Abstract

Wild-type Daniel’s strain of Theiler’s virus (wt-DA) induces a chronic demyelination in susceptible mice which is similar to multiple sclerosis. A variant of wt-DA (designated DA-P12) generated during the 12th passage of persistent infection of a G26-20 glioma cell line failed to persist and induce demyelination in SJL/J mice. To identify the determinants responsible for this change in phenotype, we sequenced the capsid coding sequence (nucleotides [nt] 2991 to 3994) and found three mutations in VP1: residues 99 (Gly to Ser), 100 (Gly to Asp), and 103 (Asn to Lys). To study the role of these mutations in neurovirulence and demyelination, we prepared a recombinant virus, DAP-1C-2A/DA, with replacement of wt-DA nt 2991 to 3994 with the corresponding region of DA-P12, and viruses with individual point mutations at VP1 residues 99(Ser), 100(Asp), and 103(Lys). DAP-1C-2A/DA and viruses with a mutation at VP1 residue 99 or 100 (but not 103) completely attenuated the ability of wt-DA to induce demyelination. Failure to induce demyelination was not due to a general failure in growth, since DA-P12 and other mutant viruses lysed L-2 cells in vitro as effectively as wt-DA. The change in disease phenotype was independent of the specific B- or T-cell immune recognition because a decrease in the neurovirulence of mutant viruses was observed in neonatal mice and immune-deficient RAG1 −/− mice. This difference in neurovirulence is not the complete explanation for the failure of DA-P12 to demyelinate, since virus with a mutation at residue 103(Lys) had decreased neurovirulence but did induce demyelination. Therefore, point mutation at VP1 residue 99 or 100 altered the ability of wt-DA to demyelinate, perhaps related to a disruption in interaction between virus and receptor on certain neural cells.

Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV), a picornavirus, induces a biphasic disease in susceptible strains of mice characterized by early neuronal disease followed by chronic inflammatory demyelination (12, 29). Daniel’s strain (DA), one member of Theiler’s original subgroup (5), replicates lytically in neurons of gray matter during acute infection. Only mouse strains with a susceptible genotype develop chronic inflammatory demyelinating disease with viral persistence (5, 13), although mice with either a resistant or a susceptible genotype develop acute encephalitis.

DA-induced demyelinating disease appears to be immune mediated as is the case with multiple sclerosis (19), thus providing an important viral model for this human demyelinating disease. The mechanisms by which this potentially lytic virus establishes a persistent infection and induces demyelination in susceptible mice are not clear. In vitro studies show that DA lytically infects oligodendrocytes and neurons but persists in astrocytes and macrophages (6). In vivo studies suggest that demyelination may be the consequence of an immune-mediated response to infected cells (20, 24, 25). Studies using recombinant inbred strains of mice have demonstrated that resistance or susceptibility to demyelination maps genetically to the H-2D region (2, 21), indicating that the class I-mediated immune response plays an important role in resistance to the virus infection. Class I H-2Db- but not H-2Kb-restricted DA-specific cytotoxicity is present in the central nervous systems (CNS) of resistant B10 mice. However, no DA-specific cytotoxicity is seen in the CNS of susceptible B10.S and B10.Q mice (10, 11).

In our laboratory a variant of wild-type DA (wt-DA) was isolated from the 12th passage of a persistently infected G26-20 glioma cell line (designated DA-P12) (17). This variant virus produced smaller plaques than wild-type virus when assayed on L-2 cell monolayers and failed to induce persistent infection and chronic demyelination in the CNS of susceptible SJL/J mice. However, SJL/J mice partially immune suppressed with 300 rads of total body irradiation 1 day prior to infection with DA-P12 showed viral persistence but no demyelination.

In order to clarify the molecular determinants for the attenuated demyelinating activity of DA-P12, we sequenced regions of the genome that we suspected might result in a change in disease phenotype. We identified several changes in the VP1 coding sequence in the region of a neutralization site of the virus (31). Chimeric cDNA studies between DA-P12 and wt-DA and investigations of point mutant viruses confirmed the importance of two of these mutations, VP1 amino acid residues 99 and 100 (VP1 99 and VP1 100, respectively), in the change in disease phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

TMEV viruses and cDNA.

wt-DA was obtained originally from J. P. Lehrich and associates (9) and was grown in BHK-21 cells. wt-DA full-length infectious cDNA (pDAFL3) has been described previously (26). Variant DA-P12 was isolated originally from the 12th passage of a persistently infected G26-20 glioma cell line (17). A single plaque-purified clone of DA-P12 was grown in BHK-21 cells and used for all studies except the experiments examining viral growth in the mouse CNS.

Cells.

BHK-21 (baby hamster kidney cells) and L-2 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, Md.) with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.). BHK-21 cells were used to prepare virus stocks, and L-2 cells were used for plaque assays and in vitro growth studies.

Animals.

Four- to six-week-old SJL/J (H-2S) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). Four- to six-week-old B6x129-RAG1tm1Mom (referred to in the manuscript as RAG1 −/−) mice deficient in T- and B-cell functions were obtained originally from Jackson Laboratories and were bred at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. (15). Three-day-old neonatal B10.Q mice were obtained from Chella David (Department of Immunology, Mayo Clinic). Animals were injected intracerebrally (i.c.) with 2 × 105 PFU of virus in a 10-μl volume. In some experiments, mice received total body irradiation by use of a Gammator B irradiator (137Cs, 300 rads) from Isomeric Inc. (Parsippany, N.J.) 1 day before virus inoculation.

Construction of chimeric pDAP-1C-2A/DA plasmid and mutation of pDAFL3 at nt 3298 (VP1 99), 3302 (VP1 100), or 3312 (VP1 103).

L-2 cells in 25-cm2 flasks were infected with DA-P12 at 10 PFU/cell for 12 h. Total RNA from infected cells was isolated following a single-step method (1) and was used as the template for a reverse transcription reaction with the First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Alameda, Calif.) to synthesize first-strand cDNA. A DA-P12 cDNA fragment (nucleotide [nt] 2922 to 4020) spanning a region of VP3 (1C) to 2A that included all of the VP1 coding region (3004 to 3825) was amplified from the first-strand cDNA by PCR with two oligonucleotide primers (P1, CTCTGACATCCTCACTCTC; P2 GAGGGATCTGGAAGAGGTG), purified from a 1% agarose gel, and digested by PflMI and RsrII. A point mutation at nt 2021 from G to T which did not change the corresponding amino acid was made in pDAFL3 to inactivate the restriction endonuclease RsrII digestion site at this location. The digested DA-P12 cDNA fragment which spanned nt 2991 to 3994 was ligated into PflM I–Rsr II-digested mutated pDAFL3 to replace the corresponding wt-DA fragment. The inserted fragment was sequenced with a DNA Sequencing Version 2.0 kit (U.S. Biochemicals, Cleveland, Ohio) by using 35S-dATP (Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, Ill.). The chimeric full-length infectious plasmid was designated pDAP-1C-2A/DA.

