Abstract

Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) induces immune-mediated demyelination after intracerebral inoculation of the virus into susceptible mouse strains. We isolated from a TMEV BeAn 8386 viral stock, a low-pathogenic variant which requires greater than a 10,000-fold increase in viral inoculation for the manifestation of detectable clinical signs. Intracerebral inoculation of this variant virus induced a strong, long-lasting, protective immunity from the demyelinating disease caused by pathogenic TMEV. The levels of antibodies to the whole virus as well as to the major linear epitopes were similar in mice infected with either the variant or wild-type virus. However, persistence of the variant virus in the central nervous system (CNS) of mice was significantly lower than that of the pathogenic virus. In addition, the T-cell response to the predominant VP1 (VP1233–250) epitope in mice infected with the variant virus was significantly weaker than that in mice infected with the parent virus, while similar T-cell responses were induced against another predominant epitope (VP274–86). Further analyses indicated that a change of lysine to arginine at position 244 of VP1, which is the only amino acid difference in the P1 region, is responsible for such differential T-cell recognition. Thus, the difference in the T-cell reactivity to this VP1 region as well as the low level of viral persistence in the CNS may account for the low pathogenicity of this spontaneous variant virus.

Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV), which is a positive single-stranded picornavirus, is a common enteric virus in mice (15, 46). Two major subgroups of TMEV have been identified based on varying biological characteristics such as neurovirulence and antigenicity (15, 24, 47). The first subgroup of TMEV includes the GDVII and FA strains, which cause rapid fatal encephalitis. The second subgroup, known as Theiler’s original viruses, including the BeAn8386 and DA strains, can cause a chronic biphasic neurological disease upon intracerebral inoculation into susceptible mice (12, 15, 23–25). The early acute phase displays flaccid limb paralysis and degeneration of neurons, while the late phase is characterized by chronic, inflammatory demyelination (25, 27). In particular, the BeAn strain is known to induce a clinically undetectable level of the early-phase disease although it manifests a clinically severe late-phase white matter disease characterized by a spastic waddling gait, extensor spasms, and incontinence (24, 27). Various immunological and genetic factors associated with this disease parallel those of human multiple sclerosis (2, 15, 29, 37), and thus this system is considered to be a relevant, infectious model for multiple sclerosis (11).

A number of immunological and viral parameters have been considered in investigations of the potential mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of demyelination followed by TMEV infection. Immunity to other viruses generally provides the protection of the host from further viral spread and eventual eradication of viral infection. However, the persistent nature of TMEV infection leads to the development of a chronic, immune-mediated inflammation in the central nervous system (CNS) at the site of viral persistence (13). Recent immunological studies with susceptible SJL mice indicate that cell-mediated immunity, in particular a Th1 response, specific for viral capsid proteins is involved in the pathogenesis of demyelination (7, 17, 20, 51). In contrast, the role of antibody responses to the virus in the pathogenesis is not yet clear, although antibodies to a certain viral epitope appear to be associated with disease progression (18, 49). The major population of T cells specific for TMEV during the course of disease or after immunization with UV-inactivated virus essentially recognize three predominant viral epitopes (VP1233–250, VP274–86, and VP324–37), one each on the external capsid proteins (16, 50, 51). The T-cell populations specific for VP1 and VP2 epitopes are primarily the Th1 type, and this type of T cell is most likely involved in the development of immune-mediated demyelination, as such T cells are mainly found in the cellular infiltrate of demyelinating lesions (51).

Several recent studies strongly suggest that the VP1 capsid protein, in particular, plays an important role in the pathogenesis of demyelination induced by TMEV. Infiltrating T cells specific for VP1 have been identified in the demyelinating CNS following viral infection (51). In addition, many attenuated or nonpathogenic TMEV mutants selected for resistance to antiviral antibodies exhibit amino acid substitutions within the VP1 capsid protein (41, 53). Furthermore, one of the major determinants for viral persistence as well as demyelination has been mapped to VP1, using recombinant viruses chimeric between two different types of TMEV (45). Although these viruses have provided valuable information regarding the potential pathogenic mechanisms of TMEV, they may not be naturally occurring variant viruses. Thus, it may be difficult to determine the biological relevance of the variants and to correlate the levels of pathogenesis induced by such viruses with the immune responses to the virus. However, characterization of naturally occurring, low-pathogenic variants may provide important insights into the relationship between viral pathogenesis and immunological parameters.

We have recently isolated a spontaneously occurring TMEV variant (M2) which exhibits low pathogenicity in susceptible SJL/J mice. In this study, we have characterized the variant virus and evaluated the differences between the immune responses to the wild-type and variant viruses, following either viral infection or immunization. We report here that the low-pathogenic variant virus, containing a single amino acid substitution within the predominant T-cell epitope of VP1 capsid protein, is deficient in the development of pathogenic T-cell immunity, while no significant difference is seen in the antibody response. Moreover, this variant virus is able to induce a very effective, long-lasting, protective immunity toward a subsequent infection with the pathogenic, parental virus stock. These results strongly suggest an important possibility for vaccine development against virus-induced, immune-mediated inflammatory disease by introducing targeted mutations within the predominant pathogenic T-cell epitopes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Inbred mouse strains (SJL/J) were purchased from either Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine, or the National Cancer Institute.

Viruses.

A standard plaque assay of the BeAn 8386 strain of TMEV was performed on BHK-21 cell monolayers (8, 36). Plaques in the monolayers were visualized by staining with 0.02% neutral red in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The viruses isolated from individual plaques were tested for pathogenesis of demyelination. The parent BeAn 8386 (173R) stock and pathogenic (S2) and nonpathogenic (M2) viruses derived form the parent stock were propagated in BHK-21 cells in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 7.5% donor calf serum and purified by isopycnic centrifugation on Cs2SO4 gradients as previously described (28).

Synthetic peptides.

The synthetic peptides representing the amino acid residues of TMEV were prepared by using the RaMPS system (DuPont Co., Wilmington, Del.) with 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl reagents. A major single peptide (>95%) was present in each of the peptide preparations, as determined by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography analyses.

Infection of mice with TMEV.

For intracerebral inoculation of virus, various concentrations of virus in 30 μl of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium were administered in the right cerebral hemisphere of mice anesthetized with methoxyflurane. Such an inoculum of the wild-type virus consistently induced chronic gait abnormality and neurological signs in susceptible mouse strains (9). TMEV-infected mice were examined for clinical signs of demyelination such as waddling gait, extensor spasms, paralysis, loss of the righting reflex, incontinence, and/or hunched posture.

Histology.

Mice were perfused under anesthesia via the intraventricular route with 4% freshly prepared paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4). Spinal cords were removed by dissection, cut into 1-mm cross sections, postfixed in 1% OsO4, and embedded in Epon as previously described (12, 36). Tissue sections from spinal cords were cut to 1-μm thickness, stained with toluidine blue, and examined under light microscopy.

Immunization of mice with TMEV.

SJL/J mice were injected subcutaneously in the base of the tail with 100 μl (50 μg) of a 1:1 emulsion of UV-inactivated S2 (UV-S2) or UV-M2 in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA). Nine days later, lymph node cells were pooled from two mice, and the level of T-cell proliferation was subsequently assessed in vitro.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR for viral message levels.

Total cellular RNA of spinal cords from PBS-perfused mice was isolated by the guanidine isothiocyanate method (6). mRNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA by using oligo(dT)15–18 and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase. The relative concentrations of cDNA were equalized among the groups based on the level of β-actin amplification (35 cycles) by PCR. The level of virus-specific message was assessed by using the 5′-end sense sequence of the leader and the 3′-end antisense sequence of VP4 (33). The relative levels of the viral message at a given time point were expressed as ratios to the β-actin amplification after densitometric analyses of the PCR products, using a Bio-Rad computer program.

Assessment of PFU.

Spinal cords were removed by forced flushing of the spinal canal with sterile Hanks balanced salt solution. The tissue was homogenized individually as a 10% (wt/vol) solution in PBS with a tissue homogenizer (Vir-Tishear) and clarified by low-speed centrifugation (600 × g). A standard plaque assay was performed on BHK-21 cell monolayers (8, 36). Plaques in the monolayers were visualized by staining with 0.02% neutral red in PBS. The detection range of the plaques over background is ≤100 PFU/g of tissue.

