Abstract

Background

In the phase 3 DREAMM-8 study (NCT04484623), belantamab mafodotin (anti-B-cell maturation antigen [BCMA] antibody-drug conjugate with a monomethyl auristatin F payload) with pomalidomide and dexamethasone (BPd) showed significant progression-free survival benefit in second-line or later relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM).

Objective

This exposure-response analysis explored the relationship between belantamab mafodotin cycle 1 exposure and efficacy/safety and predicted the benefit-risk profile of belantamab mafodotin at an initial dose of 1.9 versus 2.5 mg/kg using DREAMM-8 data.

Patients and Methods

In the BPd arm of DREAMM-8, belantamab mafodotin was dosed at 2.5 mg/kg intravenously in cycle 1, then at 1.9 mg/kg every 4 weeks from cycle 2 onward. Cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin and free payload exposures derived from population pharmacokinetic analysis were used to perform exposure-efficacy/exposure-safety analyses for probability of/time to first event. Selected covariate effects were evaluated.

Results

Higher belantamab mafodotin cycle 1 exposure was associated with deeper response (higher probabilities of complete response or better [≥ CR] and minimal residual disease negativity), but not with grade ≥ 3 ocular adverse events (oAEs)/ophthalmic exam findings. Benefit-risk assessment showed that an initial belantamab mafodotin dose of 1.9 mg/kg instead of 2.5 mg/kg would result in reduction in probability of ≥ CR without reduction in oAEs/ophthalmic exam findings.

Conclusions

An initial belantamab mafodotin dose of 2.5 mg/kg for BPd yields deeper responses versus 1.9 mg/kg with minimal change in safety outcomes in RRMM. DREAMM-8 (NCT04484623) was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (21 July 2020)

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11523-025-01174-0.

Key Points

| In the phase 3 DREAMM-8 study, belantamab mafodotin in combination with pomalidomide and dexamethasone (BPd) significantly improved progression-free survival versus pomalidomide with bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with second-line or later (2L+) relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). |

| This exposure-response analysis of the DREAMM-8 study showed that higher belantamab mafodotin concentrations during cycle 1 were associated with deeper responses, and not with probability of or time to grade ≥ 3 eye-related adverse events. |

| Benefit-risk assessment of a 2.5 mg/kg (starting dose used in DREAMM-8) or 1.9 mg/kg initial belantamab mafodotin dose revealed reduced probability of responses with the lower dose, without reduction in probability of eye-related adverse events. These results inform the optimal starting dose of belantamab mafodotin in the BPd regimen, indicating a 2.5 mg/kg initial dose yields deeper responses with minimal change in safety outcomes in patients with 2L+ RRMM. |

Introduction

Belantamab mafodotin is a humanized immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) that targets B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) [1, 2]. The afucosylated antibody is conjugated to the microtubule inhibitor monomethyl auristatin F (MMAF) through a protease-resistant maleimidocaproyl linker (cysteine maleimidocaproyl MMAF [cys-mcMMAF]) [1, 2]. Belantamab mafodotin has multiple mechanisms of action: once it is internalized in a cell, the cytotoxic payload (cys-mcMMAF) is released, causing cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis [1]. In addition, belantamab mafodotin binds to immune effector cells resulting in immune cell recruitment, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, and antibody-dependent phagocytosis [1].

Belantamab mafodotin has been evaluated for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) as monotherapy and in combination regimens [3–5]. DREAMM-8 (NCT04484623) was a phase 3 study in which belantamab mafodotin in combination with pomalidomide and dexamethasone (BPd) significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) and demonstrated higher rates of complete response or better (≥ CR) and minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity compared with pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (PVd) in patients with RRMM previously treated with ≥ 1 prior therapy line including lenalidomide [6].

Ocular events are a known class effect of ADCs with microtubule-inhibiting payloads such as MMAF, MMAE, and DM4 payloads [7–9]. In DREAMM-8, ocular events occurred in 89% of patients who received BPd and were effectively managed with dose modifications [6]. The dose modifications resulted in extended dosing intervals with or without reduction of the belantamab mafodotin dose and allowed patients to remain on treatment and derive robust efficacy benefit [10]. Treatment discontinuation due to ocular events occurred in 9% of patients. Quality of life for patients treated with BPd remained stable over time and was comparable with the control arm [6].

Population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) models of belantamab mafodotin as monotherapy and in combination regimens supported a lack of drug–drug interactions between agents in the BPd regimen [11]. Further, the PopPK analysis showed that belantamab mafodotin exposure is affected by levels of disease-related factors, with higher soluble BCMA (sBCMA), higher IgG, and lower albumin being associated with reduced exposure [11–13]. In addition, exposure-response analyses of belantamab mafodotin monotherapy at 2.5 mg/kg and 3.4 mg/kg doses indicated that higher sBCMA levels were associated with reduced probability of overall response and of grade ≥ 2 corneal events, and that higher belantamab mafodotin exposure was associated more strongly with safety endpoints than efficacy endpoints, supporting use of the lower 2.5 mg/kg monotherapy dose [12, 14].

Using data from the DREAMM-8 study, this analysis aimed to explore the relationship between belantamab mafodotin exposure and efficacy, and that between belantamab mafodotin and cys-mcMMAF exposures and safety. The effect of selected covariates on exposure-response models for efficacy and safety was investigated, and the benefit-risk profile of an initial belantamab mafodotin dose of 1.9 mg/kg or 2.5 mg/kg was determined.

Methods

DREAMM-8 Study Design

This exposure-response analysis (i.e., statistical analysis of the relationship between response and pharmacokinetic [PK] measures of drug exposure) used data from the phase 3 DREAMM-8 trial (data cutoff 29 January 2024). The study design of DREAMM-8 has been previously published [6]. Briefly, patients with RRMM who were lenalidomide-exposed and who received at least one prior line of therapy were randomized 1:1 to BPd (belantamab mafodotin 2.5 mg/kg intravenously on day 1 of the first 28-day cycle [every 4 weeks; Q4W] and 1.9 mg/kg Q4W thereafter; pomalidomide 4 mg orally on days 1–21 Q4W; dexamethasone 40 mg orally on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 Q4W) or PVd (dosing described in the Supplementary Materials). Patients who received BPd were included in exposure-safety analyses if they received at least one dose of belantamab mafodotin and had a measurable PK sample available, and in exposure-efficacy analyses if in addition to the above, they had measurable disease at baseline.

