Abstract

Cell penetrating peptides conjugated to delivery vehicles, such as nanoparticles or antibodies, can enhance the cytosolic delivery of macromolecules. The present study examines the effects of conjugation to cell penetrating and endosomal escape peptides (i.e. TAT, GALA, and H6CM18) on the pharmacokinetics and distribution of an anti-carcinoembryonic antigen “catch-and-release” monoclonal antibody, 10H6, in a murine model of colorectal cancer. GALA and TAT were conjugated to 10H6 using Solulink® technology that allowed evaluation of peptide-to-antibody ratio by UV spectroscopy. H6CM18 was conjugated to either NHS or maleimide modified 10H6 using an azide modified valine-citrulline linker and copper-free click chemistry. Unmodified and peptide-conjugated 10H6 preparations were administered intravenously at 6.67 nmol/kg to mice bearing MC38CEA+ tumors. Unconjugated 10H6 demonstrated clearance of 19.9 ± 1.36 mL/day/kg, with an apparent volume of distribution of 62.4 ± 7.78 mL/kg. All antibody-peptide conjugates exhibited significantly decreased plasma and tissue exposure, increased plasma clearance, and increased distribution volume. Examination of tissue-to-plasma exposure ratios showed an enhanced selectivity of 10H6-TAT for GI tract (+25%), kidney (+24%), liver (+38%), muscle (+3%), and spleen (+33%). 10H6-GALA and 10H6-H6CM18 conjugates demonstrated decreased exposure in all tissues, relative to unmodified 10H6. All conjugates demonstrated decreased tumor exposure and selectivity; however, differences in tumor selectivity between 10H6 and 10H6-H6CM18 (maleimide) were not statistically significant. Relationships between predicted peptide conjugate pI and pharmacokinetic parameters were bell-shaped, where pI values around 6.8–7 exhibit the slowest plasma clearance and smallest distribution volume. The data and analyses presented in this work may guide future efforts to develop immunoconjugates with cell penetrating and endosomal escape peptides.

Keywords: Cell Penetrating Peptide, Endosomal Escape Peptide, Antibodies, Catch-and-Release, Immunoconjugates, Pharmacokinetics

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Cell penetrating peptides (CPP) are natural or synthetic peptides that interact with plasma membranes to facilitate the cellular uptake of conjugated moieties. Application of CPPs has led to breakthroughs in cytosolic delivery of macromolecules (e.g. DNA, siRNA, RNA, proteins, etc.) in cell culture with potential application for a number of medical conditions, including cancer.1–7 The first described CPP, TAT, which is a cationic peptide isolated from the HIV-1 transactivator of transcription protein, demonstrated utility in facilitating the translocation of protein payloads (e.g. β-galactosidase, HRP, RNase A, and Pseudomonas Exotoxin A) into the cytosol of cells.8 Cell entry of TAT peptides is highly dependent on the basic amino acid residues, arginine and lysine, which interact with negatively charged phospholipid heads of plasma membranes.9, 10 TAT and other cationic peptides induce local lipid destabilization, translocate across the plasma membrane or potentially form toroidal pores, and passage into the cell.9, 11–14 Several studies demonstrated that TAT can be also transported into the cell by both caveolae- and clathrin-mediated endocytosis.15, 16 Although efficient in vitro, in vivo applications of TAT and other positively charged CPPs for macromolecular delivery have been limited due their small size, which leads to rapid elimination from plasma via renal filtration, and due to their propensity to increase the plasma clearance of conjugated proteins.17, 18

Endosomal escape peptides (EEPs) are a subset of CPPs with pH-sensitive characteristics that facilitate passage of macromolecules from the endosome through formation of pores and fusogenic or lytic activity.19, 20 EEPs identified from naturally produced proteins (e.g., hemagglutinin protein of the influenza virus21) or synthesized chemically (GALA peptide20), typically have sequences rich in histidine, glutamic acid, and aspartic acid. GALA has gained considerable interest within the drug delivery field and has demonstrated success in delivering a variety of macromolecular cargos, including siRNA, DNA complexes, and proteins.22, 23 One particular study conjugated GALA to an anti-transferrin antibody and demonstrated these immunoconjugates were able to release up to 10 kDa fluorescent dextrans from liposomes.24 Their studies also indicated higher molecular weight dextrans required a greater peptide:lipid ratio or peptide-to-antibody ratio (PAR). However, increasing PAR values can lead to disadvantageous pharmacokinetics due to alteration of antibody biophysical characteristics (e.g., pI).

His-CM18-PTD4, a hybrid cationic peptide containing six N-terminal histidine residues, residues 1–7 of cecropin-A, residues 2–12 of melittin, and TAT variant PTD4, was shown to enhance the transfection efficiency of CRISPR-Cas9/Cpf1 components and passage of up to 250 kDa sized fluorescent dextrans in vitro.25 Although CM18-PTD4 is cationic and can interact with the plasma membrane, the hexahistidine tag provides the peptide with some pH-sensitive characteristics, destabilizing endosomes by the proton sponge effect.25–27 We have recently developed a truncated version of the peptide, H6CM18, to facilitate the cytosolic delivery of a ribosome-inactivating protein, gelonin.28 Briefly, our strategy employed co-administration of anti-carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) antibody-gelonin immunotoxins with an anti-CEA antibody-H6CM18 conjugate. Simultaneous uptake of both conjugates into endosomes (e.g., via receptor-mediated endocytosis) enabled increased efficiency of gelonin release to the cytoplasm of targeted cells, and led to a 103 to 104-fold enhancement of gelonin potency in cell culture experiments. In vivo co-administration of the immune conjugates reduced tumor burden in LS174T xenograft mice by approximately 50% and increased survival duration by approximately 70%.28 Although our results demonstrated promise for treating tumors, the impact of H6CM18 conjugation on antibody pharmacokinetics is unknown.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAb) offer unique advantages over other delivery vehicles, as they may be developed or engineered for high affinity binding to cell surface proteins, exhibit long systemic half-lives, and provide a number of sites for conjugation of payloads. However, chemical conjugation of certain payloads can significantly alter mAb pharmacokinetics, leading to increased catabolism, decreased half-life, and substantially altering the tissue-selectivity of distribution. For example, quantitative structure-pharmacokinetic relationships established correlations between mAb systemic clearance and pI/charge29, 30 as well as the drug-to-antibody ratio31, 32. As many CPPs exhibit high net positive charges, it is possible that CPP conjugation could influence mAb pharmacokinetics, potentially as a function of pI and peptide-to-antibody ratio, as previously described with other positively charged moieties (e.g., hexamethylenediamine).

The present investigation evaluates the effects of conjugation of TAT, GALA, and H6CM18 on the pharmacokinetics of 10H6, a “catch-and-release” (CAR) mAb with pH-dependent binding to CEA.33, 34 CAR mAbs exhibit high affinity target binding at physiological pH (pH 7.4), but following endocytosis, rapidly dissociate from their binding target within the acidic environment of the endosome (pH 5.0–6.0). Following dissociation, unbound antibody is available for FcRn binding and FcRn-mediated transport from the endosome. FcRn is a salvaging receptor that protects IgG antibodies from catabolism within the endo-lysosomal system.35 When compared to a “standard” anti-CEA mAb (i.e., with pH-independent binding), 10H6 demonstrated decreased target-mediated elimination in the MC38CEA+ mouse model of colorectal cancer.34 In this study we evaluated the plasma and tissue pharmacokinetic differences between 10H6 and peptide-conjugated 10H6 in mice bearing MC38CEA+ tumors, which express human CEA and mouse FcRn.34, 36 The presented work provides insight into the in vivo application of cell-penetrating peptides for delivery of macromolecular molecules from a pharmacokinetic perspective.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Conjugation of Cell Penetrating Peptides to 10H6

Conjugation to primary amines can lead to high peptide:antibody ratios (PAR), potentially influencing mAb pharmacokinetics and/or pharmacodynamics. To circumvent this issue, a chromophore linker allowed monitoring of PAR by UV absorbance until ≈ 2 based on equation (1), preventing over-modification of antibody.

| (1) |

Figure 1A describes the conjugation reactions. The bis-arylhydrazone (BAH) linker was shown previously to be stable up to 95°C and pH 2.0–10.0.37–39

Figure 1.

Schematic of conjugation chemistry. Three types of conjugation approaches were employed: A) Solulink® technology, B) Copper-free click chemistry using lysine modification, and C) Copper-free click chemistry using free thiols.

