Abstract

The characteristic electronic structure of the phosphoryl group in phosphine oxides confers great stability on the P+–O– bond, in part because of back-bonding from O-based lone pairs into the P–C antibonding orbitals. The partial nature of this donation allows the O atom in the phosphoryl unit to exhibit Lewis basicity. This backbonding weakens as the atomic number of the pnictogen increases, which results in a significant enhancement in basicity for the heavier stiboryl congener. Here, we compare the ability of R3PnO (Pn = P, As, Sb) species to bind to main-group Lewis acids. As the steric bulk of the R group increases, R3PO and R3AsO lose this capacity; Dipp3PO and Dipp3AsO (where Dipp = 2,6-diisopropylphenyl) are unable to bind even the very strong Lewis acid B(C6F5)3. In contrast, the enhanced basicity of the stibine oxides allows them to overcome this steric hindrance and form adducts, even in the case of the very hindered Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3.

Introduction

The electronic structure of the phosphoryl bond confers exceptional stability on phosphine oxides, allowing their formation to serve as the thermodynamic driving force in transformations such as the Wittig reaction and Staudinger reduction. The P–O bonding interaction in R3PO molecules has been debated, but a currently well-accepted model invokes a σ bond formed with the p z orbital of the O atom and backbonding from the p x and p y orbitals of the O atom into P–C σ* orbitals. This backbonding strengthens the P–O bond but a significant amount of charge remains concentrated on the O atom, allowing phosphine oxides to serve as Lewis bases. This Lewis basicity has been exploited to form metal–ligand complexes, particularly with hard metal ions such as those of the Ln(III) series. Phosphine oxides also readily interact with main-group Lewis acids and spectroscopic studies confirm that a variety of phosphine oxides form stable adducts with the strong Lewis acid B(C6F5)3. , Indeed, Et3PO serves as the most common reporter base in the widely used Guttman–Beckett assay that is used to measure the strengths of Lewis acids, including B(C6F5)3. − Newer methods continue to be developed, with fluorescent phosphine oxides being used to optically measure Lewis acid strength. It is noteworthy that some phosphines, such as tBu3P, that are too sterically encumbered to coordinate to B(C6F5)3, are able to form stable adducts with this acid once oxidized to the phosphine oxide.

Arsine oxides exhibit greater Lewis basicity than their phosphine oxide congeners, which has been ascribed to the lesser extent of donation from the O-based lone pairs into the As–C σ* orbitals. Although the energies of the O-based lone pairs and As–C σ* orbitals approach each other more closely and the σ*-based orbitals gain a more pnictogen character, the lengthening of the Pn–O bond and the greater diffuseness of the Pn-based orbitals ultimately result in less favorable back-bonding. It was recognized early in the systematic investigation of the chemistry of arsine oxides that this enhanced Lewis basicity could be exploited to form stable complexes with transition metals. The increase in donicity can productively modulate the properties of the resulting species, such as the luminescence of lanthanide complexes. − Similar to Ph3PO, Ph3AsO forms a stable adduct with strong main-group Lewis acids like B(C6F5)3.

We recently reported the synthesis and isolation of the first monomeric stibine oxides, Dipp3SbO and Mes3SbO. ,− Our computational data suggested that stibine oxides would exhibit an even lesser degree of back-bonding from the O-based lone pairs into the Pn–C antibonding orbitals. We observed that this variation was reflected in experimentally determined Bro̷nsted basicities, which vary by well over one million-fold across the series Dipp3PnO (Pn = P, As, Sb). An exploratory reaction between Dipp3SbO and BF3·OEt2 resulted not in simple acid–base adduct formation but rather in an unexpected O2–/2F– exchange and clean formation of Dipp3SbF2. It has been previously reported that reaction of B(C6F5)3 with polymeric (Ph3SbO) n results in disassociation of the stibine oxide units and affords the monomeric adduct Ph3SbO·B(C6F5)3 (Scheme ). We have previously observed that Dipp3SbO was too sterically encumbered to react with a series of unencumbered group 14 Lewis acids but that reactions proceeded readily with Mes3SbO. Here, we demonstrate that the variation in the electronic structure of R3PnO species as the pnictogen increases in atomic number confers an exceptional enhancement in Lewis basicity on the stibine oxides. Although Ph3PnO species form Ph3PnO·B(C6F5)3 adducts for Pn = P, As, and Sb, , we demonstrate here that isolable Mes3PnO·B(C6F5)3 adducts only form for Pn = As and Sb; the steric bulk of the mesityl groups results in an equilibrium mixture of Mes3PO/B(C6F5)3 and Mes3PO·B(C6F5)3. The more hindered Dipp3PO does not show any evidence of interaction with B(C6F5)3, nor does Dipp3AsO. In contrast, Dipp3SbO forms a stable Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3 adduct with no spectroscopic evidence of dissociation or exchange in solution (Scheme ). We study the impact of steric hindrance on R3SbO·B(C6F5)3 adduct formation by comparing R = Dipp, Mes, and 3,5-Me2Ph and additionally computationally investigate the thermodynamics of these reactions and probe the variation in the nature of the B–O bonds across the different adducts.

1. Prior Work Demonstrating That Polymeric Stibine Oxides Can Be Disaggregated with Lewis Acids and the Present Work on the Influence of Steric Bulk on the Reaction of Lewis Acids with Monomeric Pnictine Oxides.

Results and Discussion

Reaction of Mes3SbO with Al(OEt)3 and B(OEt)3

On the basis of our earlier results highlighting the Bro̷nsted basicity of monomeric stibine oxides, we anticipated that they would similarly exhibit an enhanced Lewis basicity, as compared to the lighter congeners. We first explored the reactivity of Mes3SbO with Al(OEt)3, given the established reactivity of phosphine oxides with Al(OR)3 compounds, where R is an alkyl or silyl group. − As expected, combination of these species readily afforded the adduct Mes3SbO·Al(OEt)3 as an analytically pure solid (Scheme ). Subtle changes occur in the 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts of resonances from the mesityl rings, as compared to free Mes3SbO, and the integrations of these signals as compared to the OEt resonances confirm the formulation suggested by the microanalytical data. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data further confirmed the identity of the product (Figure S48). The molecule crystallized in space group P3̅c1 and resides on a crystallographic 3-fold rotation axis. The O–Al bond length is 1.719(10) Å, which is shorter than the sum of the single-bond covalent radii for these elements (1.89 Å), highlighting the strength of the Lewis adduct. The Sb–O bond length of 1.904(9) Å is significantly lengthened from the value of 1.8481(16) Å of free Mes3SbO.

