorophenyl)methylene)-2-(4-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)hydrazine (1).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm) = 8.08 (s, 1H), 7.74 (s, 1H), 7. 54–7.52 (d, 2H, J= 8 Hz), 7.17–7.14 (d, 2H, J = 12 Hz); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm) = 146.13, 146.01–145.90 (m), 143.58–143.35 (m), 141.97, 139.42–139.20 (m), 136.89–136.61 (m), 128.66–120.57 (q, J = 268.5 Hz), 126.98–126.86 (q, J = 4 Hz), 125.63–125.60 (q, J = 3 Hz), 123.63–122.66 (q, J = 32 Hz), 112.76, 110.30–110.26 (m); 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): −61.56, −142.82–142.90, −154.27–154.38, −162.23–162.36; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C14H6F8N2: 354.0403; found: 354.0382.

(E)-N,N-dimethyl-4-((2-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)hydrazono)-methyl)aniline (2).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm) = 10.45 (s, 1H), 7.84 (s, 1H), 7.50–7.49 (m, 4H), 7.13–7.11 (d, 2H), 6.73–6.71 (d, 2H), 2.93 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm) = 151.05, 149.08, 140.61, 129.63–121.56 (q, J = 269 Hz), 127.70, 126.83–126.79 (q, J = 4 Hz), 123.31, 118.38–117.43 (q, J = 32 Hz), 112.39, 111.58, 40.23; 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): −59.16; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C16H16F3N3 307.1296; found: 307.1287.

(E)-5-methoxy-2-((2-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)hydrazono)-methyl)phenol (3).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.66 (s, 1H), 10.50 (s, 1H), 8.17 (d, 1H), 7.53–7.50 (m, 3H), 7.06–7.04 (m, 2H), 6.50–6.46 (m, 2H), 3.74 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 161.38, 157.83, 148.35, 139.89, 128.93, 129.49–121.42 (q, J = 269 Hz), 127.01–126.94 (q, J = 4 Hz), 119.02–118.07 (q, J = 32 Hz), 113.81, 111.55, 106.63, 101.44, 55.53; 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): −59.32; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C15H13F3N2O2 310.0929; found: 310.0927.

(E)-1-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-(trifluoromethyl)benzylidene)-hydrazine (4).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm) = 10.77 (s, 1H), 8.19 (s, 1H), 7.50–7.28 (m, 4H), 7.08–6.97 (m, 3H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 3.77 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm) = 152.71, 146.70, 145.87, 133.76, 130.22, 130.58–129.64 (q, J = 32 Hz), 128.72, 124.29, 128.48–120.35 (q, J = 271 Hz), 116.52, 115.62, 114.70–114.66 (q, J = 4 Hz), 112.54, 107.66–107.62 (q, J = 4 Hz), 60.90, 55.63; 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): −61.46; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C16H15F3N2O2 324.1085; found: 324.1091.

(E)-N,N-dimethyl-4-((2-(3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-hydrazinylidene)methyl)aniline (5).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.42 (s, 1H), 7.80 (s, 1H), 7.48–7.45 (m, 4H), 7.09- 7.07 (d, 2H), 6.71–6.69 (d, 2H), 2.91 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 150.66, 149.46, 139.68, 130.54–129.61 (q, J = 32 Hz), 130.15, 128.65–120.52 (q, J = 271 Hz), 127.28, 123.10, 115.30, 113.86–113.82 (q, J = 4 Hz), 112.10, 107.41–107.37 (q, J = 4 Hz), 39.93; 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): −61.43; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C16H16F3N3 307.1296; found: 307.1292.

(E)-N,N-dimethyl-4-((2-(2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-hydrazinylidene)methyl)aniline (6).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.37 (s, 1H), 8.25 (s, 1H), 7.75–7.73 (d, 1H), 7.52–7.50 (m, 4H), 6.87–6.83 (t, 1H), 6.74–6.72 (d, 2H), 2.93 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 150.77, 142.99, 142.63, 133.46, 128.75–120.63 (q, J = 271 Hz), 127.46, 126.12–125.96 (q, J = 5 Hz), 122.93, 117.61, 114.39, 112.01, 110.97–110.08 (q, J = 120 Hz), 39.85; 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): −59.98; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C16H16F3N3 307.1296; found: 307.1274.

