Abstract

The growing application of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) in consumer, healthcare, and industrial products has raised concern over potential health implications due to increasing exposure. The evaluation of the immune response to nanomaterials is one of the key criteria to assess their biocompatibility. There are well-recognized sex-based differences in innate and adaptive immune responses. However, there is limited information available using human models. The aim was to investigate the potential sex-based differences in immune functions after exposure to AgNPs using human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and plasma from healthy donors. These functions include inflammasome activation, cytokine expression, leukocyte proliferation, chemotaxis, plasma coagulation, and complement activation. AgNPs were characterized by dynamic light scattering and transmission electron microscopy. Inflammasome activation by AgNPs was measured after 6- and 24-hours incubations. AgNPs-induced inflammasome activation was significantly higher in the females, especially for the 6-hour exposure. No sex-based differences were observed for Ag ions controls. Younger donors exhibited significantly more inflammasome activation than older donors after 24-hours exposure. IL-10 was significantly suppressed in males and females after exposure. AgNPs suppressed leukocyte proliferation similarly in males and females. No chemoattractant effects, no alterations in plasma coagulation, or activation of the complement were observed after AgNPs exposure. In conclusion, the results highlight that there are distinct sex-based differences in inflammasome activation after exposure to AgNPs in human PBMCs. The results highlight the importance of considering sex-based differences in inflammasome activation induced by exposure to AgNPs in any future biocompatibility assessment for products containing AgNPs.

Keywords: Inflammasome, Immunotoxicity, silver nanoparticles, sex-based difference, peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Introduction

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have been used in various consumer, healthcare, and industrial products due mostly to their anti-microbial properties (Royce et al., 2014, Ferdous and Nemmar, 2020). Among these products, AgNPs have been used in food containers, toothbrushes, bandages, and dental implants, which present a higher risk of translocation of AgNPs and Ag ions into the body (von Goetz et al., 2013, Mackevica et al., 2017, Ninan et al., 2020). With the growing application and exposure to AgNPs, there is a need to evaluate the potential safety hazards associated with short-term and long-term exposures, which have been reviewed and highlighted in various reports (Xu et al., 2020). For example, AgNPs have been reported to cause DNA damage, oxidative stress, and inflammation (Kim et al., 2009, Khan et al., 2019, Nallanthighal et al., 2017). The cytotoxicity and proinflammatory properties of AgNPs have been attributed to the dissociation into Ag ions, which has been reported to be directly correlated with the size of AgNPs, with smaller sizes dissociating more than larger sizes (Mishra et al., 2016, Zhang et al., 2011).

Sex-based differences in the innate and adaptive immunity have garnered increased importance due to the observed differences in genetic, inflammatory, autoimmune, and infectious diseases (Zychlinsky Scharff et al., 2019, Chamekh and Casimir, 2019, Pratap et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2021a). The sex hormones estrogen and testosterone have been associated with some of the observed differences in immune response (Luczak and Leinwand, 2009, Kovats, 2015). Emerging evidence has also indicated sex-based differences in immune response to nanomaterials. After intraperitoneal injection, gold nanoparticles caused higher liver toxicities and upregulated red and white blood cell counts in male mice compared to female mice while female mice showed an increased spleen index and markers for kidney damage compared to male mice (Chen et al., 2013). After oropharyngeal aspiration, nickel nanoparticles induced more lung inflammation in male mice than in female mice (You et al., 2020). Another study showed that male and female mice presented different immune response patterns after short term and chronic exposure, including differences in cytokine production, neutrophil recruitment, and lung pathologies, when exposed to multiwalled carbon nanotubes and crystalline silica (Ray and Holian, 2019). These reports of sex-based differences in immune response to different nanomaterials emphasize the importance of further investigations into other commonly used nanomaterials, such as AgNPs.

To date, the majority of investigations of sex-based differences in the biological response to AgNPs have been performed in mouse and rat models. AgNPs can adversely affect both male and female reproductive systems through alteration in spermatogenesis in male mice and endometrial receptivity in female mice (Fathi et al., 2019, Ajdary et al., 2021). Male and female rats presented slight liver toxicity after an oral treatment with 60 nm AgNPs, while more accumulation of the particles was observed in the female kidneys (Kim et al., 2008). Kidney and lung accumulation of 20 nm AgNPs was observed more in female mice after intravenous injection (Xue et al., 2012). Daily gavage of rats with 10, 75, and 110 nm AgNPs showed that smaller sized AgNPs absorbed more readily into tissues with the female rats showing more accumulation in the kidney, liver, jejunum, and colon than the male rats (Boudreau et al., 2016). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were found to be higher in the liver and lung of female mice and glutathione was found to be higher in the lung and brain of male mice upon exposure to 10 nm AgNPs (Tariba Lovaković et al., 2021). Oral treatment with AgNPs highlighted that there was similar hepatotoxicity in male and female mice (Heydrnejad et al., 2015). Female rats had more upregulated tight junction mRNA expression and TNF-α than male rats after oral gavage with 18 – 30 nm AgNPs (Orr et al., 2019). Oral gavage with 10, 75, and 110 nm AgNPs in rats showed size dependent sex-based differences in antibacterial activity, bacterial population, and gene expression in the intestinal tract (Williams et al., 2015). An ex vivo human study using excised human ileum tissue exposed to AgNPs showed that males had more upregulation in genes related to epithelial permeability than females, but the trends observed for the chemokines and cytokines were not found to be significant (Gokulan et al., 2020).

The inflammasome is an important part of the innate immune system, which recognizes various pathogen-associated molecular patterns and damage-associated molecular patterns and also promotes the formation of the multi-protein inflammasome complex (Jo et al., 2016). The formation of the inflammasome complex ultimately activates caspase-1 and leads to the maturation and secretion of IL-1β. Inflammasome activity can either play a protective role to promote host defense response or promote various diseases, such as cancer and metabolic and inflammatory disease through dysregulation (Zhen and Zhang, 2019, Sharma and Kanneganti, 2021). Nanoparticles, such as silica and titanium oxide, have been shown to activate the inflammasome through the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) pathway (Gómez et al., 2017, Kolling et al., 2020). The unintentional inflammasome activation by nanoparticles could potentially result in excessive IL-1β, leading to proinflammatory conditions (Silva et al., 2017). Experimental evaluation of nanoparticle-induced inflammasome activation is generally performed using a two-step process: priming, followed by activation (De Nardo and Latz, 2013). However, depending on the cell model utilized, the necessity of the priming step is still under debate (Gritsenko et al., 2020). Monocytes play an important role as one of the first immune responders to potentially harmful stimuli and AgNPs have been reported to activate the inflammasome in the monocytic cell line THP-1 and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Murphy et al., 2016); however, the sex-based differences in inflammasome activation induced by AgNPs has not been evaluated.

Investigating other innate immune functions is important when evaluating nanoparticles. Leukocyte proliferation occurs in response to antigens or mitogens exposure, which is important for host response to pathogens and infections (Datta and Sarvetnick, 2009). Dysregulation of the mitogen-induced leukocyte proliferation processes has been shown with gold and silver nanoparticles, indicating potential immunosuppressive properties (Devanabanda et al., 2016). Chemotaxis is the unidirectional migration of motile cells, such as immune cells, to chemoattractant chemicals or stimuli (Stock and Baker, 2009). Nanoparticles, such as gold nanoparticles, have the potential to influence the motility of immune cells either by presenting chemoattractant or chemorepellent properties (Zhang et al., 2021b). Coagulation, or clotting, occurs during vascular injury and prevents excess bleeding, and dysregulation of this process could have beneficial or adverse effects (Palta et al., 2014). Different formulations of the nanoparticles, such as liposomes, dendrimers, and metal, have been shown to either stimulate coagulation or deplete coagulation factors, thereby hindering coagulant activity (Ilinskaya and Dobrovolskaia, 2013). The complement cascade is activated to protect from infection and inflammation through immune cell recruitment and enhancing phagocytic activity of immune cells (Nesargikar et al., 2012). Similarly, exposure to nanomaterials has been linked to increasing hypersensitivity reactions through the activation of the complement (Szebeni, 2014). The potential of nanoparticles interference in these innate immune functions could potentially lead to dysregulation and potential health risks.

As previously noted, the availability of data from human models are very limited for sex-based differences in immune response to AgNPs. In this study, we aimed to provide ex vivo data to evaluate the effects of AgNPs on immune cell function and compare differences in responses between males and females. We investigated sex-based differences in inflammasome activation, cytokine expression, leukocyte proliferation, chemotaxis, plasma coagulation, and complement activation after exposure to 30 nm AgNPs using human PBMCs and plasmas from healthy donors. The inflammasome activity demonstrated distinct sex- and age-related differences, with the females presenting more inflammasome activation after AgNPs exposures. Ag ion controls did not present a difference in inflammasome activation suggesting that the sex-based differences observed in the inflammasome activation may be due to AgNPs interaction. Leukocyte proliferation was suppressed in females and males after phytohemagglutinin-M (PHA-M)-induced proliferation. AgNPs did not affect the chemotaxis, plasma coagulation, or complement activity. To our knowledge, this is the first report to show a sex-based difference in inflammasome activation by AgNPs.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and plasma

Human acute monocytic leukemia THP-1 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Human acute monocytic leukemia cells with deficient NLRP3 activity (THP-1defNLRP3) and human acute monocytic leukemia cells with deficient Caspase-1 activity (THP-1defCaspase-1) cell lines were purchased from InVivoGen (InVivoGen, San Diego, CA). The selective antibiotic Hygromycin B Gold (InVivoGen) was added at 200 µg/mL to every other passage of the deficient THP-1 cells to maintain the selection pressure. PBMCs from 14 male and 15 female healthy donors were obtained from the healthy donor inventory of Precision for Medicine (Frederick, MD) from donors ages 20 – 54 years old and were stored in liquid nitrogen upon receipt. THP-1 and PBMCs were cultured in complete RPMI-1640 media (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) containing 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (FBS; ATCC) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA). After thawing, the PBMCs were rested for a minimum of 20 hours prior to experimentation. Cells were maintained and all exposures were conducted in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Fresh frozen pooled plasmas with citrate were obtained from Precision for Medicine, one pooled from 3 male and one pooled from 3 female healthy donors. Frozen plasmas were gently thawed on ice prior to experimentation.

