Abstract

Cytochrome P450 2W1 is an orphan P450 enzyme with little known about its endogenous ligands or function. It is expressed early in fetal colon but typically silenced in healthy adult tissues. Its reactivation in colorectal cancer has been explored to tissue specifically activate certain duocarmycin prodrugs. However, CYP1A1 in healthy tissues can also activate these prodrugs, exposing them to duocarmycins’ ultrapotent cytotoxicity. Therefore, this study aims to identify structural features of the CYP2W1 active site that may be exploited to design a duocarmycin prodrug more selectively activated by CYP2W1. Thus, the CYP2W1 ligand profile was investigated using multiple screens. In total, 694 inhibitors of CYP2W1-mediated metabolism were identified. Azoles are frequently nonspecific P450 inhibitors because they coordinate the catalytic heme iron. Screening a focused library of such compounds identified 67 binding CYP2W1. Most of these compounds could be used to generate a CYP2W1 pharmacophore, revealing one hydrophobic and two aromatic ring features consistent among these compounds. Furthermore, the placement of a hydrogen bond acceptor on either side of the azole ring differentiated those binding with high and low affinity. These physiochemical features and their relative arrangement within the CYP2W1 active site may inform the development of more selective duocarmycin prodrugs.

Keywords: cytochrome P450 2W1, active site, ligand binding, enzyme inhibition, high-throughput screening, pharmacophore

Human cytochrome P450 enzymes belong to a superfamily of membrane-bound, heme-containing monooxygenases. These enzymes are responsible for a variety of physiological functions including steroidogenesis and xenobiotic, vitamin, and fatty acid metabolism. However, several human cytochrome P450 enzymes do not have identified endogenous substrates and are thus designated as orphans. This includes cytochrome P450 2W1 (CYP2W1). Expression of proteins in certain tissues and during specific developmental stages can provide clues to the endogenous functions of such proteins. For CYP2W1 a putative role in intestinal development is suggested by a Cyp2w1 KO mouse with significantly shorter intestinal crypts than normal (1) and its presence in human fetal tissue up to about 18 weeks of gestation (2), beyond which it is typically silenced.

Although CYP2W1 is not normally present in healthy adult tissues, it is reactivated in a number of cancers (3, 4, 5, 6). CYP2W1 protein expression has been identified in 30% of colorectal cancers (4) and 50% of hepatocellular carcinomas (3). Colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma account for the third and sixth leading causes of cancer-related deaths in the United States respectively, highlighting a need for improved therapies (7). CYP2W1 protein expression has additionally been found in head and neck and breast cancer tissue but is less well studied in these contexts (5, 6). Furthermore, higher CYP2W1 protein expression is correlated with an overall worse cancer prognosis (3, 4) and higher rate of metastasis in colorectal cancers (8). However it is unclear if CYP2W1 plays an advantageous role for cancer cells with respect to their growth, metastasis, resistance to therapies, or other processes. Since CYP2W1 protein is selectively expressed in cancerous tissue and linked to poor prognosis, it has been investigated as a potential tool in cancer treatment.

Although the endogenous function of CYP2W1 is unknown, it can activate prodrugs derived from the duocarmycin class of natural products (9). Isolated from Streptomyces bacteria, duocarmycins have low picomolar cytotoxicity, far too potent to be used in their natural form (10), but they have been explored in the context of several targeted cancer strategies. For example, duocarmycins have been used as the cytotoxic payload in antibody-drug conjugates, where the antibody directs localization to tumor tissue (11). Because of its cancer-specific expression, employing CYP2W1 to activate pro-duocarmycins is another way to target some cancers. CYP2W1 does so (Fig. 1) by hydroxylating duocarmycin prodrugs at a specific position, enabling spontaneous spirocyclization (9). The resulting cyclopropyl ring on one half of the now-activated duocarmycin reacts to form an adducts with N3 of adenine, while DNA interaction is stabilized by van der Waals interactions with AT-rich regions in the minor groove (12). The ultimate outcome is apoptosis (13). In vitro, CYP2W1 activates multiple duocarmycin prodrug analogs. For example, ICT2700 and ICT2705 inhibit cell growth at IC50 values of 60 nM and 50 nM, respectively (Fig. 2A) (9). When mice with CYP2W1 protein expressing tumors were treated with pro-duocarmycin ICT-2706 (Fig. 2A), tumor weight was reduced by about 50%. In addition, CYP2W1 protein was depleted, suggesting cells expressing CYP2W1 protein were subject to the cytotoxic effects of activated ICT-2706 (14). Therefore, endogenous CYP2W1 has been validated as a tool for the activation of a duocarmycin prodrug in colorectal tumors in vivo.

Figure 1.

Activation of duocarmycin compounds by CYP2W1 and CYP1A1. Duocarmycin prodrugs, such as ICT2700, are activated via hydroxylation by CYP1A1 and CYP2W1. The compound then undergoes spontaneous spirocyclization to form a cyclopropane ring. After the methoxyindole subunit drives insertion at the minor groove, the cyclopropane ring on the other subunit attacks the adenine-N3 to form an adduct. The resulting covalent bond with DNA eventually leads to apoptosis. This figure is adapted with permission from Bart et al. (16).

Figure 2.

Known CYP2W1 substrates. Although the endogenous substrate of CYP2W1 is unknown, duocarmycin compounds such as ICT2700, ICT2705, ICT2706, and ICT 2726 have been identified as substrates (A). Additional compounds identified as poor CYP2W1 substrates include indole, 17β-estradiol, fatty acids, retinoic acid, retinol, AQ4N, GW 610, and two lysophosphatidylcholines (B).

However, CYP1A1 can also activate some duocarmycin prodrugs. Expressed in healthy adult tissues including bladder, gastrointestinal tract, and lung epithelia (15), pro-duocarmyin activation by CYP1A1 is undesirable. Therefore, to reduce off target activation in these tissues duocarmycin prodrugs need to be optimized so that they are specifically activated only by CYP2W1 and not CYP1A1.

Prior evaluation of a series of Institute for Cancer Therapeutics (ICT) pro-duocarmycin analogs, were successful in identifying chemical features resulting in better activation by CYP1A1 than CYP2W1, but not vice versa (9). CYP1A1 also exhibits higher binding affinity for ICT-2726, while CYP2W1 exhibits differential binding for (S)-ICT2726 (16). Together these studies suggest that there are differences between the CYP2W1 and CYP1A1 active sites that could be exploited to design more selective compounds. Although multiple structures of human CYP1A1 are available with various ligands—including pro-duocarmycins (16)—structural information is not available for the CYP2W1 active site, despite the attempts of multiple laboratories including our own.

In lieu of a structure, the CYP2W1 active site can be studied indirectly by identifying common chemical features of its ligands. Additional poor CYP2W1 substrates have been identified, including indole (17), 17β-estradiol (18), arachidonic acid (19), lysophosphatidylcholines (20), chlorzoxazone, and 3-methylindole (18), as well as retinoids such as all-trans retinoic acid and all-trans retinol (18) (Fig. 2B). Although several of these molecules have been implicated in embryonic development and tumorigenesis, their Km values for CYP2W1 are generally much higher than physiological concentrations, suggesting they are not likely to be significant endogenous substrates. CYP2W1 has also been reported to activate two other cancer therapies, AQ4N and GW-610 (Fig. 2B) (21, 22). Several of these CYP2W1 substrates are also metabolized by CYP1A1 or other human P450 enzymes, further highlighting the need to understand selectivity.

With a limited understanding of the physicochemical features that are compatible with CYP2W1 binding specifically, it is difficult to either propose potential endogenous substrates or design more selective pro-duocarmycins. Herein both broad and focused compound libraries were screened to identify additional ligands compatible with CYP2W1 binding. In lieu of a known endogenous substrate, a commercially available pro-luciferin substrate was identified and utilized for screening in a high-throughput manner. Second, a focused library of azoles was screened for interaction with the CYP2W1 active site heme iron. Although pharmacophores generated from general CYP2W1 inhibitors were less useful because of unknown orientations, pharmacophores generated from heme iron binding benefitted from an additional alignment restraint and were more useful to identify common chemical features. This pharmacophore identified one hydrophobic and two aromatic ring features, as well as a hydrogen bond acceptor whose placement distinguished compounds with high and low affinity. This improved understanding of CYP2W1 active site selection of ligand attributes is expected to assist in the design of duocarmycin prodrugs selective for CYP2W1 activation.

