Abstract

Introduction

Since late 2019, COVID-19 has had a catastrophic impact on public health. Ensitrelvir, a new antiviral targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease, has reduced viral replication and disease severity. This meta-analysis and systematic review assessed Ensitrelvir’s efficacy and safety in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 symptoms.

Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed (Medline), Scopus, Embase, and CENTRAL up to July 2024 to retrieve randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing Ensitrelvir to placebo in adults with mild to moderate, RT-PCR–confirmed COVID-19. Outcomes were assessed at standardized time points, with viral RNA measured at day 4. Mean differences (MD) for continuous outcomes and risk ratios (RR) for binary outcomes, both with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated using the Mantel–Haenszel random-effects model. Efficacy outcomes included SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA, while safety outcomes included HDL, triglycerides, bilirubin, AST, headache, diarrhea, TEAEs, TRAEs, serious TEAEs, and treatment discontinuation. The quality of the included RCTs was assessed with the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (ROB2) tool.

Results

The analysis included six RCTs with 2,793 participants: 1,860 received Ensitrelvir and 933 were given a placebo. Ensitrelvir gave significant results for reduced viral RNA levels of SARS-CoV-2 [MD: − 1.35; 95% CI − 1.58 to − 1.13; p < 0.01] and the incidence of lower cholesterol levels [RR: 8.83; 95% CI 4.05 to 19.27; p < 0.01] compared to the placebo group. However, it was associated with increased risks of decreased HDL levels, elevated triglycerides, increased bilirubin, more headaches, and a higher overall occurrence of treatment-emergent adverse events.

Conclusion

Ensitrelvir effectively reduces viral load in COVID-19 patients, but its safety profile raises concerns due to significant adverse effects. The benefits must be carefully weighed against the risks, and further research is needed to confirm its role in treatment and to find ways to mitigate these adverse effects.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s15010-025-02582-0.

Keywords: Covid-19, Ensitrelvir, Pandemic, Meta-analysis

Introduction

COVID-19 is a viral, infectious disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. SARS-CoV-2 primarily targets the respiratory system, yet may also affect other organs due to its systemic nature. The disease was first identified in Wuhan, China, in late 2019 and has caused a global pandemic, leading to lockdowns globally, dramatically affecting public health and economies worldwide [1]. As of mid-2024, COVID-19 has caused significant morbidity and mortality globally, with over 760 million confirmed cases and more than 6.9 million deaths [2]. This disease manifests with a broad range of symptoms, from mild respiratory issues to severe conditions such as pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The pathophysiology involves a hyperactive immune response, leading to elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines like IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, contributing to the disease's severity [1]. Individuals older than 60 years and those with pre-existing conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease are at higher risk for severe illness and mortality [3]. Apart from high-risk populations, the pandemic has also placed an immense strain on healthcare systems and the general population, with significant impacts on mental health, including increased anxiety, depression, and social isolation [4].

Current treatment strategies for mild to moderate COVID-19 primarily include supportive care, antiviral drugs, and immunomodulatory therapies. Remdesivir, an antiviral agent, has received emergency use authorization in several countries, while dexamethasone, a corticosteroid, has shown efficacy in reducing mortality in severe cases [5, 6]. Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), an oral antiviral combination, is also approved for mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in high-risk patients, demonstrating significant reductions in hospitalization and mortality, particularly during the Delta variant phase. However, Paxlovid requires co-administration of ritonavir, which may lead to drug-drug interactions, complicating its use in patients with comorbidities or polypharmacy [7]. Moreover, these treatments have limitations and may be associated with side effects such as gastrointestinal issues and immune suppression, which could lead to complications [8]. The search for additional practical and safe therapies continues, especially for patients with less severe forms of the disease who may benefit from early and targeted interventions.

Ensitrelvir, a novel antiviral agent, targets the replication of SARS-CoV-2 by inhibiting the main protease (Mpro) enzyme, which is essential for viral replication. This mechanism reduces viral load and alleviates disease severity [9, 10]. Though these preliminary trials show potential benefits of using Ensitrelvir, concerns remain over its efficacy and safety. Previous randomized clinical trials have been limited by smaller sample sizes and shorter follow-up periods, which may lead to inconsistencies in results. Therefore, our meta-analysis and systematic review aim to address this gap by systematically reviewing and analyzing available clinical trial data on Ensitrelvir, thoroughly assessing its efficacy and safety.

Methods

This meta-analysis and systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11]. The protocol for this meta-analysis was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the reference number CRD42024572306.

Data sources and search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed across Cochrane CENTRAL, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Google Scholar databases from inception to July 2024. The search strategy imposed no restrictions on publication status or language. Additionally, bibliographies of relevant review articles and databases of unpublished literature were searched to ensure that no relevant studies, including those from white or gray literature, were omitted. The search terms included relevant PubMed MeSH terms and related keywords, such as (Ensitrelvir OR S-217622 OR 3CL protease inhibitor) AND (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR). The detailed search strategy is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Study selection and eligibility criteria

Retrieved studies were imported into EndNote reference library, version X8.1 (Clarivate Analytics), and duplicates were removed. Two authors (ZH and SS) independently reviewed and selected studies. Discrepancies were resolved by a third author (SA). The Population, Intervention, Control, and Outcomes (PICO) format for systematic reviews was used to define the inclusion criteria, with 'P' representing patients with COVID-19 positivity, 'I' representing Ensitrelvir, 'C' representing placebo, and 'O' representing the several outcomes defined below. Studies that met all of the following criteria were included in the meta-analysis and systematic review: (1) Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), (2) comparing Ensitrelvir to placebo, (3) in a population of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 symptoms, and (4) reporting any of the prespecified outcomes of interest. Only studies explicitly identified as randomized controlled trials in study design descriptions were included. These RCTs compared Ensitrelvir to placebo in adults (≥ 18 years) with mild-to-moderate, RT-PCR-confirmed COVID-19.

We excluded preprints and included only peer-reviewed, published randomized controlled trials. Studies were excluded if they employed different study designs, such as observational studies, non-randomized studies, review articles, case reports, or editorials. Observational studies were excluded to minimize confounding and bias inherent in non-randomized designs, ensuring higher internal validity of the findings through RCTs. Additionally, studies with overlapping populations, those not reporting relevant outcomes, and those involving patients with exacerbated COVID-19 or other serious systemic comorbidities were also excluded.

