Conspectus

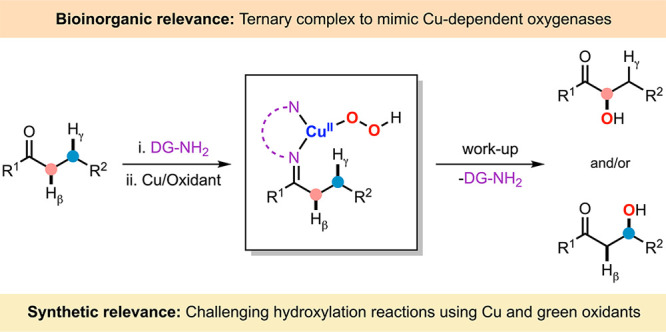

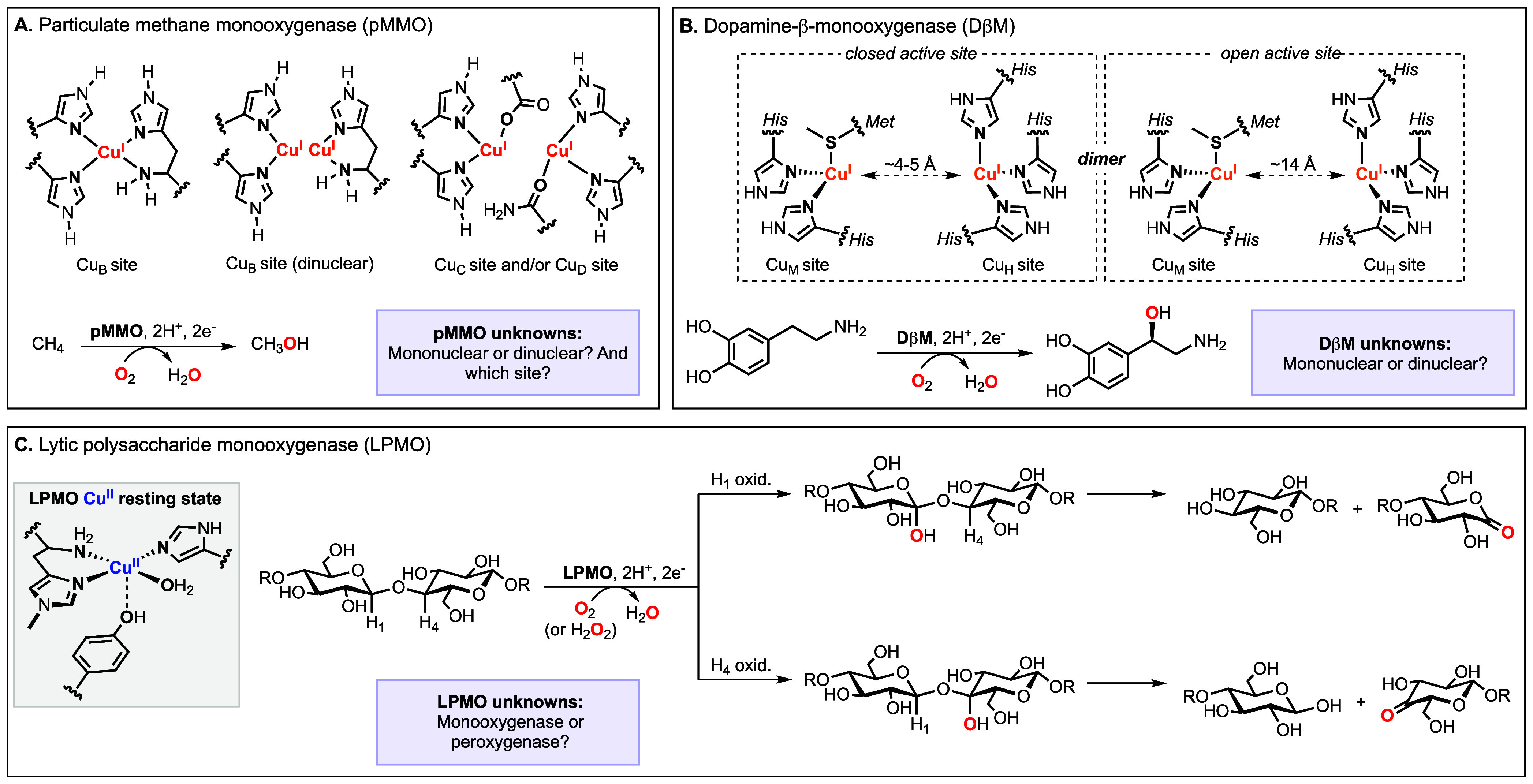

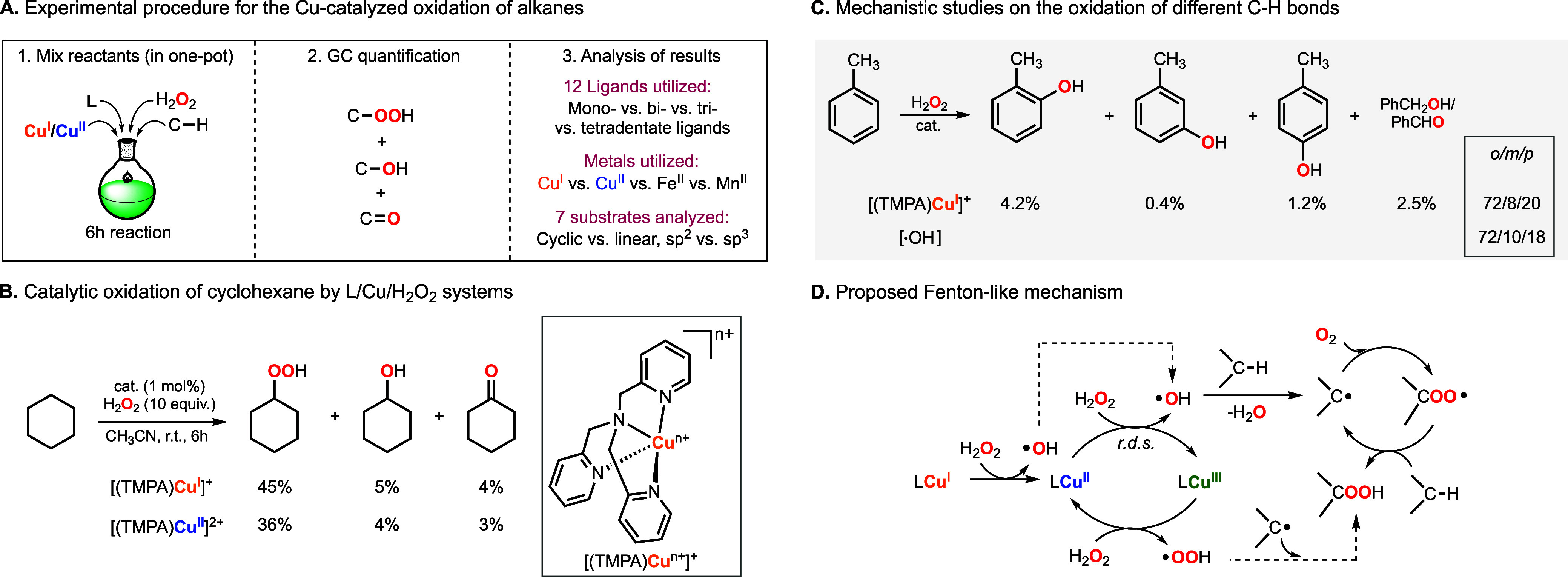

Cu-dependent metalloenzymes catalyze a wide array of oxidative transformations using O2 as an oxidant under mild conditions. These include the hydroxylation of challenging organic substrates (e.g., oxidation of methane to methanol in particulate methane monooxygenase) and the regio- and enantioselective hydroxylation of complex molecules (e.g., benzylic hydroxylation of dopamine to noradrenaline in dopamine-β-monooxygenase). Lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase enzymes (LPMOs) promote the C–H hydroxylation and subsequent cleavage of the polysaccharide chains found in natural materials such as cellulose or chitin. Recent reports on the reactivity of LPMOs suggest that, instead of O2, these Cu-dependent metalloenzymes utilize H2O2 as an oxidant. In 2015, our research lab reported that the catalytic hydroxylation of strong C–H bonds (e.g., cyclohexane) using Cu and H2O2 proceeded via formation of nonselective Fenton-like oxidants (hydroxyl and hydroperoxyl radicals). To achieve regioselectivity, LPMOs bind the organic substrate before exposing the Cu center to the oxidant, a reaction that leads to the formation of a highly organized ternary complex prior to substrate hydroxylation (i.e., metal–substrate–oxidant adduct). Based on this concept, our research lab has pioneered the use of Cu, directing groups, and green oxidants to promote the site-selective hydroxylation of ketones and aldehydes. In our first report on this topic, we carried out an extensive mechanistic analysis on the Cu-directed sp3 C–H hydroxylation reactions developed by Schönecker and co-workers. Our findings suggested that the reaction between CuI and O2 did not lead to the formation of dinuclear Cu2O2 (as it was previously suggested) but produced CuII and H2O2, which generated mononuclear CuII-hydroperoxide oxidants. Based on our mechanistic analysis, we redesigned the reaction conditions to utilize CuII and H2O2, which improved the yield, cost, and practicability of the Schönecker oxidations. Since then, our research lab has broadened the scope of substrates that can be oxidized using Cu, H2O2, and bidentate directing groups to include the γ-hydroxylation of sp2 C–H bonds and β-hydroxylation of sp3 C–H bonds. Our latest reports have focused on the regioselective hydroxylation of substituted unsymmetrical benzophenones (which occurred via the formation of an electrophilic CuOOH species) and, for the first time, enantioselective C–H hydroxylation reactions via the formation of Cu/O2 species. Our work highlights the importance of a mechanistic understanding to improve oxidation processes as well as underlines the use of metal-directed transformations to study the mechanisms by which metalloenzymes functionalize organic molecules.

