Abstract

Background

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a critical life-saving procedure in managing cardiac arrest, with its success largely dependent on the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of healthcare providers. This study aimed to evaluate CPR-related KAP among anesthesia providers in public hospitals in Sana’a City, Yemen, and to explore the associations between demographic characteristics and KAP levels.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 226 anesthesia providers using a standardized, structured questionnaire consisting of 12 knowledge items, 7 attitude items, and 12 practice items. Data were analyzed with descriptive statistics and correlation analysis to examine associations between demographic factors and KAP levels.

Results

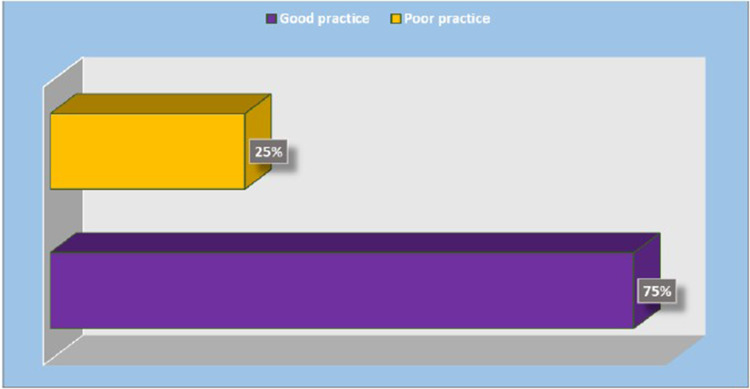

Among participants, 60% demonstrated adequate knowledge, 30% had moderate knowledge, and 10% had inadequate knowledge of CPR. Positive attitudes toward CPR were reported by 85% of providers, while 15% exhibited negative attitudes. Good CPR practices were observed by 75% of respondents, with 25% showing poor practices. Significant positive correlations were found between knowledge and attitudes (r = 0.312, p < 0.01), knowledge and practices (r = 0.365, p < 0.01), and attitudes and practices (r = 0.289, p < 0.01). Better KAP scores were significantly associated with younger age, recent training, and higher educational attainment.

Conclusion

This study highlights the current levels of knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) regarding CPR among anesthesia providers in public hospitals in Sana’a as one of the first studies. While most participants demonstrated adequate knowledge, positive attitudes, and good practices, notable gaps persist—particularly among older providers and those without recent training. The positive correlations among the KAP components emphasize the need for regular, targeted educational interventions to enhance CPR competence and improve patient outcomes. Ensuring that anesthesia providers and healthcare workers maintain up-to-date CPR knowledge and practical skills is critical for increasing survival rates during cardiac arrest. Implementing mandatory CPR certification or re-certification every 2–3 years could systematically sustain and improve knowledge, attitudes, and practices.

Keywords: attitude, cardiopulmonary, knowledge, resuscitation, practice

Introduction

Cardiopulmonary arrest is a life-threatening medical emergency requiring immediate intervention through cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).1 It represents a significant global health burden, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where limited resources and inadequate healthcare infrastructure often hinder timely and effective treatment. CPR, which combines chest compressions and ventilation, is vital to preventing irreversible organ damage and improving survival outcomes following cardiac arrest.2 The knowledge and proficiency of healthcare providers in performing CPR are crucial to delivering high-quality resuscitation and ensuring favorable patient outcomes. Mastery of both Basic Life Support (BLS) and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) protocols is essential for effective management of cardiac emergencies.3 However, evidence shows a persistent global deficit in CPR knowledge and skills among healthcare professionals, underscoring the urgent need for standardized training and ongoing skill reinforcement to maintain clinical competency and readiness in emergency situations.4

Several studies have explored factors influencing CPR knowledge among healthcare providers. In Kuwait, age, gender, years of experience, and prior formal CPR training were significantly associated with knowledge levels.5 Similar patterns were observed in Nigeria and Jamaica, where younger providers and those with less clinical seniority exhibited greater CPR knowledge and confidence.6,7 Conversely, research in Nepal and Pakistan identified inadequate training as a primary barrier to effective CPR performance among medical personnel.8 Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for nearly 30% of global mortality. Sudden cardiac death, often due to cardiac arrest, contributes to nearly half of these fatalities, underscoring the critical public health threat it poses.9 Effective management of cardiac arrest relies on adherence to well-established evidence-based protocols, with CPR recognized universally as a vital life-saving intervention in both hospital and pre-hospital settings. Regional in-hospital cardiac arrest survival rates range from 10.8% to 22% and given Yemen’s severe shortages of trained personnel and resuscitation resources, it is likely that survival outcomes are even lower. This reality highlights the urgent need for structured, recurrent CPR training for anesthesia providers and frontline healthcare workers.10

Despite advancements in healthcare systems, gaps in CPR knowledge, attitudes, and practices continue to challenge healthcare providers, especially in resource-limited settings. These challenges are further intensified in developing countries, where systemic limitations hinder timely responses to cardiac arrest. Therefore, possessing fundamental CPR knowledge, practical skills, and a proactive attitude is essential for healthcare providers to achieve optimal outcomes in emergency situations.11 Assessing the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of anesthesia providers regarding CPR in Yemen is particularly critical given the unique challenges of the local context, especially within government hospitals in Sana’a. The ongoing conflict and persistent economic instability have severely weakened the healthcare system, causing widespread shortages of medical supplies, limited access to updated training, and inadequate infrastructure. These systemic issues directly impact the preparedness of medical personnel, including anesthesia providers, to manage cardiac emergencies effectively.12