(E)-1-(4-nitrobenzylidene)-2-(3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-hydrazine (7).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) = 11.16 (s, 1H), 8.25–8.23 (d, 2H), 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.94–7.91 (d, 2H), 7.50–7.46 (t, 1H), 7.39–7.37 (m, 2H), 7.15–7.13 (d, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm) = 146.90, 145.58, 142.39, 136.08, 130.86, 130.68–130.37 (q, J = 32 Hz), 126.97, 124.53, 126.08–123.37 (q, J = 271 Hz), 116.66, 116.28–116.24 (q, J = 4 Hz), 108.71–108.67 (q, J = 4 Hz); 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): −61.39; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C14H10F3N3O2 309.0725; found: 309.0656.

(E)-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-(4-nitrobenzylidene)hydrazine (8).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.76 (s, 1H), 8.21–8.18 (m, 2H), 7.86–7.81 (m, 3H), 7.10–7.07 (d, 2H), 6.89–6.6.88 (d, 2H), 3.70 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 153.88, 146.07, 143.37, 138.73, 132.67, 126.09, 124.52, 115.15, 114.06, 55.70; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C14H13N3O3 271.0956; found: 271.0948.

(E)-3-(1-(2-phenylhydrazinylidene)ethyl)aniline (9).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.14 (s, 1H), 7.24–7.19 (m, 4H), 7.08 (s, 1H), 7.04–7.01 (t, 1H), 6.93–6.91 (d, 1H), 6.76–6.73 (t, 1H), 6.53–6.51 (d, 1H), 5.08 (s, 2H), 2.18 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 148.48, 146.29, 141.27, 139.89, 128.87, 128.67, 118.65, 113.66, 113.46, 112.75, 110.70, 13.00; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C14H15N3 225.1266; found: 225.1267.

(E)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)ethylidene)-2-phenylhydrazine (10).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.35 (s, 1H), 7.80–7.78 (d, 2H), 7.42–7.40 (d, 2H), 7.24 (m, 4H), 6.77 (s, 1H), 2.23 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 145.89, 139.17, 138.08, 131.99, 128.93, 128.23, 126.78, 119.05, 112.87, 12.66; 19F NMR (282 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): −59.81; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C14H13ClN2 244.0767; found: 244.0770.

(E)-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-(1-(4-nitrophenyl)ethylidene)hydrazine (11).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.54 (s, 1H), 8.20–8.18 (d, 2H), 7.99–7.97 (d, 2H), 7.24–7.22 (d, 2H), 6.87–6.85 (d, 2H), 3.69 (s, 3H), 2.25 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 153.80, 146.13, 146.11, 139.63, 137.05, 125.87, 124.07, 114.91, 114.73, 55.66, 12.82; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C15H15N3O3 285.1113; found: 285.1102.

(E)-(2,5-dimethylphenyl)-2-(1-(3-nitrophenyl)ethylidene)-hydrazine (12).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 8.53 (s, 1H), 8.26–8.24 (d, 1H), 8.18 (s, 1H), 8.16–8.14 (d, 1H), 7.71–7.67 (t, 1H), 7.30 (s, 1H), 6.99–6.97 (d, 1H), 6.62–6.60 (d, 1H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 2.28 (s, 3H). 2.25 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 148.25, 142.93, 140.93, 140.39, 135.73, 131.53, 130.46, 130.07, 122.13, 120.90, 119.78, 119.42, 114.20, 21.31, 16.88, 12.51.; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C16H17N3O2 283.1320; found: 283.1307.

(E)-5-methoxy-2-(1-(2-phenylhydrazinylidene)ethyl)phenol (13).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.92 (s, 1H), 10.21 (s, 1H), 8.06 (s, 1H), 7.40–7.38 (d, 1H), 7.23–7.19 (m, 2H), 6.91-6.89 (m, 2H), 6.74–6.71 (t, 1H), 6.47–6.45 (m, 2H), 3.73 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 160.91, 157.87, 145.36, 138.79, 129.70, 129.20, 119.05, 113.89, 111.93, 106.44, 101.49, 55.59; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C14H14N2O2 242.1055; found: 242.1049.

(E)-(2,5-dimethylphenyl)-2-(1-(4-nitrophenyl)ethylidene)-hydrazine (14).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 8.32 (s, 1H), 8.25–8.23 (d, 2H), 8.06–8.04 (d, 2H), 7.33 (s, 1H), 7.00–6.99 (d, 1H), 6.64–6.62 (d, 1H), 2.35 (s, 3H), 2.28 (s, 3H), 2.25 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 146.63, 145.81, 142.98, 140.47, 136.16, 130.82, 126.38, 124.13, 121.60, 120.31, 114.78, 21.61, 17.18, 12.63.; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C16H17N3O2 283.1320; found: 283.1316.

