Abstract

Osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (OVCF) have emerged as a significant public health concern. Traditionally, poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) has been utilized in clinical to treat OVCF. Nevertheless, its poor degradability, uncontrollable setting time, high curing temperatures, and the potential for cement leakage have limited their application. In addition, these bone cements required clinical handling, bringing inconvenience to surgery.This study developed a premixed magnesium phosphate bone cement loaded with strontium ranelate and bioglass microspheres grafted with alendronate sodium (pTMPC-SMA), to achieve regulation between osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis on osteoporosis. The premixed cement offered storage stability, easy of use, anti-washout behavior, and sustained drug release properties. The in vivo osteoporotic rabbit vertebroplasty model demonstrated that pTMPC-SMA exhibited excellent cavity-filling adaptability, significantly enhanced new bone formation, and achieved superior osseointegration compared to the PMMA group. These findings demonstrate that pTMPC-SMA provides both excellent handling properties and osteogenic therapeutic advantages for treating osteoporosis-related bone defects.

Keywords: Bone cement, Osteoporosis, Bone homeostasis, Vetebroplasty, Bone defects

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A drug-loaded premixed bone cement pTMPC-SMA has been developed.

-

•

pTMPC-SMA has the properties of ready-to-use, disintegration resistance, and cured upon contact with body fluids.

-

•

pTMPC-SMA achieved long-term drug release, inhibiting osteoclast activity and enhancing osteoblast activity.

-

•

pTMPC-SMA demonstrated effective filling performance in vertebroplasty procedures in osteoporotic rabbit models.

-

•

pTMPC-SMA showed significant new bone formation compared to the PMMA group, with the new bone integrating with the material.

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis poses a significant threat to the physical and mental well-being of middle-aged and elderly individuals, emerging as a pressing public health concern amidst the global aging phenomenon [1]. Among its myriad complications, osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture (OVCF) stands out as the most prevalent, precipitating a cascade of adverse effects including back pain, respiratory impairment, spinal cord injury, hunchback deformity, insomnia, depression, and a notable mortality risk. Percutaneous vertebroplasty (PVP) and balloon kyphoplasty (BKP) are effective treatments for OVCF. Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) bone cement is used to fill bone defect and restore vertebral height. In recent years, increasing studies have reported the disadvantages of using PMMA to treat OVCF, including cement leakage, secondary vertebral fractures, heat release, toxicity, and poor osseointegration. These problems cause pain, tissue death, and implant loosening to affect the treatment ultimately. In order to solve the issues of PMMA, researchers have developed composite PMMA bone cement, and inorganic bone cement, e.g. calcium phosphate bone cement (CPC) and magnesium phosphate cement (MPC). Magnesium-based materials have emerged as a research hotspot in recent years owing to magnesium's promotional effects on vascular, neural, and bone regeneration [2,3]. Compared with CPC, MPC has attracted significant attention in the field of bone defect repair materials due to its superior mechanical properties and degradation performance, which have been extensively investigated in recent years [4]. However, their operability and bioactivity still fail to meet clinical needs [5,6]. The development of functionalized derivatives based on magnesium phosphate cement (MPC), leveraging its inherent degradability and biocompatibility, presents promising application prospects in biomedical engineering.

Bone cement is an injectable and self-setting material that can fill complex and irregular bone defects, making it a highly popular choice in clinical applications. The handling characteristics of bone cement are critical in PVP surgery. Within the limit of our knowledge, the most conventionally used bone cements, the setting process begins immediately after the mixing of powder and liquid. Although the setting mechanism is different from PMMA and inorganic bone cement, the operation temperature greatly affects the injection performance and setting time, which results in the need for an experienced person to handle cement [[7], [8], [9]]. Elevated ambient temperature significantly decreases the setting time of PMMA bone cement, necessitating clinical handling below 23 °C [10]. Conventional bone cements require on-site preparation during the procedure and application within a limited timeframe. Premixed bone cement, a slurry formed by mixing powder with a dispersant, presents a promising solution to persistent challenges such as cement leakage, suboptimal setting properties, and limited osteogenic capacity, while offering long-term storage stability and favourable application prospects [11]. Long-term preserved paste can be obtained by using biocompatibility dispersants, such as, glycerol, triglyceride, and polyethylene glycol [7]. Triglyceride caprylate capric acid (GTCC) has been widely used in cosmetics industry possesed biocompatibility which also has been used in the development of premixed bone cement [[12], [13], [14]]. The excellent biocompatibility ensured the safety of GTCC in vivo application. Previous studies prepared CPC bone cements with the addition of GTCC, which had excellent curing properties, thus confirming GTCC as a promising dispersant [13,14]. The retarded setting time of the premixed cement is a promising solution to the problem of unstable bone cement setting. At present, premixed bone cement based on GTCC and hydroxyapatite has been used in the clinic [15].

Due to the limited osteogenic capacity associated with osteoporosis, OVCF patients often need medication-assisted therapy to restore vertebral strength [16]. Commonly used osteoporosis drugs include parathyroid hormone (PTH), bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), alendronate sodium, strontium ranelate, etc., which require periodic long-term oral or intravenous injections [17]. Systemic administration of drugs has low utilization and is prone to complications. Especially with bisphosphonates, their specific binding to bone tissue, combined with long-term systemic use, can lead to osteonecrosis [18]. Furthermore, suboptimal drug concentrations at the lesion site impede rapid reestablishment of the regenerative microenvironment. Drug loading in implants to achieve in situ drug delivery is an efficient way. However, achieving long-term sustained release is challenging with PMMA bone cement and CPC bone cement due to their lack of degradability [19]. While drug-loaded PMMA has been investigated, its exothermic polymerization process can denature thermolabile pharmaceuticals. In contrast, biodegradable bone cements like MPC and CPC enable cold setting and achieve sustained drug release properties shown to enhance therapeutic outcomes in osteoporotic fracture defects [20,21]. Considering the stability of therapeutic agents, parathyroid hormone (PTH) or bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) biologics generally exhibit short shelf-life and susceptibility to inactivation [22], whereas salt-form drugs such as, bisphosphonates and strontium ranelate demonstrate superior stability that facilitates sustained release profiles in drug delivery systems. Meanwhile, these two drugs are representative clinical drugs that inhibit bone resorption and promote bone formation, respectively [23,24]. Bioglass, with high specific surface area, serves as an ideal drug delivery vehicle. Grafting alendronate sodium onto bioactive glass enables sustained low-dose drug release, thereby mitigating bisphosphonate-associated complications [18,21]. Based on the characteristics of these drugs, this study selected alendronate grafted bioglass and strontium ranelate, and loaded them into magnesium phosphate bone cement to modulate the bone homeostasis.

Based on the high-strength trimagnesium phosphate cement, this study has developed a premixed magnesium phosphate bone cement (pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA) with injectability and bioactivity. The pTMPC-SMA bone cement is composed of trimagnesium phosphate bone cement, biocompatible oily dispersants (GTCC), and pharmaceuticals, and can be stored under dry conditions, ready for immediate use (Fig. 1). By incorporating alendronate sodium-loaded bioglasses, and strontium ranelate, the premixed bone cement achieved sustained drug release and regulation of bone homeostasis. After injection, the cement could solidify in aqueous environment through oil-water exchange. The degradability of magnesium phosphate cement allowed for the gradual release of drugs during the material's degradation process, promoting osteogenesis and mineralization while inhibiting bone resorption. We applied this cement to an osteoporosis rabbit model and performed PVP surgery. After 12 weeks of implantation, the bone cement integrated well with the surrounding bone tissue compared to the PMMA group. Additionally, the drug-loaded group demonstrated significant new bone formation and an improved osteoporotic pathological environment.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of constructing ready-to-use premixed bone cement. Bioglass spheres (BG) loaded with alendronate sodium (AS), strontium ranelate (SrR), and trimagnesium phosphate bone cement powder were mixed with glyceryl tributyrate citrate (GTCC) as a dispersing agent to obtain pTMPC-SMA bone cement. pTMPC-SMA could inhibited the osteoclast differential through TNF and OPG/RANK/RANKL pathways. The release of alendronate sodium directly inhibited osteoclast activity. Strontium ranelate could promoted osteoblast differentiation and enhanced OPG expression, thereby blocking the binding of RANKL to RANK and reducing osteoclast differentiation. Percutaneous vertebroplasty (PVP) surgery was conducted successfully on osteoporosis rabbits.After the cement degradation, new bone grew into the cement and enhanced the strength of the vertebral body.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Preparation and characterization of BGs and BGs@AS

First, we synthesized bioactive glass sphere (BG) and subsequently loaded it with alendronate sodium (AS). TEM results showed that the synthesized bioactive glass sphere had particle sizes ranging from 50 to 100 nm (Fig. S1A). The average BET surface area was 606.27 m2/g, offering an ideal foundation for a high drug loading capacity (Fig. S1B). Due to the abundant silanol groups on the surface of BGs, alendronate sodium can be grafted onto both the surface and pores of the bioactive glass through N, N-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) activation. FT-IR results indicated that the peaks at 2986 and 1434 cm−1 in the BGs-CDI spectrum correspond to the stretching vibrations of C–H and C–N bonds, respectively, confirming that CDI was successfully introduced onto the surface of BGs. After the reaction between alendronate sodium (AS) and CDI-activated bioactive glass, the appearance of a peak at 2926 cm−1 was attributed to the –CH2– stretch vibration and the stretching vibration of the C–P bond. Additionally, the peaks at 580 and 1088 cm−1 corresponded to the vibration of the –PO4 group and the stretching vibration of the P–O bond in the alendronate sodium molecule (Fig. S1C). These findings confirm the occurrence of the condensation reaction between CDI and alendronate sodium [25]. In addition to FT-IR analysis, the weight loss of BGs and drug-loaded BGs was examined using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). About 8.13 % increase in mass loss after alendronate sodium grafting compared to the original BGs (Fig. S1D). The increased weight loss was primarily due to the decomposition of alendronate sodium, indicating efficient loading of alendronate sodium onto the bioactive glass. To further verify the drug loading capacity of BGs, the residual drug concentration in the supernatant after drug loading was measured via HPLC. The HPLC results demonstrated a drug loading efficiency of 11.36 % ± 2.26 % (Table S1). Which confirmed that the loading efficiency closely aligned with the TG results. The drug-loaded bioglass showed no significant morphological changes (Fig. S1A).

