Abstract

The novel (nua) kinases 1 and 2 are two of 12 AMP-activated protein–related kinases whose signaling pathways are involved in cancer progression, as well as neurologic, fibrotic, and inflammatory diseases. Currently, there are 80 Food and Drug Administration-approved kinase inhibitors which target roughly 24 of the 500+ known human kinases, leaving most kinases underexplored, including NUAK1 and NUAK2. Thus, there is a critical need for selective inhibition of NUAK1 and NUAK2 signaling. Here, we review the protein structure, known upstream regulators and downstream targets, and expression profiles of NUAK1 and NUAK2 in cancerous compared to noncancerous tissue. We also delineate the biological roles and signaling pathways of the NUAK kinases in a range of malignancies, focusing on cancer but also covering noncancerous physiology, and the therapeutic potential of NUAK kinase inhibition. We summarize the known small-molecule NUAK kinase inhibitors in preclinical models and one inhibitor in clinical trials. This review highlights the signaling mechanisms and therapeutic value of targeting NUAK kinase signaling pathways with specific, small-molecule NUAK inhibitors.

Keywords: AMP-activated protein–related kinase (ARK), novel (nua) kinases 1 and 2 (NUAK1 and NUAK2), small-molecule kinase inhibitor, serine/threonine protein kinase, phosphorylation

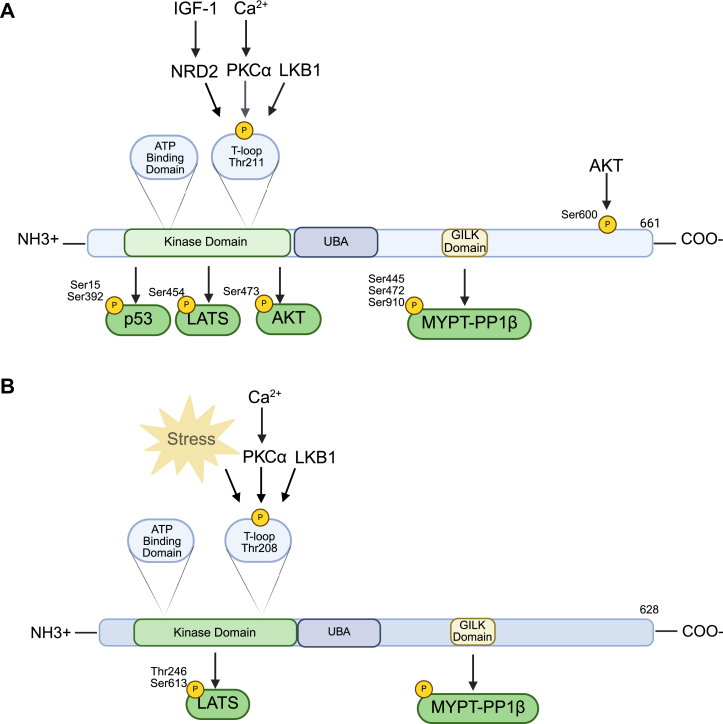

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a serine/threonine protein kinase, key cellular metabolic sensor, and mediator of cell proliferation and polarity (1, 2). Notably, there are 12 AMP-activated protein–related kinases (ARKs), including novel (nua) kinase 1 (NUAK1) and 2 (NUAK2) which are involved in a broad range of biological and physiological roles. In humans, the NUAK1 gene is located on chromosome 12 and encodes a protein of 661 amino acids (Fig. 1A) with an estimated molecular weight of 76 kDa (3). The NUAK2 gene is found on chromosome 1 of the human genome and encodes a protein of 628 amino acids (Fig. 1B) with an estimated molecular weight of 70 kDa (3). NUAK1 and NUAK2 exhibit 58% homology in their amino acid protein sequences (3, 4), exhibit similar structural organization to the other members of the ARKs, and demonstrate sequence homology with the catalytic subunit of AMPK (5). Like the other ARK family members, NUAK1 and NUAK2 contain an N-terminal catalytic domain with a highly conserved activation T-loop and a noncatalytic C-terminal domain with a spacer sequence (6). Next to the C-terminal end of their catalytic domains, the ARKs contain a ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain, which can bind to ubiquitin, an important protein tag that plays a role in protein degradation and other signaling processes in the cell (7), which is likely required for liver kinase b1 (LKB1) activation demonstrated through experiments with other members of the ARK family (7). The UBA domain is a unique feature of the ARK proteins and each ARK ubiquitin domain has low sequence homology with each other though they consist of similar three-helix bundle folds that can associate with ubiquitin (8, 9). AMPK lacks a clear UBA domain that is characteristic of the ARKs, but its alpha subunit has some homology to the UBA domain (8). Finally, conserved Gly-Ile-Leu-Lys regions are located on both NUAK1 and NUAK2 near the C-terminal domain which interacts with myosin phosphatase target subunit 1 (MYPT1), protein phosphatase 1 beta (10). NUAK1 and NUAK2 are the only known ARKs to contain Gly-Ile-Leu-Lys domains (10). Signaling pathways of the NUAK kinases have been extensively reviewed (4, 11, 12) but will be covered here briefly for completeness.

Figure 1.

Overview of phosphorylationof NUAK1and NUAK2.A, protein structure, upstream activators, and downstream targets of NUAK1. B, protein structure, upstream activators and downstream targets of NUAK1.

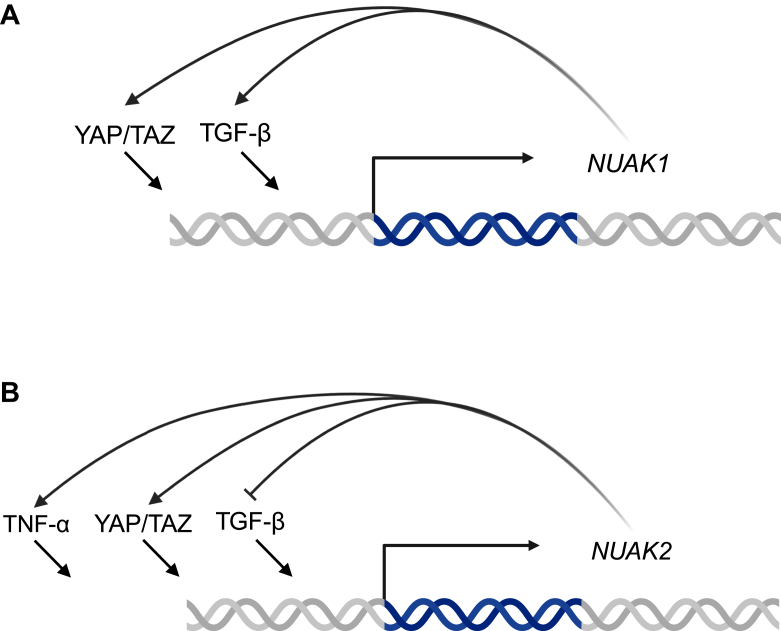

NUAK1 and NUAK2 signaling involves a complex interplay of pathways crucial for proper cellular function and dysregulation of these pathways leads to a range of diseases including cancer, neurodevelopmental diseases, fibrosis, and gastrointestinal diseases like inflammatory bowel disease (13, 14). Upstream regulators of the NUAK kinases remain under investigation, but the most well-known regulator is LKB1 which activates AMPK and the ARK family, except maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase, through phosphorylation. LKB1 activates NUAK1 and NUAK2 by phosphorylating threonine residue 211 and 208 (Thr211 and 208), respectively, within the T-loop located in the catalytic domain (13). Additionally, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), upon binding to its cell membrane receptor, induces the expression of both NUAK1 and NUAK 2 (15) which then exert negative or positive feedback on TGF-β, respectively (15) (Fig. 2, A and B). Unique to NUAK1, protein kinase B (AKT) phosphorylates NUAK1 at serine residue 600 (Ser600) and leads to a 3-fold increase in enzymatic activity (3, 16). Furthermore, nuclear dbf2–related kinase 2 (NDR2) phosphorylates NUAK1 at threonine residue 211 (17). NDR2 is activated by insulin-like growth factor-1, which phosphorylates NDR2 at three residues (17). NUAK1 is also activated by calcium signaling through the action of PKC (18). Upstream of NUAK2, increased AMP, indicative of cellular stress (19), enhances NUAK2 enzymatic activity by 2- to 3-fold (19). NUAK2 gene expression is upregulated by yes1-associated transcriptional regulator (YAP)/tafazzin (TAZ) as well as tumor necrosis factor alpha (20, 21) (Fig. 2B). NUAK1 gene expression is also upregulated by YAP/TAZ signaling, but has not yet been identified to be increased downstream of tumor necrosis factor alpha (21) (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Overview ofgenetic regulation ofNUAK1 andNUAK2.A, regulators of NUAK1 gene expression. UBA, ubiquitin-associated domain; NUAK, novel (nua) kinase. B. regulators of NUAK1 gene expression. UBA, ubiquitin-associated domain; NUAK, novel (nua) kinase.

