Highlights

-

•

Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus was first detected in 2012 in Saudi Arabia.

-

•

Since 2012, Middle East respiratory syndrome caused 2626 confirmed cases.

-

•

20% of cases involve contact with dromedary camels or their products.

-

•

Human-to-human spread occurs, mainly in healthcare settings.

-

•

A case fatality rate is 36-40%.

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a viral respiratory disease caused by the MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and was first identified in 2012 [1,2]. The recently released MERS-CoV Dashboard, managed by the World Health Organization (WHO), provides a centralized visualization of confirmed human cases reported through the International Health Regulations (IHR) and WHO Disease Outbreak News (DON) [3]. By providing concise summary statistics and epidemiological trends, this tool improves situational awareness, aids in risk assessment, and guides public health responses.

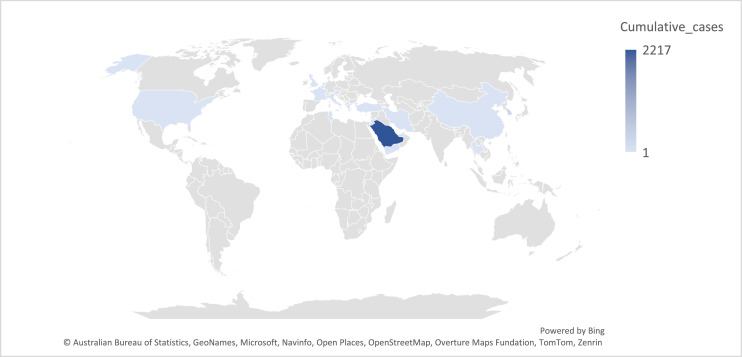

Since 2012, there have been 2626 laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV globally. The vast majority—over 90%—originated from the Arabian Peninsula, with Saudi Arabia alone accounting for approximately 2200 cases. Other countries with reported case counts include the Republic of Korea (186 cases) and the United Arab Emirates (94 cases). Sporadic cases were also reported from Jordan (28), Qatar (28), Oman (26), Iran (6), the United Kingdom (5), and several other countries [3] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative number of Middle East respiratory syndrome cases per country (Data were obtained from World Health Organization Middle East respiratory syndrome tracker [3]).

About 75% of newly discovered or emerging pathogens, including MERS-CoV, are zoonotic diseases. Multiple factors, the complex human-animal interactions, and intensified healthcare-associated transmissions explain why MERS-CoV persists. Around 20% of all reported cases have documented contact with dromedary camels or their products, highlighting the importance of animal-to-human transmission [4,5]. To avoid spillover and to remind global stakeholders of the realities of persistent zoonotic diseases, ongoing zoonotic risks should be investigated from a variety of angles [6]. Human-to-human transmission is also significant, particularly in healthcare settings where lapses in infection prevention and control can lead to outbreaks. Hospitals and other healthcare environments can act as amplifiers for the virus if proper measures are not maintained [7].

The demographic profile of MERS cases reveals that men comprise about 69% (1800 cases) of reported infections, while women account for 797 cases. The finding could be primarily due to differences in exposure risk rather than inherent biological susceptibility. Studies show the male-to-female ratio among confirmed MERS cases is roughly 2:1, with about 60%-67% of cases being male [[8], [9], [10]]. Behavioral and occupational factors are common in affected regions like Saudi Arabia, where men are more likely to have direct contact with camels—the main animal reservoir for MERS—or to engage in activities that increase their risk of acquiring the virus. For instance, men might participate more in camel farming, trading, or outdoor work that increases exposure.

The average age of patients infected with MERS-CoV is 52.4 years, with approximately 37% (958 cases) aged 60 years or older. Age-specific data indicate that the highest case numbers occur in adults aged 50-59 years (510 cases), followed by 40-49 years (440 cases) and 30-39 years (410 cases). In comparison, children are infrequently affected, with only 14 cases reported in the 0–4-year age group and 38 cases in the 5–17-year group. This age distribution carries important implications. The predominance of cases in middle-aged and older adults—especially those above 50—suggests increased susceptibility or higher risk of exposure in these demographics. Older individuals are also more prone to severe disease and worse clinical outcomes, factors that together increase the demand for hospital and intensive care resources.