Three mutations at nt 3298, 3302, and 3312 were prepared by using pDAFL3 as a template with a Muta-gene kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) according to previously published methods (28). The sequences of the mutant plasmids and viral genomes were confirmed by a double-stranded DNA sequencing kit (Gibco BRL). The three mutant full-length infectious cDNA plasmids were designated pDA-VP1-99(Ser) (changing Gly to Ser), pDA-VP1-100(Asp) (changing Gly to Asp), and pDA-VP1-103(Lys) (changing Asn to Lys).

Preparation of viruses from plasmids pDAFL3, pDAP-1C-2A/DA, pDA-VP1-99(Ser), pDA-VP1-100(Asp), and pDA-VP1-103(Lys).

Five micrograms each of pDAFL3 and pDAP-1C-2A/DA were linearized by digestion with restriction endonuclease XbaI and were transcribed in vitro to synthesize infectious viral RNA with the Ribomax Large Scale RNA Production System-T7 RNA Poly (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.). An aliquot of the reaction mix was applied to 1% RNA agarose gels to check the RNA quality. The RNA product was mixed with BHK-21 cells (106/ml), resuspended in ice-cold RNase-free 1× phosphate-buffered saline in 0.4-cm-electrode-gap cuvettes (Bio-Rad), incubated on ice for 5 min, pulsed once at 500 μF/350 V with a Bio-Rad Gene Pulse apparatus (Bio-Rad), returned to ice for 30 min, transferred to 25-cm2 flasks, fed with 3.5 ml of RPMI 1640 with 2% FCS, and was incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C. After complete cytopathic effect had occurred, cultures were harvested, serially diluted and plaque purified three times on monolayers of BHK-21 cells. Plaque-purified viruses were used to infect BHK-21 cells cultured in 150-cm2 flasks to prepare viral stocks. The three mutant viruses were prepared by previously published methods (28). The titers of viral stocks were determined by plaque assay on monolayers of L-2 cells as described below. The RNA isolated from BHK-21 cells infected by these viruses was reverse transcribed and sequenced to confirm that the appropriate mutations were present.

Virus plaque assay.

Viral titers of clarified CNS homogenates or infected cell cultures were determined by plaque assay as described previously with L-2 cells (17).

In vitro growth kinetics of viruses.

Monolayers of L-2 cells in 12-well plates were infected with 200 μl of virus. Following adsorption for 1 h at 37°C, cell cultures were fed with 2 ml of RPMI 1640 with 5% FCS. Two wells from the cell cultures were collected at 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h postinfection (p.i.). Cells and supernatants were frozen at −70°C, thawed, sonicated for 20 s, and centrifuged at 1,430 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Supernatants were harvested and stored at −70°C. Viral titers of supernatants were determined by plaque assay as described previously (17).

In vivo growth kinetics of viruses in young adult SJL/J and neonatal B10.Q mice.

Four- to six-week-old SJL/J and irradiated SJL/J mice or 3-day-old neonatal B10.Q mice were injected i.c. with 2 × 105 PFU of virus in a 10-μl volume. Brains and spinal cords from three to five SJL/J mice were removed aseptically on days 2, 4, 7, 10, and 45 p.i. Three to five B10.Q neonatal mice were sacrificed at 6 h and at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 15, and 45 days following infection. CNS homogenates (10%) were prepared in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, sonicated for two 60-s intervals, and clarified by centrifugation. Viral supernatants were stored at −70°C, and titers were determined by plaque assay on monolayers of L-2 cells.

Virus-specific antibody determination.

The presence of anti-TMEV antibodies in the sera of infected mice was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as described previously (17).

Pathologic analysis.

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital and perfused by intracardiac puncture with Trump’s fixative (phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde, pH 7.2). Spinal cords were removed, sectioned coronally and serially into 15 to 20 blocks, osmicated, and embedded in 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (JB-4 system from Polysciences). By a modified erichrome method with cresyl violet counterstain (18), 2-μm-thick sections were stained to detect demyelination and inflammation. Detailed morphologic analysis was performed by examining each quadrant from 15 to 20 spinal cord coronal sections from each mouse for the presence or absence of demyelination, white matter inflammation, and gray matter inflammation (22). The presence or absence of the pathologic abnormality was determined in every spinal cord quadrant. The total score was expressed as the percentage of spinal cord quadrants with the specific abnormality such that a maximum score of 100 represented the presence of disease in every quadrant of every spinal cord section examined. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonfarroni adjustment T tests were used to evaluate significant differences in pathologic scores between mice infected with different viruses.

In situ hybridization.

Frozen brain and spinal cord sections were hybridized overnight with a 35S-labeled probe complementary to the coding region of VP1 (nt 3053 to 3305) (16). After being washed extensively, slides were exposed in nitroblue tetrazolium-2 emulsion (Eastman Kodak) for 48 h as described previously (17). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin.

RESULTS

Growth kinetics in vivo of DA-P12, an isolate from a persistently infected glioma cell line.

