Abstract

Aims

The SUPPRESS-AF trial showed that pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) plus low-voltage area (LVA) ablation may reduce atrial fibrillation (AF) recurrence in some subgroups. Renal dysfunction is a cause of LVAs due to atrial cardiomyopathy and is also a risk factor for AF recurrence after catheter ablation. The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy of LVA ablation after PVI stratified by renal function.

Methods and results

This study was a sub-analysis of the SUPPRESS-AF trial, a multicentre, prospective, randomized, open-label trial. A total of 341 consecutive patients who underwent initial radiofrequency catheter ablation for persistent AF and whose LVAs were ≥5 cm2 were analysed. Patients were randomized to PVI alone (PVI-alone group) or LVA ablation after PVI [PVI + LVA-ablation (ABL) group]. Primary outcome was defined as the recurrence of atrial tachyarrhythmias during the 12 months following ablation. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was assessed before ablation, and patients were stratified by chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage. The mean eGFR was 60 ± 16 mL/min/1.73 m2, and 146 (43%) patients developed the primary outcome. In patients with CKD G1-2 (eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), freedom from the primary outcome was similar between the PVI + LVA-ABL and PVI-alone groups (53.1% vs. 55.3%, P = 0.59). In contrast, in patients with CKD G3a-5 (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), freedom from the primary outcome was significantly higher in the PVI + LVA-ABL group than in the PVI-alone group (69.1% vs. 43.3%; P = 0.004).

Conclusion

In patients with renal dysfunction, LVA ablation after PVI reduced AF recurrence after radiofrequency catheter ablation for persistent AF.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Catheter ablation, Left atrial remodelling, Renal function, Chronic kidney disease

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

A total of 342 consecutive patients were prospectively enrolled in the SUPPRESS-AF study. Patients were initially randomized to pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) alone or PVI + low-voltage area (LVA)-ablation (ABL). One patient was excluded due to missing eGFR data. Finally, 171 patients in the PVI-alone group and 170 patients in the PVI + LVA-ABL group were analysed in this study. In patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) G1-2, there was no significant difference in freedom from the primary outcome between the PVI-alone and PVI + LVA-ABL groups. Conversely, in patients with CKD G3a-5, freedom from the primary outcome was significantly higher in the PVI + LVA-ABL group than in the PVI-alone group. LVAs, low-voltage areas; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; RFCA, radiofrequency catheter ablation; AF, atrial fibrillation; ABL, ablation; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

What’s new?

This sub-analysis of the SUPPRESS-AF trial investigated the efficacy of low-voltage area (LVA) ablation after pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) stratified by renal function.

In radiofrequency catheter ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation (AF), LVA ablation after PVI did not reduce AF recurrence in patients without renal dysfunction (estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2). In contrast, LVA ablation after PVI reduced AF recurrence in patients with renal dysfunction.

These findings suggest that while routine LVA ablation after PVI may not be recommended in patients without renal dysfunction, aggressive substrate modification by LVA ablation may be considered in those with renal dysfunction.

Introduction

Catheter ablation is an effective and rapidly advancing therapy for atrial fibrillation (AF).1 Although pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) is commonly performed as standard therapy of AF ablation,1 many patients experience AF recurrence after catheter ablation by PVI alone, especially those with persistent AF.1 Although additional ablation other than PVI is also performed to modify the AF substrate,2,3 no strategy for left atrial additional ablation other than PVI has yet been established.1

Left atrial low-voltage areas (LVAs), which reflect atrial remodelling caused by atrial cardiomyopathy,4 are also associated with poor rhythm outcomes after catheter ablation for AF.5,6 Low-voltage area ablation was developed as a patient-tailored ablation that ablated LVAs, either by encircling or cluster ablation, with the aim of eliminating LVAs.1,7,8 Although the SUPPRESS-AF trial showed that AF recurrence in patients undergoing persistent AF ablation was not statistically reduced by the routine use of LVA ablation in addition to PVI,9 there was nevertheless a greater reduction in AF recurrence in the PVI plus LVA ablation group than in the PVI-alone group in some subgroups, such as those with older age, a large left atrial diameter, and a large size of LVAs.9

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a risk factor for many cardiovascular diseases.10 Chronic kidney disease induces atrial remodelling via a number of factors, including electrolyte imbalance, increased sympathetic activity, and inflammation.11,12,13 A previous study showed that the severity of CKD is correlated with the prevalence of LVAs.14 However, the association of renal function with the efficacy of LVA ablation after PVI has not been clarified.

We have hypothesized that LVA ablation after PVI would be effective in patients with renal dysfunction. Here, we evaluated the efficacy of LVA ablation after PVI stratified by renal function.

Methods

Patients and assessment of renal function

This study was conducted as a post hoc sub-analysis of the Efficacy and Safety of Left Atrial Low-voltage Area Guided Ablation for Recurrence Prevention Compared to Pulmonary Vein Isolation Alone in Patients with Persistent Atrial Fibrillation trial (SUPPRESS-AF trial), which was designed as a multicentre, prospective, randomized, open-label trial.9,15 This sub-analysis included 342 consecutive patients with persistent AF who underwent indexed radiofrequency catheter ablation. Persistent AF was defined as AF with a sustained episode lasting ≥7 days at enrolment15 and long-standing persistent AF as AF with a continuous AF episode lasting more than 1 year.1

Patients first underwent PVI during the procedure, followed by voltage mapping. If the size of LVAs detected by voltage mapping was ≥5 cm2, patients were randomized 1:1 by an online system to a strategy of PVI alone (PVI-alone group) or LVA ablation after PVI [PVI + LVA-ablation (ABL) group].9,15 Exclusion criteria were as follows: dialysis, left atrial diameter ≥ 55 mm, history of cardiac surgery, valvular AF, age < 20 years, pregnancy, history of thromboembolism (stroke, transient ischaemic attack, or systemic embolism) within the previous 6 months, and physician assessment as ineligible for the SUPPRESS-AF trial.9,15 In this sub-analysis, patients with missing estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) data were also excluded.