Equation (2) was used to calculate final PAR values. 10H6-TAT and 10H6-GALA PAR values were 2.3 and 2.5, respectively (Table I).

Table I.

NCA derived plasma pharmacokinetic parameters for CAR mAb conjugates

| mAb | Dose (nmol/kg) | PAR | Estimated pI† | AUC0-t (nM·day) | CL (mL/day/kg) | Vss (mL/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10H6 | 6.67 | 0 | 6.64 | 335 ± 22.9 | 19.9 ± 1.36 | 62.4 ± 7.78 |

| 10H6-GALA | 6.67 | 2.3 | 5.98 | 147 ± 7.09 | 45.3 ± 2.18 | 159 ± 16.9 |

| 10H6-TAT | 6.67 | 2.5 | 8.34 | 56.1 ± 9.02 | 119 ± 19.0 | 216 ± 53.1 |

| 10H6-H6CM18 (NHS) | 6.67 | ~2–4 | ~7.91 | 111 ± 4.45 | 60.3 ± 2.43 | 169 ± 16.1 |

| 10H6-H6CM18 (Maleimide) | 6.67 | ~2–4 | ~7.91 | 204 ± 11.8 | 32.7 ± 1.89 | 103 ± 14.1 |

pI estimated using ExPASy Prot Param40

| (2) |

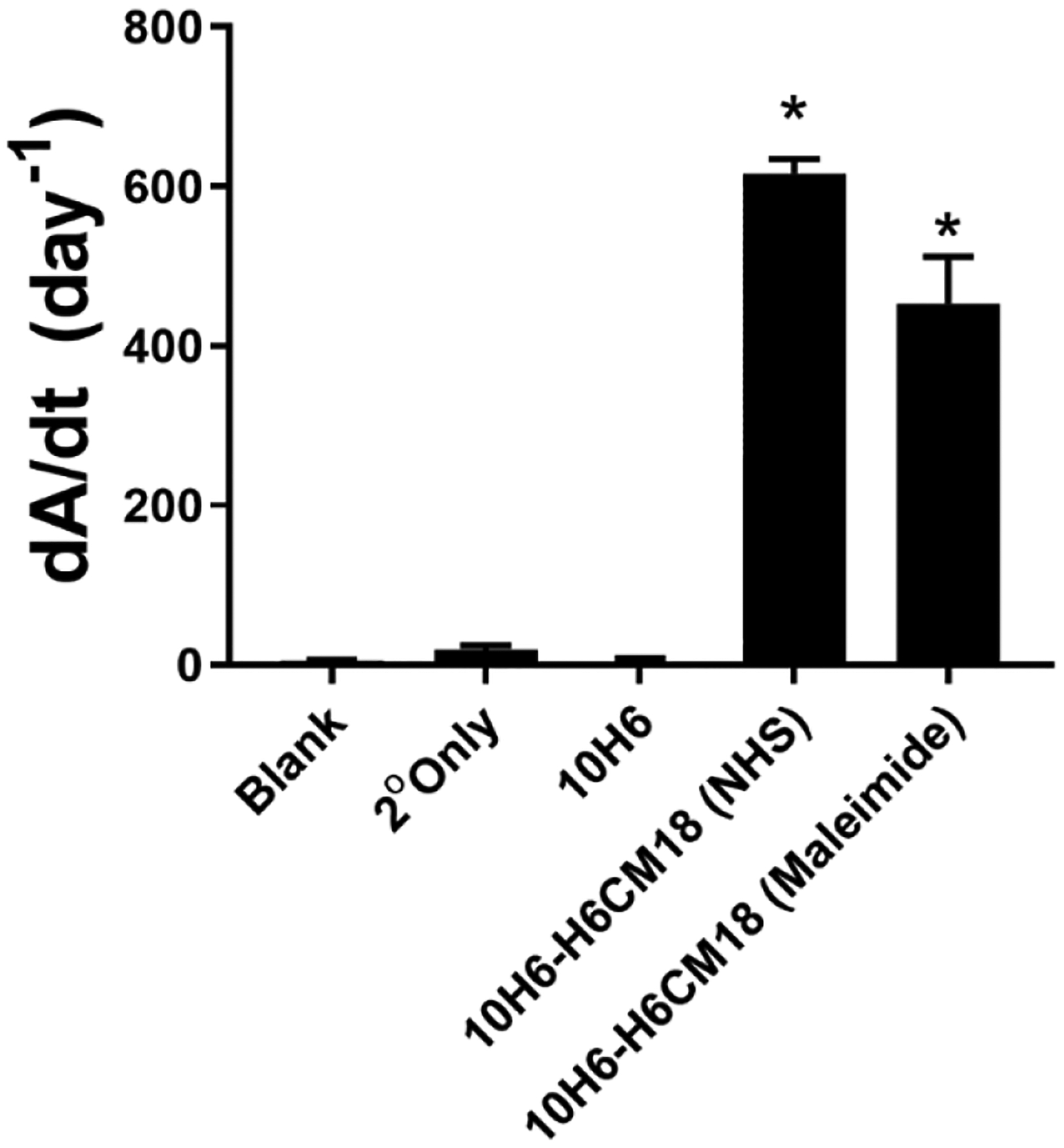

For NHS-DBCO, the ratio between A309 (i.e., absorbance of DBCO) and A280 with correction for DBCO at A280 (correction factor = 1.089) indicated a modification efficiency of 4.4:1 DBCO to 10H6 (Figure 1B). For maleimide-DBCO, the ratio between A309 and A280 indicated a modification ratio of 3.4:1 DBCO to 10H6 (Figure 1C). An ELISA using a CEA capture and anti-6xHis Tag antibody confirmed conjugation of H6CM18 to 10H6 (Figure 2). Representations of the four 10H6 conjugates used within this study are provided in Figure S1.

Figure 2.

Confirmation of H6CM18 conjugation to 10H6 by ELISA. A mouse anti-6xHist tag antibody with alkaline phosphatase detected H6CM18 on CEA bound 10H6. Statistical significance from 10H6 at p<0.0001 is denoted by *.

Plasma and Tissue Pharmacokinetics of 10H6

10H6 demonstrated biexponential kinetics in plasma and tissue following an intravenous (i.v.) bolus dose of 6.67 nmol/kg, consistent with typical antibody pharmacokinetics (Figure 3 & 4).

Figure 3.

Plasma pharmacokinetics of 10H6 (black circles), 10H6-GALA (green squares), 10H6-TAT (red upright triangles), 10H6-H6CM18 (NHS, blue inverse triangles), and 10H6-H6CM18 (Maleimide, purple diamonds) following an i.v. 6.67 nmol/kg dose in MC38CEA+ tumor bearing male C57 BL6/J mice. Data points represent the mean plasma concentration (n=3/time point), and error bars denote the standard deviation of the mean.

