ABSTRACT

Methylorubrum extorquens AM1, a native formate-utilizing bacterium, has exhibited limited capacity to tolerate formate. In this study, we employed an adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) strategy to develop an evolved strain FT3 derived from M. extorquens AM1, with enhanced formate tolerance. When cultivated with a mixture of carbon sources containing 90 mM formate and 30 mM methanol, the FT3 strain exhibited 5.3 times higher optical density (OD600) compared to the parental strain. FT3 strain was shown to efficiently utilize both methanol and formate in experiments using 13C-labeled carbon sources. Furthermore, the mechanism underlying the enhanced formate tolerance in FT3 strain was investigated through a combination of DNA re-sequencing, transcriptome analysis, and ALE-inspired gene manipulation experiments. The FT3 strain was identified as a hypermutant, and its enhanced formate tolerance was attributed to increased formate transport, an improved methanol oxidation pathway, and enhanced formate oxidation and assimilation pathways. In addition, gene overexpression experiments indicated the involvement of genes META1_0287*, META1_3027, META1_3028, META1_3029, META1_1261, META1_1418, and META1_2965 in formate tolerance. Notably, the addition of formate resulted in a significant improvement in the generation of NADH and NADPH in the FT3 strain. Moreover, using the FT3 strain as a chassis, an improved 3-hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP) production of 2.47 g/L through fed-batch fermentation was achieved. This study provides an important foundation for further engineering of the evolved M. extorquens strain as an efficient platform for the co-utilization of methanol and formate in the production of reduced chemicals.

IMPORTANCE

In the present study, we successfully obtained an evolved strain FT3 derived from M. extorquens AM1 with high formate tolerance using the ALE strategy. The FT3 strain was identified as a hypermutant, with its enhanced formate tolerance attributed to increased formate transport, an improved methanol oxidation pathway, and enhanced formate oxidation and assimilation pathways. Through transcriptome analysis and ALE-inspired gene manipulation experiments, we identified several genes that contribute to the FT3 strain’s tolerance to formate. The enhanced levels of reducing equivalents and the increased tolerance to 3-HP make FT3 a suitable chassis for 3-HP production, achieving an improved yield of 2.47 g/L through fed-batch fermentation. This study provides an important foundation for further engineering of the evolved M. extorquens strain as an efficient platform for the co-utilization of methanol and formate in the production of reduced chemicals.

KEYWORDS: Methylorubrum extorquens, formate-utilizing bacterium, adaptive laboratory evolution, formate oxidation and assimilation pathway, 3-hydroxypropionic acid production

INTRODUCTION

Currently, fossil fuels and sugar-based raw materials are still the main sources used to produce value-added chemicals, which not only compete with human consumption but also threaten food security (1, 2). In addition, the extensive use of fossils has led to energy shortages and the emission of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2), which has spurred global concerns. Therefore, there is an urgency to develop green and sustainable approaches to access chemical production, rather than relying on fossil fuels and sugars (1, 2). Among the methods, the electrochemical reduction of CO2 to formate is a promising avenue of research (3–6). Formate has become a mediator between the physico-chemical and biological realms, as it can serve as the sole carbon and energy source for microbial growth (2). Furthermore, formate has emerged as an alternative feedstock for microbial fermentation due to its relatively low cost, high abundance, and high solubility (3, 4, 7).

Native formatotrophic microbes employ two different strategies to grow on formate. In the first strategy, the reducing equivalents generated from the oxidation of formate support carbon fixation through the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle and promote cell growth, which has been identified in Cupriavidus necator and Paracoccus denitrificans (8–10). The second strategy involves the direct condensation of formate with tetrahydrofolate (THF), catalyzed by formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase. This leads to the production of the intermediate formyl-THF, which serves as a precursor for several pathways, including the reductive acetyl-CoA pathway (also known as the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway), the serine cycle, and the reductive glycine pathway (10–15). The application of native formate-utilizing microbes is currently constrained by a number of factors, including their slow growth and low titer and yield of the chemical production (7, 16–18). To address these issues and render formate a more feasible carbon source in biorefinery applications, the adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) has been conducted with native formate-utilizing microbes, such as Thermococcus onnurineus and C. necator (19, 20). This approach has resulted in a notable enhancement in the tolerance and utilization of formate by the evolved microbes. More recently, the formate assimilation pathways have been introduced into traditional industrial microorganisms, such as Escherichia coli and yeast, thereby creating the synthetic formatotrophic microbes (21–26). The combination of ALE technology with synthetic formatotrophic microbes has demonstrated the enhanced formate tolerance and utilization (21, 23, 25, 26). However, the growth of synthetic microbes generally requires the utilization of other carbon sources, with a notable reduction in efficiency compared to traditional carbon sources (21–26).

Methylorubrum extorquens AM1 (also known as Methylobacterium extorquens AM1) is a representative of methylotrophs capable of utilizing one-carbon compounds (such as methanol and formate) as their carbon and energy source (13). Formate, the oxidative product of methanol, is an important branch point intermediate in methylotrophic metabolism as it can either be oxidized to CO2 to generate reducing equivalents or be condensed with THF to be assimilated through the serine cycle (27, 28). It has been observed that the addition of formate as a supplemental source significantly increases the reducing equivalents and enhances the production of chemicals such as mevalonate, poly-3-hydroxybutyrate, and polyhydroxyalkanoates in M. extorquens AM1 or its derivative strains (28–31). Nevertheless, despite being a native formatotroph, it has been demonstrated that a severe reduction in growth occurs when the formate concentration is increased to more than 20 mM (Fig. S1), which is significantly lower than the standard cultivation concentration of methanol (i.e., 120 mM). Such a low tolerance to formate restricts the potential for the use of high concentrations of formate in the bioprocess of M. extorquens AM1.

In this study, we employed the ALE method to obtain an evolved M. extorquens strain that exhibited tolerance to and assimilation of high concentrations of formate. Subsequently, we investigated the underlying mechanisms of formate tolerance through a combination of DNA re-sequencing, transcriptome analysis, and ALE-inspired gene manipulation experiments. Moreover, in comparison to the native M. extorquens AM1 host chassis, the production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP) was significantly increased in the evolved strain using the combined methanol and formate carbon sources. The present study highlighted the potential of the evolved M. extorquens strain with enhanced formate tolerance in the production of reduced chemicals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and culture conditions

The plasmids and strains used and generated in this study are listed in Table 1. All E. coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar or liquid medium with appropriate antibiotics at 37°C. The final concentrations of antibiotics used in this study were 20 µg/mL tetracycline (Tet), 25 µg/mL kanamycin (Km), and 80 µg/ml apramycin (Apr). Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals used in the culture medium were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids and strains used in this study

| Plasmid or strain | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pCM80 | Vector used for gene expression in M. extorquens AM1; promoter, PmxaF; antibiotics, TetR | (32) |

| pCM80-Apr | Vector used for gene expression in M. extorquens FT3; promoter, PmxaF; antibiotics, AprR | This study |

| pCM80-Apr-mcr | pCM80-Apr containing the operon PmxaF::mcr-Pmeta1_3616::mcr550–1219 from pYM07 for the synthesis of 3-HP | This study |

| pCM130 | Promoter probe vector with XylE as reporter | (32) |

| pCM130-PmxaF* | Plasmid carrying the mutated promoter PmxaF* to drive xylE | This study |

| pCM130-PmxaF | Plasmid carrying the promoter PmxaF to drive xylE | This study |

| pCM130-Pfdh2* | Plasmid carrying the mutated promoter Pfdh2* to drive xylE | This study |

| pCM130-Pfdh2 | Plasmid carrying the promoter Pfdh2 to drive xylE | This study |

| pYM07 | pCM80 derivative strain harboring PmxaF::mcr-Pmeta1_3616::mcr550–1219 | (33) |

| pCM80-0287 | Plasmid overexpressing the gene META1_0287 | This study |

| pCM80-0287* | Plasmid overexpressing the mutated gene META1_0287* | This study |

| pCM80-2965 | Plasmid overexpressing the gene META1_2965 | This study |

| pCM80-3029 | Plasmid overexpressing the gene META1_3029 | This study |

| pCM80-1261 | Plasmid overexpressing the gene META1_1261 | This study |

| pCM80-1418 | Plasmid overexpressing the gene META1_1418 | This study |

| pCM80-3027 | Plasmid overexpressing the gene META1_3027 | This study |

| pCM80-3028 | Plasmid overexpressing the gene META1_3028 | This study |

| pCM80-1261-1260 | Plasmid overexpressing the genes META1_1261 and META1_1260 | This study |

| pCM80-3028-3027 | Plasmid overexpressing the genes META1_3028 and META1_3027 | This study |

| pCM80-3028-3027-3029 | Plasmid overexpressing the genes META1_3028, META1_3027, and META1_3029 | This study |

| pCM433-MxaF* | Plasmid for homologous exchange of PmxaF promoter of MxaF with PmxaF* | This study |

