ABSTRACT

Background

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a potentially life-threatening, systemic autoimmune disease with a high risk for relapse and treatment-related toxicity, making AAV a high-costs illness. This study aimed to identify clinical insights for clinicians on considering this costs burden.

Methods

We conducted a detailed, retrospective, single-centre, activity-based cost-analysis and identified clinical variables associated with increased costs. We analysed real-world costs incurred by the hospital between January 2018 and December 2019, omitting the outpatient pharmacy expenditures. Our cohort included both incident and prevalent AAV patients with at least 6 months of follow-up since diagnosis, indicating survival beyond initial diagnosis.

Results

For 180 AAV patients with a median follow-up of 1.8 years the average hospital costs incurred amounted to €9887 per patient year, with inpatient care being the primary cost driver (32%). Merely 15% of costs were attributable to patients experiencing relapse (N = 14/180, 8%). More importantly, 71% of costs were attributable to patients experiencing infections (N = 77/180, 43%). Likewise, 60% of costs were attributable to patients with multi-comorbidity (N = 65/180, 36%). Infections and multi-comorbidity were both strongly associated with corticosteroid (CS) use. Regression and sensitivity analyses suggest that a reduction of infections, comorbidities and maintenance treatment with CS will reduce hospital costs.

Conclusion

This real-world cost analysis demonstrates that the burden of infections and comorbidities, both related to CS use, is higher than that of relapses on hospital costs in AAV patients. Thus, this study implicates clinicians considering hospital costs should focus on reducing CS and achieving CS-free remission to prevent infections and comorbidities.

Keywords: ANCA-associated vasculitis, corticosteroids, healthcare costs, pauci-immune glomerulonephritis, systemic autoimmune disease

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT.

KEY LEARNING POINTS.

What was known:

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a high burden, high costs disease and the current guidelines mention to consider costs during the management of AAV patients.

Claim-based studies determined high hospital costs in AAV can be related to disease activity and inpatient care.

However, there is currently no clear overview of all detailed costs combined with clinical details, which is essential to provide practical guidance for clinicians.

This study adds:

This study is the first highly detailed, activity-based cost analysis in AAV providing clinicians with valuable insights to cost drivers of hospital costs.

Moreover, this study is the first to determine the burden of corticosteroid (CS)-related infections and comorbidities is higher than the burden of disease relapses on hospital costs of AAV patients.

Potential impact:

These results implicate that, in line with trends of reducing CS to avoid toxicity, clinicians who wish to consider hospital costs during the management of AAV patients, should not merely focus on preventing AAV relapses, but more so on discontinuation of CS during maintenance treatment.

As a result, hospital costs can be effectively reduced by diminishing infections and accrual of comorbidities related to CS.

INTRODUCTION

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmatic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a rare, potentially life-threatening, systemic autoimmune disease, characterized by high relapse rate requiring life-long, multidisciplinary care [1–3]. The use of immunosuppressive drugs such as rituximab and cyclophosphamide has tremendously decreased the mortality of AAV [1, 3]. However, long-term complications require increasing attention since disease and treatment put AAV patients at high risk for organ damage, treatment toxicity, (cardiovascular) comorbidities and infections [1–4]. Currently, new treatment strategies have demonstrated the potential to reduce corticosteroids (CS) during remission induction treatment (RIT), which prevented CS-related comorbidities and decreased the risk for mild and severe infections [5–9].

Altogether, AAV patients are prone to become high-burden, high-cost patients [1]. Not surprisingly, the international European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology/American College of Rheumatology (EULAR/ACR) guidelines emphasize considering costs during the management of AAV patients within the overarching principles [1]. It remains, however, enigmatic in clinical practice where clinicians should focus on when considering hospital costs. Several claim-based studies have linked high hospital costs in AAV to disease activity and inpatient care [4, 10–15]. One study determined that inpatient costs were primarily driven by AAV activity or infections [14]. Other studies observed higher hospital costs in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) patients, ANCA-positive patients, patients using CS and patients with multimorbidity [4, 13, 14]. However, although claim-based cost analyses provide easily accessible data from large patient populations due to routine billing processes, they lack detailed clinical insights and represent reimbursed rather than actual incurred hospital costs. Additionally, using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes for patient selection is problematic due to their low accuracy for rare diseases including AAV [16–18]. Many of these shortcomings are overcome in activity-based cost (ABC) analyses where actual costs incurred by the hospital are determined based on a detailed analysis of all activities involved during hospital care. By design, ABC analyses rely upon accurately selected patient cohorts with access to highly granular clinical data, creating the opportunity to identify relevant cost drivers [19]. ABC analyses are considered to more reliably assess healthcare cost, enhancing clinical significance and thereby aiding clinicians in managing AAV patients [20–22].