In this study, patients were also stratified by renal function. Renal function was assessed most recently within 90 days prior to catheter ablation using creatinine-based eGFR.10 Based on the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2024 guideline,10 eGFR was rounded to the nearest whole number, and eGFR categories were defined as G1 (normal or high), ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2; G2 (mildly decreased), 60–89 mL/min/1.73 m2; G3a (mildly to moderately decreased), 45–59 mL/min/1.73 m2; G3b (moderately to severely decreased), 30–44 mL/min/1.73 m2; G4 (severely decreased), 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2; and G5 (renal failure), <15 mL/min/1.73 m2. Patients were also divided into two groups by CKD stage, namely CKD G1-2 (eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and CKD G3a-5 (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), on the basis that eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 is a criterion for CKD.10

This study was funded through IIS grant by Biosense Webster, Inc., part of Johnson & Johnson MedTech. Both the SUPPRESS-AF trial and this study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent for catheter ablation and enrolment in the SUPPRESS-AF trial was obtained from all patients. The SUPPRESS-AF trial was registered with UMIN-CTR (UMIN000035940), and the protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each participating hospital.

Catheter ablation procedure

As described in previous publications of the SUPPRESS-AF trial,9,15 all procedures were performed with a single 3-D mapping system (CARTO3; Biosense Webster, Inc., Diamond Bar CA, USA). Initially, ipsilateral circumferential PVI was performed using an open-irrigated linear ablation catheter with a 3.5 mm tip (Thermocool SmartTouch; Biosense Webster, Inc.). Ablation lesion quality during PVI was assessed using the ablation index (AI).16 If AF persisted after PVI, electrical cardioversion was performed before voltage mapping.

After completion of PVI, voltage mapping was performed in the left atrium with pacing from the right atrium. A multi-electrode mapping catheter (Pentaray; Biosense Webster, Inc.) or 20-pole circular catheter (Lasso Nav; Biosense Webster, Inc.) was used for voltage mapping. Low-voltage areas were defined as areas with a bipolar peak-to-peak voltage < 0.5 mV, although areas with a bipolar peak-to-peak voltage < 0.05 mV were considered as scar lesions. Low-voltage area size was measured manually in each case, and patients with a total LVA size ≥ 5 cm2 were randomized to either the PVI + LVA-ABL group or PVI-alone group. In contrast, patients with a total LVA area < 5 cm2 were excluded.

Cluster ablation of all LVAs was performed in the PVI + LVA-ABL group. However, LVAs in the left atrial posterior wall could be isolated by roof line linear ablation and floor line linear ablation to avoid oesophageal injury. The quality of the ablation lesion in LVA ablation was also assessed using AI.16 Omission of LVA ablation was allowed if LVAs were located at a region where ablation was dangerous, such as the atrial septum near Bachmann’s bundle or the His bundle and posterior wall near the oesophagus.

After LVA ablation, tachyarrhythmia inducibility was assessed by atrial burst pacing and isoproterenol infusion. If atrial tachycardia/flutter and non-PV foci were detected, these could be ablated at the discretion of the operator.

Patient follow-up

Atrial fibrillation recurrence after ablation was followed for 12 months. Routine follow-up was performed at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after catheter ablation. Twelve-lead electrocardiography was performed at each follow-up, and Holter electrocardiography was performed at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Further, 30 s rhythm checks were performed with a portable ECG (HCG 901 or HCG 801; Omron, Kyoto, Japan) twice every day between 6 and 12 months, and symptom-driven rhythm checks were done with a portable ECG at the discretion of the physician.

Primary endpoint was defined as the recurrence of atrial tachyarrhythmia without antiarrhythmic agents during the 12 months following the initial catheter ablation procedure. The post-ablation blanking period was set at 3 months. Atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence was defined as any AF or atrial tachycardia detected by electrocardiogram or AF or atrial tachycardia lasting ≥30 s detected by Holter ECG monitoring ≥3 months after the catheter ablation procedure.

Repeat ablation was performed for recurrent atrial tachyarrhythmia at the discretion of the attending physician. During repeat ablation procedures, LVA ablation was not allowed in the PVI-alone group. Conversely, repeat LVA ablation could be performed in the PVI + LVA-ABL group.

Secondary endpoints were the recurrence of atrial tachyarrhythmias after the last ablation procedure and a composite of all-cause death, symptomatic stroke, and bleeding. Each event was assessed separately during the 12-month follow-up period. Procedure-related adverse events were also assessed for 6 months after the index catheter ablation procedure. Bleeding was defined as hospitalization for bleeding and/or major bleeding according to the ISTH bleeding criteria.17

Statistical analysis

In this study, continuous data are reported as mean ± standard deviation or median (1st-3rd quartiles) and categorical data as absolute values (percentages). Significance tests were performed using the unpaired Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log-rank test were used to assess the association between outcomes and renal function. For patients with CKD G1-2 and those with CKD G3a-5, subgroup analysis of the primary endpoint was also performed using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Subgroup types were determined based on the subgroup with a significantly greater reduction in the primary endpoint in the PVI + LVA-ABL group in the main publication of the SUPPRESS-AF trial.9 All statistical analyses in this study were performed using commercial software (SPSS™; SPSS, Inc., Chicago IL, USA).

