Abstract

Introduction

In clinical practice, switching between preventive treatments is common in patients with chronic migraine when efficacy is insufficient or tolerability is poor. With the advent of more targeted therapies, such as onabotulinumtoxinA and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies, treatment options have expanded, yet evidence to guide sequencing decisions remains limited. The aim of this study was to investigate the real-world effectiveness of switching between onabotulinumtoxinA and erenumab and vice versa in patients with chronic migraine who showed inadequate response to their initial preventive treatment.

Methods

This retrospective real-world study included patients with chronic migraine treated at the Headache Center, Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin between October 2022 and December 2024. Eligible patients had received both onabotulinumtoxinA and erenumab in sequence, switching as a result of insufficient efficacy or tolerability. A very good response was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction in monthly headache days in the third month after the switch.

Results

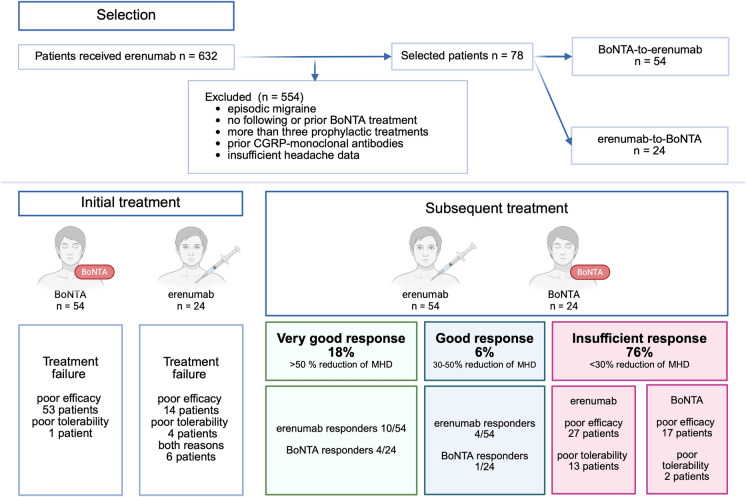

Out of 632 screened patients, 78 met the inclusion criteria (84.6% female; mean age 43 ± 14 years). Of these, 54 switched from onabotulinumtoxinA to erenumab, and 24 from erenumab to onabotulinumtoxinA. A very good response was observed in 14 patients (17.9%): 10/54 (18.5%) after switching to erenumab and 4/24 (16.7%) after switching to onabotulinumtoxinA.

Conclusion

Sequential preventive treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA and erenumab resulted in a very good response in about one-fifth of patients. Although both treatments target the CGRP pathway, their distinct mechanisms of action may still provide benefit when switching therapies after initial failure.

Keywords: Erenumab, OnabotulinumtoxinA, CGRP, Migraine, Trigeminovascular system, Pain

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Chronic migraine is a highly disabling condition, and many patients do not respond to initial preventive therapies, creating an unmet need for effective strategies. |

| OnabotulinumtoxinA and erenumab both target CGRP-related mechanisms, raising the question of whether switching after the initial therapy failed offers clinical benefit. |

| What was learned from this study? |

| Approximately 18% of patients experienced a ≥ 50% reduction in monthly headache days after switching treatments, with no significant difference between onabotulinumtoxinA-to-erenumab and erenumab-to-onabotulinumtoxinA sequences. |

| While the overall response rate was modest, findings suggest that treatment switching may be beneficial for a subset of patients. |

| The results underscore the need for personalized treatment strategies and highlight the importance of identifying biomarkers or clinical predictors of response in future prospective studies. |

Introduction

Effective preventive strategies are essential to reduce the global burden of migraine, one of the leading causes of disability worldwide [1, 2]. For chronic migraine, current guidelines recommend oral preventives (e.g., beta-blockers) and onabotulinumtoxinA (BoNTA) as first-line options [3]. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-targeted monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) offer a more specific alternative and are considered first-line in some guidelines, though reimbursement policies often restrict their use to patients who have not responded to conventional treatments [3].