The lack of adequate training resources and institutional support has likely compromised CPR competency among healthcare providers in Yemen, increasing the risk to patients during life-threatening emergencies. Addressing these deficiencies requires targeted efforts to enhance medical education, expand access to training, and reinforce best practices in emergency care. Understanding healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward CPR is also crucial for designing effective training programs that improve the responsiveness and efficacy of emergency interventions.13 The American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines have significantly influenced global CPR standards and provide a valuable framework for improving CPR knowledge, attitudes, and practices among anesthesia providers in Sana’a’s public hospitals. AHA-based training programs have demonstrated improved CPR performance and increased survival rates in cardiac arrest scenarios, especially in intensive care settings.14 However, recent research highlights substantial gaps in CPR knowledge and skills among healthcare providers in the Middle East, including limited awareness and training among anesthesia staff.15 Furthermore, the practical application of CPR training is strongly influenced by healthcare providers’ attitudes, emphasizing the need to cultivate a positive mindset toward emergency response practices.16,17 To effectively bridge these gaps, comprehensive and regularly updated training programs coupled with systematic competency assessments are essential. Such initiatives can help sustain CPR proficiency and ultimately improve patient outcomes during critical emergencies.18,19

Furthermore, Studies across different countries reveal widespread gaps in CPR knowledge, attitudes, and practical skills among healthcare professionals, with many showing low levels of training, confidence, and competence in performing CPR effectively.20,21 This study addresses the critical need to assess cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) among anesthesia providers in Yemen, a country facing significant healthcare challenges due to conflict and limited training opportunities. Understanding these factors is essential for identifying gaps and improving CPR competence. The findings will support the development of standardized, evidence-based CPR protocols and targeted training programs in public hospitals. By exploring the relationships between knowledge, attitudes, and practices, this research aims to pinpoint key influences on CPR performance and propose interventions to enhance provider preparedness, ultimately improving patient outcomes in cardiac emergencies across Yemen’s healthcare system.

Research Questions

-

1)

What is the current level of knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) among anesthesia providers in public hospitals in Sana’a, Yemen?

-

2)

How do demographic factors (such as age, gender, years of experience, and educational level) influence the CPR-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices of anesthesia providers?

-

3)

What are the key gaps in CPR knowledge, attitudes, and practices that need to be addressed through targeted training programs in this population?

-

4)

How can the findings inform policy development and the implementation of effective CPR training strategies for anesthesia providers in Yemen?

Methods

Study Design and Study Setting

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) among anesthesia providers in Sana’a City, Yemen, and to assess the relationship between demographic characteristics and KAP levels. The study targeted anesthesia providers working in the operating theaters of public hospitals. Data were collected from eight major public hospitals in Sana’a, selected for their central role in delivering surgical and anesthesia services within the public healthcare system. These hospitals included Al-Thowra Modern General Hospital, Al-Republican Teaching Hospital Authority, Al-Kuwait University Hospital, Al-Sabean Hospital, 22 May Hospital, General Police Hospital, Typical Police Hospital, and Palestine Hospital for Maternity. Together, these institutions provided a representative setting to assess CPR-related knowledge and practices among frontline anesthesia professionals in the public sector.

Study Population and Sample

The study population consisted of 439 anesthesia providers working in the operating theaters of selected public hospitals in Sana’a City, based on 2023 data from the Yemen Medical Council. The required sample size was calculated using EpiCalc statistical software, with a 50% expected frequency, 95% confidence level, and 5% margin of error, resulting in a final sample size of 226 participants. Inclusion criteria included male and female anesthesia providers who were actively working in operating theaters, had at least one year of professional experience, and provided informed consent to participate. Providers not meeting these criteria were excluded.

Sampling Methods

A two-stage random sampling technique was employed to account for the clustered nature of the population, optimize resource use, and enhance the generalizability of the findings. In the first stage, eight hospitals were randomly selected from a list of fifteen public hospitals operating in Sana’a City, serving as primary sampling units (PSUs). In the second stage, anesthesia providers were selected from each chosen hospital using probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling, with individual providers serving as secondary sampling units (SSUs). This approach ensured proportional representation based on hospital size, minimized selection bias, and improved the reliability of the results.

Study Instrument

The data collection instrument was an adapted standardized questionnaire based on previously published studies and guidelines related to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP).10,22,23 The adaptation involved a thorough literature review and item selection to ensure relevance to the Yemeni context. A pilot test with a small group of anesthesia providers assessed clarity, relevance, and feasibility. Expert reviews by anesthesia and CPR specialists confirmed face validity and alignment with study objectives. Content validity was further established by comparing the questionnaire with established CPR guidelines and KAP studies. These assessments demonstrated that the adapted questionnaire was suitable and valid for the study.

The standardized questionnaire used for data collection consisted of 31 items designed to assess respondents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). It was divided into four parts: Part 1 collected socio-demographic data, including age, sex, educational level, marital status, years of experience, and prior CPR training (Table 1); Part 2 assessed knowledge with 12 items; Part 3 evaluated attitudes with 7 items; and Part 4 examined practices with 12 items. The scoring system was adapted from previous studies by Mersha et al, Alfatlawi et al and Mekonnen et al.11,16,22 Knowledge items were scored 1 for correct and 0 for incorrect answers, with knowledge classified as adequate (9–12 correct, ≥75%), moderate (6–8 correct, 50–74%), or inadequate (0–5 correct, <50%). Attitudes were categorized as positive (5–7 positive responses) or negative (0–4 positive responses). Practice items were scored as “Yes” or “No” with good practice defined as 9–12 correct responses (≥75%) and poor practice as 0–8 correct (<75%).

Table 1.