The scarcity of cases in children (less than 2% in certain datasets) points toward possible age-related biological protection or reduced exposure patterns—such as less frequent contact with camels or healthcare settings, which are recognized sources of transmission [11,12]. Understanding these differences is key to shaping public health strategies, with a need to prioritize preventive measures, surveillance, and targeted health messaging. The age-related pattern should also guide planning for outbreak response, resource allocation, and the focus of vaccine and therapeutic development efforts.

Among all reported MERS-CoV cases, healthcare workers (HCWs) represent a substantial portion, accounting for 15% of total cases according to WHO data [3]. This reported proportion underscores the central role healthcare settings play in MERS transmission. HCWs often experience greater exposure due to close contact with infected patients, and outbreaks in healthcare facilities can amplify spread [13]. Compared to non-HCW cases, infected HCWs tend to be younger, more often female, and have fewer comorbidities, which corresponds with a generally higher survival rate and a higher frequency of asymptomatic infections among HCWs. The case fatality rate among HCWs is substantially lower than among non-HCWs, attributable to factors such as earlier detection and better baseline health [14].

Evidence indicates that asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic HCWs can carry and shed the virus, posing challenges for infection prevention and control (IPC), as their unnoticed infections may silently contribute to transmission chains in clinical settings. Hospital outbreaks have often been linked to delayed diagnosis, insufficient personal protective equipment use, and lapses in IPC protocols, emphasizing the need for rigorous protective measures to safeguard healthcare workers and prevent further nosocomial spread [6,7].

Given these findings, protecting HCWs is critical both for their safety and for maintaining continuity of care. Improved awareness, strict adherence to infection control recommendations, and early identification of cases among HCWs are vital to reducing healthcare-associated outbreaks [7,14,15]. The significant burden carried by HCWs, including psychological and workforce impacts, makes investment in their protection a public health priority in regions where MERS-CoV is endemic.

Most reported MERS-CoV cases are symptomatic—according to surveillance data, 2200 cases presented with symptoms, whereas 176 were asymptomatic and 273 had missing symptom status. The fact that a minority of cases are asymptomatic is a concern for transmission, since these individuals can shed virus without clinical signs, making containment and accurate estimation of disease burden more difficult [16,17]. The majority of symptomatic cases required hospitalization, with 865 admitted to intensive care units, which aligns with known severity patterns for MERS, though some asymptomatic and mild cases may not require admission.

The overall case fatality rate for MERS, as reported to WHO, is approximately 36%. However, this may overestimate the true mortality rate, as surveillance systems may miss mild or asymptomatic cases [18]. There are a limited number of randomized controlled trials for therapy, and no licensed vaccine for MERS, making prevention through infection control and surveillance crucial [19,20].

Future perspectives

Enhanced surveillance and rapid detection of MERS-CoV cases are critically important, especially in areas with frequent human–camel interactions, which are known spillover sources of the virus (Table 1). Modern surveillance systems increasingly adopt syndromic approaches that monitor early symptoms and health complaints before laboratory confirmation, enabling earlier warning signals for outbreaks [21]. For example, syndromic surveillance software integrates data from healthcare networks and public reports to detect unusual clusters rapidly, triggering timely epidemiological investigations [22]. This early-warning function supplements traditional surveillance, which often has time delays in confirming cases. Additionally, the One Health model—integrating human, animal, and environmental health data—is pivotal for proactive case identification [23].

Table 1.

Key future priorities for MERS-coronavirus control and research.

| Priority area | Description |

|---|---|

| Enhanced surveillance & detection | Investment in rapid diagnostics, strengthening surveillance (especially at human-animal interfaces), and adopting One Health approaches. |

| IPC | Improving healthcare worker training, enforce strict IPC protocols, and conducting regular audits to minimize nosocomial transmission. |

| Research & vaccine development | Accelerating vaccine and therapeutic research through international collaboration and clinical trials. |

| Public awareness & communication | Launching targeted education campaigns for high-risk groups (e.g., camel workers, healthcare staff) about prevention and early symptom recognition. |

| Global collaboration | Fostering international data sharing, harmonize outbreak response, and coordinate guidelines for controlling MERS and other emerging zoonoses. |

IPC, infection prevention and control; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome.

Laboratory diagnosis primarily utilizes lower respiratory tract specimens (such as sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage) for real-time polymerase chain reaction testing, alongside upper respiratory and serum samples when possible. Testing turnaround time and accessibility have improved with regional referral laboratories linked via electronic reporting systems. MERS case surveillance has become more systematic through structured data reporting networks such as the Health Electronic Surveillance Network (HESN) used in Saudi Arabia. Overall, strengthening these surveillance methods through technological innovation, healthcare worker training, and cross-sector collaboration will help expedite case detection, improve outbreak containment, and reduce transmission risks in humans.

