Abstract

Introduction

While the literature on esketamine use in commercially insured patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) is growing, data on Medicaid beneficiaries remain limited. This study aimed to fill this gap by exploring characteristics of Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD who initiated esketamine treatment in the United States.

Methods

Adults with TRD initiating esketamine on/after 03/05/2019 (index date) were selected from the Merative™ MarketScan® Multi-State Medicaid Database (01/2016–06/2022). Baseline was 12 months pre-index date; follow-up spanned from the index date until the end of health plan insurance or data. Patient baseline characteristics and follow-up treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization (HRU), and medical costs were reported.

Results

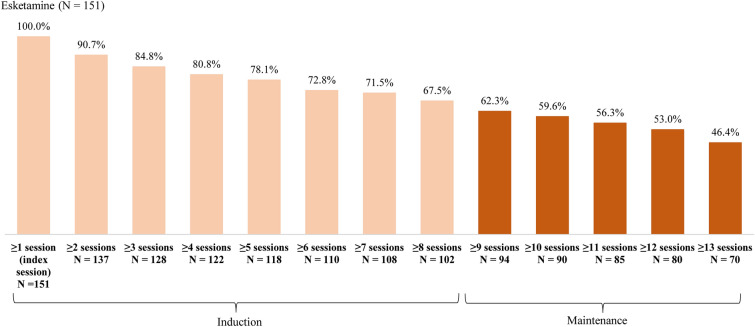

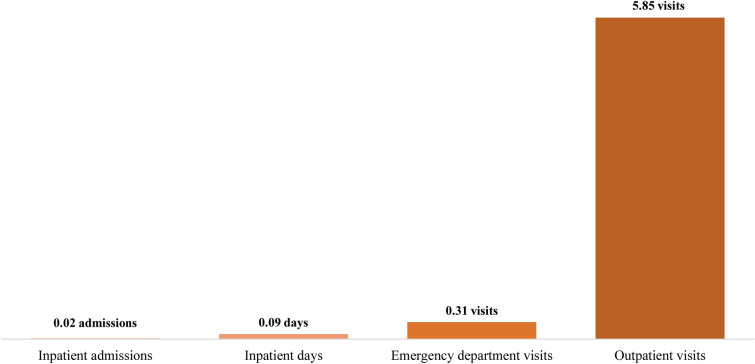

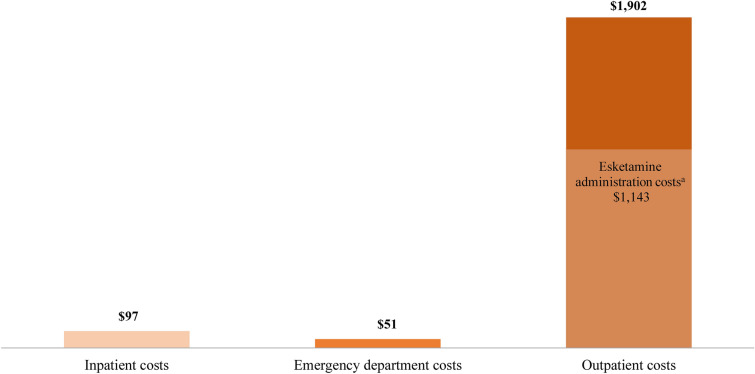

A total of 151 patients were identified (mean age: 40.6 years; female: 70.2%; racial minorities: 31.1%). The most common comorbidities were anxiety (81.5%), sleep–wake disorders (47.0%), trauma-related disorders (43.0%), substance-related disorders (30.5%), and obesity (30.5%). Patients completed a mean of 22.5 esketamine sessions; 67.5% of patients completed the induction phase (≥ 8 sessions), 62.3% initiated the maintenance phase, and 53.0% completed ≥ 12 sessions. After esketamine initiation, patients had a mean of 0.02 inpatient admissions, 0.09 inpatient days, 0.31 emergency department visits, and 5.85 outpatient visits monthly. The mean follow-up medical costs were $2075 monthly, including inpatient costs of $97, emergency department costs of $51, and outpatient costs of $1902.

Conclusion

Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD who initiated esketamine treatment had a high comorbidity burden and a higher proportion of racial minorities than the US population overall. Nonetheless, most patients progressed to maintenance phase of esketamine treatment. Findings suggest that esketamine may be a viable treatment option for this complex patient population.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-025-00802-1.

