Abstract

Cerebral small vessel disease is a neurological complication of sickle cell disease (SCD) associated with cerebral hypoperfusion and cognitive dysfunction. Early and prompt detection is important for prevention and treatment, preferably with a non-invasive, inexpensive point-of-care test. Impaired cerebral autoregulation (CA) is a marker of cerebral small vessel disease, so we evaluated whether imaging hemodynamic changes in the microvasculature can assess abnormal CA in patients with SCD. We instructed patients (n=13) and healthy controls (n=14) to breathe at three different rates using a metronome while frequency-domain near-infrared spectroscopy (FDNIRS), a non-invasive optical imaging method, measured the phase delay and amplitude ratios between oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin concentration changes. These measurements served as a surrogate measure of CA efficiency. We applied a mathematical hemodynamic model to calculate blood transit times and CA efficiency. We found that patients with SCD had significantly lower phase difference between oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin oscillations (−320° to −340°) than controls (−200° to −240°), indicating differences in CA and blood transit time between the groups. Cerebral tissue oxygen saturation was reduced in patients with SCD (63.1% ± 7.8%) compared to controls (66.1% ± 4.7%). The hemodynamic model further found a significant difference in the capillary transit time and autoregulation cutoff frequency between SCD (1.88 ± 0.14s; 0.016 ± 0.0033Hz) and controls (0.71 ± 0.24s, p<0.05; 0.02 ± 0.0052Hz, p<0.05). Herein, we present preliminary evidence of the utility of NIRS to monitor CA in SCD; NIRS may represent a new screening method for cerebral small vessel disease in SCD.

Keywords: sickle cell disease, cerebral small vessel disease, cerebral autoregulation, near-infrared spectroscopy, blood transit times, cerebral tissue oxygen saturation

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

This study explored near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) for monitoring cerebral autoregulation (CA) in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD). Cerebral small vessel disease, a complication of SCD, is associated with cerebral hypoperfusion and cognitive dysfunction. The results revealed that SCD exhibited impaired CA, longer blood transit times, and decreased tissue oxygen saturation compared to healthy controls. NIRS shows promise as a tool for screening cerebral small vessel disease in SCD, providing preliminary evidence of its utility..

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Cerebral small vessel disease is a complication of sickle cell disease (SCD) that currently lacks adequate screening strategies (1). Early detection of cerebral small vessel disease is important since interventions such as blood transfusions may slow its progression (2,3). Silent cerebral infarcts are defined as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-detectable lesions in the absence of a history or symptoms of stroke and are the most common evidence of small vessel disease in SCD (4–6). They are associated with cognitive dysfunction in children with SCD and are a predictor of stroke risk in SCD, diabetes, hypertension, and other vascular diseases (7–9). The main limitations of MRI as the primary screening tool for silent cerebral infarcts are its cost, the need for sedation in young children, and limited universal availability, particularly in low- and middle-income Countries that bear the highest prevalence of SCD.

Cerebral small vessel disease disrupts neuroprotective mechanisms, including cerebral autoregulation (CA) (10–12), a process that controls changes in cerebral blood flow when cerebral perfusion pressure or arterial blood pressure varies (13–18). CA has been found to be impaired or altered in a variety of diseases, including diabetes, stroke, and traumatic brain injury (19–21), and CA impairment has been associated with worse neurological outcomes (22). The assessment of CA varies, and no standard method exists.

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) may provide an affordable and portable alternative to MRI for detecting small vessel disease in SCD through an CA assessment. NIRS can measure microvasculature-level hemodynamic changes during paced breathing (15,23–27). Reinhard et al. 2006 found that the time delay between oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin concentration changes was strongly correlated with the phase shift between mean arterial pressure and cerebral blood flow velocity, indicating that hemodynamic signals measured with NIRS could be used as a proxy to assess CA. This approach has already been used to show CA differences between healthy controls, patients with a history of cerebrovascular disease (Reinhard et al., 2006), and patients undergoing dialysis (28). In addition, our group has applied a recent hemodynamic model by Fantini for NIRS measurements that translates relative phase delays to quantifiable physiological parameters, such as blood transit times in the microvasculature, CA efficiency, and blood volume ratios between arterial and venous blood (28–31).

In the study presented herein, we utilized NIRS with a hemodynamic model to study the underlying mechanisms that lead to differences in CA between adult patients with SCD and healthy, age-matched controls by calculating parameters related to perturbations in the brain, such as blood transit times, CA efficiency, rate of oxygen diffusion, and blood volume ratios between arterial and venous blood. In addition, we measured cerebral tissue oxygen saturation using NIRS in both groups, an important marker of cerebral health in SCD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used frequency-domain NIRS (FD-NIRS) to measure cerebral hemodynamic changes in adult patients with SCD and healthy controls performing a paced breathing paradigm (32–34). Data were analyzed in terms of phase differences and amplitude ratios of the hemodynamic signals. A mathematical model (31,35) was also applied to extract parameters related to CA efficiency and blood transit times, which are related to cerebral blood flow.

Participants

The participants were enrolled in this study in accordance with the Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines at Carnegie Mellon University (IRB# STUDY2017_00000578) and the University of Pittsburgh (IRB# PRO17080634). Written and verbal consent was obtained from all participants before the start of the study. A total of 27 participants were enrolled, 13 adult patients with SCD (mean: 40.60 years, std: 12.70 years, 9 males and 4 females) and 14 healthy, age- and race-matched controls (mean: 40.70 years, std: 10.10 years, 8 males and 6 females) with no medical history of neurological or cardiovascular disorders. Patients with all SCD genotypes (e.g., HbSS, HbSC, HbSβ0- and HbSβ+-thalassemia) (36) were recruited from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Adult Sickle Cell Program if in steady-state, defined as the absence of acute complications.

Patients on SCD-directed therapies who had a recent blood transfusion or were taking hydroxyurea were categorized as “SCD (Intervention)” in the Tables and Figures to analyze the impact of transfusions and hydroxyurea on hemoglobin levels, hematocrit, and oxygen affinity, factors that can improve perfusion and influence CA (37). Three patients with SCD were using hydroxyurea but had not received blood transfusions, and three patients with SCD had a recent blood transfusion but were not taking hydroxyurea.

Experimental Setup and Data Collection

NIRS measurements were conducted on all participants using a commercial multi-distance FD-NIRS system (OxiplexTS, ISS Inc, Champaign, IL) to acquire cerebral changes in concentration of oxyhemoglobin (O), deoxyhemoglobin (D), total hemoglobin (T), and cerebral tissue oxygen saturation of hemoglobin (StO2). The NIRS system uses two wavelengths, 690 nm and 830 nm, for illumination. The source-detector distances were 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, and 3.5 cm. Data were collected at a sampling frequency of 5 Hz.

