Abstract

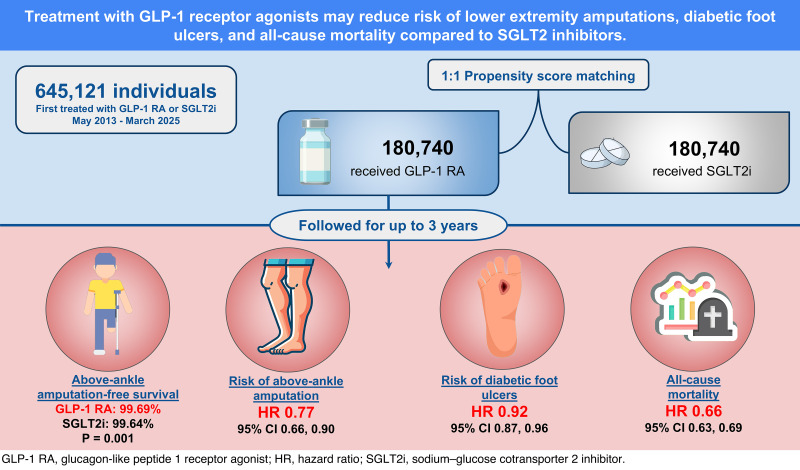

OBJECTIVE

To compare the risk of lower-extremity amputations (LEAs) between new users of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) versus sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2is).

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

This retrospective cohort study used TriNetX, a federated electronic health records network, including adults with type 2 diabetes who initiated GLP-1RAs or SGLT2is between May 2013 and March 2025. Propensity score matching (1:1) was used to balance demographics, comorbidities, medications, and laboratory values. Major (above-ankle) amputation–free survival was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier curves, while risks of major and minor LEAs, diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), and mortality were estimated using hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs.

RESULTS

The matched cohorts included 180,740 GLP-1RA and 180,740 SGLT2i recipients. At 3 years, the GLP-1RA cohort was associated with greater major amputation–free survival (99.69% vs. 99.64%, P = 0.001) compared with the SGLT2i cohort. Additionally, GLP-1RA treatment was associated with a lower risk of major LEAs (HR 0.77 [95% CI 0.66, 0.90]), minor LEAs (HR 0.73 [95% CI 0.63, 0.84]), DFUs (HR 0.92 [95% CI 0.87, 0.96]), and mortality (HR 0.66 [95% CI 0.63, 0.69]). Risk reduction for major LEAs remained significant in individuals with peripheral artery disease (HR 0.68 [95% CI 0.56, 0.82]) and DFUs (HR 0.70 [95% CI 0.58, 0.84]).

CONCLUSIONS

GLP-1RA treatment was associated with greater major amputation–free survival compared with SGLT2i in people with type 2 diabetes, particularly in high-risk subgroups. Prospective studies are needed to confirm findings and inform selection of glucose-lowering therapies for people at risk for diabetes-related amputations.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Diabetes, particularly type 2 diabetes, is a leading cause of lower-extremity amputations (LEAs) worldwide (1,2). People with diabetes experience significantly higher rates of LEAs compared with the general population and face an increased risk of mortality, long-term disability, and reduced quality of life following amputation (3,4). Critically, diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) precede ∼85% of all nontraumatic LEAs, emphasizing their pivotal role in diabetes-related limb loss (5). The economic burden of diabetes and its complications is substantial, with costs projected to exceed $412 billion annually in the U.S., including an estimated $4 billion specifically attributed to LEAs (6,7).

The introduction of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) has revolutionized diabetes management, offering significant cardiovascular, renal, and mortality benefits beyond glycemic control (8). However, the impact of GLP-1RAs and SGLT2is on lower-limb complications, including DFUs and LEAs, remains uncertain. Concerns surrounding SGLT2is surfaced after a landmark randomized controlled trial (RCT) on canagliflozin reported an increased risk of LEAs compared with placebo (9). Since then, studies have yielded conflicting findings. While cardiovascular outcome trials and other RCTs have shown noninferiority of SGLT2is compared with GLP-1RAs for lower-limb outcomes, some observational studies suggested an elevated LEA risk due to SGLT2i use (10–12). A 2021 meta-analysis of 764 RCTs comparing GLP-1RAs and SGLT2is found no definitive evidence linking either drug class to increased LEA risk. However, the analysis primarily focused on cardiovascular and renal end points, which limited the conclusions regarding lower-limb outcomes (13).

Despite these advances, significant gaps remain. Many real-world studies on lower-limb outcomes are hampered by heterogeneity in patient populations, treatment crossover, and limited follow-up, potentially obscuring the true effects of these therapies. This study leverages a large, nationally representative cohort of people with type 2 diabetes to evaluate the associations among GLP-1RAs, SGLT2is, and diabetes-related lower-limb complications, including DFUs and LEAs. We hypothesized that GLP-1RAs and SGLT2is would have differential effects on the risk of LEA. Stratified analyses by peripheral artery disease (PAD) and DFU status were conducted to address critical gaps and inform therapeutic decisions in high-risk populations with type 2 diabetes.

Research Design and Methods

Data Source

This retrospective cohort study used the U.S. Collaborative Network within the TriNetX analytics platform, a federated health research network aggregating deidentified electronic health record (EHR) data from >118 million patients across 70 U.S. health care organizations, including both academic and nonacademic centers, with their satellite sites encompassing both insured and uninsured populations (14). The study was deemed exempt by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board (HS-24-00606), and informed consent was waived due to the use of deidentified data. The study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines (15).

