Abstract

-

»

Psychological factors significantly influence both the risk and recovery process of sports injuries, with inadequate coping skills and high life stress levels identified as key preinjury risk factors.

-

»

Postinjury psychological distress, including symptoms of anger, depression, and anxiety, can hinder an athlete's rehabilitation and prolong recovery time.

-

»

Female athletes demonstrate a higher incidence of sports injuries and tend to experience more severe psychological responses after injury compared with male athletes.

-

»

Incorporating psychological support and interventions into rehabilitation programs improves outcomes and supports holistic recovery for injured athletes.

-

»

Recognizing and addressing mental health as a central component of injury management is essential for optimizing athlete well-being and performance.

An athlete is defined as an individual who participates in an organized team or individual sport that involves regular competition, places a high value on excellence and achievement, and requires systematic training1. Sports participation unquestionably offers myriad health and wellness benefits, but avoiding overlooking potential adverse outcomes is crucial2. Despite substantial progress in understanding and treating athletic injuries, concerns regarding the rise in sports injuries have been raised. This increase is attributed to psychological and sociocultural stressors such as anxiety, perfectionism, and social pressure3.

Internationally, athletes sustain approximately 4 million sports-related injuries annually, requiring approximately 2.6 million emergency department visits and costing approximately $2 billion4. During the 2020 Summer Olympics, a total of 1,035 injuries and 438 illnesses were reported, corresponding to 9.1 injuries and 3.9 illnesses per 100 athletes5.

Adverse events sports participants endure include not only physical injuries but also negative outcomes impacting their physical and mental health, which may be influenced by associated risk factors6. The relationship between sports injuries and mental health is bidirectional, highlighting that the comprehensive impact injury has on athletes7. For example, mental health disorders, particularly depression, are more prevalent among athletes than in the general population8. Concussions and head impacts have been linked to depressive symptoms, and overtraining syndrome can mimic depression9. Furthermore, depressive symptoms have been linked to involuntary retirement due to injuries, particularly when athletes experience ongoing pain and possess a strong athletic identity10. Many athletes who sustain physical injuries concurrently experience psychological distress manifested as anxiety, negative mood, fear of reinjury, or loss of motivation11. Depressive symptoms can lead to physiological and attention-related changes, thereby increasing the risk of musculoskeletal injuries12.

A comprehensive understanding of the psychological impact of sports injuries on athletes will enable relevant stakeholders, including healthcare professionals, coaches, and physiotherapists, to proactively address and improve both physical and psychological recovery13. This underscores the need to fully understand the intricate web of consequences of athletic injuries, particularly their intersection with mental health issues. To our knowledge, no review article has thoroughly examined the bidirectional relationship between sports injuries and mental health. This review aimed to provide an in-depth assessment of the psychological impact of sports injuries, focusing on both preinjury and postinjury measures and emphasizing the role of mental health in the recovery process.

Methods

Literature Search

Medline/PubMed, Google Scholar, Education Resources Information Center, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were searched for relevant studies on September 7, 2023. The following keywords were used: “athletes,” “athletic injuries,” “impact,” and “mental health.”

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The retrieved records were initially assessed based on their titles. All included studies were rescreened by the researchers using the full-text articles. The inclusion criteria were all types of studies that addressed athletes who had any form of sports injury and its impact on athletes' mental health or well-being, as well as studies that investigated the psychological factors contributing to sports injuries. Studies exploring the influence of psychological factors during rehabilitation were also included. Studies that focused on interventions or treatments without discussing the psychological impact of the injury itself were excluded. Studies published in languages other than English, book chapters, and critiques were also excluded.

Data Extraction

A standardized extraction form was used to extract data from the articles. The extracted information included the primary author's last name, year of publication, location (city or country), sample size, and significant conclusions. All authors participated in the data extraction and review of studies.

Patient and Public Involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, or reporting of this research.

