Abstract

Cell migration is an essential step in wound healing. Mechanical input from the local microenvironment controls cell velocity and directionality during migration, which is translated into biochemical cues by focal adhesion kinase (FAK) inside the cell. FAK induces both regeneration and fibrosis. The mechanisms by which FAK decides wound fate (regenerative or fibrotic repair) in soft, normal wounds or stiff, fibrotic wounds remains unclear. Here we show that FAK differentially mechanoregulates wound behavior on soft substrates mimicking normal wounds and stiff substrates mimicking fibrotic wounds by converting mechanical substrate stimuli into variable cell velocity, directionality, and angle during wound healing. Cells on soft substrates migrate slower and less persistently; cells on stiff substrates migrate faster and more persistently with the same angle as the cells on normal wound substrates. Inhibition of FAK results in substantially slower, less persistent, and less correctly angled cell migration, which leads to slowed wound closure. Moreover, FAK inhibition impairs fibroblast’s ability to respond to substrate stiffness when migrating. Here we show that FAK is an essential mechanoregulator of wound migration in fibroblast wound closure and is responsible for controlling cell migration dynamics in response to substrate stiffnesses mimicking normal or fibrotic wounds.

Keywords: FAK, mechanotransduction, migration, fibroblast, wound healing, focal adhesion

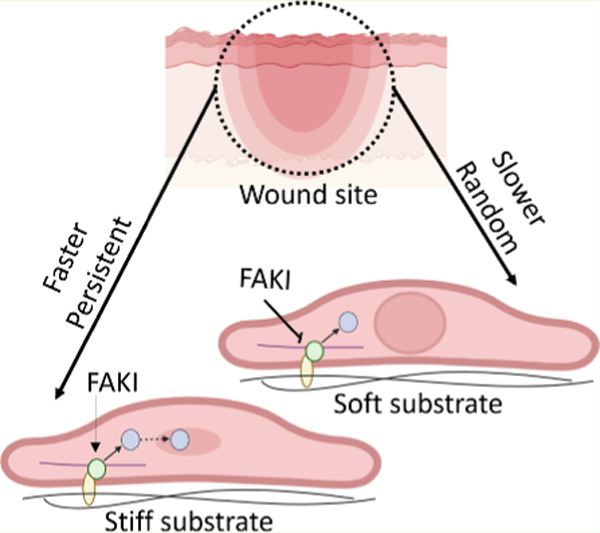

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Cell migration is widely regarded as the rate-limiting step in wound healing.1–4 Cells migrate in response to various stimuli, including chemotaxis (chemical attractants), durotaxis (mechanical signals), and gene regulation (biological drivers).5–10 Of these, mechanical forces regulate wound outcomes on multiple levels. Force mitigation is recognized to reduce scar formation by decreasing the fibrotic deposition of excess extracellular matrix. Force mitigation can even induce regeneration by restoring the original tissue structure–function. Wounds bisecting Langer lines, a 3D map of mechanical load along the human dermis from gravity, location, and underlying extracellular matrix (ECM) structure, develop increased scar response compared to normal fibrotic repair,11–13 whereas areas of minimal to nonexistent contraction (fetal cutaneous wounds,14 wound areas with no contractile forces15) undergo actual regeneration or recapitulation of the original tissue structure-function. Therefore, force mitigation is an important aspect of wound healing that determines which pathways are activated: fibrotic repair or regenerative repair.

Mechanistically, cells migrate into the wound by connecting to their local microenvironment via actin dynamic structures, lamellipodia and filopodia, and contracting to pull the cell body forward.16 On the interior of the cell, the focal adhesion protein complexes assemble to connect transmembrane receptor proteins to the actin cytoskeleton, which drives cell motility.17 Focal adhesion recruitment dynamics remain a consistent focus of study, as the focal adhesion complex is subject to many regulators. The strength, size, and maturity of the focal adhesion complex is strongly affected by receptor-specific activation (ECM or cell binding) and mechanical input from local microenvironmental forces, leading to complex and nuanced activation profiles.7,18,19

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a nonreceptor protein tyrosine that is part of the focal adhesion complex.20 FAK is especially mechanosensitive and controls several mechanotransduction pathways.17,21–24 It senses mechanical signals from the local microenvironmental and translates them into biochemical cues driving cell migration and fibrosis.25 Substrate properties affecting FAK signaling include whether the model is 2D or 3D, soft or stiff,26 viscoelastic or elastic,26–28 and can lead to various and nonlinear FAK-mediated cell responses.29–31 Moreover, FAK has a complex and nuanced signaling profile that is dependent on many factors including cell density, cell area, presence/absence of downstream signaling effectors, and focal adhesion size (strength of connection to the local microenvironment).19 FAK can be directly correlated with the fibrotic response.9,25,32 During fibrosis, the extracellular matrix is stiffer and more aligned, providing a vastly different microenvironment for cells to interact with than that in wounded tissue.33–35 In 2D wound assays, FAK is necessary for wound contraction (closure).9 Moreover, inhibition of FAK directly promotes tissue regeneration.36 How FAK is active in both fibrotic and regenerative repair is an open question.

Migration is an essential step of wound healing; moreover, the rate of wound closure serves as a prognostic indicator of beneficial wound outcomes, including regeneration. The microenvironment plays an essential role in deciding wound fate by controlling various cell behaviors, including migration.37,38 FAK is an important element of the focal adhesion complex that connects the exterior cell environment to the internal cell signaling mechanisms. Since FAK is involved in both regenerative and fibrotic wound outcomes, our research question focused on whether we could induce a superior wound closure outcome by inhibiting key biochemical factors responding to fibrotic mechanical stimuli. Therefore, we investigated if therapeutically targeting FAK’s mechanoresponses to inhibit fibrotic mechanical cues would restore normal wound closure behaviors in an abnormally stiff fibrotic environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Substrate Manufacturing and Cell Culture.

The 2D wound assay polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrates mimicking human skin viscoelasticity were fabricated by varying the base:cross-linker ratio (49:1 and 40:1, respectively) to obtain a Young’s moduli of 18 and 146 kPa, which are literature averages for normal and fibrotic wound stiffnesses, respectively.33 A thin PDMS layer of 0.25 g was measured per well into a 12 well plate and was cured at 60 C for 4 h. PDMS substrates were washed with PBS for 2 h prior to 15 min of UV sterilization. These PDMS substrates were then coated (1 h of incubation at 24 °C) with 30 μg/mL plasma fibronectin (33016015, ThermoFisher) to promote cell adhesion. A sterilized 10:1 PDMS mask measuring approximately 0.5 mm wide was placed in the middle of each well atop the fibronectin coated PDMS. Commercially available adult human dermal fibroblasts (HDFa, PCS-201–012 ATCC) of passage 8 or lower were seeded on the fibronectin-coated PDMS substrates at 65,000 cells/100 mm2 24 h prior to assay start. Cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin around this separate PDMS mask, which when removed, simulated wounding and began the wound assay.

Inhibitor Conditions.

FAK inhibitor FAKI (HY-10459, PF-562271, FAKI vs6062, Med Chem Express) was exogenously added to the cell culture medium at the start of the wound assay. The FAKI concentration was 5 μM/mL.36 As DMSO was the solvent used for the inhibitor, a DMSO control of 5 μM/mL was used to match the concentration of inhibitor used.

Time Lapse Microscopy and Cell Analysis.

Using a Keyence BZ-X8000 fluorescent light microscope, time lapse images of phase and Cy5 LED channels were taken with a 10× objective every 10 min for 48 h post wounding. The individual .tiff images were then compiled to create time lapse image stacks. Inclusion criteria included no visible defects to the PDMS at the wound site or wound edges within the field of view. Time lapse image stacks were excluded if a significant amount of cells had migrated into the wound site under the PDMS mask prior to mask removal. The wound area, or the area free of migrating cells, was measured every 12 h from the phase videos to quantify wound area over time (0, 12, 24, 36, 48 h time points). The wound area was freehand traced in ImageJ Fiji39 around the cells migrating into the wound, and the area within the enclosed boundary was measured at each time point. Wound closure over time for all time slices were then divided by the original wound area (100%) measured at time 0 h to return the percentage of wound area closed. The equation for wound area is (TI /T0) × 100, where TI is the wound area at a given time point, and T0 is the wound area at the wound start.

