Abstract

Tiger nut oil (TNO) is a promising oil due to its excellent oxidative stability. The simulated system was developed using stripped tiger nut oil (STNO) and hydratable phospholipids (HP) extracted from TNO to study HP's antioxidant role. Results showed that HP (0.5–8.0 g/kg) increased STNO's oxidative stability index (OSI: 1.50 h) to 1.69–13.68 h, outperforming sterols (0.5–4.0 g/kg, 2.21–2.28 h) but less effective than tocopherols (0.1–0.5 g/kg, 19.27–25.14 h). However, when tocopherols and HP coexisted in STNO, their association may have enhanced the hydrogen-donating ability of tocopherols for scavenging lipid free radicals, thereby synergistically increasing the OSI of STNO to 53.11 h. Phosphatidylethanolamine and lysophosphatidylcholine were the most oxidation-prone components of HP, showing over 90 % loss. Furthermore, HP enhanced the thermal stability of STNO and the oxidative stability of commonly edible oils. Therefore, HP imparts superior oxidative stability to TNO as a key component.

Keywords: Tiger nut oil, Hydratable phospholipids, Oxidative stability, Synergistic effect

Highlights

-

•

Endogenous hydratable phospholipids (HP) act as antioxidants in tiger nut oil.

-

•

Tiger nut HP exerted a highly effective synergistic effect with tocopherols.

-

•

HP significantly enhanced the thermal stability of tiger nut oil.

-

•

HP also significantly enhanced the oxidative stability of 11 common edible oils.

1. Introduction

Tiger nut (Cyperus esculentus L.), a promising oilseed, widely cultivated in many regions, such as Western Europe, North Africa, East Asia, and the Americas (Edo et al., 2024; Nwosu, Edo, & Özgör, 2022). In China, it is regarded as an important oil resource for the future (Zhang et al., 2023). Tiger nut oil contains a high amount of unsaturated fatty acids (>84 %) in its triglycerides, yet it exhibits excellent oxidative stability (Yoon, 2016). Oxidative stability is an important concern for consumers, as oxidation products can greatly affect the sensory properties, shelf life, and health implications of oils (Monto et al.,2023; Bayram & Decker, 2023). Tiger nut oil (TNO) exhibits a higher oxidative stability index (OSI: 52.3–125.0 h) (Yoon, 2016; Zhang et al., 2023, 2024). Under the same test conditions, this value was found to be higher than that of some other oils with high oleic acid content, such as olive oil (27.9 h) (Zhang, Jia, Chen, & Zhu, 2025) and peanut oil (8.4 h) (Zhang et al., 2025), as well as many other common oils, including soybean oil (5.8 h) (Li et al., 2019), sunflower oil (7.9–10.0 h) (Arabsorkhi, Pourabdollah, & Mashadi, 2023), sesame oil (9.4 h) (Zhang et al., 2025), and safflower seed oil (2.2 h) (Hou et al., 2024).

Previous studies speculated that oleic acid and tocopherols are the two main factors to contribute the remarkable oxidative stability of TNO (Edo et al., 2024; Nwosu et al., 2022). The oils with high oleic acid content usually have very high oxidative stability because its oxidation rate is 27 times that of linoleic acid, which has been widely reported (Bayram & Decker, 2023; Liu, Zheng, & Liu, 2025). The same applies to TNO, which also has a high oleic acid content (65 %–74 %) (Guo, Wan, Huang, & Wei, 2021). From the perspective of concomitants, TNO contains relatively abundant tocopherols, with levels ranging from 142 to 348 mg/kg, predominantly α-tocopherol (110–329 mg/kg) (Liu et al., 2025; Nwosu et al., 2022). However, although tocopherols are the primary antioxidant components in most plant oils, TNO is not particularly outstanding when compared to other oils such as olive oil (45–414 mg/kg), sunflower seed oil (708–780 mg/kg), and rapeseed oil (91–973 mg/kg) (Edo et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2023). Hence, there may be other concomitants influencing the antioxidant properties of TNO. For example, phytosterols are the most prominent components in TNO (1714–6856 mg/kg), and it can be speculated that they contribute to its oxidative stability (Nwosu et al., 2022). Moreover, recent research has shown that removing hydratable phospholipids from TNO using high-temperature water (85 °C), medium-temperature water (55 °C), or 0.2 % NaCl solution (55 °C), all for 30 min, reduces total phospholipids by 69.95 %, 63.77 %, and 65.60 %, respectively, with no significant changes in other antioxidants, but decreases OSI from 52.3 h to 19.3 h, 18.9 h, and 19.8 h (Zhang et al., 2024). Another study also demonstrates that removing hydratable phospholipids from TNO by centrifuge at room temperature reduces the OSI from 105.2 h to 67.4 h, without causing significant loss of tocopherols (Zhang et al., 2025). Non-hydratable phospholipids, accounting for 26 %–30 % of the total phospholipid content, did not appear to contribute significantly to the antioxidant capacity of TNO (Zhang et al., 2024). However, phospholipids alone typically exhibit very weak antioxidant activity in oils, or even pro-oxidant effects (Bayram & Decker, 2023; Hou et al., 2024). Some studies have also reported that phospholipids can exhibits a synergistic antioxidant effect when present with tocopherols (Kim et al., 2023; Su et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024). Therefore, whether the hydratable phospholipids in TNO interact with tocopherols or sterols, and the influence of this interaction on the oxidative stability of TNO, remain undetermined.

To investigate how endogenous hydratable phospholipids (HP) affect the oxidative stability of tiger nut oil (TNO), stripped tiger nut oil (STNO) and HP were firstly isolated and prepared for the simulation system. The changes in oxidative stability index (OSI) and thermal stability of STNO supplemented with HP were then evaluated. In comparison with tocopherols or sterols, the impact of HP on the oxidative stability of STNO during storage was analyzed. Finally, HP was combined with either tocopherols or sterols and added to STNO, after which changes in oxidative stability were monitored. This study will advance the development of novel functional phospholipids and facilitate the production of premium-quality tiger nut oil.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and chemical reagents

The tiger nuts were collected from local farmland in Hebei province, China. Isopropanol, dichloromethane, and acetonitrile were of chromatographic grade, while hexane, acetone, methanol, citric acid, phosphate, ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), sodium hydroxide, triphenyl phosphate were analytical grade and purchased from Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Deuterated chloroform (CDCl3, 99.8 %), α-tocopherol (98 %), β-tocopherol (96 %), and γ-tocopherol (98 %) was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Campesterol (98 %), β-sitosterol (98 %), and stigmasterol (98 %) were purchased from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,Ltd. (Beijing, China).

