Abstract

When the eyes view separate and incompatible images, the brain suppresses one image—removing it from visual awareness. A popular paradigm for doing this is continuous flash suppression (CFS). One eye views a static ‘target’, the other is presented with a complex dynamic stimulus which very effectively suppresses the target. Measuring the time needed for the suppressed target to break suppression as it slowly increases in contrast (bCFS) has been widely used to investigate unconscious processing and the results have generated controversy regarding the scope of visual processing without awareness. In particular, upright faces and fearful faces have been claimed to have priority access to awareness. Here, we address this controversy with a new ‘CFS tracking’ paradigm (tCFS) in which the suppressed monocular target steadily increases in contrast until breaking into awareness (as in bCFS) after which it decreases until it becomes suppressed again (reCFS), with this cycle continuing for many reversals. Unlike bCFS, tCFS provides measures of breakthrough thresholds as well as suppression thresholds, and the difference between breakthrough and suppression thresholds defines the important metric of ‘suppression depth’. The suppression depth results over two experiments are consistent in showing no face inversion effects (i.e. no priority for upright faces relative to inverted) and no effect of emotion (no priority for fearful faces relative to happy or neutral). Given this consistent non-selectivity, we conclude that CFS elicits a strong suppression in early visual cortex at a level preceding face processing.

Keywords: awareness, CFS, face priority, face inversion, early suppression, non-selective suppression

Introduction

The recent decade has seen widespread use of continuous flash suppression (CFS: Tsuchiya and Koch 2005) as a method of suppressing visual images from awareness (reviewed in: Gayet et al. 2014, Yang et al. 2014, Pournaghdali and Schwartz 2020, Lanfranco et al. 2023). The CFS paradigm is a form of interocular suppression that involves presenting a target image to one eye (usually small, static, and low in contrast) while the other eye views a masking image (usually large, high in contrast, and rapidly flickering). Presenting the stimuli simultaneously (one to each eye) causes the target image to be suppressed from awareness, typically remaining invisible for several 10s of seconds so that an observer is aware of seeing only the flickering pattern. It is this property that explains the popularity of CFS. By reliably suppressing an image from visual awareness, CFS provides a convenient way to address a very interesting question in vision science: can visual processing occur without conscious awareness? Given the appeal of this question, and the relative ease of implementing the paradigm, CFS has gained wide popularity, including with researchers working in fields well beyond its original core audience in basic visual perception (Wang et al. 2023).

The study of interocular suppression has a long history, with another paradigm known as ‘binocular rivalry’ (Alais and Blake 2005, 2015) extensively studied for many decades before CFS appeared (Breese 1909, Levelt 1965, Alais et al. 2000). In rivalry, the competing stimuli are more evenly matched, usually having the same size and contrast and will rival even when differing in only one feature dimension such as two gratings with different orientations or spatial frequencies (Blake and Fox 1974a, Fahle 1982). Being closely matched (compared to CFS, where the stimuli differ in size, contrast, flicker, and often colour), stimulus competition in rivalry is more evenly balanced and perceptual switches occur quite often (typically in the range of 1–3 seconds: Fox and Herrmann 1967, van Boxtel et al. 2008, Kang and Blake 2010) as neither image dominates the other. A central goal in rivalry studies has been to quantify ‘suppression depth’, the extent to which the unseen image is attenuated by interocular suppression (Wales and Fox 1970, Blake and Fox 1974b, Holopigian 1989). The method involves presenting a monocular contrast probe to one eye while that eye’s image is visible (to obtain a dominance threshold) and comparing it to the same probe presented when that eye’s image is suppressed from awareness (yielding a suppression threshold). The ratio of dominance-to-suppression thresholds quantifies suppression depth and reveals how far below the threshold for conscious awareness is the suppressed image. Typical dominance-to-suppression ratios are around 0.6 (i.e. a suppression depth of 40%) for rivalry between low-level stimuli such as gratings (Makous and Sanders 1978, Nguyen et al. 2001, Apthorp et al. 2009). Suppression depth is stronger for rivalry between more complex stimuli such as faces, houses, and global motions (Nguyen et al. 2003, Alais and Melcher 2007, Parker and Alais 2007).

The concept of suppression depth is very relevant to CFS. A wide variety of target stimuli have been examined in CFS studies and there are many claims that certain images can influence perception despite being suppressed from conscious awareness (Jiang et al. 2007, Yang et al. 2007, Zhou et al. 2010, Chen and Yeh 2012, Sklar et al. 2012, Stewart et al. 2012, Almeida et al. 2013, Abir et al. 2018, Yang and Yeh 2018). The usual way to show this is to use the ‘breakthrough’ CFS method (bCFS: Jiang et al. 2007, Stein et al. 2011) in which the target is ramped up from very low contrast until it eventually breaks through from suppression into awareness (Jiang et al. 2007, Yang et al. 2007, Zhou et al. 2010, Chen and Yeh 2012, Sklar et al. 2012, Stewart et al. 2012, Almeida et al. 2013, Abir et al. 2018, Yang and Yeh 2018). Relying on breakthrough time as the dependent variable, various studies have shown certain images breakthrough sooner than others, as if they have a priority access to awareness and are at least partially processed despite being removed from conscious awareness. The most widely studied examples use images of faces. A number of studies have concluded on the basis of reduced CFS breakthrough times that fearful faces are partially processed without awareness (Yang et al. 2007, Almeida et al. 2013), and that upright faces are prioritized for conscious access relative to inverted faces (Jiang et al. 2007, Zhou et al. 2010). Because of the reliance on breakthrough times, it is not known if such images exhibit a reduced depth of suppression.

Relying on breakthrough times to draw conclusions about unconscious processing in CFS is problematic because: (i) it ignores the fact that some images are simply more salient for the visual system and will tend to breakthrough sooner than others (e.g. if they are strong in low-level image properties), and (ii) it cannot measure whether one image undergoes less or more suppression than another. Measuring suppression depth solves both problems. First, regarding salience, a boost in image salience would reduce breakthrough times but would also reduce suppression thresholds because a salient image would be resistant to suppression (so, a lower shift of both values, but no change in suppression depth overall). Second, a special image claimed to have priority access to awareness (e.g. a fearful face) should undergo less suppression and remain closer to the awareness threshold.