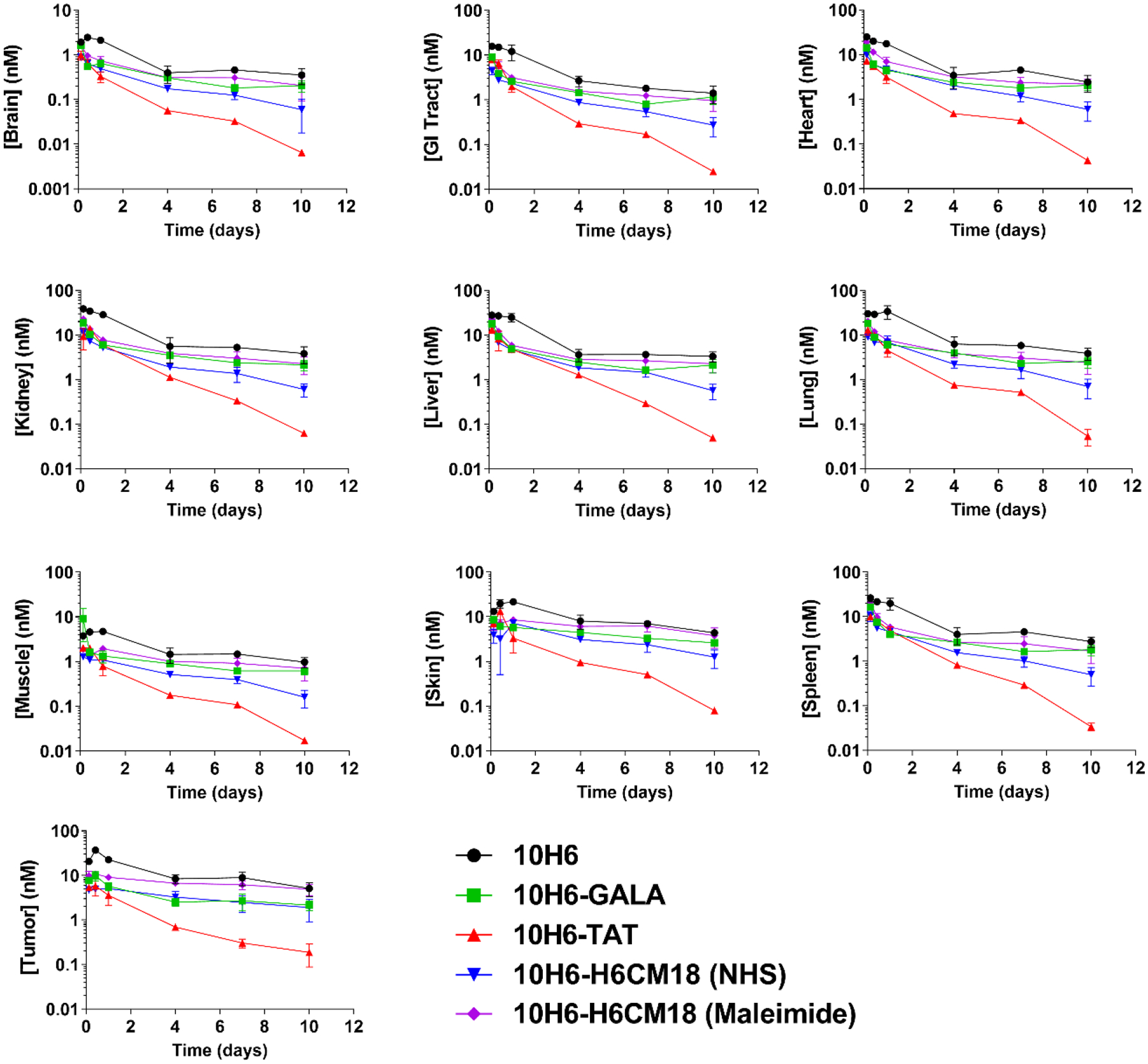

Figure 4.

Tissue pharmacokinetics of 10H6 (black circles), 10H6-GALA (green squares), 10H6-TAT (red upright triangles), 10H6-H6CM18 (NHS, blue inverse triangles), and 10H6-H6CM18 (Maleimide, purple diamonds) following an i.v. 6.67 nmol/kg dose in MC38CEA+ tumor bearing male C57 BL6/J mice. Data points represent the mean tissue concentration (n=3/time point), and error bars denote the standard deviation of the mean.

Non-compartmental analyses of 10H6 plasma pharmacokinetics indicated a mean plasma area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) of 335 ± 22.9 nM·day, plasma clearance (CL) of 19.9 ± 1.36 mL/day/kg, and volume of distribution at steady-state (VSS) of 62.4 ± 7.78 mL/kg. These values are consistent with studies conducted previously in our laboratory.34 Tissues that exhibited the highest degree of exposure were kidney (115 ± 12.3 nM·day), liver (90.9 ± 10.5 nM·day), lung (124 ± 22.3 nM·day), and skin (103 ± 10.5 nM·day) (Figure 5A, Table SI).

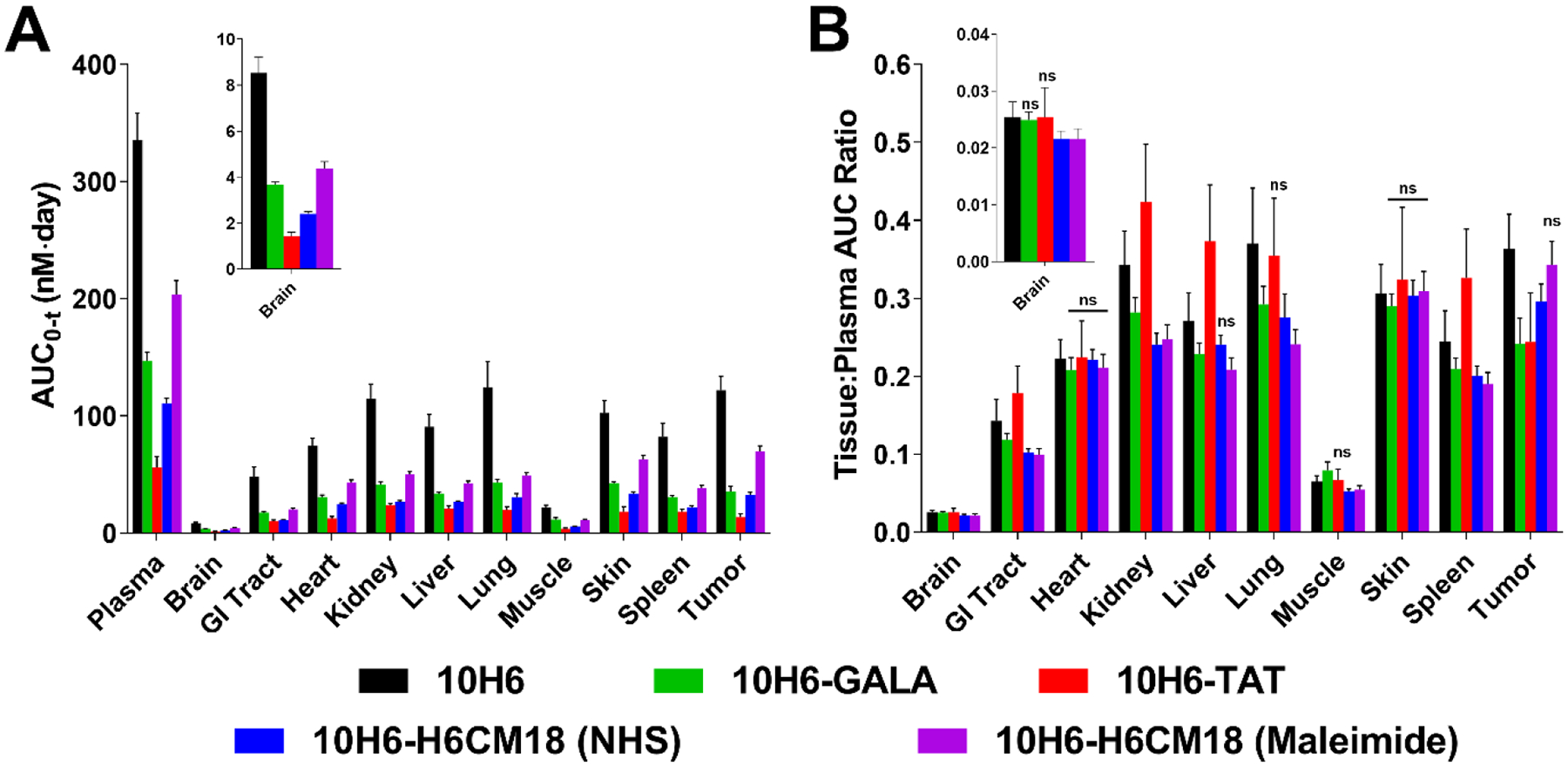

Figure 5.

A) Plasma and tissue AUC0-t values as calculated by non-compartmental analysis using Phoenix®. AUC values for 10H6 (black), 10H6-GALA (green), and 10H6-TAT (red), 10H6-H6CM18 (NHS, blue), and 10H6-H6CM18 (maleimide, purple) are expressed in nM·day and represent mean values and standard deviation of the mean. B) Comparison of tissue selectivity for 10H6 (black), 10H6-GALA (green), 10H6-TAT (red), 10H6-H6CM18 (NHS, blue), and 10H6-H6CM18 (Maleimide, purple) based on calculation of tissue:plasma AUC ratios. Tissue selectivity of 10H6 peptide conjugates were significantly different from 10H6 unless noted with ‘ns’, indicating not significantly different.