NUAK1, in the presence of functional LKB1, has a wide variety of downstream effects. Tumor protein 53 (p53) is activated via phosphorylation by NUAK1 in response to cellular stress signals (22). Specifically, in the presence of LKB1, NUAK1 phosphorylates p53 at Ser15 and Ser392, especially in glucose-starved cell culture conditions (16). Furthermore, NUAK1 directly phosphorylates large tumor suppressor kinase 1 at S464 (23) which is a known modulator of the YAP/TAZ complex and has been implicated in various cellular homeostasis pathways (24). NUAK2 also activates YAP/TAZ (20) by phosphorylating LATS at Thr246 and Ser613, which inhibits LATS-mediated phosphorylation of YAP/TAZ and results in nuclear localization of the YAP/TAZ complex and transcription of downstream factors (20). Subsequently, YAP/TAZ downstream mediators’ upregulate NUAK2 gene expression in a positive feedback loop (25). NUAK1 mediates cellular trafficking and migration via phosphorylation of AKT at Ser473 and phosphorylation of MYPT1 at Ser445, Ser472, and Ser910 (25, 26). NUAK2 also associates with the C-terminal domain of and phosphorylates MYPT1; however, the exact phosphorylation sites are not fully elucidated (21). Meanwhile, NUAK2 regulates myosin light chain (MLC) phosphatase by preferentially binding MLC’s regulatory protein, myosin phosphatase Rho-interacting protein (MRIP). MRIP binds MLC’s regulatory subunit, MYPT1, to regulate the disassembly of actin stress fibers in contractile, nonmuscular cells (27). When MRIP is associated with NUAK2, MLC phosphorylation increases, and actin stress fiber assembly is promoted (27). This association and its effects occur independently of NUAK2 phosphorylation, indicating that the role of NUAK2 extends beyond phosphorylation.

Of the 14 ARKs, NUAK1 and NUAK2 are less well-studied in the literature, and NUAK2 is a member of the “dark kinome,” comprised of 160 understudied kinases (28). Despite being relatively understudied, many of the signaling pathways regulated by the NUAK kinases, such as YAP/TAZ, p53, and AKT, and TGF-β, are dysregulated in various disease states, especially in cancer progression (29). Furthermore, NUAK1 and NUAK2 exhibit differential gene and protein expression in a variety of cancer types compared to normal tissues (Table 1), providing a basis for their potential targeting in cancer. NUAK1 and NUAK2 expression also correlate with clinical grade and stage of various tumors, which are critical measures of prognosis and can be used to guide treatment (Table 1). Since NUAK1 and NUAK2 signaling occurs through phosphorylation of downstream targets, small-molecule kinase inhibitors are a promising therapeutic option in NUAK-mediated cancer progression, with several already in use in vitro and many more in development (Table 2). Thus, further investigation of NUAK1 and NUAK2 tissue-specific expression, signaling pathways, and pharmacologic potential of their inhibition is critical and necessary. Here, we provide an updated review of cancers and other diseases where either NUAK1 or NUAK2 are more highly expressed in tumors than in matched normal tissue from the same patient or whose expression correlates with clinicopathologic features. This is followed by a description of NUAK1 and NUAK2 biological roles and mechanisms, highlighting studies which indicate phosphorylation targets of the NUAKs, thus shedding light on the therapeutic utility of NUAK kinase inhibitors.

Table 1.

NUAK1 and NUAK2 expression correlates with clinical parameters of cancer

| Cancer type | Clinicopathologic features | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Glioblastoma |

|

(31, 32) |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

|

(33) |

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma |

|

(35) |

| Breast cancer |

|

(42, 43, 44) |

| NSCLC |

|

(37, 38, 40) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma |

|

(50, 51, 52) |

| Gastric cancer |

|

(55, 56) |

| Colorectal carcinoma |

|

(59) |

| Pancreatic cancer |

|

(61, 62, 64) |

| Renal cell carcinoma |

|

(66) |

| Cervical cancer |

|

(67, 68) |

| Ovarian cancer |

|

(69) |

| Bladder cancer |

|

(20) |

| Prostate cancer |

|

(74, 75) |

| Acral melanoma |

|

(77, 79) |

Listed are 15 cancer types where either NUAK1, NUAK2, or both NUAK1 and NUAK2 are differentially expressed in normal compared to cancerous tissue or correlate with clinicopathologic features of disease.

(+), positively; (−), negatively; CESC, cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma; CRC, colorectal cancer; DFS, disease free survival; EAC, esophageal adenocarcinoma; ISH, in situ hybridization; IHC, immunohistochemistry; mCRPC, metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer; NUAK, novel (nua) kinase; OS, overall survival; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PFS, progression free survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival; TCGA, the cancer genome atlas program; TMA, tissue microarray; TNM, tumor, node, and metastasis; UALCAN, University of Alabama at Birmingham Cancer data analysis portal.

Table 2.

Utilization of small-molecule NUAK1 and NUAK2 inhibitors in preclinical models of DIsease

| Inhibitor | Preclinical model | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| HTH-01-015 | Non–small cell lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, liver fibrosis | (40, 53, 59, 62, 88) |

| KI-301670 | Pancreatic cancer | (63) |

| HTH-02-006 | Glioma, hepatocellular carcinoma, prostate cancer, kidney fibrosis | (32, 52, 74, 87) |

| WZ4003 | Non–small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, gastric cancer, bladder cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, kidney fibrosis | (20, 38, 39, 44, 57, 86, 87) |

| ON123300 | Gastric cancer, acute myeloid leukemia | (57, 83) |

List of small molecule inhibitors of NUAK and/or NUAK2 that have been used in in-vivo experiments.

NUAK, novel (nua) kinase.

Glioma

The NUAK family kinases have high expression in developing fetal brain and have been extensively reviewed in the context of neurological development and disorders of the nervous system (30). Accordingly, expression of these kinases correlates with clinicopathologic features of glioma, an invasive brain cancer with few treatment options. In 4 glioma patient tumors, NUAK1 protein was more highly expressed in tumor than in surrounding normal brain tissue from the same patient (31). In sections of 137 paraffin-embedded glioma samples, NUAK1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) expression negatively correlates with patient survival and clinicopathologic grade (31). Furthermore, NUAK2 mediates central nervous system development, and its expression in adult gliomas restores its developmental functions that are essential processes in fetal development, proliferation, and migration, but possess aberrant and malignant functions in adult brain (32). NUAK2 mRNA expression correlates with glioma grade and stage according to the cancer genome atlas program (TCGA) database (32), indicating its value as a prognostic biomarker in glioma. Thus, NUAK2 is highly expressed in stage 4 glioma. In 334 NUAK2 high glioma patients and 333 NUAK2 low patients, mRNA expression of NUAK2 negatively correlates with the percent probability of survival with NUAK2 high patients having a shorter percent probability survival than NUAK2 low glioma patients (32).

In line with the strong association of NUAK1 and NUAK2 expression with glioma outcome, preclinical studies have been performed to investigate the role of NUAK in glioma. One study demonstrates that transient silencing of NUAK1 with siRNA in LN-229 human glioblastoma (GBM) cells resulted in decreased invasion and migration, but no change in proliferation, indicating a role for NUAK2 in increasing glioma cell motility and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (31) Furthermore, NUAK1 mediates glioma invasion through extracellular matrix (ECM) rearrangement, and siRNA silencing of NUAK1 in LN-229 cells reduces matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 (MMP-2 and MMP-9) protein expression by Western blot (31). Part of what renders gliomas so malignant is their highly invasive nature, thus further studies into the exact relationship between NUAK1 and ECM remodeling are warranted. One proposed mechanism of NUAK1-mediated GBM motility and invasion is through actin cytoskeletal rearrangement. NUAK1 knockdown in LN-229 cells results in reduced F-actin polymerization in response to IGF-1 stimulation (31). F-actin polymerization occurs downstream of cofilin, which is phosphorylated at Ser3 by LIM kinase 1 (LIMK 1) (31) (Fig. 3). In NUAK1 knockdown LN-229 cells, IGF-1 stimulation resulted in reduced phosphorylation of cofilin and LIMK by Western blot and IGF-1 treatment induced coimmunoprecipitation of NUAK1 with LIMK (31) indicating that NUAK1 acts upstream of LIMK and cofilin in GBM, and a potential mechanism through which NUAK1 mediates GBM cell motility. While further studies are necessary to demonstrate whether NUAK1 phosphorylates LIMK, their direct interaction evidenced by coimmunoprecipitation suggests that LIMK is a potential target of NUAK1. Like NUAK1, NUAK2 regulates the ECM in glioma. The NUAK2 specific inhibitor HTH-02-006 reduced proliferation, colony formation, and migration of human glioma U251 cells (32), and CRISPR knockout of NUAK2 in the human GBM cell line U251 exhibited increased expression of ECM genes by gene ontology analysis (32). While no mechanism has been suggested for NUAK2 to date, it is hypothesized that cellular stress due to nutrient deprivation or increased ECM stiffness in GBM may result in overactivation of NUAK2 and consequent disruption of downstream signaling (32). Additionally, NUAK2 is essential for development of the fetal brain, thus reactivation in adult tissues could drive processes involved in development-like cell proliferation and migration (32). Since both NUAK1 and NUAK2 drive aggressive glioma biology in vitro, targeting these kinases has the potential to decrease the clinically devastating metastatic features of glioma.

Figure 3.

Mechanism of NUAK1 and NUAK2 in cancer. The proposed signaling pathways of NUAK1 and NUAK2 in human cancer derived from functional assays in human cancer cell lines. ECM, extracellular matrix; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; CSC, cancer stem cell; NUAK, novel (nua) kinase.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC) is rare in the United States, with the highest incidence in Africa and Asia. While NPC most commonly develops in patients with Epstein–Barr virus, there are numerous other risk factors and the cause of NPC is not fully understood (33). According to the online database Oncomine, mRNA expression of NUAK1 is elevated in 31 NPC samples compared to 10 normal nasopharynx samples (33). IHC staining of patient samples revealed positive correlation of NUAK1 staining positivity with lymph node size and with high-risk tumor subtype. In over 100 patients, high NUAK1 expression predicted lower overall and disease-free survival (33). Functional studies for both NUAK1 and NUAK2 are warranted to understand the role of NUAK signaling in NPC.