Therefore, the present study conducted an ABC analysis based on real-world incurred hospital costs for a substantial AAV cohort combined with high-granular clinical data. To overcome ICD-10 limitations, we assembled a cohort of AAV patients with a confirmed clinical AAV diagnosis, previously identified within electronic health records (EHR) using a highly accurate method based on natural language processing (NLP) [18]. The aim was to determine relevant cost drivers and clinical variables associated with high costs, focusing on preventable variables to support clinicians’ decision-making in managing AAV patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and clinical data

We previously identified 350 patients with a clinical diagnosis of AAV using a NLP-based method, where patients were identified based on the AAV diagnosis mentioned in physician correspondence, followed by manual review to confirm the clinical diagnoses. This method had a sensitivity of 95% and was superior to ICD-10 coding, thereby avoiding bias introduced by inaccurate ICD-10 coding [18]. A total of 337 patients gave permission for the use of their medical data for healthcare evaluation. We included all patients with a hospital visit between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2019. Hospitalizations between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2019 were manually reviewed and categorized as admissions related to AAV, infections or other causes. All clinical data was extracted using the validated artificial intelligence (AI) text mining tool CTcue data collector (v4.8.1) [18, 23, 24].

ABC analysis

We performed an ABC analysis from the clinician's and hospital's perspective for hospital costs related to direct patient care. Indirect and fixed costs, such as overhead and housing, were excluded. Activities were identified based on registered clinical procedures.

Briefly, clinical procedures are automatically registered with a code in the EHR. We extracted all codes from 1 January 2018 until 31 December 2019 for all AAV patients using the CTcue data collector (v4.8.1). We removed codes for administrative registrations (not related to clinical procedures) and codes registered more than 3 months before the date of AAV diagnosis. To avoid extrapolating data from patients with a short follow-up or patients temporarily transferred from other hospitals for second opinions or complications, we also excluded codes from patients with a follow-up time of <6 months. Follow-up time was calculated as the time between the first and last registered procedure code between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2019.

Subsequently, all registered clinical procedures were matched with cost prices listed in ABC models for the corresponding year the costs were made. ABC models are each year created by the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) financial department by allocation of all actual incurred costs across clinical procedures. Costs per patient year were calculated for each patient by summation of all procedures’ cost prices divided by the patient's follow-up time.

Largest cost drivers were determined based on pre-defined expenditure categories applied to all clinical procedures: inpatient care (i.e. hospitalizations, excluding medical procedures), outpatient care (excluding medical procedures), therapeutic interventions, surgical interventions, laboratory diagnostics, radiological diagnostics, other diagnostics, dialysis or other. Importantly, medication issued by the out-patient pharmacy were not included in this study. Medication prescribed during inpatient care or during 1-day admissions (outpatient treatments) were embedded within inpatient care costs. While drugs categorized as ‘expensive drugs’ according to the Dutch National Healthcare Institute were reported and calculated separately within therapeutic interventions [25].

Cost allocation analyses

First, we aimed to identify subgroups of patients responsible for large and disproportional proportions of costs on cohort level. Therefore, we performed a costs allocation analysis where proportions of costs were compared with proportions of patients. Based on previously reported cost analysis studies, relevant subgroups were defined based on clinical variables as specified in Supplementary data, Table S1. Subsequently, for variables with disproportionate costs, the correlation between the variable and hospital costs was determined.

Descriptive exposure analysis

For comorbidity and infections (the subgroups attributing to the highest disproportional proportions of costs) we performed a descriptive exposure analysis. In this analysis we determined the association between the clinical variable and two possible canonical risk factors to identify key determinants of these subgroups.

Additionally, to account for cofounding in their correlation with hospital costs, all variables were included as covariates in a multivariable logistic regression analysis.

Sensitivity analyses

To further identify clinical variables with potency of reducing hospital costs, we performed a deterministic sensitivity analyses including relevant and possibly modifiable clinical variables detected in the allocation and/or exposure analysis. In this sensitivity analysis we modeled the effects on cost reductions when the frequency of patients encountering an event would change by ±20% relatively, while other parameters are kept constant. To determine the change in costs for these patients we used the difference between the mean costs per patient with or without the event. Based on these changes in costs we estimated the percentual impact on overall costs resulting from the ±20% change in frequency.

Additionally, a post-hoc power analysis was performed to determine the group size necessary to detect a significant difference in costs based on different treatment regimens.

Statistical analyses

Proportions were compared using the Pearson χ2 with a P < .05 considered significant. Correlation was determined for ordinal variables using the Spearman's rank correlation. Multivariable logistic regression was performed with high costs (defined as above the median) as dependent outcome. Associations are expressed as odds ratios with the 95% confidence intervals and P-values. Discrimination ability was assessed using the c-statistic. Post-hoc power analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney U test to detect non-parametric differences between two groups with a power of 80% and an alpha of 5%. All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (v4.2.1; R Core Team 2022) and R-studio (version 2022.02.3, R Studio Team 2022).