2.2. Injectability, cohesion, hydration process of pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA

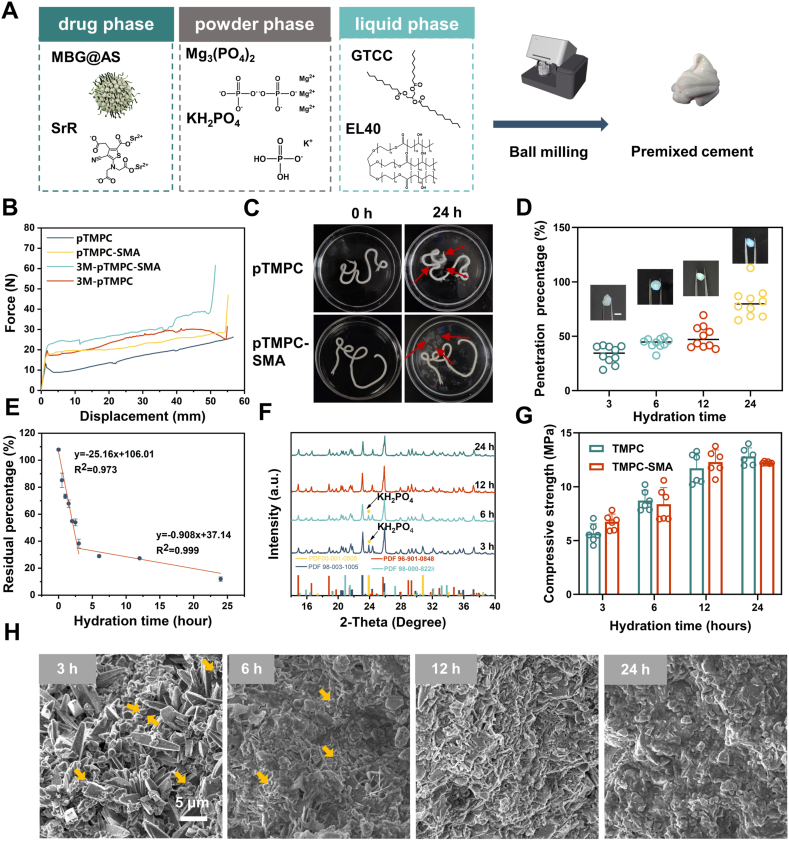

The bone cement was prepared by ball milling as Fig. 2A and the content of each phase was listed in Table S3. The injectability, cohesion, and curing behavior of bone cement are crucial to its performance, and we first evaluated these metrics. Rheological tests revealed that the static viscosity of pTMPC is approximately 600 mPa s, which increased to about 1100 mPa s after the addition of bio-glass (Fig. S2). Both pastes exhibited excellent shear-thinning behavior, indicating their injectability. While the incorporation of bio-glass significantly affected static viscosity, the viscosities of the two pastes converged with increasing shear rates. Further, the cement paste was transferred to 2.5 mL syringe for injectability test, and the storage stability was tested after 3 months of storage. The results showed that the injection force of pTMPC group was less than 10N, and the injection force increased with drug-loaded but less than 20N (Fig. 2B). Due to the fact that the added drugs and bioactive glass microspheres are finer powders, it may increase the viscosity of bone cement, thereby enhancing the injection force. The injection force of samples in each group increased after 3 months of storage, which may be due to the hydration of the material during sample encapsulation. Trace amounts of water in the environment during the processing and storage of bone cement may induce a slow hydration reaction, leading to degradation of its mechanical properties [15]. The injection rate of pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA was 98.60 ± 0.57 and 98.83 ± 0.12, respectively. After storage, the injection rate of pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA 96.83 ± 0.68 and 96.36 ± 0.79, respectively (Table S4). The bone cement in this study used a fine trimagneisum phosphate powder (D50 = 3 μm) consistent with previous studies in order to ensure promising reactivity, and this highly reactive powder may result in a shortened shelf life [7,26]. In this study, bone cement stored for three months while remaining injectable. XRD analysis of samples stored for 3 months revealed that the primary components were trimagnesium phosphate (Mg3(PO4)2) and monopotassium phosphate (KH2PO4, KDP). No detectable hydration products were observed, indicating that no hydration reaction occurred during the storage period (Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Preparation and physicochemical properties of premixed drug-loaded bone cement in the early hydration stage. (A) Diagram of bone cement preparation: the powder and liquid were mixed by ball milling and a white paste was obtained. (B) Inject force and displacement curve of premixed bone cement with different storage time. (C) Digital images of bone cement hydrated in SBF (red arrows: oil dispersant in SBF). (D) Quantitative statistics of penetration depth Visualization of the hydration process by penetration of methylene blue solution. (E) Residual oil in the bone cement hydrated at different hours (n = 3). (F) XRD of bone cement hydrated in the early stage. (G) Compressive strength of bone cement in the early hydration stage (n = 6). (H) Cross-section morphology of the bone cement in the early hydration stage (yellow arrows: unreacted powder).

The setting time and anti-washout behavior of bone cement after injection were evaluated in simulated body fluid (SBF). No collapse was observed in the injected sample, and the material solidified after setting at 37 °C for 24 h, although the crumbling of the material was observed in the liquid, the overall material did not disaggregate (Fig. 2C). The injected samples maintained structural integrity without fracture or disintegration when subjected to vibration testing (Movie S2). After hydration (24 h), surface accumulation of oily dispersant droplets in SBF was evident, confirming outward diffusion of the internal oil phase toward the aqueous environment during matrix curing (Fig. 2C). The hydration process of premixed bone cement is achieved through the exchange of oil phase dispersant and water. To visualize this process, using pTMPC-SMA as a representative material, we incorporated methylene blue into simulated body fluid (SBF) to monitor the setting progression of the bone cement (Fig. 2D). Visually, the formation of a hydrated "shell" of the material can be clearly observed after 3 h of immersion, while the inside is still uncured bone cement slurry. With the increase in setting time, the hydration depth of the material increased significantly. We quantitatively assessed the proportion of hydrated shells, which increased to 80 % after 24 h of setting. It is worth noting that the internal area is obviously hardened after 24 h, indicating that methylene blue does not penetrate the material interior further following the water. To further study the hydration process of the bone cement, we quantified residual oil content within the cement matrix using HPLC. The results demonstrated a rapid decline in internal oil content during the first 3 h of hydration, reaching 38.2 % at the 3 h. Between 3 and 24 h, residual oil decreased gradually to 11.9 % after 24 h of hydration (Fig. 2E and S4). This confirms that complete oil-water exchange occurs between the internal oil phase and the aqueous curing solution. Compared to TMPC bone cement, although the curing time of the pTMPC series bone cement is significantly extended, the bone cement can be preliminarily hardened within 3 h and fully hardened after 24 h [26].

To further investigate the hydration process, we first examined the phase of the cement during the initial 24 h. Quantitative XRD analysis revealed that unreacted KH2PO4 persisted after 6 h of hydration (Fig. 2F and Fig. S5A). By 12 h, complete consumption of KH2PO4 was detected with concomitant formation of Mg3(PO4)2·3H2O as the dominant phase. After 24 h, the amount of MgKPO4·6H2O increased significantly while Mg3(PO4)2 content progressively decreased. During the early hydration stage, mechanical properties demonstrated a progressive increase. After 3 h of hydration, the compressive strength of both pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA exceeded 5 MPa. As hydration continued, the compressive strength increased, reaching about 12 MPa at the after 24 h (Fig. 2G). The hydration temperature was recorded by digtal thermometer. No significant heat release was observed throughout the hydration process, and this cold-curing characteristic ensures the stability of the incorporated drug (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Physicochemical properties and drug release profiles of bone cement. (A) Temperature curve during cement curing. (B) XRD diffraction patterns at 3 and 7 days of hydration. (C) Mechanical properties of cement at 3 and 7 days of hydration (n = 6). (D) Load force vs. time curves from cyclic compression testing. (E) Loading forece vs. displacement curve from cyclic compression testing. (F) Microstructure of pTMPC-SMA cement after 7-day hydration. (G) Radiopacity comparison between aluminum sheets and cement. (H) Drug release profile of bone cement (n = 3). (I) Weight loss rate during cement degradation (n = 3).