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

Esophageal cancer exhibits a high rate of mortality globally and can be subdivided into esophageal adenocarcinoma, which is associated with Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), whose risk factors include alcohol consumption and smoking (34). NUAK1 expression has potential prognostic value in ESCC, while NUAK2 has not been investigated. In ESCC, NUAK1 mRNA expression is elevated compared to adjacent normal esophageal epithelial tissues and to esophageal adenocarcinoma in samples from the TCGA ESCC in the University of Alabama at Birmingham Cancer data analysis portal as well as three Gene Expression Omnibus datasets (GSE23400, GSE44021, and GSE53625) (35). High NUAK1 expression correlated with lower overall survival in ESCC patients. Additionally, NUAK1 protein is elevated in cancerous compared to normal esophageal tissues by IHC staining of patient samples (35). Moreover, high NUAK1 expression by IHC positively correlates with lymph node metastasis, tumor invasion depth, advanced pathological tumor, node, and metastasis stage, and poor survival outcomes in ESCC patients (35). Ultimately, NUAK1 expression could be a useful biomarker and potential target in ESCC.

As NUAK1 expression correlates with prognostic factors that represent invasion and nodal metastasis, studies to investigate NUAK1-mediated invasion and metastasis in vivo and in vitro have been performed (35). In EC109 and KYSE510 human ESCC, NUAK1 promotes invasion and migration of cells when overexpressed by lentiviral plasmid (35). Additionally, mice injected with NUAK1-overexpressing EC109 cells showed higher lung metastasis than vector control on necropsy (35). In mouse tissues obtained from metastases of NUAK1-overexpressing EC109 tumors, pan-phospho-mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 (Jnk) and stain family transcriptional repressor 2 (Slug) were increased by IHC staining, indicating that NUAK1 could facilitate metastasis through phosphorylation of JNK1/2, leading to phosphorylation of AP-1 transcription factor subunit (c-JUN), and transcription of SLUG, a mediator of EMT. Accordingly, in NUAK1 knockdown human ESCC cells, total c-Jun and phospho-c-Jun at Ser73 is decreased as demonstrated by Western blot (35). Furthermore, phospho-JNK (Thr183), but not total JNK, was increased in NUAK1-overexpressing human ESCC cell lines EC109 and KYSE510, and coimmunoprecipitation studies demonstrated association of NUAK1 with JNK in KYSE30 human ESCC cells (35). Taken together, this suggests that NUAK1 mediates ESCC motility and invasion via phosphorylation of JNK at Thr183 resulting in SLUG-mediated EMT (Fig. 3) (35). The role of NUAK2 in ESCC was not investigated in this study, as no studies have yet demonstrated that NUAK2 expression correlates with clinical parameters of ESCC.

Non–small cell lung cancer

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer related mortality in the United States, and non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is responsible for 85% new lung cancer cases with risk factors including smoking and air pollution (36). Both NUAK1 and NUAK2 expression correlate with prognostic measures of NSCLC. In patient samples of NSCLC paired with adjacent normal lung, NUAK1 protein is increased in cancerous samples compared with normal lung samples (37, 38), and both NUAK1 and NUAK2 mRNA expression is elevated in NSCLC compared to normal lung according to the TCGA database (38). Both NUAK1 and NUAK2 mRNA are elevated in metastatic NSCLC compared to the primary site, and there is a positive correlation between NUAK1 and NUAK2 expression with tumor stage (39). NUAK2 also predicts clinicopathologic parameters of NSCLC where analysis of NSCLC samples by gene expression profiling interactive analysis demonstrated negative correlation between NUAK1 and NUAK2 expression with patient survival (38). Likewise, Kaplan–Meier analysis showed negative correlation between NUAK1 expression and survival, and separately, multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression revealed NUAK1 as an independent prognostic risk factor in NSCLC (40).

Accordingly, NUAK1 mediates NSCLC cell resistance to chemotherapy in vitro (39, 40). NUAK1 inhibition through either siRNA or pharmacological treatment with the dual NUAK1 and NUAK2 inhibitor (WZ4003) in NSCLC cell lines (NCL-H1299, HCC827, A549) prior to chemotherapeutic agent gefitinib treatment had significantly reduced viability as measured by cell counting kit-8 assay (a colorimetric viability assay) and proliferative capacity via 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine assay compared to control NSCLC cell lines (39). Additionally, NUAK1 exerts protective effects in response to reactive oxygen species (ROS) in NSCLC. In EGFR-mutant NSCLC, NUAK1 expression leads to osimertinib resistance via protection from ROS. NUAK1 phosphorylates nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide kinase at Ser64, resulting in generation of NAD+ which is reduced in the presence of ROS to NADH, eliminating ROS and conferring survival to EGFR mutant NSCLC cell lines (Fig. 3). Thus, in osimertinib resistant NSCLC cell lines (HCC827, PC9, and H1975), NUAK1 overexpression by plasmid transfection reduced ROS measured by mitochondrial damage and ROS marker dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate by flow cytometry. Also, overexpression of NUAK1 in these cell lines increased the IC50 value of osimertinib. Treatment with HTH-01-015, a NUAK1 inhibitor, reduced ROS in these NSCLC cells and reversed osimertinib resistance as measured with viability assays (40).

Furthermore, NUAK1 and NUAK2 promote proliferation, motility, and metastasis of NSCSC in vitro (37, 38). In NSCLC cell lines A549, NCI-H460, and NCI-H522, but not in normal lung epithelial line L-132, treatment with dual NUAK kinase inhibitor WZ4003 reduced proliferation and altered cell morphology. Independent knockdown of NUAK1 and NUAK2 by CRISPR reduced growth, motility, and Transwell migration of the same NSCLC cell lines; and siRNA knockdown of the other NUAK kinase exhibited an additive effect in reduction of proliferation (38). Additionally, A549 and NCI-H460 NSCLC cells treated with glycolytic inhibitor 2-deoxy-d-glucose exhibited reduced migration, which was further reduced by addition of NUAK1 and NUAK2 genetic inhibition (38). Ultimately, NUAK1 and NUAK2 are hypothesized to reduce NSCLC growth and migration through glucose metabolism reprogramming via phosphorylation and inhibition of p53 at Ser15, resulting in upregulation of mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (mTOR) signaling (Fig. 3) (38).

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality in women and is classified into subtypes based on presence or absence of hormone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (41). Both NUAK1 and NUAK2 have clinical prognostic value in breast cancer. NUAK1 and NUAK2 RNA is upregulated in about 30 breast cancer patient samples compared to paired normal breast tissue (41, 42). NUAK2 RNA expression positively correlates with breast cancer stage and lymph node metastasis (42), and NUAK1 expression inversely correlates with survival in a clinical cohort of 160 breast cancer patients followed for 14 years from the time of histopathologic diagnosis (43). NUAK1 IHC staining intensity of patient tumor samples positively correlates with clinical stage and lymph node metastasis. Patients with high NUAK1 IHC tumor staining intensity demonstrated shorter overall survival than patients with low NUAK1 staining intensity (43). Additionally, clinical samples from patients with high NUAK2 IHC expression had lower overall survival than samples with low expression (42). In a separate study via analysis of 4 breast cancer datasets (GSE15852, GSE42568, GSE54002, and TCGA), NUAK1 and NUAK2 mRNA expression is higher in tumor tissue than normal breast, positively correlates with tumor stage and grade, and is more highly expressed in metastasis compared to primary tumor (44).

Since both NUAK1 and NUAK2 are positively associated with breast tumor stage, grade, and lymph node metastasis, preclinical investigation into the roles of NUAK1 and NUAK2 in EMT and invasion have recently been performed. Both NUAK1 and NUAK2 promote invasion through upregulation of breast cancer cell glucose and glutamine metabolism, which was assayed using the dual NUAK inhibitor WZ4003 and independent CRISPR knockdown of NUAK1 and NUAK2 in cell lines (44). The mechanism of NUAK-mediated invasion is hypothesized to occur through upregulation of the mTOR pathway evidenced by decreased phosphorylation of downstream mTOR effectors Thr389 on S6K1 and Thr70 of factor 4E binding protein 1 in NUAK1 and NUAK2 CRISPR MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 human breast cancer cells (44) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, genetic overexpression of NUAK1 in SKBR3 and MCF-7 cells resulted in increased Matrigel-coated Transwell migration, increased EMT related protein vimentin (VIM), and decreased epithelial proteins E-cadherin (CDH1) and β-catenin (CTNNB1) compared to empty vector control (43). In a separate study, NUAK1 was genetically overexpressed in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) MDA-MB-231 cells resulting in increased invasion and MMP protein expression in the cell lines, as well as increased tumor growth and lung metastasis in vivo (45), indicating that NUAK1 overexpression increases invasion in three subtypes of breast cancer in vitro. NUAK2 has a role in TNBC growth downstream of YAP/TAZ pathway in vivo, whereby NUAK2 siRNA knockdown via CRISPR reduced the rate of MDA-MB-231 tumor growth in an orthotopic model of C.B-17 SCID mice (20). However, only tumor growth was investigated here, despite NUAK1 and NUAK2 roles in invasion, metastasis, and EMT.

Uniquely, NUAK1 may regulate the tumor immune microenvironment. When the TCGA BRCA gene expression dataset was analyzed using CIBERSORTx, an analytical tool which estimates abundances of immune cell populations within tumors, NUAK1 high breast tumors had lower levels of inflammatory and activated (“antitumor”) immune cells, while the NUAK1 low group exhibited higher resting and anti-inflammatory (“protumor”) immune cells (43). Accordingly, NUAK1 expression predicts a more aggressive tumor stroma when analyzed with MD Anderson’s ESTIMATE computational tool to measure tumor purity; this is hypothesized to be due to the infiltration of protumor immune cells, allowing the tumor to evade immune suppression and consequently grow and metastasize (43). Despite the role of NUAK2 in EMT and invasion, no studies regarding NUAK2 and the tumor immune microenvironment have been reported thus far.