2.2. Preparation and characterization of stripped tiger nut oil (STNO) and hydratable phospholipids (HP)

2.2.1. Preparation of STNO and HP

According to the procedure of Guo et al. (2021) and Boon et al. (2008), tiger nut was crushed (<0.6 mm) and mixed with n-hexane at a liquid-to-solid ratio of 1:3 (g/mL), and stirred at 50 °C for 3 h. The n-hexane layer containing the oil was separated and then subjected to vacuum evaporation using a rotary evaporator (RV 10, IKA-Werke GmbH & Co. KG, Staufen, Germany) at 50 °C and a final pressure of 9 mbar to obtain tiger nut oil (labeled as TNO). 100 g of TNO was heated to 60 °C, sprayed with 1.5 mL distilled water, stirred at 400 rpm for 20 min, and centrifuged at 5180 ×g for 30 min. The upper layer was degummed oil, and the lower layer was crude hydratable phospholipids. Crude hydratable phospholipids were freeze-dried using a freeze dryer (LGJ-25C, Foring Technology Development Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for 48 h at a pressure of 70 Pa and a cold trap temperature of −60 °C. Then it was repeatedly washed with saturated cold acetone (4 °C) to remove residual trace amounts of oil and antioxidants, resulting in purified hydratable phospholipids (HP). Degumming oil (100 g) was heat to 60 °C, add 0.2 mL of citric acid solution (45 % wt.), stirred for 20 min, then add 3 mL of distilled water and stirred for another 20 min. After centrifugation, the lower layer was discarded, and the upper layer (oil), which was the sample without residual phospholipids, was collected. The obtained oil (50 g) was mixed with chromatographic-grade n-hexane at a ratio of 1:1 (g/mL) and then subjected to column chromatography. The column was packed with activated silica gel (200 g) at both the bottom and top layers, and activated carbon (60 g) was filled in the middle layer. The eluent was chromatographic-grade n-hexane, with an elution rate of 3 mL/min. The eluate (oil with solvent) was subjected to vacuum rotary evaporation (RV 10, IKA-Werke GmbH & Co. KG, Staufen, Germany) at 25 °C (final pressure: 9 mbar) to remove the solvent preliminarily, followed by vacuum freeze-drying (LGJ-25C, Foring Technology Development Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for 48 h (70 Pa, cold trap: −60 °C) to eliminate residual solvent. The resulting stripped tiger nut oil was labeled as STNO.

2.2.2. Fatty acid composition and moisture content

The fatty acid composition was determined following the AOCS method Ce 1 h-05 (2009). 500 mg oil was subjected to derivatization to obtain methyl esters. Derivative product was then analyzed using a 7890 A GC system (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) with an HP-88 column (100 m × 0.25 mm × 0.2 μm). The relative content (%) of each fatty acid was calculated using the area normalization method. The moisture content of the samples was analyzed according to ISO standard 662 (2016), published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

2.2.3. Vitamin E content

The determination of tocopherols and tocotrienols was conducted using the method outlined by ISO 9936 (2016). The oil sample (0.5 g) was dissolved in 10 mL of n-hexane, then filtered and injected into a high-performance liquid chromatography system (Waters e2695 HPLC, CA, USA) equipped with an NH2 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm × 5 μm) and fluorescence detector (2475, Waters, CA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of hexane-isopropanol (99:1, v/v), with a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min at a column temperature of 40 °C. Excitation/emission wavelengths were set at 298/325 nm.

2.2.4. Total phospholipid content

Phospholipid content was measured by Molybdenum blue colorimetric method according to AOCS Ca 12–55 (2009). 3 g of oil were combined with zinc oxide and heated until completely charred, then placed at 550 °C for 2 h. The residue was dissolved in hydrochloric acid and filtered. The filtrate was neutralized using potassium hydroxide solution and then mixed with distilled water to dilute it. The spectrophotometer was utilized to measure the absorbance at 650 nm for determining the phospholipid content.

2.2.5. Total sterols content

Total sterols content was measured according to ISO 12228 (2014). The oil (250 mg) was subjected to saponification using the ethanolic potassium hydroxide solution to obtained the unsaponifiable matter. The sterols were isolated by thin-layer chromatography and analyzed by the 7890 GC system (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) with an HP-5 column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.50 μm).

2.2.6. Total phenols, flavonoids, carotenoids content

The method for determining the total phenols content of oils followed the procedure outlined by Suri, Singh, and Kaur (2022). In brief, the oil was dissolved in n-hexane and then combined with a 10 % sodium carbonate solution and Folin-Ciocalteu reagent for 90 min. The absorbance at 710 nm was measured using a X8 spectrophotometer (Shanghai Metash Instruments Co., Ltd., China). The absorbance value was then converted to mg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per 100 g of oil. Carotenoids in the oil samples were assessed using a Carotenoid Content Assay Kit (BC4330, Solarbio, Beijing, China).

2.2.7. Metallic element content

Metallic elements of oil were detected by ICP-OES method (inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry) according to ISO 21033 (2016). The oil samples were blended with nitric acid and decomposed using the microwave digestion system, and the resulting solution was diluted with distilled water to a specified volume before being injected into the ICP-OES system (Aglient 5900, USA) for analysis.

2.2.8. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of oils

The oil samples were analyzed using Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy, and the spectra (400–4000 cm−1) was recorded by Nicolet iN10 (Thermo Nicolet Corporation, USA).

2.2.9. Physicochemical properties of oils

The ISO 3960 (2017), and ISO 660 (2020) was used to estimate the peroxide value and acid value of oil samples respectively.

2.3. Oxidative stability index and thermostability of oils adding hydratable phospholipids (HP)

2.3.1. Adding HP in the tiger nut oil and other common oils

The addition method referred to Bai et al. (2024). Briefly, the HP was dissolved in a chloroform–methanol solution (2:1, v/v) to obtain the HP stock solution. The HP solution was then added to different oils. The commercially purchased oils included cold-pressed flaxseed oil, corn germ oil, olive oil, rapeseed oil, soybean oil, peanut oil, and cold-pressed walnut oil. The self-made oils prepared in the laboratory included cold-pressed sesame oil, cold-pressed safflower seed oil, cold-pressed sunflower oil, cold-pressed pepper seed oil, cold-pressed tiger nut oil, and acid-degummed tiger nut oil, among others. The mixed oils were then subjected to vacuum rotary evaporation at 25 °C, followed by vacuum freeze-drying for 24 h to remove residual solvents. The amount of HP added to the above oil samples was 4 g/kg.

2.3.2. Oxidative stability index by Rancimat method

The oxidative stability index (OSI) of these oils was determined by a Rancimat 734 instrument (Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland) following the procedure outlined by ISO 6886 (2016). In brief, 5 g of oil was transferred into a glass reaction vessel (length: 15.0 cm, diameter: 2.4 cm) equipped with an opaque cover (height: 14.7 mm) and connected to two gas conduits. An opaque circular foam baffle (20 mm diameter) was installed inside the glass vessel at about two-thirds of the tube length from the bottom. Each vessel was then inserted into a light-tight heating well (depth: 12.5 cm, internal diameter: 2.5 cm). The oils were heated to 110 °C with an airflow rate of 20 L/h. The induction period was recorded and used as oxidative stability index.

2.3.3. Thermostability of STNO with the addition of HP

HP were added to the STNO according the section 2.4, and then 10 ± 0.5 mg of oil was weighed and used for thermogravimetric analysis. The air flow rate was 50 mL/min and the heating rate was 10 °C/min. The curve of mass change with temperature was recorded.

2.4. Storage test of STNO after adding HP, tocopherols, or sterols

2.4.1. Preparation of oil samples and accelerated storage test

The proportions of each component added to STNO were based on the composition of TNO, and the addition method described in section 2.3.1. Briefly, the HP (see Section 2.2.1), tocopherols (α-tocopherol: β-tocopherol: γ-tocopherol = 30:10:1), and sterols (β-sitosterol: campesterol: stigmasterol = 18:5:3) were dissolved in a chloroform–methanol solution (2:1, v/v) and then added into STNO, respectively. These mixtures were then subjected to vacuum rotary evaporation at 25 °C, followed by vacuum freeze-drying to remove residual solvents. Three oil samples (STNO+HP, STNO+tocopherols, and STNO+sterols) were obtained, with HP, tocopherols, and sterols added at concentrations of approximately 6 g/kg, 0.3 g/kg, and 2 g/kg, respectively. Each oil sample was divided into five portions and stored in brown glass bottles of equal volume at 110 °C. Portions of each sample were taken at 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h, respectively. STNO was used as the control.

