Abstract

Introduction

An increasing incidence in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syphilis coinfection has been observed in recent years.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the prevalence and characteristics of HIV diagnosis among patients with syphilis hospitalized from 2015 to 2022 at the Department of Dermatology.

Material and methods

This is a single-centre retrospective cohort study regarding adult patients diagnosed with syphilis and HIV. Data were collected from patient medical records and subsequently analysed to identify patterns and associations among patients with coinfection.

Results

Among 511 patients hospitalized because of syphilis, 98 had concomitant HIV infection (96 males and 2 females). An increase in the number of HIV infections was observed in the group of syphilis-positive patients at a rate of 3.89% per year (Pearson p < 0.001, N = 8). The correlation in the total yearly number of syphilis and HIV positive cases (Pearson p < 0.001, N = 8) was noticed in 2015–2022. The most frequent comorbidities were hepatitis viruses (42.9%), gonorrhoea (16.3%) and depression (13.3%).

Conclusions

In our study we observed a considerable increase in the number of patients diagnosed with the coinfection of syphilis and HIV in the last few years. The above analysis underscores the ongoing public health challenges associated with these diseases.

Keywords: syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus, coinfection, sexually transmitted infections, HBV, HCV, prevention

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syphilis remain significant global public health challenges as sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Their transmission not only poses substantial individual health risks but also contributes significantly to the overall burden of infectious diseases.

The magnitude of the syphilis issue is substantial. In 2022, the World Health Organization estimated that there were 8 million cases of syphilis among adults aged 15–49 globally [1]. Regarding HIV, in the European Region, an estimated 3.1 million individuals were living with HIV in 2023, of which 62% were receiving treatment [2]. Recent years have witnessed a notable increase in the global incidence of coinfections involving HIV and syphilis. Syphilis not only amplifies HIV transmission but also accelerates the progression of HIV infection. Moreover, resolution of ulcers typically takes longer in coinfected patients compared to those with syphilis alone [3]. Besides these complications, shared risk factors and transmission routes contribute to a higher occurrence of other STIs such as viral hepatitis, chlamydiosis, or gonorrhoea in patients with HIV and syphilis [4–7].

An important consideration is the asymptomatic clinical presentation of numerous STIs, which may underlie escalating transmission rates. According to the latest estimates by the World Health Organization (WHO), a substantial number of individuals infected with syphilis either remain asymptomatic or fail to manifest any clinical symptoms, potentially evading detection by healthcare practitioners. Left untreated, syphilis can persist for years, culminating in severe and debilitating health complications. Given the significant scope of this issue, continual efforts to enhance public awareness regarding sexually transmitted diseases are crucial [3, 7, 8].

Due to the significant increase in the number of HIV and syphilis coinfections, effective prevention methods are essential to reduce STI transmission and mitigate health consequences. Additionally, strategies to increase the detection of asymptomatic infections in the future are warranted.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to analyse a cohort of patients hospitalized between 2015 and 2022 at the Department of Dermatology, Paediatric Dermatology, and Dermatological Oncology at the Medical University of Lodz, Poland, due to syphilis with a concurrent HIV infection. This study aims to highlight recent trends in the epidemiology of these sexually transmitted diseases and to identify correlations between these two prevalent STIs.

Material and methods

A retrospective study was conducted at the Department of Dermatology, Paediatric Dermatology, and Dermatological Oncology at the Medical University of Lodz, Poland. This study included 98 adult patients with reported HIV coinfection, selected from a cohort of 511 patients admitted between January 2015 and December 2022 due to syphilis. Patients were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10). Syphilis diagnosis relied on clinical features of the disease and two positive serologic tests: a nontreponemal test (such as RPR or VDRL) and a treponemal test (such as TPHA, FTA, or FTA-Abs). HIV diagnosis was established through serological or nucleic acid tests (NAT) and a CD4+ T-cell count.