| pCM433-PmxaF-P3028-3027 | Plasmid for homologous exchange of a native promoter of the operon META1_3028-META1_3027 with PmxaF promoter | This study |

| Strains | ||

| M. extorquens AM1 | Wild-type strain | (9) |

| M. extorquens AM1ΔcelAB | The gene celAB was knocked out in M. extorquens AM1 | This study |

| FT1 to FT12 | Adaptively evolved strains of WTKC with formate tolerance | This study |

| M. extorquens AM1ΔcelAB-Pro | M. extorquens AM1ΔcelAB carrying the plasmid pYM07 | This study |

| FT3::pCM80-Apr-mcr | FT3 carrying the plasmid pCM80-Apr-mcr | This study |

| AM1::pCM130-PmxaF* | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM130-PmxaF* | This study |

| AM1::pCM130-PmxaF | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM130-PmxaF | This study |

| AM1-MxaF* | The promoter of PmxaF in AM1 is replaced by the mutated PmxaF* | This study |

| AM1::pCM130-Pfdh2* | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM130-Pfdh2* | This study |

| AM1::pCM130-Pfdh2 | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM130-Pfdh2 | This study |

| AM1::pCM80-0287 | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM80-0287 | This study |

| AM1::pCM80-0287* | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM80-0287* | This study |

| AM1::pCM80-2965 | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM80-2965 | This study |

| AM1::pCM80-3029 | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM80-3029 | This study |

| AM1::pCM80-1261 | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM80-1261 | This study |

| AM1::pCM80-1418 | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM80-1418 | This study |

| AM1::pCM80-3027 | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM80-3027 | This study |

| AM1::pCM80-3028 | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM80-3028 | This study |

| AM1::pCM80-1261-1260 | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM80-1261-1260 | This study |

| AM1::pCM80-3028-3027 | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM80-3028-3027 | This study |

| AM1::pCM80-3028-3027-3029 | M. extorquens AM1 carrying the plasmid pCM80-3028-3027-3029 | This study |

| AM1-PmaxF-3028-3027 | The operon of META1_3028 and META1_3027M in M. extorquens AM1 is driven by promoter PmaxF | This study |

| E. coli DH5α | Gene cloning in host bacteria | Lab storage |

| E. coli Top10 | Gene cloning in host bacteria | Lab storage |

Analysis of growth and biomass

M. extorquens AM1 and its derivative strains were first cultivated as seed cultures in test tubes according to previously described methods. The seed cultures were then transferred to 250 mL flasks containing 50 mL of Hypho minimal medium with different carbon sources (34). Unless otherwise noted, 120 mM methanol or 150 mM methanol was used as the sole carbon source. For cultivating the M. extorquens FT3 with different carbon sources, 34 mM ethanol, 5 mM acetate, 68 mM 1,2-propanediol, or 36 mM pyruvate was used as the sole carbon source. To investigate the tolerance of the FT3 strain to 3-HP or formaldehyde, the M. extorquens FT3 strains were first cultivated with 120 mM methanol to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8. Then, 3-HP was added at final concentrations of 100 mg/L, 200 mg/L, 500 mg/L, and 1,000 mg/L, while formaldehyde was added at final concentrations of 2.5 mM, 5 mM, 7.5 mM, 10 mM, and 12.5 mM. For investigating the derivative strains with overexpressing genes, these strains were cultivated with 120 mM methanol and 10 mM, 15 mM, or 20 mM formate, respectively.

All the tubes or flasks were incubated on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm and 30°C with an initial OD600 of approximately 0.02. A 0.5 mL sample was taken at each time point for OD600 measurement using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Genesys10S, CA, USA). The specific growth rates were calculated by fitting an exponential growth model using Curve Fitter software (35). The presented specific growth rates represent the mean plus standard deviations calculated from triplicate biological replicates.

ALE of M. extorquens AM1

The ALE of the M. extorquens AM1 strain (celAB deleted) was conducted using Hypho medium at 30°C. One colony of M. extorquens AM1ΔcelAB strain was initially inoculated into the flask for cultivation on medium with 90 mM methanol and 30 mM sodium formate, with four parallel cultures prepared. ALE was then conducted through serial transfer every 48 hours. After 10 passages of ALE (approximately 10th generation), the maximum biomass of the AM1 strain gradually increased from an OD600 of 0.2 to 1.2. The microbial dilutions were then plated on solid media containing methanol and sodium formate as the carbon sources. Three individual colonies were selected from each plate, resulting in a total of 12 colonies for further subculture. During the subculture process, the methanol concentration in the medium was gradually decreased from 90 mM to 30 mM, while the concentration of sodium formate was increased from 30 mM to 90 mM. For each adjustment, 5 mM of sodium formate was added, and 5 mM of methanol was removed. This adjustment was continued until the OD600 value of each subculture became stable. At the 30th, 90th, 150th, 250th, and 300th generation (corresponding to 15th, 25th, 35th, 55th, and 70th passages, respectively), the maximum OD600 and formate uptake rates were measured, respectively. After 300 generations, the 12 evolved lineages showed significant growth on medium containing 90 mM sodium formate and 30 mM methanol. Then the strains from the 12 evolved lineages were plated on solid media containing 90 mM sodium formate and 30 mM methanol. Based on morphology, one large colony was selected for each evolved lineage and further evaluated for specific growth rate under cultivation with either 90 mM sodium formate and 30 mM methanol or 120 mM formate.

Measurement of methanol, formate, and 3-HP concentrations in the culture medium

To determine the concentrations of methanol, sodium formate, and 3-HP in the culture medium or fermentation broth, a subculture of 800 µL was harvested and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was then filtered using a 0.22 µm membrane and subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis as described previously (36). The HPLC analysis was performed on Wooking K2025 (China) equipped with a PDA (K2025DAD, Wooking Corporation, China) and a refractive index detector (RID-20A, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan). The analytical procedures were as follows: the mobile phase sample volume was 30 µL, with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 65°C and the detector temperature at 35°C.

Measurement of carotenoids from the evolved strain M. extorquens FT3

M. extorquens FT3 was cultivated in Hypho medium containing either 120 mM methanol, 90 mM methanol and 30 mM formate, or 60 mM methanol and 60 mM formate. Three replicates were prepared for each culture condition. After a cultivation period of 4 days, the broths were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 3 min. The resulting pellets were then extracted and analyzed according to the method described previously (34).

Determination of 13C-labeled amino acids in the M. extorquens FT3 strain

For the 13C labeling assay, the evolved strain FT3 was cultivated using two different carbon sources: 90 mM 13C-labeled sodium formate and 30 mM methanol, and 90 mM sodium formate and 30 mM 13C methanol. When the FT3 strain reached an OD600 of 0.6, the cells were collected from a 20 mL culture using a percolator with a 0.22 µm filter membrane. Protein extraction was performed as previously described with slight modifications (37, 38). The collected cells were rapidly frozen using liquid nitrogen and then dried in a lyophilizer for 12 hours. 20 mL of boiling water was then added and incubated in a water bath at 100°C for 10 min, vortexing three times for approximately 5 seconds each time. Next, the proteins were precipitated at 0°C for 20 minutes and centrifuged twice at 5,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was hydrolyzed by using 1 mL of 6 M HCl at 105°C for 24 hours. HCl was removed using a nitrogen blower, and the hydrolyzed samples were re-dissolved in 500 µL of ddH2O and filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane. For derivatization, 50 µL of solvent was evaporated and re-dissolved in 50 µL of 25 mg/mL methoxylamine hydrochloride in pyridine was added to the samples, which were incubated at 60°C for 30 minutes and vortexed occasionally. Then, 50 µL of N-methyl-N-trimethylsilyltrifluoroacetamide was added, and the samples were incubated at 30°C for an additional 90 minutes. After the derivatization reactions, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was subjected to GC-MS. The derivatized amino acid samples were analyzed by GC/Q-TOF-MS with an Agilent 5975B/6890N gas chromatography-mass spectrometer equipped with an HP-5MS (30 m × 0.25 mm×0.25 µm) chromatographic column. The carrier gas used was ultra-high-pressure pure helium, with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The injection volume was set at 1 µL in the no-shunt mode. The injection port and transfer tube temperatures were kept at 280°C. The temperature gradient for the column was as follows: starting at 60°C for 0.25 minutes, with an increase of 5 °C/min until reaching 280°C, and holding this temperature for 10 minutes. Mass spectra of amino acids were in the mass range of 50–650 m/z at an acquisition rate of 5 spectra/s. The ion source temperature was set at 230°C. Finally, the resulting data from the chromatographic mass spectra were analyzed using GC-MS analytical software.

Whole-genome sequencing of the M. extorquens FT3 strain

Genomic DNA was extracted from the evolved strain FT3 using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega (Beijing) Biotech Co., China). The genomic DNA sequencing was performed by Novogene (Tianjing, China) using the PacBio RS II platform. The process followed Novogene’s standardized protocols.

