Abstract

Introduction

The journey to axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) diagnosis is often prolonged, and delayed diagnosis has been associated with poorer outcomes and increased healthcare costs. This study aimed to characterize the patient diagnostic journey in axSpA and associated healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and costs in the US.

Methods

This observational, retrospective US MarketScan® study utilized insurance claims data from the Commercial/Medicare Supplemental (January 2008–March 2023) and Medicaid (January 2008–December 2022) databases to assess the time to diagnosis in adult patients with back pain onset prior to a new axSpA diagnosis. This study evaluated the time to axSpA diagnosis from the earliest back pain diagnosis, and the diagnostic journey through the number of consultations with healthcare professionals (HCPs) for back pain, diagnostic tests, and imaging procedures. Back pain-related HCRU and costs were assessed, as well as pharmacy claims during this period.

Results

Of 97,469 patients included, 29.0% experienced time to diagnosis of ≥ 6 years, with a mean (standard deviation) of 4.5 (2.8) years to diagnosis. Prior to axSpA diagnosis, patients saw an average of 4.57 HCPs annually and had 20.7 back pain-related visits overall for back pain-related causes. Between the earliest back pain diagnosis and axSpA diagnosis, 55.9% of patients experienced > 10 back pain consultations, and patients underwent a range of diagnostic tests and imaging procedures. The median sum of non-capitated back pain-related costs up to axSpA diagnosis was $883.19 per patient per year, plus $1127.57 per patient per year for pharmacy prescriptions.

Conclusions

This study shows that diagnostic delay is a challenge for patients with axSpA in the US, despite numerous back pain consultations, specialist visits, and diagnostic tests. These findings highlight the urgent need for strategies to enhance recognition of axSpA and improve the patient diagnostic journey.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-025-00791-5.

Keywords: Axial spondyloarthritis, Time to diagnosis, Patient journey, Access to treatment, Burden, Back pain, Diagnostic delay

Plain Language Summary

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a disease that affects the joints of the spine and hips. People with axSpA can experience back pain, stiffness, tiredness, and lower quality of life. It often takes several years before people are diagnosed with axSpA. During this delay, damage caused by the disease can worsen or become permanent without timely treatment. In this study, we used information from the records that track the medical services and costs covered by insurance for people with axSpA in the US. These records were studied from the time people first had back pain to when they were diagnosed with axSpA. We looked at how long it generally takes for people to be diagnosed with axSpA. We also looked at what people experienced during this time, like the number of times they visited a doctor, the medical tests they had, and their medical costs. Among the 97,469 people whose records were included, the average time to axSpA diagnosis was four and a half years. Over half of the people visited a doctor more than ten times for their back pain before they were diagnosed with axSpA. People had several different medical tests during this time. They were given a range of different medications for their pain and other symptoms, costing over $1000 on average for each person every year. Our findings indicate that delayed diagnosis is a significant challenge for individuals with axSpA in the US, highlighting areas where the journey to axSpA diagnosis can be improved.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-025-00791-5.

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Understanding the factors contributing to delays in diagnosing axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is crucial to improving diagnostic pathways and patient outcomes, and to identifying targets for the improvement of the overall patient diagnostic journey. |

| In this study, US Merative™ MarketScan® insurance claims data were used to evaluate the time to diagnosis experienced by a large sample size of 97,469 patients with axSpA in the US, and to characterize the patient diagnostic journey and associated healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and costs. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| This study corroborated that diagnostic delay remains a challenge for patients living with axSpA in the US, with significant delays to diagnosis despite numerous back pain consultations, diagnostic tests, and imaging procedures; associated HCRU and costs were high. |

| These findings highlight the urgent need for the development of strategies to enhance recognition of axSpA and improve the patient diagnostic journey, to expedite diagnosis, reduce disease burden, and optimize HCRU. |

Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease that mainly impacts the sacroiliac joints and spine. AxSpA is categorized as radiographic (r-)axSpA or non-radiographic (nr-)axSpA, depending on the presence of observable, definitive signs of radiographic damage to the sacroiliac joints and spine [1].

AxSpA affects up to 1.4% of the adult population in the US [2], and is characterized by the presence of chronic back pain, spinal stiffness, fatigue, enthesitis, and other peripheral and extra-musculoskeletal manifestations. Patients commonly experience back pain with onset before 45 years of age [3]. Features of this back pain include insidious onset, improvement with exercise, occurrence at night with improvement upon waking, and no improvement with rest [2, 4]. Symptoms such as pain and fatigue lead to patients experiencing poor quality of life [5]. This, alongside the substantial costs associated with the diagnosis and long-term treatment and management of this chronic condition, places a considerable burden on patients, caregivers, and the healthcare system, which is similar for patients with nr- and r-axSpA [6].

Delayed diagnosis remains a significant challenge faced by patients with axSpA, with the mean global time to diagnosis estimated to be 6.7 years, and time to diagnosis in the US reported to be as high as 13.0 years [7–9]. A recent study of 228 patients with axSpA in the US reported the mean time to diagnosis to be 8.8 years, with a notably longer delay observed in women compared with men, and over half of the surveyed patients being misdiagnosed before receiving an axSpA diagnosis [10]. Most studies evaluating delays in axSpA diagnosis have used cross-sectional patient surveys, qualitative interviews, or chart reviews, which are limited by patient recall bias, lack of generalizability, and selection bias introduced by online recruitment [10–12].

Early diagnosis and access to treatment are key to preventing irreversible structural damage and loss of spinal mobility over time; some studies have shown early initiation of treatments such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors to be protective against radiographic progression [13–15]. There is an unmet need to improve the patient diagnostic journey by identifying and addressing the factors associated with delayed diagnosis in axSpA [16–18].