BoNTA is administered every 12 weeks following the PREEMPT protocol, which involves 155–195 units injected across at least 31 sites on the head and neck [4, 5]. BoNTA cleaves synaptosomal-associated 25 kDa protein (SNAP-25), a SNAP receptor (SNARE) complex protein, thereby inhibiting the exocytotic release of pro-inflammatory and excitatory neurotransmitters such as CGRP, glutamate, and substance P from presynaptic C-fiber nociceptors [6]. In addition, BoNTA reduces the insertion of pain-related ion channels (e.g., TRPV1, TRPA1) into the neuronal membrane, further dampening nociceptive transmission [7].

CGRP mAbs act selectively on the CGRP pathway. Ligand-binding mAbs (galcanezumab, fremanezumab, eptinezumab) bind soluble CGRP, while erenumab targets the canonical CGRP receptor [8]. As a result of their large molecular size, these antibodies do not cross the blood–brain barrier and instead act at peripheral sites such as the trigeminal ganglion, where only Aδ fibers express the CGRP receptor components [9].

Given their targets of distinct molecular and anatomical structures,BoNTA acting mainly on C-fibers and CGRP mAbs on Aδ fibers,these treatments may offer complementary or alternative effects.

This has led to interest in both combination therapy and treatment sequencing. Existing evidence for the combination of both therapies remains inconclusive: some studies suggest additive benefits, while others report no increased efficacy when treatments are combined [10, 11]. Studies have investigated and reported a benefit after switching from BoNTA to erenumab [12, 13]. Nevertheless, to date, no study has investigated the bidirectional switch.

Given that treatment efficacy often declines with each subsequent preventive option, clinical data on sequential use are urgently needed to support personalized, evidence-based strategies [14]. Patients with chronic migraine are often highly burdened, and more targeted approaches may help improve outcomes more rapidly and precisely.

This brief report aims to explore the real-world effectiveness of sequential use of BoNTA and erenumab in patients with chronic migraine following an inadequate response to initial preventive treatment. These findings may serve as a foundation for larger studies and more targeted therapeutic approaches.

Methods

Participants

This retrospective study was conducted at the Headache Center, Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin. We screened all patients who received treatment with erenumab between October 2022 and December 2024. Patients were included in the analysis if they had a documented diagnosis of chronic migraine, according to the criteria defined by the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) [15]. Eligible patients had sequentially received both erenumab and BoNTA during the observation period. Psychiatric or somatic comorbidities or other comorbid headache disorders such as medication overuse headache (MOH) were not considered as exclusion criteria. We considered only patients who had not received more than three other preventive treatments and had not received other CGRP mAbs before or between the use of erenumab and BoNTA. In addition, BoNTA had to be administered in accordance with the PREEMPT protocol. On the basis of treatment sequences, patients were pre-categorized into two groups. The first group included patients who started with BoNTA and subsequently received erenumab (BoNTA-to-erenumab). The second group consisted of patients who received erenumab first and were later switched to BoNTA (erenumab-to-BoNTA).

Procedures and Outcomes

We collected the headache data from standardized diaries (electronic or paper-based), which are routinely collected during outpatient visits in our headache center. When diary data were unavailable, we referred to physician notes documenting the headache frequency of patients; patients without any headache documentation were excluded. We standardized monthly headache frequency to a 28-day month, defining a headache day as any day with a recorded headache.

Patients were considered to have failed their initial preventive treatment (BoNTA or erenumab) if it was discontinued because of either insufficient efficacy, poor tolerability, or both. Insufficient efficacy was defined as failure to achieve at least a 50% reduction in monthly headache days (MHD) after 3 months of treatment, relative to the month preceding therapy. Poor tolerability was defined as discontinuation of treatment due to side effects, as documented in clinical records.

We defined a very good response to the subsequent treatment as a reduction of more than 50% in MHD after 3 months, compared to the final month of the initial treatment prior to discontinuation. Additionally, we performed a secondary analysis using a 30% reduction in MHD as recommended acceptable marker for treatment efficacy in chronic migraine. In contrast, insufficient response was defined as a reduction of less than 30% in MHD after 3 months and/or discontinuation due to side effects [16].

