SUMMARY

The apoplast is a critical interface in plant–pathogen interactions, particularly in the context of pattern‐triggered immunity (PTI), which is initiated by recognition of microbe‐associated molecular patterns. Our study characterizes the proteomic profile of the Arabidopsis apoplast during PTI induced by flg22, a 22‐amino‐acid bacterial flagellin epitope, to elucidate the output of PTI. Apoplastic washing fluid was extracted with minimal cytoplasmic contamination for liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry analysis. By comparing our data to publicly available transcriptome profiles of flg22 treatment from 1 to 18 h, we observed that several highly abundant proteins exhibit relatively unchanged gene expression across all time points. We also observed topological bias in peptide recovery of 19 enriched receptor‐like kinases with peptides predominantly recovered from their ectodomains. Notably, tetraspanin 8, an exosome marker, was enriched in PTI samples. We additionally confirmed increased concentrations of exosomes during PTI. This study enhances our understanding of the proteomic changes in the apoplast during plant immune responses and lays the groundwork for future investigations into the molecular mechanisms of plant defense under recognition of pathogen molecular patterns.

Keywords: pattern‐triggered immunity, microbe‐associated molecular patterns, apoplast, proteomics, extracellular vesicle, tetraspanin, flg22

Significance Statement

Pattern‐triggered immunity confers broad‐spectrum defense, but its output in the apoplast remains poorly understood. This study defines the proteomic profile of the Arabidopsis leaf apoplast following flg22 treatment, revealing receptor extracellular‐domain shedding and enhanced exosome production, thereby expanding our understanding of plant immune regulation. The results also provide a resource for researchers to investigate the functional roles of these proteins in plant immunity.

INTRODUCTION

Plants are constantly exposed to microbial pathogens, necessitating the evolution of sophisticated defense mechanisms to ensure survival (Boller & He, 2009; Mott et al., 2014). Pattern‐triggered immunity (PTI) represents the first layer of inducible defense, activated by the recognition of conserved microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (Boller & He, 2009). A well‐characterized example is the recognition of flg22, a 22 amino acid peptide derived from bacterial flagellin, by the leucine‐rich repeat receptor kinase FLAGELLIN‐SENSING 2 (FLS2) (Zipfel et al., 2004). FLS2 associates with its coreceptor BRI1‐ASSOCIATED RECEPTOR KINASE 1 (BAK1) in a ligand‐dependent manner (Chinchilla et al., 2007). These recognition events trigger a complex regulatory network that initiates a variety of defense responses, including the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), transcriptional reprogramming, and callose deposition, and accumulation of pathogenesis‐related (PR) proteins (DeFalco & Zipfel, 2021; Han & Schneiter, 2024; Mott et al., 2014). PTI serves as a critical barrier to pathogen invasion and underscores the importance of studying the molecular mechanisms that underpin this process (Boller & He, 2009; DeFalco & Zipfel, 2021).

The apoplast is the intercellular space that contains gas and water, situated between cell membranes and within the cell wall matrix (Farvardin et al., 2020). This compartment serves as a critical battleground for plant–microbe interactions and is the location of colonization by foliar bacteria and many other pathogens (Roussin‐Léveillée et al., 2024). The apoplast of plants is typically characterized by limited water and nutrient availability, presenting a challenging environment for microbial proliferation (Aung et al., 2018; Freeman & Beattie, 2009; Gentzel et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Lovelace et al., 2018; O'Leary et al., 2016; Xin et al., 2016). The alteration of the apoplastic environment has been proposed to impact pathogen resistance (Roussin‐Léveillée et al., 2024). Studies of apoplastic secreted proteins, peptides, and specialized metabolites have provided some insights into apoplastic defense (Anderson et al., 2014; Delaunois et al., 2014; Gentzel et al., 2022; Martínez‐González et al., 2018; Serag et al., 2023). Apoplastic proteins have been found to perform diverse functions, including reinforcing the plant cell wall, signal transduction, and inhibition of microbial growth (Alexandersson et al., 2013; Munzert & Engelsdorf, 2025). Secreted proteins include PR proteins, enzymes for cell wall modification, enzymes for generation of ROS, and redox regulatory proteins (Camejo et al., 2016; Nishimura, 2016; van Loon et al., 2006). Secreted proteases, chitinases, and other hydrolytic enzymes can mediate defense by modification of plant or pathogen structural targets, or the virulence factor targets such as pathogen effector proteins (Van Der Hoorn, 2008; Wang, Sun, et al., 2020; Wang, Wang, & Wang, 2020). In addition to secreted proteins, plant extracellular vesicles (P‐EVs) are emerging as crucial players in immunity. P‐EVs are membrane‐bound nanostructures classified into MVBs (multivesicular bodies), EXPO (exocyst‐positive organelle), Penetration 1 (Pen1)‐positive EVs, vacuoles, and autophagosomes based on their biogenesis (Nemati et al., 2022). They facilitate intercellular and interkingdom communication by transporting bioactive molecules, including proteins and RNAs (Cai et al., 2019; Rutter & Innes, 2017). EVs are implicated in enhancing plant defense through the delivery of immune‐related cargo, such as small RNAs and proteins, and contribute to the suppression of pathogen virulence via cross‐kingdom RNA interference (Liu et al., 2021). Exosomes, a type of MVB‐derived EV with a median size of approximately 30–150 nm in Arabidopsis, have been characterized as a major subtype of P‐EVs (Huang et al., 2021). Notably, markers such as tetraspanin‐8 (TET8) have been identified in defense‐associated exosomes, highlighting their potential role in coordinating immune responses (Wang et al., 2023).

Proteomics approaches using suspension cell culture systems have provided important information on extracellular proteins for understanding the molecular mechanisms involved in pathogen infections (Kaffarnik et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2009). While suspension cell culture systems offer the advantage of limiting cytoplasmic contamination, they do not fully replicate the actual conditions of infection or the specific cellular responses observed in intact tissue apoplast, which are critical for understanding the spatial and temporal dynamics upon pathogens interacting. Characterization of apoplastic proteomics typically involves isolating apoplastic washing fluid (AWF), followed by protein identification using techniques such as liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) (Jung et al., 2008). Isolation of AWF is typically conducted using vacuum or pressure infiltration with water followed by low‐speed centrifugation (Agrawal et al., 2010). This technique is efficient in extracting leaf apoplast contents while minimizing cytoplasmic contamination. To assess cytoplasmic contamination in AWF, researchers commonly use enzymatic assays and immunoblotting techniques. Enzymatic markers such as glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) and malate dehydrogenase are measured and compared with levels found in whole cell lysates; significantly elevated activities in AWF indicate contamination from cytoplasmic contents (Borniego et al., 2020; Delaunois et al., 2013; O'Leary et al., 2016). The dynamic nature of the apoplastic proteome and its response to MAMPs remain an active area of research. A recent study by Karimi et al. (2025) revealed the role of apoplastically localized proteasomes in processing of intact release immunogenic MAMPs.

The apoplast proteomic profile of PTI, particularly at later stages when immune signaling leads to apoplastic changes that restrict pathogen growth, remains poorly characterized. Investigating the apoplastic proteome under the pre‐activated PTI conditions, when leaves exhibit enhanced defense responses and reduced bacterial proliferation, is critical to understanding PTI immune outputs. In this study, we reported the leaf apoplastic proteome of Arabidopsis thaliana following PTI induction by flg22, with tissue collected 16‐h post‐treatment. AWF was extracted by low‐speed centrifugation with minimal cytoplasmic contamination and analyzed using LC–MS/MS. Our analyses identified proteins significantly enriched or depleted during PTI. We also compared these proteome profiles with a publicly available transcriptomics time‐course data collected under the same experimental conditions (Hillmer et al., 2017), providing insights into the dynamics of late PTI outputs at the day post‐treatment. Notably, we observed an increase in the exosome marker TET8 and a higher abundance of exosome particles during PTI. Additionally, the observation of ectodomain bias of surface receptor kinases under PTI provided potential insight of immune signaling processing. Our study provides a detailed snapshot of the proteomic changes in the A. thaliana apoplast during PTI elicited by flg22, offering a foundation for understanding the molecular mechanisms governing plant immune responses.

RESULTS

AWF isolation and proteomics analyses

A total of 130–150 leaves were collected for each sample to isolate AWF, yielding 3.5–5.0 ml per sample across both mock and flg22 treatments. To assess cytoplasmic contamination, G6PDH activity was measured in the AWF and compared to total leaf extracts. The average G6PDH activity in mock‐treated AWF was 0.55 and 0.16 mU ml−1 in flg22‐treated AWF, both substantially lower than the 12.4 mU ml−1 observed in total leaf extracts. Both mock and flg22 samples exhibited less than 5% G6PDH activity relative to total leaf extracts, with no significant difference between treatments (Figure S1), indicating minimal cytoplasmic contamination.