Keywords: Treatment-resistant depression, Major depressive disorder, Esketamine, Medicaid, Patient profiles, Claims

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Medicaid beneficiaries with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) have high comorbidity and healthcare needs. |

| Esketamine nasal spray is a novel therapy for TRD; however, little is known about the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, healthcare resource use, and costs of Medicaid beneficiaries treated with esketamine. |

| This study explored characteristics of Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD who initiated esketamine treatment in the United States (US). |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD who initiated esketamine treatment had a high comorbidity burden and a higher proportion of racial minorities than the US population overall. |

| Even in this complex patient population, most patients initiating treatment with esketamine nasal spray progressed to the maintenance phase of treatment, suggesting that esketamine may be a viable treatment option for Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD and could be integrated into treatment regimens. |

Introduction

Medicaid is the single largest payer for mental health services in the United States (US) [1]. Administered by states and funded jointly by the federal government, Medicaid currently provides basic health coverage to over 80.9 million Americans, including eligible low-income adults, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people with disabilities [2, 3]. In 2020, Medicaid covered 18% of the general nonelderly adult population and 23% of nonelderly adults with mental illness [4]. Overall, the socioeconomic composition of Medicaid beneficiaries and their mental health burden underline the need to understand the use and outcomes of novel therapies for mental health disorders in this population.

Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) is a form of major depressive disorder (MDD) with inadequate response to at least two antidepressants [5]. Adults with TRD incur substantially and persistently higher healthcare costs than those with non-TRD MDD and without MDD [6], which also holds true for Medicaid beneficiaries [7].

Effective treatment options are critical to helping alleviate the burden associated with TRD. Conventional treatments for TRD include antidepressant combinations, non-antidepressant augmentation agents, electroconvulsive therapy, and transcranial magnetic stimulation [8, 9]. The novel therapy esketamine nasal spray, in combination with an oral antidepressant, was approved in 2019 for TRD in adults [10, 11]. Esketamine can provide relief from depressive symptoms as soon as 24 h after the first dose [12], and evidence from clinical trials and real-world data indicates clinical benefits associated with initiating esketamine treatment in patients with TRD [12, 13]. As of January 2025, esketamine has been approved for TRD as a monotherapy [14, 15].

Esketamine prescribing rates among the Medicaid beneficiaries remained low in the first 2 years after its approval [16]. This may be in part due to providers’ reluctance to take on Medicaid beneficiaries, as providers generally receive lower compensation for their care under the Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS) model compared to commercial insurance [17]. Furthermore, in Medicaid managed care plans, many state programs may have behavioral health services provided through FFS or by limited benefit plans, which may impact health equity, further disadvantaging the vulnerable population [17].

While the literature on commercially insured patients with TRD treated with esketamine nasal spray is growing [18, 19], little is known about its use in Medicaid beneficiaries. This study aimed to fill this gap in the literature by describing sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and healthcare resource use (HRU) and costs of adult Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD who initiated treatment with esketamine nasal spray in the US.

Methods

Data Source

The Merative™ MarketScan® Multi-State Medicaid Database (01/2016–06/2022) was used. The database consists of healthcare experience of individuals enrolled in state Medicaid programs for several states; specific states included are not disclosed and cannot be differentiated. The data included medical and prescription drug claims, demographic variables including race and ethnicity, Medicaid aid category, and monthly information on health plan enrollment.

This study was considered exempt research under 45 CFR § 46.104(d)(4) as it involved only the secondary use of data that were de-identified in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), specifically, 45 CFR § 164.514.

Study Design

A retrospective observational design was used. The intake period spanned from 03/05/2019 (esketamine approval date for TRD in the US) to 06/30/2022. The index date was the date of the first claim for esketamine. The 12-month baseline period before the index date was used to describe patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. The follow-up period spanned from the index date to the end of continuous health plan eligibility or data availability and was used to describe esketamine treatment patterns, HRU, and medical costs.

