Abstract

Background

Biliary tract cancer is a rare tumor entity mostly diagnosed at advanced stages with poor prognosis. Since publication of the TOPAZ-1 trial, durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin has become the standard palliative first-line treatment. However, real-world evidence is inconclusive and no systematic review or meta-analysis has yet evaluated the current available literature on this topic.

This meta-analysis, therefore, aimed to assess the effectiveness of durvalumab plus gemcitabine/cisplatin as first-line treatment compared to the previous standard and evaluate the existing evidence of this treatment in real-world cohorts.

Methods

Trials investigating durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin as palliative first-line treatment in advanced biliary tract cancer and published in PubMed/Medline databases between January 2020 and December 2024 were included. Studies on second-line treatment or studies investigating other than the standard chemotherapy backbones were excluded. Selection of the trials and quality assessment was conducted independently by two reviewers. Trials with a two-arm design reporting effect measures were included in the meta-analysis.

Results

After screening 190 studies, 10 trials encompassing 2877 patients were included. Evidence was heterogeneous, but results of the meta-analysis demonstrated a statistically significant difference in overall survival and progression-free survival, in favor of patients treated with durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis confirm durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin as the best currently available treatment option in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Furthermore, multiple real-world cohorts reported similar results even in patients with higher risk factors. However, trials are heterogeneous, and further evidence from real-world cohorts is needed to enhance data quality.

Keywords: immunotherapy, biliary tract cancer, systematic review, meta-analysis, durvalumab

Implications for Practice.

Compared to gemcitabine and cisplatin alone, a palliative first-line treatment with durvalumab + gemcitabine and cisplatin prolongs mOS and mPFS.

In line with previous trials from different tumor entities, a better ECOG-PS and younger age were the most frequent factors associated with better mOS.

The results of this meta-analysis of the randomized controlled phase III trial TOPAZ-1 and 3 real-world populations further supports the use of durvalumab + gemcitabine and cisplatin as standard first-line treatment in patients with advanced BTC.

Introduction

Biliary tract cancers (BTC) are rare malignant tumors arising from various parts of the biliary system.1,2 BTCs include intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma as well as carcinomas of the gallbladder/cystic duct and ampulla of Vater cancer.1 However, ampullary cancers can be subdivided into multiple subtypes (eg, intestinal, pancreatobiliary, mixed), which makes assignment to a distinct tumor entity difficult and leads to disagreement amongst researchers and clinicians.3–5

Overall, BTCs account for less than 1% of all human-derived malignant tumors.2 However, globally increasing incidence has been shown in recent years.2,6 The majority of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, lacking curative treatment options.7 Furthermore, the relapse rate in patients with localized BTCs undergoing potentially curative resection is quite high.7 Thus, prognosis of BTCs is currently poor with estimated 5-year overall survival rates of 7–20%.1

Within the past decades, several trials evaluated different treatment options for advanced BTC, yielding mostly disappointing results.7 However, in 2010, the ABC-02 trial established first-line therapy with gemcitabine plus cisplatin as a new standard of care in advanced BTCs.8 Combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy has been shown to improve palliative treatment outcomes across various cancer entities in recent years.9–11 This concept was evaluated for advanced BTCs within the TOPAZ-1 trial (durvalumab + cisplatin + gemcitabine vs. cisplatin + gemcitabine) and significantly improved the median overall survival (mOS) and median progression-free survival (mPFS) compared to chemotherapy alone.12

Since the TOPAZ-1 protocol is considered standard of care in first-line treatment of advanced BTCs, several trials have published data using this regimen in real-world cohorts.13–16 However, data have not been consistent throughout these publications. To the best of our knowledge, no systematic review or meta-analysis that addresses the current literature on first-line durvalumab combined with chemotherapy in advanced BTC is presently available.

This systematic review and meta-analysis therefore aims to evaluate existing evidence on the outcome of durvalumab plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment in advanced BTC, with the goal of clarifying the benefit of this regimen compared to chemotherapy alone.

