Abstract

Long-lasting stability of the anticoagulant coating on centrifugal blood pumps (CBPs) is of vital importance to ensure the hemocompatibility of the blood circulation system therein. Heparin coatings are often prepared using static wet chemical technique, but these face risks of delamination or deactivation induced by blood flow. Inspired by the flow-shear-stress mediated conformation changes of von Willebrand factor, a novel fluid-driven deposition technique was employed to apply polydopamine-heparin coatings within CBPs. Moreover, most FDA-approved CBPs are designed for high-flow-rate CBPs of major organs like the heart and lungs (1000∼8000 ml/min). Few are tailored for low-flow-rate perfusion of other organs such as the liver, kidney and brain (<50–300 mL/min). Our approach addresses this gap by developing low-flow-rate CBPs through anti-thrombogenic coatings and anti-hemolytic structural optimizations. In this study, we introduced an axial magnetic direct drive motor with our optimized low-flow-rate CBPs, achieving a stable-low-flow-rate rate ranging from 16.3 mL/min (300 rpm) to 121.0 mL/min (2000 rpm). The resulting CBPs system exhibited enhanced flow stability and hemocompatibility in rabbit model experiments, demonstrating significantly lower hemolysis rates and lower thrombus formation risks. These results indicate that the polydopamine-assisted heparin coating provides short-term stability under dynamic flow, offering a promising strategy for low-flow-rate CBPs, though its long-term durability and clinical translation potential require further validation.

Keywords: Heparin coatings, Flow-induced deposition, Magnetic-driven centrifugal blood pump, Hemocompatible, Anticoagulant

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Shear flow enables stable, dense polydopamine-heparin deposition on pump surfaces.

-

•

CFD-guided impeller/gap design minimizes hemolysis risk (HI = 0.78 %) and thrombosis.

-

•

Enables stable low-flow perfusion (16–121 mL/min) for small organs.

-

•

Coated pump significantly reduced thrombus formation and hemolysis in rabbit models.

-

•

Addresses critical gap for brain/kidney/liver support circuits.

1. Introduction

Centrifugal blood pumps (CBPs), as a critical component in extracorporeal mechanical circulation perfusion (EMCP), are primarily designed for wide-range flow rates and long-term use. Long-lasting stability of the anticoagulant coating is of vital importance to ensure the safety of blood-circulation related device with different blood flow ranges, such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for the adult heart (1000–8000 mL/min) [1,2], extracorporeal CO2 removal (500–2000 mL/min) [3,4], continuous kidney replacement therapy (100–300 mL/min) [5,6], hypothermic machine perfusion in liver transplantation (<50 mL/min) [7] and intra-arterial selective cooling infusion for brain injury (<50 mL/min) [8]. Among these blood circulation systems, anti-coagulant coatings must be securely anchored and mechanically durable to withstand continuous wear or delamination caused by blood flow, and hydrodynamic stability is a vital factor to maintain the hemocompatibility of the devices.

Heparin-coated blood-contact medical devices have been clinically used for over three decades [9]. Most of those coatings are prepared by layer-by-layer, dip-coating or chemical grafting technique which are unstable under dynamic flow and shear conditions, particularly during the transition from laminar to turbulent flow [10]. Studies indicate that the erosion rate of coatings is accelerated in dynamic fluid environments [11] compared to static ones [12], with shear stress from fluid flow further influencing this process [13]. Therefore, an ideal coating technique to surface functionalize those devises must not only counteract coagulation factors but also withstand the shear stress induced by different flow rates [14,15].

A bioinspired flow-induced coating deposition approach was proposed recently [16]. Von Willebrand factor (VWF) functions as a mechanical sensor, triggering platelet plug formation in response to bleeding but remaining inactive in normal circulation. In a static state, VWF molecules are tightly packed within concatemeric chains, adopting a coiled conformation. Shear flow is theorized to induce polymer tumbling, causing VWF to alternate between extended and contracted states, with the extent of extension increasing with shear rate [17,18]. The fluid-driven, in-situ polymer layer-by-layer self-assembly technique was developed. The flow-induced shear force effectively extends polymer chains, enhancing the exposure of binding sites, thereby improving the adhesion and organization of adsorbed macromolecules [16,19]. Moreover, studies demonstrate that leveraging the bio-adhesive properties of polydopamine enhances the coating's resistance to fluid shear stress [20]. Under high shear conditions, the rate of dopamine self-polymerization accelerates, leading to enhanced coating thickness and improved adhesion to the substrate [21].

Inspired by the fluid-driven in-situ polymer layer-by-layer self-assembly technique, a polydopamine-grafted-heparin coating was prepared on CBP using a flow-induced deposition approach and compared with the conventional static dip-coating technique. As for CBP, the flow field distribution within the pump head influences coating stability. Most FDA-approved CBPs are designed primarily for targeting major organs like the heart and lungs defined as high-flow-rate [22]. Few devices are optimized for low-flow-rate perfusion in smaller organs such as the kidney, liver, and brain defined as low-flow-rate. Our approach addresses this gap by developing specialized low-flow-rate CBP systems involved two key strategies: anti-thrombogenic surface coatings and anti-hemolysis structural optimization.

A bioinspired flow-induced deposition technique was used to prepare polydopamine-heparin coatings on a structurally optimized blood pump. Optimized coating parameters were determined using a customized flow device. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) was employed to optimize the pump head structure, and the hemolysis index (HI) estimation model was used for verification. The optimal pump design was fabricated using 3D printing technology, and the pump was surface-functionalized with a polydopamine-grafted heparin coating through a fluid-driven technique. The primary innovation of this work lies in the integration of these two strategies, where the flow-driven coating process represents the core advancement to improve long-term anticoagulant stability under physiological shear forces, while the structural optimization ensures hemcompatible low-flow-rate performance. This study provides a specialized magnetic-driven centrifugal blood pump that is more effective for treating multi-organ diseases in conjunction with extracorporeal auto-blood circulation techniques.

2. Results

2.1. Study design of surface-functionalization on CBPs and molecular dynamics simulation

We developed a versatile mechanical circulatory perfusion system (Fig. 1A) for multi-organ applications, comprising a flexible polyvinyl chloride tube, tube connectors, and an oxygenated heat exchanger. A monitoring module was designed for circulation monitoring. In the present prototype, an in-line flow sensor was implemented (Fig. 5A), while pressure and temperature sensors are reserved for subsequent system iterations. Among them, the hemocompatibility of blood pump is of vital importance. Traditional coatings (Fig. 1B) are often prepared using static wet chemical techniques, leading to random distribution of anticoagulant polymers (e.g., heparin sodium). Under high flow rates and prolonged shear forces, these coatings are unstable. Fluid-driven conditions, however, fully stretch molecular chains, exposing more active sites and enhancing coating adhesion [[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]].

Fig. 1.

Illustrations of the Mechanical Circulatory Perfusion System. (A) Centrifugal Blood Pumps: CBPs for the mechanical circulatory perfusion system capable of handling different blood flows. (B) Coating Comparison: Comparison of coatings prepared under static versus flow-driven conditions. (C) Molecular dynamics simulation: the conformation of the interaction between heparin and dopamine molecule under different times (for heparin: pink-O, cyan-N; for dopamine: red-O, blue-N; for heparin/dopamine: yellow-C; khaki-SiO2 substrate). (D) Dynamic parameters: (a) the radius of gyration (Rg), (b) numbers of H-bonds, and (c) interaction energies of the heparin/dopamine molecules with and without flow field. Design Rationale: Highlighting the rationale for the miniaturized, hemocompatible, and anticoagulant design of CBPs.

Fig. 5.

Animal Experiment Validation. (A) Rabbit Experiments: Schematics of the rabbit experiments, and illustrations of the animal study (B). (C) Blood Pumps: (a) the uncoated and coated pump heads. (b) Photos of the coated and uncoated pump heads after the animal study with SEM images, and illustrations of the corresponding blood clots. (D) Residual Thrombus: the coated (flow-induced coating and dip-induced coating) and uncoated pump heads that being 3D printed according to computational model of LivaNova® pump. (E) Hemocompatibility: measurement the rabbit's Prothrombin Time (PT), Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT), and Thrombin Time (TT) by the flow-induced coating, dip-induced coating and uncoated.

Molecular dynamics simulation is conducted to confirm this conjecture, which is an important method for studying the stability and kinetic characteristics of polymers in aqueous solutions. The simulated trajectories of the heparin and dopamine was evaluated by built-in module in Gromacs. According the snapshot of molecule conformations within 60 ns simulation, the heparin/dopamine polymer is much more stretched in flow field (Fig. 1C).