Study Population and Sample Selection

The study population included Medicaid beneficiaries meeting the following criteria: (1) had a first claim for esketamine during the intake period (see Supplementary Table S1 for drug and procedure codes); (2) had evidence of TRD before or on the index date, defined as ≥ 2 unique antidepressants of adequate dose (see Supplementary Table S2 for definitions [20, 21]) and duration (i.e., 6 weeks of continuous therapy with no gaps > 14 days) within the same major depressive episode as the index date; (3) were ≥ 18 years old at the index date; (4) had ≥ 12 months of continuous insurance eligibility before the index date; and (5) had ≥ 1 diagnosis of MDD during the baseline period (see Supplementary Table S1 for diagnosis codes).

Patients were excluded if they had evidence of bipolar disorder or psychosis, schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder, or other non-mood psychotic disorders (defined as having ≥ 2 unique claims for the condition during the baseline period; see Supplementary Table S1 for diagnosis codes).

Outcome Measures

Esketamine treatment patterns were measured during the follow-up period based on the information in medical and pharmacy claims for esketamine. The dose of eight esketamine treatment sessions (i.e., number of induction sessions [10]) was identified based on the National Drug Code and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes for esketamine pharmacy and medical claims (56 mg or 84 mg; Supplementary Table S1). Adherence was not assessed, since esketamine is a nasal spray treatment required to be administered in an outpatient setting. Nonetheless, the number of sessions completed was reported.

HRU and medical costs were reported per patient per month (PPPM) during the follow-up period. HRU included inpatient admission, inpatient days, emergency department visits, and outpatient visits. Costs were reported from a payer perspective and inflated to 2022 US dollars.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics, treatment patterns, HRU, and medical costs were described using means, standard deviations (SDs), and medians for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for binary variables.

Results

Patient Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 151 patients with TRD initiating esketamine were included (Table 1). The mean patient age was 40.6 years, and most patients were female (70.2%). While the majority of patients were White (58.3%), racial/ethnic minorities (i.e., Black, Hispanic, and other races/ethnicities) comprised close to a third of the study population (31.1%).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in the baseline period

| Mean ± SD [median] or n (%) | Patients |

|---|---|

| N = 151 | |

| Length of follow-up (months) | 13.2 ± 10.3 [10.9] |

| Age at index date (years) | 40.6 ± 11.5 [39.2] |

| Female | 106 (70.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 88 (58.3) |

| Black | 13 (8.6) |

| Hispanic | 6 (4.0) |

| Other | 28 (18.5) |

| Unknown or missing | 16 (10.6) |

| Year of index date | |

| 2019 | 18 (11.9) |

| 2020 | 37 (24.5) |

| 2021 | 55 (36.4) |

| 2022 | 41 (27.2) |

| Common behavioral and physical conditions | |

| Anxiety disorders | 123 (81.5) |

| Sleep–wake disorders | 71 (47.0) |

| Trauma- and stressor-related disorders | 65 (43.0) |

| Substance-related and addictive disorders | 46 (30.5) |

| Neurodevelopmental disorders | 46 (30.5) |

| Obesity | 46 (30.5) |

| Hypertension | 41 (27.2) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 37 (24.5) |

| Suicidal ideation and probable attempt | 31 (20.5) |

| Evidence of antipsychotics use | 82 (54.3) |

| Number of unique antidepressants useda | |

| ≥ 3 | 94 (62.3) |

| ≥ 4 | 38 (25.2) |

| ≥ 5 | 20 (13.2) |

SD standard deviation

aUnique antidepressant agents were grouped according to the generic name (e.g., Paxil® and paroxetine would be considered the same agent)

Over half of patients used antipsychotics (54.3%) and received ≥ 3 antidepressants (62.3%) during the baseline period. The most frequent behavioral comorbid conditions were anxiety disorders (81.5%), sleep–wake disorders (47.0%), trauma- and stressor-related disorders (43.0%), and substance-related and addictive disorders (30.5%). The most frequent physical comorbid conditions were obesity (30.5%), hypertension (27.2%), and chronic pulmonary disease (24.5%).

Esketamine Treatment Patterns

With a mean follow-up of 13.2 months, patients completed a mean of 22.5 esketamine treatment sessions. About two-thirds (67.5%) of patients completed induction treatment (i.e., ≥ 8 sessions [10]), 62.3% initiated maintenance treatment, and 53.0% completed ≥ 12 sessions (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patients with esketamine treatment sessions

While most patients (61.6%) accessed esketamine through pharmacy benefits, a considerable proportion of patients (45.7%) received the treatment through medical benefits. In terms of dose, fewer than 30% of patients received the 84-mg dose on the index date, and by the eighth session, more than 75% of patients who completed induction were on the 84-mg dose (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Dose of esketamine for the first eight treatment sessions

After initiation of esketamine, patients received a mean of 2.3 unique antidepressants during the follow-up period. Furthermore, the majority of patients (72.2%) also received psychotherapy, while less than a third (27.8%) had a psychologist visit during the follow-up period.