2. Reactivity of Mes3SbO with (a) M(OEt)3 where M = B or Al, and (b) BPh3 .

Encouraged by the strength of the interaction with Al(OEt)3, we tested the ability of Mes3SbO to form an adduct with B(OEt)3, but only unreacted Mes3SbO was obtained following a workup analogous to that described above for Mes3SbO·Al(OEt)3. NMR spectra of Mes3SbO with 1–10 equiv of B(OEt)3 show no evidence of interaction between the two molecules (Figures S3 and S4). This result is unsurprising because trialkoxyboranes are among the weakest neutral trisubstituted B-based Lewis acids. , Donation from the O-based lone pairs into the empty B-based orbital is typically invoked to explain this attenuated acidity, and no isolable intermolecular Lewis adducts of phosphine oxides or arsine oxides with B(OR)3 are known when R is a simple alkyl or aryl group. It is noteworthy that a sufficiently large inductive effect can apparently override this lone-pair delocalization: very recently, the adduct Ph3PO·B(OTeF5)3 was isolated and characterized.

Reaction of Mes3SbO with BPh3

Given the lack of interaction between Mes3SbO and B(OEt)3, we explored the interaction of this stibine oxide with the stronger, albeit still relatively weak, Lewis acid BPh3. Combination of toluene solutions of the two species resulted in the precipitation of a colorless solid, whose limited solubility in a variety of organic solvents precluded NMR spectroscopic characterization. If the toluene solutions of the two reactants were layered and allowed to mix slowly by diffusion, then diffraction-quality crystals could be obtained (Figure ). Single-crystal X-ray diffraction revealed the product to be Mes3SbO·BPh3 and powder diffraction confirmed that the bulk sample comprised the same substance. The molecule crystallized in space group P3̅ and sits on a 3-fold rotation axis. The B–O bond length is 1.546(5) Å, which is significantly longer than the sum of the single-bond covalent radii of these elements (1.48 Å), and the Sb–O distance is 1.829(3) Å. This latter value is nearly unchanged from the Sb–O bond length of the free stibine oxide. Although the B center is unquestionably pyramidalized with a nearly ideal tetrahedral C–B–C angle of 109.99(15)°, these bond metrics collectively indicate that the interaction of Mes3SbO with BPh3 is weak.

1.

Thermal ellipsoid plot of Mes3SbO·BPh3. Ellipsoids are shown at the 50% probability level. H atoms have been omitted for the sake of clarity. Color code: Sb light blue, B pink, O red, C black.

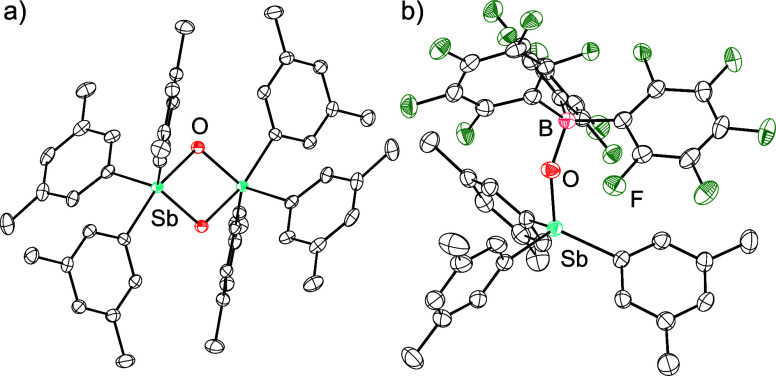

Reaction of Mes3PnO with B(C6F5)3

In contrast, the combination of Mes3SbO and the stronger Lewis acid B(C6F5)3 results in the formation of a strong adduct (Scheme ). In CDCl3, the product of the reaction displays a single 11B NMR signal at −0.75 ppm, and three sharp 19F NMR signals with Δδm,p = 5.1 ppm, both of which are consistent with a 4-coordinate B center. The single sets of sharp 19F and 13C signals stand in contrast to the 1H NMR spectrum, which features a mix of sharp and broad signals that decoalesce upon cooling to −20 °C (Figures S6 and S7), consistent with a hindered internal rotation that occurs on the NMR time scale. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction identified the product as Mes3SbO·B(C6F5)3 and confirmed the steric congestion (Figure ). The greater degree of congestion, as compared to Mes3SbO·BPh3, stems not only from the substitution around the periphery of the B-bound aryl ring but also from the decreased B–O distance of 1.488(5) Å. The greater Lewis acidity of B(C6F5)3 results in the formation of a stronger B–O bond. There is also a concomitant lengthening of the Sb–O distance to 1.884(3) Å from the distance of 1.848(2) Å in the free monomeric Mes3SbO.

3. Reactions of Mes3PnO (Pn = P, As, Sb) with B(C6F5)3 .

2.

Thermal ellipsoid plots of (a) Mes3SbO·B(C6F5)3 and (b) Mes3AsO·B(C6F5)3. Ellipsoids are shown at the 50% probability level. H atoms and solvent molecules have been omitted for the sake of clarity. For (b), only one of the two crystallographically independent molecules in the asymmetric unit is shown. Color code: Sb light blue, As purple, B pink, O red, C black, F green.

As with Mes3SbO, Mes3AsO was able to readily bind B(C6F5)3 and formed the adduct Mes3AsO·B(C6F5)3 (Figure ). Although isolable, solutions of the product would gradually decompose over time with signals from hydrolysis products such as [Mes3As(OH)][B(C6F5)3(OH)] developing. The NMR signals of Mes3AsO·B(C6F5)3 presented similarly to those of Mes3SbO·B(C6F5)3, but with full decoalescence of the signals at room temperature. The greater degree of steric congestion expected as a result of a shorter Pn–O bond would be consistent with this result. Indeed, the As–O distance of 1.7094(15) Å is less than the Sb–O distance above but close to the As–O distance of 1.698(2) Å in Ph3AsO·B(C6F5)3. The B–O distance of 1.533(3) Å in Mes3AsO·B(C6F5)3 is longer than that of 1.521(3) Å in the Ph3AsO adduct. This result is consistent with the influence of steric congestion described above.

In contrast, Mes3PO and B(C6F5)3 form an equilibrium mixture of the starting materials and Mes3PO·B(C6F5)3. Intermediate exchange between the free and adducted species results in broad signals in the 1H and 31P NMR spectra at room temperature. Cooling to −20 °C shifts the equilibrium and slows the rate of exchange sufficiently that signals, although still broad, can be observed (Figures S25–S28). The breadth of the signals, even at low temperature, suggests a highly dynamic equilibrium, and the adduct could not be isolated. Because Ph3PO, Ph3AsO, and Ph3SbO all form stable adducts with B(C6F5)3, , we ascribe the weakened interaction between Mes3PO and B(C6F5)3 to a combination of reduced basicity (as compared to the heavier congeners) and increased steric bulk (as compared to Ph3PO).

