Abstract

Combining a computer-based screening strategy and functional genomics, we previously identified MRP9 (ABCC12), a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily. We now show that the gene has two major transcripts of 4.5 and 1.3 kb. In breast cancer, normal breast, and testis, the MRP9 gene transcript is 4.5 kb in size and encodes a 100-kDa protein. The protein is predicted to have 8 instead of 12 membrane-spanning regions. When compared with closely related ABC family members, it lacks transmembrane domains 3, 4, 11, and 12 and the second nucleotide-binding domain. In other tissues including brain, skeletal muscle, and ovary, the transcript size is 1.3 kb. This smaller transcript encodes a nucleotide-binding protein of ≈25 kDa in size. An in situ hybridization study shows that the 4.5-kb transcript is expressed in the epithelial cells of breast cancer. An antipeptide antibody designed to react with the amino terminus of the protein detects a 100-kDa protein in testis and the membrane fraction of a breast cancer cell line. Because the 4.5-kb RNA is highly expressed in breast cancer and not expressed at detectable levels in essential normal tissues, MRP9 could be a useful target for the immunotherapy of breast cancer. Because of the unusual topology of the two variants of MRP9, we speculate that they may have a different function from other family members.

Completion of the human genome project and advances in bioinformatics have enabled researchers to identify and analyze new genes that could be used as targets for cancer therapy or could be involved in the multistep process of cancer. Many different methods now are used to identify tissue- or cancer-specific genes. Over the past several years our laboratory has identified genes expressed in prostate cancer and normal prostate by using the expressed sequence tag (EST) database (1, 2). In this approach a computer-based screening strategy is used to generate clusters of ESTs that are expressed specifically in normal prostate and/or prostate cancer but not in essential normal tissues (3). Several new prostate-specific genes have been identified by this approach (4–8). With the publication of the draft sequence of the human genome we have been able, in most cases, to identify the gene encoding each EST cluster and determine whether the protein has the characteristics of a membrane protein. Our laboratory is focused on the development of immunotoxin for the therapy of cancer (9). For this therapy and other antibody-based therapies to be effective, it is essential that the target antigen be a membrane-associated protein located on the cell surface. Using this approach, we recently reported the identification of MRP8 (ABCC11), a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily, which is highly expressed in breast cancer (10) and of MRP9 (ABCC12). In this report, we have analyzed the RNA transcripts and protein produced by MRP9. The MRP9 gene is unusual because it encodes two transcripts of different sizes. The larger 4.5-kb RNA is found in breast cancer, normal breast, and testis and encodes an MRP-like protein that lacks transmembrane domains 3, 4, 11, and 12 and the second nucleotide-binding domain. The smaller 1.3-kb RNA is detected in brain, skeletal muscle, and ovary and seems to encode the second nucleotide-binding domain.

Materials and Methods

EST Database Mining and Computer Analysis.

The methods used for database analysis of ESTs and the alignment of the individual EST with the genomic sequence was described earlier (3, 10).

RNA Dot Blots and Northern Blot Hybridization.

RNA hybridization was performed on multiple-tissue Northern blots (CLONTECH) and a human multiple-tissue expression array (CLONTECH, catalog no. 7775-1) containing mRNA from 76 human tissues in separate dots as described earlier (10). The 400-bp PCR fragment generated by primers T385 and T386 was used as a 3′-specific probe. The 600-bp (nucleotides 1–600) DNA fragment was used as a 5′-specific probe. The sequences of the primers used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used in this study

| Primer name | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| T385 | GCA TTC TCA GCT TGG AAG ACC TCA |

| T386 | CTT CTC TGC AAG GAC TTC AGG CTT |

| T396 | AGC ACC AGC TCA TCC AGA CTG AAT |

| T399 | TGA GTG CAT TCA GGA ACA CAG GTC |

| T412 | CCA CAG AGG AGT CCA GGA GCT CAA |

| T413 | TGG CAA GAA GGA GAG CTG CAT CAC |

| T414 | TGT GGC CTT GTT GGT GAC CCT GAG |

| T415 | GAC GCA AGC CAA ATT CAC CTC CGT |

| T418 | GGA GAG CTG CAT CAC CTA TCA CCT |

| T419 | GGA GAG CTG CAT CAC CTA GTT TAA |

Reverse Transcription (RT)-PCR Analysis on a Gene-Expression Panel.