Results

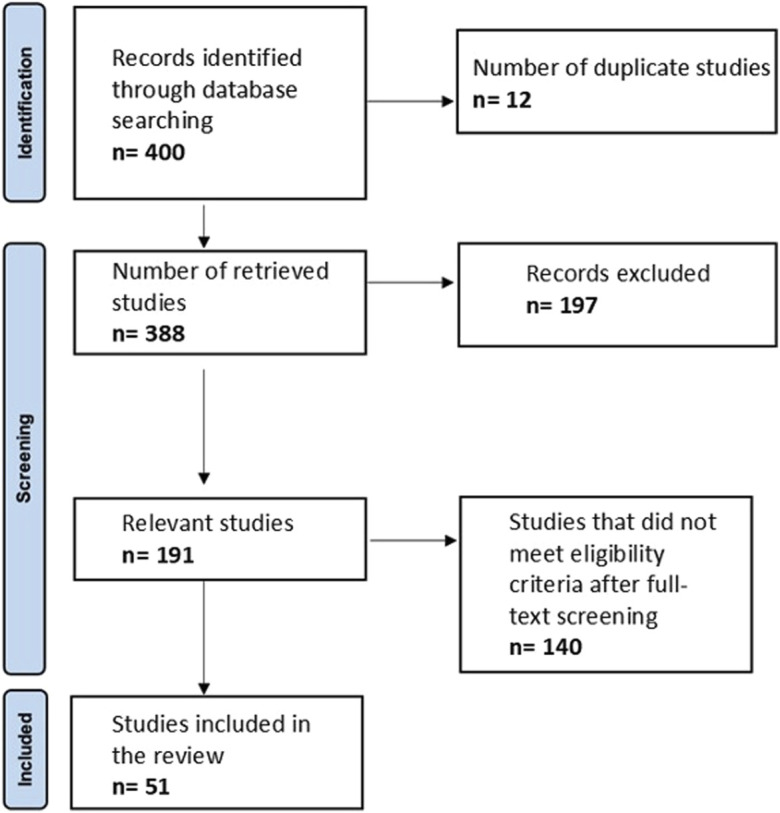

A total of 400 studies were identified. After removing duplicates, this number decreased to 388. The researchers conducted title screening to determine eligibility for inclusion. Studies deemed irrelevant or published in languages other than English were excluded, resulting in a final count of 191 studies. During eligibility screening, full-text articles of studies involving young and college athletes, as well as those primarily focusing on interventions or treatments without addressing the psychological impact of the injury itself, were excluded, leaving 51 studies for analysis (Fig. 1). Among the included studies, 15 discussed preinjury psychological factors, 25 focused on psychological distress after sports injuries, and 12 addressed the role of psychological factors in rehabilitation.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart summarizing the identification and selection of articles.

Discussion

Understanding sports injuries has evolved with methodological improvements in research design and measurements, shedding light on the significant role of psychosocial factors in injury risk and management. Despite having similar physical conditions and situations, athletes may vary in their susceptibility to injuries. Overtraining syndrome, commonly known as “burnout,” exemplifies the interaction of both physical and psychological symptoms14. Personality types have also been suggested as potential contributors to injury proneness, with stress and coping mechanisms playing crucial roles in sports injury outcomes12,14. Life stress is also associated with a higher likelihood of injury15.

Studies have revealed that inadequate coping resources are a strong predictor of injuries among athletes, emphasizing the importance of psychosocial support13. Furthermore, the relationships among social support, coping skills, and injury vulnerability underscore the nuanced nature of these interactions16. Among uninjured athletes, mood dimensions such as anger, confusion, fatigue, tension, uncertainty, stress, and depression have been identified as significant contributors to sports injuries17,18. Beyond the glory of success, elite athletes face darker consequences, including overtraining, burnout, and an increased risk of various noncardiovascular conditions. When disrupted, a high athletic identity is linked to psychological distress, overtraining, and burnout19,20. In addition, elite sports literature highlights vulnerabilities, such as disordered eating and risk-taking behaviors among athletes14. Therefore, injury is a continuum, beginning with preinjury stress responses and extending through acute sports injuries, influenced by personal and situational factors21.

