Summary

The rapid advancement of second-generation high-temperature superconductors, especially REBCO materials, underpins innovations in energy, medicine, and transport. Pulsed laser deposition (PLD) stands out as a premier method for producing high-quality REBCO thin films with controlled composition and microstructure—crucial for achieving high critical current density (Jc) and temperature (Tc). This review synthesizes recent progress in PLD-grown REBCO films, detailing how parameters such as laser energy, deposition temperature, background pressure, and substrate design influence superconducting performance. Special attention is given to nanoengineering, doping, and multilayer techniques that enhance flux pinning, as well as innovations in PLD setups—including multi-beam and high-rate processes—to enable industrial-scale production. The review also discusses the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for optimizing film properties and accelerating discovery. By comparing strategies and results from academia and industry, this work provides a comprehensive roadmap for advancing PLD-based REBCO superconductor technology.

Subject areas: Physics, Condensed matter physics, Superconductivity

Graphical abstract

Physics; Condensed matter physics; Superconductivity

Introduction

The pursuit of high-temperature superconductors (HTS) has long stood at the forefront of materials science, driven by their transformative potential across diverse technological sectors.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 Second-generation HTS (2G-HTS) represent a major leap forward, offering enhanced performance, greater efficiency, and compact design possibilities for critical applications ranging from energy transmission and medical imaging to cutting-edge scientific instrumentation.1,2,3,5,6,7

The field was revolutionized in 1986 by the seminal discovery of superconductivity in lanthanum-barium copper oxide by J. G. Bednorz and K. A. Müller,8 marking the first observation of superconductivity at a critical temperature (Tn > 30 K) well above that of conventional superconductors. This breakthrough challenged existing theoretical paradigms and spurred the discovery of an entire class of superconducting cuprate oxides. Remarkably, these materials exhibited critical temperatures exceeding 77 K—the boiling point of liquid nitrogen—rendering cryogenic cooling significantly more practical for real-world applications (Figure 1).3,6 Subsequent developments led to the emergence of high-performance superconducting systems such as YBa2Cu3O7-x (YBCO) and Bi-Sr-Ca-Cu-O (BSCCO), which further elevated critical temperatures and solidified the practicality of HTS technologies.9,10 These advancements have not only deepened our understanding of quantum materials but also enabled the translation of HTS from laboratory phenomena to robust components in modern industrial and technological systems.

Figure 1.

Timeline of several superconductor discoveries marked as before and after BCS theory

SCs: superconductors. A15 SCs: superconductors deriving from Cr3Si structure type. Chevrel phases: MMo6S8, where M = Pb and rare-earth (RE). RERh4B4: RE represents rare-earth elements. HFSCs: heavy fermion superconductors. LBCO: Ba-doped La2CuO4 (LBCO). YBCO: YBa2Cu3O7−δ. BSCCO: Bi2Sr2Can−1CunO2n+4 where n is positive integer. HBCCO: HgmBa2Can−1CunO2n+m+2, where m = 1 and n = 1–7. IBSCs: iron-based superconductors. Reprinted from6 with permission from American Chemical Society.

Among the diverse families of HTS, rare earth barium copper oxide (REBCO or RE-123, where RE (rare-earth) = Y, Sm, Gd, Eu, etc.) stands out due to its exceptional superconducting properties. These materials demonstrate the ability to operate at elevated temperatures and under high magnetic fields, making them the subject of intensive research and widespread technological interest.2,3,5 The advancement of REBCO-based superconductors has already significantly propelled the field forward, enabling practical applications in technologies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), power transmission cables, fault current limiters, and more.6,7,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 Notably, the work of MacManus-Driscoll and Wimbush has clearly delineated the application-specific use of superconducting properties and strategies for enhancing the critical current density (Ja).2

The unique advantages of REBCO materials—particularly their high critical current density—have positioned them as promising candidates for next-generation superconducting technologies. However, challenges remain, including intrinsic brittleness and a pronounced sensitivity to defects.5 As such, the optimization and development of REBCO superconductors continue to be active areas of research and industrial innovation.

A critical factor in realizing the full potential of REBCO lies in the synthesis approach, as fabrication methods directly impact microstructural quality and superconducting performance. Moreover, engineering applications demand scalable, high-quality, and cost-effective production techniques. Over the years, various synthesis methods have been developed to meet these needs. Among the most prominent are physical vapor deposition (PVD) techniques such as pulse lased deposition (PLD), sputtering, evaporation, cathodic arc deposition, and molecular beam epitaxy (MBE). Chemical vapor deposition (CVD), including its variants like plasma-enhanced CVD (PECVD) and metal-organic CVD (MOCVD), also plays a key role. Additionally, atomic layer deposition (ALD) is employed for its precise control over film thickness, while sol-gel processes have proven effective, particularly for the preparation of complex oxide superconductors.18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26

Superconductors synthesized via PLD represent a vital frontier in materials science, especially in the context of HTS. PLD involves a highly controlled process in which intense laser pulses ablate material from a solid target, resulting in the deposition of a thin film onto a substrate.27,28,29 This technique has garnered substantial attention due to its ability to fabricate high-quality thin films with exceptional precision in both composition and thickness.2,25,30

The inherent versatility of PLD makes it particularly well-suited for the growth of complex oxide superconductors—materials that are essential for next-generation electronic, energy, and magnetic technologies. Figure 2 illustrates the irreversibility lines of various superconductors, highlighting the superior performance characteristics achievable through advanced fabrication methods.31

Figure 2.

Variation of irreversibility field with temperature for different superconductors, including HTS, MgB2, metallic compounds, and alloys

Reproduced from31 with permission from Frontiers.

Recent research efforts are increasingly focused on scaling PLD for large-area applications, with particular emphasis on the production of REBCO-based coated conductors. A promising direction involves the integration of artificial pinning centers (APCs) within the superconducting matrix, which significantly enhances flux pinning and critical current performance. This approach is poised to enable superconducting applications over a broad temperature spectrum, spanning from 5 K to 77 K, thereby expanding the utility of HTS materials across a wide range of operational environments.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive exploration of the PLD technique, with a particular focus on its application in the fabrication of 2G-HTS, specifically REBCO compounds. The discussion will delve into the synthesis mechanisms, critical processing parameters that govern film quality, and the technological enhancements that have propelled PLD as a leading method for producing high-performance superconducting films. Special emphasis will be placed on the optimization strategies and structural modifications of PLD systems that enable precise control over film architecture and functionality. In-depth analyses of the specific atomic-level effects on superconducting properties, including detailed physical models, have already been reviewed elsewhere and therefore fall outside the scope of the present work.5,6,7,17,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37

The review will also address the industrial-scale production of REBCO films via PLD, underscoring the importance of scalability for their implementation in real-world superconducting devices and power applications. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning (ML) into the research and development pipeline will be examined. These emerging technologies hold great promise in accelerating the discovery, design, and optimization of superconducting materials by enabling predictive modeling and intelligent process control under varying experimental conditions. Through the examination of these key areas, this review seeks to illuminate the pivotal role of PLD in advancing HTS research and to highlight its transformative potential in enabling future breakthroughs in superconductivity.

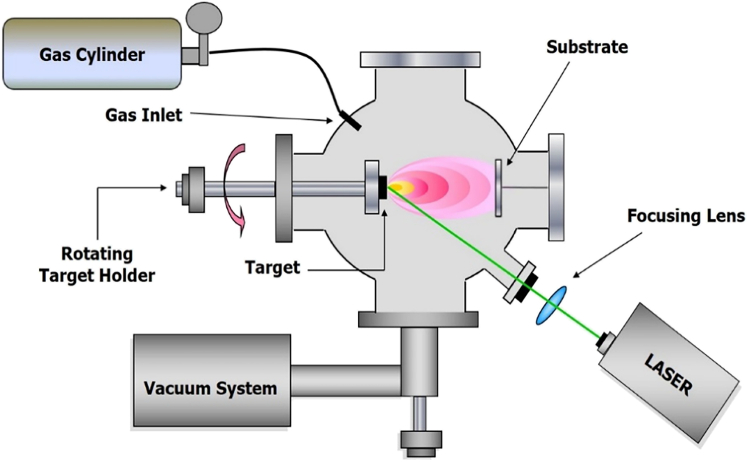

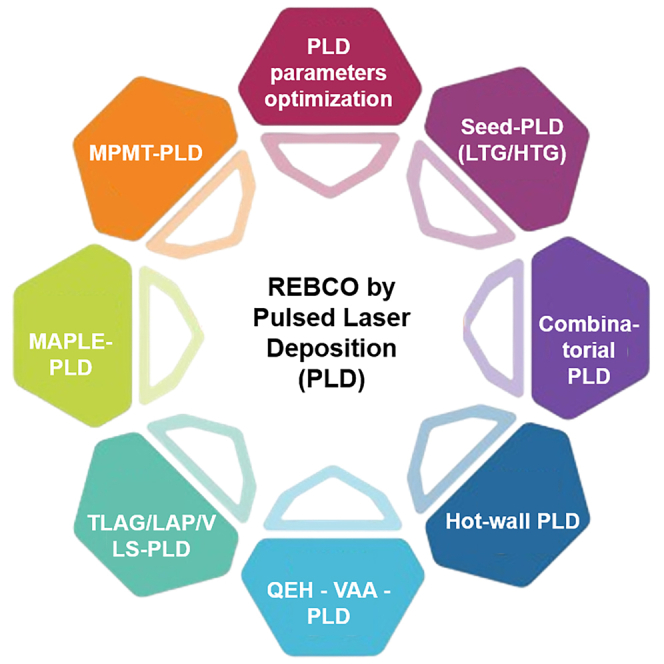

PLD method: Key principles, benefits, and challenges

One of the principal PVD techniques employed in the fabrication of HTS is PLD. This versatile method enables the precise deposition of superconducting thin films directly from bulk targets.29,38,39 PLD operates by using high-energy laser pulses to ablate material from a target, which is then deposited onto a substrate to form thin films (Figure 3).27,28,29 Due to its high deposition rates, excellent stoichiometric transfer, and precise control over film growth, PLD has become the predominant technique in the industrial-scale production of HTS.29,40 The process allows for excellent reproducibility and control over microstructure, offering the critical advantage of achieving high supersaturation conditions. This, in turn, promotes rapid nucleation and grain formation. Moreover, PLD is highly adaptable, capable of fabricating metastable phases and a broad spectrum of architectures—from simple thin films to more complex multilayered or nanostructured designs. It also facilitates the incorporation of various APCs, including zero-dimensional (0D) point defects and one-dimensional (1D) nanorods, which are essential for enhancing the critical current density across different operating regimes.2,31,38 As such, PLD is often regarded as the most straightforward method for defect engineering, with deposition parameters such as temperature and rate easily adjustable to reproducibly introduce a diverse array of pinning structures.31 Notably, REBCO conductors fabricated via PLD typically exhibit superior performance across a wide range of temperatures and magnetic fields when compared to those produced by alternative deposition techniques, making PLD highly favorable for industrial applications.2,30

Figure 3.