Results

Patient flow chart and patient characteristics

Figure 1 shows the patient flow chart of this study. From eight institutions, 342 consecutive patients with ≥5 cm2 LVAs were prospectively enrolled between June 2019 and September 2022. Patients were randomized 1:1 to the PVI-alone or PVI + LVA-ABL group. After excluding one patient with missing eGFR data, 171 patients in the PVI-alone group and 170 patients in the PVI + LVA-ABL group were followed for 12 months.

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart. A total of 342 consecutive patients were prospectively enrolled in the SUPPRESS-AF study. Patients were initially randomized to PVI alone or PVI + LVA-ABL. One patient was excluded due to missing eGFR data. Finally, 171 patients in the PVI-alone group and 170 patients in the PVI + LVA-ABL group were analysed. AF, atrial fibrillation; LVAs, low-voltage areas; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; ABL, ablation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Chronic kidney stage was G1 in 14 (4%) patients, G2 in 158 (46%), G3a in 122 (36%), G3b in 39 (11%), G4 in 7 (2%), and G5 in 1 (0.3%). One hundred and seventy-two (50%) patients had CKD G1-2 and 169 (50%) had CKD G3a-5. Patients with CKD G3a-5 were older and had a higher CHA2DS2-VA score as well as higher creatinine and higher N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels than patients with CKD G1-2. Additionally, patients with CKD G3a-5 had a higher prevalence of congestive heart failure and were more likely to use beta antagonists and diuretics than those with CKD G1-2. Conversely, patients with CKD G3a-5 had a lower eGFR than those with CKD G1-2.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variable | All (n = 341) | CKD G1-2 (n = 172) | CKD G3a-5 (n = 169) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years old | 74 ± 6 | 73 ± 7 | 76 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 167 (49) | 86 (50) | 81 (48) | 0.70 |

| Long-standing persistent AF, n (%) | 70 (21) | 35 (20) | 35 (21) | 0.93 |

| Duration of AF, n (%) | 4 (2–10) | 4 (2–11) | 4 (2–10) | 0.84 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24 ± 4 | 23 ± 4 | 24 ± 4 | 0.26 |

| CHA2DS2-VA score | 3.0 ± 1.3 | 2.7 ± 1.4 | 3.3 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 104 (31) | 42 (24) | 62 (37) | 0.01 |

| NYHA class | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–2) | 0.06 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 242 (71) | 117 (68) | 125 (74) | 0.23 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 77 (23) | 37 (22) | 40 (24) | 0.63 |

| Thromboembolism, n (%) | 16 (5) | 8 (5) | 8 (5) | 0.97 |

| COPD, n (%) | 17 (5) | 6 (4) | 11 (7) | 0.20 |

| Thyroid disease, n (%) | 17 (5) | 7 (4) | 10 (6) | 0.43 |

| Direct oral anticoagulant, n (%) | 328 (96) | 166 (97) | 162 (96) | 0.75 |

| Antiarrhythmic agent, n (%) | 22 (7) | 11 (6) | 11 (7) | 0.97 |

| Renin–angiotensin system inhibitor, n (%) | 135 (40) | 61 (36) | 74 (44) | 0.12 |

| Beta-blocker, n (%) | 178 (52) | 75 (44) | 103 (61) | 0.001 |

| Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | 165 (48) | 83 (48) | 82 (49) | 0.96 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 115 (34) | 43 (25) | 72 (43) | 0.001 |

| Haemoglobin, g/L | 13.6 ± 1.5 | 13.6 ± 1.3 | 13.5 ± 1.7 | 0.34 |

| NT-ProBNP, ng/L | 1092 (681–1737) | 913 (566–1261) | 1460 (897–2087) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 60 ± 16 | 73 ± 11 | 48 ± 9 | <0.001 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 57 ± 11 | 57 ± 10 | 56 ± 11 | 0.17 |

| Left atrial diameter, mm | 44 ± 5 | 44 ± 6 | 44 ± 5 | 0.66 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; AF, atrial fibrillation; NYHA, New York Heart Association; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Procedural characteristics and size of low-voltage areas

The procedural characteristics are shown in Table 2. Patients with CKD G3a-5 had a larger LVA size than those with CKD G1-2 [16 (10–25) cm2 vs. 12 (8–21) cm2; P = 0.008]. In addition, LVA size increased with increasing CKD severity (CKD G1, 9 (6–20) cm2; CKD G2, 12 (8–22) cm2; CKD G3a, 15 (10–25) cm2; CKD G3b, 16 (10–22) cm2; CKD G4–5, 29 (12–53) cm2; P = 0.03]. In patients with CKD G1-2, procedure time was longer in the PVI + LVA-ABL group than in the PVI-alone group. In patients with CKD G3a-5, atrial tachycardia ablations other than CTI were performed more frequently in the PVI + LVA-ABL group than in the PVI-alone group.

Table 2.

Procedural characteristics

| Variable | All (n = 341) | CKD G1-2 (n = 172) | P | CKD G3a-5 (n = 169) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVI-alone (n = 84) | PVI + LVA-ABL (n = 88) | PVI-alone (n = 87) | PVI + LVA-ABL (n = 82) | ||||

| Procedural time, min | 178 ± 68 | 156 ± 59 | 192 ± 73 | 0.001 | 172 ± 59 | 192 ± 73 | 0.052 |

| Deflectable sheath, n (%) | 268 (79) | 67 (80) | 68 (77) | 0.69 | 67 (77) | 66 (81) | 0.58 |

| First-pass isolation, n (%) | |||||||

| All, n (%) | 275 (81) | 72 (86) | 72 (82) | 0.49 | 65 (75) | 66 (81) | 0.37 |

| Left PV, n (%) | 300 (88) | 76 (91) | 79 (90) | 0.88 | 73 (84) | 72 (88) | 0.47 |

| Right PV, n (%) | 298 (87) | 77 (92) | 77 (88) | 0.37 | 74 (85) | 70 (85) | 0.96 |