The Cy5 LED channel time lapse videos of wound fluorescent nuclei, labeled with SPY595 DNA tracker, were run through ImageJ Fiji TrackMate analysis to identify spots, fluorescent nuclei per time slice, and tracks, which combine the spots across all slices into a coherent single cell migration track.40 TrackMate spot sizes were limited to spots under 20 μm. TrackMate duration track filters (excluding tracks with less than 4 spots) were applied to limit noise from artifacts and single spot recognition; the spot gap closing algorithm was limited to 4 time slices with 10 min elapsing between these slices, and less than 30 μm distance traveled during that period to generate accurate tracks of cellular migration without overlap or confusion of tracks. The TrackMate tracks were further analyzed through Chemotaxis and the Migration tool (Ibidi) to plot the migration data, including velocity, directionality, and cell angle. Directionality was taken as a measure of cell persistence or consistent migration in the same direction. Therefore, a straight line is considered a 1, whereas a cell track with many switchbacks continually turning back on itself or randomly migrating is taken as a 0.

Immunostaining, Confocal Imaging and Analysis.

After the 48 h scratch wound assay, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h prior to immunostaining. The samples were treated with a primary antibody for phospho-FAK (1:100, 44–624G, ThermoFisher) and a corresponding secondary antibody, AlexaFluor488 (1:100, A11008, ThermoFisher), and DAPI (1:5000, D1306, LifeTechnologies). Confocal imaging was performed on an Olympus Fluoview FV1200 at 60× oil objective, 100 μm pinhole, and 2 μm thick step slices to obtain images of pFAK, the actin cytoskeleton, and the cell nuclei. The 405 laser was used at 5% and HV 616 to image DAPI. The 488 laser was used to image pFAK at 21% and HV 518. The 635 laser was used to image the actin cytoskeleton at 21% and HV 426. The confocal microscope images were analyzed in ImageJ Fiji to collect the maximum intensity projection of each individual channel corresponding to nuclei, pFAK, and actin. Cells were manually outlined to collect the fluorescent intensity from the brightness adjusted (min: 150, max: 350) pFAK images. From these cell outlines, the integrated density of the pFAK fluorescent pixels were collected per field of view to analyze how much activated FAK was present in each cell. A total sample size of 3–5 fields of view were analyzed per condition.

Statistical Analysis.

Sample size per condition was run with 3–5 separate wounds per condition. Two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparisons posthoc analysis in GraphPad Prism 9 were used to evaluate each test condition as appropriate. Within each time point and test condition, cell responses on soft (normal) and stiff (fibrotic) substrates were compared. Across time points and test conditions, only similar stiffnesses were compared. Wound closure analysis was plotted with a best fit linear regression line. The slope and standard error of the best fit lines plotting the wound closure rate per condition were compared. All data are presented as median ± standard deviation unless otherwise noted.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Substrate Stiffness Did Not Alter Wound Closure Rate but Did Alter Individual Cell Dynamics.

We examined cell dynamics (Figure 1A,B,C) on soft or stiff substrates mimicking normal (18 kPa) and fibrotic (146 kPa) wounds, respectively. We observed that the wound closure rate on softer, normal wound substrates was not significantly different compared to the wound closure rate on stiffer, fibrotic wound substrates (Figure 1D). However, cells on softer substrates (normal wound) migrated significantly more slowly than cells on stiffer substrates (fibrotic wound) (Figure 1E). Cells on softer, normal wound substrates also migrated more randomly than cells on the stiffer, fibrotic substrates (Figure 1F). The axis of wound closure falls along the x-axis of 0–180° (Figure 1C,G). We observed that cells did not significantly change their angle of migration toward wound closure based on their substrate stiffness.

Figure 1.

Cells on softer substrates mimicking normal wounds migrate slower and less persistently than cells on stiffer substrates mimicking fibrotic wounds. A. Representative 10× images of the wound on normal and fibrotic substrates, scale bar 500 μm in phase microscopy, used to quantify wound area. In parallel, the time lapse videos were analyzed in TrackMate (ImageJ Fiji plugin) and Ibidi Chemotaxis and Migration Tool to extract cell migration dynamics, plotted as (B) representative cell tracks. C. Cell angle was measured between start and end position. The angle of cell migration is shown in degrees along four Cartesian quadrants, numbers shown around the plot perimeter. Radial numbers indicate the number of cells per direction. D. No significant difference in the rate of wound closure between substrate stiffnesses was observed. Linear regression analysis is plotted as dotted lines, and the slope is included in the legend. E. Cells on softer substrates migrated significantly slower than cells on stiffer substrates. ****P < 0.0001. F. Cells migrated more randomly, or with less directionality and persistence, on softer substrates than cells on fibrotic substrates. ****P < 0.0001. G. Cell migration angle toward the axis of wound closure does not change significantly based on substrate stiffness. N ≥ 3 replicates. All significances evaluated with 2-way ANOVAs, with Šídák’s multiple comparisons posthoc analysis.

In our model, cells behave according to the conventional paradigm that cell speed is greater on stiffer substrates.41–43 This relationship is mutable; depending on material surface properties and biochemical cues, cell speed on stiffer substrates can vary; these factors can also alter other migration parameters, including persistence.44,45 In our wound assay, we observed that persistence was greater (less random) on increased substrate stiffness. This is corroborated by existing literature that substrate stiffness coupled with an homogeneous Fn coating leads to higher persistence.44 Moreover, our results also supports that wound closure rate is not dependent on substrate stiffness,46 though substrate stiffness does alter certain individual cell migration dynamics such as cell velocity and persistence. Group migration shields migrating sheets from the effect of substrate stiffness.46 Cell density also supersedes substrate stiffness in affecting migration velocity.47 The cells on stiffer substrates are likely experiencing higher friction which could contribute to these individual cell dynamics,48 while the group dynamics dictate the wound closure rate.

Having established the dynamic cell responses to substrate stiffness in our model, we next examined how cells used FAK-mediated signaling to control the varying migration dynamics observed in response to mechanical stimuli from the substrate stiffness designed to mimic normal or fibrotic wounds.

Inhibition of FAK Slows Wound Closure Rate Inversely Dependent on Substrate Stiffness.

With the introduction of the FAK inhibitor, FAKI, we used DMSO as a control for comparison since our inhibitor was reconstituted in DMSO. The rate of wound closure (Figure 2A) from DMSO-treated fibroblasts was again not affected by substrate stiffness (Figure 2B,C). However, when FAK was inhibited on both soft and stiff substrates, fibroblasts slow wound closure. In fact, when FAK was inhibited, wound closure on the stiffer substrate was the slowest, even slower than wound closure on the soft substrate. This suggests that FAK inhibition impairs the cells’ ability to coordinate their internal contractile machinery to respond to the mechanical input from the microenvironment. Therefore, our data shows that FAK inhibition alters the cell’s ability to close the wound.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of FAK slows wound closure rate inversely to substrate stiffness. A. Representative phase images were obtained at a 10× objective. The wound area is marked by dashed lines, with the scale bar at 500 μm. B. Wound closure is plotted as a percentage of the wound area remaining. FAK inhibition slows the gap closure time, indicating this protein is essential during wound closure. Dashed lines indicate linear regression for 18 kPa substrates, and unevenly dotted lines represent linear regression lines for 146 kPa substrates; green represents FAKI conditions, and orange denotes DMSO conditions. C. Same wound area data are plotted via box and whisker graphs showing wound area per time point for ease of visualization. N ≥ 3 replicates. Mean plotted as data points and standard deviation plotted in bars. Linear regression analysis is plotted in dotted lines, and the slope is included in the legend.