Anesthesia Providers’ Demographic Characteristics. (n=226)

| Demographic Characteristic | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20-30 | 144 | 68.1 |

| 31-40 | 42 | 18.6 | |

| 41-50 | 30 | 13.3 | |

| >50 | 10 | 4.4 | |

| Sex | Male | 158 | 69.9 |

| Female | 68 | 30.1 | |

| Education levels | Anesthesiologist Assistant | 14 | 6.2 |

| Bachelor of Anesthesia Technology | 64 | 28.3 | |

| Consultant | 8 | 3.5 | |

| Diploma | 98 | 43.4 | |

| Senior Specialist | 42 | 18.6 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 114 | 50.5 |

| Married | 112 | 49.5 | |

| Years of Experience | 1-3 years | 50 | 22.1 |

| 4-6 years | 120 | 53.1 | |

| 7-9 years | 36 | 15.9 | |

| ≥ 10 years | 20 | 8.8 | |

| CPR Training | Never | 34 | 15.0 |

| One Time | 64 | 28.3 | |

| Two Times | 42 | 18.6 | |

| Three Times or More | 86 | 38.1 | |

| Last Training | < 1 year | 88 | 38.9 |

| 1-2 years | 40 | 17.7 | |

| ≥ 3 years | 64 | 28.3 | |

| Never | 34 | 15.0 | |

| Hospital | 22 May Hospital | 14 | 6.2 |

| Al-Kuwait Hospital | 26 | 11.5 | |

| Al-Sabean Hospital | 24 | 10.6 | |

| Al-Thawra Hospital | 72 | 31.9 | |

| General Policy Hospital | 18 | 8.0 | |

| Palestine Hospital | 14 | 6.2 | |

| Republican Hospital | 38 | 16.8 | |

| Typical Police Hospital | 20 | 8.8 | |

Notes: The demographic characteristics of the anesthesia providers in the study. The majority of participants fall within the age group of 20–30 years (68.1%), with the next largest group aged 31–40 years (18.6%). A significant proportion of participants are male (69.9%), while females constitute 30.1% of the sample. In terms of education, the largest group holds a diploma in anesthesia technology (43.4%), followed by those with a bachelor’s degree (28.3%). A smaller proportion are anesthesiologist assistants (6.2%) or consultants (3.5%). The highest number of participants are from Al-Thawra Hospital (31.9%), followed by Al-Kuwait Hospital (11.5%) and Republican Hospital (16.8%). Most participants are married (49.5%), while the remaining 50.5% are single. In terms of experience, the largest group has 4–6 years of professional experience (53.1%), with smaller groups having 1–3 years (22.1%) or 7–9 years (15.9%) of experience. Regarding CPR training, a significant proportion of participants have attended CPR training more than three times (38.1%), and many reported that their last training occurred within the past year (38.9%).

The reliability of the questionnaire was established through review by a panel of three anesthesiologists from Al-Razi University, who provided feedback for refinement. A pilot study was conducted with 26 participants, and the data collected during this pilot phase were included in the main study analysis. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding values of 0.70 for the knowledge section, 0.79 for the attitude section, and 0.80 for the practice section, indicating acceptable to good reliability. Data collection took place from February 1st to March 28th, 2024, with participants recruited through face-to-face interviews at the eight randomly selected hospitals in Sana’a City, Yemen. Eligible participants were anesthesia providers who met the inclusion criteria and provided informed consent. Ethical considerations were strictly observed to ensure confidentiality and participant safety throughout the study. Prior to completing the questionnaire, participants provided informed consent by responding “Yes” or “No” on a written form that outlined the study’s risks, benefits, and their rights, confirming voluntary participation. To protect confidentiality, participant data were anonymized and stored in encrypted files. The study received ethical approval from the Al-Razi University Ethics Committee.

Statistical Design

Data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. For continuous variables, the normality of their distribution was evaluated with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics for continuous data included the range (minimum and maximum values), mean, standard deviation, and median. To compare non-normally distributed quantitative variables between two independent groups, the Mann–Whitney U-test was utilized. For comparisons involving more than two independent groups, the Kruskal–Wallis H-test was applied. The strength and direction of correlations between two non-normally distributed continuous variables were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r). A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was used for all statistical analyses.

Discussion

The knowledge of anesthesia providers regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is critical for delivering effective patient care during cardiac emergencies. This study reveals significant gaps in CPR knowledge that could adversely affect the quality of resuscitation, underscoring the need for targeted educational interventions. Our findings (Table 2; Figure 1) indicate that 60% of anesthesia providers possess adequate CPR knowledge, less than one-third have moderate knowledge, and less than one-quarter have inadequate knowledge. While the majority of providers demonstrate solid training, these gaps highlight areas for improvement. Compared to studies in Ethiopia (25.1%),11 Kuwait (36%),5 Pakistan (44.85%),9 and Nigeria (36.9%),6 our study reports higher levels of adequate knowledge. This may be attributed to the specific focus on anesthesia providers, whereas the referenced studies included a broader spectrum of healthcare professionals.

Table 2.

Anesthesia Providers’ Knowledge Towards Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. (n=226)

| Questions | Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | Incorrect | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

|

136 | 60.2 | 90 | 39.8 | |

|

110 | 48.7 | 116 | 51.3 | |

|

90 | 39.8 | 136 | 60.2 | |

|

96 | 42.5 | 130 | 57.5 | |

|

64 | 28.3 | 162 | 71.7 | |

|

110 | 48.7 | 116 | 51.3 | |

|

200 | 88.5 | 26 | 11.5 | |

|

98 | 43.4 | 128 | 56.6 | |

|

42 | 18.6 | 180 | 79.6 | |

| 10) What do you do for patients experiencing respiratory arrest with a perfusing rhythm? | 122 | 54.0 | 104 | 46.0 | |

| 11) Interruptions in chest compressions should be limited to no longer than how many seconds? | 64 | 28.3 | 162 | 71.7 | |