Typical PLD setup scheme

Reproduced from40 with the permission from MDPI.

However, PLD is not without limitations. Challenges such as the handling of materials with volatile components, maintaining uniform film thickness over large areas, and precise defect control remain significant concerns.29,41,42 Consequently, ongoing research is focused on addressing these issues to optimize the deposition process and develop next-generation HTS conductors with improved performance. Table 1 (2,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68) summarizes and compares PLD with some other main deposition techniques in terms of cost, scalability, and performance to contextualize PLD’s advantages and limitations.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of REBCO deposition techniques

| Technique | Cost | Scalability | Film Performance | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLD | Medium to High | Medium to High | High | Stoichiometric transfer, relative simplicity, versatility, reproducibility, and high film quality at reasonable rates. | Complex setup and modifications are required for scalability and throughput increase, and high equipment cost. |

| High capital and operating cost (vacuum + high-power laser). Recent multi-beam systems and other modifications improve throughput, but capital cost remains substantial. | Moderate to high industrial scale. Small-area deposition by default; can scale to long tapes with moving substrate, multi-beam setups, and other modifications. Throughput is moderate to high (standard rates ≈0.1–0.2 μm/min and higher), industrial rates could reach 0.3–0.6 μm/min and higher, still some challenges to increase further production rate (throughput and yield) of kilometer-length films. | Excellent epitaxial film quality (dense, highly crystalline). High Tc and Jc are achievable with good growth control. Performance can be enhanced via doping and the creation of nanoscale pinning defects that boost Jc. Films have high phase purity, smooth morphology, good conformality, and uniformity. | |||

| CVD/MOCVD | Medium to High | Medium to High | Medium to High | Good scalability and throughput, uniform, large-area coverage. | High precursor and process cost, complex chemistry control, and high-temperature requirements. |

| High-cost equipment (reactor, gas delivery) and precursors. Operating cost is high but can coat a large area, amortizing cost. High throughput reduces per-meter cost, making it economically attractive at scale. | Highly scalable for continuous processing. Reel-to-reel MOCVD proven for long tapes. Can coat both sides of a substrate and wide tapes with uniform thickness. Moderate to high deposition rates (0.1–0.2 μm/min or more) enable industrial throughput. | Good- to High-quality epitaxial films, competitive with PLD, though Jc is often lower due to less sharp grain boundaries. Slightly more secondary inclusions can appear if process control falters. Moderate growth control. Can incorporate pinning nanostructures (e.g., BaZrO3) for higher performance. | |||

| Sputtering | Medium | Medium | Medium | Relatively straightforward and reliable process, compatible with standard semiconductor fabrication infrastructure, which means established equipment and processes can be leveraged (useful for making multilayer devices with YBCO). | Stoichiometry control issues, which can be improved with several measures that often reduce the effective deposition rate or add complexity, are relatively more prone to defect formation, and achieving high Jc films requires significant process complexity (careful tuning of plasma conditions, very high substrate temperatures, additional annealing). |

| Vacuum-based but no expensive laser; uses magnetron guns (widely available). Targets (e.g., YBCO ceramic) are pricey and require periodic replacement. Overall, relatively affordable for labs and semi-industrial use, but the cost is not low due to relatively long deposition times. | Employed for short samples and buffers. Some reel-to-reel trials, but deposition rate is modest (typically ∼0.01–0.05 μm/min), so coating long lengths is time-consuming. Uniform and conformal coating of wide tapes is difficult (edge effects). No current mass production of REBCO by sputtering, only niche or experimental scaling (≪100 m). | Moderate quality with relatively lower Jc on average. Moderate growth control. Achieving uniform phase and oxygenation is challenging over long lengths. Pinning structures must be introduced by complex co-sputtering or post-processing; thus, in-field Jc improvement lags behind PLD/MOCVD. While epitaxial quality can be excellent locally, maintaining that over a long, moving substrate is tougher. | |||

| MBE | Very High | Low | High | Atomic-level control - thickness, interfaces, composition, high precision, in situ monitoring, and flexibility is possible with RHEED (reflection high-energy electron diffraction). | Extreme cost and low throughput, technical difficulties (source oxidation, narrow growth windows, and oxygen delivery challenges). |

| Very high cost due to Ultra High-Vacuum system, multiple effusion cells. Expensive to maintain and very slow throughput (high cost per film). Typically, only in specialized labs. | Poor scalability. Small substrate sizes (1–2 inches) and very slow growth (rates typically below ∼0.1 nm/min). Not practical for long lengths or volume production. Precision-oriented, not throughput-oriented. | Superb film crystallinity and interface control (atomic layer precision). Tc and Jc of films can equal or even exceed others in ideal cases (due to purity and perfect epitaxy). | |||

| ALD | High | Low | High | Precise thickness and composition control, unmatched uniformity and conformality even for 3D geometries. | Slow deposition rate and scale challenges, careful sequence control required for complex stoichiometry like REBCO, post-processing needs. |

| Equipment and precursors are expensive, and deposition is slow, increasing the cost per thickness. Still cheaper than MBE for comparable control. | Good scalability in area and surface complexity. Can uniformly coat large or complex 3D surfaces (conformal coverage unmatched by other methods). Throughput (rates typically below ∼nm/min) is low for thick films, but newer spatial ALD techniques can improve speed. | High atomic level control for conformality and thickness, but use for complex REBCO films is still in development. Film crystallinity can be improved by post-deposition annealing. Overall film quality is high (smooth, uniform, conformal). | |||

| Solution Deposition | Low | Medium | Low to Medium | Low-cost, non-vacuum process, good scalability potential, high material utilization, and easy composition tuning. | Multi-step processing complexity, films are more prone to defects, and lower density. |

| Very low-cost equipment (no vacuum; uses solution processing and furnaces). Precursors (metal salts) are relatively inexpensive. The process is simple and cheap per unit area, making it attractive for low-cost HTS wire. | Highly scalable in length – e.g., continuous dip-coating or slot-die coating on 100 m+ tapes. Limited by furnace size and time; batch processing of multiple tapes in one furnace helps throughput. Typically requires multiple passes for thick films. | Relatively poor growth control, conformality, and uniformity of films. Films may have more porosity or larger second-phase particles. Lower supersaturation growth leads to larger, less dense pinning defects, which can reduce Jc under high fields. Requires careful and extensive heat treatment to avoid misoriented grains. |

YBCO

Historically, PLD has been most prominently utilized in the fabrication of HTS thin films. The technique has been particularly effective in producing high-quality films of cuprate-based superconductors, notably the yttrium barium copper oxide (Y-Ba-Cu-O, or YBCO) family. These films exhibit superconducting onset temperatures around 95 K and reach zero electrical resistance at approximately 85 K when deposited on SrTiO3 (STO) substrates.28,41,69,70

YBCO remains a benchmark material in HTS research and applications due to its favorable properties, including high critical current densities in the range of 1–4 MA/cm2, relatively elevated critical temperatures, and robust flux pinning capabilities.31,71 These attributes make YBCO thin films fabricated via PLD particularly well-suited for various high-performance superconducting technologies.

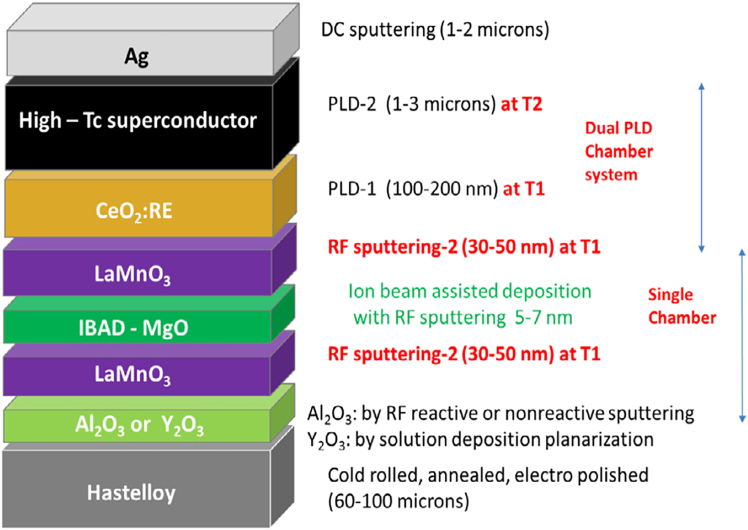

Figure 4 presents an example of a second-generation (2G) coated conductor architecture, composed of a multilayered stack engineered for high superconducting performance, mechanical robustness, and chemical compatibility.72 The base is a Hastelloy substrate, chosen for its mechanical strength, corrosion resistance, and flexibility. On top of it, usually an Al2O3 or Y2O3 planarization layer is applied to smooth the substrate surface and prevent diffusion of unwanted elements, like Ni or Cr. An IBAD-MgO layer imparts the necessary biaxial texture to the stack—essential for aligning the crystalline axes of the subsequent layers. A LaMnO3 buffer layer is deposited to promote epitaxial growth and act as a chemical barrier. Above the buffer stack, a CeO2 layer is typically deposited to minimize lattice mismatch, improve wetting, and nucleation for such superconducting layers as YBCO. Then, after the high-Tc superconducting layer, follows a silver (Ag) cap layer to protect the superconductor from environmental degradation and facilitate current transfer during operation. To summarize, the buffer layers serve as crucial intermediaries that transfer the biaxial texture from the substrate to the superconducting layer, ensuring a barrier from unwanted diffusion, epitaxial growth, and minimizing lattice mismatch, while the superconducting layer provides the high critical current and magnetic field performance essential for advanced superconducting applications.