Bilateral NIRS measurements were acquired by placing two optical probes on the forehead above the eyebrow (Figure 1); each probe covered the orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex on each cerebral hemisphere while secured with medical adhesive. The experiment was performed in a dark room. Participants were asked to perform paced breathing in an experimental block design to induce controlled blood pressure oscillations at three unique breathing rates for a 2-minute duration while sitting upright in a chair. The breathing rates were performed in a sequential order of 6, 10, and 7.5 breaths per minute, corresponding to three discrete frequencies, 0.100, 0.167, and 0.125 Hz. A breathing metronome guided participants on a cellular device, which prompted inhalation and exhalation for each paced breathing session. A 2-minute baseline measurement was recorded before the first paced breathing, followed by a 2-minute duration resting period after the first and second paced breathing sessions. The final resting session was 1-minute. The respiratory rate was recorded by placing a respiration belt around the participant’s chest (Sleepmate Piezo Effort Sensors, Ambu Inc., Columbia, MD). Blood pressure measurements were acquired from the finger and arm cuffs attached to a beat-to-beat plethysmography system (CNAP Monitor, CNSystems GmbH, Graz, Austria) (Figure 1). The total experimental time duration was ~ 13 minutes for each participant.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup. Device connection and placement are respective to the participant.

Paced breathing was used to induce sinusoidal MAP oscillations, translating to oscillations in all physiological signals (Figure 1). Data quality for the multi-distance approach was assessed based on fitting a straight line to ln(r2*AC(r)) and phase(r) (38,39), where AC is the modulation amplitude of the light intensity and phase refers to the phase of the modulated light between the shortest and longest source-detector distance, r. Participants with poor correlation between the fitted line and the average logarithmic intensity or phase (<98% for AC; <95% for phase) were excluded. Using the multi-distance approach (39), absolute valued hemoglobin — O, D, and T — were calculated. From these absolute values, baseline tissue oxygen saturation of hemoglobin, StO2=O/T, was calculated within the minute before paced breathing started. In addition, relative changes in hemoglobin concentrations, ΔO(t), ΔD(t), and ΔT(t), were calculated from intensity changes measured with the longest source-detector separation, 3.5 cm, based on the modified Beer-Lambert law (40). Slow temporal drifts were removed from the hemoglobin concentration time traces by applying polynomial detrending (Figure 2). Any data showing strong motion artifacts as defined as spikes in the time traces or a lack of signal quality markers such as a clear heart rate or respiration-based changes were excluded from the study.

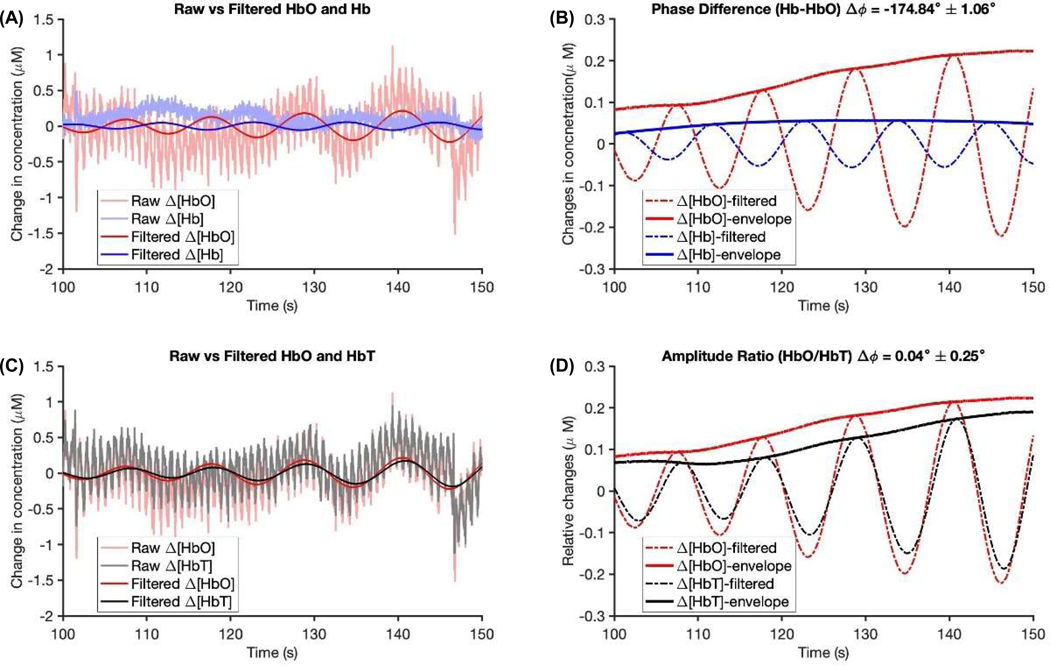

Figure 2.

Example of filtered-varying oscillations, ΔO(t) and ΔD(t), from measurements of 2-minute duration at 0.100 Hz paced breathing for one healthy control with (A) time traces of ΔO(t) and ΔD(t), and (B) ΔO(t) and ΔT(t). There is coherence between the ΔO(t) and ΔT(t) that is consistently higher during paced breathing, Figure 2(B).

A linear narrow bandpass filter was applied to the hemoglobin concentration changes using a linear phase finite impulse response filter based on the Parks–McClellan algorithm (41). The filter was set to a center frequency at each paced breathing frequency, and its bandwidth was set to 0.005 Hz. This filter was also applied to isolate cerebral hemodynamics induced by paced breathing at the specified frequencies, by removing cardiac pulsation, Meyer’s waves, and other physiological signals associated with respiration. Using these Hilbert transformed bandpass filtered paced breathing signals, we presented amplitude and phase information using the frequency domain phasor notation of the tissue hemoglobin concentrations, , , and , where represents the paced breathing frequency. We computed the amplitude ratios, and , and phase latency, and , where arg represents the angle. Using circular statistics (42), mean and standard error values were calculated for amplitude ratios and phase differences between , , and per each 2-minute paced breathing duration.

We further excluded paced breathing data segments if any of the following exclusion criteria were met: 1) the measured paced breathing range detected within the NIRS signal demonstrated that the participant was breathing well outside of the range for the instructed paced breathing segment; 2) the amplitude of at the paced frequency was less than 1.5 times over the noise in the initial normal breathing; and 3) the average phase differences between and or and exceeds 1.5 box lengths from both the upper and lower quartile of the box and whisker plot (43). This study was powered with 80% power to detect a difference in CA between participant groups. We evaluated group average differences in amplitude ratios and phase of the hemodynamic signals and tissue oxygen saturation based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (with MATLAB, blindly, without prior knowledge of the participant groups evaluated), for which we report the corresponding z-statistic Wilcoxon rank-sum test and its significance value (p<0.05).

Mathematical Hemodynamic Model

In addition to evaluating differences in the amplitude ratio and phase of the hemodynamic signals, we applied a mathematical hemodynamic model (31,35,44) to explain the experimentally acquired frequency spectra (i.e., shaded area in Figure S3 contains all spectra for , , , and ). Briefly, the model describes amplitude and phase relationships of hemoglobin concentration changes as a function of cerebral blood flow, cerebral blood volume (CBV), and metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) changes. A detailed description of the model is reported in the Appendix A1 and elsewhere (31). When fit to experimental data, this model yields important output parameters, including CA efficiency, blood transit times, and blood volume ratios in different vascular compartments.

