Abstract

Background and Objectives:

After hysterectomy, patients are counseled on behavioral limitation, such as avoiding vaginal intercourse and heavy lifting, to try to optimize healing. There are limited data on the benefits of these restrictions and on the impact on patients. This study aimed to evaluate patients’ adherence to and perception of behavioral restrictions after total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey study of patients who underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy and completed the survey at their postoperative appointment between January 3 and March 31, 2023. Patients had been counseled to avoid submersion in water, strenuous exercise, and lifting > 10 pounds for at least 6 weeks, and to avoid vaginal penetration for 12 weeks after surgery. Convenience sampling was used.

Results:

A total of 71 patients were eligible and 50 (70%) participated. The mean time to postoperative appointment was 32 days. Participants reported inconsistent adherence to behavioral guidelines. 49/50 (98%) patients avoided vaginal penetration, 46/50 (92%) avoided submerging in water, 21/49 (43%) avoided lifting > 10 pounds. Within 4 weeks, > 90% of patients returned to driving, housework, and shopping and 21/36 (58%) of employed patients returned to work. 21/47(45%) of participants reported that adhering to postoperative restrictions was at least “a little bit challenging,” with home responsibilities cited as the primary challenge.

Conclusion:

Patients inconsistently followed behavioral restrictions after total laparoscopic hysterectomy and described them as difficult to follow due to other responsibilities. Future studies should explore the necessity of postoperative restrictions and strategies for improving adherence to restrictions that optimize patient safety.

Keywords: Laparoscopic hysterectomy, Postoperative restrictions, Surgical recovery, Vaginal cuff dehiscence

INTRODUCTION

Hysterectomy is one of the most commonly performed procedures in the United States, with over 600,000 surgeries performed annually.1 Patients typically receive counseling on postoperative behavioral limitations to optimize healing and decrease risk of complications.2 One of the primary goals of these limitations after a total hysterectomy is to reduce the risk vaginal cuff dehiscence. Cuff dehiscence is one of the most dangerous complications after a hysterectomy, typically requiring additional surgery and, if not managed expeditiously, it can lead to evisceration and significant morbidity.3

As a precaution, most surgeons counsel patients to wait several weeks after total hysterectomy prior to engaging in vaginal penetration, to prevent physical trauma to the cuff, or performing heavy lifting, to prevent Valsalva causing increased pressure on the cuff. In one study, 99% of 287 surgeons surveyed recommend restricting intercourse after hysterectomy for a mean of 5.8 weeks (range 2–12 weeks).2 In another study, over 80% of surgeons gave patients lifting restrictions, with 50% recommending a max weight of 10 pounds (4.5 kilograms).4 These types of precautions may be warranted, as prior work has shown cuff dehiscence can occur with the first postoperative coitus, straining with defecation, and Valsalva; although frequently a cuff dehiscence will happen spontaneously.5 One review article noted 8–48% of patients reported intercourse prior to dehiscence, 16–30% reported defecation or Valsalva (cough or sneeze) prior to dehiscence.6 Additionally, there are likely nonbehavioral factors that put patients at higher risk for cuff dehiscence, such as tissue quality, infection, or surgical technique.5

While most surgeons recommend limiting vaginal penetration and heavy lifting postoperatively, there is no empiric data identifying the optimal time interval of these restrictions to reduce complications. One case series found that the average time interval between hysterectomy and cuff dehiscence was 11 weeks, with a range of 4–55 weeks,5 however most surgeons do not limit activity beyond 6 weeks.2 Similarly, there are not empiric data that support the optimal weight for lifting restrictions. Recent studies have shown that many activities of daily life, such as coughing or rising from sitting to standing, increase intraabdominal pressure by a greater amount than lifting a 10-pound weight off the floor.7,8 As such, it may be futile to try to prevent undue pressure on the cuff via 10-pound lifting restrictions. In the setting of lacking data, specifics of postoperative restrictions vary significantly between providers. Most of the guidance is based on anecdote, with surgeons basing their recommendations on the counseling of their mentors or personal preference.9 This is not a problem unique to gynecology; optimal behavioral restrictions after hernia repair are similarly poorly studied with varied guidance between different providers.10