Characterizing the patient journey and understanding the factors involved in time to diagnosis may facilitate the development of referral strategies that could ultimately improve the axSpA diagnostic journey for both patients and healthcare professionals (HCPs). This observational, retrospective study aimed to describe the pre-diagnostic patient journey in axSpA and evaluate the healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and cost burdens using US Merative™ MarketScan® insurance claims data.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This was an observational, retrospective study based on secondary data from the three US Merative™ MarketScan® insurance claims databases: Commercial (CCAE), Medicare Supplemental (MDCR), and Medicaid (MDCD). The US Merative™ MarketScan® insurance claims databases feature more than 37 billion healthcare billing records, including over 264 million de-identified patient data across the US, used for reimbursement purposes [19]. The CCAE and MDCR include US patients enrolled in commercial insurance plans, including employer-paid Medicare supplemental plans and dependent plans, while the MDCD includes US patients enrolled under Medicaid, which provides government-subsidized health insurance for low-income individuals and families. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies, performed by any of the authors, with human participants or animals. As the study analyzed a retrospective anonymized dataset, no ethical review and no informed consent from patients was needed. However, the study protocol was reviewed by a scientific steering committee and the data owner. The work on the dataset conformed to all social security data protection requirements.

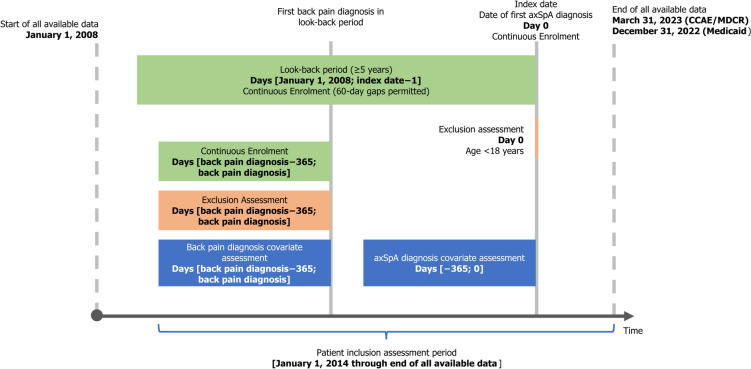

The study aimed to describe the diagnostic journey of patients with axSpA, from the day of their earliest recorded back pain diagnosis. The study design is presented in Fig. 1. The study used data from January 2008 through to the end of data availability (CCAE/MDCR: up to March 2023; MDCD: up to December 2022).

Fig. 1.

Study design. axSpA axial spondyloarthritis, CCAE commercial, MDCR Medicare

Patients over 18 years of age on the index date (date of the first new axSpA diagnosis code) were included in this study if they had at least one new rheumatologist-given diagnosis code for axSpA, one new inpatient axSpA diagnosis code by any HCP, or at least two outpatient axSpA diagnosis codes by any HCP on different service dates from January 2014 through to the end of data availability. Patients were required to have at least 5 years of continuous dual medical and pharmacy enrolment prior to and on the index date, hereafter referred to as the “look-back period”, with 60-day gaps permitted. No patients with a diagnosis of axSpA in their medical history, prior to index diagnosis, were included.

This study reports on patients with an initial diagnosis code for back pain in the look-back period, with continuous medical and pharmacy enrolment (60-day gaps permitted), and no rheumatology visits recorded in the 365 days prior to and on the initial date of back pain diagnosis. Patients with a diagnosis of back pain during the look-back period who did not meet the other inclusion criteria, and those without a diagnosis code for back pain in the look-back period, were excluded. Various etiologies and locations of back pain were included to cover a comprehensive range of reasons for back pain, as these patients are often misdiagnosed. Evidence of back pain diagnoses in the look-back period was based on a pre-specified list of International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 codes (Supplementary Table S1), which was derived by compiling diagnostic codes used in published studies [7, 20], and from public repositories of ICD-9 and ICD-10 code data; the final selection was then determined based on review by the authors (MD and MM).

The medical service claims detail information for inpatient and outpatient healthcare encounters (in this study, a pre-specified list of healthcare providers relevant to the diagnosis and treatment of axSpA were focused on; full list provided in the Supplementary Methods), including date and place of service, provider type, and plan- and patient-paid amounts. ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes were used to identify diagnoses and facility procedures. Common Procedural Terminology (CPT©) codes were used for physician procedure claims. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes were used for drugs administered by healthcare providers. Pharmacy claims include information on medications dispensed to patients, including National Drug Code (NDC), dispensing date, quantity, and plan- and patient-paid amounts.

Patient characteristics were assessed at two different time points: in the year before and on the axSpA index date, and in the year before and on the first recorded back pain diagnosis.

Outcomes

The mean (standard deviation [SD]) and median (interquartile range [Q1, Q3]) time to diagnosis were calculated in years, stratified by patient sex. For patients with a rheumatology visit prior to their axSpA diagnosis, duration of primary (earliest back pain diagnosis to the first rheumatology visit) and secondary (first rheumatology visit to axSpA diagnosis) delay were calculated. The proportions of patients experiencing different durations of time to diagnosis were determined (< 6 months, 6 months–2 years, 2–4 years, 4–6 years, and ≥ 6 years), stratified by patient sex.