Key References

Garcia-Bosch, I. ; Siegler, M. A. . Copper-Catalyzed Oxidation of Alkanes with H2O2 under a Fenton-like Regime. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (41), 12873–12876 . Copper complexes catalyze the hydroxylation of strong C–H bonds using H2O2 via formation of O-centered radicals.

Trammell, R. ; See, Y. Y. ; Herrmann, A. T. ; Xie, N. ; Díaz, D. E. ; Siegler, M. A. ; Baran, P. S. ; Garcia-Bosch, I. . Decoding the Mechanism of Intramolecular Cu-Directed Hydroxylation of sp3 C–H Bonds. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82 (15), 7887–7904 . Mechanistic studies on the Cu-directed C–H hydroxylation reactions developed by Schönecker revealed that the oxidations involved the formation of mononuclear species derived from Cu and H2O2.

Zhang, S. ; Goswami, S. ; Schulz, K. H. G. ; Gill, K. ; Yin, X. ; Hwang, J. ; Wiese, J. ; Jaffer, I. ; Gil, R. R. ; Garcia-Bosch, I. . Regioselective Hydroxylation of Unsymmetrical Ketones Using Cu, H2O2, and Imine Directing Groups via Formation of an Electrophilic Cupric Hydroperoxide Core. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89 (4), 2622–2636 . This study revealed that the formation of electrophilic copper(II) hydroperoxide intermediates leads to the regioselective C–H hydroxylation of unsymmetrical ketones.

Petrillo, A. ; Kirchgeßner-Prado, K. F. ; Hiller, D. ; Eisenlohr, K. A. ; Rubin, G. ; Würtele, C. ; Goldberg, R. ; Schatz, D. ; Holthausen, M. C. ; Garcia-Bosch, I. ; et al. Expanding the Clip-and-Cleave Concept: Approaching Enantioselective C–H Hydroxylations by Copper Imine Complexes Using O2 and H2O2 as Oxidants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146 (37), 25689–25700 . This work reports the first example of an enantioselective C–H hydroxylation reaction using Cu, green oxidants (O2 and H2O2), and chiral directing groups.

Introduction

Cu-dependent oxygenases and oxidases perform the selective oxidation of organic substrates, including dehydrogenation and hydroxylation transformations, under mild conditions (room temperature, atmospheric pressure) using natural oxidants (O2 and/or H2O2). − These Cu-dependent metalloenzymes are involved in the synthesis of important hormones and neurotransmitters (e.g., dopamine hydroxylation to norepinephrine in dopamine β-monooxygenase, DβM , ), cellulose degradation (lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases, LPMOs − ), small molecule activation (e.g., the oxidation of CH4 to CH3OH in particulate methane monooxygenase, pMMO − ), among other challenging transformations (see Figure ). − Differences in the active centers of these enzymes (ligand identity, number of Cu ions) lead to a broad range of Cu n /O2 intermediates with diverse reactivity. ,, For most of them, the reaction mechanism(s) that leads to substrate oxidation is not well understood. For example, several potential Cu active sites have been proposed for pMMO, including mononuclear and dinuclear centers (Figure , top left). ,− Additionally, the reaction mechanism by which CH4 oxidation is coupled with O2 reduction is completely unknown (Is O2 reduced to H2O2 before C–H oxidation? What Cu/O2 intermediates are formed? , ). The recent discovery of Cu-dependent metalloenzymes capable of performing novel transformations (e.g., peptide macrocyclization in BURP domain peptide cyclases, BpCs) and new groundbreaking evidence on the reactivity of well-studied enzymes (e.g., Do LPMOs use O2 or H2O2 to oxidize C–H bonds? , Are Cu2O2 species responsible for C–H hydroxylation in DβM? , ) requires novel approaches to identify the reactive Cu/O2 intermediates formed in the enzymes and to understand the reaction mechanism(s) that leads to selective C–H oxidation.

1.

Selected examples of Cu-dependent monooxygenase/peroxygenase enzymes that catalyze C–H hydroxylation, including particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO, A), dopamine β-monooxygenase (DβM, B), and lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase (LPMO, C).

Inorganic chemists have explored the use of low-weight Cu complexes that can mimic structure, spectroscopy, and/or reactivity of Cu-dependent enzymes. ,,, The main advantage of these systems is that they can be studied in organic solvents (an environment that mimics the hydrophobic nature of the active site of metalloenzymes), which allows for trapping and characterizing reaction intermediates at cryogenic temperatures (e.g., Cu/O2 species , ). The recent reports on Cu metalloenzymes able to oxidize strong C–H bonds (LPMO and pMMO) have inspired the development of synthetic Cu n /O2 species able to carry out these transformations. Stack found that a L2CuIII 2(O2–)2 core bearing bidentate histamine ligands (similar to the Hisbrace found in pMMO’s CuB site) promotes the intermolecular oxidation of weak C–H bonds. , Tolman has studied the oxidation of C–H bonds using a mononuclear LCuIII–OH complex, a putative intermediate for LPMO. , However, in both cases, the Cu/O2 species acted as 1e– oxidants and were not able to carry out the formation of the C–O bond. In 2016, our research lab developed a practical protocol to analyze the catalytic performance of a series of Cu complexes in the oxidation of organic substrates containing strong C–H bonds (e.g., cyclohexane) using H2O2 as the oxidant (see Figure A). The copper complexes derived from tris((2-pyridyl)methyl)amine (TMPA) were among the most active, leading to unprecedented turnover numbers (∼50 TON using 1 mol % of Cu). Alkyl hydroperoxides were the main oxidation products formed, which suggested that these Cu-catalyzed reactions occurred via the formation of nonselective Fenton-like oxidants (hydroxyl and/or hydroperoxyl radicals, see Figure B). Analysis of the products derived from the oxidation of toluene using Cu and H2O2 provided further evidence of the formation of hydroxyl radicals as active oxidants in these C–H functionalization reactions (Figure C). Kinetic experiments led us to propose the reaction mechanism depicted in Figure D, in which both CuI and CuII are capable of generating the O-centered radicals that lead to the formation of alkyl hydroperoxide products. Early work by Barton and co-workers showed that combining Cu salts and H2O2 in pyridine can promote the hydroxylation of strong C–H bonds, but those reactions were carried out under excess equivalents of the C–H substrate (H2O2 as limiting reagent), hence precluding the generation of oxidation products in high yields. ,

2.

Cu-catalyzed nonselective oxidation of strong C–H bonds using H2O2 as oxidant. (A) Experimental procedure for the generation of the Cu complexes that will catalyze the oxidation of C–H substrates with H2O2. (B) Results obtained in the oxidation of cyclohexane using Cu-TMPA complexes and H2O2. (C) Oxidation of toluene using the Cu/TMPA/H2O2 system that leads to a distribution of products similar to the ones observed for the hydroxyl radical. (D) Proposed mechanism for the Cu-catalyzed oxidation of alkanes with H2O2.

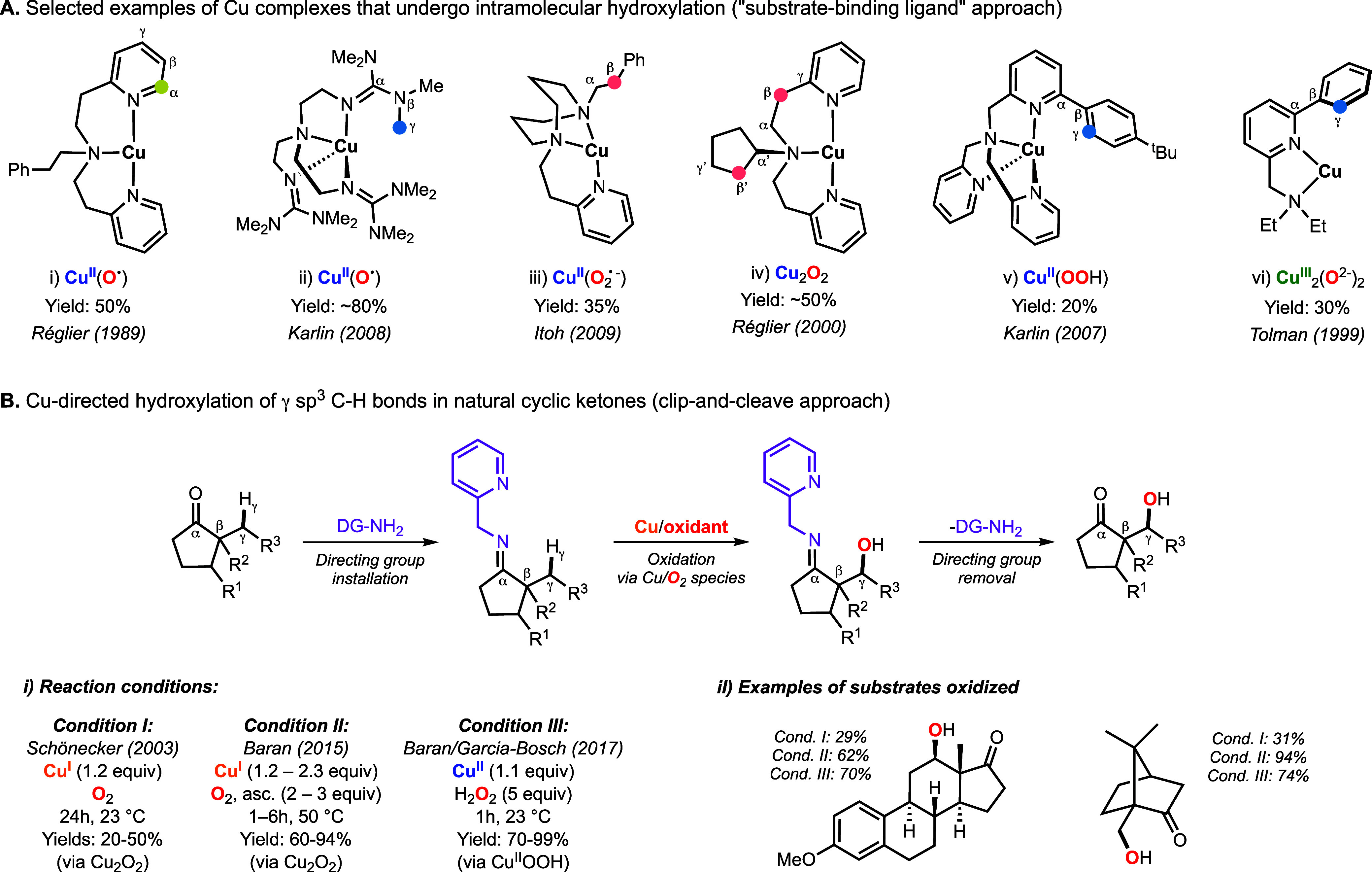

To achieve regioselectivity, Cu-dependent oxygenases bind the organic substrate before exposing the Cu center to the oxidant, a reaction that leads to the formation of a highly organized ternary complex prior to substrate hydroxylation (i.e., metal–substrate–oxidant adduct). During the last decades, several research groups have reported that mononuclear and dinuclear Cu/O2 species promote intramolecular C–H hydroxylation reactions resembling the reactivity observed in enzymes (Figure A). − The so-called substrate-binding ligand approach consists of exposing Cu complexes (CuI or CuII) to naturally relevant oxidants (O2 or H2O2) to produce metastable Cu/O2 species that decay to oxidize the ligand scaffold (see also relevant references by the Reinaud , and Rogić groups on Cu-mediated oxidations using a similar strategy).