In addition to limited data supporting postoperative behavioral restrictions, some studies have shown there may even be benefit from allowing more liberal lifting and exercise. Literature from orthopedics demonstrates that loading muscles promote tissue remodeling and strengthens muscle and surrounding tissue.11 Within gynecology, recent randomized control trials support the potential benefit of liberalizing restrictions after pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Mueller et al showed more liberal activities after prolapse repair led to similar patient satisfaction, fewer prolapse and urinary symptoms, and no anatomic differences.12 O’Shea et al similarly found noninferior anatomic outcomes when comparing liberalized verses restricted activities after prolapse surgery.13

Given the limited data on optimal postoperative restrictions, a recent review article concluded that the effect of physical activity restrictions on recovery has been overlooked in gynecology, and strict activity restriction may cause patient burden without any therapeutic benefit.14 This potential burden has not been well studied. It is not currently known how well patients are able to adhere to recommended restrictions and the degree to which these restrictions cause patient burden. Restrictions may force patients to take extended time off work and limit their ability to perform key activities of daily living, such as carrying in groceries or lifting their children. This interference with daily life may lead to low adherence. To our knowledge, there are limited studies assessing patient perceptions of and adherence to behavioral restrictions after hysterectomy. This study aimed to evaluate patient experience with standard postoperative behavioral restrictions after total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH).

METHODOLOGY

This study was a cross-sectional analysis of a quality improvement survey database of patients who had a TLH at a single center, tertiary care, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery practice in southeastern United States. As part of an internal quality improvement project, patients filled out a survey at their routine postoperative appointment (Appendix 1). This study analyzed the survey responses of a convenience sample of 50 patients who had completed the survey between January 3, 2023, and March 31, 2023. Inclusion criteria in this study included having a TLH, literate in English or Spanish, and postoperative visit between 21 and 35 days after surgery. Exclusion criteria included an additional operation from another surgical service (eg, hernia repair, bowel resection) concurrently with hysterectomy. A Spanish version of the survey was translated by professional medical interpreters. Additional information was collected from the patients’ electronic medical record.

In our practice, patients are counseled to avoid submersion in water, strenuous exercise, and lifting > 10 pounds for at least 6 weeks and to avoid vaginal penetration for 12 weeks after surgery. The survey included an assessment of the activity of patients during the postoperative period, as well as their perception of postoperative behavioral restrictions guidance. It asked about the frequency of certain activities since surgery, specifically lifting > 10 pounds, lifting > 20 pounds, rigorous exercise, vaginal penetration, submersion in water. Avoiding lifting > 20 pounds was not explicitly discussed in postoperative instructions, however this question was intended to assess if patients were avoiding very heavy lifting, even if unable to adhere to the 10-pound recommendation. The survey also asked when patients first were able to return to their normal activities (driving a car, going shopping, performing housework, employment) and assessed how challenging patients felt it was to follow the recommended postoperative instructions. Patients were also queried to what extent different factors affected their ability to follow the postoperative instructions including home responsibilities, work responsibilities, lack of support, and forgetting instructions. Patients were given paper surveys, informed that this survey was optional, and that their answers would not be shared with their providers. They were informed the survey aimed to learn more about the way surgery impact patients’ lives.

Data analysis was conducted in SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were calculated; categorical variables were assessed with number and frequency and continuous variables were calculated as mean and standard deviation (SD). The study protocol was approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Between January 2023 and March 2023, 71 patients were eligible for participating in the study and 50 completed the survey (70%). The other 21 patients either did not receive the correct survey form or elected to not complete the survey. The time between TLH and routine postoperative appointment had a mean of 32 days (SD = 4). The mean age in the sample was 42 years (SD = 10), the mean BMI was 32 kg/m2 (SD = 9) and 79% of the sample reported being employed (Table 1). The most common indications for surgery were fibroids (42%), abnormal uterine bleeding (34%), and endometriosis (24%). Some patients had multiple indication for surgery (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Patients (n = 50) | |

|---|---|

| Days after surgery, mean (SD) | 32 (4) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 42 (10) |

| BMI, kg/m², mean (SD) | 32 (9) |

| Smoker, n (%) | 3 (6%) |

| Diabetic, n (%) | 8 (16%) |

| Married or partnered, n (%) | 25 (50%) |

| Employed, n (%) | 38 (79%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5 (10%) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 45 (90%) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0%) |

| Asian | 0 (0%) |

| Black or African American | 13 (26%) |

| Other/not listed | 7 (14%) |

| White | 30 (60%) |

| Language, n (%) | |

| English | 46 (92%) |

| Spanish | 4 (8%) |

| Preoperative diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Fibroids | 21 (42%) |