ELISA for detection of TMEV antigens.

Antibodies specific for viral epitopes were measured by using an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously (18). Briefly, either 0.3 μg of total virus or individual peptide-bovine serum albumin conjugates were used to coat microtiter plates. A bovine serum albumin solution (0.3 μg) was also used to coat the plates to serve as a negative control, and the values were used to subtract the background reaction. Unless otherwise stated, duplicates of twofold serial dilutions of pooled sera starting from a 1:100 dilution were applied followed by goat anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase. After the plates were washed, substrate (p-nitrophenyl phosphate) for the enzyme was added and the enzyme reaction was colorimetrically measured in an ELISA reader at 410 nm. The average value was shown in the results.

TMEV-specific T-cell lines.

Antigen-specific T-cell clones were established from the spinal cords of TMEV-infected SJL/J mice. Briefly, mice were perfused with 30 ml of PBS, and then single-cell suspensions of spinal cords were prepared as described previously (51). After three washes with Hanks balanced salt solution, cells were collected from the interface of a 100%/50% discontinuous Histopaque gradient (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and cultured on 96-well round-bottom microtiter plates with either UV-inactivated virus or peptides in the presence of irradiated syngeneic splenocytes and 10 U of recombinant interleukin-2 (IL-2) (Genzyme Diagnostics, Cambridge, Mass.) per ml. T-cell lines were maintained by biweekly stimulation with UV-inactivated virus or peptides, in the presence of 5 U of recombinant IL-2 per ml.

T-cell proliferation assay.

Spleen or lymph node cells (5 × 105) were cultured in 96-well flat-bottom microculture plates in RPMI 1640 containing 0.5% syngeneic mouse serum and 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol. Triplicate cultures were stimulated with UV-TMEV (25 μg/ml) for 72 h. Cultures were then pulsed with 1.0 μCi of [3H]TdR and harvested 18 h later. Measurements of [3H]TdR uptake by the cells were determined in a scintillation counter and expressed as counts per minute. T-cell lines were similarly tested for antigen specificity (51). Briefly, 2 × 104 Histopaque-purified T cells were cultured for 72 h with the appropriate antigen in the presence of 5 × 105 irradiated, syngeneic splenocytes without exogenous IL-2. Cultures were pulsed with [3H]TdR, harvested, and analyzed for [3H]TdR uptake as described above.

DNA sequencing of M2 variant.

The P1 region of the M2 variant virus was amplified by RT-PCR using several sets of 5′-end sense and 3′-end antisense primers as described previously (51). The amplified PCR product was subcloned into pGEX5X-1 or pGEM-T vector and then sequenced by the dideoxynucleotide termination method, using a Sequenase kit (Amersham Life Science, Inc., Arlington Heights, Ill.) and virus-specific primers. To ensure the accuracy of the sequencing, at least three to four clones of the wild-type control and the M2 variant viruses were examined.

Statistical analysis.

The significance (two-tailed P value) of the differences between experimental animal groups with various treatments and the control group was analyzed based on the unpaired, nonparametric test by using the InStat Program (GraphPAD Software, San Diego, Calif.).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The entire nucleotide sequence of the M2 virus P1 region is deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AF030574).

RESULTS

Isolation of a low-pathogenic TMEV variant.

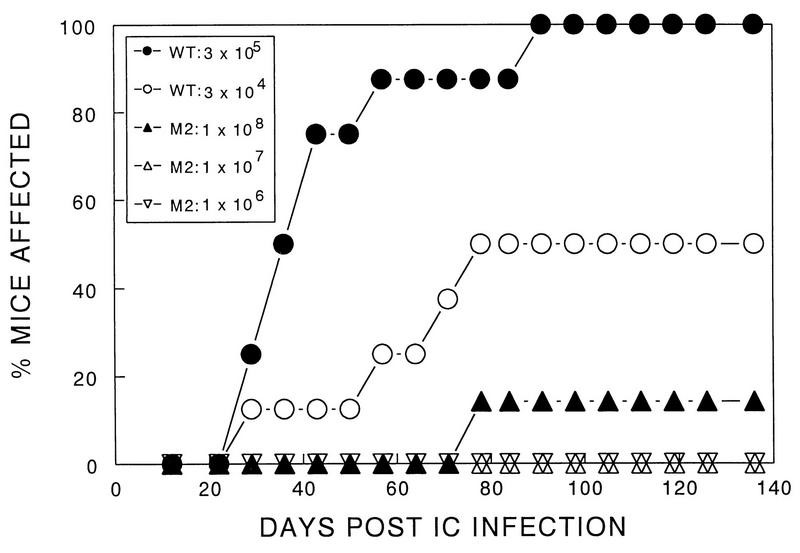

Among several virus plaques of a TMEV BeAn 8386 stock, we identified one clone (M2) which failed to induce clinical symptoms at a dose (106 PFU) which consistently induces demyelinating disease by the parental as well as other clones isolated simultaneously. As much as 108 PFU of M2 virus was required to induce a marginal level (one of eight mice with mild symptoms) of clinical signs in susceptible SJL/J mice (Fig. 1). In contrast, 50% of SJL/J mice developed clinical signs after inoculation of as little as 3 × 104 PFU, and 100% did so after inoculation of 3 × 105 PFU of parent virus. These results indicate that a TMEV variant which is as much as 10,000-fold less pathogenic than the wild-type virus can be readily isolated from a virus stock.

FIG. 1.

Determination of the level of pathogenicity of TMEV variant M2. SJL mice were infected with different numbers of PFU of the parental (wild-type [wt]) or variant virus. Development of clinical signs associated with TMEV-induced demyelination in susceptible SJL was monitored for 136 days. The parent or M2 variant stock was inoculated intracerebrally (IC) into separate groups (8 to 12 mice per group) of SJL/J mice. The clinical signs were assessed as described in Materials and Methods. The unpaired nonparametric test indicates that the difference between the pathogenicity of 108 PFU of M2 and either 3 × 105 or 3 × 104 PFU of parent stock is very significant (P < 0.0001).

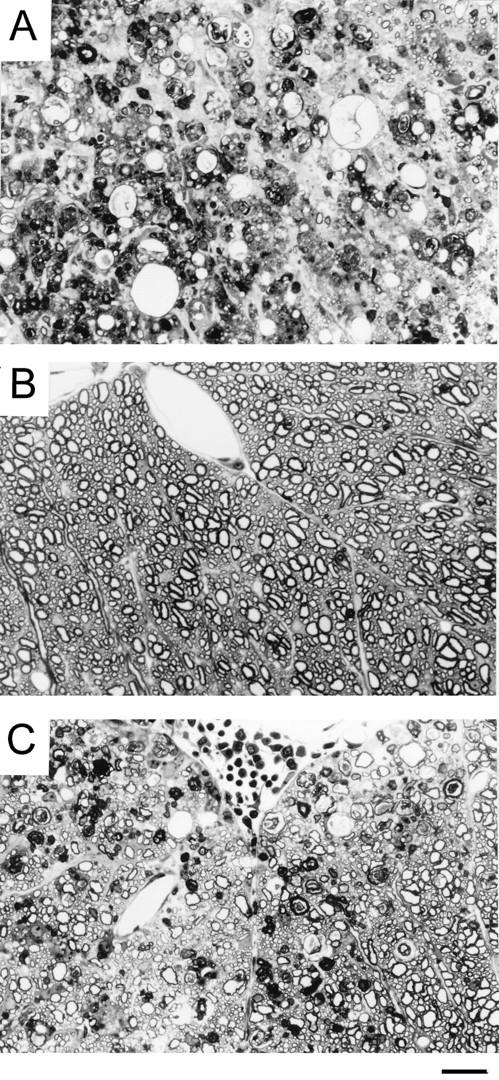

Low level of histopathology in the CNS infected with the variant virus.