| Total size of LVAs, cm2 | 13 (9–24) | 12 (8–24) | 12 (8–18) | 0.53 | 15 (9–25) | 16 (10–26) | 0.73 |

| Total surface area of left atrium, cm2 | 161 (134–191) | 162 (132–186) | 163 (139–195) | 0.40 | 154 (134–184) | 168 (135–199) | 0.29 |

| Total no. of mapping points of left atrium, points | 1678 (1274–2301) | 1619 (1201–2137) | 1632 (1254–2208) | 0.54 | 1808 (1393–2319) | 1749 (1389–2386) | 0.91 |

| LVA ablation, n (%) | 170 (50) | 0 (0) | 88 (100) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | 82 (100) | <0.001 |

| Completion of LVA ablation, n (%) | 133 (78) | – | 75 (85) | – | – | 58 (71) | – |

| CTI linear ablation, n (%) | 84 (25) | 18 (21) | 18 (21) | 0.88 | 23 (26) | 25 (31) | 0.56 |

| AT ablation other than CTI, n (%) | 40 (12) | 9 (11) | 15 (17) | 0.23 | 3 (3) | 13 (16) | 0.008 |

| Superior vena cava ablation, n (%) | 8 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1.00 | 4 (5) | 1 (1) | 0.37 |

| Non-PV trigger ablation, n (%) | 18 (5) | 6 (7) | 3 (3) | 0.32 | 6 (7) | 3 (4) | 0.50 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; LVA, low-voltage area; PV, pulmonary vein; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; AT, atrial tachycardia.

Atrial fibrillation recurrence and renal function

A total of 146 patients (43%) experienced the primary outcome during the 12-month follow-up period. There was no difference in the incidence of freedom from the primary outcome between patients with CKD G1-2 and CKD G3a-5 (54.2% vs. 56.0%; P = 0.64) (Figure 2A). There was also no difference in the incidence of freedom from the primary outcome between patients by CKD stage (CKD G1, 64.3%; CKD G2, 53.3%; CKD G3a, 54.9%; CKD G3b, 56.7%; CKD G4-5, 72.9%; P = 0.82) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Association between the primary outcome and renal function. (A) There was no difference in freedom from the primary outcome between patients with CKD G1-2 and those with CKD G3a-5. (B) There was no difference in freedom from the primary outcome between patients by stage of CKD. CKD, chronic kidney disease.

In patients with CKD G1-2, freedom from the primary outcome was similar between the PVI + LVA-ABL and PVI-alone groups (53.1% vs. 55.3%; P = 0.59) (Figure 3A). In contrast, in patients with CKD G3a-5, freedom from the primary outcome was significantly higher in the PVI + LVA-ABL group than in the PVI-alone group (69.1% vs. 43.3%; P = 0.004) (Figure 3B). The interaction between CKD G1-2 or CKD G3a-5 and ablation strategy on the primary outcome was significant (P = 0.02). Comparison of freedom from the primary outcome among groups stratified by CKD stage is also shown in Supplementary material online, Figure S1.

Figure 3.

Association between the primary outcome and ablation strategy by CKD G1-2 vs. CKD G3a-5. (A) In patients with CKD G1-2, there was no significant difference in freedom from the primary outcome between the PVI-alone and PVI + LVA-ABL groups. (B) In patients with CKD G3a-5, freedom from the primary outcome was significantly higher in the PVI + LVA-ABL group than in the PVI-alone group. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; CKD, chronic kidney disease; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; LVA, low-voltage area; ABL, ablation.

Similarly, in patients with CKD G1-2, there was no difference in freedom from AF recurrence after the last ablation between the PVI-alone and PVI + LVA-ABL groups (61.7% vs. 60.3%, P = 0.71) (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2A). In contrast, in patients with CKD G3a-5, freedom from AF recurrence after the last ablation was significantly higher in the PVI + LVA-ABL than in the PVI-alone group (76.1% vs. 51.8%; P = 0.007) (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2B).

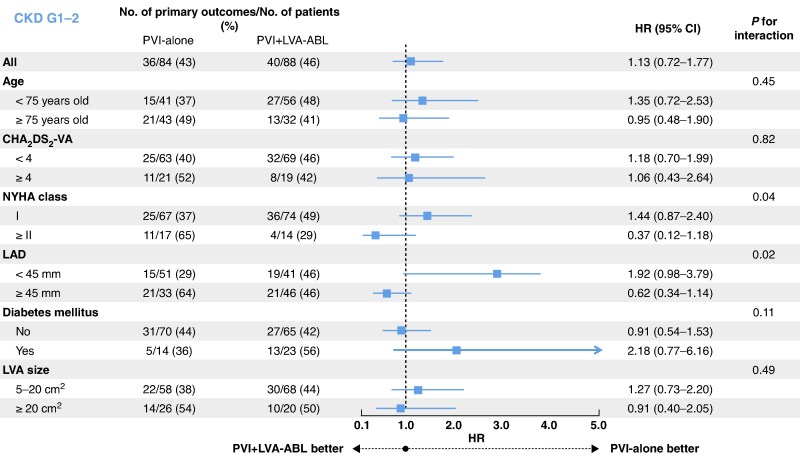

Subgroup analysis of the primary outcome

A subgroup analysis of the primary endpoint was performed in patients with CKD G1-2 and those with CKD G3a-5. In patients with CKD G1-2, there was no subgroup with a reduction in the primary endpoint in the PVI + LVA-ABL group compared to the PVI-along group (Figure 4). By contrast, in patients with CKD G3a-5, an advantage in prevention of the primary endpoint in the PVI + LVA-ABL group compared to the PVI-alone group was observed in patients aged ≥75 years old, as well as those with any of a CHA2DS2-VA score ≥ 4, New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class I, left atrial diameter < 45 mm, without diabetes mellitus, and LVA ≥ 20 cm2 (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of the primary endpoint in patients with CKD G1-2 (eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2). In patients with CKD G1-2, no subgroup in the PVI + LVA-ABL group showed a reduction in primary endpoint compared to the PVI-alone group. CKD, chronic kidney disease; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; LVA, low-voltage area; ABL, ablation; NYHA, New York Heart Association; LAD, left atrial diameter; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Figure 5.