Statistical Analysis

We conducted all analyses using R version (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) in the RStudio v2024.12.1 + 563 environment (Posit PBC, Boston, MA, USA). Categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages, and age is presented as mean (SD). Because MHD were not normally distributed, we reported them as median (IQR). To compare age between groups, we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For monthly headache days, we applied the Kruskal–Wallis test. We assessed group differences in categorical variables, including sex, migraine aura, smoking, and comorbidities such as depression, anxiety, and hypertension, using the Fisher’s exact test.

Ethical Approval

The retrospective data analysis of clinical routine data of headache patients has been approved by the Charité Ethical Committee (EA1/159/22). No specific ethical approval or written informed consent for participation was required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements, and followed Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for cohort studies [17].

Results

Out of 632 screened patients, we included 78 patients in the final analysis with 54 in the BoNTA-to-erenumab group and 24 in the erenumab-to-BoNTA group.

For the BoNTA-to-erenumab group, the median duration of the initial treatment phase was two treatment cycles, each administered every 12 weeks (range 1–25 cycles). One patient discontinued BoNTA because of tolerability issues (neck pain), 11 discontinued after one cycle as a result of worsening headache frequency, and the remaining patients discontinued after at least two cycles because of insufficient efficacy. The median interval between the last BoNTA injection and the first administration of erenumab was 110 days (range 39–715 days).

In the erenumab-to-BoNTA group, the initial treatment phase lasted in median about 17 weeks (range 4–52 weeks). Fourteen patients stopped erenumab as a result of lack of efficacy, four because of tolerability issues (including constipation, impaired wound healing, or sleep disturbance) and six owing to both. The interval between the last self-administered dose of erenumab and the BoNTA injection was a median of 31 days (range 15–217 days).

After switching treatments, a total of 14 patients (17.9%) achieved a very good response (≥ 50% reduction in MHDs): 10 responded to erenumab (18.5% of the BoNTA-to-erenumab group), and four to BoNTA (16.7% of the erenumab-to-BoNTA group), with no significant difference between responder groups (p > 0.999). The remaining 59 patients (75.6%) insufficiently responded to the second treatment, mostly as a result of poor efficacy.

In the erenumab-to-BoNTA group, ten patients discontinued BoNTA after at least two cycles. Of these, two patients discontinued because of tolerability issues, specifically shoulder and neck pain, while the remaining patients discontinued as a result of lack of efficacy. In the BoNTA-to-erenumab group, 13 patients reported tolerability issues (obstipation or worsening of headache symptoms) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study design and key findings. Of 632 screened patients, 78 met the inclusion criteria. Initial treatment with BoNTA led to treatment failure in most cases due to inefficacy and one due to poor tolerability, while initial treatment with erenumab showed in 14 cases inefficacy, in four cases poor tolerability and in six cases both reasons to discharge. Patients then received either erenumab or BoNTA as a subsequent treatment. A very good response was observed in 17.9% (18.5% with erenumab, 16.7% with BoNTA), while 76% remained non-responders. (The figure was created in BioRender)

When using a ≥ 30% reduction in MHDs as the definition for good response, the overall findings remained largely unchanged. An additional four patients responded to erenumab and one more to BoNTA.

We observed a statistically significant association between MOH and the responder groups: MOH was more frequently observed among insufficient responders compared to both responder groups (p = 0.04; Table 1). There were no other statistically significant differences between good responders and insufficient responders in terms of demographics, migraine features, and comorbidities.

Table 1.

Demographic and characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | Total cohort | Insufficient response (75.6%) | Very good response (17.9%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 78 | n = 59 | Erenumab n = 10/54 |