To verify the low pathogenicity of the M2 variant by clinical signs, the levels of demyelination and cellular infiltration were histologically examined (Fig. 2). Spinal cords from clinically affected SJL/J mice infected with the pathogenic parent virus (106 PFU) exhibited marked inflammation (Fig. 2A). Leptomeningeal infiltrates by lymphoid cells and extensive areas of demyelination were apparent. Demyelinated axons were scattered in both anterior and lateral columns of the spinal cord, and macrophages laden with myelin debris were a frequent occurrence. However, M2 virus-infected mice without clinical signs displayed no histopathological evidence of demyelination (Fig. 2B), and the mice with clinical symptoms exhibited a mild degree of demyelination (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Histopathologic examination of SJL/J mice infected with either parent or M2 virus. At least 10 cross sections of each spinal cord from three mice per group were examined for histopathology 136 days after viral infection. A representative micrograph for each group is shown. One-micrometer-thick, Epon-embedded sections were stained with toluidine blue. Bar = 50 μm. (A) Spinal cord section from a mouse infected with the pathogenic parent virus showing severe white matter inflammation accompanied by axonal and myelin degeneration. Numerous macrophages are seen in the field. (B) Spinal cord section from a clinically healthy mouse after infection with 108 PFU of M2 variant virus demonstrates normal white matter. No inflammation or demyelination is seen in the field. (C) Spinal cord section from a clinically affected mouse after infection with 108 PFU of M2 variant virus shows mild to moderate white matter involvement by inflammation and demyelination. This field represents the maximum severity observed in animals infected with the variant virus.

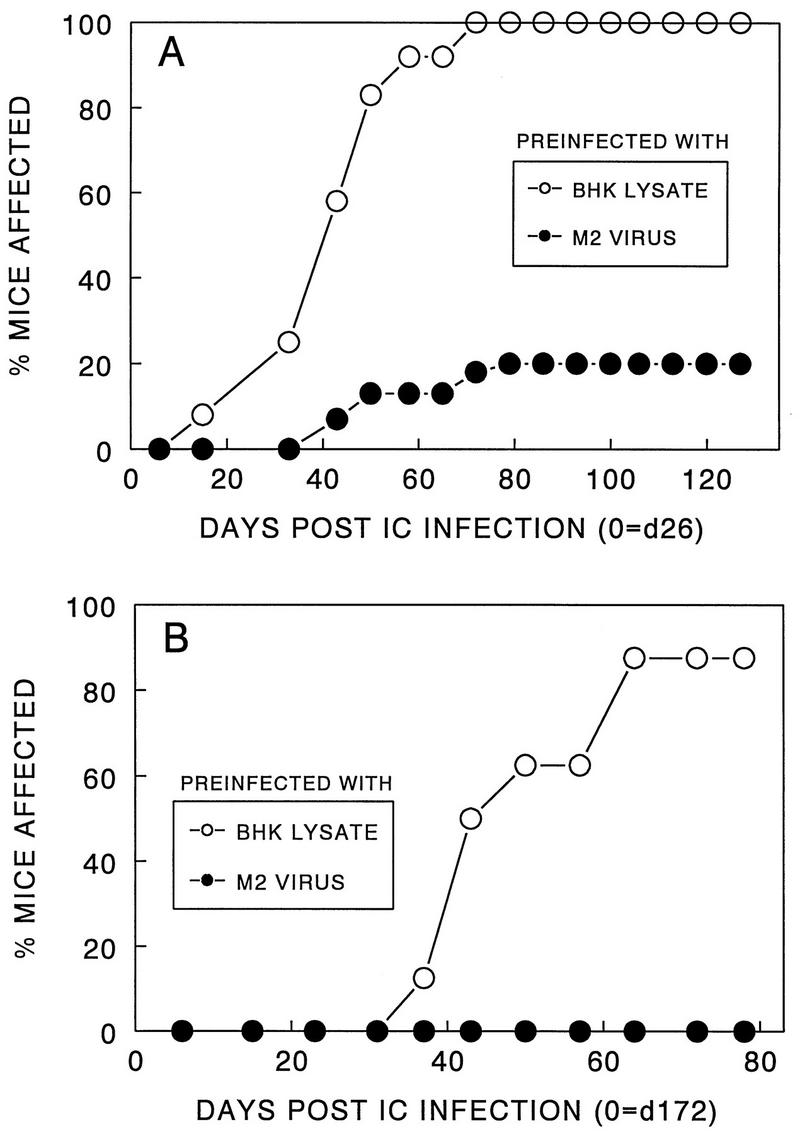

Induction of long-lasting, protective immunity with variant virus.

Since intracerebral inoculation of the variant virus did not result in either clinical or histopathological disease in most animals (Fig. 1 and 2), we infected again the disease-free mice with pathogenic virus (106 PFU) 4 weeks after the initial inoculation with low-pathogenic virus (107 PFU). Mice preinoculated with the low-pathogenic virus developed minimal levels of clinical or histopathological signs, whereas all age-matched, BHK lysate-injected control mice showed clinical signs by day 80 after inoculation with the pathogenic virus (Fig. 3A). These results indicate that this low-pathogenic variant virus can induce efficient protective immunity against demyelination after infection with pathogenic virus.

FIG. 3.

Induction of long-lasting protective immunity after inoculation with M2 virus. (A) Fifteen SJL/J mice were inoculated intracerebrally (IC) with M2 variant virus (107 PFU). After 26 days, these mice were infected intracerebrally with pathogenic parent virus (106 PFU), and then the development of clinical signs was observed. As a control group, 12 mice injected intracerebrally with BHK lysates instead of M2 virus were subsequently infected with pathogenic virus. (B) Groups of SJL/J mice (eight mice per group) were initially inoculated with either BHK lysates or M2 virus and then infected with pathogenic parent virus after 172 days. The protection was extremely significant (P < 0.0001) in both experiments.

To assess the duration of the protective immunity induced by low-pathogenic variant, healthy SJL mice originally inoculated with either the M2 virus or control BHK lysates were infected with pathogenic virus 172 days after the initial inoculation. Mice preinfected with M2 virus displayed complete protection from demyelinating disease inducible by the pathogenic virus, whereas nearly all of the control mice initially inoculated with BHK lysates developed disease. These results clearly demonstrate that the protective immunity induced by the variant virus is extremely long lasting (Fig. 3B), similar to that induced by subcutaneous immunization with UV-inactivated pathogenic parental virus (10).

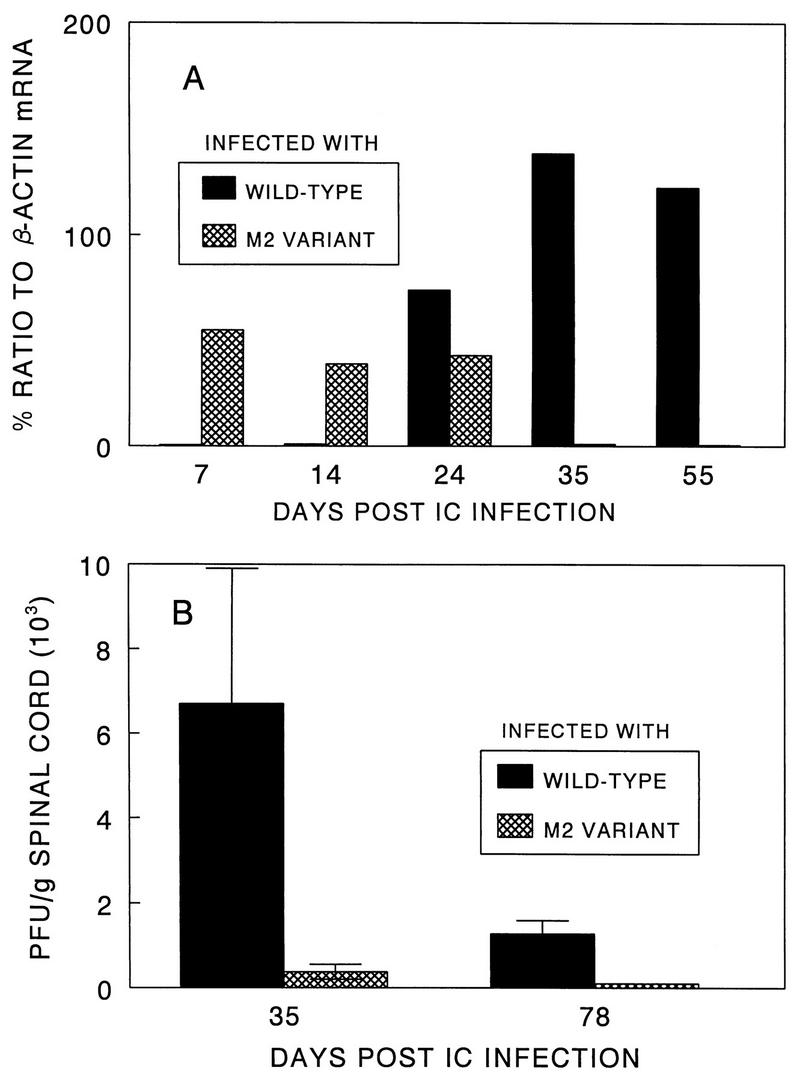

Reduced viral persistence in the CNS following infection with the variant virus.