2.3. Hydration products, mechanical properties, X-ray opacity, degradation, and drug release properties

After analyzing the early hydration process of bone cement, we conducted physical and mechanical property analyses on samples hydrated for 3 and 7 days. The XRD results indicated that the hydration process of TMPC bone cement using GTCC as a dispersant after 72 h of reaction was not significantly inhibited (Fig. 2G). The hydration products of traditional TMPC bone cement are MgKPO4·6H2O and MgHPO4·3H2O. The content of each phase was analyzed by Rietveld method. After 7 days of hydration, the content of the hydration product K-struvite was 15.9 % and 20.0 % in the pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA groups, respectively (Fig. 3B and Fig. S5B). And the content of MgHPO4·3H2O was 46.2 and 39.5 %, respectively. The compressive strength of pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA after 3 days of hydration was 18.8 and 19.9 MPa. After 7 days, the compressive significantly increased to 33.4 and 34.5 MPa (Fig. 3C). Compared to TMPC, the premixed cement exhibited a significant decrease in compressive strength, but its strength remained higher than other developed premixed cements [7,27].

Given the complex stress states experienced by bone tissue, which is frequently subjected to forces of varying frequencies, the fatigue resistance of materials is crucial. We conducted cyclic compression testing on pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA hydrated for 7 days. After 10 repeated compression cycles at 600N (approximately 21 MPa), the maximum stress of the samples remained stable (Fig. 3D). The stress-displacement curves indicate that after the first compression cycle, the samples did not return to the zero-strain state, suggesting the occurrence of plastic deformation. The pTMPC-SMA exhibited greater displacement than that of the drug-loaded group (Fig. 3E). Although the standard ISO5833 specifies that the compressive strength of acrylate bone cements should be greater than 70 MPa, the mismatched strength with the vertebral body, which may lead to increased stress on adjacent vertebrae, thereby increasing the risk of fractures in adjacent vertebrae [5]. The compressive strength of human vertebral trabecular bone is about 5 MPa, and the strength of pTMPC and pTMPC- SMA is 20–30 MPa, which is lower than that of PMMA bone cement but meets with the compressive strength of the trabecula to support the vertebral body [28,29]. The distribution status of the bone cement injected into the vertebral body also affects the postoperative vertebral body strength due to the different degrees of osteoporosis status in patients with different degrees of osteoporosis. The injected vertebral body is filled by bone cement to form an integrated structure, for which a single compressive strength criterion may not be sufficient to assess the appropriateness of the mechanical properties of the bone cement [30]. The study recommends that the minimum compressive strength should be greater than 10Mpa [31]. The strength of pTMPC-SMA was >10 MPa after 12 h of hydration, which met the minimum mechanical property requirements for early implantation. However, for patients with severe fractures, the vertebral body almost loses its strength and therefore the forces are concentrated on the filled cement, in which case a higher strength cement may be required for treatment. Cross-section morphology of pTMPC-SMA showed that a continuous structure had formed inside after 7 days of hydration, and drug-loaded microspheres and hydration products could be observed(Fig. 3F).

In addition to mechanical properties and curing time, the radiopacity of bone cement is also very important, especially when used in minimally invasive surgery. We compared pTMPC-SMA with clinically used PMMA and aluminum plates with different thicknesses. The radiopacity of pTMPC-SMA satisfied the ISO standard, although it was lower than that of PMMA (Fig. 3G). The HPLC analysis of strontium ranelate content in bone cement following SBF immersion demonstrated a high drug retention rate of 94.08 % post-curing (Table S2). Drug release experiments showed that the dual drug was released gradually as the material degraded. Both drugs release rapidly in the first 7 days. Due to the direct incorporation of strontium ranelate, which has a higher cumulative release, it reached 12.56 % after 14 days. Due to the covalent grafting of alendronate, its release speed was significantly reduced. After 21 days, only 9.04 % of the drug had been released (Fig. 3H). The release of SrR agreed well with the Peppas model (Table S5 and Fig. S7), indicating that the indicated a process controlled by diffusion [32]. While the release of AS agreed well with first order model (Table S5 and Fig. S7), indicated that the drug release process is jointly controlled by diffusion and the degradation of chemical bonds [33]. After 56 days of release, the drug release rate approached equilibrium but did not reach the theoretical value, which may be related to slow material degradation preventing the internal drug from being released. We further analyzed the porosity of the material using mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) (Fig. S8). The porosities of pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA were 8.23 % and 5.21 %, respectively. In addition to pores larger than 50 μm, the two materials contained pores with diameters of approximately 500 nm and 10 nm, respectively. After drug loading, the porosity decreased, and the content of pores in the ranges of 500–1000 nm decreased. These small pores can facilitate drug diffusion [14]. After 28 days, the degradation of pTMPC was about 10 %. The addition of drugs did not significantly affect the degradation rate of the material. And the degradation rate reached about 20 % after 56 days (Fig. 3I). The degradation rate of pTMPC and pTMPC- SMA shows no significant difference. The degradation rate of pTMPC was higher than that of CPC bone cement [34]. The strontium ranelate and sodium alendronate loaded within the material can be released over the long term to regulate the osteoporotic microenvironment. Upon the comprehensive evaluation, the pTMPC series bone cement demonstrates significant superiority over existing research cements in physical and chemical properties [7,35,36].