DREAMM-8 was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment, and the trial protocol and amendments were approved by the appropriate ethics body at each participating institution.

Exposure Measures and Exposure-Response Endpoints

Only cycle 1 exposures were considered for exposure-response analyses to ensure consistency in exposure metrics regardless of time on study and mitigate the risk for bias and confounding associated with exposures from later time points [15]; prior PopPK models have shown that belantamab mafodotin clearance changed over time, decreasing as disease burden was reduced [11], which may lead to increased exposure over the course of treatment. Further, dose modifications due to adverse events may also affect exposure over time. Cycle 1 exposure considers between-patient variability in PK, without being influenced by time-varying PK or dose modifications.

Belantamab mafodotin and payload (cys-mcMMAF) exposure measures were derived using the individual post-hoc cycle 1 PK parameter estimates obtained from the PopPK analysis [11]. These were maximum concentration (Cmax) after the first dose, concentration at the end of 28 days (Ctau28; measured for full belantamab mafodotin ADC only), and average concentration (Cavg) over the first dosing interval. Exposure-response analyses for efficacy were conducted using belantamab mafodotin ADC exposure measures only and included the endpoints of PFS, probability of response (overall response, very good partial response or better [≥ VGPR], ≥ CR, MRD negativity at ≥ CR), duration of response (DOR), and time to response (TTR). Patients that were nonevaluable were considered as nonresponders for probability of response endpoints and were censored for time to event efficacy endpoints.

Exposure-response analyses for safety were undertaken using belantamab mafodotin and cys-mcMMAF exposure measures. Safety endpoints included probability of any and time to first grade ≥ 2 and grade ≥ 3 ocular adverse events (oAEs), assessed per National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), as well as ophthalmic exam findings (OEFs), which included corneal exam findings and best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) graded by the sponsor per the keratopathy and visual acuity (KVA) scale. OEFs were evaluated overall and individually (grade ≥ 2 and grade ≥ 3 corneal exam findings and BCVA events, probability of worsening in BCVA to 20/50 or worse in one or both eyes, and definite worsening in BCVA [ΔlogMar ≥ 0.3 in the better-seeing eye]). Other endpoints for the exposure-response safety analyses included grade ≥ 3 thrombocytopenia, dose modification due to treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs), dose discontinuation, dose reduction, and dose delay/interruption. Exposure-response analyses were not performed for endpoints with low (≤ 10%) or high (≥ 90%) incidence rate.

Covariates for Exposure-Response Analyses

The impact of covariates with potential to affect exposure-response relationships was also evaluated. Covariates of interest included: weight, body mass index (BMI), age, race (White, Asian, and Northeast Asian), gender, region, albumin, serum IgG, renal function category, hepatic function category by NCI Organ Dysfunction Working Group Index (normal versus mild/moderate/severe impairment) [16], type of myeloma immunoglobulin (IgG versus others), cytogenetic risk category (standard, high risk [defined as the presence of at least one high-risk abnormality: t(4;14), t(14;16), or del(17p13)]), sBCMA (baseline sBCMA levels that were below the limit of quantification of the GSK ELISA assay were imputed to half the lower limit of quantification [0.975 ng/mL]), β2-microglobulin, lactate dehydrogenase, disease stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, presence of extramedullary disease (EMD), number of prior lines of therapy, prior anti-CD38 treatment, prior bortezomib treatment, refractory to both immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors, and refractory to lenalidomide. Known history of dry eye per screening questionnaire, presence of keratopathy at baseline exam, baseline BCVA in better eye and in worse eye were covariates evaluated only for oAE/OEF endpoints, and baseline platelet count was evaluated only for the thrombocytopenia endpoint.

Statistical Analysis

All exposure-response analyses were performed using R (version 4.1.3 or higher). Logistic regression models were used to determine the relationship between belantamab mafodotin/cys-mcMMAF exposure measures and the probability of efficacy or safety endpoints occurring. Kaplan–Meier plots of time to event endpoints were generated and stratified by belantamab mafodotin/cys-mcMMAF exposure measure quartiles. Cox proportional hazards (CPH) models were also used to determine the relationship between belantamab mafodotin/cys-mcMMAF exposure measures and time to event endpoints.

Covariate analyses were performed for both logistic regression models and CPH models using the stepwise forward addition and backward elimination procedure. Covariates were individually included in the model, in a univariate step, to identify significant covariates at an alpha of 0.01 (corresponding to a reduction in the objective function value [OFV] of ≥ 6.64 for 1 degree of freedom). Only significant covariates in the univariate step were included in the stepwise covariate search. The most significant covariate was included in the model first. This new model then served as a starting model for the next iteration, and the process continued until all significant covariates (alpha of 0.01) were included and the full model was defined. Only the most significant exposure measure at the step where the covariate entered the model was selected. After the full model was defined, the significance of each covariate was tested by individual backward elimination from the full model. A covariate was retained if it was significant at the 0.001 alpha level (corresponding to an OFV increase of > 10.83 points for 1 degree of freedom). The elimination steps were repeated until all nonsignificant covariates were excluded, and the final model was defined. The definition of a typical patient, and changes from the typical exposure and covariate values that were used to compute odds ratios and hazard ratios (HRs) are described in the Supplementary Methods.

A covariate could be retained in the final model regardless of significance if there was strong pharmacological or physiological rationale. If the final model for an endpoint included a belantamab mafodotin cycle 1 exposure measure other than ADC Cavg, a model replacing the exposure measure with ADC Cavg was also generated to allow model comparison across endpoints. If the model using ADC Cavg provided a similar fit to the data as the model using a different exposure parameter, ADC Cavg superseded the other parameter.

Integrated Efficacy and Safety Exposure-Response Analysis

Integrated exposure-response plots were generated for visual benefit-risk assessment. As a metric for depth-of-response, the exposure-response curve for probability of ≥ VGPR was overlaid with the exposure-response curves for probability of grade ≥ 3 oAEs, probability of BCVA worsening to 20/50 or worse in both eyes, and probability of grade ≥ 3 OEFs. A multivariate model-predicted benefit-risk assessment of a 1.9 mg/kg versus 2.5 mg/kg initial dose of belantamab mafodotin was also performed. For this assessment, cycle 1 ADC exposures for the 2.5 mg/kg dose were derived from post-hoc simulation using the final PopPK model [11], and cycle 1 ADC exposures for the 1.9 mg/kg dose were calculated using a linear proportion assumption. Using the typical patient characteristics and the exposure-response models, probabilities (along with 95% prediction intervals) of efficacy and safety endpoints were predicted.