Results

Identification of a CYP2W1 substrate suitable for inhibitor screening

Identification of CYP2W1 inhibitors requires a substrate whose product can be readily evaluated in the presence of new compounds. A commercial luminescence assay is available to quickly evaluate P450 catalysis (P450-Glo, Promega). This assay employs various proluciferins modified to be somewhat selective substrates for individual P450s, focusing primarily on dominant ones in drug metabolism such as CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. In this assay, P450-mediated monooxygenation typically leads to dealkylation either to luciferin or a compound readily converted to luciferin. Beetle luciferase is then used to generate oxyluciferin, which is easily quantified using a plate reader as an indirect readout of P450 catalysis (Fig. S1).

Although none of the commercial proluciferin substrates were designed for or tested with CYP2W1, 12 of these compounds were initially screened as CYP2W1 substrates. To assess CYP2W1 activity, the luminescence of wells with increasing concentrations of each substrate was compared to that of control wells. Reaction wells were supplied with excess NADPH to initiate the reaction, while control wells were stopped prior to NADPH addition. After subtracting background luminescence from control wells, values from the reaction wells are converted to luciferin concentration using a standard curve and then to CYP2W1 activity (pmol luciferin/min/pmol CYP2W1). Signal to noise was calculated by comparing the raw luminescence of wells with the median substrate concentration to control wells. This initial screen identified eight of the 12 proluciferin compounds as CYP2W1 substrates using a cutoff of a signal to noise ratio >3 (Table S1, Fig. S2). CYP2W1-mediated metabolism of luciferin-1A2 and luciferin-2B6 exhibited the highest signal to noise ratios of 98 and 87, respectively. Notably, these two substrates contain an isonitrile group on the opposite end of the benzothiazole from the site of metabolism (Table S1). This isonitrile moiety is absent in the other proluciferin substrates examined and could play a role in their binding in the CYP2W1 active site.

Luciferin-1A2 was selected as a substrate for screening CYP2W1 inhibitors both because the signal-to-noise ratio was higher, and its concentration dependence exhibited a plateau at higher concentrations of substrate (Fig. S2A). This plateau could not be achieved with luciferin-2B6 as its concentration in the reaction wells was limited by the concentration of the vendor stock (Fig. S2B). To maximize the dynamic range of luminescence and thus the ability to measure inhibition, the assay was further improved by optimizing the concentration of CYP2W1, the ratio of CYP2W1 to cytochrome P450 reductase, reaction time, and temperature. Under the optimized conditions reported in methods, the CYP2W1 Km of luciferin-1A2 was 19.6 μM (95% confidence interval (CI) 15.6–24.8 μM) and the kcat was 3.43 × 10−5 min−1 (95% CI 3.14 × 10−5–3.79 × 10−5 min−1) (Fig. S3).

Initial assay validation and low-throughput identification of CYP2W1 inhibitors

To initially validate the utility of the above assay for identifying CYP2W1 inhibitors, the luciferin-1A2 substrate was used to manually screen a limited set of likely compounds. Compounds for this initial CYP2W1 inhibition screen were selected from three categories (1): known CYP1A1 ligands (2), known P450 family 2 ligands, and (3) azoles (Table S2). CYP1A1 substrates were selected because CYP1A1 and CYP2W1 have some common substrates including ICT compounds. These compounds included erlotinib, α-naphthoflavone, bergamottin, amiodarone, and ponatinib (23). Selected P450 family 2 ligands were screened because CYP2W1 is most closely related to other P450 enzymes in this family. This subset included CYP2F1 substrates 3-methylindole, styrene, and naphthalene (24); CYP2D6 substrates dextromethorphan, prinomastat, and imatinib (25); CYP2D6 inhibitors quinidine and quinine; CYP2A6 substrates coumarin and indole (26); CYP2E1 substrates acetaminophen and chlorzoxazone; the CYP2J2 substrate arachidonic acid, and reported CYP2W1 substrates GW610 and AQ4N. Finally, azoles are frequently pan-P450 inhibitors as they can coordinate to the active site heme iron, so selected imidazole and triazole compounds were also evaluated. This set included itraconazole, oxiconazole, econazole, liarozole, fadrozole, clotrimazole, miconazole, tioconazole, ketoconazole, posaconazole, fluconazole, imidazole, indazole, fenticonazole, butoconazole, enilconazole, sulconazole, elubiol, and (1S)-1-(2,4 dichlorophenyl)-2-imidazol-1-ylethanol. In total, 39 compounds were evaluated for their ability to inhibit CYP2W1-mediated luciferase-1A2 metabolism (Table S2).

This inhibition assay was performed manually in 96-well plates, using a plate reader to quantify luminescence. To determine if significant inhibition of CYP2W1 was observed, each compound was initially screened at both high and low concentrations (typically 0.5 and 10 μM) in duplicate on two different days (n = 4). Luminescence was converted to specific activity using a standard curve. Control wells containing no inhibitor exhibited high luminescence and were used to represent 100% CYP2W1 activity. The specific activity of wells containing potential inhibitors was compared to that of these control wells and the results reported as fractional activity, defined as:

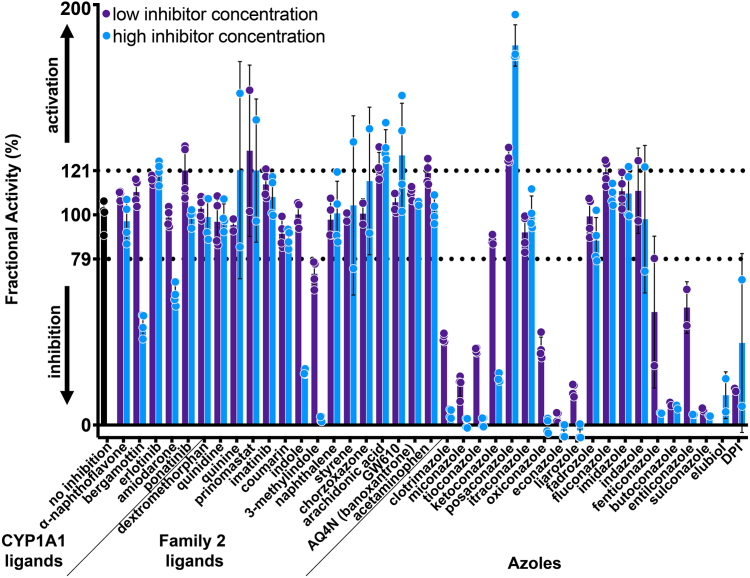

(Table S2). Compounds reducing CYP2W1-mediated metabolism by more than three standard deviations from controls (i.e. reduced by >21%) were considered inhibitors.

Of the 39 compounds evaluated, 17 or 44% met this inhibition criterion (<79% remaining activity compared to controls, Fig. 3). These included CYP1A1 substrates bergamottin and amiodarone, the CYP2A6 substrate indole, the CYP2F1 substrate 3-methylindole, and 13 azoles. The azoles resulting in significant inhibition with 10 μM compound or less included clotrimazole, miconazole, tioconazole, ketoconazole, oxiconazole, econazole, sulconazole, enilconazole, butoconazole, (1S)-1-(2,4 dichlorophenyl)-2-imidazol-1-ylethanol, elubiol, fenticonazole and liarozole. Unexpectedly, six compounds appeared to increase CYP2W1 activity to >121%. These include GW-610, ponatinib, quinine, prinomastat, posaconazole, and arachidonic acid. As it is unclear why these compounds would increase CYP2W1 activity, they were set aside for the purpose of probing the CYP2W1 active site.

Figure 3.

Low-throughput screen of CYP2W1 inhibitors. CYP1A1 ligands, family 2 ligands, and azoles were selected to test a total of 39 compounds for CYP2W1 inhibition. Each compound was tested at a low concentration (blue, n = 4) and high concentration (purple, n = 4) and the substrate luciferin-1A2 was added at 18.5 μM. Most compounds were tested at 0.5 μM and 10 μM, but those tested at higher concentrations are noted in Table S3. Fractional activity and standard deviation are shown for each compound. Compounds are considered hits if fractional activity is greater than three standard deviations of the no inhibition control (black). This indicates that compounds resulting in activity higher than 121% fractional activity are activators, and those resulting in activity lower than 79% are inhibitors (dotted lines).

These newly identified CYP2W1 inhibitors were then further evaluated using a range of concentrations to determine IC50 values. Bergamottin and amiodarone could not be further characterized due to issues with solubility, but the remaining 15 compounds were evaluated at 20 inhibitor concentrations with two to six replicates in 96-well plates (global comparison in Fig. 4, individual results in Fig. S4). The resulting IC50 values ranged from a low of 111 nM for fenticonazole to a high of 3.37 μM for ketoconazole (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Range of inhibition identified in CYP2W1-mediated luciferin-1A2 metabolism assays. Fifteen inhibitors were evaluated for inhibition of CYP2W1-mediated metabolism of 18.5 μM luciferin-1A2. Fractional activity of CYP2W1 was calculated with increasing concentrations of each inhibitor, and IC50 values were determined using the nonlinear regression four parameter [inhibitor] versus response with between two and six replicates as indicated in Table 1. These curves result in a range of IC50 values from 111 nM to 3.37 μM inhibitor. Compounds are roughly categorized as those with IC50 values below 200 nM compound (green), IC50 values between 200 nM and 1 μM compound (blue), and IC50 values over 1 μM compound (purple).