Nanoparticle Characterization

Citrate coated, 30 nm AgNPs (nanoComposix, San Diego, CA) were sonicated for 10 minutes in a water bath sonicator (Branson Ultrasonics 5510, Danbury, CT) at 40 kHz prior to characterization or treatment. The average hydrodynamic size was measured using dynamic light scattering (DLS) and the zeta potential was measured using a Malvern Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The sonicated AgNPs were diluted by adding 10 µL of the 1 mg/mL AgNPs to 990 µL of distilled water. Diluted samples were placed in a 4-mL polystyrene cuvette (Malvern) for DLS measurement and a 1 mL clear zeta potential cuvette (Malvern) for zeta potential analysis. Data were collected and determined using the Malvern Zetasizer software 7.13. AgNPs were analyzed for their primary size using a JEM-2100F transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Peabody, MA) after loading and drying onto carbon-coated nickel grid (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). The primary sizes were determined using the open-source ImageJ software.

AgNP dose formulations were prepared in 2 mM sodium citrate and used after sonication. For silica nanoparticles experiments, 20 nm NanoXact Silica Nanospheres (nanoComposix) were prepared in molecular grade water and were used for cell treatments following a 10-minute bath sonication.

Transmission electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

To identify silver within the samples, the cells were pelleted in agarose and then stained and embedded in Durcapan resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) following the established serial block face embedding procedure (Deerinck et al., 2022) with acetonitrile replacing ethanol through the dehydration series in that protocol. Once embedded, the samples were sectioned between 50–70 nm thick onto 200 mesh copper EM grids using a Leica EM UC6 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Deerfield, IL). The sections/grids were then carbon-coated on both sides using an Edwards Auto 306 carbon evaporator (Sanborn, NY) and the grids individually examined using a JEOL JEM-2100 electron microscope with an EM-24511SIOD bright field STEM (JEOL, Japan) and Oxford 80 T-MaxN energy-dispersive X-ray (EDS) detector (Oxford Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA.). To quickly determine if silver was present in the sample, the electron beam of the microscope was expanded over the cells being imaged and an EDS spectrum collected over that region. Once the presence of silver was confirmed, the JEM-2100 microscope was then placed in STEM mode (scanning transmission electron microscopy) which persistently scans and rescans the area, digitizing the image each time. Using this mode and persistently scanning the area of interest for 24 hours, the Oxford EDS detector was able to record and map the characteristic X-ray spectra from the elements present at each pixel in the sample using the Oxford Aztec software. The software was then used to compare and overlap the initial electron STEM image with the locations of the identified silver signal from the cells in that image. Specifically, the characteristic kα X-ray signal for silver, located at 22.166 keV, was mapped onto the electron image of the cell being examined.

Inflammasome activation

Inflammasome activation by AgNPs was investigated using THP-1, THP-1defCaspase-1, and THP-1defNLRP3 cells following established protocols (McNeil, 2011). THP-1 cells were plated at 40,000 cells/well with 50 nM phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA, Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 hours in a 96-well plate (Corning, Corning, NY). Cells were washed with media and treated with the 2 mM sodium citrate or 1, 10, or 30 µg/mL AgNPs for 24 hours after the PMA stimulation. Supernatants were collected for IL-1β ELISA analysis using an IL-1 beta/IL-1F2 DuoSet® ELISA kits (RND systems, Minneapolis, MN). Experiments were performed in triplicate for each treatment for each cell line.

For the evaluation of the inflammasome activation by AgNPs in PBMCs, cells were plated at 100,000 cells/well in a 96-well plate (Corning). Cells were primed using 200 ng/mL lipopolysaccharides (LPS, Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 hours. Cells without LPS priming were also prepared to serve as non-primed controls. The cells were then exposed to 2 mM sodium citrate or 1, 10, or 30 µg/mL AgNPs for 6 and 24 hours with and without the LPS priming.

Silica is a potent activator of inflammasomes in PBMCs (Gómez et al., 2017). Thus, positive controls were performed using 30 µg/mL NanoXact Silica Nanospheres to verify the inflammasome activity of the PBMCs. Ag ions were tested by using silver nitrate (AgNO3, Sigma-Aldrich). A stock of AgNO3 was prepared in molecular grade water (Corning). PBMCs were incubated with water or 1, 10, or 30 µg/mL Ag ions for 6 and 24 hours. After the exposures, the supernatants were collected for IL-1β analysis by using an IL-1 beta/IL-1F2 DuoSet® ELISA kits (RND systems). The AgNPs experiments were carried out using 6 donors per sex with n = 3 per treatment. The Ag ion experiments were performed using 3 donors per sex with n = 3 per treatment. Silica nano-sphere positive controls were collected from wells from 5 donors per sex.

The concentration of IL-1β in supernatant was measured following the manufacturer’s procedure. ELISA plates were prepared a day before supernatant collection using Nunc MaxiSorp™ flat-bottom 96-well plates (ThermoFisher) by incubating with 4 µg/mL capture antibody overnight at room temperature. Plate washing was conducted using filtered phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 0.05% Tween® 20 (Sigma-Aldrich). Plates were then blocked with reagent diluent (RND systems) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 hour. Plates were washed, and samples were loaded to plates for incubation at 4 °C overnight. After the overnight incubation, the plates were washed and 200 ng/mL detection antibody was added for 2 hours at room temperature. Plates were washed again and then a working solution of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was added to each well for 20 minutes at room temperature protected from light. After a final wash of the plates, 100 µL of a 1-Step™ Ultra TMB-ELISA solution (ThermoFisher) was added to each well for 20 minutes protected from light. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 µl of a 2 N sulfuric acid (H2SO4). Plates were read on a Synergy 4 microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT) using the Gen5 software 3.11 at 450 nm and reference at 540 nm. Data were fit to a four-parameter logistic (4PL) standard curve to determine the secreted IL-1β levels.

Cell viability

Cell viability was measured using a CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell density, media volume, and exposures were performed following the inflammasome activation experiment. THP-1 cells were exposed to the AgNPs for 24 hours, while the PBMCs were exposed to AgNPs for 6 and 24 hours. After the end of the incubation, plates were removed from the cell incubator and allowed to cool to room temperature. The plates were placed on a standard microplate vortex mixer (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 2 minutes at 250 x g after the addition of 100 µL of the CellTiter-Glo® reagent. The plates were allowed to incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature. The plates were then centrifuged in a Centrifuge 5430 R (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 20 minutes at 2000 x g to remove possible interference of larger nanoparticles aggregates prior to reading on a Synergy 4 microplate reader. Cell viability was calculated using the equation and data was represented as cell viability (% of control). THP-1 data were collected from n = 3 per treatment. PBMC data were collected from 3 donors per sex with n = 3 per treatment.

Cytokine secretion

Evaluation of the secretion of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 from PBMCs after AgNPs exposure was determined following the same procedure for the inflammasome activation using AgNPs with PBMCs. PBMCs were exposed to the AgNPs for 6 hours. Supernatants were collected and stored in a −80 °C freezer. The ELISA evaluation was carried out using the DuoSet® Human IL-6, DuoSet® Human TNF-α, and DuoSet® Human IL-10 (RND systems) following the manufacturer’s protocol similarly to the IL-1 beta/IL-1F2 DuoSet® ELISA kits used in the inflammasome activation experiments. Data were fit to a 4PL standard curve to determine the secreted IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 levels. Data were collected from 6 donors per sex with n = 3 for each treatment.

Leukocyte proliferation

Leukocyte proliferation was measured following the NCL Method ITA-6.3 (Potter et al., 2020). PBMCs were plated at 100,000 cells/well in a 96-well plate. The cells were treated with 2 mM sodium citrate, PBS (negative control), dexamethasone (positive control), or 1, 10, or 30 µg/mL AgNPs for 24 hours. After the 24-hour exposure, the cells were then supplemented with 10 µg/mL phytohemagglutinin-M (PHA-M) for 72 hours. Proliferation was assessed using a CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega), following a similar procedure stated in the cell viability experimental section. Plates were centrifuged for 20 minutes at 2000 x g to remove possible interference of larger nanoparticles aggregates prior to reading on a Synergy 4 microplate reader. Data were analyzed using the equation Data were normalized to the average VC % Proliferation to determine the fold proliferation induction. Data were collected from 5 donors per sex with n = 3 for each treatment.

Chemotaxis

The chemoattractant property of the AgNPs was investigated following the ASTM E3238–20 protocol with the modification for using the CellTiter-GLO® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (ASTM, E3238–20 2020). PBMCs were cultured in starvation media (SM, RPMI-1640 supplemented with 0.2% BSA, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate) for 18 hours. After measuring the cell viability using a Cellometer® K2 (Nexcelom, Lawrence, MA), a stock of the cells was prepared at 1 × 106 viable cells/mL by centrifugation and resuspended in SM. The chemotaxis experiment was performed using MultiScreen®-MIC plate (Millipore, Burlington, MA) consisting of a top filter plate and bottom feeding tray. The feeding tray was loaded with SM with a positive control of 20% FBS, a negative control using PBS, or 1, 10, or 30 µg/mL AgNPs. The filter tray was prepared by adding 50,000 cells in 50 µL into each well. An equivalent volume of the SM was added to the filter tray for the cell-free controls. The apparatus was assembled and placed into a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 4 hours. The filter tray was removed and 100 µL of the CellTiter-GLO® solution was added to each well. Samples were shaken at 250 x g for 2 minutes followed by a 10-minute incubation at room temperature. The solution from each well was transferred to a white, clear bottom 96-well plate. Plates were centrifuged for 20 minutes at 2000 x g and read using a Synergy 4 microplate reader. Sample fold chemotaxis induction was calculated by and data were presented as fold chemotaxis induction.

Plasma coagulation

Plasma coagulation, prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) were measured using the healthy donor pooled plasmas following the NCL Method ITA-12 (Cedrone et al., 2020). In brief, plasmas were incubated with 2 mM sodium citrate or 1, 10, or 30 µg/mL AgNPs for 1 hour at 37 °C. Coagulation times were measured using a BFT-II Analyzer (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). PT was measured by adding Dade® Innovin® reagent (Siemens) to the plasma and recording the coagulation time. aPTT was measured by incubating with Dade® Actin® FS Activated PTT reagent (Siemens) and adding calcium chloride solution (Siemens) to initiate the coagulation. The PT and aPTT of normal and abnormal control plasmas (Siemens) were measured before and after measuring the samples to validate the instrument accuracy.