Results

Patient Population

Overall, the exposure-response analysis included 150 patients, comprising all BPd-treated patients from the DREAMM-8 study. Baseline demographics and covariates are summarized in Table 1. Most patients were male (65.3%), median age was 66 years (range 40–82), EMD was present in 13% of patients, 56% had myeloma IgG, median sBCMA was 38.3 ng/mL (range 0.975–741; one patient imputed to 0.975 due to value below quantification limit), and 24% received prior anti-CD38 treatment.

Table 1.

Summary of efficacy and safety covariates for patients included in the exposure-response analysis

| N = 150 | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Median (range) | 66.0 (40.0, 82.0) |

| < 65 | 64 (42.7) |

| 65 to < 75 | 70 (46.7) |

| ≥ 75 | 16 (10.7) |

| Male, n (%) | 98 (65.3) |

| Myeloma immunoglobulin, n (%) | |

| IgA | 39 (26.0) |

| IgG | 84 (56.0) |

| IgM | 2 (1.3) |

| Other | 25 (16.7) |

| International Staging System (ISS) at screening, n (%) | |

| I | 92 (61.3) |

| II | 37 (24.7) |

| III | 20 (13.3) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.7) |

| Baseline ECOG PS, n (%) | |

| 0 | 79 (52.7) |

| 1 | 67 (44.7) |

| 2 | 4 (2.7) |

| Cytogenetic risk categories, n (%) | |

| Standard | 71 (47.3) |

| High risk | 49 (32.7) |

| Missing or not evaluable | 30 (20.0) |

| Extramedullary disease, n (%) | 20 (13.3) |

| Refractory to both immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors, n (%) | 33 (22.0) |

| Hepatic function, n (%)a | |

| Normal | 134 (89.3) |

| Mild impairment | 15 (10.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.7) |

| Prior lines of therapy, n (%) | |

| 1 | 80 (53.3) |

| 2 | 30 (20.0) |

| 3 | 22 (14.7) |

| ≥ 4 | 18 (12.0) |

| Prior anti-CD38 treatment, n (%) | 36 (24.0) |

| Prior bortezomib treatment, n (%) | 131 (87.3) |

| History of dry eye, n (%) | 24 (16.0) |

| Presence of keratopathy at baseline, n (%) | |

| None | 127 (84.7) |

| Mild | 23 (15.3) |

| Corneal event management, n (%) | |

| Managed by KVA | 72 (48.0) |

| Managed by CTCAE | 8 (5.3) |

| Started with CTCAE and changed to KVA | 70 (46.7) |

| Baseline body weight, kg, median (range) | 76.8 (46.0, 123) |

| Baseline BMI, kg/m2, median (range) | 26.8 (17.6, 43.0) |

| Baseline sBCMA, ng/mL, median (range) | 38.3 (0.975, 741) |

| Baseline IgG, g/L, median (range) | 11.6 (0.650, 96.3) |

| Baseline albumin, g/L, median (range) | 41.0 (25.0, 52.0) |

| Baseline lactate dehydrogenase, U/L, median (range) | 188 (68.6, 1380) |

| Baseline β2 microglobulin, nmol/L, median (range) | 234 (121, 1340) |

| Baseline M-protein, g/L, median (range) | 15.0 (0.100, 83.7) |

| Baseline platelet count, 109/L, median (range) | 172 (35.0, 520) |

| Baseline BCVA best eye, logMAR, median (range) | 0 (−0.204, 0.301) |

| Baseline BCVA worst eye, logMAR, median (range) | 0.0969 (−0.204, 1.30) |

BCVA best corrected visual acuity, BMI body mass index, CTCAE Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, IgA immunoglobulin A, IgG immunoglobulin G, IgM immunoglobulin M, KVA keratopathy and visual acuity, logMAR logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution, sBCMA soluble B-cell maturation antigen.

aPer National Cancer Institute-Organ Dysfunction Working Group classification [16].

Efficacy Exposure-Response Analysis

Progression-free Survival

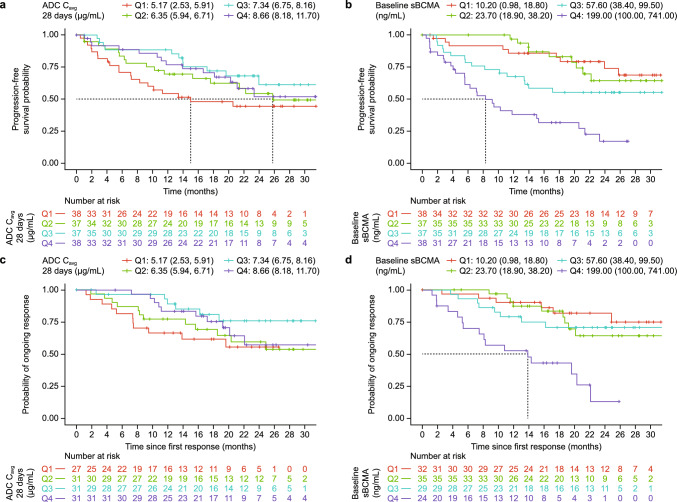

Exposure-response analysis of PFS included all 150 patients. The Kaplan–Meier curve for quartiles of cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg showed that the shortest PFS was observed in the lowest exposure quartile (median Cavg quartiles ranged from 5.17–8.66 μg/mL), but no strong exposure-response trend was observed overall (Fig. 1a). Stepwise Cox regression modeling also found no significant association between exposure and PFS but suggested that higher baseline sBCMA was associated with shorter PFS (HR 1.08 [95% confidence interval; 95% CI 1.05–1.11] for a 20 ng/mL increase in sBCMA; Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Progression-free survival stratified by cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg quartile (a) and baseline sBCMA quartile (b). Duration of response stratified by cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg quartile (c) and baseline sBCMA quartile (d). Quartiles are reported as median (minimum, maximum). ADC antibody-drug conjugate, sBCMA soluble B-cell maturation antigen, Cavg average concentration over the dosing interval, Q quartile

Probability of Response

The analysis of overall response included all 150 patients, 2 (1.3%) of which were nonevaluable and considered nonresponders and 120 (80%) of whom were responders. A response of ≥ VGPR was achieved in 99 patients (66%), ≥ CR in 62 patients (41%), and MRD negativity at ≥ CR in 37 patients (25%).