The presented findings are consistent with results of previous studies within our laboratory, which indicated 10H6 exposure in MC38CEA+ tumor xenografts was 98.4 ± 6.51 nM·day following a 3.34 nmol/kg dose. However, 10H6 exposure in MC38CEA+ tumors was somewhat lower than anticipated (122 ± 12.1 nM·day vs. ~200 nM·day, based on prior work34) following an IV dose of 6.67 nmol/kg (Figure 5A, Table SI). Tissue selectivity (AUCtissue/AUCplasma) was similar for all major tissues, except brain, muscle, lung and tumor. Brain and muscle demonstrated the lowest selectivity ratio (0.0254 ± 0.00267 and 0.0648 ± 0.00755, respectively), while lung (0.370 ± 0.0711) and tumor (0.364 ± 0.0438) demonstrated the highest AUC ratios (Figure 5B and Table SI). Recent reports have documented the benefits of CAR mAb as described by their plasma pharmacokinetics34, 41–43, but failed to investigate tissue exposure and tissue selectivity. This study provides the first detailed description of the pharmacokinetics of 10H6, an anti-CEA CAR mAb, with assessment of tissue and tumor exposure and selectivity.

Plasma and Tissue Pharmacokinetics of GALA Immunoconjugates

10H6-GALA conjugates following 6.67 nmol/kg exhibited a decreased AUC0-t, 147 ± 7.09 nM·day, increased plasma clearance to 45.3 ± 2.18 mL/day/kg, and increased volume of distribution, 159 ± 16.9 mL/kg, as compared to 10H6. Conjugation of GALA to 10H6 significantly decreased exposure in all tissues (Figure 5A, green bars). Furthermore, tumor exposure and selectivity significantly decreased by 71% and 33% (Figure 5B, green bars). In non-tumor tissues, 10H6-GALA tissue selectivity decreased between 5–25%. Changes in antibody biophysical properties may lead to enhanced plasma elimination and decreased exposure. This phenomenon was reported previously with relationships between pI/charge and plasma half-life.29, 30 Interestingly, prior work exploring the pharmacokinetics of anionized radioimmunoconjugates demonstrated mixed observations. For example, modification of radioimmunoconjugates with diethylene triamine penta-acetic acid (DTPA) increased blood half-life by up to 2-fold with decreasing pI.44 Another study indicated moderate modification of IgG with succinate did not alter the pharmacokinetics following a 20 mg/kg dose, resulting in similar plasma AUC and plasma CL to unmodified antibody. On the contrary, the same study also demonstrated that a high degree of succinylation (which further decreased the pI value) decreased AUC and increased plasma CL following a 20 mg/kg dose.45

GALA contains several negatively charged amino acid residues, resulting in a charge and pI value at physiological pH of −7 and 3.82, respectively. Sequence analysis suggests conjugation of two GALA molecules decreases the overall pI of 10H6 from 6.64 to 5.98. The 0.66 decreased pI value could be sufficient to enhance clearance of 10H6; however, mechanisms of anionic antibody elimination are still under investigation. One hypothesis suggests salvaging receptors expressed on liver nonparenchymal cells readily endocytose and eliminate succinylated IgG molecules and other negatively charged proteins.45 10H6-GALA exhibited a significantly decreased liver exposure (−63%) and selectivity (−16%) as compared to 10H6 (Figure 5). If this hypothesis were true in this instance, one would expect greater liver accumulation and selectivity than unconjugated 10H6. Other EEPs similar to GALA, such as INF7 or HA2 peptides identified from the influenza virus, strongly associate with lipid membranes at mildly acidic pH (≤6).46 Typically, EEPs are neutral or negatively charged at physiological pH, but acidification of the environment causes a positive charge switch. This charge switch facilitates GALA interaction with lipid membranes. GALA-lipid interactions and leakage kinetics were evaluated previously where an estimated rate of release was estimated to be 0.002 s−1.47 The endosomal concentration of 10H6-GALA at tumor interstitial Cmax (≈10 nM) could reach 1–10 μM based on the concentrating effect between the plasma membrane (i.e. interstitial concentration) and endosome lumen. Based on these values, GALA interaction with endosomal membranes could be favored over Fc binding to FcRn (ka ≈ 3.8e4 – 16.1e4 M−1∙s−1)48. The enhanced interaction with endosomal membranes could prevent the recycling of antibody, as the conjugate is associated with lipids rather than FcRn. Expected observations consistent with this hypothesis are decreased plasma exposure, decreased tissue exposure, increased clearance, and an apparent increase in VSS, attributed to association with endosomes of vascular endothelial cells. The pharmacokinetic parameters associated with 10H6-GALA are consistent with this hypothesis.

Plasma and Tissue Pharmacokinetics of TAT Immunoconjugates

Concentration vs. time data indicates 10H6-TAT deviated from 10H6 pharmacokinetics in plasma (Figure 3) and tissues (Figure 4). 10H6-TAT AUC0-t was 56.1 ± 9.02 nM·day that corresponded to a plasma CL of 119 ± 19.0 mL/day/kg. When compared to 10H6, 10H6-TAT demonstrated a 3.5-fold increase in VSS from 62.4 ± 8.49 mL/kg to 216 ± 53.1 mL/kg (Table I). Although TAT conjugates resulted in decreased tissue exposure, tissue selectivity increased in a number of tissues when compared to 10H6: GI tract (+25%), kidney (+24%), liver (+38%), muscle (+18%), and spleen (+36%) (p<0.05 by one-way ANOVA) (Figure 5B and Table SI). The increase in liver and spleen selectivity suggests enhanced uptake by tissue-residing reticuloendothelial cells, such as Kupffer cells within liver. On the contrary, tumor exposure and selectivity of 10H6 decreased to 13.7 ± 2.77 nM·day (−89%) and 0.244 ± 0.0630 (−32%) following TAT conjugation.

Of the few studies investigating peptide conjugation to protein carriers, one evaluated the tissue distribution and plasma pharmacokinetics of streptavidin (52 kDa) with or without non-covalent conjugation of TAT-biotin.17 TAT conjugation to streptavidin led to a 24-fold decrease in streptavidin AUC0-t, 24-fold increase in plasma clearance, and 2.7-fold increase in VSS. 10H6-TAT demonstrated similar pharmacokinetics where there was a 6-fold decrease in AUC0-t, 6-fold increase in clearance, and 3.5-fold increase in VSS.

As TAT is arginine and lysine rich, the charge and pI values at physiological pH are +7 and 12.7, respectively. According to sequence analysis, conjugation of two TAT molecules to 10H6 increases the overall pI from 6.64 to 8.34. Pharmacokinetic observations of cationized antibodies with pI changes ≥ 1 unit resulted in increased plasma clearances up to 1600-fold through conjugation of hexamethylenediamine.49–52 It is hypothesized positive-charged patches on the surface of antibodies may interact with negatively charged groups on the surface of cells, leading to enhanced CL.52, 53 For TAT, several studies have demonstrated the involvement of ATP-dependent uptake pathways, such as receptor mediated endocytosis by heparan sulfate proteoglycans.54–57 Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) are cell surface proteins (i.e. glypicans and syndecans) heavily glycosylated with negatively charged heparan sulfate residues, which are extensively expressed on vascular endothelial cells.58 Binding of TAT to HSPG occurs at moderate affinity (KD = 64 nM).59 The koff of TAT-HSPG is 0.0027 s−1, meaning the half-life of dissociation would be sufficient for release within the endosome during maturation, allowing 10H6-TAT to bind FcRn and recycle back to vascular space. However, there is evidence binding of TAT can stimulate internalization and micropinocytosis of HSPG, potentially leading to sufficient amounts of TAT conjugate being internalized into endosomes and subsequently catabolized if unbound from FcRn60, 61.

10H6 may reduce target-mediated elimination by pH-dependent release of antigen and subsequent FcRn recycling from the endosome, escaping catabolism by CEA expressing tumors. To explore the possible role of FcRn in recycling CAR mAbs, a qualitative FcRn Western blot analysis was performed, which confirmed expression of mFcRn within MC38CEA+ cells34. The presence of mFcRn within MC38CEA+ cells suggests that released CAR mAbs can recycle from MC38CEA+ tumor cell endosomes. As conjugation of the peptides to 10H6 is nonspecific, it is possible steric or electrostatic interferences of Fc and FcRn binding may prevent 10H6 recycling. In a human model of colorectal cancer, LS174T, target-mediated elimination of 10H6 was observed due to a lack of recycling by hFcRn, resulting in a plasma clearance of 39.9 mL/day/kg following 1 mg/kg. 10H6-TAT demonstrated a 3-fold greater clearance, 119 mL/day/kg. This rapid clearance suggests other mechanisms than target-mediated elimination are driving the systemic clearance of these conjugates. As described previously, internalization by HSPG expressed on vascular endothelial cells and uptake by RES cells may lead to increased clearance of TAT conjugated proteins, explaining the greater than expected clearance for human colorectal cancer xenografts and/or FcRn knockout mice. Murine IgG in FcRn knock-out mice demonstrate a CL of ~61 mL/day/kg.62 If TMD (i.e., CEA and HSPG mediated uptake) is compounded by a lack of FcRn binding, then total clearance (i.e. CLtotal = CLnonspecific + CLTMD) may approach 100 mL/day/kg, which is consistent with the observed CL value of 119 ± 19.0 mL/day/kg.