Proteomic analysis of the AWF samples revealed consistent protein abundance distributions across biological replicates, as shown by similar median log10 protein abundances between flg22‐treated and mock‐treated samples (Figure S2). Principal component analysis further demonstrated clear separation between flg22 and mock samples, with the first two principal components accounting for 27.9 and 25.9% of the total variance, respectively (Figure 1a). A comprehensive proteomic survey identified a total of 3667 proteins across all samples. Differential abundance analysis using a volcano plot (Figure 1b) revealed that 108 proteins were significantly enriched (log2FC ≥1, P < 0.05) and 255 proteins were significantly decreased (log2FC ≤−1, P < 0.05) in flg22‐treated samples compared to mock controls. Proteins with exceptionally high or low abundance changes (log2FC ≥5 or ≤−5) were specially highlighted. Additionally, pre‐treatment with flg22 16 h before Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 infection resulted in more than 1000‐fold reduction in bacterial populations compared to mock‐treated controls at 1 dpi in Col‐0 (Figure S4).

Figure 1.

Proteomics analyses of Arabidopsis leaf apoplast.

(a) Principal component analysis of flg22 and mock samples. Clustering of samples indicates distinct profiles between the flg22 and mock treatments with 27.9% variance in dimension 1 and 25.9% in dimension 2.

(b) Volcano plot shows the total 3667 detected proteins in both flg22‐treated and mock‐treated samples. The x‐axis represents the log2 fold change (log2FC) in protein abundance (flg22/mock), while the y‐axis shows the −log10 of the P‐value. Proteins with significantly enriched abundance in flg22 (log2FC ≥1, P < 0.05) are highlighted in red; lower abundance (log2FC ≤−1, P < 0.05) are shown in blue. Proteins with log2FC ≥5 or log2FC ≤−5 are specially highlighted on the plot, indicating exceptionally increased or decreased abundance, respectively.

Comparison of PTI apoplastic protein enrichment relative to time course transcriptome profiles

We manually classified apoplastic proteins differentially enriched during PTI into six groups based on Araport protein annotations: (1) receptor‐like kinases/receptor‐like proteins (RLKs/RLPs), (2) redox and redox‐associated proteins, (3) hydrolytic enzymes, (4) peptides, (5) extracellular vesicle‐associated proteins, and (6) others (Figure 2). Peroxidases and majority of hydrolytic enzymes have predicted signal peptides. As expected, proteins associated with vesicle trafficking lacked predicted signal peptides as the proposed function to be secreted in non‐canonical protein‐secretion pathways. Within each category, proteins were ranked by their log2 fold change (log2FC) from highest to lowest abundance (Figure 2). RLKs and RLPs were enriched in the leaf apoplast following flg22 treatment, with some among the most abundant proteins (Figure S5). IMPAIRED OOMYCETE SUSCEPTIBILITY1 (IOS1) and STRESS INDUCED FACTOR 2 (SIF2) were among the most abundant in the RLK/RLP category. Immune receptor MALE DISCOVERER 1‐INTERACTING RECEPTOR‐LIKE KINASE 2 (MIK2), which recognizes the conserved signature motif of SERINE‐RICH ENDOGENOUS PEPTIDEs (SCOOPs) from plants or fungi to elicit immunity, was also found in the enriched profile (Hou et al., 2021). Other immune‐associated RLKs like RLK902 and several CYSTEINE‐RICH RECEPTOR‐LIKE PROTEIN KINASES (CRKs) were also enriched (Gao et al., 2024). A considerable number of redox‐related proteins, such as PEROXIDASES (PERs) and GLUTATHIONE‐S‐TRANSFERASES (GSTFs) were prominent. Several hydrolytic enzymes were identified in the apoplast during flg22‐induced PTI in Arabidopsis. Enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, including chitinase family proteins (At1g02360), and BETA‐HEXOSAMINIDASE 3(HEXO3), were enriched. Subtilisin‐like protease SBT3.3 and glucan ENDO‐1,3‐β‐GLUCOSIDASE (At2g27500) were also identified, along with related beta‐glucosidases. Enzymes involved in cell wall modifications, such as pectin methyl‐esterases (PMEs) and xyloglucan endotransglucosylases, were present in the enriched profile. The EARLY ARABIDOPSIS ALUMINUM INDUCED 1(EARLI1) protein was enriched by flg22 treatment. EARLI1 is a lipid transfer protein‐like protein that plays a crucial role in mediating systemic defense mechanisms, specifically systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and induced systemic resistance (Vlot et al., 2021).

Figure 2.

Pattern‐triggered immunity‐enriched proteins ranked by functional groups and relative to transcriptome profiles.

The heatmap presents flg22‐enriched protein abundances (red scale) and corresponding transcriptome profiles (blue‐yellow scale) at 0‐, 1‐, 2‐, 3‐, 5‐, 9‐, and 18‐h post‐flg22 treatment relative to mock. Transcriptome data were obtained from Hillmer et al. (2017) (GEO: GSE78735). Proteins with predicted signal peptides (SignalP 6.0, likelihood ≥0.9) are denoted with ‘+’; those without are noted with ‘−’. Functional groups include RLKs/RLPs, redox‐associated proteins, hydrolytic enzymes, peptides, and extracellular vesicle‐associated proteins.

To evaluate the role of highly enriched proteins in PTI and disease susceptibility, bacterial growth assays were conducted on leaves mock treated or treated with flg22 16 h before infection. We tested homozygous T‐DNA insertion lines for six RLKs, comprising IOS1 and five CRKs as well as six apoplastic proteases (Figure S4; Table S2). Pre‐treatment with flg22 conferred strong protection across Col‐0 and all T‐DNA lines, resulting in more than a 3 log10 fold reduction in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 populations at 1‐day post‐infection (dpi) compared to mock‐treated controls. However, no significant differences in bacterial populations were observed between any of the mutants and Col‐0 wild‐type plants under either treatment condition tested.

Notably, in the flg22‐enriched profile, three proteins associated with vesicle trafficking were identified as significantly enriched under PTI conditions. The enriched proteins include Syntaxin of Plants‐122 (SYP122), a Qa‐SNARE which functions in vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane; peptidyl‐prolyl cis‐trans isomerase FKBP15‐1 (FKBP15‐1), which may contribute to protein folding within vesicles; and TET8, associated with exosome EV structural integrity (Boavida et al., 2013; Rubiato et al., 2022; Wang, Sun, et al., 2020; Wang, Wang, & Wang, 2020).

To better understand to what degree transcriptional regulation relates to protein abundance, we integrated our proteomic data with a published Arabidopsis transcriptomics time course from Hillmer et al. (2017). The transcriptomic heatmap illustrates how gene expression changes over time, providing insights into the continuity or discontinuity between transcription and protein accumulation in response to flg22 treatment. There are 22 RLK/RLP identified in the enriched profile, and 10 of them displayed rapid upregulation in the first hours; then the expression level gradually decreased. Several redox‐related proteins and hydrolytic enzymes, such as peroxidases (PER21, PER52, and PER71) and Glutathione S‐Transferase (GSTF6 and GSTF7), showed sustained transcriptional upregulation at a relatively later time point. Overall, protein abundance ratios did not consistently align with transcriptomic trends. Although the proteome was profiled at 16‐h post‐flg22 treatment, several proteins that were highly enriched at the protein level showed little or no corresponding transcriptional upregulation at this time point. Unlike the distinct functional clustering observed in the enriched protein profile by flg22 treatment, proteins with decreased apoplastic abundance did not exhibit clear patterns linked to PTI or disease response functions. Based on molecular function Gene Ontology (GO) analysis, these proteins were categorized into 10 functional groups (Figure S3). We observed some genes displaying high transcript levels post‐flg22 treatment despite their decreased protein abundance in the apoplast, indicating some discontinuity between transcript and protein abundances.

SignalP 6.0 (Teufel et al., 2022) analysis revealed 65% (70/108) of significantly enriched proteins under flg22 treatment have canonical signal peptides consistent with the classical secretory pathway, while 35% (38/108) lacked these motifs, indicating diverse secretion strategies. ApoplastP (Sperschneider et al., 2018) was used to predict the subcellular localization of proteins and identified 34 out of the 108 significantly enriched proteins as apoplastic (Table S3).

Recovered peptides of RLKs are heavily biased to ectodomains

Many RLK transmembrane proteins were enriched in the apoplastic proteome following flg22 treatment (Figure 2; Figure S5). This is unexpected as they would not be expected to be present in the free extracellular fraction. We analyzed the topological distribution of peptides detected from 19 RLKs enriched under PTI conditions and found a clear bias toward peptides mapping to their ectodomains, and very few peptides were captured close to the cytoplasmic regions (Figure 3). This pattern suggests that portions of these RLKs are released into the apoplast during PTI, possibly through proteolytic processes such as ectodomain shedding. Additionally, the majority of peptides were mapped to the signature domain of a certain group of RLKs. For instance, all the mapped extracellular peptides located at the malectin motif of IOS1 and SIF2. Mapping of peptides on enriched CRKs revealed a consistent pattern of topological distribution across the Gnk2 homolog domain, with all peptides aligning within functional regions of the Gnk2 domain. Gnk2 homologs contain the domain of unknown function 26 (DUF26), characterized by a cysteine‐rich C‐X8‐C‐X2‐C motif (Miyakawa et al., 2014). Proteolysis is a key mechanism in plant immunity, regulating the activation, degradation, and signaling of immune proteins, including the cleavage and release of RLK ectodomains (Yu et al., 2025). The extracellular bias aligns with the apoplast‐specific protein collection procedure. The limited peptide coverage in cytoplasmic regions further emphasizes the specificity of the apoplast isolation protocol indicating the purity of apoplastic protein isolation.