The model has 14 parameters, and we applied the same assumptions as in Fantini et al. (31) to reduce the number of unknown parameters. Using some values as inputs from Table 2 in Fantini et al. (31), we set the following parameters in the model to , , ctHb, and to values shown in Table 2 of this study. Using a built-in curve fitting (function ‘lsqcurvefit’ in MATLAB), we fit the group averaged frequency spectra of amplitude ratios and phase delays to the model equations. The group averages are based on averaging all data points over both optical probes after noise rejection and splitting the data into two participant groups, healthy controls and patients with SCD. A sub-analysis is provided in the Appendix to show the results from SCD-directed therapies. The fit was used to calculate five unknown parameters, specifically the capillary transit time, , venous transit time, , inverse modified Grubb’s exponent, k, CA cut-off frequency, , and the rate constant of oxygen diffusion, . Table 3 summarized the upper and lower bounds of the parameters based on previously reported values (35). Seventy-six initial guesses were randomized within the bounded parameters and used to determine the parameters’ fits. We evaluated group average differences in the parameters based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (p<0.05), blindly, without prior knowledge of the participant groups evaluated. We excluded all unknown parameter values that were zero, a value that is not physiological and instead presents a local minimum in the numerical model algorithm.

Table 2. Summary of key input model parameters used to derive quantitative predictions of the mathematical hemodynamic model.

The summary of input values are reported for the model based on the variable to each participant group. The vascular compartments are represented into three components being (a) contributions from arterial components, (c) contributions from capillary components, and (v) contributions from venous components.

| Physiological Characteristics | Arterial Cerebral Blood Volume, (ml/100g tissue) | Capillary Cerebral Blood Volume, (ml/100g tissue) | Venous Cerebral Blood Volume, (ml/100g tissue) | Fåhraeus Factor, | Arterial Saturation, (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Controls | 0.0075 | 0.0100 | 0.0075 | 0.80 | 98.00 |

| SCD Patients | 0.0075 | 0.0100 | 0.0075 | 0.80 | 98.00 |

Table 3. Upper and lower bounds of parameters of the mathematical hemodynamic model.

We assumed these parameters are set to the arterial saturation, , and Fåhraeus factor, . The limits for blood transit times in the capillaries were set ( ranged from 0.4 to 2.0 seconds) to require venous saturation levels between 32 and 71% for healthy controls (35). The autoregulation cutoff frequency was limited to no autoregulation, 0 Hz, and normal autoregulation, 0.15 Hz. The inverse modified Grubb’s exponent ranged between 1.50 and 5.00 based on literature (47,48,80,81). The vascular compartments represent three components being (a) contributions from arterial components, (c) contributions from capillary components, and (v) contributions from venous components.

| (s) | (s) | (Hz) | (s−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bounds | 0.40 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.50 | 0.50 |

| Upper Bounds | 2.00 | 10.00 | 0.15 | 5.00 | 0.85 |

RESULTS

Cerebral Hemodynamic Measurements of Small Vessel Disease with NIRS

We found that patients with SCD result in slower blood transit times, higher autoregulation efficiency and lower compartment blood volume ratios from healthy controls calculated from the hemodynamic model using NIRS-measured phase latencies from the prefrontal cortex. We reported the demographics and characteristics of the study cohort, including the mean age (± S.D.), race, hemoglobin, sex, and genotype of all participants in the study (Table 1). We only reported the education and complete blood count of patients with SCD. As a result of paced breathing, we set out to explore the NIRS-derived amplitude ratio and phase differences from the hemodynamic signals of the prefrontal cortex for each participant group (Figure 3 and Table S1). NIRS measurements that pass the exclusion criteria at each paced breathing frequency were labeled, demonstrating coherent hemodynamics and reliability in our measurements. Three patients with SCD were excluded from amplitude ratio and phase difference calculations based on the exclusion criteria. Here, we report the significant differences from the amplitude ratio and phase calculations; the remaining calculations were not significant (Figure 3 and Table S1).

Table 1. Population Characteristics of participants in the study.

| Characteristics | Healthy Controls (n = 14) | SCD Patients (n = 13) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.70 ± 10.10 | 40.60 ± 12.70 |

| Race | 14 African Americans |

13 African Americans |

| Education (years) | - | 12.15 (1.46) |

| Hemoglobin, ctHB (g/dL) | 13.50 ± 1.20 | 9.90 ± 2.56 |

| Sex, (% male) | 8 (57%) | 9 (69%) |

| Phenotype | 13 AA/1AS | 9 SS, 3 SC, 1 β+ |

| Hematocrit (%) | - | 30.23 ± 3.83 |

| Mean corpuscular volume | - | 84.94 ± 31.20 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin | - | 32.93 ± 6.78 |

| White Blood Cell (103/uL) | - | 18.04 ± 28.19 |

| Platelets (109/uL) | - | 263.59 ± 235.46 |

| Red cell distribution width (%) | - | 16.32 ± 6.13 |

| Reticulocytes (%) | - | 12.05 ± 29.79 |

| Fetal hemoglobin | - | 8.40 ± 8.40 |

| % S Hemoglobin | - | 47.87 ± 21.05 |

Figure 3.

NIRS experimental measurements of prefrontal cortex with box and half violin plots of (A) phase differences between and , , (B) amplitude ratio, , (C) phase differences between and , , and (D) amplitude ratio of the NIRS experimental measurements in all patients with SCD (n=13, sex = 69% male, blue) and healthy controls (n=14, sex = 57% male, grey). The half violin plots represent the density data distribution within each group. The horizontal line in each box represents the median measurement in the sample size of each group and solid lines represent the lower and upper quartiles. The data shown represented the group average and averaged across both optical probe locations.

All participant groups had non-zero phase differences, (Figure 3(A), Figure S1(A)). Based on previous findings, this indicates contributions of CBV and cerebral blood flow changes (31), with an expected relationship between in the brain of ~180° (31,45). In healthy controls, the average phase differences in were between −200° to −240° for the different paced breathing frequencies. A greater average phase difference in (mean range: −320° to −340°) was found in all patients with SCD. Further analysis showed that patients without SCD-directed therapies had an even greater difference (mean range: −340° to −350°), while patients with SCD-directed therapies had a lesser difference (mean range: −265° to −280°).

Phase differences in are most impacted by the capillary and venous blood volume fractions and CA cutoff frequency with an expected in-phase relation between in the brain of ~0° (31). We observed negative phase differences in as the paced breathing frequency increased, indicating that lags in each participant group. Patients receiving SCD-directed therapies had a significantly lower difference in compared to healthy controls at 0.125 Hz (p < 0.05). Those receiving SCD-directed therapies also had a significantly higher difference in compared to patients not receiving SCD-directed therapies at 0.125 Hz (p < 0.05, Figure S1(C)).