Materials and methods

Search methods and study selection

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted according to PRISMA guidelines.17 The literature search was conducted in PubMed/Medline databases on December 21, 2024, utilizing the following search terms: (“Biliary Tract Neoplasms” [Mesh]) AND (“Antibodies, Monoclonal” [Mesh]) OR (“Antineoplastic Agents, Immunological” [Pharmacological Action]) OR Imfinzi OR Durvalumab. Randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and observational studies published between January 2020 and December 2024 were considered eligible for inclusion. Systematic reviews, editorials, letters, preprints, and short communications were excluded. The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used:

Inclusion criteria:

First-line treatment of patients with biliary tract cancer using durvalumab plus chemotherapy

Assessment of overall response rate (ORR), overall survival, and progression-free survival

Exclusion criteria:

Cancers other than biliary tract cancer

Treatment in second line and subsequent lines

Literature screening

Studies were organized using the Rayyan platform for systematic reviews.18 There were no duplicates. Titles and abstracts of the studies were independently screened by PR and MB. The only conflict during the selection process was resolved through discussion with a third researcher (TW). Afterward, full-text screening and data extraction were also conducted independently by both reviewers.

Data synthesis

Data collection was performed independently by PR and MB, including year of publication, journal, authorship, trial design, treatment regimens, and results. Potential sources of bias were identified. In accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, critical appraisal on risk of bias was conducted independently by PR and MB, using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklists for randomized controlled trials and cohort trials.19 Inconsistencies between the assessments of the two reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third researcher (TW).

Two-arm studies reporting hazard ratios (HRs) of OS/PFS or odds ratios (OR) of ORRs were included in the systematic review and the meta-analysis. Single-arm trials reporting ORRs or data for OS, PFS were included in the systematic review only. These trials are presented stratified by study design.

Statistics

All mathematical transformations were calculated according to Cochrane’s Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.20 Standard errors (SEs) for hazard ratios were calculated using the following formula:

We estimated the pooled hazard ratios of mOS and mPFS and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using random-effect logistic regression as well as fixed-effect logistic regression models. Data are presented in a forest plot. We used the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method to estimate the heterogeneity variance within the random-effects model.21 Due to the small number of included trials, the confidence interval for the summary effect of the random-effects model was estimated using the Knapp and Hartung method.22,23

The between-study heterogeneity across the included trials was assessed by Chi-square test using Cochrane’s Q. Inconsistency between studies was measured using Higgins’ and Thompson’s I2 with its 95% CI.24,25 An I2 value between 25% and 50% was considered to indicate low heterogeneity, between 50% and 75% moderate heterogeneity, and I2>75% high heterogeneity.25

A funnel plot was generated to identify potential publication bias, and asymmetry in the studies was checked using Egger’s test.26

Study quality score is based on CASP checklists (Yes = 1 point, No = 0 points, Can’t Tell = 0 points) and was calculated as follows:

All statistical analyses were performed using JASP, Version 0.19.2 (© University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands, available from https://jasp-stats.org/download/, accessed 21.12.2024).

Graphs were either created using JASP or GraphPad Prism Version 9 for Windows (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, available from www.graphpad.com).

P-values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Role of the funding source

There was no funding source for this study.

Results

A total of 190 studies from PubMed/Medline databases were screened, of which 12 were retrieved for full-text screening. The inclusion criteria were met by 9 trials. The exact process of study identification and selection is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow chart for study identification and selection.

We identified 1 randomized controlled trial comparing durvalumab plus chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy alone. Additionally, we included an updated overall survival analysis of the same study, with a longer follow-up period. Further, 3 two-arm retrospective cohort studies were included, which evaluated chemotherapy with or without durvalumab in real-world cohorts. The latter 3 trials were included in the meta-analysis for PFS together with the initial RCT. Meta-analysis for OS was performed using the 3 two-arm retrospective cohort studies and the updated survival data from the RCT.

Five additional single-arm studies analyzed durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line treatment of advanced BTC. Of these, 3 were conducted retrospectively and 2 prospectively. Due to the single-arm study design, these trials were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Altogether, the included studies comprised 2877 patients. As the included studies comprised both an RCT and a separate update on the overall survival of the patients from the original RCT, only patients pertaining to the original study were included in the overall patient count.

