Abstract

This review thoroughly examines the potential of water ultrasonication (US) for producing hydrogen. First, it discusses ultrasonication reactor designs and techniques for measuring ultrasonication power and optimizing energy. Then, it explores the results of hydrogen production via ultrasonication experiments, focusing on the impact of processing factors such as ultrasonication frequency, acoustic intensity, dissolved gases, pH, temperature, and static pressure on the process. Additionally, it examines advanced ultrasonication techniques, such as US/photolysis, US/catalysis, and US/photocatalysis, emphasizing how these techniques could increase hydrogen production. Lastly, to progress the efficacy and scalability of hydrogen generation through ultrasonication, the review identifies existing challenges, proposes solutions, and suggests areas for future research.

Keywords: Hydrogen generation, Ultrasound, Water ultrasonication, Acoustic cavitation bubble, Methanol ultrasonication, Methane ultrasonication

1. Introduction

A growing number of people are realizing that hydrogen is a clean, sustainable energy source [[1], [2], [3]]. However, conventional production techniques such as gasification, partial oxidation, and steam reforming use fossil fuels and increase CO2 emissions [[4], [5], [6], [7]]. To address these concerns, researchers have investigated alternative technologies, including water electrolysis, biological photosynthesis, and photocatalysis [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]]. Of these substitutes, water ultrasonication, also known as ultrasound-driven hydrogen generation, has garnered significant interest [14,15]. This method uses high-energy ultrasound (20 kHz to 1 MHz) to produce hydrogen from water [[16], [17], [18]]. Studies using different ultrasound frequencies have demonstrated ultrasonication's effectiveness, achieving hydrogen yields up to 200 times higher than conventional photocatalysis [19,20]. These results recommend that ultrasonication is a cleaner, more talented method for producing hydrogen that could significantly advance the development of renewable energy solutions worldwide.

Acoustic cavitation is the process by which bubbles of vapor or gas collapse in aqueous solutions when exposed to ultrasonication [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25]]. Temperatures as high as 6000 K can be produced within a gas/vapor bubble during its collapse over the course of nanoseconds [[26], [27], [28], [29]]. This intense process promotes water sonolysis, also known as pyrolysis, which produces hydrogen peroxide, molecular hydrogen, and reactive oxygen species (•OH, HO2•, O, H•, O3) [[30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]]. Fig. 1 illustrates the typical sequence of events within a bubble through the strong compression stage, which occurs near the termination of the collapse. At this point, the bubble reaches its peak sonochemical activity. If the bubble bursts, its contents may be released into the surrounding aqueous solution, where they can dissolve and participate in other chemical processes.

Fig. 1.

Typical temperature vs. time (2.14–2.16 µs) and reaction system progression within an oscillated acoustic bubble at the end of the first bubble collapse. Conditions: R0 (initial bubble radius) = 3.2 µm (a) and 6 µm (b), frequency: 355 kHz, applied acoustic intensity: 1 W/cm2 and a water temperature: 20 °C [128].

Fig. 1 shows that the simulation results indicate minimal hydrogen peroxide production. This is primarily due to hydrogen peroxide's instability at high temperatures. The primary production of hydrogen peroxide occurs in the liquid shell encircling the bubble through the autorecombination of hydroxyl and hydroperoxyl radicals (Eqs. (1), (2)). Similarly, hydrogen can be produced in the liquid adjacent to the collapsing bubble through the recombination of hydrogen radicals (Eq. (3). While these findings offer valuable insights, research into the specific mechanics of hydrogen creation is ongoing and constantly evolving.

| 2•OH → H2O2 | (1) |

| 2HO2• → H2O2 + O2 | (2) |

| 2H• → H2 | (3) |

Throughout water ultrasonication, hydrogen peroxide accumulates in the liquid, and hydrogen is removed from the gaseous phase overhead the irradiated water. Under argon-saturation, the rate of hydrogen generation is almost 10–15 µM/min [36,37]. In contrast, ultrasonication in water-methanol mixtures or acetylene-saturated water yields rates exceeding 100 µM/min [38,39]. Different additives can be added into the gas milieu or ultrasonicated water to enhance sonochemical hydrogen production [40,41]. For example, hydrocarbons such as ethane and methane can significantly increase hydrogen production by entering the bubble's hot gaseous phase and undergoing pyrolysis to generate more hydrogen [42]. Similarly, alcohols, such as methanol, undergo pyrolysis inside the bubble to produce hydrogen [38,39]. Nevertheless, high concentrations of these additives can lower the total hydrogen output, so their concentration must be carefully controlled.

Many research groups have contributed to several recent reviews on hydrogen generation via ultrasonication [[43], [44], [45]]. This paper provides an up-to-date summary of the latest developments in this area. It focuses on recent experimental advancements in ultrasonic hydrogen generation and examines the factors that influence this process. To provide a comparative analysis of ultrasonication, the study reviews current research on US/catalysis and US/photolysis for hydrogen generation. The study addresses the challenges and potential of hydrogen production through ultrasonication, proposing solutions and ideas for future exploration. First, the study discusses concerns regarding reactor configurations and the measurement of acoustic power dissipated into the solution, which are important elements that determine hydrogen generation effectiveness. Then, it addresses these main issues.

2. Ultrasonic hydrogen generation: reactors configurations

The two primary forms of ultrasonication reactors commonly employed in scientific settings are horn-type and standing-wave configurations [[46], [47], [48]]. Standing-wave systems are called bath systems, while horn-type setups are called probe systems. In horn-type systems, the tip of the submerged horn directly irradiates the liquid, either above or below. This design produces a strong, focused ultrasonic field, making effective sonochemical reactions and confined cavitation possible. However, the resulting ultrasonic wave rapidly loses amplitude and becomes nearly spherical as the liquid height increases or the length from the horn tip augments. The high amplitude of ultrasonic waves focused close to the horn tip creates localized cavitation zones, a characteristic of these devices [[49], [50], [51]]. On the other hand, plate transducers are fixed to the bottom surface of the sonoreactor in standing-wave systems. These systems operate at much lower ultrasonic amplitudes than horn-type designs. In standing-wave reactors, the reversal of the radiation force direction causes cavitation bubbles to form as the ultrasonic amplitude approaches the critical point. Unlike horn-type systems, which have highly focused activity, this behavior results in a more dispersed cavitation zone [49,52].

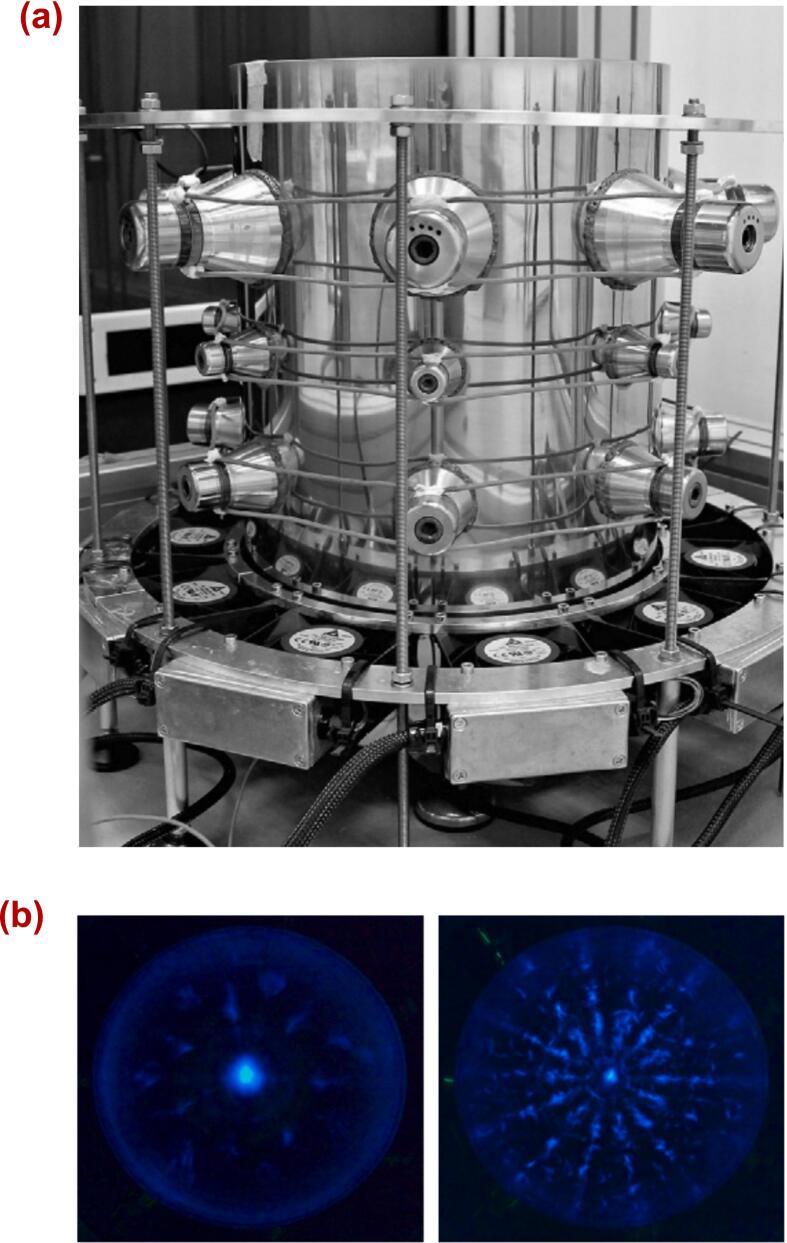

Sonochemiluminescence (SCL) and multibubble sonoluminescence (MBSL) are useful techniques for observing reaction zones and localized reactivity in ultrasonication reactors [[52], [53], [54], [55], [56]]. Fig. 2 illustrates an ideal reactor setup for hydrogen production via ultrasonication. As the caption explains, Fig. 2 illustrates and compares the efficacy and efficiency of various reactor designs.