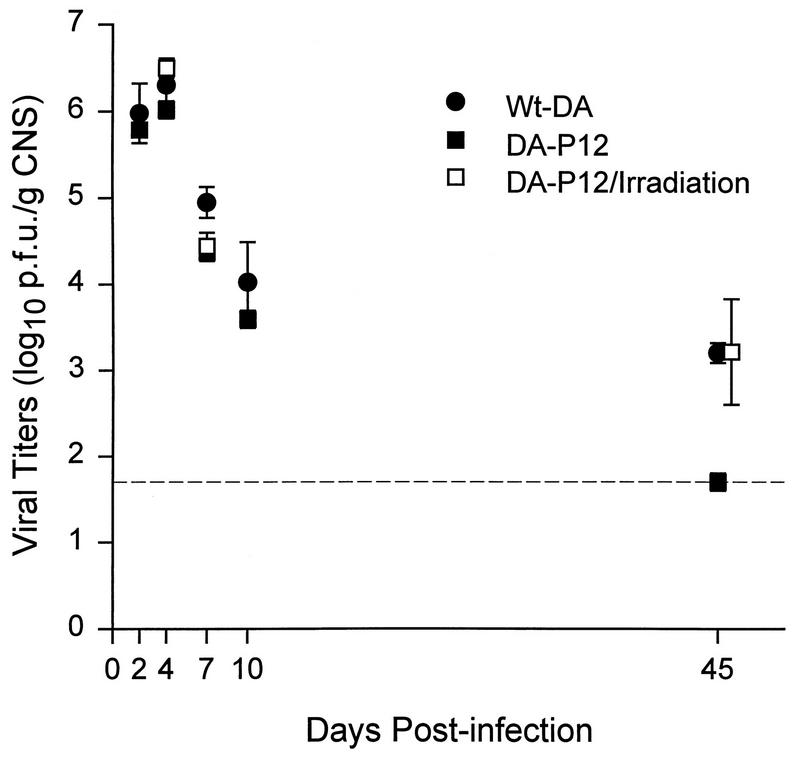

We first determined the growth kinetics of DA-P12 and wt-DA in young adult SJL/J and irradiated SJL/J mice. Both viruses replicated in the CNS and reached peak titers at 4 days p.i. (d.p.i.) (Fig. 1). Viral titers for DA-P12 in untreated SJL/J mice were below the sensitivity of the plaque assay by 45 d.p.i., whereas wt-DA persisted (3.2 ± 0.12 log10 PFU/g of CNS [mean ± standard deviation]). The growth kinetics of DA-P12 in the CNS of irradiated SJL/J mice was similar to that of wt-DA in untreated SJL/J mice. At 45 d.p.i., DA-P12 was detected in the CNS of three of five irradiated SJL/J mice (3.21 ± 0.61 log10 PFU/g of CNS), whereas wt-DA was detected in the CNS of all five untreated SJL/J mice. The average infectious virus titers in both groups were similar (P > 0.05). Even though virus persisted in irradiated SJL/J mice infected with DA-P12, no demyelination was observed in five animals sacrificed at 45 d.p.i. (17). These experiments established that blunting the immune response with irradiation enabled DA-P12 to replicate and persist in the CNS of SJL/J mice. However, the virus was unable to induce demyelination in these irradiated mice despite virus persistence.

FIG. 1.

Growth kinetics of viruses in the CNS of irradiated and nontreated young adult SJL/J mice. All mice received 2 × 105 PFU of virus i.c. Irradiated mice received 300 rads 1 day before virus inoculation and were sacrificed on days 4, 7, and 45. Titers of CNS homogenates were determined on L-2 cell monolayers and are expressed as log10 PFU/g of CNS. Means ± standard errors of the means were calculated based on results from three to five mice sacrificed at each time point. The dashed line represents the sensitivity of the plaque assay (1.7 log10 PFU/g of CNS).

Replication of DA-P12 in neonatal mice.

Previous studies demonstrated that wt-DA infection of neonatal mice, which lack a mature immune system, resulted in fatal encephalitis (23). To further define the virulence and replicative capacity of DA-P12, neonatal B10.Q mice were infected with wt-DA (n = 35) or DA-P12 (n = 60) and survival analysis was performed. More than 90% of neonates infected with wt-DA were dead within 12 days. In contrast, only 10% of mice inoculated with DA-P12 had died by day 12.

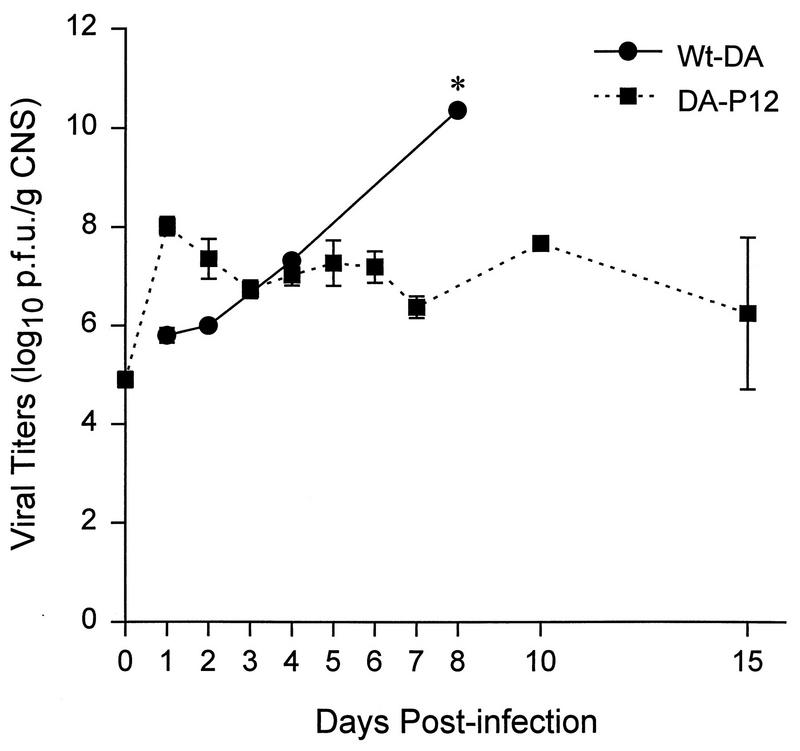

At each time point, infectious virus titers in the CNS were determined for three to five neonatal mice infected with either wt-DA or DA-P12. Mice were sacrificed from 1 to 15 days after infection (Fig. 2). Viral titers in the CNS of mice infected with wt-DA increased continuously to as high as 10.4 log10 PFU/g of CNS by 8 d.p.i. In these second set of experiments no neonatal mice infected with wt-DA survived after 8 d.p.i. In contrast the level of infectious virus in the CNS of neonates infected with DA-P12 increased quickly to 8 log10 PFU/g of CNS at 1 d.p.i. and was maintained at 7 log10 PFU/g of CNS until 15 d.p.i., the latest time point sampled. Similar results were obtained with the CNS of neonatal BSVS mice, which have a resistant haplotype to TMEV-induced demyelination (data not shown). These results demonstrated that the growth capacity and neurovirulence of DA-P12 is attenuated in the CNS of neonatal mice. DA-P12 could replicate and persist in the CNS of neonatal mice but was not as lethal to neonatal mice as wt-DA.

FIG. 2.

Growth kinetics of viruses in the CNS of neonatal B10.Q mice (H-2q haplotype susceptible to demyelination with wt-DA). All mice received 2 × 105 PFU of virus i.c. Titers of CNS homogenates of infected neonatal mice were determined on monolayers of L-2 cells and are expressed as log10 PFU/g of CNS. Means ± standard errors of the means were calculated based on results from two to five mice sacrificed at each time point. No mice infected with wt-DA survived past day 8 in this experiment (indicated by asterisk).

Comparison of the nucleotide sequence from DA-P12 fragment 2991 to 3994 with wt-DA.