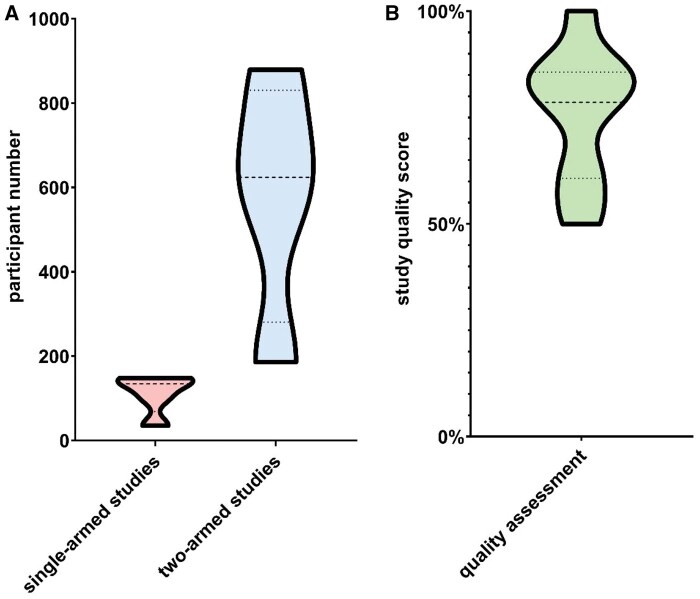

Risk of bias was assessed using CASP quality assessment scores. The results were divided into thirds to distinguish between low, moderate, and high-quality studies. 3 studies were classified as having moderate quality scores, and 7 as having high quality scores. None of the included trials achieved low quality scores. The relationship between study quality score and study size is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Study quality score versus patient count, depicted with non-linear regression line and corresponding 95% confidence interval. Study quality score is based on Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists for randomized controlled trials and cohort trials.

Due to the above-mentioned heterogeneity, included trials were grouped by two-arm vs. single-arm design. All included studies are listed in Table 1. Figure 3 illustrates the total number of participants per study in the two-arm group and the single-arm group, respectively, as well as the study quality score in relation to study size.

Table 1.

Included studies regarding treatment of advanced BTC with durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin as palliative first-line therapy.

| First author, country | Year published | n (durvalumab) | n (control) | Study type | Treatment (durvalumab) | Treatment (control) | Main result | Potential sources of bias | Study quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-arm trials | |||||||||

| Oh, world wide12 | 2022 | 341 | 344 | Randomized controlled trial | Durvalumab + gemcitabine and cisplatin | Gemcitabine + cisplatin | Significantly longer mPFS and mOS in the durvalumab cohort | Potential selection bias, due to exclusion of patients with ECOG-PS >2 | High |

| Oh, world wide29 | 2024 | 341 | 344 | Randomized controlled trial, updated survival analysis with longer follow-up | Durvalumab + gemcitabine and cisplatin | Gemcitabine + cisplatin | Significantly longer mOS in the durvalumab cohort was confirmed after longer follow-up | Potential selection bias, due to exclusion of patients with ECOG-PS >2 | High |

| Rimini, world wide14 | 2024 | 666 | 213 | Multi-center retrospective cohort trial | Durvalumab + gemcitabine and cisplatin | Gemcitabine + cisplatin | Significantly longer mPFS and mOS in the durvalumab cohort | Historic control group, no matching performed between the two cohorts | High |

| Rimini, Italy27 | 2024 | 350 | 213 | Multi-center retrospective cohort trial | Durvalumab + gemcitabine and cisplatin | Gemcitabine + cisplatin | mPFS and mOS were significantly longer in patients receiving durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin | Historic control group, no matching between the two cohorts was performed, higher proportion of patients with age >= 70 years in the durvalumab cohort (40.6% vs. 22.1%) | High |

| Lu, China28 | 2024 | 93 | 93 | Single-center retrospective cohort trial | Durvalumab + gemcitabine-based chemotherapy | Gemcitabine-based chemotherapy | mPFS significantly longer in patients receiving durvalumab, mOS numerically longer but did not reach threshold for statistical significance | Potential selection bias, only patients from China enrolled, patients with various gemcitabine-based chemotherapy backbones were included, no matching of patients between cohorts performed | Moderate |

| Single-arm trials | |||||||||

| Rimini, Italy13 | 2023 | 145 | - | Multi-center prospective cohort study | Durvalumab + gemcitabine and cisplatin | - |

|

Comparably short follow-up, a median of only 6 cycles were administered, and time intervals between restaging CT scans were not specified | High |