| Chronic pelvic pain | 18 (36%) |

| Abnormal uterine bleeding | 17 (34%) |

| Endometriosis | 12 (24%) |

| Other | 9 (18%) |

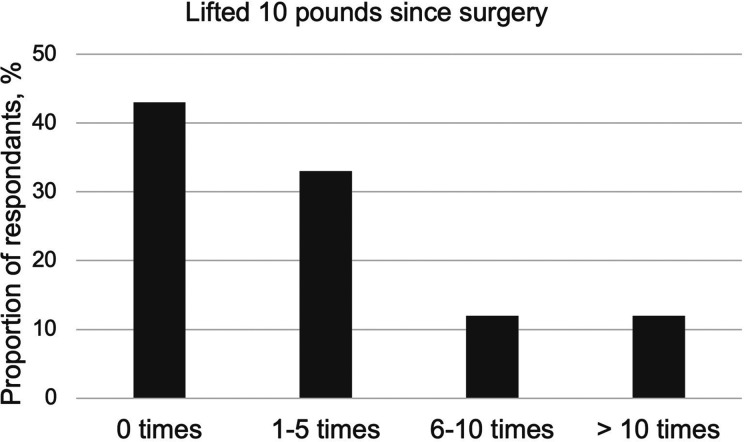

Participants reported inconsistent adherence to postoperative behavioral guidelines; 49/50 (98%) patients avoided vaginal penetration at the time of the routine postoperative visit, 46/50 (92%) avoided submerging in water, 41/49 (84%) avoided strenuous exercise (Table 2). Only 21/49 (43%) were able to avoid lifting > 10 pounds, with 6/49 (12%) reporting lifting > 10 pounds more than 10 times since surgery, and 42/50 (84%) avoiding lifting > 20 pounds (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Reported Adherence to Postoperative Restrictions at Postoperative Appointment

| Restriction | Patients, Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Avoided vaginal penetration | 49/50 (98%) |

| Avoided submerging in water | 46/50 (92%) |

| Avoided strenuous exercise | 41/49 (84%) |

| Avoided lifting 10 pounds | 21/49 (43%) |

| Avoided lifting 20 pounds | 42/50 (84%) |

Figure 1.

Patient reported instances of lifting 10 pounds or greater at postoperative appointment.

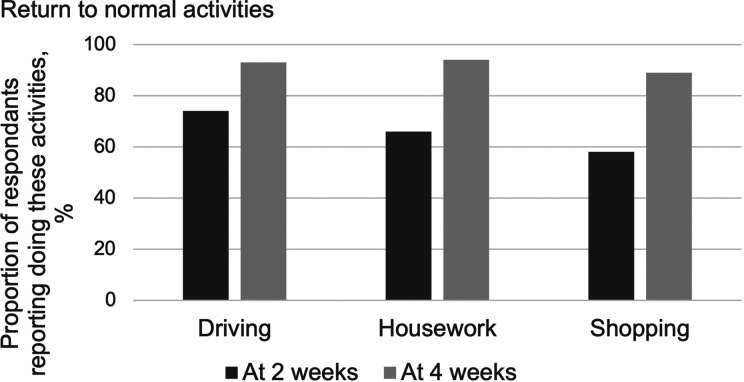

Most patients were able to return to most of their normal daily activities within 2 weeks; 34/46 (74%) reported driving, 33/50 (66%) reported performing routine housework, and 28/48 (58%) reported shopping. Within 4 weeks, > 90% of patients reported doing these activities (Figure 2). Of patients who were employed, 21/36 (58%) returned to work within 4 weeks.

Figure 2.

Patient reports of returning to activities by 2 weeks and 4 weeks postoperatively.

About half of participants, 21/47, reported that adhering to postoperative restrictions was at least “a little bit challenging.” When asked about why it was challenging, home responsibilities and work responsibilities were the most common reasons (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Reasons patients endorsed as barriers to adhering to postoperative behavioral restrictions.

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSIONS

Participants in this study reported inconsistent adherence to postoperative behavioral guidelines one month after TLH. While some recommendations were well followed, with 98% patients avoided vaginal penetration at the time of the routine postoperative visit and 92% avoided submerging in water, other restrictions were not, as only 43% avoided lifting > 10 pounds. About half of participants (44%) found adhering to postoperative restrictions at least “a little bit challenging,” with home responsibilities and work responsibilities being the most common reasons.