Serious systemic comorbidities were defined as conditions increasing COVID-19 severity risk, such as uncontrolled diabetes, severe cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, or immunosuppression. Studies with populations predominantly having these conditions were excluded to ensure homogeneity and maintain a focus on mild-to-moderate COVID-19.Key endpoints include a decrease in SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA on day four. Safety endpoints include liver enzymes (bilirubin, AST), lipid abnormalities (HDL, triglycerides), and adverse events (TEAEs, TRAEs) that were monitored during treatment.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted independently by two authors (ZH and SS) on a pre-piloted Microsoft Excel sheet based on a subset of studies to refine the extraction form before complete data collection, with discrepancies resolved through consultation with a third author (SA). Extracted data included study labels, publication year, study design, location, patient population, baseline characteristics (age, sex, disease duration), and efficacy and safety endpoints. The efficacy endpoints evaluated the impact on SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA levels, with safety endpoints including various adverse events (AEs), including a decrease in blood high-density lipoproteins (HDL) and cholesterol levels, an increase in blood triglyceride levels, elevated bilirubin and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels, headache, diarrhea, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), serious TEAEs, and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation.

Quality assessment

The quality of the included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool 2.0 (RoB 2.0) [12]. The tool evaluates potential biases in domains such as selection, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting, with judgments categorized as 'Low', 'Some concerns' or 'High'. Two authors (SS and SA) independently performed the quality assessment, resolving disagreements through consensus. The certainty of evidence for primary efficacy (SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA levels) and safety outcomes (e.g., HDL decrease, TEAEs) was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. Two authors (SA, ZH) independently assessed the risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias (Supplementary Table 2).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan version 5.4; Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). The Mantel–Haenszel random-effects model was used to pool the outcomes from the studies. Mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes and Risk Ratio (RR) for binary outcomes, along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated. Statistical significance was defined as a p value ≤ 0.05. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Higgins I2 index, with values < 25%, 25–75%, and > 75% representing low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. In instances where heterogeneity exceeded 25%, a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed using a leave-one-out approach to identify the study contributing to significant heterogeneity.

Results

Study selection

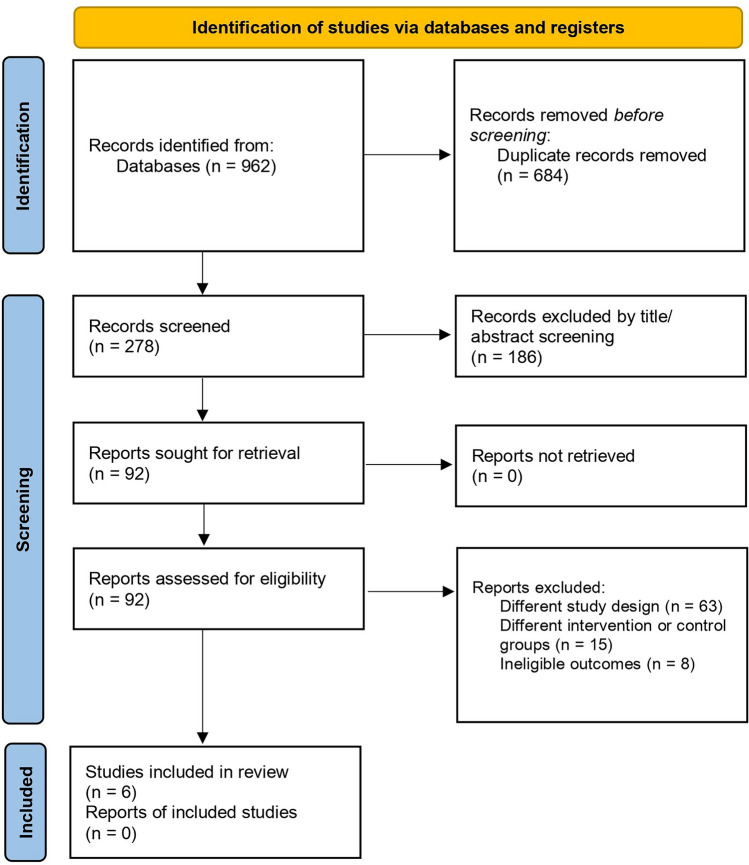

The preliminary literature search from databases yielded 962 results. After removing duplicates (n = 684), an initial screening was performed based on the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles, narrowing the selection to 92 articles. Further screening led to the exclusion of 63 articles due to different study designs, 15 due to different intervention or control groups, and 8 due to ineligible outcomes. Ultimately, 6 trials met the predefined inclusion criteria and were included in this meta-analysis [10, 13–17]. The search and screening process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The 2020 preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart

Study and patient characteristics

A total of 2,793 patients were included in the six RCTs, with 1,860 in the Ensitrelvir group and 933 in the placebo group. Among these participants, 1,510 were male, and 1,283 were female. The studies included 24 participants identified as White and 2,362 as Asian. The mean age of the patients was 37.0 ± 11.5 years. Across the included studies, the mean proportion of male participants was approximately 55.8%, with values ranging from 50.0 to 76.5%, indicating a slight male predominance in the study populations. The studies included the assessment of the Delta variant, the Omicron BA.1 lineage (21K), the Omicron BA.2 lineage (211), and unidentified, unknown, or recombinant variants. Efficacy outcomes, including SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA levels, were assessed at day 4 post-treatment, while safety outcomes, such as treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), lipid abnormalities (e.g., HDL, triglycerides), and liver enzyme elevations (e.g., bilirubin, AST), were monitored up to day 28 across all included studies. The baseline characteristics and outcomes of the studies included are detailed in Tables 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | Author names | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mukae et al. 2023 |