Total complement activation

Complement activity was measured following the NCL Method ITA-5.1 (Neun et al., 2020). Plasma samples (10 µL) were incubated with 10 µL of veronal buffer (Boston Bioproducts, Milford, MA) and 10 µL of test samples consisting of PBS (negative control), cobra venom factor (CVF, Quidel, San Diego, CA), or 1, 10, or 30 µg/mL AgNPs for 30 minutes at 37 °C. Samples were resolved by running on a 4–15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE, BioRad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were transferred from the gels onto 0.2 µm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes contained in the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer Pack (BioRad) using a Trans-Blot® Turbo™ Transfer System (BioRad). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBS with 0.1% Tween®−20 (BioRad) for 1 hour. Intermittent washing between steps was performed using PBS with 0.1% Tween®20. Immunoblotting was conducted using Complement C3 Polyclonal Antibody (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) at 1:1000 in the blocking buffer for 1.5 hours to visualize the C3 cleavage products (~43 kDa). A secondary antibody incubation was carried out at 1:30,000 in blocking buffer using donkey anti-goat IgG (H + L) Secondary Antibody, HRP (Invitrogen) for 1.5 hours. Membranes were then incubated with Clarity™ Western ECL Substrate (BioRad) for 5 minutes. Membranes were visualized using a ChemiDoc™ Touch Imaging System (BioRad). Densitometry analysis of the blots was carried out using ImageJ by normalizing to the vehicle control.

Statistics

The statistical significance of the independent male and female experiments were determined using one-way ANOVA. The relationship between inflammasome activation fold values with independent variables Age, Sex, and Exposure levels across the 6- and 24-hour timepoints was investigated with a random effects model. An advantage of linear mixed effects models is that the mean response is modeled as a combination of subject-specific effects unique to an individual and fixed-effects shared by all individuals. In general, our regression model takes the following form:

The analysis of sex-based differences in the model was set up with male sex as the reference group. Age was set as a dichotomous variable with subjects less than 40 years old coded as the reference group. There were four levels of AgNPs exposure to include LPS, 1, 10, and 30 µg/mL AgNPs. These exposure levels were designed with LPS as the reference level. The model checked for interactions between exposure level, sex, and time. The regression coefficient, or estimate, refers to the estimated difference from the designated reference group. Statistical significance was defined at an alpha level of five percent (α ≤ 0.05).

Results

AgNPs Characterization and internalization

The characterization of the AgNPs was performed to determine their hydrodynamic size, zeta potential, and primary size. The hydrodynamic size was 32.80 ± 0.46 nm with a poly dispersion index of 0.134 (Figure 1A). The zeta potential of AgNPs was −25.5 mV (Figure 1B). The AgNPs presented a spherical size by TEM with an average primary size of 28.4 ± 4.9 nm (Figure 1C, D). The size distributions and charge were within the range reported by the supplier. Endotoxin levels were certified by the supplier to be below 2.5 EU/mL. In-house endotoxin measurements were in agreement.

Figure 1.

Physical characteristics and internalization of AgNPs. Hydrodynamic size and zeta potential was measured using a Malvern Zetasizer. (A) The hydrodynamic size was determined using DLS for the intensity and volume size distributions. Data were normalized to the peak size measured. Polydispersity index (PDI) is represented in the graph. (B) Zeta potential measurement was determined to be −25 mV. (C) Representative TEM image obtained using an EM-2100F transmission electron microscopy. (D) Size distribution analysis was performed using ImageJ. (E-H) Representative EDS data collected from male PBMCs and (I-L) representative data collected for female PBMCs exposed to 30 µg/ml AgNPs for 6 hours. (E, I) TEM images (F, J) EDS images of Ag represented in green. (G, K) Merged TEM and Ag EDS images. (H, L) EDS spectra.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and electron microscopy is a common technique used to detect and identify the locations of elements in samples observed by electron microscopy. By placing the instrument in STEM mode, images are recorded by scanning the specimen with a small electron probe rather than by a single wide beam. The scanning produces digitized images and with an X-ray detector on the microscope, the locations of elements can be easily mapped onto the recorded images. This is because using EDS in STEM mode records a complete spectrum of all the identifiable elements at each pixel in the image.

Using a single wide flood beam (regular imaging mode) in the microscope condensed over the area of interest of both male and female PBMC samples, the presence of trace amounts of silver was detected using EDS. The EDS spectra from both sets of samples, both male and female, indicated the abundant presence of osmium, uranium, lead, and arsenic which are components of the stains used to prepare the sample for microscopy. Iron is also a component of the staining protocol, but its presence was ignored because its presence could also be attributed by secondary signals generated by the microscope column. Silver was detected but in a trace amount. Because silver is not a component of the microscope, the signal generated from the sample can confidently be attributed to the AgNPs. Regular imaging mode was used to quickly assess the presence of silver and after confirming, STEM/EDS mapping for the elements present in the sample was performed.

Because silver was present only in small amounts, detecting silver in the cells was not definitive because the signal generated from 50–70 nm thick sections was not significant enough to produce a strong indication in the maps for the 1–4 hour EDS scans. These short scans were enough to show the locations of the EM stains on or in the cells but produced only noise for silver over the same areas of the cells. The only indication that silver might be present in these short scans came from a short silver peak that was identified by the software at 2.94 keV but that was too close to the uranium peak at 3.165 keV to be conclusive (left-most red arrow, Figure 1H and L). To boost the signal from these scans, scanning of the sections was performed for 24 hours. Scanning the same area over many iterations for 24 hours produced enough signal to show the locations of silver in both male and female embedded PBMCs. Though very small amounts were detected in the nuclei, most of the silver was located in the cytoplasm (Figure 1. Male: E–G, Female: I–K). Interestingly, the silver appeared to stain the surface of the cell only in the male sample (Figure 1F and G). The green arrow shown in the spectra of both male and female PBMC samples show the location and strength of the characteristic X-ray signal (22.166 keV) for silver that was used to map silver in the electron image. The silver maps show the same outline and features of the cells they were mapped from, indicating a good signal (Figure 1F and G). To rule out the possibility that these mapped features might be coming from secondary sources as accumulated noise, a brief scan of a small region of the sample where silver indicated a strong presence was compared to two background regions where mapping showed very little silver. The spectra of the silver region compared to the two background regions showed a strong silver signal in only the area identified as containing silver in the 24-hour scan (Supplemental Figure 1).

Inflammasome activity

THP-1, THP1-defCaspase 1, and THP1-defNLRP3 are typical models used for evaluating the ability of nanoparticles to induce inflammasome activation through the NLRP3 pathway (McNeil, 2011). The 50 nM PMA-stimulated control THP-1 cells exhibited a concentration-dependent upregulation of IL-1β after 1, 10, and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments (Supplemental Figure 2A). THP-1 cells deficient for Caspase 1 or NLRP3 did not exhibit discernable AgNPs-induced inflammasome activation. Significant cell death was observed for the THP-1 control and THP-1defNLRP3 cells with increasing AgNPs concentrations (Supplemental Figure 2B). Notably, the deficient cells had reduced cytotoxicity from the AgNPs treatments when compared to the nondeficient THP-1 cells, with the THP1-defCapsase1 cells exhibiting the least overall cell death with the AgNPs exposures as compared to the other cell lines tested.

Silica particles were used as a nano-based positive control for inflammasome activation to validate the ex vivo inflammasome activation model with the optimized priming conditions and to test the activity of the commercially purchased PBMCs (Supplemental Figure 3). Silica nanoparticles (SiNPs) have been shown to activate the inflammasome significantly after priming in PBMCs (Gómez et al., 2017). Both the male and female PBMCs presented a significant up-regulation of IL-1β secretion after exposure to 30 µg/mL of 20 nm silica nanospheres after 6 and 24 hours (Supplemental Figure 3A and B).

The AgNPs-induced inflammasome activation was evaluated in male and female PBMCs after 6- and 24-hour exposure periods. The ELISA data are depicted as a box and whisker plot to show the distributions of the average IL-1β expression (pg/mL) and the average fold increase of IL-1β for male and female donors (Figure 2). Individual ELISA experiments can be found in Supplemental Figure 4. The one-way ANOVA statistical analysis was performed on each sex independently, comparing to the average LPS priming for the average and fold change of IL-1β to determine if males or females had significant inflammasome activity after the AgNPs treatment. The broad distribution of the average IL-1β levels indicated that there was a high degree of variability between the donors (Figure 2A and C). Due to this variability, a fold change was performed to isolate the contribution of the AgNPs in the inflammasome activation (Figure 2B and D). Of note, the vehicle control and AgNP treatments without priming did not induce any inflammasome activation as indicated by not detectable IL-1β levels (data not shown for the AgNPs treatments without LPS priming). LPS priming controls upregulated IL-1β for all tested PBMCs to different degrees (Figure 2A and 2C). Male PBMCs only showed significant inflammasome activation for the 30 µg/mL AgNPs 6-hour exposure with an average 2.4-fold increase in IL-1β over the priming control (Figure 2B). Inflammasome activity from AgNPs treatments in males was not significant for the 24-hour exposure in the male PBMCs. Female PBMCs had a non-significant average 1.7- and 1.8-fold increase in IL-1β for the 1 and 10 µg/mL AgNPs treatments for the 6-hour exposure, respectively (Figure 2B). There was a significant average 7.3-fold increase in IL-1β for the 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatment for the 6-hour exposure (Figure 2B). Similar to the male PBMCs after 24-hours, AgNPs did not have a significant effect on inflammasome activation in females, with only a 1.4-, 1.1-, and 1.4-fold increase for the 1, 10, and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments, respectively (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Analysis of inflammasome induction by AgNPs using PBMCs from male and female donors. il-1β ELISA data obtained from the 6 male and 6 female experiments were consolidated to interpret sex-based differences in AgNPs on inflammasome activation in regard to exposure time and sex. PBMCs were primed with 200 ng/mL LPS for 4 hours prior to 6- and 24-hour AgNPs exposure. Supernatants were collected to measure the excreted IL-1β by ELISA. The average IL1-β levels of each individual ELISA are depicted in box-and-whisker plots for comparison. 2 mM sodium citrate is indicated by VC. (A) 6-hour exposure IL1-β (C) 24-hour exposure IL1-β. Data were normalized to the LPS priming controls to determine the effect of the AgNPs on inflammasome activation. (B) 6-hour exposure fold change (D) 24-hour exposure fold change. Data are depicted as the distribution of means for the 6 donor experiments per sex (n = 4 for each treatment). The ‘+’ represents the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001 versus LPS priming controls by one-way ANOVA.