| 12) The ACLS Survey includes assessing for what? | 68 | 30.1 | 158 | 69.9 | |

| Total Knowledge level | Adequate | 135 | 60% | ||

| Moderate | 68 | 30% | |||

| Inadequate | 23 | 10% | |||

Notes: A majority, 60.3%, were able to correctly interpret Electrocardiograms (ECGs). However, more than half of the participants answered incorrectly on key aspects of post-shock management, monitoring breathing during Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), transporting cardiac arrest patients, understanding critical stroke data, and managing cardiac arrest during pregnancy. On a more positive note, anesthesia providers performed better on certain knowledge items, with 88.5% correctly identifying the appropriate compression-to-ventilation ratio and 71.7% demonstrating an understanding of the limits on interrupting chest compressions during CPR. Furthermore, most anesthesia providers (60%) have adequate knowledge about CPR. However, 30% have moderate knowledge and 10% have inadequate knowledge.

Figure 1.

Total Anesthesia providers’ knowledge level towards Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. (n=226).

Notes: A majority of anesthesia providers (60%) have adequate knowledge about CPR. However, 30% have moderate knowledge and 10% have inadequate knowledge.

Nonetheless, 30% of providers with moderate knowledge and 10% with inadequate knowledge raise concerns about inconsistent training quality, outdated guidelines, and varying educational backgrounds.23 These findings are consistent with those of Alfatlawi et al21 and Tsegaye et al,24 who emphasize the need for regular, comprehensive training programs. Additionally, 60.2% of providers in this study correctly interpreted electrocardiograms (ECGs), a critical skill for managing cardiac arrest. However, nearly 40% lacked proficiency in ECG interpretation, highlighting a significant gap given its vital role in identifying cardiac rhythms and guiding appropriate interventions. Regular, focused ECG training is essential to improve accuracy and enhance patient outcomes during cardiac emergencies.25,26

Another concern is that only 39.8% of providers knew the recommended method for monitoring breathing during advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS). Effective ventilation is critical to prevent hypoxia and improve survival rates, as emphasized by the American Heart Association (AHA). This low percentage suggests that many providers may not be adhering to the latest ACLS guidelines, highlighting the urgent need for updated training programs focused on proper ventilation techniques.11 On a positive note, 88.5% of providers demonstrated knowledge of managing cardiac arrest during pregnancy, reflecting awareness of this high-risk population. However, training should also address other vulnerable groups, such as infants and the elderly, to ensure comprehensive preparedness.24 Conversely, only 18.6% of providers were aware of the most important intervention for witnessed sudden cardiac arrest, indicating a significant gap in understanding current CPR guidelines. This may stem from irregular updates to protocols, emphasizing the importance of ongoing education to keep providers informed of the most effective life-saving techniques.21

The attitudes of anesthesia providers toward CPR play a crucial role in their willingness and confidence to perform this lifesaving intervention. Our study (Table 3; Figure 2) found that more than two-thirds of anesthesia providers exhibited a positive attitude toward performing CPR, while less than one-quarter held a negative attitude. This aligns closely with findings from a study in Pakistan assessing basic life support (BLS) retention, where 84.8% of healthcare providers demonstrated a positive attitude.27 Positive attitudes are essential, as they significantly enhance providers’ readiness and confidence to act during emergencies, a relationship supported by studies from Iqbal et al25 and Alfatlawi et al.21 The high prevalence of positive attitudes suggests that most anesthesia providers in our study are prepared and motivated to perform CPR effectively, consistent with results reported by Mersha et al11 and Kumari et al.19 However, the less than one-quarter with negative attitudes highlight areas requiring further attention, as such attitudes may stem from fears of disease transmission, lack of confidence in CPR skills, or prior negative experiences.23

Table 3.

Anesthesia Providers’ Attitude Towards Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. (n=226)

| Questions Concerning the Attitude of Anesthesia Providers Regarding CPR: | Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Disagree | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

|

204 | 90.3 | 22 | 9.7 | |

|

44 | 19.5 | 182 | 80.5 | |

|

126 | 55.8 | 100 | 44.2 | |

|

72 | 31.9 | 144 | 68.1 | |

|

98 | 43.4 | 128 | 56.6 | |

|

188 | 87.6 | 28 | 12.4 | |

|

154 | 69.0 | 70 | 31.0 | |

| Total attitude level | Positive | 192 | 85% | ||

| Negative | 34 | 15% | |||

Notes: A significant majority (90.3%) believe that a lack of training negatively impacts their ability to initiate resuscitation. Most providers (80.5%) expressed reluctance to perform mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on all patients, with 55.8% citing concerns over disease transmission. However, 68.1% disagreed with the notion of avoiding mouth-to-mouth ventilation for the opposite sex during CPR. Additionally, 56.6% of providers felt that their CPR knowledge was inadequate. A strong majority (87.6%) supported the idea that CPR training should be mandatory for anesthesia students, and 69.0% believed that self-protection items, such as gloves and face masks, are essential for performing CPR. Moreover, 85% of anesthesia providers have positive attitudes toward performing CPR, while 15% have a negative attitude.

Figure 2.

Total Anesthesia providers’ attitudes level towards Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. (n=226).

Note: 85% of anesthesia providers have positive attitudes toward performing CPR, while 15% have a negative attitude.