2.4.2. Detection of composition and properties of oils

The ISO 3960 (2017), ISO 660 (2020), and ISO 6885 (2016) was used to estimate the peroxide value, acid value, and p-anisidine values (p-AV) of oil samples respectively. The fatty acid composition, tocopherols, and sterols of the oil samples were detected according section 2.2.

2.4.3. Phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P NMR)

The 31P NMR spectra of oil samples were acquired with an NMR spectrometer (Bruker 400 M, Bremen, Germany). Triphenyl phosphate (0.3 mg/mL in CDCl₃) was employed as an internal standard. 20 mg of sample was mixed with 0.5 mL of internal standard, 0.5 mL of methanol, and 0.5 mL of EDTA-Na+ (0.2 mol/L). The mixture was vortexed for 10 min, then left to stand for 30 min, and centrifuged for 10 min at 5000 rpm using a centrifuge (DM0506, DLAB Scientific Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The lower phase was then transferred to an NMR tube for analysis at a probe temperature of 25 °C with a sweep width of 9718 Hz, interval of 10 s, acquisition time of 3.2 s, and number of scans set at 512 (Ahmmed et al., 2020, p. 14288).

2.4.4. Detection of HP by ultra performance liquid chromatography - tandem mass spectrometry

Detection of samples was according to previous study (Zeb, Ali, & Al-Babili, 2024). Briefly, 400 μL methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), 80 μL methanol (MeOH) were added to 200 μL sample for a vortex of 30 s; centrifuge at 3000 r/min for 15 min to separate the organic phase and the aqueous phase; then transfer the upper layer of MTBE to a new EP tube to dry; then redissolved in 100 μL DCM-MeOH solution (1:1, v/v). The analysis of samples was carried on ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system (Waters, Milford, Massachusetts, USA) equipped with a Waters HSS T3 (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm). The mobile phase A was acetonitrile: water (6:4, v/v, containing 10 mmol/L ammonium acetate), and phase B was acetonitrile: isopropanol (1:9, v/v, containing 10 mmol/L ammonium acetate); the flow rate was 0.3 mL/min; the column temperature was 40 °C; the injection volume was 2 μL; the elution gradient was as follows: 0–4 min A: B (70: 30, v/v), 4–22 min A:B (0: 100, v/v), and 22–26 min water: acetonitrile (70: 30, v/v). For the mass spectrometry detection system, the conditions of the electrospray ionization source (ESI) were as follows: sheath gas 60 arb; auxiliary gas 10 arb; ion spray voltage 3000 V / -2800 V; temperature 350 °C; ion transfer tube temperature 320 °C. The scan mode was Full-scan MS2 mode; the scan method was positive ion/negative ion. The primary scan range: 80–1200 Da, the primary resolution was 70,000, and the secondary was 17,500.

2.5. Interaction effect of HP with tocopherols or sterols in STNO

2.5.1. Preparation and oxidative stability index of simulation system

The HP, tocopherols and sterols were added to STNO according to section 2.4.1. The target addition levels of HP were 0.5, 2.0, 4.0, 6.0, and 8.0 g/kg, and the corresponding detected concentrations were 0.48 ± 0.08 (C1), 1.92 ± 0.12 (C2), 3.86 ± 0.06 (C3), 5.85 ± 0.11 (C4), and 7.77 ± 0.23 g/kg (C5), respectively. For tocopherols, the target levels were 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 g/kg, with measured values of 0.10 ± 0.002 (C1), 0.20 ± 0.007 (C2), 0.30 ± 0.003 (C3), 0.40 ± 0.005 (C4), and 0.50 ± 0.008 g/kg (C5), respectively. Similarly, for sterols, the target levels were 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 g/kg, and the corresponding detected concentrations were 0.50 ± 0.01 (C1), 1.00 ± 0.03 (C2), 2.00 ± 0.02 (C3), 3.00 ± 0.05 (C4), and 4.00 ± 0.06 g/kg (C5), respectively. Therefore, it was found that the target was basically achieved. According to Tang et al. (2023), the interaction between the HP and tocopherols or sterols was determined by the following formula:

| (1) |

where OA, OB and OAB represent the oxidation stability index of the oil samples with antioxidant A added alone, antioxidant B added alone and both A and B added simultaneously, respectively; When CI value (combination index based on effect) was >1, = 1, and < 1, it indicates synergistic effect, additive effect, and antagonistic effect, respectively.

2.5.2. Electron spin resonance spectra of oil samples

The electron spin resonance (ESR) parameters were derived from a previous study (Yang, Qin, Zhu, & He, 2022) and set as follows: microwave power was 20 mW, modulation amplitude was 1.0 G, modulation frequency was 100 kHz, central field was 3360 G, scan width was 100 G, and scan time was 30 s. Acquisition of ESR spectra: The free radicals were trapped by DMPO (5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide). DMPO was dissolved in toluene to prepare a solution with a concentration of 0.5 mol/L. Then, 50 μL of DMPO solution was mixed with 250 μL of oil and stirred for 10 min at room temperature. 200 μL of the mixed solution was aspirated and transferred to a quartz tube with a diameter of 4 mm. The temperature was set at 110 °C. The quartz tube was inserted into the resonant cavity and balanced for 5 min. Then, ESR spectra were obtained at 10, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min, respectively.

2.5.3. Fluorescence spectra of oil samples

The fluorescence spectra were obtained according to Siejak et al. (2025). The excitation wavelength was 295 nm, the excitation and emission slits were 10 nm, and the recording range of the emission spectrum was 300–800 nm. The scanning acquisition interval was set at 5 nm and the scanning rate was 30,000 nm/min. The samples were directly injected into the quartz cell and maintained for 20 min at 298.15 K (25 °C).

2.6. Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics 23.0 software (Chicago, USA). The experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the results are reported as the mean with the standard deviation (SD). ANOVA (one-way analysis of variance) and Duncan's multiple comparison tests (p < 0.05) were performed for significant analyses. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to assess correlations among different indicators.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Composition of stripped tiger nut oil (STNO) and hydratable phospholipids (HP)