3.

Cu-promoted intramolecular oxidation reactions observed in the substrate-binding ligand approach (A) and click-and-cleave approach (B). Note: according to Schönecker, the positions adjacent to the N coordinated to the Cu are named α, and the subsequent positions are named β, γ, δ, etc. This might lead to confusion because in organic chemistry, the α position of a carbonyl group is Cβ in Schönecker’s nomenclature. As shown in Figure A, Schönecker naming is useful because some Cu systems perform Cα functionalization. Note: Schönecker first and Baran later proposed that C–H hydroxylation occurred via formation of dinuclear species (Cu2O2). In our study, we proposed that the “so-called” Schönecker–Baran oxidations occur via formation of mononuclear species (CuIIOOH).

Inspired by the ability of Cu/O2 to perform intramolecular oxidations, Schönecker and co-workers reported the first example of a Cu-directed C–H hydroxylation reaction (Figure B). The authors utilized 2-picolylamine as a directing group, stoichiometric amounts of CuI, and dioxygen as the oxidant to carry out the regioselective γ-C–H hydroxylation of natural cyclic ketones, including steroids and (R)-camphor (Note: to be consistent with the nomenclature used by Schönecker and co-workers, the C atoms adjacent to the N coordinated to the Cu ion are named Cα. We realize that this is somewhat confusing in the context of functionalization of ketones and aldehydes because the α positions are commonly the ones adjacent to the C atom of the carbonyl group. Using Schönecker’s nomenclature, the installation of the DG produces an imine with a N atom that will be coordinated by Cu and with an adjacent C atom that will be named Cα (C derived from the carbonyl), making the C atoms adjacent to Cα, Cβ, which would commonly be α position of the carbonyl group). In 2015, Baran and co-workers improved the Schönecker oxidation by using Cu in excess (up to 2.3 equiv) and by combining O2 with stoichiometric amounts of reducing agents (up to 2.3 equiv), which led to a substantial increase in the reaction yields. Based on the yields achieved (below 50% in the absence of reductant), both research groups proposed the formation of dinuclear Cu/O2 species (CuII 2(O2 2–) and/or CuIII 2(O2–)2) as hydroxylating reagents because these are known to act as 2e– oxidants (i.e., after their formation, only half equivalent of the substrate–ligand is oxidized). , However, no spectroscopic evidence of the Cu species formed during the oxidation reactions was provided. In 2017, our research lab collaborated with the Baran group to determine the mechanism by which the Schönecker oxidations occur. Our data suggested that the “real” oxidant in these oxidations was hydrogen peroxide (derived from the 2H+/2e– reduction of O2 and solvent oxidation) and that mononuclear Cu/O2 species were involved in C–H hydroxylation. Based on the mechanistic analysis, we developed reaction conditions that utilized H2O2, leading to higher yields, lower costs (use of CuII without reductant), shorter reaction times, and improved practicability (i.e., no use of an O2 balloon and reactions carried out at room temperature).

Cu-Directed C–H Hydroxylation Reactions: Discovery, Scope, and Mechanism

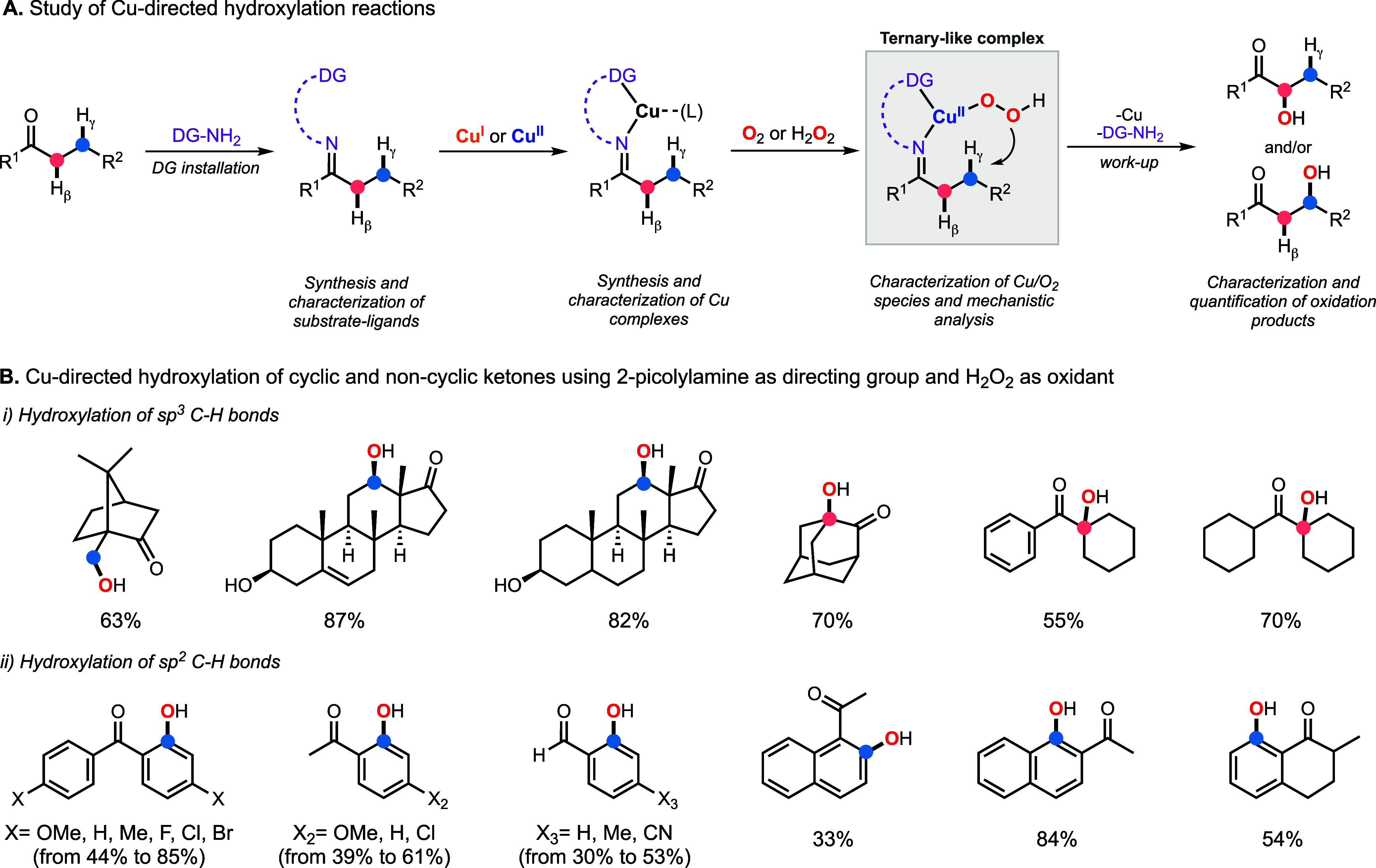

Our interest in Cu-directed oxidations is 2-fold. On one hand, this approach allows for developing synthetic protocols to perform selective C–H hydroxylation reactions in a cheap, safe, practical, and selective manner. On the other hand, we can also gather mechanistic understanding of the reaction pathways by which Cu-dependent metalloenzymes catalyze the oxidation of organic substrates (Figure A). Our work on this topic typically includes the synthesis and characterization of the Cu complexes derived from the substrate–ligand systems, oxidation of these complexes under varying conditions (using O2 or H2O2 as oxidants at different temperatures and with different solvents), characterization of the Cu/O2 intermediates formed during the oxidation, and other mechanistic experiments (e.g., use of radical traps to intercept C-centered radical intermediates). As we have stated, our study on the mechanism of the so-called Schönecker–Baran oxidations revealed that the C–H hydroxylation reaction occurred via the formation of mononuclear CuIIOOH species, which allowed for developing reaction conditions based on the use of Cu and H2O2. In 2019, we expanded the substrate scope of the Cu-directed C–H hydroxylation reactions (Figure B). The oxidations were carried out in acetone using 2-picolylamine as the directing group, 1 equiv of CuI, and 5 equiv of H2O2 (30% in H2O), which were able to perform the γ-hydroxylation of sp2 C–H bonds (e.g., hydroxylation of substituted benzophenones), the β-hydroxylation of sp3 C–H bonds (e.g., hydroxylation of 2-adamantone), and the γ-hydroxylation of sp3 C–H bonds (e.g., hydroxylation of (R)-camphor).

4.

Approach followed in our work on Cu-directed C–H hydroxylation reactions (A) and some examples of the hydroxylation products synthesized (B).

