Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) poses a significant global health threat that requires novel antimicrobials to combat this WHO-designated priority pathogen. In this study, we designed, synthesized and evaluated a series of unexplored trisindoline derivatives against MRSA, including multidrug-resistant (MDR) clinical isolates. The Structure Activity Relationship (SAR) analysis of the trisindolines indicated the importance of strategic substitutions in the trisindoline core for their anti-staphylococcal efficacy. Biocompatibility studies revealed a high safety profile for the active compounds across various mammalian cell lines. Furthermore, the derivatives displayed rapid bactericidal action, anti-biofilm efficacy, intracellular MRSA killing and combinatorial effect with vancomycin. Mechanistic studies revealed that these compounds disrupt MRSA cell integrity by influencing several membrane-related pathways. Finally, in vivo assessments of a lead trisindoline in an MRSA-induced systemic infection model demonstrated a significant reduction of bacterial load. Therefore, these trisindoline molecules may offer a promising therapeutic model for combating MRSA infections.

Subject terms: Biological techniques, Microbiology

Introduction

In this post-antibiotic era, drug-resistant pathogens unfortunately backstep the pace of novel drug discovery, as for the last 20 years no new antibiotics have been discovered1. The rapid surfacing of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens in the twenty-first century, especially in the clinical settings have become a foremost health concern2,3. Not many new-fangled group of antibiotics are accessible to brawl against and not many are in the pipeline for future improvement4. The current necessity in the healthcare system is to formulate novel antimicrobials using advanced strategies and improved drug designs for effective results. Hence, novel strategies with novel drug targets are instantly needed to affray against these drug-resistant pathogens to escape from the ‘pre-antibiotic era’ where infections caused almost one-third of the surveyed deaths every year2,5.

The superbug methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a commensal and opportunistic pathogen, forcing us to compete with its resistant nature. We unendingly mislay this evolutionary race as instant outbreaks occur in hospitals and clinical settings, at the community level and even in livestock1. MRSA typically causes severe skin and soft tissue infections3, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, mastitis, disruptive neutrophil functions6,7 and many more. The first embodiment report of the MRSA outbreak was published in 1961, immediately after 1 year of the introduction of methicillin into the clinical settings 8. MRSA is constantly impervious to the ages of β-lactam antibiotics4 and most of the other antibiotics including macrolides, clindamycin and fluoroquinolones, failed in this evolutionary race, hence flagged as superbug9. Despite being at the top-priority alarm, only six first-in-class anti-staphylococcal drugs have been approved in the last 20 years10. Lamentably, there is an alarming call to deal with this mounting issue, requiring novel ways, targets and compounds with different mode of actions to battle against this multidrug resistant-opposition4,6,9.

Heterocyclic compounds bear numerous probabilities and are often considered effective scaffolds for drug discovery11. Even 59% of the FDA approved drugs have heterocyclic compounds in their structural framework12,13. One gifted class of antibacterial is indole based derivatives, which unquestionably emerged as the most valuable pharmacophores and significant figures of pharmaceuticals and natural products4,14, dwell very important place in medical disclosures4,15,16. In particular, these derivatives are extensively known for drug-related properties with various pharmaceutical implications, such as antibacterial17, antifungal18 antiinflammatory, anticancer19, antitubercular, antitumor, antiproliferative, antioxidant, etc20. In the current ground, many of the accessible drugs have indole as their core source, including reserpine, vincristine, fumitremorgin B, tryptostatin A and tryptostatin B9.

