Abstract

Retinal diseases affect the health of millions of people worldwide and activated P2X7 receptors (P2X7Rs) are associated with the pathophysiology of a variety of retina-related diseases, including diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Increasing evidence indicated that P2X7R is over-activated in retinopathy and is involved in the occurrence and development of diabetic retinopathy. Purine vasotoxicity caused by over-activation of P2X7R can lead to decreased retinal blood flow and vascular dysfunction and activation of P2X7R can lead to the production of a large number of inflammatory factors, causing local inflammatory cells to infiltrate and form a vascular microenvironment, thus constituting the pathophysiological basis for the occurrence and development of retinopathy. A variety of P2X7R antagonists have been studied in clinical trials as potential treatments for retinal diseases. However, currently no P2X7R antagonists has been approved for retina diseases. In this review, we mainly focus on recent progress on the involvement of P2X7R in retinal diseases and its therapeutic potential in the future.

Keywords: P2X7 receptor, Diabetic retinopathy, Age-related macular degeneration, Glaucoma

Introduction

Retinal diseases are among the leading causes of vision loss and blindness worldwide. The hallmark pathological features of retinopathy include the damage and apoptosis of various retinal neurons, particularly in photoreceptor cells. Millions of people globally suffer from retinal diseases, which manifest in a wide range of pathological and physiological changes, such as diabetic retinopathy (DR), glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and choroidal neovascularization (CNV) [1]. Ocular complications are common in patients with DR, a condition closely associated with diabetes, affecting approximately 30%–40% of diabetic patients. With the aging global population, some estimates predict that by 2040, the number of glaucoma patients will reach 111.8 million, and the number of AMD patients will rise to 288 million [2–4]. Studies have shown that P2X7 receptors (P2X7R) are expressed in various retinal cell types and play a crucial role in the progression of retinal diseases. The activation of P2X7R is linked to retinal neuron degeneration and the release of abnormal signals. By downregulating or blocking P2X7R activation, the activation of retinal glial cells can be significantly reduced, thereby mitigating neuronal damage and apoptosis [5]. Current treatment strategies for retinal diseases primarily involve the injection of biologics targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) into the vitreous body or retinal surgery in advanced disease stages. However, many patients continue to experience vision loss or blindness despite long-term treatment. For instance, primary open-angle glaucoma leads to vision loss due to the gradual dysfunction of retinal ganglion cells, often caused by elevated intraocular pressure. Although intraocular pressure-lowering treatments can manage the condition, approximately 30% of patients still suffer from vision loss, which, in severe cases, can result in insomnia.

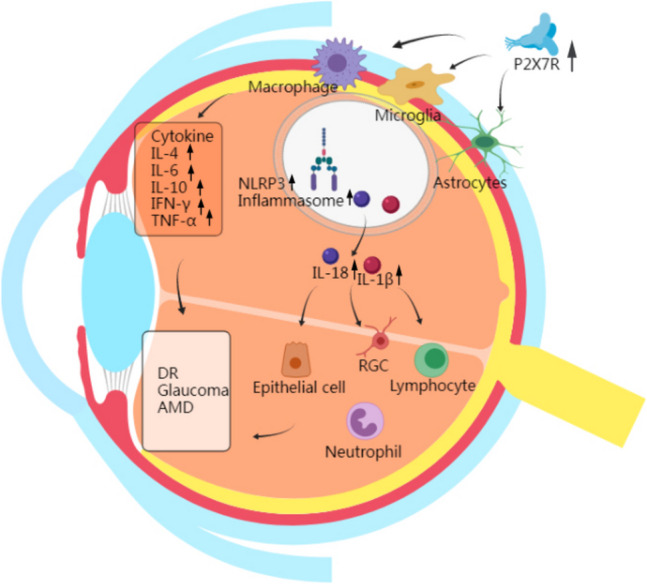

Given the lack of effective treatments for retinal diseases, identifying new therapeutic targets and developing novel drugs have become research priorities. Recent studies suggest that P2X7R may serve as a promising therapeutic target for retinal diseases, including AMD, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma [6, 7]. In particular, one study demonstrated that activation of the P2X7R-NLRP3 inflammatory complex leads to retinal cell damage or death, contributing to the pathogenesis of glaucoma, AMD, and diabetic retinopathy (Fig. 1). This review aims to examine the current evidence supporting the involvement of P2X7R signaling in retinal disease pathogenesis and explores the potential of P2X7R-targeted therapies.

Fig. 1.

P2X7Rs is highly expressed in macrophages, lymphocytes, retinal microglia, and astrocytes, which act as mediators of inflammation and deliver cytokines into the retinal tissue. Activation of the P2X7R-NLRP3 inflammasome results in activation of the inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, resulting in abnormal regulation of the cytokine network. Meanwhile, NLRP3 inflammasome activation occurs in macrophages, astrocytes, and microglia where P2X7R is involved in activation, and IL-1β and IL-18 can be sensed by all cells in the inflammation of the optic nervous system, which is a central element in the development of retinal inflammation

Distribution of P2X7R in the retina

In various forms of retinopathy, different retinal cells exhibit distinct molecular mechanisms of pathological response. Additionally, intracellular ATP metabolism plays a key role in regulating the pathophysiological processes of the retina, influencing molecular mechanisms, metabolic activity, electrical functions, and overall retinal homeostasis [8]. Studies have shown that P2X7R is expressed in multiple retinal cell types, including neurons, glial cells, and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells [9]. Specifically, P2X7R expression has been detected in the inner retinal layers, including the ganglion cell layer, as well as in visual bipolar cells, photoreceptors, retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), and secretory glandular cells in animal models. Further research using P2X7 knockout mice, treated with the P2X7 agonist BzATP, has confirmed the expression of P2X7R in these retinal cell types [10].