Viral persistence in the CNS has been implicated as a critical factor for the pathogenesis of TMEV (3, 24, 39). Therefore, it is conceivable that the variant M2 virus is of low pathogenicity due to the deficiency in viral persistence in the CNS. To examine this possibility, we analyzed viral persistence by assessing the levels of viral RNA as well as PFU in the CNS after viral infection. The pathogenic parent virus persisted significantly longer in the spinal cords of SJL/J mice than the nonpathogenic variant virus (Fig. 4). The M2 RNA level increased rapidly in the beginning after viral infection (7 to 24 days) and then decreased drastically. In contrast, the parent viral RNA accumulated significantly only after day 14 and continuously increased to a peak at day 35, followed by a prolonged persistence to later than day 55 postinoculation. Similar patterns were found in experiments analyzing PFU of the viruses recovered from spinal cords of virus-infected mice (Fig. 4B). The level (PFU) of the pathogenic parent virus was significantly higher than that of the M2 variant virus at day 35 postinfection, and only the pathogenic virus was detectable at day 78. Therefore, the reduced level of viral persistence of the M2 variant appears to be an important factor for weakening the pathogenicity of this variant virus.

FIG. 4.

Viral persistence in the CNS following intracerebral (IC) infection of SJL/J mice with pathogenic parent and low-pathogenic variant viruses. (A) Determination of viral message levels in the spinal cords by RT-PCR. Two spinal cords per time point were pooled, and the presence of viral message was assessed by RT-PCR at 7, 14, 24, 35, and 55 days after intracerebral virus inoculation. The sense primer used for amplification represents the 5′ end of the leader coding sequence, and the antisense primer represents the 3′ end of the VP4 coding sequence. (B) Determination of PFU recovered from the spinal cords of virus-infected SJL/J mice. Three separate spinal cords were assessed at each time point of 35 and 78 days after viral inoculation.

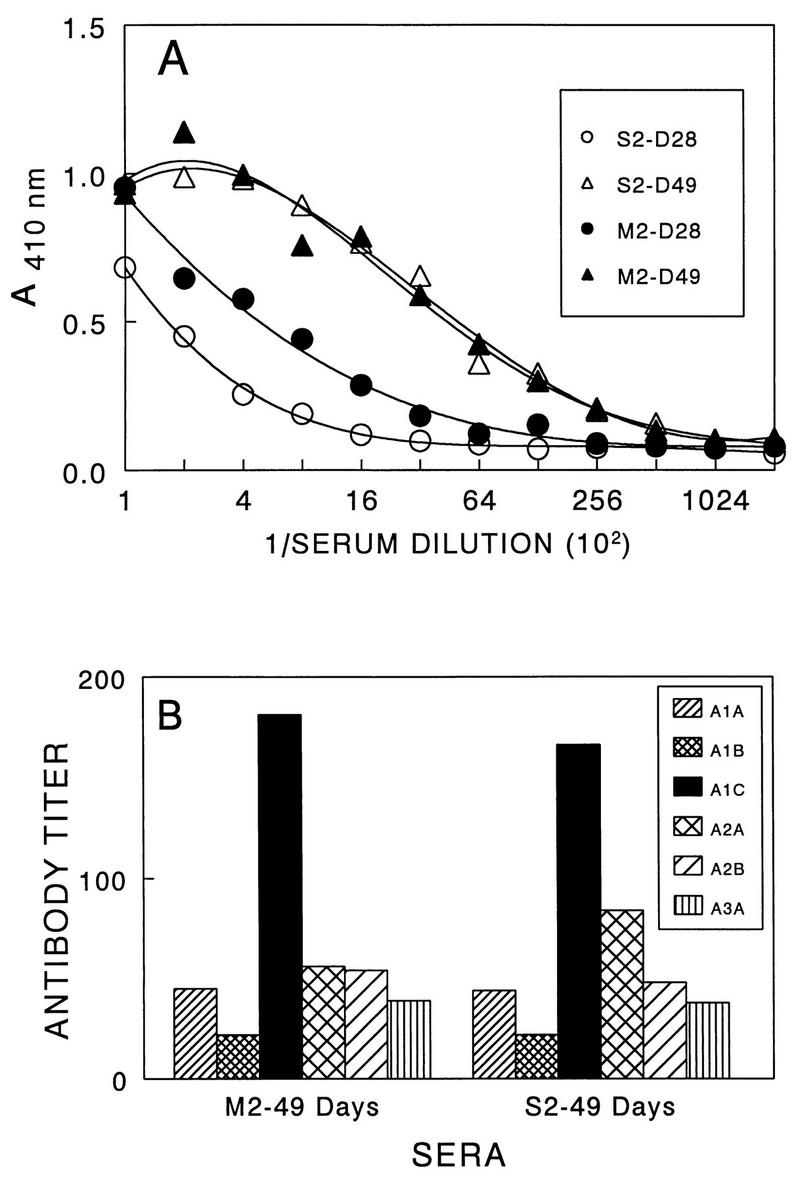

Similar antibody responses in mice infected with pathogenic or variant virus.

To correlate antibody responses with the pathogenicity of the viruses, the levels of anti-TMEV antibodies from mice infected with either the pathogenic or nonpathogenic variant virus were analyzed (Fig. 5). Antibody titers against the parent virus were examined on days 28 and 49 after viral infection. The antibody titers in mice infected with the pathogenic S2 virus at these time points were not significantly different from those infected with the M2 variant virus (Fig. 5A). In addition, patterns of the antibody responses to the major linear epitopes in SJL/J mice infected with either the pathogenic or nonpathogenic virus were similar (Fig. 5B), and the isotype profiles of antibodies specific for TMEV as well as for the individual epitopes were indistinguishable (data not shown). These results suggest that there is no significant difference in the antibody response induced by variant virus and that such immunity may not play a major role in the pathogenesis of viral demyelination.

FIG. 5.

Antibody responses to TMEV in SJL/J mice (five mice per group) infected with either pathogenic or low-pathogenic variant virus. Twofold serial dilutions of pooled sera containing equal volume from individual mice were assessed by ELISA. (A) Reactivity to purified TMEV by antibodies in sera from SJL/J mice infected with either pathogenic (S2 stock) or low-pathogenic (M2) virus at days 28 and 49 postinfection. (B) Reactivity to the major linear antibody epitopes by the same sera at day 49 postinfection.