A rapid-scan gene-expression panel containing PCR-ready first-strand cDNA from 24 different tissues (OriGene, Rockville, MD, catalog no. HSCA-101) was used as a template for PCR with a primer pair (T385 and T386) that should give a 400-bp fragment. For expression analysis of MRP8 in normal breast and breast cancer, we used a human breast cancer rapid-scan panel (OriGene catalog no. TSCE-101) that contains PCR-ready first-strand cDNA from 12 normal and 12 breast cancer tissues. PCR composition and conditions used were according to the supplier's instructions.

Cloning of the Full-Length cDNA.

Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) was performed on Marathon Ready brain and testis cDNA (CLONTECH). Gene-specific primers T385 and T386 were used for the 3′ and 5′ RACE, respectively. The PCR product was gel-purified and cloned into the pCR2.1 TOPO vector (Invitrogen). The longest clones were identified by restriction digestion and sequenced by using a rhodamine terminator sequencing kit (Perkin–Elmer Applied Systems, Warrington, U.K.).

Antibody Production and Purification of IgG from Antisera.

A peptide of 14 aa (amino acids 15–28) was synthesized, conjugated with keyhole limpet hemocyanin, and injected into rabbits with complete Freund' s adjuvant for the first immunization and incomplete Freund's adjuvant for subsequent immunizations. Sera were collected after the fourth and fifth immunizations and analyzed by ELISA against the synthesized peptide. Total IgG was purified with immobilized protein A (Pierce) following the supplier's instructions.

Western Blot Analysis.

Approximately 40 μg of protein extract from different tissues (Protein Medley, CLONTECH) or the 100,000 × g pellet of a homogenate of the CRL1500 breast cancer cell line were separated on a 10% Tris-glycine gel (Bio-Rad) and transferred to a 0.2-μm Immun-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad) in transfer buffer [25 mM Tris/192 mM glycine/0% (vol/vol) methanol, pH 8.3] at 4°C for 2 h at 50 V. Filters were probed with 10 μg/ml protein A-purified anti-MRP9 antiserum or preimmune serum, and their respective signals were detected by using a chemiluminescence Western blotting kit according to instructions from Roche Molecular Biochemicals as described (11).

In Situ Hybridization.

Pretreatment of the tissue sections for in situ hybridization was performed as described (8). Biotinylated cDNA probes were prepared by using a 600-bp fragment from the 5′ end of MRP9 and full-length U6 (a small nuclear RNA known to be expressed in almost all cells) cloned in pBluescript II SK(+) plasmid. Biotinylated pBluescript II SK(+) with a CD22 insert was used as a negative control. Probe labeling, hybridization, and washing conditions were similar to those described previously (8). Microscopic evaluation (bright-field) was performed by using a Nikon Eclipse 800 microscope (12).

In Vitro Transcription-Coupled Translation.

The in vitro translation of the 4.5-kb variant of MRP9 cDNA from testis was examined in an in vitro transcription-coupled translation system (TNT, Promega). [35S]Met (ICN) was incorporated in the reaction for visualization of translated products. The reaction mixture was analyzed under reducing conditions on a polyacrylamide gel (7.5% Tris/glycine, Bio-Rad) together with a prestained marker (Bio-Rad) and autoradiographed.

Results

Identification of MRP9 (ABCC12).

We recently reported (8) that MRP8, a member of the ABC transporter superfamily, is located in a genomic region of over 80.4 kb on chromosome 16q12.1. Using the GENESCAN gene prediction program (13) we identified an adjacent gene with homology to MRP8 and named it MRP9 (10). When the predicted cDNA of MRP9 was analyzed to identify SAGE tags by using the SAGE map database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SAGE/), the sequence matches up with five tags; four are from breast cancer, and one is from pancreatic cancer, indicating that MRP9 may be expressed commonly in breast cancer (data not shown).

Experimental Analysis of MRP9 Transcripts.

To determine the tissue specificity of MRP9 expression, we performed a multitissue dot blot analysis by using a PCR-generated DNA fragment from the 3′ end of the predicted MRP9 gene (Fig. 1B). PCR primers T385 and T386 were designed from the predicted cDNA sequence, and a PCR product of the expected size was amplified, cloned, and sequenced from testis cDNA. The DNA fragment was labeled with 32P by random priming and used for dot blot hybridization. As shown in Fig. 2A, among the 76 different samples of normal and fetal tissues examined MRP9 is detected in different parts of the brain (1A–1G, A2, D2, F2, and B3), testis (F8), and pancreas (B9).