In conclusion, MERS-CoV continues to pose a substantial threat, particularly in regions with close human-animal interfaces and in healthcare settings where infection control measures may be insufficient. The demographic skew toward older adults with comorbidities, the high case fatality rate, and the absence of targeted therapeutics or vaccines highlight the urgent need for sustained surveillance, research, and investment in preventive strategies. Lessons learned from MERS are also directly applicable to preparedness for other emerging zoonotic diseases, reinforcing the importance of a One Health approach to global health security.

Declarations of competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

Funding

None

Author contributions

JAT: Conceptuslization, writing and finalizing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ksiazek T.G., Erdman D., Goldsmith C.S., Zaki S.R., Peret T., Emery S., et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Dashboard 2025. 2025. https://data.who.int/dashboards/mers/cases [accessed 08 August 2025]

- 4.Müller M.A., Meyer B., Corman V.M., Al-Masri M., Turkestani A., Ritz D., et al. Presence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus antibodies in Saudi Arabia: a nationwide, cross-sectional, serological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:559–564. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70090-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan J.F.W., Lau S.K.P., To K.K.W., Cheng V.C.C., Woo P.C.Y., Yuen K-Y. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: another zoonotic betacoronavirus causing SARS-like disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:465–522. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00102-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish ZA. Recurrent MERS-CoV transmission in Saudi Arabia– renewed lessons in healthcare preparedness and surveillance. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2025;15:77. doi: 10.1007/s44197-025-00426-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Auwaerter PG. Healthcare-associated infections: the hallmark of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus with review of the literature. J Hosp Infect. 2019;101:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assiri A., McGeer A., Perl T.M., Price C.S., Al Rabeeah A.A., Cummings D.A.T., et al. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arabi Y.M., Arifi A.A., Balkhy H.H., Najm H., Aldawood A.S., Ghabashi A., et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:389–397. doi: 10.7326/M13-2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altamimi A., Abu-Saris R., El-Metwally A., Alaifan T., Alamri A. Demographic variations of MERS-CoV infection among suspected and confirmed cases: an epidemiological analysis of laboratory-based data from Riyadh regional laboratory. BioMed Res Int. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/9629747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Memish Z.A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Assiri A., Alrabiah F.A., Al Hajjar S.A., Albarrak A., et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:904–906. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Kattan R.F., Memish ZA. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease is rare in children: an update from Saudi Arabia. World J Clin Pediatr. 2016;5:391–396. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v5.i4.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amer H., Alqahtani A.S., Alaklobi F., Altayeb J., Memish ZA. Healthcare worker exposure to Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): revision of screening strategies urgently needed. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;71:113–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elkholy A.A., Grant R., Assiri A., Elhakim M., Malik M.R., Van Kerkhove MD. MERS-CoV infection among healthcare workers and risk factors for death: retrospective analysis of all laboratory-confirmed cases reported to WHO from 2012 to 2 June 2018. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:418–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Tawfiq J.A. Striving for zero traditional and non-traditional healthcare-associated infections (HAI): a target, vision, or philosophy. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2025;5:e146. doi: 10.1017/ash.2025.10031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Gautret P. Asymptomatic middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection: extent and implications for infection control: a systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2019;27:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Tawfiq J.A. Asymptomatic coronavirus infection: MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;35 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish ZA. An update on Middle East respiratory syndrome: 2 years later. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2015;9:327–335. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2015.1027689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Tawfiq J.A. Developments in treatment for middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Expert Rev Respir Med. 2024;18:295–307. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2024.2369714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Al Johani S., Memish Z.A. MERS-CoV remains a persistent threat amid global events. J Infect Public Health. 2024;17 doi: 10.1016/J.JIPH.2024.102487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saeed A.A.B., Abedi G.R., Alzahrani A.G., Salameh I., Abdirizak F., Alhakeem R., et al. Surveillance and testing for middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Saudi Arabia, april 2015–February 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:682–685. doi: 10.3201/eid2304.161793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salamatbakhsh M., Mobaraki K., Ahmadzadeh J. Syndromic surveillance system for MERS-CoV as new early warning and identification approach. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:93–95. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S239984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daly JM. Middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus: putting one health principles into practice? Vet J. 2017;222:52–53. doi: 10.1016/J.TVJL.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]