The aggregation level of the polymers was quantitively analyzed by Rg (radius of gyration) values, with larger Rg indicating higher levels of aggregation. In the 60 ns simulation, the overall Rg values of heparin/dopamine molecule aggregates in system with flow were higher than that without flow (Fig. 1D–a). From Rg, the presence of the flow field suppresses the aggregation of heparin and dopamine molecules (Fig. 1C). In addition, we found that the numerical fluctuations in system under flow were significant, which might be due to the presence of the flow field, where the flow and erosion of water molecules intensify molecular motion, resulting in significant fluctuations in the degree of aggregation. These results suggest that the presence of a flow field restrains molecular curling. The number of hydrogen bonds formed between the two molecules in system with flow was lower than that without flow (Fig. 1D–b), and this also indicated that the flow of water molecules to a certain extent destroyed the hydrogen bond formed between the two molecules. Although the MD simulation indicated a reduction in the number of hydrogen bonds under shear flow, coating adhesion was not solely governed by hydrogen bonding. The shear field facilitated molecular rearrangement and chain extension, promoting stronger π–π stacking, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces between polydopamine and heparin molecules, as well as between the coating and the substrate. These noncovalent interactions collectively compensated for the loss of hydrogen bonds and contributed to an overall enhancement in coating adhesion and stability under flow conditions. The numerical difference in the interaction energy between the two systems was relatively small, and from the trend, there was a slight sharp increase in the absolute value of the interaction energy of system with flow in the latter half of the simulation (Fig. 1D–c). Combining with the simulation snapshot, it was mainly due to the settlement of all molecules in system under flow field from the solution to the substrate, resulting in a decrease in intermolecular distance and an increase in the absolute value of the value. Therefore, under flow-induced shear stress, sodium heparin molecular chains fully extend, resulting in less clumpy agglomeration and a more orderly arrangement. Thus, the fluid-driven preparation method significantly improves the surface morphology and structural density of the sodium heparin anticoagulant coating compared to traditional methods.

2.2. Coatings preparation and microstructural analysis

The coating performance depends on the concentrations of the components and the flow velocity. A trial-and-error experiment was conducted using a customized circulation device, which includes a flow sensor, a roller pump, a Y connector, and a reaction slot (Fig. 2A). To ensure uniformity in the flow-induced deposition, the flow velocity and wall shear stress distribution across the silicon wafer surface were evaluated (Fig. 2B) to prevent vortex formation. The underlying mechanism for the differences in coating morphology was explored through dissipative molecular dynamics simulations (Fig. 2C). A coarse-grained model featured polydopamine (orange molecule) on monocrystalline silicon (green molecule), with the substrate immersed in a solution of randomly distributed sodium heparin molecules. In a static environment, sodium heparin molecules adsorb onto the substrate randomly via Coulomb and van der Waals interactions, leading to aggregated molecular chains and clumps. Conversely, under flow-induced shear stress, sodium heparin molecular chains fully extend, resulting in less clumpy agglomeration and a more orderly arrangement. Thus, the fluid-driven preparation method significantly improves the surface morphology and structural density of the sodium heparin anticoagulant coating compared to traditional methods.

Fig. 2.

Coatings Preparation and Characterization. (A) Illustration of Customized Circulation Device: includes a flow sensor, a roller pump, a Y connector, and a reaction slot. (B) Fluid dynamics analysis: the velocity and shear stress field distribution within the reaction slot. (C) Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Primary and three-dimensional views of the dissipative molecular dynamics simulation illustrating the molecular stacking and arrangement. (D) XPS Spectra: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra showing the elemental composition of the silicon wafer, flow-induced deposition coatings, and static dip coatings. (E) High-resolution XPS spectra of N 1s; Complete FTIR Spectra: (F) Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra representing the full spectral range of the silicon wafer, flow-induced deposition coatings, and static dip coatings. (G) Water Contact Angles; (H) AFM Micrographs: Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of the coatings before and after 30 and 60 min of infusion. (I) And the quantitative assessment of surface roughness changes in the coatings post-infusion; and the related surface roughness changes. (J) Surface Morphology: SEM imaging of flow-induced deposition coatings and static dip coatings post-infusion. (K) HUVEC Adhesion Imaging: Fluorescence imaging depicting human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) adhesion on flow-induced deposition coatings and static dip coatings before and after 30 and 60 min of infusion. (L) Platelet Adhesion Imaging: Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images showing platelet adhesion on flow-induced deposition and static dip coatings after 60 min of infusion.

Chemical characterization of the flow-induced deposition and static dip coatings was conducted using XPS (Fig. 2D) and FTIR (Fig. 2F). XPS spectra revealed the presence of sulfur and nitrogen in both coatings, with higher sulfur content in the flow-induced deposition coatings. High-resolution N 1s spectra (Fig. 2E) demonstrate strong electrostatic interactions between SO3−/COO− anions on the heparin molecular chain and protonated amine C-NH3+/C-N+ in dopamine, enabling effective anchoring of sodium heparin through multiple points on the polydopamine, thus enhancing the binding force. The binding energy of the flow-induced deposition coatings was higher than that of the static dip coatings, indicating a stronger binding force. FTIR spectra (Fig. 2F) show a peak at approximately 1238 cm−1 (S=O), confirming successful heparin grafting. Water contact angle data (Fig. 2G) indicate significant hydrophilicity for the polydopamine/heparin coatings, with the static dip coatings exhibiting even greater hydrophilicity, likely due to a higher grafting density of heparin molecules in a static environment.

2.3. Coatings stability evaluation

The stability of the coatings was assessed by subjecting them to a circulating flow of 75 mL/min for 30 and 60 min. As shown in Fig. 2H and I, the surface morphology of the coatings created by fluid-driven methods exhibited minimal changes, with the height difference varying from 21.5 nm to 23 nm. In contrast, the static dip coatings showed a notable reduction in height (from 30.3 nm to 25.7 nm) and roughness (Rq decreased from 3.9 nm to 3.0 nm), along with the formation of large agglomerates and more pronounced concave areas after flushing (Fig. 2J). Consequently, the coatings prepared by fluid-driven methods demonstrated greater stability, exhibiting smaller changes in height and suggesting reduced heparin loss and potentially enhanced anticoagulant effectiveness. The distinct surface morphology between the coatings, consistent with earlier simulation results, can be attributed to the influence of shear flow on polymer conformation. Research suggests that hydrodynamic interactions in polymer solutions, which can lead to agglomeration, are mitigated by stretching [23]. Furthermore, shear flow can facilitate the coil-stretch transition macromolecules [24] and increase the polymer adsorption rate [25], thereby reducing agglomerations in a flow environment.

2.4. In vitro biocompatible evaluation

To evaluate the impact of flow on the biocompatibility of the coatings, HUVECs (CVCL_B7UJ) LIVE/DEAD® assay and platelet adsorption experiments were conducted. The in vitro cell culture study shown in Fig. 2K demonstrates that HUVECs exhibited more uniform and extensive growth on coatings prepared by the flow-induced method, compared to the uneven cell distribution on the static dip coatings. Additionally, due to the superior anticoagulant properties of sodium heparin, no platelets adhered to the flow-induced deposition coating. It should be noted that while Fig. 2k demonstrates enhanced endothelial cell adhesion on the coated surface, this result primarily serves as an in vitro indicator of biocompatibility rather than a direct prediction of in vivo tissue overgrowth. In the context of rotating blood pump components, excessive cellular adhesion could indeed pose a risk to long-term stability and safety. Therefore, future studies will focus on evaluating coating performance under prolonged dynamic shear conditions, particularly assessing whether the coating promotes undesirable tissue proliferation on rotating surfaces. This additional verification will be critical to confirm the long-term security of the device. In contrast, the static dip coatings that were flushed for 60 min experienced regional shedding (indicated by the dark areas), leading to platelet attachment and significantly impairing their long-term anticoagulant effectiveness (Fig. 2L).

2.5. Hydrodynamics-derived structural optimizations of the pump head

Commercially available CBPs exhibit extensive velocity field distributions, with high and low velocity regions increasing the risk of shear-induced hemolysis and stagnant-induced thrombosis, respectively. Optimizing the structural design of the CBP head is essential to minimize hemolysis and reduce eddy currents, thereby preventing the formation of blood stasis zones [26]. The anti-hemolysis design, achieved through structural optimization of CBP components (including size, blade configuration, and gaps), aims to mitigate hemolysis by controlling shear stress and exposure time within safe thresholds for red blood cells [4]. This can result in hazardous outcomes, including abnormal platelet function, increased circulatory resistance, renal failure, and multi-organ dysfunction [27].