Preinjury Psychological Models

Numerous models in the literature have highlighted the profound impact of psychological factors—such as stress levels, mood states, personality traits, and coping resources that can influence an athlete's susceptibility to injury22—during the preinjury phase. For instance, Andersen and Williams formulated a stress theory model, emphasizing athletes' responses to stressful situations as pivotal in injury likelihood22. Their model highlighted the predictive power of major life event stress on injury occurrence, particularly when combined with limited coping resources22. Similarly, Wiese-Bjornstal's comprehensive analysis of the current literature related to high-intensity athletes highlighted the significant role of psychological factors in shaping athletes' vulnerability and predisposition to injury, although the immediate cause often lies beyond psychological factors23. Galambos et al.16 reviewed annual health screening data from 845 athletes ranging in age from 11 to 41 years. Their report further elucidated the intricate connections between psychological factors and physiological states, shedding light on the complex interplay that shapes injury occurrence16. Moreover, the Wiese-Bjornstal model23 emphasizes the need to consider diverse elements, such as training protocols, body composition, and social pressures, to assess an athlete's injury risk profile, offering a holistic framework for injury prevention24.

During the Injury and Afterward

Sports hold a prominent position in society, not merely because of their widespread popularity but also because of their substantial health benefits. In recent decades, participation in master's sports has notably increased, with older adults engaging in organized athletic competition not only for physical health but also for social connection, self-expression, and to challenge age-related stereotypes25. Despite the myriad benefits that sports offer athletes, injuries remain a significant obstacle that many participants encounter. Sports-related injuries are on a sharp rise across various categories and modalities, a trend attributed to heightened professionalization, competitiveness, and extended practice sessions within the sporting realm26. Health-related issues pose a recurrent challenge for athletes, given their frequent exposure to physically and psychologically demanding circumstances. Notably, although the detrimental effects of elite sports are often overshadowed, recent evidence suggests that elite athletes frequently report mental health issues throughout their careers27. In their study among 1,401 professional football athletes (current and retired), those with hip osteoarthritis (OA) scored significantly lower in health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The pivotal role of psychological processes in both the occurrence of and recovery from injuries has been well established. This has prompted an increased emphasis on elite athletes' mental well-being28-31, including interventions rooted in sports psychology32. Careful consideration of the timing, nature, providers, and framing of psychological interventions can help ensure that the interests of athletes with injuries are best served33.

Mental health is a crucial determinant of athletic performance and progression. Simultaneously, athletes face unique mental health risk factors compared with the nonathletic population, including intense training regimes, competitive pressures, and the demanding nature of their lifestyles. The physical demands of sports, including rigorous training and injury risks, can precipitate various psychological effects. These effects can affect cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains21. Certain injuries and medical conditions may have detrimental effect in this population, as we discuss next.

Effect of Medical Conditions/Physical Injury

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are considered debilitating. They can have long-term adverse consequences, including reduced physical activity, disability, increased risk of knee OA, and poor perceived knee-related quality of life (QoL). Psychological impairments during ACL injury rehabilitation may include frustration, lack of motivation, fear of reinjury, loss of athletic identity, anxiety, and disordered eating. These psychological factors may culminate in serious physical consequences34.

Back pain is a prevalent health issue among athletes and is characterized by functional limitations and psychological strain. Its prevalence rates vary across different sports, ranging from 31% for soccer to 89% in divers30. In their review, they noted the scarcity of back pain studies that include psychological aspects other than stress.

Concussion is another injury athletes are at risk for, especially those engaged in contact and collision sports. These athletes have an elevated risk of concussion compared with the general population35. The increasing focus on concussions stems from the fact that brain injuries account for the highest rate of fatalities in sports. In addition, elevated rates of depression and suicide have been associated with athletes in sports such as American football, ice hockey, rugby, and soccer20. Athletes exhibiting an anxious profile at baseline are more likely to experience a greater symptom burden after a concussion36. Concussions are considered a factor that reduces QoL37.