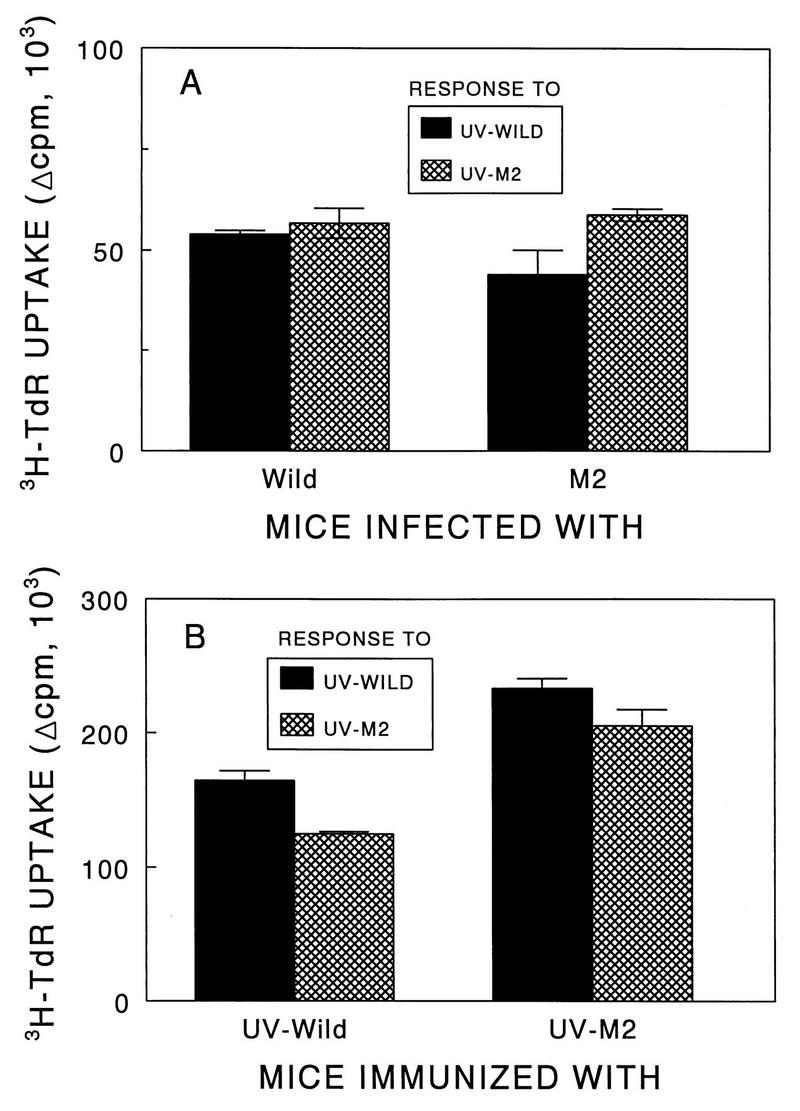

Induction of similar T-cell proliferative responses by parent and variant viruses.

To assess the levels of T-cell response to the parent and variant viruses, T-cell proliferative responses of splenocytes from SJL/J mice infected with the viruses, as well as lymph node cells from mice immunized with UV-inactivated viruses, were tested. The levels of proliferative response of splenic T cells from mice infected with live viruses were similar to each other (Fig. 6A). In addition, T cells induced by the wild-type virus were similarly stimulated by the variant virus and vice versa. Furthermore, the levels of T-cell proliferative response in mice immunized with UV-inactivated viruses were also similar, although the levels in mice immunized with the variant virus appeared to be slightly higher than those in mice immunized with the pathogenic wild-type virus (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Comparison of T-cell proliferation responses of SJL/J mice infected intracerebrally with live pathogenic or variant viruses and of SJL/J mice immunized subcutaneously with UV-inactivated pathogenic or variant viruses. (A) T-cell proliferative responses of spleens from SJL/J mice. SJL/J mice were infected intracerebrally with either parent (106 PFU) or M2 (106 PFU) virus. Three weeks after viral infection, spleens were pooled from two mice and subsequently cultured in triplicate (5 × 105/well) in the presence of 25 μg of either UV-BeAn or UV-M2 per ml. (B) Proliferative response of T cells from BeAn- or M2-immunized mice to UV-inactivated parent and variant viruses. SJL/J mice were immunized at the base of the tail with 50 μg of UV-BeAn or UV-M2 emulsified in CFA. Nine days later, lymph node cells were pooled from two mice and subsequently cultured in triplicate (5 × 105/well) with 25 μg of either UV-BeAn or UV-M2 per ml. All cultures were pulsed with [3H]TdR approximately 18 h before harvesting. A peptide containing the amino acids 5 to 19 of HEL was used as a negative control for both experiments. The background levels were less than 5,000 cpm and subtracted from the experimental values.

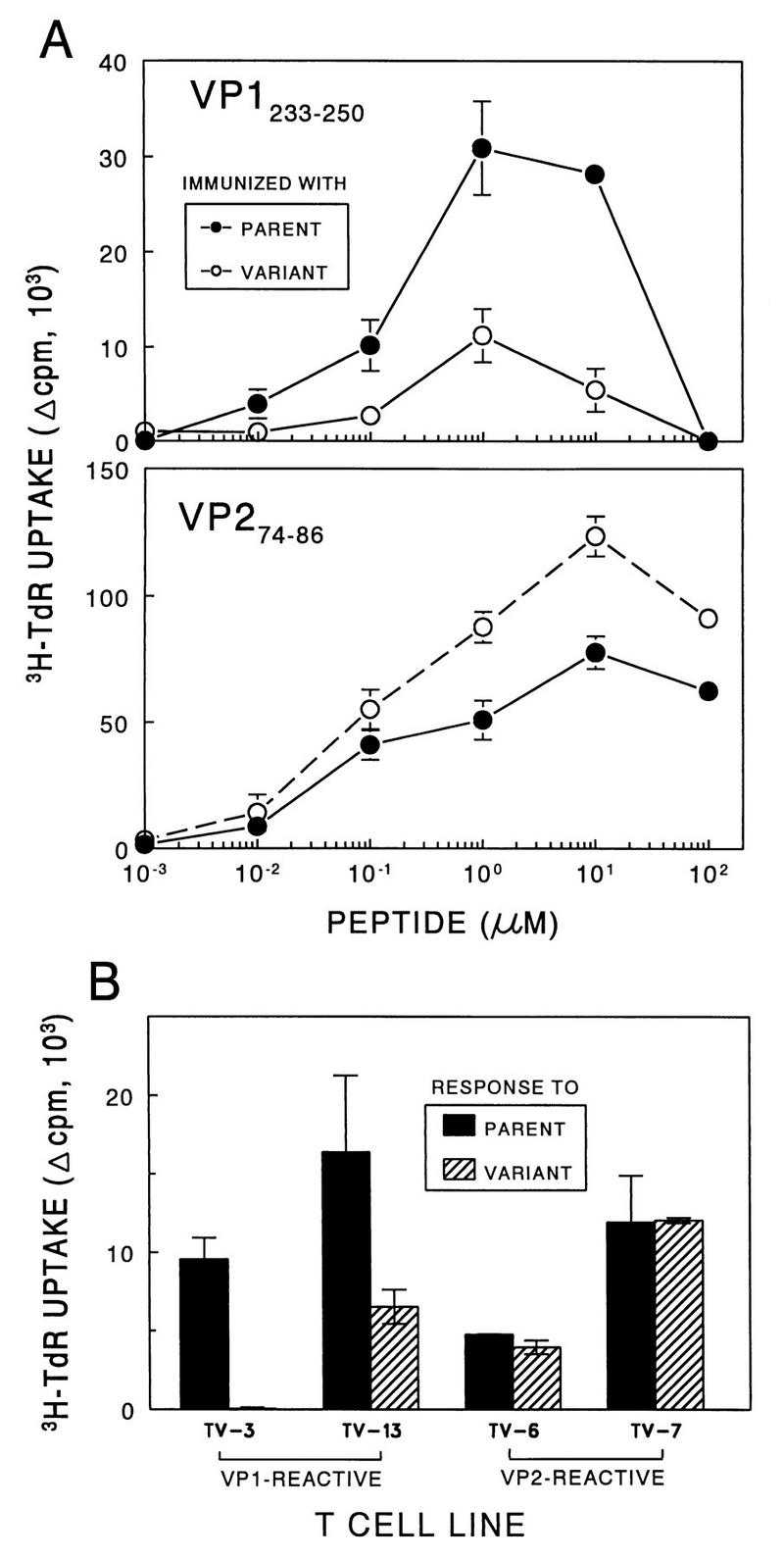

Poor T-cell reactivity to VP1233–250 in response to the M2 variant.