RESULTS

ABC analysis

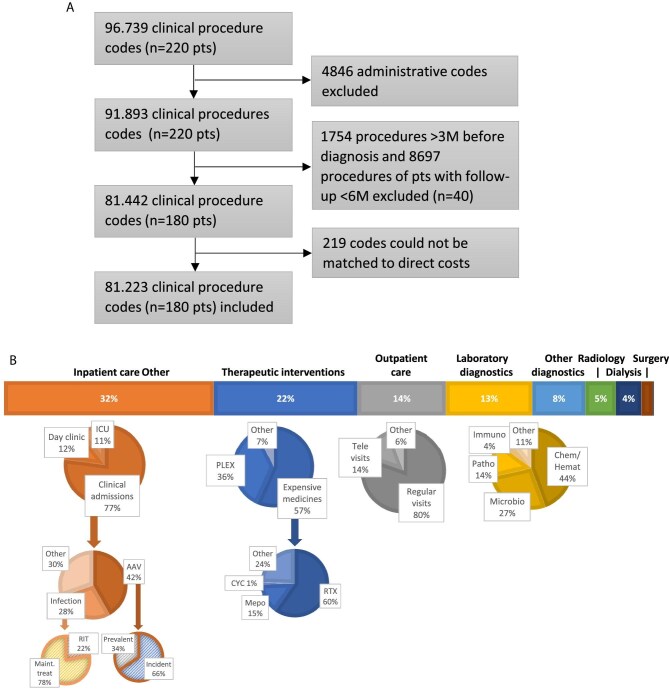

We identified 220 AAV patients who visited the hospital between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2019. After exclusion of 40 patients because of a follow-up time <6 months (including four patients who died during follow up), we included 81 223 procedures of 180 patients for the ABC analysis (Fig. 1A). The median follow-up time was 1.8 years (IQR 1.2–1.9) and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 149 (83%) patients were previously diagnosed (prevalent patients) and 31 (17%) patients received a AAV diagnosis during follow-up (incident patients). Mean costs per patient year were €9887 (SD €13 326).

Figure 1:

Activity based costs analysis for AAV. (A) Flow chart for inclusion of clinical procedures. (B) Hospital expenditures across and within expenditure categories. Chem/Hemat, chemistry and hematology; CYC, cyclophosphamide; ICU, intensive care unit; Immuno, immunology; M, months; Maint. treat, maintenance treatment; Microbio, microbiology; Mepo, mepoluzimab; n, number; Patho, pathology; PLEX, plasmapheresis; pts, patients; RTX, rituximab.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics.

| Total (n = 180) | |

|---|---|

| Sex: female, n (%) | 67 (37) |

| Age (at baseline), median (IQR) | 65 (50; 73) |

| Clinical diagnosis, n (%) | |

| GPA | 122 (68) |

| MPA | 43 (24) |

| EGPA | 15 (8) |

| Serology, n (%) | |

| PR3+ | 108 (60) |

| MPO+ | 61 (34) |

| ANCA– | 11 (6) |

| Prevalent patients, n (%) | 149 (83) |

| Disease years, median (IQR) | 7 (2; 15) |

| Historic relapses, median (IQR) | 1 (1; 2) |

| Incident patients, n (%) | 31 (17) |

| Disease severity, n (%) | |

| No major organ | 18 (10) |

| One major organ | 74 (41) |

| Multiple major organs | 88 (49) |

| Major disease activity, n (%) | 42 (23) |

| Treatment, n (%) | |

| RIT | 42 (23) |

| CS + IS | 57 (32) |

| CS-only | 25 (14) |

| IS-only | 26 (14) |

| None | 30 (17) |

| Comorbidities, median (IQR) | 1 (0; 2) |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 76 (42) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 60 (33) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 28 (16) |

| Obesity, n (%) | 44 (24) |

| Infections, n (%) | 75 (42) |

| Bacterial infections | 47 (26) |

| Viral infections | 51 (28) |

| Immune status, n (%) | |

| Secondary immunodeficiency | 39 (22) |

| No immunodeficiency | 141 (78) |

MPA, microscopic polyangiitis; MPO, myeloperoxidase; PR3, proteinase 3.

Figure 1B illustrates the distribution of incurred hospital costs across expenditure categories and subcategories. The largest cost driver was inpatient care (32%), which could be further divided into costs for clinical admissions (77%), 1-day admissions (12%) and intensive care unit admissions (11%). Clinical admission days (and their costs) were for 42% related to AAV and for 28% related to infections. Interestingly, 66% of AAV admission days occurred in newly diagnosed patients and 78% of infection-related admission days in patients on maintenance treatment. Noteworthy, within laboratory diagnostics, immunology measurements, including ANCA titres and immunoglobulins, only accounted for 4% of the costs.