Comprehensive retrospective reviews of medical histories and departmental databases were conducted to collect detailed standardized information. Data on the stage of syphilis (early, late, unspecified) and clinical presentation of both syphilis and HIV were extracted from patient charts. Information on HIV treatment was presented as a list of active substances taken by patients at the time of data collection, structured as a treatment regimen (e.g., NRTI + NtRTI + InSTI). Syphilis treatment regimens were also documented. Demographic data including gender, age, length of hospitalization, and comorbidities categorized into groups were collected.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, categorical data were presented as total numbers and percentages of the total number of patients studied. Pearson’s χ2 test was utilized to examine relationships among variables, while multiple regression was employed to identify correlations between scale variables and various normally distributed and/or dichotomous independent/predictor variables. Given the retrospective design, no prior sample size calculation was conducted. Instead, all eligible patient data were utilized for the analysis. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0, released by IBM Corp in 2022, based in Armonk, NY.

The study was conducted in alignment with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Lodz.

Results

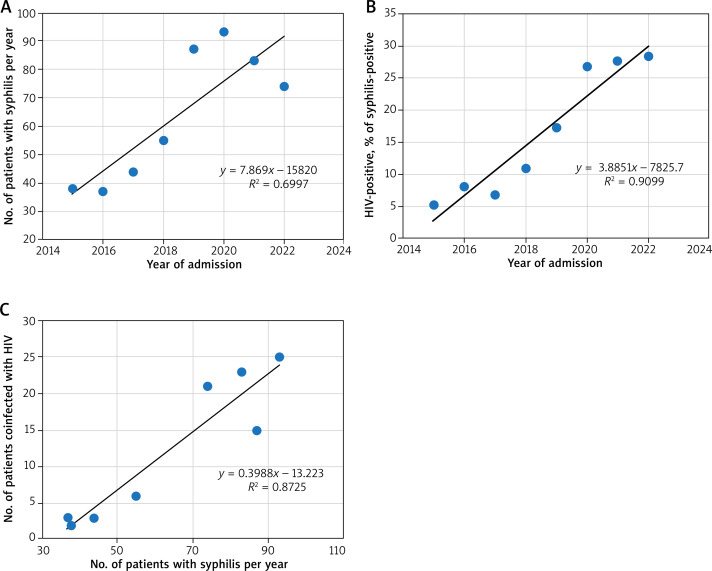

Between 2015 and 2022, the study included 511 cases of syphilis-positive patients upon admission. The number of syphilis cases per year is shown in Figure 1 A. The data indicate that there is a steady increase in the number of cases at 7.87 cases per year (Pearson r = 0.836, R2 = 0.700, p = 0.01, n = 8).

Figure 1.

Numbers of syphilis and HIV positive cases in 2015–2022, including their correlation over time. A – Numbers of syphilis positive cases over the years. The y-axis and the data labels represent the total number of patients with syphilis. The trend line emphasizes the increase in the number of cases per year. B – The percentage of HIV-positive cases among patients coinfected with syphilis over the years. The y-axis and the data labels represent the percentage of patients with HIV. The trend line emphasizes the increase in percent of cases per year. C – Correlation between total yearly number of syphilis and HIV-positive cases. The y-axis represents the total number of patients with HIV in relation to the total number of syphilis patients. The trend line emphasizes positive

Among these patients, the percentage of HIV-positive ones (Figure 1 B) has been increasing statistically significantly as well, at a rate of 3.89% per year (Pearson r = 0.954, R2 = 0.910, p < 0.001, n = 8).

Separately, there is a correlation between the total yearly number of syphilis cases and the total yearly number of HIV cases among them (Pearson r = 0.934, R2 = 0.872, p < 0.001, n = 8) (Figure 1 C). As such, 98 of all admitted syphilis patients were later determined to be infected with HIV.