The role of RGCs in these pathological processes cannot be overlooked, as they interact with a wide range of retinal cells to maintain the stability of the retinal environment and mitigate disease progression. Consequently, the activation and proliferation of glial cells represent a common response in nearly all retinal diseases. Recent studies have also demonstrated that P2X7R is expressed in Müller cells and microglia, two primary endogenous retinal glia. The activation of P2X7R in these cells regulates glial responses and the functional changes of Müller cells in particular. Microglia and Müller cells work synergistically and influence one another’s activity. Together, they contribute to retinal damage by modifying both morphological and functional responses, which can influence the extent of damage in retinal neurons and photoreceptors [11, 12]. Moreover, studies have shown that the P2X7R exacerbates the progression of retinal diseases by enhancing the activation of both A1-type and A2-type astrocytes, leading to the upregulation of upstream inflammatory markers [13].

Furthermore, the increased activation of P2X7R has been shown to promote the release of inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), which contribute to retinal cell injury and apoptosis. In pathological retinal conditions, the heightened expression of P2X7R can increase the susceptibility of retinal neurons to damage, suggesting that targeting P2X7R may offer a potential therapeutic approach for treating retinal diseases [14].

P2X7R in diabetic retinopathy

The BRB is a protective structure composed of endothelial cells, microglia, astrocytes, and pericytes, with an internal structure resembling that of the blood–brain barrier. This architecture serves to protect the retina from damage induced by high glucose levels [15]. The BRB is essential for maintaining the homeostasis of the retinal microenvironment. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) has a detrimental effect on the BRB, which may precede microvascular abnormalities. The apoptosis of neuronal cells can further exacerbate microvascular damage, leading to the destruction of the BRB. Diseases such as diabetic retinopathy (DR), acute glaucoma, and retinopathy of prematurity have been shown to impair the BRB. Additionally, pericellular injury and apoptosis can disrupt the internal structure of the BRB (iBRB). Recent studies have highlighted the significant role of cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) as an immune signaling molecule in the immune response associated with retinal diseases. Research has demonstrated that cGAMP is transported into microglia through P2X7R-mediated pathways, further promoting the disruption of the iBRB [16]. The role of P2X7R activation in high-sugar-induced pericellular death has been progressively confirmed through both in vitro and in vivo studies [17–19]. Shibada et al. described retinal microvascular toxicity induced by P2X7R activation, marked by an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and synergistic activation of KATP current channels, alongside pericellular contraction [20]. This activation leads to an increase in the secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) by astrocytes, and the structural integrity of the BRB is compromised due to the imbalance of claudin-5 and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), which are key components of tight junctions in the retina [21]. Recent findings indicate that P2X7R activation also significantly alters the expression levels of connexins such as ZO-1, claudin-5, and VE-cadherin. By modulating these abnormal protein expressions, it has been confirmed that P2X7R disrupts the integrity of tight junctions between retinal endothelial cells in a high-glucose environment. This provides further evidence supporting the hypothesis that P2X7R activation contributes to iBRB breakdown [22]. Furthermore, exposure to the P2X7R agonist BzATP has been shown to increase barrier permeability, as measured by transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER), while decreasing ZO-1 and VE-cadherin levels, as well as Cx-43 mRNA expression, thereby promoting BRB degradation [23]. Subsequent studies employing various in vitro cell models, including periretinal cells, astrocytes, and endothelial cells, have identified diterpene dihydrotanshinone (DHTS) as a P2X7R inhibitor that preserves the structural and functional integrity of the BRB [23]. Cluster analysis of DHTS and the P2X7R antagonist JNJ47965567 further suggests that DHTS may have therapeutic potential in preventing or reversing BRB dysfunction caused by hyperglycemia and P2X7R activation.

Although peri-cellular loss is considered an early pathological change in DR, studies in DR mouse models have shown that local retinal blood vessel leakage occurs earlier in the disease process than peri-cellular loss, even preceding it [24]. Macular edema, which results from vascular leakage, can manifest at any stage of DR and is a major cause of vision loss in patients with central retinal vein occlusion and DR [25]. Therefore, alterations in the structure and function of retinal endothelial cells play a crucial role in the onset and progression of retinal diseases, and serve as important pathological markers for DR. The expression of P2X7R is significantly elevated in human retinal endothelial cells cultured in high glucose concentrations [22]. P2X7R interacts with the inflammasome, and co-localization of P2X7R and the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat, and pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) is observed in the cytoplasm, a process that is ATP-dependent. As an ATP-activated ion channel, P2X7R is activated upon ATP binding, leading to increased membrane permeability and subsequent potassium efflux. This efflux is a critical event that triggers the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [26, 27]. The reduction in intracellular potassium levels during P2X7R activation induces the assembly and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18. This inflammatory cascade also activates Caspase-1, which induces pyroptosis, a form of inflammatory cell death [28]. Pyroptosis in retinal endothelial cells disrupts the BRB, leading to increased retinal permeability, vascular leakage, and neovascularization [29, 30], which are key contributors to the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Studies in mice and various cell models have demonstrated that the release of these cytokines not only exacerbates local inflammation but also propagates through paracrine signaling to adjacent retinal cells, thereby further amplifying retinal damage (Fig. 2) [31].