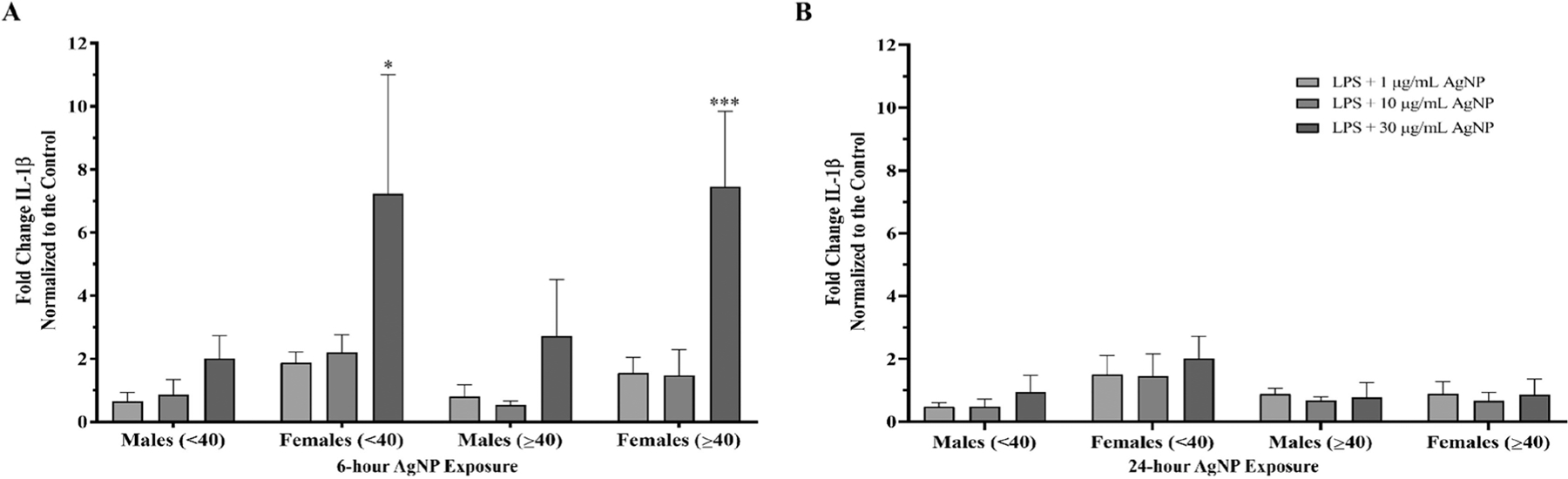

Further analysis of the data was performed by comparing two different age groups within the tested individuals: young (<40 years old) and old (≥40 years old) (Figure 3). Both male age groups exhibited inflammasome activity for the 6-hour 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatment, where there was a non-significant average 2.0- and 2.7-fold increase in inflammasome activity in the young and old males, respectively. The female PBMCs showed an average 1.9-, 2.2-, and 7.2-fold increase in the younger age group and 1.6-, 1.5-, and 7.5-fold increase in the older group in IL-1β for the 1, 10, and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments after the 6-hour exposure, respectively (Figure 3A). The young and old female age groups exhibited significant inflammasome activation for the 6-hour exposure to 30 µg/mL AgNPs. For the 24-hour exposure, younger and older male PBMCs did not show any significant inflammasome activation after exposure to AgNPs. The younger female age group continued to have sustained but not significant inflammasome activation with an average 1.5-, 1.4-, and 2.0-fold increase in IL-1β for the 1, 10, and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments, respectively, while the older female age group showed a non-significant 1.4-, 0.7-, and 0.9-fold change, respectively (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Sex and age analysis of AgNPs induced inflammasome activation in PBMCs from male and female donors. IL-1β data from the 6 male and 6 female donors was divided into distinct age ranges, n = 3 independent experiments for each age group. Data was normalized to the LPS priming controls to determine the effect of the AgNPs on inflammasome activation. (A) 6-hour AgNPs exposure. (B) 24-hours AgNPs exposure. Data are presented as means ± S.D. *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.0005 versus LPS priming controls by one-way ANOVA.

The baseline IL-1β resulting from LPS priming was higher in males compared to females, especially in the 6-hour experiments (Figure 2A and C). To evaluate if there were significant sex-based differences in inflammasome activation by AgNPs, the data were further analyzed through applying a mixed effects model as described in equation 1 (EQ1). We accounted for between-subject correlation and initially intended to account for within-subject correlation across the repeated measures at the 6- and 24-hour marks but discovered a significant interaction between exposure levels and time as reported by the model’s Type 3 tests for fixed effects (F3,42 = 17.34, p < 0.0001). Due to this significant interaction, we stratified the model on time, eliminating this variable from the model, creating two separate models one for each timepoint. Therefore, we no longer have a single longitudinal model that accounts for within-subject correlation, but two separate regression models for the fold values. The statistically significant result for each model is reported in Table 1. The 6-hour time point results show that female PBMCs are estimated to have 1.8-fold more inflammasome activation than male PBMCs when controlling for Age and Exposure. There is also a significant difference between 30 µg/mL AgNPs exposure compared to the LPS control baseline at the 6-hour measurement time. Overall, inflammasome activation was reduced after the 24-hour exposure. Female PBMCs were estimated to have 0.4-fold more inflammasome activation than male PBMCs when controlling for Age and Exposure. It was also found that the PBMCs from donors ages <40 have statistically more inflammasome activation than the PBMCs from donors ages ≥40 for the 24-hour exposure.

Table 1.

Statistically modeled results from the fold-change analysis obtained from male and female inflammasome activation by AgNPs.

| Independent Factors | Levels | Estimate | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-Hour Statistical Results | |||

| Age Groupsa | ≥40 | −0.5254 | 0.9047 |

| Sexb | Female | 1.7985 | 0.0002 |

| Silver Exposurec | 1 µg/mL AgNP | 0.1726 | 0.7809 |

| 10 µg/mL AgNP | 0.2668 | 0.6650 | |

| 30 µg/mL AgNP | 3.8516 | <.0001 | |

| 24-Hour Statistical Results | |||

| Age Groupsa | ≥40 | −0.2724 | 0.0441 |

| Sexb | Female | 0.3658 | 0.0080 |

| Silver Exposurec | 1 µg/mL AgNP | −0.08921 | 0.6368 |

| 10 µg/mL AgNP | −0.1841 | 0.3210 | |

| 30 µg/mL AgNP | 0.1710 | 0.3561 | |

The <40 years of age category is the baseline comparison group.

Male is the baseline comparison group.

LPS is the baseline comparison exposure.

Statistically significant results are indicated with bold text in the p value column.

Cell viability

The cytotoxic effects of the AgNPs were measured to evaluate the cell viabilities present in the experimental procedures. The cell viability of PBMCs was determined for 1, 10, and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments with and without LPS priming using a luminescent ATP assay (Figure 4). The 6-hour exposure to the AgNPs treatments did not induce cytotoxicity, with cell viabilities remaining above 95% (Figure 4A). Notably, the male PBMCs did have statistically significant cytotoxicity for the LPS-primed 10 and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments after 6 hours exhibiting 87% and 72% cell viability, respectively (Figure 4B). In contrast, the female PBMCs did not have significant cell death with cell viabilities of 99% and 89% for the same concentrations. Cytotoxicity was determined not to be significant with the 24-hour AgNPs treatments with a similar concentration-dependent trend of cytotoxicity observed for both sexes. The 10 and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments showed 89% and 76% cell viability for the male PBMCs and 88% and 73% for the female PBMCs without the LPS priming (Figure 4C). The primed PBMCs treated with 10 and 30 µg/mL AgNPs for 24 hours showed 86% and 80% cell viability for the male PBMCs and 89% and 83% for the female PBMCs (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Cell viability of PBMCs from male and female donors with and without LPS and AgNPs exposure. The cell viability of PBMCs with and without a 4-hour 200 ng/mL LPS priming followed by 6- and 24-hours of AgNPs exposure was measured using a CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay. The % cell viability was calculated against the 2 mM sodium citrate vehicle control, VC. Data are presented as means ± S.D (n = 3 for each stimulant). (A) 6-hour AgNPs exposure. (B) LPS + 6-hours AgNPs exposure. (C) 24-hour AgNPs exposure. (B) LPS + 24-hours AgNPs exposure. **p < 0.01 and ****p < 0.0001 versus vehicle controls by one-way ANOVA.

Ag ions

The dissolution of AgNPs to release Ag ions (Ag+) is one of the methods by which AgNPs have been shown to induce inflammasome activation and cytotoxicity (Gliga et al., 2014, Simard et al., 2015). To investigate the contribution of Ag+ on the observed sex-based differences in inflammasome activation in this study, PBMCs from 3 male and 3 female donors were treated with 1, 10, or 30 µg/mL Ag+ for 6 hours. Individual donor results are shown in Supplemental Figure 5. The parameters were chosen to emulate the AgNPs inflammasome experiments assuming 100% dissolution condition. Inflammasome activity was observed to be highest with the 6-hour exposure time for the AgNPs; thus, PBMCs were treated with Ag+ for a similar period. The 1 µg/mL Ag+ treatment did not induce inflammasome activity when compared to the LPS priming control. The 10 and 30 µg/mL Ag+ treatments induced the inflammasome activity, where male PBMCs showed a 10.7- and 7.7-fold increase and female PBMCs showed a 11.8- and 6.9-fold increase in IL-1β, respectively (Figure 5A and B). Significant cell death was also observed with the 10 and 30 µg/mL Ag+ treatments. The male PBMCs had 22% and female PBMCs had 13% cell viability in the 10 µg/mL Ag+ treatments. The 30 µg/mL Ag+ treatment resulted in over 95% cell death in both sexes (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Silver ions cause significant inflammasome activation and cell death in PBMCs. Ag ions (Ag+) was added to the plates after a 4-hour 200 ng/mL LPS priming for a period of 6-hours. (A) Supernatant levels of IL-1β after 6-hours of Ag+. (B) Means were normalized to the LPS priming controls to distinguish Ag+ contribution to the inflammasome activation. (C) Cell viability after 6-hour exposure to Ag+ was determined by an CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay. The % cell viability was calculated against the untreated cells. Data are presented as means ± S.D from 3 donor experiments per sex (n = 3 for each treatment). 2 mM sodium citrate is indicated by VC. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001 versus the LPS for the inflammasome activation and vs the vehicle controls for the cell viability by one-way ANOVA.

IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 secretion

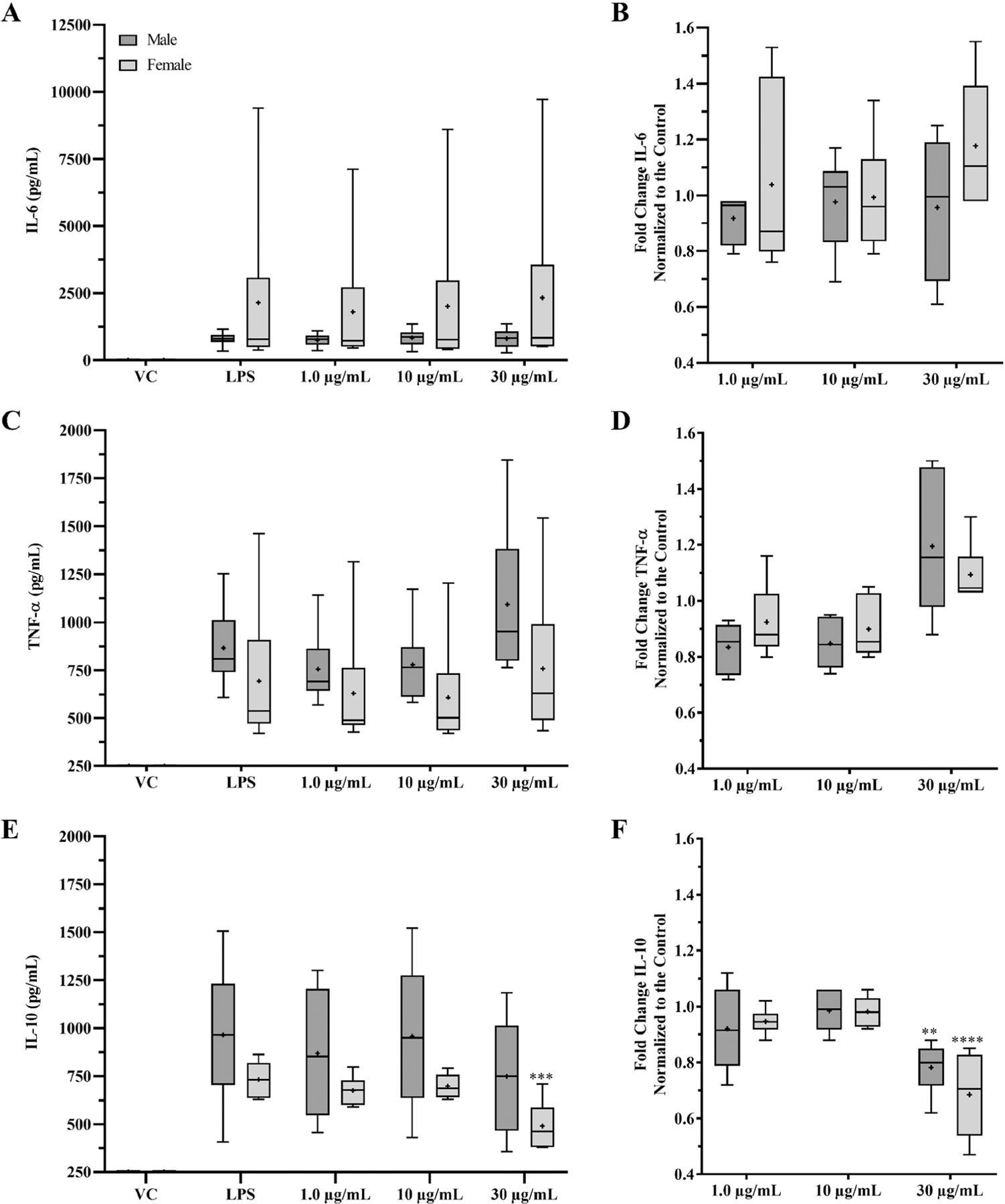

IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 secretion following AgNPs exposure was evaluated in male and female PBMCs after 6 hours of incubation. The ELISA data are depicted as a box and whisker plot to show the distributions of the average IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 secretion (pg/mL) and the average fold increase of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 for each individual male and female (Figure 6). Individual ELISA experiments can be found in Supplemental Figure 6. The one-way ANOVA statistical analysis was performed on the male and females independently for each ELISA. The vehicle control and AgNPs treated without LPS supernatants did not show measurable levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 within the detection limits (Data not shown). Again, there is a high degree of variability between the donors primed with LPS, so the fold change was performed to isolate the contribution of the AgNPs. LPS priming controls upregulated the IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 for all tested PBMCs to different degrees.

Figure 6.

Analysis of cytokine induction by AgNPs using PBMCs from male and female donors. IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 ELISA data obtained from the 6 male and 6 female experiments were consolidated to interpret sex-based differences in AgNPs on cytokine secretion in regard to exposure and sex. Except for the vehicle control, VC, PBMCs were primed with 200 ng/mL LPS for 4-hours prior to 6-hour AgNPs exposure. Supernatants were collected to measure the excreted IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 by ELISA. The average IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 levels of each individual ELISA are depicted in box-and-whisker plots for comparison (A) IL-6 secretion. (C) TNF-α secretion. (E) IL-10 secretion. Data were normalized to the LPS priming controls to determine the effect of the AgNPs. (B) IL-6 fold change. (D) TNF-α fold change. (F) IL-10 fold change. Data are shown as the distribution of means for the 6 doner experiments per sex (n = 3 for each treatment). 2 mM sodium citrate is indicated by VC. The ‘+’ represents the mean. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0005, and ****p < 0.0001 versus LPS priming controls by one-way ANOVA.

Male and female PBMCs did not show a significant change with IL-6 or TNF-α after AgNPs exposure (Figure 6B and D). The male PBMCs did not show an increase over the LPS for the IL-6 with the folds being between 0.9 and 1.0 (Figure 6B). There was a 0.83-, 0.85-, and 1.20-fold change with the TNF-α for the 1, 10, and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments, respectively (Figure 6D). Females presented a 1.04-, 0.98-, and 1.18-fold change in IL-6 and a 0.92-, 0.90-, and 1.10-fold change in TNF-α for the 1, 10, and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments, respectively (Figure 6B and 6D). IL-10 presented a significant decrease for both the male and female PBMCs with the 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments (Figure 6F). The female PBMCs were also significantly lower in overall secretion of IL-10 when compared to the LPS control (Figure 6E). The fold change for the male IL-10 was 0.92-, 0.98-, and 0.78-fold while the female PBMCs was 0.95-, 0.98-, and 0.69-fold for the 1, 10, and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments, respectively (Figure 6F).