Fig. 2.

Visualization of the spatial distribution of cavitation activity in laboratory scale ultrasonication reactors using SCL (a,b) [129] and MBSL (c,d) [130]. Air-saturated water in a 20 kHz-cup horn system (a); air-saturated water in a 447 kHz bath (piezoelectric disc) (b); Ar-saturated water in a cylindrical flask (c); and Ar-saturated water in a horn-type transducer at 151 kHz (d).

Fig. 2a and 2c demonstrate that SCL and MBSL are primarily concentrated near the surface of the titanium horn, also referred to as the cup horn, at low frequencies of 20 and 24 kHz. However, most SCL and MBSL activity occurs in a larger volume near the liquid surface at higher frequencies, such as 487 kHz (Fig. 2b) and 151 kHz (Fig. 2d). Very petite light is seen at the emitter's surface. This difference in response zones results from the interaction of cavitation dynamics, ultrasonication frequency, and dissolved gas concentration. Higher frequencies require more energy for cavitation in water than lower frequencies. Furthermore, the cavitation threshold in air-saturated water is substantially lower than in degassed water. Measurements of dissolved oxygen after 20 min of ultrasonication further highlight this phenomenon. At 487 kHz, the level of dissolved oxygen decreased by 5.20 mg/L; at 20 kHz, the diminution was 6.80 mg/L. These results suggest a greater sonolytic degassing effect at higher frequencies.

Due to the high-pressure amplitude at 20 and 24 kHz, cavitation primarily occurs near the surface of the emitter. A noteworthy amount of the ultrasonic energy is absorbed by the subsequent bubble cloud, preventing waves from propagating and confining cavitation to a small area. Conversely, degassing at the emitter's surface increases the cavitation threshold at 487 and 151 kHz. This shifts cavitation activity to the gas/liquid interface. Unlike with low-frequency settings, the larger dissolved gas concentration enables more widespread cavitation and creates a separate reaction zone.

As the aforementioned research makes clear, a standing wave ultrasonication setup produces more consistent and higher levels of sonochemical activity than a basic horn system. The next set of experiments will show that most studies on hydrogen production through ultrasonication use standing wave reactors that operate at higher frequencies.

3. Ultrasonication power

The calorimetric approach is habitually utilized to calculate the acoustic power dissipated into a liquid, which causes acoustic cavitation [57,58]. Some of the energy delivered by ultrasonic waves is lost during propagation in liquid media, raising the temperature [59]. This temperature increase can be employed to calculate the acoustic power transported to the liquid unless it is offset by external thermostatic measures.

The conventional method for this estimate is the calorimetric method, which frequently uses water as the sonicated medium. The expression (4), where CP (4.18 J/g·K for water), m (g) and ΔT/Δt (K/s) represent the specific heat, the solution mass, and the rate of temperature rise, respectively, can be employed to compute the acoustic power (Pac) conveyed to the liquid by tracking the temperature increase over time. Due to its reliable and well-established thermal properties, water is commonly used in calorimetric investigations. A thermocouple submerged directly in the ultrasonicated solution measures the temperature within the sonoreactor.

| (4) |

During ultrasonication, the power density (PD) and acoustic intensity (In) released into the milieu are described by Eqs. (2), (3), respectively, where V is the volume of ultrasonicated water, S is the area of the emitting device (either a piezoelectric ceramic or a transducer), and Pac is the acoustic power:

| (5) |

| (6) |

Both ultrasonication and experimental factors significantly impact the quantity of acoustic power transported to the liquid. Operating parameters include saturated gases, solution volume, temperature, and pH. Ultrasonication parameters include ultrasonic frequency and the quantity of electrical power applied to the transducer.

Fig. 3a illustrates an experiment in which 300 mL of water was ultrasonicated at 300 kHz using 60 W of applied electrical power (PE). The configuration included a cylindrical, air-exposed, standing-wave ultrasonication reactor with 500 mL of maximum capacity. The sonoreactor contained a piezoelectric ceramic plate with a diameter of 4 cm and a surface area of 12.54 cm2. According to Eqs. (1), (2), (3), the computed acoustic power was 25.68 W, which translates to an acoustic intensity of 2.04 W/cm2 and a power density of 85.6 W/L.

Fig. 3.

Temperature vs. ultrasonication time (a) and Pac, In, and PD profiles in relation to water volume (100, 200, 300, and 400 mL) and applied power (PE: 20, 40, and 60 W) (c)-(d), respectively, at 300 kHz ultrasonication standing wave [131].

Fig. 3b–d illustrate the effects of varying the volume of water (100, 200, 300, or 400 mL) and electrical power (20, 40, or 60 W) on the outcome. Increasing the water volume from 100 to 300 mL caused the acoustic power and intensity values to increase and then decrease (Fig. 3b and 3c). Higher electrical powers produced higher acoustic power and intensity values regardless of the water volume. However, as the liquid volume augmented, the power density entering the liquid diminished gradually (Fig. 3d). The calculated acoustic powers, which comprise 30 % to 60 % of the electrical power provided to the transducer, demonstrate the transformation process's effectiveness and how operating factors affect ultrasonication performance.

According to the calorimetric measurements of Hua and Hoffmann [60], the acoustic power efficiency ranged from 40 % to 60 % of the electrical power provided to the generator. These measurements were taken while ultrasonicating with a 513 kHz transducer and a sonotrode functioning at 20.2, 39.4, and 80.6 kHz (Table 1). Similarly, Ferkous et al. [61] explored the influence of conical and cylindrical reflectors positioned on the liquid surface on acoustic power determination at 300, 630, and 800 kHz. The study maintained an ultrasonicated volume of 300 mL and used electrical powers varying from 40 to 120 W; regardless of reflector use, the efficiency was consistently between 45 % and 50 %.

Table 1.

Sizes and acoustic characteristics of sonoreactors employed by Hua and Hoffmann [60].

| Frequency (kHz)* | Diameter | Area (cm2) | Volume (mL) | Power (W) | Power (% total) |

Density, Pd (W/cm3) | Intensity, In (W/cm2) | Amplitude, Pa (Atm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20.2 | 1.41 | 1.57 | 200 | 15.8 | 40 | 0.078 | 10.0 | 5.4 |

| 39.4 | 1.25 | 1.23 | 200 | 13.5 | 60 | 0.067 | 11.0 | 5.7 |

| 80.6 | 0.406 | 0.129 | 100 | 1.05 | 60 | 0.010 | 8.10 | 4.9 |

| 513 | 5.70 | 25.5 | 600 | 39.0 | 60 | 0.065 | 1.50 | 2.1 |

Note: 20.2, 39.4, and 80.6 kHz: horn-irradiation. 513 kHz: piezoelectric transducer with lateral irradiation.

Son et al. [56] examined the relationship between acoustic power dissipation and solution volume in a standing wave ultrasonicator operating at 36 or 108 kHz. The solution volumes ranged from 50 to 350 cm3. They found that the optimal volume was 200 mL at 108 kHz, but not at 36 kHz. De La Rochebrochard et al. [62] explored the influence of liquid height, which is indirectly linked to volume, on acoustic yield in standing wave and cup-horn reactors with constant diameters. They found that the optimal liquid heights were 11.4 cm in a standing wave sonoreactor at 371 kHz and 2.6 cm in a cup-horn reactor at 22 kHz.

Asakura et al. [63] examined, in a cylindrical standing wave sonoreactor functioning at multiple frequencies (490, 321, 129, and 45 kHz), the impact of liquid height on determined acoustic power. For the three lowest frequencies, the ideal liquid heights were found to be 40, 25, and 10 cm, respectively. These results underscore the significance of operational parameters, including volume, liquid height, and frequency in optimizing ultrasonication efficiency and acoustic power dissipation.

4. Experimental conditions impact

Table 2 provides an overview of twenty-five papers examining hydrogen generation by ultrasonication under different experimental conditions. Additionally, the overall efficiency (O.E) of hydrogen generation (%), defined as the ratio of hydrogen produced to electricity consumed (HHVH2 × Hydrogen production/Electric power), was determined in most of these studies (depending on the availability of technical data), Table 2. These studies consistently demonstrate the formation of hydrogen at concentrations ranging from tens to hundreds of µM, as well as the concurrent generation of hydrogen peroxide in ultrasonicated water. Moreover, the global energy effectiveness of the sonolytic hydrogen production process remained relatively low, reaching a maximum of approximately 4 %. On the other side, the precise method of hydrogen generation is still debated. According to some accounts, gas-phase pyrolytic processes within the cavitation bubble produce hydrogen [20]. Contrarywise, other research suggests that radical recombination processes form hydrogen at the bubble/solution interface (reaction (3) [36,42]. Operating factors, including power input, frequency, and dissolved gas concentrations, significantly impact the rate at which hydrogen is generated. The following paragraphs emphasize several important points about the findings.