Pharmacokinetics of H6CM18 Immunoconjugates

Prior work by Feldan Therapeutics indicates efficient transduction of large macromolecules in vitro when combined with peptide His-CM18-PTD4, where cytosolic delivery of CRISPR-Cas9/Cpf1 components and large molecular weight fluorescent dextrans was achieved in culture within a few minutes.25 PTD4 (a TAT derivative) was attached to the peptide in order to facilitate cellular uptake and the hexahistidine tag was attached to the N-terminus to promote endosomal destabilization.25, 63, 64 Here, the hybrid peptide was truncated to H6CM18 to overcome pharmacokinetic limitations of TAT and its derivatives. In addition, there is a lack of evidence His-CM18-PTD4 retains membrane destabilizing properties while stably conjugated to protein payloads.25 These reasons led us to pursue methods to link H6CM18 to 10H6 using the cleavable vc-PAB linker and copper-free click chemistry (Figure 1B & 1C). As shown with brentuximab vedotin and other ADCs, vc-linker chemistry is stable in plasma and primarily requires enzymatic cleavage to release payload.65

Pharmacokinetic studies for H6CM18 conjugates were analyzed for both both NHS and maleimide conjugation strategies. Examining concentration v. time profiles, both conjugates exhibit biexponential kinetics, with 10H6-H6CM18 (NHS) deviating furthest from 10H6 (Figure 3). Modification of 10H6 by NHS linking chemistry reduced AUC0-t to 111 ± 4.45 nM·day, increased plasma CL to 60.3 ± 2.43 mL/day/kg, and increased VSS to 169 ± 16.1 mL/kg. Maleimide modification also reduced plasma exposure (AUC0-t = 204 ± 11.8 nM·day), increased plasma clearance (CL = 32.7 ± 1.89 mL/day/kg) and volume of distribution (VSS = 103 ± 14.1 mL/kg), but to a lesser degree than NHS modification (Table I).

Tissue pharmacokinetics mirrored plasma (Figure 4), where both conjugates demonstrated significantly reduced tissue exposure (p<0.05) (Figure 5A). 10H6-H6CM18 (NHS) demonstrated a 17% reduction in tumor selectivity, whereas, maleimide conjugation was statistically similar (p = 0.5314) to 10H6 with only a 2.5% reduction (Figure 5B).

The presented data also demonstrated PK differences between the two 10H6-H6CM18 constructs, where thiol conjugation resulted in a 1.9-fold lower plasma CL and superior plasma and tumor exposure than primary amine conjugation. These observed differences may be attributed to the modification chemistry and reagents. For thiol conjugation, the maleimide-PEG4-DBCO reagent prevented aggregation as compared to a maleimide-DBCO reagent. Addition of the PEG spacer likely attributed to reduced hydrophobic interactions and increased solubility as compared to NHS-DBCO modified 10H6. These differences in linker hydrophobicity and site modification (i.e. amine vs. thiol) likely contribute to the observed PK differences. For example, ADCs have utilized PEG within linkers in order to increase developability and PK properties66–68, as demonstrated with Kadcyla.69

Although removal of PTD4 from the parent peptide alleviated some pharmacokinetic limitations of TAT-like peptides, H6CM18 demonstrated significant alterations in plasma and tissue pharmacokinetics. CM18 is a hybrid peptide consisting of residues 1–7 of cecropin-A and residues 2–12 of melittin, known cell-penetrating peptides with basic pI values (i.e., pIcecropin-A = 10.39, pImelittin = 12.02). Hybridizing these peptides and attaching six N-terminal histidine residues results in a charge and pI value at physiological pH of +5 and 10.60. Conjugation to 10H6 increases overall pI from 6.64 to 7.91. Considering the shift in pI is >1, it is expected there will be an enhanced clearance based on prior observations from literature30, 41, 51–53 and our presented data with TAT conjugates. Due to the cationic charge of CM18, H6CM18 peptide conjugates possibly share similar elimination mechanisms with TAT conjugate, as described previously.

Pharmacokinetic-Biophysical Relationship of CAR mAbs and Conjugates

Cell penetrating peptides have garnered the attention of those in drug delivery due to their small size and ability to translocate or facilitate delivery of macromolecular compounds. As demonstrated in these studies, CPPs and EEPs significantly influence the pharmacokinetics of their targeting domain (e.g. mAbs) potentially due to changes in the biophysical characteristics. Redistribution of antibody charge on the Fv domain has shown to reduce the Fc-FcRn interaction, resulting in decreased half-life. Schoch et al. established a linear correlation between in vivo half-life and pH to elute antibody from an FcRn affinity column, concluding antibodies that require higher elution pH, or higher antibody pI, have shorter half-lives30. Igawa et al. described a similar relationship for non-targeted IgG4 charge variants, where greater pI values reduced systemic half-life in wild-type and β2-microglobulin knock-out mice41. The authors also used site-directed mutagenesis to reduce the pI value of a humanized anti-IL6 antibody, which demonstrated a decrease in clearance following IV and SC dosing. A comprehensive review on antibody ionization and pharmacokinetics by Boswell et al illustrated cationization of radioimmunoconjugates typically increased plasma clearance and increased distribution into RES-associated tissues (e.g. liver, lungs, & spleen).29 On the contrary, anionization of antibody radioimmunoconjugates exhibited mixed results, with CL values increasing, decreasing, or remaining similar to parent.

To understand further the impact of peptide conjugation to 10H6 and aid in selection of a peptide candidate for in vivo application, we examined relationships between antibody pI and pharmacokinetic parameters (Figure 6). Both CL and VSS relationships with antibody pI demonstrated bell-shaped curves that are consistent with reported data. In addition, the nadir of this apparent bell-shaped curve are consistent with expected clearance (~3–5 mL/day/kg) and VSS (~55–60 mL/kg) values of murine IgG with average pI value 6.8–7.0.41, 62, 70 These relationships indicate CPP/EEPs shift in overall antibody pI should be ≤0.5 pI unit change in order to reduce the likelihood of altering mAb pharmacokinetics.

Figure 6.

Relationships between peptide conjugate pI and pharmacokinetic parameters CL (blue circles) and VSS (red squares). The relationship between estimated antibody and conjugate pI indicates a bell-shaped relationship, where CL and VSS increase when pI > 1 or pI < 1.

CONCLUSION

Here, we have described what we believe to be the first full pharmacokinetic and biodistribution analysis of CPP/EEP antibody conjugates in normal and tumor tissues. Although the molecular size of CPP/EEP peptides is advantageous for antibody conjugation, we found that, relative to unconjugated mAb, CPP/EEP-mAb conjugates demonstrated significantly increased plasma clearance, and decreased plasma exposure, tumor exposure, and tumor selectivity. In some delivery applications, the effects of CPP/EEP on plasma and tissue disposition may fully or partially offset their benefits on cellular uptake and intracellular distribution. The relationship established between antibody-CPP/EEP conjugates and pI may have utility in guiding the development of novel constructs for in vivo applications of macromolecular delivery.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibody Production & Purification

The CAR mAb, 10H6, is a murine IgG1κ anti-CEA antibody with pH-dependent affinity previously established within our laboratory using standard hybridoma technology. Antibody hybridoma cell lines were grown at 37°C and 5% CO2 in serum free medium (SFM) (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) with 5 μg/L gentamicin. SFM was harvested twice a week from a 1 L spinner flask, followed by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 10 min and then filtered through a 0.22 μm filter-top to remove any remaining cell debris. mAbs were then purified on a HiTrap Protein G Chromatography column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden) using an NGC Quest 10 Chromatography System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Briefly, the column was equilibrated with 20 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.0 buffer before loading cell supernatant. After media loading, the column was washed with 10 column volumes of 20 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.0. Protein G bound antibody was then eluted using a 100 mM glycine, pH 2.8 as 5 mL fractions. Collected fractions were then dialyzed against PBS, pH 7.4, at 4°C. Antibody purity was assessed on an SDS-PAGE.