The mechanism by which Cu promotes C–H bond oxidation is shown in Figure A. , Our mechanistic studies suggest that upon coordination to the substrate–ligand (species A in Figure A), CuI reacts with dioxygen to produce a metastable CuII-superoxide species, which decomposes to produce the corresponding CuII complex and superoxide anion in solution (from species B to C in Figure A). The superoxide is converted to H2O2 via solvent oxidation (note: the products derived from acetone oxidation were characterized and quantified), which then reacts with the CuII substrate–ligand complex to produce a CuIIOOH intermediate (species D in Figure A). The CuIIOOH species was generated in a quantitative fashion via the addition of H2O2 to the independently synthesized CuI and CuII substrate–ligand complexes, which allowed its characterization by UV–vis and EPR spectroscopy. Kinetic analysis of the reactions suggested that the CuIIOOH intermediate accumulated before the rate-determining step of the reaction. The mechanism by which the CuIIOOH undergoes O–O bond cleavage and C–H hydroxylation occurs was proposed to be dependent on the substrate oxidized (see Figure B). In the γ-hydroxylation of sp3 C–H bonds, the CuII-hydroperoxide intermediate undergoes homolytic O–O bond cleavage to generate a CuII-oxyl species and hydroxyl radical (from species E to species I in Figure B). The intramolecular reaction between the OH-radical and the substrate–ligand then produces a C-centered radical, which leads to C–O bond formation by reaction with the CuII-oxyl core (from species J to species E in Figure B). Both hydroxyl and C-centered radicals were trapped using external C–H substrates and halogenated solvents, respectively. In the γ-hydroxylation of sp2 C–H bonds, we proposed that the CuII-hydroperoxide oxidizes the substrate in a concerted fashion in which the O–O bond cleavage and C–O bond formation occur in one step (in Figure B, from species D to species E′ via formation of species K and species L). Our mechanistic proposal was supported by kinetic isotope measurements (an inverse KIE was measured, consistent with the C-sp2 to C-sp3 change in hybridization during the r.d.s.) and by DFT computations.

5.

(A) General mechanism for intramolecular C–H hydroxylation via the formation of mononuclear or dinuclear Cu/O2 species (A). Proposed reaction mechanisms for the intramolecular γ-hydroxylation of sp3 and sp2 C–H bonds (B).

While our data suggest that mononuclear CuIIOOH species are responsible for C–H hydroxylation, the involvement of dinuclear Cu2O2 cores should not be ruled out (see species F, G, and H in Figure A). Other research groups have found that Cu complexes bearing bidentate ligands that produce dinuclear Cu/O2 species (by reacting CuI with O2 or CuII with H2O2) can also perform intramolecular C–H hydroxylation reactions. , In 2021, we studied the ability of bi-, tri-, and tetradentate ligands to perform Cu-directed hydroxylation reactions, and we found that higher yields were achieved when bidentate directing groups (rather than tri- and tetradentate) and H2O2 (rather than O2) were used. Interestingly, some of the substrate–ligands utilized led to the formation of dinuclear Cu/O2 species (CuII 2(O2 2–) and CuIII 2(O2–)2) that did not lead to intramolecular C–H hydroxylation, reinforcing the idea that mononuclear species might be involved in substrate oxidation. A recent study by Murakami and co-workers described a new class of Cu-dependent metalloenzymes that cleave cellulose in an unprecedented fashion (not an LPMO enzyme) following an exo-type mechanism to generate cellobionic acid. The authors proposed that this enzyme adopts a homodimer configuration in which a mononuclear Cu active center reduces O2 to H2O2 (oxidase reactivity) and the other mononuclear center uses the H2O2 to carry out the hydroxylation of the substrate (peroxygenase chemistry), a reactivity that resembles the mechanism in Cu-directed γ-hydroxylation of C–H bonds using 2-picolylamine as directing group.

Regioselectivity in Cu-Directed C–H Hydroxylation Reactions

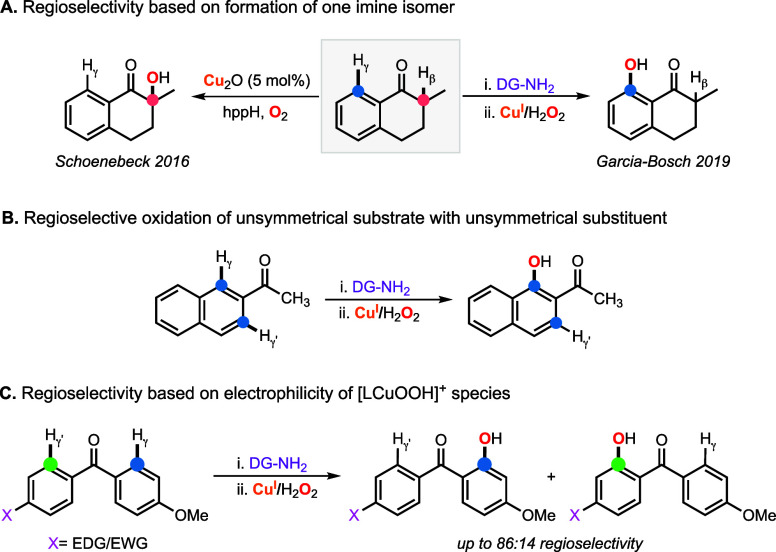

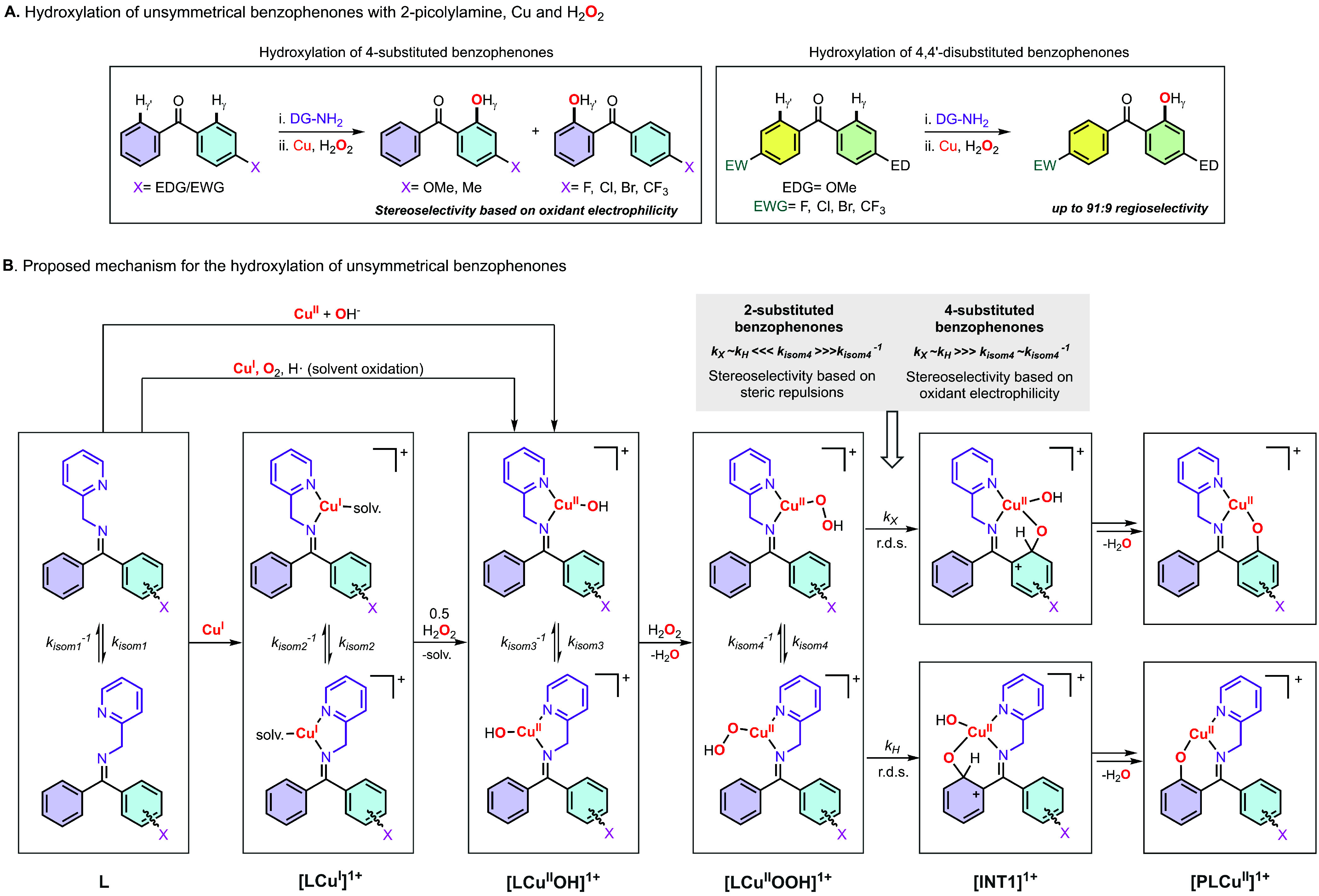

In 2024, we analyzed the Cu-directed hydroxylation of unsymmetrical ketones using 2-picolylamine as directing group and H2O2 as oxidant (see Figure ). Our study was primarily focused on the hydroxylation of unsymmetrical benzophenones, although other unsymmetrical ketones were also analyzed. When 2-substituted and 4-substituted benzophenones are used as substrates, the installation of the directing group can produce two imine isomers (E and Z), which can generate two oxidation products derived from γ-sp2 C–H hydroxylation. When 2-substituted benzophenones were used, we observed the formation of one of the imine isomers (Z isomer, with the DG pointing toward the unsubstituted phenyl ring) that upon addition of CuI and H2O2 only produced the corresponding Z-hydroxylation product. Conversely, the use of 4-substituted benzophenones led to the formation of the 2 imine isomers (E and Z) that were oxidized to the corresponding hydroxylation products (E and Z). Strikingly, the ratio of the substrate–ligand imine isomers (E/Z ∼ 60/40) was different from the ratio of hydroxylation products, favoring the oxidation of the phenyl rings containing electron-donating substituents. For example, installation of 2-picolylamine to 4-bromobenzophenone produced the two imine isomers with an E/Z ratio of 62/38 (in the E isomer the DG is pointing toward the ring with Br), that upon oxidation produce the hydroxylation products in a ratio of 30/70 (the hydroxylation occurred mainly in the unsubstituted ring). The regioselectivity was enhanced by using 4,4′-disubstituted benzophenones such as 4-methoxy-4′-trifluorobenzophenone, whose Cu-directed hydroxylation favored the oxidation of the phenyl ring containing the MeO substituent (ratio of 86/14). For 4-substituted and 4,4′-disubstituted benzophenones, our mechanistic studies suggested the existence of fast isomerization equilibria between the imine isomers before the rate-determining step of the reaction, in which an electrophilic mononuclear CuIIOOH favored the hydroxylation of the electron-rich arene ring (Figure B). Conversely, we proposed that for 2-substituted benzophenones, slow (or no) equilibria between the imine isomers occurred, leading to hydroxylation of the unsubstituted arene ring.