Healthcare Resource Use

During the follow-up period, outpatient visits accounted for most of the HRU (Fig. 3). The mean ± SD [median] inpatient admissions PPPM were 0.02 ± 0.05 [0.00] and inpatient days were 0.09 ± 0.31 [0.00], whereas mean ± SD [median] emergency department visits PPPM were 0.31 ± 2.44 [0.00]. Meanwhile, mean ± SD [median] outpatient visits PPPM were 5.85 ± 4.24 [4.87].

Fig. 3.

Mean follow-up healthcare resource use per patient per month

Medical Costs

The mean ± SD [median] follow-up medical costs were $2075 ± $2505 [$1133] PPPM, including inpatient costs of $97 ± $290 [$0], emergency department costs of $51 ± $133 [$0], and outpatient costs of $1902 ± $2508 [$966] PPPM; 60.1% of the outpatient costs were related to esketamine administration (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mean follow-up medical costs per patient per month. aEsketamine administration costs were identified based on medical claims for esketamine with Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes G2082, G2083, and S0013, and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Procedure Coding System code: XW097M5

Discussion

Medicaid beneficiaries represent a socioeconomically vulnerable population with a higher prevalence of racial and ethnic minorities and a greater burden of mental health conditions than the US general public [1, 22]. In the current study, the sociodemographic profiles of Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD reflect a higher proportion of racial/ethnic minorities (31.1%) and women (70.2%) compared with the US average based on census data (racial minorities: 24.7%; women: 50.5%) [23]. Additionally, relative to commercially insured individuals with TRD initiating treatment with esketamine, patients in this study also had a higher prevalence of comorbidities [18], consistent with the Medicaid beneficiary profile [22].

Understanding patterns of esketamine use among Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD is important for improving health equity among this vulnerable population. A previous study among Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD identified 51,206 patients during the same time span as covered by our study, suggesting that less than 0.3% initiated esketamine during this time frame [24]. Chances of esketamine treatment initiation among Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD trended lower for females, while use of second-generation antipsychotics, psychotherapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and electroconvulsive therapy and symptoms and comorbidities including suicidal ideation or probable attempt, sleep–wake disorders, and hypothyroidism substantially increased the chances of initiating esketamine treatment, all else being equal [24]. These findings suggest that esketamine is reserved for a small and clinically severe group of Medicaid beneficiaries who have already attempted other therapeutic approaches. In our study, most patients who initiated esketamine progressed to maintenance treatment. Contrary to expectations that Medicaid beneficiaries might face more barriers to continued esketamine care, relative to commercially insured patients from a recent claims study using IBM MarketScan data [18], the proportion of patients who completed induction treatment trended higher (commercially insured: 61.3%; Medicaid: 67.5%), similarly to the proportion of patients who completed ≥ 4 maintenance treatment sessions (commercially insured: 40.5%; Medicaid: 53.0%). These differences in esketamine use patterns by type of health plan coverage may be partially due to a higher proportion of Medicaid beneficiaries who are not working [25], which may make it easier for them to receive esketamine treatment sessions than for commercially insured patients. Interestingly, high use of psychotherapy among Medicaid beneficiaries receiving esketamine may have contributed to the overall treatment engagement. While direct evidence on the combined effects of esketamine and psychotherapy remains limited, it is an emerging area of interest. Some researchers hypothesize that psychotherapy may have potential to sustain the antidepressant effects of esketamine, while esketamine may enhance neuroplasticity and, in theory, make patients more receptive to psychotherapeutic interventions [26, 27].