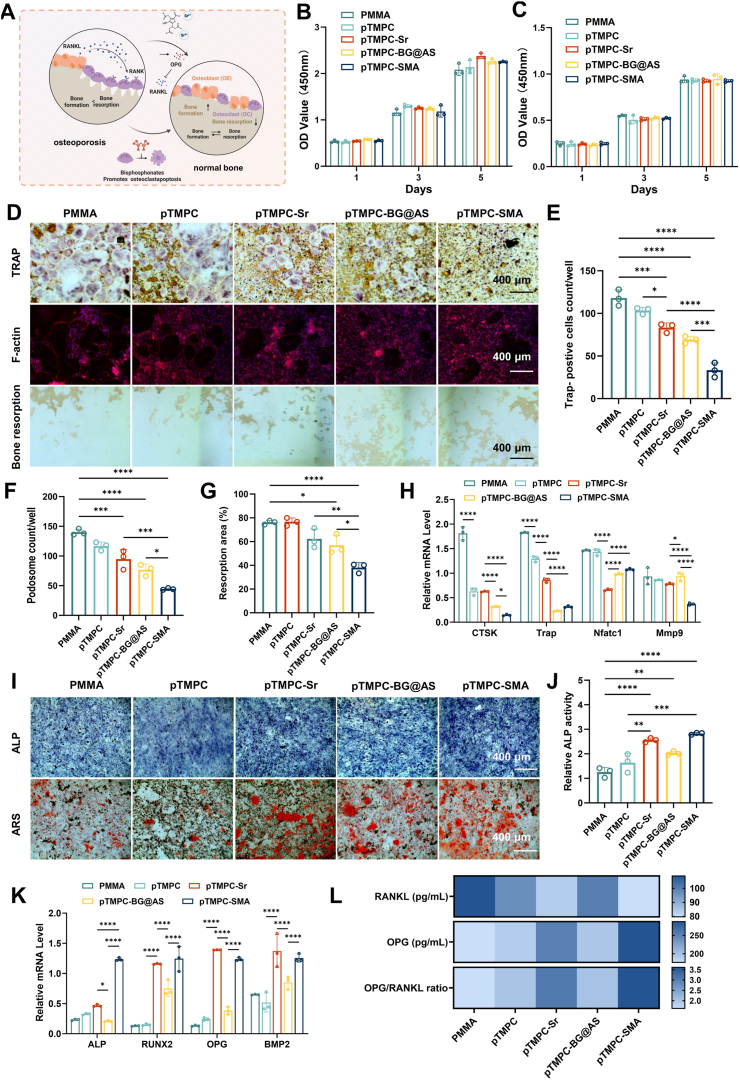

2.4. Regulation of osteoclast activity and bone resorption

In the pathological environment of osteoporosis, the activity of osteoblasts decreased and the activity of osteoclasts increased, leading to the decrease in bone mass. The success of treating osteoporotic fractures or defects critically depends on enhancing osteogenic capacity. In osteoporosis, the activity of bone resorption often exceeds bone formation (Fig. 4A). Directly inhibiting the activity of osteoclasts is crucial for rapid bone formation. To investigate the effect of bone cements on osteoclast formation, we evaluated the osteoclast differentiation through tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining, phalloidin staining, and osteoclast-related gene expression analysis. The cell viability results showed no significant difference in cell viability among the PMMA, pTMPC, pTMPC-Sr, pTMPC-BG@AS and pTMPC-SMA groups (Fig. 4B and C). The TRAP staining results showed a significant decrease in the number of TRAP-positive cells in the pTMPC-BG@AS and pTMPC-SMA group (Fig. 4D and E). No statistically significant difference was observed in TRAP-positive cells between pTMPC-Sr and pTMPC groups. F-actin is an important indicator for evaluating osteoclast cytoskeleton. PMMA controls exhibited characteristic osteoclast features, including multinucleated cells and distinct F-actin rings. Quantitative analysis revealed significantly reduced F-actin ring area and podosome density in osteoclasts cultured on pTMPC-BG@AS and pTMPC-SMA substrates (p < 0.05, Fig. 4D and F). Consistent with TRAP staining results, no statistically significant differences were observed between pTMPC-Sr and pTMPC groups. Therefore, we speculated that strontium ranelate does not directly inhibit osteoclast differentiation. The bone slices was further used to study the bone resportion of osteoclasts. Similarly, the microscopy images revealed a significant reduction in the bone resorption area in the pTMPC-BG@AS and pTMPC-SMA group (Fig. 4D and G). Expression of the osteoclastspecific marker genes, such as Cathepsin K (CTSK), TRAP, Nuclear factor ofactivated T-cells cytoplasmic 1 (NFATC1), and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), exhibited a significant downregulation in the pTMPC-BG@AS and pTMPC-SMA group compared to the PMMA group. Especially, compared to the TMPC group, the expression levels of CTSK and MMP9 genes were further downregulated in the pTMPC-SMA group (Fig. 4H). Based on integrated drug release profiles and cellular responses, we postulate that osteoclast downregulation primarily correlates with alendronate sodium (AS). While strontium ranelate-containing groups demonstrated significant suppression of osteoclastic activity (p < 0.05), this effect was less significant than that of AS. The concomitant administration group exhibited marked inhibition of osteoclast activity (p < 0.0001), suggesting potential synergistic interactions between these therapeutic agents. This aligned with prior reports documenting strontium ranelate's dual osteoanabolic and anti-osteoclastic properties [37]. Consequently, the pTMPC-SMA group incorporating both agents achieved superior therapeutic outcomes through complementary pharmacological mechanisms. These results suggested that pTMPC-SMA can effectively inhibit the activity of osteoclast.

Fig. 4.

In vitro osteoclast inhibition and osteogenic differentiation effects of bone cement. (A) Schematic diagram of dual drug release regulating osteogenic and osteoclastic balance. (B) Cell proliferation of MSCs cultured with bone cement (n = 3). (C) Cell proliferation of BMMs cultured with bone cement (n = 3). (D) Images of TRAP, Fiactin staining and bone resorption pits. (E) Quantification of TRAP-positive cells (n = 3). (F) Quantification podosome count of osteoclast (n = 3). (G) Quantification of bone resorption area (n = 3). (H) Fluorescence quantitative PCR of CTSK, TRAP, NFATC, and MMP9 after 3 days of culture. (I) ALP stainning and Alizarin red S (ARS) staining. (J) Quantitative results of ALP activity. (K) Fluorescence quantitative PCR of ALP, RUNX2, OPG, and BMP2 after 7 days of culture, respectively (n = 3). (L) ELISA of RANKL and OPG and the ratio of OPG to RANKL (n = 3).

2.5. Regulation of osteogenesis behaviour

Due to the excellent inhibitory effect of AS on osteoclasts, a significant inhibition of bone resorption was observed in in vitro osteoclast experiments. However, inhibition of osterolacst only decrease the bone resorption, which is difficult to achieve therapeutic effects in osteoporosis [38]. Therefore, combining osteogenesis was vital important to achieve bidirectional regulation between osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis enhancing the therapeutic effect [21]. The biocompatibility and osteogenic activity of bone cement were evaluated by mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). After 1, 3, and 5 days, there was no significant difference in cell viability among all groups, and all groups maintained a high cell survival rate (Fig. 4C and S9). After 7 days, ALP staining results showed that the pTMPC-SMA group had higher ALP expression, and the activity of ALP in pTMPC-Sr and pTMPC-SMA groups were significantly increased (p < 0.01). There was no significant difference between pTMPC and PMMA group (Fig. 4I and J). After 14 days, the mineralization status of BMSCs was evaluated by alizarin red staining (Fig. 4I). Obvious calcium deposition was observed in pTMPC-Sr and pTMPC-SMA group were observed. The drug-loaded pTMPC bone cement had more calcium nodules, indicating the promoting effect of strontium ranelate on bone formation [39].

In addition to the increased expression of ALP protein, the gene expression after 3 days of culture was analyzed by RT-PCR. Among the analyzed ALP, RUNX2, OPG, and BMP2 genes, the expression of OPG was significantly promoted in pTMPC-Sr and pTMPC-SMA groups (Fig. 4K). The RANKL/OPG signaling system plays an important role in regulating the balance of osteoblast and osteoclast, preventing abnormal increase or decrease of bone mass, thus maintaining normal bone tissue metabolism. The combination of RANKL secreted by osteoblast and RANK of osteoclast precursor promotes osteoclast differentiation. In order to further study the bidirectional regulatory effect of drug-loaded bone cement on osteogenic microenvironment. MSCs were stimulated and the levels of osteoprotectin and RANKL secreted by MSCs were detected by ELISA. After 7 days of culture, the expression of RANKL in pTMPC-Sr and pTMPC-SMA groups was significantly down-regulated, the expression of OPG was significantly up-regulated, and the ratio of OPG to RANKL in the material group was significantly increased (Fig. 4L). The results showed that strontium ranelate could decrease the expression of RANKL in osteoblasts and increase the expression of osteoprotegerin (OPG), which proved that strontium ranelate regulated the communication between osteoblasts and osteoclasts. In the RANKL-OPG-RANK pathway, RANK is the only osteoclast receptor of RANKL. Through cell-dependent contact recognition and binding with RANKL on the surface of osteoclast and osteoclast progenitor cells, RANK directly promotes osteoclast differentiation, activation, and maturation, and prevents osteoclast apoptosis [40]. It also regulates the transcription and expression of related genes. Thus, we believe that beyond the direct osteogenesis function, the up-regulation of the ratio of RANKL to OPG is very important to the regulation of the osteogenesis and osteoclast balance by inhibiting the osteoclast activity.

In this study, strontium ranelate and alendronate sodium were used to achieve the treatment of osteoporosis from the direction of promoting osteoblasts and inhibiting osteoclasts, respectively. From the perspective of osteoclasts, through the effect of bisphosphonates, pTMPC-SMA bone cement can directly and effectively inhibit osteoclast differentiation [17]. Drug release experiments have confirmed that, the release of AS is a long-term and low-dose regimen, which may also mitigate the complications arising from the binding of bisphosphonates to bones [18]. Meanwhile, the release of strontium ranelate directly promotes osteogenesis and also has the potential to promote osteoclast apoptosis through the RANKL-OPG-RANK signaling pathway in addition to osteogenesis [41]. This direct and indirect effect improved the osteoporosis microenvironment and restored bone homeostasis.

2.6. Transcriptome sequencing to analyze the mechanisms of osteoclast inhibition

To further investigate the inhibitory mechanism of bone cement on osteoclasts, we conducted RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on the bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs). The results showed that BMM-related cells had 710 differentially expressed genes upregulated and 810 genes downregulated [|log2(fold change)| > 1, P < 0.05] (Fig. 5A). Several differentially expressed genes were identified, as visualized in Fig. 5E. Comparative analysis against control groups reveals significant downregulation of pro-inflammatory pathway genes, including chemokines (cxcl1, cxcl2, cxcl3, cxcl5), interleukin il-1b, and nos2 (a key mediator in M1 macrophage polarization). This collective suppression of inflammatory mediators demonstrated the anti-inflammatory properties of pTMPC-SMA. Building upon these downregulated differential genes, the gene set enrichment analysis (GESA) results confirmed the significant downregulation of osteoclast differnention and TNF-α pathways in the pTMPC-SMA group (Fig. 5B). Further, the KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) enrichment analysis indicated that the inhibition of osteoclasts is associated with immune-related signaling pathways, specifically the TNF-signaling and IL-17 signaling pathways (Fig. 5C and S10). The activation of TNF-α enhances osteoclast activity, and the downregulation of these pathways is of great importance for the inhibition of osteoclasts [42,43]. Previous studies have reported that bioglass and bisphosphonates inhibit the secretion of inflammatory factors thereby improving the state of osteoarthritis [40,44]. The reduction of these genes illustrated the role of pTMPC-SMA in the regulation of osteoporotic diseases. Furthermore, a downregulation of mineral absorption pathways was observed, which may be associated with the suppression of osteoclast activity [45]. The results of gene sequencing suggested that pTMPC-SMA may down-regulate osteoclast activity and inhibit bone resorption behavior through a inflammation pathway. For upregulated genes in osteoclasts, such as Hdac9 (histone deacetylase 9), their increased expression inhibits osteoclast differentiation through the RANK/RANKL signaling pathway [46]. KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that the differentially expressed mRNAs were enriched in immune system (Fig. S11A and S11B). The top 25 KEGG enrichment revealed that these upregulated genes are associated with the p53 signaling pathway and apoptosis pathways, which related to the apoptosis of osteoclast (Fig. S11C). In the following study, osteoclast differentiation-related genes and proteins were investigated in detail. Significant downregulation of TNF-α, TNFR1 and IL-1 expression was observed in qPCR analysis versus the PMMA groups, validating the RNA-seq data pattern. (Fig. 5D). To further validate protein expression in TNF-associated signaling pathways, Western blot analysis revealed that tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1), the primary receptor for TNF-α exhibited downregulation in both single and dual-drug groups, with significantly enhanced suppression in the dual-drug system (Fig. 5F and G). Concurrently, reduced expression of downstream p-p38 was observed, indicating modulation of the RANK/RANKL/OPG signaling pathways. Notably, the pTMPC-SMA group demonstrated marked downregulation of JNK, P65, and their phosphorylated forms suggesting inhibition of NF-κB and MAPK pathways (Fig. 5H). This aligned with established mechanisms where magnesium, silicon ions, and bisphosphonates cooperatively regulate inflammatory signaling [21]. Given the inherent complexity of bioactive bone cement systems, synergistic interactions likely occur between therapeutic agents and ionic components. The enhanced therapeutic efficacy observed in our dual-drug-loaded cement supports this postulate of pharmacological synergy.