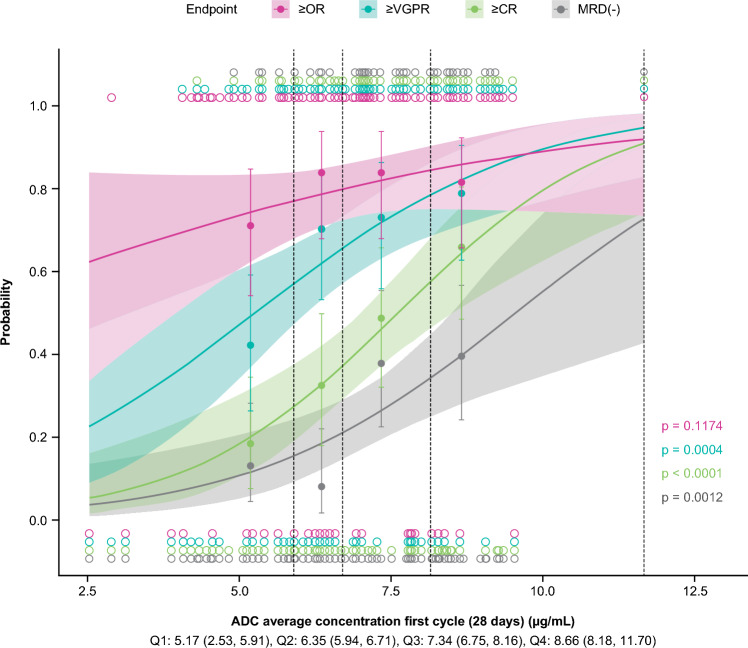

While the logistic regression model suggested the lowest exposure quartile had a numerically lower probability of response compared with the higher exposure quartiles, probability of achieving an overall response was not significantly associated with cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg (Fig. 2). No covariates were identified as having a significant effect on probability of overall response (Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between probabilities of clinical response and cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg. The independent variable was divided into quartiles. Quartiles are reported as median (minimum, maximum). Points and error bars represent the observed proportions and 95% confidence intervals for each quartile (plotted at the median exposure within each quartile), respectively. The curves represent the prediction of the univariate logistic regression model, and the shaded region represents the 95% confidence interval of the prediction. The displayed p-value is for the logistic regression slope. ADC, antibody-drug conjugate; Cavg, average concentration over the dosing interval; ≥ CR, complete response or better; MRD, minimal residual disease; ≥ OR, overall response or better; Q, quartile; ≥ VGPR, very good partial response or better

The probability of a response of ≥ VGPR appeared to increase with increasing cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg (Fig. 2). While probability of ≥ VGPR response was associated with increasing cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Ctau in the full model, this association did not meet the significance criteria for inclusion in the final model. Presence of EMD was significantly associated with a decreased probability of ≥ VGPR (odds ratio 0.0378 [95% CI 0.00581–0.14]; Supplementary Table S1); additional analyses found that patients with EMD had significantly lower Cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg (p = 0.0005) and baseline albumin (p = 0.007) and significantly higher baseline sBCMA (p = 0.0009) on the basis of a Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test.

Higher cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg was significantly associated with higher probability of ≥ CR (odds ratio 3.4 [95% CI 1.98–6.24]; Fig. 2). In addition, prior anti-CD38 treatment was significantly associated with a lower probability of ≥ CR (odds ratio 0.183 [95% CI 0.0606–0.476]) (Supplementary Table S1). Higher cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg was also significantly associated with higher probability of MRD negativity (odds ratio 2.53 [95% CI 1.48–4.58]; Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1). No other covariates met the significance criteria for association with MRD negativity.

Of note, univariate analyses for probabilities of ≥ CR and MRD negativity showed inverse trends with baseline sBCMA (CR: p = 0.012; MRD: p = 0.023) and EMD (CR: p < 0.001; MRD: p = 0.012), but these trends did not meet significance at later steps for these endpoints.

Time to Response

Analyses of TTR included the 120 patients who achieved a response. The Kaplan–Meier curve for cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg indicated that TTR was longest in the lowest Cavg quartile (Fig. 3); however, stepwise Cox regression modeling found no significant relationship between exposure and TTR. Presence of myeloma type IgG (HR 0.406 [95% CI 0.276–0.597]) and EMD (HR 0.271 [95% CI 0.135–0.547]) were significantly associated with longer TTR (Supplementary Table S1). Of note, patients with higher baseline IgG levels had significantly lower cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg (p < 0.0001).

Fig. 3.

Time to response stratified by cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg quartile. Quartiles are reported as median (minimum, maximum). ADC antibody-drug conjugate, Cavg average concentration over the dosing interval, Q quartile

Duration of Response

The 120 responders were included in exposure-response analyses for DOR. The Kaplan–Meier analysis showed the shortest DOR with the lowest belantamab mafodotin Cavg quartile (Fig. 1c). Stepwise Cox regression modeling found no significant relationship between exposure and DOR, while higher baseline sBCMA (HR 1.09 [95% CI 1.05–1.12]) and prior anti-CD38 treatment (HR 3.56 [95% CI 1.78–7.12]) were significantly associated with shorter DOR (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table S1).

Safety Exposure-Response Analysis

Ocular Adverse Events (CTCAE-Graded)

Grade ≥ 3 oAEs occurred in 64 (43%) patients treated with BPd in DREAMM-8 (Supplementary Table S2). Logistic regression modeling of cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin and cys-mcMMAF exposures showed no clear association with the probability of these events (Fig. 4), and no covariate associations were identified. Summaries of the final models for oAEs are presented in Supplementary Table S3.

Fig. 4.

