Abstract

Background and Aims

The cultivation of Miscanthus, a giant perennial grass and promising biomass crop, is expected to increase globally in response to climate mitigation policies and sustainable agriculture goals. Little is known about root carbon (C) exudation and fine root architecture or how this might differ between Miscanthus species. To understand the functional biology of three diverse Miscanthus species and to evaluate impacts on soil C cycling, the aim of this study was to quantify root C exudation rates and track fine root growth.

Methods

We use a controlled environment with plants grown in rhizotron boxes (28 L) to quantify living root C exudation rates and fine root growth of Miscanthus sacchariflorus, M. sinensis and M. × giganteus. Weekly non-destructive images of visible roots were analysed for root length density and root diameter during the growing season. Above- and below-ground biomass and C and nitrogen content were also recorded immediately after exudate sampling.

Key Results

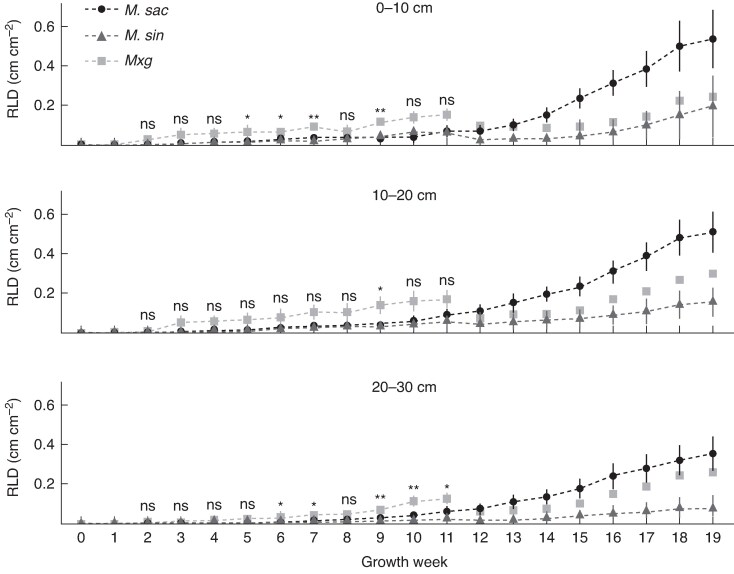

The exudation rate was significantly lower for M. sacchariflorus compared with M. sinensis and M. × giganteus (0.0 versus 0.6 g C g−1 root dry mass year−1). Coupled with this, M. sacchariflorus had greater above-ground biomass, a smaller increase in root mass and a higher root C concentration. Rapid root growth was observed, especially for M. × giganteus, for which root length density (0–30 cm depth) was higher compared with both M. sacchariflorus and M. sinensis in the earlier growth weeks.

Conclusions

The results reveal a possible fundamental difference in nutrient resource acquisition and allocation between M. sacchariflorus versus M. sinensis and M. × giganteus. We estimate that Miscanthus root C exudation could add up to 2 g C kg−1 soil month−1 (during the peak growing season), a considerable influx of new labile C. This unique insight into differences in Miscanthus exudation indicates the potential for targeting Miscanthus breeding for enhanced soil C sequestration.

Keywords: Miscanthus, root exudates, soil carbon, root architecture, Miscanthus sacchariflorus, Miscanthus sinensis

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

The cultivation of the biomass crop Miscanthus (a giant perennial grass) is expected to increase globally in response to climate mitigation policies (Calvin et al., 2021; Clifton-Brown et al., 2023). Miscanthus is an attractive crop owing to its rapid biomass growth, soil carbon (C) benefits and potential to achieve negative greenhouse gas emissions (e.g. if plant fixed C is embedded in products, increases soil C stocks or if emissions released during combustion are stored geologically through carbon capture and storage) (Robson et al., 2019; Shepherd et al., 2020; Iordan et al., 2023). The protection and increase of soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestered in agricultural soils is vital in climate mitigation strategies and sustainable agriculture (Bossio et al., 2020; Wiese et al., 2021).

Plant root characteristics are a pivotal part of soil ecosystem processes. Different architectural (rooting depth and density), morphological (root diameter and specific root length), physiological (root respiration and exudation) and biotic (interactions with microorganisms) root traits of diverse plant species, interacting with various soil types, uniquely shape the rhizosphere (Bardgett et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2022). In particular, rhizodeposits of insoluble exudates of high molecular weight (e.g. border cells, mucilage) and soluble exudates of low molecular weight (e.g. sugars, amino acids) are at the interface of bi-directional soil–root interactions (Jones et al., 2009). These root exudates provide several benefits to plants, including improved health and resilience, which, in turn, can enhance sustainable agricultural systems (Huang et al., 2014) and play a key role in soil C cycling processes (Panchal et al., 2022).

Root turnover and root exudates (along with inputs from the decomposition of above-ground plant residues) are primary pathways for atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), fixed through photosynthesis, to enter the soil C cycle (Kumar et al., 2006; De Deyn et al., 2008). Roots promote SOC stabilization through inputs of new labile C easily transformed into microbial products and subsequently sorbed onto soil minerals, and the formation of soil aggregates. Conversely, roots also contribute to SOC destabilization through: new inputs stimulating microbial activity that promote the use of existing C (known as priming; Kuzyakov et al., 2000); organic acids chemically freeing previously bound C; and the destruction of aggregates exposing C to decomposition (Dijkstra et al., 2021). Depending on exudate composition and soil conditions, root exudation can have contrasting effects for SOC sequestration, in some circumstances facilitating the accumulation of SOC and in others accelerating SOC loss (Wen et al., 2022a).

Although part of the plant fixed C allocated to roots is released as CO2 from root and microbial respiration (Freschet et al., 2021), root turnover and exudates from Miscanthus are estimated to account for ∼68 % of soil C input (Bertola et al., 2024). However, owing to a lack of empirical data, SOC models generally rely on allometric functions of C inputs from Miscanthus roots, e.g. using functions relating to soil nitrogen (N) levels and root biomass (Juice et al., 2022) or equations based on above-ground harvest yields and estimations of below-ground biomass (Bertola et al., 2024).

Root exudates also promote plant acquisition of nutrients through the recruitment of beneficial microbes and the supply of fresh C, encouraging microbial growth and the subsequent mineralization of organic N and availability of soluble phosphorus (P) and iron (Fe) (Pantigoso et al., 2022). It has been proposed that plants with thinner roots effectively search the soil for nutrients, whereas plants with thicker roots use symbiotic relationships with mycorrhizal fungi to a greater extent (Bergmann et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2022b). It has been found that plants can also adjust the chemistry of exudates to aid in adapting to various rhizosphere conditions and biotic and abiotic stresses (Sun et al., 2021; Ahlawat et al., 2024). Root exudation therefore drives the composition and function of soil microbial communities, regulates soil biogeochemical cycles, and can modify soil structure.

Additionally, the C supplied from plants to the soil via root exudates is also influenced by root traits. For example, exudation from fine roots (≤2 mm) is generally higher than from thicker coarse roots (>2 mm), and therefore the large pulses from smaller-diameter roots are likely to travel further into the soil (Finzi et al., 2015). Deeper-rooting plants have the potential to impact SOC at lower soil depths, where exudates of similar composition can affect SOC in different ways owing to differences in soil conditions (de Graaff et al., 2014; Lei et al., 2023).

Specific root length (SRL; the length of root per unit of dry mass) is an indicator of the potential nutrient acquisition area per cost of biomass and is associated with root lifespan and decomposition rate (Freschet et al., 2021). The relationship between SRL and decomposition varies from being positive for grasses to non-significant or negative for herbaceous and woody plants (Poirier et al., 2018). Variation in component traits of root tissue density (RTD; the root volume per unit of dry mass) and root diameter account for variation in SRL (Freschet et al., 2021). Fine roots are characterized by a low RTD and high SRL, and the distribution of roots within fine root diameter classes indicates root morphological diversity (Liu et al., 2018; Erktan et al., 2023). Roots <1 mm in diameter encourage the formation of macroaggregates within the soil matrix, aiding the short-term (years to decades) occlusion of soil organic matter (SOM) and promoting stabilized SOM via microaggregation (Poirier et al., 2018).