| Olkus, Germany30 | 2024 | 35 | - | Single-center prospective cohort study | Durvalumab and gemcitabine plus cisplatin | - |

|

Short follow-up, small cohort, no confidence intervals of ORR, mPFS, and mOS were reported, 4 patients received prior palliative systemic treatment | Moderate |

| Reimann, Austria/Germany15 | 2024 | 102 | - | Multi-center retrospective cohort study | Durvalumab plus platin and gemcitabine | - |

|

5.9% of patients received carboplatin or oxaliplatin based chemotherapy instead of cisplatin | High |

| Mitzlaff, Germany31 | 2024 | 165 | - | Multi-center retrospective cohort study | Durvalumab + gemcitabine and cisplatin | - |

|

Only 134 patients received durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin as first-line treatment, durvalumab added after start; chemotherapy in most patients | High |

| Muddu, India16 | 2024 | 148 | - | Multi-center retrospective trial | Durvalumab + chemotherapy | - |

|

Short follow-up, only 82.4% of patients received gemcitabine + cisplatin as chemotherapy backbone | Moderate |

Study quality scores were based on appropriate Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklists. Results were classified into three levels: low (0-33%), moderate (33-66%), and high (66-100%).

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; CT, computed tomography; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; mOS, median overall survival; mPFS, median progression-free survival; n, number of patients; ORR, overall response rate.

Figure 3.

(A) Violin plots depicting the number of patients per single-arm and two-arm study. (B) Violin plot of study quality score, assessing quality of included trials using Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists for randomized controlled trials and cohort trials, as appropriate.

Two-arm trials

Of the four two-arm trials included in this systematic review, three reported a statistically significant advantage in overall survival if durvalumab to chemotherapy was added in first-line treatment of advanced biliary tract cancer.12,14,27,28

A randomized controlled trial by Oh et al. reported a higher ORR in patients receiving durvalumab plus gemcitabine/cisplatin compared to gemcitabine/cisplatin chemotherapy alone (26.7% vs. 18.7%, odds ratio 1.6; 95% CI 1.11–2.31). Further, mOS (12.8 months vs. 11.5 months) and mPFS (7.2 months vs. 5.7 months) were statistically significantly prolonged in the durvalumab cohort (HR 0.8; P = .021 and HR 0.75; P = .001, respectively).12 These results were confirmed in an updated overall survival analysis with longer follow-up of the original patient cohort (mOS 12.9 months vs. 11.3 months, HR 0.76; 95% CI 0.64–0.91).29

Accordingly, two large retrospective cohort studies by Rimini et al. (879 and 563 patients, respectively) reported significantly longer mOS and mPFS in patients receiving durvalumab plus chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone.14,27 Of note, both trials included a control cohort of patients treated with gemcitabine/cisplatin prior to approval of durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

In contrast, a smaller Chinese study including 186 patients, who received gemcitabine-based chemotherapy with or without durvalumab, did not report a significant difference in terms of median overall survival.28 However, this retrospective cohort study comprised patients with different chemotherapy backbones, including gemcitabine mono, doublet, and triplet regimens. In addition, factors associated with participant ethnicity may have affected the study’s findings.

Single-arm trials

Prospective trials

Overall, 5 single-arm studies evaluated the impact of adding durvalumab to chemotherapy in patients with advanced BTC. Among these, a prospective cohort study by Rimini et al. assessed a cohort of 145 patients treated in 17 Italian centers between February 2022 and November 2022 with a median follow-up of 8.5 months (95% CI 7.9–13.6). This study observed an ORR of 34.5% with a mPFS of 8.9 months (95% CI 7.4–11.7) and an mOS of 12.9 months (95% CI 10.9–12.9).13

Another prospective cohort study was performed in Germany and included patients with advanced BTC who were treated according to the TOPAZ-1 trial between April 2022 and June 2023. This small cohort included 35 patients with a median follow-up of 6.2 months. The mOS was 10.3 months, mPFS was 5.3 months, and ORR was 14.7%. However, no 95% confidence intervals were reported. Furthermore, follow-up was relatively short, and 4 patients had already received a prior palliative systemic treatment. Overall, only 18 out of 35 patients matched the inclusion criteria of the TOPAZ-1 trial, which may account for the differences between this study and the TOPAZ-1 trial.30