(E)-1-phenyl-2-(1-(p-tolyl)ethylidene)hydrazine (15).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.22 (s, 1H), 7.70–7.68 (m, 2H), 7.25–7.17 (m, 6H), 6.75 (m, 1H), 2.30 (s, 3H), 2.23 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 146.23, 140.59, 136.79, 136.54, 128.88, 125.10, 118.70, 112.76, 20.76, 12.81; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C15H16N2 224.1313; found: 224.1315.

1,4-Bis((E)-(2-(3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)hydrazinylidene)-methyl)benzene (16).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.86 (s, 2NH), 7.95 (s, 2H), 7.69 (m, 4H), 7.45–7.41 (t, 2H), 7.37 (s, 2H), 7.34–7.32 (d, 2H), 7.05–7.03 (d, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 146.21, 138.33, 135.71, 130.61, 130.95–130.01 (q, J = 32 Hz), 126.65, 128.89–120.75 (q, J= 271 Hz), 116.10, 115.17–115.13 (q, J = 4 Hz), 108.22–108.19 (q, J = 4 Hz); 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): −61.44; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C22H16F6N4 450.1279; found: 450.1254.

1,4-Bis((E)-(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)hydrazinylidene)methyl)benzene (17).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.16 (s, 2H), 7.77 (d, 2H), 7.58 (m, 4H), 7.01- 6.99 (d, 4H), 6.84–6.82 (d, 4H), 3.68 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 153.07, 139.69, 135.67, 135.48, 126.05, 115.09, 113.43, 55.69; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C22H22N4O2 374.1742; founds: 374.1740.

1,4-Bis((E)-(2-(3-nitrophenyl)hydrazinylidene)methyl)benzene (18).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.94 (s, NH), 7.97 (s, 2H), 7.87 (s, 2H), 7.75 (s, 4H), 7.61–7.59 (d, 2H), 7.54–7.46 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 148.85, 146.28, 138.65, 135.27, 130.51, 126.42, 118.27, 113.01, 105.70; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C20H16N6O4 404.1233; found: 404.1732.

(E)-3-(1-(2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)hydrazinylidene)ethyl)-7-methoxy-2H-chromen-2-one (19).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 8.72 (s, 1H), 8.18 (s, 1H), 7.76–7.74 (d, 1H), 7.57–7.51 (q, 1H), 7.25–7.20 (t, 1H), 7.02–6.96 (m, 3H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 2.24 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 162.53, 159.66, 156.67–156.56 (d, J = 236 Hz), 155.13, 150.72–150.60 (d, J = 244 Hz), 143.65, 140.45, 130.91–130.84 (J = 7 Hz), 130.06, 123.48, 116.24–116.10 (d, J = 9 Hz), 112.77, 112.67, 111.31–111.06 (d, J = 21.5 Hz), 104.11–103.61 (d, J = 27.5 Hz), 100.26, 55.99, 15.21; 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): −122.61–122.67, −127.59–127.65; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C18H14F2N2O3 344.0972; found: 344.0996.

(E)-7-methoxy-3-(1-(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)hydrazinylidene)ethyl)-2H-chromen-2-one (20).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.21 (s, 1H), 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.75–7.73 (d, 1H), 7.18–7.16 (d, 2H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.97–6.94 (d, 1H), 6.83–6.80 (d, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.68 (s, 3H), 2.17 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 162.60, 160.33, 155.28, 140.19, 139.68, 138.25, 130.24, 124.35, 114.70, 114.50, 113.31, 113.07, 100.63, 56.38, 55.63, 15.56; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C19H18N2O4 338.1266; found: 338.1262.

(E)-1-(naphthalen-2-ylmethylene)-2-(3-nitrobenzyl)hydrazine (21).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.95 (s, 1H), 8.09 (s, 1H), 8.03–7.99 (m, 2H), 7.93- 7.87 (m, 4H), 7.58–7.49 (m, 5H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 149.29, 146.79, 139.59, 133.53, 133.52, 133.32, 130.94, 128.81, 128.44, 128.19, 127.28, 127.08, 126.89, 122.84, 118.70, 113.39, 106.10; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C17H13N3O2 291.1007; found: 291.0994.