Reaction of Dipp3PnO with B(C6F5)3

The data above demonstrate that the steric pressure introduced by mesityl substituents is sufficient to disrupt the formation of a strong Mes3PO·B(C6F5)3 adduct, but not Mes3AsO·B(C6F5)3 or Mes3SbO·B(C6F5)3. We therefore investigated whether adduct formation would persist in the face of a further increased steric encumbrance. Combination of B(C6F5)3 and either Dipp3PO or Dipp3AsO resulted in no Dipp3PnO·B(C6F5)3 adduct formation, as assessed by NMR spectroscopic measurements on the reaction mixtures (Scheme , Figures S34–S40). In the absence of pnictine oxide binding to the borane, residual ether could be observed coordinating. In the case of the mixture of Dipp3PO and B(C6F5)3, additional weak signals (e.g., [B(C6F5)3(OH)]−) would develop in the NMR spectra over time, which we attribute to the unquenched reactivity of acid and base acting upon trace moisture.

4. Reactions of Dipp3PnO (Pn = P, As, Sb) with B(C6F5)3 .

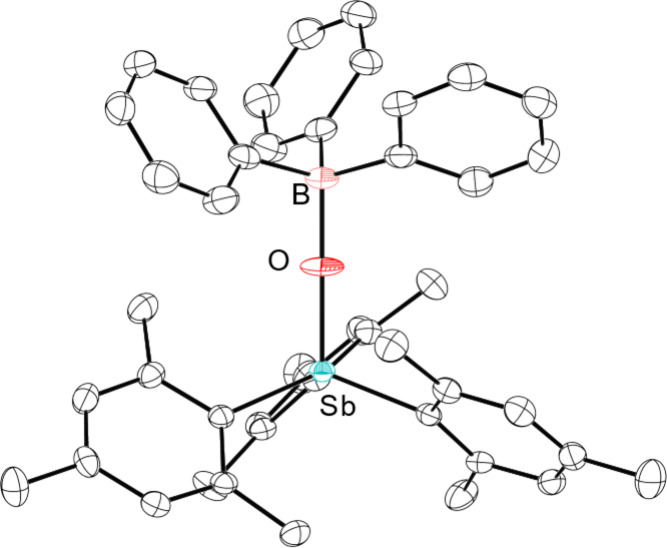

In contrast, Dipp3SbO and B(C6F5)3 react to form a single new species. In mixtures of Dipp3SbO and B(C6F5)3 in CDCl3, a 11B NMR signal appears at −0.37 ppm and Δδm,p(19F) = 5.3 ppm, strongly suggesting that a stable adduct persists in solution. For this Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3 adduct, even at room temperature, the 1H NMR signals are sharp and fully desymmetrized (Figure S29), suggesting that rotation about the Sb–C bond has been significantly slowed as compared to the less hindered stibine oxides. In the 19F NMR spectrum, the ortho signals are decoalesced and broad (Figure S31). These results point to the much greater degree of steric congestion present in Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3 but also to the persistence of the B–O interaction. An EXSY experiment performed on a mixture of B(C6F5)3 and 2 equiv Dipp3SbO, which forms one equivalent of the Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3 adduct and leaves one free Dipp3SbO, showed clear evidence of exchange among desymmetrized signals of each of the species (arising from rotation about Sb–C bonds). There was, however, no evidence of exchange between the free and bound stibine oxide (Figure S33). Although we were consistently unsuccessful at isolating pure bulk samples of the Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3 adduct, diffraction-quality crystals could be grown from a solution containing equimolar amounts of B(C6F5)3 and Dipp3SbO (Figure ). Crystallographic analysis confirmed the formation of the adduct Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3, which featured an Sb–O bond length of 1.8947(14) Å and a B–O bond length of 1.512(3) Å.

3.

Thermal ellipsoid plots of Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3. Ellipsoids are shown at the 50% probability level. H atoms are omitted for clarity. Color code: Sb light blue, B pink, O red, C black, F green.

Synthesis of [(3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO] n and (3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO·B(C6F5)3

To further systematically assess the impact of sterics on the formation of R3SbO·B(C6F5)3 adducts, we targeted the less encumbered (3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO·B(C6F5)3. To access the corresponding stibine oxide, (3,5-Me2Ph)3Sb was oxidized with PhIO; the white solid that formed is insoluble in a wide range of solvents. The IR spectrum of the product matches that of the starting stibine except for additional bands at 682 and 487 cm–1 (Figures S41 and S42), which we assign to Sb–O stretching and C–Sb–O bending modes, respectively. From the supernatant of the (3,5-Me2Ph)3Sb oxidation reaction mixture, a small portion of diffraction-quality crystals could be grown. Crystallographic analysis showed them to comprise the dimeric [(3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO]2 (Figure ). The molecule crystallized in space group P21/n and resides on a crystallographic inversion center. The Sb···Sb distance is 3.1258(6) Å and the central Sb2O2 rhomb has side lengths of 2.0784(17) and 1.9356(15) Å, an O–Sb–O angle of 77.77(7)°, and an Sb–O–Sb angle of 102.23(7)°. The Sb center has a distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry and the pseudoaxial Sb–O bond length is the longer of the two, consistent with the 3-center-4-electron bonding expected along the trigonal bipyramidal axis.

4.

Thermal ellipsoid plots of (a) [(3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO]2 and (b) (3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO·B(C6F5)3. Ellipsoids are shown at the 50% probability level. H atoms are omitted for clarity. Color code: Sb light blue, B pink, O red, C black, F green.

These results mirror those obtained upon oxidation of Ph3Sb, , and we propose that the bulk product is a [(3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO] n polymeric species analogous to (Ph3SbO) n (Scheme ).

5. Synthesis of [(3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO] n and Its Disaggregation with B(C6F5)3 .

Suspension of crude [(3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO] n in a solution of B(C6F5)3 led to its gradual consumption and the formation of (3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO·B(C6F5)3. This product displayed a 11B NMR signal at −0.98 ppm and sharp 19F NMR signals with Δδm,p = 4.5 ppm; features that are consistent with a tetrasubstituted B center. Both the 1H and 13C NMR spectra show only a single methyl resonance, indicating that, in contrast to the more sterically hindered Mes3SbO·B(C6F5)3, rotation about the Sb–C bond is rapid on the NMR time scale at room temperature.

The X-ray crystal structure of (3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO·B(C6F5)3 revealed the B–O bond length to be 1.487(4) Å, a value that is indistinguishable from that in Mes3SbO·B(C6F5)3. Although there is a difference in the steric congestion of (3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO·B(C6F5)3 and Mes3SbO·B(C6F5)3, both feature a strong and nearly equivalent dative interaction between the stibine oxide and the borane. This trend holds upon extension to the previously reported and even less sterically encumbered adduct Ph3SbO·B(C6F5)3, which has a B–O distance that is slightly longer (1.508(4) Å). In all three cases, a strong adduct forms with a B–O distance, consistent with the formation of a single bond.