Roles for both kinases exist in the context of oxidative stress, yet the antioxidant role of NUAK1 is only vaguely defined in TNBC cell lines. In response to hydrogen peroxide, NUAK1 undergoes translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in the TNBC cell line MDA-MB-231. While it is unknown whether NUAK1 has antioxidant roles, glucose starvation conditions leading to oxidative stress increases NUAK1 kinase activity (46). Thus, oxidative stress may activate NUAK1, but further research is needed to outline a mechanism for NUAK1 in the context of oxidative stress in TNBC. Meanwhile, in TNBC cell lines MDA-MB-231 and BT-549, NUAK2 promotes ferroptosis, a form of iron-dependent oxidative stress. NUAK2 genetic overexpression decreased glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) mRNA, promoting ferroptosis in a kinase-independent manner, evidenced by lack of a significant difference in GPX4 expression between BT-549 cells with overexpression of kinase dead NUAK2 and WT NUAK2. When both NUAK kinases were independently genetically silenced, only NUAK2 knockdown increased viability in BT-549 cells treated with GPX4 inhibitor to induce ferroptosis, indicating that NUAK2 promotes ferroptosis, while NUAK1 is not involved (47).

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common subtype of liver cancer which exhibits frequent recurrence post resection and for which there is a critical need for new prognostic biomarkers (48, 49). NUAK1 and NUAK2 exhibit prognostic value in HCC; NUAK1 IHC staining of clinical samples revealed enrichment of NUAK1 expression in 20 tumor samples compared with adjacent normal tissue from the same patients. NUAK1 RNA and protein levels are upregulated in HCC patient samples compared to normal liver from the same patients, and its IHC staining negatively correlated with survival by Kaplan–Meier plot (50, 51). Likewise, NUAK2 was more highly expressed in 233 HCC tumor samples compared to paired normal liver tissue from the same patients (52). Thus, both NUAK kinases are potential molecular prognostic markers in HCC, which motivated preclinical assays to investigate the roles of NUAK1 and NUAK2 in HCC.

In vitro and in vivo assays demonstrate that both NUAK1 and NUAK2 promote invasion of HCC. Genetic overexpression of NUAK1 promotes HCC cell proliferation and migration in human HCC cell lines Huh-7, HepG2, SNU-368, SNU-739 (50). In a separate study, the small-molecule NUAK1 inhibitor HTH-01-015 was applied to HCC cell lines SNU-387 and HepG2, resulting in decreased EMT gene and protein expression (VIM and N-cadherin (CDH2)), decreased migration, invasion, and MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression (53). In BALB/c mice injected with NUAK1-overexpressing H22 murine HCC cells, tumor size, and lung metastasis were increased (50). Similarly, NUAK2 knockdown by shRNA suppressed human HCC lines Huh-7 and Hep2G proliferation, invasion, and migration (54). One proposed mechanism of NUAK1-mediated tumorigenesis is downstream of Dickkopf-1 (DKK1), a glycoprotein upregulated in many cancers and that promotes migration and invasion of HCC cells (50). Silencing of DKK1 by siRNA reduced NUAK1 protein expression in human HCC cell lines SNU-387 and HepG2. Notably, DKK1 overexpression in human HCC cells upregulates AKT phosphorylation at Ser-473, an upstream activator of NUAK1, presenting the likely mechanism of DKK1–mediated p-AKT activation. Consequent increased activity of NUAK1 promotes HCC invasion and metastasis, but a mechanism through which this occurs should be outlined in future studies (50). Meanwhile, NUAK2 is a known transcriptional target of YAP, a driver of HCC, and knockout of Yap reduced Nuak2 expression in a mouse model of HCC, confirming downstream regulation of Nuak2 by Yap in vivo (52). Similarly, in human HuCCT-1 cholangiocarcinoma cell lines, knockdown of YAP reduces NUAK2 mRNA expression. The dual knockout of Nuak2 and Yap by adenovirus mediated Cre recombinase in mouse liver resulted in decreased proliferation and growth of mouse liver and number of tumors, indicating that NUAK2 could promote HCC tumor growth and tumorigenesis downstream of YAP. Accordingly, genetic knockdown and pharmacological inhibition of NUAK2 with the NUAK2-specific inhibitor HTH-02-006 in YAP-high cell lines (HuCCT-1 and SNU475) resulted in a more marked reduction of cell growth as measured by crystal violet staining compared to that of YAP-low cell lines (HepG2 and SNU398) (52). Ultimately, preclinical studies indicate value in NUAK2 inhibition in HCC, especially in patients with high YAP activity.

Gastric cancer

Despite low rates of diagnosis in the United States, gastric cancer (GC) tends to be diagnosed late requiring improved biological markers for early detection (55). Both NUAK1 and NUAK2 expression are upregulated in GC; however, only NUAK1 predicts clinical prognostic parameters, while the prognostic value of NUAK2 remains to be explored (56). In biopsies from 117 gastric tumors and 46 samples from normal adjacent tissue, NUAK1 IHC expression is higher in GC than adjacent normal tissue. Also, NUAK1 positively correlates with depth of tumor invasion, metastasis, stage, and grade of tumors (55). Among these 117 patients, NUAK1 expression negatively correlated with recurrence free survival and overall survival (55). Studies evaluating NUAK2 expression demonstrated that NUAK2 was upregulated by Western blot in 8 human GC patient samples compared to normal adjacent tissue from the same patients (56). Considering that both NUAK1 and NUAK2 expressions are elevated in GC, preclinical investigation has been performed to determine the role of their signaling pathways in GC progression.

In GC cell line studies, NUAK1 and NUAK2 promote the formation of cancer stem cells (CSCs). Overexpression of NUAK1 kinase-dead mutant K84A in AGS GC cell line reduced signal transducer and activator of transcription 5A phosphorylation and GLI family zinc finger 1 (GLI1) protein levels by Western blot, validating a partial role for NUAK1 in the GLI1 pathway which mediates formation of CSCs (57). NUAK1 overexpression enhances GLI1 gene and protein expression, a transcription factor downstream of Hedgehog signaling, likely through phosphorylation of Ser726 on signal transducer and activator of transcription 5A which stabilizes GLI1 protein. GLI1 mediates GC CSC formation via transcription of genes such as SOX2, which mediates cancer cell self-renewal (Fig. 3) (57). Human GC cells treated with the dual NUAK1 and NUAK2 kinase inhibitor WZ4003 exhibited downregulated GLI1 protein and GLI1 target genes (57). Additional studies indicate that NUAK2 also upregulates CSC markers in GC. In NUAK2 overexpressing human GC cell line SGC-7901, gastric CSC markers aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A1, CD44, and CD133 are upregulated compared to empty vector control (56).

As CSCs promote chemotherapy resistance, additional studies have investigated the link between NUAK1 expression and GC chemotherapy response. Genetic silencing of NUAK1 in MKN45 and AGS GC cells improved sensitivity to the chemotherapeutic oxaliplatin (57). In vivo, treatment of BALB/c mice with ON123300, a multikinase inhibitor that potently inhibits NUAK1, significantly reduced MKN45 xenograft tumor growth compared to no treatment, and also increased sensitivity to oxaliplatin (57). While ON123300 is a multikinase inhibitor, NUAK1 overexpression in this xenograft model reversed ON123300-mediated chemosensitivity, demonstrating that NUAK1 is sufficient for chemotherapy resistance (57).

Colorectal cancer

Over half of advanced colorectal cancer (CRC) patients demonstrate resistance to standard of care chemotherapy, oxaliplatin, necessitating investigation into drivers of chemoresistance, including NUAK1 (58). In clinical CRC samples, NUAK1 is overexpressed, and its expression positively correlates with patient survival. RNA-scope in situ hybridization of a microarray of over 600 patient CRC samples showed that NUAK1 has low expression in colonic epithelium but is highly expressed in aggressive CRC (59). Analysis of the TCGA RNA-Seq colorectal adenocarcinoma cohort revealed that high NUAK1 expression correlates with cancer stage and lymph node metastasis. Additionally, NUAK1 expression negatively correlated with survival in a meta-analysis cohort comprising about 1000 patients (59). In contrast, there is no clinical data regarding NUAK2 expression, despite in vitro studies demonstrating NUAK2 relevance in CRC.

In preclinical studies, both NUAK1 and NUAK2 are involved in CRC cell response to oxidative stress. NUAK2 is downregulated in the human CRC Caco-2 cell line in response to probiotic antioxidants, implying that increased expression of NUAK2 may correlate with oxidative damage to colonic epithelium (60). Conversely, NUAK2 is upregulated in Caco-2 cells in response to hydrogen peroxide treatment, a chemical oxidant (60). Whether the increased expression of NUAK2 during oxidative stress is protective or indicates that NUAK2 positively regulates oxidative stress is unclear; all that is known is that NUAK2 expression positively correlates with oxidative stress. Meanwhile, in vitro studies suggest that NUAK1 is protective during oxidative stress in human CRC, promoting an adaptive antioxidant response characteristic of malignant GC (59). siRNA knockdown of NUAK1 and treatment with the NUAK1 inhibitor HTH-01-015 in human GC U2OS cells reduced hydrogen peroxide induced nuclear translocation of the antioxidant response protein nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (NRF2), an antioxidant transcription factor activated upon oxidative stress. Likewise, silencing NUAK2 with siRNA in SW620 CRC cells reduced protein expression of NRF2 in response to hydrogen peroxide treatment (59). Thus, both NUAK1 and NUAK2 share regulation of NRF2-mediated antioxidant response in CRC.