Relationship between probability of ≥ VGPR, oAEs, OEFs, and cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg. The independent variable was divided into quartiles. Quartiles are reported as median (minimum, maximum). Points and error bars represent the observed proportions and 95% confidence intervals for each quartile (plotted at the median exposure within each quartile), respectively. The curves represent the prediction of the univariate logistic regression model, and the shaded region represents the 95% confidence interval of the prediction. The displayed p-value is for the logistic regression slope. ADC antibody-drug conjugate, BCVA best corrected visual acuity, Cavg average concentration over the dosing interval, KVA keratopathy and visual acuity, oAE ocular adverse event, OEF ophthalmic exam finding, Q quartile; ≥ VGPR very good partial response or better

Kaplan–Meier analyses showed no clear trends, and stepwise Cox regression indicated that cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin and cys-mcMMAF exposures were not associated with the time to first grade ≥ 3 oAE. Although baseline age was not associated with probability of grade ≥ 3 oAEs, it was associated with time to these events, where earlier occurrence was most highly associated with older age (≥ 75 years; HR 2.29 [95% CI 1.17–4.51]), followed by younger age (< 65 years). Age 65 to < 75 was associated with longer time to event (HR 0.538 [95% CI 0.31–0.931]).

Grade ≥2 oAE analyses are reported in Supplementary Table S3.

Ophthalmic Exam Findings (KVA-Graded)

Grade ≥ 3 OEFs occurred in 116 (77%) BPd-treated patients. Logistic regression indicated that cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin exposure (Fig. 4), cys-mcMMAF exposure, and covariates did not appear to affect the probability of these events. In Kaplan–Meier analysis, the time to first grade ≥ 3 OEF appeared to be shorter with higher cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin exposure, but this did not meet significance using stepwise Cox regression; neither cycle 1 cys-mcMMAF exposures nor covariates were associated with this endpoint. Summaries of the final models for OEFs are presented in Supplementary Table S3.

Grade ≥ 3 worsening of BCVA occurred in 90 (60%) patients. While logistic regression showed patients with these events had slightly higher belantamab mafodotin exposures, and there was a small trend for decreasing probability of event with increasing cys-mcMMAF exposures, neither exposure metric was significant. EMD was the only significant covariate and was associated with reduced probability of grade ≥ 3 BCVA worsening event (odds ratio 0.128 [0.035–0.373]). Kaplan–Meier analyses found no trends, and stepwise Cox regression found that no exposure measures or endpoints were associated with time to grade ≥ 3 BCVA event.

Worsening of BCVA to 20/50 or worse in both eyes regardless of baseline status occurred in 60 (40%) patients. Logistic regression revealed no exposure measure nor covariate that was significantly associated with probability of this worsening.

There was grade ≥ 3 corneal exam findings in 93 (62%) patients. While logistic regression showed patients with these findings tended to have higher belantamab mafodotin exposures, no exposure measure or any covariate was significant for the probability of these findings. Similarly, Kaplan–Meier analysis showed a trend for earlier grade ≥ 3 corneal exam findings with higher belantamab mafodotin exposures, but stepwise Cox regression found no significant associations with time to these exam findings.

Additional OEF endpoints (grade ≥ 2 events, worsening BCVA defined by ΔlogMar ≥ 0.3 in the better-seeing eye and worsening of BCVA to 20/50 or worse in one eye) are reported in Supplementary Table S3.

Thrombocytopenia

Grade ≥ 3 thrombocytopenia occurred in 60 (40%) patients in the BPd arm. Logistic regression indicated that cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin and cys-mcMMAF exposures were not associated with probability of these events. Higher baseline platelet count was significantly associated with a lower probability of grade ≥ 3 thrombocytopenia (odds ratio 0.672 [95% CI 0.558–0.791]). A summary of the final model for thrombocytopenia is presented in Supplementary Table S4.

Dose Modifications of Any Drug in the BPd Combination

Dose modifications occurred in 124 (83%) BPd-treated patients, including 89 (59%) patients with dose reductions, 120 (80%) with dose delays, and 19 (13%) patients who discontinued treatment. Logistic regression showed that higher cycle 1 cys-mcMMAF Cmax was associated with lower probability of dose modification due to TEAE (odds ratio 0.723 [95% CI 0.582–0.866]). Higher cycle 1 cys-mcMMAF Cmax was also significantly associated with higher baseline sBCMA (p < 0.0001). Patients who had a dose modification had a trend of slightly higher cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg, but no significant association was found between cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin exposure and probability of dose modification. No covariate was associated with this endpoint. Summaries of the final models for dose modifications are presented in Supplementary Table S4.

Patients who had a dose reduction had slightly higher cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin exposures and lower cys-mcMMAF exposures compared with those who did not have a dose reduction, but this did not meet significance criteria. Increased baseline β2 microglobulin was significantly associated with decreased probability of dose reduction (odds ratio 0.653 [95% CI 0.48–0.839]).

The probability of dose delay was significantly associated with higher cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cmax; this exposure parameter was replaced by cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg due to similar fit of the data (odds ratio 1.95 [95% CI 1.15–3.43]). There was a slight trend of decreasing probability as cys-mcMMAF exposures increased, but this did not meet significance criteria, nor did any covariate association.

Cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin and cys-mcMMAF exposures were not associated with the probability of treatment discontinuation. Baseline International Staging System stage II or III disease was significantly associated with lower probability of dose discontinuation (odds ratio 0.0721 [95% CI 0.00395–0.365]).

Integrated Analysis of Exposure-Response for Efficacy and Safety (Benefit-Risk Assessment)

Efficacy and safety endpoints were integrated for visual benefit-risk assessment (Fig. 4). Exposure-response model-generated probability of ≥ VGPR, grade ≥ 3 oAEs, and grade ≥ 3 OEFs appeared to increase with increasing cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg exposure, whereas probability of BCVA worsening to 20/50 or worse in both eyes remained relatively consistent. The probability of ≥ VGPR was higher than the probability of grade ≥ 3 oAEs and BCVA worsening to 20/50 or worse in both eyes at most cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg quartiles. The probability of grade ≥ 3 OEFs was higher than the probability of ≥ VGPR at lower cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg quartiles, but the probabilities became similar at higher quartiles.

Multivariate model predictions suggested that an initial belantamab mafodotin dose of 1.9 mg/kg compared with 2.5 mg/kg would lead to a reduced probability of ≥VGPR (−5.5%) and ≥ CR (−21.6%) response, with no reduction in probabilities of grade ≥ 3 oAEs, grade ≥ 3 OEFs, or BCVA worsening to 20/50 or worse in both eyes (Table 2).

Table 2.