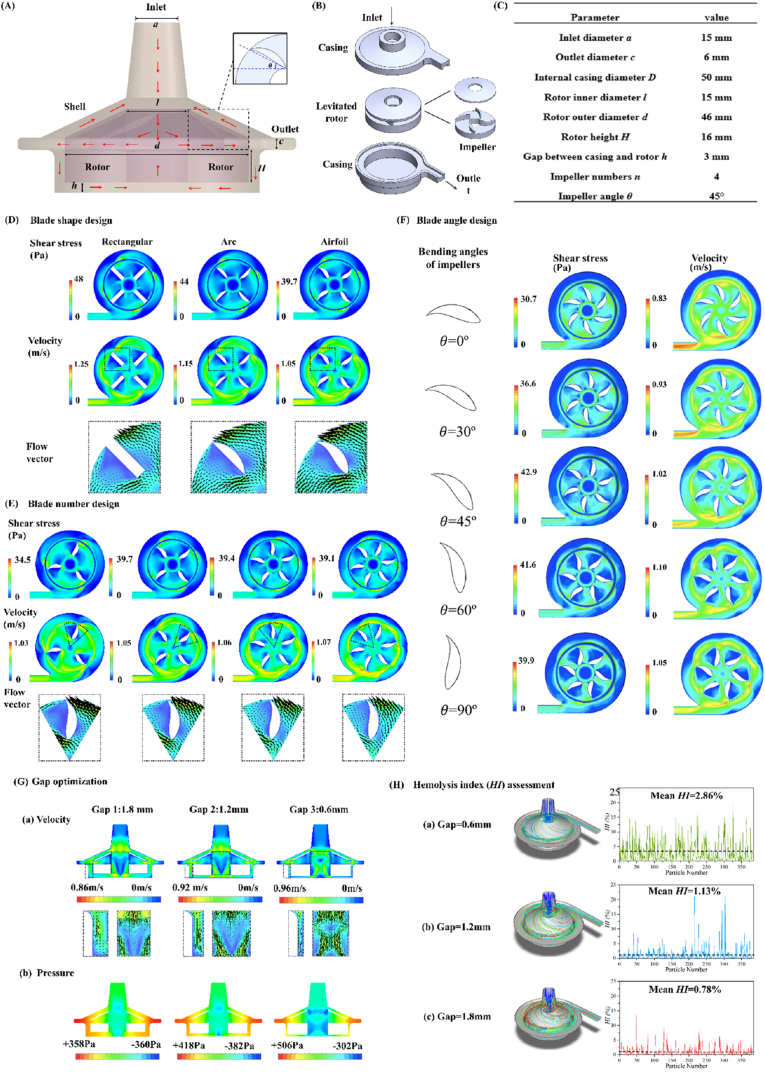

Fig. 3A presents a schematic of the centrifugal blood pump (CBP) and its internal flow, while the geometric parameters of the baseline model are summarized in Fig. 3C. The CBP consists of a rotor with an integrated airfoil impeller and a stationary casing, with the rotor levitated and driven within the casing by the stator's magnetic force (Fig. 3B). Three-dimensional (3D) modeling was performed using SolidWorks (Dassault Systèmes SolidWorks Co., Waltham, MA, USA). Key geometric parameters, including blade shape, number, bending angle, and the gap between casing and rotor, were systematically optimized to achieve stable flow and a reduced hemolysis index (HI), which indirectly reflects the risk of red blood cell damage.

Fig. 3.

Structural Optimization of the Pump Head. (A) Schematic Overview: Schematic representation of the continuous blood pump (CBP) with its internal flow (red arrows) and the geometric and structural diagram of the baseline model impeller (dash frame). (B) Components: Components of the CBP's shell, including casings, the levitated rotor, and impellers. (C) The Baseline Model: the geometric parameters of the baseline model. (D) Impeller Shape Effects: Shear stress, velocity, and streamline for various impeller shapes as determined by CFD simulation at 1000 rpm. (E) Impeller Number Effects: CFD simulation of the shear stress, velocity, and streamline for different numbers of impellers (1000 rpm). (F) Impeller Angle Effects: CFD simulation of the shear stress, velocity, and streamline for varying bending angles of impellers (1000 rpm). (G) Rotor-Casing Gap Effects: Velocity and pressure profiles for different gaps between the casing and rotor in the blood pump's cross-sectional view (1000 rpm). (H) Hemolysis Index (HI): Hemolysis index for various gaps between the rotor and casing at 1000 rpm.

Among different impeller configurations, the rotor equipped with an airfoil impeller exhibited the lowest shear stress and consequently minimized hemolysis risk compared with rectangular and arc-shaped designs (Fig. 3D). Although traces of blood residue were observed on the upper surface of the blades, this is likely attributable to localized recirculation and boundary layer effects, as well as minor deviations introduced during 3D printing and assembly. These factors can create small stagnation zones but do not indicate significant bulk flow through the closed impeller surface. Future refinements of fabrication accuracy and gap design are expected to further reduce this phenomenon.

As shown in Fig. 3E, CBPs with 3, 4, 5, and 6 airfoil blades were analyzed with respect to shear, velocity, and streamline distributions at a rotation speed of 1000 rpm. The 3-blade design produced the lowest shear stress but exhibited the largest eddy zones. In contrast, pumps with 4–6 blades demonstrated comparable shear levels, but the eddy zones decreased progressively as the blade number increased, particularly under low-flow-rate conditions.

The effect of impeller bending angle was further evaluated using CFD simulations at 1000 rpm, with angles set at 0°, 30°, 45°, 60°, and 90° (Fig. 3F). The 45° impeller produced the highest shear stress, whereas the 0° impeller generated the lowest shear stress and exhibited minimal eddy formation. Significant recirculation was observed in the 60° and 90° designs, while the 0° design nearly eliminated eddy zones. Based on these findings, an impeller with six airfoil blades and a 0° bending angle was selected to balance shear reduction and flow stability. Careful selection of both blade number and angle is essential to avoid abrupt geometric transitions along the blade streamline, thereby minimizing turbulence, reducing hemolysis risk, and ensuring stable hemodynamics within the CBP [28].

Fig. 3G illustrates the velocity and pressure distributions in the pump at a low-flow-rate rate (1000 rpm) for various gaps between the rotor and casing. The blood pump with a 0.6 mm gap exhibited significantly higher velocity, pressure, and shear ranges, with minimal eddy zones within the rotor. Conversely, a lower range of these hemodynamic characteristics was observed for a 1.8 mm gap. In models with larger gaps, eddy zones formed in the middle of the rotor region due to the lift force and energy dissipation caused by the high-speed rotating blood. The pressure distribution map in Fig. 3G reveals that the maximum pressure (represented in red) within the rotor region is approximately 506 Pa, equivalent to 3.8 mmHg. While this pressure is lower than typical arterial pressures (80–120 mmHg), it represents the internal pressure within the pump head, not the pressure required for organ perfusion. The pressure generated within the pump system is further amplified by the vascular resistance encountered during perfusion. In this study, we demonstrated that the pressure at the selected flow rates (e.g., 50 mL/min) is sufficient to meet the needs of small organ perfusion, achieving a pressure head of approximately 85 mmHg, which aligns with clinical requirements for organ perfusion systems. To determine the optimal gap between the rotor and casing, we analyzed the hemolysis index (HI) to evaluate blood damage risk across designs. As shown in Fig. 3H(a–c), the 1.8 mm gap demonstrated the lowest HI value of 0.78 %, compared to other gap designs. This finding reflects the fundamental trade-off in gap optimization: narrower clearances (e.g., 0.6 mm) generate intense tip-leakage jets and rotor–casing squeeze-film shear, thereby amplifying peak shear and increasing hemolysis, whereas a larger clearance (1.8 mm) reduces peak shear exposure and high-shear volume fraction. At the same time, we recognize that wider gaps may enlarge low-shear recirculation regions and potentially increase stasis-related thrombogenicity. In the present prototype, streamline analysis indicated sufficient washout of the clearance zone under the tested operating conditions, and the anticoagulant coating provided further mitigation of surface-mediated thrombosis. Accordingly, the 1.8 mm gap should be interpreted as a hemolysis-oriented optimization for this proof-of-concept design, rather than a definitive clinical specification. Future iterations will converge the clearance toward clinical values (∼0.3–0.5 mm) while preserving low shear through blade re-profiling, targeted washout paths (e.g., balance holes or purge channels), and tighter machining tolerances, coupled with direct platelet activation and thrombogenicity assays to more comprehensively assess the hemolysis–thrombosis trade-off.

