Abstract

ABSTRACT

Objective

To develop and validate LUPIN, a self-administered, patient-centred questionnaire codesigned by patients and lupus specialists to assess disease activity and patient-reported outcomes in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Methods

LUPIN and the SF-36 questionnaires were distributed across 34 centres in both metropolitan France and overseas territories. Patients completed the questionnaire prior to their consultations. Physicians, blinded to patients’ responses, assessed disease activity using SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) and Physician Global Assessment (PhGA). Correlations and discordances between patient and physician assessments were analysed.

Results

Among 444 participants (85% women, mean age 45 years), the most common manifestations included joint (86%) and skin (72%) involvement; 35% had a history of lupus nephritis. While correlations between LUPIN scores and SLEDAI/PhGA were statistically significant but modest (r<0.39), stronger associations were observed with SF-36 domains for fatigue (r=0.65), pain (r=0.65), and physical function (r=0.69). In patients with active SLE (SLEDAI≥4; n=153), the correlation between LUPIN and clinical SLEDAI improved (r=0.53, p<0.0001). Discordances were primarily driven by patient-reported fatigue and pain, unrelated to suspected mechanical or central pain syndromes.

Conclusion

LUPIN effectively captures symptom domains that are often under-represented in conventional clinical indices and reflects the lived burden of disease in SLE. It offers a practical, scalable tool to support patient engagement, shared decision-making and individualised disease monitoring. A longitudinal digital study is underway to further assess its value in tracking disease fluctuations over time.

Keywords: Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic; Patient Reported Outcome Measures; Outcome Assessment, Health Care; Health-Related Quality Of Life

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), traditional physician-based indices like SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 often fail to capture patient-prioritised symptoms such as fatigue and pain, leading to frequent discordance between clinical assessments and patient experiences.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study introduces and validates LUPIN, a self-administered, patient-centred questionnaire codesigned with patients and clinicians, which reliably captures patient-reported outcomes—particularly symptoms under-represented in standard tools as well as some degree of disease activity.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

LUPIN may represent a scalable tool for integrating patient perspectives into routine SLE care and research, with potential to enhance shared decision-making, personalise disease monitoring and guide future digital health innovations.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease with a highly heterogeneous, relapsing–remitting course that can affect multiple organ systems. The treatment relies on immunosuppressive drugs to achieve clinical remission of the disease.1 However, even during periods of apparent clinical stability, patients often experience persistent symptoms such as fatigue, pain and cognitive dysfunction, which significantly impair quality of life and functional status.2 3

Clinical assessment of disease activity in SLE commonly relies on physician-based tools like the SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) and the Physician Global Assessment (PhGA), which primarily emphasise clinical signs and laboratory markers.4 However, these indices frequently fail to capture the full scope of patient-experienced disease burden.4,6 In particular, symptoms like fatigue and emotional distress often remain unrecognised or are underweighted in clinical decision-making.7 8 Moreover, fatigue can influence physician perception of disease severity without necessarily reflecting active inflammation, introducing bias into global assessments.4

Several patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments have been developed to address these limitations. Tools such as LupusQoL-FR and the Quick-SLAQ assess quality of life or perceived disease activity but are not integrated into standard clinical workflows and do not fully capture the domains patients identify as most impactful.9,12 Recently, digital health tools and biosensor platforms have shown promise for remote monitoring of disease activity and flare prediction.13 However, none of the available instruments has been codeveloped with patients to provide a validated, easy-to-use tool for routine assessment of both disease activity and patient-prioritised symptoms.

To bridge this gap, we developed LUPIN, a self-administered questionnaire codesigned by patients and lupus experts under the leadership of the French national lupus patient association (AFL+). Grounded in the principles of participatory research and the Montreal Model of healthcare democracy, LUPIN emphasises shared decision-making and patient empowerment. The tool captures key domains prioritised by patients—including fatigue, pain, cognitive fog and physical function—using simple formats such as visual analogue scales (VAS) and body symptom mapping. LUPIN is designed as a complementary tool to existing physician-based indices (eg, SLEDAI-2K, PhGA) rather than a replacement. Its primary role is to integrate patient perspectives into disease assessment, supporting shared decision-making, symptom monitoring and the identification of patient–physician discordance.

This study aimed to evaluate the construct validity and clinical relevance of LUPIN in a large, multicentre, real-world cohort of patients with SLE. Specifically, we compared LUPIN scores with traditional clinical indices (SLEDAI-2K and PhGA) and validated PRO measures (SF-36) and examined patient–physician discordance in perceived disease activity.

Patients and methods

Tool development

Patient representatives from the French national lupus association (AFL+) and lupus experts, including internists, rheumatologists and a psychologist collaboratively developed LUPIN, a self-administered questionnaire designed to assess perceived disease activity in SLE.