In addition to variation attributable to plant developmental stage, plant health, season and time of day (Badri and Vivanco, 2009; Chaparro et al., 2013; Rathore et al., 2023) root exudation can differ by and within plant species (Mönchgesang et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2024). Therefore, it is important to understand the rhizosphere C inputs of novel crop types and the potential impact on C cycling.

The genus Miscanthus includes a number of species. The common commercial variety grown as a biomass crop for bioenergy and bioproducts (Brosse et al., 2012; Arnoult and Brancourt-Hulmel, 2015; Moll et al., 2020) is Miscanthus × giganteus (M. × g) (Greef and Deuter, 1993), with a potential commercial lifespan of ∼20 years (Winkler et al., 2020). Miscanthus × giganteus is a natural hybrid of M. sacchariflorus and M. sinensis (Lewandowski et al., 2000). Additionally, new crosses are being bred for improved resilience and harvest yields, capturing the benefits from this wide-ranging species (Awty-Carroll et al., 2023).

Aboveground, M. sinensis species typically have multiple thin stems, whereas M. sacchariflorus are generally taller (∼2 m), with fewer and thicker stems (Robson et al., 2013; Chae et al., 2014). Underground, Miscanthus has a substantial root and rhizome system. Miscanthus sinensis species tend to have smaller rhizomes, with less of a creeping habit in comparison to M. sacchariflorus, which preferentially spreads laterally with chunky, thick-stemmed rhizomes (Chae et al., 2014; Richter et al., 2015). Miscanthus × giganteus is closer to the M. sacchariflorus form, with rhizome portions from established plants spreading into an area of ∼0.5 m2 once mature (∼3 years old) (McCalmont et al., 2015).

As a rhizomatous plant, Miscanthus partitions C and nutrients from above-ground biomass to below-ground organs, sustaining growth and aiding with abiotic stress (Anderson et al., 2011). The C:N ratios for M. × g roots and rhizome are in the region of ∼20 to ∼40 (Beuch et al., 2000; Kahle et al., 2001; Amougou et al., 2011), although values have been observed to vary widely in M. sacchariflorus species (Poeplau et al., 2019). In incubation experiments, M. × g roots are mineralized at a slower rate than rhizome, and this slower rate of decomposition could help to maintain SOC stocks (Beuch et al., 2000; Amougou et al., 2011; Ferrarini et al., 2022).

Although deep rooting (≤2 m for M. × g; Neukirchen et al., 1999), most of the below-ground biomass is found in the top 0.5 m of soil for all Miscanthus species (Hansen et al., 2004; Richter et al., 2015). In field conditions, RLD (in centimetres per centimetre cubed) for M. × g (6 years old) reduces with soil depth: 8–10 (0–10 cm depth); 4–6 (10–30 cm depth); 1–4 (30–60 cm depth); and 0–1 (60–100 cm depth) (Chimento and Amaducci, 2015; Gregory et al., 2018). RLD for M. sinensis plants (of a similar age) also reduces with depth but was found to be higher throughout the profile: 12 (0–10 cm); 8 (10–30 cm); 3 (30–60 cm); and 2 (60–100 cm) (Gregory et al., 2018). Mean root diameter for M. × g has been documented at 0.55 mm, in comparison to 0.47 mm for M. sinensis (Gregory et al., 2018).

The knowledge base relating to root exudation and the fine root architecture of Miscanthus is small and relates predominantly to M. × g. Root C exudation rates have been recorded in the region of 2 mg C g−1 root dry mass (Md) day−1 for M. × g (Kaňova et al., 2010; von Haden et al., 2024), which could supply between 0.4 and 1.7 Mg C ha−1 year−1 (Agostini et al., 2015) to the soil system. The exudates comprise assimilable organic C in the form of sugars, organic acids and amino acids, with the potential to increase soil heterotrophic respiration (Kaňova et al., 2010; Hromádko et al., 2010). However, in a comparison of annual and perennial crops (including M. × g) it was found that the lower exudation rate from perennials increased C and N mineralization from bulk soil organic matter, which might promote SOC sequestration over any losses from exudate priming (von Haden et al., 2024). Differences in Miscanthus species root architecture and morphology conceivably impact on root exudation and turnover but, to our knowledge, there are no reports of root exudation rates for Miscanthus species other than M. × g. However, variation in SOC sequestration rates has been noted within Miscanthus species and hybrids (Zatta et al., 2014; Gregory et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2020), and a positive relationship has been established between below-ground biomass and Miscanthus-derived SOC (Zatta et al., 2014; Richter et al., 2015).

Therefore, defining how Miscanthus species differ in terms of root exudation and fine root architecture and morphology is needed to understand the functional biology of this diverse species, to evaluate the potential impacts on SOC cycling and to inform modelled representations of plant carbon inputs. In this study, three Miscanthus genotypes were selected as representative of two broad Miscanthus species (M. sacchariflorus and M. sinensis) along with the hybrid, M. × g. The species were chosen because they are standard exemplar clones of parental species types of the commercial interspecific hybrid M. × g. A controlled environment experiment is used to address the following research questions and consider the potential implications for SOC sequestration:

Do Miscanthus species differentially affect the root exudation rate?

Are differences in root exudation explained by above- or below-ground biomass?

How do Miscanthus root growth traits differ between species?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The three Miscanthus genotypes used were M. sacchariflorus (M. sac), M. sinensis ‘Goliath’ (M. sin), and M. × giganteus (M. × g). The M. sac is a selection from wild-sourced Japanese M. sacchariflorus from Shikoku island and is a similar type to the M. sacchariflorus parent that created the standard M. × g. Goliath (M. sinensis, cv. Goliath) is officially origin unknown. It is likely to have been selected from an open pollination from a maternal tetraploid and a paternal diploid, both M. sinensis. Miscanthus × giganteus (Greef and Deuter, 1993; Stewart et al., 2009), which is standard commercial Miscanthus, is an open pollinated hybrid of tetraploid M. sacchariflorus and M. sinensis (Linde-Laursen, 1993).

To obtain small plants of a comparable size, rhizomes from 10-year-old field grown M. sac, M. sin and M. × g were dug, split and pared back to one viable bud during early spring and planted into 1 L pots (using a John Innes No. 3 compost and perlite mix). Plants were grown on in a polytunnel until the next spring, when the senesced above-ground growth was cut and removed and the plants were gently washed from the pots. In March, five replicates of each species (M. sac, M. sin and M. × g) were transplanted into custom-made rhizotrons (root boxes constructed from a wooden frame and two sheets of 3-mm-thick Perspex, measuring 60 cm × 46 cm × 10 cm, ∼28 L; Supplementary Data Fig. S1). Prior to planting, the rhizotrons were filled with horticultural silver sand mixed with 250 g of a granular nutrient base fertilizer (5.5 N 7.5 P 10 K plus trace elements; Vitax Ltd, Coalville, UK). A further 10 g of fertilizer (mixed with sand) was added in June. The Perspex sides were covered with black plastic sheeting and surrounded with a layer of reflective insulation material. Rhizotrons were arranged in a random layout within a controlled-environment glasshouse setting, with natural light from above and growing conditions representing a temperate climate (Fig. 1). Rhizotrons were equipped with an automatic dripper watering system, with additional top-up watering done by hand, according to need. In mid-May, three M. sin and four M. × g dead plants were replaced with spares.

Fig. 1.

Glasshouse growing conditions from March to August: mean light [photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD], air temperature (in degrees Celsius) and relative humidity (RH, as a percentage). Vertical dotted lines indicate the root exudate sampling period.

Root exudate collection and analysis

Root exudates were sampled at the beginning of August from each of the plants, using a method based on and adapted from Phillips et al. (2008) and Sun et al. (2017). Rhizotrons were tipped at an angle of ∼60° and one side of the rhizotron Perspex was removed. Intact root portions were carefully extracted and cleaned with the aid of a wash bottle containing ultrapure water (PURELAB Classic, ELGA, UK). Root portions remained attached to the living plants throughout the sampling process.