Transcriptome analysis

The M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain was cultivated on medium with 150 mM methanol as the carbon source. The M. extorquens FT3 strain was cultivated with medium containing either 150 mM methanol or a combination of 120 mM methanol and 30 mM formate. Three parallels were prepared for each sample. Cells were collected during the middle exponential phase by centrifugation at 4°C for RNA isolation. RNA preparation, library construction, and RNA sequencing were conducted by Novogene (Tianjin, China). The quality of raw sequence reads was evaluated using the FASTQC software (v.0.10.1). Low-quality reads and bases from both ends of raw Illumina reads were removed and trimmed using the NGSQC Toolkit (v.2.3.3). BWA alignment software (v.0.7.17) was used to align the high-quality reads against the M. extorquens AM1 reference genome. SAM tools software (v.1.9) was used to sort and index the mapping results. Raw read counts from the resulting BAM files were obtained using HTSeq software (v.0.11.2). The raw-count table was further processed using the DESeq function of the DESeq2 package (v.1.18.1) to obtain gene expression data. Genes with a false discovery rate (FDR) P-value < 0.05 and log2 (fold change) >0.5 or < −0.5 were considered to be differentially expressed. Pearson’s linear correlation coefficients between variables were calculated using the R package “stats” and plotted using “corrplot.”

Measurement of NADH and NADPH

The M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain was cultivated on medium with 120 mM methanol as the carbon source. The M. extorquens FT3 strain was cultivated with medium containing either 120 mM methanol or a combination of 90 mM methanol and 30 mM formate. Three parallels were prepared for each sample. When the strains reached an OD600 of approximately 0.6, 10 mL of cells were collected by centrifugation to measure the intracellular concentrations of NADH and NADPH. The collected samples were immediately quenched with liquid nitrogen and then dried using a freeze-dryer at −45°C. NADH and NADPH were extracted, and the concentrations were determined as previously described with minor revisions (39, 40). Briefly, 1 mL of buffer (300 mM KOH, 1% Triton X-100) was added to the samples, followed by incubation in a water bath at 85°C for 3 minutes with occasional shaking. The samples were then cooled on ice for an additional 3 minutes and centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and the pH was adjusted to 10 with potassium perchlorate. After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 15 minutes, the supernatant was subjected to HPLC analysis. The analyses of NADH and NADPH were performed on HPLC equipped with a NovaPac C18 RP column (3.9 × 150 mm, 60 Å, 4 µm, Waters) with elution gradient conditions as follows: 0–4 min, 100% mobile phase A; 4–18 min, 0%–30% mobile phase B; 18–23 min, 30%–100% mobile phase B; 23–25 min, 100% mobile phase B; 25–26 min, 100% mobile phase A; 26–50 min, 100% mobile phase A.

Gene overexpression and gene mutation in M. extorquens AM1

The plasmid of pCM80 was used for gene overexpression in the M. extorquens strains. The targeted genes were amplified from the genomic DNA of the M. extorquens strains by PCR using the corresponding primers. The PCR products were inserted into the pCM80 plasmid under the control of the PmxaF promoter using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme Biotech, China). The resulting plasmids were introduced into the M. extorquens strains by electroporation. The M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain and SNP mutant strains were obtained from the M. extorquens strains using previously described methods (34). The genotypes of the M. extorquens derivatives were verified by PCR and DNA sequencing.

Determining the activities of FDH

The 50 mL of the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB and M. extorquens FT3 strains was, respectively, collected by centrifugation when the OD600 reached 0.8. The cells were washed twice, resuspended in 50 mM Tricine-KOH buffer (pH 7.0), and lysed using a French pressure cell at 1.2 × 108 Pa. After centrifugation for 10 min at 12,000 × g, the supernatants were transferred to a new tube, and the final volume was adjusted to 7 mL with 50 mM Tricine-KOH buffer (pH 7.0). The protein concentration in the crude extract was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Sangon Biotech., China). The measurements were performed at room temperature. The reaction system containing 0.5 mM NAD+ and 1 mg/mL crude extract proteins was used to assay the FDH activity. The formate dehydrogenase activity was determined as described previously (41). Enzyme assays were performed in triplicate.

Determination of the promoter strength using XylE-based experiments

The promoter strengths were determined using XylE-based experiments. The PmxaF and Pfdh2 promoters were amplified from the genomic DNA of the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain, and the PmxaF* and Pfdh2* promoters with SNP mutations were amplified from the genomic DNA of the M. extorquens FT3 strain. The PCR fragments were inserted into the pCM130 vector to control the expression of xylE. The resulting plasmids were separately introduced into M. extorquens AM1. These M. extorquens AM1 strains were cultivated on medium containing 120 mM methanol, and the cells were collected when the OD600 reached 0.8. The cells were lysed using the One-Shot Press (Constant Systems Cell Disruptor, Constant Systems, UK). The debris was discarded by centrifugation, and the supernatant was used to detect catechol dioxygenase activity as described previously (41). The reaction system, containing 5 mM catechol and 4 mg/mL crude extract proteins, was used for the assay of catechol dioxygenase activity. Enzyme assays were performed in triplicate.

Fed-batch fermentation of M. extorquens FT3::pCM80-Apr-mcr

The 3-HP synthetic operon was amplified from the plasmid of pYM07 and then inserted into pCM80-Apr to generate the plasmid pCM80-Apr-mcr. The plasmid pCM80-Apr-mcr was further introduced into the M. extorquens FT3 strain to generate the M. extorquens FT3::pCM80-Apr-mcr strain. The strain M. extorquens FT3::pCM80-Apr-mcr was initially cultivated as a seed culture in a 500 mL flask. When the culture reached an OD600 of approximately 1.0, it was transferred to a 3 L fermenter containing 1.7 L of Choi3 medium (5,370 mg/L Na2HPO4·12H2O, 1305 mg/L KH2PO4, 450 mg/L MgSO4·7H2O, 250 mg/L (NH4)2SO4, 10 mg/L Na2EDTA, 1 mg/L FeSO4·7H2O, 1.4 mg/L CaCl2·2H2O, 1 mg/L MnCl2·4H2O, 0.2 mg/L Na2MoO4·2H2O, 0.3 mg/L CuSO4·5H2O, 3.2 mg/L CoCl2·6H2O, 4.4 mg/L ZnSO4·7H2O). The initial fermentation conditions included a temperature of 30℃, a stirring speed of 500 rpm, and a ventilation rate of 1 L/min. The aeration rate (ranging from 1 to 3 L/min) and the stirring speed (ranging from 500 to 800 rpm) were adjusted based on the dissolved oxygen level to maintain it above 20%. The initial concentration of methanol was 120 mM, while the concentration of sodium formate was 21.2 mM. Methanol concentration was monitored using a methanol electrode, and the concentration of formate was kept within the range of 8 to 12.7 mM. During the fermentation, the pH value was maintained at 6.9 by adding 1M sodium hydroxide for about 40 hours. The nitrogen concentration was maintained at 1 to 2 g/L by adding ammonium sulfate. After 40 hours, measurements were taken every 6 hours to determine the OD600, methanol and formate consumption, dry cell weight, and 3-HP titer.

RESULTS

Generating the evolved strains with enhanced tolerance to formate using ALE

ALE was employed to evolve M. extorquens AM1 to achieve tolerance to a high concentration of formate. The growth of M. extorquens AM1 is severely inhibited when formate is present at concentrations up to 15 mM as the sole carbon source. Consequently, during the ALE process, methanol is used as an additional carbon source. M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB (this deletion can prevent cell aggregation in laboratory cultures) (42) was first cultivated on 90 mM methanol and 30 mM formate. ALE was then carried out through serial transfer every 48 hours. After 10 passages of ALE, the maximum biomass of M. extorquens AM1ΔcelAB gradually increased from the optical density (OD600) value of 0.2 to 1.2. In subsequent passages, the concentration of formate incrementally increased and the concentration of methanol decreased accordingly (Fig. 1A). Eventually, the evolved strains were able to grow on the medium containing 30 mM methanol and 90 mM formate, reaching a maximum OD600 of 1.12, which was 5.3 times higher than the parental M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain (Fig. 1B). The maximum biomass and formate consumption rate of the evolved strains at the 30th, 90th, 150th, 250th, and 300th generations were measured by cultivating with 30 mM methanol and 90 mM formate, respectively (Fig. 1B and C). A comparison of the formate consumption rates at the 30th and 300th generations revealed an increase from 1.98 mM .h−1 to 3.52 mM .h−1 (Fig. 1C). The evolved strains at the 300th generation exhibited a significantly enhanced level of biomass and formate consumption rate compared to the parental strain when grown on 30 mM methanol and 90 mM formate. Therefore, each colony of the evolved strains was isolated at the 300th generation, and 12 individual colonies (named as the FT1 strain to the FT12 strain) were selected for evaluation by cultivating them with 30 mM methanol and 90 mM formate, as well as with 120 mM formate.

Fig 1.