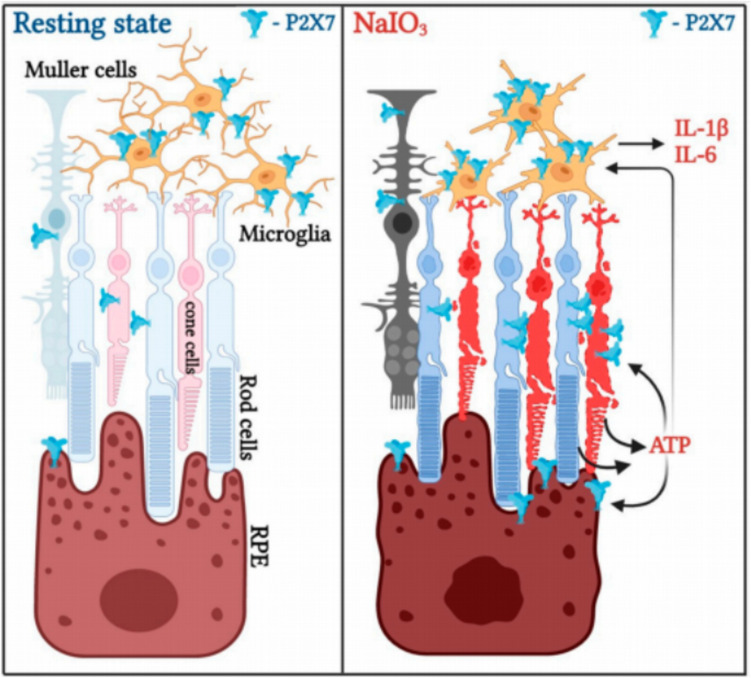

Fig. 2.

The process of P2X7 activation in the amplification of neuroinflammation and retinal cell death caused by NaIO3. Under typical circumstances, P2X7 is consistently and significantly more prevalent in microglia compared to photoreceptors, RPE, and Müller cells. NaIO3 treatment induces upregulation of P2X7 expression in photoreceptors, Müller cells, and RPE cells, leading to cell death in these cell types as well as microglia. ATP released from dying and injured cells functions as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) to stimulate the activation of microglia, leading to the expression of inflammatory genes IL-1β and IL-6. Elevated levels of ATP may also facilitate the demise of RPE cells in the presence of NaIO3-induced stress

P2X7R in glaucoma

Glaucoma is an ocular disease characterized by the damage to RGCs and the progressive degeneration of the optic nerve, with progressive vision loss being its primary clinical manifestation [32]. Glaucoma not only damages RGCs but may also cause transsynaptic degeneration, leading to the atrophy of the lateral geniculate body, shrinkage of neuronal cell bodies, and a decline in neuronal activity, as confirmed in both animal models and human studies [33]. P2X7R is expressed at varying levels across different retinal layers, where it may regulate retinal synaptic transmission and neuronal death through distinct pathways, thus playing a role in the pathological mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases [34–36]. Although several studies have clarified the regulatory mechanisms that contribute to RGC death in glaucoma, including mitochondrial dysfunction, activation of exogenous and endogenous apoptotic pathways, and abnormal oxidative stress pathways [37], the upregulation of P2X7R in both acute and chronic intraocular pressure (IOP) models triggers neuroinflammation and cellular damage, leading to RGC functional decline. P2X7R activation induces RGC death through mechanisms such as increased intracellular calcium levels and oxidative stress pathways [38–41].

In addition to directly affecting RGCs, P2X7R also modulates retinal glial cells, particularly microglia and astrocytes, thereby exacerbating glaucoma pathology. Upon activation, P2X7R induces microglia to shift from a resting state to an activated state. Under elevated IOP conditions, glial cells proliferate and migrate to the Ganglion Cell Layer, contributing to RGC injury by releasing various harmful mediators, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and nitric oxide [42–45]. Notably, the sustained activation of the P2X7R-NLRP3 inflammasome pathway is considered a major factor in initiating and sustaining chronic inflammation, further exacerbating RGC apoptosis and optic nerve degeneration [46]. Recent studies have revealed that Müller cells and microglia interact in the pathological process of retinal injury, with positive regulation enhancing retinal inflammation [47–49]. Hu et al. demonstrated that in experimental glaucoma, Müller cells regulate retinal cell survival through calcium influx mediated by the TRPV1/PLCγ1 complex [50]. The retinas of mice with experimental glaucoma activated Müller cells interact with microglia and release ATP signals via the CX43 channel. ATP, in turn, induces the proliferation and migration of microglia by acting on P2X7R through the intracellular MEK/ERK signaling pathway [51]. Furthermore, studies suggest that P2X7R activation not only induces inflammatory responses but also promotes microglial senescence, thereby diminishing their neuroprotective effects. ATP-P2X7R exacerbates retinal microglial senescence by inhibiting the PINK1-mediated mitochondrial autophagy pathway, thereby accelerating RGC death in the COH model [52]. Akayuki et al. demonstrated that P38/MAPK signaling molecules play a role in the pathophysiology of RGC survival and apoptosis [53]. Moreover, research has shown that purines can regulate ROS expression through P2X7R, further stimulating the activation of the P38/MAPK phosphorylation pathway [54]. Other studies suggest that inhibiting P2X7R can reduce ROS production, thereby suppressing P38 phosphorylation and protecting RGCs from damage and apoptosis [55].