T cells from draining lymph nodes of UV-TMEV-immunized mice were further analyzed for their reactivity to the major T-cell epitopes on VP1 and VP2 of the pathogenic virus (Fig. 7A). To include broader T-cell populations reactive to the VP1 epitope region, VP1233–250 was used instead of the minimal epitope, VP1233–244. The results indicate that the T-cell proliferative response to VP1233–250 is significantly lower in mice immunized with the M2 variant virus than in mice similarly immunized with the pathogenic parent virus. However, only a slight increase in the T-cell proliferative response was detected in these mice against another predominant T-cell epitope, VP274–86 (Fig. 7A). These results suggest that the VP1 epitope on the variant M2 virus may be different from that of the parent virus and/or that this epitope is not readily generated from the M2 virus.

FIG. 7.

Assessment of the T-cell proliferative responses to TMEV and predominant epitopes. (A) T-cell proliferative responses of parent- and M2-immunized mice against the major VP1 and VP2 epitopes. SJL/J mice were immunized at the base of the tail with 50 μg of UV-BeAn or UV-M2 emulsified in CFA. Nine days later, lymph node cells were pooled from two mice and subsequently cultured in triplicate (5 × 105/well) with various molar concentrations of VP1233–250 or VP274–86 for 4 days. A peptide containing the amino acids 5 to 19 of HEL was used as a negative control. Cultures were pulsed with [3H]TdR approximately 18 h before harvesting. Results are expressed as (mean cpm from peptide-stimulated cultures − mean cpm from HEL5–19-stimulated cultures) ± standard error of the mean. (B) Stimulation of CNS-derived T-cell lines specific for VP1233–250 and VP274–86 with the parent or M2 virus. Either VP1- or VP2-specific T-cell lines (2 × 104/well) were stimulated with 12.5 μg of UV-inactivated parent or M2 virus per ml in the presence of irradiated, syngeneic splenocytes (5 × 105/well) for 4 days as described in the text. TV-3 and TV-13 are specific for VP1233–250, and TV-6 and TV-7 are specific for VP274–86.

To determine the possibility that the VP1 epitope of M2 virus is altered, the reactivities of representative VP1233–250- and VP274–86-specific T-cell lines (51) derived from demyelinating lesions of SJL/J mice following infection with the pathogenic virus were tested against UV-M2 virus (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, T-cell lines specific for the wild-type VP1 were much less reactive to the M2 virus than to the pathogenic virus, although the degree of the differences somewhat varied depending on the T-cell lines. However, similarly derived, VP2-reactive T-cell lines showed virtually identical levels of proliferation either to the pathogenic parent virus or to the M2 variant virus. These results strongly suggest that the T cells specific for the wild-type VP1233–250 epitope (but not for the VP2 epitope) do not efficiently recognize M2 virus, and this may reflect the difference in the VP1 epitope itself or a reduced production of the epitope peptide from the variant virus.

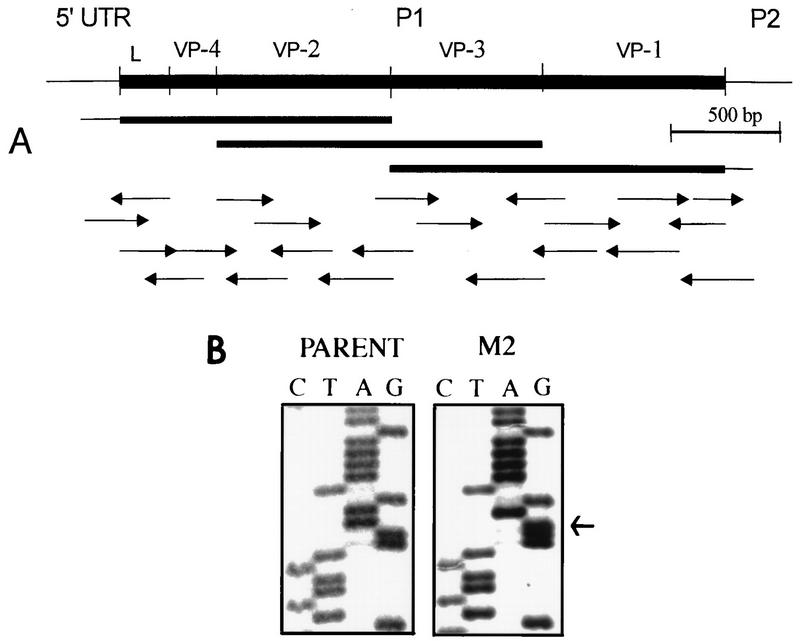

A single amino acid substitution within the VP1233–250 region of M2 variant virus.

To examine the possibility that the poor reactivity of VP1-specific T cells with the M2 variant virus reflects a structural alteration within this T-cell epitope, the P1 region containing the leader and the VP4, VP2, VP3, and VP1 proteins was cloned by RT-PCR, sequenced (Fig. 8A), and then compared with the previously reported sequences (34). Interestingly, a nucleotide switch from A to G at position 3733, resulting in a change of lysine to arginine at residue 244 within VP1233–250, was identified (Fig. 8B). An additional nucleotide change (T→C) was detected at position 1592, but this change did not result in an amino acid alteration. In addition, an insertion of C at position 2815 and a deletion of G at 2822 were found compared to the previously reported sequence (34). These alterations result in Thr-Asp-Thr instead of Met-Thr-Arg. Also, C rather than the reported A was found at position 2880, resulting in an amino acid change from Lys to Glu in VP3. However, these differences appear to represent sequencing errors in the original publication since those sequences in our wild-type virus were identical to that of the variant virus as well as to that of the closely related TMEV DA strain (32). No other mutation was found within the entire P1 region of the M2 variant virus (data not shown). Therefore, the poor reactivity of VP1233–250-specific T cells to the M2 variant virus most likely reflects the change from lysine to arginine. This alteration may influence the pathogenicity of the variant, as the Th1 cells reactive to this epitope in mice infected with the wild-type virus are the major T-cell population in the demyelinating lesion (51).

FIG. 8.

Strategy for sequencing the P1 region of M2 virus and identification of a codon leading to a single amino acid change within the VP1 T-cell epitope region. (A) Schematic presentation of the strategy for sequencing the P1 region of the M2 variant. Arrows indicate the specific primers used in sequencing, and the length represents the size of the sequence analyzed. UTR, untranslated region. (B) M2 virus contains a point mutation (A→G) at nucleotide position 3733 (indicated by the arrow) of VP1 that results in a lysine-to-arginine change at amino acid residue 244 of the VP1 capsid protein. The nucleotide sequences of parent and M2 viruses coding for the VP1244 region are shown.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have isolated a spontaneously arising variant of TMEV and compared the pathogenicity, persistence in the CNS, and immune response in SJL/J mice to those of the parent virus. The pathogenicity and viral persistence of the variant virus were much lower than those of the pathogenic parent virus (Fig. 1, 2, and 4). This is not surprising in light of previous studies demonstrating that the pathogenicity of TMEV may be associated with viral persistence (4, 30, 44). In addition, injection of lipopolysaccharide stimulating various proinflammatory cytokines into genetically resistant C57BL/6 mice after pathogenic virus infection (51), or into susceptible SJL/J mice after infection with a low-pathogenic variant (33), results in a markedly increased viral persistence in the CNS as well as susceptibility to TMEV-induced demyelination. Furthermore, in vitro viral infectivity to macrophages from resistant C57BL/6 mice increased significantly following treatment with lipopolysaccharide (36), suggesting that an increase in inflammation may also promote viral persistence. However, the relationship between viral persistence and pathogenicity is not yet clear. Perhaps these factors are synergistic: viral persistence provides continuous stimulation of immune-mediated inflammation resulting in clinical symptoms, and the increased inflammatory response also enhances viral persistence in the lesion.