2.6. CBP system construction and animal experiment validation

An axial magnetic direct drive motor was designed to accommodate high speeds (300–2000 rpm) and low flows (16.3–121.0 mL/min), enabling miniaturization and stable rotation while isolating the blood within the pump from the external environment (Fig. 4). Safety and efficiency were evaluated using a customized circulation system connected to the bilateral carotid arteries of a rabbit model, demonstrating significantly reduced hemolysis rates and thrombus formation risks after 120 min of circulation.

Fig. 4.

CBP System Construction and in Vitro Experiment Setup. ( A) Structural Composition: The structural composition of the blood pump motor. (B) Electromagnetic Characteristics: Analysis of the electromagnetic characteristics of the blood pump motor. (C) Flow Rates by Experiments: the pump demonstrated significant stability with fluctuations remaining under ±1.5 mL/min. (D) Schematic Diagram: Schematic representation of the in vitro experiment setup. (E) Physical Subsystems: Photographs of the individual physical subsystems, including the human vascular model, controller, flow meter, and CBP prototype.

The structure of the designed axial magnetic direct drive motor was presented in Fig. 4A with specific consideration for the low flow requirements of a magnetically driven blood pump. The structural composition and electromagnetic characteristics of this motor were analyzed. To construct the pump head section, the volute and accessory elements were integrated with the rotor and the disk motor stator. The rotor permanent magnet was configured in a cross pattern, functioning both as a fixed connection and a rotating driver for the blood pump turbine. The disk motor, serving as the motor's power driving component, was designed to achieve the required blood transfusion function and meet flow and velocity specifications (Fig. 4B). Throughout the experiment, the pump demonstrated significant stability, with fluctuations remaining under ±1.5 mL/min (Fig. 4C). A linear relationship between rotation speed and volume flow rate was observed between 750 and 1750 rpm. The measured flow rates were lower than anticipated due to the resistance provided by the circulation tubes. The flow rates measured in the experiments were lower than those predicted in simulations due to the resistance posed by the circulation tubes. The individual physical subsystems (Fig. 4D), including the human vascular model, controller, flow meter, and CBP prototype (Fig. 4E).

The overall hemocompatibility of the flow-induced-coated and uncoated blood pumps was assessed through a rabbit study as shown in Fig. 5A and B. The images highlight a stark contrast between the anticoagulant-coated pump head on the left and the uncoated one on the right post-experiment. The anticoagulant-coated pump head displays minimal thrombus residue and a light red hue due to blood contamination (Fig. 5C–a). Conversely, the uncoated pump head rotor is dark red with visible blood clots on the blade and center hole. The SEM morphologies of thrombi from uncoated and anticoagulant-coated pump heads are depicted in Fig. 5C–b. The thrombus from the uncoated pump heads resembles natural rabbit blood clots, characterized by a network protein structure formed by platelet extension and linkage with fibrinogen monomers, indicative of blood activation of the contact coagulation mechanism upon exposure to the pump head material. Conversely, the thrombus associated with the anticoagulant-coated pump head exhibits a porous membrane structure, lacking the discernible network protein structure typical of red blood cells, platelets, or fibrin. This difference is attributed to the thrombus sampling location at the rotor base's friction point, yielding a sample composed of cell fragments and blood components abraded by the base.

To validate the effectiveness of the flow-induced coating, a computational model was established according to a commercially available pump samples (LivaNova®) and this model was 3D printed and surface-functionalized by flow-induced coating and dip-induced coating. These findings further indicate the successful application and effective anticoagulant performance of the flow-induced coating on the pump (Fig. 5D).

As shown in Fig. 5E (a-c), compared with the uncoating group, both coating strategies significantly reduced coagulation activation, as evidenced by the markedly shortened PT and APTT values (p < 0.001). Notably, among all groups, the flow-induced coating group exhibited the lowest median PT and APTT values; however, the difference between the two coating strategies was not statistically significant. In terms of TT, although the uncoating group showed a tendency toward prolonged thrombin time, there was no statistically significant difference among the three groups. These data suggest that both coating methods provide comparable blood compatibility, with the flow-induced coating offering potential advantages in terms of uniform surface coverage, reproducibility, and scalability, which may be beneficial for practical applications.

The findings indicate that the surface properties of pump head materials significantly influence coagulation activity during the extracorporeal circulation process. Uncoated materials resulted in markedly prolonged PT and APTT, suggesting widespread activation and potential consumption of coagulation factors through both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. In contrast, both flow-induced coating and dip-induced coating alleviated these effects, with flow-induced coating demonstrating the most pronounced anticoagulant effect, evidenced by the lowest PT and APTT values. This superior performance of flow-induced coating may be attributed to its more uniform and hydrophilic surface characteristics, which minimize protein adsorption, platelet activation, and the initiation of contact pathways. Although TT did not differ significantly among the groups, which is potentially due to assay variability or the relatively late-stage reflection of the coagulation cascade; and the overall trend supports the concept that surface modification enhances blood compatibility. These findings underscore the importance of optimizing the surface of biomaterials, with flow-induced coating emerging as the most effective strategy for maintaining coagulation stability and reducing thrombotic risks in blood-contacting devices. All the samples displayed low hemolysis rates (<5 %).

3. Discussion

This study introduces a special magnetic-driven centrifugal blood pump, characterized by a polydopamine-assisted heparin coating that demonstrated short-term stability under dynamic flow, which proves potentially useful for treating multi-organ diseases in conjunction with the extracorporeal auto-blood circulation technique. The strategies for constructing anticoagulant coatings include biologically inert coatings (such as polyethylene glycol, betaine-based zwitterionic polymers, fluorine-containing slippery surfaces), biologically active coatings (featuring anticoagulants like heparin, fibrinolytic agents such as nitric oxide and fibrinolytic enzymes), pseudo-intimal coatings, and composite anticoagulant coatings. These are primarily prepared through methods such as spraying, impregnation, and chemical grafting.

However, a significant limitation of these functional coatings is their poor stability under liquid shear forces, a high risk of detachment, and the potential deactivation or loss of unstable anticoagulant substances (e.g., heparin sodium). Therefore, designing coatings with enhanced binding strength to the substrate is critical. The manipulation of molecular architecture and related properties under fluid shear forces represents a novel technique [29]. The shear-flow-driven layer-by-layer self-assembly approach accelerates the adsorption rate of macromolecules by mechanically configuring the polymer chain through a coil-stretch transition, which effectively simplifies and hastens the diffusion-controlled assembly process [29]. In the present study, however, the applied shear rate is far below the threshold known to induce shear-unfolding transitions such as those observed for von Willebrand factor, and sodium heparin and polydopamine are not reported to undergo comparable shear-induced conformational changes. In this context, the role of sharing is to enhance mass transfer and improve coating uniformity, rather than alter molecular structures. Additionally, this strategy is applicable to a diverse array of two-dimensional nanofillers, facilitating the creation of high-performance composite materials [30]. Furthermore, polydopamine, known for its versatile binding capabilities on various substrates, was utilized in our coating process.

Nevertheless, the flow-induced coating constructed here relied primarily on dopamine-mediated physical adsorption and self-polymerization to immobilize heparin. While this improved coating uniformity and short-term functional stability, it does not provide covalent endpoint anchoring or multilayer stabilization. Consequently, the long-term retention of anticoagulant activity under continuous flow remains uncertain. Other strategies such as silanization of the substrate, crosslinking chemical treatment, or covalent immobilization of heparin may further enhance durability. Future research should integrate these approaches. Moreover, this study did not quantify the anticoagulant activity of immobilized heparin over time under shear conditions (e.g., anti-Xa activity assays), which will be essential to confirm functional robustness.