All participant groups had a positive amplitude ratio, , where is most impacted by capillary and venous blood volume fractions and a large modified Grubb’s exponent according to previous findings (31) (Figure 3(B)). The mean amplitude ratio was significantly higher in patients with SCD compared to healthy controls at 0.1 Hz (z = 2.22, p < 0.05) and 0.125 Hz (z= 2.24, p < 0.05, Figure 3(B)). The mean amplitude ratio was significantly higher in patients on SCD-directed therapies compared to healthy controls at 0.125 Hz (p < 0.05, Figure S1(B)). Healthy controls had increasing with increasing paced breathing due to shorter blood transit times and a significantly larger inverse of the modified Grubb’s exponent (4.88 ± 0.16, p < 0.0001, Table 4) to patients with SCD (2.69 ± 0.67), where nine of 13 datasets for patients with SCD showed a reduced amplitude ratio with increasing paced breathing (Figure 4(D)). Furthermore, patients receiving SCD-directed therapies had shorter blood transit times and a significantly larger inverse of the modified Grubb’s exponent (4.05 ± 1.15, p < 0.0001) compared to patients not receiving SCD-directed therapies (2.41 ± 0.60, p < 0.0001, Table S1).

Table 4. Results used to derive quantitative predictions of the key output model parameters to the mathematical hemodynamic model.

The results reported are based on the mean and standard deviation of the variable to each participant group. The vascular compartments are represented into three components being (a) contributions from arterial components, (c) contributions from capillary components, and (v) contributions from venous components. The results shown are the mean and standard deviation of the acceptable solutions. The differences in the parameters were statistically significant (p < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test) for , , , , , , and .

| Physiological Characteristics | Healthy Controls (n = 14) (Mean ± SD) | SCD Patients (n = 13) (Mean ± SD) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCD- HC | |||

| Capillary Saturation, (%) | 74.13 ± 7.00 | 51.61 ± 4.90 | < 0.0001 |

| Venous Saturation, (%) | 54.92 ± 11.48 | 23.10 ± 5.89 | < 0.0001 |

| Blood Transit Times in Capillaries, (s) | 0.71 ± 0.24 | 1.88 ± 0.14 | < 0.0001 |

| Blood Transit Times in Venous Compartments, (s) | 6.47 ± 3.14 | 6.49 ± 1.47 | 0.015 |

| Inverse of Modified Grubb’s Exponent, k | 4.88 ± 0.16 | 2.69 ± 0.67 | < 0.0001 |

| Autoregulation Cutoff Frequency, (Hz) | 0.02 ± 0.0052 | 0.016 ± 0.033 | < 0.0001 |

| Rate Constant of Oxygen Diffusion, (1/sec) | 0.76 ± 0.12 | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 0.020 |

Figure 4.

Summary of group averages of five fitting parameters for each participant group expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The fitted parameters were (A) blood transit time in the capillaries, , (B) blood transit time in venous, , (C) CA cutoff frequency, f(c), (D) inverse of modified Grubb’s exponent, k, and (E) rate constant of oxygen diffusion, α. The mean symbols are highlighting patients with all SCD (n=13, sex = 69% male, blue, circle) and healthy controls (n=14, sex = 57% male, grey, diamond) and the standard deviations are represented by the error bars. Values marked with an asterisk refer to a p-value of the Wilcoxon signed tanked tests (p<0.05).

The measured amplitude ratio was influenced by the venous blood transit times and CA cutoff frequency (Figure 3(D), Figure S1(D)). was significantly lower in patients receiving SCD-directed therapies compared to healthy controls at 0.1Hz (p < 0.05, Figure S1(D)) and 0.125 Hz (z = −2.37, p < 0.05). was also significantly lower in all patients with SCD compared to healthy controls at 0.125 Hz (z = −1.97, p < 0.05). Healthy controls had higher measured compared to the other participant groups due to shorter venous blood transit times (6.47 ± 3.14) compared to patients with SCD (6.49 ± 1.47, p < 0.05) and patients without SCD-directed therapies (7.27 ± 0.55, p < 0.05, Figure S1(B)).

Hemodynamic Model Fit to NIRS Data

Using the mathematical hemodynamic model (31,46), we calculated blood transit times, and , CA cutoff frequency, , and blood volume-to-flow ratio, k, within each participant group. The output of the model fit to the group average NIRS spectra (Figure 4). A total of 76 different initial guesses were used for the fits, which were generated randomly within a range of values (Table 3). We found 76 solutions for the five parameters and the error bars correspond to the standard deviation over all solutions (Figure 4, Figure S2). We found that the group averaged blood transit time in the capillaries, , (1.88 ± 0.14s) was significantly larger in patients with SCD compared to healthy controls (0.71 ± 0.24s, p < 0.0001), indicating reduced blood flow velocity in the capillaries. In addition, we found the group averaged inverse of the modified Grubb’s exponent, k, a measure of global blood volume to local blood flow, to be significantly lower in patients (2.69 ± 0.67) compared to controls (4.88 ± 0.16, p < 0.0001) and to be within the reported healthy control range (47,48). The group averaged CA cutoff frequency was slower in all patients with SCD (0.016 ± 0.33 Hz) compared to patients without SCD-directed therapies (0.046 ± 0.022 Hz, p < 0.0001, Figure S2) and controls (0.02 ± 0.0052 Hz, p < 0.0001, Table 4). All other parameters were significantly different between groups, except for the rate constant of oxygen diffusion in SCD-directed therapies compared to controls. We showed the fits using the solutions in Figure 4 applied to the NIRS spectra (Figure S3) and the model parameter values (Table 4).

Cerebral Tissue Oxygen Saturation Measurements from NIRS Data

We measured tissue oxygen saturation of hemoglobin, StO2, in addition to dynamic changes during paced breathing. This value was computed from the experimental NIRS measurements from the prefrontal cortex in each participant group. We found reduced mean StO2 in patients with SCD, including patients with and patients without SCD-directed therapies, in comparison to healthy controls (Figure 5, Figure S4 and Table 5). We found that patients with SCD HbSC had a significantly different mean StO2, compared to healthy controls and patients with SCD HbSS or β-thalassemia (p <0.05, Figure S4). No significant difference was found between the groups (p=0.95). This finding supports the use of our mathematical model, as the absolute StO2 in this sampled group may not be a sensitive metric alone for the given sample size.

Figure 5.

Experimental tissue oxygen saturation from the prefrontal cortex. Box plot showing tissue oxygen saturation for each participant group using NIRS measurements from the prefrontal cortex. Individual scatter points overlay the box plot, highlighting patients with SCD (n=13, sex = 69% male, blue, circle) and healthy controls (n=14, sex = 57% male, grey, diamond). The horizontal line in each box represents the median measurement in the sample size of each group and solid lines represent the lower and upper quartiles. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test (p<0.05) was used to determine the significant difference between each participant group.