The DMSO-treated fibroblasts did not close the wound differently than the media control did, regardless of substrate stiffness (Figure S1, Figure 6A). The role of FAK in mediating wound closure remains unclear, with conflicting results appearing in the literature. Inhibition of FAK within in vitro models promote wound closure by attenuating the fibrotic response.49 Conversely, FAK inhibition also slows fibroblast migration (supported by our results).21 Within in vivo models, FAK inhibition leads to more wound closure, likely through less cell contractility.50 However, FAK promotion increases migration through α-catenin-mediated activation of FAK,21 a pro-migratory FAK/ERK 1/2/YAP pathway,51 or by FAK inhibition by decreasing the fibrotic regulator FRNK.32 While this might suggest that activating the FAK-mediated pathway controls the nature of the cell response, the reality is not so clear. FAK can activate multiple types of responses through the same pathway. For example, FAK is known to regulate pro-migratory pathways, including PI3K and ERK 1/2.21,52 Additionally, the integrin-based FAK-Src-PI3K-YAP pathway inhibits the Hippo pathway, resulting in decreased contact inhibition.53 In wound healing, α-catenin increases FAK/YAP activation to drive fibroblast migration and proliferation.21 However, FAK also regulates pro-fibrotic mechanisms through these pathways as well: ERK36 and YAP,54,55 as well as others like the Akt pathway.56

Why various pathways—or even the same pathway—are activated within wound repair leading to either fibrosis or regeneration is unclear; how does mechanical stiffness interplay with FAK to regulate migration dynamics? Therefore, we quantified more nuanced individual cell migration dynamics to probe how FAK drives wound closure mechanisms in the context of soft and stiff substrates mimicking normal and fibrotic wounds, respectively.

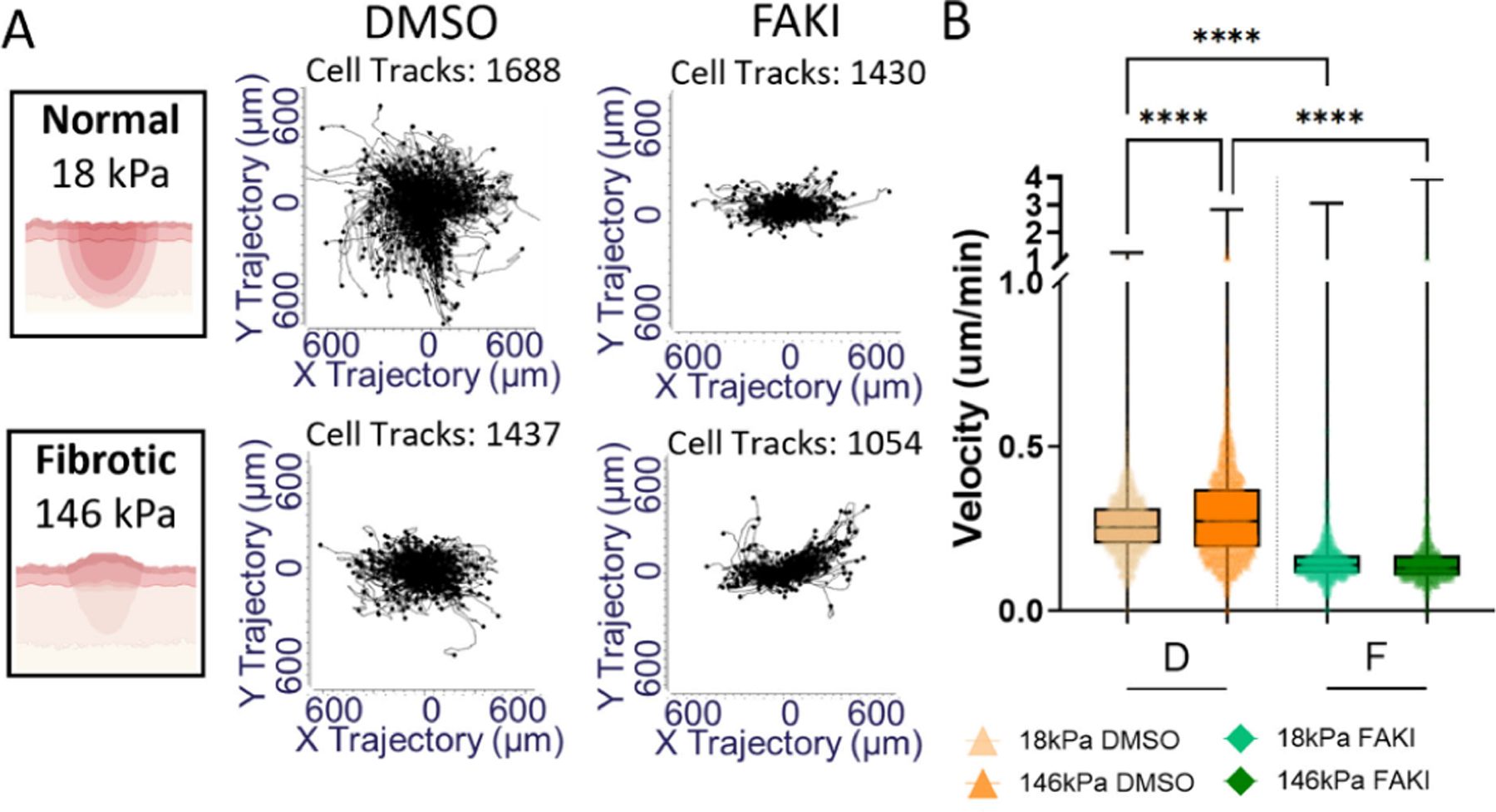

FAK Inhibition Slows Cell Migration.

We next quantified fibroblast velocity to investigate migration dynamics (Figure 3A) behind the slower wound closure observed when inhibiting FAK signaling. Interestingly, FAK-inhibited fibroblasts demonstrated no significant differences in velocity between substrate stiffnesses (Figure 3B). Additionally, when FAK was inhibited, cell velocity on both substrate stiffnesses was significantly slower than that on their DMSO control counterparts. The addition of DMSO significantly slowed fibroblast velocity on softer substrates (Figure 6D).

Figure 3.

FAK inhibition slows cell velocity. A. Representative cell tracks per condition as plotted in Chemotaxis and Migration tool with data obtained from Trackmate analysis of cell dynamics. B. Cell velocity obtained from Chemotaxis and Migration Tool after TrackMate analysis. ****P < 0.0001. N ≥ 3 replicates. All significances evaluated with 2-way ANOVAs, with Šídák’s multiple comparisons posthoc analysis.

Our results indicate that in our fibroblast model, a low dose of DMSO (<0.005%) lowers fibroblast velocity compared to an untreated control. Previous work has indicated DMSO treatment in wound environments nonsignificantly reduces human dermal fibroblast migration compared to an untreated control.57

More importantly, FAK inhibition significantly slowed migration velocity regardless of substrate stiffness. This is consistent with literature, which indicates FAK, mediated by the TYR-397 site, is largely responsible for bulk migration response to mechanical input.20 FAK inhibition completely dysregulated the fibroblasts’ ability to change speed in response to varying substrate stiffnesses. However, the ability of a cell to continue migrating in a certain direction might also be impacted by mechanical stiffness cues. Therefore, we next studied cell persistence to shed light on the mechanisms of FAK-mediated migration dynamics.

FAK Mediates Cell Persistence.

For migration to occur, a cell must be traveling along a trajectory (Figure 4A). Persistence is defined as the ability of the cells to continue migrating in one direction (Figure 6C). A cell that travels in a straight line is highly persistent, while a cell that changes directions many times is not persistent and migrating randomly. The DMSO-treated fibroblasts migrated more randomly (less persistent) on the stiffer substrates (Figure 4B). Comparatively, DMSO-treated cells on the softer substrates mimicking normal wounds migrated with more persistence. This indicates that despite the faster migration velocity observed in Figure 3, DMSO-treated cells are unable to persistently migrate in the same direction on the stiffer substrates mimicking fibrotic tissue (Figure 4B). Compared with the original media conditions, DMSO treatment significantly downregulates cell persistence on stiffer substrates (Figure 6E). Additionally, treatment with DMSO promoted cell persistence on softer wound substrates compared to that of the media control (Figure 6E). The effect of DMSO on fibroblast persistence is not well studied. In this model, our data indicates DMSO deregulates fibroblasts’ ability to respond to their environment by promoting persistence on softer substrates and inhibiting this persistence on stiffer substrates.