Fig. 5.

Gene expression patterns and functional enrichment analysis of osteoclast cultured with bone cement. (A) Differential gene expression volcano plot. (B) Bubble plot of KEGG enrichment of the down regulated genes. (C) Gene set enrichment analysis of BMMs. (D) Heatmap showing relative changes in expression levels of selected inflammation-related genes. (E) Fluorescence quantitative PCR of TNF signaling pathways related genes. (F) Western blot assay and (G) quantitive of protein related to TNF signaling pathways related genes (n = 3). (H) Schematic illustration of the regulating effect of on osteoclastogenesis through TNF and RANK signaling pathway.

2.7. Vascularization property of bone cement

Vascularization functionality is critical during bone regeneration. Leveraging magnesium ions' known pro-angiogenic properties, magnesium-containing bone cements consistently promote neovascularization. Using Endothelial Progenitor Cells (EPCs) as the cellular model, we evaluated the effects of pTMPC cement on vascular formation and cell migration. The results of the angiogenesis experiment showed that pTMPC bone cement can significantly promote angiogenesis, with significant increases in total tube length, node number, and branching vessel length (Figure S12A, S12 C-E). Among them, bone cement containing strontium renate had more significant tube-forming ability than pTMPC and pTMPC-BG@AS, with significant increases in total tube length and node number (p < 0.05), which may be related to the biological effects of strontium ions [47]. The results of the cell scratch assay showed that the migration rate of materials containing pTMPC after 12 and 24 h of culture was significantly higher than that of the PMMA group (p < 0.0001) (Fig. S12B and S12F).

2.8. Osteoporotic rabbit PVP surgery and finite element analysis

The rabbit osteoporosis model was established and PVP surgery was performed by a minimally invasive surgery model that has been confirmed in previous studies as a low-cost alternative to large animal models (Fig. 6A) [48]. First, a rabbit osteoporosis model was established through ovariectomy surgery. Postoperative animals in each group returned to normal diet and no infection was found. 6 months after ovariectomized, the rabbit's vertebrae were separated and subjected to bone mineral density (BMD) analysis and mircro-CT scans to determined the bone density. The bone volume percent (BV/TV) and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) values of the vertebral bodies significantly decreased after castration, confirming the successful modeling of osteoporosis (Fig. 6B–F). BMD results showed a signicant decrease of bone densiy, which decreased by 25.53 % after 6 months (Fig. 6G). To perform PVP surgery, anesthetized rabbits were guided by a C-arm X-ray machine. A 14G bone marrow cannula was used to inject PMMA and pTMPC bone cement into the L4- L5 vertebra of rabbits. Intraoperative and postoperative observations showed no leakage of bone cement and good dispersion of bone cement in the vertebra, as shown in Fig. 6H. With PMMA bone cement as the control group, the spinal models of rabbits were punctured and filled under the guidance of X-ray. pTMPC and pTMPC performed well in injectable performance, and all groups were successfully filled. The rabbit PVP surgery has confirmed that pTMPCcan be used in minimally invasive orthopedic surgery. To evaluate the biomechanical status within vertebral bodies post-bone cement treatment, finite element analysis (FEA) was employed to assess the equivalent (Von Mises) stress magnitude and distribution across material groups (Fig. 6I). The peak Von Mises stresses were quantified as 80.08 MPa (Blank), 116.16 MPa (PMMA), and 101.20 MPa (pTMPC-SMA), respectively. Cement augmentation significantly increased stress levels compared to the blank control. Critically, pTMPC-SMA demonstrated a 12.9 % reduction in peak stress versus PMMA, indicating optimized load transfer within the vertebral body. This attenuation mitigates localized stress concentration and reduces fracture risk in adjacent segments [49].

Fig. 6.

PVP surgery on the osteoporotic rabbit. (A) Operative time line. (B) Cross-section Micro-CT imges of rabbit vetebra after surgery for 24 weeks. Quntitive micro-CT analysis of vertebra (n = 3) (C) bone volume/total volume (BV/TV), (D) trabecular number (Tb.N) levels, (E) trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), (F) trabecular thickness (Tb.Th). (G) Bone mineral density (BMD) of lumbar spine preoperatively, 12 and 24 weeks post-surgery (n = 6). (F) Intraoperative and postoperative conditions shown on C-arm fluoroscopy. (I) Von Mises stress cloud diagram of different material groups 3 months after surgery.

2.9. μ-CT and histological analysis of osteoporotic rabbit after PVP surgery

The rabbits were euthanized at 6 and 12 weeks, and their vertebrae were separated. The vertebrae were subjected to CT scanning and reconstruction. Based on the different CT values, PMMA bone cement and dense cortical bone appeared blue and white, while pTMPC bone cement and trabecular bone appeared green (Fig. 7A). 6 weeks after implantation, new bone formation was observed around the pTMPC-SMA cement, indicated by areas with higher CT values. In contrast, PMMA group showed no significant new bone formation, and areas with low CT values were observed between the PMMA and bone, likely representing a fibrotic interface. According to the CT analysis, for the blank group, group there was almost no new bone formation, the BV/TV values was about 0.3 % and 0.4 % after 6 and 12 weeks, respectively (Fig. S14). For the materials groups after six weeks showed that the BV/TV values for PMMA, pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA were 3.16 %, 13.59 %, and 15.44 %, respectively, with significantly higher bone formation around the implanted bone cement compared to the PMMA group (p < 0.0001). In addition to BV/TV, the number of trabeculae (Tb.N) and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) also showed significant improvement (p < 0.0001, Fig. 7B–E). Twelve weeks post-implantation, CT reconstruction results indicated substantial material degradation and new trabecular bone formation, with the newly formed trabeculae closely integrated with the material (white arrows). The BV/TV values for pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA were 7.15 %, 17.75 %, and 22.39 %, respectively (Fig. 7B). Notably, CT reconstruction results demonstrated that the pTMPC-SMA group exhibited more trabecular bone formation (white arrows), also a significant lower trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) value compared to PMMA group (p < 0.001), suggesting the feasibility of drug therapy in promoting local bone homeostasis reconstruction.

Fig. 7.

PVP surgery on the osteoporotic rabbit. (A) Micro-CT imges of rabbit vetebra after surgery. Quantitative analysis of (B) bone volume/total volume (BV/TV), (C) trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), (D) trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), and (E) trabecular number (Tb.N) levels after 6 weeks and 12 weeks of implantation (n = 4). (F). Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. (G). Masson's trichrome (MT) staining. (NB for newly formed bones, M for materials and FT for fiber tissues, scale bar: 1 mm).

Further histological analysis of the newly formed tissue was conducted. In the PMMA group, no significant osteogenesis was observed at 6 and 12 weeks post-implantation, with fibrous encapsulation forming around the material (Fig. 7F). In the pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA groups, thin layers of new bone were observed regenerating around the material at 6 weeks (red arrows), with the drug treatment group showing a higher amount of new bone compared to the non-drug treatment group. By 12 weeks, substantial new bone growth around the material was observed, with the pTMPC-SMA group exhibiting significantly more bone formation than the other groups. Further, immunohistochemical staining was used to analyze OPN, ALP, and TRAP expression around the material. Immunohistochemical staining revealed an increase number in the OPG and ALPexpression levels in the pTMPC-SMA group compared to the other groups (Fig. 8). TRAP-positive osteoclasts typically localize at the periphery of newly formed bone tissue and existing bone margins. Multinucleated TRAP-positive cells were observed adjacent to both pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA materials, suggesting potential involvement in material degradation processes. Conversely, the limited osteogenic volume in PMMA controls precluded observation of TRAP-active osteoclasts (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Representative images of immunohistochemical staining of OPN, ALP, TRAP of the histopathological bone tissue treated by bone cement. (Red arrows: positive expression, scale bar: 200 μm).