Study Population

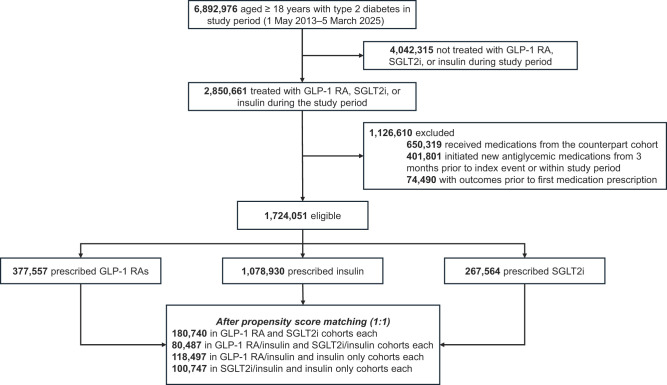

Cohort selection is detailed in Fig. 1. Participants aged ≥18 years with type 2 diabetes were identified using ICD-10 code E11. The initial analysis was performed in January 2025 and updated in March 2025, covering a study period from 1 May 2013 to 5 March 2025, as the first SGLT2i received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in March of 2013. The index event was defined as the first prescription of a GLP-1RA, an SGLT2i, or insulin therapy. Eligible patients were categorized into five cohorts: 1) GLP-1RA only, 2) SGLT2i only, 3) GLP-1RA with insulin, 4) SGLT2i with insulin, and 5) insulin only. Switching within the same drug class (e.g., between different GLP-1RAs or SGLT2is) was permitted. To ensure independent assessment of new prescriptions, patients were required to have initiated GLP-1RA, SGLT2i, or insulin therapy without any new prescriptions for other oral glucose-lowering medications (e.g., dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, biguanides, α-glucosidase inhibitors, thiazolidinediones, or sulfonylureas) within 3 months before or 3 years after the index prescription. Patients were excluded if they had experienced any outcome of interest before the index date. The lookback period was set to anytime within the TriNetX platform to ensure comprehensive capture of covariates. Participants were followed from the index date (initial prescription) until the earliest occurrence of the following: 1) outcome event, 2) death, 3) loss to follow-up, or 4) 3 years postindex date. A full list of related ICD-10 codes is included in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 1.

Study cohort flow diagram.

Propensity Score Matching

Propensity score matching was conducted to balance potential confounders by adjusting for clinical variables and risk factors for LEAs. Four matched cohorts were created to assess the effects of GLP-1RAs relative to SGLT2is and their combinations with insulin therapy: 1) GLP-1RA only versus SGLT2i only, 2) GLP-1RA with insulin versus SGLT2i with insulin, 3) GLP-1RA with insulin versus insulin only, and 4) SGLT2i with insulin versus insulin only. Covariates included age, sex, race and ethnicity (as documented in the EHR), cardiovascular diseases, coronary grafts, chronic kidney disease, PAD, dementia, chronic lower respiratory disease, diabetic angiopathy, diabetic neuropathy, liver cirrhosis, socioeconomic and psychosocial health hazards, tobacco use, nicotine dependence, insulin, other hypoglycemic agents, lipid-lowering agents, antihypertensives, antithrombotic agents, antiarrhythmic agents, BMI, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), total cholesterol, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), triglycerides, prior revascularization procedures, and health care utilization (outpatient, inpatient, and emergency department visits). The most recent laboratory values prior to the index prescription and the proportion of patients with available values were used to match cohorts on both measured values and missingness. Detailed codes for these variables are available in Supplementary Table 2.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was major amputation (above the ankle)–free survival. Secondary outcomes included any LEAs, minor LEAs (i.e., toe[s], foot), DFUs, and mortality. Outcomes were evaluated at 1-year and 3-year intervals following the index prescription.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the built-in functions of the TriNetX platform. Baseline characteristics were summarized as means (SDs) for continuous variables and frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. Propensity scores were estimated using logistic regression on user-defined covariates. Matching was performed using 1:1 greedy nearest neighbor matching on the propensity score with a caliper distance of 0.1 pooled SDs of the logit. Patient record order was randomized to minimize selection bias introduced by the nearest neighbor matching process. Balance between matched groups was assessed using standardized mean differences (SMDs), with an SMD <0.1 indicating acceptable balance. Kaplan-Meier analysis was conducted to estimate survival probabilities after matching, with log-rank tests used to estimate differences in survival between cohorts. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs for all outcomes. In addition, cumulative incidence rates were calculated at 1 and 3 years for all outcomes (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). The proportional hazards assumption was assessed using scaled Schoenfeld residuals within the R survival package version 3.2-3. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P < 0.05.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analysis

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were conducted to strengthen the reliability of our findings and address potential confounders. First, a negative control analysis assessed residual confounding. Second, we analyzed two high-risk patient cohorts for LEA: one with PAD on enrollment and another with DFU on enrollment for whom prior DFU was not an exclusion criterion. Third, we stratified cohorts by age (<65 vs. ≥65 years), race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-White Hispanic, and Black or African American), and sex. To account for historical prescribing differences, we limited the analysis to individuals initiating therapy after 1 January 2018. Additionally, to refine type 2 diabetes diagnosis, we applied a stricter definition requiring either an HbA1c ≥6.5% or fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL in addition to ICD-10 code E11 for cohort inclusion (16). To ensure sustained medication use, we required a second prescription within 6 months after the first. Finally, given evidence of an enhanced protective effect of GLP-1RA in people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, we conducted a subgroup analysis in this population (17).

Data and Resource Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study were obtained from TriNetX, LLC, and are subject to third-party restrictions. These data were accessed under license for this study and cannot be redistributed or made publicly available. However, access may be requested of the TriNetX research network by contacting TriNetX (https://live.trinetx.com). Access may require licensing fees, a formal data sharing agreement, and adherence to privacy regulations, ensuring that no identifiable patient information is disclosed.