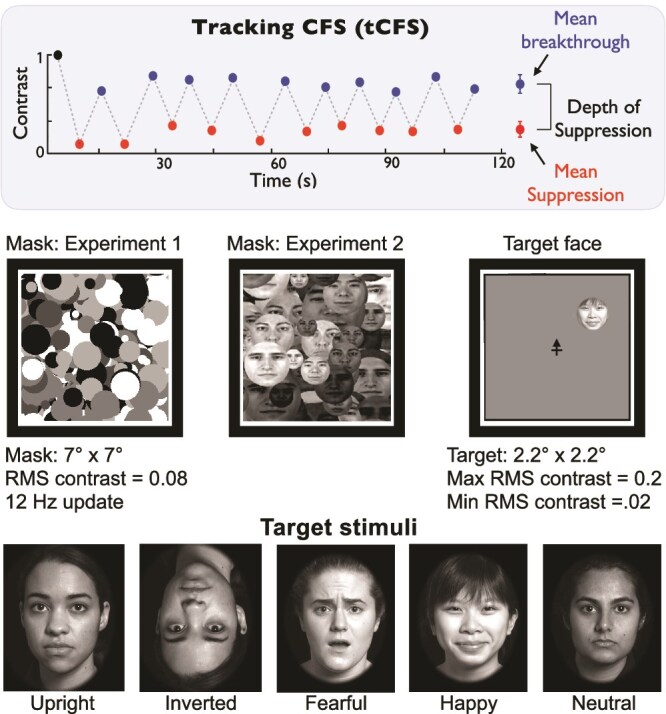

In this study, we apply a new method called ‘tracking’ CFS (tCFS: Alais et al. 2024) which measures both breakthrough and suppression thresholds (see Fig. 1). There are several advantages to using tCFS compared to the common bCFS approach based on time to breakthrough: (i) The tCFS method returns two dependent variables, breakthrough threshold and suppression threshold. From this, a third can be calculated, suppression depth, by calculating the difference between breakthrough and suppression thresholds. (ii) tCFS is efficient. Rather than starting at zero contrast and ramping up until breakthrough, the contrast level in the tCFS method stays in a narrow range around the visibility threshold, oscillating up and down to find the breakthrough and suppression thresholds. (iii) tCFS is fast. By staying in the contrast range of interest, and by entraining repeated measurements without an inter-trial interval, the method is fast. The plot at the top of Fig. 1 shows 10 estimates of breakthrough and 10 of suppression in a sequence lasting < 2 minutes. (iv) tCFS does not confound time and contrast because the target contrast changes slowly so that breakthrough is reached before reaching maximum contrast. Many bCFS studies raise the target quickly to maximum contrast where it remains until eventually breaking through. This occurs once adaptation weakens the masker and therefore bCFS breakthrough times largely reflect the timecourse of contrast adaptation. tCFS thresholds instead are measured in contrast, the key driver of early visual neurons. (v) tCFS suppression depth measurements allow easy testing of claims about certain images having special access to awareness or receiving partial processing even though out of awareness. None of these claims could be tested previously as there was no easy way to measure strength of suppression. tCFS overcomes this limitation.

Figure 1.

Top: In the tCFS paradigm, the target continually changes contrast and participants indicate when their perceptual state changes with a mouse click, which then reverses the direction of contrast change. The target starts visible at high contrast and declines until suppression is indicated, then it rises in contrast until breakthrough into awareness, and then it declines again, and so on. This provides a quick and efficient measure of bCFS threshold, but also of reCFS threshold and thus suppression depth (the difference between bCFS and reCFS thresholds). Middle: Both experiments used Mondrian masks made of achromatic circles with relatively low RMS contrast (to allow targets to breakthrough before reaching maximum contrast). In Experiment 2, the Mondrian mask was compared with a mask made of circular face images. All target contrast change was linear on a log scale. Bottom: All targets were faces expressing one of three emotions and were presented either upright or inverted.

Here we use tCFS to study suppression of faces, comparing three emotions (fearful, happy, and neutral) and two face orientations (upright vs. inverted). To preview the results, we find no effect of emotion or orientation on the depth of CFS suppression.

Experiment 1

The first experiment uses the tCFS paradigm (Alais et al. 2024) to obtain measures of both breakthrough and suppression thresholds (from here on ‘bCFS’ and ‘reCFS’, respectively) and thus quantify the depth of suppression. Quantifying suppression depth (as done in binocular rivalry: Alais 2012) is highly relevant in studies of CFS and yet a review of the literature reveals that before our introduction of the new tCFS method, only two out of hundreds of CFS papers had measured suppression depth (Tsuchiya et al. 2006, Yang and Blake 2012). This measure is critically relevant to CFS studies drawing conclusions about priority access to awareness, especially because there are doubts about the validity of relying on breakthrough times (Gayet et al. 2014, Pournaghdali and Schwartz 2020). Experiment 1 uses suppression depth as the dependent variable and compares upright and inverted face targets to test whether there is a face inversion effect and compares fearful/neutral/happy facial expression. Previous findings that inferred priority access to awareness from shorter breakthrough times imply suppression depth should be reduced for upright faces compared to inverted faces, and for fearful relative to neutral and happy faces. However, an alternative position is that suppression should be the same for all conditions on the grounds that interocular suppression occurs early in cortical processing, likely in primary visual cortex, before left- and right-eye signals merge into a single binocular stream (Blake 1989) and before image features are merged into coherent objects in mid-level vision (Conway 2018).

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 17 (14 females) undergraduate psychology students from the University of Sydney voluntarily participated in Experiment 1 in exchange for course credit. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and provided informed consent. The experiment was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol number: 2021/048).

Apparatus

A mirror stereoscope was used to partition the participant’s vision into separate left- and right-eye views and was placed ~51 cm from the screen and had a total optical path length of ~57 cm. The experiment was programmed using custom MATLAB code and the Psychtoolbox (version 3.0.13: Brainard 1997). Visual stimuli were displayed in greyscale on an Apple LED Cinema monitor with a 60 Hz refresh rate (24 inch, 1920 × 1 200 pixels resolution) running off a Mac Pro computer (2013; 3.7 GHz Quad-Core Intel Xeon E5). The participant’s responses indicating change of percept from suppressed to visible (or vice versa) as the target changed in contrast were collected via a mouse button click.

Stimuli

Two stimuli were presented dichoptically to participants via the stereoscope, with a high-contrast mask stimulus (400 × 400 pixels, 7° × 7°) presented to one eye and a small target stimulus (130 × 130 pixels, 2.2° × 2.2°) to the other (Fig. 1). The mask and target stimuli were both located inside a fusion frame which allowed participants to maintain a stable fusion of the images. A fixation cross (18 × 18 pixels; 0.3° × 0.3°) was located in the centre of the fusion contours.

The target stimuli were images of human faces selected from the Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF) database (Lundqvist et al. 1998). There were six individual identities (three males and three females) shown with three different facial expressions (fearful, happy, and neutral) and each image was presented upright and inverted to investigate the face inversion effect, resulting in a total of 36 (6 × 3 × 2) target stimuli. The reason for using six face identities was to add variation so that the target was not predictable and data from the different identities were pooled for data analysis (the data showed no dependence on identity). The design was, therefore, a factorial combination of 3 emotions * 2 orientations and all faces were facing directly forward. The mask stimulus was a sequence of greyscale patterns with mean rms contrast of 0.08 and consisting of overlapping circles (Experiment 1) or overlapping faces (Experiment 2) of various sizes and intensities (see Fig. 1) with a mean rms contrast of 0.08. The mask was updated every five video frames (12 Hz).

Target images were cropped to exclude all external facial features (hair, ears, etc.) and transformed to greyscale. They were then resized down to 130 × 130 pixels and standardized in contrast to a value of 0.20 rms contrast. In the experiment, the target stimuli continually ramped up or down in contrast and this was achieved by scaling target contrast using a ramp that ranged from 0.02 (−34 dB) to 1.0 (0 dB) in small steps of 0.07 dB per video frame (at 60 Hz). Multiplying the target by the contrast ramp allowed the target image to slowly ramp up or down over successive video frames (it took ~8 seconds to increase from minimum to maximum contrast) so that the target’s bCFS and reCFS thresholds could be determined. The slow rate of target change ensured that the target would not reach maximum contrast and remain stuck there (as is often the case in bCFS studies). This is particularly important in the tCFS paradigm so that breakthrough and suppression can be quantified as a contrast threshold (and thus the strength of suppression calculated in contrast terms). If the rising contrast arrives at ceiling without yet breaking through, it will eventually breakthrough once adaptation weakens the dominant mask percept but then the target contrast threshold is contaminated by adaptation effects. For that reason, we use masks of quite low contrast (here, 0.08 rms contrast) to allow target breakthrough before reaching maximum contrast.