Different sports are associated with different injury patterns. For example, basketball, a globally practiced team sport, exhibits an injury incidence of 71.3%. These injuries predominantly affect the lower limbs, thereby decreasing HRQoL across the physical and mental domains38. In football, injuries are more prevalent during matches, which are characterized by frequent physical contact. The ankle (25%) is the most commonly affected site, followed by the knee (20.1%)39. In a cross-sectional study of 270 athletes, Marshall et al.40 found that those with a history of severe ankle injuries had significantly lower functional (Foot and Ankle Ability Measure) and mental health (Short Form-12) scores compared with those with mild or no injuries, highlighting a lasting impact on HRQoL. Furthermore, football players are susceptible to degenerative bone diseases, with a reported prevalence of hip OA of 2% to 8% among former professional football players. Both current and former professional footballers with hip OA exhibited significantly lower levels of hip function, physical health, and HRQoL than those without hip OA or the control group27.

Sex-Specific Disparities

As the involvement of women in sports across all levels of proficiency and competition continues to grow, nuanced comprehension of the psychology specific to female athletes becomes essential. This understanding can aid in bolstering their athletic achievements, injury recovery, and enhancing overall health and wellness41. Male and female athletes exhibiting preseason anxiety symptoms were found to have 2.5 and 1.9 times higher injury rates, respectively42. Notably, female athletes engaging in sports and fitness activities have a 4 to 6 times higher incidence of knee injuries than their male counterparts. In addition to adversely affecting knee function, these injuries have negative repercussions on physical and emotional well-being, as well as vitality, social functioning, and QoL43,44. Granito45, in a study examining gender differences in psychological responses to athletic injury, found that female athletes not only viewed their coaches more negatively regarding postinjury treatment but also expressed greater emotional distress, lower perceived social support, and heightened concern about the long-term impact of their injury on future health and sports participation compared with their male counterparts. Factors such as social support, coping mechanisms, and cultural expectations may contribute to this discrepancy46. Female athletes tend to report lower scores than male athletes on various aspects of the Short Form-12, underscoring the necessity to consider sex when evaluating postinjury HRQoL40.

Psychological Distress and Disorders

Trauma-related mental-health disorders may manifest disproportionately among elite athletes, with prevalence rates potentially surpassing those in the general population47. Athletes may encounter traumatic experiences at various stages of their lives, including childhood, active sports participation, and throughout their athletic careers. Notably, rates of posttraumatic stress disorder among elite athletes may exceed those observed in the general population. Certain sports demonstrate even higher prevalence rates, with rates of up to 25% among professional and preprofessional dancers.

Upon reaching elite competition levels, athletes contemplating retirement are afforded the opportunity to develop and execute retirement plans. However, unforeseen retirements, often precipitated by career-ending injuries, can pose formidable challenges for athletes transitioning out of sports, affecting their physical, mental, and social well-being48. The peak age for the onset of mental health disorders among athletes coincides with their peak competitive years due to the intense mental and physical demands they endure20. Notably, 75% of all lifetime mental health conditions commence by the age of 24 years, aligning with the peak years of athletic performance10. The severity of the psychological response to an injury may vary, and not all cases result in a formal psychological diagnosis, such as depression34. Stress exhibits a robust association with sports injuries as a preinjury factor, with the immediate postinjury period often characterized by heightened anxiety, frustration, depression, and poor mood states10,49,50.

Previous studies involving athletes reported an annual incidence of sports injuries ranging from 65% to 75%51. When an injury occurs, the attributions athletes make regarding its cause can influence the rehabilitation and recovery processes20.

Sports Rehabilitation

Understanding the multidimensional emotional experiences athletes undergo during the injury recovery period is a critical priority in rehabilitation28. Smith et al. found that injured athletes experienced significantly higher levels of psychological symptoms, such as depression, tension, and confusion, indicating the need to address these issues during physiotherapy28. Physical therapists play an integral role in addressing the psychological aspects of injury recovery, highlighting the importance of integrating psychological factors into rehabilitation programs52. The Emotional Responses of Athletes to Injury Questionnaire serves as a valuable tool for assessing athlete emotions during rehabilitation and developing coping strategies53.