Results

Associations Between GLP-1RA Only or SGLT2i Only and Lower-Extremity Outcomes

The GLP-1RA–only cohort included 377,557 patients (mean [SD] age 57.2 [13.4] years, 58.7% female, and 61.7% White, 20% Black, and 9% Hispanic), while the SGLT2i-only cohort included 267,564 patients (mean [SD] age 65.5 [12.2] years, 39.0% female, and 59.9% White, 19% Black, and 9% Hispanic). The propensity score–matched groups consisted of 180,740 patients each, with all covariates well balanced except for BMI (mean [SD]: GLP-1RA 34.6 [7.9] vs. SGLT2i 33.1 [7.5] kg/m2, SMD 0.191) (Table 1). A total of 93.1% of patients in the GLP-1RA cohort and 92.2% in the SGLT2i were followed for ≥3 years. The GLP-1RA cohort was followed for a mean (SD) 581 (395) days compared with 550 (405) days for the SGLT2i cohort.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of GLP-1RA and SGLT2i cohorts before and after propensity score matching

| Before matching, n (%) | After matching, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1RA (n = 377,557) | SGLT2i (n = 267,564) | SMD | GLP-1RA (n = 180,740) | SGLT2i (n = 180,740) | SMD | |

| Age at index, mean (SD) (years) | 57.2 (13.4) | 65.5 (12.2) | 0.650 | 62.6 (11.6) | 62.6 (12.2) | 0.001 |

| Female sex | 221,689 (58.7) | 104,400 (39.0) | 0.402 | 81,693 (45.2) | 82,527 (45.7) | 0.009 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| African American or Black | 75,226 (19.9) | 51,191 (19.1) | 0.020 | 33,938 (18.8) | 34,369 (19.0) | 0.006 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1,606 (0.4) | 971 (0.4) | 0.010 | 734 (0.4) | 708 (0.4) | 0.002 |

| Asian | 11,324 (3.0) | 15,440 (5.8) | 0.136 | 7,812 (4.3) | 7,934 (4.4) | 0.003 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 2,839 (0.8) | 2,119 (0.8) | 0.005 | 1,419 (0.8) | 1,378 (0.8) | 0.003 |

| White | 232,947 (61.7) | 160,202 (59.9) | 0.037 | 110,093 (60.9) | 109,915 (60.8) | 0.002 |

| Other race | 16,642 (4.4) | 11,248 (4.2) | 0.010 | 7,974 (4.4) | 8,017 (4.4) | 0.001 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 34,610 (9.2) | 23,221 (8.7) | 0.017 | 16,546 (9.2) | 16,464 (9.1) | 0.002 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 263,950 (69.9) | 193,276 (72.2) | 0.051 | 12,6570 (70.0) | 127,422 (70.5) | 0.010 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertensive disease | 258,965 (68.6) | 21,3424 (79.8) | 0.257 | 134,094 (74.2) | 134,192 (74.2) | 0.001 |

| Atherosclerosis | 21,411 (5.7) | 32,694 (12.2) | 0.231 | 15,162 (8.4) | 15,201 (8.4) | 0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 54,561 (14.5) | 76,273 (28.5) | 0.347 | 37,519 (20.8) | 37,888 (21.0) | 0.005 |

| End-stage renal disease | 8,801 (2.3) | 5,290 (2.0) | 0.024 | 4,160 (2.3) | 4,027 (2.2) | 0.005 |

| Chronic lower respiratory disease | 100,274 (26.6) | 75,321 (28.2) | 0.036 | 45,397 (25.1) | 45,466 (25.2) | 0.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 72,198 (19.1) | 115,858 (43.3) | 0.541 | 53,908 (29.8) | 53,956 (29.9) | 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 34,283 (9.1) | 91,282 (34.1) | 0.639 | 31,392 (17.4) | 31,975 (17.7) | 0.008 |

| Atrial fibrillation and flutter | 26,087 (6.9) | 56,055 (21.0) | 0.414 | 20,983 (11.6) | 21,297 (11.8) | 0.005 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 35,034 (9.3) | 48,517 (18.1) | 0.260 | 23,797 (13.2) | 24,009 (13.3) | 0.003 |

| Fibrosis and cirrhosis of liver | 9,307 (2.5) | 9,115 (3.4) | 0.056 | 5,425 (3.0) | 5,289 (2.9) | 0.004 |

| Other and unspecified cirrhosis of liver | 7,558 (2.0) | 8,185 (3.1) | 0.067 | 4,731 (2.6) | 4,633 (2.6) | 0.003 |

| Neoplasm | 128,476 (34.0) | 91,993 (34.4) | 0.007 | 59,989 (33.2) | 60,157 (33.3) | 0.002 |

| Aortic aneurysm and dissection | 5,278 (1.4) | 10,329 (3.9) | 0.154 | 4,137 (2.3) | 4,118 (2.3) | 0.001 |

| Other aneurysm | 2,739 (0.7) | 4,230 (1.6) | 0.080 | 1,877 (1.0) | 1,923 (1.1) | 0.002 |

| Arterial embolism and thrombosis | 2,307 (0.6) | 3,635 (1.4) | 0.076 | 1,629 (0.9) | 1,636 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Other peripheral vascular diseases | 21,973 (5.8) | 30,314 (11.3) | 0.198 | 14,661 (8.1) | 14,892 (8.2) | 0.005 |

| Other disorders of arteries and arterioles | 13,792 (3.7) | 20,896 (7.8) | 0.180 | 9,480 (5.2) | 9,492 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes with diabetic peripheral angiopathy without gangrene | 12,766 (3.4) | 19,220 (7.2) | 0.171 | 9,075 (5.0) | 9,214 (5.1) | 0.004 |