Varying contrast on a log-linear scale is important and not all bCFS studies observe this detail. The contrast response of visual cortical neurons accelerates initially and then compresses towards an upper asymptote (Albrecht and Hamilton 1982) and this non-linearity is effectively linearized when contrast is expressed on a log scale. Without the log-linearization of contrast, small differences between conditions can be spuriously inflated or large differences diminished depending on the contrast range. Here, contrast values from the standard linear range (0–1, or 0%–100%) are converted to decibels as follows: condB = 20 × log10 (conLin). Whether the target contrast was rising or falling, all contrast change was linear on the dB scale (and thus perceptually linear, too) and suppression depth was always calculated as the contrast difference in decibels between bCFS and reCFS thresholds.

Procedure

In the tCFS paradigm, the target continually changes in contrast, either rising or falling, and participants track their perceptual state to indicate the moment when an invisible rising target breaks through into awareness (i.e. bCFS threshold) or when a visible falling target returns to suppression (reCFS threshold). Thresholds for bCFS and reCFS are defined as the log contrast at the moment when a rising target breaks through into awareness (bCFS) or when a falling target becomes suppressed again (reCFS) and all contrast change is linear on a logarithmic (dB) scale.

Participants were given practice trials with natural objects as target stimuli until they were familiar with the procedure and the changing contrast of the target stimulus. They were instructed to maintain fixation on the fixation cross in the centre of the screen. Trials began with the target visible and slowly declining from high contrast. The participant’s task was to report (with a mouse click) when it became suppressed. The moment suppression was reported, the contrast change reversed sign and the invisible target increased in contrast until it broke through suppression (signalled with another mouse click), which reversed the contrast again so that the target once more declined in contrast towards resuppression, and so on in a cycle, as shown in Fig. 1. (Note that in developing the tCFS method, we compared starting with the target visible and starting with the target invisible. There was little to no difference in thresholds.) In Experiments 1 and 2, the trial ended when 10 reversals were recorded and the five breakthrough contrasts were averaged into an estimate of the bCFS contrast threshold and the five suppression contrasts were averaged into an estimate of the reCFS contrast threshold. [Note that there is a slight downward drift in thresholds over the 10 turning points of the trial (see Fig. 5a of Alais et al. 2024), but it occurs equally for bCFS and reCFS thresholds so that there is no change in suppression depth—the key dependent variable in our study. This is presumably due to adaptation and would occur in standard CFS approaches too.] To help the participant remember whether the target was rising in contrast towards breakthrough or declining towards suppression, an arrowhead was added to the upper or lower end of the vertical line forming the fixation cross. There were 36 trials in total (10 reversals per trial), one for each combination of target identity, emotion and orientation, all presented in a random order. The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Results

The group mean data for Experiment 1 are shown in Fig. 2a. The thresholds (mean contrast threshold expressed in decibels) were analysed in a three-way repeated-measures ANOVA: 2 contrast thresholds (bCFS vs. reCFS) × 2 face orientations (upright vs. inverted) × 3 emotional expressions (fear vs. happy vs. neutral).

Figure 2.

(a) Group mean contrast thresholds for breakthrough (bCFS: dark colours) and suppression (reCFS: light colours) with error bars showing ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM). Apart from an obvious dominance/suppression main effect, the main effects for facial expression and face orientation were not significant. ‘Up’ refers to the upright face condition, ‘Inv’ to the inverted condition. The second y-axis shows contrast in decibels converted back to linear values and shows bCFS thresholds are consistently higher than reCFS thresholds by approximately a factor of five. (b) Group mean suppression depths (±1 SEM), calculated from the thresholds in panel a. Suppression depth is defined as bCFS threshold minus reCFS threshold (in decibels). Mean suppression depth overall was 15.47 dB, several times greater than suppression depths typically obtained in binocular rivalry.

There was a statistically significant main effect of contrast thresholds such that mean threshold for bCFS (M = −10.23 dB) was significantly higher than the mean threshold for reCFS (M = −25.70 dB),  = 169.121, P < .001, ηp2 = 0.914. There was no statistically significant main effect of face inversion, with the mean for upright (M = −18.01 dB) and inverted faces (M = −17.92 dB) being very similar (

= 169.121, P < .001, ηp2 = 0.914. There was no statistically significant main effect of face inversion, with the mean for upright (M = −18.01 dB) and inverted faces (M = −17.92 dB) being very similar ( = 0.181, P = .677, ηp2 = 0.011). There was no statistically significant main effect of emotion, with fear (M = −18.23 dB), happy (M = −17.58 dB), and neutral (M = −18.10 dB) emotional expressions all being very similar (

= 0.181, P = .677, ηp2 = 0.011). There was no statistically significant main effect of emotion, with fear (M = −18.23 dB), happy (M = −17.58 dB), and neutral (M = −18.10 dB) emotional expressions all being very similar ( = 2.339, P = .113, ηp2 = 0.128). The two-way interaction comparing CFS thresholds (bCFS and reCFS) and face orientation was not significant (

= 2.339, P = .113, ηp2 = 0.128). The two-way interaction comparing CFS thresholds (bCFS and reCFS) and face orientation was not significant ( = 3.196, P = .093, ηp2 = 0.166). The other two-way interactions and the three-way interaction were also not significant (all Ps > .09).

= 3.196, P = .093, ηp2 = 0.166). The other two-way interactions and the three-way interaction were also not significant (all Ps > .09).

Figure 2b plots the threshold differences from Fig. 2a as suppression depth (bCFS minus reCFS thresholds, in decibels). Suppression depths were analysed in a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA: 2 face orientations (upright vs. inverted) × 3 emotional expressions (fear vs. happy vs. neutral). Results closely resemble those from the three-way ANOVA: there were no significant main effects of face orientation ( = 3.196, P = .093, ηp2 = 0.166) or face expression (

= 3.196, P = .093, ηp2 = 0.166) or face expression ( = 1.845, P = .174, ηp2 = 0.103), and no interaction between them (

= 1.845, P = .174, ηp2 = 0.103), and no interaction between them ( = 0.778, P = .468, ηp2 = 0.046). Overall, mean suppression depth was 15.47 dB, several times greater than typical binocular rivalry suppression depths (see review in General discussion).

= 0.778, P = .468, ηp2 = 0.046). Overall, mean suppression depth was 15.47 dB, several times greater than typical binocular rivalry suppression depths (see review in General discussion).

Discussion

The aim of Experiment 1 was to use the tCFS paradigm (Alais et al. 2024) to examine breakthrough (bCFS) and suppression (reCFS) thresholds, and thus quantify the depth of suppression, for face images that conveyed different expressions (happy, neutral, and fearful) and were presented either upright or inverted. By measuring suppression depth, we can test claims about priority access to awareness for upright faces relative to inverted faces and for fearful faces relative to other expressions that have been made based on faster breakthrough times for prioritized images (Jiang et al. 2007, Yang et al. 2007). Measuring contrast thresholds is a more direct measure of strength of a stimulus than reaction times for target breakthrough and more generally the validity of relying on breakthrough times has been questioned (Gayet et al. 2014, Pournaghdali and Schwartz 2020).