Sleep quality is the second most important determinant of athletes' likelihood of regaining full strength and maintaining mental stability54,55. Sleep disturbances can hinder recovery and affect mental status. Therefore, implementing sleep hygiene practices is essential to the rehabilitation process.

Management

Table I presents the different psychological management modalities used in sports rehabilitation. Evidence-based psychological treatments, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction training, acceptance and commitment training, and motivational enhancement training, offer promising avenues for psychological support for injured athletes56,57. Moreover, concrete, problem-focused, and behaviorally oriented programs that minimize uncertainty are considered ideal for injured athletes58. Notably, the literature has reported positive psychological reactions, such as increased motivation, confidence, and reduced fear, which are associated with a quicker return to previous sports performance levels59.

TABLE I.

Management Modalities in Sports Rehabilitation

| Management Modality | Brief Description |

|---|---|

| Mindfulness-based stress reduction training | Uses mindfulness meditation strategies, including breathing and cognitive techniques, to manage stress and regulate cognitive and emotional responses |

| Acceptance and commitment training | Employs mindfulness and committed action, based on core values rather than goals, to enhance psychological flexibility |

| Motivational enhancement training | Centered on motivational interviewing, aims to bolster personal motivation and commitment toward a specific goal by exploring individual reasons for change within a supportive and compassionate environment |

| Psychological support programs | Includes concrete, problem-focused, and behaviorally oriented programs to minimize uncertainty and enhance recovery |

| Social support | Involves collaboration among athletes, medical professionals, and coaches to provide a supportive environment |

Building a supportive environment with collaboration among athletes, medical professionals, and coaches is critical for successful rehabilitation60. Sports medicine professionals must understand the psychosocial principles underlying athletes' injury processes and their impact61. Social support is instrumental in helping athletes successfully handle the rehabilitation phase62. By integrating these techniques into rehabilitation plans, healthcare professionals can support athletes manage their emotional responses, improve mood self-efficacy, and foster a positive mindset for successful recovery and return to sports.

Preventive Measures

Table II lists some preventive techniques for sports injuries. Several studies have addressed various methods and techniques for preventing sports injuries. For instance, Ahern and Lohr14 advocated integrating cognitive techniques, such as positive self-talk, relaxation methods, and meditation, to mitigate the negative thoughts that may predispose athletes to injury risk14. Furthermore, the critical role of sleep in optimizing athletes' training, recovery, and performance cannot be overstated because it intricately influences both physiological and psychological processes55,63. In addition, Chan and Hagger conducted research on the transcontextual process of motivation between sports participation and sports injury prevention64. They surveyed 533 elite athletes participating in various sports at different levels, from regional to international. Their findings suggest that athletes exhibiting autonomous motivational orientations in sports are more inclined to engage in behaviors that prevent sports injuries64. Moreover, personality traits and coping resources have been identified as influential factors in sports injury risk. These factors affect injury outcomes both directly and by moderating the impact of life stress31. Conversely, social support appears to act as a buffer in the relationship between life stress and sports injury outcomes; athletes with robust social support networks demonstrate greater resilience to injury amid high levels of life stress than those with limited social support31.

TABLE II.

Preventive Techniques

| Technique | Brief Description |

|---|---|

| Cognitive techniques | Includes positive self-talk, relaxation methods, and meditation to mitigate negative thoughts |

| Sleep optimization | Emphasizes the critical role of sleep in training, recovery, and performance |

| Motivational orientation | Promotes autonomous motivational orientation to encourage injury-prevention behaviors |

| Social support | Acts as buffer in the relationship between life stress and injury outcomes, enhancing resilience |

Limitations

This narrative review has some limitations, particularly the heterogeneity of study designs and sample populations, which may affect the generalizability of findings. The exclusion of non-English studies may have also limited the scope of the review. Furthermore, although findings support the existence of a relationship between mental health and injury, clear cause and effect cannot be established.