To characterize the patient journey, the average number of outpatient visits to different HCPs was determined both for all-cause and back pain-related claims. The percentages of patients experiencing different numbers of consultations with HCPs for back pain recorded on different days from date of first back pain diagnosis to date of axSpA diagnosis (1–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, and > 20 consultations) were calculated, as well as the most commonly experienced back pain diagnostic codes. The percentage of patients undergoing different diagnostic tests and imaging procedures was computed, along with the mean (SD) time, in years, from the earliest back pain diagnosis to the first occurrence of these tests and procedures. These tests included human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class 1 antigen typing (not specifically HLA-B27), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) tests, C-reactive protein (CRP) tests, radiographic imaging (X-rays), computed tomography (CT) scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs). The types of these diagnostic tests extracted are reported in Supplementary Table S2. While diagnostic tests and imaging procedures for any cause were reported, the imaging procedures reported were selected for their relevance to back pain diagnosis. A breakdown of the physician type diagnosing axSpA was also obtained.

To assess HCRU and the costs associated with axSpA diagnosis, the median (Q1, Q3) number of back pain-related inpatient, outpatient, and emergency claims, the median (Q1, Q3) sum of costs of medical services and pharmacy prescriptions, and the percentage of patients receiving different treatments were calculated per patient per year for patients on non-capitated health insurance plans.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4. Patient characteristics and comorbidities were assessed within 365 days prior to and on the index date, and within the 365 days prior to and on the first back pain diagnosis date. Descriptive analyses were performed separately, stratified by patient sex, to assess time to diagnosis.

Results were only highlighted for strata with at least 50 patients. The number of observations, mean (SD), and median (Q1, Q3) were calculated for continuous variables. For categorical variables, frequency counts (n) and percentages were calculated. For all variables, missing values were reported with frequency counts (n) and percentages, and the summary statistic was computed for the total number of patients. The number of specialty outpatient visits was presented per patient years with 95% confidence intervals (CI). HCRU and costs were reported per patient per year. Costs were reported only for patients on non-capitated plans and inflation-adjusted to the year 2023 based on the Consumer Price Index Urban (CPI-U) medical care component from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Sensitivity Analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted using different minimum requirements (2 and 8 years) for continuous coverage in the look-back period to evaluate any selection bias that may have been introduced due to the requirement of 5 years of continuous medical and pharmacy coverage.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 182,248 patients met the study inclusion criteria; of these, 97,469 patients had an initial back pain diagnosis recorded prior to axSpA diagnosis and were the focus of this study (Supplementary Figure S1).

Patient demographics and characteristics are described in Table 1. The mean (SD) age was 48.8 (14.9) years at the earliest back pain diagnosis and 53.2 (14.9) years at axSpA diagnosis; 63.7% were women and most were covered by a commercial health insurance plan. The mean (SD) length of look-back time was 3083.5 (810.6) days, or 8.4 (2.2) years. 73.2% of patients presented with at least one comorbidity, while 50.3% of patients presented with multiple comorbidities, excluding extramusculoskeletal axSpA manifestations; 5.6% of patients had fibromyalgia, while 2.1% had osteoporosis at initial back pain diagnosis.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and characteristics

| Back pain prior to axSpA diagnosis (N = 97,469) | ||

|---|---|---|

| At initial back pain diagnosisa | At axSpA diagnosis | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 48.8 (14.9) | 53.2 (14.9) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Women | – | 62,127 (63.7) |

| Men | – | 35,342 (36.3) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Missing | – | 89,871 (92.2) |

| White | – | 5061 (5.2) |

| Black | – | 2267 (2.3) |

| Hispanic | – | 116 (0.1) |

| Other | – | 154 (0.2) |

| Region, n (%) | ||

| Missing | – | 8370 (8.6) |

| Northeast | – | 12,741 (13.1) |

| North Central | – | 23,419 (24.0) |

| South | – | 41,146 (42.2) |

| West | – | 11,665 (12.0) |

| Unknown | – | 128 (0.1) |

| Length of look-back, years, mean (SD) | – | 8.4 (2.2) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 29,267 (30.0) | 40,447 (41.5) |

| Fatigue | 13,647 (14.0) | 17,094 (17.5) |

| Anxiety | 12,321 (12.6) | 22,752 (23.3) |

| Depression | 12,189 (12.5) | 18,949 (19.4) |

| Atherosclerosis | 6083 (6.2) | 9462 (9.7) |

| Malignancies | 5944 (6.1) | 8329 (8.5) |

| Fibromyalgia | 5481 (5.6) | 6998 (7.2) |

| Osteoporosis | 2026 (2.1) | 3808 (3.9) |

| axSpA extramusculoskeletal manifestations, n (%) | ||

| Enthesitis/tendinitis | 7527 (7.7) | 6945 (7.1) |

| Psoriasis | 1001 (1.0) | 1622 (1.7) |

| Dactylitis | 660 (0.7) | 970 (1.0) |

| Crohn’s disease | 537 (0.6) | 719 (0.7) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 532 (0.5) | 804 (0.8) |

| Uveitis | 384 (0.4) | 664 (0.7) |

| Psoriatic arthritis (peripheral arthritis) | 174 (0.2) | 746 (0.8) |

| Insurance type, n (%) | ||

| Commercial | – | 73,286 (75.2) |

| Medicare | – | 15,813 (16.2) |

| Medicaid | – | 8370 (8.6) |

axSpA axial spondyloarthritis, N overall patient number, n number of patients in each characteristic category specified, SD standard deviation

aInitial back pain diagnosis is defined as the time of earliest observable back pain diagnosis prior to axSpA diagnosis

Time to Diagnosis

The mean (SD) time to diagnosis was 4.5 (2.8) years, and the median (Q1, Q3) was 4.4 (2.4, 6.3) years. Women experienced a slightly longer time to diagnosis (mean [SD]: 4.6 [2.8] years) than men (4.3 [2.8] years), which was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Among the 9824 (10.1%) patients who consulted a rheumatologist between initial back pain diagnosis and axSpA diagnosis, median (Q1, Q3) primary delay was 2.6 (1.1, 4.6) years, and secondary delay was 1.7 (0.2, 3.7) years. Of these patients who consulted a rheumatologist for their back pain, 13.7% received a diagnosis on the date of the first rheumatology evaluation.