The development of LUPIN was based on current best practices in patient-centred outcome measurement and grounded in a participatory health research approach. This model emphasises the coconstruction of tools by healthcare professionals and patients, recognising their complementary expertise: clinicians contribute medical knowledge, while patients provide invaluable insight into the lived experience of illness. The process was guided by the principles of the Montreal Model for Healthcare Democracy,14 which promotes shared decision-making and the active involvement of patients in healthcare innovation. This framework ensures that instruments like LUPIN are not only methodologically robust but also aligned with patient priorities and real-world concerns. The questionnaire’s content was refined through iterative collaboration between patients and clinicians, focusing on domains consistently identified as both clinically relevant and personally meaningful such as fatigue, joint pain, mental fog and functional limitations. The present study dataset was used exclusively to evaluate LUPIN’s performance in a large, real-world SLE cohort as part of its initial validation. While this constitutes a robust first validation, further confirmation in an independent sample is important and is planned in a prospective, multicentre study.

This tool includes multiple domains of patient-perceived SLE activity (figure 1 and online supplemental figure S3) and the SF-36 quality-of-life questionnaire. The SF-36 was administered concurrently for validation purposes only and is not part of the routine LUPIN tool. It specifically features VAS for pain, fatigue and mental fog. Additional components include questions on physical limitations and a body diagram allowing patients to indicate areas of pain, specifically designed to differentiate joint-related pain from pain in other body areas (eg, muscles, skin or organs). For external validation, the SLEDAI-2K and the PhGA were selected as clinical reference measures. The clinical SLEDAI is defined as the SLEDAI score excluding laboratory parameters (eg, complement levels, anti-dsDNA antibodies), allowing a focus on clinical signs and symptoms.

Figure 1. LUPIN questionnaire for patients.

Patients

The study followed a one-time, cross-sectional, anonymous and blinded design. Patients with SLE as diagnosed by their referent lupus specialist were invited to participate during a regular patient visit. Patients completed the questionnaire during a day hospital visit prior their medical consultation and submitted it to their physician. Physicians, blinded to the LUPIN score and prior self-reported data (but not to prior clinical history), independently assessed SLE disease activity using the PhGA and SLEDAI-2K and recorded clinical characteristics.

The questionnaire was distributed across 34 centres in mainland France and its overseas territories (Reunion Island, Mayotte, Wallis & Futuna, Martinique and Guadeloupe) where lupus prevalence is notably higher, partly due to the higher proportion of individuals of African, Afro-Caribbean, Asian or Pacific Islander descent, populations known to be at increased risk for SLE.15 16

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was designed as a non-interventional study, with no modification of the usual patient management and no randomisation. All participants received written information about the study and provided their non-opposition for the anonymous use of their clinical and paraclinical data for research purposes, in line with French regulations for observational studies. In this study, questionnaire data were collected as anonymous from the outset (ie, no identifiers were ever recorded), which differs from anonymised data where identifying information is initially collected and then removed through a reversible process. As such, the EU General Data Protection Regulation (in force since 25 May 2018) did not apply, since anonymous data are not considered personal data and their use has no impact on individuals’ privacy. The protocol received approval from the Independent Ethics Committee of the Faculties of Medicine of the University Hospitals of Strasbourg (reference CE-2022–125, approved on 11 October 2022).

Statistical analysis

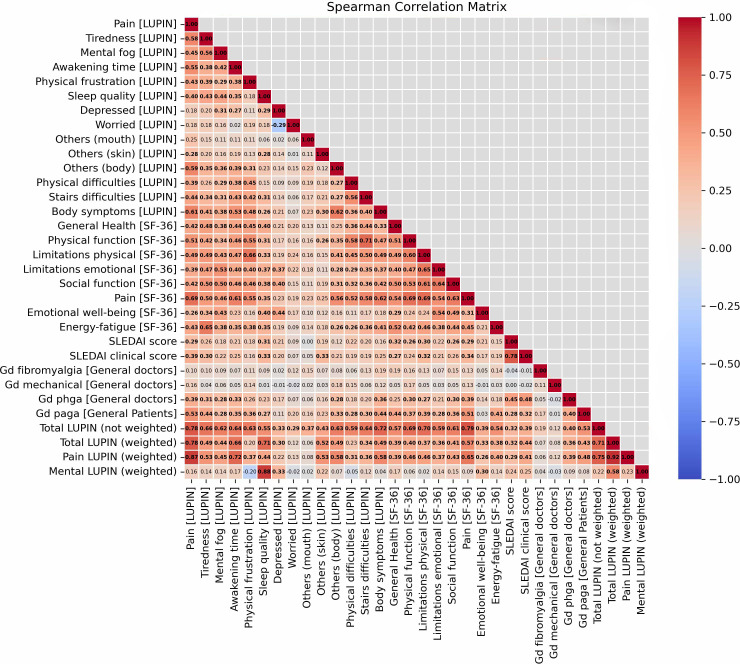

Quantitative variables are given using mean±SD in case of normal distribution or using median (IQR 25–75) otherwise. Correlations between patient responses across individual LUPIN components, SF-36 domains and physician assessments (SLEDAI-2K and PhGA) were analysed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r), which measures the strength and direction of association between two variables. Correlation coefficients between 0.2 and 0.39 were considered as weak, 0.40 and 0.59 as moderate, 0.60 and 0.79 as strong and ≥0.80 as very strong.