Among these tryprostatin A, tryprostatin B, and vincristine are utilized as antibiotics for treating bacterial infections. Indole based derivatives mainly includes structurally modified indoles, indole-hybrids, bisindole derivatives, trisindoline derivatives and etc. Numerous types of indole derivatives have been reported for their antibacterial efficacy against diverse pathogens including MRSA. Such as, a novel group of indole-nitroimidazole compounds, such as compound 4b, exhibited strong antibacterial activity with MIC values as low as 1 µg/ml. These hybrids function by intercalating into MRSA DNA, binding penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP2a), and suppressing resistance related genes, showcasing a versatile mechanism of actions. Structural modifications on indole moiety were reported for prominent antibacterial potency against MRSA21. In bisindole amidines derivatives, amidine substitutions demonstrated the importance of side chain length, where shorter chains facilitate better interaction with bacterial membranes, having the MIC value of (2–16 µg/ml) against tested bacterial pathogens22. Innovative indole hybrid designs have proven highly effective against MRSA. Similarly, carbazole-indole hybrids are notable for their MIC values (~1 µg/ml), where the linker length between the indole and carbazole moieties directly influences potency23. Spirooxindole compounds exhibit a wide MIC range (1–100 µg/ml) against different pathogens24–26. Pyrazole-linked indoles are another promising class, with electron-withdrawing substituents (-Cl at C-4) yielding MIC values comparable to vancomycin (1 mg/ml), targeting essential DNA Gyrase27. Additionally, several bisindole derivatives, bis and tris indole alkaloids stand out for their exceptional antibacterial potency14,28–31. Several well-known targets were reported as antibacterial mechanism of the indole derivatives like DNA gyrases32, pyruvate kinases33, tyrosine kinases34, topoisomerases35, ftsZ36 and DNA polymerases37. Additionally, some membrane-disruptive antibacterial indole derivatives have also been reported38. Lately, trisindoline derivatives came into limelight when evaluated for their bioactivities39. Trisindolines are a fascinating class of nitrogen containing heterocyclic compounds characterized by an isatin core linked to two indole moieties, which provide structural diversity and remarkable diverse biological activities including, antimicrobial40, antifungal40, anticancer41,42, spermicidal43, antitubercular44 and anticonvulsant40 properties39,45. These compounds have gained significant attention as potential antibacterial agents, particularly for combating different bacterial pathogens. Trisindolines have been isolated from natural sources such as marine bacteria, including Vibrio sp. and Shewanella piezotolerans, as well as marine sponges like Discodermia calyx. Due to their limited natural abundance several synthetic strategies were explored to produce them efficiently and in sufficient quantities39. Among the various methods explored, acid-catalyzed reactions between indoles and isatins have proven most effective, with catalysts such as sulfuric acid, montmorillonite K-10, tungstic acid, and p-toluenesulfonic acid offering high yields and broad substrate compatibility. The Structure Activity Relationships (SAR) of trisindolines revealed that their antibacterial efficacy is highly dependent on structural modifications. Substituents on the indole or isatin moieties play a critical role in determining the antibacterial activity. Electron-donating groups (EDGs) on the indole rings enhance reactivity, while electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs) improve antibacterial potency by facilitating stronger interactions with bacterial targets. Furthermore, symmetrical trisindolines, where the two indole units are identical, generally display superior antibacterial activity compared to their unsymmetrical counterparts. Modifications to the isatin core, such as the incorporation of halogens or alkyl groups, have also been shown to significantly influence their efficacy, underlining the importance of this central structural motif39.

Trisindoline derivatives are emerging as promising candidates in the development of next-generation antimicrobial agents, particularly in the fight against MDR pathogens. Their structural versatility allows for extensive modifications, enabling the fine-tuning of their antibacterial properties. However, the journey from laboratory to clinical application is hindered by several challenges that need to be addressed to fully harness their potential. Strategically designed trisindoline derivatives focusing on their SAR is required to identify key functional groups that enhance efficacy, selectivity and reduce toxicity, as the initial studies are limited to only synthesis with antibacterial potential40,45–47. Additionally, the comprehensive in vitro and in vivo investigations of the trisindolines, their drug-likeness, pharmacological characteristics and precise mode of action (MOA) remain unexplored. However, a comprehensive approach including innovative designing of trisindolines, their in-depth in vitro and in vivo antibacterial analysis and meaningful insights into mechanistic details is of great importance, which might overcome the lacunas and limitations in the trisindoline medicinal chemistry.

To address existing limitations, we designed and synthesized a library of 15 trisindoline derivatives using diverse indole and isatin precursors. To ensure the synthesis process remained cost-effective, non-toxic, non-corrosive and environment friendly, we employed a clay-catalyzed condensation method using montmorillonite clay (K-10) as the catalyst48,49. The design of these trisindoline derivatives involved strategic substitutions in the indole and isatin residues to enhance antibacterial efficacy, improve selectivity, and minimize toxicity. These modifications are discussed in the subsequent SAR analysis. The synthesized trisindoline compounds underwent comprehensive evaluation for their efficacy against MRSA, a WHO-designated global priority pathogen. Assessments included in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo studies to provide a robust evaluation of their antibacterial potential. Biosafety profiles of the active compounds were examined in various mammalian cell lines and red blood cells (RBCs) to ensure their safety for potential therapeutic use. Additionally, we investigated drug-likeness and ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion) properties using in silico analyses to predict their pharmacokinetic behavior. To further understand the MOA underlying MRSA inhibition, we conducted detailed in vitro analyses. Collectively, we believe this study advances the development of trisindolines as promising anti-MRSA agents, emphasizing their SAR, efficacy across multiple biological models, biosafety, drug-likeness and MOA.

Results

Chemistry

To synthesize a trisindoline library, we used montmorillonite K-10 as a reusable acid clay catalyst50. The one-pot synthesis routes and chemical structures of trisindolines were outlined in Scheme 1 and Fig. 1, respectively.

Scheme 1.

One-pot synthesis scheme of trisindoline derivatives 3a–o.