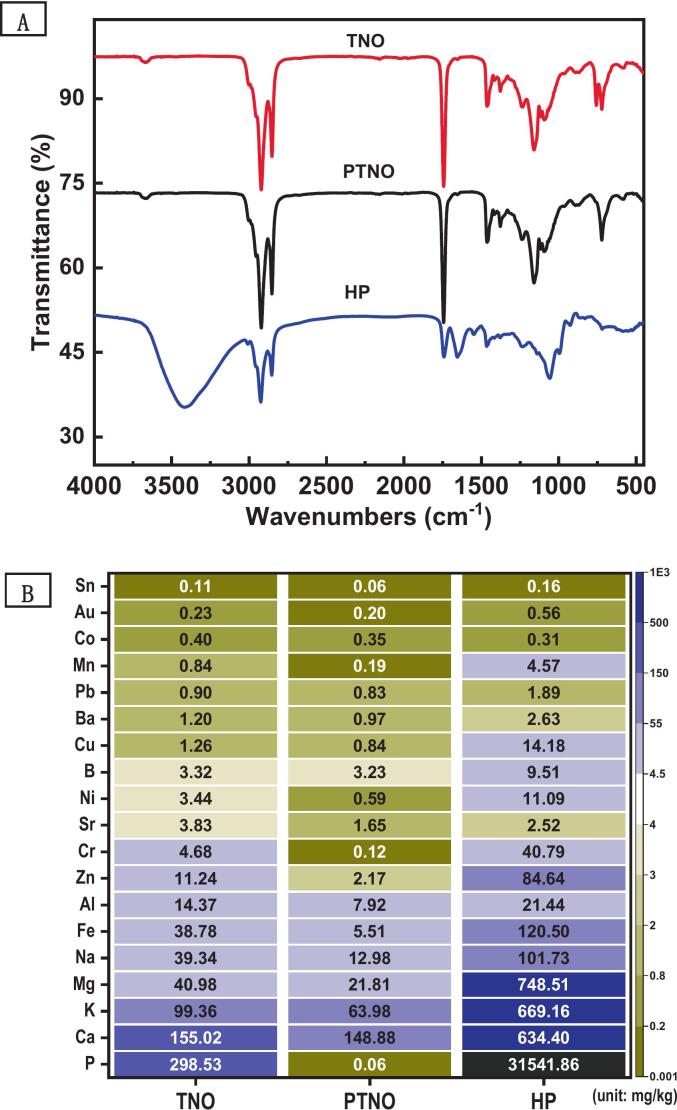

STNO and HP were used to prepare simulation system, and their compositions were analyzed first (Table 1). The major antioxidants, including phospholipids, sterols, tocopherols, phenolic acids, and flavonoids, were not detected in STNO. The acid value and peroxide value remained at low levels compared to TNO, indicating that STNO was not subjected to further oxidation during the preparation process (Liu et al., 2025; Ma et al., 2023). HP contained little amounts of oil, moisture, and protein, and antioxidants such as sterols and tocopherols were not detected. STNO was similar to TNO, and both exhibited typical infrared spectra of glycerides (Fig. 1). The most notable difference between HP and these oils was the presence of peaks at 3300 cm−1, 1240 cm−1, 1090 cm−1, 1050 cm−1, 1025 cm−1, and 981 cm−1, which corresponded to the functional groups -OH, PO₂−, C—O (from C-O-PO₂), C—O (from ester groups), C-O-P, and CN (from (CH₃)₃-N+) in phospholipid molecules (Zhang et al., 2024). Therefore, the spectra also indicated that the main component of HP was phospholipids. Metal ions generally catalyze the autoxidation of oils, and fluctuations in their concentrations can impact the oxidative stability of oils (Bayram & Decker, 2023; Yu et al., 2025). The total content of metal elements in STNO was lower than that in TNO (Fig. 1), as a portion of the metals was removed during the degumming and purification processes (Zhao et al., 2024). Hence, these results indicated that STNO was suitable for simulation system used in subsequent experiments due to the well stripping efficacy.

Table 1.

The chemical composition, acid value, and peroxide value of the samples.

| Item | TNO | STNO | HP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil (g/kg) | 999.0 ± 0.5 | 999.8 ± 0.4 | 64.3 ± 1.0 |

| Protein (g/kg) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.453 ± 0.024 |

| Moisture (g/kg) | 1.4 ± 0.3 | n.d. | 15.2 ± 1.3 |

| Phospholipid (g/kg) | 8.2 ± 0.6 | n.d. | 903.6 ± 5.7 |

| Tocopherol (mg/kg) | 257.5 ± 0.7 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Sterol (mg/kg) | 2914.9 ± 17.6 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Total phenolic (mg/kg) | 235.2 ± 2.4 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Flavonoids (mg/kg) | 61.8 ± 1.1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Carotenoids (mg/kg) | 6.9 ± 0.3 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Acid value (mg KOH/g) | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 12.86 ± 0.23 |

| Peroxide value (mmol/kg) | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.39 ± 0.04 |

| Fatty acid composition | |||

| Palmitic acid (%) | 12.79 ± 0.04 | 12.54 ± 0.02 | 16.53 ± 0.17 |

| Palmitoleic acid (%) | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.64 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.04 |

| Stearic acid (%) | 4.03 ± 0.02 | 4.82 ± 0.01 | 2.15 ± 0.06 |

| Oleic acid (%) | 74.02 ± 0.05 | 73.74 ± 0.02 | 66.08 ± 0.14 |

| Linoleic acid (%) | 8.68 ± 0.03 | 8.26 ± 0.01 | 14.31 ± 0.08 |

| Arachidic acid (%) | 0.11 ± 0.01 | n.d. | 0.67 ± 0.01 |

Note: TNO: tiger nut oil; STNO: stripped tiger nut oil; HP: hydratable phospholipids; n.d., not detected. The limit of detection for protein content was 0.001 g/kg.

Fig. 1.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (A) and metal content (B) of the samples. (TNO: tiger nut oil; STNO: stripped tiger nut oil; HP: hydratable phospholipids from tiger nut oil).

3.2. Oxidative stability of different oils with the addition of HP

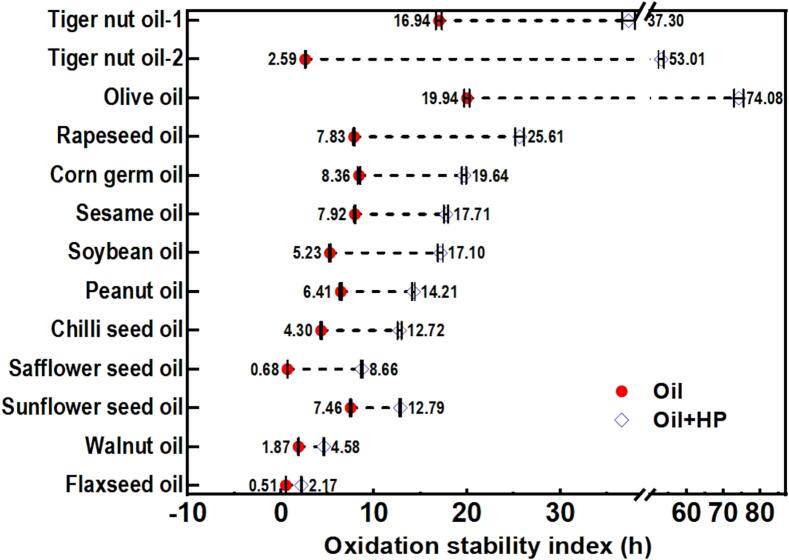

As shown in Fig. 2 and Table S1 (see Supplementary materials), the oxidative stability index (OSI) values of all oil samples after adding HP are 1.7 to 20.5 times initial values. Therefore, HP extracted from TNO not only enhanced the oxidative stability of tiger nut oil but also improved that of other common edible oils. According to Table S2 (Supplementary materials), the addition of HP, the oil type, and their interaction all had a highly significant effect on the oxidative stability index. The extent of improvement in oxidative stability varied depending on the oil type. This may be attributed to various factors, such as differences in fatty acid composition and the content of endogenous antioxidants (Ma et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024). The fatty acid composition was probably not the unique critical factor, because the difference in the fatty acid components of degummed tiger nut oil and cold-pressed oil from the same batch of raw materials was much smaller than that with other oils and can be ignored (Wang et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024). However, the change in oxidative stability varied clearly among them after the addition of HP. Hence, the primary reason for the variation among all oils may lie in the differing compositions and concentrations of antioxidant components present in each oil sample (Ma et al., 2023; Su et al., 2024). HP may interact with the endogenous antioxidants in oil to form a new antioxidant system, thereby exerting a strong synergistic effect that enhanced the oxidative stability of the oils (Su et al., 2024). This mechanism will be further examined in the subsequent sections.

Fig. 2.