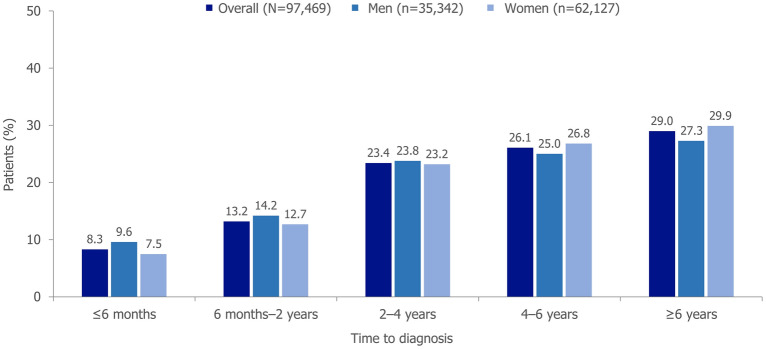

The proportions of patients stratified by sex, experiencing different durations of time to diagnosis are presented in Fig. 2; 29.0% had a total time to diagnosis ≥ 6 years.

Fig. 2.

Time to diagnosis for patients with axSpA, stratified by sex. Time to diagnosis is the time from the earliest back pain diagnosis to axSpA diagnosis. For the time to diagnosis brackets from 6 months onwards, the lower bound is inclusive, while the upper bound is exclusive. axSpA axial spondyloarthritis

Patient Journey from the Earliest Back Pain Diagnosis to First Diagnosis of axSpA

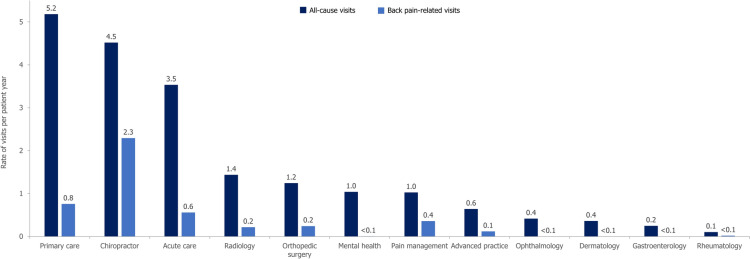

Patients saw a mean (95% CI) of 4.57 (4.56–4.57) HCPs per year in the outpatient setting for back pain-related causes or claims before axSpA diagnosis. Overall, patients had a mean (SD) of 20.7 (25.2) HCPs back pain-related visits from the earliest back pain diagnosis to axSpA diagnosis. The rates of all-cause and back pain-related specialty outpatient visits per patient year are presented in Fig. 3. 64.9% of patients had at least one back pain-related outpatient visit with their primary care provider, 64.7% with a chiropractor, 31.7% with an orthopedic surgeon, and 26.7% with a pain management specialist throughout their diagnostic journey; 52.8% had a history of attending emergency services for back pain.

Fig. 3.

Rate of all-cause and back pain-related specialty visits per patient year. N = 97,469. axSpA diagnostic journey is defined as the time from the earliest back pain diagnosis to axSpA diagnosis

The number of consultations with HCPs on separate days for back pain from the earliest back pain diagnosis to axSpA diagnosis is shown in Table 2; 55.9% of patients had > 10 back pain consultations. The most commonly observed earliest back pain code type (41.3%) was that of low back pain/lumbago, while the most commonly observed latest back pain code type (6 months prior to or on index date) was that of sacroiliitis (61.2%).

Table 2.

Distribution of patients experiencing a number of consultations with healthcare professionals for back pain, recorded on separate days, from the earliest back pain diagnosis to axSpA diagnosis

| Number of back pain consultations recorded on separate days | Patients (n [%]) |

|---|---|

| 1–5 | 26,611 (27.3) |

| 6–10 | 16,411 (16.8) |

| 11–15 | 11,804 (12.1) |

| 16–20 | 8867 (9.1) |

| > 20 | 33,776 (34.7) |

axSpA axial spondyloarthritis, n number of patients

Patients had a range of diagnostic tests and imaging procedures through their diagnostic journey, as shown in Table 3, along with the time from initial back pain diagnosis to the first occurrence of each test or procedure. The majority of patients (79.3%) had X-rays and around half had MRIs. 22.1% had a CRP test performed, while only 5.2% of patients included in this analysis had an HLA typing test. The first occurrences of HLA typing and CRP tests were observed at a mean (SD) of 3.4 (2.7) and 2.8 (2.4) years after initial back pain diagnosis, respectively, with the first X-rays and MRIs occurring at a mean (SD) of 1.4 (2.0) and 2.0 (2.3) years after initial back pain diagnosis, respectively.

Table 3.