6.

Scope (A) and mechanism (B) of the Cu-directed hydroxylation of unsymmetrical benzophenones using 2-picolylamine as the directing group.

The regioselectivity in Cu-directed C–H hydroxylation reactions using 2-picolylamine and H2O2 is based on three factors (Figure ). The first factor to consider is the formation of 1 or 2 imine substrate–ligands. For example, the installation of 2-picolylamine to 2-methyl-1-tetralone forms only the imine isomer in which the directing group is pointing toward the arene ring, which allowed for carrying out the γ-sp2 C–H hydroxylation in a selective fashion. Conversely, Schöenebeck and co-workers have shown that 2-methyl-1-tetralone can undergo β-sp3 C–H hydroxylation using Cu2O, a strong base, and O2 as oxidant (Figure A). Interestingly, the formation of a sole imine isomer can also lead to the regioselective hydroxylation of sp2 C–H bonds of unsymmetrical ketones containing unsymmetrical arene substituents. For example, we observed that the Cu-directed hydroxylation of 2-acetonaphthone led to the selective hydroxylation of the position 1 of the naphthyl ring (84% yield) leaving the position 3 (also a γ-sp2 C–H bond) unreacted (Figure B). Thus, the regioselectivity of the Cu-directed hydroxylation of 2-methyl-1-tetralone and 2-acetonaphthone seems to be dictated by the substrate–ligand topology. In contrast, the regioselectivity in the Cu-directed hydroxylation of unsymmetrical 4-substituted benzophenones relies on the electrophilicity of the Cu/O2 species formed, which favors the hydroxylation of electron-rich arene rings (see Figure C).

7.

Regioselective oxidation of substrate–ligands with multiple C–H bonds using 2-picolylamine as directing group based on the formation of one imine isomer (A), based on the functionalization of a substrate with unsymmetrical substituents (B), and based on the formation of an electrophilic oxidant (C).

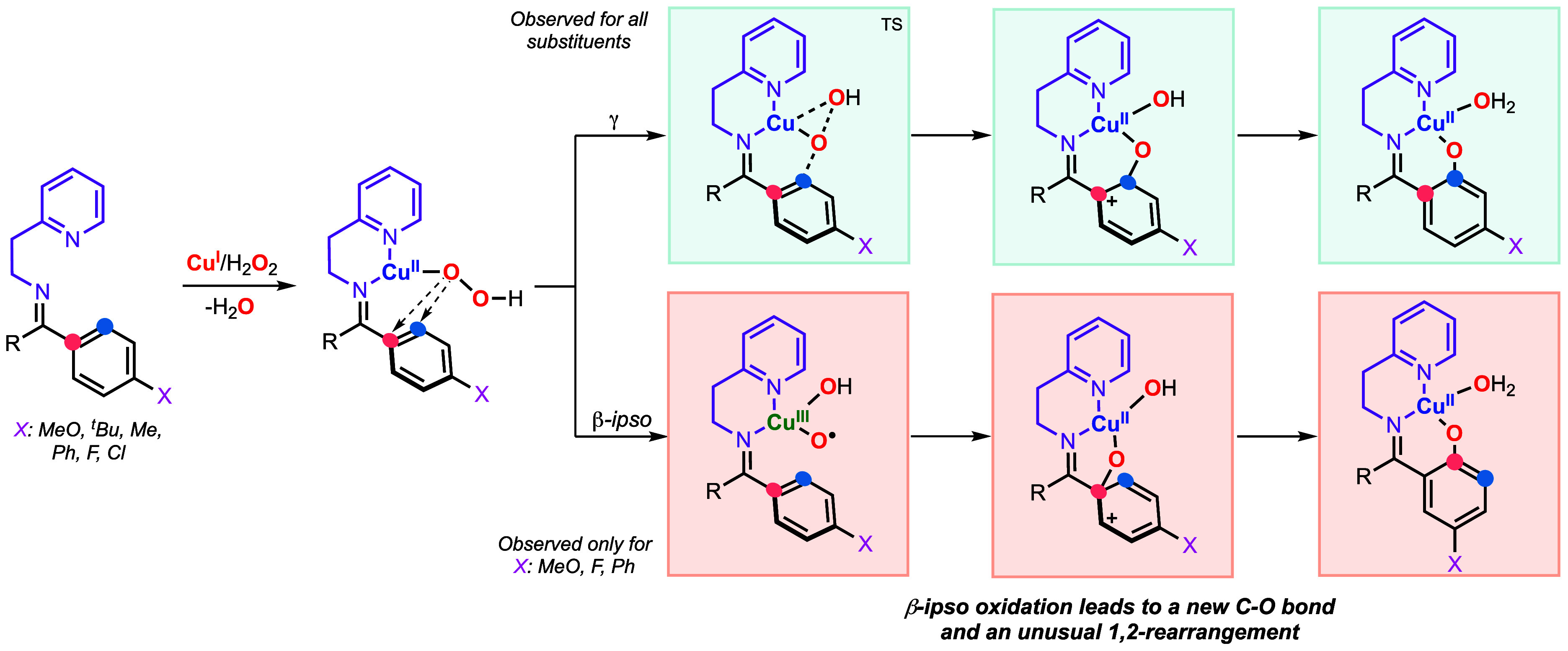

In 2024, we described the Cu-directed hydroxylation of benzophenones using 2-(2-aminoethyl)pyridine as directing group (Figure ). To our surprise, we observed that the substrate–ligands derived from 4-methoxy, 4-fluoro, and 4-phenylbenzophenone led to the formation of an additional oxidation product attributed to β-ipso oxidation (for 4-methoxy-benzophenone, the ipso-oxidation was highly favored). As shown in Figure , ipso-oxidation leads to the formation of a Cβ–O bond that triggers an unusual 1,2-rearrangement to produce a Cα–Cγ bond (with apparent shift of the substituent from the 4 to the 5 position of the phenyl ring). Our mechanistic studies suggested that after generation of a mononuclear CuIIOOH species, this intermediate undergoes a concerted O–O bond cleavage with concomitant electrophilic attack to the Cγ of the phenyl ring to produce the γ-C–H hydroxylation product, a reaction pathway analogous to the one proposed in the γ-sp2 C–H hydroxylation reactions in the systems with 2-picolylamine. However, the use of 2-(2-aminoethyl)pyridine can also trigger β-ipso oxidation. Computations suggested that this unusual oxidation occurs in a stepwise fashion in which the O–O bond cleavage leads to the formation of a CuIII-oxyl-hydroxo intermediate that performs the electrophilic ipso-oxidation of the aryl ring. The 1,2-rearrangement was hypothesized to occur due to the strain release upon conversion of the spiro intermediate formed after the ipso-attack (from a 5-membered ring with Cu–Nim–Cα–Cβ–O to a 6-membered ring with Cu–Nim–Cα–Cγ–Cβ–O).

8.

Proposed mechanisms for the ipso-oxidation and γ-hydroxylation of unsymmetrical benzophenones using Cu, H2O2, and 2-(2-aminoethyl)pyridine as directing group.

The installation of 2-(2-aminoethyl)pyridine to unsymmetrical benzophenone also produced two imine isomers. When compared to the oxidation of the systems derived from 2-picolylamine (which only led to the 2 products derived from γ-sp2 C–H hydroxylation), the systems derived from 2-(2-aminoethyl)pyridine can potentially form four oxidation products derived from β- and γ-sp2 oxidation (see Figure ). Analysis of the oxidation of unsymmetrical disubstituted benzophenones suggested that the Cu/O2 oxidant formed in the 2-(2-aminoethyl)pyridine systems is more selective than the one formed in the 2-picolylamine analogues. For example, the oxidation of 4-methoxy-4′-methylbenzophenone using 2-picolylamine slightly favored the oxidation of the arene containing the MeO substituent (53/47 ratio), while 2-(2-aminoethyl)pyridine had an enhanced preference (81/19 ratio). For all of the systems derived from 4-methoxy-4′-X-benzophenones and 2-(2-aminoethyl)pyridine, we observed a high preference for the β-oxidation of the arene ring containing the MeO substituent.

9.

Comparison of the regioselectivity observed in the Cu-directed hydroxylation of unsymmetrical benzophenones using 2-picolylamine or 2-(2-aminoethyl)pyridine as directing groups.

