Abstract

Three NifS-like proteins, IscS, CSD, and CsdB, from Escherichia coli catalyze the removal of sulfur and selenium from l-cysteine and l-selenocysteine, respectively, to form l-alanine. These enzymes are proposed to function as sulfur-delivery proteins for iron-sulfur cluster, thiamin, 4-thiouridine, biotin, and molybdopterin. Recently, it was reported that selenium mobilized from free selenocysteine is incorporated specifically into a selenoprotein and tRNA in vivo, supporting the involvement of the NifS-like proteins in selenium metabolism. We here report evidence that a strain lacking IscS is incapable of synthesizing 5-methylaminomethyl-2-selenouridine and its precursor 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine (mnm5s2U) in tRNA, suggesting that the sulfur atom released from l-cysteine by the action of IscS is incorporated into mnm5s2U. In contrast, neither CSD nor CsdB was essential for production of mnm5s2U and 5-methylaminomethyl-2-selenouridine. The lack of IscS also caused a significant loss of the selenium-containing polypeptide of formate dehydrogenase H. Together, these results suggest a dual function of IscS in sulfur and selenium metabolism.

Sulfur and selenium are similar in many of their chemical properties. This similarity allows many enzymes of sulfur metabolism to catalyze the analogous reactions with selenium-containing substrates (1–3). Nevertheless, several enzymes, such as selenophosphate synthetase (4), selenocysteine methyltransferase (5), and selenocysteine lyase (6, 7), strictly distinguish these two elements. The enzymatic discrimination between selenium-containing substrates and the corresponding sulfur analogs is important for cells to metabolize selenium-containing biomolecules without disturbing sulfur metabolism. The specific incorporation of selenium into several proteins and tRNAs has been identified (1, 8). Selenium is present as an essential selenocysteine residue in the polypeptide chains of various selenoproteins including bacterial formate dehydrogenase (9) and mammalian glutathione peroxidase (10). Selenium-containing tRNAs found in prokaryotes contain 5-methylaminomethyl-2-selenouridine (mnm5se2U) in the wobble position of the anticodons in glutamate, lysine, and glutamine isoaccepting tRNAs (11). The biosynthetic pathway for mnm5se2U has been partly characterized as shown in Fig. 1. The 2-thiolation step was shown to require the mnmA gene product, but neither the specific function of the gene product nor the mechanism of the thiolation reaction is clarified (12). The replacement of sulfur by selenium requires monoselenophosphate (13). The selD gene product, selenophosphate synthetase, catalyzes the synthesis of monoselenophosphate from ATP and selenide. Monoselenophosphate serves as a selenium donor for both mnm5se2U in tRNA and a specific selenocysteine residue of selenoproteins (14). Lacourciere et al. (15) showed that selenium derived from l-selenocysteine by the action of Escherichia coli NifS-like proteins can be used as the substrate for selenophosphate synthetase in vitro. More recently, it has been demonstrated that l-selenocysteine provided in the growth medium is effectively used as a selenium source for in vivo selenophosphate-dependent biosynthesis (16). These results suggest that the NifS-like proteins function as components of a selenium delivery system for the biosynthesis of selenoproteins and selenium-containing tRNAs.

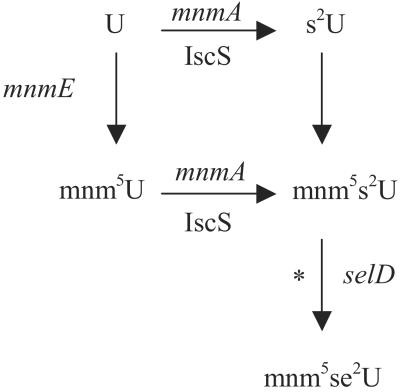

Figure 1.

Proposed pathway for the biosynthesis of mnm5se2U in tRNA. s2U, mnm5U, and mnm5s2U denote 2-thiouridine, 5-methylaminomethyluridine, and 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine, respectively. The asterisk denotes one or more additional gene products that are not identified.