A notable 90.3% of anesthesia providers believe that lack of training negatively impacts their ability to initiate resuscitation, underscoring the perceived importance of regular and comprehensive training to enhance both confidence and competence, as supported by previous studies.28 However, 80.5% expressed reluctance to perform mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, likely due to concerns about disease transmission. This finding aligns with other research and highlights the need for updated training that incorporates the latest safety protocols to alleviate fears and encourage effective resuscitation practices.29 Additionally, more than two-thirds of providers support mandatory CPR training for all anesthesia students, consistent with international standards aimed at ensuring new professionals acquire essential resuscitation skills.24 Despite this, less than half feel their CPR knowledge is insufficient, indicating a gap between theoretical learning and practical confidence. This points to the necessity of more hands-on, repetitive training to improve both skill retention and performance during emergencies.28

The practices of anesthesia providers are crucial for the effective management of cardiac emergencies. Our results (Table 4; Figure 3) indicate that more than two-thirds of anesthesia providers demonstrate good CPR practices, while one quarter exhibit poor practices. This level of proficiency is encouraging, suggesting that a majority can apply their knowledge effectively in real-life scenarios. Compared to a similar study in Ethiopia, where only half showed good CPR practices,16 our findings reflect a relatively higher level of competence. This discrepancy may be due to differences in the availability and quality of CPR training programs, the frequency of refresher courses, and exposure to real-life resuscitation cases. Notably, less than two-thirds of providers correctly administered the recommended dose of atropine during CPR, a critical aspect since atropine is often used to manage bradycardia in cardiac arrest. Proper medication administration is vital for successful resuscitation, and this relatively high adherence indicates that anesthesia providers generally have a solid understanding of pharmacological interventions during CPR.28

Table 4.

Anesthesia Providers’ Level of Practices Towards Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. (n=226)

| Questions Concerning the Practice of Anesthesia Providers Regarding CPR: | Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

|

152 | 67.3 | 74 | 32.7 | |

|

144 | 68.1 | 72 | 31.9 | |

|

168 | 74.3 | 58 | 25.7 | |

|

152 | 67.3 | 74 | 32.7 | |

|

148 | 65.5 | 78 | 34.5 | |

|

156 | 69.0 | 70 | 31.0 | |

|

166 | 73.5 | 60 | 26.5 | |

|

158 | 69.9 | 68 | 30.1 | |

|

102 | 45.1 | 124 | 54.9 | |

| 10) Pregnant women who are arrested (eclampsia) and receiving magnesium sulfate IV should they continue receiving it.? | 144 | 68.1 | 72 | 31.9 | |

| 11) The purpose of targeted temperature management after CPR is Protect the brain and other vital organs? | 194 | 85.8 | 32 | 14.2 | |

| 12) The recommended volume of lactated Ringer’s solution that should be given for the treatment of hypotension in the post-cardiac arrest phase is one-two liters? | 160 | 70.8 | 66 | 29.2 | |

| Total practice level | Good | 170 | 75% | ||

| Poor | 56 | 25% | |||

Notes: The majority (67.3%) correctly identified the recommended dose of 0.6mg atropine for cardiopulmonary resuscitation. A similar proportion (68.1%) knew the proper administration of epinephrine and amiodarone during Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS). Additionally, 74.3% of providers correctly answered about titrating ventilation to achieve a Carbon Dioxide (CO2) level of 35–45mmHg in the post-resuscitation phase. Another 67.3% correctly identified the recommended compression depth of 1/3 chest depth or 4cm for infants. However, 65.5% of providers were found to use excessive ventilation during CPR. In terms of defibrillation, 69% accurately stated the initial biphasic defibrillation energy of 120–200J for adults in cardiac arrest, and 73.5% knew the recommended ventilation rate of 10 breaths per minute with continuous chest compressions after advanced airway placement. Finally, 85.8% and 70.8% accurately identified the recommended volume of 1–2 liters of lactated Ringer’s solution for post-cardiac arrest hypotension. Moreover, 75% of anesthesia providers exhibit good CPR practices, whereas 25% have poor practices.

Figure 3.

Total Anesthesia providers’ practices levels towards Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. (n=226).

Note: 75% of anesthesia providers exhibit good CPR practices, whereas 25% have poor practices.

Similarly, less than three-quarters of providers correctly administered epinephrine and amiodarone following defibrillation shocks, reflecting a solid understanding of medication protocols during advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS). Epinephrine plays a crucial role in enhancing coronary and cerebral perfusion during resuscitation, while amiodarone is vital for managing ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia. The correct use of these medications in line with American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines indicates a high level of competence among the providers.26 However, some practical skills require improvement. For instance, only less than three-quarters of providers correctly identified the recommended chest compression depth for infants. Proper compression depth is essential for maintaining adequate blood circulation during CPR, and incorrect technique can substantially reduce resuscitation effectiveness. This highlights the need for more focused training on pediatric resuscitation techniques, which often require protocol modifications based on the patient’s age.26 Additionally, the study revealed variability in the quality of chest compressions, especially regarding compression rate and depth. While most providers recognize the importance of delivering high-quality compressions, maintaining consistency in practice remains challenging. Evidence shows that regular hands-on training combined with the use of real-time feedback devices during simulations can significantly improve the consistency and quality of chest compressions.30,31 Therefore, integrating these methods into CPR training programs could enhance provider performance and ultimately improve patient outcomes during resuscitation.

The relationship between demographic characteristics and the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of anesthesia providers regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) provides valuable insights into factors influencing CPR performance (Table 5). Younger providers, particularly those aged 20–30 years, tend to demonstrate better knowledge, attitudes, and practices, likely due to more recent training aligned with current CPR guidelines. This highlights the importance of continuous education to maintain up-to-date competencies.32 Male providers slightly outperform females in knowledge and practice scores, which may reflect underlying societal and cultural influences.5 Additionally, higher qualifications such as those held by consultants and senior specialists—are associated with superior KAP scores, suggesting that advanced education positively impacts CPR proficiency.11 Providers working in hospitals with established training programs, like Al-Thawra, exhibit higher KAP scores, emphasizing the critical role of institutional support and access to quality training resources in enhancing CPR performance.6,7

Table 5.