Table 5. Experimental tissue oxygen saturation from the prefrontal cortex (in Percent (%)).

| Healthy Controls (n = 13) | SCD Patients (n = 11) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Oxygen Saturation Measurements (%) (Mean ± SD) | 66.1 ± 4.7 | 65.7± 6.0 | 0.95 |

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that paced breathing-induced changes measured via NIRS can be used to monitor CA and cerebral small vessel disease in adults with SCD and to differentiate hemodynamics between SCD and healthy controls. We found that adult patients with SCD, with a mean age of 40 years, have altered blood transit times in the microvasculature, indicating reduced blood flow velocity from vaso-occlusion and lowered tissue oxygen saturation, which supports the findings in the literature using cerebral oximetry (49–51). The associated group averages presented differences across each participant group — especially the blood transit times in capillaries and venous compartments, the relationship of blood volume to blood flow, and oxygen diffusion rate — and may be used as indicators of cerebral small vessel disease in adult patients with SCD.

Our study illustrates the appeal and utility of NIRS to monitor local microvascular vasodilation and vasoconstriction induced by MAP oscillations by using NIRS measurements combined with a mathematical hemodynamic model to estimate CA in terms of a high pass filter cut-off frequency. Our study involved patients with SCD, which means that the recommendations from the Cerebrovascular Research Network regarding the high-pass filter cut-off frequency do not apply to our findings due to the vascular differences associated with this condition (52). Furthermore, by inducing controlled MAP oscillations through paced breathing, we could harness NIRS to directly determine blood transit times in regional microvasculature and oxygen saturation within all vascular compartments. Using the hemodynamic model fitting to the frequency spectra, we observed longer blood transit times in adults with SCD compared to age-matched, healthy controls (0.71 ± 0.24s vs. 1.88 ± 0.14s, p < 0.0001, Table 4). Longer blood transit times in the capillaries correspond to slower blood velocities, reduced cerebral blood flow in the microvasculature within the prefrontal cortex, and reduced capillary saturation; so, we hypothesized that longer transit times would result in lower oxygen saturation in our adult cohort with SCD also found in literature (53,54). As expected, we found that the group averaged saturation in the capillaries was significantly different between healthy controls (74.13 ± 7.00%), patients receiving SCD-directed therapies (50.00 ± 3.02%, p < 0.0001, Table S1), and all patients with SCD (51.61 ± 4.90%, p < 0.0001, Table 4). The lower capillary saturation in SCD is similar to that reported for patients on hemodialysis using the hemodynamic model (54.65%), which were significantly lower than in healthy controls (28). Our model-derived capillary transit times align with direct measurements using indicator dilution techniques (55) and dynamic contrast optical coherence tomography for laminar transit time mapping (56), which highlight capillary transit time impacts oxygen extraction (55,57). Also, healthy controls had trends consistent with those reported in the literature (35), while patients with SCD had the opposite trend and exhibited decreased amplitude ratio with increasing breathing frequency.

In contrast to our findings, which we imaged the microvasculature in the prefrontal cortex, other studies report that arterial cerebral blood flow in the middle cerebral artery— supplying the lateral frontal lobe and primary motor and sensory cortices— was higher at rest and with dynamic changes in adults with SCD (58). Other studies also reported higher resting microvascular cerebral blood flow measured with diffuse correlation spectroscopy (59) or MRI in children and adolescents with SCD as compared to the healthy control group (60). The pathophysiology of SCD is complex, with patients at risk of stroke and small vessel disease (8). While there is a substantial amount of literature reporting on cerebral blood flow in children with SCD, there is a notable lack of evidence reporting cerebral blood flow in middle-aged adults with SCD. Adults with small vessel disease (and without SCD) exhibit lower cerebral blood flow, which is linked to a greater WMH burden and may support our findings (61). We did not screen for the presence of silent cerebral infarcts with MRI in our study, and so we cannot discount the possibility that a high prevalence and density of silent cerebral infarcts in our adult cohort may have accounted for the finding of lower cerebral blood flow, in keeping with other studies (62–65).

Blood transit times help conceptualize how the hemoglobin concentrations, measured by changes in phase latencies, impact tissue oxygenation. It is important to note that the phase delay refers to the temporal difference between two hemoglobin signals, while the blood transit times represent the duration of erythrocyte passage through the capillary network. These are related but distinct concepts– phase delay emerges from vascular resistance and compliance interactions, while transit time is the physical manifestation of flow dynamics. We found that the capillary and venous transit times were significantly shorter in healthy controls than in adult patients with SCD, comparable to prior evidence in other vascular diseases (35,66). In SCD, hemoglobin S causes rigid erythrocytes, leading to increased vascular resistance and reduced compliance due to endothelial dysfunction, which would affect blood flow dynamics. Consequently, larger erythrocytes show capillary shunting and may lead to longer transit times compared to healthy controls, depending on the specific vascular bed (55). Similarly, the phase delays in healthy controls are comparable to prior evidence for healthy controls with intact CA (28,31,67). Our results also support prior evidence that larger Arg(D)−Arg(O) indicates changes in CA in patients with a history of cerebrovascular disease compared to healthy controls (67).

We found that patients with SCD-directed therapies had a slightly higher group averaged cerebral StO2, which was consistent with another study on patients with SCD treated with hydroxyurea (49,68) (Figure 5 and Table 5). However, the differences between the groups were not significant, possibly due to the small sample size. Our findings support previous evidence that indicates cerebral StO2 at rest is significantly lower in patients with SCD compared to healthy controls (50,51,68–78), which is also observed in small vessel disease (79). From our study, we were not able to determine the direct impact of anemia; however, we found that patients with HbSC had higher cerebral StO2 (72.3 ± 4.3, n=3) compared to those patients with HbSS or β-thalassemia (63.3 ± 4.5, n=8, p<0.05, Figure S4, Table S2). There were no sex differences within either group (SCD female vs male; p =0.46; HC female vs male: p =1.00). There were no sex differences between the groups (SCD female vs HC female; p =0.56; SCD male vs HC male: p =0.35). This finding supports the use of our mathematical model, as the absolute StO2 in this current sampled group may not be a sensitive metric alone for the given sample size. Larger studies will need to be conducted to fully capture the spectrum of phenotypic and sex variability in SCD.

There are limitations to our study that will be explored in future research regarding potential confounding factors in our experimental protocol and group comparison. Participants needed to refrain from activities that could introduce such confounding variables into our measurements, and while there were robust instructions and exclusion criteria, we do not know if participants consumed caffeine or smoked, which might significantly influence the results. We assume that end-tidal CO2 remains constant in our model, yet individual variations may occur experimentally. Future studies should take these variations into account to prevent them from being confounding factors. Additionally, while sex was not deemed significant in this study, it could be a confounder in the analysis and should be appropriately powered in future studies with larger study cohorts.

Conclusion

In summary, we have found that NIRS is a useful technology to detect small vessel disease in patients with SCD. In addition, we have applied a novel hemodynamic method to our NIRS measurements. From this model, we derived and determined three important physiological parameters that allowed us to assess the impact of SCD on microvascular oscillations and function in adults compared to healthy controls: the blood transit times in capillaries and venous compartments, the relationship of blood volume to blood flow, and oxygen diffusion rate.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Fig. S1: https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/29115710.

Supplemental Fig. S2: https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/29115731.

Supplemental Fig. S3: https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/29115800.

Supplemental Fig. S4: https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/29137625.

Supplemental Table S1: https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/29137640.