The root portions were placed inside a 30 mL incubation tube (syringe) containing a small mesh circle (mesh size 0.8 mm × 0.8 mm, polyethylene) to retain ∼5 mL of new 1.0–1.3 mm glass beads (from falling into the tube outlet). The incubation tube was attached to a 40 mL collection vial using a length of tubing and a needle (Supplementary Data Fig. S2). After backfilling the incubation tube with beads, 10 mL of a C-free nutrient solution was added [0.5 mm NH4NO3 (ammonium nitrate), 0.1 mm KH2PO4 (potassium dihydrogen phosphate), 0.2 mm K2SO4 (potassium sulphate), 0.2 mm MgSO4 (magnesium sulphate) and 0.3 mm CaCl2 (calcium chloride); Phillips et al., 2008]. The incubation tube was then sealed using a slit synthetic rubber stopper and parafilm. After securing the incubation tube to the rhizotron (avoiding injury/strain to the roots), the syringe, collection vial and rhizotron were covered with damp cloths and aluminium foil. The rhizotron was then covered with a sheet of black plastic and the roots incubated for 24 h (to allow for diurnal changes in exudation rates). Two root portions were incubated per plant (the average of the two used to provide one value per rhizotron). On each sampling occasion, three blanks were also incubated.

Following the incubation period, a second syringe was inserted into the collection vial and used as a pump to pull the liquid sample from the incubation tube. Two measures of 10 mL C-free nutrient solution were added to the incubation tube and pulled through to the collection vial. Then the solution in the collection vial was immediately transferred, through a 0.22 µm syringe filter, to a sample storage vial and kept cool until placed in a freezer (−20 °C) for storage until analysis. After retrieval of the solute sample, the incubated root portions were cut from the plant and measured for length. The root portions were then oven dried (60 °C) and weighed to obtain dry mass (Md). The RTD (using root dry matter content, according to Birouste et al., 2014) and SRL were calculated for the incubated root portions using eqns (1) and (2).

| (1) |

| (2) |

The total organic C (TOC) content of the solute samples was analysed using an Aurora 1030W TOC Analyser (OI Analytical, TX, USA). The mean TOC content of the blanks was subtracted from the TOC content for each sample prior to calculating the hourly root exudation rate (eqn 3). In a few instances, the blank C value was higher than the root sample C value, hence TOC was set to zero (von Haden et al., 2024).

| (3) |

The yearly root exudation rate (in grams of carbon per gram root dry mass per year) was calculated in a similar way, using a period of 210 days to represent the full growing season (Agostini et al., 2015).

Above- and below-ground biomass

Immediately following the exudate sampling, the above-ground biomass was cut off at 2.5 cm above the sand surface, and the remainder of the below-ground biomass was washed and divided into root and rhizome. The root mass was separated further into new (white/red) and old (brown) root by colour. Above- and below-ground biomass was then oven dried (60 °C) and the fresh (Mf) and Md weights were recorded.

C and N analysis

C and N analysis was carried out on the dried and ball-milled (Labman automated preparation system) new roots and above-ground leaves using an ANCA-SL elemental analyser (Sercon Ltd, Crewe, UK).

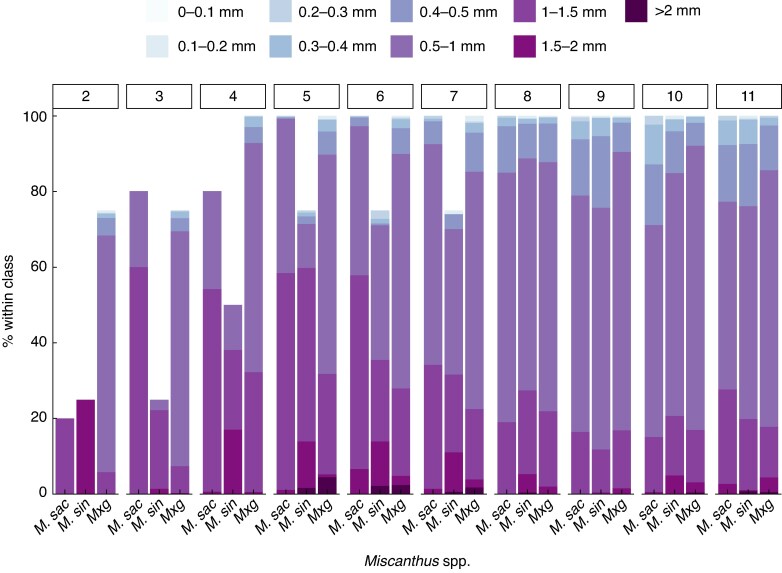

Determination of root growth

For the duration of the study, non-destructive root growth and diameter were tracked weekly by removing the rhizotron outer coverings, placing a camera in a marked position and (using the same camera zoom settings) photographing the roots visible on one side of the Perspex. The digital photographs were then analysed for root length and diameter in 10 cm depth increments (0–10, 10–20, 20–30, 30–40, 40–50 and 50–60 cm) using the SmartRoot plug-in program (Lobet et al., 2011) for ImageJ software (v.53; Rasband, 2022). Examples of roots traced using the SmartRoot plug-in are shown in the Supplementary Data (Figures S6-S8). Root length density (RLD, in centimetres per centimetre squared) was calculated as visible root length divided by image frame area. The variation in root diameter was classified by the percentage root length observed within nine diameter classes (in millimetres: 0–0.1, 0.1–0.2, 0.2–0.3, 0.3–0.4, 0.4–0.5, 0.5–1, 1–1.5, 1.5–2 and 2+), in addition to the percentage above and below 0.5 mm (Liu et al., 2018). Concurrent measurements of above-ground growth were also taken (number of stems and height of the tallest stem to the top ligule).

Statistical analysis

All ‘±’ errors reported are the s.e.m. Data analysis was carried out in R v.4.2.3 (R Core Team, 2023). Differences in the exudation rate and biomass data (as shown in Table 1) were explored using one-way ANOVAs and Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests (package ‘multcomp’; Hothorn et al., 2008). The exudate data were log-transformed to improve normality of the model residuals.

Table 1.

Mean values for biomass traits from the three Miscanthus species (M. sac, M. sin and M. × g) grown in the rhizotrons from March to August (n shows the number of observations, ±s.e., and different superscript letters denote statistical significance following Tukey’s post hoc tests; ns, not significant)

| Species | n | No. of growth weeks | AG biomass | Stem height | No. stems | Leaf C % |

Leaf C:N |

Rhizome mass | Root mass (old) | Root mass (new) |

Root C (new) % |

Root (new) C:N |

RTD | SRL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. sac | 5 | 19 | 18.34 ± 4.16a | 106.3 ± 5.3a | 6 ± 1.1b | 42.5 ns ±0.4 |

19.5 ± 1.0a | 16.01 ns ± 3.85 | 3.41 ± 1.00b | 4.62 ns ±0.78 |

40.5±0.7a | 46.7 ns ±2.3 |

0.19 ns ±0.04 |

857 ns ±162 |

| M. sin | 4 | 15 | 06.03 ± 1.98b | 061.9 ± 13.8b | 3 ± 1.0a | 41.8 ns ±0.2 |

26.5 ± 2.4b | 09.00 ns ± 2.16 | 0.49 ± 0.20a | 2.93 ns ±0.27 |

32.2 ± 1.8b | 39.2 ns ±6.0 |

0.10 ns ±0.00 |

1056 ns ±402 |

| M. × g | 5 | 13 | 10.74 ± 1.20ab | 108.6 ± 8.4a | 3 ± 0.3a | 42.1 ns ±0.4 |

21.9 ± 2.5ab | 09.00 ns ± 2.57 | 0.74 ± 0.15a | 3.46 ns ±1.61 |

34.7 ± 1.6b | 39.7 ns ±2.5 |

0.11 ns ±0.01 |

929 ns ±99 |

The mean growth weeks for plants in the rhizotrons differ owing to the replacement of dead plants. Above-ground (AG) biomass includes all stems and leaves (Md, in grams). Stem height (in centimetres) is the height of the tallest stem taken to the top ligule. The leaf carbon content (C %) and carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C:N) relate to leaf subsamples taken from the AG biomass. Total plant rhizome mass and root mass (Md, in grams) relate to the biomass harvested after the collection of root exudates. New and old root mass was separated by appearance. Root C content (C %) and C:N relate to the new root portions. Root tissue density (RTD) and specific root length (SRL, in grams per centimetre) are described in the Materials and Methods and were calculated for the root portions incubated for the exudate sampling.