Association Between the Respondents’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics, Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Levels. (n=226)

| Items | Characteristics | Knowledge Mean (S.D) |

Attitudes Mean (S.D) |

Practices Mean (S.D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20-30 | 17.2 (2.1) | 8.6 (1.3) | 9.1 (1.5) |

| 31-40 | 16.9 (2.0) | 8.5 (1.2) | 9.0 (1.6) | |

| 41-50 | 15.8 (2.2) | 8.3 (1.4) | 8.8 (1.7) | |

| >50 | 15.5 (2.4) | 8.2 (1.5) | 8.5 (1.8) | |

| H (p value) | 0.05* | 0.12 | 0.10 | |

| Gender | Male | 17.0 (2.1) | 8.6 (1.2) | 9.1 (1.6) |

| Female | 16.8 (2.0) | 8.5 (1.3) | 9.0 (1.5) | |

| U (p value) | 0.03* | 0.14 | 0.02* | |

| Education levels | Anesthesiologist Assistant | 15.5 (2.3) | 8.2 (1.4) | 8.7 (1.7) |

| Bachelor of Anesthesia Technology | 17.1 (2.0) | 8.6 (1.2) | 9.1 (1.5) | |

| Consultant | 17.5 (1.8) | 8.8 (1.0) | 9.3 (1.4) | |

| Diploma | 16.8 (2.1) | 8.5 (1.3) | 9.0 (1.6) | |

| Senior Specialist | 17.2 (2.0) | 8.6 (1.2) | 9.1 (1.5) | |

| H (p value) | 0.02* | 0.11 | 0.03* | |

| Marital Status | Single | 17.1 (2.0) | 8.6 (1.2) | 9.1 (1.5) |

| Married | 16.8 (2.1) | 8.5 (1.3) | 9.0 (1.6) | |

| H (p value) | 0.05* | 0.13 | 0.06 | |

| Years of Experience | 1-3 years | 16.9 (2.1) | 8.5 (1.3) | 9.0 (1.6) |

| 4-6 years | 17.2 (2.0) | 8.6 (1.2) | 9.1 (1.5) | |

| 7-9 years | 16.8 (2.1) | 8.5 (1.3) | 9.0 (1.6) | |

| ≥ 10 years | 17.0 (2.1) | 8.6 (1.2) | 9.1 (1.5) | |

| (H p value) | 0.04* | 0.09 | 0.05* | |

| CPR Training | Never | 15.7 (2.3) | 8.3 (1.4) | 8.8 (1.7) |

| One Time | 16.8 (2.1) | 8.5 (1.3) | 9.0 (1.6) | |

| Two Times | 17.0 (2.1) | 8.6 (1.2) | 9.1 (1.5) | |

| Three Times or More | 17.2 (2.0) | 8.6 (1.2) | 9.1 (1.5) | |

| U (p value) | 0.02* | 0.11 | 0.03* | |

| Last Training | < 1 year | 17.0 (2.1) | 8.6 (1.3) | 9.1 (1.6) |

| 1-2 years | 16.8 (2.0) | 8.5 (1.2) | 9.0 (1.5) | |

| ≥ 3 years | 15.9 (2.2) | 8.4 (1.3) | 8.9 (1.6) | |

| Never | 16.8 (2.1) | 8.5 (1.3) | 9.0 (1.6) | |

| U (p value) | 0.03* | 0.12 | 0.04* |

Notes: Younger anesthesia providers (aged 20–30 years) exhibit the highest scores in knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding CPR. Male providers show slightly higher scores in both knowledge and practices compared to their female counterparts. In terms of education, consultants and senior specialists demonstrate superior knowledge and practices. Providers working at Al-Thawra and Al-Kuwait hospitals also scored higher. Single providers had marginally better scores than married ones, and those with 4–6 years of experience achieved the highest knowledge and practice scores. Moreover, frequent and recent training significantly enhances both knowledge and practice scores among anesthesia providers. *Statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Abbreviations: SD, Standard deviation; U, Mann Whitney test; H, H for Kruskal Wallis test; p, p value for comparing between the categories studied.

Interestingly, single providers tend to score slightly higher than married ones, likely due to increased flexibility for training and professional development.19 Experience also plays a significant role, with providers having 4–6 years of experience exhibiting the highest KAP scores. However, it is important to note that extensive experience without regular refresher courses can lead to skill degradation, highlighting the need for ongoing education and practice.17 The study also (Table 6) revealed identifies significant correlations between knowledge, attitude, and practice among anesthesia providers regarding CPR, highlighting the necessity of comprehensive and ongoing training. A moderate positive correlation between knowledge and attitude (r = 0.312, p < 0.01) suggests that better knowledge of CPR is associated with more positive attitudes towards performing it. This finding is consistent with those of Mohammed et al32 and Mekonnen et al,22 and it emphasizes the role of education in fostering positive attitudes, which are crucial for effective resuscitation efforts. The study recognizes potential confounders and biases affecting the links between demographics and CPR knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Factors like unequal training access, clinical exposure, and unmeasured variables may have influenced results. Self-reported data could also be affected by recall and social desirability biases. Future research should use multivariate and longitudinal methods to better control these issues and clarify causal relationships.

Table 6.