DREAMM-8 exposure-response based benefit-risk assessmenta

| Initial belantamab mafodotin dose | ||

|---|---|---|

| Probability with 95% CI (%) | 1.9 mg/kg | 2.5 mg/kg |

| ≥ VGPR | 74.5 (62.5–83.7) | 80.0 (70.6–87.0) |

| ≥ CR | 23.5 (13.6–37.4) | 45.1 (35.3–55.2) |

| Grade ≥ 3 ocular adverse event (CTCAE) | 42.7 (35.0–50.7) | 42.7 (35.0–50.7) |

| BCVA worsening to 20/50 or worse in both eyes regardless of BCVA status at baseline | 40.0 (32.5–48.0) | 40.0 (32.5–48.0) |

| Grade ≥ 3 OEFs (KVA) | 77.3 (70.0–83.3) | 77.3 (70.0–83.3) |

aCycle 1 belantamab mafodotin exposures for the 2.5 mg/kg dose (Ctau: 1.57 μg/mL; Cavg: 6.7 μg/mL) are derived from post hoc simulation using the final population PK model [11]. Cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin exposures for the 1.9 mg/kg dose (Ctau: 1.19 μg/mL; Cavg: 5.09 μg/mL) were calculated using a linear proportion assumption.

BCVA best corrected visual acuity, Cavg average concentration over the dosing interval, ≥ CR compete response or better, Ctau concentration at the end of the dosing interval, CTCAE Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, KVA keratopathy and visual acuity, PK pharmacokinetic, ≥ VGPR very good partial response or better.

Discussion

The DREAMM-8 trial investigated the efficacy and safety of BPd versus PVd in patients with RRMM who received at least 1 prior line of therapy including lenalidomide [6]. Patients received belantamab mafodotin 2.5 mg/kg for cycle 1, followed by 1.9 mg/kg Q4W thereafter; other components of the regimens were administered at their approved dose and schedule. This exposure-response analysis characterized the exposure-efficacy and exposure-safety relationships in patients who received BPd in the DREAMM-8 study.

Higher cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg was associated with a higher probability of ≥ CR and MRD negativity at ≥ CR, indicating that higher starting dose intensity is important to achieve deeper response. While studies have shown that deeper responses lead to longer PFS [17], no significant association was found between cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin exposure measures and PFS, DOR, or TTR. However, the numerical trend of shorter PFS and DOR at lower exposures may suggest that probability of PFS and DOR were maximized at higher exposure levels. It is also important to note that univariate analyses found associations between probability of ≥ CR or MRD negativity and baseline sBCMA (CR: p = 0.012; MRD: p = 0.023) or EMD (CR: p < 0.001; MRD: p = 0.012), but the association of these endpoints with exposure was stronger (CR: p < 0.001, MRD: p = 0.001), in part because response was not maximized at lower exposures, as observed for PFS and DOR. In contrast, higher cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin exposure was not associated with significant grade ≥ 3 oAEs or OEFs. Higher cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg was associated with increased probability of dose delay, but not with dose reduction or treatment discontinuation. At the same time, multivariate model predictions suggested that a lower starting dose of 1.9 mg/kg decreases the probability of response (5% reduction in ≥ VGPR and 22% reduction in ≥ CR probabilities) compared with a 2.5 mg/kg dose, with no decrease in the probability of grade ≥ 3 oAEs, grade ≥ 3 OEFs, or BCVA worsening to 20/50 or worse in both eyes. The integrated benefit-risk assessment also indicated that while the probability of oAEs and OEFs was relatively high across exposure levels, probability of ≥ VGPR became higher than the risk for grade ≥ 3 oAEs and BCVA worsening to 20/50 or worse in both eyes, and similar to the risk for grade ≥ 3 OEFs at higher cycle 1 exposures. The steeper exposure-response curve for the efficacy endpoint and shallower exposure-response curve for the safety endpoints suggest that a higher dose has a more favorable benefit-risk profile. This indicates that the initial dose of 2.5 mg/kg belantamab mafodotin is predicted to show deeper responses compared with 1.9 mg/kg with no additional risk, supporting the cycle 1 dosing used in DREAMM-8.

Prior analyses have shown that factors such as higher baseline IgG, higher baseline sBCMA, and lower baseline levels of albumin, which are indicative of higher multiple myeloma disease burden, are associated with higher belantamab mafodotin (ADC) clearance and thereby lower exposure to the ADC [11]; the significantly lower cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg in patients with EMD and patients with higher IgG levels at baseline in the current analysis is consistent with these prior findings. Patients with EMD also had significantly lower albumin and higher sBCMA levels, which could further contribute to reduced exposure. These findings may also explain the time-dependent decrease in clearance of belantamab mafodotin, as disease burden decreases with time on treatment in responding patients. The dependence of belantamab mafodotin clearance on disease burden may explain the relatively high interindividual variability in blood levels of belantamab mafodotin (30.6% variation from the geometric mean for cycle 1 Cavg21 in patients who received 2.5 mg/kg [11]. In addition, this may help explain why the recommended dose modifications in response to ocular events, which led to a decrease in dose intensity with increasing time on treatment, did not impact the efficacy [18]. Because markers of disease burden were associated with efficacy and safety endpoints (higher sBCMA levels with lower probability of PFS and shorter DOR; IgG myeloma with longer TTR; presence of EMD with lower probability of ≥ VGPR, longer TTR, and presence of EMD with lower probability of grade ≥ 3 BCVA worsening event; increased β2 microglobulin with lower probability of dose reduction, and advanced International Staging System (ISS) stage and lower probability of drug discontinuation), there is potential that the effect of these baseline covariates on belantamab mafodotin exposure led to confounding of the exposure-efficacy analyses. In particular, while patients with EMD represented only a small proportion of the analysis population (13%), the high association between EMD and Cavg (p = 0.0005) may explain the association found between probability of ≥ VGPR and EMD, but not exposure.