Overall, mean suppression depth over our six target conditions was 15.47 dB (about three-quarters of a log unit), an amount that did not vary significantly as a function of emotional expression or face orientation. This is a much higher suppression value than is typically found for binocular rivalry suppression. Binocular rivalry studies usually use a probe detection method and the ratio of probe thresholds in dominance and suppression is used to quantify the loss of visual sensitivity during suppression phases of binocular rivalry. Using this method, studies have shown that sensitivity to a probe stimulus presented during suppression is reduced by about 0.2–0.3 log units relative to when the image is visible in the dominance phase (Makous and Sanders 1978, Blake and Camisa 1979, Nguyen et al. 2001, Alais and Melcher 2007). When contrast is expressed in decibels (with 20 dB to the log unit), this corresponds to a suppression depth of 4–6 dB. Therefore, our finding of mean suppression depth of 15.47 dB shows that CFS suppression is several times greater than binocular rivalry suppression.

Our finding of about 15 dB of suppression for CFS corresponds closely with values reported in other studies. Our original tCFS study (Alais et al. 2024) reported 14.7 dB of suppression and the only other two papers that have measured CFS suppression depth (Tsuchiya et al. 2006, Yang and Blake 2012) found very similar values. Tsuchiya et al. found a suppression depth of 14.8 dB, and Yang and Blake found a weighted-average suppression depth of 14.8 dB. (See General discussion for a full analysis comparing suppression depth studies in CFS and binocular rivalry.) The close agreement between these values is impressive. Indeed, it is more impressive given the different methods used. Our estimates were obtained using the tCFS method and those of Tsuchiya et al. and Yang and Blake were obtained using the probe detection method widely used in binocular rivalry.

The fact that we obtain suppression depth estimates that closely match those from the other two studies to have measured it provides a validation of our new tCFS method as a means of estimating CFS suppression depth. It, therefore, rules out the possibility that our failure to observe any significant effects of face orientation or emotion is due to our tCFS method not being equivalent to conventional CFS approaches. Instead, the pattern of constant suppression depth across all conditions in this experiment is more consistent with the alternative interpretation offered in the Introduction. There we hypothesized that suppression depth should be the same for all conditions because interocular suppression occurs early in cortical processing where left- and right-eye signals normally converge into a single binocular stream (area V1) and before image features are integrated into coherent objects in mid-level vision (Conway 2018). The fact that CFS suppression is so strong (several times stronger than binocular rivalry suppression) strengthens this conclusion because it would mean little trace of the suppressed image’s signal would remain to flow through to areas processing faces and facial expression.

Finally, it is notable that rivalry suppression can be deepened in certain circumstances. For example, rivalry suppression is generally greater for more complex, global images (Nguyen et al. 2003) and this is especially so for rivalry between faces (Alais and Parker 2006, Alais and Melcher 2007). Interestingly, binocular rivalry between faces shows a clear face inversion effect, with greater suppression for upright faces than inverted (Alais and Melcher 2007). In Experiment 2, we will adapt the masker stimulus from a dynamic random array of circles to a dynamic random array of faces. This will make the CFS stimuli more analogous to face vs. face rivalry and we will test whether this arrangement will lead to face inversion and expression effects.

Experiment 2

The failure to find either a face inversion effect or a face expression effect in Experiment 1 could potentially be due to the type of masker stimulus used. In a binocular rivalry study examining face vs. face rivalry, Alais and Melcher (2007) found a very strong effect of face inversion, with suppression depth for rivalling upright faces being greater by 8.9 dB than suppression between rivalling inverted faces. Experiment 2 uses a dynamic masker composed of arrays of faces and compares that with the same dynamic masker composed of arrays of circles that was used in Experiment 1. If using the masker composed of faces makes the CFS conditions more like binocular rivalry, this should produce a clear face inversion effect, as observed in Alais and Melcher’s rivalry experiment. This would indicate the involvement of specialized face processing neurons (which have a strong preference for upright faces: Tsao and Livingstone 2008); and in this case, we would expect any facial expression effects to be revealed. We also expect to replicate the findings of Experiment 1 for the masker composed of circles.

Materials and methods

Participants

A sample of 14 (12 females; mean age = 19.14) undergraduate psychology students voluntarily participated in Experiment 2 in exchange for course credit. All had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

Apparatus and stimuli

The apparatus was the same as in Experiment 2 but the mask stimuli differed. Two types of masker were compared: one was a Mondrian mask composed of circles (with the same dimensions and properties as in Experiment 1) and a mask that was composed of circular face patches conveying neutral emotional expressions and which varied in size and luminance in the same way that the Mondrian circles mask did (see Fig. 1). The face mask was set to 10% rms contrast and updated every five video frames (12 Hz).

The target stimuli were identical to Experiment 1 except that only four face identities (two males and two females) were used instead of six (as in Experiment 1, data for the different identities were pooled). The same three emotional expressions (fearful, happy, and neutral) were tested and all target faces were tilted ±10° from vertical so that participants could easily differentiate from the face images in the mask stimuli. Target stimuli were tested in upright and inverted orientation to test for a face inversion effect, resulting in a total of 24 target stimuli (4 identities * 2 orientations * 3 emotions). The 24 stimuli were presented twice in a random order paired with the Mondrian circles mask, and again in a new random order paired with the Mondrian face mask. The design was therefore a factorial combination of 2 orientations * 3 emotions * 2 masks. The dependent variable in Experiment 2 is suppression depth (the difference between bCFS and reCFS thresholds, as in Fig. 2b).

Procedure

The procedure for Experiment 2 was very similar to Experiment 1 with the following changes. The CFS masker was randomly chosen from trial to trial (Mondrian face mask or Mondrian circles mask) and there were 24 trials per mask type. The participant’s task was again to respond to changes in target visibility using a mouse click to indicate either a breakthrough as target contrast rose or a return to suppression as contrast fell.

Results

The bCFS and reCFS thresholds (both are plotted in Fig. 3a) were first tested in separate three-way ANOVAs examining mask type (face mask vs. Mondrian mask) × target face orientation (upright vs. inverted) × target face emotion (fearful vs. happy vs. neutral).

Figure 3.

(a) Group mean contrast thresholds for breakthrough (bCFS: dark colours) and suppression (reCFS: light colours) with error bars showing ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM). The second y-axis shows contrast in decibels converted back to linear values. (b) Group mean suppression depths (±1 SEM) in decibels, calculated from the thresholds in panel a (suppression depth = bCFS threshold minus reCFS threshold). The face targets were more strongly suppressed by the face masker than the Mondrian masker, with no effect of the target face’s orientation or target face emotion.

For the bCFS thresholds, the main effect of mask type ( = 16.309, P = .001, ηp2 = 0.556) was significant, with breakthrough requiring a higher target contrast for the face mask (M = −11.731 dB) than for the Mondrian mask (M = −13.687 dB). There was also a significant main effect of target orientation (

= 16.309, P = .001, ηp2 = 0.556) was significant, with breakthrough requiring a higher target contrast for the face mask (M = −11.731 dB) than for the Mondrian mask (M = −13.687 dB). There was also a significant main effect of target orientation ( = 34.846, P < .001, ηp2 = 0.728), with upright faces breaking through at a lower contrast (M = −13.159 dB) than inverted faces (M = −12.259 dB). There was no main effect of emotion (

= 34.846, P < .001, ηp2 = 0.728), with upright faces breaking through at a lower contrast (M = −13.159 dB) than inverted faces (M = −12.259 dB). There was no main effect of emotion ( = 0.964, P = .395, ηp2 = 0.069) and none of the interactions was significant.