The manifestation of demyelination induced by TMEV is apparently immune mediated (14, 26, 38, 40, 48). Susceptible mice display strong humoral as well as cellular immune responses toward viral antigens during TMEV infection (8, 15). In particular, there is a correlation between the Th1 response specific for the viral antigens and the clinical signs of disease (8). Recently, it has been shown that the major splenic T-cell proliferative response of SJL mice infected with TMEV is directed against VP1 and VP2 (16, 42). Our recent studies with CD4+ T-cell clones derived from inflammatory spinal cords suggest that T cells reactive to the VP1 (VP1233–250) and VP2 (VP274–86) epitopes are likely to be involved in the immune-mediated inflammatory demyelination (51). T cells specific for these epitopes produce Th1-type cytokines upon stimulation in vitro with viral epitopes, and this result is consistent with the functional correlative studies (data not shown). Recently, a third major CD4+ T-cell epitope, overlapping the major linear antibody epitope of VP3, was identified on VP3 (VP324–37) (18, 51). The T-cell precursor frequency analysis indicates that these three viral epitopes (one on each VP1, VP2, and VP3) can account for the great majority (>85%) of the T cells reactive to the virus.

The total levels of T-cell proliferative responses to the parent and variant viruses in mice infected with pathogenic parent virus were not significantly different from those in mice infected with low-pathogenic variant virus. Similarly, the antibody responses were not readily distinguishable. However, virus-specific T-cell populations induced by variant virus poorly recognized one of the major T-cell epitopes of the pathogenic parent virus selectively, i.e., VP1233–250 but not VP274–86. Further study indicated that a single amino acid substitution within the VP1 epitope is responsible for the altered reactivity. It has previously been demonstrated that spontaneously occurring variants of other viruses, which escape from cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-mediated lysis, contain similar substitutions within the major cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes (22, 35, 52). In contrast, such an amino acid substitution within a major viral Th epitope has not been well documented. Since a high level of Th1 cells specific for this VP1 epitope is found in the demyelinating lesions in the CNS (51), these results strongly suggest the possibility that the type of T-cell responses to this VP1 epitope is critically important for the pathogenesis of TMEV-IDD. The alteration in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-restricted T-cell epitope may reduce the level of Th1 cells involved in the pathogenesis by modifying the interactions of the epitope peptide with MHC and/or T-cell receptor. Such a substitution within the pathogenic T-cell epitope may lead to immune deviation (31) resulting in the development of a Th2 response rather than a pathogenic Th1 response. Alternatively, the epitope with this substitution may function as an antagonist (22, 43), which could actively inhibit the stimulation of pathogenic Th1 response upon subsequent challenge with wild-type virus. These possibilities are currently being investigated.

However, it is not yet clear whether the altered T-cell response to the VP1 epitope is solely responsible for the drastic reduction in the pathogenic function of the variant virus. Our preliminary sequencing studies indicate that no additional amino acid alterations are present within the P1 region, including the leader as well as the VP4, VP2, VP3, and VP1 proteins, other than the conserved lysine-to-arginine change in the variant virus at position 244 within VP1233–250 (Fig. 8). This conserved change may reflect the importance of maintaining the structural integrity of the virus. In fact, no major differences in the antibody responses, including that against the major neutralizing epitope (VP1262–276), were found in mice infected with either the wild-type or variant virus. Since the major immune response induced after TMEV infection is directed against the proteins encoded by the P1 region, this substitution may play an important role in the immune-mediated pathogenicity of virus. In addition, it has been previously reported that VP1 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of TMEV-induced demyelination. For example, escape mutants of TMEV from neutralizing antibodies directed toward VP1 epitopes, including the VP1101 and VP1262-276 regions, display altered, low pathogenesis (41, 53). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that a single amino acid substitution may also alter the pathogenicity of another closely related picornavirus, encephalomyocarditis virus (1). Thus, it is conceivable that such a single residue substitution is sufficient for significantly altering the pathogenicity of a virus. In addition, we have selected additional low-pathogenic variants exhibiting the identical amino acid substitution at position 244 of VP1, which supports the possibility that this single amino acid change results in low pathogenicity. However, it is also possible that additional alterations in the viral genome (e.g., 5′ and 3′ untranslated and/or P2/P3 regions) influence the pathogenicity of the virus (5, 19). To rule out the possibility that any variation(s) other than the substitution at position 244 in VP1 is responsible for the altered pathogenicity, further analysis of the entire genome of the virus would be necessary. Recombinant viruses containing various regions of the variant M2 virus are currently being generated to address this issue.

Nevertheless, it is interesting that the low-pathogenic variant of TMEV efficiently induced a similar antibody response although its persistence in the CNS was significantly reduced. Furthermore, preinoculation of susceptible mice with the variant resulted in a potent protection from the development of demyelinating disease after infection with the pathogenic virus. However, production of antibodies to TMEV alone may not be sufficient to deliver protection in the host since SJL/J mice infected with pathogenic virus undergoing demyelination also produce high levels of antibodies (8, 18, 21, 49). Therefore, the level or type of MHC class II-restricted T-cell responses to the VP1 epitope may be critical for the development of long-lasting, strong protective immunity. Perhaps strong Th2 and/or protective CTL responses are preferentially induced in response to the variant virus compared to the pathogenic virus. Our preliminary studies suggest that this variant virus is capable of inducing a strong Th2 response rather than Th1 response, in contrast to the pathogenic parent virus (data not shown). Thus, amino acid substitutions within the major T-cell epitopes of pathogenic viruses may provide an attractive means to attenuate viruses delivering strong protective immunity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants RO1 NS 28752 and RO1 NS33008.