Retrospective trials

Three retrospective trials were considered eligible for inclusion in this systematic review. We previously published a multicenter cohort trial which enrolled 102 patients from Austria and Germany between April 2022 and January 2024. The median follow-up period was 9.34 months (95% CI 6.58–11.18). In this cohort, ORR was 35.11%. The patients reached a mPFS of 6.51 months (95% CI 4.77–7.27) and an mOS of 13.61 months (95% CI 11.28–21.63). Most of the patients received palliative first-line treatment with durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin, according to the TOPAZ-1 trial. However, 4.9% of the included probands were treated with carboplatin instead of cisplatin and 1% received oxaliplatin.15

Another multicenter cohort trial was conducted by Mitzlaff et al. and comprised 165 patients treated between 2021 and 2024. Of these, only 134 patients received durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin as first line treatment. Therefore, only these patients are included in this systematic review. Median follow-up of these 134 patients was 9 months (95% CI 7.6–10.4). The ORR was 26% with a median PFS of 8 months (95% CI 6.8–9.2) and an mOS of 14 months (95% CI 11.1–16.9). However, in the majority of patients durvalumab was added after start of chemotherapy, following approval of the TOPAZ-1 protocol by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Thus, only a small fraction of the included patients received the full 8 cycles of chemoimmunotherapy, as specified by the TOPAZ-1 protocol.31

The third retrospective single-arm trial included in this systematic review was conducted in India by Muddu et al. and included a total of 148 patients who were diagnosed between July 2020 and July 2023 and received durvalumab plus chemotherapy as palliative first-line therapy. The median follow-up was 6.8 months (95% CI 5.9–7.8), the mPFS reached 8.2 months (95% CI 7.1–9.4), and the mOS was 12 months (95% CI 7.8–16.3). The most common chemotherapy backbone was gemcitabine plus cisplatin (122 patients, 82.4%), whilst a minority of patients received carboplatin or oxaliplatin instead of cisplatin (6 patients, 4.1%). Further, 3 patients (2%) were treated with fluorouracil-based chemotherapy, 9 patients (6.1%) with irinotecan and 8 patients (5.4%) with etoposide and carboplatin as chemotherapy backbone.16 Hence, comparability between this study and trials using TOPAZ-1 protocol may be limited.

Meta-analysis

A total of 4 two-arm trials met the inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis. The fixed- and random-effects model for pooled HR of the mOS was calculated using the data of the updated survival analysis of the TOPAZ-1 trial.29 On the other hand, the pooled HRs of the mPFS were estimated based on data of the original publication of the TOPAZ-1 trial.12

The random-effects model estimated a pooled HR of 0.70 (95% CI 0.52–0.88; P = .001) for mOS between patients receiving durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin versus gemcitabine/cisplatin alone, demonstrating a statistically significant difference of mOS between the two cohorts, in favor of the durvalumab group. I2 was 0.00025% and Chi-square test of Cochrane’s Q (2.88) reported a P value of .411. Therefore, no substantial heterogeneity was observed within this analysis. However, these results have to be interpretated carefully, considering the limitations of these statistical tests. No publication bias was found using a funnel plot with Egger’s test (P = .734). The detailed forest plot is depicted in Figure 4 and the funnel plot in Figure 5A.

Figure 4.

Pooled overall survival analysis comparing durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin and gemcitabine/cisplatin alone, using a random-effects model. Abbreviations: chemo, gemcitabine/cisplatin; HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 5.

(A) Funnel plot of the hazard ratio of median overall survival, including Egger’s test for funnel plot asymmetry. (B) Funnel plot of the hazard ratio of median progression-free survival along with the corresponding Egger’s test. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Further, a fixed-effects model reported the same results as above (pooled HR of mOS 0.70, 95% CI 0.52–0.88; P = .001). The forest plot is depicted in Supplementary Figure S1 (see online supplementary material for a color version of this figure).

Regarding the pooled analysis of mPFS, there was also a statistically significant difference in favor of durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin using the random-effects model (pooled HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.49–0.79; P < .001). Higgins’ I2 was 6.96% and Chi-square test of Cochrane’s Q (2.55) reported a P value of .467. Thus, no substantial heterogeneity was observed using these tests. The corresponding forest plot is shown in Figure 6. The funnel plot for this analysis is depicted in Figure 5B and did not show graphical asymmetry, which was confirmed by the Egger’s test (P = .764).