Figure 4.

FAK inhibition dysregulates cell directionality and angles away from axis of closure. A. Representative rosette plots of cell angle during wound closure. In-house Matlab code was used to plot Chemotaxis and Migration Tool-calculated angles. B. Cell directionality, ****P < 0.0001. C. Cell angle measured between start and end position. The angle of cellular migration shown in degrees along four Cartesian quadrants, numbers shown around the plot perimeter. Radial numbers indicate number of cells per direction, ***P < 0.0005, ****P < 0.0001. N ≤ 3327 cells from N ≤ 3 wells plotted in median and standard deviation, two-way ANOVA, Šídák’s multiple comparisons posthoc analysis.

FAK-inhibited fibroblasts on softer substrates showed significantly lower persistence compared with the DMSO control (Figure 4B). Likewise, on the stiffer substrates, cells treated with FAKI were significantly less persistent than their DMSO control counterparts. Moreover, unlike the DMSO controls, FAK inhibited fibroblasts showed no significant changes in cell persistence when migrating on soft (normal) and stiff (fibrotic) substrates. This indicates that the mechanism by which cells respond to their mechanical cues is mediated by FAK for both cell velocity and persistence.

FAK’s role in translating mechanical cues into biochemical migration responses is well established.9,20,25,58 FAK-null fibroblasts prefer to migrate away from softer substrates (due to generating less traction forces), and also demonstrate less directional persistence than controls.20 However, in a homogeneous system with unchanging substrate stiffness, FAK inhibition has been shown to decrease migration dynamics by altering β1 mediated activation of FAK.9 Too much persistence has been associated with exacerbation of the fibrotic response due to promotion from pro-fibrotic signaling.9 Therefore, reduced migratory persistence is a mechanism by which FAK inhibition can decrease the fibrotic response.9 Our results suggest that when FAK is inhibited, cells no longer alter their persistent migration behavior in response to mechanical stimuli (substrate stiffnesses). Yet, FAKI-treated cells closed wounds faster on softer substrates mimicking normal wounds than FAKI-treated cells on stiffer substrates mimicking fibrotic wounds. Cells do not migrate in a directionless manner; therefore, we next studied the angle of cell migration during wound closure, a parameter assigning a vector to our directionality data to understand how the cells are angled toward the axis of wound closure during migration.

FAK Inhibition Dysregulates Angle of Wound Closure.

The angle at which the end point of the cell’s trajectory points away from the origin (Figure 6B) indicates the orientation of the cell’s movement. The 0–180° x-axis, which is perpendicular to the wound along the x-axis, is logically the angle of the most efficient wound closure. Based on our data (Figure 4A,C), fibroblasts in the DMSO control condition angle toward the x-axis, perpendicular to the wound edges, indicating that 180° is the angle oriented toward wound closure regardless of substrate stiffness. FAK inhibition dysregulates the cell angle significantly away from the 0–180° wound closure axis regardless of substrate stiffness. Therefore, cells are unable to orient themselves properly toward the wound when FAK is inhibited.

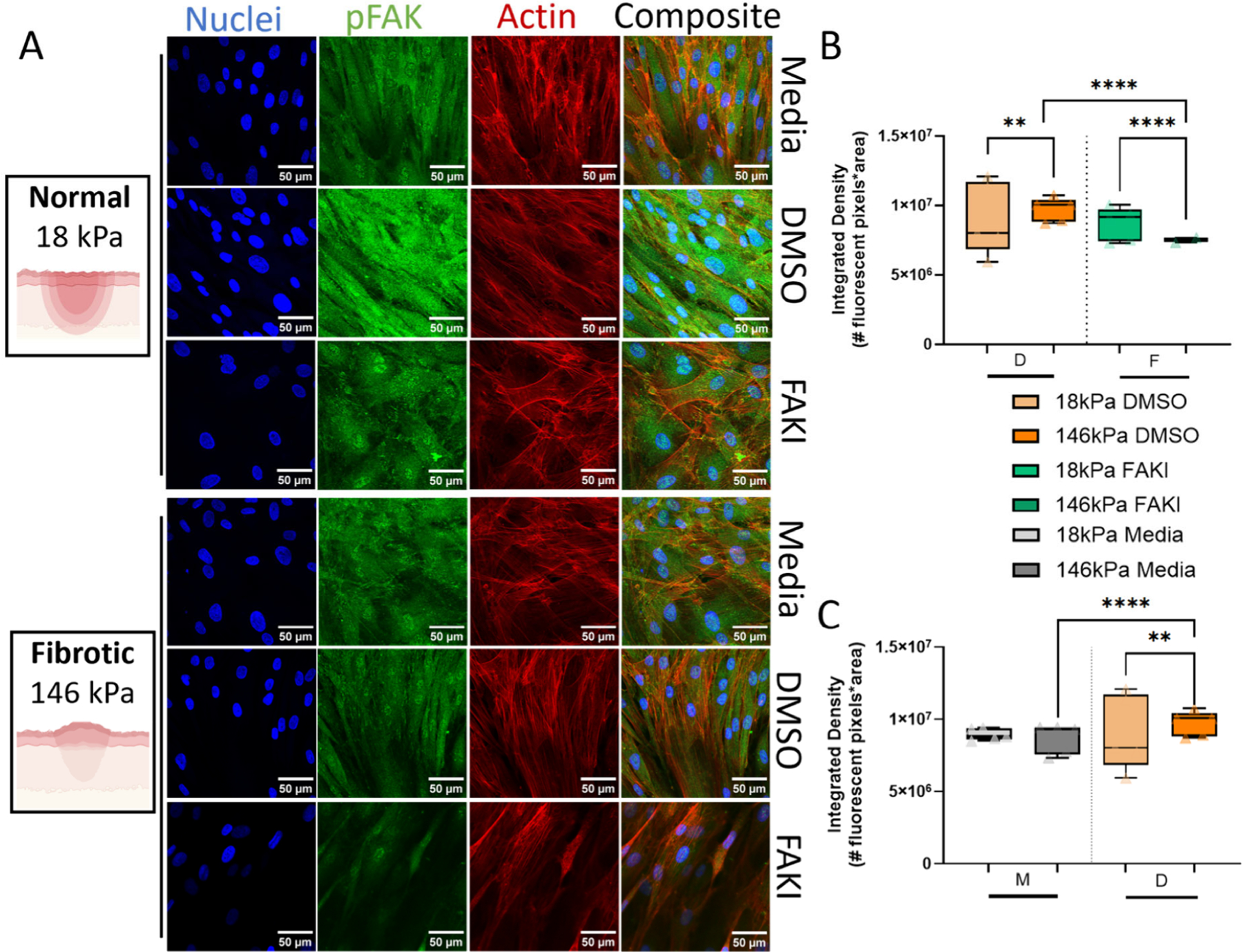

FAK Inhibition Downregulates pFAK Expression on Stiffer, Fibrotic Substrates.

We quantified phospho-FAK (activated FAK) level in the cells at 48 h postwounding via confocal immunostaining (Figure 5A). When treated with DMSO, cells on stiffer, fibrotic substrates display more pFAK activation than cells on softer substrates, mimicking normal wound stiffnesses (Figure 5B). However, this difference is not observed in the media only condition; this is because DMSO upregulates the level of pFAK on stiffer, fibrotic substrates (Figure 5C). Our data indicates that FAK inhibition resulted in significant decrease in pFAK expression only in cells on the stiffer, fibrotic substrate. Since DMSO does increase the expression of pFAK in cells cultured on the stiffer fibrotic substrates, we verified this difference between FAK-inhibited cells and media controls. This comparison between FAK inhibited and media control cells reveal pFAK activation on stiffer substrates (data pictured in Figure 5B–C but the direct comparison is not illustrated, ****P < 0.0001) is still significantly lowered by FAK inhibition. Because DMSO was shown to affect pFAK expression in comparison to the media only, control, we next undertook to verify DMSO effects on other cellular behaviors in our assay.