(E)-1-(anthracen-9-ylmethylene)-2-(2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)hydrazine (22).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.13 (s, 1H), 9.64 (s, 1H), 8.82–8.79 (d, 2H), 8.63 (s, 1H), 8.13–8.11 (d, 2H), 7.77–7.75 (d, 1H), 7.65–7.54 (m, 6H), 6.98–6.94 (t, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 142.50, 140.66, 133.88, 131.09, 129.34, 128.96, 128.43, 126.80, 128.70–120.57 (q, J = 271 Hz), 126.37–126.26 (q, J = 6 Hz), 126.24, 125.47, 125.08, 118.75, 114.32, 111.51–110.61 (q, J = 30 Hz); 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): −59.81; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C22H15F3N2 364.1187; found: 364.1178.

(E)-1-(naphthalen-2-ylmethylene)-2-phenylhydrazine (23).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.46 (s, 1H), 8.01–7.88 (m, 6H), 7.53–7.46 (q, 2H), 7.25–7.21 (t, 2H), 7.12–7.10 (d, 2H), 6.77–6.74 (t, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 145.23, 136.45, 133.64, 133.22, 132.80 129.17, 128.22, 127.86, 127.72, 126.54, 126.08, 125.80, 122.50, 118.85, 112.05; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C17H14N2 246.1157; found: 246.1142.

(E)-1-(2,5-dimethylphenyl)-2-(naphthalen-2-ylmethylene)hydrazine (24).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.62 (s, 1H), 8.29 (s, 1H), 8.02–7.88 (m, 5H), 7.53–7.46 (q, 2H), 7.32 (s, 1H), 6.94–6.92 (d, 1H), 6.54–6.52 (d, 1H), 2.28 (s, 3H), 2.19 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 143.29, 138.32, 136.13, 134.17, 133.66, 133.28, 130.69, 128.70, 128.32, 128.15, 126.95, 126.52, 126.30, 122.96, 120.09, 118.21, 113.14, 21.67, 17.59; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C19H18N2 274.1470; found: 274.1455.

(E)-1-(naphthalen-2-ylmethylene)-2-(3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)hydrazine (25).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 11.02 (s, 1H), 9.10 (s, 1H), 8.68–8.66 (d, 2H), 8.63 (s, 1H), 8.14–8.11 (d, 2H), 7.62–7.53 (m, 4H), 7.50–7.46 (t, 1H), 7.35–7.33 (m, 2H), 7.10–7.08 (d, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 145.85, 138.43, 133.13–133.11 (q, J = 2 Hz), 133.04, 130.53–129.60 (q, J = 31 Hz), 130.28, 128.34, 128.49–120.36 (q, J = 271 Hz), 127.97, 127.75, 126.60, 126.34, 122.46, 115.72, 114.80–114.76 (q, J = 4 Hz), 107.82–107.74 (q, J = 4 Hz); 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): −61.39; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C22H15F3N2 364.1187; found: 364.1190.

(E)-1-(anthracen-9-ylmethylene)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)hydrazine (26).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 11.61 (s, 1H), 9.25 (s, 1H), 8.69–8.67 (m, 3H), 8.19–8.13 (two d, 4H), 7.66–7.55 (two t, 4H), 7.22–7.20 (d, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 150.51, 140.66, 138.57, 131.02, 129.38, 129.04, 128.94, 127.09, 126.36, 125.51, 124.75, 111.27; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C21H15N3O2 341.1164; found: 341.1166.

(E)-1-(anthracen-9-ylmethylene)-2-(2-nitrophenyl)hydrazine (27).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 11.64 (s, 1H), 9.74 (s, 1H), 8.83–8.81 (d, 2H), 8.68 (s, 1H), 8.17–8.13 (m, 3H), 7.93–7.90 (d, 1H), 7.68–7.55 (m, 5H), 6.96- 6.94 (t, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 144.70, 141.82, 137.07, 131.45, 131.25, 130.01, 129.63, 129.41, 127.49, 126.29, 126.14, 125.98, 125.54, 118.83, 116.16; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C21H15N3O2 341.1164; found: 341.1153.

(E)-3-((2-phenylhydrazineylidene)methyl)-1H-indole (28).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 11.37 (s, 1H), 9.86 (s, 1H), 8.33 (s, 1H), 8.17 (s, 1H), 7.65 (s, 1H), 7.45 (s, 1H), 7.25–7.22 (m, 4H), 7.11–7.09 (m, 2H), 6.71 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 146.24, 137.07, 134.99, 129.15, 127.33, 124.31, 122.33, 121.73, 120.07, 117.57, 112.88, 111.74, 111.44; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C15H13N3 235.1109; found: 235.1102.