The results of the rabbit PVP experiment demonstrated excellent in vivo osteogenesis performance. According to CT results, due to the densification and non-biodegradability of PMMA bone cement, the defect area was filled with a small amount of fibrous tissue, and few new bone formation was observed in the PMMA group (Fig. 8). Both pTMPC and drug-loaded pTMPC bone cement formed good osseointegration with bone tissue. After 12 weeks of implantation, it was observed that the drug-loaded group had better osteogenesis, and the bone tissue grew into the inside of the material to form an integrated composite structure. Modified PMMA improved the integration between the material and the bone, but this type of material makes it difficult for new bone to grow in due to its non-degradability [5]. Compared to calcium phosphate-based materials, long-term in vivo studies have shown a lack of degradability of either brushite or CDHA-type CPC cements [50]. The integration and degradation of bone in pTMPC-based cements have significant advantages over the above material materials.

2.10. Biosafety evaluation in vivo

Finally, we evaluated the biosafety of pTMPC bone cement via a short-term subcutaneous implantation model. Specimens were harvested at 3, 7 and 14 days for H&E staining, complete blood counts and organ-toxicity assays to monitor acute inflammation and systemic safety. No notable immune-cell infiltration was detected around any implant at any time point; instead, newly formed micro-vessels were observed around pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA after 7 days (Fig. S15), consistent with the vascularization propertyof magnesium phosphate [33]. In vitro tube-formation assays corroborated the vascularization activity of pTMPC-based materials. Histological examination of the heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney revealed no pathological alterations (Fig. S16), and routine blood parameters remained within normal ranges (Table S10). Collectively, these findings confirm the excellent in vivo cytocompatibility of the pTMPC bone cement.

3. Conclusion

Based on the challenges in treating osteoporosis-related diseases and deficiencies in existing clinical therapeutic products, this study developed a premixed magnesium phosphate bone cement loaded with therapeutic drugs (pTMPC-SMA). The premixed cement paste demonstrated extended ambient-temperature storage stability and handling characteristics. Hydration occurred immediately upon aqueous contact, achieving initial set within 3 h and final set whithin 24 h. The released strontium ranelate and alendronate sodium could regulate the activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. In vitro experiments demonstrated that these drugs can promote bone formation, inhibit bone resorption, bidirectional modulate osteoporotic microenvironment, and restore bone homeostasis. The results of vertebroplasty experiments in osteoporotic rabbits showed that compared to PMMA, the drug-loaded pTMPC bone cement significantly enhanced new bone formation. This premixed bone cement demonstrated significant potential for repairing osteoporotic bone defects and vertebral compression fractures, efficiently promoting osteogenesis. Nevertheless, comprehensive assessment in large animal models at weight-bearing sites remained essential prior to clinical deployment to validate the material's efficacy and biosafety profile.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Materials

MgHPO4⋅3H2O, Mg(OH)2, strontium ranelate (SrR), alendronate sodium (AS), polyvinylpyrrolidone K-60, 9-fluorenylmethyl chloroformate (FMOC), hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB), sodium hydroxide and tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) were purchased from Macklin, China. Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, triethyl phosphate, N, N′-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) were obtained from Sinopharm, China. Triglyceride caprylate capric acid (Miglyol 812), castor oil polyoxyethylene ether (EL40), and potassium cetyl phosphate were purchased from Huaxiangkejie Biotechnology, China. All reagents are analytical grade and used directly unless otherwise specified. α-MEM, fetal bovine serum, and penicillin-streptomycin solution were all purchased from Cytiva, USA. Antibodies and gene sequences used in the study can be accessed in the Supplementary Tables S7 and S8.

4.2. Synthesis and characterization of BG and TMPC bone cement raw powders

Bioglass spheres were prepared by sol-gel method combined with hydrothermal reaction with modified [51]. Briefly, 0.46 g NaOH and 1.0 g polyvinylpyrrolidone K-60 were dissolved in 120 mL deionized water, adding 1.4g CTAB at room temperature and stirred for 60 min. Then 5.22 g TEOS, 1.1 g Ca (NO3)2·4H2O and 0.73 g triethyl phosphate according to Si/Ca/P = 80:15:5 (molar ratio)were added and stirred for 24 h. The sol was transferred to the reactor and the hydrothermal reaction was carried out at 80 °C for 48 h. After the reaction, the products were washed with anhydrous ethanol and deionized water respectively, and dried overnight at 100 °C. Finally, the dried product was sintered at 550 °C for 5 h.

BG@AS Prepare according to the previously published article, Specifically, BG (100 mg) were dispersed in ethanol of CDI (50 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. Then the CDI-BG (50 mg) were dispersed by sonication in AS-saturated solution (20 mL, 10 mg/mL), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. BG@AS were obtained after washed with ethanol three times and dried in a vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h.

Trimagenisum phosphate was prepared according to the previous study [26]. 144 g MgHPO4⋅3H2O and 24 g Mg(OH)2 were mixed by a planetary ball mill (BM6Pro, POWTEQ) for 2 h at 250 rpm. Then it was sintered at 1150 °C for 5 h. The obtained sintered cake was crushed by ball milling for 18 h at 300 rpm. KH2PO4 was crushed by ball milling for 6 h at 300 rpm.

Particle size, spherical morphology, and mesostructure of the prepared BG were observed with TEM (JEM-1400Plus, Japan) at 120 kV. The porosity and pore size distribution were characterized by micropore automatic physisorption analyzer ASAP 2460 (Micromeritics, America) under N2 atmosphere. The vibration modes characteristics were obtained on an FTIR spectroscopy (Nexus, America) in the range of 500–4000 cm−1 and a thermal gravimetric analyzer (TGA8000, PE, America) under oxygen atmosphere from room temperature up to 1000 °C at a rate of 10 °C·min−1 was used to analysis the mass loss.

4.3. Preparation of pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA

The element content of trimagnesium phosphate was shown as Table S6. Oil phase dispersion medium contained 83.4 wt% triglyceride caprylate capric acid (GTCC), 15.0 wt% castor oil polyoxyethylene ether (EL40) and 1.6 % wt. % potassium cetyl phosphate as surfactant. The basic formula of TMPC bone cement was used as previously reported and the M/P ratio was 3 [26]. Briefly, 12 g trimagnesium phosphate as the magnesium source, 4 g potassium dihydrogen phosphate as the acid phosphate source, and 0.16 g ZrO2 as the contrast agent were blended with 2.82 g dispersion medium (with solid content 85 %) by ball milling at 300 rpm for 30 min. The mixed stock is quickly transferred to the syringe at low humidity (<40 %) for storage. To prepare drug-loaded pTMPC bone cement pTMPC-SMA, 5 wt% BGs@AS, 5 wt% strontium ranelate (SrR) was added to the paste and blended by ball milling. The mass content of component was shown as Table S1.

4.4. Injection force and injectability

The paste was transferred into 2.5 mL syringe and the injection force was tested using an electronic universal testing machine (CM 4005, MTS) at a load speed of 20 mm/min according to the previously reported method [52]. The inject force and displacement were recorded for the sample stability test. The premixed bone cement was stored in stored 2.5 mL syringe with vacuum sealed under 25 °C and 30–40 % humidity for three months. For injectability test, the mass of bone cement loaded into the syringe before injection and the mass remaining in the syringe after injection was recorded to calculate the injection rate.

4.5. Cohesive, setting time and hydration process

For the cohesive test, 2.0 g paste was transferred into a 5 mL syringe and injected into SBF. After 24 h of immersion the sample was removed and risined with water and weighed. To visualize the hydration process, the setting time was tested with reference to previous reports in the literature [53]. The paste was immersed in methylene blue solution (1 mg/mL), which allowed to assess the process of water oil exchange. The paste was extruded through a 1 mL syringe. The samples were withdrawn from the solution at each time point and digital images were taken. Dye penetration was quantified using Image J software. The setting time was tested using a Vicat apparatus. The setting time is recorded until the needle of the Vicat apparatus is unable to penetrate more than 1 mm into the sample [54]. The residual amount of dispersant in the bone cement curing process was studied using HPLC.Specifically, sample extraction: Add 0.4 g of sample to 10 mL of SBF and incubated at 37 °C for 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0,2.5, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h.The SBF was removed at each time point and rinsed three times with deionized water and dried at 37 °C. Then, the solidified samples was grinded and exctrated with 2 mL of acetone:chloroform (1:1) for three times. The extraction solution was adjusted to 10 mL and filted by 0.45 μm filter. The extracted solvent was analyzed using HPLC. The HPLC system used a refractive index detector (2414, Waters, USA), with a mobile phase of acetonitrile: acetone 1:1, flow rate of 1 mL/min, and an Agilent Zobax C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 3 μm).