Overall, the findings from these analyses suggest that the current approach of initiating belantamab mafodotin at a 2.5 mg/kg dose in cycle 1, stepping down to 1.9 mg/kg Q4W from cycle 2 onward, and implementing further dose modifications as required to manage oAEs, optimizes the benefit versus risk of BPd over time. In the DREAMM-8 study, dose modifications led to extended belantamab mafodotin dosing intervals with time on treatment, with corresponding reduction in belantamab mafodotin dose intensity [6]. The aforementioned association between disease burden and belantamab mafodotin clearance [11] supports this approach of a high initial dose intensity to achieve adequate exposure and response; as disease burden decreases over subsequent cycles, belantamab mafodotin clearance reduces and the dose intensity may be reduced. It is important to consider that adopting a one-size-fits-all stepdown approach beyond the initial stepdown to 1.9 mg/kg Q4W will be challenging given the high interindividual variability in exposure and time-dependent clearance. Modifying the dose as required to manage oAEs in a given patient helps to optimize dosing for each patient.

oAEs and OEFs are common with MMAF ADCs, including belantamab mafodotin [7–9, 19–21]. Studies suggest these events occur due to nonspecific uptake of belantamab mafodotin into the corneal cells by macropinocytosis, and the subsequent release of MMAF within the corneal cells [19–21]. Lack of impact of cycle 1 cys-mcMMAF exposure on oAEs/OEFs (any associations observed were likely artifact) suggests that cys-mcMMAF likely has low permeability across the corneal cell membranes [22], and the nonspecific uptake of belantamab mafodotin ADC into the corneal cells is the driver for oAEs/OEFs. This pharmacology, combined with increased baseline disease severity (sBCMA) in patients with increased cycle 1 cys-mcMMAF may explain the relationship between higher cycle 1 cys-mcMMAF Cmax in plasma and lower probability of dose modification due to TEAEs: patients with a higher cys-mcMMAF Cmax and baseline disease severity had lower drug exposure, and thus reduced oAEs/OEFs events that result in dose modification.

Strengths of the analysis included the large patient cohort and incorporation of multiple efficacy and safety endpoints and clinically relevant covariates. Our analysis used cycle 1 exposure metrics to mitigate the confounding of steady-state exposure by the time-dependent decrease in clearance and extended dosing intervals of belantamab mafodotin; the latter are associated with considerable interindividual variability in exposure. While cycle 1 exposures are limited in that they do not capture dose modifications, they were considered superior in this study to alternate exposure measures [23]. Time to event exposures introduce selection bias [24] and landmark exposures (e.g., 3- and 6-month) result in loss of data from patients who are not on study during the landmark. Steady-state exposures cannot be captured due to frequent dose modifications and given the multimodal mechanism of action of belantamab mafodotin, particularly the immune-mediated effects that are likely to be sustained [25], a steady-state exposure to belantamab mafodotin may not be required for its action. Further, the majority of belantamab mafodotin-related safety events and responses to treatment occur within the first one to two cycles of treatment [3, 5, 6]. Therefore, this analysis relied on interindividual variability within a single cycle 1 dose level to explore the impact of exposure on various safety and efficacy responses. Future work may consider a concentration vector to predict event endpoints.

We also acknowledge the limitations of our analysis. We analyzed the relationship between belantamab mafodotin exposure and response without factoring in the exposure of the combination partners within the BPd regimen. In addition, while the stringent significance criteria for inclusion of covariates in the final model allowed for increased confidence in the results, it also led to the exclusion of potentially relevant covariates. For example, the relationship between cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin Cavg and probability of ≥ VGPR did not meet the significance level required for inclusion in the final ≥ VGPR model despite a p-value of 0.0004 in a univariate logistic regression. Fixing exposures into each model may have ensured interpretation of the effect of exposure for each endpoint, but this would assume that exposure is always related to efficacy or safety responses. Further, this may have resulted in fewer significant covariates being identified due to the correlation between exposure and many covariates.

To further inform the exposure-response relationship of belantamab mafodotin in combination regimens and starting dose levels, future work could include a meta-analysis of the available exposure-response data across belantamab mafodotin multiple myeloma studies [12, 14]. Such research would need to take into account differences in underlying disease across the studies.

This exposure-response analysis identified a relationship between higher cycle 1 belantamab mafodotin exposures and deeper responses, but not with grade ≥ 3 oAEs/OEFs. The integrated benefit-risk assessment demonstrated reduced responses and no reduction in grade ≥ 3 oAEs/OEFs with an initial belantamab mafodotin dose of 1.9 mg/kg compared to 2.5 mg/kg, supporting the initial dose used in the DREAMM-8 study.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, including preparation of the draft manuscript under the direction and guidance of the authors, collating and incorporating authors’ comments for each draft, assembling tables and figures, grammatical editing and referencing) was provided by Alexus Rivas-John, PharmD, at Fishawack Indicia Ltd, part of Avalere Health, and was funded by GSK. This study (207499) and the analyses reported herein were funded by GSK. Drug linker technology licensed from Seagen Inc.; monoclonal antibody produced using POTELLIGENT Technology licensed from BioWa.

Declarations

Funding

Study 207499 and the analyses reported herein were funded by GSK. Drug linker technology licensed from Seagen Inc.; monoclonal antibody produced using POTELLIGENT Technology licensed from BioWa.

Conflicts of Interest

P. Hanafin, Y.L. Ho, T. Papathanasiou, G. Fulci, N. Sule, B.E. Kremer, and G. Ferron-Brady are employees of and hold financial equities in GSK.

Ethics Approval

The DREAMM-8 trial protocol and amendments were approved by the appropriate ethics body at each participating institution.

Consent to Participate

All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment in DREAMM-8.

Consent for Publication

N/A

Data Availability

GSK makes available anonymized individual participant data and associated documents from interventional clinical studies that evaluate medicines, upon approval of proposals submitted to https://www.gsk-studyregister.com/en/.