= 0.964, P = .395, ηp2 = 0.069) and none of the interactions was significant.

For the reCFS thresholds, the main effect of mask type was not significant ( = 0.224, P = .644, ηp2 = 0.017) but the effect of target orientation (

= 0.224, P = .644, ηp2 = 0.017) but the effect of target orientation ( = 18.3, P < .001, ηp2 = 0.585) was: suppression of upright faces occurred at a lower contrast (M = −27.721 dB) than upright faces (−26.994 dB). Consistent with the bCFS analysis, and the results of Experiment 1, there was no main effect of emotion (

= 18.3, P < .001, ηp2 = 0.585) was: suppression of upright faces occurred at a lower contrast (M = −27.721 dB) than upright faces (−26.994 dB). Consistent with the bCFS analysis, and the results of Experiment 1, there was no main effect of emotion ( = 0.252, P = .779, ηp2 = 0.019) and none of the interactions was significant.

= 0.252, P = .779, ηp2 = 0.019) and none of the interactions was significant.

Figure 3b plots the suppression depth data (i.e. the difference between the bCFS and reCFS thresholds). A three-way ANOVA conducted on suppression depth (as for the bCFS and reCFS data: face mask vs. Mondrian mask × upright vs. inverted target face × fearful vs. happy vs. neutral target face) revealed only a significant main effect for mask type ( = 17.929, P < .001, ηp2 = 0.580), with the face mask (M = 15.489 dB) producing stronger suppression than the Mondrian mask (M = 13.808 dB). Suppression depth showed no effect of orientation (

= 17.929, P < .001, ηp2 = 0.580), with the face mask (M = 15.489 dB) producing stronger suppression than the Mondrian mask (M = 13.808 dB). Suppression depth showed no effect of orientation ( = 0.877, P = .366, ηp2 = 0.063) or emotion (

= 0.877, P = .366, ηp2 = 0.063) or emotion ( = 0.276, P = .761, ηp2 = 0.021), and none of the interactions was significant.

= 0.276, P = .761, ηp2 = 0.021), and none of the interactions was significant.

Discussion

The aim of Experiment 2 was to test whether a CFS mask composed of faces would deepen suppression and produce a face inversion effect. In binocular rivalry, face vs. face rivalry does produce deeper suppression than a face vs. a non-face and does reveal a strong face inversion effect (Alais and Melcher 2007), indicating the involvement of face-specialized processes whose strong preference is for upright faces (Tsao and Livingstone 2008). Experiment 2 did produce a significant main effect of mask type, with face targets undergoing greater suppression when paired with the face mask compared to the Mondrian mask, however, there was no significant effect of target face orientation or of target face emotion. The absence of a face inversion effect implies an absence of face processing, which is consistent also with there being no significant effect of target face emotion. Experiment 2, therefore, replicates the same two null results from Experiment 1: no effect of face orientation or emotion.

The main effect of mask type in Experiment 2 is interesting because the characteristics of the masker are often overlooked in CFS studies, where the emphasis is mainly on the target and how quickly it achieves breakthrough. In binocular rivalry studies, however, it is well known that the stimulus driving one eye will influence the other (Levelt 1965, Alais 2012). As CFS is another form of interocular suppression then it is reasonable to expect that mask properties might influence visibility of the target stimulus. A number of studies have examined both temporal and spatial properties of the mask stimulus. Temporally, target suppression times are longer for masks filtered to contain lower temporal frequencies (Han et al. 2016, Han et al. 2018) or when mask update rates are lower (Zhu et al. 2016). Spatially, CFS is stronger when the target and mask share a similar spatial frequency spectrum (Yang and Blake 2012) or a similar orientation spectrum (Yang and Blake 2012, Han et al. 2018, Han and Alais 2018, Drewes et al. 2023). Similarly, suppression depth is stronger in binocular rivalry when the rivalling stimuli have similar stimulus properties (Alais and Melcher 2007, Stuit et al. 2009). Based on these results, a deeper suppression of face targets by face masks relative to Mondrian masks is expected given their spectral similarity.

Interestingly, Experiment 2 showed no effect of face emotion at all. Neither bCFS thresholds, reCFS thresholds or suppression depth showed a main effect emotion or none of the interactions involving emotion were significant. Experiment 1 also failed to find an effect of emotion. Perception of fearful faces in CFS has been widely discussed in previous CFS studies. Originally, it was claimed that fearful faces have preferential access to awareness and that was why they produced faster breakthrough times than other faces (Yang et al. 2007). Subsequently, alternative accounts emerged claiming that low-level image properties could explain the differences in breakthrough times (Gray et al. 2013). The significance of the low-level account is that breakthrough differences are explicable at the level of features driving primary visual cortex without needing to invoke face-specialized processing that occurs later in inferotemporal cortex. The low-level account is thus consistent with an early suppression model in which CFS targets are suppressed early in cortical processing before they reach face processing regions. For example, features such as local maxima of image contrast around the eyes and mouth for fearful facial expressions could drive greater visibility of the face target and yield lower bCFS thresholds. A target with local regions of high contrast, once it has broken through into visibility, would be more likely to resist resuppression and therefore produce equivalently lower reCFS thresholds. Because both bCFS and reCFS thresholds shift lower, there is no resulting change in suppression depth.

The last point about image salience inducing equivalent changes in bCFS and reCFS is important. It underscores the point that false conclusions can be drawn when bCFS is measured without a suppression threshold. Many previous studies have drawn conclusions based on differences in bCFS (e.g. lower bCFS indicating priority processing) that should be reconsidered given that reCFS was not measured. It is entirely plausible that changes in bCFS would be matched by equivalent changes in reCFS and thus produce identical suppression depth. If there is no reduction in suppression depth, it undermines the claimed priority processing. Instead, it is more plausibly explained by low-level stimulus properties affecting image salience and similarly shifting both thresholds. The importance of measuring both thresholds is also seen when comparing the ANOVA results for bCFS and reCFS against the suppression depth ANOVA. The bCFS data in Fig. 3a showed a significant face orientation effect, as did the reCFS data. However, when the threshold difference was calculated to obtain suppression depth, we found no effect of face orientation. That is, the orientation effect for the bCFS data was reflected in a parallel change in the reCFS data so that suppression depth showed no effect of orientation.

It still remains to be explained why there was an effect of face orientation in the bCFS and reCFS thresholds (Fig. 3a), even if their difference (suppression depth) showed no orientation effect. Because the face inversion effect is often attributed to the strong preference for upright faces in face-selective neurons, the question arises whether our result is due to the involvement of face processing areas in CFS (contrary to our low-level account). Our view is that the face orientation effect in the bCFS and reCFS thresholds has a low-level explanation, arising because of an attentional bias towards the upper half of objects (Chambers et al. 1999). This bias, present even in randomly shaped objects, is stronger in ecologically relevant stimuli such as animals and faces (Langley and McBeath 2023). Moreover, the most salient facial features for recognition and rapid detection—the eyes (Gosselin and Schyns 2001, Sadr et al. 2003, Kauffmann et al. 2021, Broda et al. 2023)—are located in the upper half. We propose that the orientation effect could be driven simply by a bias to attend to the upper part of the stimulus region—where the eyes are located—which would favour detection of upright faces and impair inverted faces. This low-level account does not require any face-specific processing. It, therefore, squares with our claim that CFS suppression is strong and early in the visual processing pathway and is consistent with their being no effect of face emotion in either experiment.