| Type 2 diabetes with diabetic peripheral angiopathy with gangrene | 1,971 (0.5) | 2,927 (1.1) | 0.064 | 1,430 (0.8) | 1,433 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes with diabetic polyneuropathy | 39,811 (10.5) | 32,712 (12.2) | 0.053 | 21,901 (12.1) | 21,759 (12.0) | 0.002 |

| Presence of coronary angioplasty implant and graft | 12,313 (3.3) | 28,730 (10.7) | 0.296 | 10,516 (5.8) | 10,683 (5.9) | 0.004 |

| Presence of aortocoronary bypass graft | 9,574 (2.5) | 24,276 (9.1) | 0.282 | 8,458 (4.7) | 8,688 (4.8) | 0.006 |

| Socioeconomic and psychosocial health hazards | 20,080 (5.3) | 15,372 (5.7) | 0.019 | 8,898 (4.9) | 9,008 (5.0) | 0.003 |

| Tobacco use | 21,977 (5.8) | 20,720 (7.7) | 0.077 | 11,630 (6.4) | 11,698 (6.5) | 0.002 |

| Nicotine dependence | 56,056 (14.8) | 49,871 (18.6) | 0.102 | 2,9109 (16.1) | 29,094 (16.1) | <0.001 |

| Personal history of nicotine dependence | 58,320 (15.4) | 62,464 (23.3) | 0.201 | 32,737 (18.1) | 33,109 (18.3) | 0.005 |

| Unspecified dementia | 3,015 (0.8) | 6,021 (2.3) | 0.119 | 2,407 (1.3) | 2,455 (1.4) | 0.002 |

| Procedure | ||||||

| Venous grafting only for coronary artery bypass | 248 (0.1) | 670 (0.3) | 0.047 | 219 (0.1) | 234 (0.1) | 0.002 |

| Combined arterial-venous grafting for coronary bypass | 2,168 (0.6) | 5,386 (2.0) | 0.128 | 1,956 (1.1) | 2,012 (1.1) | 0.003 |

| Arterial grafting for coronary artery bypass | 2,427 (0.6) | 5,859 (2.2) | 0.131 | 2,162 (1.2) | 2,204 (1.2) | 0.002 |

| Endovascular repair procedures of the abdominal aorta and/or iliac arteries | 199 (0.1) | 651 (0.2) | 0.050 | 176 (0.1) | 199 (0.1) | 0.004 |

| Endovascular revascularization (open or percutaneous, transcatheter) | 2,274 (0.6) | 3,991 (1.5) | 0.087 | 1,740 (1.0) | 1,807 (1.0) | 0.004 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Insulin and analogs | 153,705 (40.7) | 132,010 (49.3) | 0.174 | 81,504 (45.1) | 81,087 (44.9) | 0.005 |

| Biguanides | 228,799 (60.6) | 149,469 (55.9) | 0.096 | 108,309 (59.9) | 108,174 (59.9) | 0.002 |

| Sulfonylureas | 83,684 (22.2) | 70,362 (26.3) | 0.097 | 48,536 (26.9) | 48,285 (26.7) | 0.003 |

| α-Glucosidase inhibitors | 1,153 (0.3) | 898 (0.3) | 0.005 | 608 (0.3) | 613 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 19,254 (5.1) | 15,243 (5.7) | 0.026 | 11,171 (6.2) | 11,003 (6.1) | 0.004 |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors | 51,854 (13.7) | 46,935 (17.5) | 0.105 | 31,887 (17.6) | 31,789 (17.6) | 0.001 |

| Diuretics | 171,784 (45.5) | 153,756 (57.5) | 0.241 | 89,763 (49.7) | 89,899 (49.7) | 0.002 |

| β-Blocking agents | 158,324 (41.9) | 159,489 (59.6) | 0.359 | 89,885 (49.7) | 90,124 (49.9) | 0.003 |

| ACE inhibitors | 144,429 (38.3) | 122,429 (45.8) | 0.152 | 78,052 (43.2) | 77,682 (43.0) | 0.004 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 103,081 (27.3) | 99,696 (37.3) | 0.214 | 57,540 (31.8) | 57,423 (31.8) | 0.001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 118,492 (31.4) | 115,742 (43.3) | 0.247 | 67,654 (37.4) | 67,807 (37.5) | 0.002 |

| Lipid-modifying agents | 230,534 (61.1) | 198,943 (74.4) | 0.287 | 126,190 (69.8) | 125,716 (69.6) | 0.006 |

| Antithrombotic agents | 182,464 (48.3) | 178,305 (66.6) | 0.377 | 103,269 (57.1) | 103,278 (57.1) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory values, mean (SD) | ||||||

| HbA1c (%) | 7.6 (2.0) | 7.6 (1.9) | 0.006 | 7.8 (2.0) | 7.8 (1.9) | 0.041 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 37.1 (8.2) | 31.7 (7.4) | 0.697 | 34.6 (7.9) | 33.1 (7.5) | 0.191 |

| GFR (predicted) (mL/min/m2) | 79.5 (28.2) | 70.6 (28.2) | 0.316 | 73.7 (27.6) | 74.3 (28.5) | 0.022 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 171.8 (46.6) | 157.6 (48.3) | 0.300 | 164.9 (47.0) | 163.1 (49.0) | 0.038 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 172.6 (142.4) | 161.8 (147.9) | 0.075 | 171.0 (132.4) | 173.5 (164.5) | 0.017 |

| Health care utilization | ||||||

| Ambulatory visit | 336,655 (89.2) | 234,781 (87.7) | 0.044 | 157,241 (87.0) | 157,688 (87.2) | 0.007 |

| Inpatient encounter | 128,236 (34.0) | 126,861 (47.4) | 0.276 | 68,442 (37.9) | 69,098 (38.2) | 0.007 |

| Emergency visit | 165,443 (43.8) | 123,130 (46.0) | 0.044 | 76,330 (42.2) | 76,671 (42.4) | 0.004 |