Structural Comparisons

The body of structural data presently collected permits valuable comparisons to be drawn, shedding light on the relative influence of donicity and steric bulk on pnictine oxide Lewis basicity.

The previously reported Ph3PnO·B(C6F5)3 series showed a systematic trend of decreasing B–O bond lengths with increasing Pn atomic number (Table ), which is consistent with the formation of an increasingly strong dative interaction between the Lewis basic pnictine oxide and the Lewis acidic borane. This trend continues in the Mes3PnO·B(C6F5)3 series (Table ), in that the B–O bond is shorter for the stibine oxide adduct than for the arsine oxide adduct; the phosphine oxide adduct was weakened enough that it existed only in dynamic equilibrium and could not be isolated (vide supra). This effect was exaggerated upon further increasing the steric bulk of the pnictine oxides: the only Dipp3PnO·B(C6F5)3 species that could be observed, let alone isolated, was that formed by the stibine oxide.

1. Crystallographically Determined Bond Lengths.

| bond lengths

(Å) |

reference |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pn–O | B–O | ||

| Ph3PO·B(C6F5)3 | 1.497(2) | 1.538(3) | |

| Ph3AsO·B(C6F5)3 | 1.698(2) | 1.521(3) | |

| Ph3SbO·B(C6F5)3 | 1.877(2) | 1.508(4) | |

| Mes3AsO·B(C6F5)3 | 1.7094(15) | 1.533(3) | this work |

| Mes3SbO·B(C6F5)3 | 1.884(3) | 1.488(5) | this work |

| Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3 | 1.8947(14) | 1.512(3) | this work |

| (3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO·B(C6F5)3 | 1.864(2) | 1.487(4) | this work |

| Mes3SbO·BPh3 | 1.829(3) | 1.546(5) | this work |

Comparison of Ph3AsO·B(C6F5)3 and Mes3AsO·B(C6F5)3 highlights that the increased size of the R groups bound to the As atom lengthens and weakens the B–O bond. The weaker B–O interaction coincides with a shorter/stronger As–O bond. Similarly, the series of R3SbO·B(C6F5)3 compounds can be compared for R = Ph, 3,5-Me2Ph, Mes, and Dipp. The most sterically encumbered member of the series, Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3, indeed has the longest B–O bond.

Computational Investigation

The spectroscopic and X-ray structural data described above present a series of results that are consistent with stibine oxides having a greater capacity to form adducts with Lewis acids and that the adducts that form are stronger as compared to the lighter pnictine oxide congeners. We obtained further insight into these reactions computationally. We first computed the free energies for B(C6F5)3 reacting with Mes3PnO or Dipp3PnO (Pn = P, As, Sb) (Table ). For all adducts, there are stationary points in which a B–O bond persists. There is, however, a significant increase in the magnitude of ΔG rxn as the atomic number of the pnictogen increases. At the level of theory that was computationally tractable for these molecules (all substituents need to remain to capture steric effects), we do not anticipate accurate numerical agreement between theoretical and experimental thermochemistry. Nevertheless, the trends present in the computational data are informative. In both series, |ΔG rxn| increases from P to Sb, with the increase being more dramatic for the Dipp3PnO compounds. The ΔG rxn for Mes3PO is approximately the same as that for Dipp3AsO and any reactions computed to have a ΔG rxn at this level or less negative did not afford isolable adducts; all those with ΔG rxn values more negative than this threshold did afford isolable adducts. The influence of the steric bulk was clearly evident in the relative values of ΔG rxn for pairs of compounds with the same Pn atom but different R groups. The bulkier Dipp groups unilaterally decreased the favorability of the reaction, but the effect size increased with decreasing atomic number of the Pn atom. For Sb, the Lewis basicity of the R3SbO motif was able to overcome even the notable steric bulk of the Dipp groups.

2. Computational Free Energies of Reaction and Bond Critical Point Electron Densities.

| ΔG rxn (kJ mol–1) | ρbcp (a.u) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mes3PO·B(C6F5)3 | –75 | 0.108 |

| Mes3AsO·B(C6F5)3 | –118 | 0.119 |

| Mes3SbO·B(C6F5)3 | –165 | 0.127 |

| Dipp3PO·B(C6F5)3 | –30 | 0.103 |

| Dipp3AsO·B(C6F5)3 | –82 | 0.118 |

| Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3 | –129 | 0.125 |

Analysis of the topology of the electron density of the resulting adducts revealed that there were no significant differences in the nature of the Lewis acid–base interactions that occurred as either R or Pn was changed. That is, the overall shapes of the electron density (ρ) and the Laplacian of the electron density (∇2ρ) along the lengths of the bond paths did not change (Figure ). The importance of analyzing real space functions along the length of the bond path when studying polar covalent bonds has been previously highlighted. Across both series, there was a subtle trend whereby the value of ρ at the bond critical point (ρbcp; Table ) increased with increasing atomic number of the pnictogen. Likewise, both local minima in the Laplacian in the O–B interatomic valence region were progressively more negative with increasing pnictogen atomic number. These trends are subtle, but consistent with the ability of the stibine oxide to form a stronger interaction with the borane. The capacity of stibine oxides to form stronger Lewis acid–base interactions than lighter congeners will stem in part from the increased ability of the O-based lone pairs to donate to an acceptor, as we have shown earlier with a sterically unencumbered Lewis acid, H+. In the case of the more sterically hindered Lewis acids investigated here, the greater propensity for adduct formation will also have a contribution from the increase in the length of the Pn–O bond as the atomic number of the Pn atom increases (Table ), which decreases the steric strain in the adduct that forms.

5.

Analysis of (a) the electron density and (b) the Laplacian of the electron density along the O–B bond path for the Mes3PnO·B(C6F5)3 series where Pn = P, As, and Sb. Dotted vertical lines indicate the position of the bond critical point. (c, d) Analogous information for the Dipp3PnO·B(C6F5)3 series.

Conclusions

The unique electronic structure of the phosphoryl group affords phosphine oxides with significant chemical stability while still allowing them to engage in Lewis basic reactivity. The stability of the phosphoryl group derives from dative back-bonding interactions of the lone pairs on the terminal oxygen atom, which attenuates their ability to engage in donation to an external Lewis acid. In stibine oxides, the stiboryl group also features back-bonding from the oxygen atom, but to a much lesser extent. The pnictogen–oxygen bond is consequently weaker, but the Lewis basicity of the functional group is correspondingly enhanced. Here, we have demonstrated that this enhanced Lewis basicity can overcome levels of steric hindrance that otherwise prevent the formation of stable Lewis acid–base adducts for analogous phosphine oxides and arsine oxides.