To study the possible role of DA-P12 VP1 in the attenuation of neurovirulence, a cDNA fragment (nt 2991 to 3994) including the VP1 coding region (nt 3004 to 3825) was generated from the RNA of a plaque-purified virus stock, DA-P12. Sequencing showed that there were six mutations in VP1 that differed from the published sequence of wt-DA (DAFL3) (16): nt 3090 (C to T), 3298 (G to A), 3302 (G to A), 3312 (T to A), 3390 (T to C), and 3666 (C to T). Mutations at nt 3090, 3390, and 3666 did not change the corresponding amino acid sequences, while mutations at nt 3298, 3302, and 3312 changed the corresponding amino acids from Gly to Ser (VP1 99), from Gly to Asp (VP1 100), and from Asn to Lys (VP1 103), respectively. Another point mutation at nt 2995 (G to T) near the 3′ end of the VP3 coding region changed codon 230 of VP3 from Ala to Ser.

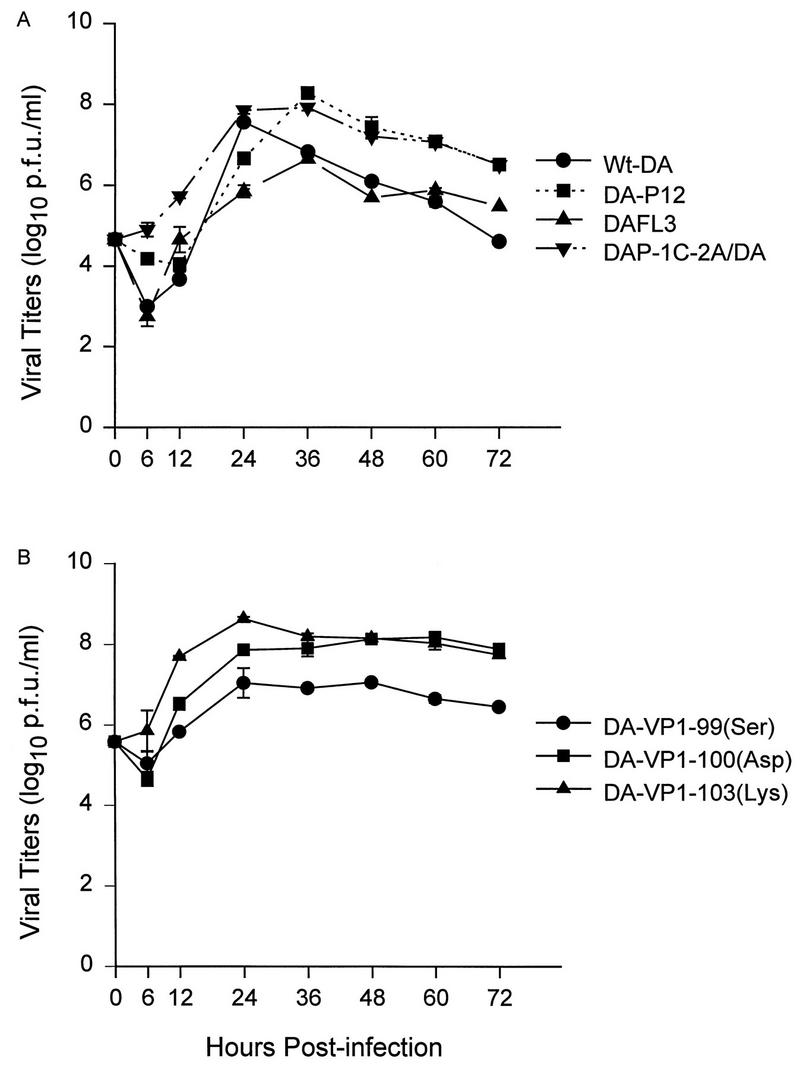

In vitro growth kinetics of viruses.

We assayed the growth kinetics of viruses on monolayers of L-2 cells (Fig. 3). DA-P12 and DAP-1C-2A/DA propagated as efficiently as wt-DA and DAFL3 (Fig. 3A), and their growth kinetics were similar to those of the mutant viruses shown in Fig. 3B. Titers for all viruses peaked (to approximately 7 to 8 log10 PFU/ml) at about 24 to 36 h after infection. We concluded that DA-P12, recombinant DAP-1C-2A/DA, and the three mutant viruses proliferated similarly and efficiently in vitro and were not growth-defective viruses.

FIG. 3.

Growth of viruses in vitro was assayed on L-2 cell monolayers. Cell cultures were harvested from 6 to 72 h after infection. Viral titers of cultures are expressed as log10 PFU/ml. Means (± standard errors of the means) were calculated from results for two parallel wells.

Plaque morphology.

Previous data from our laboratory demonstrated that wt-DA produced a variable plaque morphology, whereas DA-P12 produced small plaques on L-2 cell monolayers (17). We compared the plaque morphology of various viruses on monolayers of L-2 cells (Table 1). The plaque sizes of wt-DA, DAFL3, and DAP-1C-2A/DA were similar and were larger than the plaque sizes of DA-P12, DA-VP1-99(Ser), DA-VP1-100(Asp), and DA-VP1-103(Lys). These results showed that plaque size was not determined by the mutations investigated and did not correlate with the ability of viruses to demyelinate or to induce paralysis and/or death in immunodeficient mice (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Plaque-purified viruses used

| Virus | Description | Plaque size (mm)a | Neurovirulenceb | Demyelinationc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt-DA | Wild-type Daniel’s strain of TMEV | 1.05 ± 0.08 | ++ | Yes |

| DA-P12 | 12th passage of persistently infected glioma cell line | 0.61 ± 0.06 | + | No |

| DAFL3 | From full-length infectious pDAFL3 | 0.90 ± 0.05 | ++ | Yes |

| DAP-1C-2A/DA | Chimeric virus with VP3-228 to 2A-58 from DA-P12 | 0.96 ± 0.07 | + | No |

| DA-VP1-99(Ser) | Mutation at VP1 99 from Gly to Ser in DAFL3 | 0.47 ± 0.02 | + | No |

| DA-VP1-100(Asp) | Mutation at VP1 100 from Gly to Asp in DAFL3 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | + | No |

| DA-VP1-103(Lys) | Mutation at VP1 103 from Asn to Lys in DAFL3 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | + | Yes |

Plaque sizes are means ± standard errors of the means for growth on L-2 cell monolayers.

Replication capacity in the CNS based on the ability of virus to induce paralysis and death in RAG1 −/− mice (see Table 3).

Demyelination based on the analysis of spinal cord sections from SJL/J mice at 45 d.p.i. (see Table 2).

DA-P12-, DAP-1C-2A/DA-, DA-VP1-99(Ser)-, DA-VP1-100(Asp)-, and DA-VP1-103(Lys)-stimulated production of TMEV-specific antibodies.