Figure 3.

Peptide distribution analysis of receptor‐like kinases (RLKs) in flg22‐enriched proteins.

The schematic illustrates the mapping of identified peptides to pattern‐triggered immunity‐enriched RLKs, represented as short black bars above the protein domain structures. Each RLK is depicted with its extracellular region (green background) and the cytoplasmic kinase region (pink background) on the right. The visualization reveals the majority of detected peptides are localized to the extracellular regions of the RLKs, while the cytoplasmic regions, particularly the kinase domains, showed notably fewer peptide matches.

GO analysis of the enriched protein profile under the flg22 treatment

We performed GO analyses of the 108 significantly enriched proteins in flg22 treatment with TAIR GO Term Enrichment platform and presented the top 15 enriched GO categories. The GO analysis identified significant enrichment of multiple biological processes in flg22‐enriched proteins (Figure 4a). Processes with the highest gene number include response to stimulus and response to stress, suggesting that many enriched proteins are involved in both general and specific stress responses. More specific processes, such as response to biotic stimulus, defense response to Gram‐negative bacterium, and defense response to fungus, highlight these proteins' roles in responding to the presence of pathogens. Specific processes such as response to oxygen levels and response to oxidative stress are also enriched, suggesting that these proteins may play roles in ROS production, which is commonly associated with plant immune responses signaling (Torres et al., 2006). Notably, highly representative pathway with higher fold enrichment like defense response to Gram‐negative bacterium align with the expected response to the bacterial elicitor flg22.

Figure 4.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of flg22‐enriched and flg22‐decreased abundance protein profile.

The dot plot represents the top 15 significantly enriched GO terms of (a) 108 significantly enriched proteins and (b) 255 significantly decreased proteins categorized into cellular component, molecular function, and biological process. The x‐axis represents the gene number of each category, while the size of the circles indicates fold enrichment. The color intensity of the circles corresponds to the statistical significance of enrichment (−log10 adjusted P‐value). GO terms are arranged on the y‐axis, grouped by their respective ontologies (cellular component, molecular function, and biological process).

The molecular function analysis for flg22‐enriched proteins revealed significant enrichment in various catalytic and kinase activities. Nearly 25% of the proteins identified in the GO analysis were annotated for catalytic activity. The enrichment of oxidoreductase activity, including peroxidase and lactoperoxidase functions, suggests roles associated with redox reactions and potential oxidative stress responses. Proteins with kinase and transferase activities, particularly those transferring phosphorus‐containing groups, were also prominent. Specifically, protein kinase activity and protein serine/threonine kinase activity were enriched, indicating involvement in phosphorylation cascades.

Consistent with protein isolation from the apoplast, the cellular component analysis for flg22‐enriched proteins revealed significant enrichment in regions associated with the cell periphery, extracellular region, and membrane. Nearly 15% of the proteins identified in the GO analysis were localized to the cell periphery, suggesting a strong role in cell surface interactions. Notably, vesicles and components associated with the secretory pathway were also present in the dataset.

In contrast to the flg22‐enriched proteins, which exhibited distinct functional categories related to PTI and defense responses, the proteins with lower abundance did not display clear patterns linked to these functions (Figure 4b). However, the GO analysis revealed that these lower abundance proteins were involved in a wide range of cellular processes, including metabolism and cellular turnover. The cellular component analysis of 255 depleted abundance proteins showed their overall localization in the apoplast, with involvement in protein secretion and cell periphery, albeit with a smaller fold enrichment than the enriched proteins. The detection of depleted proteins annotated with secretory pathway‐related GO terms suggests that these proteins are secreted into the apoplast, despite showing reduced abundance under mock‐treated conditions. GO annotations indicated the presence of proteins with intracellular functions. However, as proposed by Karimi et al. (2025), this may reflect either mis‐localization in Araport or genuine dual localization of proteins that function in both intracellular and extracellular compartments.

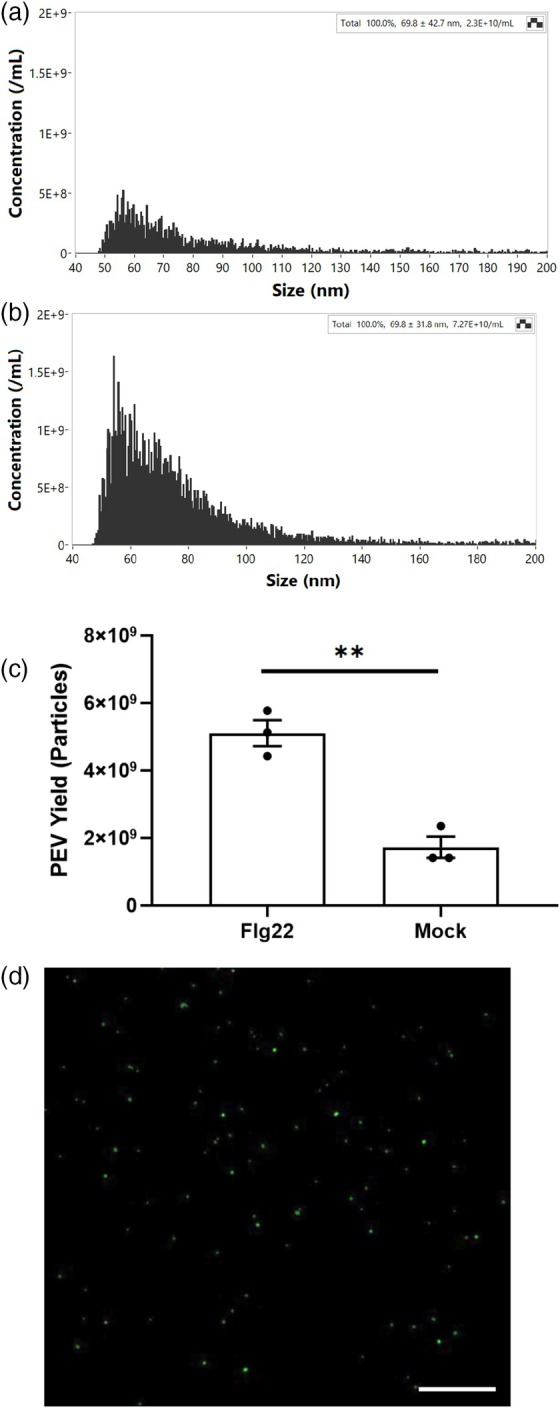

PTI is associated with increased numbers of EVs in leaf apoplast

Several studies have reported the enrichment of P‐EVs during pathogen infection (Cai et al., 2019; Rutter & Innes, 2017). In our dataset, we observed significantly enriched proteins associated with vesicular export, including SYP122, TET8, and FKBP15‐1. SYP122 and TET8 show increased changes of 8.0‐ and 5.2‐fold, respectively, relative to the mock condition. Notably, TET8 is an exosome marker involved in exosome stability (Cai et al., 2019; Liu, Hou, et al., 2024; Liu, Jackson, et al., 2024). Exosomes are one of several classes of EVs with a size typically between 50 and 150 nm in diameter and have been associated with the cross‐kingdom delivery of small RNA for RNAi. We isolated plant EVs using ultracentrifugation and quantified them using Nano‐flow cytometry. The analysis of EV in both flg22‐treated and mock samples reveals that the median size of EVs in flg22‐treated samples is 67.8 nm, compared to 70.7 nm in mock samples (Figure 5a,b). This similarity in size indicates no significant difference between the two conditions, suggesting that the majority of these vesicles fall within the size range characteristic of plant exosomes (Cai et al., 2019; Rutter & Innes, 2017). Exosomes were found at 5.1 × 109 particles ml−1 in the flg22‐treated samples, nearly three times higher than the 1.7 × 109 particles ml−1 observed in the mock samples (Figure 5c). This increased concentration in the flg22 condition aligns well with the 5‐fold higher protein levels identified in the flg22/mock proteomics analysis. The staining of the AWF‐derived EVs with the lipid dye, CFSE, highlighted the shape and size characteristic of exosomes (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Plant extracellular vesicles (P‐EVs) are enriched in flg22 treatment.

(a) Size distribution of mock‐P‐EVs identified by nano‐flow cytometry (NFC).

(b) Size distribution of flg22‐P‐EVs identified by NFC.

(c) Comparison of P‐EV production between the flg22 and mock groups, showing a significant increase in P‐EV production in the flg22 group. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test to determine P‐EV yield differences between groups with **P < 0.01.