Figure 4.

Example of the 2G HTS tape architecture

Reproduced from72 with the permission from IOP.

PLD has been extensively utilized to fabricate high-quality YBCO films, which are widely implemented in superconducting wires and coated conductors. The optimization of PLD parameters—such as laser fluence, substrate temperature, ambient oxygen pressure, and other growth conditions—has proven essential for tailoring the superconducting properties of these films.30,73 Notably, fine-tuning the deposition rate and energy density can significantly reduce processing time—by up to a factor of five—while maintaining film quality within acceptable limits, contributing to more cost-effective production methods.74

Atmospheric influence in PLD-grown YBCO films

Investigations into the PLD growth of YBCO films under different atmospheric conditions—including oxygen, nitrous oxide (N2O), and nitrogen—have demonstrated that YBCO phase formation at high temperatures can occur even in the absence of oxygen, with superconducting behavior preserved across all environments tested.75 This oxygen-independent synthesis is particularly advantageous for applications involving oxidation-sensitive substrates.

Further studies on PLD growth in mixed O2/Ar atmospheres revealed a strong influence of argon content on the surface morphology of YBCO films.76 An increased argon fraction led to reduced surface particle density and larger particle sizes, while the lattice parameters (1.168 nm) and critical temperature (Tc ≈ 90 K) remained consistent. These results were attributed to a uniform post-deposition annealing treatment in pure oxygen applied to all samples. Additionally, advanced heterostructures such as YBCO films enhanced with LaAlO3 (LAO) APCs have been successfully synthesized using a combination of PLD and magnetron sputtering at a 25:75 O2/Ar ratio. These composite films exhibited improved superconducting performance, notably higher critical current densities (Jc) under magnetic fields exceeding 1 T, highlighting the potential of this approach for high-field applications.76

Impact of deposition temperature on superconducting properties and microstructure

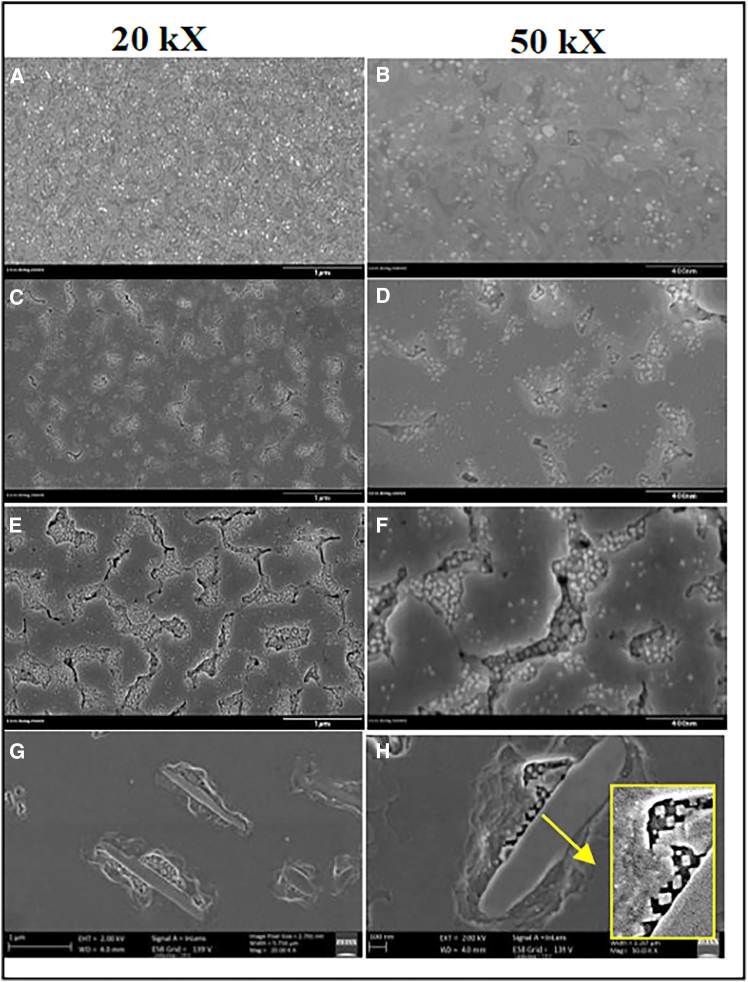

The performance of superconducting materials is significantly influenced by their deposition temperature, which plays a crucial role in determining their characteristics. For instance, Sebastian et al.77 investigated the critical current density and flux pinning landscape of BaHfO3 (BHO) and Y2O3-doped YBCO thin films across a temperature range of 790°C–825°C. Their findings indicated that the optimal growth temperature for achieving robust, isotropic pinning and the highest critical current density was 810°C. Initially, it was hypothesized that the temperature effect was due to increased ad-atom mobility and diffusion during the film growth process. However, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis did not support this interpretation. Moreover, varying the deposition temperature (810°C and 825°C) produced distinct effects depending on the specific doping combinations of BaZrO3 (BZO) and Y2O3. Notably, the YBCO thin film doped with 2 vol. % BZO and 3 vol. % Y2O3, deposited at the optimal temperature of 825°C, demonstrated the highest critical current density at both low (5 K) and high (65 K) temperatures across a broad magnetic field range (0–9 T).78 These results were attributed to the synergistic effects of the optimized doping levels and the favorable PLD deposition conditions, which facilitated the creation of a microstructure with an increased density of defects and pores, promoting more isotropic behavior. For example, SEM images on Figure 5 clearly show the distinguishing influence of the doping on the film morphology, where doped surfaces had significantly more defects, pores, and grains.

Figure 5.

SEM images of pristine and doped YBCO

(A and B) pristine YBCO, YBCO doped with (C–F) BZO+Y2O3 and (G and H) BZO at different deposition temperatures (A–D) 810°C and (E–H) 825°C.

In a related study, researchers explored the effects of varying CeO2 doping concentrations in YBCO thin films and identified an optimal deposition temperature for maximizing the critical current (Ic).79 This temperature was found to be dependent on the doping level: films doped with 1 and 2 mol.% CeO2 exhibited optimal performance at a higher deposition temperature (830°C), whereas those with 3 mol.% CeO2 achieved peak performance at a slightly lower temperature (820°C). For films with lower doping levels (1–2 mol.%), the improvement in Ic with increasing temperature was attributed to the suppression of large grain formation and a reduction in grain misorientation. In contrast, the lower optimal temperature for the 3 mol.% CeO2-doped films was ascribed to the substitution of Y atoms by Ce, which introduced lattice distortions.

To further elucidate the influence of deposition temperature on the microstructure and superconducting properties, researchers investigated the relationship between stacking fault (SF) density and critical current density (Jc).80 An increase in deposition temperature was found to correlate with a higher SF density, which in turn led to a significant enhancement in Jc under applied magnetic fields. TEM analyses in one of the aforementioned studies [45], confirmed a linear correlation between SF density and Jc, supporting the hypothesis that stacking faults act as effective flux pinning centers and thus contribute to the improved superconducting performance of YBCO films.

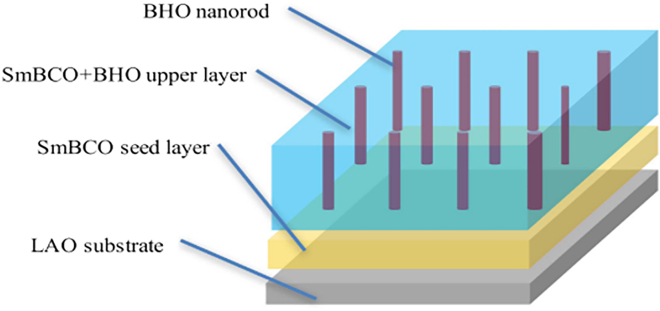

Several research groups have further focused on precise substrate temperature control during the PLD process. For instance, Liu et al. introduced a seed layer technique, wherein a thin layer of 5 mol.% BHO-doped YGBCO was initially deposited at substrate temperatures ranging from 710°C to 820°C, followed by a thicker top layer deposited at 820°C.81 The optimal substrate temperature for the seed layer was identified as 790°C, at which the resulting YGBCO+BHO films exhibited a maximum Jc of 4.0 MA/cm2 at 77 K in self-field conditions. The crystallinity and texture of the films improved with increasing seed layer temperature up to 790°C, beyond which film quality and superconducting properties began to deteriorate. This emphasizes the critical importance of precise temperature control during the seed layer deposition.

Further insights into the impact of substrate temperature variation were provided by Sato et al.,82 who addressed the formation of undesired a-axis grains during the deposition of thick films—a phenomenon exacerbated by reduced substrate surface temperatures, which leads to a decline in critical current. By employing a self-heating method, wherein the metal substrate is heated via Joule heating (Figure 6), rapid thermal adjustments could be made during deposition. This approach effectively suppressed the formation of a-axis oriented grains, even in thicker films, thereby preserving high Jc values. The ability to dynamically control substrate temperature during growth proved essential for optimizing the structural and superconducting properties of the films.

Figure 6.

Schematic drawings of substrate heating

(A) Cold-wall technique: the substrate is heated.

(B) Self-heating technique: the substrate is heated by Joule heat generated by the resistance of the substrate.

Influence of target density, composition, and geometry

The condition of the PLD target plays a critical role in the development of new materials and their modifications, and must always be taken into careful consideration. For example, during the investigation of the influence of target density on the deposition of Y0.5Gd0.5Ba2Cu3O7−δ (commonly denoted as YGBCO, representing YxGd1-xBa2Cu3O7−δ), it was observed that the superconducting film properties were significantly affected by the density of the ceramic target.83 A target with lower density (4 g/cm3) produced a greater number of lower-energy ablated species, resulting in the formation of a more uniform and compact film morphology. In contrast, a higher-density target (5.5 g/cm3) emitted fewer ablated species, promoting less uniform nucleation and leading to a more porous film structure. Consequently, the film deposited using the lower-density target exhibited superior superconducting characteristics, with a critical temperature of 91.3 K and a critical current density of 5.4 MA per square centimeter at 77 K. In a similar study involving YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO),84 nanostructured targets with varying grain sizes (25–45 nm) and densities were synthesized via a sol-gel route. It was found that increasing the target density led to a reduction in surface roughness of the deposited films, although a minor decrease in critical current density was also recorded. Overall, the influence of target density on the superconducting performance of YBCO was determined to be marginal.