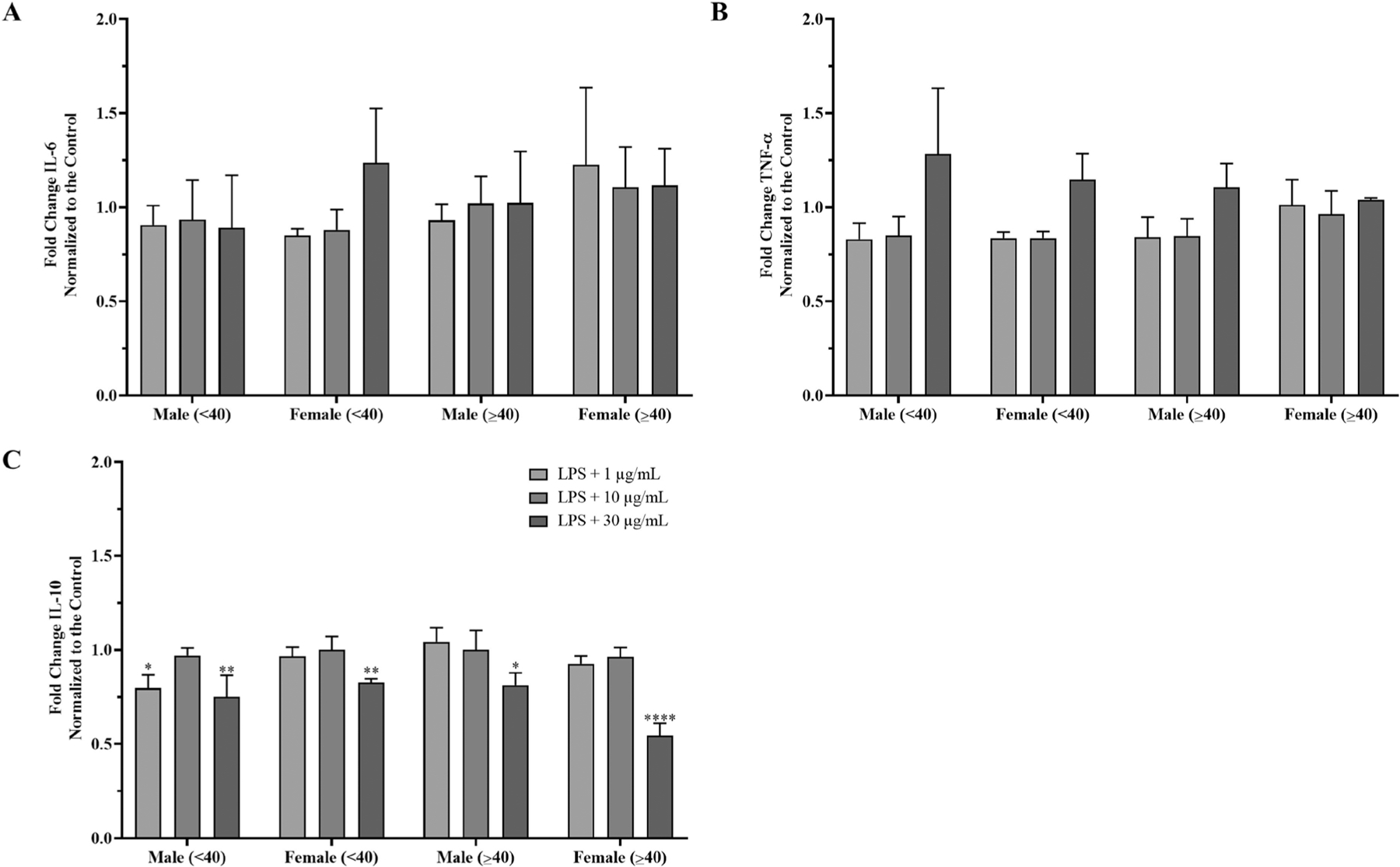

The PBMC data were divided into two groups under the age <40 (young) and over the age of ≥40 (old), to determine the effects of age. The fold changes vs the LPS control are reported for the 1, 10, and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments. There were no significant changes in IL-6 and TNF-α in male and female PBMCs for each age range (Figure 7A and B). The young male group treated with 1, 10, or 30 µg/mL AgNPs presented a 0.91-, 0.93-, and 0.89-fold change for IL-6 and 0.83-, 0.85-, and 1.28-fold change for TNF-α, respectively. The old male group presented a 0.93-, 1.02-, and 1.02-fold change for the IL-6 and 0.84-, 0.85-, and 1.11-fold change for the TNF-α, respectively. The young female group presented a 0.85-, 0.86-, and 1.24-fold change for IL-6 and 1.23-, 1.11-, and 1.12-fold change for TNF-α, respectively. The old female group presented a 0.93-, 1.02-, and 1.02-fold change for the IL-6 and 1.01-, 0.96-, and 1.04-fold change for the TNF-α, respectively. The IL-10 did show a significant reduction with the 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatment for both males and females (Figure 7C). The young males showed a 0.80-, 0.97-, and 0.75-fold change and the old males showed a 1.05-, 1.00-, and 0.81-fold change in IL-10, respectively. The young females showed a 0.97-, 1.00-, 0.83-fold change and the old females showed a 0.92-, 0.96-, and 0.55-fold change in IL-10, respectively. The old females had statistically more reduction in IL-10 for the 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatment than the young females.

Figure 7.

Sex and age analysis of AgNPs induced cytokine secretion in PBMCs from male and female donors. IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 data from the 6 male and 6 female donors were divided into distinct age ranges, n = 3 independent experiments for each age group. Data were normalized to the LPS priming controls to determine the effect of the AgNPs. (A) IL-6 fold change. (B) TNF-α fold change. (C) IL-10 fold change. Data are presented as means ± S.D (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001 versus LPS priming controls by one-way ANOVA.

Utilizing a similar regression model from the inflammasome activation analysis, no sex-based or age-based differences were determined with the 6-hour fold data. When controlling for both sex and age, there were significant alterations in the fold change of TNF-α and IL-10 secretion following the AgNPs exposure in both male and females (Table 2). Data are represented as the fold change compared to the LPS controls to isolate the effects from AgNPs. For the TNF-α, the 1 and 10 µg/mL AgNPs treatments showed a significant down regulation while there was a significant upregulation with the 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments. The 1 and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments significantly reduced the IL-10 secretion.

Table 2.

Statistically modeled results obtained from the fold-change analysis of the male and female cytokine secretion during inflammasome activation by 6-hour AgNPs exposure.

| Independent Factors | Levels | Estimate | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 Statistical Results | |||

| Age Groupsa | ≥40 | 0.06453 | 0.1236 |

| Sexb | Female | 0.05860 | 0.1617 |

| Silver Exposurec | 1 µg/mL AgNP | −0.00031 | 0.9957 |

| 10 µg/mL AgNP | −0.00065 | 0.9912 | |

| 30 µg/mL AgNP | 0.08389 | 0.1567 | |

| TNF-α Statistical Results | |||

| Age Groupsa | ≥40 | −0.02916 | 0.3755 |

| Sexb | Female | −0.02204 | 0.5027 |

| Silver Exposurec | 1 µg/mL AgNP | −0.1001 | 0.0326 |

| 10 µg/mL AgNP | −0.1040 | 0.0265 | |

| 30 µg/mL AgNP | 0.1702 | 0.0003 | |

| IL-10 Statistical Results | |||

| Age Groupsa | ≥40 | 0.001422 | 0.9418 |

| Sexb | Female | −0.01494 | 0.4433 |

| Silver Exposurec | 1 µg/mL AgNP | −0.06688 | 0.0159 |

| 10 µg/mL AgNP | −0.02507 | 0.3651 | |

| 30 µg/mL AgNP | −0.2658 | <.0001 | |

The <40 years of age category is the baseline comparison group.

Male is the baseline comparison group.

LPS is the baseline comparison exposure.

Statistically significant results are indicated with bold text in the p value column.

Leukocyte proliferation

Leukocyte proliferation is also an important parameter to determine if nanomaterials can be an immunomodulator by acting as an immunostimulant (increase proliferation) or an immunosuppressive (inhibit proliferation) (Dobrovolskaia and McNeil, 2013). To measure the effect of AgNPs on leukocyte proliferation, male and female PBMCs were treated with AgNPs for 24 hours followed by a mitogen PHA-M-induced proliferation for 72 hours. The fold proliferation induction for each sex is shown in Figure 8. Independent proliferation experiments are depicted in Supplemental Figure 7. The PBMCs used in the experiment exhibited a large degree of variability in leukocyte proliferation with varying responses to the PHA-M stimulation. The proliferation was calculated against the untreated PBMCs without PHA-M, which represents 0% proliferation (baseline). To reduce the variability and isolate treatment associated effects to the proliferation, data was then normalized to the PBMCs treated with only PHA-M (100% proliferation response). The PHA-M-stimulated PBMCs represent the maximum proliferation that can occur with the PBMCs without other stimulants. The vehicle control did not affect the proliferation for either male or female PBMCs. The AgNPs suppressed the leukocyte proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner. The 1 µg/mL AgNPs suppressed proliferation in both male and female PBMCs, but this decrease was not significant. Leukocyte proliferation was suppressed significantly for the 10 and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments, with male PBMCs having 0.34- and 0.04-fold proliferation induction and females having 0.19- and −0.03-fold proliferation induction when compared to the PBMCs without PHA-M, respectively. Interestingly, the male PBMCs demonstrated more tolerance to the higher concentrations of AgNPs with only one of the six male donors exhibiting a complete inhibition of the PHA-M-induced proliferation (Supplemental Figure 7A). For the female PBMCs, two females out of six exhibited a complete inhibition of the leukocyte proliferation for the 10 and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments. Total inhibition was also observed in one of the six females for only the 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatment (Supplemental Figure 7B). The other studied female PBMCs maintained the ability to proliferate against the AgNPs, albeit they were significantly decreased. Due to the variability in the rate of proliferation, the error does not allow for distinguishing whether there is a pattern for sex-based differences in the current experiment.

Figure 8.

AgNPs exposure can inhibit leukocyte proliferation in PBMCs. PBMCs from 6 male and 6 female donors were exposed to AgNPs for 24 hours followed by stimulation with 10 µg/mL PHA-M for 72 hours. Total inhibition of proliferation was measured in cells treated with 250 μg/mL dexamethasone (PC). 2 mM sodium citrate is indicated by VC. Data are presented as means ± S.D from 6 donors per sex (n = 3 for each treatment). **p < 0.01 and ****p < 0.0001 versus PHA-M controls by one-way ANOVA.

Chemotaxis

The recruitment of immune cells by chemotaxis plays a significant role in immune response, which could be directly affected by immunomodulators, including nanomaterials that have been reported to have chemoattractant or chemorepellent properties (Zhang et al., 2021b). The chemoattractant property was evaluated in male and female PBMCs incubated with 1, 10, or 30 µg/ml AgNPs (Figure 9). FBS was used as a positive control (PC), which showed a significant migration of PBMCs from both male and female donors, without a significant sex-based difference. The AgNPs did not induce PBMC migration for either the male or female PBMCs. Notably, the male PBMCs had a significant decrease in migration in the 30 µg/mL AgNPs exposure when compared to the negative control (NC).

Figure 9.

AgNPs Chemoattractant properties. Chemotaxis was performed on PBMCs from male and female donors. PBMCs were incubated with starvation media for 18 hours prior to measuring their migration capacity through a 3 µm multi-screen filter plate with a feeder tray supplemented with FBS (positive control (PC)), PBS (negative control (NC)), 2 nm sodium citrate (vehicle control (VC)) and 1, 10 and 10 µg/ml AgNPs treatments. Total cell migration was determined using a CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay after 4-hours. Data are presented as means ± S.D (3 donors per sex with 3 independent experiments, n = 3 per treatment). *p < 0.05 versus NC by one-way ANOVA.