Oxidative stability index of different oils before and after adding HP. (HP: hydratable phospholipids from tiger nut oil; Tiger nut oil-1: degummed tiger nut oil; Tiger nut oil-2: cold-pressed tiger nut oil; Detailed data are provided in Table S1 and Table S2, see Supplementary Materials).

3.3. Thermal stability of STNO with the addition of HP

Regarding thermal stability (Fig. 3), after adding different amounts of HP to STNO and adjusting the phospholipid content to reach 2 and 6 g/kg, respectively, the initial decomposition temperature of the oil increased significantly—from 328.29 °C to 336.75 °C and further to 368.16 °C. This indicated that the addition of HP markedly improved the thermal stability of tiger nut oil. Moreover, previous studies have shown that the thermal stability of tiger nut oil decreases after all phospholipids are removed through degumming (Guo et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024). Therefore, it reflected from both positive and negative aspects that HP can improve the thermal stability of the oil. The critical reason was that HP improved the oxidative stability of oil enabling the oil to better resist the oxidation and the thermal decomposition during the heating process (Hou et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2025). Thermal stability, which refers to the resistance of oil to high-temperature decomposition into smaller, volatile compounds, is significantly influenced by its composition; Oxidative stability pertains to the resistance to oxidation, primarily involving free radical formation and peroxide accumulation (Porter, 2025; Yu et al., 2025). These two properties are interrelated, as the products of oxidation and thermal decomposition can influence each other's reaction processes (Porter, 2025; Yu et al., 2025). HP suppressed free radical oxidation and delayed glyceride autoxidation, which may have contributed to reduced intermediate formation during thermal decomposition and a higher decomposition temperature (Shishkina, Mazaletskaya, Kozlov, & Sheludchenko, 2023). Moreover, the binding between different lipids is also important in affecting the thermal stability of oil. Phospholipid molecules can interact with the fatty acid chains of triglycerides via van der Waals forces (Wen et al., 2025). Additionally, phospholipid head groups can form hydrogen bonds with triglyceride ester groups (Chen et al., 2025; Yasuda, Al Sazzad, Jäntti, Pentikäinen, & Slotte, 2016). These interactions might enhance the thermal stability of the oil.

Fig. 3.

Thermal stability of stripped tiger nut oil (STNO) before and after adding HP (hydratable phospholipids). (A: STNO; B: STNO with an HP content of 2 g/kg; C: STNO with an HP content of 6 g/kg).

3.4. Storage stability of STNO with the addition of HP

The physicochemical properties and composition of STNO with the addition of HP during the accelerated storage process are shown in Fig. 4, where tocopherols and sterols were used as controls, and their addition levels were based on those found in original sample (TNO). The acid values of all samples remained below 0.7 mgKOH/g after storage, which is slightly higher than AOCS standard for oil (0.5 mgKOH/g). However, the peroxide values of the oils after storage (23.9–56.9 mmol/kg) were markedly above the AOCS standard (2.5 mmol/kg). This can be attributed to the fact that the fatty acids in triglycerides primarily underwent thermal oxidation in this work, whereas the hydrolysis of triglycerides was relatively limited (Yildiz, Öztekin, & Anaya, 2025). Based on all the physicochemical indicators measured after storage, tocopherol exhibited clearly superior antioxidant capacity in inhibiting the oxidative deterioration of STNO compared to sterols and HP. Specifically, the acid value of STNO with added tocopherol increased by only 2.11-fold, much lower than that of STNO supplemented with sterols (5.55-fold), phospholipids (3.14-fold), and the control group without any antioxidant (6.23-fold). Furthermore, the increases in peroxide value and p-anisidine value were also the smallest in the tocopherol-added sample, indicating that tocopherol was more effective in delaying both the initial oxidation reaction and the formation of subsequent oxidation products (Ma et al., 2023; Monto et al., 2023; Wen et al., 2025). This advantage may be attributed to the phenolic hydroxyl group in the molecular structure of tocopherol, which enables efficient free-radical scavenging and interrupts the chain reaction of lipid oxidation (Hou et al., 2024). In contrast, sterols and phospholipids mainly exerted their antioxidant effects indirectly through physical actions such as modulating interfacial tension or influencing lipid phase behavior, lacking the ability to directly capture free radicals, thus resulting in relatively weaker antioxidant activity (Liu et al., 2025; Monto et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024). In summary, tocopherols demonstrate superior antioxidant performance in STNO due to its stronger free-radical scavenging capability and more efficient oxidation inhibition mechanism.

Fig. 4.

The physicochemical properties and composition changes of STNO with HP addition during the thermal oxidation process and compared with those of STNO with sterols and tocopherols added. (A: acid value; B: peroxide value; C: p-anisidine values; D: composition of tocopherols; E: composition of sterols; F: composition of HP, Detailed data are presented in Table S1; Different lowercase letters on columns of the same class indicate significant differences according to Duncan's test, p < 0.05).

In STNO with added tocopherols during accelerated storage, the total tocopherol content began to decrease markedly starting from the 6th hour, and the loss rate reached 49.43 % by the 24th hour (Fig. 4). Among them, the loss rate of α-tocopherol was the highest (61.97 %) than that of β-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol. The loss of tocopherols was due to the oxidation reaction during the heating process, which was beneficial in delaying the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids (Kim et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2024). The lowest loss rate was observed for sterols, due to their greater stability compared to unsaturated fatty acids (Tang et al., 2023). Conversely, their antioxidant activity might have been limited, and under the experimental conditions, they were not oxidized before the oil itself underwent oxidation. Consequently, the oil sample containing sterols exhibited a relatively significant increase in both acid value and peroxide value (Li et al., 2025). In STNO with added phospholipids, all types of phospholipid molecules showed different degrees of loss (1.21 %–99.27 %), indicating that phospholipids might have undergone thermal cracking or oxidative decomposition during the accelerated storage process (Hou et al., 2024; Su et al., 2024). The loss rates of phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE) and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) reached 99.27 % and 90.22 % respectively, and the loss rate of phosphatidylcholine (PC) reached 50.05 % (Fig. 4F, Table S3). Also, it can be seen from the nuclear magnetic phosphorus spectrum (Fig. S1, see supplementary materials) that the signal intensities of all phospholipid molecules were decreasing. This was because phospholipids were easy to oxidation in the absence of strong antioxidants (Yildiz et al., 2025; Yu et al., 2025). The phospholipid molecules with the above-mentioned large losses might be the main components exerting the antioxidant effect (Zhao et al., 2024). The changes in fatty acid composition indicated that the loss of unsaturated fatty acids in STNO was the greatest (7.27 %), while in STNO with added tocopherol, phospholipids, and sterols, the losses were 1.83 %, 2.25 %, and 6.45 % respectively (Fig. S2, see supplementary materials). Therefore, whether from the perspective of physicochemical property or component changes, the antioxidant enhancement effect of adding sterols and HP alone on STNO was very weak, far less than that of tocopherol.