Several P2X7R antagonists, such as Brilliant Blue G (BBG) and A839977, have shown promising therapeutic effects in animal models, including the mitigation of RGC apoptosis, suppression of microglial overactivation, and improvements in visual outcomes in certain models [56]. Recent studies also support the P2X7 receptor antagonist A740003 significantly protecting RGCs in experimental glaucoma, slowing down cell death and optic nerve degeneration [57]. P2X7R inhibitor A438079 and NLRP3 inhibitor Mcc950 have also demonstrated protective effects on RGCs by inhibiting microglial activation in rat chronic ocular hypertension (COH) models, consistent with previous findings [58]. In addition to directly targeting P2X7R, combining NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors with other anti-inflammatory agents could have synergistic effects. For instance, modulating the P2X7R-NLRP3 pathway, which is central to glaucoma pathogenesis, suggests that simultaneous inhibition of both P2X7R and NLRP3 may further reduce optic nerve inflammation and improve RGC survival [59]. Studies on mitochondrial molecular mechanisms have shown that mitochondrial autophagy promotes mitochondrial repair and regeneration, which is vital for the repair and regeneration of Müller cells, microglia, and other retinal cells [60]. However, some researchers argue that P2X7R may play a role in neuronal death or injury in retinal and cerebellar neurons [61–64]. In response to this, research has suggested that the role of P2X7R in early IOP injury may differ from its role in persistent or ischemic IOP injury, indicating that the treatment of P2X7R in glaucoma should be approached with caution [65].

Despite the critical role of P2X7R in glaucoma pathogenesis, clinical applications still face challenges. The multifunctionality of P2X7R necessitates precise modulation of its activation state to avoid potential side effects. Therefore, further investigation into the molecular mechanisms of RGC specificity and sensitivity is crucial for advancing glaucoma treatment and providing a reliable foundation for future clinical interventions.

P2X7R in age-related macular degeneration

Extracellular accumulation of various deposited substances adheres to the retina, ultimately leading to degeneration of optic nerve photoreceptors and reduced or even loss of central vision in age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The early pathological feature of AMD is the formation of yellow, sedimentary aggregates called “drusen” beneath the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells and their basement membrane. In advanced AMD, the pathological characteristics include gradual atrophic changes or pigment disorders in retinal cells or tissues, accompanied by the formation of new blood vessels within the retinal tissue [66]. Dry macular degeneration is characterized by the progressive atrophy of the macular region, retinal thinning, and a reduction in nerve fibers, resulting in decreased vision, slight distortion of visual perception, and the appearance of dark areas in the central visual field. Wet macular degeneration involves proliferative pathological changes due to the formation of choroidal neovascularization, which leads to recurrent bleeding and leakage, thereby causing visual deterioration and distorted vision [66]. Recent studies have indicated that P2X7R may be involved in various pathological processes of AMD, particularly through the P2X7R-NLRP3/Caspase-1 inflammasome pathway. The inherent defect of P2X7R’s dependence on phagocytosis may contribute to the accumulation of deposits in the development of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) and promote the progression of AMD. However, overactivation of P2X7R may exacerbate harmful pro-inflammatory reactions by promoting photoreceptor degeneration and choroidal neovascularization in advanced AMD [67]. Additionally, recent studies suggest that oxysterols, as oxidative derivatives of cholesterol, contribute to degenerative eye diseases, mainly by activating the P2X7 receptor and promoting local inflammation and cell death. This mechanism may underlie retinal microvascular damage and impaired blood supply [68].

β-amyloid oligomer (AβO) is considered reliable molecular biomarkers for neurodegeneration and are implicated in the degeneration of the RPE in geographic atrophy (GA). AβO acts as a stressor associated with the complex pathogenesis of GA [69]. Activation of the P2X7R-NLRP3 inflammasome complex has been identified as a key stress factor in AβO-induced RPE degeneration. During retinal photodamage, purine signaling via P2X7R is overexpressed and closely linked to damage in photoreceptors and neurons in retinal damage models [70]. The activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome mediated by P2X7R is a crucial pathway for RPE degeneration in the GA model, and this process depends on the P2X7R/NLRP3 pathway to a significant extent in the retinal photodamage response [71]. The absence of P2X7R or the intravitreal delivery of the P2X7R antagonist A740003 has been shown to protect against Alu RNA-induced RPE cell death [71]. P2X7R may promote the degeneration of the RPE in GA by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome, with the degree of activation of its complement system also considered a potential stressor in GA pathogenesis [72]. Inflammasome activation has been identified as an important driver of complement-induced RPE cytotoxicity in both RPE cell models and animal models [73]. In the absence of ATP, unactivated P2X7R functions as an inactivated receptor, mediating the phagocytic activity of macrophages, monocytes, mouse peritoneal macrophages, and microglia against bacteria and apoptotic cells [74]. In the wet AMD mouse model induced by laser-induced CNV, destructive invasion of choroidal neovascularization into the subretinal space is observed, along with the accumulation of mononuclear phagocytes (MPs) around the lesion. P2X7R deficiency in older animal models results in the development of early AMD characteristics, including thickening of the Bruch membrane, loss of RPE cells, and an increased presence of microglia/MPs in the subretinal region [75]. Measuring changes in membrane fluidity after ATP-mediated phagocytosis or pore formation, whether independently or in combination, may serve as a novel and valuable method for evaluating P2X7R activity, phagocytosis, and its contribution to disease. Recent studies have reported a link between these two key factors and age-related macular degeneration, although further in-depth research is necessary to confirm this relationship.