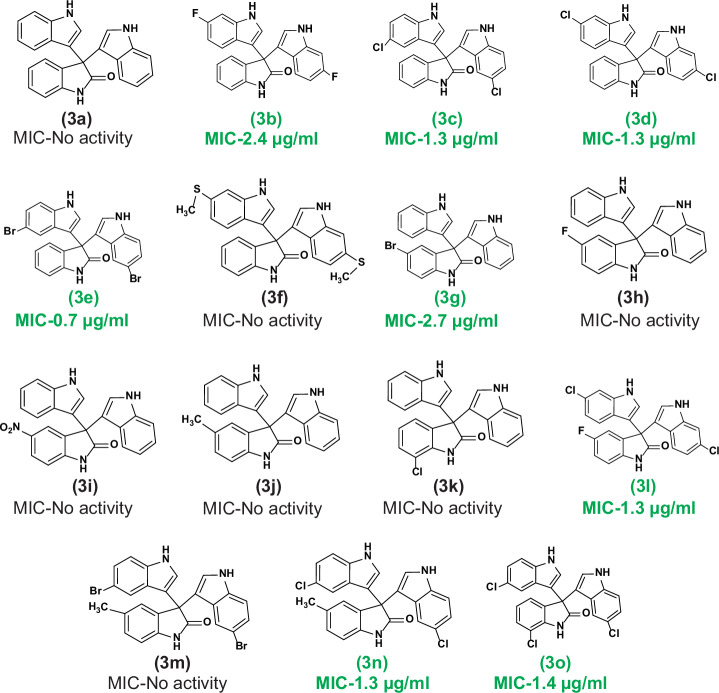

Fig. 1. Structures of the synthesized trisindoline derivatives.

Green color code signifies active trisindoline molecules along with the MIC (μg/ml) against MRSA.

The synthesis process involved the reaction of different isatin and indoles in a molar ratio of 1:2 with optimized catalyst’s (MK-10) concentration, temperature and time. Here in, the clay-catalyzed condensation of isatin core with indole molecule afforded trisindoline derivatives. Initially, the C-3 position of the isatin molecule gets activated in the presence of MK-10 and produces a resonating product. Next, the corresponding resonating structure led to the production of the first intermediate product by the nucleophilic attack of first indole molecule. Subsequently, deprotonation followed by protonation, afforded us second intermediate product. Further, dehydration of second intermediate produces α,β-unsaturated iminium ion which undergoes nucleophilic attack by another indole molecule, afforded third reaction intermediate. At last, re-aromatization of third intermediate afforded desired trisindoline molecule50,51. We have first synthesized the core molecule 3,3-di(indolyl)indolin-2-one (3a), by using unsubstituted indole and isatin. The synthesis of 3a was afforded in sufficient amount in 93.12% yield as colorless viscous liquid. Similarly, we have synthesized the other derivatives (3b–3o), using different substituted indoles and isatins as displayed in the Supplementary Information (Table S1). The design strategy of the trisindolines is explained in the SAR analysis section mentioned below. All the synthesized derivatives were fully characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, LCMS and HRMS spectral analysis (Supplementary Figs. S1–S15). The spectral details of compounds are provided in procedures.

Antimicrobial efficacy of synthesized trisindolines

On account of widespread applications of di(indolyl)indolin-2-ones in therapeutics, our efforts were mainly focused to appraise the antimicrobial potency of synthesized derivatives against MRSA, a WHO high-priority pathogen. Subsequently, we also assessed the in vitro susceptibility of the compounds against 21 MDR clinical isolates of S. aureus (SA-01 to SA-21), with clinical significance. The in vitro antibacterial potential (MIC and MBC) of the 15 trisindoline derivatives along with the standard drug vancomycin were portrayed in Table 1. Interestingly, we noticed that out of 15 derivatives, 8 compounds (3b, 3c, 3d, 3e, 3g, 3n, 3l and 3o) displayed prominent staphylococcal inhibition with the MIC values ranging from 0.7 µg/ml to 2.7 µg/ml. Subsequently, the concentration-dependent MRSA growth inhibition by the 8 positive trisindolines was also displayed in Supplementary Fig. S16. Unexpectedly, unsubstituted trisindoline (3a) possesses no activity against MRSA.

Table 1.

Antistaphylococcal susceptibility of synthesized trisindolines with their MIC, and MBC values

| S. No. | Compound code | IUPAC name | Anti-staphylococcal susceptibility values (µg/ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | MBC | |||

| 1 | 3a | 3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’one | >100 | >100 |

| 2 | 3b | 6,6”-difluoro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| 3 | 3c | 5,5”-dichloro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | 1.3 | 2.6 |

| 4 | 3d | 6,6”-dichloro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | 1.3 | 2.6 |

| 5 | 3e | 5,5”-dibromo-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | 0.7 | 1.6 |

| 6 | 3f | 6,6”-bis(methylthio)-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | >100 | >100 |

| 7 | 3g | 5’-bromo-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | 2.7 | 5.2 |

| 8 | 3h | 5’-fluoro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | >100 | >100 |

| 9 | 3i | 5’-nitro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | >100 | >100 |

| 10 | 3j | 5’-methyl-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | >100 | >100 |

| 11 | 3k | 7’-chloro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | >100 | >100 |

| 12 | 3l | 6,6”-dichloro-5’-fluoro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | 1.3 | 2.7 |

| 13 | 3m | 5,5”-dibromo-5’-methyl-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | >100 | >100 |

| 14 | 3n | 5,5”-dichloro-5’-methyl-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | 1.3 | 5.5 |

| 15 | 3o | 5,5”,7’-trichloro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one | 1.4 | 11.6 |

| 16 | Vancomycin | – | 2.1 | 4.4 |

However, significant antistaphylococcal activity was observed due to the substitution pattern at 5 and 6 position of indole molecules (compounds 3c and 3d). Substitution in the isatin ring showed no activity except one molecule (compound 3g). Additionally, these positive trisindolines showed significant bactericidal efficacy against MRSA with the MBC values ranging from 1.6 µg/ml to 11.6 µg/ml, represented in Table 1 and Supplementary data Fig. S17. Amazingly, these compounds also displayed prominent efficacy against MDR clinical isolates of S. aureus having the MIC values ranging between 0.6 µg/ml to ≤51.7 µg/ml (Table 2). Therefore, we have selected these 8 positive hits from synthesized trisindoline scaffolds for further investigation.