Shimizu et al. 2023 |

Ohmagari et al. 2024 |

|||||||

| 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | |

| Total population | 114 | 111 | 116 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 194 | 189 | 189 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 61 (53.5) | 66 (56.9) | 72 (64.9) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 109 (56.2) | 110 (58.2) | 103 (54.5) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 35.6 (13.5) | 35.3 (13.1) | 37.3 (12.6) | 33.8 (3.3) | 38.1 (8.1) | 33.5 (7.1) | 37.9 (12.0) | 40.9 (13.4) | 38.6 (13.0) |

| Height (cm) mean (SD) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 167.6 (11.2) | 171.8 (7.7) | 169.9 (9.9) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Weight (kg) mean (SD) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 70.6 (11.1) | 73.5 (12.4) | 68.4 (6.2) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| BMI (kg/m2) mean (SD) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 24.7 (1.3) | 24.7 (2.6) | 23.9 (2.9) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Race, n (%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | White: 8 (100.0) | White: 8 (100.0) | White: 8 (100.0) | Asian:193 (99.5) | Asian:189 (100.0) | Asian:188 (99.5) |

| COVID-19 vaccination history, n (%): | |||||||||

| ≥ 1 vaccination | 97 (85.1) | 97 (83.6) | 97 (87.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| ≥ 2 vaccination | 94 (82.5) | 96 (82.8) | 95 (85.6) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| ≥ 3 vaccination | 3 (2.6) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Overall | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 178 (91.8) | 173 (91.5) | 174 (92.1) |

| SARS-CoV-2 variant, n (%): | |||||||||

| 21I (Delta) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 21J (Delta) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| 21K (Omicron BA.1 lineage) | 114 (100.0) | 112 (96.6) | 110 (99.1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 53 (27.3) | 47 (24.9) | 50 (26.5) |

| 21L (Omicron BA.2 lineage) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 71 (36.6) | 68 (36.0) | 53 (28.0) |

| Unknown/unidentified/recombinant | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 53 (27.3) | 58 (30.7) | 63 (33.3) |

| Respiratory symptoms | |||||||||

| Stuffy or runny nose | 29 (25.4) | 34 (29.3) | 26 (23.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Sore throat | 65 (57.0) | 63 (54.3) | 54 (48.6) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Shortness of breath (difficulty breathing) | 8 (7.0) | 8 (6.9) | 1 (0.9) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cough | 48 (42.1) | 46 (39.7) | 49 (44.1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Total score of 12 COVID-19 symptoms, b mean (SD) | 9.9 (5.0) | 9.3 (4.5) | 8.6 (3.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Patients with fever (body temperature ≥ 37.0 °C), n (%) | 45 (39.5) | 39 (33.6) | 30 (27.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| SARSCoV-2 test, negative | N/A | N/A | N/A | 8 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA level (log10 copies/mL), mean (SD) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6.43 (1.26) | 6.56 (1.15) | 6.18 (1.48) |

| Prior acetaminophen use | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 45 (23.2) | 56 (29.6) | 44 (23.3) |

| Any risk factor for severe disease | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 58 (29.9) | 63 (33.3) | 66 (34.9) |

| Baseline characteristics | Author names | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yotsuyanag et al. 2022 |

Mukae et al. 2022 |

Shimizu et al. 2022 |

|||||||

| 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | |

| Total population | 603 | 595 | 600 | 16 | 14 | 17 | 8 | – | 3 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 318 (52.7) | 323 (54.3) | 311 (51.8) | 8 (50.0) | 8 (57.1) | 13 (76.5) | N/A | – | N/A |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 35.9 (12.7) | 35.9 (12.7) | 35.3 (12.6) | 38.8 (12.5) | 40.4 (10.7) | 38.0 (14.2) | N/A | – | N/A |

| Height (cm) mean (SD) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 181.01 (9.58) | – | 181.63 (7.28) |

| Weight (kg) mean (SD) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 74.68 (8.32) | – | 81.13 (3.23) |

| BMI (kg/m2) mean (SD) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 22.83 (2.91) | – | 24.40 (2.00) |

| Race, n (%) | Asian: 601 (99.7) | Asian: 593 (99.7) | Asian: 598 (99.7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 8 (100.0) | – | 3 (100.0) |

| COVID-19 vaccination history, n (%): | |||||||||

| ≥ 1 vaccination | 562 (93.2) | 551 (92.6) | 553 (92.2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | N/A |

| ≥ 2 vaccination | 554 (91.9) | 547 (91.9) | 545 (90.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | N/A |

| ≥ 3 vaccination | 284 (47.1) | 295 (49.6) | 283 (47.2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | N/A |

| Overall | N/A | N/A | N/A | 14 (87.5) | 12 (85.7) | 12 (70.6) | N/A | – | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 variant, n (%): | |||||||||

| 21I (Delta) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Delta (subvariant: N/A): 13 (81.3) | Delta (subvariant: N/A): 13 (92.9) | Delta (subvariant: N/A): 16 (94.1) | N/A | – | N/A |

| 21J (Delta) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | N/A |

| 21K (Omicron BA.1 lineage) | 131 (21.7) | 130 (21.8) | 115 (19.2) | Omicron (subvariant: N/A): 3 (18.8) | Omicron (subvariant: N/A): 1 (7.1) | Omicron (subvariant: N/A): 1 (5.9) | N/A | – | N/A |

| 21L (Omicron BA.2 lineage) | 401 (66.5) | 376 (63.2) | 407 (67.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | N/A |

| Unknown/unidentified/recombinant | 52 (8.6) | 64 (10.8) | 50 (8.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | N/A |

| Respiratory symptoms | |||||||||

| Stuffy or runny nose | 506 (86.1) | 468 (80.6) | 464 (80.0) | 6 (46.2) | 4 (33.3) | 4 (28.6) | N/A | – | N/A |

| Sore throat | 520 (88.4) | 522 (89.7) | 512 (88.3) | 7 (53.8) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (21.4) | N/A | – | N/A |

| Shortness of breath (difficulty breathing) | 170 (28.9) | 158 (27.1) | 142 (24.5) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A | N/A | |

| Cough | 518 (88.1) | 512 (88.0) | 518 (89.3) | 7 (53.8) | 7 (58.3) | 6 (42.9) | N/A | N/A | |

| Total score of 12 COVID-19 symptoms, b mean (SD) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Patients with fever (body temperature ≥ 37.0 °C), n (%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| SARSCoV-2 test, negative | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 8 (100.0) | 3 (100.0) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA level (log10 copies/mL), mean (SD) | 6.83 (1.05) | 6.73 (1.08) | 6.77 (1.07) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Prior acetaminophen use | 216 (35.8) | 191 (32.1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Any risk factor for severe disease | 174 (28.9) | 167 (28.1) | 152 (25.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

Table 2.