Enantioselectivity in Cu-Directed C–H Hydroxylation Reactions

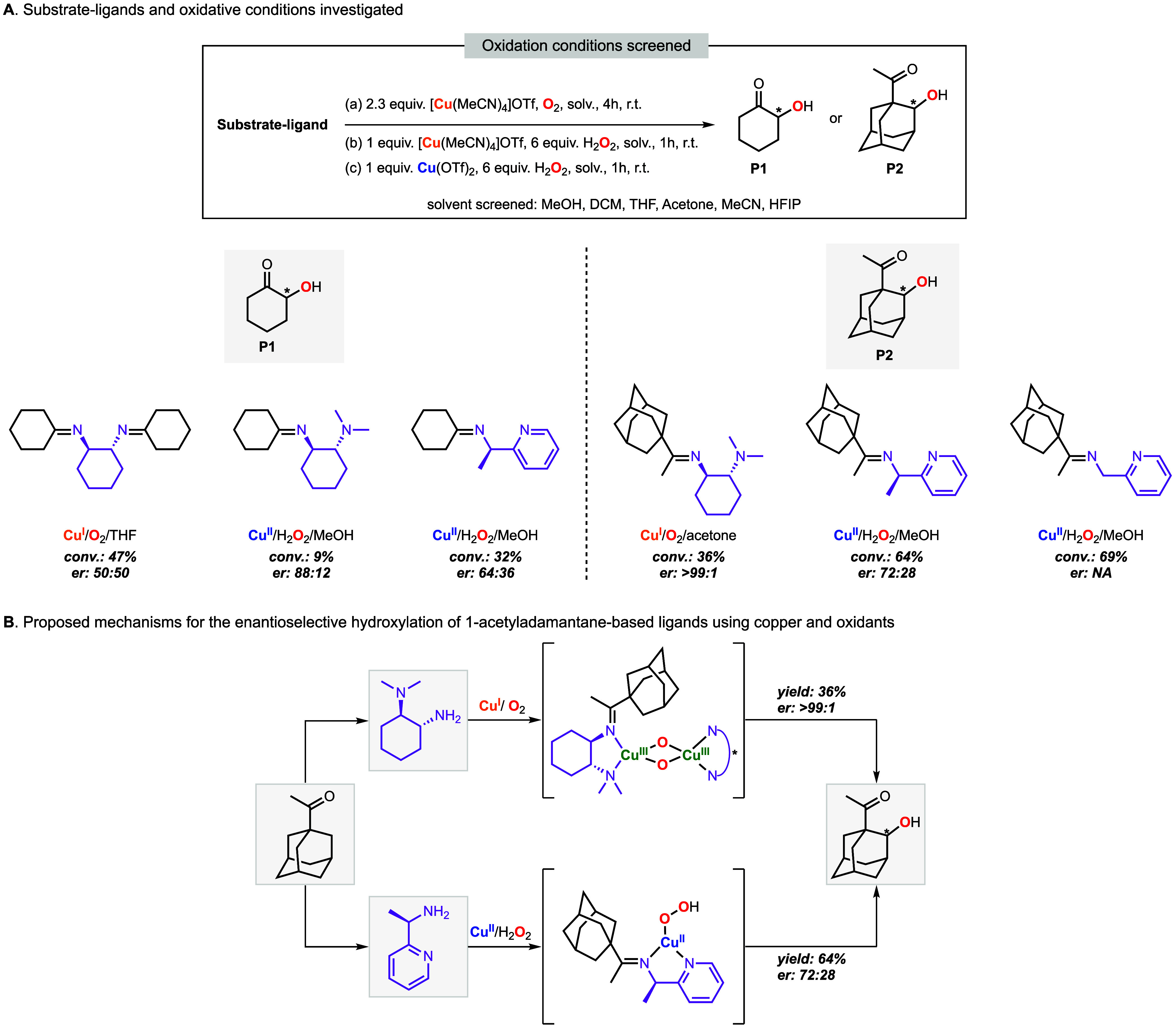

In collaboration with the Holthausen group and the Schindler group, we recently reported the first example of enantioselective Cu-directed C–H hydroxylation reactions (see Figure ). The use of chiral bidentate directing groups such as (1R, 2R)-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine, (1R, 2R)-N 1,N 1-dimethylcyclohexane-1,2-diamine and (1R)-1-(2-pyridinyl)ethanamine resulted in the regio- and enantioselective β-hydroxylation of 2-cyclohexanone and γ-hydroxylation of 1-acetyladamantane. The substrate–ligands were oxidized using three different oxidation conditions that were previously optimized in our laboratories (based on the use of CuI + O2, CuI + H2O2, and CuII + H2O2) in different organic solvents (Figure A). Better yields and enantioselectivities were obtained for the substrate–ligands derived from 1-acetyladamantane. For the substrate–ligand derived from (1R, 2R)-N 1,N 1-dimethylcyclohexane-1,2-diamine and 1-acetyladamantane, we found that C–H hydroxylation occurred only when CuI and O2 were used. Time-resolved UV–vis spectroscopy measurements carried out at cryogenic temperatures revealed that these systems were oxidized by dinuclear CuIII 2(O2–)2 (Figure B). Conversely, the hydroxylation of the substrate–ligands containing pyridine were enhanced when CuII and H2O2 were used via the formation of mononuclear CuIIOOH intermediates. Our results indicated that multiple Cu/O2 species can lead to regio- and enantioselective C–H hydroxylation and that their formation is dependent on the directing group identity (e.g., N-alkylic vs pyridinic directing groups) and the oxidation conditions utilized (e.g., CuI/O2 vs CuII/H2O2).

10.

Copper-promoted enantioselective C–H hydroxylation of cyclohexanone-based and 1-acetyladamantane-based substrate–ligands using O2 and H2O2 as oxidants, including the reaction conditions screened (A) and mechanisms proposed (B).

Concluding Remarks and Future Outlook

As we have shown, work on Cu-directed C–H hydroxylation provides new insights into the reaction mechanism(s) by which Cu-dependent monooxygenases and peroxygenases oxidize organic substrates. ,, Mechanistic understanding has led to the development of new oxidation protocols based on the use of Cu and H2O2, which have been applied in the total synthesis of complex organic molecules via early stage and late-stage C–H functionalization. − Despite the many significant advances made during the past decade, the journey has just begun. We believe that the next steps should be focused on increasing the variety of oxidative transformations that can be carried out with this approach. First, we aim to expand the scope of ketone and aldehyde substrates that can be functionalized (e.g., developing protocols to perform the δ-C–H hydroxylation of sp2 and sp3 substrates in a selective fashion) and carry out mechanistic studies to understand the underpinning principles that govern regioselectivity in these transformations (e.g., Is the β/γ/δ selectivity largely determined by the substrate or can it be controlled via DG modification? Can different Cu/O2 species lead to different selectivity?). Second, we hypothesize that we can adapt Cu-directed oxidations to perform the C–H hydroxylation of amine substrates using aldehydes as DGs, a transformation that would produce amino alcohols, which are widespread motifs in natural products and pharmaceuticals. −

One of the main drawbacks of the directed approach is the use of stoichiometric amounts of DG and metal and the need to install the DG (isolation of the substrate–ligand) before oxidation. Over the past decade, Yu and others have pioneered the use of transient DGs in metal-directed C–H functionalization reactions. − This approach (usually used in Pd catalysis and only two examples with Cu , ) relies on the reversible formation of an imine bond, which might allow for performing Cu-directed C–H hydroxylation reactions using catalytic amounts of DG and Cu.

Research on the bioinorganic chemistry of Cu is more alive than ever. ,, In the past few years, several new Cu-dependent metalloenzymes capable of performing unprecedented organic transformations have been discovered. These include BURP domain peptide cyclases (BpCs, which catalyze the oxidative macrocyclization of peptides via C–C, C–N, or C–O bond formation between aromatic amino acids and unactivated C–H bonds of other amino acids), Cu-dependent halogenases and pseudohalogenases (ApnU, which catalyze sp3 C–H chlorination, bromination, iodination, and thiocyanation), among others. We believe that the development of synthetic inorganic complexes (including Cu-directed systems) capable of mimicking the structure, spectroscopy, and reactivity of the active sites of these enzymes will provide insights into the mechanisms by which these natural catalysts perform these oxidations and will lead to the development of useful synthetic protocols to carry out these challenging organic transformations.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R35GM137914 (to I.G.B.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Sunipa Goswami received her M.Sc. degree in Chemistry from Pondicherry University, India, in 2019. Currently, she is a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate at Carnegie Mellon University working under the supervision of Prof. Isaac Garcia-Bosch. Her research is focused on developing synthetic strategies to functionalize C–H bonds inspired by the reactivity of Cu-oxygenase enzymes, which carry out the oxidation of strong C–H bonds using green oxidants (O2 and/or H2O2) under mild conditions (room temperature, atmospheric pressure).