E. coli NifS-like proteins are pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent enzymes that catalyze the removal of sulfur and selenium from cysteine and selenocysteine, respectively. E. coli encodes three nifS-like genes called iscS, csdA, and csdB (17–19). Specific functions have been suggested for CSD (the csdA gene product) as a sulfur donor for molybdopterin biosynthesis (20) and for CsdB as an enzyme involved in selenium (18) or iron (21) metabolism. Recent studies showed that IscS provides sulfur for the biosynthesis of iron-sulfur clusters, thiamin, biotin, and 4-thiouridine (s4U) in tRNA (22–26). In addition to IscS, s4U synthesis requires the thiamin biosynthetic enzyme ThiI, Mg-ATP, and l-cysteine as the sulfur donor. Kambampati and Lauhon (27) have shown that the sulfane sulfur generated by IscS is first transferred to ThiI and then to tRNA during the in vitro synthesis of s4U. Considering that the transfer of sulfur from l-cysteine to a variety of sulfur-containing molecules involves the NifS-like proteins, these enzymes may provide sulfur for the biosynthesis of thionucleotides such as 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine (mnm5s2U) and 2-(methylthio-N6-isopentenyl)adenosine (28) in tRNA. To determine whether the three NifS-like proteins in E. coli were involved in the biosynthesis of mnm5se2U and mnm5s2U, we analyzed 75Se- and 35S-labeled tRNA nucleosides isolated from individual strains lacking iscS, csdA, or csdB. The effect of the iscS deletion on the biosynthesis of a selenoprotein, formate dehydrogenase H (FDHH), also was investigated.

Experimental Procedures

Media and Reagents.

In general, the rich medium used was LB medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose and selenite where indicated. l-Selenocysteine was synthesized as described (29). [75Se]Selenite was purchased from the University of Missouri Research Reactor Facility, Columbia, MO. l-[35S]Cysteine was purchased from Amersham Pharmacia.

Plasmids and Bacterial Strains.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmid pBEN66 was a gift from Y. Yamamoto (Hyogo College of Medicine). A csdB-disrupted strain, H1489, was a gift from K. Hantke, Universität Tübingen (21). An iscS-deleted strain, iscS∷neo23, was constructed by Tokumoto and Takahashi (26). An mnmA− strain, TH159, was a gift from T. Hagervall, Umeå University (30). A csdA-disrupted strain was constructed as follows. A 527-bp fragment of csdA lacking the start and stop codons was amplified by PCR with primers 5′-CTCGTCCCCTGGCTGATG-3′ and 5′-CTTTCGGCCTGGTTGATA-3′, blunt-ended, and inserted into the EcoRV site of pBEN66. The resulting plasmid, pBENifS2, was digested with NotI to yield a 1,917-bp fragment containing the 527-bp csdA fragment and a kanamycin-resistance (kan) gene. The fragment was self-ligated and introduced into W3110. The self-ligated circular product cannot replicate because of the lack of its own ori. A mutant strain, HM75, with a csdA gene disrupted by the insertion of kan was selected on solid LB medium containing 25 μg/ml of kanamycin. Disruption of the gene was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis. P1 phages were generated from iscS∷neo23, HM75, and H1489. The ΔiscS∷kan, csdA∷kan, and sufS∷MudI(Apr lac) markers were transduced into MC4100 by selection on LB plates containing an appropriate antibiotic, generating strains SK23, SK75, and SK100, respectively. Standard methods were used for genetic manipulation according to Miller (31) and Sambrook et al. (32).

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

| Genotype/property | Ref./source | |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| MC4100 | F−araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 ptsF25 deoC1 relA1 flbB5301 rpsL150λ− | NIG collection |

| iscS∷neo23 | F− ΔiscS∷kan | 26 |

| H1489 | aroB rpsL sufS∷MudI | 21 |

| W3110 | F−IN(rrnD-rrnE)1 | NIG collection |

| HM75 | W3110 csdA∷kan | This work |

| TH159 | F−ara Δ(lac-proB) nalA argEAm rif thi metB supB val(R) mnmE fadR13∷Tn10 mnmA107 | 30 |

| WL400 | MC4100 selD204∷cam | 35 |

| SK23 | MC4100 ΔiscS∷kan | This work |

| SK100 | MC4100 sufS∷MudI | This work |

| SK75 | MC4100 csdA∷kan | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBEN66 | Gene disruption plasmid, Kmr | Y. Yamamoto |

| pBENifS2 | pBEN66 containing csdA disruption construct, Kmr | This work |

NIG, National Institute of Genetics.

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoretic Analysis of 75Se-Labeled Protein and tRNA.