Safety outcomes

| Safety outcomes | Author names | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mukae et al. 2023 |

Shimizu et al. 2023 |

Ohmagari et al. 2024 |

Yotsuyanag et al. 2022 |

Mukae et al. 2022 |

Shimizu et al. 2022 |

|||||||||||||

| 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | |

| Patients with any TEAE | 48/140 (34.3%) | 60/140 (42.9%) | 44/141 (31.2%) | 7/8 (87.5%) | 7/8 (87.5%) | 3/8 (37.5%) | 88/201 (43.8%) | 115/202 (56.9%) | 43/201 (21.4%) | 267/604 (44.2%) | 321/599 (53.6%) | 150/605 (24.8%) | 11/21 (52.4%) | 16/23 (69.6%) | 9/24 (37.5%) | – | 8/8 (100%) | 1/3 (33.3%) |

| Patients with any serious TEAE | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.4%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | – | N/A | N/A |

| Patients with any treatment-related AE | 19 (13.6%) | 31 (22.1%) | 7 (5.0%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 47 (23.4) | 75 (37.1) | 14 (7.0) | 148 (24.5%) | 217 (36.2%) | 60 (9.9%) | 5 (23.8%) | 10 (43.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | – | N/A | N/A |

| Patients with TEAEs leading to death | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | – | N/A | N/A |

| Patients with TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation | 2 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.7%) | 6 (1.0%) | 2 (3.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | – | N/A | N/A |

| Blood triglycerides increase | 1 (0.7%) | 9 (6.4%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0/8 (0.0%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 0/8 (0.0%) | 14 (7.0%) | 22 (10.9%) | 9 (4.5%) | 49 (8.1%) | 74 (12.4%) | 32 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (13.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | – | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HDL decrease | 31 (22.1%) | 40 (28.6%) | 5 (3.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 7 (87.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 61 (30.3%) | 91 (45.0%) | 4 (2.0%) | 188 (31.1%) | 231 (38.6%) | 23 (3.8%) | 3 (14.3%) | 12 (52.2%) | 2 (8.3%) | – | 7/8 (87.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increase | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (2.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 14 (2.3) | 8 (1.3%) | 11 (1.8%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (1.4%) | 3 (2.1%) | 1 (0.7%) | 2 (25.0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 6 (3.0%) | 4 (2.0%) | 6 (1.0%) | 9 (1.5%) | 12 (2.0%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | 4/8 (50%) | 1/3 (33.3%) |

| Rash | 2 (1.4%) | 1 (0.7%) | 3 (2.1%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Back pain | 1 (0.7%) | 3 (2.1%) | 1 (0.7%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | N/A | N/A |

| Headache | 3 (2.1%) | 3 (2.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (37.5%) | 2 (25.0%) | 5 (2.5%) | 11 (5.4%) | 3 (1.5%) | 13 (2.2%) | 20 (3.3%) | 14 (2.3%) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (13.0) | 0 (0.0%) | – | 2/8 (25%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Nausea | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 7 (3.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7 (3.5%) | 15 (7.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 36 (6.0%) | 56 (9.3%) | 6 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | – | N/A | N/A |

| Alanine Aminotransferase Increased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (8.3%) | – | N/A | N/A |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase Increased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4 (0.7%) | 9 (1.5%) | 12 (2.0%) | 4 (0.7) | 9 (1.5%) | 12 (2.0%) | – | N/A | N/A |

| Blood cholesterol decreased | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 8 (4.0%) | 7 (3.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 20 (3.3%) | 28 (4.7%) | 3 (0.5%) | 20 (3.3%) | 28 (4.7%) | 3 (0.5%) | – | N/A | N/A |

Table 3.

Efficacy outcomes

| Author names | Year | Efficacy outcomes | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time-weighted average change from baseline up to 120 hours in the total score of 12 COVID-19 symptoms | SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA level (day4) | Time to first improvement in COVID-19 symptoms | Time to first negative SARS-CoV-2 viral titer | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) change from baseline | LS mean (SE) change from baseline assessed by ANCOVA | LS mean (SE) difference in change from baseline versus placebo | LS mean (SE) change from baseline assessed by ANCOVA | Difference from placebo | Unit: (median [95% CI] hours) | Median (h) | Difference from placebo | ||||||||||||||||||

| 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | 125 mg | 250 mg | Placebo | ||

| Mukae et al. | 2023 | − 5.95 (47.56) | − 5.42 (43.77) | − 4.92 (38.59) | − 5.37 (0.24) | − 5.17 (0.23) | − 5.12 (0.24) | − 0.24 (0.30), (95% CI, − 0.83 to 0.34); p-value: 0.4171 | − 0.04 (0.29) (95% CI, − 0.62 to 0.53); p-value: 0.8806 | Referent | − 2.58 [1.30] | − 2.49 [1.30] | − 1.28 [1.30] | − 1.30; 95% CI: − 1.57 to − 1.03; p < 0.0001 | − 1.21; (95% CI, − 1.48 to − 0.94); p < 0.0001 | Referent | 28.0 [21.5–36.6] | 27.8 [24.6–40.0] | 36.6 [28.0–40.8] | 47.7 [95%CI 43.4, 61.0] | 47.4 [95%CI 42.8, 65.4] | 91.6 [95%CI 74.1, 109.7] | − 43.8 [− 57.2, − 26.9] p = < 0.0001 | − 44.1 [− 52.1, − 21.0] p = < 0.0001 | Referent |

| Shimizu et al. | 2023 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ohmagari et al. | 2024 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 38.3 (95%CI 21.8, 42.3) | 38.9 (95%CI 24.8, 43.2) | 66.7 (95%CI 62.0, 71.2) | − 28.3 (95%CI − 47.5, − 22.0) p = < 0.0001 | − 27.8 (95%CI − 45.5, − 21.6) p = < 0.0001 | Referent |

| Yotsuyanag et al. | 2022 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | − 2.48 (1.96) | − 2.49 (1.95) | − 1.01 (1.96) | − 1.47 (1.96) [95% CI: − 1.63 to − 1.31] p = < 0.001 | − 1.48 (1.96) [95%CI − ; 1.64 to − 1.32] p = < 0.001 | Referent | N/A | N/A | N/A | Median: 36.2 h; (95% CI, 23.4–43.2) | N/A | Median, 65.3 h; (95% CI, 62.0–66.8) | − 29.1 h; (95% CI, − 42.3 to − 21.1; p < 0.001) | N/A | Referent |

| Mukae et al. | 2022 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Mean (SD): − 2.42 [1.42] | Mean (SD): − 2.81 [1.21] | Mean (SD): − 1.54 [0.74] | − 0.88; (p = 0.0712) | − 1.27; (p = 0.0083) | Referent | N/A | N/A | N/A | 61.3 (38.0, 68.4) | 62.7 (39.2, 72.3) | 111.1 (23.2, 158.5) | − 48.4 (− 95.9, 28.5) p = 0.0205 | − 48.8 (− 96.7, 30.9) p = 0.0159 | Referent |

| Shimizu et al. | 2022 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Assessment of study quality