BoNTA n = 4/24 |

||

| Female sex | 66 (84.6%) | 50 (84.7%) | 9 (90.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 0.66 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 43.2 (14.0) | 42.87 (14.76) | 46.22 (9.4) | 38.98 (11.2) | 0.51 |

| Migraine with aura | 27 (34.6%) | 20 (33.9%) | 6 (60.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.29 |

| Smoking | 14 (17.9%) | 10 (16.9%) | 2 (20.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.68 |

| Depression | 39 (50.0%) | 31 (52.5%) | 6 (60.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.54 |

| Anxiety | 17 (21.8%) | 13 (22.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 0.41 |

| Hypertension | 10 (12.8%) | 7 (11.9%) | 1 (10.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | 0.99 |

| Medication overuse headache | 39 (50.0%) | 32 (54.2%) | 3 (30.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.04* |

| Daily headache | 22 (28.2%) | 16 (27.1%) | 3 (30.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 0.81 |

| Monthly headache days, median (IQR) | |||||

| Baseline | 20 (13) | 20 (12.5) | 21 (11.25) | 23 (10.75) | 0.84 |

| Last month of initial treatment | 17.0 (16) | 20 (15.5) | 13.5 (9.25) | 21.5 (14.25) | 0.29 |

| Third month of subsequent treatment | 13 (21) | 24 (17) | 4 (1.5) | 4.5 (3.25) | > 0.005 |

A very good response was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction in monthly headache days (MHD), while an insufficient response was defined as a < 30% reduction, 3 months after switching treatment to either BoNTA or erenumab. Values are presented as number (%), mean (standard deviation, SD), or median (interquartile range, IQR), as appropriate. MHDs are reported for three time points: baseline (before initial treatment), the last month of the initial treatment, and the third month of the subsequent treatment

BoNTA onabotulinumtoxinA, IQR interquartile range, SD standard deviation, MHD monthly headache days

*Statistically significant

Both the BoNTA-to-erenumab and erenumab-to-BoNTA responder groups demonstrated a reduction in MHD during the first treatment phase, although the improvement did not reach the 50% threshold for clinical response.

Discussion

In this retrospective real-world study, approximately one in five patients with chronic migraine experienced a ≥ 50% reduction in MHD in response to subsequent treatment with BoNTA and erenumab. A slightly higher proportion benefited from switching to erenumab after BoNTA than from the reverse sequence. Our results suggest that switching may be useful in some patients, particularly in those who demonstrate a partial response to the initial treatment. The better response after switching may reflect the distinct mechanisms of action,BoNTA targeting SNARE-mediated release from C-fibers and erenumab blocking CGRP receptors on Aδ fibers,despite both ultimately acting on the CGRP pathway [6, 9].

However, natural fluctuations in headache frequency and placebo-related effects may also contribute to the observed improvements. Migraine is characterized by significant within-person variability and frequent transitions between chronic and episodic patterns and switching treatments itself can elicit expectation-driven effects [18, 19].

The observed responder rate aligns with prior studies on switching between CGRP mAbs, where clinical benefit was reported in roughly one-third of patients. However, these studies also noted a decline in effectiveness with each additional treatment [14, 20–22]. Similarly, Talbot et al. [23] found benefit when switching from BoNTA to erenumab, although their analysis excluded patients who discontinued because of adverse effects.

Importantly, the majority of patients (82%) did not experience a reduction of ≥ 50% of MHDs following the second treatment. The modest response rate observed in our study may reflect the complex and heterogeneous nature of chronic migraine. While the exclusion of patients with extensive treatment histories likely reduced confounding from severe treatment resistance, many included patients had daily headaches and psychiatric comorbidities that potentially reduce treatment responsiveness.

In our study, MOH was more common among individuals with an insufficient treatment response, suggesting that medication overuse may contribute to treatment resistance. Traditionally, MOH has been associated with reduced efficacy of preventive treatments. However, several recent real-world studies have shown that CGRP mAbs can be effective in patients with MOH, and can lead to a reduction of acute medication use without requiring prior detoxification [24–26]. Some data even suggest that treatment response to CGRP mAbs may be comparable, or in some cases higher, in patients with MOH than in those without, possibly due to higher baseline burden and a greater margin for improvement [24].

Additionally, the results might indicate that in these individuals, migraine may be driven by mechanisms beyond the CGRP pathway, such as alternative neuropeptides like PACAP or central sensitization processes. Given the peripheral mode of action of both BoNTA and CGRP mAbs, one potential future direction may involve targeting the central nervous system more effectively. Gepants are small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists capable of crossing the blood–brain barrier and may offer an alternative for patients unresponsive to peripherally acting therapies [27].