Code Availability

N/A.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and design: P. Hanafin, Y.L. Ho, T. Papathanasiou, G. Fulci, N. Sule, B.E. Kremer, and G. Ferron-Brady; Data collection and analysis: P. Hanafin, Y.L. Ho, T. Papathanasiou, G. Fulci, N. Sule, B.E. Kremer, and G. Ferron-Brady; Writing—review and editing: P. Hanafin, Y.L. Ho, T. Papathanasiou, G. Fulci, N. Sule, B.E. Kremer, and G. Ferron-Brady. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Alexus Rivas-John and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Montes de Oca R, Alavi AS, Vitali N, Bhattacharya S, Blackwell C, Patel K, et al. Belantamab mafodotin (GSK2857916) drives immunogenic cell death and immune-mediated antitumor responses in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2021;20(10):1941–55. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tai YT, Anderson KC. Targeting B-cell maturation antigen in multiple myeloma. Immunotherapy. 2015;7(11):1187–99. 10.2217/imt.15.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimopoulos MA, Hungria VTM, Radinoff A, Delimpasi S, Mikala G, Masszi T, et al. Efficacy and safety of single-agent belantamab mafodotin versus pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (DREAMM-3): a phase 3, open-label, randomised study. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10(10):e801–12. 10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hungria V, Robak P, Hus M, Zherebtsova V, Ward C, Ho PJ, et al. Belantamab mafodotin, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(5):393–407. 10.1056/NEJMoa2405090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nooka AK, Cohen AD, Lee HC, Badros A, Suvannasankha A, Callander N, et al. Single-agent belantamab mafodotin in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: final analysis of the DREAMM-2 trial. Cancer. 2023;129(23):3746–60. 10.1002/cncr.34987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimopoulos MA, Beksac M, Pour L, Delimpasi S, Vorobyev V, Quach H, et al. Belantamab mafodotin, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(5):408–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa2403407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson JA, Motzer RJ, Molina AM, Choueiri TK, Heath EI, Redman BG, et al. Phase I trials of anti-ENPP3 antibody-drug conjugates in advanced refractory renal cell carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(18):4399–406. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominguez-Llamas S, Caro-Magdaleno M, Mataix-Albert B, Aviles-Prieto J, Romero-Barranca I, Rodriguez-de-la-Rua E. Adverse events of antibody-drug conjugates on the ocular surface in cancer therapy. Clin Transl Oncol. 2023;25(11):3086–100. 10.1007/s12094-023-03261-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao K, Chen P, Sun H, Zhong S, Zheng H, Xu L. Ocular adverse events associated with antibody-drug conjugates in oncology: a pharmacovigilance study based on FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS). Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1425617. 10.3389/fphar.2024.1425617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mateos MV, Trudel S, Quach H, Robak P, Beksac M, Pour L, et al. (2025) Modification of belantamab mafodotin dosing to balance efficacy and tolerability in the DREAMM-7 and DREAMM-8 trials. Blood Adv:In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Papathanasiou T, Kaullen J, Polireddy K, Chen X, Ho Y, Taylor A, et al. Population pharmacokinetics for belantamab mafodotin monotherapy and combination therapies in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2025;64(6):925–42. 10.1007/s40262-025-01508-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferron-Brady G, Taylor A, Kaullen J, Polireddy K, McKeown A, Sule N, et al. Population pharmacokinetics (PopPK) and exposure-response (E-R) analyses for belantamab mafodotin monotherapy in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) enrolled in DREAMM-2 and DREAMM-3. Blood. 2023;142(Supplement 1):6730. 10.1182/blood-2023-178026. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rathi C, Collins J, Struemper H, Opalinska J, Jewell RC, Ferron-Brady G. Population pharmacokinetics of belantamab mafodotin, a BCMA-targeting agent in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2021;10(8):851–63. 10.1002/psp4.12660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferron-Brady G, Rathi C, Collins J, Struemper H, Opalinska J, Visser S, et al. Exposure-response analyses for therapeutic dose selection of belantamab mafodotin in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;110(5):1282–92. 10.1002/cpt.2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Booth B, Rahman A, Kim G, Huang SM, Zineh I. Toward greater insights on pharmacokinetics and exposure-response relationships for therapeutic biologics in oncology drug development. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;101(5):582–4. 10.1002/cpt.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel H, Egorin MJ, Remick SC, Mulkerin D, Takimoto CHM, Doroshow JH, et al. Comparison of child-pugh (CP) criteria and NCI organ dysfunction working group (NCI-ODWG) criteria for hepatic dysfunction (HD): implications for chemotherapy dosing. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14_suppl):6051. 10.1200/jco.2004.22.90140.6051. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gay F, Larocca A, Wijermans P, Cavallo F, Rossi D, Schaafsma R, et al. Complete response correlates with long-term progression-free and overall survival in elderly myeloma treated with novel agents: analysis of 1175 patients. Blood. 2011;117(11):3025–31. 10.1182/blood-2010-09-307645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quach H, Dimopoulos M, Beksac M, Pour L, Delimpasi S, Vorobyev V, et al. Characterization and management of ocular events in patients treated with belantamab mafodotin plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone in the DREAMM-8 study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024;24:S273. 10.1016/S2152-2650(24)02315-2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farooq AV, Degli Esposti S, Popat R, Thulasi P, Lonial S, Nooka AK, et al. Corneal epithelial findings in patients with multiple myeloma treated with antibody-drug conjugate belantamab mafodotin in the pivotal, randomized, DREAMM-2 study. Ophthalmol Ther. 2020;9(4):889–911. 10.1007/s40123-020-00280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marquant K, Quinquenel A, Arndt C, Denoyer A. Corneal in vivo confocal microscopy to detect belantamab mafodotin-induced ocular toxicity early and adjust the dose accordingly: a case report. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):159. 10.1186/s13045-021-01172-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popat R, Warcel D, O’Nions J, Cowley A, Smith S, Tucker WR, et al. Characterization of response and corneal events with extended follow-up after belantamab mafodotin (GSK2857916) monotherapy for patients with relapsed multiple myeloma: a case series from the first-time-in-human clinical trial. Haematologica. 2020;105(5):e261–3. 10.3324/haematol.2019.235937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staudacher AH, Brown MP. Antibody drug conjugates and bystander killing: is antigen-dependent internalisation required? Br J Cancer. 2017;117(12):1736–42. 10.1038/bjc.2017.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai HI, Vugmeyster Y, Mangal N. Characterizing exposure-response relationship for therapeutic monoclonal antibodies in immuno-oncology and beyond: challenges, perspectives, and prospects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;108(6):1156–70. 10.1002/cpt.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiens MR, French JL, Rogers JA. Confounded exposure metrics. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2024;13(2):187–91. 10.1002/psp4.13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukhopadhyay P, Abdullah HA, Opalinska JB, Paka P, Richards E, Weisel K, et al. The clinical journey of belantamab mafodotin in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: lessons in drug development. Blood Cancer J. 2025;15(1):15. 10.1038/s41408-025-01212-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

GSK makes available anonymized individual participant data and associated documents from interventional clinical studies that evaluate medicines, upon approval of proposals submitted to https://www.gsk-studyregister.com/en/.