Therapeutic targeting of P2X7R in retinal diseases

P2X7R functional antagonists have been in clinical development for over a decade, and there has been notable progress in the development of P2X7R antagonists for the treatment of retinal diseases (Table 1). However, to date, no P2X7R antagonists have been approved for the treatment of retinal diseases, and no phase I, II, or III clinical trials investigating the use of P2X7R antagonists for eye diseases are currently underway.

Table 1.

Application of P2X7 antagonists in retinal diseases

| Compound name | Indications | Species | Human trials | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JNJ 47965567 | DR |

Human, rat, mouse |

No | [22, 83] |

| A438079 | Glaucoma |

Human, rat, mouse |

No | [27, 46] |

| A839977 | AMD | Mouse | No | [84, 85] |

| AZ10606120 |

AMD, DR |

Human, rat, mouse |

No | [85, 86] |

| A74003 |

DR, glaucoma, AMD |

Human, rat |

No | [86] |

| KN-62 | Retinal degenerative diseases |

Human, rat, mouse |

No | [87] |

|

Dihydrotanshinone (DHTS) |

DR |

Human, rat |

No | [23] |

|

Pyridoxalphosphate- 6azophenyl-2′,4′- disulfonic acid (PPADS) |

DR | Rat | No | [88] |

| 3TC | DR | Mouse | No | [7, 59] |

|

Gurigumu-13 (GRGM-130) |

Glaucoma | Rat | No | [55] |

The nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), known for its ability to inhibit P2X7R and subsequent NLRP3 activation, is typically used in antiviral therapies, primarily for the treatment of HIV. However, in the context of retinal diseases, NRTIs may represent a novel approach due to their potential to modulate immune responses and reduce inflammation. NRTIs have been proposed for repositioning as potential therapeutic strategies for several chronic diseases [76]. Interestingly, the anti-inflammatory effects of NRTIs are not related to their capacity to inhibit reverse transcriptase. A modified NRTI, known as Kamuvudine, which does not exhibit the associated toxicity, has emerged as a more promising candidate for the treatment of P2X7R-NLRP3-mediated inflammation. Kamuvudine retains the ability to inhibit inflammasome activation without affecting reverse transcriptase activity [77]. Based on evidence that P2X7R is a critical element in AβO-induced RPE degeneration, Narendran et al. demonstrated that both NRTI and Kamuvudine can prevent AβO-induced RPE degeneration [70]. Recent studies have shown that 3TC, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, possesses intrinsic anti-inflammatory properties targeting the P2X7R and NLRP3 inflammasome pathways [46, 78]. Previous data indicated that 3TC, through the inhibition of P2X7R activity, protected endothelial cells from diabetes-induced cell death [7]. An intriguing recent discovery could open new avenues for the treatment of diabetic retinopathy (DR). Specifically, 3TC has been shown to inhibit tissue damage, apoptosis, cytokine production, and the activation of inflammatory signaling pathways by targeting the P2X7R/NLRP3 pathway. Additionally, it reduces inflammatory, apoptotic, and pyroptotic effects induced by lipopolysaccharide in the presence of hyperglycemia [59]. Given the widespread clinical use of 3TC for HIV and hepatitis treatment and its established safety profile, further research into its potential role in DR management—both as a preventative and therapeutic agent—is warranted.

Currently, the main treatments for glaucoma include surgery, laser therapy, and conventional western medicine. Over 250 traditional Chinese medicines have been recorded in ancient texts for the treatment of ophthalmic diseases, potentially providing an alternative or complementary approach to current ophthalmic therapies [79]. Increasingly, researchers are recognizing the advantages of traditional Chinese medicine in glaucoma optic nerve protection, particularly due to its multi-component, multi-target, and integrative nature. Studies have shown that traditional Chinese medicines and their compounds or extracts have protective effects on the optic nerve and may enhance vision. For instance, Yin et al. confirmed that an extract from Erigeron breviscapus inhibits the outward potassium (K +) channel current in rat RGCs in a dose-dependent manner, thereby preventing visual loss and RGC damage in glaucoma [80]. Other researchers have found that Chi-Ju-Di-Huang-Wan has a protective effect on retinal ischemia caused by elevated intraocular pressure by inhibiting the p38 MAPK pathway [81]. Additionally, some studies have reported that GRGM13, a traditional medicine from Mongolia and Tibet composed of 13 independent medicinal herbs, can prevent oxidative stress-induced apoptosis of RGCs by inhibiting the P2X7R/p38 MAPK pathway [55].

However, some studies have suggested that chronic exposure to P2X7 receptor antagonists may be linked to an increased incidence of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in patients [82]. This raises concerns regarding the potential long-term effects of P2X7 receptor antagonists in the treatment of AMD. While these antagonists are effective in mitigating inflammation and cell death, their prolonged use may result in unforeseen side effects, necessitating further investigation in future clinical studies.

Conclusions and perspectives

Retinal degenerative diseases, including DR, glaucoma, and AMD, significantly threaten vision and currently lack effective treatments. The P2X7R has emerged as a promising pharmacological target due to its involvement in retinal inflammation and cell death pathways. Targeting P2X7R could protect retinal tissue and support neuronal function.