A summary of the evolved strains and an illustration of the isolated FT3 strain. (A) The scheme of evolution of the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain. For the 10th passage, the OD600 values were presented as the average of 4 replicates, while for the other passages, the OD600 values were presented as the average of 12 replicates, with the standard deviations indicated as error bars. (B) Growth of the 12 evolved populations over different generations cultivated with 30 mM methanol and 90 mM formate, with standard deviations indicated as error bars. (C) Formate consumption rate of the 12 evolved populations across different generations cultivated with 30 mM methanol and 90 mM formate, with standard deviations indicated as error bars. (D) Growth of the 12 isolated strains cultivated with 120 mM formate. (E) A comparison of the growth and formate consumption rates between the FT3 strain and the parental M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain when cultivated with 30 mM methanol and 90 mM formate. (F) A comparison of the growth between the FT3 strain and the parental M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain when cultivated with 120 mM methanol. In panels D, E, and F, the data were presented as the average of three replicates, with standard deviations indicated as error bars. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01).

Among the 12 colonies, the evolved strain FT3 strain exhibited the best performance when cultivated on a medium containing either a mixture of 30 mM methanol and 90 mM formate or only 120 mM formate (Fig. 1D; Fig. S2). When a mixture of formate and methanol was used as the carbon sources, the FT3 strain completely exhausted the 30 mM formate within 48 hours, whereas the parental M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain exhibited a significantly lower consumption rate, with only 30% of the formate consumed (Fig. 1E). The FT3 strain achieved a maximum OD600 of 0.35 when 120 mM formate was used as the sole carbon source, which was approximately three times higher than that of the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain (Fig. 1D). Moreover, when cultivated on a medium with methanol as the sole carbon source, the FT3 strain and the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain exhibited similar biomass accumulation, but the FT3 strain displayed a specific growth rate of 0.14 h−1, which was 28% higher than that of the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain (Fig. 1F). Notably, when cultivated with 120 mM methanol, the FT3 strain displayed a darker pink color compared to the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain (Fig. S3), indicating enhanced synthesis of C30 carotenoid pigment in the cell membrane of the FT3 strain. In addition, when comparing to the carotenoids in the FT3 strain cultivated with 120 mM methanol as the sole carbon source, the amounts of C30 carotenoids in the FT3 strain grown with 90 mM methanol and 30 mM formate, or 60 mM methanol and 60 mM formate, increased to 1.86-fold and 2.72-fold, respectively (Fig. S4). This finding indicated that increasing the formate concentration could enhance the synthesis of C30 carotenoids in the FT3 strain.

Next, we investigated whether the FT3 strain also performed well when exposed to other weak organic acids and alcohols. As shown in Fig. 2, the specific growth rates of the FT3 strain when cultivated with 34 mM ethanol, 68 mM 1,2-propanediol, and 36 mM pyruvate were 0.111 h−1, 0.072 h−1, and 0.175 h−1, respectively. These rates were 1.98-, 1.5-, and 2.92-fold higher than those observed for the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain. The maximum OD600 of the FT3 strain increased by 37.5% and 42.9% when cultivated with ethanol and 1,2-propanediol, respectively (Fig. 2; Fig. S5).

Fig 2.

A comparison of the maximum OD600 values (A) and specific growth rates (B) of the FT3 strain and its parental strain on different carbon sources, including 34 mM ethanol, 5 mM acetate, 36 mM pyruvate, and 68 mM 1,2-propanediol. The data were presented as the average of three replicates, with standard deviations indicated as error bars.

Analyzing the 13C-labeled amino acids in the FT3 strain

To assess the incorporation of formate and methanol into cellular biomass by the FT3 strain, 13C-labeled method was conducted to analyze the proteinogenic amino acids. The FT3 strain was cultivated on media containing two different 13C-labeled carbon sources: (i) 30 mM 13C-methanol and 90 mM 12C-formate or (ii) 30 mM 12C-methanol and 90 mM 13C-formate. When the FT3 strain was grown to an OD600 value of about 0.6, the cells were harvested and subjected to hydrolysis for GC-MS analysis (Fig. S6). All 10 detected proteinogenic amino acids, belonging to four groups, were 13C-labeled. These included glycine, alanine, serine, glutamate, proline, aspartate, valine, threonine, leucine, and isoleucine (Fig. 3). The average carbon labeling ratio of 10 proteinogenic amino acids when cultured with 30 mM 13C-methanol and 90 mM 12C-formate ranged from 10.1% to 33.7%, which was consistent with the ratio (25%) of 13C-labeled carbon source. When cultivated with 30 mM 12C-methanol and 90 mM 13C-formate, the labeled ratios of these amino acids were found to range from 59.4% to 67.5%, which was also in line with the ratio (75%) of labeled carbon source. Overall, these results suggested that the FT3 strain was capable of effectively co-utilizing formate and methanol.

Fig 3.

Analysis of the co-assimilation of methanol and formate using 13C-labeled carbon sources. (A) The 10 proteinogenic amino acids detected were synthesized from the intermediates involved in the serine cycle, TCA cycle, and ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway. (B) The labeling pattern and average carbon incorporation of proteinogenic amino acids in the FT3 strain cultivated with 13C-methanol and 12C-formate. (C) The labeling pattern and average carbon incorporation of proteinogenic amino acids in the FT3 strain cultivated with 13C-formate and 12C-methanol. M + X, where X indicates the number of 13C-labeled carbons. The data were presented as the average of three replicates, with standard deviations indicated as error bars.

Identification of the FT3 strain as a hypermutant strain with a considerable impact on the metabolic pathways

To uncover the mechanism of the increased tolerance and assimilation of formate, a comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic analysis was conducted on the FT3 strain. The genomic data indicated that the FT3 strain exhibited hypermutations, a trait that was different from the previously evolved strains derived from M. extorquens AM1 by ALE (43–46). A total of 5,551 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified in the coding sequence (CDS) regions of 459 genes, and 2,053 intergenic mutations and 31 insertion/deletion (Indel) mutations were identified in the genome of the FT3 strain (Data set S1). In addition to the proteins with unknown function, proteins with SNPs were classified into various pathways, including gluconeogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, the serine cycle, the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway (i.e., glyoxylate regeneration pathway), DNA replication and repair, secondary metabolism, amino acid metabolism, transporters, and enzymes involved in co-factor biosynthesis (Data set S1). The hypermutant property of the FT3 strain can be attributed to mutations in the DNA repair and DNA replication systems (Data set S1).

These SNPs, occurring within or in the intergenic regions of genes, exhibited significant impact on gene transcription. When the FT3 strain was cultivated on 150 mM methanol as the sole carbon source, a notable alteration in the transcription profile of the FT3 strain was observed in comparison to the M. extorquens AM1. Our findings revealed that 244 genes were upregulated and 2,430 genes were downregulated in the FT3 strain (Fig. S7). In the presence of 30 mM formate, the FT3 strain was found to exhibit only 244 upregulated genes and 90 downregulated genes (Fig. S8). It has been demonstrated that the majority of mutations are neutral, with only a small number conferring a beneficial allele (47). Consequently, identifying the pivotal genes involved in formate tolerance represented a substantial challenge. In this study, we employed the genomic and transcriptomic data to narrow down a list of candidate genes that were likely to be involved in formate tolerance and assimilation by identifying those that are in the central metabolic pathways.