NUAK1 contributes to oxaliplatin chemotherapy resistance in oxaliplatin-resistant human CRC HCC116 and H716 cells, which is hypothesized to occur through NRF2 signaling and subsequent suppression of ferroptosis (58). NUAK1 silencing by siRNA plus oxaliplatin treatment promoted cellular apoptosis and modulated indicators of ferroptosis compared to NUAK1 siRNA alone. The oxaliplatin sensitivity of NUAK1 silenced cells was reversed by a pharmacological NRF2 agonist (58). Furthermore, treatment with the NUAK1 inhibitor HTH-01-015 suppressed gene expression of NRF2 mediated downstream signaling molecules upon oxaliplatin treatment. Additionally, NRF2 activation reduces cellular indicators of ferroptosis like ROS and lipid peroxidation, and it is hypothesized that inhibition of ferroptosis is a mechanism used by CRC to resist chemotherapy treatment (58). Overall, NUAK1 is thought to upregulate protein phosphatase 1 beta, resulting in increased phosphorylation of Ser9 of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK3β), inactivating GSK3β, leading to nuclear translocation of NRF2 which is responsible for translation of antioxidant genes including GPX4 (58) (Fig. 3). Ultimately, NUAK2 requires further investigation in CRC, but NUAK1 inhibition could aid in combating CRC chemoresistance.

Pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer exhibits a high rate of mortality with few treatment options outside of surgical resection (61) necessitating the search for biomarkers of disease. NUAK1 and NUAK2 both possess prognostic significance in pancreatic cancer. NUAK1 protein is elevated in pancreatic adenocarcinoma patient samples compared to paired normal tissue (61). Additionally, in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most common subtype of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, NUAK1 RNA expression is higher in PDAC than normal pancreas in an online cohort, and patients with NUAK1 high PDAC tumors exhibit shorter survival than NUAK1 low tumors (62). Furthermore, p-NUAK1 is elevated by IHC in a microarray of 100 PDAC samples, and NUAK1 protein was elevated in PDAC cell lines AsPC-1, Mia PaCa-2, PANC-1, and Capan-2 compared to normal pancreatic cell line HPNE (63). Likewise, NUAK2 is more highly expressed by IHC staining in PDAC tumors compared to adjacent normal pancreatic tissue (64). These data prompt preclinical investigation into NUAK1 and NUAK2 in pancreatic cancer.

Accordingly, NUAK1 signaling helps maintain genomic integrity during mitosis by regulating centrosome replication (62). Inhibition of NUAK1 with NUAK1 inhibitor HTH-01-015 or genetic NUAK1 knockdown leads to mitotic defects, supernumerary chromosomes, and consequently reduces cancer cell viability in the human PDAC cell line Mia PaCa-2 (62). Loss of NUAK1 in untransformed mouse embryonic fibroblasts resulted in supernumerary chromosomes compared to controls, indicating that NUAK1-mediated centrosome replication in normal cells could lead to toxicity in normal tissues, akin to what is observed following chemotherapy treatments (62). NUAK1 is hypothesized to prevent supernumerary centrosomes through phosphorylation of MYPT1, which phosphorylates Ser9 of GSK3β, which promotes polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4) turnover likely through phosphorylation of Thr170 (62). PLK4 mediates replication of centrosomes, and, thus, NUAK1 inhibition prevents PLK4 turnover, resulting in overactivation of PLK4 and centrosome replication (62) (Fig. 3). In accordance with this role, in a separate study, NUAK1 inhibition by NUAK1 inhibitor KI-301670 induced G0/G1 cell cycle arrest of Mia PaCa-2 cells (63). In addition to cell cycle regulation, the treatment of Mia PaCa-2 cells with KI-301670 also inhibited invasion and metastasis in the cell line and inhibited tumor growth in vivo. Ultimately, NUAK1 inhibition is theorized to promote cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, resulting in decreased tumor volume in in vivo xenograft PDAC mouse models (63). Meanwhile, studies on NUAK2 in vitro and in vivo demonstrated that knockdown of NUAK2 results in increased chemosensitivity (64). In human pancreatic cancer cell line SW1990, knockdown of NUAK2 by siRNA decreased total and phosphorylated SMAD2 and SMAD3, decreased EMT marker protein expression of snail family transcriptional repressor 1 (SNAI1) and CDH2, and decreased matrix protein fibronectin (FN1), indicating a relationship between NUAK2, EMT, and ECM remodeling (64). si-NUAK2 transfected human pancreatic cancer cells (SW1990 and PxPC-3) also had higher sensitivity to gemcitabine, a standard-of-care chemotherapeutic to treat pancreatic cancer, than control cells, evidenced by lower survival per cell counting kit-8 assay and elevated apoptosis by expression of annexin V/PI on flow cytometry (64). When NUAK genetic knockdown was examined in vivo using a human p53 mutant PDAC cell line BxPC-3, NUAK2 genetic knockdown xenograft tumors had decreased tumor volume and KI67 protein expression compared to control, indicating a reduction in cancer cell proliferation (64). While chemotherapy resistance was not evaluated in p53 WT in vivo studies, clinical database analysis demonstrates that NUAK2 mRNA expression is higher in in WT p53 than in mutant p53 tumors, prompting a need to consider p53 status of pancreatic cancer models when examining the role of NUAK2 on PDAC chemotherapy resistance (64, 65). The exact mechanism through which SMAD3 activation by NUAK2 promotes pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis is not known, though it is hypothesized that resistance to gemcitabine is mediated through NUAK2 phosphorylation of SMAD2 at Ser465 or 467 and SMAD3 at Ser423 or 425. Phosphorylated SMAD2 and SMAD3 form a trimeric complex with SMAD4, translocate to the nucleus, and transcribe genes involved in chemoresistance like SNAI1 and FN1. Additionally, a SMAD4-independent route is hypothesized to occur downstream of SMAD2 and SMAD3 phosphorylation involving phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (Fig. 3) (64). Thus, targeting NUAK2 in pancreatic cancer could be a promising method to combat chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer.

Renal cell carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common type of renal tumor, and NUAK1 immunohistochemical staining is higher in clinical samples of RCC than non-neoplastic cases (12). Further, NUAK1 IHC staining level of patient samples positively correlated with tumor stage and tumor mitotic index and were negatively associated with patient survival, tumor apoptotic index, and chemotherapy response by retrospective analysis of patient survival (66). There is no literature currently describing the clinicopathologic relevance of NUAK2 in renal cancer.

Few cell-based studies have been published for the NUAKs in RCC, but one preclinical study suggests that NUAK1 drives chemotherapy resistance through NUAK1 mediated efflux of chemotherapeutic agents; however, further investigation is required to support this (66).

Cervical cancer

Screening for cervical cancer (CC) has improved early detection and prevention, but the search for targetable biomarkers which drive CC pathogenesis remains crucial (67). NUAK1 is a prognostic marker in CC, as NUAK1 RNA expression is elevated in 8 CC patient samples compared to normal adjacent tissue from the same patients, and NUAK1 expression negatively correlates with survival in endocervical adenocarcinoma (68). Likewise, NUAK2 is more highly expressed in CC tumors than in normal cervical tissue and in CC cell lines than in normal primary cervix cells as observed in the University of Alabama at Birmingham Cancer data analysis portal tumor database (67). NUAK2 protein expression is elevated in CC patient tumors compared to normal cervix (67). While NUAK2 expression is differential in tumor tissue and normal cervix, NUAK2 is not known to correlate with clinical parameters of CC.

NUAK2 promotes EMT in preclinical CC cell line studies. Genetic silencing of NUAK2 in human CC HeLa cells reduced Matrigel-coated Transwell invasion and motility as measured by scratch assay (67). Furthermore, shRNA knockdown of NUAK2 reduced levels of mesenchymal proteins SNAI1, VIM, and CDH2 while increasing E-cadherin-1 levels, suggesting that NUAK2 drives invasion through EMT in CC (67). Based on this promising preclinical data, additional studies using more CC cell lines with NUAK inhibitors or CRISPR knockdown should be performed to provide further support for the role of NUAK2 in CC. Meanwhile, in vitro studies on NUAK1 have not identified a direct role for NUAK1 in CC biology but instead demonstrated that it acts downstream of a cancer susceptibility gene called CASC18 (68). Further investigation is required to determine exactly how NUAK1 signaling mediates CC biology.

Ovarian cancer

The most common type of ovarian cancer is high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) which exhibits a high rate of peritoneal metastasis (69). Analysis of several Affymetrix microarray datasets and quantitative polymerase chain reaction of formalin-fixed HGSOC samples revealed negative correlation of NUAK1 RNA expression with progression-free survival (69). Additionally, NUAK1 transcript level was lower in less differentiated subtypes of ovarian cancer and was positively associated with risk of disease diagnosis at an older age along with risk of residual disease post tumor debulking surgery (69). Notably, a clinical barrier to the treatment of HGSOC is re-emergence of chemotherapy resistant tumors after initial tumor debulking surgery and chemotherapy (70); thus, NUAK1 inhibition could pose a solution. NUAK2 has not been extensively studied in ovarian cancer, and, unlike NUAK2, RNA expression of NUAK2 does not correlate with ovarian cancer patient survival (12).

Preclinical studies have identified a role for NUAK1 in EMT, cell adhesion, and resistance to oxidative stress in ovarian cancer. NUAK1 upregulates the production of proteins involved in EMT like CDH2, VIM, and alpha-smooth muscle actin in the ovarian cancer cell line HEY. Accordingly, when NUAK1 overexpression plasmid was added to embryonic germ cells which do not express NUAK1 protein, expression of EMT proteins increased and embryonic germ cells acquired a more mesenchymal morphology and improved migration and invasion capacity by scratch assay and Matrigel Transwell assay, respectively (71). Furthermore, in human ovarian cancer cells, NUAK1 mediates spheroid formation and integrity through the upregulation of FN1 (72, 73). Human ovarian cancer OVCAR8 spheroids generated from CRISPR knockdown NUAK1 cells had reduced adhesion, reduced integrity, and increased cell death, as well as a 745-fold decrease in FN1 gene expression. The ability to form spheroids allows de-adhered ovarian cancer cells to evade death by anoikis, a form of cell death of anchorage-dependent cells induced by de-adherence to a surface, and renders ovarian cancer cells resistant to chemotherapies (72). Thus, NUAK1 is theorized to have a role in ovarian cancer cell adhesion potentially preventing tumor cell death by anoikis and permitting survival and metastasis. Another study indicates antioxidant properties of NUAK1 such that genetic knockdown of NUAK1 reduces ROS levels in human ovarian cancer cell line OVCAR8 signaling in HGSOC, which is hypothesized to promote cell survival in ovarian cancer cells (70) and potentially confer resistance to chemotherapy treated ovarian cancer cells. To date, no preclinical studies on NUAK2 in ovarian cancer have been published.