Number and percentage of diagnostic tests and imaging procedures per patient and mean time to first instance of each testing procedure

| Patients undergoing diagnostic test or imaging procedure (n [%]) | Time to first testing procedure (years; mean [SD]) | |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic tests | ||

| HLA typing | 5042 (5.2) | 3.4 (2.7) |

| ESR test | 29,659 (30.4) | 2.4 (2.2) |

| CRP test | 21,589 (22.1) | 2.8 (2.4) |

| Imaging procedures | ||

| X-ray | 77,291 (79.3) | 1.4 (2.0) |

| CT | 16,663 (17.1) | 2.3 (2.4) |

| MRI | 49,092 (50.4) | 2.0 (2.3) |

CRP C-reactive protein, CT computed tomography, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, HLA human leukocyte antigen, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, n number of patients, SD standard deviation

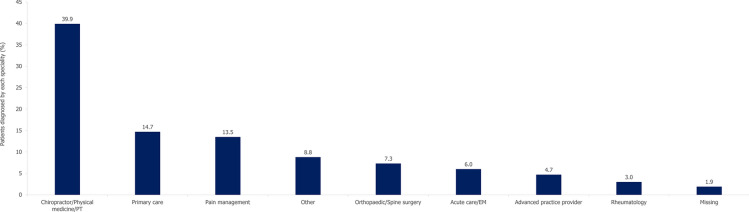

The diagnosing physician specialties are depicted in Fig. 4, with the most patients (39.9%) being diagnosed in the chiropractor/physical medicine/physical therapy setting. Primary care and pain management physicians diagnosed 14.7% and 13.5%, respectively, while only 3.0% of the cohort were diagnosed by a rheumatologist. Among the total population, 95.4% received a second axSpA diagnosis code after their initial diagnosis; of these patients, only 0.6% received this second diagnosis code in the rheumatology setting. Of the patients not diagnosed by a rheumatologist, with at least 365 days of follow-up after their first axSpA diagnosis code, 3151 (3.2%) patients had a subsequent rheumatology visit in the first year after diagnosis.

Fig. 4.

Diagnosing physician specialty. N = 97,469. EM emergency medicine, PT physical therapy

Burden of the Diagnostic Journey: HCRU and Costs

Patients had a median (Q1, Q3) of 3.7 (1.6, 8.2) back pain-related outpatient claims per patient per year between earliest back pain diagnosis and axSpA diagnosis; 7.6% of patients were hospitalized at least once for back pain during this time interval while 22.9% visited emergency departments at least once for back pain (Table 4). During the study period, 66.1% of patients filled at least one prescription for NSAIDs. More than 2/3 of patients (69.1%) filled at least one prescription for opioids and 59.9% of patients filled at least one prescription for steroids. Antidepressants and anxiolytics were also commonly used, with 49.6% of patients receiving at least one prescription for these treatments. The median (Q1, Q3) sum of non-capitated back pain-related costs (outpatient visits, hospitalizations, ED visits) was $883.19 (331.01, 2537.48) per patient per year, plus $1127.57 (268.01, 3775.66) for pharmacy prescriptions.

Table 4.

Back pain-related healthcare resource utilization per patient per year

| Patients with ≥ 1 claim, n (%) | Occurrence per patient per year, mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Back pain-related HCRU | ||

| Hospitalizations | 7430 (7.6) | 0.1 (4.6) |

| Outpatient visits | 97,089 (99.6) | 10.5 (35.5) |

| Emergency department visits | 22,325 (22.9) | 0.5 (8.8) |

| All-cause pharmacy claims | ||

| NSAID claims | 64,385 (66.1) | 1.8 (10.4) |

| Opioid claims | 67,374 (69.1) | 2.8 (9.1) |

| Steroid claims | 58,425 (59.9) | 1.0 (7.6) |

| csDMARD claims | 6362 (6.5) | 0.2 (1.0) |

| Biologic claims | 1451 (1.5) | 0.1 (0.6) |

| Antidepressant and/or anxiolytic claims | 48,359 (49.6) | 2.5 (5.0) |

csDMARD conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, HCRU healthcare resource utilization, n number of patients, NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, SD standard deviation

Sensitivity Analysis

A sensitivity analysis comparing the requirements of 2 years of continuous medical and pharmacy coverage against 8 years was conducted to assess the impact of the 5-year minimum look-back period implemented in this study on patient selection. In terms of patient characteristics, there were no significant differences between the main group of patients with 5 years of continuous data and the two cohorts used for the sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Table S3). Given these similar distributions in patient characteristics, the analysis of the main cohort is less likely to include a selection bias on this basis.

Discussion

The US Merative™ MarketScan® insurance claims database has been extensively used in previous real-world studies in patients with rheumatologic diseases [21–23], including axSpA [24–27], to explore various research questions, for example involving treatment patterns, HCRU utilization, and comorbidities. This observational, retrospective study using US Merative™ MarketScan® insurance claims data of more than 97,000 individuals with axSpA and an initial back pain diagnosis over a 15-year period provides insights into the significant challenge of delayed diagnosis of axSpA in the US, while also corroborating established literature.

Diagnostic delay remains a key challenge for patients with axSpA in the US. In this study, the mean (SD) time to diagnosis was 4.5 (2.8) years and 29.0% of patients had a total time to diagnosis ≥ 6 years. Patients underwent numerous consultations for back pain throughout the pre-diagnostic patient journey; 55.9% of patients had more than ten back pain consultations in total, throughout their diagnostic journey. On average, patients in this study saw 4.6 HCPs per year and 20.7 HCPs overall for back pain-related outpatient visits, which is similar to the global average of three HCPs per year as reported in a survey by the International Map of Axial Spondyloarthritis (IMAS) initiative [10]. These findings corroborate the results in existing literature that patients with axSpA in the US tend to see several HCPs for back pain prior to diagnosis [12]. This study also demonstrated that the burden of diagnostic delay is substantial and that associated costs are high. The results presented here are unlikely to have been influenced by selection bias due to the 5-year minimum look-back period, as demonstrated by the sensitivity analysis results. Despite the change in patient numbers, there were no significant differences between the main cohort with a minimum of 5 years of continuous data and the two cohorts in the sensitivity analysis.