Figure 5.

FAK inhibition downregulates pFAK expression on stiffer, fibrotic substrates. A. Representative confocal images, 60× oil objective, per condition. Nuclei and actin image brightnesses were adjusted in ImageJ for presentation only. B. Integrated density of fluorescent pixel analysis returned from ImageJ Fiji show lower FAK activation in stiffer fibrotic (146 kPa) substrates compared to DMSO controls. **P = 0.0015, ****P < 0.0001. C. Integrated density of fluorescent pixel analysis returned from ImageJ Fiji comparing the DMSO condition with a completely untreated (media) comparison. **P = 0.0015, ****P < 0.0001. N ≥ 5 replicates, data normalized for cell density. All significances evaluated with 2-way ANOVAs, with Šídák’s multiple comparisons posthoc analysis.

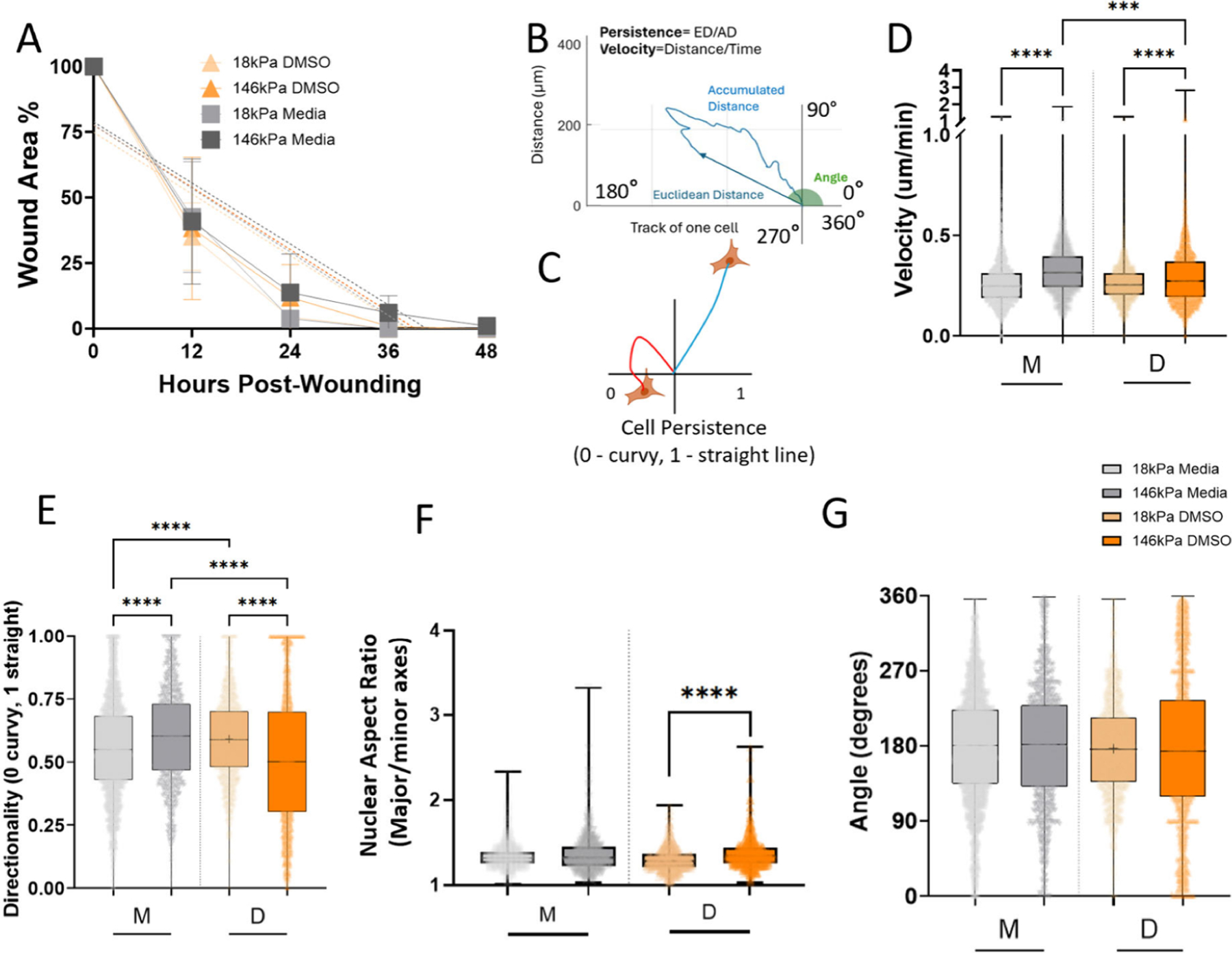

DMSO Affects Migration Velocity and Directionality in a Stiffness-Dependent Manner.

We used DMSO, the FAKI solvent, as a control condition because it has been known to have adverse reactions on cellular behavior.59 We ran a comparison between DMSO and the media-only control to determine whether DMSO, the inhibitor solvent, affected cellular behavior in our wound assay. We observed that while wound closure rates were unaffected by DMSO treatment (Figure 6A), the cellular velocity (Figure 6D) and persistence (Figure 6E) were affected by DMSO treatment in a stiffness dependent manner. When fibroblasts were treated with DMSO, the velocity was decreased on the stiffer, fibrotic substrates. No change was observed between DMSO and media on the softer, normal wound substrates. Cell persistence comparison indicated cells treated with DMSO were more persistent on softer substrates mimicking normal wound stiffnesses and less persistent on stiffer substrates mimicking fibrotic tissue. There was no effect from DMSO treatment compared with media-only controls on nuclear shape (Figure 6F) or angle of migration (Figure 6G). Our data indicates that DMSO affects velocity and directionality, which were both significantly altered from the corresponding DMSO control. As discussed previously, Figure 5 also refers to a difference in pFAK expression in the DMSO-treated control compared to the media-only control. Our data shows that while DMSO does affect cellular behaviors, FAK does further alter cellular behavior in a statistically different manner than DMSO even when we account for the effect of the DMSO solvent.

Figure 6.

DMSO affects migration velocity and directionality in a stiffness-dependent manner. A. Wound closure comparison between media and DMSO controls showed no significant differences. B. Schematic of persistence where persistence is Euclidean distance over accumulated distance. C. Schematic of persistence quantification, with 0 indicating random migration and 1 indicating a continuous line. D. Comparison of media only conditions to DMSO controls indicated DMSO significantly slowed cell velocity on stiffer substrates, ***P = 0.0006, ****P < 0.0001. E. Comparison of media only condition to DMSO control for cell directionality indicates DMSO significantly upregulates directionality on softer substrates while downregulating directionality on stiffer substrates, ****P < 0.0001. F. Comparison of media and DMSO controls indicate that on the softer substrate stiffness, DMSO treatment decreases nuclei aspect ratio, turning the nuclei into a more circular shape corresponding to a less migratory shape, ****P < 0.0001. G. Migration angle was compared DMSO to media. All N ≥ 3 replicates. Two-way ANOVA, with Šídák’s multiple comparisons posthoc testing.

However, the effect of DMSO on migration has not been well studied. What few studies on DMSO there are instead have highlighted that DMSO affects proliferation,60,61 apoptosis and mitochondrial behavior,62 membrane functions,63 and a stunningly large variety of genes and protein expressions.64,65 Therefore, our data highlight new areas of impact for DMSO-treatment of cells. Taken together, our data indicate that cells naturally close the wound at a rate independent of substrate stiffness and suggest that when FAK is inhibited, cell velocity, persistence, and angle are all significantly dysregulated, significantly slowing wound closure.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORKS

FAK is active at a particularly critical junction in the conversion of physical stimuli into biochemical cues; therefore, it appears that FAK is a critical element in regulating the cells’ ability to decipher and respond to substrate stiffness. As our data shows, without FAK, cells are unable to migrate rapidly.66 FAK regulates migration via multiple routes. Previously, inhibition of FAK was demonstrated to increase actin contractile viscosity, which affects migration.67 FAK inhibition was also demonstrated to alter integrin expression, which in turn limited cell migration in response to extracellular matrix cues.68 Another pathway through which FAK regulates migration is through its role as an essential part of the focal adhesion complex maturation.69 Focal adhesions are stronger on stiffer substrates.70 Stronger focal adhesions allow for more nuclear elongation.71 Nuclear elongation contributes to efficacy of Yes associated protein (YAP) signaling by opening nuclear pores, which allows for more YAP nuclear translocation, and promotes migration.72 While these may seem like disparate mechanisms, they feed into supraemergent migration dynamics important to understanding FAK-mediated wound closure mechanisms.