(E)-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-(naphthalen-2-ylmethylene)hydrazine (29).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.27 (s, 1H), 7.98–7.89 (m, 6H), 7.52–7.45 (q, 2H), 7.08–7.05 (d, 2H), 6.87–6.85 (d, 2H), 3.70 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 153.12, 139.71, 135.70, 134.31, 133.69, 133.07, 128.58, 128.19, 128.12, 126.92, 126.32, 125.74, 122.90, 115.10, 113.49, 55.70; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C18H16N2O 276.1262; found: 276.1248.

(E)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-(naphthalen-2-ylmethylene)hydrazine (30).

1H NMR (399.822 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.58 (s, 1H), 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.96–7.95 (m, 2H), 7.90–7.86 (t, 3H), 7.51–7.44 (q, 2H), 7.25–7.23 (d, 2H), 7.10–7.08 (d, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 144.59, 137.78, 133.78, 133.59, 133.32, 129.39, 128.67, 128.33, 128.15, 127.00, 126.63, 126.55, 122.91, 122.47, 113.90; HRMS (EI): m/z: [M+] calcd. for C17H13ClN2 280.0767; found: 280.0756.

Biochemistry - Radical Scavenging Assays.

The radical scavenging assays have been carried out as described in our earlier publication [30].

2.6.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay.

The DPPH assay was conducted following earlier procedures.30 A VersaMax UV–vis plate reader with the SoftMax Pro 5 software (Molecular Devices) were used to determine the scavenging of the DPPH radical by the compounds investigated in comparison to the reference compound Trolox. The data was processed using eq 6 below where Absc is the absorbance of the control and Abst is the absorbance of the test sample.

| (6) |

The 60 min percent radical scavenging values were standardized against the 60 min Trolox percent radical scavenging value to obtain the final Trolox equivalent values for each compound as shown below (eq 7).

| (7) |

ABTS Radical Scavenging Assay.

Following an earlier procedure, the ABTS assay was carried out to determine the radical scavenging activity of these hydrazones.30 The ABTS radical was generated 12 to 24 h before the assay and a VersaMax UV–vis plate reader with the SoftMax Pro 5 software (Molecular Devices) were used to assess the scavenging of the ABTS radical by the compounds. The data was processed using eq 5.

Similarly to the DPPH assay, Trolox was used as a reference antioxidant and the radical scavenging values were standardized against Trolox percent radical scavenging value to obtain the final Trolox equivalents values for each compound using eq 6.

ORAC Radical Scavenging Assay.

A SpectraMax i3x UV–Vis/fluorescence plate reader was used for these assays with the SoftMax Pro 5 software (Molecular Devices) as described earlier.30 The data was processed using the equations below (eqs 8 and 9), the parameters are described below.

| (8) |

fi is the fluorescence intensity at reading 0–29. f0 is the fluorescence at reading zero. f30 is the fluorescence at time 30.

| (9) |

The Net AUCc is the net area under the curve for the control sets with AAPH and fluorescein with the appropriate amount of DMSO in ethanol. The Net AUCt is the area under the curve for the test sample while the Net AUCf_max is the area under the curve for the maximum fluorescence sample where no AAPH was added. A Trolox dilution curve was used for standardization to obtain the Trolox equivalent concentration for each compound, similarly to the above assays.

The percent radical scavenging values of different concentrations of Trolox (100 μM, 50 μM, 25 μM, 12.5 μM, 6.25 μM, and 3.125 μM) calculated using eq 4 were plotted versus the natural logarithm of the Trolox concentration values. A calibration curve was constructed using those plotted values.63 The following equation (eq 10) was used to calculate the Trolox Equivalent Concentration of the samples.

(eq 9)b (constant) and m (coefficient) are from the trendline equation, y = m(ln(x))+b (x: Trolox concentration, y: Percent Radical ScavengingTrolox).

Biological Evaluation.

Hydrazone Treatment to Reduce Oxidative Stress in Trophoblast Cells.

Human trophoblast HTR-8/SVneo cells were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells in the H2O2-treated (“Control”) group were treated with 0.1–50 μM H2O2 alone. Cells in the hydrazone + H2O2-treated (“Treated”) groups were pretreated with 0.1–50 μM HMP for 30 min, respectively, and then they were treated with 100 μM H2O2 for 20 h including hydrazones in the cell culture media for the entire time. Cell culture supernatants were collected at the end of the experiment and stored at −20 °C until assayed.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA).

Soluble FLT-1 (sFLT-1) in culture medium was measured by ELISA using the human VEGF receptor 1 (VEGFR1) Quantikine kit (R&D Systems) following manufacturer’s instructions. This assay has an intra-assay assay coefficient of variation of 2.6 – 3.8% and an interassay coefficient of variation of 5.5 – 9.8%.52

MitoSOX Red Immunofluorescence Assay.