In this system, the stable flow rate ranged from 16.3 to 121.0 mL/min as the rotation speed increased from 300 to 2000 rpm. In vitro testing demonstrated that the centrifugal blood pump maintained a stable and reproducible flow rate (64.9 ± 1.1 mL/min at 1250 rpm, maximum error ±1.5 mL/min). This level of stability is advantageous for low-flow-rate organ perfusion applications, where minimizing fluctuations is critical. In contrast, a commercial CBP designed for high-flow-rate ECMO applications showed greater variability under the same low-flow-rate conditions (59 ± 20 mL/min). These results highlight that our design is better tailored to low-flow-rate use cases rather than suggesting superiority in all clinical contexts. At this flow rate, it sufficiently meets the requirements for most small-flow perfusion scenarios. For instance, the perfusion rate for the autologous blood cerebral hypothermic neuroprotective system [31] is approximately 10–50 mL/min, significantly lower than other extracorporeal blood circulation systems, such as the hemodialysis system (200–300 mL/min) and the extracorporeal membrane pulmonary oxygenation system (5000–8000 mL/min).

Low perfusion flow can create blood-retention zones within the system, increasing the risk of coagulation. This study demonstrated that our optimized centrifugal blood pump can deliver stable low-flow-rate rate while generating sufficient pressure head for effective perfusion of small organs, such as the liver and brain. At the same time, CFD simulations and hemolysis index analysis confirmed that the anticoagulation-favorable impeller structure could achieve acceptable hydraulic performance within this clinically relevant low-flow-rate range. While experimental results showed slightly lower flow rates than predicted, due to resistance in the circulation loop, the pump head pressure and stability remained sufficient for organ perfusion. Future work will involve broader hydraulic testing to further verify this balance between hemocompatibility-oriented structural optimization and hydraulic efficiency. The pump's flow-induced deposition method for coating application enhanced the short-term stability of the anticoagulant coating, which is promising for reducing thrombus formation. However, its durability under prolonged continuous flow, protein-rich plasma exposure, sterilization procedures, and long-term storage remains to be validated before clinical translation.

Importantly, the present study compared the flow-induced coating only against static dip-coating, without benchmarking against widely recognized anticoagulant surface technologies such as Carmeda®/C-BAS heparin-bonded coatings, MPC-based phosphorylcholine polymers, or nitric oxide (NO)-releasing surfaces. These systems benefit from extensive clinical validation and established regulatory readiness. Compared with them, our approach offers advantages in simplicity, in-situ applicability, and scalability, but should be regarded as a complementary and exploratory strategy rather than a direct replacement for clinically established coatings. Future benchmarking studies will be necessary to position this technology relative to state-of-the-art systems in terms of anti-thrombogenicity, durability, and translational potential.

The hemolysis performance was determined by the overall design of the blood pump and a suitable gap for the centrifugal pump. Previous studies have shown that the destruction of RBCs correlates with shear stress and contact time in blood flow, as determined through hemolysis experiments [4,32,33]. Utilizing the hemolysis estimation equation (4) and particle tracking in CFD simulation, the shear value and exposure time of all captured particles in the blood flow were quantified based on three different gaps: 0.6 mm, 1.2 mm, and 1.8 mm. Research on radial and axial gaps in high-flow-rate ventricular assist device (VAD) blood pumps suggests that smaller clearances result in lower HI [34,35]. However, some researchers argue that excessively large or small gaps between the casing and rotor can increase blood damage, recommending an optimal gap of approximately 1.5 mm [36].

Blood coagulation, the process in which blood transitions from a flowing liquid state to a non-flowing gel state, begins with platelet activation and the transformation of soluble fibrinogen in plasma into insoluble fibrin [37]. The risk of platelet activation is significantly lower-by a factor of ten-compared to the risk of shear stress-induced red blood cell damage [38]. The degree of coagulation on the blood pump surface can be mitigated through intravenous injection of anticoagulant heparin sodium [39,40] or anticoagulant coatings [41,42]. However, excessive systemic administration of heparin sodium is associated primarily with an increased risk of bleeding complications, which can cause hemodynamic instability and other adverse effects. Therefore, minimizing platelet activation through optimized flow design and surface coatings with validated bioactivity under clinically relevant conditions remains an important future direction. The mathematical relationship of shear force τ in blood circulation devices and flow rate υ is given by Ref. [43]:

| (1) |

where r is the radial coordinate of each particle, ρb is the blood density, f is the friction coefficient of blood within the circulatory device, and R is the radius within these devices. From the formula, it is evident that the shear force τ is approximately linearly related to the flow velocity ui. In a blood pump head, regions of low shear stress can be equated to stagnant blood flow areas. However, in such stagnant zones, blood-compatible coatings are crucial for enhancing the overall hemocompatibility of the devices. These coatings not only improve the flow field within blood circulation instruments but also reduce low shear forces, thus lowering the risk of coagulation. This evaluation method has been employed in existing research on blood pumps.

In our study, the pump was surface-functionalized using a polydopamine-grafted heparin coating applied through a fluid-driven technique. The safety and efficiency of the pump were rigorously tested using a customized circulation system that connected the bilateral carotid arteries of a rabbit model. Compared to the conventional static dip-coating method, the flow-induced coated blood pump demonstrated superior performance in terms of surface roughness and short-term stability. Nevertheless, only preliminary anticoagulation tests were performed, and the long-term bioactivity, reproducibility, and integration into clinically relevant workflows require further investigation before translation.

4. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, due to the motor's size and axial flux design, the maximum rotation speed did not exceed 3000 rpm. The flow rate observed in the experiments was lower than that predicted in simulations, primarily because of resistance and obstructions in the circulation tubing. Second, although the developed flow-driven coating method successfully generated anticoagulant layers with robust adhesion and prolonged activity, its scalability may require higher consumption of coating solutions and anticoagulant agents, as well as specialized circulation equipment. Ensuring fluid stability during large-scale preparation will also be critical to further improve coating quality. Third, only preliminary anticoagulation tests were conducted; the long-term stability of the coating's anticoagulant performance under organ-specific dynamic physiological conditions remains to be fully assessed. Fourth, although CFD simulations and preliminary experiments suggested that the anticoagulation-favorable impeller structure provided acceptable head pressure and flow stability, comprehensive hydraulic characterization, including complete head-flow-rotational speed (H-Q-n) curves under broader operating conditions, is still required for a thorough evaluation of pump performance. Under low flow conditions (<50 mL/min), the use of the Newtonian fluid model systematically underestimates blood flow resistance and overestimates flow velocity, and leads to the calculated values of key blood flow indices such as WSS and OSI deviating from the true values, thereby significantly reducing its accuracy in predicting pathological conditions (such as thrombosis). Fifth, while in vitro experiments demonstrated enhanced endothelial cell adhesion on coated surfaces as an indicator of biocompatibility, the potential risk of excessive tissue adhesion on rotating impeller surfaces was not investigated in this study and will require further long-term in vivo validation to ensure device safety. Sixth, the MD analysis revealed reduced hydrogen-bonding interactions under shear, which appears contradictory to the observed improvement in coating adhesion. This paradox can be explained by the contribution of other noncovalent interactions (π-π stacking, hydrophobic effects, and van der Waals forces) and shear-assisted molecular rearrangements, but a quantitative determination of their relative contributions remains lacking. Seventh, although shear flow was invoked to enhance coating uniformity, the von Willebrand factor (VWF) unfolding analogy is speculative. The shear levels in our CBP are below the pathological thresholds associated with VWF activation, and no shear-induced conformational transition of polydopamine or heparin was identified. Future work will combine CFD-derived wall shear stress mapping with biophysical assays (e.g., QCM-D, SPR, single-molecule force spectroscopy) to determine whether specific coating interactions exhibit shear sensitivity and, if so, to define their thresholds. Eighth, the current coating relies primarily on dopamine-mediated physical adsorption and polymerization, without covalent endpoint anchoring or multilayer stabilization. As such, the retention of heparin activity under continuous long-term flow remains uncertain, and future studies should investigate covalent immobilization strategies (e.g., silanization, crosslinking chemistry) to improve durability. Ninth, this study compared the flow-induced coating only against static dip-coating. Benchmarking against clinically established coatings such as Carmeda®/C-BAS, MPC-based phosphorylcholine coatings, or nitric oxide-releasing surfaces was not performed. Without such direct comparisons, the relative anti-thrombogenicity, durability, and translational readiness of the proposed method remain to be fully determined. Finally, while XPS and FTIR confirmed the successful incorporation of heparin into the coating, these spectroscopic methods alone cannot verify retained anticoagulant activity. Functional validation using anti-Xa and thrombin inhibition assays will therefore be essential in future studies to confirm bioactivity after shear-assisted deposition.