In our study, a considerable number of patients were males aged from 18 to 70 years old. The youngest patient was 18 years old, and the oldest one was 70 years old. 82.7% of hospitalizations were 1-day stays, primarily due to the mandatory inpatient drug administration, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and hospital stay data of patients diagnosed with HIV and syphilis coinfection

| Characteristics | All patients n = 98 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex male/female, n (%) | 96 (97.9%)/2 (2.1%) | ||

| Age [years] | Median (IQR) | 34.5 (30–42) | |

| Age category | ≤ 29 | 23 (23.5%) | SD ±0.82 |

| 30–39 | 46 (46.9%) | ||

| 40–49 | 24 (24.6%) | ||

| ≥ 50 | 5 (5.1%) | ||

| Time spent in hospital, mean ± SD [days] | 1.57 ±2.1 | ||

According to ICD-10, individuals in the study are more likely to have “Other and unspecified syphilis” – A53 (46.9%) than “Early syphilis” – A51 (31.6%) and “Late syphilis” – A52 (21.4%). 51.1% of syphilis cases were symptomatic. The most common presenting symptom was macular rash (20.4%), followed by ulcerations (17.3%), considering both typical and atypical localizations, and papular skin lesions (11.2%). Uncommon presentations include lymphadenopathy, syphilitic alopecia, erythematous and exfoliative skin lesions. The total distribution of symptoms is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Syphilis cases stratified by symptoms (percent). Percentage of episodes of syphilis with symptomatic or asymptomatic course of the disease

In HIV episodes (Figure 3), a smaller percentage of patients (44.9% vs. 55.1%) developed symptoms of infection compared to syphilis. The most common ones were lymphadenopathy, fever and weight loss. Noteworthy, there was an incidence of other opportunistic infections such as candidiasis (10.2%), which would indicate the assignment of these patients to HIV Clinical Classification [9] category B, besides that tuberculosis (2.0%) (needs confirmation of CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of less than 200 cells/μl) and Kaposi sarcoma (1.0%) correspond to category C (AIDS-defining conditions).

Figure 3.

HIV cases stratified by symptoms (percent). Percentage of episodes of HIV with symptomatic or asymptomatic course of the disease

Multiple regression was conducted to investigate the best prediction of other study group comorbidities. The predictive value of comorbid diseases based on hepatic infections (42.9% of total cases), psychiatric diseases (17.3% of total) and skin disorders (17.3% of total) was statistically significant, F = 36.12, p < 0.001. The β coefficients are presented in Table 2. It should be noted that the presence of the above-mentioned disorders can significantly predict other comorbidities. The adjusted R² value was 0.521. This indicates that 52% of the variance in comorbidities was explained by the model. According to the Cohen model, as reviewed in [10], this is a large effect. Among hepatic virus infections HCV predominated (29.6%) followed by HBV (13.3%) and HAV (8.2%). Comorbid diseases of the STI group (28.6%) were composed of gonorrhoea (16.3%), chlamydiosis (11.2%) and condylomata acuminata (12.2%). Depression (13.3%) was the most frequently observed in the group of psychiatric diseases. Digestive (21.4%) and respiratory disorders (8.2%) were also presented.

Table 2.

Simultaneous multiple regression analysis Summary for hepatic infections, psychiatric diseases and skin disorders predicting comorbidities (N = 98)

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic infections | 1.14 | 0.21 | 0.39 | 5.47 | < 0.001 |

| Psychiatric diseases | 1.21 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 5.39 | < 0.001 |

| Skin disorders | 1.29 | 0.23 | 0.40 | 5.57 | < 0.001 |

| Constant | 0.680 | 0.141 |

Note. R2 = 0.732, F = 36.12, p ≤ 0.001

All patients were treated according to Polish guidelines for syphilis treatment. A standard injection of benzathine penicillin was used in 91.8% of the syphilis-positive patients, while 7.1% received an injection of procaine penicillin and 1.0% received a combination of benzathine and crystal penicillin. HIV treatment included in most cases nucleoside and nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI + NtRTI) with integrase strand transfer inhibitors (InSTI) – 54.1%. Other combinations consist of 2NRTI + InSTI – 16.3%, NRTI + NtRTI + NNRTI (non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor) – 15.3%. Less common regimens additionally included protease inhibitors (PI) and CYP 450 inhibitors.