Immunofluorescence assay was carried out to determine the mitochondrial-derived superoxide production in HTR-8/SVneo cells as described earlier.61 The images were produced from fluorescence microscopy for MitoSOX Red, with an original magnification of 20× using ImageJ software v. 1.53t (National Institute of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD, USA; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij).

Supplementary Material

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5c00010.

Detailed description of the experimental data, including synthesis, biochemical, biological assays, computational details and data, compound characterization (HRMS and NMR spectra); all experimental antioxidant activity vs physicochemical parameter plots (PDF)

Molecular formula strings and all experimental antioxidant and cell biology data (CSV)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial supports provided by the American Heart Association through grant 20AIREA35120469 (B.T.) and National Institute of Health through grant 1R15HD110945-01A1 (M.T.) are gratefully acknowledged. The authors are also grateful for the use of the supercomputing facilities managed by the Research Computing Department at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- BDE

Bond dissociation energy

- DP

Dipole moment

- HF

Hartree–Fock

- HOMO

Highest occupied molecular orbital

- IP

Ionization potential

- LUMO

Lowest unoccupied molecular orbital

- PA

Proton affinity

- logP

Partition coefficient

- PE

Preeclampsia

- sFLT-1

Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1

Footnotes

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5c00010

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Maxim Mastyugin, Department of Chemistry, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, Massachusetts 02125, United States.

R. Bernadett Vlocskó, Department of Chemistry, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, Massachusetts 02125, United States.

Zsuzsanna K. Zsengellér, Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, United States; Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, United States

Béla Török, Department of Chemistry, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, Massachusetts 02125, United States.