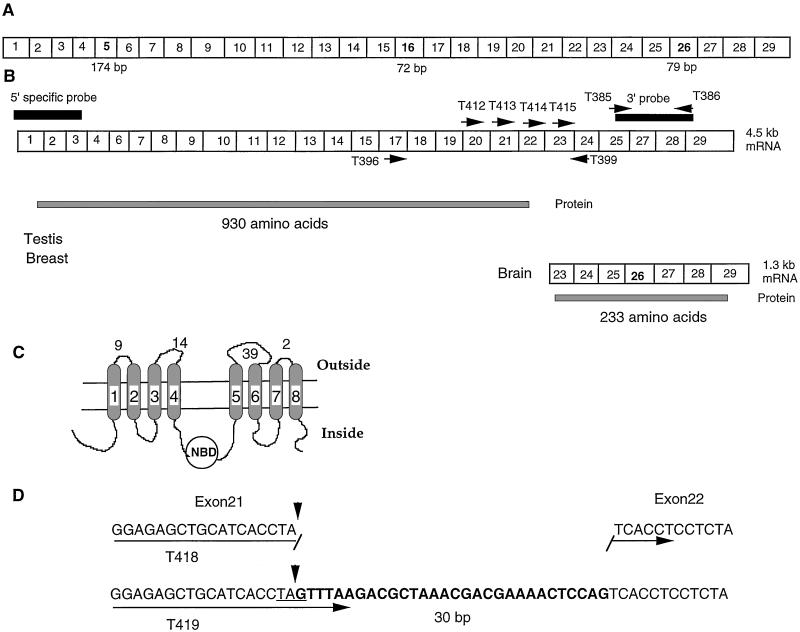

Figure 1.

Schematic of the MRP9 cDNA and its variants. (A) Schematics of MRP9 cDNA as described by Tammur et al. (14) (B) Variants of MRP9 transcript and predicted ORFs. The 4.5-kb transcript has 26 exons, and the ORF starts at exon 1 and ends at exon 21. The 1.8-kb transcript has seven exons and has the ORF of 233 aa. The name and location of the PCR primers used are shown by arrows, and the location of the probes is shown by black rectangles. (C) Schematics showing the probable topology of the MRP9-translated protein. Eight possible membrane-spanning regions are numbered, and the number of amino acids exposed to the outside of the cells is mentioned. (D) Design and sequence of the PCR primer used in Fig. 4.

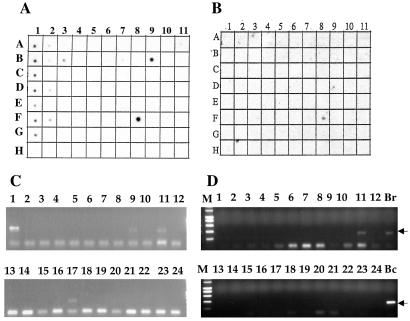

Figure 2.

Tissue distribution of MRP9 mRNA expression. (A) RNA hybridization of a multiple-tissue dot blot containing mRNA from 50 normal human cell types or tissues using a cDNA probe from the 3′ end of the MRP9 transcript. Signal is detected in testis (F8), pancreas (B9), and different parts of brain (A1, whole brain; B1, cerebral cortex; C1, frontal lobe; D1 parietal lobe; E1 occipital lobe; F1, temporal lobe; G1, paracentral gyrus cerebral cortex; A2, left cerebellum; B2, right cerebellum; D2 amygdala; and F2, hippocampus). There is a weak signal observed in the liver (A9), prostate (E8), and placenta (B8). (B) RNA hybridization of the same blot used in A with a 5′-specific probe. Specific signal is detected only in testis (F8). (C) PCR using 3′-specific primers on cDNA from 24 different human tissues (rapid-scan panel, OriGene); the expected size of the MRP9 PCR product is 400 bp. Lanes: 1, brain; 2, heart; 3, kidney; 4, spleen; 5, liver; 6, colon; 7, lung; 8, small intestine; 9, muscle; 10, stomach; 11, testis; 12, placenta; 13, salivary gland; 14, thyroid gland; 15, adrenal gland; 16, pancreas; 17, ovary; 18, uterus; 19, prostate; 20, skin; 21, peripheral blood leukocytes; 22, bone marrow; 23, fetal brain; and 24, fetal liver. (D) PCR using 5′-specific primer pair on cDNA from 24 different human tissues. The expected size of the MRP9 PCR product is 400 bp (shown by an arrow). The PCR product is detected in testis (lane 11), normal breast (lane Br), and breast cancer cell lines (lane Bc).