Greater recognition of the importance of group migration dynamics is increasingly recognized to impact wound closure dynamics. One emergent property is actin supra-structures46 which arises from the mechanotransduction effect on migration. Visual examination of fibroblast behavior in the FAK inhibited conditions (Figure 2A) suggests that the number of breakage events, or cells switching from group migration to individual migration, might provide insight into further mechanisms of FAK-mediated migration. FAK appears to be responsible for more than just local substrate stiffness sensing, but also neighbor cell sensing mechanisms as well. FAK-YAP signaling is already known to be sensitive to the neighbor fraction of local cells, likely through integrin-associated activation, which can recognize both ECM and cells.19 Therefore, group migration, including multiple phenomena such as breakage events or single cells breaking away from the migrating sheet and cell cluster tensions, could feed emergent properties that also affect wound closure. Moreover, FAK and YAP are known to have a complex relationship, leading to both regeneration and fibrosis. The field faces the question of how to tease apart this complicated relationship between FAK and YAP in the context of wound closure. Future directions might be well served in contextualizing FAK analysis with localized cell numbers, cell–cell connections, and breakaway events.

Therefore, future directions should include the study of traction force microscopy to investigate if the decreased and impaired migratory phenotype during wound closure caused by FAK inhibition causes a mechanobiological switch toward a less contractile phenotype. Wound contraction plays an essential role in wound closure, and surprisingly, it also decides wound fate, either regeneration or repair. Our study begins to parse migration mechanisms by which FAK inhibition can mitigate the fibrotic input from increased substrate stiffnesses on wound closure, providing more insight into understanding other targeted benefits of FAK inhibition treatment by which it drives pro-regenerative outcomes.50

This work is limited by several factors. This work is conducted in a 2D assay, not 3D. Cells behave differently in 3D, and this is likely to cause differences in fibroblast morphology and behavior not accounted for in this model.73,74 Further, DMSO does affect cell velocity, directionality, and pFAK expression. We have taken the effects of DMSO treatment into account in our analysis to demonstrate the effects of FAKI on the regulation of migration in this wound assay model. Our results, contextualized within the literature, highlight FAK as a key regulator of cell migration in response to substrate stiffness. Our study shows that FAK mediates substrate stiffness induced fibroblast migration dynamics underlying wound closure. Fibroblasts on soft substrates mimicking normal wounds migrate slower and more randomly than fibroblasts on stiff substrates mimicking fibrotic wounds. However, when FAK is inhibited, fibroblasts cannot respond to differences in substrate stiffnesses. Instead, FAK inhibited fibroblasts migrate much slower, more randomly, and less angled toward wound closure, resulting in impaired wound closure rates. Here we show that FAK is responsible for wound closure by controlling cellular migration dynamics (velocity, persistence, and angle of closure) in response to substrate stiffnesses mimicking normal or fibrotic wounds.

Supplementary Material

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5c00667.

Figure S1. Mean ± standard deviation for all data analyzed; Figure S2. Accumulated cell distance with comparison of media-only and DMSO controls; Figure S3 Representative cell dynamics of TrackMate analysis; Figure S4 Unmarked phase images of wound sites; Figure S5. FAK is not essential in regulating nuclear shape dynamics (PDF)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

K.W. acknowledges startup funds from the Bioengineering Department at Temple University, an Office of the Vice President for Research Bridge grant, and a grant (#2305) from the W.W. Smith Charitable Trust. N.A was supported by the Fulbright Foundation. J.D.B and A.O. were supported by the National Institute of Health (5T34 GM 136494). The authors thank the shared departmental resources at Temple University for equipment usage. We thank BioRender for providing a platform to create the schematics used in figures.

Footnotes

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5c00667

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Patten, Department of Bioengineering, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122, United States.

Nourhan Albeltagy, Department of Bioengineering, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122, United States.

Jacob D. Bonadio, Department of Bioengineering, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122, United States

Armando Ortez, Department of Bioengineering, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122, United States.

Karin Wang, Department of Bioengineering, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Rodrigues M; Kosaric N; Bonham CA; Gurtner GC Wound Healing: A Cellular Perspective. Physiol. Rev 2019, 99 (1), 665–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Masson-Meyers DS; Andrade TAM; Caetano GF; Guimaraes FR; Leite MN; Leite SN; Frade MAC Experimental Models and Methods for Cutaneous Wound Healing Assessment. Int. J. Exp. Pathol 2020, 101 (1–2), 21–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Friedl P; Gilmour D Collective Cell Migration in Morphogenesis, Regeneration and Cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2009, 10 (7), 445–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kurosaka S; Kashina A Cell Biology of Embryonic Migration. Birth Defects Res. Part C - Embryo Today Rev 2008, 84 (2), 102–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Campanale JP; Montell DJ Who’s Really in Charge: Diverse Follower Cell Behaviors in Collective Cell Migration. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 2023, 81, 102160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Sunyer R; Conte V; Escribano J; Elosegui-Artola A; Labernadie A; Valon L; Navajas D; García-Aznar JM; Muñoz JJ; Roca-Cusachs P; Trepat X Collective Cell Durotaxis Emerges from Long-Range Intercellular Force Transmission. Science (80-.). 2016, 353 (6304), 1157–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Nardone G; Oliver-De La Cruz J; Vrbsky J; Martini C; Pribyl J; Skládal P; Pešl M; Caluori G; Pagliari S; Martino F; Maceckova Z; Hajduch M; Sanz-Garcia A; Pugno NM; Stokin GB; Forte G YAP Regulates Cell Mechanics by Controlling Focal Adhesion Assembly. Nat. Commun 2017, 8 (May), 15321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Jain M; Dhanesha N; Doddapattar P; Chorawala MR; Nayak MK; Cornelissen A; Guo L; Finn AV; Lentz SR; Chauhan AK Smooth Muscle Cell-Specific Fibronectin-EDA Mediates Phenotypic Switching and Neointimal Hyperplasia. J. Clin. Invest 2020, 130 (1), 295–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Zhao XK; Cheng Y; Liang Cheng M; Yu L; Mu M; Li H; Liu Y; Zhang B; Yao Y; Guo H; Wang R; Zhang Q Focal Adhesion Kinase Regulates Fibroblast Migration via Integrin Beta-1 and Plays a Central Role in Fibrosis. Sci. Rep 2016, 6 (1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Van Der Stoel M; Schimmel L; Nawaz K; Van Stalborch AM; De Haan A; Klaus-Bergmann A; Valent ET; Koenis DS; Van Nieuw Amerongen GP; De Vries CJ; De Waard V; Gloerich M; Van Buul JD; Huveneers S DLC1 Is a Direct Target of Activated YAP/TAZ That Drives Collective Migration and Sprouting Angiogenesis. J. Cell Sci 2020, 133 (3), jcs239947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Langer K On the anatomy and physiology of the skin. British Journal of Plastic Surgery 1978, 31, 3–8.342028 [Google Scholar]