Discussion

According to the most recent estimate by WHO, HIV, viral hepatitis, and STIs are responsible for more than 2.3 million people dying per year, which make them one of the major public health threats worldwide [11]. Even though syphilis can be easily diagnosed with rapid lateral flow antibody tests and effectively treated with a single dose of long-acting penicillin, its prevalence and incidence are still growing. In our study a steady increase in the number of cases at 7.87 cases per year was also observed, which confirms the global trend [12]. The growing problem in the diagnosis of syphilis is atypical presentations, especially in the secondary stage of the disease, which can mislead clinicians and prolong the time before the statement of a proper diagnosis. A recent study found that 25% of the patients diagnosed with syphilis in the last 10 years had atypical clinical manifestations [13]. They can resemble other dermatological disorders such as psoriasis, lupus erythematosus, granuloma annulare and others [13, 14]. The diagnosis of syphilis in people living with HIV (PLWH) is often complicated by serofast states, where antibody titres remain high after treatment, and the prozone effect, which can lead to inaccurate test results [15, 16]. Recognizing these diagnostic challenges is critical in managing syphilis among immuno-compromised patients and ensuring timely and accurate care.

The rates of HIV and syphilis coinfection globally have been on the rise in recent years. It was reported that from 2009 to 2018, the number of cases in Europe had doubled [3]. The results of our study support these reports and show further increase at a rate of 3.89% per year in the number of patients with HIV and syphilis coinfection. Many factors are described to play an important role as a cause of this phenomenon. In the past, HIV infection was believed to be fatal, but thanks to introducing highly effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) it became less frightening for patients, which led to decline in previously adopted safer sex behaviours including unprotected sex [17–19]. Additionally, the growing use of the Internet to find sexual partners is associated with high-risk sexual behaviours such as multiple sex partners and substance abuse during sex [20]. It was also reported that patients with syphilis are more susceptible to contract HIV [4].

Because of similar risk factors, other STIs like viral hepatitis, chlamydiosis or gonorrhoea also tend to accompany syphilis and HIV infection. In our research, over 40% of patients were coinfected with one of the hepatic viruses, which makes it the most common concomitant disease. The WHO report describes that there are 2.7 million people coinfected with HIV and hepatitis B virus and 2.3 million people coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus [6]. However, our results show that infection with HCV was more common than with HBV. Patients should be aware that HIV coinfection seems to promote the progression of liver diseases in patients infected with hepatic viruses, which leads to an increased risk of cirrhosis and possibly hepatocellular cancer [21]. Furthermore, liver diseases are a major cause of morbidity and mortality among those living with both HIV and viral hepatitis. To reduce this risk, testing for hepatic viruses should be considered in each patient with HIV and syphilis coinfection. If screening tests for hepatic viruses are positive, patients should be immediately provided with appropriate and effective treatment [6]. Also, in our study, 16.3% of patients had gonorrhoea, 12.2% – condylomata acuminata and 11.2% – chlamydiosis. This might relate to the fact that the main group of our patients were men, most probably men who have sex with men (MSM). In the literature, it is reported that MSM, especially with HIV coinfection, are at greater risk of developing chlamydiosis, gonorrhoea and other STIs [22, 23]. Recently, the incidence of monkeypox infections has been increasing worldwide. The sexually transmitted infections with this virus have been observed, so it is important to remember that this disease can be acquired concomitantly with syphilis and HIV [24, 25].

Also, it is worth emphasizing that psychiatric disorders were observed in 17.3% of our patients, which might be a result of stigmatization connected with acquiring sexually transmitted diseases. It is still a huge social problem, which demands further actions to provide psychosocial support for affected patients and to improve common knowledge about STIs. Stigmatization could also reduce the likelihood of being screened for STIs, as well as possibility of seeking health care, so it is crucial that everyone can access services in an inclusive, non-discriminatory, and supportive environment [26, 27].