Table 1.

Inhibitors identified in the CYP2W1 luminescence screen

| Inhibitor (molecular Mass) replicates | IC50 (95% CI) (nM) |

Structure |

|---|---|---|

| <200 nM | ||

| Fenticonazole (455.5 g/mol) n = 2 |

111 (81.9–148) |

|

| Econazole (381.7 g/mol) n = 4 |

137 (129–145) |

|

| Miconazole (416.1 g/mol) n = 4 |

139 (126–151) |

|

| Sulconazole (397.7 g/mol) n = 2 |

148 (140–155) |

|

| Butoconazole (411.8 g/mol) n = 2 |

159 (143–178) |

|

| Tioconazole (387.7 g/mol) n = 4 |

170 (148–191) |

|

| <1 μM | ||

|---|---|---|

| Liarozole (308.8 g/mol) n = 4 |

221 (190–259) |

|

| Enilconazole (297.2 g/mol) n = 2 |

221 (186–263) |

|

| Oxiconazole (429.1 g/mol) n = 4 |

227 (196–258) |

|

| (1S)-1-(2,4 dichlorophenyl)-2-imidazol-1-ylethanol (257.1 g/mol) n = 2 |

243 (216–274) |

|

| Clotrimazole (344.8 g/mol) n = 4 |

274 (247–302) |

|

| Elubiol (561.5 g/mol) n = 2 |

445 (343–577) |

|

| >1 μM | ||

|---|---|---|

| 3-methylindole (131.2 g/mol) n = 4 |

1320 (1160–1490) |

|

| Indole (117.2 g/mol) n = 6 |

2660 (2070–3490) |

|

| Ketoconazole (531.4 g/mol) n = 2 |

3370 (2440–5030) |

|

Inhibitors identified in the initial inhibition screen and characterized for inhibition are listed below in order of increasing IC50 values. Common features in compounds with IC50 values less than 200 nM are annotated such that the azole ring is highlighted by a double circle, sp3 hybridized carbons by a filled oval, hydrogen bond acceptor in gray circle, and dichlorophenyl ring in a black open oval. Inhibition curves are found in Fig. S4.

These inhibitors can generally be divided into three categories: those with IC50 values <200 nM, between 200 nM and 1 μM, and >1 μM. All compounds with IC50 values <200 nM have similar overall structures. They ranged from 381 to 455 g/mol in molecular mass and each contained an imidazole group (Table 1, double gray open circle) connected to two sp3 hybridized carbons (Table 1, gray filled oval), as well as a hydrogen bond acceptor (Table 1, gray open circle) 4.5 to 5.5 Å away from the imidazole nitrogen lone pair. All compounds in this group contain at least three aromatic rings, one of which is a dichlorophenyl ring (Table 1, black open oval) also attached to the second sp3 hybridized carbon from the imidazole ring. Compounds exhibiting IC50 values between 200 nM and 1 μM also included azoles, but not all contained three or more aromatic rings or a dichlorophenyl ring. These compounds ranged from 257 to 561 g/mol in mass. Finally, the three compounds that exhibited IC50 values >1 mM include one larger azole (ketoconazole at 531 g/mol) and two compounds lacking an imidazole ring. These weakly inhibiting compounds exhibited the largest range of molecular weight from 117 to 531 g/mol. It is of note that although elubiol and ketoconazole contain very similar structures differing only by an ethoxy group, the corresponding IC50 values are more than 7-fold different. Ketoconazole inhibited CYP2W1 activity with an IC50 value of 3370 μM, while elubiol inhibited CYP2W1 with an IC50 value of 445 μM. This suggests that the ethoxy group of elubiol may play a role in stabilizing the compound in the CYP2W1 active site, allowing for greater inhibition of CYP2W1 activity. This initial data both identified novel CYP2W1 inhibitions and validated the utility of this assay for higher-throughput screening.

Identification of CYP2W1 inhibitors employing an automated high-throughput screen

To develop a more robust dataset enabling stronger conclusions about common structural features of CYP2W1 inhibitors, the luminescence assay was then adapted as a high-throughput screen using automation and 384-well plates. Preliminary validation of CYP2W1-mediated luciferin-1A2 metabolism in 384 well plates without inhibitors included even higher substrate concentrations, and some substrate inhibition was observed >100 μM. Fitting with the appropriate substrate inhibition equation (GraphPad Prism) yielded a Km of 43.0 μM (95% CI 31.7–61.2 μM) and a kcat of 5.41 × 10-5 min-1 (95% CI 4.48 × 10−5–6.89 × 10−5 min−1) (Fig. 5), both of which are slightly higher than those observed in the 96-well assay (Fig. S3). The Z′ score for this assay was 0.62, indicating its ability to detect statistically significant inhibition.

Figure 5.

CYP2W1-mediated luciferin-1A2 metabolism in the high-throughput luminescence assay. The velocity of CYP2W1 turnover of luciferin-1A2 was measured using the high-throughput luminescence assay optimized for 384 well plates. The Michaelis constant (Km) and turnover (kcat) values were determined using nonlinear regression for the substrate inhibition equation as employed in GraphPad Prism. Confidence intervals (95%) provided in parentheses.

Using this 384-well version of the assay, nearly 6000 compounds were screened as potential CYP2W1 inhibitors. These compounds originated from three libraries owned by the Center for Chemical Genomics at the University of Michigan: Drug Repurposing Set, LOPAC1280, and the Prestwick library. The Drug Repurposing Set includes a curated set of Food and Drug Administration-approved compounds. The commercially available LOPAC1280 library from MilliporeSigma contains pharmacologically active compounds beyond those approved for clinical use. The Prestwick library contains a set of small molecules most of which are approved by agencies such as the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency. Since both the Drug Repurposing Set and Prestwick library are growing libraries, compounds tested in this assay are explicitly reported in Table S3. These libraries were selected for screening because CYP2W1 belongs to family 2 P450 enzymes, which are well-known for their role in drug metabolism. Therefore it was thought that drug-focused screens would yield a larger number of compounds to expand the CYP2W1 ligand profile. Although the goal for many high-throughput screens is to yield a select few hits and optimize those for interaction with the specific target, the goal for this screen was to identify many compounds to expand the CYP2W1 ligand profile and thus support the identification of common features important for interaction with CYP2W1.

Screening of the above compounds proceeded in stages as summarized in Figure 6. In the initial stage or primary screen, all 5957 compounds from the three libraries were evaluated with one replicate at 10 μM in 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide. As described previously, the standard deviation of signal for control wells with no inhibitor was determined, and compounds were identified as inhibitors if their signal was decreased more than three times this value. Of these 5957 compounds, 979 or 16% were identified as potential CYP2W1 inhibitors. Assays with only these 979 compounds were then repeated twice more as a confirmation screen. This reduced the total to 704 inhibitors using the same criteria, for an overall hit rate of 12%. Because a coupled assay was being employed, a counter screen was then used to exclude any of these compounds inhibiting luciferase itself, which would also appear as a hit. The counter screen identified 10 luciferase inhibitors, which were excluded from further analysis.

Figure 6.

Overview of high-throughput CYP2W1 inhibition assay. The high-throughput CYP2W1 inhibition assay tested compounds from three libraries for a total of 5957 compounds. Primary screening identified 979 hits, and 704 of those hits were confirmed with three total replicates. A counter screen identified 10 compounds as inhibitors of luciferase, leaving 694 inhibitors of CYP2W1. Finally, a second counter screen identified 123 compounds as CYP2W1 binders. These 123 compounds were used to generate a pharmacophore model for the CYP2W1 active site.

The remaining 694 compounds that resulted in inhibition of CYP2W1-mediated metabolism exhibited chemical diversity. Compounds were as small as urethane at 89.1 g/mol and large as tannic acid at 1701.2 g/mol. Some compounds identified have previously been reported as CYP2W1 ligands such as indole and a number of azole compounds. Inhibitors also included estradiol, which is closely related to 17β-estradiol, a known substrate of CYP2W1. New CYP2W1 inhibitors identified include cancer drugs such as apatinib for gastrointestinal cancers, epirubicin and fulvestrant for breast cancer, tipifarnib investigated for a variety of cancers, and idarubicin and venetoclax for leukemia. It has been proposed that CYP2W1 may play a role in therapeutic resistance of some cancers, so further investigation into the ability of CYP2W1 to metabolize these compounds in vivo would be of interest. The inhibition screen additionally identified the known CYP1A1 ligand, amiodarone, as a CYP2W1 inhibitor. Furthermore, multiple family 2 substrates and inhibitors were identified including CYP2D6 substrates, fluvoxamine (27), (R)-duloxetine (28), and carvedilol (29), and the CYP2C8 inhibitor, montelukast (30). Finally, quite a few azoles, which are often pan-P450 inhibitors, were also identified as CYP2W1 inhibitors.