Table 2.

MIC values of the active trisindolines against MDR clinical isolates of S. aureus

| S. No. | MDR-clinical isolates | MIC of the active Trisindolines, µg/ml | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3b | 3c | 3d | 3e | 3g | 3l | 3n | 3o | ||

| 1 | SA-01 | 4.9 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 6.5 | 2.7 | 44.8 | 2.7 | 11.6 |

| 2 | SA-02 | 19.9 | 43 | >43 | 51.7 | 44.2 | 44.8 | 44.4 | 23.2 |

| 3 | SA-03 | 4.9 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 6.5 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 2.7 | 5.8 |

| 4 | SA-04 | >39.8 | 43 | >43 | >51.7 | >44.2 | >44.8 | >44.4 | >46.4 |

| 5 | SA-05 | >39.8 | >43 | >43 | >51.7 | >44.2 | >44.8 | >44.4 | >46.4 |

| 6 | SA-06 | 4.9 | 1.3 | 5.4 | 1.6 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 2.7 | 2.8 |

| 7 | SA-07 | 4.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 5.6 | 0.6 | 5.8 |

| 8 | SA-08 | >39.8 | >43 | >43 | >51.7 | >44.2 | >44.8 | >44.4 | >46.4 |

| 9 | SA-09 | >39.8 | 43 | 43 | 25.8 | 44.2 | 44.8 | 44.4 | 23.2 |

| 10 | SA-10 | >39.8 | >43 | >43 | >51.7 | >44.2 | >44.8 | >44.4 | >46.4 |

| 11 | SA-11 | 4.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 5.6 | 0.6 | 2.8 |

| 12 | SA-12 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 6.5 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 11.1 | 5.8 |

| 13 | SA-13 | 39.8 | 21.5 | 21.5 | 51.7 | 44.2 | 44.8 | 44.4 | 46.4 |

| 14 | SA-14 | 19.9 | 21.5 | 21.5 | 25.8 | 22.1 | 22.4 | 22.2 | 11.6 |

| 15 | SA-15 | >39.8 | >43 | >43 | >51.7 | >44.2 | >44.8 | >44.4 | >46.4 |

| 16 | SA-16 | 4.9 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 6.5 | 0.6 | 5.6 | 0.6 | 2.8 |

| 17 | SA-17 | 4.9 | 0.6 | 5.4 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 5.8 |

| 18 | SA-18 | 19.9 | 43 | 21.5 | 51.7 | 44.2 | >44.8 | >44.4 | 23.2 |

| 19 | SA-19 | 19.9 | 21.5 | 43 | 25.8 | 44.2 | 22.4 | 44.4 | 46.4 |

| 20 | SA-20 | >39.8 | 21.5 | 21.5 | 51.7 | 44.2 | 22.4 | 22.2 | 23.2 |

| 21 | SA-21 | 39.8 | 21.5 | 43 | 25.8 | 44.2 | 22.4 | 22.2 | 23.2 |

Antibacterial SAR of the active trisindolines

The SAR of the trisindoline derivatives as potential antibacterial agents was assessed using 14 compounds derived from their core structure (Fig. 1). These derivatives, categorized into three groups (excluding the core molecule 3a), were designed to evaluate the effects of structural diversity in the indoline-2-one (isatin) and indole moieties on their activity against MRSA. As highlighted in the introduction, indole plays a pivotal role in pharmaceuticals. Accordingly, we synthesized diverse trisindoline derivatives with various substitutions on indole and isatin rings (Fig. 1). Group 1: This group (3b–3f) consisted of derivatives with substituted indoles. The substitution sites (5, 5′ or 6, 6′ positions of the indole rings) showed a strong correlation with antibacterial potency.

Notably, the unsubstituted core molecule 3a exhibited no antibacterial activity, emphasizing the importance of substitutions. Halogenation emerged as a critical factor for high antibacterial efficacy. For example, fluorine substitution at the 5-position (3b) yielded a MIC of 2.4 µg/ml, while replacing fluorine with chlorine (3c) improved the MIC to 1.3 µg/ml. Bromine substitution (3e) further reduced the MIC significantly to 0.7 µg/ml, underscoring its superior antibacterial potential. Conversely, the addition of a dithiomethyl group (3f) at the same position resulted in no antibacterial activity, suggesting the specificity of halogenation in driving efficacy. Group 2: This group (3g–3k) comprised derivatives with substitutions only on the indoline-2-one moiety, leaving the indole ring unsubstituted.