Growth weeks from 2 (i.e. 14 days since planting) to 11 were used to compare differences in RLD and root diameter (obtained from image analysis) over the experimental period. Owing to the replacement of dead plants, there were insufficient replicates in all species to compare by later growth weeks. RLD was analysed separately using one-way ANOVAs and Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests for each growth week and 10 cm depth segment. A square transformation was used with the 0–10 cm depth segment in growth week 2 to meet model assumption criteria. The percentage root length within each of the nine diameter classes was analysed using separate general linear mixed models (package ‘glmmTMB’; Brooks et al., 2017) for each growth week, with species (M. × g, M. sac and M. sin) as the fixed factor and a beta distribution. Diameter classes above and below 0.5 mm were also explored using general linear models, with the fixed factors (and their interactions) of species and class (0–0.5 mm and 0.5–2+ mm) and a beta distribution. Results were summarized with ANOVA type 2 and type 3 sums of squares (package ‘car’; Fox and Weisberg, 2019), as appropriate, and Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests.

RESULTS

Root carbon exudation rates

There was a distinct variation between the C exudation from the M. sac roots, in contrast to M. sin and M. × g. The M. sac exudation rate (in milligrams of carbon per gram root dry matter per hour) of 0.002 ± 0.002 was significantly lower (F2,11 = 7.46, P < 0.01) than both M. sin (0.115 ± 0.031) and M. × g (0.126 ± 0.036) (Fig. 2). When calculated on a yearly basis (in grams of carbon per gram root dry matter per year, based on a 210-day growing season) exudation rates were 0.010 ± 0.010 (M. sac) 0.583 ± 0.158 (M. sin) and 0.636 ± 0.182 (M. × g). Root biomass for M. × g was higher than for M. sin (Table 1); therefore, whole-plant root C exudation from M. × g was ∼30 % higher compared with M. sin (2.67 versus 1.99 g C per plant year−1 for M. × g and M. sin, respectively). Whole-plant root C exudation was 0.08 g C per plant year−1 for M. sac.

Fig. 2.

Hourly root exudation rates for each Miscanthus species (M. sac, M. sin and M. × g) grown in the rhizotrons, and calculated from living root portions incubated over a 24-h period. The asterisk denotes the sample mean (in milligrams of carbon per gram root dry mass per hour: 0.002, n = 5, M. sac; 0.115, n = 4, M. sin; 0.126, n = 5, M. × g), and the median is shown by the bar (0.000 M. sac; 0.131 M. sin; 0.108 M. × g).

Above- and below-ground biomass

Despite a clear difference in the root C exuded between M. sac and the remaining two species, leaf C content was similar (Table 1). However, the C content of new roots was higher for M. sac compared with M. sin and M. × g (F2,11 = 9.63 P = 0.00; Table 1). There was no statistical difference in the root C:N ratio, but the leaf C:N ratio was higher for M. sin compared with M. sac (F2,11 = 4.40 P = 0.04), resulting from a lower leaf N content (Table 1). Stem height was significantly higher for M. sac and M. × g compared with M. sin at the end of the experimental period (F2,11 = 7.74, P = 0.00), and M. sac had a greater number of stems (F2,11 = 5.76, P = 0.02) (Table 1). Above-ground biomass was therefore greater for M. sac compared with M. sin, but not M. × g (F2,11 = 5.48, P = 0.04; Table 1). All the plants were within an establishment phase during the experiment, hence no flowering occurred.

There was no significant difference between the total root mass (old plus new) or the new root mass for each species. However, compared with the older root mass, new root mass increased by a higher percentage for M. sin and M. × g (35 % M. sac; 498 % M. sin; 368 % M. × g). Although total rhizome mass was generally higher for M. sac, variation between replicates meant that this was not significantly different from the other two species. At this young plant age, total below-ground biomass (rhizome and root) was greater than the total above-ground biomass (stems and leaves) for all three species. The total above- to below-ground biomass ratio was highest for M. sac and lowest for M. sin (0.8, 0.5 and 0.6 for M. sac, M. sin and M. × g, respectively).

Root growth traits

Analysis of the root images showed that roots were first visible in the lowest 50–60 cm depth segment for M. × g and M. sin plants in growth week 6, and for M. sac in growth week 7. Although there was no statistical difference in RLD in the visible roots below 30 cm depth, in the upper 0–30 cm segments RLD for M. × g was higher for a number of the earlier growth weeks (weeks 5, 6, 7 and 9 in the 0–10 cm segment; week 9 in the 10–20 cm segment; and weeks 6, 7, 9, 10 and 11 in the 20–30 cm segment) (Fig. 3). After growth week 11, higher RLD was observed for M. sac compared with M. × g and M. sin, but statistical analysis was not possible for the later growth weeks because only one M. × g plant survived the full 19 weeks of the experimental period.

Fig. 3.

A comparison of mean root length density (RLD, as observed via the rhizotron) by growth week (number of weeks after planting) and depth segment (0–10, 10–20 and 20–30 cm). Error bars represent the s.e. and asterisks the significance level (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, not significant). For M. sac n = 5, M. sin n = 4 and M. × g n = 5, for growth weeks 0–11. Owing to the replacement of dead plants, only one M. × g plant was measured for 19 weeks.

It was observed during the exudate sampling that the M. sin roots were brittle and proved more difficult to extract than the M. sac and M. × g roots. Miscanthus sacchariflorus had the highest RTD and lowest SRL of the incubated root portions, but neither of these traits was significantly different by species (Table 1). Image analysis showed no discernible pattern of species differences in the percentage of visible root within each individual diameter class (Fig. 4). However, from growth weeks 3 to 11, the majority of roots were observed within classes above 0.5 mm [χ2(1) = 7.69, P < 0.01; χ2(1) = 8.61, P < 0.01; χ2(1) = 22.24, P < 0.001; χ2(1) = 22.66, P < 0.001; χ2(1) = 11.92, P < 0.001; χ2(1) = 49.25, P < 0.001; χ2(1) = 24.90, P < 0.001; χ2(1) = 21.20, P < 0.001; χ2(1) = 27.95, P < 0.001, for growth weeks 3–11, respectively], although only a small percentage of roots were observed above 1.5 mm (Fig. 4). In the root images, the thicker exploratory/nutrient transport roots were observed first, with thinner secondary branching roots increasing in later growth weeks (Fig. 4). All three species mainly exhibited a herringbone root structure with some dichotomous branching, and emerging M. sac rhizomes tended to spread laterally through the soil, whereas M. sin rhizomes formed closer together, in a clump (Supplementary Data Figs S3–S5).

Fig. 4.

Mean percentage of visible root within nine diameter classes (in millimetres) for each species (M. sac n = 5, M. sin n = 4 and M. × g n = 5) and growth week (number of weeks after planting), based on image analysis.

DISCUSSION

Differences in root C exudation

In this study, we have shown that not all Miscanthus species are the same in terms of root C exudation. Although the recorded exudation rates (from live plants) were within the expected region (∼0.5 g C g−1 root Md year−1, based on Kaňova et al., 2010) there was significant variation in the rate for M. sac compared with M. sin and M. × g (0.0 versus 0.6 g C g−1 root Md year−1). This suggests that M. sac might retain more C for internal use with a more conservative resource acquisition strategy (e.g. an efficient use of assimilated C and/or utilizing different symbiotic relationships with soil microorganisms). Other research has found the soil microbial community to differ for an M. sacchariflorus species compared with M. sinensis and M. floridulus species, whereby M. sacchariflorus had the lowest diversity of soil bacteria and fungi and the greatest difference in fungal community composition (Chen et al., 2020).