Experimental Section

General Methods

Reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial vendors and used as received, unless otherwise specified. Triphenylborane, tris(3,5-dimethylphenyl)stibine, trimesitylstibine oxide, trimesitylphosphine oxide, tris(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)phosphine oxide, tris(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)arsine oxide, and tris(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)stibine oxide were synthesized according to literature protocols. ,,− All reactions were performed under a N2 atmosphere in an OMNI-lab glovebox or on a dual-manifold Schlenk line. All solvents were dried over 3 Å molecular sieves. NMR spectra were collected by using a Bruker Avance III HD 500 spectrometer equipped with a multinuclear Smart Probe. Unless otherwise specified, NMR experiments were performed at room temperature. Signals in the 1H and 13C NMR spectra are reported in ppm as chemical shifts from tetramethylsilane and were referenced using the CHCl3 (1H, 7.26 ppm) and CDCl3 (13C, 77.16 ppm) solvent signals. The frequencies of 11B NMR signals are reported in ppm as chemical shifts from BF3·OEt2 (referenced to an external sample of BF3·OEt2). The frequencies of 19F NMR signals are reported in ppm as chemical shifts from CFCl3 (referenced to an external sample of BF3·OEt2 at –152.8 ppm). 31P NMR signals are reported as chemical shifts from 85% H3PO4 (referenced to an external solution of triphenylphosphine in CDCl3 at −5.35 ppm). Infrared (IR) spectra were collected on KBr pellets by using a PerkinElmer Spectrum One FT-IR spectrometer. Elemental analysis was performed at the UC Berkeley College of Chemistry Microanalytical Facility. NMR data were processed using Mestrenova (version 12.0.2).

Synthesis of (Trimesitylstibine Oxide)·Triethoxyalane Adduct (Mes3SbO·Al(OEt)3)

A solution of Mes3SbO (70 mg, 0.14 mmol) in DCM (1 mL) was added to a suspension of Al(OEt)3 (23 mg, 0.14 mmol) in DCM (3 mL). The suspension was allowed to stir overnight. After 12 h, the mixture was passed through a Celite pad, with an additional aliquot of DCM (1 mL) used for quantitative transfer. The clarified filtrate was stripped of the solvent to yield a white powder. The solid was washed with pentane (3 × 0.5 mL) before being dried under vacuum. Yield: 83 mg (89%). Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown from the slow diffusion of pentane into a chloroform solution of the adduct. Found: C, 59.98%; H, 7.26%. Calc. for C33H48O4AlSb: C, 60.28%; H, 7.36%. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 6.95 (s, 6H), 3.63 (q, 6H), 2.47 (s, 18H), 2.30 (s, 9H), 0.99 (q, 9H). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 143.65, 142.96, 133.72, 130.94, 57.68, 24.21, 21.26, 21.01.

NMR Spectroscopy of Mes3SbO/B(OEt)3

Mixtures of Mes3SbO and B(OEt)3 in CDCl3 were prepared in ratios of 1:1, 1:5, and 1:10. 1H and 11B{1H} NMR spectra were acquired at room temperature (Figures S3 and S4).

Synthesis of (Trimesitylstibine Oxide)·Triphenylborane Adduct (Mes3SbO·BPh3)

A solution of Mes3SbO (50 mg, 0.10 mmol) in toluene (3 mL) was added to a solution of BPh3 (24 mg, 0.10 mmol) in toluene (3 mL). The mixture was allowed to stand for 1 h, during which time a white, microcrystalline solid precipitated from the solution. The supernatant was decanted, and the precipitate was washed with pentane (3 × 0.5 mL) before being dried under vacuum. Yield: 65 mg (87%). The insolubility of the product in a variety of solvents precluded NMR spectroscopic characterization. Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown by layering a toluene solution of Mes3SbO on top of a toluene solution of BPh3. Powder X-ray diffraction was used to confirm the purity of the bulk product (Figure S5).

Synthesis of (Trimesitylstibine Oxide)·Tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane Adduct Chloroform Solvate (Mes3SbO·B(C6F5)3·CHCl3)

A solution of Mes3SbO (60 mg, 0.12 mmol) in DCM (2 mL) was added to a solution of B(C6F5)3 (62 mg, 0.12 mmol) in DCM (2 mL), and the mixture was allowed to stand for 5 min before being stripped of solvent to yield a crude yellow oil. The residue was extracted with chloroform (3 mL) and layered under pentane, yielding colorless crystals after 36 h. Yield: 71 mg (52%). Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown from the slow diffusion of pentane into a solution of the product. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 6.91 (s, 6H), 2.5–2.1 (br, 18H), 2.5–2.1 (br, 9H). 11B{1H} NMR (160 MHz, CDCl3) δ: −0.75. 19F{1H} NMR (470 MHz, CDCl3) δ: −133.21 (d, 6F), −160.21 (t, 3F), −165.35 (t, 6F). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 143.16, 134.22, 131.14, 23.05, 21.06. Powder X-ray diffraction was used to confirm the purity of the bulk product (Figure S11).

Synthesis of Trimesitylarsine (Mes3As)

Magnesium turnings (0.57 g, 23.45 mmol) were suspended in THF (15 mL) with 1,2-dibromoethane (0.507 mL, 5.862 mmol) at 0 °C. The mixture was brought to reflux and then cooled to room temperature, and 2-bromomesitylene (2.652 mL, 17.58 mmol) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was then refluxed until the magnesium was fully consumed (6 h). AsCl3 (0.492 g, 5.862 mmol) was then added dropwise into the yellow solution of mesitylmagnesium bromide at room temperature. The reaction mixture was then refluxed for 14 h. The resulting mixture was cooled to room temperature, diluted with diethyl ether (200 mL), and washed with water (200 mL). The aqueous phase was back-extracted with diethyl ether (2 × 50 mL), and the organic phases were combined, washed with water (3 × 100 mL), and washed with brine (1 × 100 mL). The organic phase was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate for 30 min and stripped of solvent under reduced pressure to yield a crude yellow oil. Acetonitrile was added dropwise with sonication to afford a white powder that was collected via vacuum filtration and dried in vacuo. Yield: 1.4 g (56%). Analytical data match those previously reported for this compound. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 6.78 (s, 3H), 2.25 (s, 9 H), 2.14 (s, 18).