Bladder cancer

Muscle invasion is a predictor of poor prognosis in bladder cancer, and NUAK2 expression is elevated in high-grade nonmuscle invasive bladder tumors and in muscle invasive bladder tumors compared with nonmuscle invasive tumors. In a cohort of muscle-invasive bladder cancers, NUAK2 positively correlated with disease recurrence. NUAK2 expression is also higher in bladder cancer cell lines derived from patients with high-grade bladder cancers (TCCSUP, T24, RT112) than in cell lines derived from low grade bladder cancers, (SW780, HTB-2) (20). Notably, NUAK2 expression positively correlates with YAP expression and with many YAP target genes in bladder cancer patient samples (20) suggesting that NUAK2 mediates bladder cancer progression through YAP signaling. While NUAK1 was evaluated in bladder cancer, there was no observed link between NUAK1 expression and clinical significance.

Genetic knockdown of NUAK2 or pharmacological inhibitor treatment with dual NUAK1 and NUAK2 inhibitor WZ4003 resulted in growth arrest of high-grade muscle invasive bladder cancer cell lines TCCSUP and T24 human bladder cancer cell lines (20). Further experiments focusing on NUAK2 inhibition should be conducted to tease apart the roles of NUAK1 and NUAK2 in bladder cancer. As TCCSUP and T24 are characterized by aggressive invasiveness, future studies could evaluate the role of NUAK1 and NUAK2 in invasion and metastasis in bladder cancer.

Prostate cancer

Androgen receptor inhibition is the leading treatment option for metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer; however, resistance to therapy is increasing, prompting a need for new biomarkers and targets in prostate cancer management (74). Both NUAK1 and NUAK2 correlate with clinicopathologic features of prostate cancer. Evaluation of 37 patient prostate cancer samples separated into high and low NUAK1 mRNA expression demonstrated that the NUAK1 high tumors exhibited lower prostate cancer survival than the NUAK1 low tumors (75). Additionally, NUAK2 was more highly expressed in 457 prostate cancer patient samples compared to 57 control samples by TCGA database analysis. NUAK2 is also higher in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer than in normal matched tissue from the same patients. Cox regression analysis on a cohort of over 600 patients revealed that the upper 50 percentile of NUAK2 expression positively correlated with increased metastasis risk (74). In line with the correlation of NUAK1 and NUAK2 with survival and metastasis in clinical samples, preclinical data suggests that both NUAK1 and NUAK2 mediate prostate cancer EMT, likely contributing to metastasis.

NUAK1 promotes EMT, migration, and invasion in two prostate cancer cell lines (DU145 and PC-3). NUAK1 silencing by siRNA in these cells decreases RNA expression of mesenchymal markers VIM and FN1 while increasing epithelial marker CDH1. Furthermore, NUAK1 silencing by siRNA reduced DU145 and PC-3 Transwell migration and cell motility (75). While NUAK2 was not investigated here, other studies indicate a role for NUAK2 in prostate cancer EMT. In a separate study using human prostate cancer cell lines DU-145 and HMVP2, NUAK2 inhibition via small-molecule NUAK2 inhibitor HTH-02-006 reduced 2D and 3D Matrigel invasion (74). Accordingly, RNA sequencing of HMVP2 cells treated with HTH-02-006 showed diminished EMT pathway enrichment compared to vehicle treated cells. In vivo studies with HTH-02-006 slowed prostate cancer tumor growth in FVB mice bearing HMVP2 spheroid-generated tumors; however, no data describing changes in metastasis was noted here (74).

Melanoma

While NUAK2 is expressed to a low degree in some regions of normal skin, it is highly expressed in melanoma (76). Monoclonal NUAK2 antibody staining demonstrates strong NUAK2 positivity in a range of preneoplastic and cancerous patient skin samples like extramammary Paget’s disease, squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen’s disease, actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and angiosarcoma (76). NUAK2 is located on chromosomal region 1q32.1, which is commonly amplified in melanoma (76), and its expression is known to correlate with melanoma clinicopathologic features. Accordingly, NUAK2 gene expression negatively correlates with survival in acral melanoma by the publicly available database GSE2631 (77). In clinical samples, NUAK2 RNA expression positively correlates with tumor thickness (78). IHC staining of NUAK2 on patient samples shows positive correlation of NUAK2 with melanoma stage (78) and negative correlation with relapse-free and overall survival in acral melanoma samples (79). Due to the strong correlation of NUAK2 with clinical characteristics of acral melanoma, NUAK2 has been investigated in preclinical studies (77, 79).

Corroborating clinical findings, NUAK2 promotes migration and cell cycle progression in melanoma preclinical studies (79). NUAK2 promotes cell cycle progression in the melanoma cell line C32 where NUAK2 knockdown by shRNA reduces the number of cells in S phase and decreases cyclin expression, indicating impairment of G to S phase progression (79). In addition, NUAK2 knockdown by siRNA in primary cutaneous melanomas in vitro decreases migration by wound healing assay and decreases total protein levels of mTOR, which promotes cell growth (79). Studies were performed on phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-deficient NUAK2-amplified C32 and SM2-1 human melanoma cell lines as well as non-PTEN–deficient and non-NUAK2–amplified mel18 cell line. In C32 and SM2-1 cells, shRNA knockdown of NUAK2 reduced cyclin-dependent kinase-2 (CDK2) protein expression, illuminating how melanomas which overexpress NUAK2 have dysregulated cell cycle progression. CDK2 genetic silencing did not reduce mel18 cell proliferation, but it did significantly reduce C32 and SM2-1 proliferation. Thus, NUAK2-mediated CDK2 upregulation and consequent cell cycle progression and proliferation may be targetable in melanomas with PTEN deficiency and NUAK2 overexpression, but it is likely less impactful in other melanomas without these biomarkers (77). Further investigation of the mechanisms of NUAK2 could reveal additional biomarkers for NUAK inhibition in melanoma.

Hematological cancers (multiple myeloma and acute myeloid leukemia)

While no literature on NUAK1 or NUAK2 correlation with clinicopathologic parameters of hematological cancers exist to date, NUAK1 transcription is often increased in multiple myeloma (MM). A common chromosomal translocation in MM moves the gene for v-maf avian musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog proto-oncogene (MAF) into the heavy chain immunoglobulin coding region, resulting in MAF overexpression. NUAK1 is a transcriptional target of MAF, and, thus, translocation ultimately results in increased NUAK1 transcription, promoting cell growth, migration, and mitochondrial survival via increased mitochondrial fission (80). NUAK1 knockdown human MM cell lines, KMS-11 and Sachi, exhibited increased phosphorylated AKT protein as well as increased caspase3 and caspase9, and p27 protein, indicating that NUAK1 normally suppresses AKT-mediated cellular apoptosis. On the other hand, NUAK1 knockdown MM cells exhibited decreased CDK proteins, indicating that NUAK1 promotes cell cycle progression (80). Furthermore, NUAK1 knockdown cells exhibited decreased phosphorylation of dynamin-related protein 1 at Ser616, suggesting that NUAK1 promotes mitochondrial fission in MM (80). Clinical trials are underway for MM using the multikinase inhibitor ON123300, whose targets include NUAK1 (81, 82), but not NUAK2. While a recent preclinical study demonstrates ON123300 effectiveness against another hematological malignancy (acute myeloid leukemia) cell lines in vitro (83), no studies have yet outlined biological roles of the isolated effects of NUAK2 signaling in MM.

Anencephaly

Initially identified in keratinocytes upon UV-B radiation exposure, the gene for NUAK2 also goes by ANPH2, which comes from the fact that NUAK2 mRNA is highly expressed in embryonic neural tube tissue and is essential in neural tube development in humans. Homozygous NUAK2 mutant mice develop neurological deformities including anencephaly (84). In a recent case study, researchers reported repeated cases of anencephaly in a consanguineous family due to a germline mutation of NUAK2. Neural tube development depends on the Hippo–NUAK2 pathway which regulates cytoskeletal actomyosin contraction pulling the apical ends of developing embryonic cells together to form the neural tube. Specifically, phosphorylated and activated NUAK2 phosphorylates large tumor suppressor kinase 1/2 resulting in inhibition of YAP/TAZ phosphorylation and cytoplasmic sequestration and downstream actomyosin cytoskeletal rearrangement, allowing for proper neural tube folding (84).

Alzheimer’s disease

NUAK1 mediates embryonic neurodevelopment and proper dendrite function (84, 85), and dysregulation of NUAK1 in the brain in adults can lead to pathological states like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (86). Hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau are central features in various dementia-associated conditions, including primary and secondary tauopathies like AD. Notably, NUAK1 has emerged as a candidate kinase in AD and primary tauopathies, facilitating tau phosphorylation at Ser356. This was determined by treatment of human brain slice cultures with the dual NUAK1 and NUAK2 inhibitor WZ4003, resulting in decreased Ser356 phosphorylation of Tau by Western blot (86). This phosphorylation event may act as a catalyst for subsequent phosphorylation and aggregation. Additionally, NUAK1-mediated phosphorylation of tau at Ser356 regulates total tau levels by impeding its ubiquitination and degradation via the proteasome, a process involving the chaperone protein CHIP. NUAK1 expression is often elevated in postmortem AD brain tissues, with NUAK1 colocalizing with neurofibrillary tangles, further implicating its role in tau pathology (86).