To confirm the dot blot result we used a more sensitive PCR-based analysis to validate tissue-specific expression of MRP9. In this analysis we used a panel of cDNAs isolated from 24 different normal tissues and performed PCRs with a primer pair (T385 and T386) located at the 3′ end of the MRP9 (Fig. 1). (The same primer pair was used to generate a probe for the dot blot analysis designed from the 3′-DNA sequence of MRP9.) As shown in Fig. 2C, a specific band of 400 bp is detected in normal brain (lane 1), testis (lane 11), ovary (lane 17), and skeletal muscle (lane 9). There also is a weak but detectable signal in pancreas (lane 16).

Analysis of MRP9 Transcript in Different Tissues.

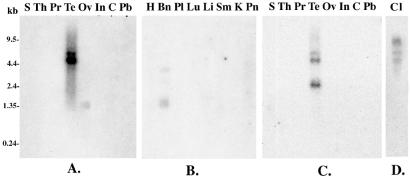

To determine the transcript size of the MRP9 mRNA, we performed an analysis of a Northern blot containing mRNAs from different tissues. The PCR-generated probe from the 3′ end of MRP9 (Fig. 1B) was used for this analysis. As shown in Fig. 3A, a specific band of 4.5 kb in size is detected in testis. In contrast, a small band ≈1.3 kb in size was detected in brain and ovary (Fig. 3 A and B), suggesting that different variants of the MRP9 transcript are expressed in different tissues.

Figure 3.

Northern blot analysis showing expression and transcript sizes of MRP9 in different normal tissues. Radiolabeled DNA probes from the 3′ (for A and B) and 5′ (C and D) ends of the MRP9 cDNA used for hybridization. S, spleen; Th, thymus; Pr, prostate; Te, testis; Ov, ovary; In, small intestine; C, colon; Pb, peripheral blood leukocyte; H, heart; Bn, brain; Pl, placenta; Lu, lung; Li, liver; Sm, skeletal muscle; K, kidney; Pn, pancreas; and Cl, CRL1500.

Full-Length cDNA Cloning of MRP9.

To isolate the 4.5-kb cDNA for MRP9 we used conventional cDNA library screening as well as the 5′ and 3′ RACE-PCR method and isolated a clone of 4.5 kb in size from testis cDNA. The MRP9 gene has 26 exons. Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of the cDNA reveals that it has an ORF of 930 aa and is made up of 20 exons. It lacks membrane-spanning regions 3, 4, 11, and 12 and the second nucleotide-binding domain normally present in a typical ABC C-type transporter (Fig. 1C).

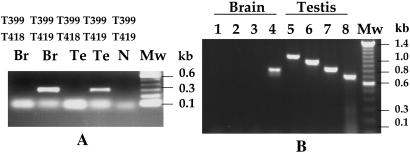

A recent report by Tammur et al. (14) concluded that the MRP9 gene is transcribed as a 5-kb transcript that encodes a 1,359-aa ORF that is expressed in testis, prostate, and ovary. As shown in Fig. 1A, the MRP9 gene described by Tammur et al. has 29 exons (GenBank accession no. AY040220). However, the cDNA we isolated from testis has an ORF of only 930 aa. The major differences between the Tammur et al. sequence and our cDNA sequence are we do not detect exons 5, 16, and 26, and also we do detect an extra 30-bp sequence at the 5′ end of exon 22 (Fig. 1B). As a result, a stop codon TAG is present in our cDNA sequence, producing an ORF encoding a protein containing 930 aa. To verify this observation we PCR-cloned this region of the cDNA (Fig. 1B) by using the primer pair T396 and T399 from testis and normal breast cDNA and sequenced nine clones. Every clone contained the 30-bp extra sequence at the 5′ end of exon 22. To determine whether the variant, which does not contain the extra 30-bp sequence, can be detected in various tissues, we used a sensitive PCR-based analysis. We designed 5′ primers specific for each variant (T419 for the variant that contains the 30-bp extra sequence and T418 for the possible variant that does not contain the extra 30 bp; Fig. 1D). We used the same 3′ primer T399 for PCR amplification by using PCR-ready cDNAs from testis and breast. As shown in Fig. 4A (lanes 2 and 4), a specific 300-bp PCR product is detected only when primers T419 and T399 were used. No detectable PCR product was observed when primers T418 and T399 were used. This result shows that in both testis and breast the expressed MRP9 transcript contains the extra 30-bp sequence at the 5′ end of the exon 22. Because the cDNAs used in this experiment are generated from pooled tissues from more than nine individuals, the presence of the extra 30-bp sequence represents a common splicing event and is not a rare event. In addition, there is deletion of 58, and 24 aa at positions 218 (exon 5) and 679 (exon 16), respectively, as compared with the Tammur et al. sequence (Fig. 1A). The 58-aa deletion at position 218 causes deletion of the third and fourth membrane-spanning regions normally present in a typical ABCC family transporter.