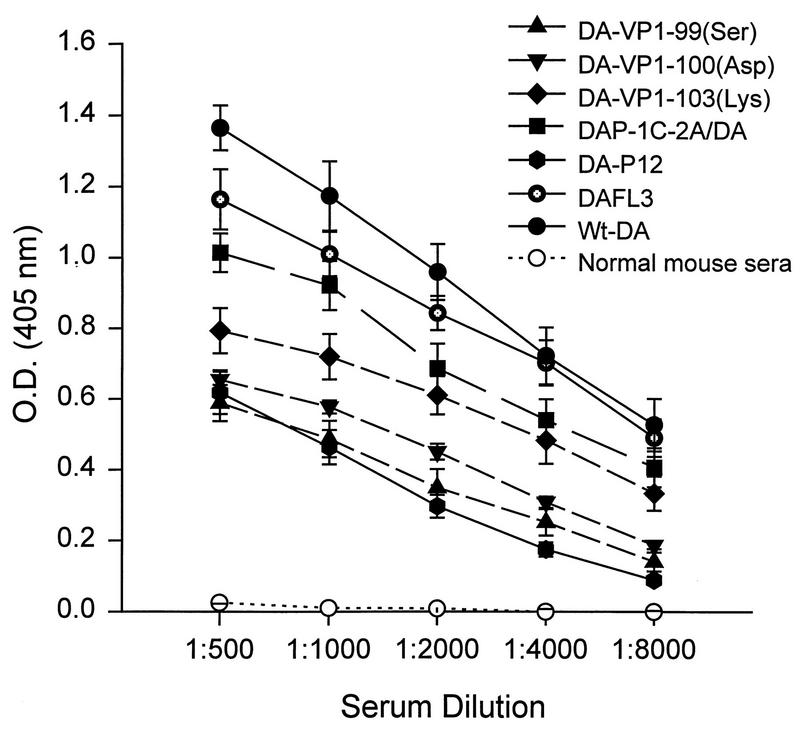

Both wt-DA and DA-P12 were shown previously to stimulate the production of TMEV-specific antibodies (17). We collected sera from SJL/J mice at 45 d.p.i. SJL/J mice infected with wt-DA or mutant virus produced high levels of TMEV-specific antibodies (Fig. 4), indicating that the mutant viruses replicated sufficiently in the CNS of SJL/J mice to induce a specific humoral immune response. As expected, no TMEV-specific antibodies were detected in the sera of RAG1 −/− mice infected with these viruses.

FIG. 4.

TMEV-specific immunoglobulin G by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay utilizing wt-DA antigen. Sera were collected from SJL/J mice infected with various Theiler’s viruses as shown. Sera from uninfected SJL/J mice were used as a control. Data are means ± standard errors of the means from an analysis performed in triplicate of sera from five mice.

Mutation in DA VP1 99 or 100 independently attenuates the ability of wt-DA to induce chronic demyelination.

wt-DA but not DA-P12 induces chronic demyelination in susceptible SJL/J mice following inoculation (17). We first determined whether a region spanning VP3 (1C) to 2A was responsible for the attenuation of the demyelinating activity of DA-P12 by generating DAP-1C-2A/DA recombinant virus and testing its disease phenotype. No demyelination or white matter inflammation was observed in 4 SJL/J mice at 45 d.p.i. with the recombinant virus (Table 2 and Fig. 5C). In contrast prominent demyelination was observed following infection with wt-DA or DAFL3 (Table 2 and Fig. 5A).

TABLE 2.

Pathologic scores in spinal cords of SJL/J mice infected with viruses for 45 days

| Virus | No. of mice | % Quadrants (mean ± SEM) positive for abnormalitya

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gray matter inflammation | White matter inflammation | Demyelination | ||

| wt-DA | 8 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 30.4 ± 5.0 | 31.3 ± 5.3 |

| DAFL3 | 5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 27.2 ± 10.0 | 27.9 ± 10.4 |

| DA-P12 | 7 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| DAP-1C-2A/DA | 4 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| DA-VP1-99(Ser) | 10 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| DA-VP1-100(Asp) | 5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| DA-VP1-103(Lys) | 5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 22.8 ± 8.5 | 17.9 ± 8.0 |

Statistical analysis was performed by using ANOVA and Bonfarroni adjustment T tests to compare pathologic scores of SJL/J mice infected with various viruses for 45 days. There was no statistically significant difference in pathologic scores among wt-DA, DAFL3, and DA-VP1-103(Lys) (P > 0.05). Demyelination and white matter inflammation scores were significantly greater in wt-DA, DAFL3, and DA-VP1-103(Lys) compared to DA-P12, DAP-1C-2A/DA, DA-VP1-99(Ser), or DA-VP1-100(Asp) (P < 0.01).

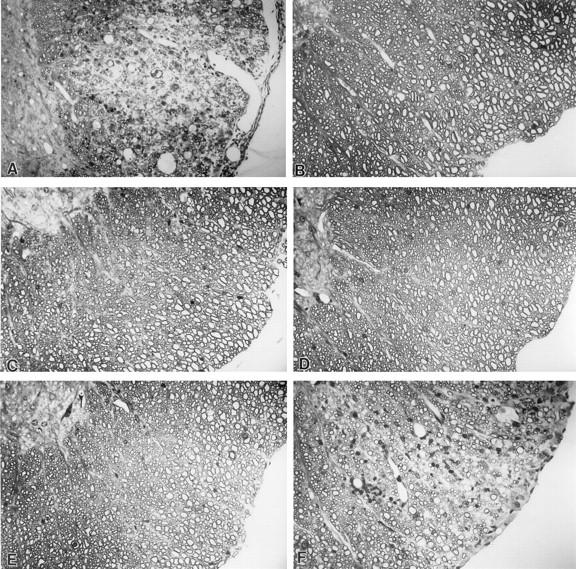

FIG. 5.

DAFL3 (A) and DA-VP1-103(Lys) (F) induced demyelination in the spinal cords of SJL/J mice 45 d.p.i., whereas DA-P12 (B), recombinant virus DAP-1C-2A/DA (C), DA-VP1-99(Ser) (D), and DA-VP1-100(Asp) (E) did not induce demyelination. Glycol methacrylate-embedded sections were stained with a modified erichrome-cresyl violet stain Magnification, ×380.