Cost allocation analyses

We next set out to identify subsets of AAV patients whose costs were disproportional high relative to the proportion of patients. We observed small but significant difference in cost-distribution based on age (P = .008), time of diagnosis (P < .001) and history of relapses (P = .02), but not based on sex (P = .75), diagnosis (P = .71), ANCA serology (P = .59) or number of involved major organs (P = .10) (Fig. 2A and Supplementary data, Fig. S1A).

Figure 2:

Comparison between proportions of patients and proportions of costs, in clinically defined subgroups based on A) baseline characteristics, B) disease activity and C) complications. Statistical significant disproportion between the proportions of patients (left side each graph) and the proportions of costs (right sight of each graph) was determined using the Pearson χ2 test and the P-value is presented above each graph. P-values <.05 are considered significant and are presented in bold. For characteristics with significant disproportion, the correlation coefficient was determined using Spearman's rho (ρ) (D). MDA, major disease activity; MPA, microscopic polyangiitis; Pts, patients.

When dividing patients based on disease activity, patients with major disease activity were responsible for a large and disproportional portion of costs: the 23% of patients experiencing major disease activity were responsible for 50% of overall costs (P < .001, Fig. 2B). However, there was no difference in cost distribution between relapsing or newly diagnosed patients (P = .48). As such, the 8% of relapsing patients were responsible for only 15% of overall costs. Conversely to major disease activity, the 77% of patients without major disease activity attributed to the remaining 50% of overall costs. Within this subset, disproportional high costs were attributable to patients treated with immunosuppressives and CS (IS + CS) or CS-only (P < .001). No differences in cost distribution were seen based on seroconversion (P = .20, Supplementary data, Fig. S1B).

With respect to complications (Fig. 2C), we observed high and disproportional costs for patients who encountered an infection (P < .001) and multiple comorbidities (P < .001). Specifically, 71% of overall costs were attributable to the 42% AAV patients who encountered an infection. The 36% of patients with two or more comorbidities attributed to 60% of overall costs. Importantly, for all subgroups with disproportional high costs, the largest proportional increase was seen in inpatient-costs (Supplementary data, Fig. S2).

Correlation analysis confirmed disease activity, treatment, infections and comorbidity to have a moderate-to-strong correlation with hospital costs (Fig. 2D).

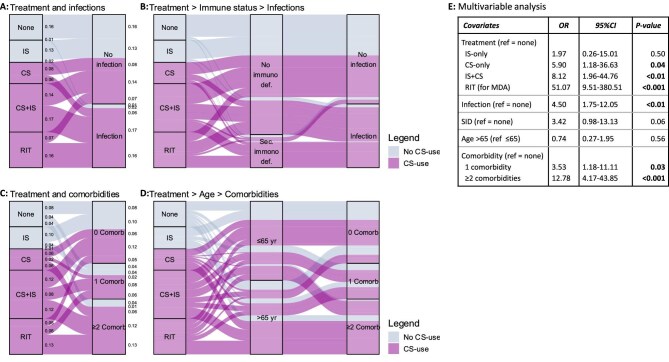

Descriptive exposure analyses

Because patients encountering infections and patients with multimorbidity stood out as subgroups with disproportional and high costs, we determined the association with two risk factors mentioned in the current guidelines, i.e. treatment and immunodeficiencies (hypogammaglobulinemia and leucopenia) for infections and treatment and age for comorbidities [1, 2].

We found infection rates were prominent higher in patients who used CS, either as part of RIT (69%; n = 29/42) or as CS + IS treatment (54%; n = 31/57) or as CS-only treatment (40%; n = 10/25). Infection rates were notably lower in patients who did not use CS, i.e. IS-only treatment (12%; n = 3/26) or no maintenance treatment (7%; n = 2/30) (Fig. 3A). Consequently, 93% (n = 70/75) of patients with an infection used CS with only 39% (n = 29/75) having major disease activity. Similarly, infections also occurred more frequently in patients with a secondary immunodeficiencies (79%; n = 31/39) than in patients without any signs of an immunodeficiency (31%; n = 44/141). When combining both CS use and secondary immunodeficiency as determinants for infection, 40% (n = 30/75) used CS and had a secondary immunodeficiency, 53% (n = 40/75) used CS but had no secondary immunodeficiency, 1% (n = 1/75) had an immunodeficiency but did not use CS and 5% (n = 4/75) did not use CS and had no immunodeficiency (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3:

Association between treatments and complications (A–D) and their correlation to high hospital costs in a multivariable analysis (E). Comorb, comorbidity; immuno def, immunodeficiency; MDA, major disease activity; sec, secondary; SID, secondary immunodeficiency; yr, years.