In fact, the exact impact of target density has not been extensively researched yet to come up to specific conclusions; nevertheless, the available studies at the moment indicate that this impact could also vary based on the material target. For example, in more recent research, a group of researchers demonstrated that the microstructure of PLD targets—specifically the combination of grain size, packing density, and 4 wt % BaZrO3 (BZO) content—dictated the plume chemistry, defect topology, and hence the vortex-pinning anisotropy of REBCO films.85 Densely compacted nanocrystalline YBCO (nm-grains, 75%–86% relative density) ejects multi-atom clusters that seed many small growth islands, forming a tight grid of threading dislocations and long stacking faults; in this matrix, BZO self-organizes into vertically continuous nanorods, delivering a strong c-axis critical current peak sustained to 8 T (Figure 7). By contrast, coarser, less-dense microcrystalline targets (μm-grains, 76%–80% density) ablate mainly atomic species, yield sparse defects, and break the same BZO load into shorter, more splayed rods that flatten the critical current profile and favor low-field, angle-independent performance (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

TEM images of undoped and BZO-doped YBCO

(A–D) YBCO with different target grain sizes, showing stacking faults and BZO nanostructures; (E) schematic of the target grain size effect on film growth.

A subsequent study by the same group extended this “target-engineering” concept to industrial IBAD-MgO templates and showed that merely shrinking the YBCO-BZO target grains to the nanometer scale—without altering BZO loading or laser settings—suppressed the substrate-film grain-boundary transfer altogether.86 Moreover, it accelerated growth by 25% by ejecting multi-atom clusters instead of single ions, and thus delivering more material to the substrate per pulse. It also drove the self-assembly of 7–8 nm-diameter BZO nanorods that were three times longer and twice as splayed as those obtained from conventional microcrystalline targets. The resulting films exhibited a 40% boost in c-axis critical current at 77 K and maintained over an order-of-magnitude advantage above 2 T, while leaving ab-plane transport unchanged, confirming that vertically coherent nanorods—not grain boundaries—now dominate the pinning landscape. A simple kinetics model linked this behavior to cluster-rich plumes: once emitted particle radii exceeded ∼12 nm, the lateral force exerted by substrate grain boundaries became negligible, allowing defect-free overgrowth and a denser dislocation-fault grid that further guided rod alignment. Collectively, these findings reinforce that target grain refinement, alongside compaction and BZO dosing, could be a decisive lever for scaling high-field REBCO coated conductors.

Further investigation into the effects of target composition and its transfer to the film was carried out by the research group led by Mozhaev et al.87 Their study focused on minimizing compositional deviations between the PLD target and the resulting film. This was achieved by implementing laser beam scanning across the target surface and substituting oxygen with argon in the deposition environment. The laser scanning technique allowed for a more uniform distribution of the ablation plume and mitigated spatial variations in laser spot energy density. These adjustments reduced both angular and inelastic scattering of the ablated species, leading to the formation of dense YBCO films with highly stable superconducting properties. Additionally, the targets were subjected to periodic resurfacing and repolishing to ensure consistent material transfer and compositional fidelity between the target and the deposited film. The study also revealed that an increased concentration of yttrium in the target resulted in the formation of porous, rough-surfaced films, whereas the formation of a quasi-liquid layer based on barium-copper oxides during deposition facilitated improved growth of high-density YBCO films. Techniques involving similar transient liquid-phase mechanisms, such as transient liquid-assisted growth (TLAG), will be discussed in more detail later.

In another investigation involving barium zirconate (BZO)-doped YBCO films,88 both single-target systems (with the general composition 1231-xBZOx) and multilayer targets (denoted as (BZOn/123m)N) were studied to assess their influence on superconducting properties. For multilayer deposition, the PLD system was modified to include automated target rotation and pulse sequencing, with precisely defined deposition rates for each layer. The multilayer films demonstrated minimal degradation in critical temperature and self-field critical current density, even at high BZO doping levels (up to 10%). In contrast, films grown from single-target systems showed a linear decline in these properties as BZO concentration increased. The superior performance of the multilayer films at elevated BZO concentrations was attributed to reduced zirconium diffusion and minimal chemical incompatibility effects, underscoring the effectiveness of the multilayer strategy in preserving and enhancing superconducting performance.

Furthermore, the significance of the geometric configuration between the target and substrate was examined by Backen et al.,89 who reported that an off-axis PLD setup—where the target and substrate are positioned perpendicularly—can achieve comparable reproducibility and uniformity in film deposition. This configuration is particularly important for ensuring consistent superconducting properties across large-area films. Additionally, a quasi-multilayer deposition approach involving alternating layers of YBCO and metallic inclusions (such as hafnium) was shown to enhance flux pinning efficiency, further contributing to the improvement of superconducting characteristics.

Optimizing multiple PLD parameters

In the majority of studies, a more comprehensive strategy has been adopted, involving the simultaneous evaluation of multiple PLD parameters. For instance, Xiong and colleagues systematically optimized deposition conditions by enhancing target quality and modifying the oxygen ambient pressure to improve the film’s performance in microwave applications.90 Specifically, the use of a high-density target contributed to superior surface morphology, while increasing the oxygen pressure and laser pulse energy proved essential for reducing microwave surface resistance and enhancing the critical current density. These modifications facilitated microstructural improvements under elevated energy and pressure conditions, which were pivotal for achieving the desired microwave properties. Although the study did not delve into an in-depth structural analysis, this optimized approach enabled the successful deposition of large-area, double-sided, and uniform films. Notably, microwave filters fabricated using these improved films were directly compared with those made from commercial counterparts, and the results affirmed that the produced films fully satisfied the stringent performance requirements of planar microwave devices, underscoring their potential for practical implementation.

In another study, Xu et al.91 thoroughly examined the effects of various deposition parameters, such as substrate inclination angle and film thickness, on the crystallinity of the deposited films. The results indicated that a film thickness of 500 nm combined with a 15° substrate tilt yielded optimal crystallinity, characterized by a dense microstructure and minimal porosity. While the study did not extend to a full superconducting performance evaluation, the improved morphology is expected to correlate with enhanced superconducting properties, warranting further exploration. Favre and co-authors conducted a detailed study focused on substrate temperature, deposition time, and target-substrate distance, aiming to modulate the residual strain within the films.92 Their results demonstrated a nearly linear suppression of the critical temperature with increasing c-axis lattice expansion, attributed to in-plane compressive strain. This phenomenon was explained through a theoretical model involving quantum phase fluctuations and reduced Coulomb screening along the c-axis. According to the model, elongation of the c-axis weakened electrostatic coupling between adjacent CuO2 planes, thereby decreasing the critical temperature. The optimal deposition conditions that minimized residual strain and maximized the critical temperature (89 K) were identified as a substrate temperature of 690°C, a deposition duration of 30 min, and a target-substrate separation of 2 cm.

Further investigations into the influence of deposition temperature and growth rate on the formation of columnar and nanoparticle defects revealed that the optimal temperature range for achieving an effective defect landscape in doped films was between 785°C and 800°C.93 This temperature window supported a balanced distribution of columnar defects aligned along the c-axis and randomly oriented nanoparticles, both essential for strong and isotropic flux pinning. Temperatures below this range favored the formation of isolated nanoparticles, while higher temperatures led to predominantly columnar structures, each less effective for comprehensive pinning. Additionally, a laser repetition rate of 2 Hz was found to be optimal, as it provided sufficient temporal spacing between pulses, allowing dopant species increased surface mobility and facilitating the growth of well-aligned, extended columnar defects. This combination of deposition parameters led to significantly enhanced critical current densities, reaching up to 3 MA/cm2 at 77 K in self-field, by simultaneously promoting strong vortex pinning and minimizing flux creep. As a result, films exhibited high in-field critical currents with nearly isotropic angular dependence, making them suitable for demanding superconducting applications.

Elemental doping and nanoengineering strategies for enhancing flux pinning

Initial efforts to enhance the performance of cuprate films often centered on conventional elemental doping strategies aimed at improving processing outcomes and flux pinning capabilities. One early study investigated varying concentrations of terbium and cerium dopants.94 It was observed that terbium incorporation preserved a high critical temperature while enhancing the critical current density, with Y0.99Tb0.01 compositions demonstrating superior performance across a broader range of magnetic field and temperature conditions. In contrast, cerium doping resulted in a marked suppression of both critical temperature and current density as its concentration increased, suggesting a deleterious impact on superconducting behavior. These findings underscored that while small amounts of terbium can positively influence flux pinning, cerium exhibits limited utility due to its adverse effect on superconductive properties.

Contemporary research has shifted toward advanced nanoengineering approaches, particularly through the introduction of APCs within the film matrix to significantly boost current-carrying capacity—an essential criterion for technological applications.1,43,95 Various studies have examined the incorporation and optimization of such pinning centers in films fabricated via PLD. For example, Kuroki et al. emphasized the importance of microscale heterogeneities arising from Ba2YbNbO6-based doping, highlighting their critical role in the development of high-performance coated superconductors.96 In parallel, Chen and colleagues explored the comparative effects of nanorod- and nanoparticle-based APCs, specifically BZO nanorods and Y2O3 nanoparticles.97 Their findings, in agreement with earlier work by Maiorov and others,93,97 revealed that the inclusion of Y2O3 nanoparticles led to an increased volume fraction of isotropically distributed BZO pinning centers. This significantly enhanced pinning force density and contributed to an elevated critical temperature relative to films doped exclusively with nanorods.

Additional investigations introduced alternating nanostructures of BZO and Y2O3 into multilayered films, fabricated via PLD.98 These engineered heterostructures yielded a marked improvement in flux pinning performance, achieving a critical current density 1.5 times higher than that of undoped reference films (2.66 MA/cm2, self-field). Furthermore, these enhancements persisted under increasing magnetic fields, with a less pronounced decline in performance. Sueyoshi et al. conducted a comparative study on films doped with either BZO or BaSnO3 nanorods, focusing on their influence under varying magnetic field strengths.99 The results demonstrated that films doped with 1.5 wt % BZO nanorods exhibited the highest critical current density and most effective flux pinning, outperforming BaSnO3-doped counterparts due to superior nanorod characteristics and pinning efficacy.