In our research, almost 98% of patients were men, which might relate to the fact that men who have sex with men are a key population for HIV infection and syphilis [8, 11, 28]. According to the literature, in the MSM group, syphilis surveillance showed an increasing HIV and syphilis coinfection rate, ranging from 30% to 60% depending on the geographic [4]. Because of the increasing number of syphilis cases in HIV-positive MSM there is a need for syphilis screening in HIV-positive patients to prevent further transmission of HIV and syphilis among uninfected MSM. According to the recommendations of the WHO information note, which aimed to generalize the implementation of dual HIV and syphilis point-of-care tests, screening tests should also be implied in other groups of patients with high-prevalence [29]. What is concerning in our study is that nearly 50% of patients did not exhibit any symptoms of syphilis, and over 50% of patients did not show any symptoms of HIV infection. In most cases, the coinfection with syphilis or HIV was discovered incidentally during hospitalization for unrelated reasons. Additionally, many asymptomatic patients who engaged in high-risk sexual intercourse sought one-day hospitalization to rule out potential STIs. If screening tests yielded positive results, these patients were included in our research. These findings underscore the importance of expanding screening tests to include patients with lower prevalence to detect potential asymptomatic disease courses.

In 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, our study identified the highest number of cases for both syphilis and HIV. This contrasts with recent international studies, which have largely reported a decline in STI diagnoses [30–32]. The observed trends may be attributed to the unique role of our Dermatology Department during the pandemic as it remained the sole facility admitting non-COVID-19-infected patients, including those requiring STI diagnostics, in contrast to other hospitals.

While our study offers valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. Firstly, the study cohort was relatively small and composed exclusively of adult patients. As a retrospective study using existing patient records, no prior sample size calculation was feasible, and the findings should therefore be interpreted with caution regarding statistical power. Secondly, the predominance of male patients limits the generalizability of our findings to the female population affected by HIV and syphilis. Thirdly, data collection was confined to a single centre in Poland, suggesting the need for further cross-sectional studies across diverse urban settings to enhance our understanding of HIV and syphilis coinfection in Poland.

In summary, sexually transmitted diseases remain a significant public health concern globally. Our study delineates the characteristics of a specific population affected by two critical STIs: syphilis and HIV infection. Over recent years, we have witnessed a notable surge in the number of patients diagnosed with coinfection of syphilis and HIV, particularly among men, predominantly among men who have sex with men (MSM). The most prevalent comorbidities among syphilis-infected and HIV-positive patients include viral hepatitis infections, psychiatric disorders, and other STIs such as gonorrhoea or chlamydia. This analysis underscores the persistent public health challenges associated with these conditions and emphasizes the imperative of enhancing population awareness and preventive measures.

Funding Statement

Funding This research was supported by statutory activities funds of the Medical University of Lodz no. 503/5-064- 04/503-01.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Lodz (approval number RNN/25/24KE).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . (2024) Syphilis. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/syphilis [accessed on 6 November 2024].

- 2.World Health Organization . (2024) Global HIV Programme. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/hiv/strategic-information/hiv-data-and-statistics [accessed on 6 November 2024].

- 3.Ren M, Dashwood T, Walmsley S. The intersection of HIV and syphilis: update on the key considerations in testing and management. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021; 18: 280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu MY, Gong HZ, Hu KR, et al. Effect of syphilis infection on HIV acquisition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect 2021; 97: 525-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mimiaga MJ, Helms DJ, Reisner SL, et al. Gonococcal, chlamydia, and syphilis infection positivity among MSM attending a large primary care clinic, Boston, 2003 to 2004. Sex Transm Dis 2009; 36: 507-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . (2017) Global hepatitis report 2017. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/255016/9789241565455-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [accessed on 26 April 2024].