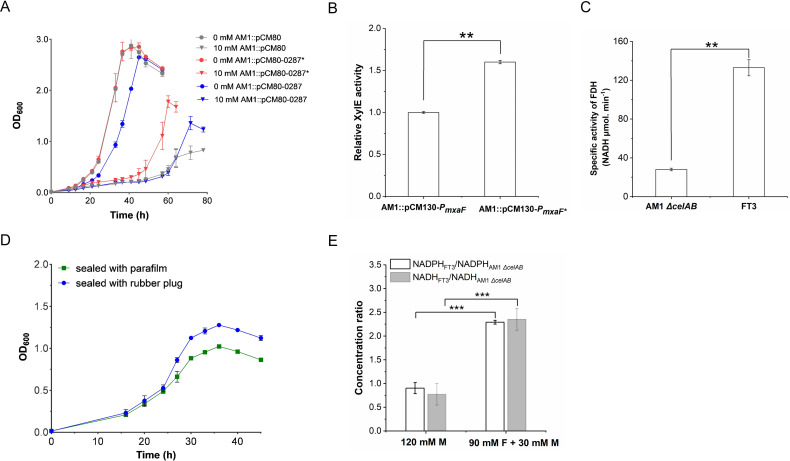

Mutation of the FocA homologue META1_0287 enhanced the transport of formate

A high concentration of formate can inhibit proton transfer across the cell membrane, which leads to the inhibition of ATP generation and consequently, the toxicity of cells (48, 49). To detoxify high concentrations of formate, it is necessary for formate to be transported into the cell and subsequently assimilated by the FT3 strain. The nitrate-formate transporter FocA and oxalate:formate antiporter have been reported to be capable of transporting formate into the cell (50, 51). Mutations have also been observed in the FocA homologue protein META1_0287 (E5Q) and the oxalate:formate antiporter META1_0992 in the FT3 strain (Data set S1). The transcription level of META1_0992 was considerably lower than that of META1_0287 when the FT3 strain was cultivated with 150 mM methanol. The transcriptional level of META1_0287 in the FT3 strain was observed to significantly increase to 3.41-fold in the presence of 30 mM formate (Fig. 4; Data set S2). Based on these findings, it was hypothesized that FocA homolog META1_0287 was responsible for the transport of formate into the cell in the FT3 strain. To test this hypothesis, the native META1_0287 and its mutated META1_0287* were overexpressed in the M. extorquens AM1 strain. Subsequently, the strains were cultivated on the medium with 120 mM methanol as the sole carbon source. The strain AM1::pCM80-0287* exhibited a similar specific growth rate to the control strain AM1::pCM80, which was slightly higher than the specific growth rate of the AM1::pCM80-0287 strain (Fig. 5A). The addition of 10 mM formate resulted in a shorter lag phase (30 hours) for the strain AM1::pCM80-0287* compared to both the strain AM1::pCM80 (60 hours) and the strain AM1::pCM80-0287 (60 hours) (Fig. 5A). Moreover, the strain AM1::pCM80-0287* reached a maximum OD600 value of 1.78, which was significantly higher than that of the strain AM1::pCM80-0287 and AM1::pCM80 (Fig. 5A). These results indicated that the E5Q mutation in the N-terminal of FocA homolog META1_0287* played a crucial role in formate tolerance. It has been demonstrated that FocA is capable of transporting formate in a pH-dependent manner, with the ability to transport formate in both protonated and neutralized forms (52). The presence of 10 mM sodium formate resulted in a pH increase from 7.27 to 8.15 within the first 25 hours (Fig. S9), suggesting that formate was transported into the cell in its protonated formic acid state, as previously reported (52).

Fig 4.

A detailed examination of the SNPs within the genomic and transcriptomic data of pivotal enzymes engaged in central metabolic pathways in the FT3 strain. Amino acid SNPs occurring in the CDS regions are marked in red, while nucleotide SNPs in the intergenic regions are marked in green. The data represented in black indicate the fold change in the gene transcription of the FT3 strain compared to the parental M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain, which was cultivated with 150 mM methanol. The fold change in gene transcription of the FT3 strain compared to the parental M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain in the presence of 120 mM methanol and 30 mM formate is shown with the data in blue. The data were presented as the average of three replicates. Significant differentially expressed genes were defined as having a (FDR) *P <0.05 and **P <0.01.

Fig 5.

The characteristics of the M. extorquens AM1 derivative strains. (A) Growth curves of the engineered strains harboring plasmid pCM80-based overexpression of the native nitrate-formate transporter gene META1_0287 and the mutated META1_0287* from M. extorquens FT3 in the presence of different formate concentrations. (B) Assessment of the promoter strength of Pmxaf from the M. extorquens AM1 strain and Pmxaf* (T159 to C159) from the FT3 strain through an XylE-based experiment. (C) Measurement of formate dehydrogenase (FDH) activity in the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain and the FT3 strain. (D) Growth curves of the FT3 strain cultivated on medium containing 90 mM formate and 30 mM methanol in flasks with two different sealing methods. (E) Comparison of the ratios of NADH and NADPH between the FT3 strain and the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain. The concentrations of NADPH and NADH in the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain were determined by cultivation in a medium containing 120 mM methanol (M), while the FT3 strain was cultivated in a medium containing either 120 mM methanol (M) or 90 mM formate (F) in combination with 30 mM methanol (M). The data were presented as the average of three replicates, with standard deviations indicated as error bars. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

Metabolic pathway of methanol oxidation to formate was significantly affected

The metabolic pathway of methanol oxidation to formate was found to be significantly affected. A number of mutations were identified in several regions, including the CDS region of the methanol dehydrogenase system MxaS (L135P) and MxcQ (G21K), the PQQ synthase PqqCD (I219M), and the formyltransferase/hydrolase complex Fhc (L204F) (Fig. 4). Moreover, an intergenic SNP mutation, T159 to C159, located 159 base pairs upstream of the methanol dehydrogenase gene mxaF was found (Fig. 4). The XylE-based experiment demonstrated that the T159 to C159 mutation resulted in a 60% increase in the promoter strength of mxaF (Fig. 5B). However, the engineered strain AM1-MxaF* harboring C159 mutation showed no enhancement on formate tolerance (Fig. S10), suggesting this mutation may not be related to formate tolerance or formate utilization. In comparison to the M. extorquens AM1 grown on 150 mM methanol, the transcriptomic data indicated that the transcription of the majority of genes involved in this process in the FT3 strain was enhanced, particularly mxaFJGI, mxaD, and pqqA. This suggested an increased conversion of methanol to formaldehyde (Fig. 4; Data set S2). However, when exposed to 30 mM formate, the transcriptional levels of fae and fhcA were significantly downregulated to 0.75- and 0.81-fold, indicating a decreased conversion of formaldehyde to formate (Fig. 4). The cultivation of the FT3 strain resulted in the increased absorption of formate by the mutated FocA homologue META1_0287* and an increase in the cellular formate concentration. Consequently, the conversion of formaldehyde to formate was decreased, thereby alleviating the formate stress. The enhanced conversion from methanol to formaldehyde and the decreased conversion from formaldehyde to formate led to an increased concentration of formaldehyde, suggesting that the FT3 strain could exhibit a higher tolerance to formaldehyde. Further investigation into formaldehyde tolerance also demonstrated that the FT3 strain exhibited tolerance up to 10 mM formaldehyde, whereas the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain showed tolerance up to 7.5 mM formaldehyde (Fig. S11).

Pathways related to formate metabolism were notably impacted in the FT3 strain

Formate can be converted to CO2 or be assimilated into the cell through the serine cycle coupled to the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway. The mutations involved in the formate assimilation pathways included the CDS regions of β-ketothiolase PhaA (Q168E), methylmalonyl-CoA mutase McmA (N703K), and succinyl-CoA/methylmalonyl-CoA mutase accessory protein MeaB (L11V). Moreover, the intergenic SNPs were observed in the serine hydroxymethyltransferase gene glyA (G205 to A205), malyl-CoA thioesterase gene mclA (G190 to A190), and fumarase gene fumC (T230 to C230) (Fig. 4). Transcriptomic data further revealed that most of the genes involved in the formate assimilation pathways exhibited enhanced transcription in the FT3 strain grown on 150 mM methanol, especially for ftfL, glyA, and mtkAB (Fig. 4), which are three key enzymes involved in the formate assimilation pathway (53). These genes were upregulated to 1.73-, 1.36-, and 1.64-fold, respectively (Fig. 4). Concerning the oxidation of the formate pathway, it was observed that SNP mutations occurred in the CDS region of the FDH genes of fdh4A (R98H and S142G) and fdh1B (S36A), as well as in the intergenic region of the fdh2CBAD operon (Fig. 4). Subsequently, the XylE-based experiments demonstrated that the G136 to T136 mutation located upstream of the fdh2CBAD operon had no influence on promoter strength, which was consistent with the transcriptomic data (Fig. S12). Notably, the transcription levels of fdh1A, fdh1B, fdh3A, fdh3B, and fdh3C in the FT3 strain grown on methanol were all downregulated significantly, with expression levels reduced to 0.26-, 0.22-, 0.61-, 0.66-, and 0.63-fold, respectively (Fig. 4). In the presence of 30 mM formate, the transcription levels of fdh1B, fdh2A, fdh2B, fdh2D, fdh3A, fdh3B, and fdh3C in the FT3 strain were upregulated significantly, whereas only fdh4A and fdh4B were downregulated to 0.42- and 0.43-fold, respectively (Fig. 4). Given the enhanced transcription of most of the FDH genes, we investigated whether the activity of FDH in the FT3 strain was also elevated. When compared to M. extorquens AM1 cultivated with 120 mM methanol, the specific activity of FDH in the FT3 strain cultivated with 90 mM methanol and 30 mM formate was 4.75 times higher than that in M. extorquens AM1 (Fig. 5C). As there were no significant changes in the transcription levels of the genes involved in the formate assimilation pathway in the presence of 30 mM formate, we speculated that the enhanced conversion of formate to CO2 resulted in increased carbon loss. This was supported by the previous observation that the maximum biomass of the FT3 strain was substantially decreased when cultivated on 90 mM formate and 30 mM methanol (Fig. 1D).

Interestingly, when exposed to 30 mM formate, two genes coding carbonate dehydratases META1_3028 and META1_1418, involved in reversible hydration of dissolved CO2 into carbonic acid, showed significant upregulation (Fig. 4). Therefore, we hypothesized that the FT3 strain utilized these two carbonate dehydratases to facilitate the dissolution of CO2 within the cell, whereby bicarbonate was formed. This can then be catalyzed by PEP carboxylase Ppc or propionyl-CoA carboxylase PccAB to synthesize oxaloacetate or methylmalonyl-CoA (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the cultivation of the FT3 strain in flasks sealed with either parafilm or a rubber plug demonstrated that, compared to the flask sealed with parafilm, the growth rate and maximum biomass of the FT3 strain increased by 11% and 21.4%, respectively, in flasks sealed with a rubber plug when 30 mM formate and 90 mM methanol were used as the carbon sources (Fig. 5D). When methanol was used as the sole carbon source, no difference was observed in the FT3 strain cultivated with flasks sealed with either parafilm or a rubber plug (Fig. S13). These results indicated that the emission of CO2 from the flask can be prevented by a rubber plug, which can be readily dissolved in the cell by enhanced carbonate dehydratase and subsequently utilized for intermediate synthesis, thereby improving biomass production.