Comprehensive reviews by Jha and Matsumoto further catalog recent advancements in APCs integration across a range of rare-earth cuprate superconductors31 These studies collectively highlight the significant progress achieved through precision nanoengineering in elevating the current density and overall performance of superconducting films.

Optimizing substrate, buffer layer, and interface engineering

Numerous studies have focused on optimizing substrates, buffer layers, and their interfaces with superconducting films to enhance the performance of HTS. A recent investigation demonstrated that YBCO films synthesized via PLD on MgO substrates could retain superconducting properties at thicknesses as low as 3 nm, thereby extending the frontier of superconductivity in ultrathin materials.100 In addition to ultrathin film fabrication, the study also reported the successful realization of YBCO nanowires through a combination of PLD growth and subsequent lithographic patterning and etching processes.101,102 These nanoscale structures are of particular relevance for the development of superconducting nanoelectronics. Notably, the observation of a voltage switching effect in 10-nm-thick nanowires without Au capping was a critical finding.100 The bistability, attributed to localized normal-state domains, indicates a promising mechanism for controlling superconducting states in applications such as single-photon detectors.

Trabaldo et al. further elaborated on the use of YBCO nanowires in superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs) and magnetometers, emphasizing their potential in quantum sensing applications.103 In a related study, the structural and electrical transport characteristics of 50 nm-thick PLD-grown YBCO films with various doping levels were investigated.104 It was shown that films with lower doping levels were predominantly untwinned—exhibiting a reduced density of twin boundaries, which are known to influence superconducting behavior. Interestingly, these untwinned films experienced a similar strain state to slightly overdoped counterparts. The study also examined the effect of strain on superconducting properties and established the doping dependence of the upper critical field. These findings underscore the capability of PLD to produce nm-scale films with tunable strain, enabling detailed studies of strain-induced effects on superconductivity.

In contrast, Zhou et al. addressed performance optimization in thicker YBCO films.105 Their work revisited earlier studies involving BZO and Y2O3-doped YBCO,93 investigating the dependence of Jc on film thickness. The incorporation of APCs, specifically BZO and Y2O3, was found to mitigate the typical decline in Jc observed with increasing thickness. Impressively, the films maintained a high Jc of 2.3 MA/cm2 even at a thickness of 6.4 μm. This improvement was attributed to the effective pinning landscape introduced by the dopants, which preserved the film microstructure and enhanced overall superconducting performance across a broad thickness range.

The study by Stepantsov et al. demonstrated the successful PLD of YBCO films on SrTiO3 substrates, where the CuO2 planes were tilted relative to the surface by angles ranging from 0° (parallel orientation) to 70°.106 This tilt was introduced by rotating the crystalline lattice of the STO substrate around its [100] axis, which lies parallel to the film surface. The results showed that up to a tilt angle of 41°, the YBCO films maintained a high-quality single-crystal structure. However, beyond this critical angle, the films developed a two-domain texture accompanied by a significant increase in surface roughness. Such structural transformations are important to consider, as they can adversely affect superconducting performance, particularly in device applications where crystallographic uniformity is essential.

In related work, the importance of interface coherency between YBCO films and substrates or embedded pinning centers has been emphasized.107,108 One study successfully addressed the large lattice mismatch between YBCO films and BaZrO3 (BZO) nanorods—strong one-dimensional APCs (1D-APCs)—by introducing Ca/Cu substitution in the single CuO2 planes. This approach effectively expanded the YBCO c-axis at the interface, improving structural compatibility. As a result, the films exhibited a 5-fold increase in critical current density (Jc), highlighting the crucial role of interface engineering in enhancing superconducting performance.

Another notable study reported the PLD growth of YBCO films with b-axis orientation on the surface of (100)-oriented SrLaGaO4 crystals, using a 60 nm PrBa2Cu3O7−x buffer layer109 These films transitioned into a superconducting state at a temperature of 89 K. X-ray diffraction analysis confirmed the single-crystalline nature of the b-oriented films and the absence of domains with alternative crystallographic orientations. The lack of structural twins and the high uniformity of the film underscore its potential for device applications where directional anisotropy and structural precision are critical.

Furthermore, the orientation and surface morphology of yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) buffer layers were found to be highly sensitive to PLD deposition parameters, particularly oxygen pressure and laser repetition rate.110 These parameters significantly influenced the growth conditions and, consequently, the quality of the overlying YBCO superconducting films. The study identified optimal deposition conditions—an oxygen pressure of 1 mTorr and a low laser repetition rate of 80 Hz—that yielded the smoothest and most defect-free YSZ surfaces. Under these conditions, the YBCO films grown atop the YSZ buffer layers exhibited enhanced superconducting properties, achieving a Jc exceeding 4 MA/cm2 at 77 K.

Influence of substrate and layer thickness on YBCO film performance in PLD

Substrate thickness has been identified as a critical parameter influencing both the PLD process and the performance of YBCO superconducting tapes.111 It was shown that decreasing the substrate thickness can lead to a significant increase in critical current density (Jc), which is highly desirable for high-performance applications. However, this improvement requires careful optimization of the fabrication process, particularly the combination of alternating beam-assisted deposition and PLD. Among the tested samples, the tape with the thinnest substrate (50 μm) exhibited the best performance, achieving a Jc of 0.1 MA/cm2 under an ultra-high magnetic field of 18 T at 4.2 K. Furthermore, the authors proposed additional strategies to enhance current density, including independent regulation of the nucleation temperature through the initiation of lateral flows affecting PLD nucleation, and mitigation of rapid temperature fluctuations caused by ion bombardment from the laser plume.

To further address the limitations posed by thickness effects in YBCO films, one study demonstrated the effectiveness of a superconductor/interlayer/superconductor tri-layer structure.112 By introducing indium into a CeO2 interlayer, the critical current density (Jc) nearly doubled compared to a single-layer YGBCO film. The optimal interlayer thickness was found to be 40 nm, indicating that such interlayers can play a key role in facilitating current transport and reducing the detrimental effects of increased film thickness.

Similarly, the thickness of buffer layers was also found to be a determining factor in the structural and superconducting quality of YBCO films.113 An optimal thickness of 221 nm for the CeO2 buffer layer provided the best in-plane and out-of-plane texture, along with an exceptionally smooth surface exhibiting a root-mean-square (RMS) roughness of just 0.6 nm. YBCO films deposited on such optimized buffer layers achieved a high Jc of 4.6 MA/cm2 at 77 K in self-field conditions.

Porokhov et al. explored the use of a novel substrate—single crystalline quartz—for YBCO growth, motivated by the potential of amorphous substrates to reduce alternating current losses in superconducting tapes.114 Despite the significant lattice mismatch of approximately 22%, YBCO films grown via PLD exhibited moderate superconductivity with a critical temperature of 85 K and a Jc of 0.01 MA/cm2 at 65 K. The relatively low critical current was attributed to internal film stress, which was not visually evident in scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) analyses.

In another study, various substrates and deposition conditions were evaluated to optimize YBCO films for microwave device applications.115 A key finding was the importance of thermal contact between the substrate and the sample holder during deposition. A comparison of attachment methods—silver paste versus mechanical mask—revealed that silver paste at an optimized deposition temperature of 750°C resulted in the highest Tc (90.5 K) for YBCO films on STO substrates. Several substrate materials were tested, including STO, MgO, (LaAlO3)0.3(Sr2AlTaO6)0.7 (LSAT), SrLaAlO4 (SLAO), and NdGaO3 (NGO), with a focus on minimizing substrate-induced microwave losses while maintaining high superconducting performance. Among these, MgO was selected for further microwave characterization due to its low dielectric loss, acceptable critical temperature (86.5 K), and superior current density in samples prepared using a mechanical mask, making it highly suitable for microwave applications.

Advancements and modifications in PLD techniques

In addition to optimizing standard PLD parameters, more substantial modifications to the PLD setup have been introduced to further enhance the superconducting properties of YBCO films. For instance, Ichino et al. explored the use of a combinatorial PLD technique, optimizing key parameters such as oxygen pressure and target-to-substrate distance.116 Unlike the conventional KrF laser, this approach employed a Nd:Y3Al5O12 (Nd:YAG) laser, which is considered more environmentally friendly due to the absence of hazardous gases and offers cost advantages. The combinatorial method involved a patterned plate with a rectangular aperture that moved over the substrate in synchronization with both laser pulses and target switching. This configuration enabled the deposition of layers with a linear thickness gradient—from zero to several monolayers—of pure and doped YBCO. These layers were subsequently fused through solid-phase diffusion at elevated growth temperatures. This technique allowed for the fabrication of BSO-doped (3.6 wt %) YBCO films exhibiting excellent superconducting properties, including a critical temperature of 90 K and a critical current density of 2.5 MA/cm2 at 77 K in self-field—values comparable to those achieved using conventional PLD. Additionally, it was found that optimizing oxygen pressure and the target-to-substrate distance could improve material yield by up to 19.0%; however, the highest yield did not correspond to the highest critical current density.

Similarly, De Silva et al. applied Nd:YAG-PLD to synthesize (Y1-xHox)Ba2Cu3O7-z films, exploring the partial substitution of Y with Ho to introduce effective pinning centers without distorting the lattice, owing to the similar ionic radii of Ho3+ and Y3+.117 The study examined multiple compositions, optimizing parameters such as oxygen pressure, substrate temperature, target-substrate distance, energy density, and deposition time for each. The composition with x = 0.3 exhibited the best superconducting performance, achieving a Tc of 87 K and a Jc of up to 1.45 MA/cm2. The results confirmed the potential of Nd:YAG-based PLD for producing high-quality YBCO films in a cost-effective manner.