E. coli cells were grown anaerobically overnight at 37°C in the LB medium supplemented with 0.1 μM Na2SeO3 and 20 μCi of Na275SeO3 per 15 ml of culture. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g), resuspended in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and lysed by freeze-thawing in liquid nitrogen. Aliquots of supernatants containing 6–8 μg of protein were analyzed for 75Se-containing tRNA by SDS/PAGE (12%) and PhosphorImager detection of radioactivity.

tRNA Digestion and Nucleoside Analysis.

E. coli cells were grown in LB medium and labeled with 20 μCi of Na275SeO3 or 10 μCi of l-[35S]cysteine, and 75Se- or 35S-labeled tRNA was isolated as described (11, 16). Nuclease digestion of tRNA was performed as described by Gehrke et al. (33) with minor modifications. About 150 μg of tRNA in 25 μl of water was heated at 100°C for 2 min, cooled on ice, and then digested by incubation at 37°C for 4 h in a reaction mixture containing 0.65 mM ZnSO4, 6 units of P1 nuclease, and 0.16 mg/ml of potato phosphatase in a total volume of 62 μl. The mixture was heated at 100°C for 5 min and centrifuged (10,000 × g). The supernatant was diluted 7-fold with 170 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.9) and analyzed by RP-HPLC. Aliquots of the digested tRNA were loaded onto an analytical C18 HPLC column (Vydac, Hesperia, CA) and eluted with a linear gradient of 0–3.5% methanol in 10 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.3) for 0–25 min and that of 3.5–15% methanol for 25–35 min, followed by washing the column with 100% methanol. Nucleosides were detected by UV absorbance at 257 and 313 nm and liquid scintillation counting with Radioflow Detector LB508 (EG & G, Berthold, Bundoora, Australia).

Other Methods.

The FDHH activity was detected by the benzyl viologen agar overlay method (34). Proteins were assayed with a Bio-Rad protein assay kit, using BSA as a standard.

Results and Discussion

An iscS Mutant Strain Was Defective in the Biosynthesis of mnm5se2U in tRNAs.

It has been established that E. coli grown under anaerobic conditions in media supplemented with [75Se]selenite incorporates 75Se into the 79-kDa FDHH polypeptide and tRNA nucleosides (8, 16). To investigate whether mutant E. coli strains, which are unable to produce active CSD, CsdB, or IscS, can incorporate selenium into tRNAs, we analyzed extracts from each strain for the presence of 75Se-labeled tRNA by SDS/PAGE and PhosphorImager detection. Radioactive bands that migrated to positions expected for seleno-tRNAs were observed on 12% SDS/polyacrylamide gels for all strains except the iscS mutant (Fig. 2). To confirm that the radioactive bands were attributed to seleno-tRNA, RNaseA was added to the extracts from all strains. The 75Se-labeled bands corresponding to the seleno-tRNA disappeared because of degradation of tRNA by RNaseA (Fig. 2). These results show that the iscS mutant is unable to incorporate 75Se into the tRNA nucleosides and in this respect resembles the E. coli selD mutant strain MB08 (35). The selD− strain cannot produce FDHH or selenium-containing tRNAs because it is defective in the formation of monoselenophosphate. In contrast, the csdA and csdB mutations did not affect the incorporation pattern of 75Se into tRNAs (Fig. 2), indicating their lack of involvement in the formation of the selenium-containing tRNAs. The inability of the iscS− strain to form seleno-tRNA nucleosides also was confirmed by HPLC analysis. Bulk tRNA isolated from wild-type E. coli grown in the presence of [75Se]selenite was digested with P1 nuclease and phosphatase. The resulting nucleosides were resolved by RP-HPLC on a C18 column. The [75Se]mnm5se2U eluted with a retention time of 3.7 min (Fig. 3). However, no [75Se]mnm5se2U was detected in digests of bulk tRNA isolated from the iscS− strain. The previous work by Veres and Stadtman (36) indicated that the conversion of mnm5s2U in tRNAs to mnm5se2U requires selenophosphate and at least one protein termed tRNA 2-thiouridine synthase in Salmonella typhimurium. Therefore, it is possible that IscS is involved either in the conversion of mnm5s2U to mnm5se2U or the formation of the precursor mnm5s2U itself.

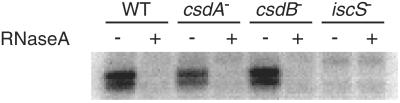

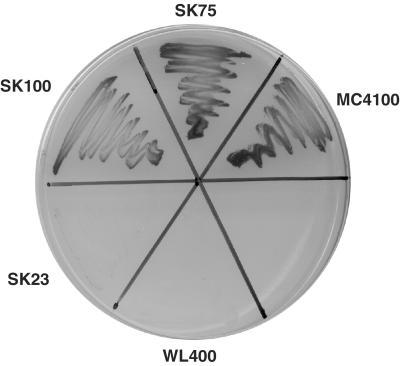

Figure 2.