At 1 year, the GLP-1RA cohort had 160 major amputations (99.89% survival) compared with 266 in the SGLT2i cohort (99.81% survival). At 3 years, the GLP-1RA cohort had 291 major amputations (99.69% survival) compared with 353 in the SGLT2i cohort (99.64% survival) (P = 0.001) (Fig. 2). At the 1-year follow-up, the GLP-1RA cohort demonstrated significantly lower risks for major amputation (HR 0.57 [95% CI 0.47, 0.70]), minor amputation (HR 0.73 [95% CI 0.63, 0.84]), any amputation (HR 0.66 [95% CI 0.58, 0.75]), new DFU (HR 0.92 [95% CI 0.87, 0.96]), and mortality (HR 0.66 [95% CI 0.63, 0.69]) compared with the SGLT2i group (Supplementary Fig. 1). At 3-year follow-up, the GLP-1RA group continued to show lower risks for major amputation (HR 0.77 [95% CI 0.66, 0.90]), minor amputation (HR 0.89 [95% CI 0.80, 1.00]), any amputation (HR 0.83 [95% CI 0.76, 0.92]), DFU (HR 0.95 [95% CI 0.92, 0.99]), and mortality (HR 0.83 [95% CI 0.81, 0.86]) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

Major amputation–free survival at 3 years. A: Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of major amputation–free survival among patients receiving GLP-1RA vs. SGLT2is in a 3-year follow-up. B and C: Separate analyses were conducted for patients with prior PAD or DFU.

Associations Among GLP-1RA and Insulin, SGLT2i and Insulin, and Insulin-Only Therapy and Lower-Extremity Outcomes

There were 1,078,930 patients who received insulin-only therapy, 146,096 prescribed a GLP-1RA and insulin, and 123,936 prescribed an SGLT2i and insulin. After matching, the GLP-1RA and insulin versus SGLT2i and insulin comparison included 80,487 patients (mean [SD] age 63 [12] years, 45.5% female, and 60% White, 21% Black, 8% Hispanic) in each cohort and were well matched except for BMI (Supplementary Table 5). For the GLP-1RA and insulin versus insulin-only comparison, each matched cohort included 118,497 patients (mean [SD] age 59 [14] years, 54% female, and 60% White, 21% Black, 9% Hispanic), with the GLP-1RA and insulin group showing higher HbA1c, BMI, and GFR compared with the insulin-only cohort (Supplementary Table 6). In the SGLT2i and insulin versus insulin-only comparison, each matched cohort included 100,747 patients (mean [SD] age 66 [12] years, 40% female, and 61% White, 20% Black, 8% Hispanic), with the SGLT2i and insulin group showing higher HbA1c and GFR after matching (Supplementary Table 7). A total of 95.1% of patients in the GLP-1RA and insulin cohort, 96.0% in the SGLT2i and insulin cohort, and 82.0% in the insulin-only cohort had follow-up data beyond 3 years. Mean (SD) follow-up duration was 620 (398) days for the GLP-1RA and insulin group, 570 (402) days for the SGLT2i and insulin group, and 679 (433) days for the insulin-only group.

At the 1-year follow-up, the GLP-1RA and insulin group demonstrated significantly lower risks for major amputation (HR 0.64 [95% CI 0.51, 0.79]), minor amputation (HR 0.67 [95% CI 0.57, 0.79]), any amputation (HR 0.65 [95% CI 0.56, 0.75]), DFU (HR 0.92 [95% CI 0.86, 0.98]), and mortality (HR 0.67 [95% CI 0.64, 0.71]) compared with the SGLT2i and insulin group (Supplementary Fig. 2). At the 3-year follow-up, the GLP-1RA and insulin group continued to show lower risks for major amputation (HR 0.69 [95% CI 0.59, 0.81]), minor amputation (HR 0.85 [95% CI 0.76, 0.96]), any amputation (HR 0.80 [95% CI 0.73, 0.89]), DFU (HR 0.93 [95% CI 0.89, 0.98]), and mortality (HR 0.82 [95% CI 0.79, 0.85]) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of major amputation and mortality at 3 years. Patients were followed up for as long as 3 years after the index event for both groups. HRs with 95% CIs were calculated using a Cox proportional hazards model with censoring applied. For each outcome, the groups were propensity score matched for covariates related to the outcome, and the outcome was compared between the matched groups. Each eligible individual was followed up from the index event until the occurrence of the outcomes, death, loss to follow-up, or 3 years after the index event, whichever occurred first.

At the 1-year follow-up, the GLP-1RA and insulin group demonstrated significantly lower risks for major amputation (HR 0.40 [95% CI 0.33, 0.49]), minor amputation (HR 0.49 [95% CI 0.42, 0.56]), any amputation (HR 0.45 [95% CI 0.40, 0.51]), DFU (HR 0.73 [95% CI 0.69, 0.77]), and mortality (HR 0.27 [95% CI 0.26, 0.29]) compared with the insulin-only group (Supplementary Fig. 3). At the 3-year follow-up, the GLP-1RA and insulin group continued to show significantly lower risks for major amputation (HR 0.56 [95% CI 0.48, 0.65]), minor amputation (HR 0.71 [95% CI 0.64, 0.79]), any amputation (HR 0.65 [95% CI 0.59, 0.71]), DFU (HR 0.85 [95% CI 0.82, 0.88]), and mortality (HR 0.40 [95% CI 0.38, 0.41]) compared with the insulin-only group (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3).