(d) Confocal images of CFSE‐stained P‐EV from mock samples. Scale bar = 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

GO analysis of the PTI‐enriched apoplastic proteome revealed significant enrichment in predicted biological processes such as defense responses to Gram‐negative bacteria and oxidative stress (Figure 4a). The molecular functions enriched in flg22‐treated samples included both kinase and oxidoreductase activities, consistent with known roles of PRRs and redox regulation in plant defense. The cellular component GO terms, as expected, highlighted the extracellular localization of both enriched and depleted proteins, including associations with the cell wall, plasma membrane, secretory vesicles, and extracellular regions. A smaller subset of proteins was also found with predicted intracellular locations such as the nucleus, intracellular vesicles, or associated with the plasma membrane. While GO annotations indicated the presence of proteins with intracellular functions, this may reflect either mis‐annotations or genuine dual localization of proteins functioning in both intracellular and extracellular compartments (Karimi et al., 2025). Unlike the PTI‐enriched proteins, which were prominently associated with defense signaling and oxidative stress responses, the PTI‐depleted proteins displayed functions more broadly related to cellular homeostasis and general secretory mechanisms (Figure 4b). This may be due to reduced cytoplasmic protein leakage in flg22‐treated samples during the collection process (Figure S1) or may reflect an overall shift in molecular function. Notably, more than 18% of depleted proteins were associated with functions related to cell organization and biogenesis, including BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1 (BRI1), indicating the stabilization of BR signaling under naïve conditions; this can potentially be a consequence of the growth‐defense trade‐off (Huot et al., 2014).

We defined five functional categories of apoplastic proteins enriched during flg22‐triggered PTI, including RLK/RLPs, redox‐associated proteins, hydrolytic enzymes, peptides, and EV associated proteins (Figure 2). Among the RLKs, IOS1 and SIF2 were highly enriched with log2FC of 6.64 and 4.63. These two malectin‐domain RLKs have both been observed previously to play roles in PTI signaling upon FLS2‐mediated flg22 recognition. IOS1, a malectin‐like leucine‐rich repeat RLK, modulates Arabidopsis immunity by forming complexes with the FLS2 and BAK1 co‐receptor to amplify pathogen recognition and defense responses. Loss‐of‐function mutants of IOS1 demonstrated decreased PTI‐mediated stomatal immunity (Yeh et al., 2016). However, when high concentrations of P. syringae are directly infiltrated into leaf tissue, no significant differences are observed compared to wild‐type plants (Figure S4). Similarly, SIF2 also interacts with FLS2 and BAK1 and has been implicated in early flg22‐triggered immune signaling, contributing to downstream defense activation (Chan et al., 2020). Another RLK‐MIK2 functions as a dual‐purpose immune receptor in Arabidopsis, recognizing both endogenous SCOOPs as phytocytokines and pathogen‐derived SCOOP‐like motifs from microbes like Fusarium spp. (Hou et al., 2021). Its activation requires association with the co‐receptor BAK1 to initiate immune signaling. The presence of MIK2 in PTI tissues aligns with its role in detecting conserved microbial patterns and plant immune peptides.

The peptide recovery analysis of RLKs demonstrated a marked bias toward the receptor extracellular regions, with minimal peptides detected in their cytoplasmic regions (Figure 3). The limited recovery of cytoplasmic peptides further aligns with the low levels of cytoplasmic contamination in the AWF, emphasizing the effectiveness of the apoplast isolation protocol as described by Lovelace et al. (2022). While technical artifacts (e.g., isolation‐induced fragmentation) cannot be fully excluded, our observation aligns with emerging models of receptor dynamics in plant immunity.

Recent studies demonstrate that RLK ectodomain shedding plays roles in immune signaling. BAK1, a co‐receptor for FLS2, undergoes calcium‐dependent ectodomain cleavage during PTI, which modulates immune signaling (Zhou et al., 2019). CHITIN ELICITOR KINASE 1 (CERK1), a LysM motif‐containing RLK in Arabidopsis, functions as a receptor for chitin oligomers, initiating plant defense responses against fungi (Liu et al., 2012). The ectodomain and transmembrane region of CERK1 are sufficient to suppress cell death, suggesting that ectodomain shedding prevents deregulated immune activation via a chitin‐independent pathway (Petutschnig et al., 2014). This suggested the signaling role of RLK ectodomains, functioning independently of their intracellular domains, similar to receptor tyrosine kinases in mammals (Merilahti & Elenius, 2019). Analysis of ectodomain shedding revealed that malectin domain‐containing RLKs, such as IOS1 and SIF2, have most peptides mapped to their malectin domains. Additionally, the majority of peptides from CRKs are mapped to the Gnk2‐homologous region, a domain originally identified as a seed storage protein in gymnosperms with antifungal activity and characterized by a plant‐specific cysteine‐rich motif DUF26 (Miyakawa et al., 2014). Recent study in the proteome of agroinfiltrated Nicotiana benthamiana reported ectodomain shedding events from a wide range of RLKs (Zheng et al., 2024). The proteolytic generation of cytosolic proteoforms has been observed in other RLKs such as Xa21 (Park & Ronald, 2012), TMK1 (Gu et al., 2022), and FERONIA (Chen et al., 2024), indicating the cleavage of RLKs. These observations further suggest the potential for specific ectodomain shedding observations across a wide range of RLK groups during PTI, indicating a conserved regulatory mechanism in plant immune signaling.

A comparative analysis of transcriptome and proteome profiles revealed a complex relationship between transcriptional regulation and endpoint protein abundance during flg22‐triggered PTI (Figure 2). Several high‐abundant proteins displayed consistent trends between transcript levels and protein accumulation over the time course. For example, IOS1 and SIF2, both RLKs, exhibited rapid transcriptional upregulation within the first few hours of flg22 treatment. This aligns with their role in early pathogen recognition and activation of downstream signaling pathways (Bigeard et al., 2015). Similarly, peroxidases such as PER15 (Peroxidase 15) showed a strong correlation between transcript and protein levels, consistent with its involvement in ROS management and oxidative stress responses during PTI. However, other high‐abundance proteins demonstrated protein enrichment despite declining transcript levels over time.

CRKs, another set of RLKs, have distinct patterns of expression despite their role in response to flg22 perception. While research has shown that CRK28/CRK29 are synthesized upon pathogen perception, associate with the FLS2 complex, and coordinately enhance plant immune responses during the early PTI phase (Yadeta et al., 2017), other CRKs exhibit distinct temporal patterns of protein accumulation in later PTI stages. For instance, CRK11 and CRK12 remained abundant in the apoplast even as their transcript levels decreased after the initial hours of flg22 exposure. On the other hand, CRK13 exhibited decreased transcript levels over time but maintained a high expression pattern and protein abundance during late PTI, suggesting its crucial role in enhanced resistance to the bacterial pathogen P. syringae (Acharya et al., 2007). We observed no significant differences in P. syringae susceptibility between six individual homozygous CRK T‐DNA mutants and wild‐type plants under both naive and PTI conditions (Figure S4). This is consistent with evidence for functional redundancy among CRKs in Arabidopsis immune responses (Yeh et al., 2015). Alternatively, it is possible that CRKs play a more pronounced role in stomatal immunity, which may not be fully captured under our tested conditions.

The enrichment of various hydrolytic enzymes in the apoplast in response to flg22 treatment suggested a multifaceted response to PTI. Several enzymes involved in plant cell wall modification were found to be enriched including PMEs (PME3, PME17), xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH23), and β‐1,3‐glucanases (At2g27500 and At5g56590) (Bethke et al., 2014; Perrot et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). These enzymes collectively suggest that the plant is actively remodeling its cell wall during PTI, possibly to enhance its barrier function against potential pathogens. Several hydrolytic enzymes capable of N‐glycosylation of immune receptors and degrading pathogen‐associated targets (especially fungal cell wall) were enriched, such as HEXO3 and endochitinases (At2g43620 and At1g02360) (Fiorin et al., 2018; Liebminger et al., 2011). These enzymes suggest that the plant is actively degrading potential pathogen‐derived molecules, which could both weaken a broad spectrum of pathogens and generate additional immune‐stimulating signals. Various proteases and protein‐modifying enzymes were also enriched. Metalloendoproteinases (2‐MMP and 3‐MMP) and subtilisin‐like protease (SBT3.3) may be involved in processing defense‐related proteins within the extracellular matrix or degrading pathogen‐derived proteins (Flinn, 2008; Ramírez et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2017). Plant aspartyl proteases (MMG4.12 and At3g02740) and cathepsin B‐like protease 2 (CATHB2) were also found. Aspartyl proteases contribute to immune signaling by generating bioactive peptides that activate salicylic acid (SA)‐dependent defense signaling and SAR, while cathepsin B‐like protease 2 (CATHB2) enhances pathogen resistance through direct cleavage of microbial proteins and modulation of ROS signaling to amplify defense signaling that is crucial for both PTI and program cell death (Figueiredo et al., 2021; McLellan et al., 2009). The presence of these proteases suggests active protein processing and turnover, which could be important for the homeostasis of defense signaling molecules and limiting pathogen fitness. Other metabolic enzymes, such as NUDT6 and NUDT7, members of the nudix hydrolase family, were enriched by flg22. They play crucial roles in regulating plant immunity and stress responses by maintaining the redox balance of NADH and acting as ADP‐ribose pyrophosphatases (Fonseca & Dong, 2014). The coordinated action of these hydrolytic enzymes with various types of substrates likely contributes to the rapid and effective immune response against potential pathogens, such as protein turnover in immune receptors or the production of ROS, highlighting the sophisticated defense mechanisms employed in pathogen recognition and immune activation.