Interestingly, most derivatives with nitro, methyl or fluorine substituents were inactive against MRSA. However, bromine substitution at the 5-position of indoline-2-one (3g) demonstrated activity with a MIC of 2.7 µg/ml, reinforcing the critical role of bromine substitution in antibacterial potency. Group 3: The final group (3l–3o) included derivatives with substitutions on both indoline-2-one and indole moieties. Among these, three derivatives (3l, 3n and 3o) exhibited significant antibacterial activity, while 3m showed no effect. The inactivity of 3m, which combined a methyl group on the indoline-2-one and bromine on the indole ring, might be attributed to the structural instability caused by the electron-donating effect of methyl substituents, which potentially destabilized the bromine. Interestingly, inactive derivatives from previous groups (e.g., 3h, 3j and 3k) exhibited satisfactory MICs when combined with 5- or 6-chloroindole substitutions, as seen in 3l, 3n, and 3o. In conclusion, halogenation, particularly bromine substitution at the 5- or 6-position of the indole moiety conjugated with the 3-position of indoline-2-one, emerged as a critical determinant of antibacterial efficacy. Bromine’s large surface area and structural stability may account for its superior activity against MRSA and MDR clinical isolates of S. aureus. These findings provide valuable insights into the structural requirements for designing potent trisindoline-based antibacterial agents.

Hemolysis assay with the active trisindolines

An antibacterial agent with toxic effect would not be safer to use in clinics. So, the toxicity profile of an antibacterial agent is an important indicator for future developments. To examine the biocompatibility of active compounds with blood cells, we first assessed the hemolytic activity of active hits on rabbit’s red blood cells at different concentrations. The hemolytic activity of the compounds was expressed as HC50 (the concentration of prioritized compounds used to lyse 50% of RBCs) value and are given in Table 3. As depicted in Supplementary Information Fig. S18A, compounds 3b, 3c, 3g, 3n and 3o showed no hemolytic potential (HC50 > 200 µM), at varying concentrations, indicating higher selectivity towards red blood cells. However, compounds 3l, 3e and 3d, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S18A and Table 3, have mild hemolysis (HC50 ranging from 45.2–140.6 µM) only at higher concentrations (50 µM). These findings indicated no or very low hemolytic activity of trisindoline derivatives; hence, these compounds could be proceeded for further comprehensive biological exploration.

Table 3.

CC50 values and selectivity indexes (SI = CC50/MICs) of potential hits against different mammalian cell lines (RAW 264.7 and HEK 293) and HC50 values of trisindoline derivatives towards red blood cells

| Entry | RAW 264.7 | HEK293 | RBCs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC50, µM | SIa | CC50, µM | SIb | HC50, µM | |

| 3b | 69.04 | 11.13 | 85.75 | 13.83 | >200 |

| 3c | 49.5 | 15.96 | 84.98 | 27.41 | >200 |

| 3d | 101.3 | 32.67 | >200 | ND | 140.6 |

| 3e | 47.42 | 31.61 | 56.32 | 37.54 | 61.4 |

| 3g | 81.88 | 13.20 | 95.24 | 15.36 | >200 |

| 3l | 97.98 | 31.60 | >200 | ND | 45.2 |

| 3n | 99.45 | 32.08 | 196.9 | 63.51 | >200 |

| 3o | 75.06 | 24.21 | 93.77 | 30.24 | 201.4 |

ND not determined.

aSelectivity index (SI) against RAW 264.7.

bSelectivity index (SI) against HEK 293.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay of the trisindolines to meet the therapeutic window

To investigate more about the clinical safety profiles of the compounds, trisindolines were further assessed for their cytotoxicity against different mammalian cell lines, including murine macrophage RAW 264.7 cell line and human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293. These different cell lines were treated with varying concentrations of compounds. Percent viability was assessed through MTT assay. The percent viability of RAW 264.7 & HEK 293 at different concentrations of the trisindolines is shown in the Supplementary Fig. S18B & C. The selectivity index (SI = CC50/MICs) for the compounds was further calculated, which were found ranging between 11–63 for all the active trisindolines, suggesting their higher safety index for experimented cell lines as depicted in Table 3. However, a few molecules showed toxicity only at higher concentration (100 μM). Therefore, the selected molecules (3b, 3c, 3d, 3e, 3g, 3l, 3n and 3o) were further proceeded for antistaphylococcal studies. Altogether, these findings from different biocompatibility studies demonstrated trisindoline derivatives as non-toxic molecules at optimized concentrations, signifying higher safety towards mammalian cell lines.