Synthesis of Trimesitylarsine Oxide (Mes3AsO)

Mes3As (400 mg, 0.924 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (10 mL). Hydrogen peroxide (9.249 mL, 4.624 mmol, 50% aqueous solution) was added dropwise, and the heterogeneous reaction was allowed to stir for 1 h. The reaction was quenched by the addition of a saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution (100 mL) and a 5% aqueous solution of Na2S2O3 (200 mL). The reaction was diluted with additional DCM (50 mL) and the organic phase was separated. The aqueous phase was back-extracted with DCM (2 × 150 mL), and the organic phases were combined, washed with water (3 × 100 mL), and washed with brine (1 × 100 mL). The organic phase was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate for 30 min and stripped of solvent under reduced pressure to yield a transparent oil. The oil was taken up in minimal hexanes (10 mL) and placed in a freezer overnight to afford colorless crystals. Yield: 369 mg (89%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 6.84 (s, 6H), 2.33 (br, 18H), 2.27 (s, 9H). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 141.85, 140.84, 135.53, 131.15, 22.98, 21.09. Powder X-ray diffraction data from freshly prepared bulk solid agreed with the simulated powder diffractogram generated from the crystal structure (Figure S16).

Synthesis of (Trimesitylarsine Oxide)·Tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane Adduct Chloroform Solvate (Mes3AsO·B(C6F5)3·CH2Cl2)

A solution of Mes3AsO (30 mg, 0.067 mmol) in DCM (2 mL) was combined with a solution of B(C6F5)3 (34 mg, 0.067 mmol) in DCM (2 mL). The reaction mixture was allowed to stand for 5 min and then passed through a Celite pad, using an additional aliquot of DCM (1 mL) for quantitative transfer. Pentane (3 mL) was added to the filtrate, which was concentrated under reduced pressure until it was cloudy. The solution was allowed to stand at room temperature to afford colorless plates. The supernatant was decanted, and the crystals were washed with minimal pentane. Yield: 24 mg (35%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 6.86 (s, 3H), 6.80 (s, 3H), 2.55 (s, 9H), 2.27 (s, 9H), 2.05 (s, 9H). 11B{1H} NMR (160 MHz, CDCl3) δ: −0.27. 19F{1H} NMR (470 MHz, CDCl3) δ: −131.82 (d, 6F), −159.67 (t, 3F), −165.53 (t, 6F). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 144.52, 142.97, 140.59, 132.06, 131.72, 131.67, 22.50, 20.90. Powder X-ray diffraction data from freshly prepared bulk solid agreed with the simulated powder diffractogram generated from the crystal structure (Figure S21).

NMR Spectroscopy of Mes3PO/B(C6F5)3

A 1:1 mixture of Mes3PO and B(C6F5)3 in CDCl3 was prepared and 1H and 31P{1H} NMR spectra were acquired at 20, 10, 0, −10, and −20 °C (Figures S25–S28). Reference spectra of Mes3PO alone at room temperature and −20 °C were also collected (Figures S22–S24).

Synthesis of (Tris(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)stibine oxide)·Tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane Adduct (Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3)

A solution of Dipp3SbO (60 mg, 0.12 mmol) in DCM (2 mL) was combined with a solution of B(C6F5)3 (62 mg, 0.12 mmol) in DCM (2 mL). The solution was allowed to stand for 5 min. The reaction mixture was stripped of solvent to yield a crude yellow oil, which was taken up in pentane (3 mL) and passed through a Celite pad with an additional aliquot of pentane (1 mL) used for quantitative transfer. The clarified filtrate was stripped of the solvent to yield a yellow residue. Yield: 33 mg (31%). Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown by slow concentration of a DCM/cyclohexane solution of the product. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.41 (t, 3H), 7.31 (d, 3H), 7.19 (d, 3H), 3.33 (br, 3H), 2.45 (br, 3H), 0.92 (d, 9H), 0.87 (d, 9H), 0.68 (d, 9H) 0.58 (d, 9H). 11B{1H} NMR (160 MHz, CDCl3) δ: −0.87. 19F{1H} NMR (470 MHz, CDCl3) δ: −128.17, −129.79 (b, 6F), −159.84(t, 3F), −165.17(t, 6F). The compound was unstable both in solution and in the solid-state preventing successful elemental analysis.

NMR Spectroscopy of Dipp3AsO/B(C6F5)3 and Dipp3PO/B(C6F5)3

Mixtures of B(C6F5)3 with Dipp3PO and Dipp3AsO in CDCl3 (1:1 ratio of borane and pnictine oxide) were prepared, and 1H, 11B{1H}, 19F{1H}, and 31P{1H} NMR spectra were acquired (Figures S34–S40).

Synthesis of Tris(3,5-dimethylphenyl)stibine Oxide ((3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO) n

A solution of (3,5-Me2Ph)3Sb (98 mg, 0.22 mmol) in DCM (10 mL) was added to a suspension of iodosobenzene (49 mg, 0.22 mmol) in DCM (2 mL). The resulting yellow suspension was allowed to stir at room temperature. After 1.5 h, the iodosobenzene had been consumed, and a white, amorphous solid had precipitated from the reaction mixture. The supernatant was decanted, and the product was washed with pentane (3 × 1.5 mL) before being dried under vacuum. Yield: 86 mg (85%). Satisfactory elemental analysis could not be obtained; a problem that was also encountered with the previously reported (Ph3SbO) n . Crystals of the dimeric species ((3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO)2 suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown from the slow concentration of the decanted supernatant. IR (KBr, cm–1): 682 (νSb–O, stretch), 487 (δC–Sb–O, bend).

Synthesis of (Tris(3,5-dimethylphenyl)stibine oxide)·Tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane Adduct ((3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO·B(C6F5)3)

A solution of ((3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO) n (61 mg, 0.14 mequiv of monomer) in DCM (2 mL) was combined with a solution of B(C6F5)3 (69 mg, 0.13 mmol) in DCM (2 mL). The solution was allowed to stand for 5 min. The solution was passed through a Celite pad with an additional aliquot of DCM (1 mL) used for quantitative transfer. The clarified filtrate was stripped of solvent and the solid was washed with pentane (3 × 1 mL) to yield a white powder. Yield: 54 mg (84%). Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown from the slow diffusion of pentane into a chloroform solution of the product. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.27 (s, 3H), 7.11 (s, 6H), 2.33 (s, 18H). 11B{1H} NMR (160 MHz, CDCl3) δ: −0.98. 19F{1H} NMR (470 MHz, CDCl3) δ: −132.88 (d, 6F), −160.62 (t, 3F), −165.07 (t, 6F). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 140.74, 135.52, 131.52, 126.41, 21.45. Powder X-ray diffraction data from freshly prepared bulk solids agreed with the simulated powder diffractogram generated from the crystal structure (Figure S47).