The observation of pathogenesis‐related 1 (PR1) protein enrichment in the flg22 treatment profile, with a notable 4.67‐fold change, strongly aligns with key findings in induced PTI. Upon flg22 treatment, plants exhibit increased PR1 expression as part of their PTI response (Djamei et al., 2007). PR1 is also a well‐established marker for SAregulated plant immunity, and its secretion is critical for activating SAR (Spoel & Dong, 2024). PR1 serves as a precursor for the CAPE1 peptide, which is released upon proteolytic cleavage and subsequently amplifies immune signaling by activating both SA and jasmonic acid pathways, contributing to SAR (Chen et al., 2014). Recent findings further reveal that plants enhance PR1's efficacy through synergistic interactions with other PR proteins, such as PR5 and PR14, to strengthen immune responses (Han & Schneiter, 2024). The significant enrichment of PR1 protein abundance observed in this study confirms its responsiveness to PTI triggered by flg22 treatment and further demonstrates the effectiveness of the experimental conditions in inducing PTI response.

For lower abundant proteins by flg22 treatment, inconsistencies with transcript levels were even more pronounced. Many of these proteins, such as certain housekeeping enzymes and stress‐related factors, exhibited little to no transcriptional change over the time course (Figure S3). Their reduced abundance in the apoplast may result from active degradation, inhibited secretion, or preferential retention in intracellular compartments. Unlike high‐abundant proteins, these low‐abundant factors were associated with less PTI‐relevant processes, further indicating that their depletion may reflect cellular reorganization rather than active participation in immune responses. The observed variation between the protein enrichment profiles at the 16‐h time point and the time course transcriptomic profiles suggests the involvement of post‐transcriptional regulatory mechanisms, such as mRNA stabilization or reduced protein degradation. Protein turnover rates and translational delays may contribute to transient mismatches between transcript and protein abundance that could either resolve or become more pronounced over time. To more accurately capture system‐wide relationships between transcript and protein levels, future incorporation of time course proteomic sampling parallel to transcriptome profiling would be beneficial.

Several EVs‐associated proteins exhibited a significant increase in flg22‐treated apoplast samples. In particular, TET8, a well‐established exosome marker, was enriched fourfold compared to mock‐treated samples (Figure 2). Cai et al. (2018) previously identified TET8 as a core component of exosomes involved in stress responses and pathogen defense as mediators of interkingdom RNAi. Additionally, the concentration of EVs particles in flg22‐treated samples was approximately three times higher than in mock‐treated samples (Figure 5c). This increase in EVs production suggests enhanced trafficking of defense molecules and signaling factors to the apoplast. The enrichment of Syntaxin‐122 (SYP122), a SNARE protein involved in vesicle fusion, also supports the idea that vesicle‐mediated transport is a key component of the immune response (Waghmare et al., 2018). Although approximately 18% of proteins in the Arabidopsis genome are predicted to be secreted, secretome studies consistently report that 40–70% of identified secreted proteins lack a signal peptide (Alexandersson et al., 2013).

ApoplastP only identified 34 out of the 108 significantly enriched proteins as apoplastic proteins (Table S3). However, several inconsistencies emerged in the predictions. For instance, known extracellular hydrolytic enzymes such as At1g02360 and At2g27500 were classified as non‐apoplastic. These discrepancies reflect the reported limitations of ApoplastP in accurately detecting apoplastic proteins in Arabidopsis leaves, with prediction accuracies of 51.2% for SignalP‐negative and 70.4% for SignalP‐positive proteins (Sperschneider et al., 2018). The absence of signal peptides, as predicted by SignalP, in a subset of PTI‐enriched apoplastic proteins suggests that their secretion may occur via exosome‐mediated trafficking. This finding aligns with studies demonstrating that P‐EVs selectively package leaderless proteins involved in defense responses, thereby bypassing the classical endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi secretion pathway (Rutter & Innes, 2017). These findings highlight EVs as essential mediators of PTI, potentially promoting targeted secretion of defense components and amplifying immune signaling during pathogen recognition. To further clarify the specific roles of exosomes versus other secreted proteins, it would be beneficial to independently analyze exosome proteomic profiles in late PTI.

Our study presents a comprehensive resource of the Arabidopsis leaf apoplastic proteome during the later stages of flg22‐induced PTI. We identified 108 significantly enriched proteins, grouped into functional categories such as RLKs and RLPs, redox‐related proteins, hydrolytic enzymes, small peptides, and EV‐associated proteins. This dataset illustrates the complexity of the apoplastic immune response, with proteins contributing to different phases of PTI activation, defense reinforcement, and signaling. Integration of proteomic and transcriptomic data revealed that gene expression levels do not consistently predict protein abundance at late PTI stages, emphasizing that sustained protein accumulation is a key immune output. An analysis of 19 enriched RLKs revealed a widespread distribution of recovered peptides from their extracellular domains. This suggests that ectodomain shedding or release into the apoplast may occur during PTI, potentially allowing these domains to function independently or act as immune signals. Our findings support recent studies and offer new insights into the biological processes underlying immune signaling. Additionally, we observed enrichment of the exosome marker TET8 and a threefold increase in exosome particles, supporting the role of exosome‐mediated intercellular communication as an important feature of the apoplastic immune response. Together, this resource provides a detailed snapshot of proteomic changes in the apoplast during late PTI and offers a valuable foundation for future investigations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant tissue preparation

Arabidopsis thaliana Col‐0 seeds suspended in sterile 0.1% agarose were sown in SunGrow 3B Professional potting mix and stratified in darkness for 2 days at 4°C before being grown in a growth chamber (Conviron A1000) with 14‐h light (70 μmol m−2 sec−1) at 22°C. After 4 weeks, plants were transferred to a growth room maintained under a 12‐h light/12‐h dark cycle for acclimatization. At 4.5 weeks, plants were treated for 16 h to induce PTI. Treatments were applied using a 1 ml blunt‐end syringe to 4–5 fully expanded leaves per plant. The treatments consisted of 1 μM flg22 peptide to induce PTI and 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a mock control treatment. The solutions were carefully infiltrated into the abaxial side of the selected leaves, and plants were maintained under the same growth room conditions during the 16‐h treatment period.

Bacterial infection assay

4.5‐week‐old Col‐0 plants (Table S2) were inoculated with P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 suspended in 0.25 mM MgCl2 at 5 × 107 colony‐forming units (CFU) ml−1, prepared according to Lovelace et al. (2018). Fully expanded leaves received pre‐treatment via syringe infiltration with either 1 μM flg22 or 0.1% (v/v) DMSO (mock control) 16 h before infection. Bacterial quantification was performed at 1‐day post‐infection (1 dpi) following Lovelace et al. (2022). Briefly, four 4‐mm‐diameter leaf discs (∼0.5 cm2 total area) per treatment were collected using a biopsy punch. Tissues were homogenized in 0.1 ml of 0.25 mM MgCl2 for 2 min using a SpeedMill Plus homogenizer (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany), with subsequent bacterial enumeration via serial dilution spot plating. For each genotype and treatment, four plants were used per replicate, and the experiment was independently repeated twice (n = 8). Bacterial titers were expressed as mean log10 (cfu cm−2) ± standard error (SE). Statistical comparisons between mutants and Col‐0 wild type were performed using a paired two‐tailed Student's t‐test, with significance defined as P < 0.05.

Extraction of apoplastic washing fluid and cytoplasmic contamination measurement

AWF was crude extracted using vacuum infiltration as described by Lovelace et al. (2022). 130–150 A. thaliana leaves were cut and placed into a 500 ml beaker filled with iced‐cold distilled water to the top. Repeated cycles of vacuum at 95 kPa for 2 min followed by slow release of pressure were applied until the leaves were fully infiltrated. Excess water was blotted from the plant tissue before rolled into Saran wrap which were placed into 50 ml conical tubes. Tubes were centrifuged at 1000× g for 10 min at 4°C, and the fractions were pooled and stored at −80°C. Cytoplasmic contamination in our AWF samples was examined by comparisons of cytosolic marker G6PDH activity in sampled AWF extracts to the total leaf extracts using a standard kit (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Leaves were homogenized at 4°C. G6PDH activity was assayed spectrophotometrically every 5 min at 37°C where each reaction contained 50 μl of AWF and the activity was calculated according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Sample preparation and mass spectrometry analysis—LC–MS/MS

Samples were filtered through a 3 kDa Amicon spin filter to approximately 50 μl. The retentate was collected via reverse centrifugation, washed with 50 μl of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, and combined. Total protein content was measured using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and quantified at 550 nm based on a BSA standard curve (Table S1).