To further explore differences between patient and physician perspectives, subgroup comparisons were conducted using Student’s t-test. This test compares the average scores between groups, such as concordant and discordant patient–physician pairs, to determine whether observed differences are likely due to chance or reflect meaningful variation.

P-values for each correlation and t-test were adjusted for multiple testing using the Bonferroni correction.

Regarding missing data, no imputation or data replacement was performed. All statistical analyses were conducted on complete case datasets only, as illustrated in the study flowchart (figure 2), where 444 returned questionnaires were complete for the primary analyses. For the correlation matrices (figures2 3), only patients with complete data for all included variables were analysed (n=243 for full cohort, n=153 for active subgroup). For Student’s t-test between groups (figure 4 and online supplemental figure S3), the full cohort (n=243) was used.

Figure 2. Study flowchart. The flowchart shows patient inclusion, returned questionnaires and datasets used for complete-case analyses. PaGA, Patient Global Assessment; PhGA, Physician Global Assessment; SLEDAI-2K, SLE Disease Activity Index 2000.

Figure 3. Correlation matrix between components of LUPIN, clinical activity and patient-reported outcomes. Spearman correlation matrix showing relationships between LUPIN components, SF-36 domains and physician assessments, with statistically significant (adjusted p value<0.001) correlations (r values) in bold. The analysis was conducted on the 243 patients with complete data for all variables included in the matrix (n=243). SLEDAI-2K, SLE Disease Activity Index 2000.

Figure 4. Correlation matrix between component of LUPIN, clinical activity and patient-reported outcomes in active SLE. Spearman correlation matrix of 153 active patients (SLEDAI≥4) showing relationships between LUPIN components, SF-36 domains, and physician assessments, with statistically significant (adjusted p-value<0.001) correlations (r values) in bold. SLEDAI-2K, SLE Disease Activity Index 2000.

Questionnaire

To investigate the relationship between LUPIN global score and the clinical SLEDAI score (primary objective), we applied a two-step analytical approach. First, each question in the LUPIN questionnaire (figure 1) was assigned a specific scoring method: slider-type questions (eg, pain, fatigue, mental fog) were scored from 0 to 100; ordinal questions were scored from 0 up to the number of response options; binary questions received a score of 0 or 1; morning unlocking time was scored between 0 and 60 min; and body symptom questions were scored based on the number of areas checked. Patient Global Assessment and PhGA (PaGA and PhGA) were initially rated on a 0–3 visual scale, where 0 indicates no disease activity and 3 indicates maximal activity, then converted to a 0–100 scale for analysis. Qualitative items, such as mental state and other manifestations, were decomposed into multiple binary variables (eg, ‘worried’, ‘depressed’, ‘calm’). All resulting scores were then normalised between 0 and 1 to ensure equal weighting across variables (online supplemental table S1). In a second step, we used linear regression to explore how the different domains of LUPIN could be weighted in order that LUPIN global score better approximates the clinical SLEDAI. The model aimed to determine the set of weights (Lw) and intercept (Lb) that best fit the observed SLEDAI values based on normalised LUPIN variables (Lv), using the formula: Lw₁ × Lv₁ + … + Lwₙ × Lvₙ + Lb = Clinical SLEDAI. This analysis was conducted solely as an exploratory construct-validation exercise, not to modify the tool’s patient-centred purpose. The regression-derived weights were, therefore, considered hypothesis-generating, with the sole objective of examining whether differential item weighting could improve approximation to the clinical SLEDAI. The model was fitted to the full dataset without division into training and validation samples, and no cross-validation or bootstrapping was applied, which increases the risk of overfitting. External validation is planned in the ongoing prospective study. The intent was to identify which patient-reported domains most closely tracked with physician indices, rather than to replace the unique perspective LUPIN provides. This approach yielded a set of variable-specific weights (online supplemental figure S1), highlighting that certain items (such as pain, morning stiffness duration and sleep quality) had stronger contributions to the SLEDAI score, while others showed weaker or even negative associations. In parallel, we also explored two composite LUPIN scores—‘Pain’ and ‘Mental’—aggregating selected questionnaire items related to physical and mental symptom domains, respectively.

To evaluate the internal consistency of the questionnaire subscales, Cronbach’s alpha (α) was calculated. Cronbach’s α is a standard psychometric statistic17 used to assess the extent to which a group of items measures a common underlying construct. α values range from 0 (no internal consistency) to 1 (perfect internal consistency), with values above 0.70 generally considered acceptable for exploratory research. Cronbach’s α was computed using the following formula , where N is the number of items, c is the average inter-item covariance and v is the average item variance. To explore the reliability of LUPIN subdomains, items were grouped a priori into clinically coherent clusters. The following domains were evaluated: Pain–Fatigue–Mental Fog (3 items); Functional/Physical Impairment (4 items: morning stiffness, physical frustration, physical activity, stair difficulties); Mental State/Sleep Quality (2 items); Other Manifestations (3 items: oral ulcers, skin rash, musculoskeletal pain).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 444 patient questionnaires were analysed, from which 76% from mainland France and 24% from overseas territories. The mean age of participants was 45 years (±14.4), and 85% were women. The median SLE duration was 12 years (IQR: 6.0–20.2). Most patients had a history of articular (86%) and cutaneous (72%) involvement, and 35% had experienced lupus nephritis. At the time of evaluation, the median SLEDAI score was 2.0 (IQR: 0.0–4.0) and 29% of patients had an SLEDAI score ≥4. Overall, 69% had positive anti-dsDNA antibodies. Fibromyalgia was reported by the physician in 6.6% of patients, and 20.6% were assessed as having pain with at least a partial mechanical component. Patient feedback collected qualitatively indicated that the LUPIN questionnaire was easy to understand and not burdensome to complete.