Table 2.

Examples of the most recent research on hydrogen generation via ultrasonication (NI stands for not indicated, V for solution volume, T for operating temperature, f for ultrasonic frequency, P for delivered electric power, Pac for acoustic power, Pd for power density, and In for acoustic intensity.

| Entry | Ultrasonicated system | Ultrasonication conditions | Main findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deionized water (DI) and DI-formate mixtures |

f = 800 kHz, In = 1.6 ergs/cm2, V = 4 mL, T = 20 ± 1 °C, pH 0.6–14, argon saturation, [formate]0 = 0–0.05 M |

|

[64] |

| 2 | Deionized water (DI) and DI-formate solutions | f = 300 kHz, In = 3.5 W/cm2, V = 55 mL, T = 20 °C, pH 10, argon saturation |

|

[65] |

| 3 | Deionized water (DI) |

f = 300 kHz, In = 3.5 W/cm2, V = 20 mL, T = 20 °C, argon saturation, CO2 and Ar-CO2, Ar-N2O and Ar-methane mixtures |

|

[95] |

| 4 | Deionized water (DI) and DI-formate mixtures |

f = 300 kHz, In = 1.6 ergs/cm2, V = 55 mL, pH 10, argon saturation [formate]0 = 0–0.1 M |

|

[65] |

| 5 | Deionized water (DI) and DI-acetate mixtures | f = 300 kHz, P = 16 W, V = 55 mL, argon saturation |

|

[66] |

| 6 | Deionized water (DI) |

f = 300 kHz, P = 12 W, V = 37.5 mL, Gaz: Argon, nitrogen (N2) and Ar-N2 atmospheres |

|

[36] |

| 7 | Deionized water (DI) |

f = 300 kHz, In = 2 W/cm2, V = 50 mL, Gas: argon and Ar-hydrocarbon mixtures |

|

[42] |

| 8 | Deionized water (DI) |

f = 1 MHz, In = 2 W/cm2, V = 37.5 mL, Gas: argon and Ar-acetylene atmospheres |

|

[38] |

| 9 | Deionized water (DI) and DI-methanol mixtures |

f = 1 MHz, In = 2 W/cm2, V = 40 mL, Gas: argon atmosphere |

|

[39] |

| 10 | Methanol-water mixtures |

f = 724 MHz, In = 50 W, V = 40 mL, T = −30 to 58 °C, argon atmosphere |

|

[67] |

| 11 | Deionized water (DI) |

f = 20 kHz, In = 0.3–4.7 W/cm2, V = 100 mL, T = 22 ± 2 °C, argon atmosphere |

|

[86] |

| 12 | Deionized water (DI) and DI-tert-butyl alcohol (TBA) solution | f = 321 kHz, Pd = 170 W/kg, V = 8 mL, argon atmosphere |

|

[124] |

| 13 | Deionized water (DI) | f = 200 kHz, PE = 200 W, V = 40 mL, argon saturation |

|

[125] |

| 14 | Deionized water (DI) |

f = 22.5 kHz (two transducers), P = 50 W for each transducer (total 100 W), V = 100 mL, T = 22 ± 2 °C |

|

[108] |

| 15 | Deionized water (DI) |

f = 20 kHz, 200 and 607 kHz, Pac = 13 W at 20 kHz, 45 W at 200 kHz and 65 W at 607 kHz, V = 50 mL for 20 kHz and 250 mL for 200 and 607 kHz, T = 20 °C, argon atmosphere |

|

[76] |

| 16 | Deionized water (DI) and DI-alcohol (methanol, ethanol, propyl alcohol) |

f = 40 kHz, P = 500 W, V = 60 mL, T = 10–30 °C, argon atmosphere |

|

[105] |

| 17 | Deionized water (DI) and DI-ethanol mixtures |

f = 38 kHz, P = 50 W, V = 300 mL, T = 25 °C, argon atmosphere |

|

[126] |

| 18 | Deionized water (DI)- t-butanol (t-BuOH) solutions |

f = 20 kHz and 359 kHz, Pac = 25 W at 20 kHz and 43 W at 359 kHz, V = 250 mL, T = ∼20 °C, Gas: argon atmosphere |

- Production rates of hydrogen were higher at higher frequency and t-butanol concentration, i.e., values of 14 (O.E: 0.078 %) and 19 µM/min (O.E: 0.105 %) were obtained at 359 kHz with 1 and 20 mM t-BuOH and 5 (O.E: 0.048 %) and 7 µM/min (O.E: 0.067 %) were registered at 20 kHz with 0.125 and 0.5 M t-BuOH. | [77] |

| 19 | Deionized water (DI)-KI solution (0.1 M KI) |

f = 2.4 MHz (probe), P = 15 W, V = 20 mL, T = 25 °C, Gas: argon and Ar-CO2 atmospheres |

- The production of hydrogen after 180 min of irradiation decreased from 17 µmol (O.E: 0.054 %) under pure argon atmosphere to 5.5 µmol (O.E: 0.0175 %) when the gas matrix contained only 2 % CO2. | [127] |

| 20 | Deionized water (DI) in the presence of metal oxides (TiO2, ZrO2, ThO2) |

f = 20 kHz, 362 kHz, Pd = 0.34 W/mL (20 kHz), 0.25 W/mL (362 kHz), V = 50 mL (20 kHz), 220 mL (362 kHz), T = 22 °C, Gas: argon atmosphere and [catalyst]: 4 g/L |

- At 20 kHz, micrometric ThO2-A achieved the highest H2 yield (0.45 μmol/kJ, O.E: 0.00145 %) due to fragmentation and mechanochemical effects. Nanosized oxides (e.g., ThO2-C, TiO2-A/B) enhanced H2 generation (0.30–0.42 μmol/kJ) via improved cavitation bubble nucleation. At 362 kHz, pure water produced 0.38 μmol/kJ H2 (O.E: 0.0054 %), but micrometric oxides reduced yield due to ultrasound attenuation. Nanosized oxides at 362 kHz had weak or inconsistent effects. |

[68] |

| 21 | Deionized water (DI) and DI-methanol, ethanol, glycerol, or DMSO in the presence of Au/TiO2 |

f = 40 kHz, Pd = 0.045 W/ml, V = 150 mL, T = 21–25 °C, Gas: argon atmosphere, [Au]: 0.75 wt%, [ Au/TiO2]: 0.5 g/L |

- H2 yield of 21.6 µmol/h (O.E: 0.0127 %) was obtained from water in the presence of Au/TiO2 compared to 1.3 µmol/h (O.E: 7.7 × 10−4 %) with TiO2 and 0.37 µmol/h (O.E: 2.2 × 10−4 %) without catalyst. In 4 % methanol/water, H2 production with Au/TiO2 reached 282.3 µmol/h (O.E: 0.166 %), 12 times higher than in pure water, with ∼50 % of H atoms derived from water. |

[69] |

| 22 | Deionized water (DI), natural seawater, simulated seawater in the presence of TiO2 |

f = 780 kHz, PE = 5.1 W, V = 2.5 mL, T = room temperature, Gas: argon atmosphere, [ TiO2]: 0.3 g/L |

- Optimized TiO2 (0.3 mg/mL) at 780 kHz achieved record H2 efficiencies: 8086 (DI), (O.E: 3.78 %) and 4210 (seawater) µmol/g·L·Wh (O.E: 1.97 %). Maximum H2 yield occurred at 100 acoustic cycles and 4.5 % duty cycle. NaCl in seawater reduced H2 output by ∼50 % due to radical scavenging by Na• and Cl•. |

[70] |

| 23 | Deionized water (DI) and DI/MeOH in the presence of BaTiO3 |

f = 40 kHz, PE = 60 W, V = 100 mL, T = 35 °C, Gas: argon atmosphere, [ BaTiO3]: 5, 10, 30, 100 mg/L |

- H2 yield of 270 mmol/h·g (O.E: 0.18 %) was obtained at 5 mg/L BaTiO3 in 10 % MeOH. BaTiO3 particles were reduced from ∼400 nm to ∼150 nm. Optimum position (13 mm above transducer) and low catalyst loading avoided aggregation and shielding. |

[71] |

| 24 | Distilled water and NaHCO3 (5 g) in the presence of ZnO, Cu2O, Graphene |

f = 40 kHz, PE = 110 W, V = 400 mL, T = NI, Gas: ambient air, [Catalyst]: 0.1 g/L, 1.0 g/L, 5.0 g/L |

- Using ZnO at 2.668 g/L achieved a H2 production rate of 57.6 cm3/h and energy efficiency of 7.85 %. Graphene (0.1 g/L) in sonoelectrolysis achieved the highest performance, yielding 66.4 cm3/h of H2 with an energy efficiency of 2.43 %. US increased H2 production by 10–25 %, but lowered energy efficiency due to the extra 110 W power input. H2 purity reached 50.81 %. |

[72] |

| 25 | Deionized water (DI) and DI/MeOH in the presence MoS2 |

f = 40 kHz, PE = 80 W, V = 50 mL, T = 29 °C, Gas: N2-atmosphere, MeOH: 10 % (v/v), mMoS2: 5 mg |

- MoS2 with 18.5 % sulfur vacancies (MS-1) showed the highest H2 production rate of 1423.29 μmol/g·h. MS -1 remained effective without scavengers, yielding 629.25 μmol/g·h and was stable over 6 cycles. Even in simulated seawater, MS-1 produced 268.25 μmol/g·h. |

[73] |

According to Anbar and Pecht [64], the presence of sodium formate (NaHCO2) at various concentrations (0–0.05 M) in a neutral milieu does not affect hydrogen generation at 800 kHz and an ultrasonication intensity of 1.6 ergs/cm2. In both neutral sodium formate solutions and pure water, hydrogen production was consistently measured at 25 µM/min. Since formate is a potent H• scavenger, these results imply that hydrogen production does not occur via the autorecombination of hydrogen atoms (reaction (3). Their research also showed that augmenting the alkalinity of the liquid enhances hydrogen production. The rate of hydrogen production diminished from 25 µM/min in the pH range of 6–12 to 16.2 µM/min at pH 0.6. Therefore, maximizing hydrogen yields during ultrasonication requires careful consideration of solution pH.