X-ray Crystallography

Crystals of Mes3SbO·Al(OEt)3, Mes3SbO·BPh3, Mes3SbO·B(C6F5)3·CHCl3, Mes3AsO, Mes3AsO·B(C6F5)3·CH2Cl2, Dipp3SbO·B(C6F5)3, ((3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO)2, and (3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO·B(C6F5)3 were grown as described above, selected under a microscope, loaded onto a MiTeGen polyimide sample loop using Type NVH Cargille immersion oil, and mounted onto a Rigaku XtaLAB Synergy-S single-crystal X-ray diffractometer. Each crystal was cooled to 100 K under a stream of nitrogen. Diffraction of Cu Kα radiation from a PhotonJet-S microfocus source was detected by using a HyPix6000HE hybrid photon counting detector. Screening, indexing, data collection, and data processing were performed with CrysAlisPro. The structures were solved using SHELXT and refined using SHELXL following established strategies. − All non-H atoms were refined anisotropically. C-bound H atoms were placed at calculated positions and refined with a riding model and coupled isotropic displacement parameters (1.2 × Ueq for nonmethyl C–H atoms and 1.5 × Ueq for methyl groups).

Powder X-ray Diffraction

Bulk samples of Mes3SbO·BPh3, Mes3AsO, Mes3AsO·B(C6F5)3·(CH2Cl2), (3,5-Me2Ph)3SbO·B(C6F5)3, and Mes3SbO·B(C6F5)3·(CHCl3) were ground using an agate mortar and pestle. The fine powders were each loaded onto a MiTeGen polyimide sample loop using Type NVH Cargille immersion oil and mounted onto a Rigaku XtaLAB Synergy-S single-crystal X-ray diffractometer. The powder was cooled to 100 K under a stream of nitrogen. The diffraction of Cu Kα radiation was collected while the sample underwent a Gandolfi scan. Data collection and processing were performed using CrysAlisPro. Simulated powder diffractograms were generated from experimental crystal structures using Mercury. , These simulated diffractograms were compared with the experimentally measured powder diffractograms.

Computational Experiments

All geometry optimizations and frequency calculations were performed in the gas phase using ORCA 5.0.1. − Geometry optimizations and frequency calculations were performed using crystallographic input coordinates at the BP86/def2-SVP level of theory, with the RI approximation and def2/J auxiliary basis set. − For all calculations, dispersion corrections were applied using Grimme’s D3 method with Becke-Johnson damping. Electron densities used for topological analysis were generated at the DKH-PBE0/old-DKH-TZVPP level of theory using the BP86/def2-SVP-optimized coordinates, with the RIJCOSX approximation and SARC/J auxiliary basis set. − Topological analyses were performed using MultiWFN. ,