Subgroup analysis of the primary endpoint in patients with CKD G3a-5 (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2). In patients with CKD G3a-5, prevention of the primary endpoint was greater in the PVI + LVA-ABL group compared to the PVI-alone group in patients aged ≥75 years and those with CHA2DS2-VA score ≥ 4, NYHA Class I, LAD < 45 mm, without diabetes mellitus, and with LVA ≥ 20 cm2. CKD, chronic kidney disease; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; LVA, low-voltage area; ABL, ablation; NYHA, New York Heart Association; LAD, left atrial diameter; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Safety outcomes

The incidence of the composite endpoint of all-cause death, symptomatic stroke, and bleeding was similar between patients with CKD G1-2 and those with CKD G3a-5 [10 (6%) vs. 6 (4%); P = 0.32]. Individually assessed all-cause death [3 (2%) vs. 1 (1%); P = 0.62], symptomatic stroke [6 (4%) vs. 1 (1%); P = 0.12], and bleeding [4 (2%) vs. 4 (2%); P = 1.00] were also similar between patients with CKD G1-2 and those with CKD G3a-5.

Even when stratified by CKD G1-2 and CKD G3a-5, there was no difference in the composite endpoint, or in any of its components when assessed individually (i.e. all-cause death, symptomatic stroke, and bleeding), between the PVI-alone and PVI + LVA-ABL groups (see Supplementary material online, Table S1).

The rate of procedure-related complications was similar between patients with CKD G1-2 and CKD G3a-5 [7 (4%) vs. 8 (5%); P = 0.80]. Procedure-related complications stratified by CKD G1-2 and CKD G3a-5 are shown in Table 3. In both patients with CKD G1-2 and CKD G3a-5, there was no statistically significant difference in the overall procedure-related complication rate or rates of individual complications between the PVI-alone group and the PVI + LVA-ABL group.

Table 3.

Procedure-related complications

| Variable | All (n = 341) | CKD G1-2 (n = 172) | P | CKD G3a-5 (n = 169) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVI-alone (n = 84) | PVI + LVA-ABL (n = 88) | PVI-alone (n = 87) | PVI + LVA-ABL (n = 82) | ||||

| All, n (%) | 15 (4) | 2 (2) | 5 (6) | 0.44 | 2 (2) | 6 (7) | 0.16 |

| Haematoma, n (%) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0.50 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Haemorrhage,a n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Systemic thromboembolism, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Pneumothorax, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Atrial venous fistula, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Pericarditis, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.49 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Cardiac tamponade, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.49 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Phrenic nerve paralysis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Atrioventricular block, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Sick sinus syndrome, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Pulmonary hypertension with pulmonary vein stenosis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Atrio-oesophageal fistula, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Acute gastric dilatation, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Infection, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.00 | 0 (0) | 4 (5) | 0.053 |

| Allergy, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Others, n (%) | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.00 | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0.61 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; LVA, low-voltage area.

aHaemorrhage consisted of gastrointestinal bleeding and intracranial haemorrhage.

Discussion

This study, a sub-analysis of the multicentre, prospective, randomized, open-label SUPPRESS-AF trial, was conducted in 341 patients who underwent initial radiofrequency catheter ablation for persistent AF. Our aim was to evaluate the efficacy of LVA ablation after PVI in patients stratified by renal function. During 12 months of follow-up, we found no significant difference in freedom from AF recurrence between the PVI + LVA-ABL group and PVI-alone group in patients with CKD G1-2. In contrast, freedom from AF recurrence was significantly higher in the PVI + LVA-ABL group than in the PVI-alone group in patients with CKD G3a-5. To our knowledge, this is the first clinical study to evaluate the efficacy of LVA ablation after PVI in patients stratified by renal function.

Association between the efficacy of low-voltage area ablation and renal dysfunction

Low-voltage areas are clinical surrogate markers of atrial remodelling caused by atrial cardiomyopathy,4 and impaired left atrial function, as assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, predicts the prevalence of LVAs.18 Low-voltage areas are also commonly arrhythmogenic in AF patients,19,20 and conversely, AF burden is associated with both progressive and regressive changes in LVAs.6,21,22 In this study, we found that AF recurrence was reduced by LVA ablation after PVI in patients with CKD G3a-5.

We suggest several possible explanations for this finding. First, the arrhythmogenicity of LVA may be particularly high in patients with CKD, given that arrhythmogenicity in LVA lesions may also be exacerbated by factors specific to renal dysfunction. For instance, renal dysfunction typically involves electrolyte and pH abnormalities such as hyperkalaemia and metabolic acidosis, as well as the accumulation of uremic toxins such as indoxyl sulfate and fibroblast growth factor-23, all of which promote arrhythmogenicity.23 Ablation of LVAs with high arrhythmogenicity may have an impact on reducing AF recurrence after catheter ablation.

Second, patients with renal dysfunction often demonstrate extensive LVAs, which reflect advanced atrial remodelling and are associated with an increased risk of AF recurrence following catheter ablation.24 Aggressive substrate modification by LVA ablation in these cases may therefore be effective. The severe atrial remodelling in patients with renal dysfunction is attributable not only to the renal dysfunction itself but also to the conditions underlying the renal dysfunction, such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, which are also causes of atrial remodelling.25 Indeed, our patients with CKD G3a-5 had a greater LVA size than those with CKD G1-2, and LVA size increased with increasing CKD severity. In addition, in patients with CKD G3a-5, a greater reduction in the primary endpoint was seen in the PVI + LVA-ABL group than in the PVI-alone group in patients with large LVA size.