Conclusion and Future Direction

This review demonstrates the role of mental health in the assessment, management, and prevention of injuries in athletes. The literature has highlighted the critical influence of psychosocial factors on athletes' injury susceptibility, from preinjury stress responses to psychological distress after injury. Hence, understanding how psychosocial aspects can influence the risk of injury is essential for creating suitable strategies to protect athletes against injuries. In addition, sex disparities in both the type and frequency of injuries highlight the need for sex-specific approaches in injury prevention and rehabilitation. The literature indicates the integration of cognitive techniques, such as positive self-talk and relaxation methods, into injury prevention programs to limit negative thoughts that have been shown to predispose athletes to injury.

In summary, promoting good sleep hygiene and enhancing psychological orientation toward autonomy in athletes will result in more effective injury prevention behaviors. The literature also indicates that providing social support and developing coping skills among athletes can reduce the incidence of injuries. Sports organizations should embrace an adjusted strategy that involves approaches from 2 perspectives, physical and psychological, to help enhance athletes' health, performance, and QoL. Future research should not only investigate the long-term psychological effects of sports injuries and the efficacy of psychological interventions but also develop tailored and integrated strategies to address needs for injury prevention and rehabilitation as well as mental health and physical recovery in diverse athletic populations.

Sources of Funding

No funding was provided in the investigation of this study.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Disclosure: The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJSREV/B267).

Contributor Information

Waleed Albishi, Email: dralbishi@gmail.com.

Salem Alshehri, Email: alodaibymc@gmail.com.

Nasser M. AbuDujain, Email: nasserabudujain@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Maron BJ, Zipes DP. Introduction: eligibility recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities-general considerations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(8):1318-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malm C, Jakobsson J, Isaksson A. Physical activity and sports-real health benefits: a review with insight into the public health of Sweden. Sports. 2019;7(5):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reardon CL, Hainline B, Aron CM, Baron D, Baum AL, Bindra A, Budgett R, Campriani N, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Currie A, Derevensky JL, Glick ID, Gorczynski P, Gouttebarge V, Grandner MA, Han DH, McDuff D, Mountjoy M, Polat A, Purcell R, Putukian M, Rice S, Sills A, Stull T, Swartz L, Zhu LJ, Engebretsen L. Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement (2019). Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(11):667-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGuine T. Sports injuries in high school athletes: a review of injury-risk and injury-prevention research. Clin J Sports Med. 2006;16(6):488-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soligard T, Palmer D, Steffen K, Lopes AD, Grek N, Onishi K, Shimakawa T, Grant ME, Mountjoy M, Budgett R, Engebretsen L. New sports, COVID-19 and the heat: sports injuries and illnesses in the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(1):46-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang C, Putukian M, Aerni G, Diamond A, Hong G, Ingram Y, Reardon CL, Wolanin A. Mental health issues and psychological factors in athletes: detection, management, effect on performance and prevention: American Medical Society for Sports Medicine Position Statement-Executive Summary. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(4):216-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brewer BW, Redmond CJ. Psychology of Sport Injury. Human Kinetics Publishers; 2016:3-19. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwab Reese LM, Pittsinger R, Yang J. Effectiveness of psychological intervention following sport injury. J Sports Health Sci. 2012;1(2):71-9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Podlog L, Eklund RC. A longitudinal investigation of competitive athletes' return to sport following serious injury. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2006;18(1):44-68. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haugen E. Athlete mental health & psychological impact of sport injury. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2022;30(1):150898. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furie K, Park AL, Wong SE. Mental health and involuntary retirement from sports post-musculoskeletal injury in adult athletes: a systematic review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2023;16(5):211-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arvinen-Barrow M, Walker N, editors. The Psychology of Sport Injury and Rehabilitation. Routledge; 2013:40-133. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Junge A. The influence of psychological factors on sports injuries. Review of the literature. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(5 suppl):S10-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahern DK, Lohr BA. Psychosocial factors in sports injury rehabilitation. Clin Sports Med. 1997;16(4):755-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Passer MW, Seese MD. Life stress and athletic injury: examination of positive versus negative events and three moderator variables. J Hum Stress. 1983;9(4):11-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galambos SA, Terry PC, Moyle GM, Locke SA, Lane AM. Psychological predictors of injury among elite athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(6):351-4; discussion 351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maddison R, Prapavessis H. A psychological approach to the prediction and prevention of athletic injury. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2005;27(3):289-310. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng S, Yang T, Rockett IRH. Life stress and uncertainty stress: which is more associated with unintentional injury? Psychol Health Med. 2020;25(6):774-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes L, Leavey G. Setting the bar: athletes and vulnerability to mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(2):95-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nippert AH, Smith AM. Psychologic stress related to injury and impact on sport performance. Phys Med Rehab Clin North Am. 2008;19(2):399-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schinke RJ, Stambulova NB, Si G, Moore Z. International Society of Sport Psychology position stand: athletes' mental health, performance, and development. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2018;16(6):622-39. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen MB, Williams JM. A model of stress and athletic injury: prediction and prevention. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1988;10(3):294-306. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiese-Bjornstal DM. Sport injury and college athlete health across the lifespan. J Intercollegiate Sport. 2009;2(1):64-80. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiese-Bjornstal DM. Psychology and socioculture affect injury risk, response, and recovery in high-intensity athletes: a consensus statement. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(suppl 2):103-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dionigi RA, Fraser-Thomas J, Stone RC, Gayman AM. Psychosocial development through Masters sport: what can be gained from youth sport models? J Sports Sci. 2018;36(13):1533-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almeida PH, Olmedilla A, Rubio VJ, Palou P. Psychology in the realm of sport injury: what it is all about. Rev Psicol Deporte. 2014;23:395-400. [Google Scholar]