The M. × g root C exudation rate recorded here was comparable to that of M. sin, leading to questions of the parental contribution to this physiological trait. Although in the hybrid it is assumed that the M. sacchariflorus genome is much larger and therefore will be likely to dominate the hybrid, phenotype studies have shown that, for example in Japan, M. sinensis and M. sacchariflorus grow in similar areas, and among the phenotypically M. sacchariflorus tetraploids, M. sinensis ancestry averaged 7 % and ranged from 1 to 39 % (Clark et al., 2015). In terms of phenotype, several manuscripts have compared Miscanthus species with the M. × giganteus hybrid. There is no particular consensus regarding the dominance of the larger M. sacchariflorus genome. For example, the stem basal diameter (Robson et al., 2013) and canopy senescence (Robson et al., 2012) phenotypes of the hybrid lie between those of the two parental species groups. For other traits, there appears to be a transgressive segregation including tallest stem and dry matter yield, with the hybrid producing longer stems and higher yield (Robson et al., 2013). In a study of cell wall chemistry, M. × giganteus contained significantly more cellulose and lignin and less hemicellulose compared with M. sacchariflorus or M. sinensis (Allison et al., 2011). Differences were detected in how the cell wall components correlated with each other, suggesting that in M. × giganteus the cell wall is somehow regulated differently compared with M. sinensis and M. sacchariflorus. The complexity of trait associations is illustrated by an interesting study that appeared to show a seasonal switch in the biochemical response of the hybrid to temperature. Miscanthus × giganteus had intermediate behaviour, with characteristics of both chilling-tolerant and chilling-sensitive genotypes depending on seasonal timings, but sensitivity and tolerance were not linked to parental species groups in that study (Fonteyne et al., 2018).

Exudation rates are likely to vary between and within growing seasons, depending on plant growth stage, age and other environmental factors, such as climate and soil conditions (Badri and Vivanco, 2009; Vives-Peris et al., 2020). Exudate rates can also alter depending on soil or plant nutrient status (Jing et al., 2023) and, given that sufficient nutrients were added to the growing medium, it might be that the M. sac rate was lower owing to a response to growing conditions not seen in M. sin and M. × g. However, to consider this possible effect, further investigation with different levels of N addition would be required.

The exudates in this experiment were measured from young plants with new roots, although the exudation rate for M. × g in this study (0.13 mg C g−1 h−1) was comparable to a previously recorded rate of 0.19 mg C g−1 h−1 obtained from 15-year-old field-grown plants (Kaňova et al., 2010). However, the method of collection of root exudates differs between these two studies, and the slightly higher figure recorded by Kaňova et al. (2010) might be attributable to the sampling technique, where exudation was sampled using roots cut from the plant, potentially increasing the discharge of C compounds.

The root exudates were sampled at the point of peak plant growth for all the plants, and therefore the yearly exudation rate (calculated assuming the same rate for the whole growing season) provides an estimate at the top end of potential C inputs to the soil system. Exudation rates sampled from a field trial (on four occasions, and over 2 years, from 10-year-old M. × g plants) have been shown to differ greatly, whereby, although rates increased from July to August in both years, the scale of change varied between years, possibly reflecting differences in plant growth attributable to meteorological conditions (von Haden et al., 2024). The two rates recorded by von Haden et al. (2024) during the month of August were 2.15 and 0.94 mg C g−1 root Md day−1, both lower than the equivalent rate recorded in this study for M. × g (3.02 mg C g−1 root Md day−1), where the plants were grown in optimal conditions.

Variation in Miscanthus biomass and root growth traits

In light of the low M. sac exudation rate and in support of the possibility that M. sac was retaining C resources to support greater biomass growth, it was found that M. sac had a higher root C content compared with both M. sin and M. × g. Miscanthus sac also had the highest SRL and lowest RTD of the incubated root segments, which, although not significant, are traits that have been associated with low root exudation (Guyonnet et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2022).

Typically, in other grass species, there is a reliance on short-lived absorptive roots to facilitate responsive soil exploration and provide a greater surface area for nutrient uptake, whereas forbs and shrubs exhibit dichotomous branching, with several root orders comprising thin absorptive (in the range of 0 to ∼0.5 mm diameter) and thicker transport roots (between ∼0.25 and ∼1 mm diameter) (Bergmann et al., 2020; Erktan et al., 2023). The plants in this study contained both root types, with a dominance of roots between 0.5 and 1.5 mm. However, they represent developing root systems and, for each of the three species, although transport roots were visible in the rhizotron images first, this was followed by an increase in absorptive roots. A greater diversity of root diameter class and species difference can be expected as the plants mature (Gregory et al., 2018) and can also alter in response to soil nutrient status (Erktan et al., 2023). In accordance with the anticipated growth habit of established plants, emerging M. sac rhizomes spread laterally through the soil, whereas M. sin formed a denser clump. The lower stem height for M. sin also reflects the nature of the mature plant, where numerous shorter stems would be expected. The brittleness of M. sin roots was noted, which might indicate a shorter lifespan or might be a result of growing conditions (e.g. root zone moisture levels). However, the rhizotrons were automatically watered to keep the growing medium (sand) moist, and top-up watering was carried out manually only when required.

Rapid root growth was observed for all three species, with roots visible in the lowest rhizotron depth of 50–60 cm around growth week 6, and by the end of the study the root growth of most of the plants was restricted by the size of the rhizotron (60 cm × 46 cm × 10 cm). RLD was highest for M. × g in the 0–30 cm depth in the early growth weeks, which might have been impacted by the warmer air temperatures experienced by the four plants replaced in May compared with those planted in mid-March. However, rapid development of M. × g roots has also been observed with young field-grown plants (Black et al., 2017; Holder et al., 2025), and three M. sin plants were also replaced at the same time. New root mass increased more for M. sin and M. × g, whereas the higher above-ground biomass for M. sac suggests a concentration of resources on above-ground growth at this stage.

Implications for soil organic carbon sequestration

Similar to an estimated C input from grass pasture root exudation (0.1–5 g C kg−1 soil month−1, Lolium perenne; Jones et al., 2009), the exudation rate of 3 mg C g−1 root Md day−1 (M. sin and M. × g) recorded in this study could potentially add 0.1–2 g C kg−1 soil month−1 to the soil system during the peak growing season [based on root biomass of 5–21 Mg ha−1 (Monti and Zatta, 2009; Martani et al., 2021) and calculated to a soil depth of 0.6 m using an average soil bulk density of 1.4 g cm3]. An estimated 20 % of total soil CO2 efflux is derived from heterotrophic respiration of low-molecular-weight rhizodeposits (van Hees et al., 2005). Therefore, calculated on an area basis and assuming a 20 % loss owing to respiration, the C input from M. × g exudates could be in the region of 2–10 Mg C ha−1 year−1 (for root biomass of 5–21 Mg ha−1 and based on a 210-day season), which should be taken as a peak estimate. In reality, owing to differences in field environmental conditions, this figure is likely to be lower. Based on the lowest (0.2 g C g−1 root Md year−1) and highest (2.15 g C g−1 root Md year−1) rate recorded from field-grown M. × g at a point in July and August (von Haden et al., 2024), the figure for new C inputs could range from a low of 0.2–10 Mg C ha−1 year−1 to a high of 2–8 Mg C ha−1 year−1 (for root biomass of 5–21 Mg ha−1). However, the fate of this new C is subject to differing processes depending on soil biotic and abiotic conditions and, as a readily accessible form of new C, it might induce priming effects (Kuzyakov et al., 2000; Wen et al., 2022a). It is also worth noting that scaled estimates of C input from root exudation rely heavily on estimates of fine root mass where, in field conditions, it can be difficult to capture fully and to assess the extent of Miscanthus fine root systems.