In contrast, in patients with CKD G1-2, rhythm outcomes after catheter ablation did not differ between the PVI + LVA-ABL group and PVI-alone group. Proarrhythmic lesions and iatrogenic atrial tachycardia may occur as side effects of additional left atrial ablation other than PVI.1 The arrhythmogenicity of LVA in patients with normal renal function may not reach a level at which the efficacy of substrate modification is outweighed by its side effects.

In the subgroup analysis of primary outcome in patients with CKD G3a-5, the efficacy of LVA ablation after PVI in reducing AF recurrence was decreased in patients with heart failure symptoms ≥ NYHA class II and in those with left atrial diameter ≥ 45 mm. Patients with heart failure symptoms and those with large left atrial diameter have structural atrial remodelling, including mainly left atrial enlargement.26,27 Low-voltage area ablation, which targets electrical atrial remodelling, might therefore not have sufficient efficacy to improve rhythm outcomes.

Clinical implications of this sub-analysis

Over the past few decades, various ablation strategies beyond PVI have been investigated to improve rhythm outcomes following catheter ablation for persistent AF.28 Initially, linear ablation and/or complex fractionated electrogram ablation were commonly employed.3,28,29 However, LVA ablation has recently garnered attention because the STAR AF II trial demonstrated no significant improvement in rhythm outcomes with linear ablation and/or complex fractionated electrogram ablation.3,28 Although the primary findings of the SUPPRESS-AF trial did not reveal the efficacy of routine LVA ablation after PVI,9 this sub-analysis showed that AF recurrence after catheter ablation was reduced by LVA ablation after PVI in patients with renal dysfunction. These results suggest that aggressive substrate modification by LVA ablation may be considered. However, when pulsed-field ablation is employed, both renal dysfunction and a large number of applications have been identified as risk factors for post-procedural increases in serum creatinine.30,31,32 Therefore, the number of applications should be carefully managed. In addition, we expect that future studies will investigate whether the prevention of further CKD-induced atrial remodelling using mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors may also improve rhythm outcomes after catheter ablation.23,33

Regarding patients with CKD G1-2, freedom from AF recurrence was similar between the PVI-alone and PVI + LVA-ABL groups regardless of multiple ablation procedures. Further, no subgroup in the PVI + LVA-ABL group experienced a reduction in AF recurrence compared with the respective subgroup in the PVI-alone group. Moreover, procedure time was longer in the PVI + LVA-ABL group than in the PVI-alone group, and in the main paper of the SUPPRESS-AF trial, peri-procedural adverse events tended to occur more frequently in the PVI + LVA-ABL group than in the PVI-alone group.9 Routine LVA ablation after PVI may not be recommended in patients with normal renal function; rather, alternative strategies for patients with LVAs and normal renal function, such as strict management of pathophysiological risk factors (e.g. hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, alcohol excess, and heart failure) to prevent further atrial remodelling, may warrant exploration.34,35

Limitations

This sub-analysis of the SUPPRESS-AF trial has several limitations. First, we did not have data on the underlying disease of renal dysfunction, such as diabetic nephropathy and nephrosclerosis. Additionally, we assessed eGFR only immediately before ablation and did not evaluate changes in renal function during follow-up. Second, patients on dialysis were excluded from the SUPPRESS-AF trial, so we may not have been able to accurately assess the efficacy and the safety of LVA ablation in patients with end-stage renal failure.36 Third, because AF recurrence was not evaluated by continuous rhythm monitoring, such as by implantable cardiac monitoring or a cardiac implantable electronic device, some AF recurrence might have been missed. Fourth, 22% of patients did not undergo complete LVA ablation, so the effects of LVA ablation might not be the same in each patient. Finally, the statistical analysis in the present study might have been weakened by the small number of patients with CKD G3b-5, adverse events, and procedure-related complications. For example, in CKD G3b-5 patients, although the rate of freedom from the primary endpoint was 25.8% higher in the PVI + LVA-ABL group than in the PVI-alone group, this difference was not statistically significant.

Conclusions

In patients with renal dysfunction, LVA ablation after PVI reduced AF recurrence following catheter ablation in patients undergoing radiofrequency catheter ablation for persistent AF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the clinical engineers Takashi Sumigawa, Naoya Kurata, Yusuke Ikada, Yoshitaka Kikuchi, Atsushi Shiono, and Hiroshi Kobayashi for their dedication in protocol creation and operation of ablation-related equipment according to the protocol and the clinical research coordinators Nagisa Yoshioka, Satomi Kishimoto, Kyoko Tatsumi, and Yumi Yoshida for their excellent assistance in data collection, data management, and secretarial administration.

Appendix

The OCVC-Arrhythmia Investigators: Yasuhiro Matsuda, Masaharu Masuda, and Toshiaki Mano, Kansai Rosai Hospital, Amagasaki, Japan; Masato Okada, Nobuaki Tanaka, Koji Tanaka, and Yuko Hirao, Sakurabashi Watanabe Advanced Healthcare Hospital, Osaka, Japan; Masato Kawasaki, Tetsuya Watanabe, and Takahisa Yamada, Osaka General Medical Center, Osaka, Japan; Takashi Kanda, Hitoshi Minamiguchi, Nobuhiko Makino, and Yoshiharu Higuchi, Osaka Police Hospital, Osaka, Japan; Yasuharu Matsunaga, Yasuyuki Egami, Masami Nishino, and Jun Tanouchi, Osaka Rosai Hospital, Sakai, Japan; Taiki Sato, Hirota Kida, Akihiro Sunaga, Tomoaki Nakano, Kentaro Ozu, Yohei Sotomi, Tomoharu Dohi, Katsuki Okada, Takafumi Oka, Toshihiro Takeda, Daisaku Nakatani, Shungo Hikoso, and Yasushi Sakata, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Japan; Miwa Miyoshi, Osaka Hospital, Japan Community Healthcare Organization Osaka, Japan; Koichi Inoue and Yasushi Matsumura, National Hospital Organization Osaka National Hospital, Osaka, Japan; and Tomoko Minamisaka and Shiro Hoshida, Yao Municipal Hospital, Yao, Japan.