Hart and Henglein [65] supported the conclusions of Anbar and Pecht [64] regarding the effects of formate on hydrogen generation and related processes. Regardless of the presence or absence of formate (0 ≤ [HCO2−] ≤ 0.1 M), hydrogen production was consistently measured at ∼25 µmol/min under the following conditions: an ultrasonication frequency of 300 kHz, an ultrasonication intensity of 1.6 ergs/cm2, and an argon environment (Fig. 4a). These results lend credence to the idea that hydrogen is not generated by the autorecombination of hydrogen atoms, even with a potent radical scavenger in the liquid phase, such as formate. However, as the formate concentration increased, the hydrogen peroxide output steadily decreased, primarily due to formate ions near the bubble interface scavenging •OH radicals.

Fig. 4.

Yields of different products obtained from ultrasonicating sodium formate solutions with argon (pH 10) (a), ultrasonication of water (dashed lines) and a 0.1 M KI solution (solid lines) under different argon/oxygen mixtures (composition of gas mixture in volume percent of O2) (b), and concentration of diverse products at 30 min of ultrasonicating acetate solutions at various concentrations (c) [65].

Conversely, Gutiérrez et al. [40] found that adding acetate significantly impacted hydrogen and hydrogen peroxide production at 300 kHz and 16 W. The hydrogen production rate increased up to an acetate concentration of 0.2 M (Fig. 4b). However, hydrogen peroxide production decreased as the acetate concentration increased. This pattern is reasonable and can be attributed to •OH scavenging. No additional increase in H2 generation was observed beyond this level. According to Gutiérrez et al. [66], H• recombination at the bubble interface (Eq. (3) is part of hydrogen generation. Acetate's propensity to scavenge •OH restricts the reaction: •OH + H• → H2O2. This increases the number of H• radicals available for recombination (Eq. (3) and consequently increases hydrogen generation.

Additionally, Hart and Henglein [65] examined the generation of hydrogen in pure water saturated with different ratios of the argon/oxygen gas mixture (Fig. 4c). They noted that as the oxygen concentration in the argon matrix increased, hydrogen production decreased significantly. They ascribed this decrease to the generation of hydroperoxyl radicals (HO2•) within the bubble resulting from O2 scavenging H• radicals. According to reaction (2), HO2• recombination simultaneously increases hydrogen peroxide generation. Hart and Henglein's [65] results align with Merouani et al.'s [20] proposed primary channel for H2 generation. H• + •OH → H2 + O; thus, scavenging H• radicals lowers H2 synthesis through this pathway. Concurrently, an increase in HO2• radicals enhances hydrogen peroxide production by promoting HO2• autorecombination. These dual effects coherently explain the observed trends in hydrogen and hydrogen peroxide yields under various Ar/O2 gas compositions.

Additionally, Table 2 shows that adding chemicals to the gas matrix or ultrasonicating water greatly increases ultrasonic hydrogen generation. For instance, adding hydrocarbons at low concentrations, such as methane, ethane, and acetylene, significantly increases hydrogen generation (Fig. 5). Specifically, hydrogen formation increases as the proportion of methane in argon rises, peaking at around 8 % before decreasing (Fig. 5a). Numerous investigations have shown similar patterns: Fischer et al. [37] with D2-argon (300 kHz and 12 W), Hart et al. [38] with acetylene-argon (1 MHz and 2 W/cm2), Buettner et al. [39] with methanol-argon (1 MHz and 2 W/cm2), Hart et al. [42] with Ar-CH4 and C2H6 (300 kHz and 2 W/cm2), and Rassokhin et al. [67] with methanol-argon (724 kHz and 50 W).

Fig. 5.

Rate of CH4 consumption and H2 and CO production obtained by water ultrasonication under argon-CH4 mixtures of various compositions (a), rate of C2H6 consumption and, CH4, CO and H2 production as a function of ethane concentration in C2H6-argon mixtures (b), and yields of hydrogen production by ultrasonication of various hydrocarbons in 20 % hydrocarbon and 80 % argon mixture. Conditions: 50 cm3 of water at 300 kHz and 2 W/cm2 (c) [42].

As shown in Fig. 5c, the hydrogen output for highly saturated hydrocarbons remains mostly constant regardless of chain length. As expected, unsaturated hydrocarbons produce less hydrogen than saturated hydrocarbons. The main cause of the reported increase in hydrogen generation is the ability of methane to prevent the autorecombination of H• and •OH radicals. These radicals interact with methane, which thermally decomposes to produce hydrogen radicals (CH4 → CH3• + H•). However, hydrogen generation decreases when the methane concentration in argon exceeds 8 % (Fig. 5a). This is due to a decrease in the bubble's heat capacity. These results demonstrate the significance of carefully controlling the amount of additives to optimize hydrogen generation efficiency.

In addition to the homogeneous sonochemical enhancement of hydrogen production, the incorporation of heterogeneous catalysts can further improve sonoefficiency by enabling higher H2 yields, thereby enhancing the overall energy efficiency of the sonoprocess. To illustrate, Morosini et al. [68] proposed hydrogen evolution as an alternative dosimetric probe for sonochemical activity in argon-saturated water with metal oxides (ThO2, ZrO2, TiO2), overcoming the limitations of conventional H2O2-based dosimetry affected by catalytic degradation. At 20 kHz, all oxides enhanced H2 production, with ThO2 microparticles showing the highest efficiency via fragmentation and mechanochemical effects. Nanosized oxides, despite no fragmentation, also boosted H2 evolution through improved bubble nucleation. At 362 kHz, micrometric oxides attenuated ultrasound and reduced H2 yield, while nanosized particles had weak and variable effects. These findings highlight the frequency- and size-dependent roles of oxides in sonochemical water splitting. Similarly, Wang et al. [69] demonstrated that TiO2 loaded with Au nanoparticles significantly enhances hydrogen production under ultrasonic irradiation. Ultrasonication tests were conducted using a transducer operating at 40 kHz and 50 W, corresponding to an average ultrasound power density of 0.045 W/mL, with the temperature controlled between 21 and 25 °C. In the system containing Au/ TiO2, a notably high hydrogen generation rate of 21.6 μmol/h was accomplished, substantially exceeding the rates observed with bare TiO2 (1.3 μmol/h) and in the absence of catalyst (0.37 μmol/h). In a 4 % (1.9 %, v/v) methanol (ethanol)/water solution, H2 evolution increased to 282.3 (198.1) µmol/h with Au/TiO2, a 12-fold enhancement over water alone. Nearly half the hydrogen atoms originated from water, confirmed via isotope labeling. However, for broader practical applicability of this heterogeneous catalyst, the long-term stability of Au/TiO2 should be thoroughly evaluated, along with investigations into real wastewater matrices and the environmental impact of Au nanoparticles. In [70], ultrasonication-driven seawater splitting catalyzed by TiO2 at ambient temperature, using high-frequency ultrasonic waves at 780 kHz and 5.1 W and an optimized TiO2 dosage of 0.3 mg/mL, accomplished an important sonolytic hydrogen generation of 8086 μmol/gcat·L·Wh in pure water and 4210 μmol/gcat·L·Wh in natural seawater, corresponding to hydrogen production rates of 103.7 and 54.0 μmol/g·h, respectively. The reduced efficiency in seawater was attributed primarily to radical scavenging by salt species, as demonstrated via electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and spectroscopy bubble dynamics simulations.

On the other hand, Zhang et al. [71] stated the original fruitful demonstration of water splitting under ultrasound using a nanofluidic suspension of BaTiO3 compromising both cubic and tetragonal phases. Ultrasonic treatment (40 kHz) reduced particle dimension from ∼150 to ∼400 nm, forming a stable nanofluid. The system exhibited repeatable and stable hydrogen evolution over four days, achieving an extreme rate of 270 mmol/h·g in the presence of 5 mg/L BaTiO3 in 10 % MeOH-H2O. This study highlights the capability of ferroelectric nanofluids for efficient, vibration-induced water splitting and hydrogen generation. Additionally, in [72], hydrogen production was studies using sono-electrocatalysis and electrolysis employing Cu2O, ZnO, and graphene-based catalysts under ultrasound (110 W, 40 kHz). Sono-electrocatalysis established a 10–20 % enhancement in hydrogen generation in comparison with electrolysis, though with increased energy input. The optimal electrocatalysis condition, ZnO at 2.668 g/L, yielded 57.6 cm3/h of H2 with 7.85 % energy efficiency, while the optimal sonoelectrocatalysis condition, graphene at 0.1 g/L, achieved 66.4 cm3/h of H2 and 2.43 % energy efficiency. With the aim of enhancing the catalytic performance of MoS2, Mondal et al. [73] investigate the role of sulfur (S) vacancies in improving the piezocatalytic efficiency and their impact on the electronic structure and charge distribution of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) for hydrogen (H2) production. The defect-engineered MoS2 (MS-1) achieved a hydrogen generation rate of 1423 μmol/g·h under ultrasonication, representing more than a threefold increase compared to the pristine sample (MS-0), which yielded 439 μmol/g·h. This improvement is ascribed to the augmented piezoelectric polarization and more efficient charge carrier separation induced by sulfur vacancies. These findings underscore the effectiveness of defect engineering in modulating the electronic and catalytic properties of MoS2 for advanced hydrogen generation applications.