Further, relative to commercially insured patients with TRD from the same study [18], Medicaid beneficiaries in this study had a similar mean number of inpatient admissions during the follow-up period (commercially insured: 0.03 admissions PPPM; Medicaid: 0.02 admissions PPPM) but a higher mean number of emergency department visits (commercially insured: 0.09 visits PPPM; Medicaid: 0.31 visits PPPM). The higher rate of emergency department care use by Medicaid beneficiaries has been recognized and may be partially attributable to their higher disease burden and difficulty in accessing high-quality primary care services [28]. Yet, despite the overall higher acute care service use among Medicaid beneficiaries, their mean acute care payer costs during the follow-up period appeared considerably lower (commercially insured: $948 PPPM; Medicaid: $148 PPPM) [18]. The mismatch between HRU and costs may be presumably due to the lower Medicaid FFS payment rates for physician services [17].

Administration of esketamine in a certified healthcare setting is essential under the Spravato® Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) to control for the risks of potential adverse outcomes and abuse and misuse of esketamine [10]. Real-world studies found that adverse reactions to esketamine were generally transient and mild, and reported misuse or abuse was generally scarce, confirming esketamine’s safety across diverse patient populations [13, 29]. In line with the administration requirement of esketamine in a certified healthcare setting, outpatient visits accounted for a large portion of follow-up HRU and medical costs incurred by Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD in this study. However, outpatient administration may also pose challenges for therapy compliance, such as the need to arrange for transportation and caregiver time (as patients need to be driven home after esketamine treatment sessions) and lack of motivation in depressed patients to attend appointments [30, 31]. Despite these potential obstacles, the treatment patterns observed in this study suggest that esketamine may represent a sustainable treatment option with manageable resource utilization for Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD.

Findings presented herein should be interpreted with caution given the descriptive nature of the study. Further, pharmacy claims were used to identify TRD; however, pharmacy claims do not guarantee that the medication dispensed was taken as prescribed and do not capture medications dispensed over the counter or as samples. Claims data generally contain limited clinical information (e.g., depression severity, treatment response, side effects, reasons for treatment discontinuation). In addition, claims databases may contain billing errors or omissions in coded procedures, diagnoses, and pharmacy claims. It should also be noted that results may not be generalizable to uninsured patients and patients covered by insurance plans other than Medicaid.

Conclusion

This study among Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD included a higher proportion of racial and ethnic minorities than the average US population and showed a substantial prevalence of comorbidities and acute care use. Nonetheless, most patients who initiated esketamine nasal spray treatment progressed to maintenance treatment. Overall, findings from this study suggest that esketamine may be a feasible treatment option for Medicaid beneficiaries with TRD. While further research is needed, particularly in controlled settings, these descriptive findings indicate that esketamine could be integrated into clinical practice even among populations with higher comorbidity and healthcare needs.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by professional medical writer, Flora Chik, PhD, MWC, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript.

Author Contributions

Kristin Clemens, Maryia Zhdanava, Amanda Teeple, Arthur Voegel, Aditi Shah, Hannah E Bowrey, Anabelle Tardif-Samson, Dominic Pilon and Kruti Joshi have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the study, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content, and have provided final approval of this version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was funded by Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine. The sponsor also funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Merative™ MarketScan®. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data used in this study can be accessed under license from Merative™ MarketScan®.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Kristin Clemens is part of the Advanced Practice Provider Publication for Janssen Neuroscience US Medical Affairs, Medical Affairs Steering Committee September Advisory Board, consultant for Sage Therapeutics, Inc., speaker for AbbVie, and an adjunct professor at George Mason University. Maryia Zhdanava, Arthur Voegel, Aditi Shah, Anabelle Tardif-Samson and Dominic Pilon are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine, which funded the development and conduction of this study. Amanda Teeple, Hannah E Bowrey, and Kruti Joshi are employees of Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine and stockholders of Johnson & Johnson.

Ethical Approval

This study was considered exempt research under 45 CFR § 46.104(d)(4) as it involved only the secondary use of data that were de-identified in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), specifically, 45 CFR § 164.514.

Footnotes

Prior presentation: Parts of the material in this manuscript were presented at the Psych Congress held September 6–10, 2023, in Nashville, TN, USA, and at the Neuroscience Education Institute (NEI) Congress held November 09–12, 2023, in Colorado Springs, CO, USA, as poster presentations.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Behavioral Health Spending & Use Accounts 2006–2015. 2019.

- 2.Medicaid.gov. Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights 2024 [accessed September 23, 2024]. Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html.

- 3.Congressional Research Services. U.S. health care coverage and spending 2020. 2022.

- 4.Guth M. State policies expanding access to behavioral health care in medicaid. Data Source: 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2021.