Inflammatory bowel disease

Several papers have been published in the last 10 years describing NUAK2-mediated pathways that drive CRC (58, 59, 60). More recently, researchers found a role for NUAK2 in inflammatory bowel disease downstream of G protein–coupled receptor 65 (GPR65). GPR65 promotes intestinal mucosal inflammation via T helper cells (Th1 and Th17) signaling, and Gpr65 knockdown in mouse T cells ameliorates gut mucosal inflammation (14). Furthermore, in Gpr65 deleted CD4+T cells, Nuak2 gene is upregulated, indicating that the mechanism of intestinal inflammatory suppression could occur through Nuak2, with the mechanism of this regulation still under investigation (14).

Viral replication

NUAK2 is required for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (Sars-CoV-2) viral replication in host cells and indirectly required for viral entry via upregulation of SARS-CoV-2 receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (87). Viruses can trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR) by damaging the endoplasmic reticulum of host cells. Downstream of the UPR in the Sars-CoV-2 infected human cells viral response components (XBP1 and IRE1α) (87), and when viral response components are knocked down, NUAK2 is downregulated, indicating NUAK2 may be regulated by UPR. Additionally, virally infected cells may exert a paracrine effect on “bystander” uninfected cells, involving the upregulation of NUAK2 which may be involved in upregulating cell surface receptor expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 facilitating viral entry into bystander cells (87). The mechanism of NUAK2 mediated upregulation of receptor expression requires further investigation and NUAK1 does not appear to have a role in this context (87).

Fibrosis

NUAK1 transcription occurs downstream of TGF-β signaling, and NUAK1 participates in a feed forward loop with TGF-β and YAP/TAZ (Fig. 1B). NUAK1 gene, but not NUAK2, positively correlates with human renal fibrosis in 18 human kidney biopsies (87), positioning NUAK1 as a mediator of TGF-β–mediated renal fibrosis. In subsequent in vitro studies, NRK49F rat fibroblasts were treated with the NUAK1-specific inhibitor HTH-02-006 and dual NUAK1 and NUAK2 inhibitor WZ4003 in the presence or absence of TGF-β stimulation (86). HTH-02-006 treatment increased phospho-YAP protein in the presence of TGF-β stimulation, inhibited YAP translocation to the nucleus via immunofluorescence staining, and reduced expression of YAP inducible genes, indicating that NUAK1 is an essential downstream mediator of TGF-β induced YAP activation (86). Furthermore, in a murine inducible renal fibrosis model, genetic knockdown of Nuak1 in mouse fibroblasts as well as HTH-02-006 treatment reduced renal fibrosis by IHC in response to unilateral ureteral obstruction–induced fibrotic injury (86).

Fibrosis can also occur in the liver due to the progression of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) for which there are few treatment options available (88). NUAK1 gene expression is higher in patient MASH tissue than normal liver tissue, and NUAK1 gene expression positively correlated with TGF-β gene expression in these patient samples (88). To elucidate a mechanism of NUAK1 in MASH, the NUAK1-specific inhibitor HTH-01-015 was administered to mice in a model of inducible MASH. Administration of HTH-01-015 resulted in reduced liver injury evidenced by decreased serum liver enzymes, decreased liver weight and fibrosis, and decreased inflammation compared to control (88). To determine whether NUAK1 acts through caspase-6, a known driver of MASH and liver inflammation, the protein levels of cleaved-caspase 6 and downstream mediators of caspase-6 were decreased in HTH-01-015 treated mouse liver by Western blot compared to control (88). Caspase-6 inhibits TGF-β–activated kinase 1 (TAK1), and in HTH-01-015 treated mouse liver, TAK1 was decreased. Ultimately, through studies utilizing mouse hepatocytes, it was found that NUAK1 activates caspase-6 resulting in downstream inhibition of TAK1, reducing degradation of receptor-interacting serine/threonine kinase 1, allowing for pyroptosis (a form of cell death) and inflammation, which drive pathological liver fibrosis (88).

Development of NUAK1 and NUAK2 pharmacological inhibitors

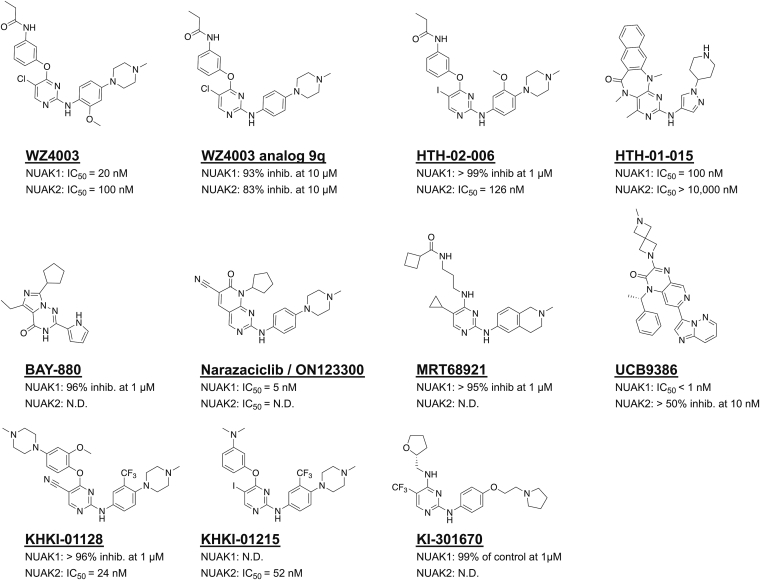

Since the NUAK kinase signaling pathways are involved in driving progression of a range of cancerous and noncancerous pathologies, (Fig. 3), a thorough review of the currently available NUAK inhibitor compounds is essential. Here, we summarize details of NUAK inhibitors that have been described to date (Table 2) (Fig. 4) and briefly provide leading information on other potential starting points suitable for medicinal chemistry efforts to target NUAK1 and NUAK2.

Figure 4.

Small-molecule inhibitors of NUAK1 and NUAK2. Depicted are the chemical structures of the commercially available inhibitors with biological activity against NUAK kinases and their IC50 for each NUAK kinase where N.D. stands for “not determined.” Of note, these compounds are not necessarily selective for the NUAKs but often inhibit other kinases as well (as described in the text and in the primary literature). NUAK, novel (nua) kinase.

A dual inhibitor of NUAK1 and NUAK2, WZ4003, was repurposed from a set of 2,4,5-tri-substituted pyrimidines, while HTH-01-015 was discovered through optimization of a set of pyrimido-diazepines known to have weak off-target NUAK1 activity (6). WZ4003 has a reported biochemical IC50 of 20 nM against NUAK1 and 100 nM against NUAK2, making it an attractive tool for dual inhibition. On the other hand, HTH-0--015 inhibited NUAK1 with an IC50 of 100 nM but did not show any inhibitory activity against NUAK2 (IC50 > 10 μM), underscoring its utility for testing NUAK1-specific roles in cancer cells (6). Both compounds were profiled for specificity by a panel of 140 kinases which included other closely related CAMK family members. At a concentration of 1 μM, HTH-01-015 reduced NUAK1 activity to 11% of control, while every other kinase retained at least 50% of control activity (6).

Medicinal chemistry efforts were undertaken on WZ4003 to optimize for efficacy against colorectal tumors. Removal of a single methoxy group from the parent compound, WZ4003 analog 9q, led to a more potent NUAK1 inhibitor with stronger antiproliferative activity and the potential for further development as an effective antitumor drug (89). Removal of this methoxy likely impacts the selectivity of the compound (rendering it less selective), but this was not examined in this article (89). HTH-02-006 is another analog of WZ4003 that was used to explore the role of NUAK2 inhibition in YAP signaling in liver cancer (52). It has an iodo-substituent in the 5 position of the core pyrimidine, instead of the chloro-substituent found in WZ-4003. It has an IC50 value of 126 nM against NUAK2. Its IC50 value for NUAK1 is not mentioned in the article, but from the kinome profiling it appears to have >99% I against NUAK1 when screened at a concentration of 1 μM. When evaluated in HuCCT-1 cells, the compound inhibits the phosphorylation of MYPT1, a NUAK2 (and NUAK1) substrate. The kinome wide selectivity of HTH-02-006 and WZ4003 are compared here, and HT-02-006 shows enhanced kinase selectivity (52).

Furthermore, WZ4003 has shown additive effects on cancer cell lines when used in combination with ULK1 inhibitor SBI-0206965 (90). Treatment of various human tumor cell lines including lung A549 and NCIH460, GBM U251, and GC MNK45 with WZ4003 small-molecule inhibitors upregulates ULK1. It is thought that since NUAK1 typically mediates protection of cells from oxidative stress via NRF2, described previously, that knockdown of NUAK1 would be sufficient to induce death in cancer cells. However, knockdown of NUAK1 by WZ4003 results in increased protein expression of phosphorylated ULK1 which mediates protective mitophagy and survival during oxidative stress, suggesting potential utility of dual ULK1/NUAK1 inhibitors. MRT68921 has been published as an ULK1 inhibitor (91), but it also has potent NUAK1 activity and it has potent antitumor activities, suggesting that combined inhibition of NUAK1 and ULK1 may be more efficacious in some settings (90).