Four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were classified as “low risk” [10, 13, 14, 17], while two were identified as having "some concerns" due to concerns in the missing outcome data, measurement of outcomes and selection of reported results (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2) [15, 16]

Endpoints

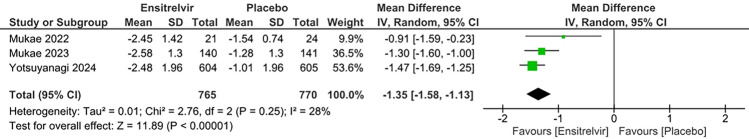

SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA levels

Three studies reported the change in SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA levels in the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups [10, 16, 17]. According to the pooled analysis shown in Fig. 2, there was a significant reduction in viral RNA levels favoring Ensitrelvir over placebo [MD: − 1.35; 95% CI − 1.58 to − 1.13; p < 0.01; I2 = 28%]. There was moderate heterogeneity among the studies, which was reduced to zero after leaving out Mukae 2022 [16]

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the change in SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA levels in the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups

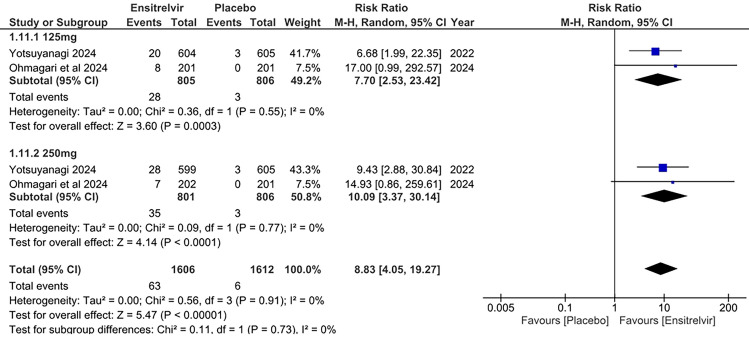

Decrease in blood cholesterol levels

Two studies reported a decrease in blood cholesterol levels as an outcome [10, 13]. Figure 3 illustrates a pooled analysis which showed significant results in the Ensitrelvir group for the decrease in blood cholesterol levels with the 125 mg dose [RR: 7.70; 95% CI 2.53 to 23.42; p < 0.01; I2 = 0%] and 250 mg dose [RR: 10.09; 95% CI 3.37 to 30.14; p < 0.01; I2 = 0%] compared to placebo. The overall analysis similarly gave significant results in the Ensitrelvir group compared to placebo [RR: 8.83; 95% CI 4.05 to 19.27; p < 0.01; I2 = 0%]. There was no heterogeneity among the studies, showing highly consistent results.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the decreased blood cholesterol levels in the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups

Decrease in blood high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels

Six studies examined the impact of Ensitrelvir at doses of 125 and 250 mg on blood HDL levels, comparing it to placebo [10, 13–17]. The pooled analysis in Fig. 4 demonstrated significantly higher risk for decrease in HDL levels with the 125 mg dose of Ensitrelvir [RR: 8.02; 95% CI 5.37 to 11.99; p < 0.01; I2 = 8%] and 250 mg dose [RR: 10.56; 95% CI 7.53 to 14.79; p < 0.01; I2 = 0%]. The combined analysis also followed the same trend, showing higher risk for reduction in HDL levels with Ensitrelvir treatment compared to placebo [RR: 9.25; 95% CI 7.25 to 11.81; p < 0.01; I2 = 1%]. The studies showed an overall low heterogeneity (I2) of 1%, reflecting very consistent results.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the decreased blood HDL levels in the Ensitrelvir and Placebo groups

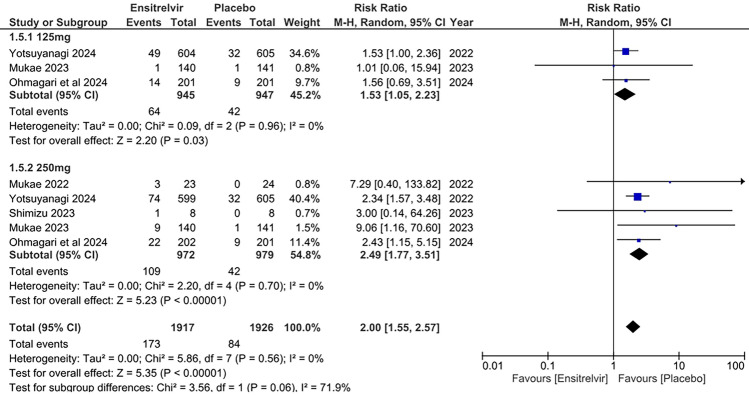

Increase in blood triglyceride levels

Five studies reported the effects of Ensitrelvir at two doses (125 and 250 mg) on blood triglyceride levels [10, 13, 14, 16, 17]. The pooled analysis presented in Fig. 5 showed significantly higher risk of increase in blood triglyceride levels for both 125 mg dose of Ensitrelvir [RR: 1.53; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.23; p = 0.03; I2 = 0%] and 250 mg dose [RR: 2.49; 95% CI 1.77 to 3.51; p < 0.01; I2 = 0%] as compared to placebo. The combined analysis indicated a similar pattern with a higher risk of increased blood triglyceride levels with Ensitrelvir compared to placebo [RR: 2.00; 95% CI 1.55 to 2.57; p < 0.01; I2 = 0%]. No heterogeneity was observed among the studies.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of the increased blood triglyceride levels in the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups

Increase in bilirubin levels

Three studies reported increased bilirubin levels as an outcome [10, 13, 16]. The pooled analysis in Fig. 6 showed significant risk of increase in bilirubin levels with Ensitrelvir treatment as compared to placebo, for both 125 mg dose [RR: 6.48; 95% CI 2.85 to 14.73; p < 0.01; I2 = 0%] and 250 mg dose [RR: 9.91; 95% CI 4.58 to 21.46; p < 0.01; I2 = 0%]. The combined analysis revealed similar findings [RR: 8.12; 95% CI 4.63 to 14.25; p < 0.01; I2 = 0%]. No heterogeneity was observed among the studies.