Building on these earlier Nd:YAG-based combinatorial studies, Chaluvadi et al. have recently demonstrated that the first-harmonic (1064 nm) Nd:YAG laser alone can reproducibly deposit high-quality, c-axis-oriented YBCO and related oxide heterostructures without recourse to UV harmonics or excimer sources.118 By operating at a larger target-to-substrate distance (≈8–10 cm) and masking the beam to moderate fluence, the authors achieved smooth, droplet-free epitaxial YBCO films on LaAlO3 that reached Tc (onset) = 93 K after oxygenation and retained coherent superconductivity (zero resistance at 80 K) even in tri-layer YBCO/CeO2/LaNiO3 stacks. Electron microscopy also confirmed atomically sharp interfaces and stoichiometric transfer. Thus, the compact, gas-free Nd:YAG platform offered a cost-effective, environmentally benign alternative for PLD of REBCO tapes and oxide electronics while preserving superconducting performance.

Further advancements to PLD have included the development of variable azimuth ablation (VAA) and quasi-equilibrium heating (QEH) techniques, which improved deposition efficiency, stability, and rate.119,120 VAA involved periodically altering the azimuthal angle between the laser beam and the target, thereby reducing surface roughening and enhancing deposition stability. A smoother target surface minimizes energy dissipation and maintains a higher deposition rate (Figure 8, top). Meanwhile, the QEH method maintained a nearly constant substrate temperature—with variations kept below 2°C—by using a tubular heater, a rotating IR-reflective screen (chopper), and a semi-enclosed chamber to reduce IR losses (Figure 8, bottom). This setup ensured consistent heating conditions, independent of the thermal contact between the substrate tape and the rotating drum. As a result, film microstructure and superconducting properties were significantly improved. The combined implementation of these enhancements in the high rate-PLD approach, along with optimized deposition conditions, led to YBCO films with high critical current densities: 2–3 MA/cm2 for 1 μm-thick films and over 1.4 MA/cm2 for 3 μm-thick films.119,120 This method presents a promising route for the cost-effective production of long-length, high-performance superconducting tapes.

Figure 8.

Schematics of target surface morphology and ablation

(I) initial roughness and relief after laser ablation at different azimuth angles (a–d); (II) variable azimuth ablation modes: spiral (a) and meander (b); (III) high-rate PLD installation.

Later in 2015, Abraimov et al. also implemented the QEH approach in their study on enhancing the superconducting properties of REBCO tapes.121 Their work introduced a double-disorder strategy that combined both intrinsic and extrinsic defect engineering to improve flux pinning. Intrinsic disorder referred to local stoichiometric variations within the REBCO matrix, resulting in nanoscale defects that function as APCs. These could be induced by modulating the oxygen pressure during the PLD process, which alters the angular distribution of atoms in the plasma plume. This variation leads to localized non-stoichiometric regions in the HTS layer without affecting the overall film composition. In parallel, extrinsic disorder was introduced via the incorporation of secondary phase nanoparticles such as BHO or BZO into the superconductor matrix. In addition to QEH, the authors optimized other PLD parameters. One such modification was akin to VAA, involving ablation from various spots on the target to maintain high deposition rates. They also optimized oxygen pressure—not only to promote intrinsic defects but also to enhance oxidation at the interfacial atomic layers, which plays a crucial role in film quality. The combined effect of these improvements resulted in a significant enhancement of the critical current density, particularly under high magnetic fields. The 4 mm-wide YBCO tapes demonstrated excellent performance, with reported critical currents reaching 309 A at 31 T and 1200 A at 5 T (4.2 K).

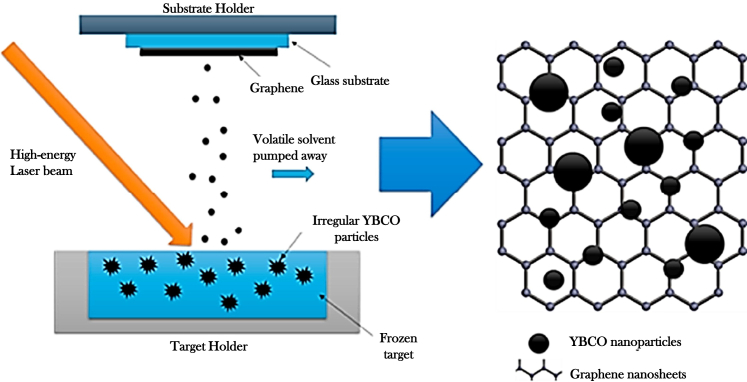

Recent developments in PLD-based fabrication of cuprate superconductors also include the introduction of TLAG, a novel technique based on the temporary formation of a liquid phase to enable high-quality film growth.122 TLAG enables extremely rapid film growth rates—up to 1000 nm/s—while maintaining excellent superconducting properties.123,124 In this method, amorphous precursor films (e.g., BaCuO2, CuO, and Y2O3) are first deposited via PLD. These films are then heated above 800°C to induce a eutectic reaction, forming a transient Ba–Cu–O liquid phase with dispersed Y2O3 nanoparticles. A sudden increase in oxygen pressure subsequently initiates crystallization, forming the YBCO phase (Figure 9). Key process parameters—such as heating ramps, maximum temperature, and oxygen partial pressure—were carefully tuned to achieve YBCO films with critical temperatures up to 90 K. One notable advantage of TLAG-PLD is the prevention of BaCO3 formation, which is detrimental to YBCO crystallization. TLAG has demonstrated the potential for high-throughput synthesis of high-quality superconducting films with fewer secondary phases and reduced low-angle grain boundaries, both of which are essential for maximizing the critical current density.122

Figure 9.

TLAG process

(A) Schematic drawing of the process, and (B) T–PO2 phase diagram for YBCO TLAG growth.

Another liquid-assisted processing (LAP) technique has recently been developed in conjunction with PLD, offering not only significantly faster growth rates—reaching up to 250 nm/min, comparable to TLAG—but also enhanced artificial flux pinning.125 This LAP approach utilized a non-stoichiometric target composition, which resulted in the formation of a minor liquid phase during deposition. The presence of this transient liquid phase facilitated enhanced diffusion of the deposited material within the growing film. Despite the high deposition rate, LAP-PLD successfully enabled the formation of mixed pinning landscapes, including both point-like and nanocolumnar defects. YBCO films synthesized with this method demonstrated critical current densities at 30–70 K comparable to those produced by conventional PLD. Remarkably, at lower temperatures, the performance was even superior—showing 5–10 times higher current densities. These advantages make LAP-PLD an appealing technique due to its potential for time and cost efficiency and relatively straightforward implementation.

A further PLD-based method incorporating liquid-phase dynamics is the vapor-liquid-solid (VLS) approach, which borrows aspects from liquid phase epitaxy (LPE).126 The VLS method involves three distinct stages, each defined by specific partial oxygen pressures, substrate temperatures, and laser frequencies (summarized in Table 2). Initially, a solid 200 nm YBCO layer is grown using a pure YBCO target. In the second step, a 50 nm Ba3Cu7O10 (BCO) liquid layer is formed on top by PLD using a 10 wt % Ag2O-doped BCO target. Finally, a third deposition stage is carried out using a 3 vol % BHO-doped YBCO sintered target, allowing growth through the liquid interface. All steps were performed continuously under vacuum, without interrupting the thermal cycle. This method enabled high-rate growth of BHO-doped YBCO films without sacrificing crystallinity. The improved performance was attributed to the three-dimensional molecular diffusion enabled by the transient liquid layer, which resulted in lower supersaturation at the growth front compared to conventional PLD. Moreover, APC-induced enhancements in superconducting properties were more pronounced in films fabricated using the VLS technique than in those grown by standard PLD.

Table 2.

Summary on YBCO performance and PLD techniques and parameters used for deposition

| Superconductor | Method | Conditions | Critical Temperature | Critical Current Density | Substrate | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | Heater temperature: 760°C; Oxygen pressure: 0.7 mbar; Energy density 2 J/cm2 |

Thin films: 3 nm–15 K 5 nm–70 K 10 nm–78 K 20 nm–82 K 50 nm–85 K Nanowires: 10 nm–70 K 20 nm–75 K 30 nm–81 K |

Nanowires 10, 20, 30 nm–50 MA/cm2 (4.2 K) | MgO | Arpaia et al.100 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | UV KrF excimer laser; Frequency: 10 Hz Wavelength: λ = 248 nm; Substrate temperature: 600−750°С; Oxygen pressure: Р = 0.4 mbar; After deposition, the chamber was filled with pure oxygen to Р = 600 mbar, the substrate with the film was annealed at 550°C for 1 h. |

89 K | NA | (100) SrLaGaO4 with 60 nm buffer layer of PrBa2Cu3O7−x | Stepantsov et al.109 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | UV KrF excimer laser; Frequency: 10 Hz Wavelength: λ = 248 nm; Substrate temperature: 780°С; Oxygen pressure: Р = 0.7 mbar; |

NA | NA | SrTiO3 (STO) | Stepantsov et al.106 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | Oxygen pressure: 0.6 mbar; After deposition, samples were annealed at 800 mbar oxygen atmosphere for 60 min at 550°C. |

∼85 K | 104 A/cm2 at 65 K | Buffer layers of 100 nm YSZ and 60 nm CeO2 on [001] SiO2 single crystal substrates | Porokhov et al.114 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | Laser adjusted for ∼103 pulses/cm2, 0.05 J/cm2 per pulse; Followed by oxygen post-loading performed at about 500°C121 |

NA | 0.1 MA/cm2 (18 T, 4.2 K) | YSZ) buffer layer (2–3 μm); CrNi stainless steel (50 μm) | Usoskin et al.111 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | Heater temperature: 760°C; Oxygen pressure: 0.7 mbar; Energy density: 1.5 J/cm2127,128 |

Overdoped (p = 0.17), a-axis: 14 T = 72 K 10 T = 75 K 6 T = 77 K 3 T = 82 K 1 T = 83 K 0 T = 85 K Underdoped (p = 0.12), a-axis: 14 T = 10 K 10 T = 20 K 6 T = 30 K 1 T = 47 K 0 T = 55 K |

NA | (110) MgO | Wahlberg et al.104 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | Pulse laser energy: 250 mJ; Laser frequency: 2 Hz; Target-substrate distance: 4.5 cm; The deposition temperature: 780°C; The deposition atmosphere has either oxygen, nitrous oxide or nitrogen; The deposition pressure: 20, 30, 40, 50 Pa; The laser sputtering time: 90 min; Some samples were cooled to the oxygen-annealing temperature and brought to vacuum below 10−4 Pa again, and then injected with oxygen (flowing atmosphere). |