Isaac Garcia-Bosch received his Ph.D. from the University of Girona in 2011, supervised by Professor Miquel Costas and Professor Xavi Ribas. He then moved to the United States as a Marie Curie IOF postdoctoral fellow to work with Professor Kenneth D. Karlin at the Johns Hopkins University. He started his independent career at the Southern Methodist University in 2015, and moved to Carnegie Mellon University in 2021 as Associate Professor of Chemistry. His research interests include the development of metal complexes to perform challenging transformations such as C–H hydroxylation and multiproton multielectron reactions.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Garcia-Bosch I., Siegler M. A.. Copper-Catalyzed Oxidation of Alkanes with H2O2 under a Fenton-like Regime. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55(41):12873–12876. doi: 10.1002/anie.201607216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trammell R., See Y. Y., Herrmann A. T., Xie N., Díaz D. E., Siegler M. A., Baran P. S., Garcia-Bosch I.. Decoding the Mechanism of Intramolecular Cu-Directed Hydroxylation of sp3 C–H Bonds. J. Org. Chem. 2017;82(15):7887–7904. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.7b01069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Goswami S., Schulz K. H. G., Gill K., Yin X., Hwang J., Wiese J., Jaffer I., Gil R. R., Garcia-Bosch I.. Regioselective Hydroxylation of Unsymmetrical Ketones Using Cu, H2O2, and Imine Directing Groups via Formation of an Electrophilic Cupric Hydroperoxide Core. J. Org. Chem. 2024;89(4):2622–2636. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.3c02647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrillo A., Kirchgeßner-Prado K. F., Hiller D., Eisenlohr K. A., Rubin G., Würtele C., Goldberg R., Schatz D., Holthausen M. C., Garcia-Bosch I.. et al. Expanding the Clip-and-Cleave Concept: Approaching Enantioselective C–H Hydroxylations by Copper Imine Complexes Using O2 and H2O2 as Oxidants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024;146(37):25689–25700. doi: 10.1021/jacs.4c07777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon E. I., Heppner D. E., Johnston E. M., Ginsbach J. W., Cirera J., Qayyum M., Kieber-Emmons M. T., Kjaergaard C. H., Hadt R. G., Tian L.. Copper Active Sites in Biology. Chem. Rev. 2014;114(7):3659–3853. doi: 10.1021/cr400327t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. J., Diaz D. E., Quist D. A., Karlin K. D.. Copper(I)-Dioxygen Adducts and Copper Enzyme Mechanisms. Isr. J. Chem. 2016;56(9–10):738–755. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201600025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwell C. E., Gagnon N. L., Neisen B. D., Dhar D., Spaeth A. D., Yee G. M., Tolman W. B.. Copper–Oxygen Complexes Revisited: Structures, Spectroscopy, and Reactivity. Chem. Rev. 2017;117(3):2059–2107. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citek C., Herres-Pawlis S., Stack T. D. P.. Low Temperature Syntheses and Reactivity of Cu2O2 Active-Site Models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48(8):2424–2433. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinman J. P.. The Copper-Enzyme Family of Dopamine beta-Monooxygenase and Peptidylglycine alpha-Hydroxylating Monooxygenase: Resolving the Chemical Pathway for Substrate Hydroxylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:3013–3016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips C. M., Beeson W. T., Cate J. H., Marletta M. A.. Cellobiose Dehydrogenase and a Copper-Dependent Polysaccharide Monooxygenase Potentiate Cellulose Degradation by Neurospora crassa. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011;6(12):1399–1406. doi: 10.1021/cb200351y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian R., Smith S. M., Rawat S., Yatsunyk L. A., Stemmler T. L., Rosenzweig A. C.. Oxidation of methane by a biological dicopper centre. Nature. 2010;465(7294):115–119. doi: 10.1038/nature08992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendelboe T. V., Harris P., Zhao Y., Walter T. S., Harlos K., El Omari K., Christensen H. E. M.. The crystal structure of human dopamine β-hydroxylase at 2.9 Å resolution. Science Advances. 2016;2(4):e1500980. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangasky J. A., Detomasi T. C., Marletta M. A.. Glycosidic Bond Hydroxylation by Polysaccharide Monooxygenases. Trends in Chemistry. 2019;1(2):198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.trechm.2019.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meier K. K., Jones S. M., Kaper T., Hansson H., Koetsier M. J., Karkehabadi S., Solomon E. I., Sandgren M., Kelemen B.. Oxygen Activation by Cu LPMOs in Recalcitrant Carbohydrate Polysaccharide Conversion to Monomer Sugars. Chem. Rev. 2018;118(5):2593–2635. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frandsen K. E. H., Simmons T. J., Dupree P., Poulsen J.-C. N., Hemsworth G. R., Ciano L., Johnston E. M., Tovborg M., Johansen K. S., von Freiesleben P.. et al. The molecular basis of polysaccharide cleavage by lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016;12:298. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci F. J., Rosenzweig A. C.. Direct Methane Oxidation by Copper- and Iron-Dependent Methane Monooxygenases. Chem. Rev. 2024;124(3):1288–1320. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.3c00727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang V. C. C., Maji S., Chen P. P. Y., Lee H. K., Yu S. S. F., Chan S. I.. Alkane Oxidation: Methane Monooxygenases, Related Enzymes, and Their Biomimetics. Chem. Rev. 2017;117(13):8574–8621. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo C. W., Tucci F. J., He Y., Rosenzweig A. C.. Recovery of particulate methane monooxygenase structure and activity in a lipid bilayer. Science. 2022;375(6586):1287–1291. doi: 10.1126/science.abm3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci F. J., Rosenzweig A. C.. Structures of methane and ammonia monooxygenases in native membranes. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2025;122(1):e2417993121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2417993121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel M. J., Meier K. K., Lafrance-Vanasse J., Lim H., Tsai C.-L., Hedman B., Hodgson K. O., Tainer J. A., Solomon E. I., Bertozzi C. R.. Formylglycine-generating enzyme binds substrate directly at a mononuclear Cu(I) center to initiate O2 activation. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2019;116(12):5370–5375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1818274116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsbach J. W., Kieber-Emmons M. T., Nomoto R., Noguchi A., Ohnishi Y., Solomon E. I.. Structure/function correlations among coupled binuclear copper proteins through spectroscopic and reactivity studies of NspF. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2012;109(27):10793–10797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208718109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quist D. A., Diaz D. E., Liu J. J., Karlin K. D.. Activation of dioxygen by copper metalloproteins and insights from model complexes. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2017;22(2):253–288. doi: 10.1007/s00775-016-1415-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Tovar J., Leblay R., Wang Y., Wojcik L., Thibon-Pourret A., Réglier M., Simaan A. J., Le Poul N., Belle C.. Copper–oxygen adducts: new trends in characterization and properties towards C–H activation. Chemical Science. 2024;15(27):10308–10349. doi: 10.1039/D4SC01762E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. O., MacMillan F., Wang J., Nisthal A., Lawton T. J., Olafson B. D., Mayo S. L., Rosenzweig A. C., Hoffman B. M.. Particulate methane monooxygenase contains only mononuclear copper centers. Science. 2019;364(6440):566–570. doi: 10.1126/science.aav2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. O., Rosenzweig A. C.. A tale of two methane monooxygenases. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2017;22(2):307–319. doi: 10.1007/s00775-016-1419-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L., Caldararu O., Rosenzweig A. C., Ryde U.. Quantum Refinement Does Not Support Dinuclear Copper Sites in Crystal Structures of Particulate Methane Monooxygenase. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018;57(1):162–166. doi: 10.1002/anie.201708977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culpepper M. A., Cutsail G. E., Hoffman B. M., Rosenzweig A. C.. Evidence for Oxygen Binding at the Active Site of Particulate Methane Monooxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134(18):7640–7643. doi: 10.1021/ja302195p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W., Qu X., Shaik S., Wang B.. Deciphering the oxygen activation mechanism at the CuC site of particulate methane monooxygenase. Nature Catalysis. 2021;4(4):266–273. doi: 10.1038/s41929-021-00591-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noyon M. R. O. K., Hematian S.. Peptide crosslinking by a class of plant copper enzymes. Trends in Chemistry. 2024;6(11):649–655. doi: 10.1016/j.trechm.2024.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Wang Z., Davies G. J., Walton P. H., Rovira C.. Activation of O2 and H2O2 by Lytic Polysaccharide Monooxygenases. ACS Catal. 2020;10(21):12760–12769. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c02914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bissaro B., Streit B., Isaksen I., Eijsink V. G. H., Beckham G. T., DuBois J. L., Røhr Å. K.. Molecular mechanism of the chitinolytic peroxygenase reaction. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2020;117:1504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904889117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush K. W., Eastman K. A. S., Welch E. F., Bandarian V., Blackburn N. J.. Capturing the Binuclear Copper State of Peptidylglycine Monooxygenase Using a Peptidyl-Homocysteine Lure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024;146(8):5074–5080. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c14705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P., Fan F., Song J., Peng W., Liu J., Li C., Cao Z., Wang B.. Theory Demonstrated a “Coupled” Mechanism for O2 Activation and Substrate Hydroxylation by Binuclear Copper Monooxygenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141(50):19776–19789. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b09172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis E. A., Tolman W. B.. Reactivity of Dioxygen-Copper Systems. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:1047–1076. doi: 10.1021/cr020633r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirica L. M., Ottenwaelder X., Stack T. D. P.. Structure and Spectroscopy of Copper-Dioxygen Complexes. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:1013–1045. doi: 10.1021/cr020632z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gary J. B., Citek C., Brown T. A., Zare R. N., Wasinger E. C., Stack T. D. P.. Direct Copper(III) Formation from O2 and Copper(I) with Histamine Ligation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138(31):9986–9995. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue P. J., Tehranchi J., Cramer C. J., Sarangi R., Solomon E. I., Tolman W. B.. Rapid C–H Bond Activation by a Monocopper(III)–Hydroxide Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133(44):17602–17605. doi: 10.1021/ja207882h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciano L., Davies G. J., Tolman W. B., Walton P. H.. Bracing copper for the catalytic oxidation of C–H bonds. Nature Catalysis. 2018;1(8):571–577. doi: 10.1038/s41929-018-0110-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton D. H. R., Beviere S. D., Chavasiri W., Csuhai E., Doller D.. The Functionalization of Saturated Hydrocarbons. Part XXI+. The Fe(III)-Catalyzed and the Cu(II)-Catalyzed Oxidation of Saturated Hydrocarbons by Hydrogen Peroxide: A Comparative Study. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:2895–2910. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90971-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton D. H. R., Doller D., Geletii Y. V.. The Efficient Oxidation of Alkanes by Hydrogen Peroxide in Pyridine Mixed Solvents Catalyzed by Copper and Other Transition Metal Salts. Mendeleev Commun. 1991;1:115–116. doi: 10.1070/MC1991v001n03ABEH000070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons T. J., Frandsen K. E. H., Ciano L., Tryfona T., Lenfant N., Poulsen J. C., Wilson L. F. L., Tandrup T., Tovborg M., Schnorr K.. et al. Structural and electronic determinants of lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase reactivity on polysaccharide substrates. Nat. Commun. 