5. Conclusion

This study developed a novel centrifugal pump optimized for low-flow-rate conditions through hydrodynamics-guided multi-parameter structural optimization and surface functionalization. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations demonstrated that impeller parameters significantly influenced the pump's flow field distribution, affecting pressure, flow separation, and shear stress. The pump's hemolysis performance was notably impacted by the gaps between the rotor and shell, achieving the lowest hemolysis index at 0.78 %. Surface modification was performed using a polydopamine-grafted heparin via a flow-driven deposition technique, which showed superior short-term stability and reduced roughness loss compared to the conventional static dip-coating method. The pump's overall blood compatibility was evaluated using a custom circulation system connected to the bilateral carotid arteries of a rabbit model, revealing significantly lower rates of hemolysis and thrombus formation.

6. Materials and methods

6.1. Molecular dynamic simulation

To investigate the interactions between the anticoagulant coating and the substrate surface at the molecular level, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed. The three-dimensional structures of heparin and dopamine were generated by converting their two-dimensional structures in Chemdraw software and processing them in MOE software. Four repeated monomers for each polymer were included to model the polymeric nature of the coatings. A silica substrate was chosen for the simulation due to its well-characterized and stable surface properties, which are commonly used in molecular simulations for studying surface interactions. While the blood pump materials in the study consist of biocompatible polymers and titanium alloys, the silica substrate was selected for its simplicity and ability to mimic surface interactions that are relevant to the coating process. Insights gained from the silica-based simulations, such as the interaction between dopamine and heparin, are applicable to a range of surfaces, including those typically used in blood pumps.

The dynamic simulation was conducted using Gromacs 2022 software with the Amber99sb-ildn force field to model the polymer chains. The water box was constructed using the TIP3P model, with dimensions of 18 × 18 × 18 nm3. Electrostatic interactions were analyzed using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method, and the steepest descent algorithm was applied for energy minimization (50000 steps). The cutoff distances for Coulomb and van der Waals interactions were set to 1 nm. The system was equilibrated under both a canonical (NVT) ensemble and an isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble at room temperature and pressure, with a 100 ns simulation run.

To simulate the effect of flow on the water molecules, an acceleration of 0.01 nm ps−2 was applied along the parallel substrate direction, denoted as "with flows". This approach provided insights into the stability of the heparin-dopamine coating and its potential behavior under flow conditions like those in a blood pump.

In contrast to the silica substrate used in the MD simulations, the actual pump was coated with a novel anticoagulant layer using a flow-driven deposition method. This method allows for the deposition of the dopamine-heparin coating under dynamic flow conditions, mimicking the physiological shear forces encountered during blood pump operation. The heparin was immobilized onto the surface of the pump components (which include biocompatible polymers and titanium alloys) through dopamine-induced polymerization, ensuring stable and uniform coating formation across the pump's internal and external surfaces. The similarity between the simulated flow effects on the coating and the flow conditions in the pump is critical, as it provides a basis for understanding how the coating will behave under operational conditions. Experimental verification of the coating's stability and anticoagulant performance was conducted through a series of in vitro perfusion tests, confirming the coating's effectiveness in reducing clot formation and promoting blood compatibility. Moreover, although in vitro cell adhesion tests confirmed good biocompatibility of the coating, the risk of excessive tissue adhesion on rotating pump surfaces was not investigated in this study and requires further in vivo evaluation.

6.2. Preparation of anticoagulant coatings

Dopamine-enhanced binding facilitated the application of a heparin sodium anticoagulant coating onto a 10 × 10 mm monocrystalline silicon wafer substrate, utilizing both traditional beaker and fluid-driven methods. A reaction tank was designed for the fluid-driven preparation, guided by CFD simulation results, with a corresponding experimental setup constructed.

For the sodium heparin fluid-driven preparation, the system's circulator was initially rinsed with PBS buffer and deionized water. The substrate was centrally positioned within the reaction bath. Dopamine pretreatment was administered according to the classical protocol [44], a 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 8.5) was prepared, into which 2 mg/ml of dopamine hydrochloride was dissolved and introduced into the circulation line via the Y-valve. The peristaltic pump-maintained circulation at a critical shear rate for 1 h. Post-reaction, the system was rinsed again with deionized water. Subsequently, sodium heparin (2 mg/ml) was dissolved in a 0.05 M MES buffer (pH = 5.5), enhanced with EDC and NHS at concentrations of 0.1 M and 0.05 M, respectively. After 10 min of activation, this solution was fed into the recirculation line, maintaining the reaction for 6 h at room temperature, followed by a final rinse with deionized water. The conventional coating was similarly prepared but employed a static beaker environment for the substrate.

To ensure reproducibility of the fluid-driven deposition, the flow conditions were standardized by quantifying wall shear stress (WSS) and Reynolds number (Re) within the reaction slot. WSS was calculated from CFD as:

| (2) |

where μ is the fluid viscosity (0.001 Pa s) and ∂u/∂y is the velocity gradient at the wall. At the selected flow rate of 63 mL/min, the mean WSS was 6.8 ± 0.5 dyn/cm2, with a peak <12 dyn/cm2, which lies within the physiological shear range of small-vessel perfusion. The Reynolds number, calculated as:

| (3) |

was ∼220 ± 15, indicating a predominantly laminar regime with minor entrance effects. Flow profiles were verified numerically and by dye-stream visualization to confirm uniform shear distribution and to exclude vortex formation. These parameters serve as reproducibility benchmarks for the fluid-driven coating process.

6.3. Coating stability test

The resistance of the anticoagulant coatings to fluid erosion was assessed using both conventional and fluid-driven methods. A 4 L reservoir, representing the total volume of human blood, was integrated and connected post-disconnection at the Y-valve. The system, filled with deionized water, underwent a circulation flow rate exceeding that typically used in targeted hypothermia treatments (63 mL/min). Samples were extracted for analysis after 30 and 60 min.

6.4. Morphology and microstructure of anticoagulant coatings

The surface morphology of the coating was initially gold-sputtered and subsequently examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, Quanta FEG250, FEI, USA) at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. The resulting images were analyzed using Image Pro Plus software. To facilitate more detailed analysis and 3D imaging of the coating surface, due to the limited resolution of SEM, scanning probe microscopy (SPM, SPI3800 SPA400, NSK, Japan) was employed. The SPM, utilizing Tapping measurement mode, assessed an 8 × 8 μm area at the center of the samples, with a scanning rate of 0.3 Hz and 256 scan lines per sample, facilitating the calculation of 3D imaging and surface roughness. In addition, cross-sectional SEM analysis revealed that the polydopamine–heparin coating exhibited a uniform thickness of ∼15 nm, which falls within the typical range reported for PDA-assisted coatings.

Functional group characterization was conducted using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet 50, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) spanning the range of 4000-600 cm−1 with a resolution of 1.9284 cm−1. Subsequently, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Axis Ultra DLD, KRATOS, UK) was employed for two primary purposes: analyzing surface roughness and performing surface chemical elemental analysis of the samples. This XPS instrument, utilizing an Al Kα-ray source, operated in a vacuum environment (9.8 × 10−10 Torr). Settings for full-spectrum acquisition included a voltage of 15 kV, a filament current of 10 mA, and a test fluence energy of 40 eV. Calibration of the test was based on the energy criterion of C 1s at a binding energy of 284.80 eV.

6.5. Platelet adsorption assay with anticoagulant coating

Fresh whole blood from anonymous donors was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 15 min to obtain platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Then, 50 μL of PRP was applied to the surface of both experimental and control samples, followed by a 30-min incubation at 37 °C. After incubation, the samples were washed with 0.9 wt% NaCl solution to remove non-adherent platelets and subsequently fixed using 2.5 wt% glutaraldehyde solution. Post-fixation, the samples underwent dehydration, alcohol removal, and drying. Finally, platelet adhesion was assessed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

6.6. Pump design and variations

The CBP was engineered to draw autologous blood from the femoral artery and selectively infuse it into the cerebral infarction area via an interventional catheter, aiming to provide a neuroprotective effect and reduce cerebral infarction volume. The structural composition and optimization of the CBP were tailored to achieve an optimal design, characterized by low HI and enhanced blood compatibility, as determined by numerical simulation.