3.5. Interactions of HP and tocopherols, and sterols in STNO

3.5.1. Oxidative stability of HP-, tocopherols-, and sterols-added STNO

As shown in Fig. 5A, the OSI (oxidative stability index) increased progressively as the levels of tocopherols and HP in STNO (stripped tiger nut oil) rose from C1 to C5. The selected concentrations were based on the typical levels of phospholipids and tocopherols in tiger nut oil used in this study, as well as those reported in the literatures (Edo et al., 2024; Nwosu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2024), which helps enhance the practical application value of the research findings. In contrast, no notable enhancement in oxidative stability was observed in the sterols-supplemented oil samples (C1–C5), a finding that aligns with the storage stability results discussed in the preceding section. The OSI of the STNO supplemented with HP was shorter than that supplemented with tocopherols, indicating that, within the concentration ranges of tocopherols and HP simulated in tiger nut oil, the antioxidant capacity of HP was markedly lower than that of tocopherols. This finding was also consistent with the results of the storage stability analysis in section 3.4. When comparing the oxidation stability index (OSI) of the tiger nut oil (TNO) used in this study, two key issues emerged: a) The OSI values of stripped tiger nut oil (STNO) supplemented with HP (<13.68 h), tocopherols (<25.14 h), or sterols (<2.28 h) alone were markedly lower than the OSI of TNO (98.30 h), failing to approach the original level; b) Previous reports indicated that the removal of HP from TNO led to a significant reduction in OSI, up to 62.1 % (Zhang et al., 2024). In contrast, in this study, increasing HP concentrations in STNO (0.5–8.0 g/kg) resulted in only a modest increase in OSI, ranging from 1.50 h to 1.69–13.68 h. The core contradiction lies in the observation that removing HP from TNO results in a significant decrease in the OSI. However, reintroducing HP into STNO, which lacks all natural antioxidants, failed to restore the oxidative stability, and only minimal recovery was achieved. This finding suggested that HP may interact synergistically with other constituents (Yildiz et al., 2025).

Fig. 5.

The oxidation stability index of STNOs with added HP, sterols, tocopherols, HP-sterols, and HP-tocopherols. (A: STNO with added HP, sterols or tocopherols; B: STNO with added HP-sterols; C: STNO with added HP-tocopherols; Concentration of HP in STNO: 0.5 (C1), 2.0 (C2), 4.0 (C3), 6.0 (C4), and 8.0 g/kg (C5). Concentration of sterols in STNO: 0.5 (C1), 1.0 (C2), 2.0 (C3), 3.0 (C4), and 4.0 g/kg (C5); Concentration of tocopherols in STNO: 0.1 (C1), 0.2 (C2), 0.3 (C3), 0.4 (C4), and 0.5 g/kg (C5). CI: combination index based on effect; CI > 1: synergistic effect; CI < 1: antagonistic effect, CI = 1: additive effect).

3.5.2. Oxidative stability of STNO with HP–tocopherols and HP–sterols combinations

To investigate above-mentioned speculation, HP was co-supplemented with either tocopherol or sterols in STNO, and the resulting changes in the oxidative stability index (OSI) were assessed (Fig. 5 B—C). The CI (combination index based on effect) revealed that HP and tocopherol consistently displayed synergistic antioxidant effects (CI = 1.02–1.50) under all tested conditions. This synergistic interaction restored the OSI of STNO from an initial value of 1.50 h to a maximum of 53.11 h, indicating a significant enhancement in oxidative stability (Su et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2025). However, no synergy was observed between HP and sterols (CI = 0.34–0.49). It suggested that HP might not exert antioxidant synergy with all commonly antioxidants (Liu et al., 2025; Tang et al., 2023). This might be attributed to several factors. First, the predominant sterols in tiger nut oil inherently possessed low antioxidant activity, as demonstrated in the previous section (Wang, Xiao, Lyu, Chen, & Wei, 2023). Second, HP and sterols might have competed for the same free radicals, and differences in solubility and dispersibility in the oil matrix existed, which hindered the synergistic interaction (Ma et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). The effective synergistic interaction of HP with tocopherols in TNO, contributing to enhanced oxidative stability. The essence of a synergistic effect lay in the combined action of two components producing a greater outcome than the sum of their individual effects (Suri et al., 2022; Yildiz et al., 2025). This study addressed a previously unresolved issue, namely the marked reduction in OSI observed in TNO after endogenous HP removal despite constant tocopherol levels (Zhang et al., 2024). The explanation lay in the role of endogenous HP as a crucial co-antioxidant in TNO; although it had limited antioxidant capacity individually, it markedly enhanced oxidative stability of TNO through synergistic effects with tocopherols (Golodnizky, Eshaya, Bernardes, & Davidovich-Pinhas, 2025; Liu et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024).