Contributor Information

Yasuhiro Matsuda, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Masaharu Masuda, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Toshiaki Mano, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Takuya Tsujimura, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Hiroyuki Uematsu, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Hirotaka Ooka, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Satoshi Kudo, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Mizuki Ochi, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Shin Okamoto, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Takayuki Ishihara, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Kiyonori Nanto, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Yosuke Hata, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Sho Nakao, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Masaya Kusuda, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Wataru Ariyasu, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan.

Akihiro Sunaga, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Japan.

Nobuaki Tanaka, Cardiovascular Center, Sakurabashi Watanabe Advanced Healthcare Hospital, Osaka, Japan.

Tetsuya Watanabe, Division of Cardiology, Osaka General Medical Center, Osaka, Japan; Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Yao Municipal Hospital, Yao, Japan.

Hitoshi Minamiguchi, Cardiovascular Division, Osaka Police Hospital, Osaka, Japan.

Yasuyuki Egami, Division of Cardiology, Osaka Rosai Hospital, Sakai, Japan.

Takafumi Oka, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Japan.

Tomoko Minamisaka, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Yao Municipal Hospital, Yao, Japan.

Takashi Kanda, Cardiovascular Center, Kansai Rosai Hospital, 3-1-69 Inabaso, Amagasaki 660-8511, Japan; Cardiovascular Division, Osaka Police Hospital, Osaka, Japan.

Masato Okada, Cardiovascular Center, Sakurabashi Watanabe Advanced Healthcare Hospital, Osaka, Japan.

Masato Kawasaki, Division of Cardiology, Osaka General Medical Center, Osaka, Japan.

Koji Tanaka, Cardiovascular Center, Sakurabashi Watanabe Advanced Healthcare Hospital, Osaka, Japan.

Nobuhiko Makino, Cardiovascular Division, Osaka Police Hospital, Osaka, Japan.

Hirota Kida, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Japan.

Shungo Hikoso, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Japan; Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Nara Medical University, Kashihara, Japan.

Tomoharu Dohi, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Japan.

Koichi Inoue, Cardiovascular Division, National Hospital Organization Osaka National Hospital, Osaka, Japan.

Yohei Sotomi, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Japan.

Yasushi Sakata, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Japan.

Osaka Cardiovascular Conference (OCVC)-Arrhythmia Investigators:

Yasuhiro Matsuda, Masaharu Masuda, Toshiaki Mano, Masato Okada, Nobuaki Tanaka, Koji Tanaka, Yuko Hirao, Masato Kawasaki, Tetsuya Watanabe, Takahisa Yamada, Takashi Kanda, Hitoshi Minamiguchi, Nobuhiko Makino, Yoshiharu Higuchi, Yasuharu Matsunaga, Yasuyuki Egami, Masami Nishino, Jun Tanouchi, Taiki Sato, Hirota Kida, Akihiro Sunaga, Tomoaki Nakano, Kentaro Ozu, Yohei Sotomi, Tomoharu Dohi, Katsuki Okada, Takafumi Oka, Toshihiro Takeda, Daisaku Nakatani, Shungo Hikoso, Yasushi Sakata, Miwa Miyoshi, Koichi Inoue, Yasushi Matsumura, Tomoko Minamisaka, and Shiro Hoshida

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Funding

This study was funded through IIS grant by Biosense Webster, Inc., part of Johnson & Johnson MedTech.