Although root exudation is an important component of the soil carbon cycle, it is only one aspect of a complex system. In fact, despite the fundamental difference observed in the root C exudation rate for M. sac, this is not necessarily detrimental to the accumulation of SOC. In a long-term field trial, SOC stocks for these same three genotypes (at 10 years old) were 86, 85 and 79 Mg ha−1 for M. sac, M. sin and M. × g, respectively, and were not significantly different from each other (0–30 cm depth; A.J. Holder, IBERS, Aberystwyth University, UK, unpublished research). This could be attributable to species differences in the turnover of roots and rhizomes or inputs derived from above-ground litter and harvest residues. It is also likely that individual genotypic differences and not only broader species differences have an impact (Holder et al., 2019). In other studies, soil organic matter and soil N were also reported to be significantly higher under M. sacchariflorus compared to M. sinensis (5-year-old plants; Chen et al., 2020) and SOC under M. sinensis significantly higher than under M. × g (6-year-old plants; Gregory et al., 2018).

The impact of Miscanthus fine root systems and exudation on SOC accumulation is still unclear. Roots <1 mm in diameter are generally thought to increase SOC by promoting soil macroaggregation (Poirier et al., 2018), and the roots observed in this study were mostly <1.5 mm at this young growth stage, and it is likely that there would be an increase in the smaller root classes as the plants mature. The root trait of SRL can be an indicator of root lifespan, respiration and decomposition rate (Roumet et al., 2016; Freschet et al., 2021; Han and Zhu, 2021), but within this study we found no significant difference in SRL (although this might alter with plant maturity). The composition of root exudates coupled with soil conditions can have positive and/or negative effects on SOC sequestration (Panchal et al., 2022), and it has been suggested that changes in root exudate quality (as opposed to quantity) can affect soil carbon cycling to a greater extent (Lei et al., 2023). Exudate composition was outside the scope of this study but would be worthy of investigation.

Conclusion

The root C exudation rate was significantly lower for M. sac compared with M. sin and M. × g (0.0 versus 0.6 g C g−1 root Md year−1). Coupled with this, M. sac had greater above-ground biomass, a lower increase in root mass and a larger root C concentration. Therefore, the results of this study reveal what could be a fundamental difference in nutrient resource acquisition and allocation between M. sac versus M. sin and M. × g that might also influence soil microbial community composition. It is not certain whether the difference in exudation rate reflects a broader Miscanthus species difference or is related to the individual genotypes sampled. Further exploration of this finding (especially in different controlled-environment and natural field conditions) is desirable to unravel the connection between Miscanthus species physiochemical traits, exudation quantity and quality, and their role in shaping the rhizosphere microbial community and soil carbon cycling. This could unlock possibilities for targeting Miscanthus breeding for enhanced soil carbon sequestration. From this study, we estimate that Miscanthus root C exudation could add new C of ≤2 g C kg−1 soil month−1 (during the peak growing season).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With thanks to: Debbie Allen of Aberystwyth University for performing the C and N analysis; Laurence Jones of Renovation Services for manufacturing the custom rhizotrons; and Sam Robinson of the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Lancaster for advice on the experiment and assistance with the exudate C analysis.

Contributor Information

Amanda J Holder, Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences (IBERS), Aberystwyth University, Plas Gogerddan, Aberystwyth, Wales SY23 3EE, UK.

Rebecca Wilson, Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences (IBERS), Aberystwyth University, Plas Gogerddan, Aberystwyth, Wales SY23 3EE, UK.

Karen Askew, Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences (IBERS), Aberystwyth University, Plas Gogerddan, Aberystwyth, Wales SY23 3EE, UK.

Paul Robson, Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences (IBERS), Aberystwyth University, Plas Gogerddan, Aberystwyth, Wales SY23 3EE, UK.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Annals of Botany online and consist of the following. Figure S1: (A) Custom-made rhizotrons: root boxes constructed from a wooden frame and two sheets of 3-mm-thick Perspex, measuring 60 cm × 46 cm × 10 cm, with a capacity of ∼28 L. (B) An example of a M. sac plant in rhizotron with visible roots (as at 31 July). Figure S2: (A) Extracted root portions are inserted into the incubation tube part-filled with glass beads. (B) Prior to the 24-h incubation period, root portions are sealed in the tube (backfilled with glass beads and C-free nutrient solution), and a collection vial is attached. During incubation, the tubes and exposed rhizotron face were covered with damp cloths, aluminium foil and a black plastic sheet. Figure S3: (A) One example of the full M. sac washed root system at the end of the study period (31 July), with laterally spreading rhizomes. (B) Zoomed-in portion of the first image (as highlighted by the red box). Figure S4: (A) One example of full M. sin washed root system at the end of the study period (31 July), with rhizomes forming into a clump. (B) Zoomed-in portion of the first image (as highlighted by the red box). Figure S5: (A) One example of full M. × g washed root system at the end of the study period (31 July), with less dense rhizome growth in compared with M. sin and less spread compared with M. sac. (B) Zoomed-in portion of the first image (as highlighted by the red box). Figure S6: one example of M. sac roots traced using the SmartRoot plug-in program for ImageJ (for clarity, in this image, line widths are not shown to scale) as at 31 July. Figure S7: one example of M. sin roots traced using the SmartRoot plug-in program for ImageJ (for clarity, in this image, line widths are not shown to scale) as at 31 July. Figure S8: One example of M. × g roots traced using the SmartRoot plug-in program for ImageJ (for clarity, in this image, line widths are not shown to scale) as at 31 July.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) (BB/V011553/1 Perennial Biomas Crops for Greenhouse Gas Removal project and BB/X011062/1 Resilient Crops).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Amanda J. Holder: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft. Rebecca Wilson: Methodology. Karen Askew: Methodology, Investigation. Paul Robson: Conceptualization, Writing—Review & Editing, Funding acquisition.