Figure 4.

PCR analysis of the MRP9 variant in different tissues. (A) RT-PCR analysis of testis and breast RNA using either the T416/T399 or T417/T399 primer pair. Lanes 1 (T417/T399) and 2 (T416/T399), breast; lanes 3 (T417/T399) and 4 (T416/T399), testis. Lane 5 is negative control. MW, molecular weight standard. (B) RT-PCR analysis of brain and testis RNA with T412, T413, T414, and T415 as the 5′ primer and T386 as the 3′ primer. Lanes 1–4 are for primers T412, T413, T414, and T415, respectively, for brain; lanes 5–8 are for primers T412, T413, T414, and T415, respectively, for testis.

Analysis of the MRP9 Transcript in Brain.

The dot blot and rapid-scan PCR analysis shown in Fig. 2 indicates that MRP9 is highly expressed in brain. The northern analysis in Fig. 3A shows that the transcript size of MRP9 in brain is ≈1.3 kb, which is much smaller than the RNA detected in testis and breast cancer. To analyze the 1.3-kb transcript in brain, we used RACE-PCR with the T385 primer for 3′ RACE and the T386 primer for 5′ RACE (Fig. 1B). Marathon-Ready cDNA from brain was used as a template. The 5′-RACE reaction gave a DNA fragment of 850 bp, and the product from the 3′ RACE was ≈1.1 kb in size. Both the 5′- and 3′-RACE products were subsequently cloned in a TA cloning vector and sequenced. Results from the 3′-RACE analysis indicate that the sequence of the 3′ end of the 1.3-kb transcript in brain is exactly the same as the 3′ end of the 4.5-kb clone that we isolated from testis. All clones from brain generated by 5′ RACE started within exon 23, which indicates that the 1.3-kb transcript originates within exon 23. In addition, nine independent clones generated from brain RNA contain 79-bp exon 26 (Fig. 1B). The cDNA, which contains exon 26, has an ORF of 234 aa and encodes a nucleotide-binding domain that is missing in the protein encoded by the 4.5-kb variant of MRP9. To confirm the RACE-PCR analysis and rule out the possibility that we did not detect the 5′ end of the brain-specific transcript because of a limitation of the RACE reaction on a GC-rich template, we performed a PCR analysis on brain and testis cDNA by using several 5′ primers (T412, T413, T414, and T415, Fig. 4A) and T386 as 3′ primer (Fig. 1B). As shown in Fig. 4B, the expected sized PCR product was obtained with all four 5′ primers with testis cDNA, whereas with brain cDNA, only the T415 primer (which is within exon 23) gave a PCR product of 800 bp in size. Consistent with our RACE-PCR analysis, the major PCR product for brain cDNA with the T415 and T386 primer pair contains 79-bp exon 26. There is a very weak band of ≈700 bp in size, which probably accounts for the transcript without exon 26 (Fig. 4B, lane 4).

Long Transcript of MRP9 Is Expressed Specifically in Testis and Breast.

To determine whether the long form of MRP9 is expressed specifically in certain tissues, we performed a multitissue dot blot and rapid-scan analysis with a 5′-specific probe and a 5′-specific primer pair, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2B, among the 76 different samples of normal and fetal tissues tested in the dot blot, MRP9 was detected only in testis. In the rapid-scan analysis shown in Fig. 2D, a specific band of 400 bp is detected in testis (lane 11), normal breast (lane Br), and breast cancer cDNA prepared from a pool of four breast cancer cell lines (lane Bc) but not in 23 other tissues tested including heart, brain, and lung. Subsequent analysis with breast cancer cell line RNA showed expression of MRP9 in CRL1500 cells but not in three other breast cancer cell lines examined. When the 5′-specific probe was used in the multitissue Northern blot, a band of 4.5 kb in size was detected in testis and the breast cancer cell line CRL1500 (Fig. 3C). There is also a 2.4-kb band in testis, which could be a splice variant of the gene. No band was detected in any other tissues tested, which include ovary and brain (data not shown).

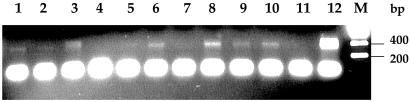

Expression of MRP9 in Breast Cancer.