Marianna Török, Department of Chemistry, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, Massachusetts 02125, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).American Coll. Gynecologists, Task Force on Hypertension in PE. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013, 122, 1122–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Mackay AP; Berg CJ; Atrash HK Pregnancy-related mortality from preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2001, 97, 533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3) (a).Burton GJ; Jauniaux E Placental oxidative stress: from miscarriage to preeclampsia. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig 2004, 11, 342–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chiarello DI; Abad C; Rojas D; Toledo F; Vázquez CM; Mate A; Sobrevia L; Marín R Oxidative stress: Normal pregnancy versus preeclampsia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis 2020, 1866, No. 165354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Haram K; Mortensen JH; Myking O; Magann EF; Morrison JC The role of oxidative stress, adhesion molecules and antioxidants in preeclampsia. Curr. Hypertens. Rev 2019, 15, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4) (a).Hubel CA Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med 1999, 222, 222–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Marín R; Chiarello DI; Abad C; Rojas D; Toledo F; Sobrevia L Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis 2020, 1866, No. 165961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Myatt L; Cui X Oxidative stress in the placenta. Histochem. Cell. Biol 2004, 122, 369–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5) (a).Ilekis JV; Tsilou E; Fisher S; Abrahams VM; Soares MJ; Cross JC; Zamudio S; Illsley NP; Myatt L; Colvis C; Costantine MM; Haas DH; Sadovsky Y; Weiner C; Rytting E; Bidwell G Placental origins of adverse pregnancy outcomes: potential molecular targets: an Executive Workshop Summary of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 2016, 215, S1–S46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Taravati A; Tohidi F Comprehensive analysis of oxidative stress markers and antioxidants status in preeclampsia. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol 2018, 57, 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Walsh SW Maternal-placental interactions of oxidative stress and antioxidants in preeclampsia. Semin. Reprod. Endocrinol 1998, 16, 93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6) (a).Lorzadeh N; Kazemirad Y; Kazemirad N Investigating the preventive effect of vitamins C and E on preeclampsia in nulliparous pregnant women. J. Perinat. Med 2020, 48, 625–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Roberts JM; et al. Vitamins C and E to prevent complications of pregnancy-associated hypertension. New Engl. J. Med 2010, 362, 1282–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stratta P; Canavese C; Porcu M; Dogliani M; Todros T; Garbo E; Belliardo F; Maina A; Marozio L; Zonca M Vitamin E supplementation in preeclampsia. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest 1994, 37, 246–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Foyer CH; Noctor G Redox homeostasis and antioxidant signaling: a metabolic interface between stress perception and physiological responses. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1866–1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Pizzino G; Irrera N; Cucinotta M; Pallio G; Mannino F; Arcoraci V; Squadrito F; Altavilla D; Bitto A; Victor VM Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longevity 2017, 8416763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Sharifi-Rad M; Anil Kumar NV; Zucca P; Varoni EM; Dini L; Panzarini E; Rajkovic J; Tsouh Fokou PV; Azzini E; Peluso I; Prakash Mishra A; Nigam M; El Rayess Y; Beyrouthy ME; Polito L; Iriti M; Martins N; Martorell M; Docea AO; Setzer WN; Calina D; Cho WC; Sharifi-Rad J Lifestyle, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Back and Forth in the Pathophysiology of Chronic Diseases. Frontiers in Physiol. 2020, 11, 694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10) (a).Valko M; Leibfritz D; Moncol J; Cronin MTD; Mazur M; Telser J Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 2007, 39, 44–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lin M; Beal MF Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 2006, 443, 787–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Teleanu RI; Chircov C; Grumezescu AM; Volceanov A; Teleanu DM Antioxidant Therapies for Neuroprotection—A Review. J. Clin. Med 2019, 8, 1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Aborode AT; Pustake M; Awuah WA; Alwerdani M; Shah P; Yarlagadda R; Ahmad S; Silva Correia IF; Chandra A; Nansubuga EP; Abdul-Rahman T; Mehta A; Ali O; Amaka SO; Zuñiga YMH; Shkodina AD; Inya OC; Shen B; Alexiou A; Hrncčić D Targeting Oxidative Stress Mechanisms to Treat Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease: A Critical Review. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev 2022, 7934442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Chang K-H; Chen C-M The Role of Oxidative Stress in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Zsengellér ZK; Rajakumar A; Hunter JT; Salahuddin S; Rana S; Stillman IE; Ananth Karumanchi S Trophoblast mitochondrial function is impaired in preeclampsia and correlates negatively with the expression of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2016, 6, 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Covarrubias AE; Lecarpentier E; Lo A; Salahuddin S; Gray KJ; Karumanchi SA; Zsengellér ZK AP39, a Modulator of Mitochondrial Bioenergetics, Reduces Antiangiogenic Response and Oxidative Stress in Hypoxia-Exposed Trophoblasts: Relevance for Preeclampsia Pathogenesis. Am. J. Pathol 2019, 189, 104–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Rajakumar A; Brandon HM; Daftary A; Ness R; Conrad KP Evidence for the functional activity of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors overexpressed in preeclamptic placentae. Placenta 2004, 25, 763–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Levine RJ; Lam C; Qian C; Yu KF; Maynard SE; Sachs BP; Sibai BM; Epstein FH; Romero R; Thadhani R; Karumanchi SA Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. New Engl. J. Med 2006, 355, 992–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Maynard SE; Min JY; Merchan J; Lim KH; Li J; Mondal S; Libermann TA; Morgan JP; Sellke FW; Stillman IE; Epstein FH; Sukhatme VP; Karumanchi SA Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J. Clin Invest 2003, 111, 649–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Roberts JM; Myatt L; Spong CY; Thom EA; Hauth JC; Leveno KJ; Pearson GD; Wapner RJ; Varner MW; Thorp JM Jr.; Mercer BM; Peaceman AM; Ramin SM; Carpenter MW; Samuels P; Sciscione A; Harper M; Smith WJ; Saade G; Sorokin Y; Anderson GB Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child H, Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units N. Vitamins C and E to prevent complications of pregnancy-associated hypertension. N Engl J. Med 2010, 362, 1282–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Vaka R; Deer E; LaMarca B Is Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress a Viable Therapeutic Target in Preeclampsia? Antioxidants 2022, 11, 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Sorriento D; De Luca N; Trimarco B; Iaccarino G The Antioxidant Therapy: New Insights in the Treatment of Hypertension. Frontiers in Physiol. 