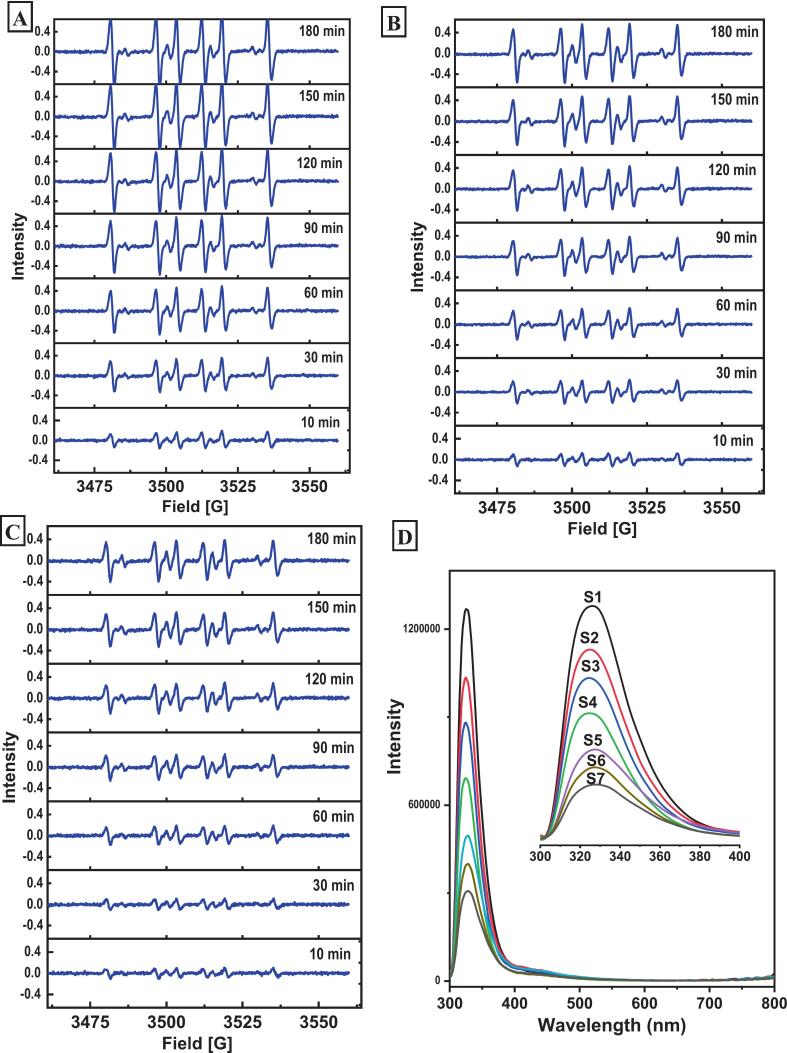

3.5.3. Interactions mechanism of HP–tocopherols in STNO

The synergistic effect of HP and tocopherols in STNO was further analyzed by electron spin resonance spectroscopy and fluorescence spectroscopy. Given the absence of a synergistic interaction between HP and sterols, this combination was excluded from further investigation. The electron spin resonance spectrum of the nitrogen oxide radical adducts formed by DMPO and free radicals is shown in Fig. 6 (A-C). All ESR spectra were similar, suggesting the presence of analogous free radical species in all oil samples. With prolonged heating, signal intensity steadily increased, indicating continuous radical formation (Sun, Huang, Wang, Yu, & Wang, 2024; Tang et al., 2023). At the same heating time, compared to STNO, the STNO supplemented with tocopherols showed clearly reduced signal intensity, and the STNO supplemented both HP and tocopherols exhibited an even lower intensity. This indicates that, under identical conditions, the total spin concentration in STNO supplemented with both HP and tocopherols was markedly lower than that in the other samples (Monto et al., 2023; Shishkina et al., 2023). The reduced free radical content can be attributed to the hydrogen-donating capacity of tocopherols, which effectively scavenges lipid-derived radicals and interrupts the chain propagation reactions of lipid oxidation (Velasco, Andersen, & Skibsted, 2021; Zheng & Huang, 2022). The combined action of HP and tocopherols further enhancing the hydrogen-donating capacity and suppressed radical formation, thereby enhancing oxidative stability. These findings support the earlier conclusion regarding the synergistic effect of HP and tocopherols in inhibiting lipid oxidation (Sun et al., 2024; Tang et al., 2023; Zhu, Luan, Chai, Xue, & Duan, 2025). The fluorescence spectra of oil sample systems containing different contents of HP and tocopherols at different temperatures are shown in Fig. 6D. With the increase in the addition amount of HP, the fluorescence peak intensity of the oil samples decreased significantly. This is because the association reaction between HP and tocopherols led to fluorescence quenching of tocopherols, and because the Stern-Volmer curve showed a non-linear relationship and the slope changed smaller with temperature, it may be static quenching (Zheng & Huang, 2022; Zhu et al., 2025). This result verified that HP and tocopherols can combine and exert a synergistic oxidation effect (Monto et al., 2023). In summary, while endogenous HP of tiger nut oil displayed minimal intrinsic antioxidant capacity, its interaction with tocopherols led to a pronounced synergistic antioxidant effect. This synergistic action significantly outperformed the individual contributions of HP or tocopherols and ultimately significantly enhanced the oxidative stability of TNO. Thus, in the industrial production of tiger nut oil, the strategic retention of certain phospholipids via moderate refining not only improves oxidative stability and reduces processing costs, but also helps preserve nutrients, thereby enhancing overall product quality and extending shelf life.

Fig. 6.

The electron spin resonance spectra and fluorescence spectra of samples. (A-C: The electron spin resonance spectra of STNO, STNO with added tocopherols (0.3 g/kg), and STNO with added HP (6 g/kg)- tocopherols (0.3 g/kg). D: Fluorescence spectra of STNO with added HP-tocopherols, S1-S7 represent STNO with the addition of tocopherols (0.3 g/kg) and different concentrations of HP (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 6.0, 8.0 g/kg)).

4. Conclusion

This study investigated the antioxidant mechanism of endogenous hydratable phospholipids (HP) in tiger nut oil. Although HP exhibited relatively limited intrinsic antioxidant capacity in tiger nut oil, significantly lower than that of tocopherol, it demonstrated a dual functional role. Firstly, HP had the capacity to substantially enhance the thermal stability of tiger nut oil. Secondly, and more importantly, it exhibited a potent synergistic antioxidant effect when combined with tocopherol, which was a pivotal contributor to the TNO's exceptional oxidative stability. The HP-tocopherol complex significantly extended the oxidation induction time of stripped tiger nut oil (STNO) from 1.50 h to 53.11 h within the concentration range tested based on tiger nut oil (TNO), far surpassing the performance of HP alone (1.69–13.68 h) or tocopherol alone (19.27–25.14 h). HP as a critical synergistic enhancer of antioxidants in TNO, also enhanced oxidation induction period of common oils, e.g., soybean oil (5.23 to 17.10 h), olive oil (19.94 to 74.08 h), walnut oil (1.87 to 4.58 h). Therefore, this work revealed the significant potential of tiger nut phospholipids as a novel natural antioxidant. By utilizing their synergistic interactions with other natural antioxidants, it is possible to develop healthier and more antioxidant-rich food systems while reducing the use of more expensive natural antioxidants.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Run-Yang Zhang: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jing-Ru Jia: Visualization, Validation. Chen Liu: Software. Xiao-Shuang Cai: Resources. Peng-Xiao Chen: Formal analysis. Hua-Min Liu: Supervision. Wen-Xue Zhu: Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Plan of China (No. 2019YFD1002605); the National Key Research and Development Plan for Science and Technology Innovation of China (No. SQ2019YFD100114); and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant Number 2024M760794.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2025.102985.

Contributor Information

Run-Yang Zhang, Email: r.y.zhang@haut.edu.cn.

Chen Liu, Email: 1155219733@link.cuhk.edu.hk.

Xiao-Shuang Cai, Email: xiaoshuang.cai@haut.edu.cn.

Peng-Xiao Chen, Email: cpx2020@haut.edu.cn.

Hua-Min Liu, Email: liuhuamin5108@163.com.