At the 1-year follow-up, the SGLT2i and insulin group demonstrated significantly lower risks for major amputation (HR 0.65 [95% CI 0.55, 0.77]), minor amputation (HR 0.79 [95% CI 0.69, 0.91]), any amputation (HR 0.72 [95% CI 0.65, 0.81]), DFU (HR 0.87 [95% CI 0.82, 0.91]), and mortality (HR 0.46 [95% CI 0.44, 0.47]) compared with the insulin-only group (Supplementary Fig. 4). At the 3-year follow-up, the SGLT2i and insulin group had lower risks for major amputation (HR 0.75 [95% CI 0.65, 0.86]), minor amputation (HR 0.85 [95% CI 0.77, 0.95]), any amputation (HR 0.81 [95% CI 0.74, 0.88]), DFU (HR 0.91 [95% CI 0.88, 0.95]), and mortality (HR 0.52 [95% CI 0.51, 0.53]) compared with the insulin-only group (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

Among individuals with PAD at enrollment, the 3-year follow-up of matched cohorts showed a major amputation free–survival of 99.18% (n = 180) in those taking GLP-1RAs compared with 98.88% in those taking SGLT2is (n = 245) (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). GLP-1RA use was associated with lower risks for major amputation (HR 0.68 [95% CI 0.56, 0.82]), minor amputation (HR 0.76 [95% CI 0.65, 0.89]), any amputation (HR 0.73 [95% CI 0.64, 0.83]), DFU (HR 0.91 [95% CI 0.85, 0.97]), and mortality (HR 0.81 [95% CI 0.77, 0.85]) compared with SGLT2i use (Supplementary Fig. 5). Among those with DFUs at enrollment, the 3-year follow-up showed a major amputation free–survival of 98.51% (n = 186) among those taking GLP-1RAs compared with 97.89% (n = 241) in those taking SGLT2is (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). GLP-1RA use was associated with lower risks for major amputation (HR 0.70 [95% CI 0.58, 0.84]), minor amputation (HR 0.76 [95% CI 0.66, 0.87]), any amputation (HR 0.72 [95% CI 0.64, 0.82]), and mortality (HR 0.80 [95% CI 0.75, 0.85]) compared with SGLT2i use (Supplementary Fig. 6). Furthermore, the lower major amputation risk with GLP-1RAs versus SGLT2is remained consistent across demographic subgroups, except in non-White Hispanic patients, who showed a nonsignificant negative trend (HR 0.52 [95% CI 0.25, 1.10]) (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Our sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of our findings. Restricting the index prescription date to 1 January 2018 and applying a stricter type 2 diabetes definition consistently confirmed our results (Supplementary Table 8). To assess the impact of prescription patterns, we required an additional prescription within 6 months after initiation and observed consistent findings. Among individuals with peripheral neuropathy, the reduction in major amputation risk (HR 0.68 [95% CI 0.56, 0.83]) was more pronounced compared with the overall cohort. Negative control analyses found no significant associations between GLP-1RA or SGLT2i use and appendicitis, traumatic tooth fracture, or basal cell carcinoma (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Conclusions

This large, real-world study compared the effects of GLP-1RAs and SGLT2is, alone and in combination with insulin, on lower-extremity outcomes and mortality in people with type 2 diabetes. Key findings demonstrated that GLP-1RA use was associated with a lower risk of amputations, DFUs, and mortality compared with SGLT2i therapy, with findings persisting through 3-year follow-up periods. Importantly, GLP-1RA and SGLT2i use demonstrated a decreased risk of DFUs, underscoring their safety profile for limb-related outcomes. Additionally, in subgroup analyses of individuals with PAD or DFUs, GLP-1RA therapy demonstrated lower risks of LEAs and mortality compared with SGLT2i therapy, highlighting its potential benefit for high-risk populations.

Prior studies have demonstrated that GLP-1RAs and SGLT2i therapies reduce cardiovascular and renal complications in people with type 2 diabetes (13,18). However, their comparative effects on LEA outcomes, particularly in high-risk cohorts, remain underexplored. While previous studies have linked SGLT2i therapy to elevated LEA risk, a 2023 meta-analysis on 13 studies noted an increased tendency of LEA risk with SGLT2i use (11,19). In contrast, GLP-1RA therapies have not been associated with increased LEA risks and may provide amputation protection, as demonstrated in the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results (LEADER) trial, which showed that liraglutide significantly reduced DFU-related amputation risk (HR 0.65 [95% CI 0.45, 0.95]) (20). Observational studies in both Taiwan and Italy reported decreased lower-limb complications in GLP-1RA users compared with SGLT2i users (17,21). Our findings are consistent with these results, showing that GLP-1RA therapy significantly reduced the risk of both minor and major amputations compared with SGLT2i therapy. Notably, when combined with insulin, GLP-1RAs continued to show significant reductions in amputation risks and mortality compared with both SGLT2i and insulin-only therapy. This is particularly important given the widespread use of insulin in diabetes management, which may not always provide sufficient glycemic control without adjuvant therapies, thus leading to higher risks of DFUs and amputations (22). The ability of GLP-1RAs to mitigate these risks further supports its role in limb preservation.

We also observed a reduced incidence of DFUs with GLP-1RA therapy, consistent with prior studies (23). While SGLT2i and DFU risk findings have been mixed, our analysis suggests a protective effect, possibly due to improved glycemic control, weight loss, and reduced microvascular complications (24,25). However, SGLT2i therapy, though beneficial for cardiovascular and renal outcomes, has been implicated in adverse limb outcomes. The Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study (CANVAS) trial reported a nearly twofold increased amputation risk with canagliflozin (HR 1.97 [95% CI 1.41, 2.75]), and subsequent pharmacovigilance analyses have identified potential amputation signals not only for canagliflozin but also for dapagliflozin and empagliflozin based on disproportionality analyses of adverse event case reports (9,26). Proposed mechanisms include dehydration, altered blood flow, and increased susceptibility to infections, all of which could impair wound healing (27).