5. Operating parameters effect

Researchers have examined several factors affecting hydrogen production via ultrasonication, including acoustic parameters (e.g., power and frequency) and operating circumstances (e.g., irradiation volume, pressure, liquid composition, solution pH, gas saturation/composition, and liquid temperature) [16,74,75]. Each factor impacts hydrogen production uniquely.

5.1. Ultrasonication frequency

Few studies have examined the influence of frequency on hydrogen formation by ultrasonication. According to Navarro et al. [76], the chemical output of hydrogen during water ultrasonication varies with frequency. At 20 °C, in an argon environment, the output was 0.49, 0.28 and 0.12 µmol/kJ at 607, 200, and 20 kHz, respectively. Likewise, Pflieger et al. [77] observed larger hydrogen yields at 359 kHz compared to 20 kHz. Overall, these results suggest that hydrogen production rates generally increase with frequency. Lower frequencies (e.g., 20 kHz) produce lower rates than higher frequencies (>100 kHz).

The ideal frequency range for hydrogen peroxide formation is 200–600 kHz [[78], [79], [80], [81]]. However, due to limited experimental data, the ideal frequency for hydrogen generation has not yet been definitively determined. Numerical simulations of single-bubble yields demonstrate that hydrogen synthesis is affected by bubble temperature, collapse time, and chemical yield per bubble. All of these factors decrease as frequency augments from 20 to 1000 kHz [82,83]. Conversely, the amount of collapsing bubbles augments monotonically as frequency rises [84,85]. The augmented number of active cavitation bubbles at high frequency appears to be the main factor influencing hydrogen production compared to the laboratory findings of Navarro et al. [76] and the expected effects of ultrasonication frequency on individual bubble yields and bubble population dynamics [82].

5.2. Acoustic intensity

The generation of hydrogen during water ultrasonication is greatly affected by acoustic intensity. For example, hydrogen was generated at a rate of 0.8 µM/min in Ar-saturated water at 20 kHz and 0.6 W/cm2 [86]. Production rates augmented to 2.1 and 5 µM/min, respectively, when the intensity raised to 1.1 and 2.5 W/cm2 [86]. These findings align well with patterns documented for the generation of H2O2 via ultrasonication [87].

In general, the acoustic intensity must remain within two critical ranges. No ultrasonication effects are observed below the black threshold. However, efficiency decreases at the high-intensity limit, which occurs when the ultrasound wave is attenuated [[88], [89], [90]]. Due to the corresponding increase in acoustic amplitude, ultrasonication effects are enhanced within this range as acoustic intensity increases. This results in higher single-bubble hydrogen yields, longer bubble collapse durations, and higher temperatures and pressures [82,91]. Additionally, the number of active cavitation bubbles rises as intensity augments within these limits [92,93].

Therefore, the increased hydrogen generation at higher applied intensities can be explicated by the joint effects of higher single-bubble yields and a greater number of active bubbles present at higher sonic intensities.

5.3. Dissolved gases

Anbar and Pecht [64] reported that ultrasonicating water at 300 kHz and 1.6 ergs/cm2 increased hydrogen output from 9.4 µM/min in an air environment to 25 µM/min in argon. Similarly, Hart et al. [36] demonstrated a significant decrease in hydrogen generation as the nitrogen concentration in the solution increased (300 kHz and 12 W). The yield diminished from 14 µM/min to approximately 4 µM/min in a pure nitrogen environment. Gutierrez and Henglein [94] observed a comparable trend with N3− at 1 MHz and 2 W/cm2. This decline is ascribed to the scavenging of hydrogen atoms by nitrogen oxides. Reactions such as NO + H• → N + •OH play a role [36]. The ultrasonication of nitrogen inside collapsing bubbles is the main source of NO species.

Henglein [95] found that hydrogen generation decreased consistently as the concentrations of nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide in the gas matrix (argon mixed with either CO2 or N2O) increased at 300 kHz and 3.5 W/cm2. Specifically, hydrogen output decreased from 46.6 to 0 µM/min as the CO2 percentage increased from 0 % (pure argon) to 0.07 % (Fig. 6a). Similarly, the hydrogen generation rate decreased from 360 to 30 µM/min as the percentage of N2O increased from 0 % (pure argon) to 4 %. This decrease was attributed to argon's superior characteristics as a saturating gas. These characteristics include a low thermal conductivity, high polytropic index, and comparatively high solubility (2.748 × 10−5 mol/mol). This solubility is higher than that of air and N2, which is 1.524 × 10−5 mol/mol. Argon's high bubble temperature promotes the generation of hydrogen from the gaseous phase within the acoustic bubble. Merouani et al. [[96], [97], [98]] have mathematically demonstrated that this effect increases with higher irradiation frequencies (20–1000 kHz).

Fig. 6.

Yields of different products obtained by water ultrasonication under an Ar-CO2 atmosphere as function of the CO2 mole fraction (ultrasonication time: 15 min) [95] (a), acoustic cavitation activity in water under different dissolved gases ultrasonicated by a Sinaptec transducer (20 kHz at 50 % acoustic amplitude) [102] (b).

The nullifying impact of CO2 and N2O is attributed to their high-water solubility (7.07 × 10−4 for CO2 and 5.068 × 10−4 for N2O), which suppresses inertial cavitation [99,100]. Inertial cavitation is producing the chemical impacts of ultrasonication. Larger, visible bubbles caused by bubble coalescence are reported when CO2 is employed as the saturating gas. In contrast, argon, air, and nitrogen produce invisible, microscopic bubbles (Fig. 6b) [101,102]. This suggests that high CO2 solubility encourages bubble coalescence, thereby suppressing the bubbles' sonochemical activity [103].

5.4. pH

Anbar and Pecht [104] examined the effect of pH on hydrogen generation at 800 kHz in aqueous formate solutions. They concluded that formate did not affect acoustic hydrogen production because the yield was the same in pure water as in the 25 µM formate solution (25 µM/min). This result suggests that hydrogen is not created by the autorecombination of H• radicals because formate is a potent H• scavenger. Subsequent investigations revealed that the production rate decreased from 25 µM/min at pH 6–12 to 16.2 µM/min at pH 0.6, indicating that hydrogen output increases with pH. Similarly, Xuemin et al. [105] demonstrated that methanol ultrasonication in diluted aqueous solutions yielded higher hydrogen generation rates under neutral conditions than under acidic ones. According to Ashokkumar et al. [106], sonoluminescence intensity increased with pH until reaching pH 10, after which it plateaued. Higher pH levels encourage higher bubble temperatures, which increase hydrogen generation because sonoluminescence intensity correlates with the bubble's peak temperature [107]. Thus, as the pH changes from acidic to neutral, the hydrogen output obtained via ultrasonication increases.

5.5. Temperature

Rassokhin et al. [67] investigated the influence of water-methanol mixes with diverse methanol content on the generation of hydrogen via ultrasonication at diverse liquid temperatures varying from –30 to 50 °C under 724 kHz and 50 W conditions (Fig. 7). The rate of hydrogen formation in pure water increased with temperature, peaking at 14 µM/min between 5 and 50 °C. However, the production rate of hydrogen in methanol–water mixtures was much higher than in pure water, peaking at temperatures that varied according to the amount of methanol present. As the methanol concentration decreased, all the curves shifted toward higher temperatures, including their peak points. This resulted in less noticeable temperature dependence. Formation rates and ideal temperatures also depended on the methanol dose. Maximal formation rates occurred under the following conditions: 100, 200, 170, 50 µM/min at 0.18 % methanol and 35 °C, 1.8 % methanol and 25 °C, 11 % methanol and 25 °C, and 25 % methanol and 20 °C, respectively. However, the rate of hydrogen formation diminished at methanol concentrations higher than 60 %. Xuemin et al. [105] observed similar patterns of hydrogen generation rates proportional to temperature and methanol concentration during ultrasonication at 40 kHz.

Fig. 7.

The temperature dependencies of hydrogen production rate in the ultrasonication of methanol–water mixtures with different mole fractions of methanol. Mole fractions of methanol for each curve are indicated in the legends enclosed in the plot area [67].

5.6. Static pressure

As demonstrated by Cotana et al. [108], static pressure significantly affects hydrogen production during ultrasonication. After three hours of irradiation at 20 kHz and 100 W using two transducers, the hydrogen concentration diminished from 7.32 to 6.82 and 3.65 µM at 1, 1.5 and 2.5 atm, respectively. These results align with those of sonolytic oxidation of KI and sonoluminescence, which revealed that one atmosphere is the optimal functioning pressure for sonoluminescence and sonochemistry [89,109,110].