Figure 6.

Pooled progression-free survival analysis using a random-effects model. Abbreviations: chemo, gemcitabine/cisplatin; HR, hazard ratio.

The additional results of the fixed-effects model were concordant with those of the random-effects model. The fixed-effects model forest plot is shown in Supplementary Figure S2 (see online supplementary material for a color version of this figure).

The publication by Rimini et al. included additional data of a propensity score matching analysis comprising 213 patients in each study arm.27 These data were included in a separate pooled mOS and mPFS analysis. Results also showed a benefit in terms of mOS and mPFS in the patients receiving combined chemoimmunotherapy. Detailed forest plots for these analyses are depicted in Supplementary Figures S3 and S4 (see online supplementary material for a color version of this figure).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis provide further evidence on the use of durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin as palliative first-line treatment in advanced BTC, reporting a statistically significant benefit in terms of mOS and mPFS compared to chemotherapy alone. Prolongation of mOS and mPFS as well as higher ORR first described by the approval study (TOPAZ-1), are further supported by 2 retrospective real-world cohort trials.12,14,27,29 While another retrospective multi-center cohort trial did not demonstrate an mOS benefit, the combined data within our meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant and clinically meaningful advantage of the combined chemo-immunotherapy.28

Our statistical and graphical investigations did not identify relevant heterogeneity between the included trials. However, the meta-analysis only comprised 4 trials, and the standard limitations of these statistical methods should be considered in the interpretation of the results.

Furthermore, the 2 trials by Rimini et al. included a control cohort, comprising patients treated with gemcitabine and cisplatin in palliative first-line setting prior to approval of durvalumab by the European Medicines Agency. Additionally, the same control cohort was used in both studies.14,27 Hence, a relatively small number of patients treated with chemotherapy alone was included in this meta-analysis.

However, at the time of the literature search, no additional two-arm trials in this setting were identified. Thus, further real-world evidence is needed to enhance data quality.

In addition to the trials included in this meta-analysis, our systematic review comprised 5 single-arm studies, which provide additional evidence on the use of durvalumab plus gemcitabine/cisplatin as standard first-line treatment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to assess efficacy of durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin as first-line treatment in patients with advanced BTC.

Regarding median overall survival, the real-world single-arm trials reported results between 10.3 months and 14 months.13,15,16,30,31 This is in line with the updated data from the TOPAZ-1 trial (mOS 12.9 months) and further supports combined chemo-immunotherapy as standard first-line treatment in these patients.29 However, results of these single-arm trials need to be interpreted carefully, given that they comprise only between 35 and 148 patients.13,15,16,30,31 Furthermore, 2 trials suffered from very short follow-up intervals (6.2 and 6.8 months, respectively), which might have affected the reported outcomes.13,16

Additionally, 2 out of 5 trials included patients treated with different chemotherapy backbones.15,16 The analysis of Mitzlaff et al. also included patients with different chemotherapy regimens.31 However, this study reported ORR, mOS and mPFS results of the subgroup receiving gemcitabine/cisplatin as chemotherapy. Therefore, only the results of the latter subgroup were considered in this study.

High ECOG-PS is a known risk factor for worse outcomes in patients with advanced BTC from a large real-world analysis.32 In contrast to the approval study, 4 out of 5 real-world cohorts included patients with ECOG-PS >1.15,16,30,31 Notably, the trial by Muddu et al. comprised 24.3% of patients with ECOG-PS >1, whilst still reporting a mOS of 12 months.16 This is numerically longer than the mOS reported in the ABC-02 trial, which led to approval of gemcitabine + cisplatin as standard first-line treatment in advanced BTC in 2010.8 Thus, durvalumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin might be the best treatment option currently available, even in patients with ECOG-PS > 1.

Multiple trials in this systematic review included a multivariate analysis for mOS.14–16,27,28,31 A better ECOG-PS was the most frequent factor, associated with better mOS among these trials (3 trials).14,28,31 The second most frequent positive predictive factor for mOS was younger age (2 trials).15,16 Of note, one of the latter trials used a cutoff of 60 years in the multivariate analysis, whereas the other trial used 65 years as a cutoff.