Optimizing patient adherence to recommendations is a concern in many areas of medicine. This study showed inconsistent adherence to postoperative restrictions. Some of the factors affect adherence are likely specific to each practice or provider, such as the manner of counseling, which has also been found across specialties.15 This study may encourage surgeons to assess their own patients’ adherence to postoperative instructions, and potential adjust their counseling, if needed. Future studies could assess the optimal counseling techniques to improve adherence to postoperative restrictions. Other factors affecting adherence are likely patient rather than clinician dependent, such as a patient’s home and work responsibilities. These factors would be very challenging, if not impossible, to modify to improve restriction adherence. This study suggests the importance of assessing patients’ home and work responsibilities in regard to their ability to follow postoperative restrictions. This may allow scheduling surgery when a patient has more help at home or can take more time off from employment that requires lifting. For some patients unable to adhere to TLH postoperative restrictions, surgeons may recommend an alternate treatment, such as a supracervical hysterectomy, that does not come with the same risk of vaginal cuff dehiscence. Future qualitative studies could assess the specific reasons it was challenging to adhere to restrictions, further informing counseling to optimize patient safety.

Given that it was challenging for many patients to adhere to restrictions, this study further supports the continued exploration of the necessity of postoperative restrictions. Limiting lifting to less than 10 pounds was the restriction least likely to be followed, which may indicate it is the restriction most interferes with daily life. A 10-pound restriction would preclude patients from lifting most bags of groceries, children older than 2 months, and many backpacks, purses, and pets. Notably, less than 60% of patients returned to work at 4 weeks, despite reporting many other activities (> 90% reported driving, shopping, housework). It is possible that our imposed lifting restrictions would prevent them from fulfilling their job duties. These lifting restrictions may therefore be associated with significant social, family, and financial burden. Studies have shown that liberalizing lifting restrictions may not cause increased complications.13 If this is further supported, it is possible these restrictions are unnecessary and removing them could lead to improved productivity and quality of life, without worse outcomes.

The primary strength of this study was collecting patient perspectives on the restrictions, rather than objective outcomes alone. It is one of the few studies to focus on patient perceived acceptability and burden of routine postoperative restrictions.

There are several limitations of this study. This study was unable to assess the relationship between patient perspective/adherence and clinical outcomes. Larger studies would be necessary to achieve statistic power to evaluate this relationship, and ideally would have longitudinal patient follow up. Additionally, this study relied on self-reported, recall data. Patients may forget their activities over the last month, and may be biased, explicitly or implicitly, to report the “right answer” (i.e. adherence). Additionally, this was a single center study and given the diversity of postoperative restrictions and counseling, these results may be limited in their generalizability.

This study illustrates the importance of understanding patient perspective when recommending behavioral restrictions. These results may help guide counseling and surgical planning for TLH. This study also strongly supports the need for future research in the optimal postoperative behavioral restrictions in order to balance minimizing complications without unduly burdening patients’ ability to participate in their lives.