6.7. CFD implementations

The goal of the CFD analysis was to evaluate the pressure, velocity, and shear stress distributions within the centrifugal pump, providing insights into the pump's hemodynamics. The mesh was generated using ICEM CFD 2020 R2 (ANSYS Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA) with a tetrahedral mesh structure, where the average grid size ranged from 0.034 to 0.041 mm. Numerical simulations were performed using ANSYS Fluent 2020 R2 (ANSYS Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA), employing momentum equations and assuming an incompressible fluid model. The standard k-ε turbulence model and wall functions were applied for the finite element models of the CBP, and simulations calculated steady-state conditions. Although large-eddy simulation (LES) can capture unsteady vortical structures with higher accuracy, the k–ε RANS model was selected in this study because it balances accuracy and computational efficiency for rotary blood pump simulations, consistent with prior reports. Future work will include LES validation for selected operating points to further refine hemocompatibility predictions.

Dynamic mesh methods simulated the impeller's rigid body rotation, and mesh independence was verified by comparing coarse (∼0.8 million), medium (∼1.6 million), and fine (∼3.2 million) grids. The differences in pressure rise and shear stress between the medium and fine meshes were <3 %, confirming mesh-independent results. The medium mesh was therefore adopted for subsequent simulations. The SIMPLE algorithm was used for calculations, setting a convergence criterion with a 10−3 residual for continuity and ensuring that the mass flow rate difference between the inlet and outlet was below 0.1 %. Blood was modeled as a Newtonian incompressible fluid, with a density of 1052 kg/m3 and a viscosity of 3 mPa s [45]. Boundary conditions were established with static pressure at the inlet and outlet (0 Pa), and no-slip wall conditions were applied, with the fluid flow entirely governed by the rotor's rotation.

To enhance reproducibility and allow standardized reporting of flow conditions, the local Reynolds number within the pump was calculated using the characteristic impeller diameter (D = 18 mm) and average circumferential velocity. Across the operating range of 300–2000 rpm, Re varied from ∼280 to ∼1850, indicating laminar-to-transitional flow conditions consistent with small-scale centrifugal pumps. Wall shear stress (WSS) distributions were extracted on impeller blades and casing surfaces, reported in dyn/cm2, providing a reproducible reference for shear-exposure levels. These metrics enable direct comparison of hemodynamic loading across different pump designs and can serve as standardized benchmarks for future CFD-based optimization of coating protocols and device structures.

In addition, residence time distribution (RTD) was analyzed using both Lagrangian and Eulerian approaches. For the Lagrangian method, more than 10,000 neutrally buoyant particles were seeded at the inlet and tracked until outlet. Increasing the particle number by 50 % resulted in <2 % variation in mean residence time, confirming insensitivity to streamline count. To complement this, an Eulerian scalar transport method (μ·▽T = 1)was also solved to obtain continuous residence-time fields. Both methods yielded consistent RTD trends, validating the robustness of the analysis. Prolonged residence regions were considered indicative of stasis and potential thrombosis risk. Platelet activation was further evaluated using a shear-stress–exposure-time model, where the platelet activation parameter (AP) was calculated as:

| (4) |

with τ representing the instantaneous shear stress, = 50 Pa as the critical threshold, and α = 2 as an empirical constant. Regions with elevated AP values were considered prone to platelet activation.

6.8. Hemolysis models

Hemolysis, resulting from the rupture of RBCs, is closely associated with Reynolds shear stress in the blood flow field [46]. The HI can be quantified by shear-induced hemolysis, derived from CFD and particle tracking simulations. HI is defined as the ratio of the amount of free hemoglobin (dHb) released due to hemolysis to the total hemoglobin (Hb) content [47]. The power law model for hemolysis is expressed as follows:

| (5) |

where t represents the exposure time of RBCs in the flow field, and τ is the coordinate scalar shear stress acting on RBCs; C, α, and β are constants obtained from experimental data [48,49]. Assuming τ remains constant over the time interval dt, HI for a given particle track is calculated as [50]:

| (6) |

The scalar shear stress accounts for the 3D turbulent flow shear stress, also referred to as Reynolds shear stress, as indicated in Ref. [51]:

| (7) |

6.9. The in vitro experiment setup

Two types of blood pump head through 3D printing were fabricated used plastic polymers with good biocompatibility as materials, was divided into the blood pump specifically designed for low flow in this study and the commercial blood pump (LivaNova®) specifically designed for ECMO. To assess the volume flow rate and flow stability of the pump's optimal design, in vitro experiments were conducted using a magnetically levitated centrifugal pump. Prototypes based on the optimal design were fabricated and evaluated. A test bench was established to evaluate the performance of the designed pump as depicted in Tab.S1, employing a simulated blood fluid. Due to the significance of materials and coatings in blood compatibility, actual blood was not used in the experiments. The simulated blood fluid was collected and stored in a reservoir. Volume flow rate measurements were conducted using a KEYENCE FD-XA1/FD-XC1R2/FD-XS1 (Osaka, Japan). The experiments aimed to explore the relationship between rotation speed and volume flow rate, with the flow rate's stability also assessed. Rotation speed varied from 500 to 2000 rpm in increments of 250 rpm, with an accuracy of 1000 ± 5 rpm. Flow rates were recorded at steady states, and each rotation speed was tested five times. All in vitro bench experiments were repeated five times at each rotational speed setting, and results are reported as mean ± SD.

6.10. Animal study

Animal experiments adhered to the National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Animal Research Committee of Tonghe Litai Company (IACUC-D2024026). All rabbits (weight: 2.50 ± 0.30 kg, 5 rabbits per group) were maintained on a standard laboratory diet. Rabbits were anesthetized with a single intramuscular injection of 1 % pentobarbital sodium (1 mg/kg), followed by hair removal around the surgical site. A midline incision, extending from the thyroid cartilage to the sternum, was made on the right side. The animals breathed spontaneously throughout the surgery. A 6–8 cm incision enabled sequential dissection of the muscle layers to expose and isolate the right common carotid artery and jugular vein. After distal ligation of these vessels, a 6F vascular sheath was inserted retrogradely into the common carotid artery and anterogradely into the jugular vein, secured with 3-0 silk sutures. Catheters were introduced into the arterial and venous sheaths to establish the extracorporeal circulation pathway.

After surgical connection, extracorporeal circulation was maintained for 120 min in each rabbit. No systemic anticoagulation was administered beyond the localized effect of the pump coatings, allowing us to directly evaluate the hemocompatibility and antithrombotic performance of the coated versus uncoated pumps. Blood samples (5 mL) were collected at the conclusion of circulation for coagulation assays. Plasma was separated within 30 min. The specimen was centrifuged at 3000 r/min for 10 min to allow plasma stratification. The upper plasma layer was then collected and placed in a fully automated coagulation analyzer (model RAC-1830) to measure the rabbit's Prothrombin Time (PT), Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT), and Thrombin Time (TT).

6.11. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 9.4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was utilized to assess the normality of continuous variables. These variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) if normally distributed, or as median (interquartile range, IQR) if not. Comparisons between two groups were made using the unpaired t-test for normally distributed data, or the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. For comparisons among multiple groups, analysis of variance (ANOVA) on ranks was employed. A two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Miaowen Jiang: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Chunhao Yu: Visualization, Methodology. Yiming Huang: Visualization, Methodology, Investigation. Xing Zhao: Conceptualization. Shiyi Xu: Methodology. Hongkang Zhang: Methodology. Yunong Shen: Visualization. Xiaofei Han: Supervision. Duo Chen: Project administration. Kun Wang: Investigation, Conceptualization. Xunming Ji: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Ming Li: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Data and materials availability

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animal experiments adhered to the National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Animal Research Committee of Tonghe Litai Company (IACUC-D2024026).

Funding

Beijing Natural Science Foundation 7244510 (MJ)

CHF-brain 2024-1-5041 (MJ)

CHF-brain 2024-3-2062 (ML)

Collaborative innovation project by Chinese Institutes for Medical Research CX25XT02 (MJ)

National Natural Science Foundation of China 82402444 (MJ); 52531008(ML); 82102220 (ML); 82027802 (XJ)

Beijing Hospitals Authority Clinical Medicine Development of special funding support (YGLX202527) (MJ)

Excellent Youth Fund of Capital Medical University B2305 (ML)

The Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical 2023-JKCS-09 (ML); 2023-JKCS-13(MJ)

Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support from Yangfan Project YGLX202325 (ML)

Research Funding on Translational Medicine from Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission Z221100007422023 (ML)

Declaration of competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of editorial board of Bioactive Materials.

Contributor Information

Duo Chen, Email: chenduozx2751@163.com.