4.6. Compressive strength, phase composite, and morphology

The method of the compressive strength was according to ISO 5833-2002 [55], the slurry was injected into a cylinder silicone mold with 6 mm diameter and 12 mm height and subsequently immersed in simulated body fluid (SBF). Samples were tested after 3, 6, 12, 24, 72 and 144 h. Prior to testing, the upper and lower surfaces were polished with sandpaper to ensure parallelism. The samples were loaded at 5 mm/min through an electronic universal testing machine. After testing, the samples were immersed in ethanol overnight to stop the hydration reaction and subsequently ground for X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The ground samples were examined using Cu Ka radiation (40 kV, 40 mA) in continuous scanning mode. Quantitative analysis of the obtained XRD data was performed using the Rietveld method with Highscore Plus software (Netherlands). For scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis (IT-200, JEOL, Japan), the cross-section of the material was gold-sprayed. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) spectra were acquired using a large-area XMax silicon drift EDS detector (Oxford Instruments, UK) and analyzed with Aztec software (Oxford Instruments, UK). Mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) was used to characterize the porosity and pore distribution using a mercury porosimeter (AutoPore IV 9500, Micromeritics, USA) with samples hydrated for 7 days. During the analysis, the pressure increased up to 420 kPa followed by a faster pressure decrease until 0 kPa. The internal software of the porosimeter determines the results with a contact angle of 130°.

4.7. Degradation of bone cement

The cement disks were vacuum-dried overnight, and their initial mass (mi) was recorded. The disks were then immersed in 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) at a concentration of 0.2 g/mL [21]. The buffer solution was refreshed every 3 days, and the pH value was measured at each interval using a multi-parameter analyzer. After washing and vacuum drying, the final mass of the disks (md) was recorded. The weight loss ratio was calculated using the following formula: .

4.8. Drug loading and release test by high performance liquid chromatography

The release of strontium ranelate was determined by HPLC using a mobile phase of 0.2 % phosphoric acid solution-methanol 85:15, and the pH was adjusted to 5.0 by triethylamine. The test was performed at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and a detection wavelength of 237 nm. For drug loading ratio determination, approximately 0.31–0.42 g of samples hydrated for 24 h were rinsed with deionized water and ground into powder (Table S2). The powder was then extracted twice with 4 mL of mobile phase each time. The extracts were combined and diluted to a final volume of 10 mL. After filtration through a 0.22 μm membrane filter, the samples were subjected to HPLC analysis. For drug release testing, samples were immersed in PBS solution at a concentration of 0.2 g/mL. At predetermined time points (1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 days), 1 mL of the release medium was collected and replaced with an equal volume of fresh PBS. The collected aliquots were filtered through 0.22 μm membranes prior to HPLC analysis.

Alendronate was passed through the precolumn derivatization method before testing. Briefly, different concentrations of AS solution (1 mL, 10–100 μg mL−1), boric acid buffer (1 mL, 0.1 mol L−1, pH = 9), and FMOC in acetonitrile (0.8 mL, 0.1 %) were vortex mixed for 30 s and allowed to react for 25 min at room temperature. Subsequently, dichloromethane (5 mL) was added and mixed for 60 s. The mixed solution was centrifuged at 10000 r min−1 for 5 min. The mobile phase was 25 mM disodium hydrogen phosphate buffered solution (pH = 8.0) – acetonitrin – methanol = 75:20:5, tested at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, and the detection wavelength was 266 nm. Data were collected and calculated by Empower 3 chromatography software.

For the drug loading ratio test, the supernatant from drug-loaded AS was diluted 1000-fold and subjected to the aforementioned derivatization reaction to determine residual drug concentration. Drug loading ratio was calculated as the ratio of loaded drug amount to the BGs feed amount. Regarding drug release testing, release medium collected at designated time points was processed through the derivatization reaction followed by HPLC analysis, following the methodology described above. For drug release test, samples were immersed in PBS solution at a concentration of 0.2 g/mL. At predetermined time points (1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 days), 1 mL of the release medium was collected and replaced with an equal volume of fresh PBS. The collected aliquots were filtered through 0.22 μm membranes prior to HPLC analysis. The HPLC drug standard curve and release profiles are provided in Fig. S6.

4.9. Cell culture

Primary bone marrow mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs)of C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Cyagen Biosciences(Santa Clara, CA, USA). Cells were cultured in a complete medium consisting of 90 % α-MEM, 10 % fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin sulfate at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. All cement samples for cell experiment were sterilized prior to use for the implantation experiments γ-irradiation with a dose of 25 kGy. Specifically, PMMA, pTMPC, pTMPC-Sr, pTMPC-BG@AS and pTMPC-SMA samples with diameter 8 mm and height 2 mm were cultured with cells in 24 well plate.

4.10. In vitro osteogenesis test

To test the effect of different scaffold materials on osteogenic differentiation of MSCs cells, the cells were inoculated at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in 24-well culture plates, cultured with scaffold extract for 24 h and then replaced with osteogenic induction medium (DMEM supplemented with 50 μg mL−1 ascorbic acid, 10 mmol L−1 β-glycerophosphate disodium, and 10 nmol L−1 dexamethasone) [5]. The medium was changed every 3 days and cultured at 37 °C, 5 % CO2 incubator. MSCs incubated with the osteogenesis differentiation medium were used as the Control group. After culture for 14 days, the ALP staining and ARS staining were respectively performed using a BCIP/NBT ALP Color Development Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) and an ARS solution (Cyagen Bioscience, China). Then they were visualized by a stereo microscope (Olympus, Japan). Meanwhile, the ALP activity was analyzed with an ALP activity assay kit (Beyotime Institute ofBiotechnology, China).

4.11. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity, F-actin staining and bone resorption of bone marrow-derived macrophages

The bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) were isolated from the femurs of 4-week-old C57/BL6 female mice following a previously established protocol [56]. In brief, BMMs were cultured in α-MEM medium supplemented with 10 % FBS, 1 % penicillin-streptomycin, and 50 ng/mL macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 incubator. The medium was replaced every 3 days. Once the cells reached 80–90 % confluence, they were digested with 0.25 % trypsin for subsequent experiments.

For the TRAP staining assay, BMMs were cultured in α-MEM complete medium containing bone cement extract solution, 30 ng/mL M-CSF, and 75 ng/mL receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL). After 5 days of culture, the cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde and stained using a TRAP staining kit (#387A, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). TRAP-positive multinucleated cells (with three or more nuclei) were identified as osteoclasts and counted. For F-actin ring fluorescence staining, the cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min, stained with phalloidin-rhodamine and DAPI, and then rinsed three times with PBS. For bone resorption assay, bone slices were placed in 96-well plates, BMMs were seeded on the bone slices (250 thousand per well). After culturing for 14 days, bone slices were observed by optical microscopy. The average bone resorption area were analyzed by image J software. Images were captured using an inverted fluorescence microscope, and the number of TRAP-positive cells and F-actin area were quantified using ImageJ software.

4.12. Osteogenesis and osteoclast-related gene and protein expression tests

Cells were cultured for 3 days and qRT-PCR was performed to detect mRNA expression of the osteoclast-associated marker CTSK, TRAP, NFATC1 and Mmp9, and gene expression levels were normalized to the level of the housekeeping gene β-Actin. The osteoclst-associated genes, ALP, RUNX2, BMP2, OPG and RANKL were test and normalized to the level of the housekeeping gene GAPDH. The total RNA was isolated by TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA), and the RNA was reverse transcripted into cDNA with a cDNA Synthesis kit (Servicebio, China). Then the qRT-PCR analysis was performed using SYBR (Servicebio, China), and the mRNA expression was assessed and expressed as the 2−ΔΔCT method. The specific primers are listed in Table S7.

For Western Blot (WB) analysis, BMMs after culturing for 3days were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer and supplemented with proteinase and phosphatase inhibitors (Beyongd, China). The total protein extracts were then mixed with loading buffer, subjected to boiling for electrophoresis, and subsequently transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Following this, the membranes were blocked with a 5 % solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA, Macklin, China), incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, and thoroughly washed three times using a Tris-buffered saline solution (Servicebio, China) containing 0.1 % Tween 20. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The anti-body list was shown in Table S8. After incubation, the membranes were treated with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) substrate. The proteins were then detected and analyzed using the ChemiDoc XRS system (Bio-Rad, USA).

4.13. Transcriptomic study of the osteoclast activity

BMM cells were cultivated with PMMA and pTMPC-SMA cement extraction (n = 3). After 7 days of incubation, total RNA was extracted and assayed for purity. RNA integrity was evaluated with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, USA). Raw data were filtered using the fastp software and subjected to quality control using FastQC software. If the quality control results met the criteria subsequent analyses were performed. For experiments with biological replicates (where differentially expressed genes are defined as FoldChange|> 2 and padj< 0.05), differential expression analysis was conducted using DESeq2 software. GO functional significance enrichment and KEGG pathway significance enrichment analyses were conducted based on DEGs.

4.14. Vascularization evaluation In vitro

For the tube foramation assay, the mouse vascular endothelial cells (Ecs,BNCC, China) were seeded into the 96 well plate (2 × 104/well) and cultured with conditioned medium (0.2 g/mL) supplemented with 10 % FBS and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin. After 3 h, the cells was observed by microscopy. The total tube length, the number of nodes, and total branching length were quantified using the ImageJ software. For cell migration assay, Ecs (4∗104/well) were seeded into the 24 well plate, when the cells reached 80–90 % confluence, an artificial scratch wound was obtained by a 200 μL pipette tip. At the incubation of 12 h, and 24 h, the cells were observed by an inverted microscope. The wound closure percentages were analyzed by the ImageJ software.