- 27.van den Noort D, Oltmans E, Aoki H, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Gouttebarge V. Clinical hip osteoarthritis in current and former professional footballers and its effect on hip function and quality of life. J Sports Sci Med. 2021;20(2):284-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith AM, Scott SG, O'Fallon WM, Young ML. Emotional responses of athletes to injury. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65(1):38-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leddy MH, Lambert MJ, Ogles BM. Psychological consequences of athletic injury among high-level competitors. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1994;65(4):347-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heidari J, Hasenbring M, Kleinert J, Kellmann M. Stress-related psychological factors for back pain among athletes: important topic with scarce evidence. Eur J Sport Sci. 2017;17(3):351-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Souter G, Lewis R, Serrant L. Men, mental health and elite sport: a narrative review. Sports Med Open. 2018;4(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heaney CA, Walker NC, Green AJK, Rostron CL. Sport psychology education for sport injury rehabilitation professionals: a systematic review. Phys Ther Sport. 2015;16(1):72-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brewer BW. Chapter: injury prevention and rehabilitation. In: Brewer BW, editor. Sport Psychology. Wiley-Blackwell; 2009:75-86. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piussi R, Krupic F, Senorski C, Svantesson E, Sundemo D, Johnson U, Hamrin Senorski E. Psychological impairments after ACL injury: do we know what we are addressing? Experiences from sports physical therapists. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2021;31(7):1508-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen JVK, Brennan JH, Mitra B, Willmott C. Frequency and magnitude of game-related head impacts in male contact sports athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2019;49(10):1575-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Champigny C, Roberts SD, Terry DP, Maxwell B, Berkner PD, Iverson GL, Wojtowicz M. Acute effects of concussion in adolescent athletes with high preseason anxiety. Clin J Sport Med. 2022;32(4):361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filbay S, Pandya T, Thomas B, McKay C, Adams J, Arden N. Quality of life and life satisfaction in former athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2019;49(11):1723-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreira NB, Mazzardo O, Vagetti GC, De Oliveira V, De Campos W. Quality of life perception of basketball master athletes: association with physical activity level and sports injuries. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(10):988-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Azubuike SO, Okojie OH. An epidemiological study of football (soccer) injuries in Benin City, Nigeria. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(5):382-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marshall AN, Snyder Valier AR, Yanda A, Lam KC. The impact of a previous ankle injury on current health-related quality of life in college athletes. J Sport Rehab. 2020;29(1):43-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herrero CP, Jejurikar N, Carter CW. The psychology of the female athlete: how mental health and wellness mediate sports performance, injury and recovery. Ann Joint. 2021;6:38. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, Moreland JJ, Peek-Asa C, Yang J. Preseason anxiety and depressive symptoms and prospective injury risk in collegiate athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(9):2148-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGuine TA, Winterstein A, Carr K, Hetzel S, Scott J. Changes in self-reported knee function and health-related quality of life after knee injury in female athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22(4):334-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGuine TA, Winterstein AP, Carr K, Hetzel S. Changes in health-related quality of life and knee function after knee injury in young female athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(4):2325967114530988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Granito VJ, Jr. Psychological response to athletic injury: gender differences. J Sport Behav. 