We acknowledge Gay Rasmussen and Kay Kerekes for excellent technical help and JoAnn Palma for valuable assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bae Y S, Yoon J W. Determination of diabetogenicity attributable to a single amino acid, Ala776, on the polyprotein of encephalomyocarditis virus. Diabetes. 1993;42:435–443. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahk Y Y, Kappel C A, Rasmussen G, Kim B S. Association between susceptibility to Theiler’s virus-induced demyelination and T-cell receptor Jβ1-Cβ1 polymorphism rather than Vβ deletion. J Virol. 1997;71:4181–4185. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.4181-4185.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bureau J F, Montagutelli X, Lefebvre S, Guenet J L, Pla M, Brahic M. The interaction of two groups of murine genes determines the persistence of Theiler’s virus in the central nervous system. J Virol. 1992;66:4698–4704. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4698-4704.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calenoff M A, Faaberg K S, Lipton H L. Genomic regions of neurovirulence and attenuation in Theiler murine encephalomyelitis virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:978–982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H H, Kong W P, Zhang L, Ward P L, Roos R P. A picornaviral protein synthesized out of frame with the polyprotein plays a key role in a virus-induced immune-mediated demyelinating disease. Nat Med. 1995;1:927–931. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clatch R J, Lipton H L, Miller S D. Characterization of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity responses in TMEV-induced demyelinating disease: correlation with clinical signs. J Immunol. 1986;136:920–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clatch R J, Lipton H L, Miller S D. Class II-restricted T cell responses in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-induced demyelinating disease. II. Survey of host immune responses and central nervous system virus titers in inbred mouse strains. Microb Pathog. 1987;3:327–337. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crane M A, Jue C, Mitchell M, Lipton H, Kim B S. Detection of restricted predominant epitopes of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus capsid proteins expressed in the lambda gt11 system: differential patterns of antibody reactivity among different mouse strains. J Neuroimmunol. 1990;27:173–186. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(90)90067-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crane M A, Yauch R, Dal Canto M C, Kim B S. Effect of immunization with Theiler’s virus on the course of demyelinating disease. J Neuroimmunol. 1993;45:67–73. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(93)90165-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dal Canto M C, Kim B S, Miller S D, Melvold R W. Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-induced demyelination: a model for human multiple sclerosis. Methods. 1996;10:453–461. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dal Canto M C, Lipton H L. Primary demyelination in Theiler’s virus infection. An ultrastructural study. Lab Invest. 1975;33:626–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dal Canto M C, Lipton H L. Ultrastructural immunohistochemical localization of virus in acute and chronic demyelinating Theiler’s virus infection. Am J Pathol. 1982;106:20–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedmann A, Frankel G, Lorch Y, Steinman L. Monoclonal anti-I-A antibody reverses chronic paralysis and demyelination in Theiler’s virus-infected mice: critical importance of timing of treatment. J Virol. 1987;61:898–903. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.3.898-903.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedmann A, Lorch Y. Theiler’s virus infection: a model for multiple sclerosis. Prog Med Virol. 1985;31:43–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerety S J, Karpus W J, Cubbon A R, Goswami R G, Rundell M K, Peterson J D, Miller S D. Class II-restricted T cell responses in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus-induced demyelinating disease. V. Mapping of a dominant immunopathologic VP2 T cell epitope in susceptible SJL/J mice. J Immunol. 1994;152:908–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerety S J, Rundell M K, Dal Canto M C, Miller S D. Class II-restricted T cell responses in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus-induced demyelinating disease. VI. Potentiation of demyelination with and characterization of an immunopathologic CD4+ T cell line specific for an immunodominant VP2 epitope. J Immunol. 1994;152:919–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue A, Choe Y K, Kim B S. Analysis of antibody responses to predominant linear epitopes of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus. J Virol. 1994;68:3324–3333. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3324-3333.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarousse N, Grant R A, Hogle J M, Zhang L, Senkowski A, Roos R P, Michiels T, Brahic M, McAllister A. A single amino acid change determines persistence of a chimeric Theiler’s virus. J Virol. 1994;68:3364–3368. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3364-3368.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karpus W J, Peterson J D, Miller S D. Anergy in vivo: down-regulation of antigen-specific CD4+ Th1 but not Th2 cytokine responses. Int Immunol. 1994;6:721–730. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.5.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim B S, Choe Y K, Crane M A, Jue C R. Identification and localization of a limited number of predominant conformation-independent antibody epitopes of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus. Immunol Lett. 1992;31:199–205. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(92)90146-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klenerman P, Rowland-Jones S, McAdam S, Edwards J, Daenke S, Lalloo D, Koppe B, Rosenberg W, Boyd D, Edwards A, et al. Cytotoxic T-cell activity antagonized by naturally occurring HIV-1 Gag variants. Nature. 1994;369:403–407. doi: 10.1038/369403a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehrich J R, Arnason B G, Hochberg F H. Demyelinative myelopathy in mice induced by the DA virus. J Neurol Sci. 1976;29:149–160. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(76)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipton H L. Persistent Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus infection in mice depends on plaque size. J Gen Virol. 1980;46:169–177. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-46-1-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipton H L. Theiler’s virus infection in mice: an unusual biphasic disease process leading to demyelination. Infect Immun. 1975;11:1147–1155. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.5.1147-1155.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipton H L, Canto C D. Contrasting effects of immunosuppression on Theiler’s virus infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1977;15:903–909. doi: 10.1128/iai.15.3.903-909.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipton H L, Dal Canto M C. Chronic neurologic disease in Theiler’s virus infection of SJL/J mice. J Neurol Sci. 1976;30:201–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(76)90267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipton H L, Friedmann A. Purification of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus and analysis of the structural virion polypeptides: correlation of the polypeptide profile with virulence. J Virol. 1980;33:1165–1172. doi: 10.1128/jvi.33.3.1165-1172.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipton H L, Melvold R. Genetic analysis of susceptibility to Theiler’s virus-induced demyelinating disease in mice. J Immunol. 1984;132:1821–1825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAllister A, Tangy F, Aubert C, Brahic M. Genetic mapping of the ability of Theiler’s virus to persist and demyelinate. J Virol. 1990;64:4252–4257. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4252-4257.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicholson L B, Greer J M, Sobel R A, Lees M B, Kuchroo V K. An altered peptide ligand mediates immune deviation and prevents autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Immunity. 1995;3:397–405. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohara Y, Stein S, Fu J L, Stillman L, Klaman L, Roos R P. Molecular cloning and sequence determination of DA strain of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis viruses. Virology. 1988;164:245–255. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90642-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palma J P, Park S H, Kim B S. Treatment with lipopolysaccharide enhances the pathogenicity of a low-pathogenic variant of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus. J Neurosci Res. 1996;45:776–785. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960915)45:6<776::AID-JNR14>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pevear D C, Calenoff M, Rozhon E, Lipton H L. Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of the picornavirus Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus indicates that it is closely related to cardioviruses. J Virol. 1987;61:1507–1516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1507-1516.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pircher H, Rohrer U H, Moskophidis D, Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. Lower receptor avidity required for thymic clonal deletion than for effector T-cell function. Nature. 1991;351:482–485. doi: 10.1038/351482a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pullen L C, Park S H, Miller S D, Dal Canto M C, Kim B S. Treatment with bacterial LPS renders genetically resistant C57BL/6 mice susceptible to Theiler’s virus-induced demyelinating disease. J Immunol. 1995;155:4497–4503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez M, David C S. Demyelination induced by Theiler’s virus: influence of the H-2 haplotype. J Immunol. 1985;135:2145–2148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez M, Lafuse W P, Leibowitz J, David C S. Partial suppression of Theiler’s virus-induced demyelination in vivo by administration of monoclonal antibodies to immune-response gene products (Ia antigens) Neurology. 1986;36:964–970. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.7.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez M, Leibowitz J, Lampert P. Persistent infection of oligodendrocytes in Theiler’s virus induced encephalomyelitis. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:426–433. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roos R P, Firestone S, Wollmann R, Variakojis D, Arnason B G. The effect of short-term and chronic immunosuppression on Theiler’s virus demyelination. J Neuroimmunol. 1982;2:223–234. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(82)90057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roos R P, Stein S, Routbort M, Senkowski A, Bodwell T, Wollmann R. Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus neutralization escape mutants have a change in disease phenotype. J Virol. 1989;63:4469–4473. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4469-4473.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheu A K, Cuesta A, Rubio N. Characterization of the immune response to intracerebral inoculation of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus: fine protein specificity of the splenic T cell and humoral antibody response. Immunol Lett. 1989;21:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(89)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sloan-Lancaster J, Evavold B D, Allen P M. Induction of T-cell anergy by altered T-cell-receptor ligand on live antigen-presenting cells. Nature. 1993;363:156–159. doi: 10.1038/363156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stein S B, Zhang L, Roos R P. Influence of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus 5′ untranslated region on translation and neurovirulence. J Virol. 1992;66:4508–4517. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4508-4517.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tangy F, McAllister A, Aubert C, Brahic M. Determinants of persistence and demyelination of the DA strain of Theiler’s virus are found only in the VP1 gene. J Virol. 1991;65:1616–1618. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1616-1618.1991. . (Erratum, 1993.) 67:2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Theiler M. Spontaneous encephalomyelitis of mice-a new virus disease. Science. 1934;80:122. doi: 10.1126/science.80.2066.122-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Theiler M, Gard S. Encephalomyelitis of mice. J Exp Med. 1940;72:49–67. doi: 10.1084/jem.72.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welsh C J, Tonks P, Nash A A, Blakemore W F. The effect of L3T4 T cell depletion on the pathogenesis of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus infection in CBA mice. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:1659–1667. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-6-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yahikozawa H, Inoue A, Koh C S, Choe Y K, Kim B S. Major linear antibody epitopes and capsid proteins differentially induce protective immunity against Theiler’s virus-induced demyelinating disease. J Virol. 1997;71:3105–3113. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3105-3113.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yauch R L, Kerekes K, Saujani K, Kim B S. Identification of a major T-cell epitope within VP3 amino acid residues 24 to 37 of Theiler’s virus in demyelination-susceptible SJL/J mice. J Virol. 1995;69:7315–7318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7315-7318.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yauch R L, Kim B S. A predominant viral epitope recognized by T cells from the periphery and demyelinating lesions of SJL/J mice infected with Theiler’s virus is located within VP1(233–244) J Immunol. 1994;153:4508–4519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zinkernagel R M. Immunology taught by viruses. Science. 1996;271:173–178. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zurbiggen A, Hogle J, Fujinami R. Alteration of amino acid 101 within capsid protein VP1 changes the pathogenicity of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus. J Exp Med. 1989;170:2037–2049. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]