The enhanced formate oxidation pathway could result in a high production of NADH, which could subsequently be converted to NADPH by the membrane-bound NADH/NADPH transhydrogenase. The mutations were observed in the transhydrogenases PntA (I12T) and PntB (D288G) (Fig. 4). When exposed to 30 mM formate, pntB was found to be upregulated to 1.29-fold (Fig. 4). Furthermore, we analyzed the pools of reducing equivalents in the FT3 strain. When the FT3 strain was cultivated with 120 mM methanol as the sole carbon source, the concentrations of NADH and NADPH were slightly lower than those of the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain (Fig. 5E). However, when the FT3 strain was cultivated in the presence of 30 mM formate, the concentrations of NADH and NADPH increased to 3.04-fold and 2.54-fold, respectively, in comparison with that grown on 120 mM methanol (Fig. 5E). Moreover, the concentrations of NADH and NADPH in the FT3 strain cultivated with 30 mM formate and 90 mM methanol were found to be 2.29-fold and 2.35-fold higher, respectively, than those observed in the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain grown on methanol (Fig. 5E). These results suggested that the production of reduced equivalents was improved in the FT3 strain with the addition of formate.

Assessing the genes that conferred tolerance to formate by using an ALE-inspired overexpression method

Among the top 20 significantly upregulated genes in the FT3 strain in the presence of 30 mM formate, two carbonate dehydratase genes (META1_3028 and META1_1418), a transporter gene META1_3027, an RNA polymerase sigma factor (META1_1261), and a transmembrane anti-sigma factor (META1_1260) were observed (Data set S2), which were found to be upregulated to 85.9-, 12.0-, 82.2-, 18.4-, and 32.6-fold, respectively. Furthermore, five hypothetical protein genes META1_3029, META1_3458, META1_2965, META1_2964, and META1_0394 were upregulated to 90.3-, 222.7-, 49.8-, 95.0-, and 7.5-fold, respectively. These genes were then overexpressed in M. extorquens AM1, respectively. Derivative strains with overexpression of META1_3027, META1_3028, META1_3029, META1_1261, and META1_1418 demonstrated enhanced growth in the presence of 10 mM formate compared to the M. extorquens AM1 strain with empty plasmid pCM80, indicating their involvement in formate tolerance (Table 2; Fig. 6). The strain AM1::pCM80-1261 displayed a maximum OD600 value of 2.32, followed by AM1::pCM80-3027 (OD600 = 2.08), and AM1::pCM80-3029 (OD600 = 2.06) (Table 2). Compared to the strains with overexpression of a single gene, the superior performance of the FT3 strain at elevated formate levels suggested that the capacity to tolerate high levels of formate was conferred by the action of multiple genes.

TABLE 2.

Specific growth rates and maximum OD600 values of the M. extorquens AM1 derivative strains

| Strain | Overexpression of genes | Formate concentration (mM) | Specific growth rate (h−1) | Maximum OD600 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM1::pCM80-1261 | META1_1261 | 10 | 0.124 ± 0.010 | 2.32 ± 0.02 |

| AM1::pCM80-3027 | META1_3027 | 10 | 0.121 ± 0.010 | 2.08 ± 0.21 |

| AM1::pCM80-3029 | META1_3029 | 10 | 0.094 ± 0.004 | 2.06 ± 0.01 |

| AM1::pCM80-1418 | META1_1418 | 10 | 0.088 ± 0.006 | 1.74 ± 0.18 |

| AM1::pCM80-3028 | META1_3028 | 10 | 0.118 ± 0.016 | 1.89 ± 0.132 |

| AM1::pCM80-3028-3027 | META1_3028 and META1_3027 | 10 | 0.154 ± 0.010 | 1.89 ± 0.04 |

| AM1::pCM80-3028-3027-3029 | META1_3028, META1_3027, and META1_3029 | 10 | 0.151 ± 0.003 | 2.30 ± 0.07 |

| 15 | 0.093 ± 0.047 | 1.40 ± 0.119 | ||

| 20 | 0.070 ± 0.020 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | ||

| AM1-pmaxF-3028-3027 | META1_3028 and META1_3027 | 15 | 0.073 ± 0.009 | 1.93 ± 0.02 |

Fig 6.

Investigation of the formate tolerance through the overexpression of selected genes in M. extorquens AM1. The growth curves of the M. extorquens AM1 derivative strains harboring plasmid pCM80, which overexpressed META1_1418 (A), META1_3029 (B), META1_3027 (C), META1_3028 (D), or the operon META1_3028 and META1_3027 (E), META1_1261, or the operon META1_1261 and META1_1260 (F), and the artificial operon of META1_3027, META1_3028, and META1_3029 (H) in different formate concentrations. (G) The growth curves of the engineered strain M. extorquens AM1-PmaxF-3028-3027, in which the operon META1_3028 and META1_3027 were driven by the promoter PmaxF. The data were presented as the average of three replicates, with standard deviations indicated as error bars.

The genes META1_3027 and META1_3028 are assembled as an operon in the genome, as are the genes META1_1261 and META1_1260. Based on the results of the overexpression of individual gene, then, these two operons were further co-expressed in M. extorquens AM1 (Fig. 6E and F). The strain AM1::pCM80-1261-1260 failed to improve growth in the medium containing 10 mM formate compared to the overexpression of the individual gene META1_1261, suggesting that this operon may not be involved in formate tolerance (Fig. 6F). The specific growth rate of the strain AM1::pCM80-3028-3027 was 0.154 h−1 in the presence of 10 mM formate, which was higher than that of the strain AM1::pCM80-3028 or AM1::pCM80-3027 (Fig. 6E; Table 2). This indicated that the overexpression of this operon exhibited better performance at high concentrations of formate. Furthermore, the native promoter of the META1_3027 and META1_3028 operon was replaced with the strong promoter Pmxaf to initiate the expression. The engineered strain M. extorquens AM1-PmxaF-3028-3027 demonstrated tolerance to 15 mM formate, showing a specific growth rate value of 0.073 h−1 and a maximum OD600 value of 1.93 (Fig. 6G). The gene META1_3029 is adjacent to META1_3027 and META1_3028 (Fig. S14), and overexpression of this gene was shown to enhance tolerance to formate (Fig. 6B). Consequently, the genes META1_3027, META1_3028, and META1_3029 as an artificial operon were overexpressed in M. extorquens AM1. The strain AM1::pCM80-3028-3027-3029 was found to be able to grow on the medium containing 15 mM formate, exhibiting a specific growth rate of 0.093 h−1 and reaching a maximum OD600 value of 1.40 (Fig. 6H). Notably, in the presence of 20 mM formate, the AM1::pCM80-3028-3027-3029 exhibited a specific growth rate of 0.07 h−1 and a maximum OD600 value of 0.93 (Table 2). The results obtained from the combination of overexpressing the transporter gene META1_3027, the carbonate dehydratase gene META1_3028, and the hypothetical protein gene META1_3029 demonstrated a synergistic effect, suggesting that these three genes were likely involved in formate tolerance and utilization.

FT3 strain as a chassis with mixed methanol and formate to produce reduced chemicals of 3-HP

Previously, M. extorquens AM1 was identified as a chassis capable of producing reduced chemicals of 3-HP with methanol as the sole carbon source (33, 36, 40). In the present study, a comparison of the M. extorquens AM1 strain and the FT3 strain revealed that the latter exhibited better tolerance to 3-HP. When exposed to 1,000 mg/L 3-HP, the growth rate of the FT3 strain was 0.120 h−1, representing a 1.48-fold higher rate than M. extorquens AM1 (Fig. 7A). Based on the better tolerance to 3-HP and increased pools of reducing equivalents in the FT3 strain in the presence of formate, we speculated that the FT3 strain was a more suitable chassis for the production of 3-HP. The plasmid pCM80-Apr-mcr containing a 3-HP synthetic pathway was introduced into the FT3 strain, generating the FT3::pCM80-Apr-mcr strain. The production of 3-HP was quantified when the FT3 strain was grown on a mixture of carbon sources with varying ratios of methanol to formate. Methanol was used as the sole carbon source, serving as the control. The addition of formate at concentrations within the range of 22.5 mM to 60 mM (i.e., a reduction in the methanol to formate ratio from 85% to 70%) resulted in a continuous increase in 3-HP titer, reaching a range of 110 mg/L to 175 mg/L in flask culture (Fig. 7B). The highest titer of 175 mg/L was achieved when the FT3::pCM80-Apr-mcr strain was cultivated with 45 mM formate and 105 mM methanol. This titer was significantly elevated in comparison to the methanol, which served as the sole carbon source (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, fed-batch fermentation was conducted in a 3L biofermentor by using mixed carbon sources of methanol (0.3%, wt/vol) and formate (in the range of 8–12.7 mM). As shown in Fig. 7C, following a cultivation of 98 hours, the maximum biomass of the FT3::pCM80-Apr-mcr strain reached 38.9 g/L. After 109 hours of cultivation, the maximum titer of 3-HP was up to 2.47 g/L. This titer was approximately 14-fold higher than the highest titer obtained by shake-flask cultivation and also exceeded our previously reported production in the engineered M. extorquens AM1 strain (40). The current yield and productivity of 3-HP remain relatively low. Engineering of the one-carbon assimilation pathway will be required to further increase the one-carbon flow to the target product (40).