For digestion, 100 μg of protein from each sample was prepared with the EasyPep Mini MS Sample Prep Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After reduction and alkylation at 95°C, samples were digested with Trypsin/LysC (0.2 μg μl−1) at 37°C for 2 h. Digestion was stopped, contaminants removed using peptide cleanup columns, and the eluate was dried and resuspended in 3% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid. Peptide concentration was measured at 205 nm on a NanoDrop, calculated using an extinction coefficient (Scopes, 1974). Reverse‐phase chromatography was performed with water +0.1% formic acid and 80% acetonitrile +0.1% formic acid. A total of 1 μg of peptides was enriched using a PepMap Neo C18 trap‐column, followed by separation on a Vanquish Neo system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a C18 nanospray column at 45°C using a 90 min gradient at a flow rate of 300 nl min−1: 1–6%B over 3 min followed by 6–35%B over 70 min, 35–45%B over 5 min ending in 12 min of washing at 500 nl min−1, 99%B. Peptides were eluted directly into an Orbitrap Eclipse mass spectrometer with a Nanospray Flex ion source and analyzed in Data Dependent Acquisition mode. MS spectra were collected over m/z 375–2000 in positive mode, with ions of charge state +2 or higher selected for MS/MS. Dynamic exclusion was set to 1 MS/MS per m/z with a 60 sec exclusion. MS detection was performed in FT mode at 240 000 resolution, and MS/MS in ion trap mode with HCD collision energy at 30%.

Data analysis and statistics

Data processing was conducted in Proteome Discoverer (PD) 3.0 (Thermo Scientific). A precursor detector node (S/N = 1.5) was used to identify additional precursors within the isolation window for chimeric spectra. Sequest HT searched spectra with methionine oxidation as a dynamic modification and cysteine carbamidomethylating as a fixed modification. An intensity‐based rescoring (INFERYS node) using deep learning predicted fragment ion intensities (Zolg et al., 2021). Data were matched against the A. thaliana UniProt proteome (UP000006548) and cRAP contaminants. Searches used a fragment ion tolerance of 0.60 Da and parent ion tolerance of 10 PPM. Peptide spectrum matches were validated using Percolator with a false discovery rate (FDR) ≤1%, and proteins were required to have at least one unique peptide for identification. Total abundance values were normalized across all samples to equalize the total protein abundance between experimental runs. For normalization, the summed abundance of all proteins was calculated for each sample, and the maximum summed abundance across all samples was determined. A sample‐specific normalization factor was derived by dividing the maximum summed abundance by the sample's total abundance. Protein abundances in each sample were then normalized by dividing their raw values by this factor. Normalized abundances were log2‐transformed for downstream analysis. Log2 fold changes (FC) were calculated to identify proteins with higher (log2 FC ≥1) or lower (log2 FC ≤−1) abundance in flg22‐treated samples compared to mock controls. Statistical significance was assessed using two‐sample t‐tests (P < 0.05).

Protein sequences of the 108 significantly enriched proteins were used as input for SignalP 6.0 and ApoplastP to assess secretion potential and apoplastic localization, respectively. SignalP 6.0 (Teufel et al., 2022) was used to predict N‐terminal signal peptides associated with classical secretion, using the web server hosted by the Technical University of Denmark (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/service.php?SignalP‐6.0) with the organism group set to ‘Eukarya’ and default parameters. In parallel, ApoplastP (Sperschneider et al., 2018), a machine learning‐based tool for predicting apoplastic localization—including proteins secreted via unconventional routes—was applied using its web server (https://apoplastp.csiro.au/) under default settings. ApoplastP output included binary localization classification (‘apoplastic’ or ‘non‐apoplastic’) along with probability scores for each prediction.

GO analysis

To identify functional categories enriched in the proteomic data, both significantly enriched proteins and significantly depleted proteins were analyzed using the GO analysis. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) GO Term Enrichment tool version 2. The analysis was conducted using the TAIR10 genome as the reference dataset to determine over‐ and under‐representation of specific biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. Enriched GO terms were considered significant based on a Bonferroni‐corrected P‐value cutoff of <0.05. The results provided insight into functional trends within the identified apoplastic proteome, including processes associated with plant defense and signal transduction.

Transcriptomics analysis

To investigate the transcriptional profiles of A. thaliana proteins identified as significantly enriched or significantly lower abundant in response to flg22 treatment, Tag‐Seq data for wild‐type Col‐0 plants were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE78735) as described by Hillmer et al. (2017). This dataset comprised transcriptome profiles collected at seven time points post flg22 treatment (0‐, 1‐, 2‐, 3‐, 5‐, 9‐, and 18‐h post‐infiltration) with three biological replicates per time point. For each gene, read counts from the three biological replicates were averaged at each time point, normalized to the 0‐h time point by calculating fold changes, and log10‐transformed. These processed values were visualized as a heatmap using the pheatmap function from the pheatmap package (version 1.0.12) in R.

Topological distribution analysis

To analyze the topological distribution of RLKs in the high‐abundance protein profile in response to flg22/mock treatment, peptides identified via PD 3.0 were mapped to specific domains or positions within each RLK. Protein domain annotations for the RLKs were obtained from UniProt. Identified peptides corresponding to RLKs were selected and extracted, and their positions were aligned to the respective RLK sequences. This mapping allowed for the determination of peptide coverage within specific protein domains, including extracellular, transmembrane, and intracellular regions.

P‐EV isolation and quantification

The P‐EVs isolation protocol was modified from previous studies (Huang et al., 2021). Briefly, the crude AWF was centrifuged for 30 min at 4°C at 2000× g to remove large cell debris, and then, the supernatant was further centrifuged at 10 000× g for 30 min at 4°C to remove large insoluble particles. The supernatant (the clean AWF) was then collected and further processed by ultracentrifugation at 100 000× g for 1 h at 4°C (Optima™ TLX Ultracentrifuge, Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, USA) to purify and concentrate P‐EVs. Each P‐EV pellet was gently resuspended in 50 μl of 0.22 nm‐filtered PBS, and all samples were aliquoted and stored at −80°C until further use. Nano‐flow cytometry (NanoFCM, Xiamen, China) was used to analyze P‐EVs isolated from both flg22 and mock samples, following the manufacturer's instructions. For each sample, a 0.2 μl aliquot of P‐EVs was diluted in 50 μl of filtered PBS (1:250 dilution) for analysis. Particle concentration and size distribution were measured in triplicates. To evaluate differences in P‐EVs origin between the flg22 and mock groups, yield was calculated as the number of EVs per gram of leaf tissue used for AWF collection. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t‐test to determine P‐EV yield differences between groups (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, NS: not significant).

P‐EVs from mock treatment samples were stained with CFSE dye and examined under a confocal microscope. The fluorescence signals were observed by using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal laser‐scanning microscope. FITC filter (Excitation: 460–500 nm; Emission: 510–560 nm) (Zeiss, Oberk, Germany) was used to detect the GFP signal (Excitation: 530–560 nm) (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Images were generated and merged using The Zen 2.3 imaging software.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H‐CC, YY, and BHK designed the research; H‐CC, CJN, FK, and YZ conducted experiments; H‐CC, GD, CJN, and YZ analyzed the data; H‐CC, FK, YZ, and BHK wrote the paper. All listed authors reviewed and approved draft and final versions of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Cytoplasmic contamination detection of apoplastic washing fluid.

Figure S2. Protein concentration of AWF samples.

Figure S3. PTI‐depleted apoplastic proteins ranked by functional groups and relative to transcriptome profiles.

Figure S4. Disease resistance screening against Pseudomonas syringae in selected mutants of flg22‐enriched proteins.

Figure S5. Volcano plot of total 3667 detected proteins with highlight of 22 enriched RLKs/RLPs.

Table S1. The protein concentration of each AWF samples before processing.

Table S2. T‐DNA and wildtype Arabidopsis lines for diseases susceptibility tests.

Table S3. Prediction of SignalP 6.0 and ApoplstP of high enriched proteins.

Data S1. List of total identified proteins, list of high and low abundance proteins by flg22 treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Grant 1844861 to BHK. CJN, LY, and FK were supported by NIH R35GM143067. YZ and YY were supported by startup funds from the University of Georgia (to YY). We thank Su‐Yun Uhm from the Department of Genetics, University of Georgia for assistance of Arabidopsis planting and AWF collection. We acknowledge the use of resources provided by the Colorado State University ARC‐BIO (Research Resource ID: SCR_021758). Data were generated using the Orbitrap Eclipse Mass Spectrometer supported by NSF Grant 2117943. We acknowledge the contribution of ARC‐BIO staff,Dorathea Lee,for sample preparation.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The mass spectrometry proteomics data is deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository (Perez‐Riverol et al., 2025) with the dataset identifier PXD060654 and 10.6019/PXD060654. Details regarding experimental design, sample preparation, and LC–MS/MS parameters are described in the Materials and Methods section of this manuscript. Total identified proteins, significantly high‐abundance proteins by flg22 treatment, and significantly low‐abundance proteins by flg22 treatment are listed in the Data S1.