Supplemental Table S2: https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/29142869.

GRANTS

This research is supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant no. R01- HL127107 and by the University of Pittsburgh’s CTSI REAL (REsearch Across the Lifespan) Pilot Program which was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant no. UL1TR001857. This research is also supported by Carnegie Mellon University’s Presidential Postdoctoral Fellowship.

APPENDIX

Details of the Mathematical Hemodynamic Model

The model separates the cerebral microvasculature into vascular compartments represented by the superscripts in parentheses (a), (c), and (v), representing the arterial, capillary, and venous, respectively. In the frequency-domain, the model provides a theoretical framework to represent the phasors of tissue concentrations of , , and as functions of , , and , phasors that describe sinusoidal oscillations in CBV, CBF, and CMRO2, respectively (31,35,44)

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where are complex transfer functions for the resistor-capacitor (RC) filters — low-pass in capillaries , low-pass in the venous compartment , and high-pass for the CA efficiency. These RC filters are described in terms of transit time in capillaries , transit time in venules , hemoglobin concentration in blood ctHb, and autoregulation cutoff frequency . The capillary and venous saturations are given by and , where alpha is the rate constant of oxygen diffusion. The high-pass RC filter component with autoregulation cutoff frequency, , is given as follows:

| (4) |

The relationship between and is written as,

| (5) |

where k is the inverse of the modified Grubb exponent (48).