Fig 7.

The FT3 strain used as the host chassis to produce 3-HP. (A) Investigation of the tolerance of the FT3 strain to 3-HP. (B) Investigation of the optimal ratio of methanol to formate to produce 3-HP in the FT3::pCM80-Apr-mcr strain. (C) Analysis of 3-HP production in the FT3::pCM80-Apr-mcr strain using fed-batch fermentation with the mixed carbon sources of methanol (0.3%, wt/vol) and formate (in the range of 8 to 12.7 mM). The data in B and C were presented as the average of three replicates, with standard deviations indicated as error bars. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

Formate can be electrochemically converted from CO2 and represents a promising feedstock for biorefinery applications (3–7). Over the past decade, considerable research has been conducted to utilize formate as a carbon source for the production of high-value chemicals (15, 28–31, 54). In this study, the ALE strategy was employed to obtain an evolved strain FT3 derived from M. extorquens AM1, which demonstrated enhanced tolerance and assimilation of high concentrations of formate. Furthermore, this strain was proven to be a more effective chassis for producing 3-HP through the utilization of a combined methanol and formate as the carbon sources.

ALE is a frequently utilized methodology for the evolution of M. extorquens AM1 with new properties (43–46, 55). Typically, these evolved strains exhibit a few SNP mutations (43–46, 55). For example, an engineered strain with modified central metabolism that employs glutathione as a formaldehyde transporter, instead of the H4MPT pathway, demonstrates four SNP mutations (44). Similarly, an evolved strain with high tolerance to butanol concentration exhibits only one SNP mutation (45). However, this study revealed that the evolved strain FT3, which was identified for its tolerance to high formate concentration, displayed the hypermutant phenomenon. To our knowledge, this represents the first report of hypermutations occurring in M. extorquens AM1. Genome re-sequencing indicated that these hypermutations may be attributed to mutations in enzymes responsible for DNA repair and DNA synthesis systems. Hypermutability facilitates enhanced ALE fitness and allows for significant advancements across the fitness landscape by providing a diverse range of mutations with complex epistatic interactions (56, 57). However, the hypermutant strains could exhibit disadvantages regarding genome stability and adaptive potential. Further evaluation is required to ascertain whether the FT3 strain may continue to evolve as a result of mutations present in the DNA repair and replication systems. In the FT3 strain, the majority of mutations were classified as neutral, while a limited number were identified as beneficial alleles. Accordingly, the present study was primarily concerned with investigating the mutations involved in methanol and formate oxidation, formate transport, formate assimilation, and adjacent pathways. Based on the genomic and transcriptomic data, a number of genes were selected for further characterization through ALE-inspired gene manipulation experiments. The results indicated that the high formate tolerance observed in the FT3 strain was attributed to the action of multiple genes. The subsequent discussion is presented below.

The mutation of FocA has been demonstrated to be important for formate tolerance (20). In the present study, it was observed that the mutated FocA homologue protein META1_0287 conferred tolerance to formate in the FT3 strain by increasing the uptake of formate into the cell. Subsequently, the cellular formate can enter either the formate oxidation pathway or the assimilation pathway. Previous studies have demonstrated that enhancing either the formate assimilation pathway, such as through the overexpression of the ftfL gene, or the formate oxidation pathway, such as through the overexpression or upregulation of the fdh gene, can improve formate tolerance (21, 24, 29, 30, 58–60). This study demonstrated that the formate oxidation pathway played a more important role in conferring tolerance to formate in the FT3 strain, as evidenced by the significant enhancement of formate dehydrogenase activity (Fig. 5C), while the transcription of key genes involved in the formate assimilation pathway remained unaltered in the presence of formate (Fig. 4). The addition of formate has been demonstrated to significantly enhance the level of reduced equivalents in M. extorquens AM1 (28). Furthermore, this study revealed that the FT3 strain exhibited an increased level of NADH and NADPH when exposed to 30 mM formate (Fig. 5E). It was postulated that the enhanced oxidation of formate resulted in the generation of a greater number of NADH, which could be further converted to NADPH by the PntAB enzyme to form NADPH. In synthetic formatotrophic bacteria that harbor the reductive glycine pathway, it has been demonstrated that enhancing the conversion of NADH to NADPH by PntAB is an important factor for growth on formate (24). It would be beneficial to investigate whether the mutation of PntAB in the FT3 strain plays a similar role in formate tolerance and assimilation.

The enhanced formate dehydrogenase activities resulted in a faster conversion of formate to CO2, a portion of which can be mobilized by the two carbonate dehydratases, META1_3028 and META1_1418, to form bicarbonate and a proton that can be used as an intermediate for regulating cellular pH. The direction of formate transportation by FocA is regulated by intracellular pH (52). It was therefore postulated that the cellular pH affected by these two carbonate dehydratases may be related to the transportation of formate directed by the mutated FocA homolog META1_0287*. This may explain why the carbonate dehydratases META1_3028 and META1_1418 were observed to exhibit formate tolerance (Fig. 6A and D). On the other hand, the bicarbonate converted from CO2 within the cell can be catalyzed by Ppc or PccAB to produce corresponding metabolites, oxaloacetate or methylmalonyl-CoA. Indeed, enhanced biomass was observed when the FT3 strain was cultivated with 30 mM formate in flasks sealed with a rubber plug (Fig. 5D), suggesting that blocking CO2 emission can improve biomass accumulation. The FT3 strain displayed an improved growth when cultivated with 120 mM formate as the sole carbon source, although the maximum OD600 value remained low (Fig. 1D). It can therefore be posited that enhancing the concentration of CO2 and enhancing the CO2 fixation may prove an effective way to improve the biomass accumulation in the FT3 strain cultivated with formate as the sole carbon source. It has previously been demonstrated that the synthetic formatotrophs are capable of achieving enhanced growth when formate and a high concentration of CO2 or bicarbonate are utilized (22, 24). This study presents an additional strategy to modify the native formatotrophs to promote growth in high concentrations of formate.

It has been demonstrated that alterations in the composition of the cell membrane are crucial for improving resistance to various abiotic stresses (61). Hopanoids and C30 carotenoids are integral components of the cell membrane in M. extorquens AM1 (62). Notably, hopanoids play a pivotal role in maintaining the stability and permeability of the cell membrane (62). Strains deficient in hopanoids exhibit increased membrane permeability, resulting in poor growth (63). Recent research has also demonstrated that reduced membrane permeability and altered membrane composition are important for formaldehyde-acclimated M. extorquens strains (64). In this study, exposure of the FT3 strain to formate increased the quantity of C30 carotenoid pigments. The transcriptomic data indicated that the transcriptional levels of META1_1817, which is involved in the synthesis of the precursor squalene, as well as META1_3665, META1_3670, META1_3663, and META1_3664, which are involved in the post-modification pathway of carotenoid pigment synthesis (62, 65), showed an increase in the presence of 30 mM formate (Fig. S15; Data set S2). This finding corresponds with the enhanced C30 terpenoid synthesis (Fig. S3). In M. extorquens AM1, hopanoids share the common precursor squalene with the C30 carotenoid pigments. Notably, the transcription of the squalene-hopene cyclase gene shc (META1_1818), a critical enzyme responsible for hopanoid synthesis, was approximately three times higher in the FT3 strain than in the M. extorquens AM1 ΔcelAB strain cultivated solely with methanol (Fig. S15; Data set S2). Given the significantly increased transcription of shc in the FT3 strain, it is reasonable to propose that hopanoid synthesis has also increased in the FT3 strain, potentially influencing the permeability of the cell membrane to adapt to environmental conditions, which may be related to the enhanced formate tolerance.