We next tested which one or more of the three amino acid mutations in VP1 that were included in the VP3 to 2A segment from DA-P12 were responsible for the loss in demyelinating activity. We generated three viruses which separately contained one of the three mutations (Table 2). We then determined the disease phenotypes of the mice inoculated with the mutant viruses. DA-VP1-103(Lys) induced severe white matter inflammation and demyelination such that approximately one quarter of spinal cord quadrants showed pathology by 45 d.p.i. (Fig. 5F). For SJL/J mice there was no difference statistically between the percentage of quadrants showing white matter inflammation or demyelination induced by wt-DA compared to that induced by DAFL3 or DA-VP1-103(Lys) (P > 0.05). Demyelination was extensive in SJL/J mice inoculated with DA-VP1-103(Lys) virus despite the fact that this mutant virus was less neurovirulent than wt-DA in RAG1 −/− mice (Table 3). In contrast, DA-VP1-99(Ser) (Fig. 5D) and DA-VP1-100(Asp) (Fig. 5E) failed to induce meningeal inflammation or demyelination in SJL/J mice at 45 d.p.i. (Table 2). Therefore, the inability of DA-P12 to induce demyelination in SJL/J mice was determined by a mutation in either VP1 99 or 100 but not 103.

TABLE 3.

Neurovirulence of viruses in immunodeficient micea

| Virus | No. of mice with signs/total no. of mice | d.p.i. for occurrence of paralysis and deathb |

|---|---|---|

| wt-DA | 10/10 | 7–9 |

| DA-P12 | 4/11 | 9–24 |

| DA-P12c | 3/3 | 23–28 |

| DA-P12d | 3/3 | 21 |

| DAFL3 | 8/8 | 10–14 |

| DAP-1C-2A/DA | 5/5 | 18–19 |

| DA-VP1-99(Ser) | 3/3 | 20–22 |

| DA-VP1-100(Asp) | 3/3 | 26–31 |

| DA-VP1-103(Lys) | 3/3 | 20–21 |

RAG1 −/− mice were each injected i.c. with 2 × 105 PFU of virus unless otherwise indicated.

Mice were sacrificed when they showed severe paralysis.

2 × 106 PFU/mouse.

6 × 106 PFU/mouse.

To demonstrate the ability of mutant viruses to persist in the CNS of SJL/J mice, mice infected with mutant viruses for 45 days were sacrificed, and brains and spinal cords were sectioned and hybridized with a 35S-labeled VP1 cDNA probe. Viral RNA was detected in the CNS of mice infected with DAFL3 or DA-VP1-103(Lys) but not in the CNS of mice infected with DA-VP1-99(Ser), DA-VP1-100(Asp), or DAP-1C-2A/DA (data not shown).

Demyelinating virus DA-VP1-103(Lys) has the same neurovirulence as nondemyelinating viruses DA-VP1-99(Ser) and DA-VP1-100(Asp).

To determine the intrinsic ability of the viruses to replicate in the CNS in the absence of an immune system, RAG1 −/− mice were inoculated i.c. with wild-type and mutant viruses (2 × 105 PFU/mouse). Mice infected with wt-DA or DAFL3 showed severe hind-leg paralysis and became moribund from 7 to 14 d.p.i. (Table 3). In contrast, only approximately 40% of mice infected with DA-P12 (2 × 105 PFU) showed clinical symptoms which were apparent 9 to 24 d.p.i. Although larger amounts of DA-P12 (2 × 106 or 6 × 106 PFU) caused severe paralysis or death in all RAG1 −/− mice, these effects were delayed compared to those in wt-DA- and DAFL3-infected mice, occurring from 21 to 28 d.p.i. Similarly, DAP-1C-2A/DA, DA-VP1-99(Ser), DA-VP1-100(Asp), and DA-VP1-103(Lys) were less virulent than DAFL3 or wt-DA since 2 × 105 PFU of these viruses resulted in neurologic deficits or death in RAG1 −/− mice that occurred 18 to 31 d.p.i.

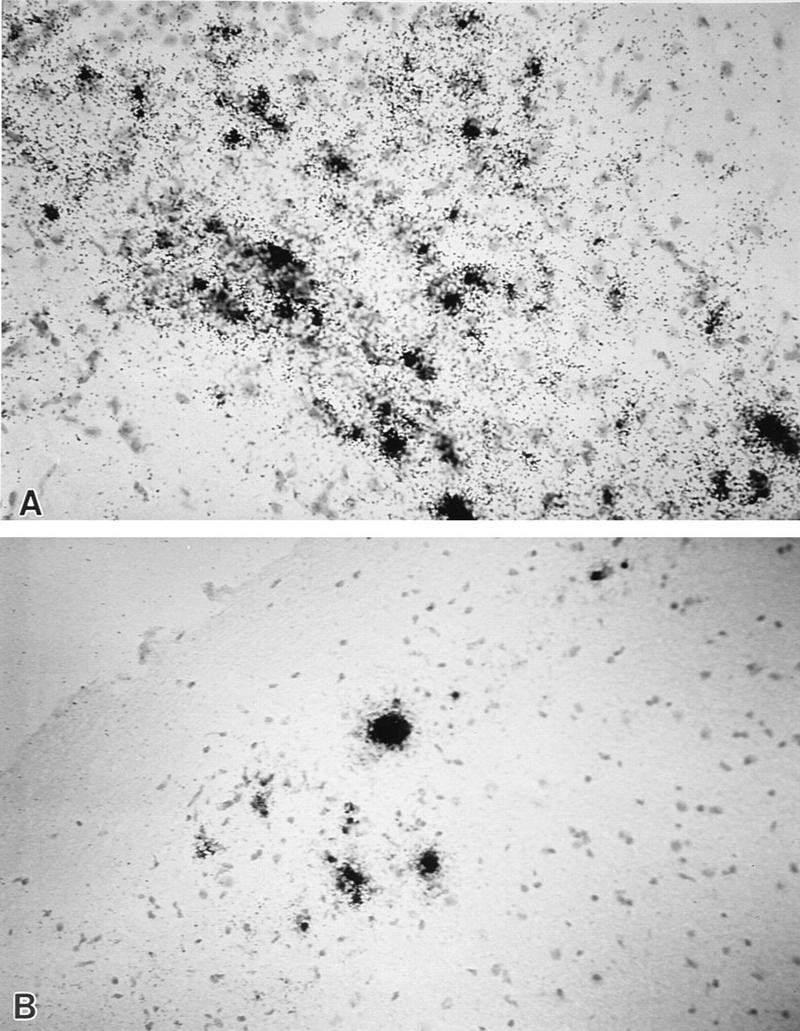

Mice were sacrificed for pathologic analysis at the time of maximal clinical symptoms. RAG1 −/− mice infected with 2 × 105 PFU of wt-DA (n = 4), DAFL3 (n = 3), or DAP-1C-2A/DA (n = 4) showed severe vacuolar changes of neurons. In contrast, fewer pathologic abnormalities were seen in mice infected with 2 × 105 PFU of DA-P12 (n = 7). Viral RNA was detected by in situ hybridization with a 35S-labeled VP1 cDNA probe in the brains and spinal cords of all RAG1 −/− mice infected with wt-DA, DAFL3, DA-VP1-99(Ser), DA-VP1-100(Asp), DA-VP1-103(Lys), or DAP-1C-2A/DA (Fig. 6). Viral RNA was detected in the CNS of only three of six mice infected with DA-P12 at 2 × 105 PFU but was detected in the CNS of all mice infected at 2 × 106 PFU. No demyelination was observed in RAG1 −/− mice infected with any of the viruses at the time of maximal clinical symptoms. These studies demonstrated that all of the mutant viruses can replicate in the CNS in the absence of specific B- or T-cell immune response. The mutant viruses, however, are less neurovirulent than wt-DA since they have a decreased capacity to paralyze and induce less pathology in RAG1 −/− mice.