Similarly, multi-comorbidity (two or more) was detected more often in patients with CS use (46%; n = 56/123) than in patients without CS-use (16%; n = 9/57) (Fig. 3C). Consequently, 86% (n = 56/65) of patients with two or more comorbidities used CS with only 35% (n = 23/65) having major disease activity. Similarly, multi-comorbidity also occurred more in older (≥65 years) patients (53%; n = 46/87), compared with younger patients (20%; n = 19/93). It is noteworthy that, when combining both CS use and age as determinants of multi-comorbidity, 60% (39/65) used CS and were ≥65 years, 26% (n = 17/65) used CS and were <65 years, 11% (n = 7/65) were ≥65 years but did not use CS, and 3% (n = 2/65) were <65 years and did not use CS. The relative importance of CS was emphasized by the observation that 89% (n = 17/19) of patients <65 years with two or more comorbidities used CS (Fig. 3D).

Lastly, we combined all variables with a moderate-to-strong correlation and their risk factors in one multivariable model. In this model major disease activity (with RIT), treatment with CS or CS + IS, infection, and one, or two or more comorbidities remained significantly associated with high hospital costs. The multivariable model had a high discrimination ability with a c-statistic of 0.93.

Sensitivity analyses

The potency of reducing hospital costs was endorsed in a sensitivity analysis which showed reducing infections by 20% could lower hospital costs by 9.9% (Fig. 4). Significant cost reductions were also projected with a 20% decrease in patients with multi-comorbidities (–7.6%), patients with CS as maintenance treatment (–6.9%) and those with secondary immunodeficiency (–6.3%). Lesser impacts were seen with a 20% reduction in patients using IS (–3.5%) and those with major relapses (–1.6%).

Figure 4:

Sensitivity analysis for impact of proportion of patients with a particular clinical characteristic on hospital costs. MDA, major disease activity; pts, patients; sec. immuno def, secondary immunodeficiency.

Post-hoc power analyses indicated two groups of 19 patients are needed to determine a significant difference in costs per year between patients with or without CS maintenance treatment. Also, for IS maintenance treatment two groups of 84 are needed. Both results corroborated the reliability of the observed results in this study.

DISCUSSION

In this first ABC analysis study on real-world hospital costs of AAV patients, we demonstrated that the highest proportion of costs were attributable to the care for AAV patients with infections and multi-comorbidity, both closely intertwined with CS use. As a result significant cost reductions were projected not only when infections and comorbidities were reduced but also when CS use was discontinued as maintenance treatment. Consequently, our study clearly indicates practicing clinicians can significantly reduce hospital costs in AAV patients by minimalizing CS use in order to prevent infections and accrual of comorbidities.

Reducing cumulative CS dose in the management of AAV has gained attention and endorsement in recent years mainly because of reduced short-term and long-term toxicity while maintaining equivalent efficacy [5–9]. However, thus far, the impact of avoiding CS use on hospital costs was not yet clearly demonstrated.

Indeed, our study is the first to conduct an ABC analysis in a large cohort of AAV patients while allowing in-depth, comprehensive analyses at individual level. There are several strengths to the approach in this study. First, we included actual hospital costs for all clinical activities in AAV patients. Despite global variations in currencies and healthcare costs, ABC analyses focus on patient-specific activities, making cost ratios comparable. Since the utilization and cost ratios of activities are likely similar across healthcare systems, this approach allows for reliable extrapolation to other hospitals by identifying high-cost drivers rather than specific monetary values [19–22]. Second, unlike claim-based studies, our ABC analysis used confirmed clinical diagnoses of AAV and AAV subtypes, reducing well-described selections bias and inaccuracies from ICD-10 coding [18]. Accurate and consistent selection is especially crucial in heterogenous diseases like AAV to avoid inclusion bias. We found no cost differences between GPA, microscopic polyangiitis or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) patients, suggesting cost differences previous reported by Italian and Korean studies may be due to selection bias, as also noted by Degli Esposti et al. [13, 14, 26]. Third, using a validated AI-based text-mining tool, we gathered extensive EHR data at a detailed level for individual AAV patients [23, 24]. Together, our comprehensive approach addresses hospital costs and clinical variables relevant to clinicians’ practice, enhancing the reliability and generalizability of our results, and potentially impacting clinical practice for AAV management.