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of the increased bilirubin levels in the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups

Increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels

Two studies reported increased AST levels as an outcome [10, 16]. The pooled analysis in Fig. 7 showed a significantly reduced risk of Increased AST for 125 mg Ensitrelvir [RR: 0.37; 95% CI 0.13 to 1.02; p = 0.05; I2 = 0%] compared to placebo. But there was no difference between Ensitrelvir 250 mg dose [RR: 0.72; 95% CI 0.32 to 1.62; p = 0.43; I2 = 0%] and placebo. The overall analysis indicated no significant difference in the risk of increased AST levels with Ensitrelvir compared to placebo [RR: 0.56; 95% CI 0.30 to 1.05; p = 0.07; I2 = 0%]. No heterogeneity was observed among the studies.

Fig. 7.

Forest plot of the increased AST levels in the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups

Headache

Six studies investigated the incidence of headaches in patients consuming Ensitrelvir at different doses (125 and 250 mg) compared to placebo [10, 13–17]. The pooled analysis in Fig. 8 demonstrated no significant difference in headache occurrence between the 125 mg dose of Ensitrelvir [RR: 1.15; 95% CI 0.63 to 2.10; p = 0.65; I2 = 0%] and placebo. However, the 250 mg dose was associated with a significantly higher incidence compared to placebo [RR: 1.90; 95% CI 1.12 to 3.25; p = 0.02; I2 = 0%] The overall analysis found a significant increase in the risk of headache for those taking Ensitrelvir compared to placebo [RR: 1.52; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.27; p = 0.04; I2 = 0%]. No heterogeneity was observed among the studies.

Fig. 8.

Forest plot of the incidence of headaches in the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups

Diarrhea

Five studies reported the incidence of diarrhea in Ensitrelvir at different doses (125 and 250 mg) compared to placebo [10, 13–15, 17]. The pooled analysis in the Fig. 9 showed no significant difference in risk of diarrhea between Ensitrelvir and placebo for both 125 mg dose [RR: 0.79; 95% CI 0.35 to 1.81; p = 0.58; I2 = 12%] and 250 mg dose [RR: 1.10; 95% CI 0.57 to 2.12; p = 0.54; I2 = 0%]. The overall analysis combining both doses followed the same trend [RR: 0.92; 95% CI 0.56 to 1.50; p = 0.73; I2 = 0%]. No overall heterogeneity was observed among the studies.

Fig. 9.

Forest plot of the incidence of diarrhea in the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs)

Six studies reported the incidence of TEAEs associated with Ensitrelvir at different doses (125 and 250 mg) [10, 13–17]. According to the pooled analysis in Fig. 10, There was high risk of TEAEs with Ensitrelvir for both 125 mg dose [RR: 1.66; 95% CI 1.31 to 2.09; p < 0.01; I2 = 47%] and 250 mg dose [RR: 2.02; 95% CI 1.58 to 2.58; p < 0.01; I2 = 60%] compared to placebo. The overall effect similarly illustrated a significant increase in the risk of TEAEs with Ensitrelvir compared to placebo [RR: 1.83; 95% CI 1.54 to 2.17; p < 0.01; I2 = 59%]. An overall moderate heterogeneity was observed, which was reduced to 0% after leaving out Mukae 2023 (Supplementary Fig. 3) [17]

Fig. 10.

Forest plot of the TEAEs in the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups

Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs)

Four studies reported the TRAEs as an outcome [10, 13, 16, 17]. The pooled analysis in Fig. 11 showed significantly higher risk of TRAEs in patients taking Ensitrelvir compared to placebo; both 125 mg dose of Ensitrelvir [RR: 2.66; 95% CI 2.10 to 3.38; p < 0.01; I2 = 0%] and 250 mg dose [RR: 4.06; 95% CI 3.19 to 5.17; p < 0.01; I2 = 4%] demonstrated this effect. The overall analysis illustrated similar findings with a higher risk of TRAEs in the Ensitrelvir group [RR: 3.50; 95% CI 2.71 to 4.51; p < 0.01; I2 = 38%]. Moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 38%) was observed overall across the studies, which was reduced to zero after leaving out Yotsuyanagi [10]

Fig. 11.

Forest plot of the Treatment-related AEs in the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE)

Three studies reported serious TEAEs as an outcome [10, 13, 17]. The pooled analysis in Fig. 12 demonstrated no significant difference in the occurrence of serious TEAEs between patients taking Ensitrelvir and placebo. Both the 125 mg dose [RR: 0.48; 95% CI 0.06 to 3.72; p = 0.48; I2 = 0%] and the 250 mg dose [RR: 0.71; 95% CI 0.10 to 5.14; p = 0.73; I2 = 19%] of Ensitrelvir supported this effect. The overall analysis similarly indicated no significant difference in the risk of serious TEAEs with Ensitrelvir compared to placebo [RR: 0.60; 95% CI 0.16 to 2.31; p = 0.46; I2 = 0%]. No overall heterogeneity was observed among the studies.

Fig. 12.

Forest plot of the serious TEAEs in the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups

Adverse events (AEs) leading to treatment discontinuation

Three studies reported AEs that led to treatment discontinuation as an outcome [10, 13, 17]. The combined analysis in Fig. 13 revealed no significant difference between the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups regarding AEs leading to treatment discontinuation for both the 125 mg dose [RR: 2.58; 95% CI 0.67 to 9.86; p = 0.17; I2 = 0%] and the 250 mg dose [RR: 4.37; 95% CI 0.82 to 13.85; p = 0.09; I2 = 0%]. However, the overall analysis indicated a significantly higher risk of AEs leading to treatment discontinuation with Ensitrelvir compared to placebo [RR: 2.93; 95% CI 1.11 to 7.75; p = 0.03; I2 = 0%]. No heterogeneity was observed among the studies.