Oxygen: 20 Pa = 81 K 30 Pa = 92 K 40 Pa = 80 K 50 Pa = 75 K Nitrous oxide: 10 Pa = 70 K 20 Pa = 82 K 30 Pa = 87 K 40 Pa = 87 K 50 Pa = 88 K Nitrogen: 20 Pa = 82 K 30 Pa = 84 K 40 Pa = 89 K 50 Pa = 89 K Nitrous oxide: 350°C ox.-annealing T = 87 K 400°C ox.-annealing T = 89 K 450°C ox.-annealing T = 90 K Nitrogen: 350°C ox.-annealing T = 85 K 400°C ox.-annealing T = 88 K 450°C ox.-annealing T = 91 K |

50 K and self-field Oxygen: 10 Pa–0.8 MA/cm2 20 Pa–3.75 MA/cm2 30 Pa–6.75 MA/cm2 40 Pa–4.5 MA/cm2 50 Pa–3.8 MA/cm2 Nitrous oxide: 10 Pa–0.75 MA/cm2 20 Pa–1.5 MA/cm2 30 Pa–3.75 MA/cm2 40 Pa–4.3 MA/cm2 50 Pa–5.3 MA/cm2 Nitrogen: 10 Pa–0 MA/cm2 20 Pa–1.5 MA/cm2 30 Pa–3 MA/cm2 40 Pa–3.1 MA/cm2 50 Pa–3.3 MA/cm2 |

(00L)-oriented SrTiO3 single crystal substrate | Guo et al.75 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) doped with 4 vol. % BHO and 3 vol. % Y2O3 | PLD | KrF excimer laser (248 nm); Fluence: 1.6 J/cm2; Repetition frequency: 8.0 Hz; Growth temperature of 790°C–825°C; Oxygen partial pressure: 300 mTorr; All samples were further annealed at 500°C for 30 min approximately at one atmosphere oxygen pressure. |

At 790°C = 86.66 K; At 810°C = 88.82 K; At 825°C = 89.31 K; |

Self-field 65 K: At 810°C–3 MA/cm2; At 825°C–2 MA/cm2; At 790°C–0.6 MA/cm2; Self-field 50 K: At 810°C–5 MA/cm2; At 825°C–2.8 MA/cm2; At 790°C–2 MA/cm2; Self-field 5 K: At 810°C–20 MA/cm2; At 825°C–6.5 MA/cm2; At 790°C–4.5 MA/cm2; |

(100) LaAlO3 (LAO) single crystal substrate | Sebastian et al.77 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) doped with CeO2 | PLD | Oxygen atmosphere: 800°C–840°C; Then the samples were annealed at 500°C in flowing O2 gas for 5 h. |

NA | 77 K, self-field: 1 mol % CeO2 @ 830°C = 100 A; 2 mol % CeO2 @ 830°C = 75 A; 3 mol % CeO2 @ 820°C = 65 A; |

IBAD-MgO | Wang et al.79 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm); Laser energy: 250 mJ; Repetition rate: 60 Hz; Target–substrate distance: 4 cm; Deposition temperature: 800°C; Pure oxygen pressure: 200 mTorr110 |

NA | 221 nm CeO2, 77 K, selffield = 4.6 MA/cm2 | IBAD-MgO with CeO2 buffer layer | Wu et al.113 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD velocity filtration | A rotating disk with a window was used as a velocity filter. The window diameter: 8, 6, and 4 mm; Distance from the axis of rotation: 75 mm; Distance from the target: 30–35 mm; Rotational speed of the disc: 100 Hz. KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm); Pulse energy up to 200 mJ; Pulse duration 15 ns; Pulse repetition rate up to 20 Hz; Substrate temperature: 700°C–760°C Pressure: 0.4–0.8 Torr of the oxidizer gas (nitrous oxide N2O or oxygen O2); At the end of the deposition, the temperature of the substrate heater was lowered to 500°C, after which the deposition chamber was filled by air to a pressure of 1 atm. |

81.5 K | 40 MA | SrTiO3 | Il’in et al.129 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | KrF UV excimer laser (λ = 248 nm); Pressure: 0.1 mPa; Target-substrate distance: 45 mm; Power density: 2.0 J/cm2; Laser frequency: 2 Hz; The O2/Ar with the mass flow rate ratio of 100:0, 75:25, 25:75; The deposition pressure (O2/Ar): 15 Pa; The substrate temperature: 795°C; After the deposition, O2 was input into the chamber to 0.1 MPa before the films were cooled to 520°C at the rate of 10°C/min; For the full oxidation of the YBCO, the temperature was maintained at 520°C for 30 min; The samples were then cooled down to room temperature at the rate of 5°C/min. |

∼90 K | NA | SrTiO3 | Dai et al.76 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | Excimer XeCl laser (λ = 308 nm); Pulse duration: 25 ns; Repetition rate: 60 Hz; Laser pulse energy:100–280 mJ; Oxygen pressure: 0.1–0.6 Torr; Substrate temperature: 750°C; After growth, the samples were annealed in pure oxygen at one atmosphere for 20 min at 650°C. |

92.1 K | 1.6 MA/cm2 (77 K) | LaAlO3 (001) | Xiong et al.90 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm); The laser energy: 350 mJ; Substrate temperature 800°C; The oxygen pressure: 200 mTorr; The laser repetition rate: 60 Hz; YBCO films thickness: 400 nm; YBCO films were quickly cooled to room temperature. |

NA | 4 MA/cm2 (77 K, self-field) | (RABiTS) Ni-5%W tapes, then CeO2 seed layer, YSZ barrier layer, and CeO2 cap layer | Xiao et al.110 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | KrF excimer laser (LPX220); Laser beam incident angle: 45°; After depositing the silver layer as a protection layer, the YGBCO films were annealed in flowing O2 gas at 500°C for 4 h |

NA | 40 nm (CeO2+In) = 140 A (77 K, self-field) | CeO2/IBAD-MgO/Y2O3/Al2O3/Hastelloy C276 substrates |

Liu et al.112 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) doped with BZO and Y2O3 | PLD | KrF excimer laser; Energy: 450 mJ Repetition rate: 8 Hz; Oxygen pressure: 40 Pa; Followed by annealing at 500°C in an O2 atmosphere for 30 min. |

Undoped YBCO (ave.) ∼89 K; 825°C deposition (ave.): 2% BZO +3%Y2O3 ∼83 K; 4% BZO +3% Y2O3 ∼85 K; 6% BZO +3% Y2O3 ∼87 K; 810°C deposition (ave.): 2% BZO +3% Y2O3 ∼85 K; 4% BZO +3% Y2O3 ∼88 K; 6% BZO +3% Y2O3 ∼87 K; |

YBCO: 30 MA/cm2 (0 T, 5 K) 7 MA/cm2 (9 T, 5 K) 3 MA/cm2 (0 T, 65 K) 5 kA/cm2 (9 T, 65 K) 2% BZO YBCO: 50 MA/cm2 (0 T, 5 K) 8 MA/cm2 (9 T, 5 K) 8 MA/cm2 (0 T, 65 K) 20 kA/cm2 (9 T, 65 K) 2%BZO+3% Y2O3 YBCO: 40 MA/cm2 (0 T, 5 K) 10 MA/cm2 (9 T, 5 K) 5 MA/cm2 (0 T, 65 K) 0.2 MA/cm2 (9 T, 65 K) |

SrTiO3 (STO) single crystal | Sebastian et al.78 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | Nd-YAG laser (λ = 266 nm); The deposition process was off-axis, i.e., with the substrate surface perpendicular to the target; Deposition time: 5, 10, 30 min; Substrate temperature: 670°C–710°C; Oxygen pressure: 300 mTorr; Target-substrate distance: 2, 3, 4 cm; All the samples underwent the same annealing process, at 500°C, 1 atm of O2 during 30 min. Subsequently, they were slowly cooled to nearly room temperature in the same O2 atmosphere. |

30 min deposition time: 690°C (Td), 4 cm (d) ∼83 K; 670°C (Td), 3 cm (d) ∼85 K; 670°C (Td), 2 cm (d) ∼87 K; 710°C (Td), 2 cm (d) ∼88 K; 690°C (Td), 2 cm (d) ∼89 K; 690°C (Td), 2 cm (d): 30 min (td) ∼88 K; 10 min (td) ∼81 K; 5 min (td) ∼79 K; |

NA | SrTiO3 (STO) single crystal | Favre et al.92 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | Excimer XeCl (λ = 308 nm) laser; Pulse duration: 25 ns; Repetition rate: 5 Hz; Laser fluence: 1.3 J/cm2; Deposition temperature (undoped films): 730°C; Target-substrate distance: 32 mm; Oxygen pressure: 23 Pa; After the deposition, an oxygenation step of 10 min at 700°C in 1 atm of pure O2 was made for all the films.130 |

Silver paste: STO ∼90 K; MgO, LSAT, SLAO, NGO ∼87 K; Mask (2): STO, SLAO, MgO ∼87 K LSAT ∼90 K; |

Silver paste (0 T, 10 K): STO ∼80 MA/cm2; LSAT, SLAO ∼70 MA/cm2; MgO ∼20 MA/cm2; NGO ∼1.5 MA/cm2 Mask (2) (0 T, 10 K): STO ∼50 MA/cm2; MgO, SLAO ∼15 MA/cm2; LSAT ∼7 MA/cm2; NGO ∼0.5 MA/cm2 |

SrTiO3 (STO), MgO, (LaAlO3)0.3(Sr2AlTaO6)0.7 (LSAT), SrLaAlO4 (SLAO), and NdGaO3 (NGO), all in the (001) orientation. | Huhtinen et al.115 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | A KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm, τ = 30 ns); To improve deposition reproducibility, the laser beam was cropped with an aperture so that only the part with the most uniform energy distribution passed to the target; Target-substrate distance: ∼60 mm; Energy densities on target: 1.5–1.8 J/cm2; Ambient gas pressure: 0.5–1 mbar; Scanning of the 2.5 × 2.5 mm2 laser spot across the target surface was in a meander pattern inside a square area; To avoid atmospheric contaminations, the target surface was cleaned and repolished; Substrate temperature: 770°C; Pressure: 0.8 mbar; Ar/O2 flow ratio 8/2 sccm; Repetition rate: 2 Hz; Deposition rate: ∼0.165 nm/s; p Post-deposition oxygenation in 500 mbar O2 at 450°C for 1 h. |