Overall, Experiment 2 provides no evidence for face-specialized processing during CFS suppression or for priority processing of fearful expressions and also highlights the importance of measuring both bCFS and reCFS thresholds.

General discussion

In two experiments, we studied visual suppression of target images using a new method known as ‘tracking’ CFS. The advantages of tCFS are that it is very quick and efficient and that it returns contrast thresholds for both breakthrough (bCFS) and suppression (reCFS) of the target. The difference between the bCFS and reCFS thresholds indicates the strength of CFS suppression, a quantity we call ‘suppression depth’ to be consistent with the term used for several decades in the binocular rivalry literature (Blake 1989, Holopigian 1989, Nguyen et al. 2003). Moreover, these are expressed in terms of contrast rather than breakthrough times and thus map more directly onto neural activity levels to facilitate comparison with neurophysiology, neuroimaging, and modelling. With these measures, we tested whether certain images, such as fearful faces, have priority access to awareness. The topic of visual processing outside of conscious awareness has captivated researchers but remains controversial (Gayet et al. 2014, Yang et al. 2014, Stein 2019, Pournaghdali and Schwartz 2020). Studies have generally employed the breaking CFS method, however, a reliance on bCFS is problematic as it does not provide a suppression threshold and so cannot quantify suppression strength (unless a number of strong assumptions are made: discussed below). Addressing this question with tCFS and face targets, our data provide no evidence in support of priority processing as we obtained no face inversion effect and no effect of facial expression. Instead, our findings support the conclusion that all images in CFS undergo a similar strong suppression at an early stage of visual processing that precedes specialized processing of faces and their emotions.

The absence of a face inversion effect has important implications. The comparison between an upright and inverted faces is a critical contrast because both images have the same contrast and low-level visual features but inversion will largely eliminate global face processing in the fusiform face area where there is a strong preference for upright faces (Kanwisher et al. 1998, Tsao and Livingstone 2008). Thus, if upright faces have a processing advantage during suppression, as has been claimed (Jiang et al. 2007), then they are presumably closer to awareness and should have a lower breakthrough threshold. In neither of our experiments did we observe this, suggesting an equivalence for upright and inverted faces during suppression. Supporting this conclusion, the effect of emotional expression was not significant in either experiment. It has been claimed that fearful faces have priority access to awareness (Ohman and Mineka 2001, Vuilleumier et al. 2002), and some CFS studies find support for this (Yang et al. 2007, Adams et al. 2010). If there were priority for fearful faces, we would expect fearful faces to have a lower bCFS threshold as they would be closer to the awareness threshold than happy or neutral faces, yet this was not observed. Both effects are parsimoniously explained by assuming that interocular suppression in CFS occurs early in visual processing at a level where images are analysed as a collection of local features, not as an integrated object activating global processing in mid-level vision areas such as area fusiform face area. At such a level, likely area V1 (Yuval-Greenberg and Heeger 2013), the suppressed stimulus has no objecthood and thus suppression should operate uniformly and non-selectively.

The proposed early (i.e. low-level) and non-selective suppression process underlying CFS fits with other findings concerning face emotion in CFS contexts. For instance, there is no adaptation to emotion for faces suppressed by CFS (Yang et al. 2010), and to the extent that a fear advantage has been shown in bCFS studies, it can be fully accounted for by low-level image properties, primarily by enhanced contrast in fearful faces (such as around the eyes and mouth) boosting their effective contrast (Hedger et al. 2015). Primary visual cortex has long been thought to play a central role in visual awareness (Tong 2003) and there is neuroimaging evidence to support early suppression in CFS. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, Yuval-Greenberg and Heeger (2013) studied CFS suppression amplitude in three cortical regions of interest defined in V1, V2, and V3. They found strong suppression in V1, and equivalent suppression in V2 and V3. Because there was no evidence of suppression accumulating in strength along the visual pathway from V1 to V3, they concluded that CFS suppression was entirely mediated in V1 and that subsequent areas along the visual pathway simply inherit the suppression from V1. This fits with the lack of face effects we report here, and also with a host of studies showing that CFS depends on a range of low-level stimulus features such as spatial frequency (Yang and Blake 2012), temporal frequency (Han et al. 2016, Han et al. 2018), and orientation (Yang and Blake 2012, Gao et al. 2018) which are all encoded by neurons in V1 specifically tuned for narrow ranges along these stimulus dimensions.

One of the key advantages of the tCFS method is that it provides the suppression depth of every condition tested and does so quickly and easily. Such efficiency is a key advantage of tCFS compared to traditional methods for measuring suppression depth. For example, only two previous studies have measured CFS suppression depth and one of them noted that their experiments took 2 and 5 hours, respectively. In our experiments reported here, which measure multiple conditions within a 1-hour session, we found an average suppression depth of 15.47 dB. This agrees closely with the value reported in our first tCFS paper (Alais et al. 2024) of 14.8 dB. In our first paper, suppression depth did not vary between any of the conditions despite testing very different target categories. In that paper, e.g. gratings, faces, objects, and noise patches all exhibited the same degree of suppression. Here, a consistent level of suppression depth was reported for all conditions of Experiment 1, and also to an extent in Experiment 2. The second experiment did yield a main effect of masker type but within each level of masker (face mask vs. Mondrian mask) there were no differences between the six conditions of orientation × emotion. Two interesting questions arise from this: (i) when put in context, how strong (or weak) is a suppression of ~15 dB, and (ii) why does CFS suppression not vary with the type of target being suppressed?

To put our estimate of CFS suppression depth (~15 dB) in context, we can compare it with other studies of CFS suppression depth. Of ~400 CFS papers published at the time of writing, only two have measured suppression depth (Tsuchiya et al. 2006, Yang and Blake 2012) and both found very similar values those we report. Tsuchiya et al. (2006) used a flickering Mondrian mask in one eye to suppress a grating of 10% contrast in the other and found the grating needed a contrast increment of 44.7% to be detected during CFS suppression. Tsuchiya et al. express this as a log dominance-to-suppression ratio of 0.75. Equivalently, their 44.7% increment can be expressed in dB: 20*log10 ((10 + 44.7)/10) = 14.8 dB. Thus, their estimate closely agrees with ours. A second study (Yang and Blake 2012) also used the probe increment method and measured suppression depth as a function of target spatial frequency using sine-wave gratings. Suppression was stronger at lower frequencies and weakened at higher frequencies. In practice, CFS studies almost always use real-world objects as targets and such images are spectrally broadband with a typical 1/f (pink) spatial frequency profile (see Han et al. 2016, 2021). When averaging their suppression depths over spatial frequency with a 1/f weighting profile, Yang and Blake’s data produces a mean dominance-to-suppression ratio of 0.78, equating to 15.6 dB.

The very close agreement between our estimate of suppression depth using tCFS and those using the traditional probe increment method validates tCFS as an accurate method for measuring CFS suppression depth. It is also worth comparing these estimates with those obtained in binocular rivalry, a closely related form of interocular suppression. A large number of studies have measured suppression depth in binocular rivalry (Makous and Sanders 1978, Blake and Camisa 1979, Hollins and Bailey 1981, Ooi and Loop 1994, Nguyen et al. 2001, 2003, Watanabe et al. 2004, Tsuchiya et al. 2006, Alais and Melcher 2007, Bhardwaj et al. 2008) and the mean suppression depth from these studies is 4.1 dB. Therefore, CFS suppression depth is about three to four times greater than binocular rivalry suppression depth.