To investigate whether MRP9 is expressed in different samples of normal breast and primary breast cancers, an RT-PCR analysis was carried out by using a human breast cancer rapid-scan panel, which contains cDNAs from 12 different normal breast and breast cancer specimens. As shown in Fig. 5, using the PCR primer T385 and T386, the expected 400-bp PCR product was detected in 9 of 12 breast cancer samples. The signal was not detected in normal breast, although it was detected in one sample of normal breast RNA obtained from CLONTECH (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Rapid-scan PCR analysis using a 3′-specific primer pair on cDNAs from 12 different breast cancer specimens (lanes 1–12). M, molecular weight marker.

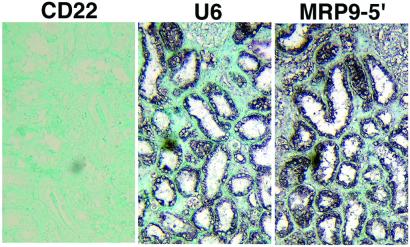

MRP9 mRNA Is Expressed in the Epithelial Cells of Breast Cancer.

To determine whether the longer 4.5-kb variant of MRP9 mRNA is expressed in epithelial cells of a breast cancer specimen from patients, we used in situ hybridization with a biotin-labeled 5′-specific MRP9 cDNA (nucleotides 1–604). MRP9 mRNA is expressed only in the epithelial cells (Fig. 6). A representative example of a strong signal over the breast cancer cells demonstrates no detectable signal in cells of the stromal compartment of the tissue.

Figure 6.

In situ localization of MRP9 mRNA. Shown are breast cancer tissue sections stained with CD22 and U6 probe used as a negative control (CD22) and positive control (U6), respectively. A serial section of the same cancer tissue stained with a 5′-specific MRP9 probe (MRP9-5′) also is shown. Note the strong signal in the tumor cells.

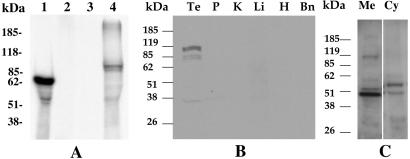

In Vitro Transcription and Translation of the MRP9 cDNA.

The MRP9 cDNA has a predicted ORF of 930 aa with a calculated molecular mass of 95 kDa. To determine the size of the protein encoded by the MRP9 cDNA, in vitro transcription and translation was performed by using the rabbit reticulocyte lysate system. SDS/PAGE analysis and fluorography of the translated product showed a doublet of ≈100 kDa in size (Fig. 7A), perhaps because of a different amount of glycosylation. The size of the protein products agrees with the predicted ORF of the cDNA.

Figure 7.

Analysis of the protein product encoded by the 4.5-kb variant of MRP9. (A) Analysis of the in vitro translated products of MRP9 cDNA. The 4.5-kb variant of MRP9 cDNA was transcribed in vitro with T7 RNA polymerase and couple-translated with rabbit reticulocyte lysate in the presence of [35S]methionine. The translated products were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and fluorography. Lane 1, luciferase cDNA as positive control; lane 2, no DNA; lane 3, MRP9 cDNA in antisense orientation; and lane 4, MRP9 cDNA in sense orientation. (B and C) Western blot analysis of anti-MRP9 peptide antisera. A specific protein with a molecular mass of ≈100 kDa is detected by anti-MRP9 IgG in testis (Te) tissue extract and in membrane (Me) fraction of the CRL1500 extract (C). The tissue extract from brain (Bn), heart (H), liver (Li), kidney (K), prostate (P), and the cytoplasmic (Cy) fraction of CRL1500 showed no detectable signal.

The MRP9 Transcript Encodes a 100-kDa Membrane Protein.

To identify the protein expressed by the MRP9 gene, we developed polyclonal antibodies in rabbits against a synthetic peptide (amino acids 15–28) of MRP9. By using a purified IgG fraction of the antisera, a doublet band at a molecular mass of ≈100 kDa, was detected in testis but not in brain, heart, liver, kidney, or prostate samples (Fig. 7B). A similar band was detected in the total membrane fraction prepared from the CRL1500 breast cancer cell line (Fig. 7C, lane Me). We did not detect any specific bands with IgG prepared from the preimmune serum (data not shown).

Discussion

We have used a functional genomic approach and bioinformatics tools to identify MRP9 (ABCC12), a member of the ABC transporter superfamily. Our experimental data show that the MRP9 transcript is expressed as different variants in different tissues. The larger 4.5-kb transcript is highly expressed in breast cancer and testis and weakly expressed in normal breast. It encodes a protein of ≈100 kDa molecular mass. The smaller 1.3-kb transcript is expressed in brain, skeletal muscle, and ovary. The smaller transcript has an ORF of 234 aa.