Similarly, Dehane et al. [111] found via computational simulations that the hydrogen yield from an individual bubble diminished as the static pressure increased from 0.3 to 3 atm at 500 kHz. According to Merouani et al. [112], the output of an individual bubble approaches atmospheric pressure. Generally, augmenting the static pressure over 1 atm successfully lowers acoustic intensity, resulting in reduced bubble pressures and temperatures [112,113]. Conversely, bubble temperatures are considerably lower at pressures below 0.5 atm. An ideal static pressure of around 1 atm optimizes bubble temperature and chemical yields between these two extremes [112,114].

6. Adversity and prospective perspectives

The most important obstacles to the widespread utilization of ultrasonication for hydrogen generation are the low energy conversion efficiency of existing transducers and the difficulty of scaling up sonoreactors. The design of the sonoreactor, including the transducers and the arrangement of the reaction chamber, directly impacts the efficiency of ultrasonication processes [115,116]. Researchers are expanding the range of ultrasonication applications and making significant efforts to overcome the challenges of scaling up these processes for commercial use. Although sonolytic methods are widely used in laboratories, they are rarely used in large-scale ultrasonication reactors. The heavy emphasis in the literature on laboratory-sized reactors hinders the application of this information to the design and implementation of reactors suitable for producing hydrogen on an industrial scale [[117], [118], [119]].

To identify significant obstacles in the conceptualization and implementation of large-scale sonolytic reactors, several factors must be examined [120]:

-

•

Dissemination of Cavitation Activity: An uneven cavitational activity distribution can result in significant dead zones that affect overall reactor production, especially in large-scale operations. Operating parameters, such as frequency and power, impact cavitational activity. This activity tends to be focused around horn tips at lower frequencies and nearer to the liquid surface at higher frequencies.

-

•

Attenuation of ultrasound in large liquid heights: High liquid heights in large-scale treating systems encounter attenuating ultrasonic waves, especially when transducers are positioned vertically. This reduces mixing efficiency and increases treatment costs. Additionally, large operating heights significantly decrease ultrasound wave strength, creating dead zones that require higher electrical voltages to achieve adequate acoustic amplitudes.

-

•

High ultrasonication treatment electrical cost: Transducers are less effective at converting electrical power into mechanical vibration. This makes treating great volumes, particularly in batch operation, expensive. The transducers' inefficiency in transforming electrical power into mechanical vibration causes this problem.

To address these issues, researchers recommend using multiple transducers in sonoreactors. For large-scale procedures, they suggest using transducers with different frequencies. Transducers offer benefits in both batch and continuous operating systems. They can be placed on sonoreactor walls or submerged in liquid. Additionally, optimizing the reaction zone and reactor performance involves operating transducers at different frequencies and power levels.

The following advantages are generally offered by various transducer configurations [120]:

-

•

Homogeneous cavitation activity is achieved by adjusting the frequency and power of a transducer or group of transducers. This optimizes mixing and eliminates dead zones.

-

•

To minimize attenuation of ultrasonic wave, the effective action region of each transducer is maximized by arranging multiple rows of transducers along the sonoreactor walls.

-

•

In a multiple-transducer setup, each transducer has its own action zone. This enables them to operate for extended periods without consuming excessive electrical power.

-

•

The continuous operating mode enables uninterrupted operation, aligning with the industry's demand for large-scale wastewater treatment.

Fig. 8a [121] illustrates a standard multi-transducer configuration intended for sonochemical applications. The cylindrical sonoreactor vessel operates at frequencies ranging from 21 to 140 kHz while maintaining a regulated temperature. The vessel has a maximum capacity of approximately 18 L, is made of a 2-mm-thick stainless-steel plate, a maximum water depth of 2.97 cm, and an internal diameter of 26.9 cm. The system's 21 Tonpilz transducers are organized in 3 rows of 7 transducers of various sizes that are evenly spaced. This configuration guarantees an equal depth increase between the water surface and the vessel's bottom at its maximum level. Each row operates at up to 150 W of design power.

Fig. 8.

Multifrequency ultrasonication vessel with three rows of transducers (a) and SCL inside the sonoreactor at 21 (left) and 44 kHz (right) (b) [121].

Fig. 8b shows SCL images taken from a water-filled sonoreactor running at 100 W with a 1 min exposure time. These images reveal cavitation fields at 21 and 44 kHz. The cavitation field appears brighter, wider, and more evenly dispersed at 44 kHz than at 21 kHz. However, the center peak at 44 kHz is smaller. In contrast, the core area at 21 kHz is wider and more prominent and is surrounded by secondary peaks. These discrepancies highlight the frequency- and intensity-dependent dispersion of the sonoreactor's cavitational activity.

A hexagonal flow cell functioning at triple-frequency with 7.5 L of total working capacity was investigated by Gogate et al. [117]. The cell can be used for either batch or continuous operations. It has seven distinct frequency combinations, including single-, dual-, and triple-frequency modes. The cell contains 18 transducers, with three on each hexagonal face. Studies employing Rhodamine B dye degradation and KI dosimetry revealed considerably higher cavitation yields and greater energy efficiency than classical sonoreactor designs. A thorough investigation of the cavitation activity distribution used hydrophone measurements of local pressure and a cavitation activity indication to determine intensity levels. The investigation revealed uniform cavitation throughout the liquid bulk [122]. This uniformity exhibited only 10–30 % variation, as opposed to the much higher 80–400 % variation found in conventional horn-type sonoreactors [122].

Gogate and Patil [123] argue that a multiple transducer reactor with a flow cell layout is the optimal solution for viable applications. This configuration has been shown to effectively facilitate crystallization and water treatment. However, it is imperative to notice that operating costs augment with the number of transducers in the reactor. Therefore, when designing a sonoreactor, balancing cost-effectiveness and sonoreactor performance is essential. Factors to consider include cavitation distribution homogeneity, mixing duration, mass transfer, and flow pattern.

7. Conclusion

Hydrogen generation by ultrasonication is considered a talented substitute for producing clean, inexpensive, nontoxic energy. The debate surrounding this process has highlighted several important factors impacting the energy efficiency of hydrogen production via ultrasonication. While increasing the frequency generally increases hydrogen output, the ideal frequency for optimal generation has yet to be determined, unlike with hydrogen peroxide. Similarly, the efficiency of hydrogen production through ultrasonication improves with increases in liquid temperature and ultrasonic amplitude. However, because precise management of these factors is necessary to maximize hydrogen generation, these gains are inconsistent.

Furthermore, research has shown that hydrogen output can be significantly increased with low concentrations of alcohols (e.g., methanol and ethanol) and hydrocarbons, such as methane, ethane, and acetylene. Despite these findings, additional research is necessary to determine the precise optimal operating parameters. These parameters include liquid temperature, dissolved gas concentrations, acoustic strength, and ultrasonication frequency. This research is necessary to improve process control and consistency.

Compared to ultrasonication, US/catalysis has demonstrated increased hydrogen production. However, the effectiveness of US/photolytic and US/photocatalytic processes remains questionable compared to ultrasonication or US/catalytic techniques. Therefore, targeted studies on the processes underlying US/catalysis, US/photolysis, and US/photocatalysis, as well as the variables affecting their effectiveness, are crucial. This will advance our knowledge and ultimately increase the efficiency of various hydrogen production techniques.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Slimane Merouani: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Aissa Dehane: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Oualid Hamdaoui: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research and Innovation, “Ministry of Education” in Saudi Arabia for funding this research (IFKSU-HCRA-6-1).

References

- 1.Chakraborty S., Dash S.K., Elavarasan R.M., Kaur A., Elangovan D., Meraj S.T., Kasinathan P., Said Z. Hydrogen Energy as Future of Sustainable Mobility. Front. Energy Res. 2022;10–2022 https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/energy-research/articles/10.3389/fenrg.2022.893475 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norouzi N. Future of hydrogen in energy transition and reform. J. Chem. Lett. 2021;2:64–72. doi: 10.22034/jchemlett.2021.301002.1036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filippov S.P., Yaroslavtsev A.B. Hydrogen energy: development prospects and materials. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2021;90:627. doi: 10.1070/RCR5014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dincer I., Acar C. ScienceDirect review and evaluation of hydrogen production methods for better sustainability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2014;40:11094–11111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.12.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haryanto A., Fernando S., Murali N., Adhikari S. Current Status of Hydrogen Production Techniques by Steam Reforming of Ethanol. A Review, Energy & Fuels. 2005;19:2098–2106. doi: 10.1021/ef0500538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dincer I. Green methods for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2011;37:1954–1971. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.03.173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dincer I., Acar C. Innovation in hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42:14843–14864. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.04.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaddami M., Mikou M., Ezzahra Chakik F., Kaddami M., Mikou M. ScienceDirect effect of operating parameters on hydrogen production by electrolysis of water. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ni M., Leung D.Y.C., Sumathy K. A review and recent developments in photocatalytic water-splitting using TiO2 for hydrogen production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007;11:401–425. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2005.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das D., Veziroglu T.N. Advances in biological hydrogen production processes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2008;33:6046–6057. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.07.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel S.K., Gupta R.K., Rohit M.V., Lee J.-K. Recent developments in hydrogen production, storage, and transportation: challenges, opportunities, and perspectives. Fire. 2024;7:233. doi: 10.3390/fire7070233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dash S.K., Chakraborty S., Elangovan D. A brief review of hydrogen production methods and their challenges. Energies. 2023;16:1141. doi: 10.3390/en16031141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song H., Luo S., Huang H., Deng B., Ye J. Solar-Driven hydrogen production: recent advances challenges, and future perspectives. ACS Energy Lett. 2022;7:1043–1065. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.1c02591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lv L., Song S. The effects of dynamic factors inside the bubble on sono-hydrogen yield: a numerical study. AIP Adv. 2024;14 doi: 10.1063/5.0234338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D. Symes, Sonoelectrochemical (20 kHz) Production of Hydrogen from Aqueous Solutions, Master Thesis, University of Birmingham (2011).