Two published compounds, KRICT Hippo kinase inhibitor (KHKI)-01128 and KHKI-01215, have been described as (and are commercially available as) NUAK2 inhibitors, though there is little evidence to suggest they are selective over NUAK1 (92). These KHKI compounds were tested in biochemical assays using WZ4003 as a reference and showed greater potency against NUAK2 with IC50 values of 24 nM for KHKI-01128 and 52 nM for KHKI-01215 (92). In the KINOMEscan binding assay format, KHKI-01128 at 1 μM inhibited bead-bound ligand binding for NUAK1 by more than 95% and for NUAK2 by 87%, indicating robust binding to both targets (92). While KHKI-01128 was the more potent of the two and simultaneously displayed superior efficacy in cellular assays inhibiting colorectal cells, KHKI-01215 possesses a better selectivity profile in the KINOMEscan panel, binding to 11 out of the 410 kinases tested with a percent of control (PoC) <5% when screened at 1 μM (92). This improved selectivity suggests KHKI-01215 is a better starting point of these two options for future NUAK2 probe development from this scaffold.

BAY-880 has also been published as a NUAK1 inhibitor, inhibiting 96% of kinase activity at 1 μM. BAY-880 was screened against a panel of 274 kinases at a concentration of 1 μM, and showed >50% inhibition for 33 of the 274 kinases tested. Only 10 targets showed more than 80% inhibition at this concentration. While BAY-880 displayed potency against several other kinases, notably these off-targets differed from HTH-01-015 off-targets. Use of both BAY-880 and HTH-01-015 in phenotypic experiments could be useful to rule out off target effects and help confirm a NUAK1-specific mechanism in cells (93).

Additionally, KI-301670 was identified as a novel NUAK1 inhibitor (63). Selectivity studies were performed at a screening concentration of 1 μM against a panel of 42 oncogenic kinases, and KI-301670 was found to be a reasonably selective NUAK1 inhibitor with only 1% of control activity remaining at that dose. Eight out of the forty-two kinases tested had a PoC between 20 and 50%, and the remaining kinases (31 out of 52) had a PoC >50% at the 1 μM dose. However, none of the other 41 kinases tested were closely related to NUAK1; therefore, further profiling is required before KI-301670 can be deemed a selective chemical probe.

A recently published NUAK1 inhibitor is UCB9386, an imidazopyridine compound containing a spiro-azetidine (94). The starting point for UCB9386 came from a high-throughput screen which returned a compound with nanomolar potency against NUAK1 in an ATP-Glo assay and only exhibited >50% inhibition against eight kinases out of 365 tested at 1 μM. A medicinal chemistry campaign culminated in the discovery of UCB9386, with improved solubility, potency, and central nervous system penetrance. UCB9386 displayed single digit nanomolar potency against NUAK1 in a cellular dose-response assay. At 10 nM, UCB9386 still inhibited JAK2 and NUAK2 more than 50%, which means it does not possess the necessary selectivity for chemical probe status. Importantly, UCB9386 exhibits high brain penetrance, an essential feature for treating brain malignancies like glioma (94).

Finally, ON123300 is the only NUAK inhibitor to advance to clinical trials. ON123300 was first characterized as a dual NUAK1/CDK4 targeting compound, although a biochemical screen of 288 kinases revealed six kinases with an IC50 < 30 nM (95). Of the eleven compounds described in this section, only WZ4003 is recognized by the Chemical Probes Portal as a chemical probe, and even it suffered a low rating due to poor cellular activity and lack of characterization of the pharmacokinetic properties of the molecule (96, 97). ON123300 has been shown to be effective in MM due to its dual inhibition of NUAK1 and CDK4/6 and is currently planned for a phase I/II clinical trial in combination with dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory MM (82). Another phase I/IIa clinical trial is testing the efficacy of ON123300 in combination with letrozole for endometrial and gynecologic malignancies (81), and a third phase I trial is testing ON123300 for patients with relapsed or refractory advanced solid tumors (98).

In addition to the compounds mentioned above, a wide range of potential starting points that one could use in medicinal chemistry efforts towards probe development for NUAK1 and NUAK2 can be found in the literature. Many of these come from specially curated sets of kinase inhibitors and their biochemical data that have been made publicly available. The PKIS, containing 367 ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors, was published in 2016 (99) and was updated to PKIS2 in 2017 with over 500 compounds (100). PKIS and PKIS2 served as a launching point for the Kinase Chemogenomic Set (KCGS) (101), which is currently in its second iteration (KCGSv2.0). KCGSv2.0 contains 295 kinase inhibitors that have demonstrable activity on 262 human kinases. These resources have allowed for fast-tracking probe development and led to over 100 publications the decade following their release. These published compounds vary in their kinome-wide selectivity, and this feature needs to be weighed in their selection (or not) as starting point for medicinal chemistry. Out of the 663 compounds in PKIS2, 45 exhibited >50% inhibitory activity against NUAK1, and 82 exhibited >50% inhibitory activity against NUAK2 at a concentration of 1 μM. Importantly, 11 of those 45 potent against NUAK1 were highly selective for the NUAK1 isoform, demonstrating <20% inhibition of NUAK2, suggesting the possibility of developing NUAK1 (over NUAK2) selective probe compounds.

Similarly, 40 of the 82 compounds in this dataset inhibiting NUAK2 were selective over NUAK1. Numerous assays exist to test these inhibitors in different screening formats to confirm activity and drive a medicinal chemistry optimization program. The DiscoverX KINOMEscan (468 kinase panel) binding assay platform, available through Eurofins, includes both NUAK1 and NUAK2. Biochemical enzyme assays for NUAK1 and NUAK2 are available through several kinase assay vendors. Verification of activity in a cell is also critical for discovery of a chemical probe, and Promega’s NanoBRET assay format provides a suitable in-cell target engagement option. The availability of a range of diverse chemical starting points and appropriate methods of compound screening should support the development of both probes and drugs for NUAK1 and NUAK2.

Conclusion

NUAK1 and NUAK2 expression patterns are useful for predicting clinical features of a broad range of cancers and some fibrotic diseases, highlighting their hypothetical utility as emerging prognostic biomarkers in a group of malignancies which remain largely incurable. NUAK1 and NUAK2 signaling in preclinical models reveal several similarities between the two kinases in cancer biology, including ECM remodeling, response to oxidative stress, and EMT. Meanwhile, in inflammatory and fibrotic diseases, NUAK1 is a proposed mediator of gastric inflammation and organ fibrosis, but more research is required to determine a role for NUAK2, if any, in these contexts. In addition, the inhibition of NUAK1 and NUAK2 with small-molecule inhibitors has proven useful in a range of preclinical models of cancer and some fibrosis murine models, with improved chemical probes in development for future use. Further optimization of NUAK inhibitors into chemical probes for the NUAK kinases to improve selectivity, toxicity profile, oral availability, and blood-brain barrier permeability will yield invaluable tools to study the NUAK kinases in preclinical and clinical models. To date, a gap exists between functional studies on NUAK1 and NUAK2, with NUAK2 remaining less studied than NUAK1 in the context of disease. NUAK1 is the only NUAK kinase whose inhibition is currently pursued in cancer clinical trials via the multikinase inhibitor ON123300, thus revealing the untapped potential of NUAK inhibitors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Figures were created with Biorender.com. We are grateful to Krewe de Pink, an organization of breast cancer survivors, their families, and community members based in New Orleans who are devoted to supporting local breast cancer research.

Author contributions

N. M. C., P. R., B. T., A. E. D, A. P., D. H. K., and B. M. C.-B. writing–original draft; V. T. H., E. C. M., D. H. B., M. E. B., and S. K. A. writing–review and editing; M. E. B. and S. K. A. conceptualization; M. E. B. and S. K. A. supervision.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by NIH Grants 1R01CA174785-01A1, 1R01CA273095-01, U24DK116204, and U54 GM104940, Fred G. Brazda Foundation, and Louisiana Cancer Research Consortium grants to S. K. A. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Brian D. Strahl

Contributor Information

Matthew E. Burow, Email: mburow@tulane.edu.

Suresh K. Alahari, Email: salaha@lsuhsc.edu.

References

- 1.Hardie D.G., Carling D., Carlson M., Hardie D.G., Carling D., Carlson M. The AMP-ACTIVATED/SNF1 PROTEIN KINASE SUBFAMILY: metabolic sensors of the eukaryotic cell? Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:821–855. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.T W., JE B. LKB1 and AMPK in cell polarity and division. Trends Cell Bio. 2008;18:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki A., Kusakai G.-i., Kishimoto A., Lu J., Ogura T., Lavin M.F., et al. Identification of a novel protein kinase mediating akt survival signaling to the ATM protein ∗. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(1):48–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skalka G.L., Whyte D., Lubawska Dominika, Murphy Daniel J. NUAK: never underestimate a kinase. Essays Biochem. 2024;68:295–307. doi: 10.1042/EBC20240005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manning G., Whyte D.B., Martinez R., Hunter T., Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee S., Zagórska A., Deak M., Campbell D.G., Prescott A.R., Alessi D.R. Interplay between Polo kinase, LKB1-activated NUAK1 kinase, PP1βMYPT1 phosphatase complex and the SCFβTrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase. Biochem. J. 2014;461:233–245. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bright N.J., Thornton C., Carling D. The regulation and function of mammalian AMPK-related kinases. Acta Physiol. 2009;196:15–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaleel M., Villa F., Deak M., Toth R., Prescott A.R., van Aalten D.M.F., et al. The ubiquitin-associated domain of AMPK-related kinases regulates conformation and LKB1-mediated phosphorylation and activation. Biochem. J. 2006;394:545–555. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas D Mueller J.F. Solution structures of UBA domains reveal a conserved hydrophobic surface for protein-protein interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;319:1234–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anna Zagórska M.D., Campbell D.G., Banerjee S., Hirano M., Aizawa S., Prescott A.R., et al. New roles for the LKB1-NUAK pathway in controlling myosin phosphatase complexes and cell adhesion. Sci. Signal. 2010;3:ra25. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000616. ra25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faisal M.e. a. Development and therapeutic potential of NUAKs inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2021;64:2–25. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]