Kun Wang, Email: wangkunggg@buaa.edu.cn.

Xunming Ji, Email: jixm@ccmu.edu.cn.

Ming Li, Email: liming@xwhosp.org.

References

- 1.Puentener P., Schuck M., Kolar J.W. CFD assisted evaluation of In vitro experiments on bearingless blood pumps. IEEE T Bio-Med Eng. 2020;68:1370–1378. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2020.3030316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y., et al. Multi-indicator analysis of mechanical blood damage with five clinical ventricular assist devices. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022;151 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Combes A., et al. Feasibility and safety of extracorporeal CO2 removal to enhance protective ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome: the SUPERNOVA study. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:592–600. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05567-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schöps M., et al. Hemolysis at low blood flow rates: in-vitro and in-silico evaluation of a centrifugal blood pump. J. Transl. Med. 2021;19:2. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02599-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rambod E., Beizai M., Rosenfeld M. An experimental and numerical study of the flow and mass transfer in a model of the wearable artificial kidney dialyzer. Biomed. Eng. Online. 2010;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaudry S., Palevsky P.M., Dreyfuss D. Extracorporeal kidney-replacement therapy for Acute kidney injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;386:964–975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2104090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Rijn R., et al. Hypothermic machine perfusion in liver transplantation - a randomized trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:1391–1401. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu C., et al. Safety, feasibility, and potential efficacy of intraarterial selective cooling infusion for stroke patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy. J. Cerebr. Blood Flow Metabol. : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2018;38:2251–2260. doi: 10.1177/0271678X18790139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belanger A., Decarmine A., Jiang S., Cook K., Amoako K.A. Evaluating the effect of shear stress on graft-to zwitterionic polycarboxybetaine coating stability using a flow cell. Langmuir. 2018;35:1984–1988. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b03078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J., Huang N., Li Q., Chu C.H., Li J., Maitz M.F. The effect of electrostatic heparin/collagen layer-by-layer coating degradation on the biocompatibility. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016;362:281–289. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li N., Guo C., Wu Y.H., Zheng Y.F., Ruan L.Q. Comparative study on corrosion behaviour of pure Mg and WE43 alloy in static, stirring and flowing Hank's solution. Corrosion Eng. Sci. Technol. 2012;47:346–351. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y., Zhang S., Li J., Song Y., Zhao C., Zhang X. Dynamic degradation behavior of MgZn alloy in circulating m-SBF. Mater. Lett. 2010;64:1996–1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J., et al. Flow-induced corrosion behavior of absorbable magnesium-based stents. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:5213–5223. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaffer I.H., Weitz J.I. The blood compatibility challenge. Part 1: Blood-contacting medical devices: the scope of the problem. Acta Biomater. 2019;94:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belanger A., Decarmine A., Jiang S., Cook K., Amoako K.A. Evaluating the effect of shear stress on Graft-To zwitterionic polycarboxybetaine coating stability using a flow cell. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2019;35:1984–1988. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b03078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He C., et al. Bioinspired shear-flow-driven layer-by-layer in situ self-assembly. ACS Nano. 2019;13:1910–1922. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b08151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu H., Jiang Y., Yang D., Scheiflinger F., Wong W.P., Springer T.A. Flow-induced elongation of von Willebrand factor precedes tension-dependent activation. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:324. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00230-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arce N.A., et al. Activation of von Willebrand factor via mechanical unfolding of its discontinuous autoinhibitory module. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:2360. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22634-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao C., et al. Layered nanocomposites by shear-flow-induced alignment of nanosheets. Nature. 2020;580:210–215. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joo H., Byun E., Lee M., Hong Y., Lee H., Kim P. Biofunctionalization via flow shear stress resistant adhesive polysaccharide, hyaluronic acid-catechol, for enhanced in vitro endothelialization. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2016;34:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou P., et al. Rapidly-Deposited polydopamine coating via high temperature and vigorous stirring: formation, characterization and biofunctional evaluation. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhirowo Y.P., et al. Hemolysis and cardiopulmonary bypass: meta-analysis and systematic review of contributing factors. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2023;18:291. doi: 10.1186/s13019-023-02406-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sing C.E., Alexander-Katz A. Dynamics of collapsed polymers under the simultaneous influence of elongational and shear flows. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;135 doi: 10.1063/1.3606392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doyle P.S., Ladoux B., Viovy J.-L. Dynamics of a tethered polymer in shear flow. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000;84:4769. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.4769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider S., et al. Vol. 104. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 2007. pp. 7899–7903. (Shear-induced Unfolding Triggers Adhesion of Von Willebrand Factor Fibers). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu J.H., Sarathy S., Ramesh S., Rudolph K., Raghavan M.L., Badheka A. Vol. 38. 2023. pp. 771–780. (Risk Factors for Hemolysis with Centrifugal Pumps in Pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Is Pump Replacement an Answer? Perfusion). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma J., et al. Protection of multiple ischemic organs by controlled reperfusion. Brain circulation. 2021;7:241–246. doi: 10.4103/bc.bc_59_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berg N., Fuchs L., Prahl Wittberg L. Flow characteristics and coherent structures in a centrifugal blood pump. Flow Turbul. Combust. 2018;102:469–483. [Google Scholar]

- 29.He C., et al. Bioinspired shear-flow-driven layer-by-layer in situ self-assembly. ACS Nano. 2019 doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b08151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao C., Zhang P., Zhou J., Qi S., Liu M. Layered nanocomposites by shear-flow-induced alignment of nanosheets. Nature. 2020;580:210–215. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang M., et al. The intra‐arterial selective cooling infusion system: a mathematical temperature analysis and in vitro experiments for acute ischemic stroke therapy. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2022;28:1303–1314. doi: 10.1111/cns.13883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kosaka R., Sakota D., Nishida M., Maruyama O., Yamane T. Improvement of hemolysis performance in a hydrodynamically levitated centrifugal blood pump by optimizing a shroud size. J. Artif. Organs : the official journal of the Japanese Society for Artificial Organs. 2021;24:157–163. doi: 10.1007/s10047-020-01240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taskin M.E., Fraser K.H., Zhang T., Wu C., Griffith B.P., Wu Z.J. Evaluation of Eulerian and Lagrangian models for hemolysis estimation. ASAIO J. 2012;58:363–372. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e318254833b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fossum T.W., et al. Complications common to ventricular assist device support are rare with 90 days of DeBakey VAD support in calves. ASAIO J. 2001;47:288–292. doi: 10.1097/00002480-200105000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wernicke J.T., et al. A fluid dynamic analysis using flow visualization of the Baylor/NASA implantable axial flow blood pump for design improvement. Artif. Organs. 2010;19:161–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1995.tb02306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schima H., et al. Minimization of hemolysis in centrifugal blood pumps: influence of different geometries. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 1993;16:521–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dahlbäck B. Blood coagulation. Lancet. 2000;355:1627–1632. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02225-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramstack J.M., Zuckerman L., Mockros L.F. Shear-induced activation of platelets. J. Biomech. 1979;12:113–125. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(79)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sabino R.M., Kauk K., Madruga L., Kipper M.J., Martins A.F., Popat K.C. Enhanced hemocompatibility and antibacterial activity on titania nanotubes with tanfloc/heparin polyelectrolyte multilayers. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2020;108 doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spadarella G., Mi Nn O.A.D., Donati M.B., Mormile M., Mi Nn O.G.D. From unfractionated heparin to pentasaccharide: Paradigm of rigorous science growing in the understanding of the in vivo thrombin generation. Blood Rev. 2020;39 doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2019.100613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leslie D., Waterhouse A., Ingber D.E. New anticoagulant coatings and hemostasis assessment tools to avoid complications with pediatric left ventricular assist devices. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.03.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.A honokiol-mediated robust coating for blood-contacting devices with anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and antithrombotic properties. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2021;9 doi: 10.1039/d1tb01617b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White F.M.J. 2011. Fluid Mechanics. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee S.J., et al. Heparin coating on 3D printed poly (l-lactic acid) biodegradable cardiovascular stent via mild surface modification approach for coronary artery implantation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;378 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bozzi S., et al. Fluid dynamics characterization and thrombogenicity assessment of a levitating centrifugal pump with different impeller designs. Med. Eng. Phys. 2020;83:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ozturk M., O'Rear E., Papavassiliou D. Reynolds stresses and hemolysis in turbulent flow examined by threshold analysis. Fluid. 2016;1 [Google Scholar]