Effect of csdA, csdB, and iscS deletions on the formation of 75Se-labeled tRNAs. Cell extracts from E. coli MC4100 (WT), SK75 (csdA−), SK100 (csdB−), and SK23 (iscS−), grown anaerobically in LB containing 0.1 μM Na2SeO3 and 20 μCi of Na275SeO3, were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and PhosphorImager detection. Lanes indicated by “+” denote samples treated with RNaseA (5 μg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h.

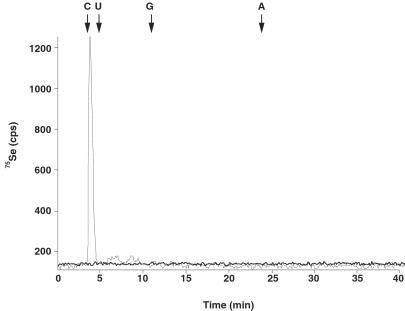

Figure 3.

HPLC analysis of nucleosides from 75Se-labeled bulk tRNA form E. coli MC4100 (thin line) and SK23 (thick line). Elution positions of the four major nucleosides are indicated by arrows. tRNA labeled with 75Se was digested to nucleosides and analyzed by HPLC at a flow rate of 1 ml/min as described.

IscS Is Involved in the Biosynthesis of both mnm5s2U and s4U.

Bulk tRNA isolated from 35S-labeled cells was analyzed to determine whether the iscS deletion affects the biosynthesis of mnm5s2U. HPLC analysis of radiolabeled tRNA digests showed that two major 35S-labeled nucleosides corresponding to mnm5s2U that eluted at 8.3 min and s4U that eluted at 27.1 min were present in the wild-type, csdA−, csdB−, and selD− strains (Fig. 4), whereas the tRNA isolated from the iscS− strain contained neither [35S]mnm5s2U nor [35S]s4U. Analysis of bulk tRNA isolated from a strain containing an mnmA deletion (TH159) revealed the presence of only one 35S-labeled nucleoside, s4U (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that IscS acts as a sulfur donor for both s4U and mnm5s2U biosynthesis. The mnmA gene product is also needed for the formation of mnm5s2U probably for the 2-thiolation reaction on the unmodified uridine. It has been shown that the mnmE mutant contains s2U, indicating that this thiolation reaction does not require an initial modification in position 5 (37). Sullivan et al. (12) have shown that tRNA from an mnmA mutant contains mnm5U, and thus this modification at position 5 can occur without dependence on thiolation at the 2 position. The requirement of IscS and the mnmA gene product for 2-thiouridine biosynthesis suggests the process may be similar to the biosynthesis of s4U. In the formation of s4U, IscS removes sulfur from l-cysteine to generate an IscS-derived cysteine persulfide with transfer of sulfur from the cysteine persulfide to ThiI (27). A mechanism involving the participation of cysteine residues of ThiI has been proposed for the formation of s4U (38). The mnmA gene product contains several cysteine residues that are highly conserved among its putative homologs (H.M. and N.E., unpublished observation). It is likely that one or more cysteine residues are involved in the 2-thiolation reaction.

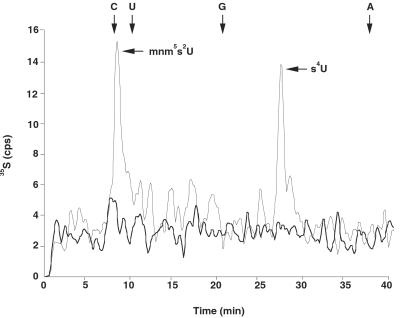

Figure 4.

HPLC analysis of nucleosides from 35S-labeled bulk tRNA from wild-type E. coli MC4100 (thin line) and mutant SK23 (thick line). Elution positions of the four major nucleosides are indicated by arrows. tRNA labeled with 35S was digested to nucleosides and analyzed by HPLC at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min as described.