2002;25:243. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Appaneal RN, Levine BR, Perna FM, Roh JL. Measuring postinjury depression among male and female competitive athletes. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2009;31(1):60-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aron CM, Harvey S, Hainline B, Hitchcock ME, Reardon CL. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other trauma-related mental disorders in elite athletes: a narrative review. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(12):779-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore HS, Walton SR, Eckenrod MR, Kossman MK. Biopsychosocial experiences of elite athletes retiring from sport for career-ending injuries: a critically appraised topic. J Sport Rehabil. 2022;31(8):1095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnston LH, Carroll D. The context of emotional responses to athletic injury: a qualitative analysis. J Sport Rehabil. 1998;7(3):206-20. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bianco T, Malo S, Orlick T. Sport injury and illness: elite skiers describe their experiences. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70(2):157-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacobsson J, Timpka T, Kowalski J, Nilsson S, Ekberg J, Dahlström Ö, Renström PA. Injury patterns in Swedish elite athletics: annual incidence, injury types and risk factors. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(15):941-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pearson L, Jones G. Emotional effects of sports injuries: implications for physiotherapists. Physiotherapy. 1992;78(10):762-70. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith AM. Psychological impact of injuries in athletes. Sports Med. 1996;22(6):391-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Creado SA, Advani S. Sleep disorders in the athlete. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2021;44(3):393-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Charest J, Grandner MA. Sleep and athletic performance: impacts on physical performance, mental performance, injury risk and recovery, and mental health: an update. Sleep Med Clin. 2022;17(2):263-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brooks TJ, Bradstreet TC, Partridge JA. Current concepts and practical applications for recovery, growth, and peak performance following significant athletic injury. Front Psychol. 2022;13:929487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mohammed WA, Pappous A, Sharma D. Effect of mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) in increasing pain tolerance and improving the mental health of injured athletes. Front Psychol. 2018;9:722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith AM, Scott SG, Wiese DM. The psychological effects of sports injuries. Coping. Sports Med. 1990;9(6):352-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE. A systematic review of the psychological factors associated with returning to sport following injury. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(17):1120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crossman J. Psychological rehabilitation from sports injuries. Sports Med. 1997;23(5):333-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arvinen-Barrow M, Massey WV, Hemmings B. Role of sport medicine professionals in addressing psychosocial aspects of sport-injury rehabilitation: professional athletes' views. J Athl Train. 2014;49(6):764-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ford UW Gordon S. Gordon S. Coping with sport injury: resource loss and the role of social support. J Personal Interpersonal Loss. 1999;4(3):243-56. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cook JD, Charest J. Sleep and performance in professional athletes. Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2023;9(1):56-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chan DKC, Hagger MS. Transcontextual development of motivation in sport injury prevention among elite athletes. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2012;34(5):661-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]