Although existing therapies for DR, glaucoma, and AMD show some efficacy, they are often accompanied by adverse effects and may not be effective for all patient subtypes, particularly atrophic AMD. The development of P2X7R antagonists, including selective small molecules and blocking antibodies, presents new therapeutic opportunities. Continued research is crucial to elucidate the mechanisms of P2X7R in retinal diseases, enhancing our understanding of its protective effects and guiding the development of more effective treatment strategies.

Min Wen

graduated with a Master’s degree in Ophthalmology from Zunyi Medical University in 2025. Her research primarily focuses on the role of purine metabolism in ophthalmology, with a specific interest in the molecular mechanisms underlying retinal diseases. Her studies explore the impact of purine-related pathways on retinal cell function and its potential therapeutic implications. After completing her master’s degree, she intends to continue her research in ocular health, aiming to further the understanding of purine metabolism in eye diseases and contribute to the development of novel treatment approaches.

Author contributions

MW and SH wrote the main manuscript text and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Muchuchuti S, Viriri S (2023) Retinal disease detection using deep learning techniques: a comprehensive review. J Imaging 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Tan TE, Wong TY (2022) Diabetic retinopathy: looking forward to 2030. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 13:1077669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang JM, Tanna AP (2021) Glaucoma. Med Clin North Am 105:493–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleckenstein M, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Chakravarthy U (2024) Age-related macular degeneration: a review Jama 331:147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuzic M, Rojo Arias JE, S.G. Wohl SG et al. (2019) Retinal miRNA functions in health and disease. Genes 10:377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Drysdale C, Park K, Vessey KA et al (2022) P2X7-mediated alteration of membrane fluidity is associated with the late stages of age-related macular degeneration. Purinergic Signal 18:469–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pavlou S, Augustine J, Cunning R et al. (2019) Attenuating diabetic vascular and neuronal defects by targeting P2rx7. Int J Mol Sci 20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Ventura ALM, Dos Santos-Rodrigues A, Mitchell CH et al (2019) Purinergic signaling in the retina: from development to disease. Brain Res Bull 151:92–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vessey KA, Fletcher EL (2012) Rod and cone pathway signalling is altered in the P2X7 receptor knock out mouse. PLoS ONE 7:e29990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Notomi S, Hisatomi T, Kanemaru T et al (2011) Critical involvement of extracellular ATP acting on P2RX7 purinergic receptors in photoreceptor cell death. Am J Pathol 179:2798–2809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reichenbach A, Bringmann A (2016) Role of purines in Müller Glia. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 32:518–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L, Liu J, Xu A et al (2021) Expression of purinergic receptors on microglia in the animal model of choroidal neovascularisation. Sci Rep 11:12389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campagno KE, Sripinun P, See LP et al. (2024) Increased Pan-type, A1-type, and A2-type astrocyte activation and upstream inflammatory markers are induced by the P2X7 receptor. Int J Mol Sci 25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Fletcher EL, Wang AY, Jobling AI et al (2019) Targeting P2X7 receptors as a means for treating retinal disease. Drug Discov Today 24:1598–1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Díaz-Coránguez M, Ramos C, Antonetti DA (2017) The inner blood-retinal barrier: cellular basis and development. Vision Res 139:123–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ge X, Zhu X, Liu W et al (2025) cGAMP promotes inner blood-retinal barrier breakdown through P2RX7-mediated transportation into microglia. J Neuroinflammation 22:58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawamura H, Sugiyama T, Wu DM et al (2003) ATP: a vasoactive signal in the pericyte-containing microvasculature of the rat retina. J Physiol 551:787–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugiyama T, Kawamura H, Yamanishi S et al (2005) Regulation of P2X7-induced pore formation and cell death in pericyte-containing retinal microvessels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288:C568-576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugiyama T, Kobayashi M, Kawamura H et al (2004) Enhancement of P2X(7)-induced pore formation and apoptosis: an early effect of diabetes on the retinal microvasculature. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45:1026–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shibata M, Ishizaki E, Zhang T et al. (2018) Purinergic vasotoxicity: role of the pore/oxidant/K(ATP) channel/Ca(2+) pathway in P2X(7)-induced cell death in retinal capillaries. Vision (Basel) 2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Xu H, Liang SD (2013) Effect of P2X7 receptor on inflammatory diseases and its mechanism. Sheng Li Xue Bao 65:244–252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Platania CBM, Lazzara F, Fidilio A et al (2019) Blood-retinal barrier protection against high glucose damage: The role of P2X7 receptor. Biochem Pharmacol 168:249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fresta CG, Caruso G, Fidilio A et al. (2020) Dihydrotanshinone, a natural diterpenoid, preserves blood-retinal barrier integrity via P2X7 receptor. Int J Mol Sci 21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Cerani A, Tetreault N, Menard C et al (2013) Neuron-derived semaphorin 3A is an early inducer of vascular permeability in diabetic retinopathy via neuropilin-1. Cell Metab 18:505–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE et al. (1998) The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy: XVII. The 14-year incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy and associated risk factors in type 1 diabetes. Ophthalmol 105:1801–1815 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Franceschini A, Capece M, Chiozzi P et al (2015) The P2X7 receptor directly interacts with the NLRP3 inflammasome scaffold protein. Faseb j 29:2450–2461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu L, Jiang Y, Steinle JJ (2022) Epac1 and PKA regulate of P2X7 and NLRP3 inflammasome proteins in the retinal vasculature. Exp Eye Res 218:108987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelegrin P (2021) P2X7 receptor and the NLRP3 inflammasome: partners in crime. Biochem Pharmacol 187:114385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen H, Zhang X, Liao N et al (2018) Enhanced expression of NLRP3 inflammasome-related inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 59:978–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng X, Wan J, Tan G (2023) The mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome/pyroptosis activation and their role in diabetic retinopathy. Front Immunol 14:1151185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaczmarek E (2010) Nucleotides and novel signaling pathways in endothelial cells: possible roles in angiogenesis, endothelial dysfunction and diabetes mellitus. Springer, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA (2014) The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA 311:1901–1911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang AY, Lee PY, Bui BV et al (2020) Potential mechanisms of retinal ganglion cell type-specific vulnerability in glaucoma. Clin Exp Optom 103:562–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skaper SD, Debetto P, Giusti P (2010) The P2X7 purinergic receptor: from physiology to neurological disorders. Faseb j 24:337–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weisman GA, Camden JM, Peterson TS et al (2012) P2 receptors for extracellular nucleotides in the central nervous system: role of P2X7 and P2Y₂ receptor interactions in neuroinflammation. Mol Neurobiol 46:96–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Catanzaro JM, Hueston CM, Deak MM et al (2014) The impact of the P2X7 receptor antagonist A-804598 on neuroimmune and behavioral consequences of stress. Behav Pharmacol 25:582–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Almasieh M, Wilson AM, Morquette B et al (2012) The molecular basis of retinal ganglion cell death in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res 31:152–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia J, Lim JC, Lu W et al (2012) Neurons respond directly to mechanical deformation with pannexin-mediated ATP release and autostimulation of P2X7 receptors. J Physiol 590:2285–2304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu H, Lu W, Zhang M et al (2010) Stimulation of the P2X7 receptor kills rat retinal ganglion cells in vivo. Exp Eye Res 91:425–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niyadurupola N, Sidaway P, Ma N et al (2013) P2X7 receptor activation mediates retinal ganglion cell death in a human retina model of ischemic neurodegeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54:2163–2170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugiyama T, Lee SY, Horie T et al (2013) P2X₇ receptor activation may be involved in neuronal loss in the retinal ganglion cell layer after acute elevation of intraocular pressure in rats. Mol Vis 19:2080–2091 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bringmann A, Iandiev I, Pannicke T et al (2009) Cellular signaling and factors involved in Müller cell gliosis: neuroprotective and detrimental effects. Prog Retin Eye Res 28:423–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cuenca N, Fernández-Sánchez L, Campello L et al (2014) Cellular responses following retinal injuries and therapeutic approaches for neurodegenerative diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res 43:17–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silverman SM, Wong WT (2018) Microglia in the retina: roles in development, maturity, and disease. Annu Rev Vis Sci 4:45–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Au NPB, Ma CHE (2022) Neuroinflammation, microglia and implications for retinal ganglion cell survival and axon regeneration in traumatic optic neuropathy. Front Immunol 13:860070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, Xu Y, Sun Q et al (2019) Activation of P2X(7)R- NLRP3 pathway in retinal microglia contribute to retinal ganglion cells death in chronic ocular hypertension (COH). Exp Eye Res 188:107771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chong RS, Martin KR (2015) Glial cell interactions and glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 26:73–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao X, Sun R, Luo X et al (2021) The interaction between microglia and macroglia in glaucoma. Front Neurosci 15:610788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang M, Wong WT (2014) Microglia-Müller cell interactions in the retina. Adv Exp Med Biol 801:333–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu H, Nie D, Fang M et al (2024) Müller cells under hydrostatic pressure modulate retinal cell survival via TRPV1/PLCγ1 complex-mediated calcium influx in experimental glaucoma. Febs j 291:2703–2714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu MX, Zhao GL, Hu X et al (2022) P2X7/P2X4 receptors mediate proliferation and migration of retinal microglia in experimental glaucoma in mice. Neurosci Bull 38:901–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wei M, Zhang G, Huang Z et al (2023) ATP-P2X(7)R-mediated microglia senescence aggravates retinal ganglion cell injury in chronic ocular hypertension. J Neuroinflammation 20:180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsutsumi T, Iwao K, Hayashi H et al (2016) Potential neuroprotective effects of an LSD1 inhibitor in retinal ganglion cells via p38 MAPK activity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 57:6461–6473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pfeiffer ZA, Guerra AN, Hill LM et al (2007) Nucleotide receptor signaling in murine macrophages is linked to reactive oxygen species generation. Free Radic Biol Med 42:1506–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang QL, Wang W, Jiang Y et al (2018) GRGM-13 comprising 13 plant and animal products, inhibited oxidative stress induced apoptosis in retinal ganglion cells by inhibiting P2RX7/p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 101:494–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perez de Lara MJ, Aviles-Trigueros M, Guzman-Aranguez A et al (2019) Potential role of P2X7 receptor in neurodegenerative processes in a murine model of glaucoma. Brain Res Bull 150:61–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu Y, Li SY, Zhang LJ et al (2024) Neuroprotection of the P2X7 receptor antagonist A740003 on retinal ganglion cells in experimental glaucoma. NeuroReport 35:822–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dong L, Hu Y, Zhou L et al (2018) P2X7 receptor antagonist protects retinal ganglion cells by inhibiting microglial activation in a rat chronic ocular hypertension model. Mol Med Rep 17:2289–2296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kong H, Zhao H, Chen T et al (2022) Targeted P2X7/NLRP3 signaling pathway against inflammation, apoptosis, and pyroptosis of retinal endothelial cells in diabetic retinopathy. Cell Death Dis 13:336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheng X, Gao H, Tao Z et al (2023) Repopulated retinal microglia promote Müller glia reprogramming and preserve visual function in retinal degenerative mice. Theranostics 13:1698–1715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sappington RM, Chan M, Calkins DJ (2006) Interleukin-6 protects retinal ganglion cells from pressure-induced death. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47:2932–2942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lim JC, Lu W, Beckel JM et al (2016) Neuronal release of cytokine IL-3 triggered by mechanosensitive autostimulation of the P2X7 receptor is neuroprotective. Front Cell Neurosci 10:270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ortega F, Pérez-Sen R, Delicado EG et al (2009) P2X7 nucleotide receptor is coupled to GSK-3 inhibition and neuroprotection in cerebellar granule neurons. Neurotox Res 15:193–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bindra CS, Jaggi AS, Singh N (2014) Role of P2X7 purinoceptors in neuroprotective mechanism of ischemic postconditioning in mice. Mol Cell Biochem 390:161–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang AYM, Wong VHY, Lee PY et al (2021) Retinal ganglion cell dysfunction in mice following acute intraocular pressure is exacerbated by P2X7 receptor knockout. Sci Rep 11:4184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu Z, Guymer RH (2020) Can the onset of atrophic age-related macular degeneration be an acceptable endpoint for preventative trials? Ophthalmologica 243:399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dechelle-Marquet PA, Guillonneau X, Sennlaub F et al (2023) P2X7-dependent immune pathways in retinal diseases. Neuropharmacology 223:109332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Olivier E, Rat P (2024) Role of oxysterols in ocular degeneration mechanisms and involvement of P2X7 receptor. Adv Exp Med Biol 1440:277–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ohno-Matsui K (2011) Parallel findings in age-related macular degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 30:217–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Narendran S, Pereira F, Yerramothu P et al (2021) Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and Kamuvudines inhibit amyloid-beta induced retinal pigmented epithelium degeneration. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6:149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kerur N, Hirano Y, Tarallo V et al (2013) TLR-independent and P2X7-dependent signaling mediate Alu RNA-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in geographic atrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54:7395–7401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Geerlings MJ, de Jong EK, den Hollander AI (2017) The complement system in age-related macular degeneration: a review of rare genetic variants and implications for personalized treatment. Mol Immunol 84:65–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aredo B, Li T, Chen X et al (2015) A chimeric Cfh transgene leads to increased retinal oxidative stress, inflammation, and accumulation of activated subretinal microglia in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56:3427–3440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gu BJ, Wiley JS (2018) P2X7 as a scavenger receptor for innate phagocytosis in the brain. Br J Pharmacol 175:4195–4208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vessey KA, Gu BJ, Jobling AI et al (2017) Loss of function of P2X7 receptor scavenger activity in aging mice: a novel model for investigating the early pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Pathol 187:1670–1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhuang C, Pannecouque C, De Clercq E et al (2020) Development of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs): our past twenty years. Acta Pharm Sin B 10:961–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.De Cecco M, Ito T, Petrashen AP et al (2019) L1 drives IFN in senescent cells and promotes age-associated inflammation. Nature 566:73–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vallés-Saiz L, Ávila J, Hernández F (2023) Lamivudine (3TC), a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, prevents the neuropathological alterations present in mutant tau transgenic mice. Int J Mol Sci 24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Wong KY, Phan CM, Chan YT et al (2024) A review of using traditional chinese medicine in the management of glaucoma and cataract. Clin Exp Optom 107:156–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yin S, Wang ZF, Duan JG et al (2015) Extraction (DSX) from Erigeron breviscapus modulates outward potassium currents in rat retinal ganglion cells. Int J Ophthalmol 8:1101–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chao HM, Hu L, Cheng JM et al (2016) Chi-Ju-Di-Huang-Wan protects rats against retinal ischemia by downregulating matrix metalloproteinase-9 and inhibiting p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Chin Med 11:39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Woo KM, Mahrous MA, D’Amico DJ et al (2024) Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in patients with chronic exposure to P2X7R inhibitors. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 262:3493–3499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Karasawa A, Kawate T (2016) Structural basis for subtype-specific inhibition of the P2X7 receptor. Elife 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Campagno KE, Lu W, Jassim AH et al (2021) Rapid morphologic changes to microglial cells and upregulation of mixed microglial activation state markers induced by P2X7 receptor stimulation and increased intraocular pressure. J Neuroinflammation 18:217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shao X, Guha S, Lu W, et al. (2020) Polarized cytokine release triggered by P2X7 receptor from retinal pigmented epithelial cells dependent on calcium influx. Cells 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Clapp C, Diaz-Lezama N, Adan-Castro E et al (2019) Pharmacological blockade of the P2X7 receptor reverses retinal damage in a rat model of type 1 diabetes. Acta Diabetol 56:1031–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gallo RA, Qureshi F, Strong TA et al (2022) Derivation and characterization of murine and amphibian Muller glia cell lines. Transl Vis Sci Technol 11:4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mancini JE, Ortiz G, Potilinstki C et al (2018) Possible neuroprotective role of P2X2 in the retina of diabetic rats. Diabetol Metab Syndr 10:31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.