It has been shown that mnm5s2U localized in the anticodon loop at position 34 of tRNAs is important for modulation of codon recognition during mRNA translation in E. coli (30, 39). 2-Thiouridine has also been found in eukaryotes (40, 41). The iscS and mnmA genes are ubiquitous and are found in genomic sequences of bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes (H.M. and N.E., unpublished observation). Recently, the defect in 2-thiolation in the wobble base of the human mitochondrial tRNALys anticodon was proposed to disturb codon–anticodon interaction, leading to the onset of a mitochondrial disease, myoclonus epilepsy associated with ragged-red fibers (42). Although little is known about the modification system in eukaryotes, our finding that IscS is essential for 2-thiolation of tRNA in the wobble position of the anticodon suggests that eukaryotic NifS homologs may function as sulfur-transfer proteins for 2-thiouridine biosynthesis.

IscS Is Indispensable for Formation of FDHH.

Monoselenophosphate formed by selenophosphate synthetase is the selenium donor required for specific selenocysteine incorporation in proteins and mnm5se2U. Because three NifS-like proteins from E. coli have the ability to generate a selenium substrate for selenophosphate biosynthesis (15), we examined whether an active selenocysteine-containing FDHH is produced in the E. coli NifS-like mutant strains. Active FDHH can be detected readily in vivo by the benzyl viologen agar overlay assay (34). Wild-type MC4100, csdA−, and csdB− strains reduced benzyl violgen, indicating that they are able to produce an active selenocysteine-containing FDHH, but the iscS− strain, like selD− strains, failed to reduce benzyl viologen (Fig. 5). From these results it is clear that the iscS gene product also is required for production of active FDHH.

Figure 5.

Effect of csdA, csdB, and iscS deletions on the FDHH activity. E. coli MC4100 (wild-type), SK75 (csdA−), SK100 (csdB−), SK23 (iscS−), and WL400 (selD−) were grown anaerobically at 37°C on an LB agar plate containing 0.5% glucose. After growth the plates were overlaid with a dye solution containing 0.75% agar, 1 mg/ml of benzyl viologen, 0.25 M sodium formate, and 25 mM KH2PO4.

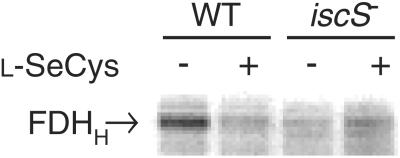

Effect of the iscS Mutation on the Incorporation of Selenocysteine into FDHH.

In addition to a selenocysteine residue, FDHH requires an Fe4S4 cluster and a Mo atom coordinated to two molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide cofactors for catalytic activity. Therefore, the loss of FDHH activity in the iscS− strain could be ascribed to failure of the mutant to incorporate selenocysteine into the enzyme, or to defective sulfur provision for iron-sulfur cluster formation, or for molybdopterin synthesis. We examined the incorporation of 75Se into FDHH in the iscS− strain. The crude extracts from wild-type and iscS− strains, prepared from cells grown with [75Se]selenite, were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and PhosphorImager detection. The extract from the wild-type strain exhibited a 79-kDa radioactive band corresponding to FDHH (Fig. 6). Addition of l-selenocysteine to the wild-type culture medium markedly depressed 75Se incorporation in FDHH, suggesting that selenium derived from l-selenocysteine also is used for its biosynthesis. In contrast to the result obtained with wild-type E. coli, the amount of 75Se-labeled FDHH observed in the extract of the iscS− strain was significantly reduced in the absence of l-selenocysteine (Fig. 6). The low amount of 75Se-labeled FDHH observed under these conditions may be the result of a lower level of expression of FDHH in this mutant. However, a slight increase in radioactivity is observed in extract from cells that were grown in the presence of l-selenocysteine. This increase may be the result of additional nonspecific incorporation of 75Se into FDHH. These results demonstrate that the synthesis of a selenocysteine-containing polypeptide of FDHH is affected by the deletion of the iscS gene. The inability of this mutant strain to effectively synthesize an active selenium-containing FDHH supports an in vivo role for IscS in selenium metabolism.

Figure 6.

Incorporation of 75Se into FDHH polypeptide in the MC4100 (WT) and SK23 (iscS−) strains in the presence (+) or absence (−) of added l-selenocysteine (0.2 μM). Cells were grown anaerobically in LB media containing 0.1 μM Na2SeO3 and 20 μCi of Na275SeO3 in the presence or absence of l-selenocysteine and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and PhosphorImager detection.