Most remarkably, this study is the first to reveal that patients with infectious events, rather than patients with relapses, have the highest impact on hospital cost. Due to the relative high frequency of infectious events occurring in an AAV patient cohort, a potentially large cost reduction can be achieved if infections are prevented. We were not only able to confirm immunosuppressive treatment, especially CS use, and secondary immunodeficiencies are risk factors associated with infections, but we also showed an association of these risk factors with costs. Therefore, our results can impact clinicians’ clinical practice because potential therapeutic strategies such as monitoring immunodeficiencies, quickly tapering or avoiding CS or prescribing of prophylactic antibiotics can now be considered in AAV patients with these risk factors in order to reduce overall hospital costs [1, 2].

Importantly, the highest number of infectious events and related hospital admissions occurred in AAV patients who did not receive a RIT for major disease activity, but used CS as maintenance treatment. Indeed, the role of continuing versus stopping low-dose CS during maintenance treatment is unclear and in real-world practice AAV patients often remain on low-dose CS as part of maintenance treatment [1, 2, 6–9, 27–29]. Recently, the randomized, controlled TAPIR study demonstrated no beneficial impact of long-term continuation of low-dose CS over discontinuation of CS on relapse risk in patients with a rituximab-based treatment [30]. Now we also demonstrated the negative impact of low-dose CS during maintenance treatment on hospital costs in our sensitivity analysis. Our post-hoc power analysis also shows this effect is expected to be seen in small study populations and therefore hospital costs might be an interesting endpoint for studies investigating different CS regimens and/or CS sparing agents such as avacopan. Taken together, aiming for a CS-free maintenance therapy in AAV is not only proven to be safe with equivalent efficacy but will also reduce hospital costs.

In addition to patients with infections, we also determined a high impact of patients with comorbidities on hospital costs, which is in line with the study by Sarica et al. [4]. We observed a clinically significant association between current CS use and comorbidities, which is in line with studies that showed reducing CS use reduces the prevalence of comorbidities [5–7, 9, 28]. Importantly, the correlation between CS use and multiple comorbidities was most pressing in younger patients, where the long-term impact can be even more devastating. Just as with infections, comorbidities occurred in patients on maintenance treatment rather than patients with RIT for major disease activity.

Another important finding of this study was that, contrary to infections, preventing relapses had a very limited impact on hospital costs for AAV. In line with previous studies, inpatient care was the largest cost driver and was often related to AAV activity. However, most inpatient costs were attributable to newly diagnosed AAV patients. So although relapsing patients had disproportional high costs, the impact on overall costs remained limited due to the low absolute number of relapsing patients. Moreover, the preventability of relapses to reduce costs remains a subject of research [4, 10–14], notwithstanding that preventing relapses remains pivotal, given the high disease burden of relapses in AAV and the ever increasing risks of immunosuppression-related adverse events [1, 2]. However, our study results prompt the need of adequate cost-effectiveness studies in case of new therapeutics for AAV, where cost reductions due to prevention of relapses and treatment-related complications should be weighed.

The present study has some limitations. First, we analysed hospital costs in a single referral centre without taking into account costs incurred outside the hospital. Additionally, we excluded patients with a follow-up of <6 months to reduce the impact of extrapolation of costs made in a small time window. This may have resulted in exclusion of severe patients who died, potentially biasing our result. However, this bias is probably limited because only four excluded patients died and costs for these patients could be both very high due to prolonged hospital stays or considerably low if the disease progresses rapidly leading to a short hospital stay. Second, caution is needed when interpreting the sensitivity analyses, as we assumed a causal link between changes in clinical parameters and costs, without accounting for the costs to achieve these changes. These assumptions may have overestimated the impact on costs although the relative contribution of each parameter can be compared. Thirdly, we could not analyse pharmacy costs in detail, because costs of the outpatient pharmacy were not included and inpatient pharmacy costs were embedded within the inpatient care costs, with the exception of expensive drugs. Fourthly, data on comorbidities and infections were not based on manual chart review, but based on automatically collected derivatives such as prescriptions or laboratory results. We mitigated false-positives by only including prescriptions started or repeated during follow-up and affirmed infections. Lastly, not all details on disease and treatment could be extracted from the EHR, including minor disease activity, cumulative CS dosages and chronological relationship between events (such as infections and treatments).