Since the development of durvalumab, other checkpoint inhibitors have become available for the treatment of BTC. For pembrolizumab, a phase III randomized controlled trial reported statistically significant improvement in mOS (12.7 months vs. 10.9 months; HR 0.83, P = .0034) in patients receiving pembrolizumab + gemcitabine/cisplatin compared to chemotherapy alone.33 However, in contrast to durvalumab, patients receiving pembrolizumab did not show a statistically significant benefit in mPFS. Nonetheless, pembrolizumab currently constitutes an additional therapeutic option for the treatment of BTC.

Apart from pembrolizumab, multiple smaller trials investigated various further checkpoint inhibitors, including nivolumab, atezolizumab, and camrelizumab.34–36 However, to the best of our knowledge, no randomized controlled phase III trials for these drugs are currently available.

Limitations of included evidence

Several trials included in the meta-analysis used a historic control cohort, and not all of these trials performed a propensity score matching to ensure evenly distributed patient characteristics across both cohorts. Additionally, the time intervals at which treatment responses were assessed were not provided by all studies. Therefore, longer or shorter intervals might have affected the reported progression-free survival.

Further, several studies included in the systematic review did not consistently use gemcitabine/cisplatin as chemotherapy backbone in all enrolled patients, even the proportion of patients not receiving gemcitabine/cisplatin is rather small.

Strengths and limitations of the review process

We conducted a comprehensive search of the PubMed/Medline databases, in which 190 potentially relevant studies were identified. However, studies exclusive to other platforms may have been missed in this systematic review and meta-analysis. To minimize the risk of bias, study screening and selection as well as quality assessment of the included trials were independently performed by two researchers. Inconsistencies were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer to further minimize bias.

Implications

Based on the results from this meta-analysis, a palliative first-line treatment with durvalumab + gemcitabine and cisplatin prolongs mOS and mPFS compared to gemcitabine and cisplatin alone. This combined analysis of the randomized controlled phase III trial TOPAZ-1 and 3 real-world populations further supports the use of durvalumab + gemcitabine and cisplatin as standard first-line treatment in patients with advanced BTC.

Additionally, data from 5 single-arm studies included in the systematic review also reported comparable mOS and mPFS results, thus strengthening evidence for use of combined chemo-immunotherapy across multiple patient cohorts.

In line with previous trials from different tumor entities, a better ECOG-PS and younger age were the most frequent factors associated with better mOS.

However, due to the high heterogeneity in study designs, for instance regarding the use of different chemotherapy backbones, results need to be interpreted with care, especially those of the single-arm trials.

Further evidence from real-world cohorts is needed to enhance data quality of this rare disease and identify subgroups that benefit most from intensified treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None

Contributor Information

Patrick Reimann, Department of Internal Medicine II, Academic Teaching Hospital Feldkirch, Feldkirch 6800, Austria; Department of Medical Sciences,Private University of the Principality of Liechtenstein, Triesen 9495, Liechtenstein.

Eva-Maria Schneider, Department of Internal Medicine II, Academic Teaching Hospital Feldkirch, Feldkirch 6800, Austria.

Angela Djanani, Department of Internal Medicine, Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck 6020, Austria.

Sylvia Mink, Department of Medical Sciences,Private University of the Principality of Liechtenstein, Triesen 9495, Liechtenstein; Central Medical Laboratories, Feldkirch 6800, Austria.

Thomas Winder, Department of Internal Medicine II, Academic Teaching Hospital Feldkirch, Feldkirch 6800, Austria; University of Zurich, Zurich 8006, Switzerland.

Magdalena Benda, Department of Internal Medicine II, Academic Teaching Hospital Feldkirch, Feldkirch 6800, Austria; Department of Medical Sciences,Private University of the Principality of Liechtenstein, Triesen 9495, Liechtenstein.

Author contributions

Patrick Reimann (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing [True]), Eva-Maria Schneider (Writing—review & editing [True]), Angela Djanani (Writing—review & editing [True]), Sylvia Mink (Writing—review & editing [True]), Thomas Winder (Writing—review & editing [True]), and Magdalena Benda (Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing [True])

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at The Oncologist online.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Review protocol

The review protocol is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Registration

This systematic review was not registered.