4.15. Osteoporotic rabbit model and pvp surgery

The use and care of experimental animals was approved by Guangdong Medical Lab Animal Center (C202208-18). The procedures for animal experiments and animal welfare are as shown in the table (Table S9). All cement samples for animal experiment were sterilized prior to use for the implantation experiments γ-irradiation with a dose of 25 kGy. The rabbit vertebroplasty experiment following a previously established protocol [48]. Thirty-six 5-month-old female New Zealand rabbits, weighing 3.02 ± 0.25 kg, were purchased and acclimatized for two weeks. After anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital administered through the ear vein, placed in the prone position, and routinely disinfected, their bilateral ovaries were removed by the dorsal approach. After 12 weeks of scientific breeding, the OVX-induced osteoporotic model was established successfully via micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) analysis [57]. Thirty-rabbits, induced with osteoporosis, were randomly divided into four equal groups: the sham group (n = 6), PMMA group (n = 8), the pTMPC (n = 8) and the pTMPC-SMA (n = 8) bone cement group. After anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital, a needle incision was made near the vertebral body's needlepoint, and the L5 spinous process was located by palpation. A 14G bone marrow cannula (Myelo-Gal; Iskra Industry Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was then inserted 1–2 mm into the bone at the designated site. The position of the transverse process and vertebral body was confirmed using X-ray imaging (Toshiba X-ray machine; TOSHIBA, Tokyo, Japan). Once the cannula was correctly positioned, it was filled with the injection material, which was allowed to solidify before retracting the needle. For the sham grpup, the needle was retracted without injecton. To avoid postoperative infections, penicillin sodium was administered intramuscularly (25,000 U/kg) for 3 consecutive postoperative days. All rabbits survived the surgery with minimal bleeding and no significant wounds or injuries.

4.16. Micro-CT imaging and histological staining of the treated vertebral body

The rabbits were euthanized at 6, and 12 weeks after PVP (n = 6), and the attachments of the vertebrae were removed. All vertebrae amples were scanned by μ-CT to visualize the formation of hard tissue with a scanning parameter of 100 kV, 98 μA, and 9 μm voxel size. Each sample was reconstructed using a CTan software (Bruker, Germany) under the same conditions. Cylinders of 1.5 mm in diameter and 1.5 mm in height were taken from the vertebral bone and femur to determine the trabecular thickness. The reconstruction parameters of the cancellous bone analysis in all samples were as follows: gray scale of cancellous bone >1000 and bone surface/bone volume (BS/BV) ratio = 1/mm. The collected vertebra samples were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for at least 48 h and subsequently decalcified and embedded in paraffin, followed by tissue slicing and staining by hematoxylin-eosin staining, and Masson staining. For immunohistochemical staining, the tissue slices were prepared via paraffin embedding of decalcified tissue and stained with ALP, OPN and TRAP to observe the effects on bone repair, the antibodies were listed in Fig. S8. Additionally, Hearts, livers, spleens, lungs, and kidneys were validated for biosafety through H&E.

4.17. Assessing biological safety through subcutaneous implantation

Subcutaneous implantation and histological analysis were performed to evaluate the biocompatibility of bone cemnt in vivo.27 SD rats were randomly divided into three groups (PMMA, pTMPC and pTMPC-SMA) bone cement were sterilized and surgically 200 μL bone cement paste was injected into subcutaneous on the backs of the rats. After 3, 7 and 14 days, the rats were euthanized, and the implants with skin tissues were immediately fixed in 4 % buffered paraformaldehyde overnight, embedded in paraffin, sectioned and processed for hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining to observe inflammatory cells and blood vessels containing erythrocytes.

4.18. Finite element analysis of biomechanical effects of bone cement after vertebroplasty

Three months post-vertebroplasty, lumbar vertebral models from the blank control group, PMMA group, and pTMPC-SMA group in rabbits were acquired via micro-CT scanning. All CT images were preserved in DICOM format with a slice thickness of 18 μm. The image datasets were imported into the medical 3D reconstruction software MIMICS 21.0, where unrefined bone tissue models were segmented to construct three-dimensional structures. Reconstructed vertebral body models derived from the scanned images were subsequently exported in STL format. These STL models underwent smoothing and assembly procedures using Geomagic 2021 and SolidWorks 2021. Finally, the processed model files were imported into ANSYS 17.0 for mechanical simulation. Boundary conditions (Fig. S13) were defined as 50N axial compressive load and 0.27N·m torque, with the inferior vertebral endplate designated as a fixed constraint [58].

4.19. Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, all experiments were independently performed at least three times. Images represent experimental findings, and the data are expressed as means ± SD. One-way ANOVA was performed to determine the significant differences between various groups with the Control group by grapad prism 10 software. Ns represented no significant difference, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.001.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jiawei Liu: Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Jinjin Zhu: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation, Conceptualization. Takashi Goto: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Shuhui Yang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Honglei Kang: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. Xiumei Wang: Supervision, Funding acquisition. Honglian Dai: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No clinical trials were conducted in this study. The use and care of experimental animals was approved by Guangdong Medical Lab Animal Center (C202208-18).

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

J.L. and J.Z. contributed equally to this work. The authors are grateful for financial support grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52372272, 32201109, 82302712, and 32360234), the Key Research and Development Program of Hubei Province (2024BCB005, 2023BCB138), the Key Research & Development Program of Zhejiang Province (2024C03075), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022B1515120052 and 2021A1515110557, 2022A1515111192), the Key Basic Research Program of Shenzhen (JCYJ20200109150218836), the Self-innovation Research Funding Project of Hanjiang Laboratory (HJL202202A002).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of editorial board of Bioactive Materials.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2025.08.022.

Contributor Information

Honglei Kang, Email: kangmed@hust.edu.cn.

Xiumei Wang, Email: wxm@mail.tsinghua.edu.cn.

Honglian Dai, Email: daihonglian@whut.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Reid I.R., Billington E.O. Drug therapy for osteoporosis in older adults. Lancet. 2022;399(10329):1080–1092. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin S., Yang G., Jiang F., Zhou M., Yin S., Tang Y., Tang T., Zhang Z., Zhang W., Jiang X. A magnesium-enriched 3D culture system that mimics the bone development microenvironment for vascularized bone regeneration. Adv. Sci. 2019;6(12) doi: 10.1002/advs.201900209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J.L., Xu J.K., Hopkins C., Chow D.H., Qin L. Biodegradable magnesium-based implants in orthopedics-A general review and perspectives. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 2020;7(8) doi: 10.1002/advs.201902443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostrowski N., Roy A., Kumta P.N. Magnesium phosphate cement systems for hard tissue applications: a review. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016;2(7):1067–1083. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H., Cui Y., Zhuo X., Kim J., Li H., Li S., Yang H., Su K., Liu C., Tian P., Li X., Li L., Wang D., Zhao L., Wang J., Cui X., Li B., Pan H. Biological fixation of bioactive bone cement in vertebroplasty: the first clinical investigation of borosilicate glass (BSG) reinforced PMMA bone cement. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022;14(46):51711–51727. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c15250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verlaan J.J., Lopez-Heredia M.A., Alblas J., Oner F.C., Jansen J.A., Dhert W.J.A. 7.12 injectable bone cements for spinal column augmentation: materials for kyphoplasty/vertebroplasty. Comprehens. Biomater. II. 2017:199–215. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroter L., Kaiser F., Preissler A.L., Wohlfahrt P., Kuppers O., Gbureck U., Ignatius A. Ready-to-use and rapidly biodegradable magnesium phosphate bone cement: in vivo evaluation in sheep. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2023;12(26) doi: 10.1002/adhm.202300914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Funk D.A., Nguyen Q.-V., Swank M. Polymethyl methacrylate cure time in simulated in vivo total knee arthroplasty versus in vitro conditions. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021;16(1):629. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02790-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J., Liu W., Schnitzler V., Tancret F., Bouler J.-M. Calcium phosphate cements for bone substitution: chemistry, handling and mechanical properties. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(3):1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iesaka K., Jaffe W.L., Kummer F.J. Effects of the initial temperature of acrylic bone cement liquid monomer on the properties of the stem-cement interface and cement polymerization. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2004;68(2):186–190. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irbe Z., Loca D. Soluble phosphate salts as setting aids for premixed calcium phosphate bone cement pastes. Ceram. Int. 2021;47(17):24012–24019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buss N., Ryan P., Baughman T., Roy D., Patterson C., Gordon C., Dixit R. Nonclinical safety and pharmacokinetics of Miglyol 812: a medium chain triglyceride in exenatide once weekly suspension. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2018;38(10):1293–1301. doi: 10.1002/jat.3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinemann S., Rossler S., Lemm M., Ruhnow M., Nies B. Properties of injectable ready-to-use calcium phosphate cement based on water-immiscible liquid. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(4):6199–6207. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]