The average patient-reported time to diagnosis in a recent survey of patients with axSpA in the US was 8.8 years [10], and an IMAS survey reported a global mean delay of 7.4 years (9.0 years in North America) [28], compared with 4.5 years reported in this study. The average time to diagnosis observed in this study was likely shorter than that reported in the patient surveys, as claims data capture the time from initial back pain diagnosis to axSpA diagnosis to compose the patient diagnostic journey, while surveys reflect time from symptom onset and may be prone to patient recall bias. A previous study using MarketScan® data reported that median time from back pain diagnosis to rheumatology referral was less than 1 year [7], which is significantly shorter than the durations reported in the current study. However, the inclusion and exclusion criteria and back pain codes applied to that study were not comparable to the current study, limiting the comparisons that may be drawn.

A large number of patients were diagnosed by HCPs other than rheumatologists in this study. Only 10.1% of patients consulted a rheumatologist during their diagnostic journey; among these patients, average secondary delay, defined as the time from the first rheumatology visit to axSpA diagnosis, was 1.7 years. In contrast, previous global studies have reported rheumatologists to be the most common diagnosing physicians [10, 29]. Patients with back pain in the US commonly receive care from providers other than rheumatologists; these providers may be unfamiliar with differentiating axSpA from other common causes of back pain. For this reason, misdiagnosis of axSpA may be common in a substantial proportion of patients in the US. Primary care providers are often considered to be the “gatekeepers” for patients with back pain and can play a crucial role in increasing referrals to rheumatologists for suspected axSpA. These findings highlight the need for improved referral pathways to rheumatology, clearer diagnostic pipelines, and improved awareness and recognition of axSpA within the field [17]. Awareness of the signs and symptoms of axSpA is not only required among primary care providers, but also with physiotherapists, chiropractors, and orthopedic surgeons who also see these patients.

The disease burden of axSpA is worsened by the delayed diagnosis of the disease, necessitating multiple specialist visits, diagnostic tests and procedures, and pharmacy prescriptions. Over two-thirds of patients studied here were prescribed opioids, over half were prescribed steroids, and close to half were prescribed antidepressants and anxiolytics between the time from the earliest back pain diagnosis to axSpA diagnosis. The use of steroids and opioids is not recommended in axSpA [30], and these data therefore suggest that patients may have experienced suboptimal treatment and management of their symptoms due to the lack of a prompt axSpA diagnosis. It should be noted, however, that these data are based on all-cause (not back pain-related) pharmacy claims.

With regards to costs and HCRU, the majority of existing literature focuses on employment and work disability experienced by patients with axSpA. While delayed diagnosis of axSpA generally results in increased HCRU, there is limited data available to explore this phenomenon in the US [31, 32]. In the absence of a control group, the current study is unable to draw conclusions regarding the association of longer time to diagnosis with higher costs. Earlier diagnosis might be more cost-effective, but it may be offset by additional higher post-diagnosis costs due to costly treatment regimens.

Previous studies investigating the factors associated with time to diagnosis have reported that delays may be influenced by a lack of clear diagnostic criteria and difficulty distinguishing inflammatory back pain, a useful screening tool for axSpA, which enables the distinction from other forms of chronic back pain [17]. Women, patients with younger age at onset of symptoms, patients with a negative HLA-B27 status, and patients with certain peripheral or extra-musculoskeletal manifestations, such as psoriasis, have also been observed to experience a longer time to diagnosis [9, 33–35]. Identifying the patient characteristics that may be associated with time to diagnosis warrants further study, for example, through multivariate regression analyses, as this could provide targets for the improvement of the patient diagnostic journey for patients at risk of diagnostic delay. Of note, in this study, women were found to have a significantly longer diagnostic delay than men. This aligns with previous research, which shows that, despite women reporting higher disease activity and significantly greater pain and functional limitation with axSpA, they experience longer diagnostic delay than men with axSpA [36]. Factors affecting this may include differences in early presentation, as women are less often HLA-B27-positive, and more often have nr-axSpA without visible radiographic abnormalities, requiring additional imaging for diagnosis [1, 37]. Further research is crucial to understand the factors leading to the sex differences observed in time to diagnosis and to identify targets for the improvement of the patient diagnostic journey for women with axSpA.

There are some key strengths of this study that should be noted. This study utilized a large patient cohort, and relied on claims data rather than subjective patient-reported data. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of the main analysis and the criteria applied for inclusion of patients, to determine any potential selection bias that might have been introduced due to the requirement of a minimum of 5 years of continuous medical and pharmacy coverage. Another strength was that patients with axSpA in this study were mostly comparable to those in published literature, although patients in this study were older on average at back pain diagnosis and axSpA diagnosis, which may limit generalizability [7, 10]. The average age of patient-reported symptom onset obtained from a previous survey in US patients was 26.4 years [10], which is considerably lower than the 48.8 years reported in this study, likely as a result of the differing methods employed to ascertain onset of back pain (diagnostic codes versus direct survey).