Correlation between patient outcomes and physician assessment

Correlations were assessed between PROs and physician-based measures, including the SLEDAI, clinical SLEDAI and PhGA. PhGA correlated moderately but statistically significantly with both the full SLEDAI (r=0.45, p<0.001) and the clinical SLEDAI (r=0.48, p<0.001). As expected, the correlations between LUPIN components and the SLEDAI, clinical SLEDAI or PhGA were statistically significant but weak (0.20<r<0.39, p<0.001 for all). In contrast, strong correlations were observed between several LUPIN components and SF-36 domains, particularly for pain (r=0.65, p<0.001), physical function (r=0.69, p<0.001) and fatigue (r=0.65, p<0.001). The LUPIN global score also showed strong correlations with the SF-36 physical and pain domains (0.69<r<0.79; p<0.001 for all; figure 3).

In the subgroup of patients with active disease (SLEDAI≥4; n=153 patient questionnaires), a stronger and statistically significant correlation was observed between the LUPIN global score and the clinical SLEDAI (r=0.53, p<0.001; figure 4), suggesting improved alignment between PROs and clinical manifestations in more active disease.

An organ-specific approach was also evaluated. Comparison of SLEDAI-2K organ-specific items with their possible LUPIN equivalents revealed no significant correlations (online supplemental figure S2). Conceptually, certain organ manifestations might be expected to align with perceived disease activity (eg, rash, arthritis), whereas others recorded by SLEDAI-2K may remain clinically silent from the patient’s perspective (eg, renal or haematological involvement). The absence of correlation may, in part, reflect substantial differences in the relative frequencies of ‘possible equivalent’ items between SLEDAI-2K and LUPIN (online supplemental table S5), with some items more prevalent in LUPIN and others relatively rare in SLEDAI-2K. These discrepancies likely reduce the ability to detect meaningful linear associations.

Causes of discordance between patients and physicians

To explore physician–patient discordance in the perception of disease activity, patients were classified into three groups based on the SLEDAI and the PaGA of lupus activity. The three groups were defined based on the following hypothesis: concordant active (SLEDAI≥6 and PaGA>33.3), concordant inactive (SLEDAI≤6 and PaGA<33.3) and discordant (SLEDAI≤6 and PaGA>33.3), reflecting agreement or disagreement between physician and patient-reported disease activity. The most notable differences emerged between the concordant inactive and discordant groups, with the latter reporting significantly higher levels of pain and fatigue (Pain 0–100 (Discordant vs Concordant): 44.5±22.5 vs 19.1±20.5, mean difference=25.5, p<0.0001; Fatigue 0–100 (Discordant vs Concordant): 66.8±25.1 vs 40.6±27.9, mean difference=26.2, p<0.0001) (figure 5). These discrepancies were not associated with physician-suspected central pain sensitisation or mechanical pain syndromes or other demographic, psychosocial or clinical variables (online supplemental tables S3 and S4). Sensitivity analyses that excluded patients with suspected fibromyalgia or mechanical pain, or those with a history of neuropsychiatric lupus, slightly reduced the strength of the association for self-reported pain but did not eliminate it (online supplemental table S4). This pattern supports the robustness of the findings and suggests that the instrument is sensitive to variations in symptom profiles, reinforcing the interpretation that subjective symptom burden—particularly pain and fatigue—drives the divergence between patient and physician assessments.

Figure 5. Causes of discordance between patient-perceived and physician-assessed lupus activity. Causes of discordance are shown as mean differences between groups, with positive values indicating higher averages in the discordant group and bold values marking statistically significant differences. PaGA, Patient Global Assessment; SLEDAI-2K, SLE Disease Activity Index 2000.

Notably, when comparing the discordant and concordant active groups for the same outcomes, no statistically significant differences in mean pain or fatigue levels were found, which may be due to the relatively low proportion of clinically active patients in the cohort (only 19% had an SLEDAI score≥6).