Fig. 13.

Forest plot of the AEs leading to treatment discontinuation in the Ensitrelvir and placebo groups

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Ensitrelvir in patients with COVID-19. Our findings demonstrate that Ensitrelvir significantly reduces SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA levels compared to placebo, suggesting its potential antiviral efficacy. However, the drug was associated with a higher risk of decreased blood HDL levels, increased triglyceride and bilirubin levels, and treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs). No significant differences were observed in the incidence of diarrhea, serious treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), or adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation. However, there was a higher overall risk of TEAEs and headaches, especially at the 250 mg dose. The findings generally show consistent results.

The significant reduction in SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA levels with Ensitrelvir aligns with the proposed antiviral mechanism of the drug, which acts as a 3-chymotrypsin-like protease inhibitor, the main protease found in coronaviruses. The consistent effect across studies suggests a robust antiviral activity [16, 18]. Notably, the pooled analysis for viral RNA levels showed moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 28%), which was reduced to zero after excluding Mukae 2022, indicating that this study significantly influenced the favorable efficacy outcome [16]. Mukae 2022 reported a larger effect size for viral RNA reduction, potentially due to factors such as its study population (e.g., predominantly Asian patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19), dosing regimen (e.g., 125 mg or 250 mg Ensitrelvir), or timing during the Omicron variant wave [16]. This antiviral activity is comparable to that of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), an approved oral antiviral for mild-to-moderate COVID-19, which also inhibits the SARS-CoV-2 main protease [19]. However, Ensitrelvir offers potential advantages over Paxlovid. As a single-agent therapy, Ensitrelvir eliminates the need for ritonavir, which is associated with significant drug-drug interactions, particularly in patients with comorbidities or those on multiple medications [20]. This simpler administration profile may improve patient adherence and broaden applicability, especially in outpatient settings.

Similarly, a study conducted on the efficacy and safety of Ensitrelvir in treating COVID-19 from February 10 to July 10, 2022, with a 28-day follow-up period, at 92 institutions in Japan, Vietnam, and South Korea has shown promising results where it demonstrated significant efficacy by reducing the median time to symptom resolution by approximately one day compared to placebo. [10]

However, it is essential to consider the limitations of viral load reduction as a sole surrogate marker for clinical outcomes. Previous clinical trials of oral antivirals for COVID-19, molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir, conducted during the Delta variant phase in unvaccinated high-risk adults, showed a reduction in hospitalization and death [21, 22]. However, with COVID-19 vaccinations and the emergence of the Omicron variant, these endpoints are less applicable since studies have indicated a lower risk of severe outcomes with Omicron compared to Delta, [23], and community-based research suggests limited antiviral effectiveness in vaccinated, high-risk adults or those infected with Omicron [24]. It must be noted that studies conducted on symptomatic relief as an endpoint are guided by the FDA's 2020 recommendation to implement patient-reported outcomes for measuring COVID-19 symptoms in drug trials [25]. The phase 2/3 EPIC-SR study tested ritonavir-boosted nirmatrelvir for symptom alleviation but found no significant difference [26]. However, the SCORPIO-SR study demonstrated Ensitrelvir 's effectiveness in resolving COVID-19 symptoms, regardless of risk factors. Ensitrelvir showed symptom relief and virus reduction benefits for mild to moderate cases. Further trials, including SCORPIO-HR and STRIVE, [27, 28] and a pediatric study, are underway to validate its efficacy across different patient groups. While both nirmatrelvir and Ensitrelvir aim to alleviate COVID-19 symptoms, differing outcomes in symptom relief may stem from differences in trial design, patient populations, timing of administration, and pharmacokinetics. For instance, Ensitrelvir's single-agent nature and distinct protease-binding profile might contribute to the more rapid symptom resolution observed in specific trials.

The findings of this meta-analysis suggest that Ensitrelvir has antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2, where RNA load has decreased. While Ensitrelvir significantly reduces SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA levels, its clinical significance remains uncertain, particularly for lowering hospitalization or mortality. Viral load reduction may not always translate to clinical benefits, as seen with molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir in vaccinated or Omicron-infected populations. [21, 22, 24, 26]. Moreover, the significant safety concerns outweigh the potential benefits based on the current evidence. The drug was associated with a significantly increased risk of several adverse events, including lipid abnormalities and liver enzyme elevations. These findings highlight the potential for metabolic disturbances and hepatotoxicity with Ensitrelvir use. While the incidence of serious adverse events was not significantly increased, the overall adverse event profile is unfavorable. Contrastingly, Yotsuyanagi et al. demonstrate that no treatment-related serious adverse events were reported [10].While Ensitrelvir’s single-agent formulation and preliminary efficacy in vaccinated or Omicron-infected patients are promising, its unfavorable adverse event profile limits claims of superiority over Paxlovid.

Our meta-analysis has multiple limitations. Firstly, only 6 studies were included, which limits the accuracy of our findings, and they were only RCTs, excluding potentially valuable insights from non-randomized studies, including observational studies and case reports, which could offer broader context or reveal findings not captured by RCTs alone. Furthermore, the predominance of Asian patients limits the generalizability of our findings to other racial and ethnic groups, as differences in genetics, comorbidities, or healthcare settings may influence Ensitrelvir’s efficacy and safety profiles. Incorporating data from a broader range of study designs could offer more comprehensive insights. Furthermore, despite efforts to mitigate publication bias, relying on published literature introduces an element of publication bias, which indicates the need to conduct further trials on the drug rather than solely relying on the published literature to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the drug. Expanding the search to include unpublished data from trial registries could also improve the robustness of the findings. Additionally, the variability in how efficacy and safety endpoints are reported potentially contributes to heterogeneity between studies, which could be mitigated by establishing standardized reporting guidelines for these outcomes across studies. Our meta-analysis also focused on specific adverse events and the limited literature published. Thus, it may not have captured the full spectrum of potential side effects, highlighting the importance of further research. Lastly, relying on the Cochrane RoB tool may be open to subjective interpretation, which could be reduced by having multiple independent reviewers assess each study and reach a consensus on any disagreements.