FIG. 6.

Localization of viral RNA in the brain (A) and spinal cord (B) of a RAG1 −/− mouse infected with recombinant virus DAP-1C-2A/DA for 18 days. The results of in situ hybridization with a 35S-labeled VP1 cDNA probe are shown. Cells were counterstained with hematoxylin. Similar results were obtained in RAG1 −/− mice infected with DAFL3. Magnification, ×340.

DISCUSSION

DA and other members of the Theiler’s original subgroup of TMEV cause a persistent CNS infection in weanling mice with evidence of demyelination that begins about 3 weeks p.i. and continues for the life of the mouse. DA-induced disease stands as an excellent experimental model of multiple sclerosis since both diseases have similar pathologies and because the immune system appears to contribute to demyelination in both processes. One of our goals is to better understand the molecular determinants for DA-induced demyelination and the mechanisms of demyelination since this information may not only help to clarify our understanding of this virus-induced disease but that of MS as well. With this goal in mind we had previously isolated a strain of DA (DA-P12) following passage in G26-20 cells that failed to demyelinate or persist in highly susceptible SJL/J mice (17). The present study was directed at identifying the mutation(s) that caused this change in disease phenotype and to begin to clarify the reasons for the attenuation in demyelinating activity of the isolate.

Because mutations in regions of DA VP1 have been associated with changes in demyelination phenotype (27, 31), we prepared a chimeric cDNA in which nt 2991 to 3994 (which codes for part of VP3 [1C], all of VP1, and part of 2A) from a plaque-purified clone of DA-P12 was substituted for the corresponding region of wt-DA. The recombinant virus, DAP-1C-2A/DA, maintained the non-demyelinating phenotype of the original mutant isolate, indicating that a change in nucleotides from VP3 to 2A was sufficient to attenuate the demyelinating activity. We found that the VP1 coding sequence of DA-P12 had three amino changes compared to that of wt-DA: residues 99 (Gly to Ser), 100 (Gly to Asp), and 103 (Asn to Lys). We then used site-directed mutagenesis to individually engineer these changes into wt-DA to produce DA-VP1-99(Ser), DA-VP1-100(Asp), and DA-VP1-103(Lys) viruses, respectively. Studies with these mutant viruses indicated that a change in either VP1 99 or 100 but not 103 completely attenuated the demyelinating activity of DA and was sufficient to produce the altered disease phenotype of DA-P12.

We next investigated the basis for the failure of DA-P12 to induce demyelination in weanling mice. Our studies demonstrated that DA-P12 did not replicate as efficiently as wt-DA in neonatal mouse brain. This failure of DA-P12 to replicate as efficiently in the CNS was not due to a general defect in virus growth because there was no difference between wt-DA and DA-P12 with respect to growth kinetics in BHK-21 cells.

To test whether the cause of the decreased growth in the CNS was independent of T- and B-cell responses, we inoculated RAG1 −/− mice with the different viruses. We found that DA-P12 and DA-VP1-99(Ser), DA-VP1-100(Asp), and DA-VP1-103(Lys) were less neurovirulent than wt-DA. These results suggest that a reason for the decreased growth of DA-P12 in the CNS is related to a change in growth of the virus that is distinct from any effect of B- or T-cell immune recognition, but innate elements of immunity such as NK cells and macrophages could still influence neurovirulence. Differences in neurovirulence cannot be the complete explanation for the failure of DA-P12 to induce demyelination since the neurovirulence of DA-VP1 103(Lys) was as decreased as that of DA-VP1-99(Ser) and DA-VP1-100(Asp) but nevertheless it did induce demyelination.

VP1 99 and 100 (and 103) are in the region of a neutralization site of DA (31). Mutations in a number of amino acid residues included in both this site (VP1 101) and other neutralization sites (VP1 268 and VP2 141) have similarly led to virus variants that have decreased levels of demyelinating activity (8, 28, 31). Studies using nude mice inoculated with variant viruses that have mutations in neutralization epitopes (VP1 101 [32] and VP2 141 [8]) have also suggested that the change in disease phenotype of the variants is independent of the host’s immune response.

We and others have proposed that the change in disease phenotype following mutations in residues included in neutralization sites is related to altered binding efficiency between the virus and cellular receptor (8, 28, 30). The neutralization sites correspond to exposed regions of the capsid surface which are readily accessible to antibody. These sites cluster around a depression in the virion surface that has been called the “pit” (14) and which has been predicted to be the binding site on the virus for the cellular receptor. A mutation at the rim of the pit may interfere with binding of the virus to the receptor of a particular cell type (possibly oligodendrocytes or microglia) or lead to a less optimal fit of the receptor into the pit, therefore affecting virus growth in certain neural cells (28). In this report, we demonstrated that DA-VP1-103(Lys) persists in the CNS of SJL/J mice, whereas DA-VP1-99(Ser) and DA-VP1-100(Asp) do not. It is possible that DA-VP1-99(Ser) and DA-VP1-100(Asp) grow well in BHK-21 cells but less well in vivo in a number of different CNS cell types. DA-VP1-103(Lys) may also grow less well in neuronal cells of the neonatal mouse and RAG1 −/− mice but nevertheless grow better than the two other mutant viruses in cell types that mediate demyelination of SJL/J mice, i.e., glial cells and macrophages.

G26-20 cells may have a slightly different receptor than the receptor on neural cells, so that repeated passage of DA in G26-20 cells may have led to mutations in residues on the rim of the pit which allow for better growth (of DA-P12) in these cells. Although these changes may have permitted efficient infection of G26-20 cells, they may have interfered with growth of virus in certain neural cells, thereby generating a variant virus that fails to demyelinate. In the case of human poliovirus, another picornavirus, growth on particular cells similarly leads to changes in the host range of the virus and alterations in receptor recognition (3, 4). Changes in antigenic determinants located at the rim of the poliovirus canyon (analogous to the pit in TMEV) have been shown to influence binding of the virus to the poliovirus receptor (7). The ability of a virus to both change its receptor binding as well as alter an antigenic epitope through mutation of a single amino acid residue allows the virus to change its tropism at the same time that it eludes the immune response. It is clear that this capability provides the opportunity for the virus to induce new diseases in new tissues or hosts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

X.L. and S.S. contributed equally to this work.