Internal consistency of LUPIN questionnaire domains

The Pain–Fatigue–Mental Fog and Functional/Physical domains showed good internal consistency (α=0.769 and 0.714, respectively), suggesting that these clusters reliably capture coherent symptom patterns (figure 6; Online supplemental table S2). In contrast, the Mental State/Sleep domain demonstrated only moderate consistency (α=0.525), likely reflecting the subjectivity and variability of these self-reported experiences. Although the items within this domain (worry, depression, calmness and sleep quality) are conceptually related, they are not necessarily experienced simultaneously by patients with SLE. The Other Manifestations domain had low internal consistency (α=0.354), which is explained by the heterogeneous and episodic nature of these clinical signs. Oral ulcers, cutaneous eruptions and musculoskeletal pain are common in lupus but often occur independently of one another during flares or quiescence, limiting their statistical coherence as a unified scale. The Body Diagram score, which represents a normalised composite measure (0–1) of the number of painful areas reported by patients, was treated as a single-item scale. As such, Cronbach’s α—a metric of internal consistency between multiple items—is not applicable in this case.

Figure 6. Internal consistency of LUPIN questionnaire domains assessed using Cronbach’s α. Cronbach’s α is a standard psychometric statistic used to evaluate the internal consistency of grouped items intended to measure a common underlying construct. Alpha values range from 0 (no consistency) to 1 (perfect consistency).

Discussion

This study presents the development and validation of LUPIN, a patient-centred, self-administered tool designed to assess disease activity and PROs in SLE. Our findings demonstrate that LUPIN effectively captures patient-prioritised symptoms—particularly fatigue, pain and physical limitations—that are often under-represented in conventional clinical indices. Several LUPIN components showed strong correlations with the SF-36 domains, notably physical function, pain and fatigue, underscoring the tool’s capacity to reflect quality-of-life aspects that matter most to patients. This alignment supports LUPIN construct validity as a measure of the lived burden in SLE disease. In addition to LupusQoL-FR, LFA-REAL and Quick-SLAQ, other SLE-specific PROs include LupusPRO18—a comprehensive HRQoL measure; the Lupus Impact Tracker19—a brief tool for assessing disease impact; and the generic EQ-5D,20 21 which has shown good correlation with SLEDAI in studies by Parodis et al.22 23 Unlike these instruments, which primarily focus on HRQoL or health-economic evaluation, LUPIN uniquely combines perceived disease activity and patient-prioritised symptom tracking in a codesigned format suitable for rapid use in clinical encounters. Combining perceived disease activity and PROs within a single instrument addresses the well-recognised gap between physician assessments and patient experiences in SLE. While separate QoL and disease activity tools exist, they are often used in isolation, increasing burden and limiting integration into real-time clinical discussions. LUPIN streamlines this process, providing a holistic, patient-centred view that supports both efficient data capture and shared decision-making in routine care.

As expected from prior studies,24,26 correlations between LUPIN and physician-assessed activity (SLEDAI-2K and PhGA) were statistically significant but modest. This likely reflects the well-documented discordance between objective clinical findings and the subjective patient experience, particularly in patients with low disease activity or in remission. Indeed, our cohort included a high proportion of such patients (median SLEDAI=2; 29% with SLEDAI ≥4), which may have limited the range of correlations between LUPIN and physician-assessed disease activity. This predominance reflects real-world recruitment during routine follow-up visits in tertiary centres, where stable cases are over-represented. This sampling bias is an important limitation of the current cross-sectional design. Another limitation is that accrued organ damage, which may influence PROs independently of current disease activity, was not assessed, as the SLICC/ACR Damage Index was not retrieved in this study. Additionally, we were not able to evaluate the impact of corticosteroids on LUPIN score due to missing data and the need of a large number of observations to statistically address this variable.

To address this, we performed a subgroup analysis among patients with active disease (SLEDAI ≥4), in whom LUPIN scores correlated more strongly with clinical SLEDAI. This suggests that LUPIN may better align with physician assessments when disease activity is objectively higher. However, our findings also highlight that in many patients—particularly those with minimal systemic inflammation—quality of life remains heavily impacted by symptoms that are not captured through laboratory measures or physical examinations. This dissociation reflects observations in related conditions like primary Sjögren’s disease, where subjective symptom burden is often dissociated from systemic disease activity.27

The weak correlations observed with the organ-specific approach (online supplemental figure S2 and table S5) suggest that, despite a sound clinical rationale, patients’ perceptions of disease activity are often more nuanced and less rigidly categorised. Importantly, these perceptions are not necessarily inaccurate; broader, more holistic assessments tend to yield stronger correlations, particularly in patients with active disease.

A key limitation of our regression-based weighting analysis is that it was conducted on the same cohort used for the initial development of LUPIN, without cross-validation or testing in an independent sample. As such, the regression-derived weights should be considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating and may be subjected to overfitting. The primary purpose of this analysis was not to create a definitive scoring algorithm, but rather to examine whether certain patient-reported domains more closely aligned with physician-based indices. This aspect will be evaluated in a future prospective study.

Our analysis of discordant patient–physician assessments further illustrates this issue: patients with low SLEDAI scores but high perceived disease activity (ie, the discordant group) reported significantly higher levels of pain and fatigue than their concordant counterparts. Notably, these symptoms were not attributable to physician-suspected mechanical causes, central sensitisation or a history of neuropsychiatric lupus (the latter remaining rare), reinforcing the notion that the patient experience of SLE extends beyond what is captured by standard clinical evaluations. While treatment decisions are guided mainly by objective disease activity, persistent PRO abnormalities may reveal comorbidities or unmet needs requiring intervention. Using LUPIN alongside physician indices can help capture symptom changes between visits, improve patient engagement and prompt timely clinical reassessment.