Wen-Xue Zhu, Email: zhuwenxue67@126.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Ahmmed M.K., Bunga S., Stewart I., Tian H., Carne A., Bekhit A.E.D.A. Simple and efficient one-pot extraction method for phospholipidomic profiling of total oil and lecithin by phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance measurements. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2020;68:14286–14296. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c05803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabsorkhi B., Pourabdollah E., Mashadi M. Investigating the effect of replacing the antioxidants Ascorbyl palmitate and tocopherol instead of TBHQ on the shelf life of sunflower oil using temperature accelerated method. Food chemistry. Advances. 2023;2, Article 100246 doi: 10.1016/j.focha.2023.100246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X., Zhang Q., Zhou X., Yao J., Wan P., Chen D.W. Use of egg yolk phospholipids to improve the thermal-oxidative stability of fatty acids, capsaicinoids and carotenoids in chili oil. Food Chemistry. 2024;451, Article 139423 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.139423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayram I., Decker E.A. Underlying mechanisms of synergistic antioxidant interactions during lipid oxidation. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2023;133:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2023.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boon C.S., Xu Z., Yue X., McClements D.J., Weiss J., Decker E.A. Factors affecting lycopene oxidation in oil-in-water emulsions. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2008;56(4):1408–1414. doi: 10.1021/jf072929+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Zhang L., Guo X., Qiang J., Cao Y., Zhang S., Yu X. Influence of triacylglycerol structure on the formation of lipid oxidation products in different vegetable oils during frying process. Food Chemistry. 2025;464, Article 141783 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.141783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edo G.I., Samuel P.O., Nwachukwu S.C., Ikpekoro V.O., Promise O., Oghenegueke O.…Ajakaye R.S. A review on the biological and bioactive components of Cyperus esculentus L.: Insight on food, health and nutrition. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2024;104(14):8414–8429. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.13570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golodnizky D., Eshaya E., Bernardes C.E.S., Davidovich-Pinhas M. Insights into the dynamics of edible oil oxidation: From molecular interactions to oxidation kinetics. Food Hydrocolloids. 2025;164, Article 111203 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2025.111203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T., Wan C., Huang F., Wei C. Evaluation of quality properties and antioxidant activities of tiger nut (Cyperus esculentus L.) oil produced by mechanical expression or/with critical fluid extraction. LWT-food. Science and Technology. 2021;141, Article 110915 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.110915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hou N.C., Gao H.H., Qiu Z.J., Deng Y.H., Zhang Y.T., Yang Z.C.…Wang X.D. Quality and active constituents of safflower seed oil: A comparison of cold pressing, hot pressing, Soxhlet extraction and subcritical fluid extraction. LWT-food. Science and Technology. 2024;200:116184. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2024.116184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Koo W.H., Oh W.Y., Myoung S., Ahn S., Kim M.J., Lee J.H. Changes of molecular mobility of ascorbyl palmitate and α-tocopherol by phospholipid and their effects on antioxidant properties in bulk oil. Food Chemistry. 2023;403, Article 134458 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Li Y., Yang F., Liu R., Zhao C., Jin Q., Wang X. Oxidation degree of soybean oil at induction time point under Rancimat test condition: Theoretical derivation and experimental observation. Food Research International. 2019;120:756–762. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wan Y., Wang J., Zhang X., Leng Y., Wang T., Liu W., Wei C. Investigation of the oxidation rules and oxidative stability of seabuckthorn fruit oil during storage based on lipidomics and metabolomics. Food Chemistry. 2025;476, Article 143238 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.143238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Zheng Z., Liu Y. Lipophilic antioxidants in edible oils: Mechanisms, applications and interactions. Food Research International. 2025;200, Article 115423 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.115423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G., Wang Y., Li Y., Zhang L., Gao Y., Li Q., Yu X. Antioxidant properties of lipid concomitants in edible oils: A review. Food Chemistry. 2023;422, Article 136219 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monto A.R., Yuan L., Xiong Z., Shi T., Li M., Wang X.…Gao R. Α-Tocopherol stabilization by soybean oil and glyceryl monostearate made oleogel: Dynamic changes and characterization for food application. LWT-food. Science and Technology. 2023;187, Article 115325 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu L.C., Edo G.I., Özgör E. The phytochemical, proximate, pharmacological, GC-MS analysis of Cyperus esculentus (Tiger nut): A fully validated approach in health, food and nutrition. Food. Bioscience. 2022;46, Article 101551 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2022.101551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porter N.A. Chemical mechanisms of lipid peroxidation. Redox Biochemistry and Chemistry. 2025;12, Article 100054 doi: 10.1016/j.rbc.2025.100054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shishkina L.N., Mazaletskaya L.I., Kozlov M.V., Sheludchenko N.I. Effect of phospholipids on the inhibitory efficiency of natural and synthetic antioxidants in oxidation processes. Russian Chemical Bulletin. 2023;72:1876–1886. doi: 10.1007/s11172-023-3972-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siejak P., Neunert G., Kamińska W., Dembska A., Polewski K., Siger A., Grygier A., Tomaszewska-Gras J. A crude, cold-pressed oil from elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) seeds: Comprehensive approach to properties and characterization using HPLC, DSC, and multispectroscopic methods. Food Chemistry. 2025;464, Article 141758 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.141758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su D., Wang X., Liu X., Miao J., Zhang Z., Zhang Y., Zhao L., Yu Y., Leng K., Yu Y. A comprehensive study of the colloidal properties, biocompatibility, and synergistic antioxidant actions of Antarctic krill phospholipids. Food Chemistry. 2024;451, Article 139469 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.139469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Huang Z., Wang J., Yu D., Wang L. Effect of deodorization conditions on fatty acid profile, oxidation products, and lipid-derived free radicals of soybean oil. Food Chemistry. 2024;453, Article 139656 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.139656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suri K., Singh B., Kaur A. Impact of microwave roasting on physicochemical properties, Maillard reaction products, antioxidant activity and oxidative stability of nigella seed (Nigella sativa L.) oil. Food Chemistry. 2022;368, Article 130777 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L., Cao M., Liao C., Xu Y., Karrar E., Liu R., Chang M. Prolonging oxidation stability of peony (Paeonia suffruticosa Andr.) seed oil by endogenous lipid concomitants: Phospholipids enhance antioxidant capacity by improving the function of tocopherol. Industrial Crops and Products. 2023;197, Article 116552 doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco J., Andersen M.L., Skibsted L.H. ESR spin trapping for in situ detection of radicals involved in the early stages of lipid oxidation of dried microencapsulated oils. Food Chemistry. 2021;341, Article 128227 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Xiao H., Lyu X., Chen H., Wei F. Lipid oxidation in food science and nutritional health: A comprehensive review. Oil Crop Science. 2023;8(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ocsci.2023.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Chen Y., McClements D.J., Meng C., Zhang M., Chen H., Deng Q. Recent advances in understanding the interfacial activity of antioxidants in association colloids in bulk oil. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 2024;325, Article 103117 doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2024.103117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen C., Cao L., Xu X., Liang L., Liu X., Zhang J., Li Y., Liu G. Effect of different phospholipids on the co-encapsulation of curcumin and oligomeric proanthocyanidins in nanoliposomes: Characteristics, physical stability, and in vitro release. Food Chemistry. 2025;487, Article 144721 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.144721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.M., Qin L.K., Zhu Y., He C.Y. The regularity of heat-induced free radicals generation and transition of camellia oil. Food Research International. 2022;157, Article 111295 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda T., Al Sazzad M.D.A., Jäntti N.Z., Pentikäinen O.T., Slotte J.P. The influence of hydrogen bonding on sphingomyelin/colipid interactions in bilayer membranes. Biophysical Journal. 2016;110(2):431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.11.3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz A.Y., Öztekin S., Anaya K. Effects of plant-derived antioxidants to the oxidative stability of edible oils under thermal and storage conditions: Benefits, challenges and sustainable solutions. Food Chemistry. 2025;479, Article 143752 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.143752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S.H. Optimization of the refining process and oxidative stability of chufa (Cyperus esculentus L.) oil for edible purposes. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2016;25(1):85–90. doi: 10.1007/s10068-016-0012-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.H., Zhang S.R., Du Y., Deng D.J., Zhang Y.K., Li J.L.…Cai Z.Z. Impact of cyclolinopeptide (linusorb) on oxidative stability of hot-pressed flaxseed oil and their interaction with phospholipid. Food Chemistry. 2025;482, Article 144110 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.144110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeb A., Ali G., Al-Babili S. Comparative UHPLC-MS/MS-based untargeted metabolomics analysis, antioxidant, and anti-diabetic activities of six walnut cultivars. Food. Bioscience. 2024;59, Article 103885 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.103885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R. Y., Jia, J. R., Chen, P. X., Zhu, W. X., & Liu, H. M. (2025). Moisture adjustment of tiger nuts (Cyperus esculentus L.): A green strategy to enhance crude oil oxidative stability by increasing phospholipid and phenolic contents. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology, 2025, Article e70051. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.70051. [DOI]

- Zhang R.Y., Li J.K., Zhu W.X., Chen P.X., Jiang M.M., Liu H.M. Effect of different degumming methods on the chemical composition and physicochemical properties of tiger nut (Cyperus esculentus L.) oil. Food Quality and Safety, Article fyae034. 2024 doi: 10.1093/fqsafe/fyae034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R.Y., Liu A.B., Liu C., Zhu W.X., Chen P.X., Wu J.Z.…Wang X.D. Effects of different extraction methods on the physicochemical properties and storage stability of tiger nut (Cyperus esculentus L.) oil. LWT-food. Science and Technology. 2023;173, Article 114259 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.114259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Wang D., Yu J., Wang X., Wang T., Yu D., Elfalleh W. Complex phospholipid liposomes co-encapsulated of proanthocyanidins and α-tocopherol: Stability, antioxidant activity and in vitro digestion simulation. Food. Bioscience. 2024;61, Article 104899 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.104899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X., Huang Q. Assessment of the antioxidant activities of representative optical and geometric isomers of astaxanthin against singlet oxygen in solution by a spectroscopic approach. Food Chemistry. 2022;395:133584. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.D., Luan Y.T., Chai C.L., Xue Y.L., Duan Z.Q. Effects of high-temperature stages on the physicochemical properties and oxidation products formation of rapeseed oil with carnosic acid. Food Chemistry. 2025;465, Article 141960 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.141960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.