The strength of CFS suppression likely explains our finding here and by Alais et al. (2024) that CFS suppression does not vary with the type of target being suppressed. Once a target is strongly suppressed, there is little residual signal left to filter through to subsequent stages of visual processing where global and semantic properties are processed. This fits with neuroimaging work showing CFS suppression is strong in V1 and does not accumulate further in subsequent areas V2 and V3 (Yuval-Greenberg and Heeger 2013). This differs from binocular rivalry where suppression is not as strong initially and accumulates at subsequent stages, as shown by single-unit neurophysiology (Logothetis 1998) and by behavioural data showing deepening rivalry suppression along the motion and form visual processing pathways (Nguyen et al. 2003) and greater rivalry suppression between higher-level images (e.g. faces) than gratings (Alais and Melcher 2007). Weaker signal suppression initially in rivalry leaves more residual signal to flow on to higher areas. This would explain why top-down signals modulate rivalry (Alais and Blake 1998, van Boxtel et al. 2008) and why a face inversion effect occurs in rivalry (Alais and Melcher 2007). In CFS, the much stronger initial suppression largely prevents signals from reaching mid-level areas selective for faces and which guide top-down attention.

Conclusion

In summary, this article aimed to examine claims of processing without awareness in the CFS paradigm, specifically focussing on faces. Using a new tCFS method which provides suppression thresholds (reCFS) and suppression depth in addition to the commonly used breakthrough threshold (bCFS), we find no evidence for a face inversion effect (upright faces showed no breakthrough advantage or reduced suppression depth) and no priority for fearful expressions (no breakthrough advantage or reduced suppression depth). We interpret these results in terms of CFS exerting a very strong suppression of target images and at an early stage of visual processing. Being both strong and early, CFS suppression acts non-selectively on target images because they are effectively collections of features at this stage rather than coherent global objects.

Contributor Information

David Alais, School of Psychology, The University of Sydney, Brennan McCallum Building (A18), Manning Road, NSW 2006, Australia.

Jacob Coorey, School of Psychology, The University of Sydney, Brennan McCallum Building (A18), Manning Road, NSW 2006, Australia.

Matthew J Davidson, School of Psychology, The University of Sydney, Brennan McCallum Building (A18), Manning Road, NSW 2006, Australia.

Author contributions

David Alais (Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing—review & editing [equal]), Lina Ye (Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing—review & editing [equal]), Jacob Coorey (Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft [supporting]), and Matthew J. Davidson (Conceptualization, Methodology [supporting], Supervision [equal])