- 16.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O. The sonochemical approach for hydrogen production, sustain. Green Chem. Process. Their Allied Appl. Nanotechnol Life Sci. 2020:1–29. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-42284-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.J.A. Gallego-Juarez, K.F. Graff, M. Lucas, Power ultrasonics, Applications of High-Intensity Ultrasound, Woodhead Publishing, 2nd edition,2023.

- 18.Zadeh S.H. Hydrogen Production via Ultrasound-aided Alkaline Water Electrolysis. J. Autom. Control Eng. 2014;2:103–109. doi: 10.12720/joace.2.1.103-109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gentili P.L., Penconi M., Ortica F., Cotana F., Rossi F., Elisei F. Synergistic effects in hydrogen production through water sonophotolysis catalyzed by new La2xGa2yIn2(1-x-y)O3 solid solutions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2009;34:9042–9049. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. Mechanism of the sonochemical production of hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2015;40:4056–4064. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.01.150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.K. Yasui, Bubble Dynamics, in: Acoust. Cavitation Bubble Dyn., Springer, 2018: pp. 37–97. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-68237-2_2.

- 22.Ashokkumar M., Lee J., Iida Y., Yasui K., Kozuka T., Tuziuti T., Towata A. The detection and control of stable and transient acoustic cavitation bubbles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:10118–10121. doi: 10.1039/b915715h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasui K. Acoustic Cavitation BT - Acoustic Cavitation and Bubble Dynamics. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2018. pp. 1–35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mettin R., Cairós C., Troia A. Sonochemistry and bubble dynamics. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;25:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.J. Luo, Z. Fang, R.L. Smith, X. Qi, Fundamentals of Acoustic Cavitation in Sonochemistry BT - Production of Biofuels and Chemicals with Ultrasound, in: Z. Fang, J. Smith Richard L., X. Qi (Eds.), Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, (2015) pp. 3–33. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9624-8_1.

- 26.Yasui K., Tuziuti T., Lee J., Kozuka T., Towata A., Iida Y. The range of ambient radius for an active bubble in sonoluminescence and sonochemical reactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128 doi: 10.1063/1.2919119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.K. Yasui, Chapter 3 - Dynamics of Acoustic Bubbles, in: F. Grieser, P.-K. Choi, N. Enomoto, H. Harada, K. Okitsu, K.B.T.-S., A.B. Yasui (Eds.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, (2015) pp. 41–83. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801530-8.00003-7.

- 28.Laborde J.-L., Bouyer C., Caltagirone J.-P., Gérard A. Acoustic bubble cavitation at low frequencies. Ultrasonics. 1998;36:589–594. doi: 10.1016/S0041-624X(97)00105-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suslick K.S., Eddingsaas N.C., Flannigan D.J., Hopkins S.D. The chemical history of a bubble. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018;51:2169–2178. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anbar M., Pecht I. On the sonochemical formation of hydrogen peroxide in Water. J. Phys. Chem. 1964;68:352–355. doi: 10.1021/j100784a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hart E.J., Henglein A. Sonochemistry of aqueous solutions: H2-O2 combustion in cavitation bubbles. J. Phys. Chem. 1987;91:3654–3656. doi: 10.1021/j100297a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer C., Hart E., Henglein A. Ultrasonic irradiation of water in the presence of 18,18O2: isotope exchange and Isotopic distribution of H2O2. J. Phys. Chem. 1986:1954–1956. doi: 10.1021/j100400a043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yusof N.S.M., Anandan S., Sivashanmugam P., Flores E.M.M., Ashokkumar M. A correlation between cavitation bubble temperature, sonoluminescence and interfacial chemistry – a minireview. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;85 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.105988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashokkumar M., Lee J., Kentish S., Grieser F. Bubbles in an acoustic field: an overview. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2007;14:470–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yasui K., Tuziuti T., Sivakumar M., Iida Y. Theoretical study of single-bubble sonochemistry. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;122 doi: 10.1063/1.1925607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hart E.J., Fischer C.-H., Henglein A. Isotopic exchange in the sonolysis of aqueous solutions containing nitrogen-14 and nitrogen-15 molecules. J. Phys. Chem. 1986;90:5989–5991. doi: 10.1021/j100280a104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer C.-H., Hart E.J., Henglein A. H/D isotope exchange in the D2-H2O system under the influence of ultrasound. J. Phys. Chem. 1986;90:222–224. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hart E.J., Fischer C., Henglein A. Pyrolysis of Acetylene In Sonolytic Cavitation Bubbles in Aqueous Solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1990;94:284–290. doi: 10.1021/j100364a047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biittner J., Gutierrez M., Henglein A., Buttner J., Gutierrez M., Henglein A., Buettner J., Gutierrez M., Henglein A., Biittner J., Gutierrez M., Buttner J., Gutierrez M., Henglein A., Biittner J., Gutierrez M. Sonolysis of water-methanol mixtures. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:1528–1530. doi: 10.1021/j100157a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sasikala R., Jayakumar O.D., Kulshreshtha S.K. Enhanced hydrogen generation by particles during sonochemical decomposition of water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2007;14:153–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi J., Yoon S., Son Y. Effects of alcohols and dissolved gases on sonochemical generation of hydrogen in a 300 kHz sonoreactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;101 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hart E.J., Fischer C.H., Henglein A. Sonolysis of hydrocarbons in aqueous solution. Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instrumentation. Part C. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1990;36:511–516. doi: 10.1016/1359-0197(90)90198-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dehane A., Nemdili L., Merouani S., Ashokkumar M. Critical analysis of hydrogen production by aqueous methanol sonolysis. Top. Curr. Chem. 2023;381:9. doi: 10.1007/s41061-022-00418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.A. Dehane, S. Merouani, Sonochemical Production of Hydrogen: A Green and Sustainable Approach, in: Sankar Chakma (Ed.), Ultrasound Technol. Fuel Process., Bentham Science Publishers, (2024) pp. 35–59.

- 45.Rashwan S.S., Dincer I., Mohany A., Pollet B.G. The Sono-Hydro-Gen process (Ultrasound induced hydrogen production): challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2019;44:14500–14526. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.04.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asgharzadehahmadi S., Aziz A., Raman A., Parthasarathy R. Sonochemical reactors : review on featuresadvantages and limitation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016;63:302–314. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.05.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gogate P.R., Wilhelm A.M., Pandit A.B. Some aspects of the design of sonochemical reactors. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2003;10:325–330. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(03)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sutkar V.S., Gogate P.R. Design aspects of sonochemical reactors: Techniques for understanding cavitational activity distribution and effect of operating parameters. Chem. Eng. J. 2009;155:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2009.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yasui K., Tuziuti T., Iida Y. Dependence of the characteristics of bubbles on types of sonochemical reactors. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2005;12:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fattahi K., Robert E., Boffito D.C. Numerical and experimental investigation of the cavitation field in horn-type sonochemical reactors. Chem. Eng. Process. - Process Intensif. 2022;182 doi: 10.1016/j.cep.2022.109186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rahimi M., Movahedirad S., Shahhosseini S. CFD study of the flow pattern in an ultrasonic horn reactor: introducing a realistic vibrating boundary condition. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;35:359–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Renaudin V., Gondrexon N., Boldo P., C P., Bernis A., Y G. Method for determining the chemically active zones in a high-frequency ultrasonic reactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1994;1:3–7. doi: 10.1016/1350-4177(94)90002-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pétrier C., Gondrexon N., Boldo P. Ultrasons et sonochimie. Tech. L’ingénieur. 2008:16. AF6310. [Google Scholar]

- 54.P. Choi, Fundamental aspects of acoustic field, cavitation ans sonoluminescence, in: M. Ashokkumar (Ed.), Handb. Ultrason. Sonochemistry, Springer Science+Business Media, Singapore, 2015: pp. 1–29, doi: 10.1007/978-981-287-470-2_2–1. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-470-2.