To assess the internal consistency of symptom domains in the LUPIN questionnaire, we used Cronbach’s α statistic rather than conducting an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). This choice was guided by two considerations: (i) the questionnaire was purposefully constructed around predefined clinical domains derived from patient interviews and expert consensus; and (ii) certain domains—such as ‘Other manifestations’—intentionally group biologically distinct symptoms that are not expected to systematically co-occur. We acknowledge the moderate-to-low Cronbach’s α observed in some domains, notably ‘Mental State/Sleep’ and ‘Other Manifestations’.” This was expected given the conceptual heterogeneity of these items and the episodic nature of such symptoms. Cronbach’s α was chosen over exploratory factor analysis because the domains were pre-defined through patient–clinician consensus rather than derived statistically. In this context, Cronbach’s α provides a pragmatic means of evaluating the internal coherence of each conceptually grounded subscale, without imposing artificial latent structure across the full item set. While Cronbach’s α has known limitations—including its dependence on scale length and its contested role as an index of dimensionality—it remains a widely accepted and interpretable measure of internal consistency in early psychometric validation. Taken together, these results support the internal consistency of the LUPIN symptom domains and provide a foundation for the refinement of lower-performing clusters in future iterations.

The practical implications of these findings are significant. Tools like LUPIN can provide clinicians with structured insights into symptom domains that might otherwise remain unaddressed. They can also support shared decision-making, longitudinal tracking of disease fluctuations and early detection of worsening symptoms or flares. To that end, we are currently setting up a smartphone-based, prospective study to evaluate LUPIN’s performance in real-time monitoring. In the future longitudinal study, LUPIN will also be tested for its standalone predictive and monitoring value. This approach may enhance detection of subtle disease changes, especially in patients with persistently high symptom burden but minimal clinical activity. In parallel, we are exploring artificial intelligence and machine learning models to better characterise the complex, non-linear relationships between LUPIN responses and traditional disease indices like the SLEDAI-2K. These efforts aim to refine predictive accuracy and further individualise disease monitoring.