2017;8(1):1064. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01247-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reglier M., Amadei E., Tadayoni R., Waegell B.. Pyridine Nucleus Hydroxylation with Copper Oxygenase Models. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1989;8:447–450. doi: 10.1039/C39890000447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maiti D., Lee D.-H., Gaoutchenova K., Würtele C., Holthausen M. C., Sarjeant A. A. N., Sundermeyer J., Schindler S., Karlin K. D.. Reactions of a Copper(II) Superoxo Complex Lead to C–H and O–H Substrate Oxygenation: Modeling Copper-Monooxygenase C–H Hydroxylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47(1):82–85. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunishita A., Kubo M., Sugimoto H., Ogura T., Sato K., Takui T., Itoh S.. Mononuclear Copper(II)–Superoxo Complexes that Mimic the Structure and Reactivity of the Active Centers of PHM and DβM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131(8):2788–2789. doi: 10.1021/ja809464e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blain I., Giorgi M., De Riggi I., Réglier M.. Substrate-Binding Ligand Approach in Chemical Modeling of Copper-Containing Monooxygenases, 1 Intramolecular Stereoselective Oxygen Atom Insertion into a Non-Activated C−H Bond. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2000;2000:393–398. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0682(200002)2000:2<393::AID-EJIC393>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maiti D., Lucas H. R., Sarjeant A. A. N., Karlin K. D.. Aryl Hydroxylation from a Mononuclear Copper-Hydroperoxo Species. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129(22):6998–6999. doi: 10.1021/ja071704c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland P. L., Rodgers K. R., Tolman W. B.. Is the Bis(μ-oxo)dicopper Core Capable of Hydroxylating an Arene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999;38:1139–1142. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990419)38:8<1139::AID-ANIE1139>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevielle P., Maumy M.. Copper-mediated α-hydroxylation of N-salicyloyl-glycine. a model for peptidyl-glycine α-amidating monooxygenase (PAM) Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32(31):3831–3834. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)79387-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinaud O., Capdevielle P., Maumy M.. 2-(N-amido)-4-nitrophenol: A new ligand for the copper-mediated hydroxylation of aromatics by trimethylamine N-oxide. J. Mol. Catal. 1991;68(2):L13–L15. doi: 10.1016/0304-5102(91)80067-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demmin T. R., Swerdloff M. D., Rogic M. M.. Copper(II)-induced oxidations of aromatic substrates - catalytic conversion of catechols to ortho-benzoquinones - copper phenoxides as intermediates in the oxidation of phenol and a single-step conversion of phenol, ammonia, and oxygen into muconic acid mononitrile. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103(19):5795–5804. doi: 10.1021/ja00409a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schonecker B., Zheldakova T., Liu Y., Kotteritzsch M., Gunther W., Gorls H.. Biomimetic hydroxylation of nonactivated CH2 groups with copper complexes and molecular oxygen. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42(28):3240–3244. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See Y. Y., Herrmann A. T., Aihara Y., Baran P. S.. Scalable C–H Oxidation with Copper: Synthesis of Polyoxypregnanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137(43):13776–13779. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trammell R., D’Amore L., Cordova A., Polunin P., Xie N., Siegler M. A., Belanzoni P., Swart M., Garcia-Bosch I.. Directed Hydroxylation of sp2 and sp3 C–H Bonds Using Stoichiometric Amounts of Cu and H2O2 . Inorg. Chem. 2019;58(11):7584–7592. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b00901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J., Gupta P., Angersbach F., Tuczek F., Näther C., Holthausen M. C., Schindler S.. Selective Aromatic Hydroxylation with Dioxygen and Simple Copper Imine Complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 2015;21(33):11735–11744. doi: 10.1002/chem.201501003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J., Zhyhadlo Y. Y., Butova E. D., Fokin A. A., Schreiner P. R., Förster M., Holthausen M. C., Specht P., Schindler S.. Aerobic Aliphatic Hydroxylation Reactions by Copper Complexes: A Simple Clip-and-Cleave Concept. Chem. Eur. J. 2018;24(58):15543–15549. doi: 10.1002/chem.201802607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Trammell R., Cordova A., Siegler M. A., Garcia-Bosch I.. Cu-promoted intramolecular hydroxylation of C−H bonds using directing groups with varying denticity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2021;223:111557. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2021.111557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos C. A., Morais M. A. B., Mandelli F., Lima E. A., Miyamoto R. Y., Higasi P. M. R., Araujo E. A., Paixão D. A. A., Junior J. M., Motta M. L.. et al. A metagenomic ‘dark matter’ enzyme catalyses oxidative cellulose conversion. Nature. 2025;639(8056):1076–1083. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08553-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang A. S. K., Kapat A., Schoenebeck F.. Factors That Control C–C Cleavage versus C–H Bond Hydroxylation in Copper-Catalyzed Oxidations of Ketones with O2 . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138(2):518–526. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami S., Gill K., Yin X., Swart M., Garcia-Bosch I.. Cu-Promoted ipso-Hydroxylation of sp2 Bonds with Concomitant Aromatic 1,2-Rearrangement Involving a Cu-oxyl-hydroxo Species. Inorg. Chem. 2024;63(43):20675–20688. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c03304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Span E. A., Suess D. L. M., Deller M. C., Britt R. D., Marletta M. A.. The Role of the Secondary Coordination Sphere in a Fungal Polysaccharide Monooxygenase. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017;12(4):1095–1103. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangasky J. A., Iavarone A. T., Marletta M. A.. Reactivity of O2 versus H2O2 with polysaccharide monooxygenases. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2018;115(19):4915–4920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1801153115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Li Z., Yu P., Shi H., Yang H., Yi J., Zhang Z., Duan X., Xie X., She X.. Construction of the Skeleton of Lucidumone. Org. Lett. 2022;24(30):5541–5545. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c02023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Zheng Z., Liu X., Zhang N., Choi S., He C., Dong G.. Asymmetric Total Synthesis of (+)-Phainanoid A and Biological Evaluation of the Natural Product and Its Synthetic Analogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023;145(8):4828–4852. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c13889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama Y., Maser M. R., Okita T., Dubrovskiy A. V., Campbell T. L., Reisman S. E.. Total Synthesis of Ritterazine B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143(11):4187–4192. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c01372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou W., Lin H., Wu Y., Li C., Chen J., Liu X.-Y., Qin Y.. Divergent and gram-scale syntheses of (−)-veratramine and (−)-cyclopamine. Nat. Commun. 2024;15(1):5332. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-49748-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Huang G., Wang Y., Gui J.. Asymmetric Total Synthesis of the Rearranged Steroid Phomarol Enabled by a Biomimetic SN2′ Cyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023;145(16):9354–9363. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c02817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Liu X., Zhang N., Choi S., Dong G.. Bidirectional Total Synthesis of Phainanoid A via Strategic Use of Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143(46):19311–19316. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c11117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wein L. A., Wurst K., Magauer T.. Total Synthesis and Late-Stage C–H Oxidations of ent-Trachylobane Natural Products. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022;61(3):e202113829. doi: 10.1002/anie.202113829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.-C., Chen C.-R., Chen C.-Y., Liang P.-H.. Synthesis of Quillaic Acid through Sustainable C–H Bond Activations. J. Org. Chem. 2024;89(8):5491–5497. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.3c02958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y., Karanjit S., Sato R., Namba K.. C(sp3)–H Oxidation of Spiroguanidine-Containing Cyclopentanes. J. Org. Chem. 2025;90(22):7428–7434. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5c00714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su B., Lee T., Hartwig J. F.. Iridium-Catalyzed, β-Selective C(sp3)–H Silylation of Aliphatic Amines To Form Silapyrrolidines and 1,2-Amino Alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140(51):18032–18038. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b10428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaget A., Mazet C.. Access to 1,2- and 1,3-Amino Alcohols via Cu-Catalyzed Enantioselective Borylations of Allylamines. Org. Lett. 2024;26(40):8542–8547. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.4c03170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrado M. L., Knaus T., Schwaneberg U., Mutti F. G.. High-Yield Synthesis of Enantiopure 1,2-Amino Alcohols from l-Phenylalanine via Linear and Divergent Enzymatic Cascades. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2022;26(7):2085–2095. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.1c00490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.-L., Hong K., Li T.-J., Park H., Yu J.-Q.. Functionalization of Csp3-H bonds using a transient directing group. Science. 2016;351(6270):252–256. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob C., Maes B. U. W., Evano G.. Transient Directing Groups in Metal–Organic Cooperative Catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 2021;27(56):13899–13952. doi: 10.1002/chem.202101598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John-Campbell S., Bull J. A.. Transient imines as ‘next generation’ directing groups for the catalytic functionalisation of C–H bonds in a single operation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018;16(25):4582–4595. doi: 10.1039/C8OB00926K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higham J. I., Bull J. A.. Transient imine directing groups for the C–H functionalisation of aldehydes, ketones and amines: an update 2018–2020. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020;18(37):7291–7315. doi: 10.1039/D0OB01587C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei M., Yi D., Meng F., Tang J., Zhang Y.. Copper-catalyzed aryl ortho-C–H thiolation of aldehydes via a transient directing group strategy. Organic Chemistry Frontiers. 2025;12:4780. doi: 10.1039/D5QO00472A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bontreger L. J., Gallo A. D., Moon J., Silinski P., Monson E. E., Franz K. J.. Intramolecular Histidine Cross-Links Formed via Copper-Catalyzed Oxidation of Histatin Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025;147(15):12749–12765. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5c01363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao D., Baidiuk A., Chaussy L., De Assis Modenez I., Ribas X., Réglier M., Martin-Diaconescu V., Nava P., Simaan A. J., Martinez A.. et al. Light-Induced Reactivity Switch at O2–Activating Bioinspired Copper(I) Complexes. JACS Au. 2024;4(5):1966–1974. doi: 10.1021/jacsau.4c00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C.-Y., Ohashi M., Le J., Chen P.-P., Zhou Q., Qu S., Bat-Erdene U., Hematian S., Rodriguez J. A., Houk K. N.. et al. Copper-dependent halogenase catalyses unactivated C–H bond functionalization. Nature. 2025;638(8049):126–132. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08362-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipouros I., Lim H., Appel M. J., Meier K. K., Hedman B., Hodgson K. O., Bertozzi C. R., Solomon E. I.. Mechanism of O2 Activation and Cysteine Oxidation by the Unusual Mononuclear Cu(I) Active Site of the Formylglycine-Generating Enzyme. ACS Central Science. 2025;11(5):683–693. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.5c00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]