Correlation Between Respondents’ Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Scores. (n=226)

| Variables | r (p-value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Attitude | Practices | |

| Knowledge | 1.00 | 0.312* | 0.365* |

| Attitude | 0.312* | 1.00 | 0.289* |

| Practices | 0.365* | 0.289* | 1 |

Notes: The correlation analysis in Table 6 reveals significant positive relationships between knowledge, attitudes, and practices among anesthesia providers regarding CPR. Higher levels of knowledge are strongly correlated with better CPR practices (r = 0.365, p < 0.01) and moderately correlated with a positive attitude (r = 0.312, p < 0.01). Additionally, a positive attitude moderately correlates with better CPR practices (r = 0.289, p < 0.01). These findings emphasize the critical role of continuous education and hands-on training in improving both the attitudes and practices of anesthesia providers. Well-designed training programs that blend theoretical knowledge with practical simulations are crucial in fostering positive attitudes and enhancing CPR practices, leading to improved patient outcomes during cardiac emergencies. *Statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Abbreviations: r, Spearman coefficient; p, p value for comparing between the categories studied.

Furthermore, a strong positive correlation between knowledge and practices (r = 0.365, p < 0.01) reveals that higher knowledge directly translates into improved CPR practices, a finding aligned with Tsegaye et al.24 This emphasizes the importance of integrating theoretical knowledge with hands-on training to ensure that providers can apply CPR effectively in real-life emergencies. Additionally, a moderate positive correlation between attitude and practice (r = 0.289, p < 0.01) suggests that positive attitudes toward CPR contribute to better practical implementation of resuscitation techniques. This finding supports research by Sajjan et al23 and Iqbal et al,25 which indicates that fostering a positive attitude towards CPR can lead to improved performance in actual practice, reinforcing the need for a supportive learning environment and continuous professional development.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the use of interviewer-administered questionnaires may introduce social desirability bias, as participants might have provided responses they perceived as favorable rather than fully accurate. Second, the findings are based on a cross-sectional design, which captures knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) at a single point in time and cannot establish causality. Third, the study was conducted exclusively among anesthesia providers in public hospitals in Sana’a City, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other healthcare settings, private institutions, or rural areas in Yemen. Finally, while efforts were made to ensure honest responses, interviewer-administered data inherently carry the risk of recall bias.

Conclusions

This study reveals significant gaps in knowledge, as well as variability in attitudes and practices related to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) among anesthesia providers. These findings highlight the urgent need for continuous education, regular hands-on training, and supportive institutional environments to strengthen CPR competency among healthcare providers. Although most providers demonstrate adequate knowledge and positive attitudes, critical deficiencies persist in essential areas such as proper ventilation techniques and post-shock medication management. Such gaps could compromise the quality of CPR and negatively affect patient outcomes during cardiac emergencies. Based on these findings, recommend implementing mandatory, periodic CPR training programs, particularly targeting providers with limited experience or those who have not received recent training. Training curricula should incorporate interactive, simulation-based approaches such as mannequin use or virtual reality simulations to better prepare providers for real-life resuscitation scenarios. Moreover, addressing concerns like fear of disease transmission during mouth-to-mouth resuscitation through updated safety protocols and availability of protective equipment can increase providers’ confidence and willingness to perform life-saving interventions.

The implications for healthcare are significant. Ensuring that anesthesia providers and healthcare workers in general maintain up-to-date CPR knowledge and practical skills is critical for improving patient survival rates during cardiac arrest. Incorporating Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) training, mandating CPR certification or recertification every 2–3 years can systematically sustain and enhance knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Regular, high-quality training reduces errors, improves resuscitation outcomes, and elevates the overall quality of emergency care. Cultivating positive attitudes and confidence in CPR performance helps prevent delays in time-sensitive, life-saving interventions. At the institutional level, these findings emphasize the importance of policy-driven measures that promote a culture of continuous learning and ensure ongoing access to CPR training resources. Such initiatives will enhance both individual competencies and the collective effectiveness of healthcare teams managing cardiac emergencies. From a policy perspective, integrating CPR competency assessments into routine professional evaluations will maintain CPR as a core component of healthcare provider development. Ultimately, reinforcing CPR knowledge and practice will substantially reduce preventable deaths from cardiac arrest, improve patient outcomes, and contribute to more effective healthcare delivery systems.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025). We would like to thank all the Anesthesia Providers who agreed to participate in this study.

Funding Statement

This study received conditional financial support from the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University after publishing.

Clinical Trial Number

This study is not a clinical trial, and therefore, a Clinical Trial Number is not applicable.

Abbreviations

AHA, American Heart Association; KAP, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices; CPR, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation; ACLS, Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support; ECG, Electrocardiogram; SPSS, Statistical Package for Social Sciences.

Data Sharing Statement

The data is accessible, and the corresponding author can furnish it upon receiving a reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee for Research of Al-Razi University (10/2023. Ref: RU/ 012/FMHS/2023). Maintaining confidentiality, the participants provided their written informed consent by signing a consent form before they were allowed to complete the questionnaire.

Consent for Publication

All authors have given their consent for the publication of this manuscript. Additionally, the study participants provided informed consent for the use of their data in research and publication.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare no competing interests in this work.