- (12).Meyer M; McGrouther D A Study Relating Wound Tension to Scar Morphology in the Presternal Scar Using Langers Technique. Br. J. Plast. Surg 1991, 44 (44), 291–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Silver F; Siperko L; Seehra G Mechanobiology of Force Transduction in Dermal Tissue. Ski. Res. Technol 2003, 9 (9), 3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Dohi T; Padmanabhan J; Akaishi S; Than PA; Terashima M; Matsumoto NN; Ogawa R; Gurtner GC The Interplay of Mechanical Stress, Strain, and Stiffness at the Keloid Periphery Correlates with Increased Caveolin-1/ROCK Signaling and Scar Progression. Plast. Reconstr. Surg 2019, 144 (1), 58e–67e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Ito M; Yang Z; Andl T; Cui C; Kim N; Millar SE; Cotsarelis G Wnt-Dependent de Novo Hair Follicle Regeneration in Adult Mouse Skin after Wounding. Nature 2007, 447 (7142), 316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Nobes CD Rho GTPases and Cell Migration-Fibroblast Wound Healing. Methods Enzymol 2000, 325 (1996), 441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Sieg DJ; Hauck CR; Ilic D; Klingbeil CK; Schaefer E; Damsky CH; Schlaepfer DD FAK Integrates Growth-Factor and Integrin Signals to Promote Cell Migration. Nat. Cell Biol 2000, 2 (5), 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Zhang B; Zhang Y; Zhang J; Liu P; Jiao B; Wang Z; Ren R Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) Inhibition Synergizes with KRAS G12C Inhibitors in Treating Cancer through the Regulation of the FAK-YAP Signaling. Adv. Sci 2021, 8 (16), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Sero JE; Bakal C Multiparametric Analysis of Cell Shape Demonstrates That β-PIX Directly Couples YAP Activation to Extracellular Matrix Adhesion. Cell Syst 2017, 4 (1), 84–96 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Wang HB; Dembo M; Hanks SK; Wang YL Focal Adhesion Kinase Is Involved in Mechanosensing during Fibroblast Migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2001, 98 (20), 11295–11300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Wang N; Xu X; Guan F; Zheng Y; Shou Y; Xu T; Shen G; Chen H; Lin Y; Cong W; Jin L; Zhu Z α-Catenin Promotes Dermal Fibroblasts Proliferation and Migration during Wound Healing via FAK/YAP Activation. FASEB J 2024, 38 (2), No. e23410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Saleem S; Li J; Yee S-P; Fellows GF; Goodyer CG; Wang R Β1 Integrin/FAK/ERK Signalling Pathway Is Essential for Human Fetal Islet Cell Differentiation and Survival. J. Pathol 2009, 219 (June), 182–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Lachowski D; Cortes E; Robinson B; Rice A; Rombouts K; Del Río Hernández AE FAK Controls the Mechanical Activation of YAP, a Transcriptional Regulator Required for Durotaxis. FASEB J 2018, 32 (2), 1099–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Barker HE; Bird D; Lang G; Erler JT Tumor-Secreted LOXL2 Activates Fibroblasts through Fak Signaling. Mol. Cancer Res 2013, 11 (11), 1425–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Wong VW; Rustad KC; Akaishi S; Sorkin M; Glotzbach JP; Januszyk M; Nelson ER; Levi K; Paterno J; Vial IN; Kuang AA; Longaker MT; Gurtner GC Focal Adhesion Kinase Links Mechanical Force to Skin Fibrosis via Inflammatory Signaling. Nat. Med 2012, 18 (1), 148–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Brusatin G; Panciera T; Gandin A; Citron A; Piccolo S Biomaterials and Engineered Microenvironments to Control YAP/TAZ-Dependent Cell Behaviour. Nat. Mater 2018, 17 (12), 1063–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Walker M; Pringle EW; Ciccone G; Oliver-Cervelló L; Tassieri M; Gourdon D; Cantini M Mind the Viscous Modulus: The Mechanotransductive Response to the Viscous Nature of Isoelastic Matrices Regulates Stem Cell Chondrogenesis. Adv. Healthc. Mater 2024, 2302571, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Elosegui-Artola A; Gupta A; Najibi AJ; Seo BR; Garry R; Tringides CM; de Lázaro I; Darnell M; Gu W; Zhou Q; Weitz DA; Mahadevan L; Mooney DJ Matrix Viscoelasticity Controls Spatiotemporal Tissue Organization. Nat. Mater 2023, 22 (1), 117–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Dwivedi N; Das S; Bellare J; Majumder A Viscoelastic Substrate Decouples Cellular Traction Force from Other Related Phenotypes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2021, 543, 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Cameron AR; Frith JE; Gomez GA; Yap AS; Cooper-White JJ The Effect of Time-Dependent Deformation of Viscoelastic Hydrogels on Myogenic Induction and Rac1 Activity in Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Biomaterials 2014, 35 (6), 1857–1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Chaudhuri O; Gu L; Darnell M; Klumpers D; Bencherif SA; Weaver JC; Huebsch N; Mooney DJ Substrate Stress Relaxation Regulates Cell Spreading. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Cai G.-g.; Zheng A; Tang Q; White ES; Chou CF; Gladson CL; Olman MA; Ding Q Downregulation of FAK-Related Non-Kinase Mediates the Migratory Phenotype of Human Fibrotic Lung Fibroblasts. Exp. Cell Res 2010, 316 (9), 1600–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Patten J; Halligan P; Bashiri G; Kegel M; Bonadio JD; Wang K EDA Fibronectin Microarchitecture and YAP Translocation during Wound Closure. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2025, 11, 2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Patten J; Wang K Fibronectin in Development and Wound Healing. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2021, 170, 353–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Garrison CM; Schwarzbauer JE Fibronectin Fibril Alignment Is Established upon Initiation of Extracellular Matrix Assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 2021, 32 (8), 739–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Chen K; Kwon SH; Henn D; Kuehlmann BA; Tevlin R; Bonham CA; Griffin M; Trotsyuk AA; Borrelli MR; Noishiki C; Padmanabhan J; Barrera JA; Maan ZN; Dohi T; Mays CJ; Greco AH; Sivaraj D; Lin JQ; Fehlmann T; Mermin-Bunnell AM; Mittal S; Hu MS; Zamaleeva AI; Keller A; Rajadas J; Longaker MT; Januszyk M; Gurtner GC Disrupting Biological Sensors of Force Promotes Tissue Regeneration in Large Organisms. Nat. Commun 2021, 12 (1), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Wang WY; Pearson AT; Kutys ML; Choi CK; Wozniak MA; Baker BM; Chen CS Extracellular Matrix Alignment Dictates the Organization of Focal Adhesions and Directs Uniaxial Cell Migration. APL Bioeng 2018, 2 (4), 046107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Kenny FN; Drymoussi Z; Delaine-Smith R; Kao AP; Laly AC; Knight MM; Philpott MP; Connelly JT Tissue Stiffening Promotes Keratinocyte Proliferation through Activation of Epidermal Growth Factor Signaling. J. Cell Sci 2018, 131 (10), jcs215780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Schindelin J; Arganda-Carreras I; Frise E; Kaynig V; Longair M; Pietzsch T; Preibisch S; Rueden C; Saalfeld S; Schmid B; Tinevez JY; White DJ; Hartenstein V; Eliceiri K; Tomancak P; Cardona A Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9 (7), 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Tinevez JY; Perry N; Schindelin J; Hoopes GM; Reynolds GD; Laplantine E; Bednarek SY; Shorte SL; Eliceiri KW TrackMate: An Open and Extensible Platform for Single-Particle Tracking. Methods 2017, 115 (2017), 80–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Qin S; Clark RAF; Rafailovich MH Establishing Correlations in the En-Mass Migration of Dermal Fibroblasts on Oriented Fibrillar Scaffolds. Acta Biomater 2015, 25, 230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hadjipanayi E; Mudera V; Brown RA Guiding Cell Migration in 3D: A Collagen Matrix with Graded Directional Stiffness. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 2009, 66 (3), 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Hopp I; Michelmore A; Smith LE; Robinson DE; Bachhuka A; Mierczynska A; Vasilev K The Influence of Substrate Stiffness Gradients on Primary Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Biomaterials 2013, 34 (21), 5070–5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Missirlis D; Spatz JP Combined Effects of PEG Hydrogel Elasticity and Cell-Adhesive Coating on Fibroblast Adhesion and Persistent Migration. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15 (1), 195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Petrie RJ; Doyle AD; Yamada KM Random versus Directionally Persistent Cell Migration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2009, 10 (8), 538–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Brugués A; Anon E; Conte V; Veldhuis JH; Gupta M; Colombelli J; Muñoz JJ; Brodland GW; Ladoux B; Trepat X Forces Driving Epithelial Wound Healing. Nat. Phys 2014, 10 (9), 683–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Venugopal B; Mogha P; Dhawan J; Majumder A Cell Density Overrides the Effect of Substrate Stiffness on Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells’ Morphology and Proliferation. Biomater. Sci 2018, 6 (5), 1109–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Vazquez K; Saraswathibhatla A; Notbohm J Effect of Substrate Stiffness on Friction in Collective Cell Migration. Sci. Rep 2022, 12 (1), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Ma K; Kwon SH; Padmanabhan J; Duscher D; Trotsyuk AA; Dong Y; Inayathullah M; Rajadas J; Gurtner GC Controlled Delivery of a Focal Adhesion Kinase Inhibitor Results in Accelerated Wound Closure with Decreased Scar Formation. J. Invest. Dermatol 2018, 138 (11), 2452–2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Chen K; Henn D; Januszyk M; Barrera JA; Noishiki C; Bonham CA; Griffin M; Tevlin R; Carlomagno T; Shannon T; Fehlmann T; Trotsyuk AA; Padmanabhan J; Sivaraj D; Perrault DP; Zamaleeva AI; Mays CJ; Greco AH; Kwon SH; Leeolou MC; Huskins SL; Steele SR; Fischer KS; Kussie HC; Mittal S; Mermin-Bunnell AM; Diaz Deleon NM; Lavin C; Keller A; Longaker MT; Gurtner GC Disrupting Mechanotransduction Decreases Fibrosis and Contracture in Split-Thickness Skin Grafting. Sci. Transl. Med 2022, 14 (645), 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Oncel S; Wang Q; Elsayed AAR; Vomhof-DeKrey EE; Brown ND; Golovko MY; Golovko SA; Gallardo-Macias R; Gurvich VJ; Basson MD Sustained Intestinal Epithelial Monolayer Wound Closure after Transient Application of a FAK-Activating Small Molecule. PLoS One 2024, 19 (8), e0304010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Welf ES; Ahmed S; Johnson HE; Melvin AT; Haugh JM Migrating Fibroblasts Reorient Directionality: By a Metastable, PI3K-Dependent Mechanism. J. Cell Biol 2012, 197 (1), 105–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Kim NG; Gumbiner BM Adhesion to Fibronectin Regulates Hippo Signaling via the FAK-Src-PI3K Pathway. J. Cell Biol 2015, 210 (3), 503–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Cheng B; Li M; Wan W; Guo H; Genin GM; Lin M; Xu F Predicting YAP/TAZ Nuclear Translocation in Response to ECM Mechanosensing. Biophys. J 2023, 122 (1), 43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Noguchi S; Saito A; Nagase T YAP/TAZ Signaling as a Molecular Link between Fibrosis and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2018, 19 (11), 3674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Giménez A; Duch P; Puig M; Gabasa M; Xaubet A; Alcaraz J Dysregulated Collagen Homeostasis by Matrix Stiffening and TGF-Β1 in Fibroblasts from Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Patients: Role of FAK/Akt. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2017, 18 (11), 2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Li G; Li YY; Sun JE; Lin WH; Zhou RX ILK-PI3K/AKT Pathway Participates in Cutaneous Wound Contraction by Regulating Fibroblast Migration and Differentiation to Myofibroblast. Lab. Investig 2016, 96 (7), 741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Carraher CL; Schwarzbauer JE Regulation of Matrix Assembly through Rigidity-Dependent Fibronectin Conformational Changes. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288 (21), 14805–14814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Dludla PV; Jack B; Viraragavan A; Pheiffer C; Johnson R; Louw J; Muller CJF A Dose-Dependent Effect of Dimethyl Sulfoxide on Lipid Content, Cell Viability and Oxidative Stress in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Toxicol. Reports 2018, 5 (March), 1014–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).De Abreu Costa L; Henrique Fernandes Ottoni M; Dos Santos M; Meireles A; Gomes de Almeida V; De Fatima Pereira W; Alves de Avelar-Freitas B; Eustaquio Alvim Brito-Melo G Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) Decreases Cell Proliferation and TNF-α, IFN-, and IL-2 Cytokines Production in Cultures of Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes. Molecules 2017, 22 (11), 1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Hammoudeh SM; Hammoudeh AM; Hamoudi R High-Throughput Quantification of the Effect of DMSO on the Viability of Lung and Breast Cancer Cells Using an Easy-to-Use Spectrophotometric Trypan Blue-Based Assay. Histochem. Cell Biol 2019, 152 (1), 75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Yuan C; Gao J; Guo J; Bai L; Marshall C; Cai Z; Wang L; Xiao M Dimethyl Sulfoxide Damages Mitochondrial Integrity and Membrane Potential in Cultured Astrocytes. PLoS One 2014, 9 (9), e107447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Gironi B; Kahveci Z; McGill B; Lechner BD; Pagliara S; Metz J; Morresi A; Palombo F; Sassi P; Petrov PG Effect of DMSO on the Mechanical and Structural Properties of Model and Biological Membranes. Biophys. J 2020, 119 (2), 274–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Verheijen M; Lienhard M; Schrooders Y; Clayton O; Nudischer R; Boerno S; Timmermann B; Selevsek N; Schlapbach R; Gmuender H; Gotta S; Geraedts J; Herwig R; Kleinjans J; Caiment F DMSO Induces Drastic Changes in Human Cellular Processes and Epigenetic Landscape in Vitro. Sci. Rep 2019, 9 (1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Tunçer S; Gurbanov R; Sheraj I; Solel E; Esenturk O; Banerjee S Low Dose Dimethyl Sulfoxide Driven Gross Molecular Changes Have the Potential to Interfere with Various Cellular Processes. Sci. Rep 2018, 8 (1), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Wu CC; Su HW; Lee CC; Tang MJ; Su FC Quantitative Measurement of Changes in Adhesion Force Involving Focal Adhesion Kinase during Cell Attachment, Spread, and Migration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2005, 329 (1), 256–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Taneja N; Bersi MR; Rasmussen ML; Gama V; Merryman WD; Burnette DT Inhibition of Focal Adhesion Kinase Increases Myofibril Viscosity in Cardiac Myocytes. Cytoskeleton 2020, 77 (9), 342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Yu H; Gao M; Ma Y; Wang L; Shen Y; Liu X Inhibition of Cell Migration by Focal Adhesion Kinase: Time-Dependent Difference in Integrin-Induced Signaling between Endothelial and Hepatoblastoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Med 2018, 41 (5), 2573–2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Hu YL; Lu S; Szeto KW; Sun J; Wang Y; Lasheras JC; Chien S FAK and Paxillin Dynamics at Focal Adhesions in the Protrusions of Migrating Cells. Sci. Rep 2014, 4, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Han SJ; Bielawski KS; Ting LH; Rodriguez ML; Sniadecki NJ Decoupling Substrate Stiffness, Spread Area, and Micropost Density: A Close Spatial Relationship between Traction Forces and Focal Adhesions. Biophys. J 2012, 103 (4), 640–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Wang X; Yang Y; Wang Y; Lu C; Hu X; Kawazoe N; Yang Y; Chen G Focal Adhesion and Actin Orientation Regulated by Cellular Geometry Determine Stem Cell Differentiation via Mechanotransduction. Acta Biomater 2024, 182, 81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Driscoll TP; Cosgrove BD; Heo SJ; Shurden ZE; Mauck RL Cytoskeletal to Nuclear Strain Transfer Regulates YAP Signaling in Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Biophys. J 2015, 108 (12), 2783–2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Carlson M; Prall A; Gums J; Lesiak A; Shostrom V Biologic Variability of Human Foreskin Fibroblasts in 2D and 3D Culture: Implications for a Wound Healing Model. BMC Res. Notes 2009, 2, 229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Smithmyer ME; Cassel SE; Kloxin AM Bridging 2D and 3D Culture: Probing Impact of Extracellular Environment on Fibroblast Activation in Layered Hydrogels. AIChE J 2019, 65 (12), 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.