- 55.Son Y., Lim M., Khim J., Kim L., Ashokkumar M. Comparison of calorimetric energy and cavitation energy for the removal of bisphenol-a : the effects of frequency and liquid height. Chem. Eng. J. 2012;183:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2011.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Son Y., Lim M., Ashokkumar M., Khim J. Geometric optimization of sonoreactors for the enhancement of sonochemical activity. J. Phys. Chem. 2011;115:4096–4103. doi: 10.1021/jp110319y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kimura T., Sakamoto T., Leveque J.M., Sohmiya H., Fujita M., Ikeda S., Ando T. Standardization of ultrasonic power for sonochemical reaction. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1996;3:4. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(96)00021-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Saoudi F., Chiha M. Influence of experimental parameters on sonochemistry dosimetries: KI oxidation, Fricke reaction and H2O2 production. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010;178:1007–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mason T.J., Lorimer J.P. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; KGaA Weinheim, Gu: 2002. Applied sonochemistry the uses of power ultrasound in chemistry and processing. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hua I., Hoffmann M.R. Optimization of ultrasonic irradiation as an advanced oxidation technology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1997;31:2237–2243. doi: 10.1021/es960717f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferkous H., Hamdaoui O., Christian P. Sonochemical reactor characterization in the presence of cylindrical and conical reflectors. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;99:106556. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De La Rochebrochard S., Suptil J., Blais J.F., Naffrechoux E. Sonochemical efficiency dependence on liquid height and frequency in an improved sonochemical reactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2012;19:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Asakura Y., Nishida T., Matsuoka T., Koda S. Effects of ultrasonic frequency and liquid height on sonochemical efficiency of large-scale sonochemical reactors. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008;15:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anbar M., Pecht I. The sonolytic decomposition of organic solutes in dilute aqueous solutions. I. Hydrogen abstraction from Sodium formate. J. Phys. Chem. 1964;68:1460–1462. doi: 10.1021/j100788a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hart E.J., Henglein A. Free radical and free atom reactions in the sonolysis of aqueous iodide and formate solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 1985;89:4342–4347. doi: 10.1021/j100266a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guitièrrres M., Heinglein A., Fischer C.-H. Hot spot kinetics of the sonolysis aqueuos acetate solutions. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Physics, Chem. Med. 1986;50:313–321. doi: 10.1080/09553008614550691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rassokhin D.N., Kovalev G.V., Bugaenko L.T. Temperature effect on the sonolysis of methanol/water mixtures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:344–347. doi: 10.1021/ja00106a037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morosini V., Chave T., Virot M., Moisy P., Nikitenko S.I. Sonochemical water splitting in the presence of powdered metal oxides. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;29:512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Y., Zhao D., Ji H., Liu G., Chen C., Ma W., Zhu H., Zhao J. Sonochemical hydrogen production efficiently catalyzed by Au / TiO2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010;114:17728–17733. doi: 10.1021/jp105691v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wong C.C.Y., Preso D.B., Qin Y., Sinhmar P.S., Zong Z., Kwan J. Ultrasound-driven seawater splitting catalysed by TiO2 for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2025;111:723–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2025.02.327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Y., Khanbareh H., Dunn S., Bowen C.R., Gong H., Duy N.P.H., Phuong P.T.T. High efficiency water splitting using ultrasound coupled to a BaTiO3 nanofluid. Adv. Sci. 2022;9:1–11. doi: 10.1002/advs.202105248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Teoh Y.H., Soon P.H., How H.G., Yaqoob H., Idroas M.Y., Jamil M.A., Mahmud S.U., Le T.D., Ali H.M., Shahzad M.W. Optimization of catalyst for electrolysis and sono-electrolysis process for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2025;157:150508. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2025.150508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mondal S., Dilly Rajan K., Patra L., Rathinam M., Ganesh V. Sulfur vacancy-induced enhancement of piezocatalytic H2 production in MoS2. Small. 2025;21 doi: 10.1002/smll.202411828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rashwan S.S., Dincer I., Mohany A. A review on the importance of operating conditions and process parameters in sonic hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46:28418–28434. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.06.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Foroughi F., Lamb J.J., Burheim O.S., Pollet B.G., Faranak F., Lamb J.J., Burheim O.S., Pollet B.G., Foroughi F., Lamb J.J., Burheim O.S., Pollet B.G. Sonochemical and sonoelectrochemical production of energy materials. Catalysts. 2021;11:284. doi: 10.3390/catal11020284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Navarro N.M., Chave T., Pochon P., Bisel I., Nikitenko S.I. Effect of Ultrasonic Frequency on the Mechanism of Formic Acid Sonolysis. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:2024–2029. doi: 10.1021/jp109444h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pflieger R., Ndiaye A.A., Chave T., Nikitenko S.I. Influence of ultrasonic frequency on swan band sonoluminescence and sonochemical activity in aqueous tert-butyl alcohol solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:284–290. doi: 10.1021/jp509898p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beckett M.A., Hua I. Impact of ultrasonic frequency on aqueous sonoluminescence and sonochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:3796–3802. doi: 10.1021/jp003226x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Torres R.A., Pe C., Pulgarin C., Pétrier C., Combet E., Carrier M., Pulgarin C. Ultrasonic cavitation applied to the treatment of bisphenol a . effect of sonochemical parameters and analysis of BPA by-product. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008;15:605–611. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pétrier C., Francony A. Ultrasonic waste-water treatment: incidence of ultrasonic frequency on the rate of phenol and carbon tetrachloride degradation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1997;4:295–300. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(97)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jiang Y., Petrier C., Waite T.D. Sonolysis of 4-chlorophenol in aqueous solution: effects of substrate concentration, aqueous temperature and ultrasonic frequency. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2006;13:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. Computational engineering study of hydrogen production via ultrasonic cavitation in water. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2015;41:832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.11.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dehane A., Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Alghyamah A. A complete analysis of the effects of transfer phenomenons and reaction heats on sono- hydrogen production from reacting bubbles : Impact of ambient bubble size. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46:18767–18779. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.03.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dehane A., Merouani S., Hamdaoui O. Bubbles counting using organic pollutants degradation as a probe. J. Eng. Res. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.jer.2024.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dehane A., Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Ashokkumar M. An alternative technique for determining the number density of acoustic cavitation bubbles in sonochemical reactors. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;82 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.L. Venault, De l’influence des ultrasons sur la réactivité de l’uranium (U(IV)/U(VI)) et du plutonium (Pu(lll)/Pu(IV)) en solution aqueuse nitrique, PhD thesis, Université Paris sud, (1997).

- 87.Guzman-duque F., Pétrier C., Pulgarin C., Peñuela G., Torres-palma R.A. Effects of sonochemical parameters and inorganic ions during the sonochemical degradation of crystal violet in water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011;18:440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Henglein A. Chemical effects of continuous and pulsed ultrasound in aqueous solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1995;2:115–121. doi: 10.1016/1350-4177(95)00022-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Henglein A., Gutierrez A., Gutierrez M. Sonochemistry and sonoluminescence: effects of external pressure. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:158–162. doi: 10.1021/j100103a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Henglein A. Sonochemistry: historical developments and modern aspects. Ultrasonics. 1987;25:6–16. doi: 10.1016/0041-624X(87)90003-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ferkous H., Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. Comprehensive experimental and numerical investigations of the effect of frequency and acoustic intensity on the sonolytic degradation of naphthol blue black in water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;26:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kanthale P., Ashokkumar M., Grieser F. Sonoluminescence, sonochemistry (H2O2 yield) and bubble dynamics: Frequency and power effects. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008;15:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sunartio D., Ashokkumar M., Grieser F. Study of the coalescence of acoustic bubbles as a function of frequency, power, and water-soluble additives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6031–6036. doi: 10.1021/ja068980w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gutierrez M., Henglein A. Radical scavenging in the sonolysls of aqueous solutions of I-, Br-, and N3- J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:6044–6047, doi: 10.1021/j100168a061. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Henglein A. Sonolysis of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane in aqueous solution. Zeitschrift Für Naturforsc B. 1985:100–107. doi: 10.1515/znb-1985-0119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry Sensitivity of free radicals production in acoustically driven bubble to the ultrasonic frequency and nature of dissolved gases. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;22:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Merouani S., Ferkous H., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. New interpretation of the effects of argon-saturating gas toward sonochemical reactions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;23:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dehane A., Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Alghyamah A. Insight into the impact of excluding mass transport, heat exchange and chemical reactions heat on the sonochemical bubble yield : bubble size-dependence. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;73 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kerabchi N., Merouani S., Hamdaoui O. In: Water Eng. Model. Math. Tools. Samui P., Bonakdari H., Deo R., editors. Elsevier; 2021. Computer simulation of N2O/argon gas mixture effect on the acoustic generation of hydroxyl radicals in water: toward understanding the mechanism of N2O inhibited/improved-sonochemical processes; pp. 87–114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Al-Zahrani S.M. Toward understanding the mechanism of pure CO2-quenching sonochemical processes. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020;95:553–566. doi: 10.1002/jctb.6227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rooze J., Rebrov E.V., Schouten J.C., Keurentjes J.T.F. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry effect of resonance frequency , power input , and saturation gas type on the oxidation efficiency of an ultrasound horn. Ultrason. Sonochemistry. 2011;18:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kerboua K., Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Alghyamah A., Islam H., Hansen H.E., Pollet B.G. How do dissolved gases affect the sonochemical process of hydrogen production ? an overview of thermodynamic and mechanistic effects – on the “ hot spot theory. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;72 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chadi N.E., Merouani S., Hamdaoui O. Characterization and application of a 1700 kHz-acoustic cavitation field for water decontamination: a case study with toluidine blue. Appl. Water Sci. 2018;8(160):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s13201-018-0809-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Anbar M., Pecht I. On the sonochemical formation of hydrogen peroxide in water. J. Phys. Chem. 1963;68:1959–1962. doi: 10.1021/j100784a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]