References

- 1.Ewy GA. The cardiocerebral resuscitation protocol for treatment of out-of-hospital primary cardiac arrest. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2012;20:65. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-20-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2015;132(18_suppl_2):S315–S367. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mansour A, Alsager AH, Alasqah A, et al. Student’s knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to cardiopulmonary resuscitation at Qassim University, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2019;11(11):e6169. PMID: 31890377; PMCID: PMC6913931. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meaney PA, Bobrow BJ, Mancini ME, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality: improving cardiac resuscitation outcomes both inside and outside the hospital: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128(4):417–435. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829d8654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alkandari SA, Alyahya L, Abdulwahab M. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge and attitude among general dentists in Kuwait. World J Emerg Med. 2017;8(1):19. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ihunanya OM, Oke Michael RN, Babcock BN, Amere LT, Rphn B. Knowledge, attitude and practice of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among nurses in Babcock University Teaching Hospital in Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State, Nigeria. Int J Caring Sci. 2020;13(3):1773–1782. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tíscar-González V, Blanco-Blanco J, Gea-Sánchez M, Molinuevo AR, Moreno-Casbas T. Nursing knowledge of and attitude in cardiopulmonary arrest: cross-sectional survey analysis. Peer J. 2019;7:e6410. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roshana S, Batajoo KH, Piryani RM, Sharma MW. Basic life support: knowledge and attitude of medical/paramedical professionals. World J Emerg Med. 2012;3(2):141. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2012.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alam T, Khattak YJ, Anwar M, Khan AA. Basic life support: a questionnaire survey to assess proficiency of radiologists and radiology residents in managing adult life support in cardiopulmonary arrest and acute anaphylactic reaction. Emerg Med Int. 2014;2014:356967. doi: 10.1155/2014/356967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong CX, Brown A, Lau DH, et al. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: global and regional perspectives. Heart Lung Circulation. 2019;28(1):6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2018.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mersha AT, Egzi AH, Tawuye HY, Endalew NS. Factors associated with knowledge and attitude towards adult cardiopulmonary resuscitation among healthcare professionals at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: an institutional-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e037416. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aser MA, Abdullah H, El-Jedi AY. Effectiveness of training programme on the quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among health care providers in critical care units at Governmental Hospitals in Gaza Strip. J Med Health Studies. 2023;4(4):145–154. doi: 10.32996/jmhs.2023.4.4.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alsabri MA, Alqeeq BF, Elshanbary AA, Soliman Y, Zaazouee MS, Yu R. Knowledge and skill level among non-healthcare providers regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) training in the Middle East (Arab countries): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2081. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-19575-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baklola M, Elnemr M, Ghazy M, et al. Assessing basic life support awareness, and knowledge among university undergraduates: a cross-sectional study. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2025;87(3):1251–1258. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000003076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Enizi BA, Saquib N, Zaghloul MS, Alaboud MS, Shahid MS, Saquib J. Knowledge and attitudes about basic life support among secondary school teachers in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Sci. 2016;10(3):415–422. PMID: 27610065; PMCID: PMC5003585. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alfatlawi WR, Ali ZM, Aldabagh MA. Impact of vitamin D elements in insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes mellitus (Dm2). Med-Leg. 2021;21(1):1581. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendhe HG, Burra L, Singh D, Narni H. Knowledge, attitude and practice study on cardiopulmonary resuscitation among medical and nursing interns. Int J Commun Med Public Health. 2017;4(8):3026. doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20173366 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar A, Avishay DM, Jones CR, et al. Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2021;22(1):147–158. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm.2021.01.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumari D, Chandran T, Philip BA. Knowledge, attitude and behavior of undergraduate dental students towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a descriptive study. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2020;14(3). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nasser BA, Idris J, Mesned AR, Mohamad T, Kabbani MS, Alakfash A. Predictors of cardio pulmonary resuscitation outcome in postoperative cardiac children. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2016;28(4):244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jsha.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abebe TA, Zeleke LB, Assega MA, Sefefe WM, Gebremedhn EG. Health-care providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding adult cardiopulmonary resuscitation at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Gojjam, Northwest Ethiopia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2021;14:647–654. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S293648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelkay MM, Kassa H, Birhanu Z, Amsalu S. A cross sectional study on knowledge, practice and associated factors towards basic life support among nurses working in amhara region referral hospitals, northwest Ethiopia, 2016. Hos Pal Med Int Jnl. 2018;2(2):123–130. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sajjan SV, Reddy A, Shingade PP. Knowledge, attitude and practices of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among medical interns & junior residents. Panacea J Med Sci. 2023;12(3):520–523. doi: 10.18231/j.pjms.2022.098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsegaye W, Tesfaye M, Alemu M. Knowledge, attitude and practice of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and associated factors in Ethiopian university medical students. J En Pract. 2015;3(206):2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iqbal A, Nisar I, Arshad I, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation: knowledge and attitude of doctors from Lahore. Ann Med Surg. 2021;69:102600. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ansari Y, Mourad O, Qaraqe K, Serpedin E. Deep learning for ECG Arrhythmia detection and classification: an overview of progress for period 2017–2023. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1246746. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2023.1246746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ilyas R, Shah-e-Zaman K, Pradhan N, et al. Retention of knowledge and skills of basic life support among health care providers trained in tertiary care hospital. Pakistan Heart J. 2014;47(1). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abolfotouh MA, Alnasser MA, Berhanu AN, Al-Turaif DA, Alfayez AI. Impact of basic life-support training on the attitudes of health-care workers toward cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation. BMC Health Services Res. 2017;17(1):674. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2621-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomas N, Kachekele ZA. Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice of cardiopulmonary resuscitation at a selected training hospital in Namibia: a cross-sectional survey. SAGE Open Nurs. 2023;9:23779608231216809. doi: 10.1177/23779608231216809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olajumoke TO, Afolayan JM, Raji SA, Adekunle MA. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation-knowledge, attitude & practices in Osun state, Nigeria. J West Afr Coll Surgeons. 2012;2(2):23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chew KS, Hashairi FM, Zarina ZI, Farid AS, Yazid MA, Hisamudddin NA. A survey on the knowledge, attitude and confidence level of adult cardiopulmonary resuscitation among junior doctors in Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia and Hospital Raja Perempuan Zainab II, Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 2011;66(1):56–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohammed Z, Arafa A, Saleh Y, et al. Knowledge of and attitudes towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation among junior doctors and medical students in Upper Egypt: cross-sectional study. Int J Emerg Med. 2020;13(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12245-020-00277-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data is accessible, and the corresponding author can furnish it upon receiving a reasonable request.