- 7.Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Korenromp E, et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull World Health Organ 2019; 97: 548-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance 2018. Atlanta U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. JAMA 1993; 269: 729-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IBM SPSS for Introductory Statistics: Use and Interpretation Fifth Edition, George A. Morgan Colorado State University Nancy L. Leech University of Colorado Denver Gene W. Gloeckner Karen C. Barrett Colorado State University, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . (2021) Global progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections, 2021. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/341412/9789240027077-eng.pdf [accessed on 26 April 2024].

- 12.Chen T, Wan B, Wang M, et al. Evaluating the global, regional, and national impact of syphilis: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. Sci Rep 2023; 13: 11386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciccarese G, Facciorusso A, Mastrolonardo M, et al. Atypical manifestations of syphilis: a 10-year retrospective study. J Clin Med 2024; 13: 1603.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramoni S, Genovese G, Pastena A, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of 244 men with primary syphilis: a 5-year single-centre retrospective study. Sex Transm Infect 2021; 97: 479-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchese V, Tiecco G, Storti S, et al. Syphilis infections, reinfections and serological response in a large italian sexually transmitted disease centre: a monocentric retrospective study. J Clin Med 2022; 11: 7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiecco G, Degli Antoni M, Storti S, et al. A 2021 update on syphilis: taking stock from pathogenesis to vaccines. Pathogens 2021; 10: 1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clement ME, Hicks CB. Syphilis on the rise: what went wrong? JAMA 2016; 315: 2281-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Traeger MW, Cornelisse VJ, Asselin J, et al. Association of HIV preexposure prophylaxis with incidence of sexually transmitted infections among individuals at high risk of HIV infection. JAMA 2019; 321: 1380-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuddenham S, Shah M, Ghanem KG. Syphilis and HIV: is HAART at the heart of this epidemic? Sex Transm Infect 2017; 93: 311-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosser BR, Oakes JM, Horvath KJ, et al. HIV sexual risk behavior by men who use the Internet to seek sex with men: results of the Men’s INTernet Sex Study-II (MINTS-II). AIDS Behav 2009; 13: 488-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu J, Liu K, Luo J. HIV-HBV and HIV-HCV coinfection and liver cancer development. Cancer Treat Res 2019; 177: 231-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansen K, Steffen G, Potthoff A, et al. STI in times of PrEP: high prevalence of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and mycoplasma at different anatomic sites in men who have sex with men in Germany. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribeiro S, de Sousa D, Medina D, et al. Prevalence of gonorrhea and chlamydia in a community clinic for men who have sex with men in Lisbon, Portugal. Int J STD AIDS 2019; 30: 951-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciccarese G, Di Biagio A, Bruzzone B, et al. Monkeypox outbreak in Genoa, Italy: clinical, laboratory, histopathologic features, management, and outcome of the infected patients. J Med Virol 2023; 95: e28560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maldonado-Barrueco A, Sanz-González C, Gutiérrez-Arroyo A, et al. Sexually transmitted infections and clinical features in monkeypox (mpox) patients in Madrid, Spain. Travel Med Infect Dis 2023; 52: 102544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunningham SD, Kerrigan DL, Jennings JM, Ellen JM. Relationships between perceived STD-related stigma, STD-related shame and STD screening among a household sample of adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2009; 41: 225-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organisation . (2022) Global health sector strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022-2030. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/360348/9789240053779-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [accessed on 26 April 2024].

- 28.Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 845-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Information note: World Health Organization . (2017). WHO information note on the use of dual HIV/Syphilis Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDT). World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/252849 [accessed on 26 April 2024]. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berzkalns A, Thibault CS, Barbee LA, et al. Decreases in reported sexually transmitted infections during the time of COVID-19 in King County, WA: decreased transmission or screening? Sex Transm Dis 2021; 48 (8S): S44-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sentís A, Prats-Uribe A, López-Corbeto E, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sexually transmitted infections surveillance data: incidence drop or artefact? BMC Public Health 2021; 21: 1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chow EPF, Ong JJ, Denham I, Fairley CK. HIV testing and diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Melbourne, Australia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2021; 86: e114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]