Best performing ∼87 K | NA | (001) SrTiO3 | Mozhaev et al.87 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | Ultrahigh-Speed PLD | XeCl excimer laser (λ = 308 nm); Maximum pulse energy: 550–650 mJ; Pulse duration: 22 nm ± 5 nm; Maximal repetition rate: 200 Hz; Energy density: 3–10 J/cm2 |

NA | Ic: 500–700 A/cm-width, Jc: <1.5 MA/cm2 (77 K, self-field) | YSZ/Cr-Ni stainless steel | Rutt et al.74 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) with BaZrO3 (BZO) | PLD | KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm); Pulse length: 25 nm; Laser repetition rate: 2–4 Hz; Target-substrate distance 5.5 cm; Heater block temperature: 775°C–790°C; Dense targets: 83–90%; Oxygen partial pressure: 300 mTorr; Post-deposition anneal at 500°C and 1 atm of oxygen |

Multiple: ∼89 K Single: ∼88–90 K |

77 K, self-field: Multiple: 4 MA/cm2; Single: 5 MA/cm2 (0 vol % BZO); 2 MA/cm2 (2 vol % BZO) |

LaAlO3, SrTiO3 | Haugan et al.88 |

| YBa2Cu3O7-x (YBCO) with BaZrO3 (BZO) and Y2O3 | PLD | KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm); Fluence:1.6 J/cm2; Laser energy: 450 mJ; Repetition rate: 8 Hz; Oxygen pressure: 300 mTorr; Heater block temperatures: 825°C for 7 min; After deposition, the films were annealed for a 30-min dwell time at 500°C and an oxygen atmosphere. |

81.19 K (2% BZO), 87.69 K (4% BZO), 87.80 K (6% BZO) | NA | SrTiO3 | Chen et al.97 |

| YBa2Cu3O7-x (YBCO) + BaZrO3 (BZO)/YBa2Cu3O7-x + Y2O3 (multilayered) | PLD | KrF excimer laser; Alternating targets; Substrate temperature: 800°C; Oxygen partial pressure: 28 Pa; After completion of the YBCO thin-film deposition, the films were cooled down to 500°C in 5 104 Pa oxygen and held at this temperature for 1 h before cooling down to room temperature. |

NA | 2.66 MA/cm2 (77 K, self-field) 0.3 MA/cm2 (77 K, 2 T) |

LaAlO3 (100) | Liu and Du98 |

| YBa2Cu3O7-x (YBCO) + BaZrO3 (BZO) (5 mol %) | PLD | Deposition temperature: 745°C–840°C; Oxygen pressure: 200 mtorr; Laser repetition rates: 2–15 Hz |

NA | Up to 3 MA/cm2 at 75.5 K, self-field; strong Jc retention at high fields | SrTiO3 | Maiorov et al.93 |

| YBa2Cu3O6+x (YBCO) | PLD | Deposition temperature: 790°C; Oxygen pressure: 0.3 Torr; The same number of pulses and exactly the same laser fluency for all samples. |

4.1 g/cm3: ∼88.7 K 4.3 g/cm3: ∼88.3 K 5.0 g/cm3: ∼89.3 K |

10 K, 0 T: 4.1 g/cm3: 32 MA/cm2 4.3 g/cm3: 22.2 MA/cm2 5.0 g/cm3: 29.9 MA/cm2 |

SrTiO3 (100) | Paturi et al.84 |

| YBa2Cu3O7-x (YBCO) pure or + BaZrO3 (BZO) (1.5, 3.5, wt %); ErBa2Cu3O7-d (ErBCO) + BaSnO3 (BSO) (2, 4 wt %) |

PLD | ArF excimer laser (λ = 198 nm) Repetition rate: 1 Hz; Laser energy: 400 mJ; Oxygen pressure: 400 mTorr; Substrate temperature: 715°C (0, 1.5, 3.5wt %); 730°C (2, 4 wt %) |

0 wt %: 90.3 K 1.5 wt %: 91.3 K 3.5 wt %: 86.9 K 2 wt %: 87.1 K 4 wt %: 86.4 K |

0 wt %: ∼1 MA/cm2 (77. 3 K; 0T) ∼7 kA/cm2 (77. 3 K; 5T) 1.5 wt %: ∼3 MA/cm2 (77. 3 K; 0T) ∼0.2 MA/cm2 (77. 3 K; 5T) 3.5 wt %: ∼2 MA/cm2 (77. 3 K; 0T) ∼60 kA/cm2 (77. 3 K; 5T) 2 wt %: ∼3 MA/cm2 (77. 3 K; 0T) ∼60 kA/cm2 (77. 3 K; 5T) 4 wt %: ∼0.8 MA/cm2 (77. 3 K; 0T) ∼60 kA/cm2 (77. 3 K; 5T) |

SrTiO3 (100) | Sueyoshi et al.99 |

| YBa2Cu3O7-δ (YBCO) + Tb (0.1, 1, 10%) or + Ce (0.1, 1, 10%) | PLD | KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm) Laser pulse rate: 4 Hz; Laser fluence: 3.2 J/cm2 Target-substrate distance: 6 cm; Oxygen pressure: 300 mTorr O2; Deposition temperature 780°C |

0%: 89.2 K Tb 0.1%: 88 K Tb 1%: 89 K Tb 10%: 89.5 K Ce 0.1%: 88.9 K Ce 1%: 88.5 K Ce 10%: 84.8 K |

77 K, 0.01 T: 0%: 2.23 MA/cm2; Tb 0.1%: 3.13 MA/cm2; Tb 1%: 2.68 MA/cm2; Tb 10%: 3.43 MA/cm2; Ce 0.1%: 1.65 MA/cm2; Ce 1%: 2.1 MA/cm2; Ce 10%: 0.52 MA/cm2; 77 K, 2 T: 0%: 0.14 MA/cm2; Tb 0.1%: 0.107 MA/cm2; Tb 1%: 0.162 MA/cm2; Tb 10%: 0.1 MA/cm2; Ce 0.1%: 0.099 MA/cm2; Ce 1%: 0.056 MA/cm2; Ce 10%: 0.001 MA/cm2; |

SrTiO3 (100), LAO (100) | Kell et al.94 |

| YBa2Cu3O7-x (YBCO) pure or + BaZrO3 (BZO) + Y2O3 | PLD | KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm) Laser frequency: 5 Hz; Target–substrate distance: 5 cm; Deposition temperature of 780°C–800°C; Oxygen pressure: 200 mTorr; After deposition, the films were cooled to room temperature with an oxygen pressure of 200–300 Torr. All films were then annealed in an oxygen atmosphere at 550°C for 30 min. |

NA | 65–75.5 K, self-field: 5.8 MA/cm2 at 0.2 μm thickness 2.3 MA/cm2 at 6.4 μm thickness |

SrTiO3 | Zhou et al.105 |

| YBa2Cu3O7-x (YBCO) | PLD | KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm, 4 Hz); Deposition temperature: 775°C–825°C; Oxygen pressure: 300 mTorr |

NA | 77 K, self-field: 775°C: 2.22 MA/cm2; 790°C: 2.19 MA/cm2; 800°C: 2.20 MA/cm2; 825°C: 2.63 MA/cm2; 65 K, 3T: 775°C: 0.94 MA/cm2; 790°C: 1.02 MA/cm2; 800°C: 1.12 MA/cm2; 825°C: 1.3 MA/cm2; |

SrTiO3, LaAlO3 | Wang et al.80 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD | ND:YAG laser (λ = 266 nm); Repetition frequency: 10 Hz; YBCO thicknesses: 0.4–4.0 μm; Substrate temperature: (Ts0 = 850°C, Ts∞ = 1045°C); Oxygen partial pressure: 400 mTorr; Laser energy density: 1.25 J/cm2; In order to reduce oxygen deficiency, post-annealing in an oxygen atmosphere of about 1 atm was performed. |

NA | 2.0 MA/cm2 (77 K, 0 T) | IBAD-MgO | Sato et al.82 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) with BaHfO3 (BHO) doping | Off-axis PLD | KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm); Off-axis: Energy density: 2.7 J/cm2; Laser repetition rate: 9 Hz; Substrate temperature: 850°C; Substrate rotation: yes; Oxygen pressure: 0.7 mbar; Deposition rate: 0.4 Å/pulse; After the deposition, oxygen loading took place in situ during cool-down at 15 K/min in 400 mbar O2. |

89-93 K | ∼1 MA/cm2 (77 K, 0 T); ∼0.1 MA/cm2 (77 K, 3 T); |

SrTiO3 (100) | Backen et al.89 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) doped with BaSnO3 (BSO) | PLD combinatorial | ND:YAG laser (λ = 266 nm); Target-substance distance: 20–40 mm; Laser energy density: 2.0 J/cm2; Repetition frequency:1 Hz The laser irradiated area on the target in ellipsoid shape with a major diameter of 2.1 mm and a minor diameter of 1.7 mm; Heater temperature: 900°C–920°C; Oxygen pressure: 40–300 Pa; After the deposition, the chamber was filled with oxygen to atmospheric pressure, and the substrate temperature was rapidly dropped to 400°C and kept for 30 min. |

SrTiO3 substrate ∼90 K | SrTiO3 substrate ∼2.5 MA/cm2 (77 K, self-field) | MgO (100), SrTiO3 (100) |

Ichino et al.116 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | HR-PLD (VAA, QEH) | NA – some details could be found in the earlier publications of the research group119,131 | NA | 2–3 MA/cm2 (1 μm-thick); >1.4 MA/cm2 (3 μm-thick) |

Yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) buffer layer on stainless steel | Usoskin and Freyhardt 120 |

| YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) | PLD-QEH | Substrate drum with speed >20 rad s−1; Oxygen post-loading at about 500°C | 84-89 K | 309 A at 31 T, 500 A at 18 T, 1200 A at 5 T (4.2 K) | Yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) buffer layer on Cr-Ni Stainless Steel | Abraimov et al.121 |