Best practice is to confirm the identity of inhibitors from screening libraries by purchasing fresh compound. Although this was not feasible for the remaining 694 hits, 10 compounds from the initial, freshly prepared 96-well low-throughput screen were identified as CYP2W1 inhibitors again in the high-throughput assay, serving as an internal validation of the high-throughput screen. These included fenticonazole, econazole, miconazole, sulconazole, butoconazole, tioconazole, oxiconazole, clotrimazole, elubiol, and ketoconazole.

Identification of CYP2W1 inhibitors likely binding in the active site

Compounds identified using an inhibition screen may bind either competitively in the active site or elsewhere on the protein. Since the goal of this study is to identify physiochemical features compatible with the CYP2W1 active site, a final counter screen was used to identify which inhibitors bind in this location. Binding of molecules within a P450 active site were monitored via changes in UV-visible absorbance of the heme Soret peak. A blue/type I shift is common for ligands that enter the active site and displace a water molecule that is otherwise usually coordinated to the heme iron. In contrast, nitrogenous compounds replacing this water molecule cause a red/type II shift. A high-throughput version of this binding assay (31) was used to identify such compounds, which are likely binding in the CYP2W1 active site.

Thus the 694 CYP2W1 inhibitors identified in the high-throughput screen were evaluated using this spectral shift binding assay. Results could not be determined for 285 compounds, primarily due to high interfering ligand absorbance, and these compounds were eliminated from further analysis. Of the remaining 409 compounds that could be reliably evaluated, no spectral changes were observed for 286 or 70% of these compounds. This result is consistent with either allosteric inhibition or binding in the active site, not close enough to affect the iron and cause a spectral shift. The latter occurs for some validated P450 substrates (32, 33). However the remaining 123 or 30% resulted in a spectral shift, with 10 causing a blue shift and 113 causing a red shift. Interestingly, while 17β-estradiol has been reported as a CYP2W1 substrate (13) and would be predicted to yield a blue shift, six estradiol analogs identified as CYP2W1 inhibitors in the high-throughput inhibition screen, but did not cause a spectral shift.

The 123 inhibitory compounds that also resulted in a spectral shift show chemical diversity as described below (Table S3).

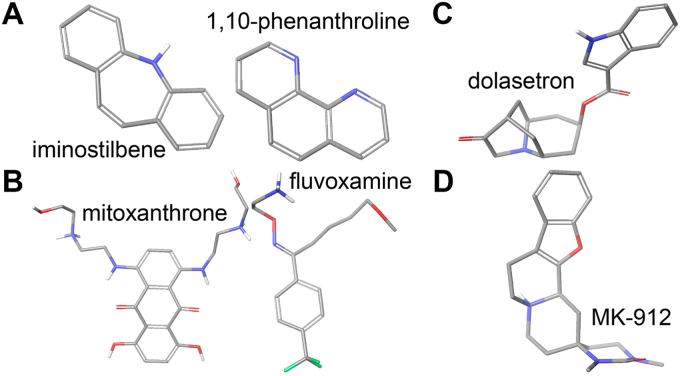

-

•

Some compounds contain planar fused ring systems such as iminostilbene and 1,10-phenanthroline (Fig. 7A).

-

•

Three compounds contained an indole moiety, a known substrate of CYP2W1.

-

•

Eleven compounds contained an imidazole group, a known heme-coordinating element.

-

•

A few compounds contain short flexible chains as seen with mitoxanthrone and fluvoxamine. These chains are not as long as those in the fatty acids metabolized by CYP2W1 but are consistent with the idea that CYP2W1 is able to accommodate ligands with some flexibility (Fig. 7B).

-

•

One compound, dolasetron, contains a bridged ring, which is a more restricted three-dimensional structure of about 11 Å3 in volume (Fig. 7C).

-

•

One compound, MK-912, induces a type I spectral shift and takes on an L shape about 11 Å across (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

Selected CYP2W1 inhibitors and binders in three dimensions. Selected CYP2W1 inhibitors were screened for binding in the active site. Hits showed chemical diversity including planar molecules such as iminostilbene and 1,10-phenanthroline (A), molecules with flexible moieties such as mitoxanthrone and fluvoxamine (B), compounds with bicyclic rings such as dolasetron (C), and L-shaped molecules such as MK-912 (D). Flexible compounds are shown in their lowest energy confomer.

Identification of additional azole binders for CYP2W1

Inhibitors identified from screening large, drug-based libraries are useful for examining a set of ligands with large chemical diversity, but unless they cause a type II spectral shift, their orientation in the active site—and thus to each other—is unknown. This can make determination of a pharmacophore less reliable. As an orthogonal approach, an additional focused library of azole-containing compounds was also screened for CYP2W1 binding. Azoles that cause a red/type II shift do so because the azole nitrogen coordinates directly to the heme iron, thus providing a known relative orientation between ligand and heme, and by extension, between two such azole compounds. This additional alignment parameter was proposed to improve compound alignment during pharmacophore generation and thus improve the identification of similar features among CYP2W1 active site ligands.

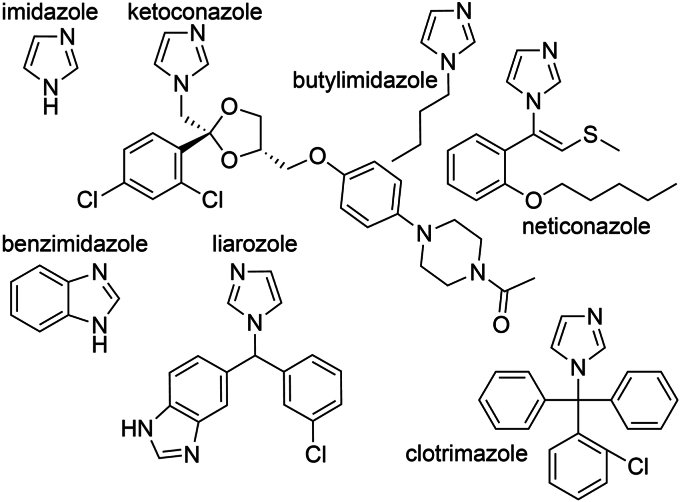

The focused library containing 104 azoles (Table S4) was initially screened to identify CYP2W1 spectral shifts over six compound concentrations between about 1 μM and 600 μM, with the specific concentration range adapted depending on the azole’s inherent absorbance between 350 nm and 500 nm where the Soret peak spectral shift is observed. Of 104 compounds, 67 or 64% resulted in a red/type II spectral shift. These compounds were then further evaluated at a concentration range tailored to each compound as suggested from the initial concentrations to generate a well-defined binding curve up to saturation, which could then be used to determine dissociation constants (Kd values).

This focused azole binding screen identified 67 azoles as CYP2W1 binders, many of which have not been studied previously (Table S4). Dissociation constants for these compounds ranged over two orders of magnitude from <1 μM to 175 μM, consistent with a broad range of affinities (Fig. S5). These compounds also represent a fair amount of chemical diversity. Ligand sizes were as small as imidazole at 68.1 g/mol to as large as posaconazole at 701 g/mol (Fig. 8). The structure of ketoconazole extends 15 Å beyond its imidazole, consistent with a large and/or flexible or relatively open CYP2W1 active site. Similar to some of the inhibition hits, a few compounds contain flexible carbon chains such as those of 1-butylimidazole and neticonazole. Some ligands like benzimidazole contain fused rings and are planar, similar to many CYP1A1 substrates. However others are much broader in the third dimension such as liarozole and clotrimazole.

Figure 8.

CYP2W1 active site binders are chemically diverse. CYP2W1 binders include small compounds like imidazole to large compounds like ketoconazole. Examples also include planar (benzimidazole) and pyramidal compounds (clotrimazole) and compounds with short flexible carbon chains (butylimidazole and neticonazole).

Discussion

A CYP2W1 pharmacophore from inhibitors that cause a spectral shift

Although general observations of inhibitor physicochemical features can be somewhat useful in exploring overlap between P450 enzymes, a pharmacophore more systematically interpret the results to identify common structural elements. This initial pharmacophore was generated by classifying the 123 inhibitors that also caused a spectral shift as active and the 286 that did not cause a spectral shift as inactive. Many compounds had rotatable bonds so multiple conformations were considered, resulting in 291 active and 364 inactive conformers.