Although this study gives clear insights in the cost drivers of AAV, additional research is needed to compare the real-world impact of new and different treatment strategies on hospital costs. In line with the considerations of Berdunov et al., this study underscores the importance of including long-term impact due to complications such as infections and comorbidities when comparing effects between different treatments [31]. Future studies should focus on comparing the effects of rituximab- and cyclophosphamide-based regimens and determining impact of avacopan. Recently, a costs projection study predicted avacopan to be cost effective, but this should be confirmed in a study or in real-world data [32]. Moreover, EGPA might be studied as a separate entity given the different treatment regimens, however collection of a larger cohort size would be needed. Lastly, future studies should try to incorporate patient-reported outcomes, quality of life and work productivity in costs analysis. In conclusion, this real-world ABC analysis provides clear insights that can help clinicians to consider hospital costs during the management of AAV in routine clinical practice, as recommended by current guidelines. This study clearly demonstrated that the highest hospital costs can be attributed to AAV patients encountering infections and multi-comorbidity, more so than patients who experienced a disease relapse. We confirmed CS use and secondary immunodeficiency as relevant risk factors for infections, which can be utilized to identify patients where extra preventive measures should be implemented. More importantly, we determined discontinuing of CS during maintenance treatment could provide a treatment strategy with equivalent efficacy, while substantially reducing hospital costs and reducing the risks of infections and comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There was no funding source for this study.

Contributor Information

Jolijn R van Leeuwen, Center of Expertise for Lupus-, Vasculitis- and Complement-mediated Systemic diseases (LuVaCs), Department of Internal Medicine – Nephrology section, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands.

Frouzan H Soltani, Center of Expertise for Lupus-, Vasculitis- and Complement-mediated Systemic diseases (LuVaCs), Department of Internal Medicine – Nephrology section, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands.

Wilbert B van den Hout, Department of Medical Decision Making, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands.

Ton J Rabelink, Center of Expertise for Lupus-, Vasculitis- and Complement-mediated Systemic diseases (LuVaCs), Department of Internal Medicine – Nephrology section, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands.

Y K Onno Teng, Center of Expertise for Lupus-, Vasculitis- and Complement-mediated Systemic diseases (LuVaCs), Department of Internal Medicine – Nephrology section, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

J.R.L. contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation and writing. F.H.S. contributed to study design and data interpretation. W.B.H. contributed to study design, data interpretation and writing. T.J.R. contributed to study design and data interpretation. Y.K.O.T. contributed to study design, data analysis, data interpretation and writing.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

No patient data collected in this study will be available for sharing.

Conflict of interest statement

The work of Y.K.O.T. is supported by the Arthritis Research and Collaboration Hub (ARCH) foundation. ARCH is funded by Dutch Arthritis Foundation (ReumaNederland). The LUMC received an unrestricted research grant from GlaxoSmithKline, Aurinia Pharmaceuticals and Vifor Pharma for investigator-initiated studies conducted by Y.K.O.T. The LUMC received consulting fees from Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, GSK, KezarBio, Vifor Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals on consultancies delivered by Y.K.O.T.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hellmich B, Sanchez-Alamo B, Schirmer JH et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of ANCA-associated vasculitis: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2024;83:30–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) ANCA Vasculitis Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA)-Associated Vasculitis. Kidney Int 2024;105:S71–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kitching AR, Anders HJ, Basu N et al. ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6:71. 10.1038/s41572-020-0204-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sarica SH, Gallacher PJ, Dhaun N et al. Multimorbidity in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: results from a longitudinal, multicenter data linkage study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73:651–9. 10.1002/art.41557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patel NJ, Jayne DRW, Merkel PA et al. Glucocorticoid Toxicity Index scores by domain in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis treated with avacopan versus standard prednisone taper: post-hoc analysis of data from the ADVOCATE trial. Lancet Rheumatol 2023;5:e130–8. 10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00030-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jayne DRW, Merkel PA, Schall TJ et al. Avacopan for the treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2021;384:599–609. 10.1056/NEJMoa2023386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pepper RJ, McAdoo SP, Moran SM et al. A novel glucocorticoid-free maintenance regimen for anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58:373. 10.1093/rheumatology/kez001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Walsh M, Merkel PA, Peh CA et al. Plasma exchange and glucocorticoids in severe ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2020;382:622–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1803537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Furuta S, Nakagomi D, Kobayashi Y et al. Reduced-dose versus high-dose glucocorticoids added to rituximab on remission induction in ANCA-associated vasculitis: predefined 2-year follow-up study. Ann Rheum Dis 2024;83:96–102. 10.1136/ard-2023-224343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bell CF, Blauer-Peterson C, Mao J. Burden of illness and costs associated with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: evidence from a managed care database in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2021;27:1249–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raimundo K, Farr AM, Kim G et al. Clinical and economic burden of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis in the United States. J Rheumatol 2015;42:2383–91. 10.3899/jrheum.150479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thorpe CT, Thorpe JM, Jiang T et al. Healthcare utilization and expenditures for United States Medicare beneficiaries with systemic vasculitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018;47:507–19. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Degli Esposti L, Dovizio M, Perrone V et al. Profile, healthcare resource consumption and related costs in ANCA-associated vasculitis patients: a real-world analysis in Italy. Adv Ther 2023;40:5338–53. 10.1007/s12325-023-02681-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quartuccio L, Treppo E, Valent F et al. Healthcare and economic burden of ANCA-associated vasculitis in Italy: an integrated analysis from clinical and administrative databases. Intern Emerg Med 2021;16:581–9. 10.1007/s11739-020-02431-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu X, Edmonds C, Kim Y et al. Disease Overlap, healthcare resource utilization, and costs in patients with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a REVEAL sub-study. Rheumatol Ther 2024;11:1611–28. 10.1007/s40744-024-00714-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernatsky S, Linehan T, Hanly JG. The accuracy of administrative data diagnoses of systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1612–6. 10.3899/jrheum.101149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mettler C, Bouam S, Liva-Yonnet S et al. Validation of anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies associated vasculitides diagnosis codes from the electronic health records of two French university hospitals. Eur J Intern Med 2022;103:115–7. 10.1016/j.ejim.2022.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Leeuwen JR, Penne EL, Rabelink T et al. Using an artificial intelligence tool incorporating natural language processing to identify patients with a diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis in electronic health records. Comput Biol Med 2024;168:107757. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jalalabadi F, Milewicz AL, Shah SR et al. Activity-based costing. Semin Plast Surg 2018;32:182–6. 10.1055/s-0038-1672208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clement Nee Shrive FM, Ghali WA, Donaldson C et al. The impact of using different costing methods on the results of an economic evaluation of cardiac care: microcosting vs gross-costing approaches. Health Econ 2009;18:377–88. 10.1002/hec.1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Onukwugha E, McRae J, Kravetz A et al. Cost-of-illness studies: an updated review of current methods. Pharmacoeconomics 2016;34:43–58. 10.1007/s40273-015-0325-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wordsworth S, Ludbrook A, Caskey F et al. Collecting unit cost data in multicentre studies. Creating comparable methods. Eur J Health Econ 2005;6:38–44. 10.1007/s10198-004-0259-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Dijk WB, Fiolet ATL, Schuit E et al. Text-mining in electronic healthcare records can be used as efficient tool for screening and data collection in cardiovascular trials: a multicenter validation study. J Clin Epidemiol 2021;132:97–105. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Laar SA, Kapiteijn E, Gombert-Handoko KB et al. Application of electronic health record text mining: real-world tolerability, safety, and efficacy of adjuvant melanoma treatments. Cancers 2022;14:5426. 10.3390/cancers14215426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/over-ons/programmas-en-samenwerkingsverbanden/horizonscan-geneesmiddelen/sluis-voor-dure-geneesmiddelen (5 June 2024, date last accessed).