In conclusion, LUPIN is a novel, patient-informed instrument that complements conventional clinical measures by capturing key aspects of lived experience of SLE. Its integration into clinical practice and digital health platforms could improve real-world disease management, enhance patient engagement and ultimately support more holistic, personalised care in SLE.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all participating patients and investigators; to the AFL+ patient association for its sponsorship and active involvement; and to the French Network of Reference and Competence Centers for Rare Systemic Autoimmune and Autoinflammatory Diseases for facilitating the study through access to sites and investigators. MS is supported by the Bettencourt-Schueller Foundation, the INSERM (ATIP-Avenir), Ecole de l’INSERM Bettencourt-Schueller, the FOREUM foundation and the Arthritis Pierre Coubertin foundation.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was funded by the French government through the Ministry of Health and Solidarities and the National Health Insurance Fund (Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie, Paris, France), under the 'Fonds National pour la Démocratie Sanitaire—Appel à projets national 2023' grant. Additional financial support was provided by the French national lupus patient association AFL+ (Metz, France).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the independent Ethics Committee of Strasbourg Medical University (reference CE-2022-125, approved 11 October 2022). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Collaborators: Jean-François Viallard (Bordeaux, Médecine Interne, CHU, jean-francois.viallard@chu-bordeaux.fr); Estibaliz Lazaro (Bordeaux, Médecine Interne, CHU, estibaliz.lazaro@chu-bordeaux.fr); Christophe Richez (Bordeaux, Rhumatologie, CHU, christophe.richez@chu-bordeaux.fr); Irène Machelart (Bayonne, Médecine Interne, CH, imachelart@ch-cotebasque.fr); Nadine Magy-Bertrand (Besançon, Médecine Interne, CHU, nadine.magy@univ-fcomte.fr); Audrey Gorse (Chambéry, Médecine Interne, CH, audrey.gorse@ch-metropole-savoie.fr); Gilles Blaison (Colmar, Médecine Interne, CH, gilles.blaison@ch-colmar.fr); Julien Campagne (Metz, Médecine Interne, Hôpital Robert Schuman, julien.campagne@uneos.fr); Benjamin Dervieux (Mulhouse, Médecine Interne, CH, benjamin.dervieux@ghrmsa.fr); Thomas Moulinet (Nancy, Médecine Interne, CHU, t.moulinet@chru-nancy.fr); Roland JAUSSAUD (Nancy, Médecine Interne, CHU, r.jaussaud@chu-nancy.fr); Pascal ROBLOT (Poitiers, Médecine Interne, CHU, pascal.roblot@chu-poitiers.fr); Mathieu Puyade (Poitiers, Médecine Interne, CHU, Mathieu.puyade@chu-poitiers.fr); Amélie Servettaz (Reims, Médecine Interne, CHU, aservettaz@chu-reims.fr); Pauline Orquevaux (Reims, Médecine Interne, CHU, porquevaux@chu-reims.fr); Julie Le Scanff (Villefranche Sur Saône, Médecine Interne, CH, JLeScanff@lhopitalnordouest.fr); Daniel Wendling (Besançon, Rhumatologie, CHU, dwendling@chu-besancon.fr); Marc Andre (Clermont-Ferrand, Médecine Interne, CHU, mandre@chu-clermontferrand.fr); Ludovic Trefond (Clermont-Ferrand, Médecine Interne, CHU, ltrefond@chu-clermontferrand.fr); Perrine Smets (Clermont-Ferrand, Médecine Interne, CHU, psmets@chu-clermontferrand.fr); Nicolas Baillet (Basse-Terre (Guadeloupe), Médecine Interne, CHU, nicolas.baillet@ch-labasseterre.fr); Christophe Deligny (Fort-de-France (Guadeloupe), Médecine Interne, CHU, christophe.deligny@chu-martinique.fr); Xavier Mariette (Kremlin-Bicêtre, Rhumatologie, APHP, xavier.mariette@aphp.fr); Arnaud Hot (Lyon, Médecine Interne, HCL - Edouart Herriot, arnaud.hot@chu-lyon.fr); Clara Baverez (Lyon, Médecine Interne, HCL - Edouart Herriot, clara.baverez@chu-lyon.fr); Emmanuelle David (Lyon, Médecine Interne, HCL - Croix Rousse, emmanuelle.david01@chu-lyon.fr); Laurent Perard (Lyon, Médecine Interne, Hôpital Saint-Joseph, lperard@saintjosephsaintluc.fr); Estelle Jean (Marseille, Médecine Interne, La Timone, Estelle.JEAN@ap-hm.fr); Sarah Permal (Mayotte, Médecine Interne, CH, sarah.permal@gmail.com); Sarah Permal (Wallis et Futuna, Médecine Interne, CH, sarah.permal@gmail.com); Denis Wahl (Nancy, Médecine Vasculaire, CHU, d.wahl@chru-nancy.fr); Christian Agard (Nantes, Médecine Interne, CHU, christian.agard@univ-nantes.fr); François Chasset (Paris, Dermatologie, APHP Tenon, francois.chasset@aphp.fr); Patricia Senet (Paris, Dermatologie, APHP Tenon, patricia.senet@aphp.fr); Baptiste Hervier (Paris, Médecine Interne, APHP Saint-Louis, baptiste.hervier@aphp.fr); Ronan Pasquer (Paris, Hometrix Health, ronan.pasquer@hometrix-health.fr); Mickael Martin (Poitiers, Médecine Interne, CHU, mickael.martin@chu-poitiers.fr); Ludivine Lebourg (Rouen, Médecine Interne, CHU, ludivine.lebourg@chu-rouen.fr); Nicolas Girszyn (Rouen, Médecine Interne, CHU, nicolas.girszyn@chu-rouen.fr); Frédéric Renou (Saint-Denis (Réunion), Médecine Interne, CHU, frederic.renou@chu-reunion.fr); Loic Raffray (Saint-Denis (Réunion), Médecine Interne, CHU, loic.raffray@chu-reunion.fr); Elisabeth Diot (Tours, Médecine Interne, CHU, elisabeth.diot@univ-tours.fr); Cécile Fermont (Valence, Médecine Interne, CH, cecile.fermon@ch-valence.fr); Thierry Martin (Strasbourg, Immunologie Clinique, HUS, thierry.martin@chru-strasbourg.fr) Anne-Sophie Korganow (Strasbourg, Immunologie Clinique, HUS, Anne-sophie.Korganow@chru-strasbourg.fr); Jacques-Eric Gottenberg (Strasbourg, Rhumatologie, HUS, jacques-eric.gottenberg@chru-strasbourg.fr

Data availability free text: Data will be shared upon request. The LUPIN questionnaire is available in supplementary materials and upon request.

Contributor Information

Investigators (n=46):

Jean-François Viallard, Estibaliz Llazaro, Christophe Richez, Irène MACHELART, Nadine Magy-Bertrand, Audrey Gorse, Gilles Blaison, Julien Campagne, Benjamin Dervieux, Thomas Moulinet, Roland Jaussaud, Pascal Roblot, Mathieu Puyade, Amélie Servettaz, Pauline Orquevaux, Julie Le Scanff, Daniel Wendling, Marc Andre, Ludovic Ttrefond, Perrine Smets, Nicolas Baillet, Christophe Deligny, Xavier Mariette, Arnaud Hot, Clara Baverez, Emmanuelle David, Laurent Perard, Estelle Jean, Sarah Permal, Sarah Permal, Denis Wahl, Christian Agard, François Chasset, Patricia Senet, Baptiste Hervier, Ronan Pasquer, Mickael Martin, Ludivine Lebourg, Nicolas Girszyn, Frédéric Renou, Loic Raffray, Elisabeth Diot, Cécile Fermont, Thierry Martin, Anne-Sophie Korganow, and Jacques-Eric Gottenberg