The resulting pharmacophore (Fig. 9) identified six features frequently shared by the active compounds. These included three hydrogen bond acceptors, two aromatic rings, and one hydrophobic feature (Fig. 9A). These features appear are aligned in a single plane (Fig. 9B). Some compounds approximate this model fairly well. For example, enilconazole (Fig. 9, purple), contains an azole ring positioned between the two aromatic ring features, an sp3 hybridized carbon at the hydrophobic feature, and nitrogens or oxygens at the positions of the hydrogen bond acceptors. Similarly, ciproxifan (Fig. 9, gray) exhibits a phenylene group near the aromatic ring features and two oxygens overlapping with two of the hydrogen bond accepting features. However, both enilconazole and ciproxifan exhibit type II shifts with CYP2W1. This means that their nitrogen lone pair (Fig. 9A, red dashed circles) must each coordinate to the heme iron. The pharmacophore model does not correctly account for this as the two imidazole rings do not overlay. Furthermore, if one considers the required placement of the heme plane (Fig. 9A, black dashed line) for enilconazole (Fig. 9, purple) iron ligation, then the model predicts ciproxifan crosses that plane, which would not be physically possible. This brings into question the physiological relevance of the pharmacophore as the software is not correctly accounting for the known orientation of certain compounds. To resolve this discrepancy, pharmacophores were generated with compounds that only bound in a known orientation.

Figure 9.

CYP2W1 pharmacophore modeling from high-throughput inhibition screening. The 123 inhibitors that also caused a spectral shift were used to generate a pharmacophore. A, this resulted in six identified features: three hydrogen bond accepting features (pink sphere), two aromatic features (orange ring), and one hydrophobic group (green sphere). This model is fit by both enilconazole (purple) and ciproxifan (gray). The black dotted line represents the plane of the heme prosthetic group in the event of enilconazole binding. The nitrogen that coordinates to the heme iron for both enilconazole and ciproxifan are identified (red ring). B, when the model is rotated 90˚ toward the viewer, it is clear the features are stacked on top of one another.

CYP2W1 pharmacophores from azole binding screen

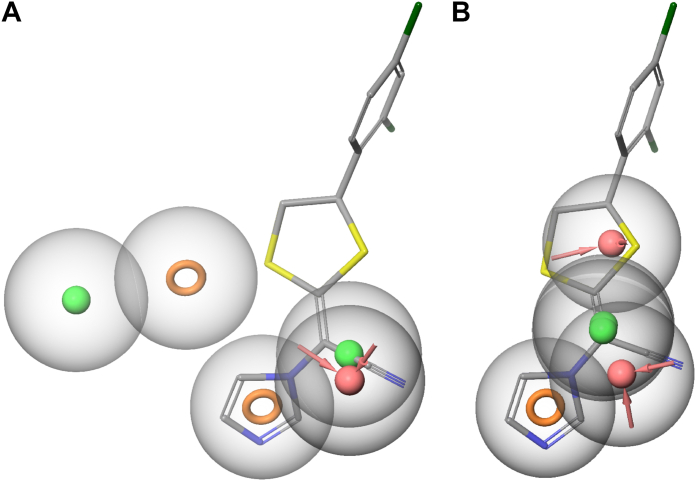

Compounds from the azole screen that resulted in a type II spectral shift were used to generate pharmacophores to identify likely ligand-protein interactions in the CYP2W1 active site. Compounds that induce a type II spectral shift are oriented such that a lone pair on a nitrogen molecule is coordinated to the heme iron and are thus inhibitors, but additionally these nitrogens can be used to align for each compound before a pharmacophore is generated. This additional constraint was expected to increase the accuracy of the pharmacophore. To evaluate physicochemical features that might distinguish high-affinity versus low-affinity compounds, two pharmacophores were generated using different dissociation constant cutoffs to define active versus inactive compounds.

The first pharmacophore defined all compounds with dissociation constants less than 3 μM as active. This resulted in 38 active compounds in 70 total conformations, and 59 inactive compounds in 82 conformations. Because this model relies on the proper overlay of the heme-coordinating nitrogen, four compounds that were not appropriately oriented were excluded from the model. In addition to the imidazole common to all compounds, this pharmacophore identified an additional aromatic ring feature, two hydrophobic features, and one hydrogen bond acceptor. The best fit to this profile is tioconazole (Fig. 10, A and B). Directly above the imidazole ring, many compounds have an sp3 hybridized carbon, again exhibited by tioconazole. An oxygen stacked above the sp3 hybridized carbon is identified as the hydrogen bond acceptor. Finally, the second aromatic ring and hydrophobic feature are well modeled by the dichlorophenyl ring of tioconazole.

Figure 10.

CYP2W1 pharmacophore modeling from azole screen. The results of the high throughput binding screen were used to generate two pharmacophore models. The first model was designed with all active ligands exhibiting a dissociation constant of less than or equal to 3 μM compound (A and B). This pharmacophore highlights two aromatic rings (orange ring), two hydrophobic groups (green sphere), and one hydrogen bond acceptor (pink sphere) with tioconazole modeling the appropriate features. When the model is rotated 90˚ toward the viewer, it is clear the hydrogen bond acceptor is positioned behind the aromatic rings. The second model was designed with all active ligands exhibiting a spectral shift (C and D) This model is best fit by 1-[4-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-hydroxylbutyl]imidazole. When the model is rotated 90˚ toward the viewer, it is clear the hydrogen bond acceptor is positioned in front of the aromatic rings.

A second pharmacophore was then generated defining all compounds causing a spectral shift as active, regardless of their dissociation constant. This resulted the inclusion of 22 additional compounds for a total of 60 active compounds (in 92 total conformations, and 37 inactive compounds in 52 conformations. Three additional CYP2W1 binders could not be aligned correctly and were excluded from the model. The features of this pharmacophore (Fig. 10, C and D) are very similar to the first pharmacophore above (Fig. 10, A and B). This pharmacophore is best fit by 1-[4-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-hydroxylbutyl]imidazole.

Comparison of the two pharmacophores generated from azoles reveals several interesting features. Although the primary aromatic and hydrophobic elements agree well, a difference is the relative position of the hydrogen bond acceptor to the azole ring. When both pharmacophores are rotated by 90˚ such that one is viewing the molecule in the plane of the imidazole group, it is clear that while the other elements are still very similarly positioned, the hydrogen bond accepting feature is positioned on opposite sides of the imidazole group plane (Fig. 10B versus D). The pharmacophore produced from the tighter binding compounds positions the hydrogen bond acceptor behind the plane of the imidazole group, while the pharmacophore generated from all binding azoles positions the hydrogen bond acceptor in front of the azole group. Thus, not only does this approach reveal conserved features consistent with binding in the CYP2W1 active, but the two pharmacophores suggest one structural difference modulating affinity.

The quality of these pharmacophores can be evaluated by comparing them to the structure of azoles identified in the high-throughput inhibition and binding screens. Luliconazole was identified herein as both a CYP2W1 inhibitor and type II binder but was not part of the focused azole library used to generate the pharmacophores in Figure 10. When the structure of luliconazole is compared to the pharmacophore generated by declaring all compounds with spectral shifts as active, one half of the model quite well (Fig. 11A). As expected, the imidazole ring overlays one aromatic ring feature. A carbon overlays the adjacent hydrophobic feature while the isonitrile group is positioned at the edge of the hydrogen bond acceptor feature. Luliconazole does not contain features that overlay the second aromatic ring or second hydrophobic feature of the pharmacophore.

Figure 11.

Comprehensive CYP2W1 pharmacophore modeling from all azoles and assessment. Luliconazole was identified as a binder in the high-throughput inhibition assay and compared to the pharmacophore generated from compounds in the high throughput binding screen (A). Luliconazole contains an imidazole ring near the aromatic ring feature (orange ring), carbon near the hydrophobic feature (green sphere), and isonitrile group near the hydrogen bond acceptor (pink sphere). Azoles identified in the inhibition assay were combined with azoles from the high throughput binding screen to generate another pharmacophore (B). This pharmacophore contains an aromatic ring near the imidazole ring of each compound, two hydrogen bond acceptors, and one hydrophobic feature.