REFERENCES

- Agostini F, Gregory AS, Richter GM. 2015. Carbon sequestration by perennial energy crops: is the jury still out? Bioenergy Research 8: 1057–1080. doi: 10.1007/s12155-014-9571-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlawat OP, Yadav D, Walia N, Kashyap PL, Sharma P, Tiwari R. 2024. Root exudates and their significance in abiotic stress amelioration in plants: a review. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 43: 1736–1761. doi: 10.1007/s00344-024-11237-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allison GG, Morris C, Clifton-Brown J, Lister SJ, Donnison IS. 2011. Genotypic variation in cell wall composition in a diverse set of 244 accessions of Miscanthus. Biomass & Bioenergy 35: 4740–4747. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2011.10.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amougou N, Betrand I, Machet J-M, Recous S. 2011. Quality and decomposition in soil of rhizome, root and senescent leaf from Miscanthus × giganteus, as affected by harvest date and N fertilization. Plant and Soil 338: 83–97. doi: 10.1007/s11104-010-0443-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E, Arundale R, Maughan M, Oladeinde A, Wycislo A, Voigt T. 2011. Growth and agronomy of Miscanthus x giganteus for biomass production. Biofuels 2: 71–87. doi: 10.4155/bfs.10.80 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnoult S, Brancourt-Hulmel M. 2015. A review on Miscanthus biomass production and composition for bioenergy use: genotypic and environmental variability and implications for breeding. BioEnergy Research 8: 502–526. doi: 10.1007/s12155-014-9524-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Awty-Carroll D, Magenau E, Al Hassan M, et al. 2023. Yield performance of 14 novel inter- and intra-species Miscanthus hybrids across Europe. Global Change Biology: Bioenergy 15: 399–423. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.13026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badri DV, Vivanco JM. 2009. Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant, Cell & Environment 32: 666–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01926.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardgett RD, Mommer L, De Vries FT. 2014. Going underground: root traits as drivers of ecosystem processes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 29: 692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann J, Weigelt A, van Der Plas F, et al. 2020. The fungal collaboration gradient dominates the root economics space in plants. Science Advances 6: eaba3756. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba3756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertola M, Magenau E, Martani E, et al. 2024. Early impacts of marginal land-use transition to Miscanthus on soil quality and soil carbon storage across Europe. Global Change Biology: Bioenergy 16: e13145. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.13145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beuch S, Boelcke B, Belau L. 2000. Effect of the organic residues of Miscanthus × giganteus on the soil organic matter level of arable soils. J Agronomy & Crop Science 183: 111–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-037x.2000.00367.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birouste M, Zamora-Ledezma E, Bossard C, Pérez-Ramos IM, Roumet C. 2014. Measurement of fine root tissue density: a comparison of three methods reveals the potential of root dry matter content. Plant and Soil 374: 299–313. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1874-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black CK, Masters MD, LeBauer DS, Anderson-Teixeira KJ, DeLucia EH. 2017. Root volume distribution of maturing perennial grasses revealed by correcting for minirhizotron surface effects. Plant and Soil 419: 391–404. doi: 10.1007/s11104-017-3333-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bossio DA, Cook-Patton SC, Ellis PW, et al. 2020. The role of soil carbon in natural climate solutions. Nature Sustainability 3: 391–398. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-0491-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks ME, Kristensen K, van Benthem KJ, et al. 2017. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. The R Journal 9: 378–400. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2017-066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brosse N, Dufour A, Meng X, Sun Q, Ragauskas A. 2012. Miscanthus: a fast-growing crop for biofuels and chemicals production. Biofuels, Bioproducts & Biorefining: Biofpr 6: 580–598. doi: 10.1002/bbb.1353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calvin K, Cowie A, Berndes G, et al. 2021. Bioenergy for climate change mitigation: scale and sustainability. Global Change Biology: Bioenergy 13: 1346–1371. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12863 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chae WB, Hong SJ, Gifford JM, Rayburn AL, Sacks EJ, Juvik JA. 2014. Plant morphology, genome size, and SSR markers differentiate five distinct taxonomic groups among accessions in the genus Miscanthus. Global Change Biology: Bioenergy 6: 646–660. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaparro JM, Badri DV, Bakker MG, Sugiyama A, Manter DK, Vivanco JM. 2013. Root exudation of phytochemicals in Arabidopsis follows specific patterns that are developmentally programmed and correlate with soil microbial functions. PLoS One 8: e55731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Tian W, Shao Y, et al. 2020. Miscanthus cultivation shapes rhizosphere microbial community structure and function as assessed by illumina MiSeq sequencing combined with PICRUSt and FUNGUIld analyses. Archives of Microbiology 202: 1157–1171. doi: 10.1007/s00203-020-01830-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimento C, Amaducci S. 2015. Characterization of fine root system and potential contribution to soil organic carbon of six perennial bioenergy crops. Biomass & Bioenergy 83: 116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2015.09.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LV, Stewart JR, Nishiwaki A, et al. 2015. Genetic structure of Miscanthus sinensis and Miscanthus sacchariflorus in Japan indicates a gradient of bidirectional but asymmetric introgression. Journal of Experimental Botany 66: 4213–4225. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton-Brown J, Hastings A, von Cossel M, et al. 2023. Perennial biomass cropping and use: shaping the policy ecosystem in European countries. Global Change Biology: Bioenergy 15: 538–558. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.13038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Deyn GB, Cornelissen JH, Bardgett RD. 2008. Plant functional traits and soil carbon sequestration in contrasting biomes. Ecology letters 11: 516–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01164.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaff MA, Jastrow JD, Gillette S, Johns A, Wullschleger SD. 2014. Differential priming of soil carbon driven by soil depth and root impacts on carbon availability. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 69: 147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.10.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra FA, Zhu B, Cheng W. 2021. Root effects on soil organic carbon: a double-edged sword. The New Phytologist 230: 60–65. doi: 10.1111/nph.17082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erktan A, Roumet C, Munoz F. 2023. Dissecting fine root diameter distribution at the community level captures root morphological diversity. Oikos 2023: e08907. doi: 10.1111/oik.08907 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrarini A, Martani E, Mondini C, Fornasier F, Amaducci S. 2022. Short-term mineralization of belowground biomass of perennial biomass crops after reversion to arable land. Agronomy 12: 485. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12020485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finzi AC, Abramoff RZ, Spiller KS, et al. 2015. Rhizosphere processes are quantitatively important components of terrestrial carbon and nutrient cycles. Global change biology 21: 2082–2094. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonteyne S, Muylle H, Lootens P, et al. 2018. Physiological basis of chilling tolerance and early-season growth in miscanthus. Annals of Botany 121: 281–295. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcx159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J, Weisberg S. 2019. An R companion to applied regression, Third edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Freschet GT, Pagès L, Iversen CM, et al. 2021. A starting guide to root ecology: strengthening ecological concepts and standardising root classification, sampling, processing and trait measurements. The New Phytologist 232: 973–1122. doi: 10.1111/nph.17572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Wang H, Yang F, et al. 2024. Relationships between root exudation and root morphological and architectural traits vary with growing season. Tree Physiology 44:tpad118. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpad118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greef JM, Deuter M. 1993. Syntaxonomy of Miscanthus × giganteus GREEF et DEU. Angewandte Botanik 67: 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AS, Dungait JAJ, Shield IF, et al. 2018. Species and genotype effects of bioenergy crops on root production, carbon and nitrogen in temperate agricultural soil. BioEnergy Research 11: 382–397. doi: 10.1007/s12155-018-9903-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guyonnet JP, Guillemet M, Dubost A, et al. 2018. Plant nutrient resource use strategies shape active rhizosphere microbiota through root exudation. Frontiers in Plant Science 9: 1662. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Zhu B. 2021. Linking root respiration to chemistry and morphology across species. Global Change Biology 27: 190–201. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen EM, Christensen BT, Jensen LS, Kristensen K. 2004. Carbon sequestration in soil beneath long-term Miscanthus plantations as determined by 13C abundance. Biomass & Bioenergy 26: 97–105. doi: 10.1016/S0961-9534(03)00102-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holder AJ, Clifton-Brown J, Rowe R, et al. 2019. Measured and modelled effect of land-use change from temperate grassland to Miscanthus on soil carbon stocks after 12 years. Global Change Biology: Bioenergy 11: 1173–1186. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder AJ, Robson P, McCalmont JP. 2025. Effect of tillage method on early root growth of Miscanthus. Annal of Applied Biology. doi: 10.1111/aab.70006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. 2008. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biometrical Journal 50: 346–363. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hromádko L, Vranová V, Techer D, et al. 2010. Composition of root exudates of Miscanthus × giganteus Greef et Deu. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis 58: 71–76. doi: 10.11118/actaun201058010071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X-F, Chaparro JM, Reardon KF, Zhang R, Shen Q, Vivanco JM. 2014. Rhizosphere interactions: root exudates, microbes, and microbial communities. Botany 92: 267–275. doi: 10.1139/cjb-2013-0225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iordan C, Giroux B, Næss JS, Hu X, Cavalett O, Cherubini F. 2023. Energy potentials, negative emissions, and spatially explicit environmental impacts of perennial grasses on abandoned cropland in Europe. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 98: 106942. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2022.106942 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jing H, Wang H, Wang G, Liu G, Cheng Y. 2023. The mechanism effects of root exudate on microbial community of rhizosphere soil of tree, shrub, and grass in forest ecosystem under N deposition. ISME communications 3: 120. doi: 10.1038/s43705-023-00322-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL, Nguyen C, Finlay RD. 2009. Carbon flow in the rhizosphere: carbon trading at the soil–root interface. Plant and Soil 321: 5–33. doi: 10.1007/s11104-009-9925-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juice SM, Walter CA, Allen KE, et al. 2022. A new bioenergy model that simulates the impacts of plant-microbial interactions, soil carbon protection, and mechanistic tillage on soil carbon cycling. Global Change Biology: Bioenergy 14: 346–363. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12914 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle P, Beuch S, Boelcke B, Leinweber P, Schulten H-R. 2001. Cropping of Miscanthus in central Europe: biomass production and influence on nutrients and soil organic matter. European Journal of Agronomy: The Journal of the European Society for Agronomy 15: 171–184. doi: 10.1016/S1161-0301(01)00102-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaňova H, Carre J, Vranova V, Rejšek K. 2010. Organic compounds in root exudates of Miscanthus × giganteus Greef Et Deu and limitation of microorganisms in its rhizosphere by nutrients. Acta Univ Agric Et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis 58: 203–210. doi: 10.11118/actaun201058050203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Pandey S, Pandey A. 2006. Plant roots and carbon sequestration. Current Science 91: 885–890. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24094284 (20 June 2025, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- Kuzyakov Y, Friedel JK, Stahr K. 2000. Review of mechanisms and quantification of priming effects. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 32: 1485–1498. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00084-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lei X, Shen Y, Zhao J, et al. 2023. Root exudates mediate the processes of soil organic carbon input and efflux. Plants 12: 630. doi: 10.3390/plants12030630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski I, Clifton-Brown JC, Scurlock JMO, Huisman W. 2000. Miscanthus: European experience with a novel energy crop. Biomass & Bioenergy 19: 209–227. doi: 10.1016/S0961-9534(00)00032-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linde-Laursen IB. 1993. Cytogenetic analysis of Miscanthus ‘Giganteus’, an interspecific hybrid. Hereditas (Landskrona) 119: 297–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1993.00297.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wang G, Yu K, Li P, Xiao L, Liu G. 2018. A new method to optimize root order classification based on the diameter interval of fine root. Scientific reports 8: 2960. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21248-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobet G, Pages L, Draye X. 2011. A novel image-analysis toolbox enabling quantitative analysis of root system architecture. Plant Physiology 157: 29–39. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.179895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martani E, Ferrarini A, Serra P, Pilla M, Marcone A, Amaducci S. 2021. Belowground biomass C outweighs soil organic C of perennial energy crops: insights from a long-term multispecies trial. Global Change Biology: Bioenergy 13: 459–472. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.1278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCalmont JP, McNamara NP, Donnison IS, Farrar K, Clifton-Brown JC. 2015. An inter-year comparison of CO2 flux and carbon budget at a commercial-scale land-use transition from semi-improved grassland to Miscanthus × giganteus. Global Change Biology: Bioenergy 9: 229–245. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moll L, Wever C, Völkering G, Pude R. 2020. Increase of Miscanthus cultivation with new roles in materials production—a review. Agronomy 10: 308. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10020308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mönchgesang S, Strehmel N, Schmidt S, et al. 2016. Natural variation of root exudates in Arabidopsis thaliana-linking metabolomic and genomic data. Scientific Reports 6: 29033. doi: 10.1038/srep29033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti A, Zatta A. 2009. Root distribution and soil moisture retrieval in perennial and annual energy crops in northern Italy. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 132: 252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2009.04.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neukirchen D, Himken M, Lammel J, Czypionka-Krause U, Olfs H-W. 1999. Spatial and temporal distribution of the root system and root nutrient content of an established Miscanthus crop. European Journal of Agronomy: The Journal of the European Society for Agronomy 11: 301–309. doi: 10.1016/S1161-0301(99)00031-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panchal P, Preece C, Peñuelas J, Giri J. 2022. Soil carbon sequestration by root exudates. Trends in Plant Science 27: 749–757. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2022.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantigoso HA, Newberger D, Vivanco JM. 2022. The rhizosphere microbiome: plant–microbial interactions for resource acquisition. Journal of Applied Microbiology 133: 2864–2876. doi: 10.1111/jam.15686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RP, Erlitz Y, Bier R, Bernhardt ES. 2008. New approach for capturing soluble root exudates in forest soils. Functional Ecology 22: 990–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01495.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poeplau C, Germer K, Schwarz K-U. 2019. Seasonal dynamics and depth distribution of belowground biomass carbon and nitrogen of extensive grassland and a Miscanthus plantation. Plant and Soil 440: 119–133. doi: 10.1007/s11104-019-04074-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier V, Roumet C, Munson AD. 2018. The root of the matter: linking root traits and soil organic matter stabilization processes. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 120: 246–259. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.02.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband WS. 2022. ImageJ. Bethesda, MD, USA: U.S. National Institutes of Health. https://imagej.net/ij/. [Google Scholar]