- 5.Gaynes BN, Asher G, Gartlehner G, et al. Technology assessment program-definition of treatment-resistant depression in the medicare population. Technology Assessment Program. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhdanava M, Kuvadia H, Joshi K, et al. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression in privately insured US patients with physical conditions. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(8):996–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olfson M, Amos TB, Benson C, et al. Prospective service use and health care costs of Medicaid beneficiaries with treatment-resistant depression. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(3):226–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, third edition. 2010; p. 1–152.

- 9.Otte C, Gold SM, Penninx BW, et al. Major depressive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;15(2):16065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. SPRAVATO® (esketamine) Prescribing Information. Titusville: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 11.FDA Approves New Nasal Spray Medication for Treatment-Resistant Depression; Available Only at a Certified Doctor’s Office or Clinic [Internet]. March 5, 2019 [accessed January 11, 2024]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-nasal-spray-medication-treatment-resistant-depression-available-only-certified.

- 12.Popova V, Daly EJ, Trivedi M, et al. Efficacy and safety of flexibly dosed esketamine nasal spray combined with a newly initiated oral antidepressant in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized double-blind active-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):428–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brendle M, Ahuja S, Valle MD, et al. Safety and effectiveness of intranasal esketamine for treatment-resistant depression: a real-world retrospective study. J Comp Eff Res. 2022;11(18):1323–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen Research & Development LLC. A Study of Esketamine Nasal Spray, Administered as Monotherapy, in Adult Participants With Treatment-resistant Depression. 2025 [accessed February 26, 2025]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04599855.

- 15.Janik A, Qiu X, Lane R, et al. Efficacy and safety of Esketamine nasal spray as monotherapy in adults with treatment-resistant depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neuroscience Applied. 2024;3: 105279. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aguilar AG, Beauregard BA, Conroy CP, et al. Pronounced regional variation in esketamine and ketamine prescribing to US medicaid patients. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2023;1:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Provider payment and delivery systems 2024 [accessed January 12, 2024]. Available from: https://www.macpac.gov/medicaid-101/provider-payment-and-delivery-systems/

- 18.Joshi K, Pilon D, Shah A, et al. Treatment patterns, healthcare utilization, and costs of patients with treatment-resistant depression initiated on esketamine intranasal spray and covered by US commercial health plans. J Med Econ. 2023;26(1):422–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karkare S, Zhdanava M, Pilon D, et al. Characteristics of real-world commercially insured patients with treatment-resistant depression initiated on esketamine nasal spray or conventional therapies in the United States. Clin Ther. 2022;44(11):1432–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ), Non-Geriatric Population, version 2. 2015.

- 21.Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ), Geriatric Population, version 3. 2016.

- 22.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2023 Medicaid and CHIP Beneficiary Profile: Enrollment, Expenditures, Characteristics, Health Status, and Experience. 2023 [accessed September 10, 2024]. Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/downloads/beneficiary-profile-2023.pdf.

- 23.U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts United States 2023 [accessed September 23, 2024]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US.

- 24.Clemens K, Zhdanava M, Teeple A, et al. Impact of social determinants of health on esketamine nasal spray initiation among patients with treatment-resistant depression in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2025;31(1):101–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE). State Level Estimates of Medicaid Enrollees Currently Working and their Demographic Characteristics. 2023.

- 26.Mikellides G. Ketamine and esketamine in psychiatry: A comparative review emphasizing neuroplasticity and clinical applications. Psychoactives. 2025;4(3):20. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitay BM, Murphy E, Macaluso M, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy following esketamine for major depression and suicidal ideation for relapse prevention: the CBT-ENDURE randomized clinical trial study protocol. Psychiatry Res. 2023;330: 115585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim H, McConnell KJ, Sun BC. Comparing emergency department use among Medicaid and commercial patients using all-payer all-claims data. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20(4):271–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roncero C, Merizalde-Torres M, Szerman N, et al. Is there a risk of esketamine misuse in clinical practice? Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2025;16:20420986241310684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. 2013;38:976–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teeple A, Zhdanava M, Pilon D, et al. Access and real-world use patterns of esketamine nasal spray among patients with treatment-resistant depression covered by private or public insurance. Curr Med Res Opin. 2023;3:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Merative™ MarketScan®. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data used in this study can be accessed under license from Merative™ MarketScan®.