Subgroup analyses showed that the reduced risk of major LEAs and DFUs with GLP-1RA use was consistent across age, sex, and racial and ethnic groups. However, Hispanic individuals had similar major LEA outcomes between GLP-1RA and SGLT2i users, a contrast to the more pronounced benefit observed in other groups. Previous research has highlighted disparities in GLP-1RA and SGLT2i prescription rates among Hispanic individuals, which may contribute to disparities in long-term outcomes (28,29). Additionally, to account for historical prescribing differences, we restricted analyses to post-2018 prescriptions, incorporating newer SGLT2i (dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ertugliflozin) and GLP-1RA (dulaglutide, albiglutide, and semaglutide) approvals. This adjustment is crucial given the earlier approval of GLP-1RAs (2005) compared with SGLT2is (2013). A prior U.S. database study (2013–2015) found no difference between SGLT2is and GLP-1RAs for lower-limb outcomes (adjusted HR 1.47 [95% CI 0.64, 3.36]), possibly due to early-generation agents (30). However, our analysis with newer therapies consistently showed reduced amputation risk with GLP-1RA use, reinforcing its protective effect beyond historical prescribing patterns. Finally, recognizing GLP-1RAs’ potential neuroprotective effects, we conducted an analysis in individuals with peripheral neuropathy (17,31). We found that GLP-1RA use was associated with an even greater protective effect (HR 0.68 [95% CI 0.56, 0.83]) compared with the main analysis (HR 0.77 [95% CI 0.66, 0.90]). Taken together, these findings suggest that GLP-1RAs confer broad protective benefits across diverse populations.

The potential limb-protective effects of GLP-1RAs may be attributed to their multifaceted metabolic and vascular benefits. These include glycemic control through enhancing insulin secretion, inhibiting glucagon release, delaying gastric emptying, and promoting satiety, which lead to a reduction in HbA1c (32,33). Beyond glycemic control, GLP-1RAs positively impact weight loss, blood pressure, lipid profiles, peripheral perfusion, and possibly endothelial function, factors that contribute to a lower risk of vascular complications, including those that might lead to amputations (34–36). Furthermore, preclinical studies have suggested that GLP-1RAs and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors promote angiogenesis, reduce inflammation, and accelerate wound healing, further supporting their protective role in DFU prevention (37,38). These combined effects likely contribute to improved vascular health and a reduced risk of major adverse limb events.

Our findings further highlight the utility of GLP-1RAs for high-risk individuals with DFUs or PAD. Beyond glycemic control, GLP-1RAs improve renal outcomes and reduce the risk of diabetic nephropathy, conditions closely associated with LEA risk (39,40). These combined benefits position GLP-1RAs as an effective and safe alternative to SGLT2is for preventing amputations in vulnerable populations. Prospective trials are needed to confirm these findings and further explore the limb-preserving benefits of GLP-1RAs.

This study has several limitations. As a retrospective analysis, it is limited in establishing causal relationships with possible residual confounding despite propensity score matching. Reliance on EHRs introduces potential biases from coding errors and variability in documentation. For example, while mortality data were captured from multiple sources, out-of-hospital deaths may be underreported (14). Additionally, TriNetX does not provide patient-level data, limiting adjustments for missingness. We lacked detailed diabetes-related data, including disease duration, which could further refine risk stratification. Individual SGLT2is and GLP-1RAs were not analyzed separately, preventing drug-specific comparisons. The relatively short follow-up period, reflective of the recent adoption of GLP-1RAs and SGLT2is, limited the ability to assess long-term outcomes. Finally, medication adherence, switching, or discontinuation was not captured, though sensitivity analysis requiring an additional prescription within 6 months after initiation confirmed consistent findings. Future research should address these limitations with longer follow-up, detailed clinical data, and robust medication tracking to better characterize the association between these drug classes and lower-extremity complications.

In this large, nationally representative cohort study, GLP-1RAs were associated with significantly lower risks of major and minor amputations, DFU development, and mortality compared with SGLT2is. These findings build on previous literature highlighting potential benefits of GLP-1RAs to reduce lower-extremity adverse events in people with type 2 diabetes. Further research is needed to investigate the long-term mechanisms underlying these benefits and to explore broader clinical implications to optimize treatment strategies in diabetes and limb preservation care.

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.29225690.

Article Information

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. A.T.H., I.Y.L., F.L., C.-D.S., and T.-W.T. were involved in the conception, design, and conduct of the study and the analysis and interpretation of the results. L.S., C.-H.H., C.-D.S., D.G.A., and T.-W.T. advised on the study design and provided specialist input. A.T.H., I.Y.L., and T.-W.T. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors edited, reviewed, and approved the final version of the manuscript. T.-W.T. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentation. Parts of this study were presented in oral form at the 85th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, Chicago, IL, 20–23 June 2025.

Handling Editors. The journal editors responsible for overseeing the review of the manuscript were Elizabeth Selvin and Naveed Sattar.

Funding Statement

This study is partially supported by National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants 1K23DK122126 and 1R03DK140420.

Footnotes

See accompanying article, p. 1713.