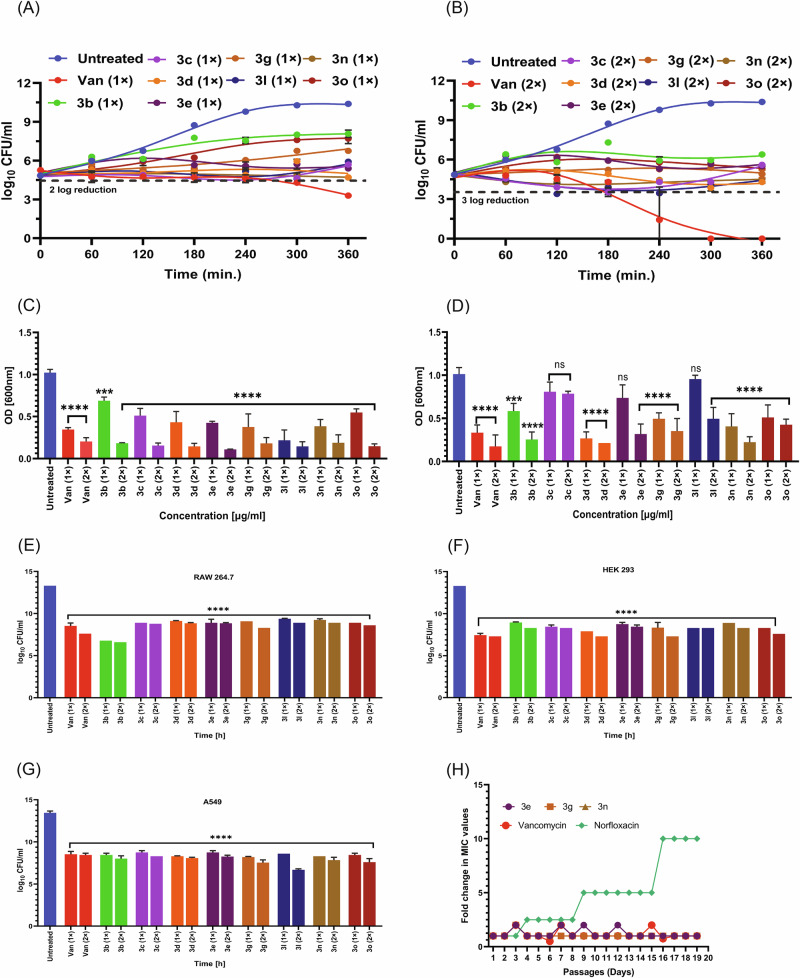

MRSA time-kill assay with the active trisindolines

After accessing the safety profiles of the active trisindolines, we investigated different in vitro antistaphylococcal behaviors of all 8 active compounds. Prominent bactericidal effect is an essential phenomenon for any good antibacterial agent. Time and concentration-dependent killing assay was performed to assess the bactericidal potential of trisindoline derivatives. MRSA inoculums were treated with the compounds (3b, 3c, 3d, 3e, 3g, 3n, 3l and 3o) at MIC and 2×MIC values up to 6 h and log CFU/ml was enumerated after each hour. The results are depicted in Fig. 3A & B, where the untreated control group represented uninterrupted growth. Figure 3A represents the killing potential of compounds (3b, 3c, 3d, 3e, 3g, 3n, 3l and 3o), where significant reduction of MRSA population by ~1.33–2.19 log folds at MIC value was observed after 6 h of treatment. Moreover, as represented in Fig. 3B, these compounds showed better killing efficacy (~1.61–2.39 log folds) at 2×MIC, within the same timeline. The standard drug vancomycin showed the ability to quickly kill bacteria as no colonies were observed after 6 h incubation at 2×MIC value. These observations suggested trisindoline derivatives might be an efficient guard in hurriedly killing MRSA through time and dose-dependent manner.

Fig. 3. In vitro and intracellular bactericidal efficacy of the trisindolines.

A & B Time and concentration-dependent killing of potential hits at their MIC and 2 × MIC, respectively, and vancomycin (positive control). C Biofilm inhibition efficacy of potent molecules at MIC and 2 × MIC, compared to vancomycin. D Disruption of preformed staphylococcal biofilm in the presence of active molecules at MIC and 2 × MIC. E–G Eradication of intracellular MRSA count in mammalian cell lines RAW 264.7, HEK 293 and A549. Enumeration of MRSA load was detected in infected RAW 264.7, HEK 293 and A549 cell lines after 24 h incubation with standard drug vancomycin and active compounds at their MIC and 2 ×MIC. H Fold change in MIC values of norfloxacin, vancomycin and compounds (3e, 3g & 3n) against MRSA. Statistical analysis was performed using ordinary one-way ANOVA (where *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001).

Biofilm inhibition and disruption potential of the trisindolines

Biofilm contributes as key component of bacterial persistence to several infections; hence imparts resistance to innumerable antibacterial agents. So, in recent scenario, a novel antibacterial drug should inhibit/kill sessile and free-living bacteria respectively. We performed biofilm inhibition assay to assess the efficacy of trisindoline derivatives against MRSA biofilm. As represented in Fig. 3C, compared to the untreated sample, the percent biofilm inhibition at MIC value was found between 20 to 60% for all treated compounds (3b, 3c, 3d, 3e, 3g, 3n and 3o), except for only one compound 3l. Notably, compound 3l, showed inhibition potential >70% even at MIC. However, the percent biofilm mass tremendously inhibited to >80% at two-fold MIC change for all compounds. Our findings demonstrated trisindoline derivatives efficacy in inhibiting MRSA biofilm formation in a dose-dependent manner. In order to examine the biofilm disruption potential of positive hits on preformed MRSA biofilm, further examination was conducted. Figure 3D clearly represents MRSA biofilm eradication potential of 3d about 56% and 65% at MIC and 2×MIC respectively. Additionally, biomass loss was observed nearly 30–60% in MRSA biofilm at two-fold MIC for 3b, 3e, 3g and 3n, suggesting their eradication potential via dose-dependent mode. Whereas, compounds (3c, 3l and 3o) elucidated low eradication potential of MRSA biofilm. Hence, these results demarcate MRSA biofilm disruption property by the derivatives.