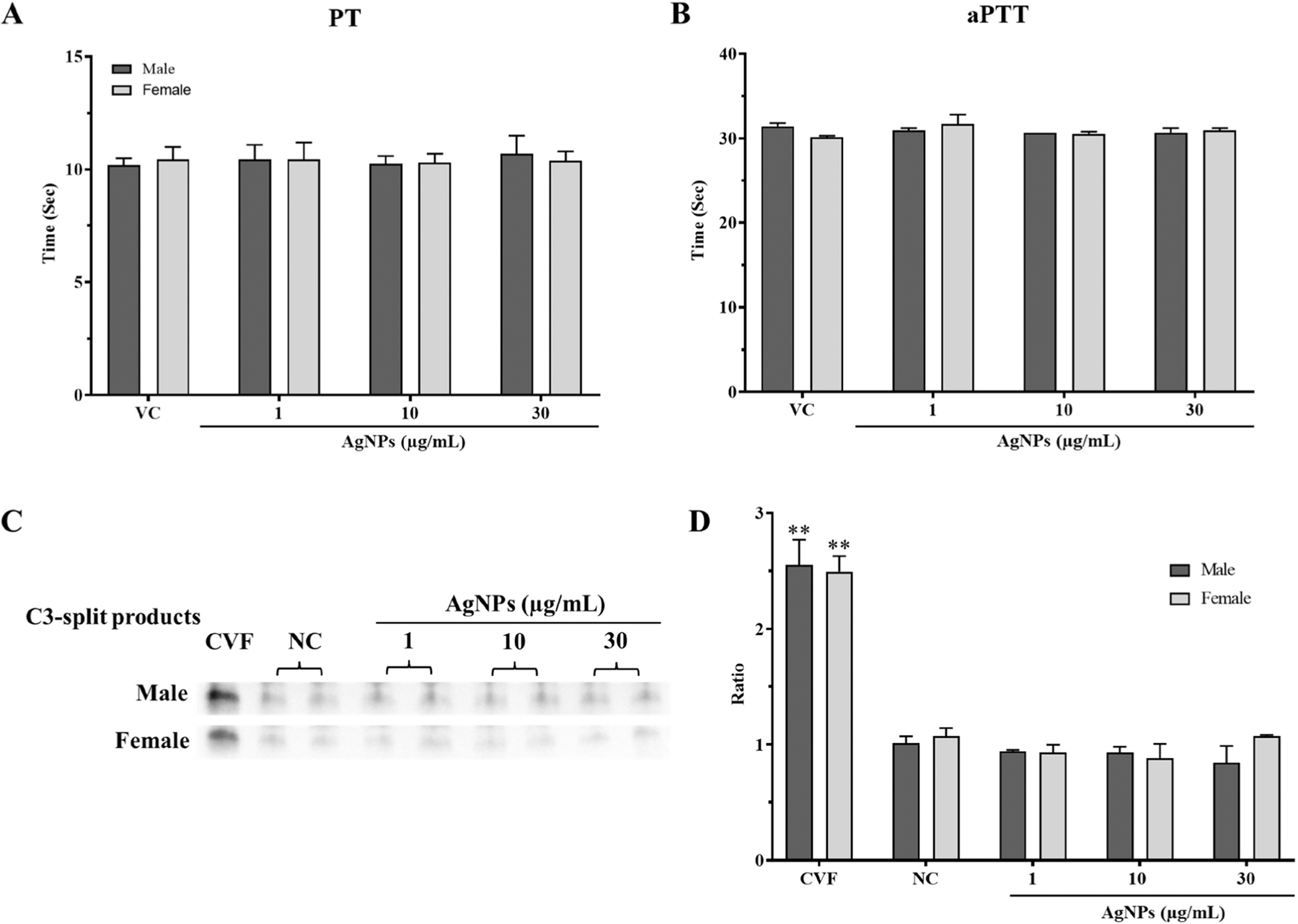

Plasma coagulation

PT and aPTT of the healthy control plasma were determined to be 9.9 seconds and 28.1 seconds, respectively. The PT and aPTT of the abnormal control plasma were 19.3 seconds and 59.2 seconds, respectively. The control plasmas were within the manufacturer’s reported range. The effect of AgNPs on the PT and aPTT was investigated using male and female pooled plasmas from healthy donors (Figure 10A and 10B). The PT of the male and female pooled plasmas were not affected by the 1, 10 and 30 µg/ml AgNPs treatments and were measured to be 11.2, 10.7, and 11.2 seconds for the male and 9.8, 9.9, and 10.0 seconds for the female, respectively (Figure 10A). Similarly, the aPTT of the male and female pooled plasmas were also not affected by the 1, 10 and 30 µg/ml AgNPs treatments and were measured to be 30.7, 30.5, and 30.5 seconds for the male and 32, 30.8, and 31.2 seconds for the female (Figure 10B). Increasing the treatment concentration to 50 µg/mL did not alter the PT or aPTT (data not shown).

Figure 10.

The effects of AgNPs exposure on plasma coagulation and complement activation for male and female pooled plasmas. Coagulation times were measured using fresh pooled plasmas after 1-hour exposure to AgNPs using a BFT-II coagulometer. (A) Prothrombin time (PT). (B) Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). Complement activation was determined by measuring the total C3-split product by Western blot. Pooled plasmas were incubated with AgNPs for 30 minutes. Cobra venom factor (CVF) was used as a positive control. (C) Representative blot for the C3-split product. (D) Densitometry analysis was performed using ImageJ analysis and depicted as a ratio to the negative control (NC). 2 mM sodium citrate is indicated by VC. Data are presented as means ± S.D (n = 3). **p < 0.01 versus controls by one-way ANOVA.

Complement activation

Complement activation includes three different pathways (classical, alternative, and lectin), all of which play an important role in amplifying the innate immune system for the defense against inflammation and infection by promoting recruitment of immune cells and promoting lysis of target cells (Nesargikar et al., 2012). Pooled plasmas from male and female donors were exposed to 1, 10, or 30 µg/ml AgNPs to assess their effects on the complement activation. Qualitative analysis of the total complement activation was measured by quantifying the C3-split products (Figure 10C, D). The positive control CVF presented a similar significant increase in the C3-split products for both the male and female pooled plasmas, indicating the activation of the complement. The male and female pooled plasmas did not show a significant increase in the C3-split products for 1, 10, and 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatments. Full representative membrane blots can be found in Supplemental Figure 8.

Discussion

This study investigated potential sex-based differences of AgNPs on immune functions using human PBMCs and plasmas from healthy male and female donors. Inflammasome activation, leukocyte proliferation, and chemotaxis experiments were performed using PBMCs. Coagulation and complement activation experiments were performed using fresh frozen pooled plasmas from healthy male and female donors. The inflammasome experiment demonstrated that PBMCs from female donors have more inflammasome activation induced by AgNPs than the PBMCs from male donors. AgNPs suppressed leukocyte proliferation, with no difference between sexes. AgNPs were not chemoattractant for PBMCs and did not modulate plasma coagulation or activate the complement for both males and females.

The average exposure to AgNPs is very difficult to determine due to its incorporation into many consumer and industrial products and taking in consideration various exposures including occupational, environmental, dietary intake, and other consumer products. There are very few human studies for the occupational exposure to AgNPs. It has been reviewed that occupational exposure can range between 0.02 − 1.35 µg/mL (Weldon et al., 2016). One case study using a AgNPs containing wound dressing for a burn patient showed that silver plasma levels could reach up to 107 µg/kg after 7 days of wound treatment (Trop et al., 2006). Similarly, it has been estimated that dietary intake of silver can range between 0.4 – 27 µg/day with an absorption rate ranging up to 18% (Hadrup and Lam, 2014). However, data is limited for distinguishing ionic and nano forms of silver when considering oral exposure. For example, the migration of AgNPs vs ionic silver from food contact materials is limited and is subject to the type of material that AgNPs have been incorporated into and the properties of the food (von Goetz et al., 2013, Kraśniewska et al., 2020). When considering this variation, our study was conducted using various concentrations of AgNPs that reflect other studies which have used exposure concentrations from 0.15 – 100 µg/mL to study the toxicological effects on human monocytes and PBMCs (David et al., 2020, Murphy et al., 2016, Yang et al., 2012). Although the treatments can be considered high, the treatment concentrations used in in vitro studies reflect years of exposure or acute incidental exposure to AgNPs.

The inflammasome plays an important role in innate immune system against pathogens or stressors, which in turn promote the maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 for tailoring downstream immune responses (Schroder and Tschopp, 2010). Nanoparticles have been shown to activate the inflammasome via the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway (Gómez et al., 2017, Kolling et al., 2020, McNeil, 2011). The mechanism for NLRP3 activation is still under debate and may include ionic influx, ROS production, and lysosomal damage (Kelley et al., 2019). THP-1 cells are typically used as a model for evaluating nanoparticle-induced inflammasome activation (Gabor, 2011). Therefore, THP-1 cells were used to verify the effectiveness of the AgNPs to activate the inflammasome. Previous studies have reported that AgNPs induce inflammasome activation in THP-1 cells after PMA priming, with upregulation of the caspase 1 activity and IL-1β (David et al., 2020, Traore et al., 2005). Our current study achieved similar upregulation in the inflammasome activation with the PMA-primed THP-1 cells and expanded on these findings using THP-1 cells deficient of Caspase 1 and NLRP3, which provided further confirmation to the inflammasome activation pathway for the AgNPs. The deficient THP-1 cell lines showed a complete inability to promote the inflammasome activation by AgNP treatments. Interestingly, the deficient cell lines presented lower percentage of cytotoxicity compared to the control cell line. Inflammasome activation has been linked to causing pyroptosis, caspase 1-dependent programed cell death, through membrane disruption by caspase 1 activity and pore formation (Fink and Cookson, 2006). Inflammasome activation by 15 nm AgNPs can induce pyroptosis in THP-1 cells via the upregulation of caspase 1 and caspase 4, which cause endoplasmic reticulum stress (Simard et al., 2015). Thus, the decreased ability of the AgNPs to induce inflammasome activity could be a potential explanation for the decreased cytotoxicity in the THP1-deficient cell lines.

The use of PBMCs in the investigations of nanoparticles-induced inflammasome activation studies is limited. PBMCs are a heterogenous population of nucleated blood cells that consist of lymphocytes (70–90%), monocytes (10–20%), and dendritic cells (1–2%) (Kleiveland, 2015). PBMCs and blood have been recognized as beneficial models for inflammasome activation studies due to having less modulation during isolation processes and representing the diverse cell populations within the microenvironment the nanoparticles will be introduced to when present in blood circulation (Tran et al., 2019, Gritsenko et al., 2020). Thus, PBMCs were chosen as the model to compare the sex-based differences to reflect the diverse interactions that are caused by exposure to AgNPs. A wide range of LPS priming concentrations for inflammasome studies has been reported (Yang et al., 2012, Murphy et al., 2016, Ghonime et al., 2014). Recently, LPS has been shown to activate the inflammasome through an alternative pathway without the need for a second stimulation of PBMCs (Gaidt et al., 2016). The LPS priming concentration used in this study was optimized to achieve a measurable baseline of IL-1β that would allow for the comparison of the change in IL-1β levels caused by exposure to AgNPs. Hence, a baseline IL-1β was observed in both the male and female PBMCs following the LPS priming. The PBMCs in our study did not show a measurable level of IL-1β without priming. To distinguish the AgNPs contribution to the activation of the inflammasome, the stimulation of IL-1β from the LPS alone was used for the baseline comparison. There is a wide range of exposure periods to nanomaterials for inflammasome investigation for in vitro experiments that can range from as short as 4 hours to up to 24 hours (Zhu et al., 2020, Yang et al., 2012, Gómez et al., 2017). The minimum exposure period was chosen based on an optimization experiment and it was found that the 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatment presented the highest increase in IL-1β secretion after 5–6 hours (data not shown). The 24-hour exposure period was chosen to allow the PBMCs to fully interact and resolve inflammasome activation by the AgNPs.