The real-world design of our study reflects routine clinical practice. By focusing on sequential use and clearly defining response criteria, the study provides practical insights into treatment decisions in patients with difficult-to-treat chronic migraine. To minimize confounding from treatment resistance, we excluded patients with more than three prior prophylactic therapies and those previously treated with other CGRP mAbs.

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. The retrospective design limits causal inference, as treatment decisions and documentation were not standardized or controlled prospectively. The use of MHD instead of the more specific monthly migraine days (MMD) was necessitated by the limitations of patient-recorded calendars, which often did not clearly distinguish migraine attacks. This may lead to incomplete or inconsistent data and limit the ability to determine direct cause-and-effect relationships between treatment switches and observed outcomes. The duration of sequential treatment used for outcome measurement was relatively short at 3 months, chosen to ensure better data quality; a longer observation period may have yielded different results. The absence of a control group restricts interpretation regarding placebo effects or natural disease fluctuations. Additionally, the intervals between initial and subsequent treatments were not standardized, introducing the possibility of carryover effects. The relatively small sample size, especially in the erenumab-to-BoNTA group, reduces statistical power and increases the margin of error, limiting the ability to detect smaller treatment effects or make strong subgroup comparisons. Moreover, patients included in the study were those treated at a tertiary headache center, and many presented specifically for advanced therapies such as CGRP mAbs or BoNTA. This may reflect a population with complex migraine profiles and limits the generalizability of our findings to the broader chronic migraine population.

Conclusion

In this retrospective real-world study, one-fifth of the patients with chronic migraine experienced a ≥ 50% reduction in MHD after switching between BoNTA and erenumab following failure of the initial treatment. While both therapies target the CGRP pathway, their distinct mechanisms of action may explain the observed benefit in a subset of patients. These preliminary findings support considering treatment switching in clinical practice and highlight the need for prospective studies to identify predictors of response and guide personalized preventive strategies in migraine care.

Acknowledgements

Dr. med. Kristin Sophie Lange and PD Dr. med. Bianca Raffaelli are participants in the BIH Charité Clinician Scientist Program. Dr. med. Mira Pauline Fitzek is a participant in the BIH Charité Junior Clinician Scientist Program.

Author Contributions

Bianca Raffaelli supervised the overall study and conceptualized its design. Carolin Luisa Hoehne led the data analysis and drafted the figure, table and the initial manuscript. Aysenur Sahin was primarily responsible for data collection. Bianca Raffaelli, Carolin Luisa Hoehne, Aysenur Sahin, Lucas Hendrik Overeem, Kristin Sophie Lange, Mira Pauline Fitzek, Cornelius Angerhöfer and Uwe Reuter contributed to data interpretation and validation, had full access to all study data, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final version for submission and revision.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or the publication of this article. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Carolin Luisa Hoehne, Aysenur Sahin, Lucas Hendrik Overeem and Cornelius Angehöfer have nothing to declare. Kristin Sophie Lange reports a research grant (International Headache Society) and personal fees (Teva, Organon). Mira Pauline Fitzek reports personal fees from Novartis and Teva. Uwe Reuter has no personal fees to report. Institutional fees from Amgen, Abbvie, Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, Pfizer, Medscape, Sand Teva, and research funding from Novartis. Bianca Raffaelli reports research grants from Novartis, Lundbeck, German Migraine and Headache Society (DMKG), German Research Foundation (DFG) and Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung, and personal fees from Abbvie, Lundbeck, Novartis, Organon, Perfood and Teva.

Ethical Approval

The retrospective data analysis of clinical routine data of headache patients has been approved by the Charité Ethical Committee (EA1/159/22). No specific ethical approval or written informed consent for participation was required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements, and followed Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for cohort studies [17].