In Cupriavidus necator H16, the deletion of the transcriptional regulator PhcA has been shown to result in reduced expression of several operons, thereby enhancing growth on formate (19). Based on this observation, we hypothesized that alterations in the expression of certain operons in the FT3 strain would improve the formate tolerance. It is well established that sigma factors are involved in genome-wide regulatory processes. In our research, we found a significant increase in the transcription level of the sigma factor META1_1261 in the FT3 strain, indicating its potential role as a regulator of key genes associated with formate tolerance. Indeed, overexpression of the META1_1261 gene was found to enhance formate tolerance (Fig. 6F). META1_1261 and the anti-sigma factor META1_1260 were identified as components of an operon. However, overexpression of this operon resulted in poor growth in the medium containing 10 mM formate compared to the overexpression of individual gene META1_1261 (Fig. 6F). This implies that the anti-sigma factor META1_1260 within the operon impairs the function of META1_1261. These results suggest that FT3 may have a complex regulatory network involved in formate tolerance. Transporters have been shown to relate to formate tolerance; for example, an A269T SNP mutation in the bicarbonate transporter SO_3578 enables it to transport formate, conferring Shewanella oneidensis with tolerance to 100 mM formate (66). In this study, we observed that overexpression of the sulfate transporter META1_3027 can also enhance tolerance to formate (Fig. 6C), although whether META1_3027 is involved in formate transportation requires further investigation. In addition, upon exposure to formate, certain genes with unknown functions, such as META1_3029, exhibited high levels of transcription and have been confirmed to enhance formate tolerance, which warrants further investigation in the future.

Conclusion

In this study, an evolved FT3 strain derived from M. extorquens AM1, exhibiting a high tolerance to formate, was obtained through the application of the ALE strategy. Further feeding experiments with 13C-labeled one-carbon sources demonstrated that the FT3 strain was capable of effectively utilizing methanol and formate. In contrast to previously reported evolved strains of M. extorquens AM1, the FT3 strain exhibited hypermutations. Furthermore, a combination of DNA re-sequencing, transcriptome analysis, and ALE-inspired gene manipulation was employed to investigate the potential mechanism of formate tolerance. The elevated tolerance to high concentrations of formate was attributed to alterations in metabolic pathways, including those involved in the transport of formate, methanol oxidation, formate oxidation, and assimilation pathways. The FT3 strain, which exhibited a significantly increased synthesis of reducing equivalents in the presence of formate and enhanced 3-HP tolerance, was deemed an appropriate chassis for the production of reduced chemicals of 3-HP. A 3-HP titer of 2.47 g/L was attained through fed-batch fermentation by utilizing the combined carbon sources of methanol and formate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the instrumental analysis center of Qingdao Agricultural University for the data analyses.

This study was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFC2103500) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22078169 and 22478217).

X.M., Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing | Y.Z., Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft | L.Z., Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft | C.Z., Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft | Z.L., Formal analysis | Z.M., Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis | K.B., Formal analysis | S.Y., Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision, Project administration, Writing—review and editing.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Song Yang, Email: SongYang@qau.edu.cn, yangsong1209@163.com.

Nicole R. Buan, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA

DATA AVAILABILITY

The whole-genome re-sequencing data and transcriptome data are deposited in NCBI. The accession numbers for the genome sequences of Methylorubrum extorquens FT3 deposited in NCBI are CP195989 and CP195990. The BioProject accession number for the RNASeq data is PRJNA1285123. The sequences of the plasmids generated in this study are listed in the supplemental material.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.02560-24.

SNP and InDel mutations in FT3.

Top 20 significantly up-regulated genes in M. extorquens FT3 in the presence of 30 mM formate.

Table S1, Fig. S1 to S15, and sequences of the plasmids generated in this study.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Escobar JC, Lora ES, Venturini OJ, Yáñez EE, Castillo EF, Almazan O. 2009. Biofuels: environment, technology and food security. Renew Sust Eenerg Rev 13:1275–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2008.08.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aggarwal N, Pham HL, Ranjan B, Saini M, Liang Y, Hossain GS, Ling H, Foo JL, Chang MW. 2024. Microbial engineering strategies to utilize waste feedstock for sustainable bioproduction. Nat Rev Bioeng 2:155–174. doi: 10.1038/s44222-023-00129-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cotton CA, Claassens NJ, Benito-Vaquerizo S, Bar-Even A. 2020. Renewable methanol and formate as microbial feedstocks. Curr Opin Biotechnol 62:168–180. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shi J, Jiang Y, Jiang Z, Wang X, Wang X, Zhang S, Han P, Yang C. 2015. Enzymatic conversion of carbon dioxide. Chem Soc Rev 44:5981–6000. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00182j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schuler E, Morana M, Ermolich PA, Lüschen K, Greer AJ, Taylor SFR, Hardacre C, Shiju NR, Gruter GM. 2022. Formate as a key intermediate in CO2 utilization. Green Chem 24:8227–8258. doi: 10.1039/D2GC02220F [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu MF, Zhang C, Wang J, Han X, Hu W, Deng Y. 2024. Recent research progresses of Sn/Bi/In-based electrocatalysts for electroreduction CO2 to formate. Chemistry 30:e202303711. doi: 10.1002/chem.202303711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yishai O, Lindner SN, Gonzalez de la Cruz J, Tenenboim H, Bar-Even A. 2016. The formate bio-economy. Curr Opin Chem Biol 35:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schwartz E, Henne A, Cramm R, Eitinger T, Friedrich B, Gottschalk G. 2003. Complete nucleotide sequence of pHG1: a Ralstonia eutropha H16 megaplasmid encoding key enzymes of H2-based ithoautotrophy and anaerobiosis. J Mol Biol 332:369–383. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00894-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chistoserdova L. 2011. Modularity of methylotrophy, revisited. Environ Microbiol 13:2603–2622. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02464.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bar-Even A. 2016. Formate assimilation: the metabolic architecture of natural and synthetic pathways. Biochemistry 55:3851–3863. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bar-Even A, Noor E, Flamholz A, Milo R. 2013. Design and analysis of metabolic pathways supporting formatotrophic growth for electricity-dependent cultivation of microbes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1827:1039–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ragsdale SW, Pierce E. 2008. Acetogenesis and the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway of CO(2) fixation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1784:1873–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Skovran E, Crowther GJ, Guo X, Yang S, Lidstrom ME. 2010. A systems biology approach uncovers cellular strategies used by Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 during the switch from multi- to single-carbon growth. PLoS One 5:e14091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Claassens NJ. 2021. Reductive glycine pathway: a versatile route for one-carbon biotech. Trends Biotechnol 39:327–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2021.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tian J, Deng W, Zhang Z, Xu J, Yang G, Zhao G, Yang S, Jiang W, Gu Y. 2023. Discovery and remodeling of Vibrio natriegens as a microbial platform for efficient formic acid biorefinery. Nat Commun 14:7758. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43631-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang S, Zhang Y, Dong H, Mao S, Zhu Y, Wang R, Luan G, Li Y. 2011. Formic acid triggers the “Acid Crash” of acetone-butanol-ethanol fermentation by Clostridium acetobutylicum. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:1674–1680. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01835-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhuang WQ, Yi S, Bill M, Brisson VL, Feng X, Men Y, Conrad ME, Tang YJ, Alvarez-Cohen L. 2014. Incomplete Wood-Ljungdahl pathway facilitates one-carbon metabolism in organohalide-respiring Dehalococcoides mccartyi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:6419–6424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321542111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sánchez-Andrea I, Guedes IA, Hornung B, Boeren S, Lawson CE, Sousa DZ, Bar-Even A, Claassens NJ, Stams AJM. 2020. The reductive glycine pathway allows autotrophic growth of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Nat Commun 11:5090. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18906-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Calvey CH, Sànchez I Nogué V, White AM, Kneucker CM, Woodworth SP, Alt HM, Eckert CA, Johnson CW. 2023. Improving growth of Cupriavidus necator H16 on formate using adaptive laboratory evolution-informed engineering. Metab Eng 75:78–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2022.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jung HC, Lee SH, Lee SM, An YJ, Lee JH, Lee HS, Kang SG. 2017. Adaptive evolution of a hyperthermophilic archaeon pinpoints a formate transporter as a critical factor for the growth enhancement on formate. Sci Rep 7:6124. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05424-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim SJ, Yoon J, Im DK, Kim YH, Oh MK. 2019. Adaptively evolved Escherichia coli for improved ability of formate utilization as a carbon source in sugar-free conditions. Biotechnol Biofuels 12:207. doi: 10.1186/s13068-019-1547-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bang J, Hwang CH, Ahn JH, Lee JA, Lee SY. 2020. Escherichia coli is engineered to grow on CO2 and formic acid. Nat Microbiol 5:1459–1463. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-00793-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guo Y, Zhang R, Wang J, Qin R, Feng J, Chen K, Wang X. 2024. Engineering yeasts to co-utilize methanol or formate coupled with CO2 fixation. Metab Eng 84:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2024.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim S, Lindner SN, Aslan S, Yishai O, Wenk S, Schann K, Bar-Even A. 2020. Growth of E. coli on formate and methanol via the reductive glycine pathway. Nat Chem Biol 16:538–545. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0473-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Turlin J, Dronsella B, De Maria A, Lindner SN, Nikel PI. 2022. Integrated rational and evolutionary engineering of genome-reduced Pseudomonas putida strains promotes synthetic formate assimilation. Metab Eng 74:191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2022.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]