CYP2W1 pharmacophore from all azoles binding CYP2W1 active site heme

A final pharmacophore was designed using all azoles binding the CYP2W1 heme iron. This included both those identified as coordinating the heme iron from the focused azole library (60 compounds) and additional unique azole-containing compounds identified in the large diverse drug libraries initially screened for inhibition that also cause a spectral shift (7 additional compounds) (Fig. 11B). This set includes 117 conformers of the 67 iron-binding compounds and 52 conformers of the 37 inactive compounds. The resulting pharmacophore identified four common features: one aromatic ring, one hydrophobic feature, and two hydrogen bond acceptors (Fig. 11B). This pharmacophore encompasses the hydrogen bond acceptors identified previously on both sides of the azole ring plane, but lacks the second aromatic ring and hydrophobic feature positioned to one side of the azole ring. Notably, this more comprehensive pharmacophore matches the structure of luliconazole even better, with the addition of one of the 1,3-dithiolane sulfurs overlapping with the second hydrogen bond acceptor.

Pharmacophore comparisons with duocarmycins

A motivating reason for determining a CYP2W1 pharmacophore was to try to provide insight for the development of pro-duocarmycins more selective for activation by CYP2W1 than CYP1A1. Although azole compounds are coordinated to the heme iron, pro-duocarmycins are substrates, so they should be aligned so that the site of metabolism is about 3.5 Å above the heme iron to allow space for oxygen during catalysis. The relative distance and placement of various features highlighted in the pharmacophore model can be compared to shared features of the pro-duocarmycin substrates. For example, the pharmacophore models in Figure 10 exhibit an aromatic ring about 4 Å away and hydrophobic feature about 6 Å away from the imidazole ring positioned over the heme iron. Similarly, the duocarmycin compounds contain an indole ring about 4 Å away from the site of metabolism, and a chloride is positioned between 6 and 7 Å away from the site of metabolism (Fig. 12). Alternatively, the pharmacophore models in Figure 10 exhibit a hydrogen bond acceptor about 4 Å away from the imidazole ring. The duocarmycin compounds also exhibit a hydrogen bond acceptor about 4 Å away from the site of metabolism in the form of a carbonyl oxygen. Although the planar ring and hydrogen bond acceptors can be identified at the appropriate distance from the site of metabolism, these two features are not oriented relative to each other in the same way in the duocarmycin prodrugs. In other words, those features are fulfilled but not all at the same time. Therefore, it may be of interest to design duocarmycin prodrugs that simultaneously fit all features of the CYP2W1 pharmacophore.

Figure 12.

Comparison of CYP2W1 Azole pharmacophore to pro-duocarmycin substrates. The CYP2W1 pharmacophore (from Fig. 10C) exhibits an aromatic ring feature (orange ring) representative of the azole ring that coordinates to the heme iron. From this feature, a hydrophobic feature (green sphere) is measured about 6 Å away, an aromatic ring feature about 4 Å away, and hydrogen bond acceptor about 4 Å away. In comparison, the CYP2W1 pro-duocarmycin substrate, ICT 2706, site of metabolism also contains an aromatic feature nearly 4 Å away (orange dashed line), a hydrophobic feature about 7 Å away (green dotted line), and hydrogen bond acceptor about 4 Å away (black dotted line).

Furthermore, the pharmacophore of the CYP2W1 active site including all azoles generating a spectral shift (Fig. 11B), additionally highlights two hydrogen bond accepting features between 3.5 and 5 Å away from the imidazole ring in two directions. This is again reflected in ICT2706 by the carbonyl oxygen 4 Å away from the site of metabolism. The inclusion of two hydrogen bond acceptors in the pharmacophore may suggest that duocarmycin prodrugs containing a second hydrogen bond acceptor may be better stabilized in the CYP2W1 active site. This is the only feature reflected in ICT2706 as one hydrophobic feature and the aromatic feature observed in the pharmacophore of Figure 10 are absent from this pharmacophore. Thus neither the pharmacophores in Figure 10 nor 11 fit the duocarmycin prodrugs particularly well, but they both may offer suggestions for the design of compounds better accommodated by the CYP2W1 active site.

Pharmacophore elements were compared to the predicted CYP2W1 active site generated with AlphaFold (https://alphafoldserver.com/). Consistent with the many CYP2 experimental structures on which this prediction is ultimately based, there are a number of phenylalanine side chains predicted to project into the active site (F475 at the tip of the β4 loop and F105, F115, and F116 in or immediately following the B′ helix) and which could pi-stack or t-stack with the ligand aromatic ligand rings identified in the CYP2W1 pharmacophores. Predicted first-shell amino acids that could be hydrogen bond donors at physiological pH include T476 at the tip of the β4 loop, T304 on the I helix but farther away from the active site, and R99 low in the active site just above the heme plane. Without an experimental liganded structure, it is difficult to predict, but T476 is the only one positioned high enough in the active site to be a reasonable candidate.

Although CYP2W1 pharmacophores are useful for proposing the general active site features of this structurally undefined enzyme, to modulate pro-duocarmycin selectivity the goal would be not only to optimized compatibility with the CYP2W1 active site but to design compounds less compatible with the CYP1A1 active site. Before a structure of CYP1A1 was available, its active site shape was quite successfully predicted via pharmacophore models. These models suggested a planar active site to complement the highly planar substrates of CYP1A1 (34). Indeed most experimental X-ray structures CYP1A1 of various ligands demonstrate a highly planar active site (23, 35). Although CYP1A1 structural changes have also been observed to accommodate nonplanar ligands (36), structures with two different duocarmycins (16) reveal that although the two planar halves of these molecules could orient relative to each other in various ways, within the CYP1A1 active site both are constrained to be strictly planar. By comparison, CYP2W1 pharmacophores suggest this active site is substantially more three-dimensional because it quite readily accommodates ligands such as clotrimazole with its trigonal pyramidal shape (Fig. 8) and MK-912 which had planar components but overall adopts an L-shape (Fig. 7). This diversity in the CYP2W1 ligand profile suggests that it may exhibit a differently shaped, less restricted and/or more dynamic active site than CYP1A1, which could potentially be exploited for the design of a more selective duocarmycin prodrug.

Consideration of broader selectivity

Although the primary consideration in the redesign of pro-duocarmycins is removal of CYP1A1 compatibility, such a program must also monitor selectivity versus other human cytochrome P450 enzymes, particularly those involved in drug metabolism. A previous report used this same focused azole library used herein to identify azole compounds binding to CYP2A6, CYP2D6, and CYP8B1 (31). Comparisons of the data for these four human enzymes reveal that seven compounds exhibited a spectral shift only with CYP2W1. These compounds are IB-MECA, benzimidazole, glasdegib, HC-030031, lomeguatrib, ChkII inhibitor 2, and candesartan cilexetil (Fig. 13). Two are anti-inflammatory drugs (IB-MECA, HC-030031), two are indicated for cancer (glasdegib and lomeguatrib), and one for hypertension (candesartan cilexetil). Although these compounds are unique binders to CYP2W1, it is not yet clear what structural features distinguishes them from other compounds in the screen, so there remain unexplored aspects of CYP2W1 active site interactions.

Figure 13.

Unique CYP2W1 azole ligands. In assessing the binding of 104 azoles in the focused azole library to CYP2W1, seven azoles appeared to uniquely bind to CYP2W1 over CYP2A6, CYP2D6, and CYP8B1: glasdegib, lomeguatrib, candesartan cilexetil, benzimidazole, HC-030031, IB-MECA, and Chk2 Inhibitor II.

Conclusions

Overall this study substantially expanded the known CYP2W1 ligand profile by the identification of 694 inhibitors and 67 active site binders. The breadth of chemical diversity among CYP2W1 ligands was revealed by the identification of a substrate enabling high-throughput inhibition screening, complemented by an active site binding assay. Overlap of the CYP2W1 ligand profile with other family 2 P450 enzymes has been better defined.

This new wealth of ligand information was then used to identify common physicochemical features compatible with the CYP2W1 active site. It rapidly became apparent that pharmacophore models exhibited contradictory positioning of ligands in the active site in the absence of a more global constraint to facilitate compound alignment. This is not too surprising given the diversity of ligands able to bind many closely related CYP family 2 and family 3 enzymes. When pharmacophore models were built with compounds that coordinate the CYP2W1 heme iron, the additional positional and alignment constraints yielded much more sensible and consistent information. Consensus features in addition to the aromatic imidazole included 1 to 2 hydrophobic elements and 1 to 2 hydrogen bond acceptors, with specific positioning. Some data suggested that one hydrogen bond acceptor might be more important than the other for ligand affinity, while some compounds might be able to accommodate both simultaneously. It is of note that at least some P450 enzymes are very flexible, particularly with regard to features bordering the active site such as helices F through G and the B-C loop. This allows P450 active sites to accommodate ligands of various sizes and conformations as demonstrated by CYP2W1. As each pharmacophore is based on a slightly different set of compounds, those pharmacophore models highlight different active site features. Therefore, each pharmacophore may still describe the CYP2W1 active site but in various conformations. Further studies may identify more physiochemical features unique to the CYP2W1 active site to be exploited for the design of selective duocarmycin prodrugs.