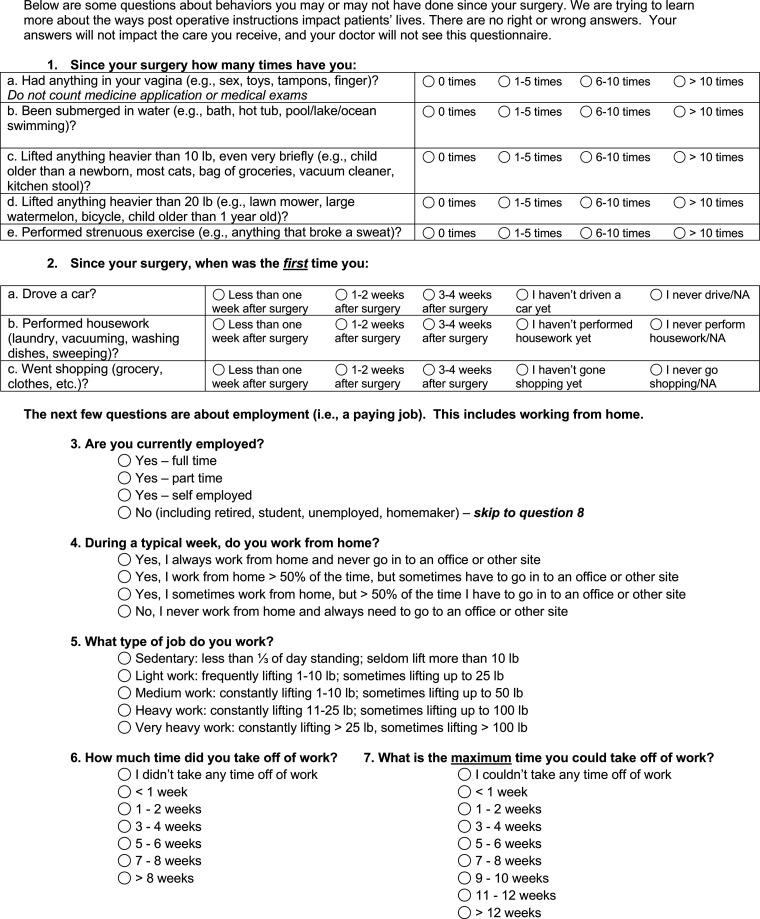

Appendix 1. Copy of survey given to patients at their postoperative visit.

Footnotes

Disclosure: none.

Conflict of interests: none.

Funding sources: none.

Contributor Information

R. Gina Silverstein, Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA. (Drs. Silverstein, LeCroy, Abu-Alnadi, Carey, and McClurg).

Katie LeCroy, Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA. (Drs. Silverstein, LeCroy, Abu-Alnadi, Carey, and McClurg).

Noor Dasouki Abu-Alnadi, Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA. (Drs. Silverstein, LeCroy, Abu-Alnadi, Carey, and McClurg).

Erin Carey, Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA. (Drs. Silverstein, LeCroy, Abu-Alnadi, Carey, and McClurg).

Asha McClurg, Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA. (Drs. Silverstein, LeCroy, Abu-Alnadi, Carey, and McClurg).

References:

- 1.Discharges with at Least One Procedure in Nonfederal Short-Stay Hospitals, by Sex, Age, and Selected Procedures: United States, Selected Years 1990 through 2009–2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2013/098.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2024.

- 2.FitzGerald MP, Shisler S, Shott S, Brubaker L. Physical limitations after gynecologic surgery. J Pelvic Surg. 2001;7(3):136–139. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nezhat C, Kennedy Burns M, Wood M, Nezhat C, Nezhat A, Nezhat F. Vaginal cuff dehiscence and evisceration: a review. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(4):972–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winkelman WD, Erlinger AL, Haviland MJ, Hacker MR, Rosenblatt PL. Survey of postoperative activity guidelines after minimally invasive gynecologic and pelvic reconstructive surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26(12):731–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hur HC, Guido RS, Mansuria SM, Hacker MR, Sanfilippo JS, Lee TT. Incidence and patient characteristics of vaginal cuff dehiscence after different modes of hysterectomies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(3):311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cronin B, Sung VW, Matteson KA. Vaginal cuff dehiscence: risk factors and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(4):284–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw JM, Hamad NM, Coleman TJ, et al. Intra-abdominal pressures during activity in women using an intra-vaginal pressure transducer. J Sports Sci. 2014;32(12):1176–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weir LF, Nygaard IE, Wilken J, Brandt D, Janz KF. Postoperative activity restrictions: any evidence? Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(2 Pt 1):305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minig L, Trimble EL, Sarsotti C, Sebastiani MM, Spong CY. Building the evidence base for postoperative and postpartum advice. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(4):892–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaaf S, Willms A, Schwab R, Güsgen C. Recommendations on postoperative strain and physical labor after abdominal and hernia surgery: an expert survey of attendants of the 41st EHS Annual International Congress of the European Hernia Society. Hernia. 2022;26(3):727–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckwalter JA. Activity vs. rest in the treatment of bone, soft tissue and joint injuries. Iowa Orthop J. 1995;15:29–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller MG, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Collins SA, Abernethy MG, Alverdy A, Kenton K. Activity restriction recommendations and outcomes after reconstructive pelvic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(4):608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Shea M, Siddiqui NY, Truong T, Erkanli A, Barber MD. Standard restrictions vs expedited activity after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2023;158(8):797–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mueller MG, Kenton K. Activity restrictions after gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2024;143(3):378–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James M, Roy A, Antony E, George S. Impact of patient counseling on treatment adherence behavior and quality of life in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2021;32(5):1382–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]