Data availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to for the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Tzeis S, Gerstenfeld EP, Kalman J, Saad EB, Sepehri Shamloo A, Andrade JG et al. 2024 European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2024;26:euae043.38587017 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nogami A, Kurita T, Abe H, Ando K, Ishikawa T, Imai K et al. JCS/JHRS 2019 guideline on non-pharmacotherapy of cardiac arrhythmias. Circ J 2021;85:1104–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verma A, Jiang CY, Betts TR, Chen J, Deisenhofer I, Mantovan R et al. Approaches to catheter ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1812–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takahashi Y, Yamaguchi T, Otsubo T, Nakashima K, Shinzato K, Osako R et al. Histological validation of atrial structural remodelling in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2023;44:3339–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Masuda M, Matsuda Y, Uematsu H, Sugino A, Ooka H, Kudo S et al. Prognostic impact of atrial cardiomyopathy: long-term follow-up of patients with and without low-voltage areas following atrial fibrillation ablation. Heart Rhythm 2024;21:378–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsuda Y, Masuda M, Asai M, Iida O, Okamoto S, Ishihara T et al. A new clinical risk score for predicting the prevalence of low-voltage areas in patients undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2020;31:3150–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rolf S, Kircher S, Arya A, Eitel C, Sommer P, Richter S et al. Tailored atrial substrate modification based on low-voltage areas in catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014;7:825–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Masuda M, Asai M, Iida O, Okamoto S, Ishihara T, Nanto K et al. Additional low-voltage-area ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: results of the randomized controlled VOLCANO trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e015927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Masuda M, Sunaga A, Tanaka N, Watanabe T, Minamiguchi H, Egami Y et al. Low-voltage-area ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. Nat Med 2025;31:1661–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group . KDIGO 2024 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2024;105:S117–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumar S, Lim E, Covic A, Verhamme P, Gale CP, Camm AJ et al. Anticoagulation in concomitant chronic kidney disease and atrial fibrillation: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:2204–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Selejan SR, Linz D, Mauz M, Hohl M, Huynh AKD, Speer T et al. Renal denervation reduces atrial remodeling in hypertensive rats with metabolic syndrome. Basic Res Cardiol 2022;117:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Song J, Navarro-Garcia JA, Wu J, Saljic A, Abu-Taha I, Li L et al. Chronic kidney disease promotes atrial fibrillation via inflammasome pathway activation. J Clin Invest 2023;133:e167517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matsuda Y, Masuda M, Asai M, Iida O, Okamoto S, Ishihara T et al. Impact of renal dysfunction on left atrial low-voltage areas in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ J 2019;83:985–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sunaga A, Masuda M, Inoue K, Tanaka N, Watanabe T, Furukawa Y et al. The efficacy and safety of left atrial low-voltage area guided ablation for recurrence prevention compared to pulmonary vein isolation alone in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation trial: design and rationale. Clin Cardiol 2021;44:1249–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hussein A, Das M, Riva S, Morgan M, Ronayne C, Sahni A et al. Use of ablation index-guided ablation results in high rates of durable pulmonary vein isolation and freedom from arrhythmia in persistent atrial fibrillation patients: the PRAISE study results. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2018;11:e006576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schulman S, Kearon C; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost 2005;3:692–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Löbe S, Stellmach P, Darma A, Hilbert S, Paetsch I, Jahnke C et al. Left atrial total emptying fraction measured by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging predicts low-voltage areas detected during electroanatomical mapping. Europace 2023;25:euad307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kawai S, Mukai Y, Inoue S, Yakabe D, Nagaoka K, Sakamoto K et al. Non-pulmonary vein triggers of atrial fibrillation are likely to arise from low-voltage areas in the left atrium. Sci Rep 2019;9:12271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kurata N, Masuda M, Kanda T, Asai M, Iida O, Okamoto S et al. Slow whole left atrial conduction velocity after pulmonary vein isolation predicts atrial fibrillation recurrence. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2020;31:1942–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kosiuk J, Dinov B, Kornej J, Acou WJ, Schönbauer R, Fiedler L et al. Prospective, multicenter validation of a clinical risk score for left atrial arrhythmogenic substrate based on voltage analysis: DR-FLASH score. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:2207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marcon L, Bergonti M, Spera F, Saenen J, Huybrechts W, Miljoen H et al. Dynamic changes of left atrial substrate over time following pulmonary vein isolation: the Progress-AF study. Europace 2023;25:euad299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sinha F, Schweda F, Maier LS, Wagner S. Impact of impaired kidney function on arrhythmia-promoting cardiac ion channel regulation. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:14198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Starek Z, Di Cori A, Betts TR, Clerici G, Gras D, Lyan E et al. Baseline left atrial low-voltage area predicts recurrence after pulmonary vein isolation: WAVE-MAP AF results. Europace 2023;25:euad194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ono K, Iwasaki YK, Akao M, Ikeda T, Ishii K, Inden Y et al. JCS/JHRS 2020 guideline on pharmacotherapy of cardiac arrhythmias. Circ J 2022;86:1790–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wozakowska-Kapłon B. Changes in left atrial size in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: a prospective echocardiographic study with a 5-year follow-up period. Int J Cardiol 2005;101:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Waggoner AD, Adyanthaya AV, Quinones MA, Alexander JK. Left atrial enlargement. Echocardiographic assessment of electrocardiographic criteria. Circulation 1976;54:553–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boersma L, Andrade JG, Betts T, Duytschaever M, Pürerfellner H, Santoro F et al. Progress in atrial fibrillation ablation during 25 years of Europace journal. Europace 2023;25:euad244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Inoue K, Hikoso S, Masuda M, Furukawa Y, Hirata A, Egami Y et al. Pulmonary vein isolation alone vs. more extensive ablation with defragmentation and linear ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation: the EARNEST-PVI trial. Europace 2021;23:565–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Popa MA, Venier S, Menè R, Della Rocca DG, Sacher F, Derval N et al. Characterization and clinical significance of hemolysis after pulsed field ablation for atrial fibrillation: results of a multicenter analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2024;17:e012732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mohanty S, Casella M, Compagnucci P, Torlapati PG, Della Rocca DG, La Fazia VM et al. Acute kidney injury resulting from hemoglobinuria after pulsed-field ablation in atrial fibrillation: is it preventable? JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2024;10:709–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Venier S, Vaxelaire N, Jacon P, Carabelli A, Desbiolles A, Garban F et al. Severe acute kidney injury related to haemolysis after pulsed field ablation for atrial fibrillation. Europace 2023;26:euad371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Filippatos G, Bakris GL, Pitt B, Agarwal R, Rossing P, Ruilope LM et al. Finerenone reduces new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;78:142–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Van Gelder IC, Rienstra M, Bunting KV, Casado-Arroyo R, Caso V, Crijns HJGM et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2024;45:3314–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rienstra M, Tzeis S, Bunting KV, Caso V, Crijns HJGM, De Potter TJR et al. Spotlight on the 2024 ESC/EACTS management of atrial fibrillation guidelines: 10 novel key aspects. Europace 2024;26:euae298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yamamoto T, Miyazaki S, Tanaka Y, Kono T, Nakata T, Mizukami A et al. Peri-procedural anticoagulation in patients with end-stage kidney disease undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation: results from the multicentre end-stage kidney disease-atrial fibrillation ablation registry. Europace 2023;25:1400–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to for the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.