The role of Ensitrelvir in the treatment algorithm remains uncertain due to the limited available data and the significant safety concerns. However, our findings are encouraging and warrant further research. Further research is needed to identify patient subgroups who may benefit from Ensitrelvir and to develop strategies to mitigate the adverse effects. Until more data becomes available, Ensitrelvir should be approached with caution and careful risk–benefit assessment. Research should focus on evaluating the impact of Ensitrelvir on clinical endpoints such as hospitalization and mortality. The long-term adverse effects potentially associated with this drug must also be further explored to highlight its safety profile more comprehensively.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis and systematic review provide evidence for the antiviral efficacy of Ensitrelvir in reducing SARS-CoV-2 viral load. Still, its impact on hospitalization and mortality is unclear due to limited data. However, the drug's unfavorable safety profile, characterized by a significant increase in adverse events, limits its clinical utility. Further research is warranted to explore the potential benefits and risks of Ensitrelvir in specific patient populations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgements to declare.

Abbreviations

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- AEs

Adverse events

- HDL

High-density lipoproteins

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- TEAEs

Treatment-emergent adverse events

- TRAEs

Treatment-related adverse events

Author contributions

MZUH- Conceptualization, design, methodology, formal analysis, supervision, writing- original draft, writing-review and editing; SA- Conceptualization, design, methodology, formal analysis, supervision, writing- original draft, writing-review and editing; MSUS- methodology, formal analysis, writing- original draft; SAS- methodology, formal analysis, writing- original draft; AS- methodology, formal analysis, writing- original draft; MAA- methodology, formal analysis, writing- original draft; AAAB- methodology, formal analysis, writing- review and editing; LF- methodology, formal analysis, writing- review and editing; HS- Conceptualization, design, supervision, writing-review and editing; MD- Conceptualization, design, supervision, writing-review and editing; AG- Conceptualization, design, supervision, writing- original draft, writing-review and editing.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding to conduct the study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical compliance

No ethical approval was required for this study design, as all data were obtained from publicly available sources.

References

- 1.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–3. 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–42. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1775–6. 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27(4):601–15. 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):1813–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.null null. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693–704. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Marzolini C, Kuritzkes DR, Marra F, et al. Recommendations for the management of drug–drug interactions between the COVID-19 antiviral nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid) and comedications. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022;112(6):1191–200. 10.1002/cpt.2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1824–36. 10.1001/jama.2020.6019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Jackson CB, Mou H, et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike-protein D614G mutation increases virion spike density and infectivity. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6013. 10.1038/s41467-020-19808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yotsuyanagi H, Ohmagari N, Doi Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of 5-day oral Ensitrelvir for patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 the SCORPIO-SR randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.54991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366: l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohmagari N, Yotsuyanagi H, Doi Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of Ensitrelvir for asymptomatic or mild COVID-19: an exploratory analysis of a multicenter, randomized, phase 2b/3 clinical trial. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2024;18(6): e13338. 10.1111/irv.13338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimizu R, Sonoyama T, Fukuhara T, Kuwata A, Matsuo Y, Kubota R. A phase 1 study of Ensitrelvir fumaric acid tablets evaluating the safety, pharmacokinetics and food effect in healthy adult populations. Clin Drug Investig. 2023;43(10):785–97. 10.1007/s40261-023-01309-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimizu R, Sonoyama T, Fukuhara T, Kuwata A, Matsuo Y, Kubota R. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of the novel antiviral agent Ensitrelvir fumaric acid, a SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease inhibitor, in healthy adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66(10):e0063222. 10.1128/aac.00632-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukae H, Yotsuyanagi H, Ohmagari N, et al. A randomized phase 2/3 study of Ensitrelvir, a novel oral SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease inhibitor, in Japanese patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 or asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: results of the phase 2a part. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66(10):e0069722. 10.1128/aac.00697-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukae H, Yotsuyanagi H, Ohmagari N, et al. Efficacy and safety of Ensitrelvir in patients with mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019: the phase 2b part of a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 study. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(8):1403–11. 10.1093/cid/ciac933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nobori H, Fukao K, Kuroda T, et al. Efficacy of Ensitrelvir against SARS-CoV-2 in a delayed-treatment mouse model. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2022;77(11):2984–91. 10.1093/jac/dkac257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imran L, Zubair R, Mughal S, Shakeel R. Ritonavir-boosted nirmatrelvir and COVID-19 outcomes in the age of Omicron variant. Ann Med Surg. 2023;85(2):313–5. 10.1097/MS9.0000000000000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rauch S, Costacurta F, Schöppe H, et al. Highly specific SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) mutations against the clinical antiviral Ensitrelvir selected in a safe, VSV-based system. Antivir Res. 2024;231: 105969. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2024.105969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, et al. Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(6):509–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa2116044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, et al. Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(15):1397–408. 10.1056/NEJMoa2118542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auvigne V, Vaux S, Strat YL, et al. Severe hospital events following symptomatic infection with Sars-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta variants in France, December 2021-January 2022: a retrospective, population-based, matched cohort study. EClin Med. 2022;48: 101455. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butler CC, Hobbs FDR, Gbinigie OA, et al. Molnupiravir plus usual care versus usual care alone as early treatment for adults with COVID-19 at increased risk of adverse outcomes (PANORAMIC): an open-label, platform-adaptive randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10373):281–93. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02597-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Research C for DE and. Assessing COVID-19-related symptoms in outpatient adult and adolescent subjects in clinical trials of drugs and biological products for COVID-19 prevention or treatment. February 22, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/assessing-covid-19-related-symptoms-outpatient-adult-and-adolescent-subjects-clinical-trials-drugs. Accessed 26 Aug 2024.

- 26.Hammond J, Fountaine RJ, Yunis C, et al. Nirmatrelvir for vaccinated or unvaccinated adult outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(13):1186–95. 10.1056/NEJMoa2309003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Study Details | A study to compare S-217622 with placebo in non-hospitalized participants with COVID-19 | ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05305547. Accessed 26 Aug 2024.

- 28.Study Details | Strategies and treatments for respiratory infections & viral emergencies (STRIVE): Shionogi protease inhibitor (Ensitrelvir) | ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05605093. Accessed 26 Aug 2024.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.