Experimental procedures

Expression and purification of CYP2W1

The CYP2W1 construct was designed and protein expressed as described previously (16). The CYP2W1 purification protocol was modified from that published previously as described below.

The entirety of the purification was performed in a cold box at 4 ˚C or on ice to stabilize the P450 enzyme. A frozen cell pellet of DH5α Escherichia coli expressing CYP2W1 from 6 L of culture was thawed for purification in 600 ml resuspension buffer consisting of 100 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.4, 500 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM imidazole, and 20% (v/v) glycerol. Then 0.3 mg/ml lysozyme was dissolved in buffer and added to the resuspension followed by stirring for 30 min. Subsequently, 0.1 mg/ml DNase was added followed by homogenization using a Dounce homogenizer. Cells were lysed using an Avestin microfluidizer around 10,000 psi twice. The lysed sample was then centrifuged at 119,000g for 45 min to pellet the cell membranes containing CYP2W1. These membranes were resuspended in loading buffer used for metal affinity chromatography. The loading buffer consists of 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 500 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM imidazole, 20% (v/v) glycerol, and 1% (w/v) 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]propane-1-sulfonate (CHAPS, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The sample stirred for 1 h to extract CYP2W1 from the membrane before being centrifuged at 119,000g for 45 min again. The red CYP2W1 supernatant was then loaded onto a 30 ml nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid column (Qiagen). It was then washed with four column volumes of loading buffer and six column volumes of wash buffer with a higher concentration of imidazole to elute weakly binding contaminant proteins (100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 100 mM sodium chloride, 15 mM imidazole, 20% (v/v) glycerol, and 9 mM CHAPS). CYP2W1 was eluted from the column using a gradient to 30% elution buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 100 mM sodium chloride, 250 mM imidazole, 20% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.25% (w/v) CHAPS) over two column volumes to elute the more tightly bound contaminant proteins, also eluting some CYP2W1. The rest of the CYP2W1 protein was eluted with a step to 100% elution buffer over four column volumes. This later elution typically contains a purer sample of CYP2W1. The elution was monitored using both absorbance at 280 nm and 425 nm. Fractions eluted with 100% elution buffer which exhibited absorbance at 425 nm (corresponding to the Soret peak of CYP2W1 when imidazole is coordinated to the heme iron) were pooled and diluted 5-fold with ion exchange loading buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate pH, 7.4, 50 mM sodium chloride, 20% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.05% (w/v) CHAPS). The sample was then loaded onto two 5-ml Hi-Trap carboxymethyl-Sepharose fast-flow columns (Cytiva) in series. CYP2W1 bound to the columns was first washed with 20 column volumes of loading buffer to deplete detergent and imidazole before elution using a five column volume gradient to 100% elution buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 500 mM sodium chloride, and 20% (v/v) glycerol) and five column volume hold at 100% elution buffer. Eluting fractions were then pooled according to absorbance at 418 nm, indicative of water-bound CYP2W1. The pooled fractions were concentrated to about 1 ml, loaded onto a 16/600 Superdex 200 size-exclusion chromatography column (Cytiva), and isocratically eluted with ion exchange elution buffer. The major elution peak, corresponding to a pentamer, was pooled, flash frozen, and stored at −80 ˚C until use. CYP2W1 was evaluated for purity both by SDS-PAGE, where it was often the sole protein band, and by comparing the absorbance of the P450 Soret peak at 418 nm to the absorbance at 280 nm, typically at a ratio of about 1.3. Absorbance spectra were used to calculate CYP2W1 concentration for ligand binding assays using the extinction coefficient of 100 mM−1 cm−1 for water-bound P450 enzymes (37). Fe(II).CO versus Fe(II) difference spectra were used to assess the proper coordination of the heme prosthetic group in the active site, and CYP2W1 typically exhibits absorbance solely at 450 nm. Difference spectra were used calculate CYP2W1 concentration for luminescence assays using the extinction coefficient of 91,100 mM−1 cm−1 (38).

Expression and purification of cytochrome P450 reductase

Human cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) was expressed and purified as previously described (39).

Low-throughput luminescence assay (96-well plate)

Luminescence assays were performed under initial rate conditions with purified CYP2W1 and CPR to assess P-Glo Luciferin-1A2 (Promega) metabolism and inhibition of CYP2W1. A reconstituted protein system was made up with 14 pmol CYP2W1, 28 pmol CPR, and 18.5 μM luciferin-1A2 substrate per reaction in assay buffer consisting of 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4. This reconstituted protein system was allowed to incubate for 20 min at room temperature. Then 12.5 μl of the system was added to reaction wells, control wells, and to wells used to generate the calibration curve in a white 96-well microplate (Costar). Control wells used to define total CYP2W1 activity contained an equal concentration of solvent as compared to reaction wells with no inhibitor. Control wells used to define minimum CYP2W1 activity were administered Promega Detection reagent to stop any reaction before NADPH is added to start the reaction. Luciferin standards were added to wells used for generating the calibration curve. The plate was allowed to incubate at 37 ˚C for 5 min. To start the reaction, NADPH was then added to a final concentration of 100 μM in reaction wells and control wells defining total CYP2W1 activity before the plate was returned to the 37 ˚C incubator for 45 min. The reaction was stopped with 50 μl Promega Detection Reagent with cysteine. After all wells contained Promega Detection Reagent, 25 μl NADPH was also added to the positive control wells and wells for the calibration curve. The plate was allowed to develop for 20 min at 37 ˚C before luminescence in each well was quantified with a Promega GloMax plate reader. Luminescence was read at 6.5 mm height for 0.5 s using the AlphaScreen emission 570 filter. The calibration curve from 2.5 pM to 2.5 nM luciferin was used to quantify luciferin in each well, which was then used to calculate the specific activity of CYP2W1. The Michaelis constant (Km) and turnover (kcat) values were determined using the Michaelis–Menten nonlinear regression in GraphPad Prism.

High-throughput luminescence assay (384-well plate)

A higher throughput version of the same luminescence assay was developed and validated. This version included higher substrate concentrations (60–150 μM) and revealed some substrate inhibition >100 μM. Thus the data were fit using the substrate inhibition equation (GraphPad Prism) to determine Km and kcat (Fig. 5). This assay was then used to evaluate inhibition of CYP2W1 by 5957 compounds in three libraries provided by the Center for Chemical Genomics at the University of Michigan. Pharmacologically active compounds in the LOPAC1280 screen (Product No. LO1280) can be found at the MilliporeSigma website. Compounds in the Drug Repurposing Set and Prestwick libraries can be found in the supporting information (Table S3). A reconstituted protein system was assembled with 100 nM CYP2W1, 200 nM CPR, and 30 μM luciferin-1A2 per reaction in 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4. The reconstituted protein system was allowed to incubate for 20 min at room temperature. Meanwhile, compound from each library was added to the wells of white 384-well plates such that the total solvent content did not exceed 0.5% of the reaction volume. Compounds were tested for inhibition at a concentration of 10 μM in the reaction. Reconstituted protein system was added to all wells using a Beckman Biomek FXp automated pipettor. The plates were centrifuged at 179g for 30 s and allowed to incubate for 5 min at 37 ˚C. NADPH was then added to a final concentration of 100 μM in reaction wells and wells defining total CYP2W1 activity, and the plate was tapped to mix components to start the reaction. Control wells defining total CYP2W1 activity contained an equal concentration of solvent as reaction wells but no inhibitor. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 45 min at 37 ˚C. Promega detection reagent was added at a 1:1 ratio to all wells to stop all reactions, then NADPH was added to wells defining minimum CYP2W1 activity. The plates were allowed to develop at 37 ˚C for 30 min before luminescence was read in the PerkinElmer EnVision plate reader. Luminescence was read at 6.5 mm height for 0.5 s using the AlphaScreen emission 570 filter. Compounds resulting in inhibition greater than three standard deviations from the negative control wells were considered hits.

Spectral shift assay

The high-throughput spectral shift assay was performed as previously described (31).

Pharmacophore generation

The pharmacophore models were generated as described previously (31) with a few adjustments. Ligands were aligned using the SMARTS sequence [cr5]:[nX2r5]:[c,nr5] to better incorporate the proper alignment of ligands containing triazoles, and the Phase Hype Scoring method was used. Compounds designated as active and inactive for the various pharmacophores are specified in the text.

Data availability

All of the data are included in this manuscript or the supporting information.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information (31).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Staff in the University of Michigan Center for Chemical Genomics including Andy Alt, Aaron Robida, and Steve Vander Roest were instrumental in advising on high throughput assay adaptation, providing chemical libraries for screening, and assisting in data processing.