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

References

- Abir Y, Sklar AY, Dotsch R et al. The determinants of consciousness of human faces. Nat Hum Behav 2018;2:194–9. 10.1038/s41562-017-0266-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams WJ, Gray KL, Garner M et al. High-level face adaptation without awareness. Psychol Sci 2010;21:205–10. 10.1177/0956797609359508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alais D. Binocular rivalry: competition and inhibition in visual perception. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci 2012;3:87–103. 10.1002/wcs.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alais D, Blake R. Interactions between global motion and local binocular rivalry. Vis Res 1998;38:637–44. 10.1016/S0042-6989(97)00190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alais D, Blake R, Eds.. Binocular Rivalry. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Alais D, Blake R. Binocular rivalry and perceptual ambiguity. In: Wagemans J (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Perceptual Organization. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alais D, Melcher D. Strength and coherence of binocular rivalry depends on shared stimulus complexity. Vis Res 2007;47:269–79. 10.1016/j.visres.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alais D, Parker A. Independent binocular rivalry processes for motion and form. Neuron 2006;52:911–20. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alais D, O'Shea RP, Mesana-Alais C et al. On binocular alternation. Perception 2000;29:1437–45. 10.1068/p3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alais D, Coorey J, Blake R et al. tCFS: a new ‘CFS tracking’ paradigm reveals uniform suppression depth regardless of target complexity or salience. eLife 2024;12:91019. 10.7554/eLife.91019.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht DG, Hamilton DB. Striate cortex of monkey and cat: contrast response function. J Neurophysiol 1982;48:217–37. 10.1152/jn.1982.48.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida J, Pajtas PE, Mahon BZ et al. Affect of the unconscious: visually suppressed angry faces modulate our decisions. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 2013;13:94–101. 10.3758/s13415-012-0133-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apthorp D, Wenderoth P, Alais D. Motion streaks in fast motion rivalry cause orientation-selective suppression. J Vis 2009;9:10.1–14. 10.1167/9.5.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj R, O'Shea RP, Alais D et al. Probing visual consciousness: rivalry between eyes and images. J Vis 2008;8:2.1–13. 10.1167/8.11.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake R. A neural theory of binocular rivalry. Psychol Rev 1989;96:145–67. 10.1037/0033-295X.96.1.145 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=2648445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake R, Camisa J. On the inhibitory nature of binocular rivalry suppression. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 1979;5:315–23. 10.1037/0096-1523.5.2.315 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=528942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake R, Fox R. Adaptation to invisible gratings and the site of binocular rivalry suppression. Nature 1974a;249:488–90. 10.1038/249488a0 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=4834239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake R, Fox R. Binocular rivalry suppression: insensitive to spatial frequency and orientation change. Vis Res 1974b;14:687–92. 10.1016/0042-6989(74)90065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH. The psychophysics toolbox. Spat Vis 1997;10:433–6. 10.1163/156856897X00357 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9176952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese BB. The influence of figure-ground relationships in binocular rivalry. Psychol Rev 1909;16:410–5. 10.1037/h0075805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broda MD, Haddad T, de Haas B. Quick, eyes! Isolated upper face regions but not artificial features elicit rapid saccades. J Vis 2023;23:5. 10.1167/jov.23.2.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers KW, McBeath MK, Schiano DJ et al. Tops are more salient than bottoms. Percept Psychophys 1999;61:625–35. 10.3758/bf03205535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YC, Yeh SL. Look into my eyes and I will see you: unconscious processing of human gaze. Conscious Cogn 2012;21:1703–10. 10.1016/j.concog.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway BR. The organization and operation of inferior temporal cortex. Annu Rev Vis Sci 2018;4:381–402. 10.1146/annurev-vision-091517-034202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewes J, Witzel C, Zhu W. Feature-based interaction between masks and target in continuous flash suppression. Sci Rep 2023;13:4696. 10.1038/s41598-023-31659-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahle M. Binocular rivalry: suppression depends on orientation and spatial frequency. Vis Res 1982;22:787–800. 10.1016/0042-6989(82)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox R, Herrmann J. Stochastic properties of binocular rivalry alternations. Percept Psychophys 1967;2:432–6. 10.3758/BF03208783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao TY, Ledgeway T, Lie AL et al. Orientation tuning and contrast dependence of continuous flash suppression in amblyopia and normal vision. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018;59:5462–72. 10.1167/iovs.18-23954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayet S, Van der Stigchel S, Paffen CL. Breaking continuous flash suppression: competing for consciousness on the pre-semantic battlefield. Front Psychol 2014;5:460. 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin F, Schyns PG. Bubbles: a technique to reveal the use of information in recognition tasks. Vis Res 2001;41:2261–71. 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray KL, Adams WJ, Hedger N et al. Faces and awareness: low-level, not emotional factors determine perceptual dominance. Emotion 2013;13:537–44. 10.1037/a0031403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Alais D. Strength of continuous flash suppression is optimal when target and masker modulation rates are matched. J Vis 2018;18:3. 10.1167/18.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Lunghi C, Alais D. The temporal frequency tuning of continuous flash suppression reveals peak suppression at very low frequencies. Sci Rep 2016;6:35723. 10.1038/srep35723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Blake R, Alais D. Slow and steady, not fast and furious: slow temporal modulation strengthens continuous flash suppression. Conscious Cogn 2018;58:10–9. 10.1016/j.concog.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Alais D, Palmer C. Dynamic face mask enhances continuous flash suppression. Cognition 2021;206:104473. 10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedger N, Adams WJ, Garner M. Fearful faces have a sensory advantage in the competition for awareness. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 2015;41:1748–57. 10.1037/xhp0000127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollins M, Bailey GW. Rivalry target luminance does not affect suppression depth. Percept Psychophys 1981;30:201–3. 10.3758/bf03204480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holopigian K. Clinical suppression and binocular rivalry suppression: the effects of stimulus strength on the depth of suppression. Vis Res 1989;29:1325–33. 10.1016/0042-6989(89)90189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Costello P, He S. Processing of invisible stimuli: advantage of upright faces and recognizable words in overcoming interocular suppression. Psychol Sci 2007;18:349–55. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MS, Blake R. What causes alternations in dominance during binocular rivalry? Atten Percept Psychophys 2010;72:179–86. 10.3758/APP.72.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N, Tong F, Nakayama K. The effect of face inversion on the human fusiform face area. Cognition 1998;68:B1–11. 10.1016/s0010-0277(98)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffmann L, Khazaz S, Peyrin C et al. Isolated face features are sufficient to elicit ultra-rapid and involuntary orienting responses toward faces. J Vis 2021;21:4. 10.1167/jov.21.2.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfranco RC, Rabagliati H, Carmel D. The importance of awareness in face processing: a critical review of interocular suppression studies. Behav Brain Res 2023;437:114116. 10.1016/j.bbr.2022.114116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley MD, McBeath MK. Vertical attention bias for tops of objects and bottoms of scenes. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 2023;49:1281–95. 10.1037/xhp0001117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levelt WJM. On Binocular Rivalry. Soesterberg, The Netherlands: Institute for Perception RVO-TNO, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK. Single units and conscious vision. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1998;353:1801–18. 10.1098/rstb.1998.0333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist D, Flykt A, Öhman A. Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces. APA PsycTests, 1998. 10.1037/t27732-000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Makous W, Sanders RK. Suppression interactions between fused patterns. In: Armington AC, Krauskopf J, Wooten BR (eds.), Visual Psychophysics and Physiology. New York: Academic Press, 1978. 10.1016/B978-0-12-062260-3.50020-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VA, Freeman AW, Wenderoth P. The depth and selectivity of suppression in binocular rivalry. Percept Psychophys 2001;63:348–60. 10.3758/BF03194475 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=11281109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VA, Freeman AW, Alais D. Increasing depth of binocular rivalry suppression along two visual pathways. Vis Res 2003;43:2003–8. 10.1016/S0042-6989(03)00314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohman A, Mineka S. Fears, phobias, and preparedness: toward an evolved module of fear and fear learning. Psychol Rev 2001;108:483–522. 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi TL, Loop MS. Visual suppression and its effect upon color and luminance sensitivity. Vis Res 1994;34:2997–3003. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=7975334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker A, Alais D. A bias for looming stimuli to predominate in binocular rivalry. Vis Res 2007;47:2661–74. 10.1016/j.visres.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pournaghdali A, Schwartz BL. Continuous flash suppression: known and unknowns. Psychon Bull Rev 2020;27:1071–103. 10.3758/s13423-020-01771-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadr J, Jarudi I, Sinha P. The role of eyebrows in face recognition. Perception 2003;32:285–93. 10.1068/p5027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar AY, Levy N, Goldstein A et al. Reading and doing arithmetic nonconsciously. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:19614–9. 10.1073/pnas.1211645109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein T. The breaking continuous flash suppression paradigm: review, evaluation, and outlook. In: Hesselmann G (ed.), Transitions between Consciousness and Unconsciousness. New York: Routledge, 2019, 1–38. 10.4324/9780429469688-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein T, Hebart MN, Sterzer P. Breaking continuous flash suppression: a new measure of unconscious processing during interocular suppression? Front Hum Neurosci 2011;5:167. 10.3389/fnhum.2011.00167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart LH, Ajina S, Getov S et al. Unconscious evaluation of faces on social dimensions. J Exp Psychol Gen 2012;141:715–27. 10.1037/a0027950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuit SM, Cass J, Paffen CL et al. Orientation-tuned suppression in binocular rivalry reveals general and specific components of rivalry suppression. J Vis 2009;9:17.1–15. 10.1167/9.11.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong F. Primary visual cortex and visual awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci 2003;4:219–29. 10.1038/nrn1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao DY, Livingstone MS. Mechanisms of face perception. Annu Rev Neurosci 2008;31:411–37. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya N, Koch C. Continuous flash suppression reduces negative afterimages. Nat Neurosci 2005;8:1096–101. 10.1038/nn1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya N, Koch C, Gilroy LA et al. Depth of interocular suppression associated with continuous flash suppression, flash suppression, and binocular rivalry. J Vis 2006;6:1068–78. 10.1167/6.10.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boxtel JJ, Alais D, van Ee R. Retinotopic and non-retinotopic stimulus encoding in binocular rivalry and the involvement of feedback. J Vis 2008;8:17.1–10. 10.1167/8.5.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier P, Armony JL, Clarke K et al. Neural response to emotional faces with and without awareness: event-related fMRI in a parietal patient with visual extinction and spatial neglect. Neuropsychologia 2002;40:2156–66. 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wales R, Fox R. Increment detection thresholds during binocular rivalry suppression. Percept Psychophys 1970;8:90–4. 10.3758/BF03210180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Alais D, Blake R et al. CFS-crafter: an open-source tool for creating and analyzing images for continuous flash suppression experiments. Behav Res Methods 2023;55:2004–20. 10.3758/s13428-022-01903-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Paik Y, Blake R. Preserved gain control for luminance contrast during binocular rivalry suppression. Vis Res 2004;44:3065–71. 10.1016/j.visres.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E, Blake R. Deconstructing continuous flash suppression. J Vis 2012;12:8. 10.1167/12.3.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YH, Yeh SL. Unconscious processing of facial expression as revealed by affective priming under continuous flash suppression. Psychon Bull Rev 2018;25:2215–23. 10.3758/s13423-018-1437-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E, Zald DH, Blake R. Fearful expressions gain preferential access to awareness during continuous flash suppression. Emotion 2007;7:882–6. 10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E, Hong SW, Blake R. Adaptation aftereffects to facial expressions suppressed from visual awareness. J Vis 2010;10:24. 10.1167/10.12.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E, Brascamp J, Kang MS et al. On the use of continuous flash suppression for the study of visual processing outside of awareness. Front Psychol 2014;5:724. 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuval-Greenberg S, Heeger DJ. Continuous flash suppression modulates cortical activity in early visual cortex. J Neurosci 2013;33:9635–43. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4612-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Zhang L, Liu J et al. Specificity of face processing without awareness. Conscious Cogn 2010;19:408–12. 10.1016/j.concog.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Drewes J, Melcher D. Time for awareness: the influence of temporal properties of the mask on continuous flash suppression effectiveness. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159206. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]