It has been reported that AgNPs were primarily accumulated in the monocytes, rather than the lymphocytes (Greulich et al., 2011). AgNPs have been shown to activate the inflammasome in monocytes in a size-dependent manner. One report compared 5 nm, 28 nm, and 100 nm AgNPs and the smaller AgNPs presented more toxicity and inflammasome activation in THP-1 and PBMCs (Murphy et al., 2016). This size-dependent toxicity and increased inflammasome activation was linked also to increased lysosomal membrane permeabilization caused by Ag ion release from the low lysosomal pH in HepG2 cells after uptake (Mishra et al., 2016). Smaller AgNPs have also been shown to release more Ag ions over a period of time than larger AgNPs (Zhang et al., 2011). AgNPs alone were not able to induce any inflammasome activity, supporting that the priming step is essential for the PBMCs used in the study. The 30 nm AgNPs used in this study were able to promote inflammasome activation in the female PBMCs. Sustained inflammasome activity was also still observed in the female PBMCs from donors under the age of 40 after 24 hours of exposure. The male PBMCs did not show AgNPs-induced inflammasome activation for the lower treatment concentrations. Interestingly, the male PBMCs only showed upregulation of the IL-1β with the 30 µg/mL AgNPs treatment for the 6-hour exposure. The male PBMCs did show a higher base-line level of IL-1β for the LPS priming control. Male immune cells have been reported to express more TLR4, which would allow for greater response to the LPS priming (Klein and Flanagan, 2016). Pre-exposure to sex-hormones could possibly explain some differences observed. Estrogen has been reported to activate and enhance the NLRP3 inflammasome activity (Liu et al., 2019, Chen et al., 2020). Loss of testosterone has been reported to exacerbate inflammasome activity, suggesting it plays an inhibitory role (Chen et al., 2020). Testosterone has also been reported to decrease TLR4 expression (Rettew et al., 2008). Further investigations and experimental work will be needed to elucidate the underlying mechanism for this observed difference.

Ag ions are linked to the potential toxicity of AgNPs. Storage of the AgNPs is also a factor that can affect the dissociation and biological effects (Izak-Nau et al., 2015). AgNPs were properly stored and used before the manufacturer’s storage guideline, however, it cannot be ruled out that dissociation of the stock AgNPs can occur. Citrate-stabilized AgNPs have been shown to release less Ag ions when compared to polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-coated AgNPs over a 24-hour period (Kittler et al., 2010). Citrate-coated AgNPs showed less than 20% dissolution in a variety of synthetic biological fluids under 24 hours, where it was found that dissolution was greatest in fluids with the highest acidity and ionic strength (Mbanga et al., 2022). Thus, we chose the citrate-coated AgNPs to test the real contribution of the nanoparticles for the inflammasome induction and limit the Ag ion-associated cytotoxicity and inflammasome induction. Although the actual ionization rate of the AgNPs was not measured in this study, analysis of the Ag ions assuming 100% dissolution with the inflammasome treatments was performed. The results of our study showed that there was similar significant inflammasome activation with the 10 and 30 µg/mL Ag ion treatments for both the male and female PBMCs. The 1 µg/mL Ag ion treatment did not stimulate the inflammasome activity at 6-hours. However, after the 24-hour exposure, the 1 µg/mL Ag ion treatment did stimulate the inflammasome activity (data not shown). The cytotoxicity was also significant for the 10 and 30 µg/mL Ag ion treatments, but not for the 1 µg/mL Ag ion treatment. These results are in agreement with a similar report demonstrating the extreme cytotoxicity of the Ag ions (Kaplan et al., 2016). This also suggests that ionization of the AgNPs in the study was not significant since the percent cytotoxicity with AgNPs was not as significant as the percent cytotoxicity associated with the Ag ions. Notably, the male PBMCs did show more inflammasome activation from the Ag ions when compared to the AgNPs treatments. This suggests that the sex differences seen in inflammasome activity may also be due to variations in the interaction with the AgNPs. The EDS results showed that AgNPs were internalized by the PBMCs, but extensive testing of multiple donors will still be needed to elucidate if there are differences in uptake between male and female PBMCs. It has been reported that sex can be a factor in the uptake of nanoparticles in human amniotic stem cells, which may be due to (i) variations in secreted biomolecules (i.e., paracrine factors) and/or (ii) sex-based variation of cell functions and structures (e.g., various membrane composition and intracellular pathways and, also, cell stiffness, i.e., structural differences in their cytoskeleton) (Serpooshan et al., 2018). The differences in biodistribution of the AgNPs after treatment also highlight the differences in cellular interaction to the AgNPs in male and female models (Kim et al., 2008, Boudreau et al., 2016). The low pH of phagolysosomal fluid has been reported to increase the dissolution of AgNPs (Mbanga et al., 2022, Mishra et al., 2016). Therefore, it is possible that the AgNPs are not as readily up taken into the male PBMCs. It must be noted that the Ag ions were treated with a 6-hour exposure time, which would be different from how the AgNPs interact with the cells. It has been reported that uptake of Ag ions from AgNO3 is significantly faster than AgNPs at low concentrations in PBMCs over a 24-hour period (Pourhoseini et al., 2021). One soil invertebrate model also demonstrated that AgNO3 treatment could produce oxidative stress faster than AgNPs (Ribeiro et al., 2015). It would be beneficial to investigate the differences in the male and female PBMC endocytosis of the AgNPs to determine the mechanisms for the possible differences observed.

AgNP treatments alone did not affect the IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 secretion in the PBMCs, but the stimulation with LPS followed by AgNPs exposure did have a significant effect on TNF-α and IL-10. Although no sex-based differences were observed from fold analysis of the cytokines, the data provide more insight on pro-inflammatory risks associated to AgNPs exposure to PBMCs. The pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α was both significantly reduced for the 1 and 10 µg/mL treatments and increased for the 30 µg/mL treatment. In the literature, variations in the expression of TNF-α from AgNPs exposures varies. LPS priming followed by exposure to AgNPs in THP-1 differentiated macrophages resulted in the upregulation of IL-6 and TNF-α through the production of ROS and upregulation of Stat3 (Yusuf and Casey, 2019). It has also been reported that the mRNA expression of IL-6 and TNF-α is upregulated in THP-1 cells and primary monocytes following AgNPs exposure, with the co-stimulation with LPS enhancing this upregulation (Murphy et al., 2016). Experiments using whole blood from healthy human subjects demonstrated increased levels of TNF-α following LPS and AgNPs exposure (Galbiati et al., 2018). LPS priming increased IL-10 levels and sub-sequent AgNPs treatment significantly decreased IL-10. IL-10 plays an important role as an anti-inflammatory cytokine that is expressed to limit pro-inflammatory responses in order to maintain homeostasis (Ng et al., 2013). Thus, the suppression of the IL-10 by the AgNPs may contribute to prolonged inflammatory conditions. Rats treated daily for 28-days with AgNPs showed a decreased expression of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 in isolated LPS-stimulated spleen cells (De Jong et al., 2013). Similar reductions in TNF-α and IL-10 were found in PBMCs from healthy donors treated with 10 and 20 nm AgNPs for 24 hours with LPS (David et al., 2020).

Leukocyte proliferation in both male and female PBMCs was similarly suppressed by AgNPs. In our study, five of the male PBMCs maintained the ability to proliferate under the PHA-M stimulation when exposed up to 30 µg/mL AgNPs. Three of the female PBMCs showed similar trends to the male PBMCs, but three of the female PBMCs presented a significant suppression/inhibition of proliferation. To date, there are no studies that directly investigate the differences in male and female leukocyte proliferation after AgNPs exposure. However, it has been shown that a 1.3 nm nano-silver colloidal solution and 20 nm citrate- and PVP-stabilized AgNPs were able to suppress significantly PHA-induced proliferation of PBMCs (Shin et al., 2007, Huang et al., 2016). The results of our study are in agreement to these prior reports and support that the AgNPs suppress the leukocyte proliferation in PBMCs.

The studied AgNPs were not a chemoattractant to the PBMCs from either male or female donors. To date, no studies have reported the chemoattractant properties of AgNPs against PBMCs; however, AgNPs have been shown to modulate the expression of chemoattractant proteins in cells. AgNPs have been shown to upregulate the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) gene in metabolic syndrome model mice (Alqahtani, 2020). AgNPs can also upregulate Keratinocyte Chemoattractant (KC) in rat broncho-alveolar lavage fluid (Seiffert et al., 2015). Future studies are warranted to investigate the sex-based differences on how AgNPs could modulate the chemotaxis in the immune cells.

Coagulation tests were performed using fresh frozen plasmas from healthy donors. Fresh frozen plasmas have been reported to have negligible effects on coagulation factors (Feng et al., 2014). The 30 nm citrate stabilized AgNPs used in this study did not affect the PT and aPTT values in either males or females. The results are supported by previous studies that investigated the effect of AgNPs on plasma coagulation. One investigation demonstrated that 20 nm citrate- and PVP-stabilized AgNPs did not alter PT, aPTT, or thrombin time (TT) values in healthy plasma (Huang et al., 2016). In this report, only concentrations >212 µg/mL of the citrate-stabilized AgNPs were able to increase aPTT values. Similarly, another study reported that 24 nm AgNPs could only moderately increase aPTT at 1078 µg/mL (Martínez-Gutierrez et al., 2012). A 600 µg/kg injection of 90 nm PVP-stabilized AgNPs did not affect PT or aPTT values in plasma isolated from mice after 1 hour exposure (Wu et al., 2020). Taken together, only extreme levels of AgNPs can moderately affect aPTT, but in general AgNPs do not seem to affect PT or aPTT values in male and female plasmas. The leukocytes procoagulant activity after AgNPs treatment will need to be explored to determine if AgNPs could affect the plasma coagulation by modulation of the leukocytes.

Sex and age have been reported to affect complement activation (Gaya da Costa et al., 2018). The complement is a major component of the innate immune system that serves as one of the first lines of defense against pathogens (Merle et al., 2015). In general, nanoparticles activation of the complement is seen as an undesirable outcome that could lead to proinflammatory response and disease progression (La-Beck et al., 2020). There are limited investigations that study the effect of the AgNPs on the complement. Our study demonstrated that the 30 nm AgNPs did not affect the complement activity within the studied concentration range in either male or female pooled plasmas. Similarly, complement activation was not observed after exposure to 20 nm citrate- and PVP-stabilized AgNPs at concentrations up to 40 µg/mL on healthy pooled plasma (Huang et al., 2016).