In summary, we show here that the iscS gene is essential for the formation of mnm5s2U and the selenocysteine-containing FDHH polypeptide. These results provide evidence for additional functions of IscS in sulfur and selenium metabolism.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Y. Yamamoto for kindly providing a pBEN66 vector, Dr. K. Hantke for giving us the H1489 strain, and Dr. T. Hagervall for kindly allowing us to use the TH159 strain. This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (B) 13125203 (to N.E.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 13480192 (to N.E.); and by Grants-in-Aid for Encouragement of Young Scientists 12780470 (to T.K.) and 13760069 (to H.M.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Abbreviations

- mnm5se2U

5-methylaminomethyl-2-selenouridine

- mnm5s2U

5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine

- s4U

4-thiouridine

- FDHH

formate dehydrogenase H

References

- 1.Heider J, Böck A. Adv Microbial Physiol. 1993;35:71–109. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stadtman T C. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1979;48:1–28. doi: 10.1002/9780470122938.ch1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stadtman T C. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:111–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veres Z, Kim I Y, Scholz T D, Stadtman T C. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10597–10603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuhierl B, Thanbichler M, Lottspeich F, Böck A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5407–5414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esaki N, Nakamura T, Tanaka H, Soda K. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:4386–4391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mihara H, Kurihara T, Watanabe T, Yoshimura T, Esaki N. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6195–6200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stadtman T C. FASEB J. 1987;1:375–379. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.1.5.2445614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zinoni F, Birkmann A, Stadtman T C, Böck A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4650–4654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forstrom J W, Zakowski J J, Tappel A L. Biochemistry. 1978;17:2639–2644. doi: 10.1021/bi00606a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wittwer A J, Tsai L, Ching W M, Stadtman T C. Biochemistry. 1984;23:4650–4655. doi: 10.1021/bi00315a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan M A, Cannon J F, Webb F H, Böck R M. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:368–376. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.1.368-376.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veres Z, Tsai L, Scholz T, Politino M, Balaban R, Stadtman T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2975–2979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glass R S, Singh W P, Jung W, Veres Z, Scholz T D, Stadtman T C. Biochemistry. 1993;32:12555–12559. doi: 10.1021/bi00210a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacourciere G M, Mihara H, Kurihara T, Esaki N, Stadtman T C. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23769–23773. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lacourciere G M. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1940–1946. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.7.1940-1946.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mihara H, Kurihara T, Yoshimura T, Esaki N. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2000;127:559–567. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mihara H, Maeda M, Fujii T, Kurihara T, Hata Y, Esaki N. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14768–14772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mihara H, Kurihara T, Yoshimura T, Soda K, Esaki N. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22417–22424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leimkuhler S, Rajagopalan K V. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22024–22031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patzer S I, Hantke K. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3307–3309. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3307-3309.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz C J, Djaman O, Imlay J A, Kiley P J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9009–9014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160261497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauhon C T, Kambampati R. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20096–20103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiyasu T, Asakura A, Nagahashi Y, Hoshino T. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2879–2885. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2879-2885.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kambampati R, Lauhon C T. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16561–16568. doi: 10.1021/bi991119r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tokumoto U, Takahashi Y. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2001;130:63–71. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kambampati R, Lauhon C T. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10727–10730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grosjean H, Nicoghosian K, Haumont E, Söll D, Cedergren R. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:5697–5706. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.15.5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka H, Soda K. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:240–243. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)43045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagervall T G, Pomerantz S C, McCloskey J A. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:33–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller J H. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Russell D W, editors. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3rd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gehrke C W, Kuo K C, McCune R A, Gerhardt K O, Agris P F. J Chromatogr. 1982;230:297–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandrand-Berthelot M-A, Wee M Y K, Haddock B A. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1978;4:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leinfelder W, Forchhammer K, Zinoni F, Sawers G, Mandrand-Berthelot M A, Böck A. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:540–546. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.540-546.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Veres Z, Stadtman T C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8092–8096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hagervall T G, Edmonds C G, McCloskey J A, Björk G R. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:8488–8495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mueller E G, Palenchar P M, Buck C J. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33588–33595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104067200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urbonavicius J, Qian Q, Durand J M, Hagervall T G, Björk G R. EMBO J. 2001;20:4863–4873. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White B N. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;395:322–328. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(75)90203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sen G C, Ghosh H P. Nucleic Acids Res. 1976;3:523–535. doi: 10.1093/nar/3.3.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yasukawa T, Suzuki T, Ishii N, Ohta S, Watanabe K. EMBO J. 2001;20:4794–4802. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]