References

- 1. Banales JM, Marin JJG, Lamarca A, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:557-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vogel A, Bridgewater J, Edeline J, et al. Biliary tract cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:127-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Uijterwijk BA, Lemmers DH, Ghidini M, et al. The five periampullary cancers, not just different siblings but different families: an international multicenter cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31:6157-6169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Westgaard A, Pomianowska E, Clausen OP, et al. Intestinal-type and pancreatobiliary-type adenocarcinomas: how does ampullary carcinoma differ from other periampullary malignancies? Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:430-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liang H, Zhu Y, Wu YK. Ampulla of Vater carcinoma: advancement in the relationships between histological subtypes, molecular features, and clinical outcomes. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1135324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:12-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Valle JW, Lamarca A, Goyal L, et al. New horizons for precision medicine in biliary tract cancers. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:943-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gandhi L, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2078-2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Janjigian YY, Ajani JA, Moehler M, et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy for advanced gastric, gastroesophageal junction, and esophageal adenocarcinoma: 3-year follow-up of the phase III CheckMate 649 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:2012-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paz-Ares L, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, et al. Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: 3-year overall survival update from CASPIAN. ESMO Open. 2022;7:100408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oh DY, Ruth He A, Qin S, et al. Durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022;1:EVIDoa2200015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rimini M, Fornaro L, Lonardi S, et al. Durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract cancer: an early exploratory analysis of real-world data. Liver Int. 2023;43:1803-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rimini M, Fornaro L, Rizzato MD, et al. Durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract cancer: a large real-life worldwide population. Eur J Cancer. 2024;208:114199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reimann P, Mavroeidi IA, Burghofer J, et al. Exploring the impact of durvalumab on biliary tract cancer: insights from real-world clinical data. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2024;73:251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muddu VK, Shah A, John A, et al. Gemcitabine cisplatin and durvalumab experience in advanced biliary tract cancers: a real-world, multicentric data from India. JCO Glob Oncol. 2024;10:e2400216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Checklists. Oxford: CASP UK; 2018. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.5 (Updated August 2024). Cochrane; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harville DA. Maximum likelihood approaches to variance component estimation and to related problems. J Am Stat Assoc. 1977;72:320. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Langan D, Higgins JPT, Jackson D, et al. A comparison of heterogeneity variance estimators in simulated random-effects meta-analyses. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10:83-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rimini M, Masi G, Lonardi S, et al. Durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin versus gemcitabine and cisplatin in biliary tract cancer: a real-world retrospective, multicenter study. Target Oncol. 2024;19:359-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu Y, Jin Y, Liu F, et al. Efficacy of durvalumab plus chemotherapy in advanced biliary duct cancer and biomarkers exploration. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2024;73:220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oh DY, He AR, Bouattour M, et al. Durvalumab or placebo plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in participants with advanced biliary tract cancer (TOPAZ-1): updated overall survival from a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9:694-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Olkus A, Tomczak A, Berger AK, et al. Durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer: an exploratory analysis of real-world data. Target Oncol. 2024;19:213-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mitzlaff K, Kirstein MM, Müller C, et al. Efficacy, safety and differential outcomes of immune-chemotherapy with gemcitabine, cisplatin and durvalumab in patients with biliary tract cancers: a multicenter real world cohort. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024;12:1230-1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Renteria Ramirez DE, Knofler LA, Kirkegard J, et al. Prognosis related to treatment plan in patients with biliary tract cancer: a nationwide database study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2024;93:102688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kelley RK, Ueno M, Yoo C, et al. Pembrolizumab in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin compared with gemcitabine and cisplatin alone for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer (KEYNOTE-966): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;401:1853-1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Feng K, Liu Y, Zhao Y, et al. Efficacy and biomarker analysis of nivolumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with unresectable or metastatic biliary tract cancers: results from a phase II study. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hack SP, Verret W, Mulla S, et al. IMbrave 151: a randomized phase II trial of atezolizumab combined with bevacizumab and chemotherapy in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021;13:17588359211036544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhao J, Guo H, Wu C, et al. Efficacy and safety of camrelizumab combined with chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced biliary malignancy and associations between peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets and clinical outcomes. Clin Transl Oncol. 2025;27:1658-1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.