2018, 9, 258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yamada Y; Nakamura K; Abe J; Hyodo M; Haga S; Ozaki M; Harashima H Mitochondrial delivery of Coenzyme Q10 via systemic administration using a MITO-Porter prevents ischemia/reperfusion injury in the mouse liver. Journal of controlled release. J. Controlled Release Soc 2015, 213, 86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Mukhopadhyay P; Horváth B; Zsengeller Z; Bátkai S; Cao Z; Kechrid M; Holovac E; Erdėlyi K; Tanchian G; Liaudet L; Stillman IE; Joseph J; Kalyanaraman B; Pacher P Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation triggers inflammatory response and tissue injury associated with hepatic ischemia-reperfusion: therapeutic potential of mitochondrially targeted antioxidants. Free Radic Biol. Med 2012, 53, 1123–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Nuzzo AM; Camm EJ; Sferruzzi-Perri AN; Ashmore TJ; Yung HW; Cindrova-Davies T; Spiroski AM; Sutherland MR; Logan A; Austin-Williams S; Burton GJ; Rolfo A; Todros T; Murphy MP; Giussani DA Placental Adaptation to Early-Onset Hypoxic Pregnancy and Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant Therapy in a Rodent Model. Am. J. Pathol 2018, 188, 2704–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Vaka VR; McMaster KM; Cunningham MW Jr.; Ibrahim T; Hazlewood R; Usry N; Cornelius DC; Amaral LM; LaMarca B Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Reactive Oxygen Species in Mediating Hypertension in the Reduced Uterine Perfusion Pressure Rat Model of Preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2018, 72, 703–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Rossi L; Mazzitelli S; Arciello M; Capo CR; Rotilio G Benefits from dietary polyphenols for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Res 2008, 33, 2390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Delmas D; Aires V; Limagne E; Dutartre P; Mazue F; Ghiringhelli F; Latruffe N Transport, stability, and biological activity of resveratrol. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci 2011, 1215, 48–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Horton W; Török M, Natural and Nature-Inspired Synthetic Small Molecule Antioxidants in the Context of Green Chemistry. In Green Chemistry: An Inclusive Approach;1st ed.; Eds. Török B; Dransfield T; Elsevier, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Török B; Sood A; Bag S; Tulsan T; Ghosh S; Borkin D; Kennedy AR; Melanson M; Madden R; Zhou W; LeVine H III; Török M Diaryl Hydrazones as Multifunctional Inhibitors of Amyloid Self-Assembly. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 1137–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30) (a).Peerannawar S; Horton W; Kokel A; Török F; Török B; Török M Theoretical and Experimental Analysis of the Antioxidant Features of Diarylhydrazones. Struct. Chem 2017, 28, 391–402. [Google Scholar]; (b) Horton W; Peerannawar S; Török B; Török M Theoretical and experimental analysis of the antioxidant features of substituted phenol and aniline model compounds. Struct. Chem 2019, 30, 23–35. [Google Scholar]; (c) Vlocskó RB; Mastyugin M; Török B; Török M Correlation of Physicochemical Properties with Antioxidant Activity in Phenol and Thiophenol Analogues. Sci. Reports 2025, 15, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31) (a).Kareem HS; Ariffin A; Nordin N; Heidelberg T; Abdul-Aziz A; Kong KW; Yehye WA Correlation of antioxidant activities with theoretical studies for new hydrazone compounds bearing a 3, 4, 5-trimethoxy benzyl moiety. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2015, 103, 497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Carradori F; Ortuso A; Petzer D; Bagetta C. De; Monte D; Secci D. De; Vita P; Guglielmi G; Zengin A; Aktumsek S; Alcaro JPP Design, synthesis and biochemical evaluation of novel multi-target inhibitors as potential anti-Parkinson agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2018, 143, 1543–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32) (a).Rollas S; Ksüçükgüzel G Biological activities of hydrazone derivatives. Molecules 2007, 12, 1910–1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Domalaon R; Idowu T; Zhanel GG; Schweizer F Antibiotic Hybrids: the Next Generation of Agents and Adjuvants against Gram-Negative Pathogens? Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2018, 31, No. e00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Baldisserotto A; Demurtas M; Lampronti I; Moi D; Balboni G; Vertuani S; Manfredini S; Onnis V Benzofuran hydrazones as potential scaffold in the development of multifunctional drugs: Synthesis and evaluation of antioxidant, photoprotective and antiproliferative activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2018, 156, 118–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Baier A; Kokel A; Horton W; Gizińska E; Pandey G; Szyszka R; Torok B; Török M Organofluorine Hydrazone Derivatives as Multifunctional Anti-Alzheimer’s Agents with CK2 Inhibitory and Antioxidant Features. ChemMedChem. 2021, 16, 1927–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Zsengeller ZK; Mastyugin M; Lo A; Salahuddin S; Karumanchi A; Torok M; Torok B Organofluorine Hydrazones Preventing Oxidant Stress in an in vitro Model of Preeclampsia. Hypertension 2021, 78, AP236–AP236. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Charlton NC; Mastyugin M; Török B; Török M Structural Features of Small Molecule Antioxidants and Strategic Modifications to Improve Potential Bioactivity. Molecules 2023, 28, 1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Prakash Reddy V Organofluorine Compounds in Biology and Medicine; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Cambridge, MA, Oxford, 2015. [Google Scholar]