Peptide Conjugate Synthesis

TAT and GALA were conjugated to 10H6 by a stable bis-arylhydrazone linker (BAH) (Solulink® Technology, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Innopep, Inc (San Diego, CA) synthesized GALA (WEAALAEALAEALAEHLAEALAEALEALAA) and TAT (GRKKRRQRRR) peptides with a single S-HyNic (1, N-succinimidyl-6-hydrazino-nicotinamide) reactive group coupled to the N-terminus for ease of conjugation to antibody. For production of peptide conjugates, 10H6 was reacted with S-4FB (2, N-succinimidyl-4-formylbenzamide) reagent in a 1:5 molar ratio (Ab:4FB) in modification buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0) for 2.5 h at room temperature. 4FB modified antibody was then buffered exchanged into conjugation buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). Lyophilized HyNic modified peptide was then reconstituted in conjugation buffer with 0–10% dimethylformamide (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH), depending on solubility, and mixed with 4FB modified antibody. The reaction was catalyzed by adding 10x aniline catalytic reagent (100 mM aniline, 100 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 6.0) to a final concentration of 10 mM. The reaction was conducted in a plastic cuvette in order to monitor the formation of bis-aryl hydrazine (BAH) bonds at 354 nm (BAH ε = 29000 M−1·cm−1). Reactions were then buffer exchanged using a 7 kDa desalting column (ThermoFisher, Grand Island, NY) equilibrated with 1xPBS when the PAR value was approximately 2 (eq.1) to remove excess peptide and linker. Following desalting, the conjugate was then dialyzed against PBS overnight where then PAR was re-evaluated using equation 2. Total protein concentrations being used to determine PAR were evaluated using a Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher, Grand Island, NY).

H6CM18 peptide (HHHHHHKWKLFKKIGAVLKVLTTG) was synthesized by ThermoFisher with the azide-PEG3-valine-citrulline-(p-aminobenzyloxycarbonyl) (N3-PEG3-vc-PABC) linker attached to the N-terminus. Addition of a terminal azide group allows conjugation to antibody by copper-free click chemistry71. T84.66 was functionalized with dibenzocyclooctyne-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester (DBCO-NHS, Click Chemistry Tools, Scottsdale, AZ) by reacting at 1:5 molar equivalents for 15 min at room temperature with constant mixing in PBS. The reaction was quenched by spiking in 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.0 to a final concentration of 75 mM for 7 min. After quenching, the reaction was desalted into PBS and reacted with peptide 1:4 molar ratio (Ab:peptide) overnight at 4°C. For maleimide conjugation, 5 mg of 10H6 in Dulbeco’s PBS was first reduced with 3.67 molar equivalents of 10 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) for 2 h at 37°C in a polystyrene tube. Following TCEP reduction, free thiol groups were measured using 5,5-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) (ThermoFisher, Grand Island, NY). Briefly, 6.66 μL of reduced 10H6 was added to 10 μL of 1 mM DTNB and 83.3 μL of DPBS, incubated for 10 min, and then absorbance was measured at 412 nm. Reduced antibody was then reacted at room temperature for 1 h with 1:8 molar ratio DBCO-(PEG)4-Maleimide (Click Chemistry Tools, Scottsdale, AZ), where maleimide will react with free thiol groups of the antibody. This reaction was quenched by buffer exchanging into DPBS and then reacted overnight at 4°C with 4 molar equivalents of N3-PEG3-vc-PAB-H6CM18, with 20% v/v DMF to prevent precipitation of linker during the reaction. Lysine and cysteine modification reactions were desalted and dialyzed into PBS, where peptide conjugation was confirmed by ELISA using CEA coated plates to capture anti-CEA antibody and detected with an anti-6xHis Tag-alkaline phosphatase conjugate, which recognizes the hexahistidine sequence on H6CM18.

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice aged 4 to 6 weeks were purchased from Charles Rivers Laboratories. Mice were housed in a temperature and humidity controlled environment with a standard light/dark cycle, as well as continual access to water and food. All animal protocols complied with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the State University of New York at Buffalo Animal Facility regulations.

Pharmacokinetics in MC38CEA+ Tumor-Xenograft Mice

Pharmacokinetic studies were conducted in MC38CEA+ tumor bearing C57BL/6 mice, as described previously.34 MC38CEA+ tumor cells are murine origin and express human CEA.72 After one week of acclimation, approximately 5×106 MC38CEA+ cells were injected subcutaneously into the left abdominal quadrant. Two days before dosing, KI (0.2 g/L) was added to the drinking water of all mice to block thyroid uptake of free 125I. Once tumors reached 200–300 mm3, a dose of 6.67 nmol/kg 10H6, 10H6-GALA, or 10H6-TAT with respective 400 μCi 125I-labeled tracer doses were administered by penile vein injection. Mice were terminally sacrificed at 3, 10 h, 1, 4, 7, and 10 days (n=3/time point), where blood and tissues were harvested. Plasma was collected after centrifuging blood at 14,000× g for 2 min and stored at −20°C. During harvest, tissues were blotted with gauze to remove any residual blood on the outside of the specimen. In order to remove free and catabolite-associated 125I, samples were precipitated by TCA (Sigma Life Sciences, St. Louis, MO). Briefly, precipitation of plasma samples was carried out on ice for 15 min following addition of 200 μL of 1% v/v BSA and 700 μL 10% w/v TCA in PBS. Samples were then centrifuged at 14,000× g for five minutes to pellet the precipitate. After centrifugation, supernatant was discarded and precipitated pellet was washed with PBS. Pellets were washed three times with PBS. The precipitated samples and harvested tissues were counted for gamma radiation in order to determine the concentration of anti-CEA mAb.

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

Phoenix® v.8.1 was used to conduct noncompartmental analysis on concentration v. time data using sparse data sampling, which utilizes the Bailer-Satterthwaite approximation. AUC was calculated using linear-log trapezoidal method.

Supplementary Material

Supporting information includes Figure S1, which provides representation of 10H6 peptide conjugates used within the presented PK studies, and Table SI, which provides tissue exposure and selectivity ratios for the CAR mAb peptide conjugates.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (CA204192, CA246785) and by the Center for Protein Therapeutics.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CAR