Author contributions

E. K. F. and E. E. S. writing–review and editing; E. K. F. and E. E. S. writing–original draft; E. K. F. and E. E. S. visualization; E. K. F. and E. E. S. conceptualization; E. K. F. and E. E. S. formal analysis; E. K. F. validation; E. K. F. software; E. K. F. resources; E. K. F. methodology; E. K. F. investigation; E. E. S. supervision; E. E. S. project administration; E. E. S. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by NIH R37 GM076343 (to E. E. S.) and T32 GM007767 (supporting E. F.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Joseph Jez

Supporting information

References

- 1.Guo J. 2016. Colon Cancer Specific Cytochrome P450 2W1: Polymorphism, Membrane Topology and Endogenous Roles in Development Doctoral Degree, Karolinska Institutet. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choong E., Guo J., Persson A., Virding S., Johansson I., Mkrtchian S., et al. Developmental regulation and induction of cytochrome P450 2W1, an enzyme expressed in colon tumors. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang K., Jiang L., He R., Li B.L., Jia Z., Huang R.H., et al. Prognostic value of CYP2W1 expression in patients with human hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour. Biol. 2014;35:7669–7673. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenstedt K., Hallstrom M., Ledel F., Ragnhammar P., Ingelman-Sundberg M., Johansson I., et al. The expression of CYP2W1 in colorectal primary tumors, corresponding lymph node metastases and liver metastases. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:885–891. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.887224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Presa D., Khurram S.A., Zubir A.Z.A., Smarakan S., Cooper P.A., Morais G.R., et al. Cytochrome P450 isoforms 1A1, 1B1 and 2W1 as targets for therapeutic intervention in head and neck cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98217-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aiyappa-Maudsley R., Storr S.J., Rakha E.A., Green A.R., Ellis I.O., Martin S.G. CYP2S1 and CYP2W1 expression is associated with patient survival in breast cancer. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 2022;8:550–566. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Society A.C. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2024. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stenstedt K., Hallstrom M., Johansson I., Ingelman-Sundberg M., Ragnhammar P., Edler D. The expression of CYP2W1: a prognostic marker in colon cancer. Anticancer. Res. 2012;32:3869–3874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheldrake H.M., Travica S., Johansson I., Loadman P.M., Sutherland M., Elsalem L., et al. Re-engineering of the duocarmycin structural architecture enables bioprecursor development targeting CYP1A1 and CYP2W1 for biological activity. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:6273–6277. doi: 10.1021/jm4000209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin W., Trzupek J.D., Rayl T.J., Broward M.A., Vielhauer G.A., Weir S.J., et al. A unique class of duocarmycin and CC-1065 analogues subject to reductive activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15391–15397. doi: 10.1021/ja075398e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao H.P., Zhao H., Hudson R., Tong X.M., Wang M.H. Duocarmycin-based antibody-drug conjugates as an emerging biotherapeutic entity for targeted cancer therapy: pharmaceutical strategy and clinical progress. Drug Discov. Today. 2021;26:1857–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2021.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eis P.S., Smith J.A., Rydzewski J.M., Case D.A., Boger D.L., Chazin W.J. High resolution solution structure of a DNA duplex alkylated by the antitumor agent duocarmycin SA. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;272:237–252. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugiyama H., Ohmori K., Chan K.L., Hosoda M., Asai A., Saito H., et al. A novel guanine N3 alkylation by antitumor antibiotic duocarmycin A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:2179–2182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Travica S., Pors K., Loadman P.M., Shnyder S.D., Johansson I., Alandas M.N., et al. Colon cancer-specific cytochrome P450 2W1 converts duocarmycin analogues into potent tumor cytotoxins. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:2952–2961. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lang D., Radtke M., Bairlein M. Highly variable expression of CYP1A1 in human liver and impact on pharmacokinetics of riociguat and granisetron in humans. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019;32:1115–1122. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.8b00413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bart A.G., Morais G., Vangala V.R., Loadman P.M., Pors K., Scott E.E. Cytochrome P450 binding and bioactivation of tumor-targeted duocarmycin agents. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2022;50:49–57. doi: 10.1124/dmd.121.000642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshioka H., Kasai N., Ikushiro S., Shinkyo R., Kamakura M., Ohta M., et al. Enzymatic properties of human CYP2W1 expressed in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;345:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y., Wan D., Yang J., Hammock B.D., Ortiz De Montellano P.R. Catalytic activities of tumor-specific human cytochrome P450 CYP2W1 towards endogenous substrates. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016;44:771–780. doi: 10.1124/dmd.116.069633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karlgren M., Gomez A., Stark K., Svard J., Rodriguez-Antona C., Oliw E., et al. Tumor-specific expression of the novel cytochrome P450 enzyme, CYP2W1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;341:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao Y., Guengerich F.P. Metabolomic analysis and identification of a role for the orphan human cytochrome P450 2W1 in selective oxidation of lysophospholipids. J. Lipid Res. 2012;53:1610–1617. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M027185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishida C.R., Lee M., de Montellano P.R.O. Efficient hypoxic activation of the anticancer agent AQ4N by CYP2S1 and CYP2W1. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010;78:497–502. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.065045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan B.S., Tiong K.H., Muruhadas A., Randhawa N., Choo H.L., Bradshaw T.D., et al. CYP2S1 and CYP2W1 mediate 2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-5-fluorobenzothiazole (GW-610, NSC 721648) sensitivity in breast and colorectal cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1982–1992. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bart A.G., Scott E.E. Structures of human cytochrome P450 1A1 with bergamottin and erlotinib reveal active-site modifications for binding of diverse ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:19201–19210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanza D.L., Code E., Crespi C.L., Gonzalez F.J., Yost G.S. Specific dehydrogenation of 3-methylindole and epoxidation of naphthalene by recombinant human CYP2F1 expressed in lymphoblastoid cells. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1999;27:798–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmid B., Bircher J., Preisig R., Kupfer A. Polymorphic dextromethorphan metabolism: co-segregation of oxidative O-demethylation with debrisoquin hydroxylation. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1985;38:618–624. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1985.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillam E.M., Aguinaldo A.M., Notley L.M., Kim D., Mundkowski R.G., Volkov A.A., et al. Formation of indigo by recombinant mammalian cytochrome P450. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;265:469–472. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshimura R., Ueda N., Nakamura J. Low dosage of levomepromazine did not increase plasma concentrations of fluvoxamine. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2000;15:233–235. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200015040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skinner M.H., Kuan H.Y., Pan A., Sathirakul K., Knadler M.P., Gonzales C.R., et al. Duloxetine is both an inhibitor and a substrate of cytochrome P4502D6 in healthy volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003;73:170–177. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2003.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oldham H.G., Clarke S.E. In vitro identification of the human cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of R(+)- and S(-)-carvedilol. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1997;25:970–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsky R.L., Obach R.S., Gaman E.A., Gleeson J.P., Proctor W.R. Selective inhibition of human cytochrome P4502C8 by montelukast. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2005;33:413–418. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.002766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frydendall E., Scott E.E. Development of a high throughput cytochrome P450-ligand binding assay. J. Biol. Chem. 2024;300 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2024.107799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J., Offei S.D., Yoshimoto F.K., Scott E.E. Pyridine-containing substrate analogs are restricted from accessing the human cytochrome P450 8B1 active site by tryptophan 281. J. Biol. Chem. 2023;299 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.103032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denisov I.G., Baas B.J., Grinkova Y.V., Sligar S.G. Cooperativity in cytochrome P450 3A4: linkages in substrate binding, spin state, uncoupling, and product formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:7066–7076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Groot M.J., Ekins S. Pharmacophore modeling of cytochromes P450. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2002;54:367–383. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walsh A.A., Szklarz G.D., Scott E.E. Human cytochrome P450 1A1 structure and utility in understanding drug and xenobiotic metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:12932–12943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.452953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bart A.G., Takahashi R.H., Wang X., Scott E.E. Human cytochrome P450 1A1 adapts active site for atypical nonplanar substrate. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2020;48:86–92. doi: 10.1124/dmd.119.089607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luthra A., Denisov I.G., Sligar S.G. Spectroscopic features of cytochrome P450 reaction intermediates. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011;507:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Omura T., Sato R. Fractional solubilization of haemoproteins and partial purification of carbon monoxide-binding cytochrome from liver microsomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1963;71:224–226. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(63)91015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bart A.G., Scott E.E. Structural and functional effects of cytochrome b5 interactions with human cytochrome P450 enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:20818–20833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All of the data are included in this manuscript or the supporting information.