References

- 1.Ashina M. Migraine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1866–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2021 Nervous System Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 2024;23:344–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ornello R, Caponnetto V, Ahmed F, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of migraine, summary version. Cephalalgia. 2025;45:03331024251321500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aurora S, Dodick D, Turkel C, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 1 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendtsen L, Sacco S, Ashina M, et al. Guideline on the use of onabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine: a consensus statement from the European Headache Federation. J Headache Pain. 2018;19:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burstein R, Blumenfeld AM, Silberstein SD, et al. Mechanism of action of onabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine: a narrative review. Headache J Head Face Pain. 2020;60:1259–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Strassman AM, Novack V, et al. Extracranial injections of botulinum neurotoxin type A inhibit intracranial meningeal nociceptors’ responses to stimulation of TRPV1 and TRPA1 channels: are we getting closer to solving this puzzle? Cephalalgia. 2016;36:875–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sacco S, Amin FM, Ashina M, et al. European Headache Federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene related peptide pathway for migraine prevention – 2022 update. J Headache Pain. 2022;23:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eftekhari S, Warfvinge K, Blixt FW, et al. Differentiation of nerve fibers storing CGRP and CGRP receptors in the peripheral trigeminovascular system. J Pain. 2013;14:1289–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaimes A, Gómez A, Pajares O, et al. Dual therapy with Erenumab and onabotulinumtoxinA: no synergistic effect in chronic migraine: a retrospective cohort study. Pain Pract. 2023;23:349–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scuteri D, Tonin P, Nicotera P, et al. Pooled analysis of real-world evidence supports anti-CGRP mAbs and onabotulinumtoxinA combined trial in chronic migraine. Toxins. 2022;14:529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raffaelli B, Kalantzis R, Mecklenburg J, et al. Erenumab in chronic migraine patients who previously failed five first-line oral prophylactics and onabotulinumtoxinA: a dual-center retrospective observational study. Front Neurol. 2020;11:417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pensato U, Baraldi C, Favoni V, et al. Real-life assessment of erenumab in refractory chronic migraine with medication overuse headache. Neurol Sci. 2022;43:1273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong JB, Israel-Willner H, Peikert A, et al. Therapeutic patterns and migraine disease burden in switchers of CGRP-targeted monoclonal antibodies – insights from the German NeuroTransData registry. J Headache Pain. 2024;25:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puledda F, Sacco S, Diener H-C, et al. International Headache Society global practice recommendations for preventive pharmacological treatment of migraine. Cephalalgia. 2024;44:03331024241269735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elm EV, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335:806–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt K, Berding T, Kleine-Borgmann J, et al. The beneficial effect of positive treatment expectations on pharmacological migraine prophylaxis. Pain. 2022;163:e319–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serrano D, Lipton RB, Scher AI, et al. Fluctuations in episodic and chronic migraine status over the course of 1 year: implications for diagnosis, treatment and clinical trial design. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iannone LF, Burgalassi A, Vigani G, et al. Switching anti-CGRP(R) monoclonal antibodies in multi-assessed non-responder patients and implications for ineffectiveness criteria: a retrospective cohort study. Cephalalgia. 2023;43:03331024231160519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overeem LH, Lange KS, Fitzek MP, et al. Effect of switching to erenumab in non-responders to a CGRP ligand antibody treatment in migraine: a real-world cohort study. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1154420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Triller P, Blessing VN, Overeem LH, et al. Efficacy of eptinezumab in non-responders to subcutaneous monoclonal antibodies against CGRP and the CGRP receptor: a retrospective cohort study. Cephalalgia. 2024;44:03331024241288875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talbot J, Stuckey R, Crawford L, et al. Improvements in pain, medication use and quality of life in onabotulinumtoxinA-resistant chronic migraine patients following erenumab treatment – real world outcomes. J Headache Pain. 2021;22:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheffler A, Basten J, Menzel L, et al. Persistent effectiveness of CGRP antibody therapy in migraine and comorbid medication overuse or medication overuse headache—a retrospective real-world analysis. J Headache Pain. 2024;25:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pensato U, Baraldi C, Favoni V, et al. Detoxification vs non-detoxification before starting an anti-CGRP monoclonal antibody in medication overuse headache. Cephalalgia. 2022;42:645–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliveira R, Gil-Gouveia R, Puledda F. CGRP-targeted medication in chronic migraine-systematic review. J Headache Pain. 2024;25:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Versijpt J, Paemeleire K, Reuter U, et al. Calcitonin gene-related peptide-targeted therapy in migraine: current role and future perspectives. Lancet. 2025;405:1014–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.