Catch-and-Release

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- FcRn

Neonatal Fc receptor

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- mAb

Monoclonal antibody

- PTD

Protein Transduction Domain

- CPP

Cell-Penetrating Peptide

- EEP

Endosomal Escape Peptide

- NCA

Noncompartmental Analysis

- AUC0-t

Area Under the Concentration Curve from time 0-t

- CL

Clearance

- Vss

Volume of Distribution at Steady-State

- HSPG

Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan

- PAR

Peptide-Antibody Ratio

REFERENCES

- 1.Hou KK; Pan H; Ratner L; Schlesinger PH; Wickline SA, Mechanisms of nanoparticle-mediated siRNA transfection by melittin-derived peptides. ACS Nano 2013, 7 (10), 8605–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundberg P; El-Andaloussi S; Sutlu T; Johansson H; Langel U, Delivery of short interfering RNA using endosomolytic cell-penetrating peptides. FASEB J 2007, 21 (11), 2664–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore NM; Sheppard CL; Barbour TR; Sakiyama-Elbert SE, The effect of endosomal escape peptides on in vitro gene delivery of polyethylene glycol-based vehicles. J Gene Med 2008, 10 (10), 1134–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moschos SA; Jones SW; Perry MM; Williams AE; Erjefalt JS; Turner JJ; Barnes PJ; Sproat BS; Gait MJ; Lindsay MA, Lung delivery studies using siRNA conjugated to TAT(48–60) and penetratin reveal peptide induced reduction in gene expression and induction of innate immunity. Bioconjug Chem 2007, 18 (5), 1450–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niikura K; Horisawa K; Doi N, Endosomal escape efficiency of fusogenic B18 and B55 peptides fused with anti-EGFR single chain Fv as estimated by nuclear translocation. J Biochem 2016, 159 (1), 123–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sparrow JT; Edwards VV; Tung C; Logan MJ; Wadhwa MS; Duguid J; Smith LC, Synthetic peptide-based DNA complexes for nonviral gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 1998, 30 (1–3), 115–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shin MC; Zhang J; Ah Min K; Lee K; Moon C; Balthasar JP; Yang VC, Combination of antibody targeting and PTD-mediated intracellular toxin delivery for colorectal cancer therapy. J Control Release 2014, 194, 197–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fawell S; Seery J; Daikh Y; Moore C; Chen LL; Pepinsky B; Barsoum J, Tat-mediated delivery of heterologous proteins into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91 (2), 664–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X; Sa’adedin F; Deme B; Rao P; Bradshaw J, Insertion of TAT peptide and perturbation of negatively charged model phospholipid bilayer revealed by neutron diffraction. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1828 (8), 1982–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vives E; Brodin P; Lebleu B, A truncated HIV-1 Tat protein basic domain rapidly translocates through the plasma membrane and accumulates in the cell nucleus. J Biol Chem 1997, 272 (25), 16010–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herce HD; Garcia AE; Litt J; Kane RS; Martin P; Enrique N; Rebolledo A; Milesi V, Arginine-Rich Peptides Destabilize the Plasma Membrane, Consistent with a Pore Formation Translocation Mechanism of Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Biophys J 2009, 97 (7), 1917–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mishra A; Lai GH; Schmidt NW; Sun VZ; Rodriguez AR; Tong R; Tang L; Cheng J; Deming TJ; Kamei DT, et al. , Translocation of HIV TAT peptide and analogues induced by multiplexed membrane and cytoskeletal interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108 (41), 16883–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derossi D; Calvet S; Trembleau A; Brunissen A; Chassaing G; Prochiantz A, Cell internalization of the third helix of the Antennapedia homeodomain is receptor-independent. J Biol Chem 1996, 271 (30), 18188–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ter-Avetisyan G; Tunnemann G; Nowak D; Nitschke M; Herrmann A; Drab M; Cardoso MC, Cell entry of arginine-rich peptides is independent of endocytosis. J Biol Chem 2009, 284 (6), 3370–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mann DA; Frankel AD, Endocytosis and targeting of exogenous HIV-1 Tat protein. EMBO J 1991, 10 (7), 1733–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eguchi A; Akuta T; Okuyama H; Senda T; Yokoi H; Inokuchi H; Fujita S; Hayakawa T; Takeda K; Hasegawa M, et al. , Protein transduction domain of HIV-1 Tat protein promotes efficient delivery of DNA into mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 2001, 276 (28), 26204–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee HJ; Pardridge WM, Pharmacokinetics and delivery of tat and tat-protein conjugates to tissues in vivo. Bioconjug Chem 2001, 12 (6), 995–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarko D; Beijer B; Garcia Boy R; Nothelfer EM; Leotta K; Eisenhut M; Altmann A; Haberkorn U; Mier W, The pharmacokinetics of cell-penetrating peptides. Mol Pharm 2010, 7 (6), 2224–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erazo-Oliveras A; Muthukrishnan N; Baker R; Wang TY; Pellois JP, Improving the endosomal escape of cell-penetrating peptides and their cargos: strategies and challenges. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2012, 5 (11), 1177–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li W; Nicol F; Szoka FC Jr., GALA: a designed synthetic pH-responsive amphipathic peptide with applications in drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2004, 56 (7), 967–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esbjorner EK; Oglecka K; Lincoln P; Graslund A; Norden B, Membrane binding of pH-sensitive influenza fusion peptides. positioning, configuration, and induced leakage in a lipid vesicle model. Biochemistry 2007, 46 (47), 13490–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plank C; Oberhauser B; Mechtler K; Koch C; Wagner E, The influence of endosome-disruptive peptides on gene transfer using synthetic virus-like gene transfer systems. J Biol Chem 1994, 269 (17), 12918–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simoes S; Slepushkin V; Gaspar R; de Lima MC; Duzgunes N, Gene delivery by negatively charged ternary complexes of DNA, cationic liposomes and transferrin or fusigenic peptides. Gene Ther 1998, 5 (7), 955–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuehne J; Murphy RM, Synthesis and characterization of membrane-active GALA-OKT9 conjugates. Bioconjug Chem 2001, 12 (5), 742–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Del’Guidice T; Lepetit-Stoffaes JP; Bordeleau LJ; Roberge J; Theberge V; Lauvaux C; Barbeau X; Trottier J; Dave V; Roy DC, et al. , Membrane permeabilizing amphiphilic peptide delivers recombinant transcription factor and CRISPR-Cas9/Cpf1 ribonucleoproteins in hard-to-modify cells. PLoS One 2018, 13 (4), e0195558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrer-Miralles N; Corchero JL; Kumar P; Cedano JA; Gupta KC; Villaverde A; Vazquez E, Biological activities of histidine-rich peptides; merging biotechnology and nanomedicine. Microb Cell Fact 2011, 10, 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meng Z; Luan L; Kang Z; Feng S; Meng Q; Liu K, Histidine-enriched multifunctional peptide vectors with enhanced cellular uptake and endosomal escape for gene delivery. J Mater Chem B 20107, 5 (1), 74–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polli JR; Chen P; Bordeau BM; Balthasar JP, Targeted Delivery of Endosomal Escape Peptides to Enhance Immunotoxin Potency and Anti-cancer Efficacy. The AAPS Journal 2022, 24 (3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boswell CA; Tesar DB; Mukhyala K; Theil FP; Fielder PJ; Khawli LA, Effects of charge on antibody tissue distribution and pharmacokinetics. Bioconjug Chem 2010, 21 (12), 2153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoch A; Kettenberger H; Mundigl O; Winter G; Engert J; Heinrich J; Emrich T, Charge-mediated influence of the antibody variable domain on FcRn-dependent pharmacokinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112 (19), 5997–6002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamblett KJ; Senter PD; Chace DF; Sun MM; Lenox J; Cerveny CG; Kissler KM; Bernhardt SX; Kopcha AK; Zabinski RF, et al. , Effects of drug loading on the antitumor activity of a monoclonal antibody drug conjugate. Clin Cancer Res 2004, 10 (20), 7063–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun X; Ponte JF; Yoder NC; Laleau R; Coccia J; Lanieri L; Qiu Q; Wu R; Hong E; Bogalhas M, et al. , Effects of Drug-Antibody Ratio on Pharmacokinetics, Biodistribution, Efficacy, and Tolerability of Antibody-Maytansinoid Conjugates. Bioconjug Chem 2017, 28 (5), 1371–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polli JR; Engler FA; Balthasar JP, Physiologically Based Modeling of the Pharmacokinetics of “Catch-and-Release” Anti-Carcinoembryonic Antigen Monoclonal Antibodies in Colorectal Cancer Xenograft Mouse Models. J Pharm Sci 2019, 108 (1), 674–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engler FA; Polli JR; Li T; An B; Otteneder M; Qu J; Balthasar JP, “Catch-and-Release” Anti-Carcinoembryonic Antigen Monoclonal Antibody Leads to Greater Plasma and Tumor Exposure in a Mouse Model of Colorectal Cancer. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2018, 366 (1), 205–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roopenian DC; Christianson GJ; Proetzel G; Sproule TJ, Human FcRn Transgenic Mice for Pharmacokinetic Evaluation of Therapeutic Antibodies. Methods Mol Biol 2016, 1438, 103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robbins PF; Kantor JA; Salgaller M; Hand PH; Fernsten PD; Schlom J, Transduction and expression of the human carcinoembryonic antigen gene in a murine colon carcinoma cell line. Cancer Res 1991, 51 (14), 3657–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kozlov IA; Melnyk PC; Stromsborg KE; Chee MS; Barker DL; Zhao C, Efficient strategies for the conjugation of oligonucleotides to antibodies enabling highly sensitive protein detection. Biopolymers 2004, 73 (5), 621–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iyer G; Pinaud F; Xu J; Ebenstein Y; Li J; Chang J; Dahan M; Weiss S, Aromatic aldehyde and hydrazine activated peptide coated quantum dots for easy bioconjugation and live cell imaging. Bioconjug Chem 2011, 22 (6), 1006–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vector Laboratories. Bioconjugation White Paper: Quantitative and Reproducible Bioconjugation with SoluLINK® Technology 2020. https://vectorlabs.com/solulink-bioconjugation-white-paper.