Intracellular bactericidal efficacy of the trisindolines

MRSA is known to invade and eventually survive within mammalian cells, hence make treatment path difficult. MRSA intracellular killing efficacy was performed to elucidate the bactericidal potential of trisindolines, as it bridge the gap between in vitro and in vivo efficacy. We included three different cell lines as RAW 264.7, HEK 293 & A549 (Human lung adenocarcinoma cell line) for this investigation. As represented in Fig. 3E–G, compounds were able to significantly eliminate intracellular MRSA load by ~2 log fold reduction of MRSA population after 24 h infection at MIC and more profoundly at 2 × MIC. Moreover, the standard drug exhibited the same eradication potential as our synthesized compounds compared to untreated infection control. This significant reduction in MRSA count in three different mammalian cell lines signifies trisindolines as potent anti-intracellular moieties.

MRSA resistance frequency for the trisindolines through serial passage

As most of the positive trisindoline derivatives exhibited similar effect either in in vitro killing potential, antibiofilm efficacy, intracellular killing, we decided to further explore their resistant frequency with a few selected compounds as per their SAR. We selected one molecule from the classified groups as depicted in Fig. 2, and a total of three molecules (3e, 3g and 3n) were chosen in this assay.

Fig. 2. A brief Structure Activity Relationship (SAR) of synthesized trisindoline derivatives exhibiting anti-MRSA activity.

The SAR analysis depicted that halogenations (with Br, Cl and F) at 5 or 6 position of the trisindolines are critical for anti-MRSA efficacy whereas most of the derivatives with nitro, methyl or other substituent were found inactive. Simultaneously, bromine substitution alone or combined with chloro indole substitutions enhanced activity.

Although it is very common, bacteria develop resistance to antibacterial agents frequently. A new antibacterial agent demands low tendency towards resistance as its intrinsic characteristic. So, it necessitates to study the resistance pattern within bacteria, to categorize and design more robust molecules for better treatment outcome. Herein, we examined the pattern of resistance development in laboratory conditions, where MRSA cells were incubated over a period of 19 days at sub-lethal doses of compounds 3e, 3g and 3n through serial passage. The standard drugs vancomycin and norfloxacin were also included as controls. As depicted in Fig. 3H, it was demonstrated that no pattern of resistance was observed for trisindoline compounds and vancomycin, and MIC values remain almost constant. Whereas the MRSA cells treated with norfloxacin developed resistance upto 10-folds of the given MIC within the same duration. The failure to recover mutants in this stage suggests that compounds may attribute to its efficient killing and inhibiting resistant development and might have multiple mechanisms of action.

Synergistic effect of the trisindolines with vancomycin

Antimicrobial synergy is crucial factor for any antimicrobial agents, known for its substantial synergizing effect and decreased antibiotic dosage for effective infection treatment. In our research, we performed checkerboard assay to analyze the effective synergistic combination of trisindolines with standard antibiotic vancomycin. As depicted in Fig. 4, several synergistic combinations were found and represented as heat maps for the each trisindoline derivatives with vancomycin. To calculate the potential synergistic combination, FICI value was calculated by implementing standard formula, mentioned in the experimental section. Our study included three types of combinations, synergy, no interaction and antagonism. For the compounds 3b, 3c, 3d, 3e, 3g, 3l, 3n and 3o synergistic combinations 14, 15, 17, 9, 10, 7, 7 and 8 were observed with vancomycin, respectively. However, the most significant synergistic combinations were represented in the heat map and supplementary data Table S2. Moreover, additional results like no interaction and antagonism were also calculated (Data not shown). The checkerboard assay results revealed the potential of trisindoline derivatives to augment the effectiveness of vancomycin, indicating reduced antibiotic usage and lower resistance development.

Fig. 4. Checkerboard assay representing synergistic effect between potential hits and standard drug vancomycin.

A–H Heat maps of checkerboard assay between synthesized trisindoline derivatives and vancomycin. Synergistic combinations of compounds 3b, 3c, 3d, 3e, 3g, 3l, 3n and 3o with vancomycin, respectively. (Where % Inh represents percentage of inhibition, the orange color elucidates the inhibitory effect and the pale-yellow color displays visible growth of MRSA). A green dot in the heat map represented the best FIC value with FIC index <0.5, for each compound synergizes with standard antibiotic vancomycin.