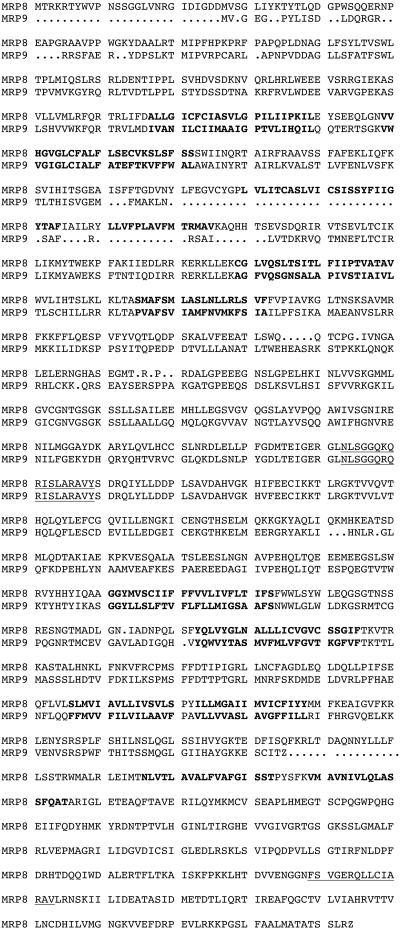

MRP9 Is a Unique Member of the ABCC Family.

The multidrug resistance (MDR)/ABC superfamily of membrane transporters is one of the largest protein families and is involved in energy-dependent transport of a variety of substrates across the membrane including drugs used to treat cancer (15–17). In humans this superfamily is divided further into seven subfamilies (ABC-A to -G) based primarily on sequence similarity. Most ABC proteins from eukaryotes encode full transporters, consisting of two ATP-binding domains and 12 membrane-spanning regions or half transporters, which are presumed to dimerize (16, 18). We described earlier that the sequence of MRP8, which is related closely to MRP5, belongs to the ABCC subfamily. MRP8, similar to other members of the subfamily, is a full transporter with two nucleotide-binding and 12 transmembrane-spanning regions. The MRP9 sequence, similar to that of MRP8, is related closely to MRP5 (19), with an overall 44% identity and 55% sequence similarity at the protein level. Between MRP8 and MRP9, the overall sequence identity and similarity is 47 and 56%, respectively. One major difference between MRP8 and MRP9 is that MRP9 has only one ATP-binding domain but two transmembrane domains each with four membrane-spanning regions. A few so-called half-transporters with one ATP-binding domain and six membrane-spanning regions have been reported and characterized (20–22). The two half-transporter molecules normally are transcribed separately, translated, and then probably assembled together to generate a full transporter. However, in the case of MRP9, a premature stop codon truncates the protein and generates an unusual protein without the second ATP-binding domain and containing only four membrane-spanning regions in the carboxyl half of the protein. In addition, the 58-aa deletion within the amino-terminal half of MRP9 causes deletion of the third and fourth membrane-spanning regions of the molecule (Fig. 8). The importance of the loss of four membrane-spanning regions and one nucleotide-binding domain is unknown because MRP9 lies adjacent to MRP8, and it probably arose by gene duplication and then underwent further mutational changes to carry a new and different function.

Figure 8.

Amino acid sequence alignment of MRP8 and MRP9. Membrane-spanning regions of the transmembrane domain are shown in bold letters, and the conserved ABC signature motifs for both MRP8 and MRP9 are underlined.

The Smaller 1.3-kb MRP9 Transcript Is Caused by an Alternate Transcription Start Site.

Different sized mRNAs of the ABCC family members often are observed during Northern analysis. In most cases, different sized mRNAs arise because of alternate splicing of the major transcript. In the case of MRP9, the Northern analysis using a 3′ probe (Fig. 3A) shows that in brain and ovary the transcript is ≈1.3 kb, whereas the transcript detected in testis is ≈4.5 kb. When the 5′-specific probe was used in Northern analysis (Fig. 3B), only the 4.5-kb transcript of testis was detected, indicating that both the 5′ and 3′ probes are recognizing the same transcript. The 5′ probe does not recognize the 1.3-kb transcript of MRP9 from either ovary or brain. RACE-PCR cloning of the full-length 1.3-kb variant of MRP9 from brain and RT-PCR analysis also suggest that the 1.3-kb variant is transcribed independently and not caused by an alternate splicing event. This 1.3-kb transcript has an ORF of 234 aa and encodes one of the ATP-binding domains of the transporter molecule. It will be interesting to determine whether the protein encoded by this transcript is expressed in the tissue by generating specific antibody against the ORF. Also, its biological function is unknown.