- 40.Wilkins MR; Gasteiger E; Bairoch A; Sanchez JC; Williams KL; Appel RD; Hochstrasser DF, Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol Biol 1999, 112, 531–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Igawa T; Tsunoda H; Tachibana T; Maeda A; Mimoto F; Moriyama C; Nanami M; Sekimori Y; Nabuchi Y; Aso Y, et al. , Reduced elimination of IgG antibodies by engineering the variable region. Protein Eng Des Sel 2010, 23 (5), 385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Igawa T; Ishii S; Tachibana T; Maeda A; Higuchi Y; Shimaoka S; Moriyama C; Watanabe T; Takubo R; Doi Y, et al. , Antibody recycling by engineered pH-dependent antigen binding improves the duration of antigen neutralization. Nat Biotechnol 2010, 28 (11), 1203–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chaparro-Riggers J; Liang H; DeVay RM; Bai L; Sutton JE; Chen W; Geng T; Lindquist K; Casas MG; Boustany LM, et al. , Increasing serum half-life and extending cholesterol lowering in vivo by engineering antibody with pH-sensitive binding to PCSK9. J Biol Chem 2012, 287 (14), 11090–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.ten Kate CI; Fischman AJ; Rubin RH; Fucello AJ; Riexinger D; Wilkinson RA; Du L; Khaw BA; Strauss HW, Effect of isoelectric point on biodistribution and inflammation: imaging with indium-111-labelled IgG. Eur J Nucl Med 1990, 17 (6–8), 305–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamasaki Y; Sumimoto K; Nishikawa M; Yamashita F; Yamaoka K; Hashida M; Takakura Y, Pharmacokinetic analysis of in vivo disposition of succinylated proteins targeted to liver nonparenchymal cells via scavenger receptors: importance of molecular size and negative charge density for in vivo recognition by receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002, 301 (2), 467–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Varkouhi AK; Scholte M; Storm G; Haisma HJ, Endosomal escape pathways for delivery of biologicals. J Control Release 2011, 151 (3), 220–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parente RA; Nir S; Szoka FC Jr., Mechanism of leakage of phospholipid vesicle contents induced by the peptide GALA. Biochemistry 1990, 29 (37), 8720–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andersen JT; Daba MB; Berntzen G; Michaelsen TE; Sandlie I, Cross-species binding analyses of mouse and human neonatal Fc receptor show dramatic differences in immunoglobulin G and albumin binding. J Biol Chem 2010, 285 (7), 4826–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hong G; Bazin-Redureau MI; Scherrmann JM, Pharmacokinetics and organ distribution of cationized colchicine-specific IgG and Fab fragments in rat. J Pharm Sci 1999, 88 (1), 147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dellian M; Yuan F; Trubetskoy VS; Torchilin VP; Jain RK, Vascular permeability in a human tumour xenograft: molecular charge dependence. Br J Cancer 2000, 82 (9), 1513–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pardridge WM; Kang YS; Diagne A; Zack JA, Cationized hyperimmune immunoglobulins: pharmacokinetics, toxicity evaluation and treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-infected human-peripheral blood lymphocytes-severe combined immune deficiency mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1996, 276 (1), 246–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pardridge WM; Kang YS; Yang J; Buciak JL, Enhanced cellular uptake and in vivo biodistribution of a monoclonal antibody following cationization. J Pharm Sci 1995, 84 (8), 943–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Triguero D; Buciak JL; Pardridge WM, Cationization of immunoglobulin G results in enhanced organ uptake of the protein after intravenous administration in rats and primate. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1991, 258 (1), 186–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Richard JP; Melikov K; Brooks H; Prevot P; Lebleu B; Chernomordik LV, Cellular uptake of unconjugated TAT peptide involves clathrin-dependent endocytosis and heparan sulfate receptors. J Biol Chem 2005, 280 (15), 15300–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tyagi M; Rusnati M; Presta M; Giacca M, Internalization of HIV-1 tat requires cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Biol Chem 2001, 276 (5), 3254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Console S; Marty C; Garcia-Echeverria C; Schwendener R; Ballmer-Hofer K, Antennapedia and HIV transactivator of transcription (TAT) “protein transduction domains” promote endocytosis of high molecular weight cargo upon binding to cell surface glycosaminoglycans. J Biol Chem 2003, 278 (37), 35109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pang HB; Braun GB; Ruoslahti E, Neuropilin-1 and heparan sulfate proteoglycans cooperate in cellular uptake of nanoparticles functionalized by cationic cell-penetrating peptides. Sci Adv 2015, 1 (10), e1500821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prydz K; Dalen KT, Synthesis and sorting of proteoglycans. J Cell Sci 2000, 113 Pt 2, 193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rusnati M; Urbinati C; Caputo A; Possati L; Lortat-Jacob H; Giacca M; Ribatti D; Presta M, Pentosan polysulfate as an inhibitor of extracellular HIV-1 Tat. J Biol Chem 2001, 276 (25), 22420–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khalil IA; Kogure K; Futaki S; Harashima H, High density of octaarginine stimulates macropinocytosis leading to efficient intracellular trafficking for gene expression. J Biol Chem 2006, 281 (6), 3544–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakase I; Tadokoro A; Kawabata N; Takeuchi T; Katoh H; Hiramoto K; Negishi M; Nomizu M; Sugiura Y; Futaki S, Interaction of arginine-rich peptides with membrane-associated proteoglycans is crucial for induction of actin organization and macropinocytosis. Biochemistry 2007, 46 (2), 492–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garg A; Balthasar JP, Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model to predict IgG tissue kinetics in wild-type and FcRn-knockout mice. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2007, 34 (5), 687–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salomone F; Cardarelli F; Signore G; Boccardi C; Beltram F, In vitro efficient transfection by CM(1)(8)-Tat(1)(1) hybrid peptide: a new tool for gene-delivery applications. PLoS One 2013, 8 (7), e70108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salomone F; Breton M; Leray I; Cardarelli F; Boccardi C; Bonhenry D; Tarek M; Mir LM; Beltram F, High-yield nontoxic gene transfer through conjugation of the CM(1)(8)-Tat(1)(1) chimeric peptide with nanosecond electric pulses. Mol Pharm 2014, 11 (7), 2466–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanderson RJ; Hering MA; James SF; Sun MM; Doronina SO; Siadak AW; Senter PD; Wahl AF, In vivo drug-linker stability of an anti-CD30 dipeptide-linked auristatin immunoconjugate. Clin Cancer Res 2005, 11 (2 Pt 1), 843–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burke PJ; Hamilton JZ; Jeffrey SC; Hunter JH; Doronina SO; Okeley NM; Miyamoto JB; Anderson ME; Stone IJ; Ulrich ML, et al. , Optimization of a PEGylated Glucuronide-Monomethylauristatin E Linker for Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Mol Cancer Ther 2017, 16 (1), 116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kovtun YV; Audette CA; Mayo MF; Jones GE; Doherty H; Maloney EK; Erickson HK; Sun X; Wilhelm S; Ab O, et al. , Antibody-maytansinoid conjugates designed to bypass multidrug resistance. Cancer Res 2010, 70 (6), 2528–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simmons JK; Burke PJ; Cochran JH; Pittman PG; Lyon RP, Reducing the antigen-independent toxicity of antibody-drug conjugates by minimizing their non-specific clearance through PEGylation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2020, 392, 114932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tedeschini T; Campara B; Grigoletto A; Bellini M; Salvalaio M; Matsuno Y; Suzuki A; Yoshioka H; Pasut G, Polyethylene glycol-based linkers as hydrophilicity reservoir for antibody-drug conjugates. J Control Release 2021, 337, 431–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abuqayyas L; Balthasar JP, Application of knockout mouse models to investigate the influence of FcgammaR on the tissue distribution and elimination of 8C2, a murine IgG1 monoclonal antibody. Int J Pharm 2012, 439 (1–2), 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eeftens JM; van der Torre J; Burnham DR; Dekker C, Copper-free click chemistry for attachment of biomolecules in magnetic tweezers. BMC Biophys 2015, 8, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hand PH; Robbins PF; Salgaller ML; Poole DJ; Schlom J, Evaluation of human carcinoembryonic-antigen (CEA)-transduced and non-transduced murine tumors as potential targets for anti-CEA therapies. Cancer Immunol Immunother 1993, 36 (2), 65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.