Supporting information

References

- 1. Lazzarini PA, Cramb SM, Golledge J, Morton JI, Magliano DJ, Van Netten JJ.. Global trends in the incidence of hospital admissions for diabetes-related foot disease and amputations: a review of national rates in the 21st century. Diabetologia 2023;66:267–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Armstrong DG, Tan T-W, Boulton AJM, Bus SA.. Diabetic foot ulcers: a review. JAMA 2023;330:62–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chamberlain RC, Fleetwood K, Wild SH, et al. Foot ulcer and risk of lower limb amputation or death in people with diabetes: a national population-based retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 2022;45:83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Walicka M, Raczyńska M, Marcinkowska K, et al. Amputations of lower limb in subjects with diabetes mellitus: reasons and 30-day mortality. J Diabetes Res 2021;2021:8866126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boulton AJM. The diabetic foot: from art to science. The 18th Camillo Golgi lecture. Diabetologia 2004;47:1343–1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Armstrong DG, Swerdlow MA, Armstrong AA, Conte MS, Padula WV, Bus SA.. Five year mortality and direct costs of care for people with diabetic foot complications are comparable to cancer. J Foot Ankle Res 2020;13:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Molina Cs, Faulk J.. Lower extremity amputation. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, et al. Comparison of the effects of glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors for prevention of major adverse cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2019;139:2022–2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. ; CANVAS Program Collaborative Group . Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017;377:644–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lin C, Zhu X, Cai X, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors and lower limb complications: an updated meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2021;20:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lu Y, Guo C.. Risk of lower limb amputation in diabetic patients using SGLT2 inhibitors versus DPP4 inhibitors or GLP-1 agonists: a meta-analysis of 2 million patients. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2023;14:20420986231178126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ueda P, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and risk of serious adverse events: nationwide register based cohort study. BMJ 2018;363:k4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Palmer SC, Tendal B, Mustafa RA, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter protein-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2021;372:m4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Palchuk MB, London JW, Perez-Rey D, et al. A global federated real-world data and analytics platform for research. JAMIA Open 2023;6:ooad035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative . Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Richesson RL, Rusincovitch SA, Wixted D, et al. A comparison of phenotype definitions for diabetes mellitus. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013;20:e319–e326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lin DS-H, Yu A-L, Lo H-Y, Lien C-W, Lee J-K, Chen W-J.. Major adverse cardiovascular and limb events in people with diabetes treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists vs SGLT2 inhibitors. Diabetologia 2022;65:2032–2043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nagahisa T, Saisho Y.. Cardiorenal protection: potential of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther 2019;10:1733–1752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Du Y, Bai L, Fan B, et al. Effect of SGLT2 inhibitors versus DPP4 inhibitors or GLP-1 agonists on diabetic foot-related extremity amputation in patients with T2DM: a meta-analysis. Prim Care Diabetes 2022;16:156–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dhatariya K, Bain SC, Buse JB, et al. ; LEADER Trial Investigators . The impact of liraglutide on diabetes-related foot ulceration and associated complications in patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk for cardiovascular events: results from the LEADER trial. Diabetes Care 2018;41:2229–2235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baviera M, Genovese S, Lepore V, et al. Lower risk of death and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes initiating glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors: a real-world study in two Italian cohorts. Diabetes Obes Metab 2021;23:1484–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boyko EJ, Zelnick LR, Braffett BH, et al. Risk of foot ulcer and lower-extremity amputation among participants in the diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study. Diabetes Care 2022;45:357–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Werkman NCC, Driessen JHM, Klungel OH, et al. Incretin-based therapy and the risk of diabetic foot ulcers and related events. Diabetes Obes Metab 2024;26:3764–3780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heyward J, Mansour O, Olson L, Singh S, Alexander GC.. Association between sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and lower extremity amputation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2020;15:e0234065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Werkman NCC, Driessen JHM, Stehouwer CDA, et al. The use of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists versus sulfonylureas and the risk of lower limb amputations: a nation-wide cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2023;22:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khouri C, Cracowski JL, Roustit M.. SGLT-2 inhibitors and the risk of lower-limb amputation: is this a class effect? Diabetes Obes Metab 2018;20:1531–1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Potier L, Mohammedi K, Velho G, Roussel R.. SGLT2 inhibitors and lower limb complications: the diuretic-induced hypovolemia hypothesis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2021;20:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lamprea-Montealegre JA, Madden E, Tummalapalli SL, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with prescription of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP1 receptor agonists among patients with type 2 diabetes in the Veterans Health Administration system. JAMA 2022;328:861–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kunutsor SK, Khunti K, Seidu S.. Racial, ethnic and regional differences in the effect of sodium–glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. J R Soc Med 2024;117:267–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chang HY, Singh S, Mansour O, Baksh S, Alexander GC.. Association between sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and lower extremity amputation among patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1190–1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mehta K, Behl T, Kumar A, Uddin MS, Zengin G, Arora S.. Deciphering the neuroprotective role of glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists in diabetic neuropathy: current perspective and future directions. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2021;22:4–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nauck MA, Quast DR, Wefers J, Meier JJ.. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes - state-of-the-art. Mol Metab 2021;46:101102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andersen A, Lund A, Knop FK, Vilsbøll T.. Glucagon-like peptide 1 in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018;14:390–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rizzo M, Nikolic D, Patti AM, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and reduction of cardiometabolic risk: potential underlying mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2018;1864:2814–2821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nauck MA, Meier JJ, Cavender MA, Abd El Aziz M, Drucker DJ.. Cardiovascular actions and clinical outcomes with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Circulation 2017;136:849–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Caruso P, Maiorino MI, Longo M, et al. Liraglutide for lower limb perfusion in people with type 2 diabetes and peripheral artery disease: the STARDUST randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2024;7:e241545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nagae K, Uchi H, Morino-Koga S, Tanaka Y, Oda M, Furue M.. Glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue liraglutide facilitates wound healing by activating PI3K/Akt pathway in keratinocytes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018;146:155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schürmann C, Linke A, Engelmann-Pilger K, et al. The dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor linagliptin attenuates inflammation and accelerates epithelialization in wounds of diabetic ob/ob mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012;342:71–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sattar N, Lee MMY, Kristensen SL, et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2021;9:653–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kristensen SL, Rørth R, Jhund PS, et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;7:776–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.