- 26. Ahn SS, Lim H, Lee CH et al. Secular Trends of incidence, prevalence, and healthcare economic burden in ANCA-associated vasculitis: an analysis of the 2002-2018 South Korea National Health Insurance Database. Front Med 2022;9:902423. 10.3389/fmed.2022.902423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Walsh M, Merkel PA, Mahr A et al. Effects of duration of glucocorticoid therapy on relapse rate in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:1166–73. 10.1002/acr.20176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Robson J, Doll H, Suppiah R et al. Glucocorticoid treatment and damage in the anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitides: long-term data from the European Vasculitis Study Group trials. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54:471–81. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Floyd L, Morris A, Joshi M et al. Glucocorticoid therapy in ANCA vasculitis: using the Glucocorticoid Toxicity Index as an outcome measure. Kidney360 2021;2:1002–10. 10.34067/KID.0000502021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Merkel P, Pagnoux M, Khalidi N et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial evaluating the effects of low-dose glucocorticoids compared to stopping glucocorticoids to maintain remission of granulomatosis with polyangiitis: the TAPIR trial. In: 21st International Vasculitis Workhop Abtracts book, Zenodo; 2024. [Internet] https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11068008. Available from: https://vasculitis-barcelona2024.com/index.php/abstracts/abstracts-book (10 November 2024, date last accessed).

- 31. Berdunov V, Ramirez de Arellano A, Li T et al. Key considerations for modelling the long-term costs and benefits of treatments for ANCA-associated vasculitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2024;42:782–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Macia M, Diaz-Encarnacion M, Solans-Laque R et al. A projected cost-utility analysis of avacopan for the treatment of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis in Spain. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2024;24:227–35. 10.1080/14737167.2023.2297790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Merkel P, Pagnoux M, Khalidi N et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial evaluating the effects of low-dose glucocorticoids compared to stopping glucocorticoids to maintain remission of granulomatosis with polyangiitis: the TAPIR trial. In: 21st International Vasculitis Workhop Abtracts book, Zenodo; 2024. [Internet] https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11068008. Available from: https://vasculitis-barcelona2024.com/index.php/abstracts/abstracts-book (10 November 2024, date last accessed).

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No patient data collected in this study will be available for sharing.