Limitations of this study include the fact that it assessed time from the earliest back pain diagnosis to axSpA diagnosis, rather than earliest back pain onset to axSpA diagnosis, hence time to diagnosis may have been underestimated. Patients may not seek healthcare immediately upon developing back pain, which may further contribute to this underestimation [38]. Additionally, the focus of this study is back pain symptom duration, and therefore patients with axSpA who presented with symptoms other than back pain may have been excluded. The impact of this limitation would be expected to be low, however, given that chronic back pain is one of the most common symptoms of axSpA [39]. Patients whose initial back pain was not definable and those without a back pain diagnosis code within the look-back period were excluded, which may have contributed to the underestimation of time to diagnosis as these patients’ back pain may have started years earlier. The analysis also excluded patients who were diagnosed with back pain during the look-back period but did not meet other inclusion criteria, also potentially contributing to the underestimation of the time to diagnosis. This study also makes no distinction between nr-axSpA and r-axSpA to assess differences in the time to diagnosis and the patient diagnostic journey; of note, differences have been reported in time to diagnosis between the two [8]. Furthermore, due to the use of claims data, this study cannot provide certainty on whether the earliest diagnosis or onset of back pain was recorded and reported in the database, which is a standard limitation of claims data. Long-term trends regarding the change in time to diagnosis over time are also not evaluated in this study. Claims data also do not capture the use of over-the-counter (OTC) medication, which may lead to an underestimation of NSAID use, for example, as some are available OTC. Potential regional influences on these findings were not explored, in part because there were no a priori reasons for differences by US region. The contributions of race, ethnicity, and other social determinants of health to time to diagnosis and access to care, which have previously been shown to have a considerable impact, were also not assessed in this analysis due to limited data availability [40–42]. Lastly, as the majority of patients were diagnosed by an HCP other than a rheumatologist, there may be a greater potential for diagnostic misclassification, which may affect the accuracy of the findings.

Conclusions

Early axSpA diagnosis is crucial for timely access to care and treatment. This study shows that diagnostic delay remains a challenge for patients with axSpA in the US, despite numerous back pain consultations, specialist visits, and diagnostic tests. Additionally, secondary delay to diagnosis after seeing a rheumatologist was also considerable, possibly due to uncertainty in diagnosis.

Disease burden on patients is heightened by the time to diagnosis, as indicated by the number of back pain consultations recorded, reliance on pain management, and the high number of diagnostic tests and imaging procedures patients undergo through the diagnostic journey. Through the axSpA diagnostic journey, HCRU and associated costs, including pharmacy prescriptions for pain management, are high. By characterizing the patient diagnostic journey and associated HCRU in axSpA, this study has identified key challenges and inefficiencies that need to be addressed to improve patient experience and reduce disease burden in axSpA. Further research should be conducted to identify predictors of diagnostic delay via multivariate analyses of associated factors.

There is an urgent need for strategies to overcome delays and expedite the time to diagnosis. Potential strategies include enhancing recognition of inflammatory back pain and axSpA in the field and improving referral pathways to rheumatology to expedite diagnosis, and enhanced education for non-rheumatologists, ultimately reducing the disease burden on patients and optimizing use of healthcare resources. Future studies should investigate the effectiveness of implementing these proposed strategies on the reduction of diagnostic delays in axSpA in a real-world clinical setting.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

The authors acknowledge Celia Menckeberg, PhD, UCB, The Netherlands, for publication coordination and editorial assistance and Sneha Krishnamurthy, MSc, and Patrick Cox, BSc (Hons), of Costello Medical, London, UK, for medical writing and editorial assistance based on the authors’ input and direction.

Author Contributions

Substantial contributions to study conception and design: Maureen Dubreuil, Marina Magrey, Kathrin Haeffs, Evgueni Ivanov, Julie Gandrup Horan; substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of the data: Maureen Dubreuil, Marina Magrey, Kathrin Haeffs, Evgueni Ivanov, Julie Gandrup Horan; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: Maureen Dubreuil, Marina Magrey, Kathrin Haeffs, Evgueni Ivanov, Julie Gandrup Horan; final approval of the version of the article to be published: Maureen Dubreuil, Marina Magrey, Kathrin Haeffs, Evgueni Ivanov, Julie Gandrup Horan.

Funding

This work was supported by UCB. Support for third-party writing assistance for this article, provided by Costello Medical, UK, was funded by UCB in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines (GPP 2022 (ismpp.org) https://www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022). The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by UCB.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Maureen Dubreuil: Received educational grant from Pfizer paid to institution; received consulting fees from Amgen and UCB; Marina Magrey: Received consultancy fees from AbbVie, BMS, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; received research grants from AbbVie, BMS, and UCB; Kathrin Haeffs, Evgueni Ivanov, Julie Gandrup Horan: Employees and shareholders of UCB.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies, performed by any of the authors, with human participants or animals. As the study analyzed a retrospective anonymized dataset, no ethical review and no informed consent of patients was needed. However, the study protocol was reviewed by a scientific steering committee and the data owner. The work on the dataset conformed to all social security data protection requirements.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: Previously presented at the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Convergence 2024 (November 14–19, 2024, Washington, DC).