- Rathore N, Hanzelková V, Dostálek T, et al. 2023. Species phylogeny, ecology, and root traits as predictors of root exudate composition. The New Phytologist 239: 1212–1224. doi: 10.1111/nph.19060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . 2023. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Richter GM, Agostini F, Redmile-Gordon M, White R, Goulding KW. 2015. Sequestration of C in soils under Miscanthus can be marginal and is affected by genotype-specific root distribution. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 200: 169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2014.11.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robson PRH, Hastings A, Clifton-Brown JC, McCalmont JP. 2019. Chapter 7 Sustainable use of Miscanthus for biofuel. In: Saffron C. ed. Achieving carbon-negative bioenergy systems from plant materials. Cambridge, UK: Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Robson P, Jensen E, Hawkins S, et al. 2013. Accelerating the domestication of a bioenergy crop: identifying and modelling morphological targets for sustainable yield increase in Miscanthus. Journal of Experimental Botany 64: 4143–4155. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson P, Mos M, Clifton-Brown J, Donnison I. 2012. Phenotypic variation in senescence in Miscanthus: towards optimising biomass quality and quantity. Bioenergy Research 5: 95–105. doi: 10.1007/s12155-011-9118-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roumet C, Birouste M, Picon-Cochard C, et al. 2016. Root structure–function relationships in 74 species: evidence of a root economics spectrum related to carbon economy. The New Phytologist 210: 815–826. doi: 10.1111/nph.13828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd A, Littleton E, Clifton-Brown J, Martin M, Hastings A. 2020. Projections of global and UK bioenergy potential from Miscanthus × giganteus—feedstock yield, carbon cycling and electricity generation in the 21st century. Global Change Biology: Bioenergy 12: 287–305. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12671 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JR, Toma YO, Fernández FG, Nishiwaki AYA, Yamada T, Bollero G. 2009. The ecology and agronomy of Miscanthus sinensis, a species important to bioenergy crop development, in its native range in Japan: a review. Global Change Biology: Bioenergy 1: 126–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1757-1707.2009.01010.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Ataka M, Kominami Y, Yoshimura K. 2017. Relationship between fine-root exudation and respiration of two Quercus species in a Japanese temperate forest. Tree Physiology 37: 1011–1020. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpx026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Jiang S, Jiang C, Wu C, Gao M, Wang Q. 2021. A review of root exudates and rhizosphere microbiome for crop production. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28: 54497–54510. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15838-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hees PAW, Jones DL, Finlay R, Godbold DL, Lundstomd US. 2005. The carbon we do not see—the impact of low molecular weight compounds on carbon dynamics and respiration in forest soils: a review. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 37: 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.06.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vives-Peris V, de Ollas C, Gómez-Cadenas A, Pérez-Clemente RM. 2020. Root exudates: from plant to rhizosphere and beyond. Plant Cell Reports 39: 3–17. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02447-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Haden AC, Eddy WC, Burnham MB, Brzostek ER, Yang WH, DeLucia EH. 2024. Root exudation links root traits to soil functioning in agroecosystems. Plant and Soil. 500: 403–416. doi: 10.1007/s11104-024-06491-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z, White PJ, Shen J, Lambers H. 2022b. Linking root exudation to belowground economic traits for resource acquisition. The New Phytologist 233: 1620–1635. doi: 10.1111/nph.17854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen T, Yu GH, Hong WD, et al. 2022a. Root exudate chemistry affects soil carbon mobilization via microbial community reassembly. Fundamental Research 2: 697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.fmre.2021.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese L, Wollenberg E, Alcántara-Shivapatham V, et al. 2021. Countries’ commitments to soil organic carbon in nationally determined contributions. Climate Policy 21: 1005–1019. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2021.1969883 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A, Langridge H, Straathof AL, et al. 2022. Root functional traits explain root exudation rate and composition across a range of grassland species. The Journal of Ecology 110: 21–33. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.13630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler B, Mangold A, von Cossel M, et al. 2020. Implementing Miscanthus into farming systems: a review of agronomic practices, capital and labour demand. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 132: 110053. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2020.110053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zatta A, Clifton-Brown J, Robson P, Hastings A, Monti A. 2014. Land-use change from C3 grassland to C4 Miscanthus: effects on soil carbon content and estimated mitigation benefit after six years. Global Change Biology: Bioenergy 6: 360–370. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.