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NSF through CAREER award 2236365 and MRI grant 2018501, the ACS through PRF grant 66098-ND3, and the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation through a Beckman Young Investigator Award to T.C.J.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.organomet.5c00212.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Yang T., Andrada D. M., Frenking G.. Dative versus electron-sharing bonding in N-oxides and phosphane oxides R3EO and relative energies of the R2EOR isomers (E = N, P; R = H, F, Cl, Me, Ph). A theoretical study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20:11856–11866. doi: 10.1039/C8CP00951A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger J. S., Johnstone T. C.. Recent advances in the stabilization of monomeric stibinidene chalcogenides and stibine chalcogenides. Dalton Trans. 2024;53:8524–8534. doi: 10.1039/D4DT00506F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijai Anand A. S., Perinbanathan S., Singh I., Panicker R. R., Boominathan T., Gokul A. S., Sivaramakrishna A.. Diverse Catalytic Applications of Phosphine Oxide-Based Metal Complexes. ChemCatChem. 2024;16:e202400844. doi: 10.1002/cctc.202400844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Platt A. W. G.. Lanthanide phosphine oxide complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017;340:62–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2016.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett M. A., Brassington D. S., Coles S. J., Hursthouse M. B.. Lewis acidity of tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane: crystal and molecular structure of B(C6F5)3·OPEt3 . Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2000;3:530–533. doi: 10.1016/S1387-7003(00)00129-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett M. A., Brassington D. S., Light M. E., Hursthouse M. B.. Organophosphoryl adducts of tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane; crystal and molecular structure of B(C6F5)3·Ph3PO. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2001:1768–1772. doi: 10.1039/b100981h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann V.. Solvent effects on the reactivities of organometallic compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1976;18:225–255. doi: 10.1016/S0010-8545(00)82045-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann P., Greb L.. What Distinguishes the Strength and the Effect of a Lewis Acid: Analysis of the Gutmann-Beckett Method. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022;61:e202114550. doi: 10.1002/anie.202114550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffen J. R., Bentley J. N., Torres L. C., Chu C., Baumgartner T., Caputo C. B.. A Simple and Effective Method of Determining Lewis Acidity by Using Fluorescence. Chem. 2019;5:1567–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.03.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welch G. C., Stephan D. W.. Facile Heterolytic Cleavage of Dihydrogen by Phosphines and Boranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:1880–1881. doi: 10.1021/ja067961j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas A. J. P., Culotta B. J., Warren T. H., Grimme S., Stute A., Fröhlich R., Kehr G., Erker G.. Capture of NO by a Frustrated Lewis Pair: A New Type of Persistent N-Oxyl Radical. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:7567–7571. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger J. S., Weng M., George G. N., Johnstone T. C.. Isolation, bonding, and reactivity of a monomeric stibine oxide. Nat. Chem. 2023;15:633–640. doi: 10.1038/s41557-023-01160-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merijanian A., Zingaro R. A.. Arsine Oxides. Inorg. Chem. 1966;5:187–191. doi: 10.1021/ic50036a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii T., Kitagawa Y., Hasegawa Y., Imoto H., Naka K.. Emission Properties of Eu(III) Complexes Containing Arsine and Phosphine Ligands with Annulated Structures. Inorg. Chem. 2022;61:17662–17672. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c02757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoji H., Fujii T., Sumida A., Kitagawa Y., Hasegawa Y., Imoto H., Naka K.. Intensive emission of Eu(III) β-diketonate complexes with arsine oxide ligands. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2023;11:15608–15615. doi: 10.1039/D3TC03297C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoji H., Aoyama Y., Inage K., Nakamura M., Yanagihara T., Yuhara K., Kitagawa Y., Hasegawa Y., Ito S., Tanaka K., Imoto H., Naka K.. Highly Efficient and Thermally Durable Luminescence of 1D Eu3+ Coordination Polymers with Arsenic Bridging Ligands. Chem. - Eur. J. 2024;30:e202400615. doi: 10.1002/chem.202400615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kather R., Svoboda T., Wehrhahn M., Rychagova E., Lork E., Dostál L., Ketkov S., Beckmann J.. Lewis-Acid Induced Disaggregation of Dimeric Arylantimony Oxides. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:5932–5935. doi: 10.1039/C5CC00738K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger J. S., Johnstone T. C.. A Sterically Accessible Monomeric Stibine Oxide Activates Organotetrel(IV) Halides, Including C-F and Si–F Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024;146:19350–19359. doi: 10.1021/jacs.4c05394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger J. S., Johnstone T. C.. Unsupported monomeric stibine oxides (R3SbO) remain undiscovered. Chem. Commun. 2021;57:3484–3487. doi: 10.1039/D1CC00619C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger J. S., Wang X., Johnstone T. C.. H-Atom Assignment and Sb–O Bonding of [Mes3SbOH][O3SPh] Confirmed by Neutron Diffraction, Multipole Modeling, and Hirshfeld Atom Refinement. Inorg. Chem. 2021;60:16048–16052. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c02229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger J. S., Getahun A., Johnstone T. C.. Variation in pnictogen–oxygen bonding unlocks greatly enhanced Bro̷nsted basicity for the monomeric stibine oxide. Dalton Trans. 2023;52:11325–11334. doi: 10.1039/D3DT02113K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler F., Schmidbaur H.. Isostere metallorganische Verbindungen, XI. Koordinationsverbindungen von Metallsilanolaten mit Trimethylphosphinoxid und Trimethylaminoxid. Chem. Ber. 1968;101:1656–1663. doi: 10.1002/cber.19681010516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feher F. J., Budzichowski T. A., Weller K. J.. Oxide-base adducts of aluminum: X-ray crystal structures of Me3Al(OPPh3), Me3Al(ONMe3) and [(CH3)3SiO]3Al(OPPh3) Polyhedron. 1993;12:591–599. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5387(00)84973-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amenta D. S., Ayres B. R., Jurica J., Gilje J. W.. The equilibrium between aluminum alkoxides and 1-(diphenylphosphinoyl)-2-(diphenylphosphino)ethane. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2002;336:115–119. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1693(02)00843-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. W.. The Lewis acidity of trialkoxyboranes: a reinvestigation. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1973:1628–1630. doi: 10.1039/dt9730001628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaev I. B., Bregadze V. I.. Lewis acidity of boron compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014;270–271:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer L., Hoffmann K. F., Riedel S.. A Rare Example of a Gallium-Based Lewis Superacid: Synthesis and Reactivity of Ga(OTeF5)3 . Chem. - Eur. J. 2024;30:e202403266. doi: 10.1002/chem.202403266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen W. E., Briles G. H., Schulz D. N.. Preparation and Reactions of Triphenylstibine Oxide. Phosphorus Relat. Group V Elem. 1972;2:147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Carmalt C. J., Crossley J. G., Norman N. C., Orpen A. G.. The structure of amorphous Ph3SbO: information from EXAFS (extended X-ray absorption fine structure) spectroscopy. Chem. Commun. 1996:1675–1676. doi: 10.1039/cc9960001675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist-Kleissler B., Wenger J. S., Johnstone T. C.. Analysis of Oxygen-Pnictogen Bonding with Full Bond Path Topological Analysis of the Electron Density. Inorg. Chem. 2021;60:1846–1856. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c03308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borger J. E., Ehlers A. W., Lutz M., Slootweg J. C., Lammertsma K.. Stabilization and Transfer of the Transient [Mes*P4]− Butterfly Anion Using BPh3 . Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:613–617. doi: 10.1002/anie.201508916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa S., Yamamichi H., Yamamoto Y., Ando K.. Pentacoordinate Organoantimony Compounds That Isomerize by Turnstile Rotation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3418–3419. doi: 10.1021/ja808113q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alyea E. C., Malito J.. Non-Metal Derivatives of the Bulkiest Known Tertiary Phosphine, Trimesitylphosphine. Phosphorus, Sulfur, Silicon Relat. Elem. 1989;46:175–181. doi: 10.1080/10426508909412063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chishiro A., Konishi M., Inaba R., Yumura T., Imoto H., Naka K.. Tertiary arsine ligands for the Stille coupling reaction. Dalton Trans. 2022;51:95–103. doi: 10.1039/D1DT02955J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaku Oxford Diffraction CrysAlisPro software system, version 1.171.40.78a; Rigaku Corporation: Wroclaw, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M.. SHELXT – Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A. 2015;71:3–8. doi: 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M.. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL . Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 2015;71:3–8. doi: 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller P.. Practical suggestions for better crystal structures. Crystallogr. Rev. 2009;15:57–83. doi: 10.1080/08893110802547240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae C. F., Edgington P. R., McCabe P., Pidcock E., Shields G. P., Taylor R., Towler M., van de Streek J.. Mercury: Visualization and Analysis of Crystal Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006;39:453–457. doi: 10.1107/S002188980600731X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae C. F., Bruno I. J., Chisholm J. A., Edgington P. R., McCabe P., Pidcock E., Rodriguez-Monge L., Taylor R., van de Streek J., Wood P. A.. Mercury CSD 2.0 – New Features for the Visualization and Investigation of Crystal Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008;41:466–470. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807067908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F.. The ORCA program system. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012;2:73–78. doi: 10.1002/wcms.81. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F.. Software update: the ORCA program system, version 4.0. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018;8:e1327. doi: 10.1002/wcms.1327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F., Wennmohs F., Becker U., Riplinger C.. The ORCA quantum chemistry program package. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;152:224108. doi: 10.1063/5.0004608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.. Density-functional approximation for the correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. B. 1986;33:8822–8824. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D.. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F., Ahlrichs R.. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005;7:3297–3305. doi: 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F., Wennmohs F., Hansen A., Becker U.. Efficient, approximate and parallel Hartree-Fock and hybrid DFT calculations. A ‘chain-of-spheres’ algorithm for the Hartree-Fock exchange. Chem. Phys. 2009;356:98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphys.2008.10.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S., Antony J., Ehrlich S., Krieg H.. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;132:154104. doi: 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P., Ernzerhof M., Burke K.. Rationale for mixing exact exchange with density functional approximations. J. Chem. Phys. 1996;105:9982–9985. doi: 10.1063/1.472933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P., Burke K., Ernzerhof M.. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis D. A., Chen X.-Y., Landis C. R., Neese F.. All-Electron Scalar Relativistic Basis Sets for Third-Row Transition Metal Atoms. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:908–919. doi: 10.1021/ct800047t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis D. A., Neese F.. All-Electron Scalar Relativistic Basis Sets for the Lanthanides. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009;5:2229–2238. doi: 10.1021/ct900090f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis D. A., Neese F.. All-Electron Scalar Relativistic Basis Sets for the Actinides. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:677–684. doi: 10.1021/ct100736b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis D. A., Neese F.. All-electron scalar relativistic basis sets for the 6p elements. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2012;131:1292. doi: 10.1007/s00214-012-1292-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T., Chen F.. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012;33:580–592. doi: 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T.. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists, Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024;161:082503. doi: 10.1063/5.0216272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.