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Scherlinger M, Kolios AGA, Kyttaris VC, et al. Advances in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2025:1–19. doi: 10.1038/s41573-025-01242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mikdashi J, Nived O. Measuring disease activity in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus: the challenges of administrative burden and responsiveness to patient concerns in clinical research. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:183. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0702-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manet C, Aim M-A, Queyrel V, et al. Determinants of social participation in patients living with systemic lupus erythematosus: the Psy-LUP multicentre study. RMD Open. 2025;11:e005661. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2025-005661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mertz P, Piga M, Chessa E, et al. Fatigue is independently associated with disease activity assessed using the Physician Global Assessment but not the SLEDAI in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. RMD Open. 2022;8:e002395. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eudy AM, Reeve BB, Coles T, et al. The use of patient-reported outcome measures to classify type 1 and 2 systemic lupus erythematosus activity. Lupus (Los Angel) 2022;31:697–705. doi: 10.1177/09612033221090885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisetsky DS, Clowse MEB, Criscione-Schreiber LG, et al. A Novel System to Categorize the Symptoms of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019;71:735–41. doi: 10.1002/acr.23794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Touma Z, Costenbader KH, Hoskin B, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and healthcare resource utilization in systemic lupus erythematosus: impact of disease activity. BMC Rheumatol. 2024;8:22. doi: 10.1186/s41927-023-00355-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahieu MA, Ahn GE, Chmiel JS, et al. Fatigue, patient reported outcomes, and objective measurement of physical activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus (Los Angel) 2016;25:1190–9. doi: 10.1177/0961203316631632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devilliers H, Amoura Z, Besancenot J-F, et al. LupusQoL-FR is valid to assess quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:1906–15. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Askanase AD, Daly RP, Okado M, et al. Development and content validity of the Lupus Foundation of America rapid evaluation of activity in lupus (LFA-REALTM): a patient-reported outcome measure for lupus disease activity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17:99. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1151-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ugarte-Gil MF, Gamboa-Cárdenas RV, Pimentel-Quiroz VR, et al. The Lupus Foundation of America Rapid Evaluation of Activity in Lupus Patient-Reported Outcome Predicts Health-Related Quality of Life, Fatigue, and Work Productivity Impairment: Data From the Almenara Lupus Cohort. J Clin Rheumatol. 2025;31:162–5. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000002204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svenungsson E, Gunnarsson I, Illescas-Bäckelin V, et al. Quick Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire (Q-SLAQ): a simplified version of SLAQ for patient-reported disease activity. Lupus Sci Med. 2021;8:e000471. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2020-000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jupe ER, Lushington GH, Purushothaman M, et al. Tracking of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Longitudinally Using Biosensor and Patient-Reported Data: A Report on the Fully Decentralized Mobile Study to Measure and Predict Lupus Disease Activity Using Digital Signals-The OASIS Study. BioTech (Basel) 2023;12:62. doi: 10.3390/biotech12040062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministère De La Santé Et Des Services Sociaux Du Québec Framework for partnership approaches between users, their families and health and social services actors. 2018

- 15.Maningding E, Dall’Era M, Trupin L, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Prevalence and Time to Onset of Manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: The California Lupus Surveillance Project. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020;72:622–9. doi: 10.1002/acr.23887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis MJ, Jawad AS. The effect of ethnicity and genetic ancestry on the epidemiology, clinical features and outcome of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:i67–77. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azizoddin DR, Weinberg S, Gandhi N, et al. Validation of the LupusPRO version 1.8: an update to a disease-specific patient-reported outcome tool for systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus (Los Angel) 2018;27:728–37. doi: 10.1177/0961203317739128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jolly M, Garris CP, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Development and validation of the Lupus Impact Tracker: a patient-completed tool for clinical practice to assess and monitor the impact of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1542–50. doi: 10.1002/acr.22349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang S, Wu B, Zhu L, et al. Construct and Criterion Validity of the Euro Qol-5D in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e98883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aggarwal R, Wilke CT, Pickard AS, et al. Psychometric properties of the EuroQol-5D and Short Form-6D in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1209–16. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parodis I, Lopez Benavides AH, Zickert A, et al. The Impact of Belimumab and Rituximab on Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019;71:811–21. doi: 10.1002/acr.23718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parodis I, Haugli-Stephens T, Dominicus A, et al. Lupus Low Disease Activity State and organ damage in relation to quality of life in systemic lupus erythematosus: a cohort study with up to 11 years of follow-up. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2025;64:639–47. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keae120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elefante E, Tani C, Stagnaro C, et al. Articular involvement, steroid treatment and fibromyalgia are the main determinants of patient-physician discordance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22:241. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-02334-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers JL, Clowse MEB, McKenna K, et al. Patient and Physician Perspectives of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Flare: A Qualitative Study. J Rheumatol. 2024;51:488–94. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.2023-0721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golder V, Ooi JJY, Antony AS, et al. Discordance of patient and physician health status concerns in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus (Los Angel) 2018;27:501–6. doi: 10.1177/0961203317722412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seror R, Baron G, Camus M, et al. Development and preliminary validation of the Sjögren’s Tool for Assessing Response (STAR): a consensual composite score for assessing treatment effect in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:979–89. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-222054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.