Footnotes

DISCLAIMERS

None

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guo ZN, Xing Y, Wang S, Ma H, Liu J, Yang Y. Characteristics of dynamic cerebral autoregulation in cerebral small vessel disease: Diffuse and sustained. 2015;5(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams RJ, McKie VC, Hsu L, Files B, Vichinsky E, Pegelow C, et al. Prevention of a First Stroke by Transfusions in Children with Sickle Cell Anemia and Abnormal Results on Transcranial Doppler Ultrasonography . New England Journal of Medicine. 1998. Jul 2;339(1):5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeBaun MR, Gordon M, McKinstry RC, Noetzel MJ, White DA, Sarnaik SA, et al. Controlled Trial of Transfusions for Silent Cerebral Infarcts in Sickle Cell Anemia. 2014. Aug;371(8):699–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stotesbury H, Kawadler JM, Saunders DE, Kirkham FJ. MRI detection of brain abnormality in sickle cell disease. 10.1080/1747408620211893687. 2021;14(5):473–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeBaun MR, Armstrong FD, McKinstry RC, Ware RE, Vichinsky E, Kirkham FJ. Silent cerebral infarcts: A review on a prevalent and progressive cause of neurologic injury in sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2012. May 17;119(20):4587–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeBaun MR, Kirkham FJ. Central nervous system complications and management in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2016. Feb 18;127(7):829–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manwani D, Frenette PS. Vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease: pathophysiology and novel targeted therapies. Hematology / the Education Program of the American Society of Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sundd Prithu, Gladwin Mark T., Novelli EM. Pathophysiology of Sickle Cell Disease. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease. 2019;14:263–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Østergaard L, Engedal TS, Moreton F, Hansen MB, Wardlaw JM, Dalkara T, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease: capillary pathways to stroke and cognitive decline. journals.sagepub.com. 2016. Feb 1;36(2):302–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brady K, Joshi B, Zweifel C, Smielewski P, Czosnyka M, Easley RB, et al. Real-time continuous monitoring of cerebral blood flow autoregulation using near-infrared spectroscopy in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Stroke. 2010. Sep;41(9):1951–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brady KM, Lee JK, Kibler KK, Easley RB, Koehler RC, Shaffner DH. Continuous Measurement of Autoregulation by Spontaneous Fluctuations in Cerebral Perfusion Pressure. Stroke. 2008. Sep;39(9):2531–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinn CT, Dowling MM. Cerebral tissue hemoglobin saturation in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2012. Nov 1;59(5):881–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aaslid R, Lindegaard KF, Sorteberg W, Nornes H. Cerebral autoregulation dynamics in humans. Stroke. 1989. Jan;20(1):45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brassard P, Labrecque L, Smirl JD, Tymko MM, Caldwell HG, Hoiland RL, et al. Losing the dogmatic view of cerebral autoregulation. Physiological Reports [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2025 Apr 15];9(15):e14982. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.14814/phy2.14982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diehl RR, Linden D, Lücke D, Berlit P, Lücke D, Berlit P. Phase relationship between cerebral blood flow velocity and blood pressure a clinical test of autoregulation. Stroke. 1995. Oct;26(10):1801–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kainerstorfer JM, Sassaroli A, Tgavalekos KT, Fantini S. Cerebral autoregulation in the microvasculature measured with near-infrared spectroscopy. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism [Internet]. 2015;35(6):959–66. Available from: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panerai RB. Transcranial Doppler for evaluation of cerebral autoregulation. Clinical Autonomic Research 2009 19:4. 2009. Apr 16;19(4):197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulson OB, Strandgaard S, Edvinsson L. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrovascular and brain metabolism reviews. 1990;2(2):161–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eames P, Blake M, … SDJ of N, 2002 undefined. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation and beat to beat blood pressure control are impaired in acute ischaemic stroke. jnnp.bmj.com. 2002;72:467–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mankovsky BN, Piolot R, Mankovsky OL, Ziegler D. Impairment of cerebral autoregulation in diabetic patients with cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy and orthostatic hypotension. Diabetic Medicine. 2003. Feb 1;20(2):119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rangel-Castilla L, Gasco J, Nauta HJW, Okonkwo DO, Robertson CS. Cerebral pressure autoregulation in traumatic brain injury. 2008. Oct 1 [cited 2025 Apr 15]; Available from: https://thejns.org/focus/view/journals/neurosurg-focus/25/4/article-pE7.xml [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Álvarez FJ, Segura T, Castellanos M, Leira R, Blanco M, Castillo J, et al. Cerebral hemodynamic reserve and early neurologic deterioration in acute ischemic stroke. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2004. Nov;24(11):1267–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Disu JDK, Abdelmohsen L, Mossazghi N, Meinert-Spyker E, Saber C, Xu J, et al. Dynamic Cerebral Autoregulation and Blood Pressure Oscillations Reveal the Severity of Autoregulatory Dysfunction in Sickle Cell Disease. Blood [Internet]. 2024. [cited 2025 Apr 16];144:3876. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006497124066345 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kainerstorfer JM, Sassaroli A, Fantini S. Optical oximetry of volume-oscillating vascular compartments: contributions from oscillatory blood flow. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2016. Mar 1;21(10):101408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reinhard M, Wehrle-Wieland E, Grabiak D, Roth M, Guschlbauer B, Timmer J, et al. Oscillatory cerebral hemodynamics-the macro- vs. microvascular level. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2006;250(1–2):103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tgavalekos KT, Kainerstorfer JM, Sassaroli A, Fantini S. Blood-pressure-induced oscillations of deoxy- and oxyhemoglobin concentrations are in-phase in the healthy breast and out-of-phase in the healthy brain. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2016;21(10):101410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood S, Fanta A, Dosunmu-Ogunbi A, Ruesch A, Jonassaint J, Huppert T, et al. Assessing Dynamic Cerebral Autoregulation in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and Paced Breathing. Blood [Internet]. 2020. Nov 5 [cited 2023 Nov 4];136(Supplement 1):57–8. Available from: https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/136/Supplement%201/57/470249/Assessing-Dynamic-Cerebral-Autoregulation-in [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierro ML, Kainerstorfer JM, Civiletto A, Weiner DE, Sassaroli A, Hallacoglu B, et al. Reduced speed of microvascular blood flow in hemodialysis patients versus healthy controls: a coherent hemodynamics spectroscopy study. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2014;19(2):026005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kainerstorfer JM, Sassaroli A, Tgavalekos KT, Fantini S. Cerebral autoregulation in the microvasculature measured with near-infrared spectroscopy. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2015;35(6):959–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kainerstorfer JM, Sassaroli A, Pierro ML, Hallacoglu B, Fantini S. Coherent Hemodynamics Spectroscopy Based on a Paced Breathing Paradigm — Revisited. Journal of Innovative Optical Health Sciences. 2013; [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fantini S. Dynamic model for the tissue concentration and oxygen saturation of hemoglobin in relation to blood volume, flow velocity, and oxygen consumption: Implications for functional neuroimaging and coherent hemodynamics spectroscopy (CHS). NeuroImage. 2014. Jan 15;85:202–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joseph CN, Porta C, Casucci G, Casiraghi N, Maffeis M, Rossi M, et al. Slow Breathing Improves Arterial Baroreflex Sensitivity and Decreases Blood Pressure in Essential Hypertension. Hypertension [Internet]. 2005. Oct [cited 2025 Apr 16];46(4):714–8. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.hyp.0000179581.68566.7d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russo MA, Santarelli DM, O’Rourke D. The physiological effects of slow breathing in the healthy human. Breathe (Sheff) [Internet]. 2017. Dec [cited 2025 Apr 16];13(4):298–309. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5709795/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sassaroli A, Kainerstorfer J, Pierro ML, Hallacoglu B, Fantini S. Optical Study of the Cerebral Microcirculation with Coherent Hemodynamics Spectroscopy: a Paced Breathing Protocol. In 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kainerstorfer JM, Sassaroli A, Hallacoglu B, Pierro ML, Fantini S. Practical steps for applying a new dynamic model to near-infrared spectroscopy measurements of hemodynamic oscillations and transient changes: implications for cerebrovascular and functional brain studies. Academic radiology. 2014. Feb;21(2):185–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ballas SK, Lieff S, Benjamin LJ, Dampier CD, Heeney MM, Hoppe C, et al. Definitions of the phenotypic manifestations of sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2010. Jan;85(1):6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kato GJ. New Insights into Sickle Cell Disease: Mechanisms and Investigational Therapies. Current opinion in hematology. 2016;23(3):224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fantini S, Franceschini MA, Gratton E. Semi-infinite-geometry boundary problem for light migration in highly scattering media: a frequency-domain study in the diffusion approximation. Journal of the Optical Society of America B [Internet]. 1994. [cited 2025 Apr 16];11(10):2128–38. Available from: https://opg.optica.org/abstract.cfm?uri=josab-11-10-2128 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fantini S, Hueber D, Franceschini MA, Gratton E, Rosenfeld W, Stubblefield PG, et al. Non-invasive optical monitoring of the newborn piglet brain using continuous-wave and frequency-domain spectroscopy. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 1999;44(6):1543–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sassaroli A, Biology SFP in M&, 2004 undefined. Comment on the modified Beer–Lambert law for scattering media. iopscience.iop.org. 2004; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parks T, McClellan J. Chebyshev Approximation for Nonrecursive Digital Filters with Linear Phase. IEEE Transactions on Circuit Theory [Internet]. 1972. Mar [cited 2025 Apr 16];19(2):189–94. Available from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/1083419 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barens P. CircStat: a MATLAB toolbox for circular statistics. Journal of Statistical Software. 2009;31(10):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinhard M, Wehrle-Wieland E, Grabiak D, Roth M, Guschlbauer B, Timmer J, et al. Oscillatory cerebral hemodynamics-the macro- vs. microvascular level. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2006;250(1–2):103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fantini S. A new hemodynamic model shows that temporal perturbations of cerebral blood flow and metabolic rate of oxygen cannot be measured individually using functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Physiol Meas. 2014;35:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fantini S. A haemodynamic model for the physiological interpretation of in vivo measurements of the concentration and oxygen saturation of haemoglobin. Physics in Medicine & Biology [Internet]. 2002. [cited 2025 Apr 16];47(18):N249. Available from: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0031-9155/47/18/402/meta?casa_token=cNt5C3iBjJcAAAAA:WGEALQgbJVkmW-PTjXWzfEzm1IPYzl9ISP2f1LLJzy_NgqxoL86PcpDHs20tjOfTPqHycoYk05FgCDfll4pehSLRWgs [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kainerstorfer JM, Sassaroli A, Tgavalekos KT, Fantini S. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation measured with coherent hemodynamics spectroscopy (CHS). In: Optical Tomography and Spectroscopy of Tissue XI. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kida I, Rothman DL, Hyder F. Dynamics of changes in blood flow, volume, and oxygenation: Implications for dynamic functional magnetic resonance imaging calibration. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2007;27(4):690–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leung TS, Tachtsidis I, Tisdall MM, Pritchard C, Smith M, Elwell CE. Estimating a modified Grubb’s exponent in healthy human brains with near infrared spectroscopy and transcranial Doppler. Physiological Measurement. 2009;30(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karkoska K, Quinn CT, Niss O, Pfeiffer A, Dong M, Vinks AA, et al. Hydroyxurea improves cerebral oxygen saturation in children with sickle cell anemia. American Journal of Hematology. 2021. May 1;96(5):538–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Charlot K, Antoine-Jonville S, Moeckesch B, Jumet S, Romana M, Waltz X, et al. Cerebral and muscle microvascular oxygenation in children with sickle cell disease: Influence of hematology, hemorheology and vasomotion. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2017;65(January):23–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nahavandi M, Tavakkoli F, Hasan SP, Wyche MQ, Castro O. Cerebral oximetry in patients with sickle cell disease. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;34(2):143–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Panerai RB, Brassard P, Burma JS, Castro P, Claassen JA, van Lieshout JJ, et al. Transfer function analysis of dynamic cerebral autoregulation: A CARNet white paper 2022 update. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab [Internet]. 2023. Jan [cited 2025 Apr 15];43(1):3–25. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9875346/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vargas FF, Blackshear GL. Vascular resistance and transit time of sickle red blood cells. Blood Cells [Internet]. 1982. [cited 2025 Apr 16];8(1):139–45. Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/med/7115971 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeBeer T, Jordan LC, Waddle S, Lee C, Patel NJ, Garza M, et al. Red cell exchange transfusions increase cerebral capillary transit times and may alter oxygen extraction in sickle cell disease. NMR in Biomedicine [Internet]. 2023. May [cited 2025 Apr 16];36(5):e4889. Available from: https://analyticalsciencejournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/nbm.4889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Østergaard L. Blood flow, capillary transit times, and tissue oxygenation: The centennial of capillary recruitment. Journal of Applied Physiology [Internet]. 2020. Dec;129(6):1413–21. Available from: http://www.jap.org [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Merkle CW, Srinivasan VJ. Laminar microvascular transit time distribution in the mouse somatosensory cortex revealed by Dynamic Contrast Optical Coherence Tomography. Neuroimage [Internet]. 2016. Jan 15 [cited 2025 May 19];125:350–62. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4691378/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lücker A, Secomb TW, Barrett MJP, Weber B, Jenny P. The Relation Between Capillary Transit Times and Hemoglobin Saturation Heterogeneity. Part 2: Capillary Networks. Front Physiol [Internet]. 2018. Sep 21 [cited 2025 May 19];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2018.01296/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim YS, Nur E, van Beers EJ, Truijen J, Davis SCAT, Biemond BJ, et al. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation in homozygous Sickle cell disease. Stroke. 2009. Mar;40(3):808–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee SY, Cowdrick KR, Sanders B, Sathialingam E, McCracken CE, Lam WA, et al. Noninvasive optical assessment of resting-state cerebral blood flow in children with sickle cell disease. 10.1117/1NPh63035006. 2019. Aug 19;6(3):035006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bush AM, Borzage MT, Choi S, Václavů L, Tamrazi B, Nederveen AJ, et al. Determinants of resting cerebral blood flow in sickle cell disease. American journal of hematology. 2016. Sep 1;91(9):912–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stewart CR, Stringer MS, Shi Y, Thrippleton MJ, Wardlaw JM. Associations between white matter hyperintensity burden, cerebral blood flow and transit time in small vessel disease: an updated meta-analysis. Frontiers in neurology [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2025 May 19];12:647848. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2021.647848/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ford AL, Ragan DK, Fellah S, Binkley MM, Fields ME, Guilliams KP, et al. Silent infarcts in sickle cell disease occur in the border zone region and are associated with low cerebral blood flow. Blood. 2018. Oct 18;132(16):1714–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adams RJ. TCD in sickle cell disease: An important and useful test. Pediatric Radiology. 2005. Feb 10;35(3):229–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arba F, Mair G, Carpenter T, Sakka E, Sandercock PAG, Lindley RI, et al. Cerebral White Matter Hypoperfusion Increases with Small-Vessel Disease Burden. Data From the Third International Stroke Trial. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2017. Jul 1;26(7):1506–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stewart CR, Stringer MS, Shi Y, Thrippleton MJ, Wardlaw JM. Associations Between White Matter Hyperintensity Burden, Cerebral Blood Flow and Transit Time in Small Vessel Disease: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Neurology. 2021. May 4;12:621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fraser CD, Brady KM, Rhee CJ, Easley RB, Kibler K, Smielewski P, et al. The frequency response of cerebral autoregulation. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2013. Jul 1;115(1):52–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reinhard M, M ller T, Guschlbauer B, Timmer J, Hetzel A. Transfer function analysis for clinical evaluation of dynamic cerebral autoregulation a comparison between spontaneous and respiratory-induced oscillations. Physiological Measurement. 2003. Feb 1;24(1):27–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tavakkoli F, Nahavandi M, Wyche MQ, Castro O. Effects of hydroxyurea treatment on cerebral oxygenation in adult patients with sickle cell disease: An open-label pilot study. Clinical Therapeutics. 2005;27(7):1083–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barriteau CM, Chiu A, Rodeghier M, Liem RI. Cerebral and skeletal muscle tissue oxygenation during exercise challenge in children and young adults with sickle cell anaemia. Br J Haematol [Internet]. 2022. Jan [cited 2025 Apr 16];196(1):179–82. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8702443/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mostashari G, Quang T, Parker HE, Hill M, Parekh D, Keel A, et al. Exploring near infrared spectroscopy as a tool for monitoring tissue hemodynamics for patients with sickle cell disease. Blood [Internet]. 2023. [cited 2025 Apr 16];142:3862. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006497123104642 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nahavandi M, Nichols JP, Hassan M, Gandjbakhche A, Kato GJ. Near-infrared spectra absorbance of blood from sickle cell patients and normal individuals. Hematology. 2009;14(1):46–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.ORTIZ FO, ALDRICH TK, NAGEL RL, BENJAMIN LJ . Accuracy of Pulse Oximetry in Sickle Cell Disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1999. Feb;159(2):447–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Parachalil Gopalan B, Quang T, Lizarralde-Iragorri MA, Lovins D, Cullinane A, Dulau-Florea A, et al. Incorporating point-of-care technologies to assess treatment response in sickle cell disease. Blood Vessels, Thrombosis & Hemostasis [Internet]. 2024. [cited 2025 Apr 16];1(2):100009. Available from: https://ashpublications.org/bloodvth/article/1/2/100009/516158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Raj A, Bertolone SJ, Mangold S, Edmonds HL. Assessment of Cerebral Tissue Oxygenation in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease: Effect of Transfusion Therapy. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2004;26(5):279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Saber C, Meinert-Spyker E, Abdelmohsen L, Philips BJ, Disu JDK, Mossazghi N, et al. Higher Hemoglobin Level Correlates with Increased Tissue Oxygenation in a Comprehensive Profile of Hemorheology in Sickle Cell Disease. Blood [Internet]. 2024. [cited 2025 Apr 16];144:294. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006497124030416 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Waltz X, Pichon A, Lemonne N, Mougenel D, Lalanne-Mistrih ML, Lamarre Y, et al. Normal Muscle Oxygen Consumption and Fatigability in Sickle Cell Patients Despite Reduced Microvascular Oxygenation and Hemorheological Abnormalities. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Waltz X, Hardy-Dessources M, Lemonne N. Is there a relationship betweenthe hematocrit-to-viscosity ratioand microvascular oxygenation in brain and muscle? 2013; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zuzak KJ, Gladwin MT, Cannon RO, Levin IW. Imaging hemoglobin oxygen saturation in sickle cell disease patients using noninvasive visible reflectance hyperspectral techniques: Effects of nitric oxide. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2003;285(3 54–3):1183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Giacalone G, Zanoletti M, Re R, Contini D, Spinelli L, Torricelli A, et al. Time-Domain Near-Infrared Spectroscopy in Subjects with Asymptomatic Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Applied Sciences [Internet]. 2021. Jan [cited 2025 May 19];11(5):2407. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/11/5/2407 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grubb RL, Raichle ME, Eichling JO, Ter-Pogossian MM. The effects of changes in paco2on cerebral blood volume, blood flow, and vascular mean transit time. Stroke. 1974;5(5):630–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mandeville JB, Marota JJA, Ayata C, Moskowitz MA, Weisskoff RM, Rosen BR. MRI measurement of the temporal evolution of relative CMRO2 during rat forepaw stimulation. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1999;42(5):944–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.