References

- Acharya, B.R. , Raina, S. , Maqbool, S.B. , Jagadeeswaran, G. , Mosher, S.L. , Appel, H.M. et al. (2007) Overexpression of CRK13, an Arabidopsis cysteine‐rich receptor‐like kinase, results in enhanced resistance to Pseudomonas syringae. The Plant Journal, 50, 488–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, G.K. , Jwa, N.‐S. , Lebrun, M.‐H. , Job, D. & Rakwal, R. (2010) Plant secretome: unlocking secrets of the secreted proteins. Proteomics, 10, 799–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandersson, E. , Ali, A. , Resjö, S. & Andreasson, E. (2013) Plant secretome proteomics. Frontiers in Plant Science, 4, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C. , Wan, Y. , Kim, Y.‐M. , Pasa‐Tolic, L. , Metz, T.O. & Peck, S.C. (2014) Decreased abundance of type III secretion system‐inducing signals in Arabidopsis mkp1 enhances resistance against Pseudomonas syringae . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111, 6846–6851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aung, K. , Jiang, Y. & He, S.Y. (2018) The role of water in plant–microbe interactions. The Plant Journal, 93, 771–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethke, G. , Grundman, R.E. , Sreekanta, S. , Truman, W. , Katagiri, F. & Glazebrook, J. (2014) Arabidopsis PECTIN METHYLESTERASEs contribute to immunity against Pseudomonas syringae . Plant Physiology, 164, 1093–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigeard, J. , Colcombet, J. & Hirt, H. (2015) Signaling mechanisms in pattern‐triggered immunity (PTI). Molecular Plant, 8, 521–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boavida, L.C. , Qin, P. , Broz, M. , Becker, J.D. & McCormick, S. (2013) Arabidopsis tetraspanins are confined to discrete expression domains and cell types in reproductive tissues and form homo‐ and heterodimers when expressed in yeast. Plant Physiology, 163, 696–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller, T. & He, S.Y. (2009) Innate immunity in plants: an arms race between pattern recognition receptors in plants and effectors in microbial pathogens. Science, 324, 742–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borniego, M.L. , Molina, M.C. , Guiamét, J.J. & Martinez, D.E. (2020) Physiological and proteomic changes in the apoplast accompany leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, 1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Q. , He, B. , Weiberg, A. , Buck, A.H. & Jin, H. (2019) Small RNAs and extracellular vesicles: new mechanisms of cross‐species communication and innovative tools for disease control. PLoS Pathogens, 15, e1008090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Q. , Qiao, L. , Wang, M. , He, B. , Lin, F.‐M. , Palmquist, J. et al. (2018) Plants send small RNAs in extracellular vesicles to fungal pathogen to silence virulence genes. Science, 360, 1126–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camejo, D. , Guzmán‐Cedeño, Á. & Moreno, A. (2016) Reactive oxygen species, essential molecules, during plant‐pathogen interactions. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 103, 10–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C. , Panzeri, D. , Okuma, E. , Tõldsepp, K. , Wang, Y.‐Y. , Louh, G.‐Y. et al. (2020) STRESS INDUCED FACTOR 2 regulates Arabidopsis stomatal immunity through phosphorylation of the anion channel SLAC1. The Plant Cell, 32, 2216–2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. , Xu, F. , Qiang, X. , Liu, H. , Wang, L. , Jiang, L. et al. (2024) Regulated cleavage and translocation of FERONIA control immunity in Arabidopsis roots. Nature Plants, 10, 1761–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.‐L. , Lee, C.‐Y. , Cheng, K.‐T. , Chang, W.‐H. , Huang, R.‐N. , Nam, H.G. et al. (2014) Quantitative peptidomics study reveals that a wound‐induced peptide from PR‐1 regulates immune signaling in tomato. The Plant Cell, 26, 4135–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla, D. , Zipfel, C. , Robatzek, S. , Kemmerling, B. , Nürnberger, T. , Jones, J.D.G. et al. (2007) A flagellin‐induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature, 448, 497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFalco, T.A. & Zipfel, C. (2021) Molecular mechanisms of early plant pattern‐triggered immune signaling. Molecular Cell, 81, 3449–3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaunois, B. , Colby, T. , Belloy, N. , Conreux, A. , Harzen, A. , Baillieul, F. et al. (2013) Large‐scale proteomic analysis of the grapevine leaf apoplastic fluid reveals mainly stress‐related proteins and cell wall modifying enzymes. BMC Plant Biology, 13, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaunois, B. , Jeandet, P. , Clément, C. , Baillieul, F. , Dorey, S. & Cordelier, S. (2014) Uncovering plant‐pathogen crosstalk through apoplastic proteomic studies. Frontiers in Plant Science, 5, 249. Available from: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djamei, A. , Pitzschke, A. , Nakagami, H. , Rajh, I. & Hirt, H. (2007) Trojan horse strategy in Agrobacterium transformation: abusing MAPK defense signaling. Science, 318, 453–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farvardin, A. , González‐Hernández, A.I. , Llorens, E. , García‐Agustín, P. , Scalschi, L. & Vicedo, B. (2020) The apoplast: a key player in plant survival. Antioxidants, 9, 604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, L. , Santos, R.B. & Figueiredo, A. (2021) Defense and offense strategies: the role of aspartic proteases in plant–pathogen interactions. Biology (Basel), 10, 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorin, G.L. , Sanchéz‐Vallet, A. , Thomazella, D.P. , Prado, P.F.V. , Nascimento, L.C. , Figueira, A.V. et al. (2018) Suppression of plant immunity by fungal chitinase‐like effectors. Current Biology, 28, 3023–3030.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinn, B.S. (2008) Plant extracellular matrix metalloproteinases. Functional Plant Biology, 35, 1183–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, J.P. & Dong, X. (2014) Functional characterization of a Nudix hydrolase AtNUDX8 upon pathogen attack indicates a positive role in plant immune responses. PLoS One, 9, e114119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, B.C. & Beattie, G.A. (2009) Bacterial growth restriction during host resistance to Pseudomonas syringae is associated with leaf water loss and localized cessation of vascular activity in Arabidopsis thaliana . MPMI, 22, 857–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C. , Zhao, Y. , Wang, W. , Zhang, B. , Huang, X. , Wang, Y. et al. (2024) BRASSINOSTEROID‐SIGNALING KINASE 1 modulates OPEN STOMATA 1 phosphorylation and contributes to stomatal closure and plant immunity. The Plant Journal, 120, 45–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentzel, I. , Giese, L. , Ekanayake, G. , Mikhail, K. , Zhao, W. , Cocuron, J.‐C. et al. (2022) Dynamic nutrient acquisition from a hydrated apoplast supports biotrophic proliferation of a bacterial pathogen of maize. Cell Host & Microbe, 30, 502–517.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, B. , Dong, H. , Smith, C. , Cui, G. , Li, Y. & Bevan, M.W. (2022) Modulation of receptor‐like transmembrane kinase 1 nuclear localization by DA1 peptidases in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119, e2205757119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z. & Schneiter, R. (2024) Dual functionality of pathogenesis‐related proteins: defensive role in plants versus immunosuppressive role in pathogens. Frontiers in Plant Science, 15, 1368467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillmer, R.A. , Tsuda, K. , Rallapalli, G. , Asai, S. , Truman, W. , Papke, M.D. et al. (2017) The highly buffered Arabidopsis immune signaling network conceals the functions of its components. PLoS Genetics, 13, e1006639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou, S. , Liu, D. , Huang, S. , Luo, D. , Liu, Z. , Xiang, Q. et al. (2021) The Arabidopsis MIK2 receptor elicits immunity by sensing a conserved signature from phytocytokines and microbes. Nature Communications, 12, 5494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. , Wang, S. , Cai, Q. & Jin, H. (2021) Effective methods for isolation and purification of extracellular vesicles from plants. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 63, 2020–2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huot, B. , Yao, J. , Montgomery, B.L. & He, S.Y. (2014) Growth–defense tradeoffs in plants: a balancing act to optimize fitness. Molecular Plant, 7, 1267–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.‐H. , Jeong, S.‐H. , Kim, S.H. , Singh, R. , Lee, J. , Cho, Y.‐S. et al. (2008) Systematic secretome analyses of rice leaf and seed callus suspension‐cultured cells: workflow development and establishment of high‐density two‐dimensional gel reference maps. Journal of Proteome Research, 7, 5187–5210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaffarnik, F.A.R. , Jones, A.M.E. , Rathjen, J.P. & Peck, S.C. (2009) Effector proteins of the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae alter the extracellular proteome of the host plant, Arabidopsis thaliana . Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 8, 145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, H.Z. , Chen, K.‐E. , Karinshak, M. , Gu, X. , Sello, J.K. & Vierstra, R.D. (2025) Proteasomes accumulate in the plant apoplast where they participate in microbe‐associated molecular pattern (MAMP)‐triggered pathogen defense. Nature Communications, 16, 1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.T. , Kang, Y.H. , Wang, Y. , Wu, J. , Park, Z.Y. , Rakwal, R. et al. (2009) Secretome analysis of differentially induced proteins in rice suspension‐cultured cells triggered by rice blast fungus and elicitor. Proteomics, 9, 1302–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebminger, E. , Veit, C. , Pabst, M. , Batoux, M. , Zipfel, C. , Altmann, F. et al. (2011) β‐N‐Acetylhexosaminidases HEXO1 and HEXO3 are responsible for the formation of paucimannosidic N‐glycans in Arabidopsis thaliana . Journal of Biological Chemistry, 286, 10793–10802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G. , Kang, G. , Wang, S. , Huang, Y. & Cai, Q. (2021) Extracellular vesicles: emerging players in plant defense against pathogens. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, 757925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N. , Hou, L. , Chen, X. , Bao, J. , Chen, F. , Cai, W. et al. (2024) Arabidopsis TETRASPANIN8 mediates exosome secretion and glycosyl inositol phosphoceramide sorting and trafficking. The Plant Cell, 36, 626–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T. , Liu, Z. , Song, C. , Hu, Y. , Han, Z. , She, J. et al. (2012) Chitin‐induced dimerization activates a plant immune receptor. Science, 336, 1160–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. , Jackson, E. , Liu, X. , Huang, X. , van der Hoorn, R.A.L. , Zhang, Y. et al. (2024) Proteolysis in plant immunity. The Plant Cell, 36, 3099–3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. , Hou, S. , Rodrigues, O. , Wang, P. , Luo, D. , Munemasa, S. et al. (2022) Phytocytokine signalling reopens stomata in plant immunity and water loss. Nature, 605, 332–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovelace, A.H. , Chen, H.‐C. , Lee, S. , Soufi, Z. , Bota, P. , Preston, G.M. et al. (2022) RpoS contributes in a host‐dependent manner to Salmonella colonization of the leaf apoplast during plant disease. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13, 999183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovelace, A.H. , Smith, A. & Kvitko, B.H. (2018) Pattern‐triggered immunity alters the transcriptional regulation of virulence‐associated genes and induces the sulfur starvation response in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 31, 750–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez‐González, A.P. , Ardila, H.D. , Martínez‐Peralta, S.T. , Melgarejo‐Muñoz, L.M. , Castillejo‐Sánchez, M.A. & Jorrín‐Novo, J.V. (2018) What proteomic analysis of the apoplast tells us about plant–pathogen interactions. Plant Pathology, 67, 1647–1668. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan, H. , Gilroy, E.M. , Yun, B.‐W. , Birch, P.R.J. & Loake, G.J. (2009) Functional redundancy in the Arabidopsis Cathepsin B gene family contributes to basal defence, the hypersensitive response and senescence. New Phytologist, 183, 408–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merilahti, J.A.M. & Elenius, K. (2019) Gamma‐secretase‐dependent signaling of receptor tyrosine kinases. Oncogene, 38, 151–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakawa, T. , Hatano, K. , Miyauchi, Y. , Suwa, Y. , Sawano, Y. & Tanokura, M. (2014) A secreted protein with plant‐specific cysteine‐rich motif functions as a mannose‐binding lectin that exhibits antifungal activity. Plant Physiology, 166, 766–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott, G.A. , Middleton, M.A. , Desveaux, D. & Guttman, D.S. (2014) Peptides and small molecules of the plant‐pathogen apoplastic arena. Frontiers in Plant Science, 5, 677. Available from: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munzert, K.S. & Engelsdorf, T. (2025) Plant cell wall structure and dynamics in plant–pathogen interactions and pathogen defence. Journal of Experimental Botany, 76, 228–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemati, M. , Singh, B. , Mir, R.A. , Nemati, M. , Babaei, A. , Ahmadi, M. et al. (2022) Plant‐derived extracellular vesicles: a novel nanomedicine approach with advantages and challenges. Cell Communication and Signaling, 20, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura, M. (2016) Cell wall reorganization during infection in fungal plant pathogens. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology, 95, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary, B.M. , Neale, H.C. , Geilfus, C. , Jackson, R.W. , Arnold, D.L. & Preston, G.M. (2016) Early changes in apoplast composition associated with defence and disease in interactions between Phaseolus vulgaris and the halo blight pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola . Plant, Cell & Environment, 39, 2172–2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.‐J. & Ronald, P.C. (2012) Cleavage and nuclear localization of the rice XA21 immune receptor. Nature Communications, 3, 920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez‐Riverol, Y. , Bandla, C. , Kundu, D.J. , Kamatchinathan, S. , Bai, J. , Hewapathirana, S. et al. (2025) The PRIDE database at 20 years: 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Research, 53, D543–D553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrot, T. , Pauly, M. & Ramírez, V. (2022) Emerging roles of β‐glucanases in plant development and adaptative responses. Plants, 11, 1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petutschnig, E.K. , Stolze, M. , Lipka, U. , Kopischke, M. , Horlacher, J. , Valerius, O. et al. (2014) A novel Arabidopsis CHITIN ELICITOR RECEPTOR KINASE 1 (CERK1) mutant with enhanced pathogen‐induced cell death and altered receptor processing. New Phytologist, 204, 955–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, V. , López, A. , Mauch‐Mani, B. , Gil, M.J. & Vera, P. (2013) An extracellular subtilase switch for immune priming in Arabidopsis. PLoS Pathogens, 9, e1003445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussin‐Léveillée, C. , Mackey, D. , Ekanayake, G. , Gohmann, R. & Moffett, P. (2024) Extracellular niche establishment by plant pathogens. Nature Reviews. Microbiology, 22, 360–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubiato, H.M. , Liu, M. , O'Connell, R.J. & Nielsen, M.E. (2022) Plant SYP12 syntaxins mediate an evolutionarily conserved general immunity to filamentous pathogens. eLife, 11, e73487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, B.D. & Innes, R.W. (2017) Extracellular vesicles isolated from the leaf apoplast carry stress‐response proteins. Plant Physiology, 173, 728–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scopes, R.K. (1974) Measurement of protein by spectrophotometry at 205 nm. Analytical Biochemistry, 59, 277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serag, A. , Salem, M.A. , Gong, S. , Wu, J.‐L. & Farag, M.A. (2023) Decoding metabolic reprogramming in plants under pathogen attacks, a comprehensive review of emerging metabolomics technologies to maximize their applications. Metabolites, 13, 424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperschneider, J. , Dodds, P.N. , Singh, K.B. & Taylor, J.M. (2018) ApoplastP: prediction of effectors and plant proteins in the apoplast using machine learning. New Phytologist, 217, 1764–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoel, S.H. & Dong, X. (2024) Salicylic acid in plant immunity and beyond. The Plant Cell, 36, 1451–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teufel, F. , Almagro Armenteros, J.J. , Johansen, A.R. , Gíslason, M.H. , Pihl, S.I. , Tsirigos, K.D. et al. (2022) SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nature Biotechnology, 40, 1023–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres, M.A. , Jones, J.D.G. & Dangl, L.J. (2006) Reactive oxygen species signaling in response to pathogens. Plant Physiology, 141, 373–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Hoorn, R. (2008) Plant proteases: from phenotypes to molecular mechanisms. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 59, 191–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loon, L.C. , Rep, M. & Pieterse, C.M.J. (2006) Significance of inducible defense‐related proteins in infected plants. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 44, 135–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlot, A.C. , Sales, J.H. , Lenk, M. , Bauer, K. , Brambilla, A. , Sommer, A. et al. (2021) Systemic propagation of immunity in plants. New Phytologist, 229, 1234–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waghmare, S. , Lileikyte, E. , Karnik, R. , Goodman, J.K. , Blatt, M.R. & Jones, A.M.E. (2018) SNAREs SYP121 and SYP122 mediate the secretion of distinct cargo subsets1. Plant Physiology, 178, 1679–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. , Sun, W. , Kong, X. , Zhao, C. , Li, J. , Chen, Y. et al. (2020) The peptidyl‐prolyl isomerases FKBP15‐1 and FKBP15‐2 negatively affect lateral root development by repressing the vacuolar invertase VIN2 in Arabidopsis. Planta, 252, 52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. , Wang, Y. & Wang, Y. (2020) Apoplastic proteases: powerful weapons against pathogen infection in plants. Plant Communications, 1, 100085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. , Zeng, J. , Deng, J. , Hou, X. , Zhang, J. , Yan, W. et al. (2023) Pathogen‐derived extracellular vesicles: emerging mediators of plant‐microbe interactions. MPMI, 36, 218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin, X.‐F. , Nomura, K. , Aung, K. , Velásquez, A.C. , Yao, J. , Boutrot, F. et al. (2016) Bacteria establish an aqueous living space in plants crucial for virulence. Nature, 539, 524–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadeta, K.A. , Elmore, J.M. , Creer, A.Y. , Feng, B. , Franco, J.Y. , Rufian, J.S. et al. (2017) A cysteine‐rich protein kinase associates with a membrane immune complex and the cysteine residues are required for cell death1. Plant Physiology, 173, 771–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Y.‐H. , Chang, Y.‐H. , Huang, P.‐Y. , Huang, J.‐B. & Zimmerli, L. (2015) Enhanced Arabidopsis pattern‐triggered immunity by overexpression of cysteine‐rich receptor‐like kinases. Frontiers in Plant Science, 6, 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]