References

- 1.Navarro-Compán V, Sepriano A, El-Zorkany B, et al. Axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1511–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh JA, Magrey M. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021;27:e547–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. New criteria for inflammatory back pain in patients with chronic back pain: a real patient exercise by experts from the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:784–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strand V, Singh JA. Patient burden of axial spondyloarthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2017;23:383–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.López-Medina C, Ramiro S, van der Heijde D, et al. Characteristics and burden of disease in patients with radiographic and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a comparison by systematic literature review and meta-analysis. RMD Open. 2019;5: e001108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deodhar A, Mittal M, Reilly P, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis diagnosis in US patients with back pain: identifying providers involved and factors associated with rheumatology referral delay. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1769–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hay CA, Packham J, Ryan S, et al. Diagnostic delay in axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic review. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41:1939–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao SS, Pittam B, Harrison NL, et al. Diagnostic delay in axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:1620–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magrey M, Walsh JA, Flierl S, et al. The international map of axial spondyloarthritis survey: a US patient perspective on diagnosis and burden of disease. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2023;5:264–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiwalkar S, Howard R, Choi D, et al. A mixed methods study to uncover impediments to accurate diagnosis of nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis in the USA. Clin Rheumatol. 2023;42:2811–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogdie A, Benjamin Nowell W, Reynolds R, et al. Real-world patient experience on the path to diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Ther. 2019;6:255–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haroon N, Inman RD, Learch TJ, et al. The impact of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors on radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2645–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karmacharya P, Duarte-Garcia A, Dubreuil M, et al. Effect of therapy on radiographic progression in axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:733–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mauro D, Forte G, Poddubnyy D, et al. The role of early treatment in the management of axial spondyloarthritis: challenges and opportunities. Rheumatol Ther. 2024;11:19–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lapane KL, Dubé C, Ferrucci K, et al. Patient perspectives on health care provider practices leading to an axial spondyloarthritis diagnosis: an exploratory qualitative research study. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22:251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magrey M, Yi E, Wolin D, et al. Understanding barriers in the pathway to diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis: results from a US survey of 1690 physicians from 10 specialties. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2:616–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poddubnyy D, Sieper J. Current unmet needs in spondyloarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2019;21:43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Data Assets | Johns Hopkins Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/center-for-drug-safety-and-effectiveness/data-assets.

- 20.Fritz JM, Kim J, Thackeray A, et al. Use of physical therapy for low back pain by Medicaid enrollees. Phys Ther. 2015;95:1668–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calip GS, Adimadhyam S, Xing S, et al. Medication adherence and persistence over time with self-administered TNF-alpha inhibitors among young adult, middle-aged, and older patients with rheumatologic conditions. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merola JF, Dennis N, Chakravarty SD, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the USA—a retrospective study of claims data from 2009 to 2020. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:4061–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yi E, Dai D, Piao OW, et al. Health care utilization and cost associated with switching biologics within the first year of biologic treatment initiation among patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27:27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis JR, Winthrop K, Bohn RL, et al. The annual diagnostic prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis in the United States using Medicare and MarketScan databases. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2021;3:743–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danve A, Vadhariya A, Lisse J, et al. Ixekizumab treatment patterns and health care resource utilization among patients with axial spondyloarthritis: a retrospective United States claims database study. Rheumatol Ther. 2024;11:1333–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Driscoll D, George N, Peloquin C, et al. Association of therapies for axial spondyloarthritis on the risk of hip and spine fractures. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2025;77:677–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopson S, Gibbs LR, Syed S, et al. Treatment patterns and healthcare resource utilization among newly diagnosed psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, and hidradenitis suppurativa patients with past diagnosis of an inflammatory condition: a retrospective cohort analysis of claims data in the United States. Adv Ther. 2023;40:4358–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrido-Cumbrera M, Poddubnyy D, Sommerfleck F, et al. International map of axial spondyloarthritis (IMAS): results from the perspective of 5557 patients from 27 countries around the globe. RMD Open. 2024;10:e003504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrido-Cumbrera M, Poddubnyy D, Sommerfleck F, et al. Regional differences in diagnosis journey and healthcare utilization: results from the International Map of Axial Spondyloarthritis (IMAS). Rheumatol Ther. 2024;11:927–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, et al. 2019 update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71:1285–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mennini FS, Viti R, Marcellusi A, et al. Economic evaluation of spondyloarthritis: economic impact of diagnostic delay in Italy. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yi E, Ahuja A, Rajput T, et al. Clinical, economic, and humanistic burden associated with delayed diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatol Ther. 2020;7:65–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldtkeller E, Khan MA, van der Heijde D, et al. Age at disease onset and diagnosis delay in HLA-B27-negative vs -positive patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int. 2003;23:61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jovaní V, Blasco-Blasco M, Ruiz-Cantero MT, et al. Understanding how the diagnostic delay of spondyloarthritis differs between women and men: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2017;44:174–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Redeker I, Callhoff J, Hoffmann F, et al. Determinants of diagnostic delay in axial spondyloarthritis: an analysis based on linked claims and patient-reported survey data. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58:1634–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rusman T, van Vollenhoven RF, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE. Gender differences in axial spondyloarthritis: women are not so lucky. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Navarro-Compán V, Garrido-Cumbrera M, Poddubnyy D, et al. Females with axial spondyloarthritis have longer diagnostic delay and higher burden of the disease. Results from the International Map of Axial Spondyloarthritis (IMAS). Int J Rheum Dis. 2024;27:e15433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan A, Rigler K, Ahmad N, et al. Progressive improvement in time to diagnosis in axial spondyloarthritis through an integrated referral and education system. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2024;8:rkae102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Gaalen FA, Rudwaleit M. Challenges in the diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2023;37:101871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferrandiz-Espadin R, Rabasa G, Gasman S, et al. Disparities in time to diagnosis of radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2025;52:344–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ly DP. Racial and ethnic disparities in the evaluation and management of pain in the outpatient setting, 2006–2015. Pain Med. 2019;20:223–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Milani CJ, Rundell SD, Jarvik JG, et al. Associations of race and ethnicity with patient-reported outcomes and health care utilization among older adults initiating a new episode of care for back pain. Spine (Phila PA 1976). 2018;43:1007–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.