The MRP9 Variant Is a Potential Candidate for Immunotherapy.

Both RT-PCR analysis by a 5′-specific primer pair and the Northern blot and in situ analysis using a 5′-specific probe indicate that the larger 4.5-kb MRP9 transcript is expressed selectively in breast cancer, normal breast, and testis. However, the 1.3-kb transcript is very nonspecific. Recently Yabuuchi et al. (23) reported multiple splice variants of MRP9 (ABCC12) in various adult tissues including brain, lung, liver, kidney, pancreas, and colon. The transcripts were detected by PCR with primers from the 3′ end of the gene. Our results indicate that the 1.3-kb variant of MRP9 is expressed in several adult tissues and likely represents the transcript that Yabuuchi et al. detected. The longer 4.5-kb transcript is expressed specifically in breast cancer, normal breast, and testis. Our in situ RNA analysis (unpublished data) confirms the RT-PCR results and confirms that many cancer specimens are positive for MRP9 expression. Because MRP9 is a membrane protein and it has very restricted expression in essential tissues, it is a potential target for targeted therapy with antibodies, antibody conjugates, and immunotoxins.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Gene Discovery Group for their valuable comments during this study, Dr. Kristi Egland for providing the RNA samples from the breast cancer cell lines, Dr. Michael Gottesman and Ms. Maria Gallo for reading the manuscript, Ms. Verity Fogg for cell culture assistance, and Ms. Anna Mazzuca for editorial assistance.

Abbreviations

- EST

expressed sequence tag

- RT

reverse transcription

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- RACE

rapid amplification of cDNA ends

References

- 1.Okubo K, Matsubara K. FEBS Lett. 1997;40:225–229. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke J, Wang H, Hide W, Davison D B. Genome Res. 1998;8:276–290. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasmatzis G, Essand M, Brinkmann U, Lee B, Pastan I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:300–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinkmann U, Vasmatzis G, Lee B, Yerushalmi N, Essand M, Pastan I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10757–10762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkmann U, Vasmatzis G, Lee B, Pastan I. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1445–1448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Essand M, Vasmatzis G, Brinkmann U, Duray P, Lee B, Pastan I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9287–9292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bera T K, Maitra R, Iavarone C, Salvatore G, Kumar V, Vincent J J, Sathyanarayana B K, Duray P, Lee B K, Pastan I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3058–3063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052713699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsson P, Bera T K, Essand M, Kumar V, Duray P, Vincent J, Lee B K, Pastan I. Prostate. 2001;48:231–241. doi: 10.1002/pros.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreitman R J, Wilson W H, Bergeron K, Raggio M, Stetler-Stevenson M, FitzGerald D J, Pastan I. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:241–247. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107263450402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bera T K, Lee S, Salvatore G, Lee B, Pastan I. Mol Med. 2001;7:509–516. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfgang C D, Essand M, Vincent J J, Lee B, Pastan I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9437–9442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160270597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar V, Collins F H. Insect Mol Biol. 1994;3:41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.1994.tb00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeh R-F, Lim L P, Burge C B. Genome Res. 2001;11:803–816. doi: 10.1101/gr.175701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tammur J, Prades C, Arnould I, Rzhetsky A, Hutchinson A, Adachi M, Schuetz J D, Swoboda K J, Ptacek L J, Rosier M, et al. Gene. 2001;273:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein I, Sarkadi B, Varadi A. Biochim Biophys Acta–Biomembranes. 1999;1461:237–262. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borst P, Evers R, Kool M, Wijnholds J. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1295–1302. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottesman M M, Fojo T, Bates S E. Nature (London) 2002;2:48–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allikmets R, Gerrard B, Hutchinson A, Dean M. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1649–1655. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.10.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McAleer M A, Breen M A, White N L, Matthews N. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23541–23548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyake K, Mickley L, Litman T, Zhan Z R, Robey R, Cristensen B, Brangi M, Greenberger L, Dean M, Fojo T, et al. Cancer Res. 1999;59:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robey R W, Medina-Perez W Y, Nishiyama K, Lahusen T, Miyake K, Litman T, Senderowicz A M, Ross D D, Bates S E. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly A, Powis S H, Kerr L A, Mockridge I, Elliott T, Bastin J, Uchanskaziegler B, Ziegler A, Trowsdale J, Townsend A. Nature (London) 1992;355:641–644. doi: 10.1038/355641a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yabuuchi H, Shimizu H, Takayanagi S, Ishikawa T. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:933–939. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]