These experiments were supported by NIH grants R01-NS24180, R01-NS32129, and N01-AI-4-5197 and by a grant from the National MS Society.

We appreciate the technical assistance of Kevin D. Pavelko and Mable Pierce, who helped with the animal experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clatch R J, Melvold R W, Miller S D, Lipton H L. Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-induced demyelinating disease in mice is influenced by the H-2D region: correlation with TMEV-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity. J Immunol. 1985;135:1408–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colston E M, Racaniello V R. Poliovirus variants selected on mutant receptor-expressing cells identify capsid residues that expand receptor recognition. J Virol. 1995;69:4823–4829. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4823-4829.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couderc T, Guedo N, Calvez V, Pelletier I, Hogle J, Colbere-Garapin F, Blondel B. Substitutions in the capsids of poliovirus mutants selected in human neuroblastoma cells confer on the Mahoney type 1 strain a phenotype neurovirulent in mice. J Virol. 1994;68:8386–8391. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8386-8391.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels J B, Pappenheimer A M, Richardson S. Observations on encephalomyelitis of mice (DA strain) J Exp Med. 1952;96:517–535. doi: 10.1084/jem.96.6.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graves M C, Bologa L, Siegel L, Londe H. Theiler’s virus in brain cell cultures: lysis of neurons and oligodendrocytes and persistence in astrocytes and macrophages. J Neurosci Res. 1986;15:491–501. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harber J, Bernhardt G, Lu H-H, Sgro J-V, Wimmer E. Canyon rim residues, including antigenic determinants, modulate serotype-specific binding of polioviruses to mutants of the poliovirus receptor. Virology. 1995;214:559–570. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarousse N, Martinat C, Syan S, Brahic M. Role of VP2 amino acid 141 in tropism of Theiler’s virus within the central nervous system. J Virol. 1996;70:8213–8217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8213-8217.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehrich J R, Arnason B G, Hochberg F H. Demyelinative myelopathy in mice induced by the DA virus. J Neurol Sci. 1976;29:149–160. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(76)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin X, Piece L, Rodriguez M. Differential generation of H-2D- versus H-2K-restricted cytotoxicity against demyelinating virus in the central nervous system and spleen. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:263–270. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin X, Thiemann R, Piece L, Rodriguez M. VP1 and VP2 capsid proteins of Theiler’s virus are targets of H-2D-restricted cytotoxic lymphocytes in the central nervous system of B10 mice. Virology. 1995;214:91–99. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.9951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipton H L. Theiler’s virus infection in mice: an unusual biphasic disease process leading to demyelination. Infect Immun. 1975;11:1147–1155. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.5.1147-1155.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorch Y, Friedmann A, Lipton H L, Kotler M. Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus group includes two distinct genetic subgroups that differ pathologically and biologically. J Virol. 1981;40:560–567. doi: 10.1128/jvi.40.2.560-567.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo M, He C, Toth K S, Zhang C X, Lipton H L. Three-dimensional structure of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (BeAn strain) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2409–2413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mombaerts P, Iacomini J, Johnson R S, Herrup K, Tonegawa S, Papaioannou V E. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;68:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohara Y, Stein S, Fu J L, Stillman L, Roos R P. Molecular cloning and sequence determination of DA strain of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis viruses. Virology. 1988;164:245–255. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90642-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patick A K, Oleszak E L, Leibowitz J L, Rodriguez M. Persistent infection of a glioma cell line generates a Theiler’s virus variant which fails to induce demyelinating disease in SJL/J mice. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:2123–2132. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-9-2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierce M, Rodriguez M. Erichrome stain for myelin on osmicated tissue embedded in glycol methacrylate plastic. J Histotechnol. 1989;12:35–36. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez M. Multiple sclerosis: basic concepts and hypothesis. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1989;64:570–576. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)65563-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez M, Lafuse W P, Leibowitz J L, David C S. Partial suppression of Theiler’s virus-induced demyelination in vivo by administration of monoclonal antibodies to immune response gene products (Ia antigens) Neurology. 1986;30:964–970. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.7.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez M, Leibowitz J L, David C S. Susceptibility to Theiler’s virus-induced demyelination. Mapping of the gene within the H-2D region. J Exp Med. 1986;163:620–631. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.3.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez M, Leibowitz J L, Lampert P W. Persistent infection of oligodendrocytes in Theiler’s virus-induced encephalomyelitis. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:426–433. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez M, Leibowitz J L, Powell H C, Lampert P W. Neonatal infection with the Daniel’s strain of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus. Lab Invest. 1983;49:672–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez M, Quddus J. Effect of cyclosporin A, silica quartz dust, and protease inhibitors on virus-induced demyelination. J Neuroimmunol. 1986;13:159–174. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(86)90062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roos R P, Firestone S, Wollmann R, Variakojis D, Arnason B G. The effect of short term and chronic immunosuppression on Theiler’s virus demyelination. J Neuroimmunol. 1982;2:223–234. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(82)90057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roos R P, Stein S, Ohara Y, Fu J L, Semle B L. Infectious cDNA clones of the DA strain of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus. J Virol. 1989;63:5492–5496. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5492-5496.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roos R P, Stein S, Routbort M, Senkowski A, Bodwell T, Wollmann R. Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus neutralization escape mutants have a change in disease phenotype. J Virol. 1989;63:4469–4473. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4469-4473.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato S, Zhang L, Kim J, Jakob J, Grant R A, Wollmann R, Roos R P. A neutralization site of DA strain of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus important for disease phenotype. Virology. 1996;226:327–337. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Theiler M. Spontaneous encephalomyelitis of mice. A new virus disease. Science. 1934;80:122–123. doi: 10.1126/science.80.2066.122-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wada Y, Pierce M L, Fujimami R S. Importance of amino acid 101 within capsid protein VP1 for modulation of Theiler’s virus-induced disease. J Virol. 1994;68:1219–1223. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.1219-1223.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zurbriggen A, Thomas C, Yamada M, Roos R P, Fujinami R S. Direct evidence of a role of amino acid 101 of VP-1 in central nervous system disease in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus infection. J Virol. 1991;65:1929–1937. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1929-1937.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zurbriggen A, Yamada M, Thomas C, Fujinami R S. Restricted virus replication in the spinal cords of nude mice infected with a Theiler’s virus variant. J Virol. 1991;65:1023–1030. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.2.1023-1030.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]