In silico ADME, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry properties of the trisindolines

In order to predict the different physiochemical parameters like drug-likeness, lipophilicity and ADME properties compounds were submitted to SwissADME, admetSAR, molsoft and pkCSM, structure-based free software tools for computational analysis. These are extensively accessible tools for filtering out molecules for their drug-likeness and excluding non-drug like molecules. Mostly, in silico approaches are eventually implemented at the early stages to help medicinal druggists to select odd one-out molecules for further development. In silico examination of these compounds showed promising ADME properties within the expected range except for a few properties. As drug-likeness is a very important criteria for antibacterial agents. All synthesized compounds follow Lipinski’s rule of five with one or two violations. Although, there were well-known marketed available drugs which violated one or more rules of drug-likeness (for example vancomycin). Further, various other properties were analyzed including molecular weight, which is found in the optimized range of 100–600 D. All the ADME parameters were provided in Supplementary Table S3. Furthermore, these molecules displayed higher GI absorption rate. The solubility parameters were also lies in the speculated range for most of the molecules. Additionally, stereocenters and accessibility of rings for any molecule are important with respect to its drug-likeness as it enhances selectivity and binding potential with other moieties. However, the optimized range for ring criteria was fulfilled, but a few other attributes did not meet the expectations.

Antistaphylococcal killing mechanism of the trisindolines against MRSA

The indole-based derivatives were known to exhibit multiple antibacterial MOAs, as reported in many studies32–34. Apart from targeting essential bacterial proteins, membrane targeting indole derivatives were also reported earlier38. However, the antibacterial mechanistic insights of the trisindolines remain completely unexplored in earlier endeavors. To elucidate the effect of the synthesized trisindoline derivatives (compounds 3e, 3g and 3n) on MRSA, transcriptomic analysis was performed. Comparative analysis was conducted against untreated MRSA to identify significant transcriptional changes, revealing insights into the mode of action of these compounds.

Transcriptomic analysis of MRSA treated with trisindoline derivatives

RNA-seq analysis yielded high-quality reads with a mapping rate exceeding 99% across all samples, ensuring reliable downstream analysis. We identified numerous differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across the three compounds with respect to the untreated sample. Treatment with compound 3e resulted in 370 DEGs, comprising 121 up-regulated and 249 down-regulated genes. Similarly, compound 3g induced a more substantial transcriptional response, with 1209 DEGs (590 up-regulated & 619 down-regulated). Compound 3n exhibited 682 DEGs, with 314 up-regulated and 368 down-regulated genes.

The Gene Ontology (GO) analysis for compound 3e, 3g and 3n identified several significant biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components impacted by the compounds. A significant enrichment in the ATP-binding cassette transporter complex was observed in MRSA cell. These genes encode key components of ABC transporters (down-regulated), ABC transmembrane type-2 domain-containing protein (up-regulated), permease protein (up-regulated/down regulated), oligopeptide ABC transporter (up-regulated) and ATP-binding protein which is crucial for nutrient uptake, efflux and antimicrobial resistance. A broad enrichment was noted for membrane-associated genes, with 45 (3e), 170 (3g) and 73 (3n) genes contributing respective compounds to this category. The major membrane related pathways affected by the compound 3e, 3g and 3n were shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Heatmaps of the major DEGs observed in GO enrichment analysis.

A–C Heatmap of the DEGs between compound 3e treated and untreated MRSA in membrane associated pathways (A), ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter complex (B), and Phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar phosphotransferase system (C). D–F Heatmap of the DEGs between compound 3g treated and untreated MRSA in membrane associated pathways (D), Plasma membrane (E), and Phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar phosphotransferase (F). G–I Heatmap of the DEGs between compound 3n treated and untreated MRSA in membrane associated pathways (G), Trans membrane (H), and Phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar phosphotransferase system (I).

These gene encode proteins involved in cell wall integrity, nutrient transport and stress response. MRSA membrane stress-related and membrane-associated proteins like DUF1361 and DUF443 domain-containing proteins (up-regulated) were significantly enriched suggesting that the compounds may also disrupt structural integrity and environmental adaptability. However, majority of the membrane–associated genes belong to uncharacterized category. Some other membrane associated genes like drug resistance transporter (EmrB/QacA Subfamily) (up-regulated), thermonuclease (EC 3.1.31.1) (down-regulated), isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase family protein (down regulated), CPBP family intramembrane metalloprotease (SdpA) were also enriched (up-regulated). The phosphotransferase system (PTS) associated genes are also enriched with compounds 3e (8), 3g (19), and 3n (10) highlight the compounds’ ability to disrupt bacterial carbohydrate transport and metabolism. These systems are vital for importing and phosphorylating sugars (PTS system mannitol-specific EIICB component (EC 2.7.1.197) (up-regulated) and PTS system sucrose-specific IIBC component (EC 2.7.1.69)) (up-regulated), which are critical for bacterial energy production and cellular functions. Apart from the three crucial membrane associated pathways, other important membrane process like protein-N(PI)-phosphohistidine-sugar phosphotransferase activity, nickel cation transport, plasma membrane genes, transmembrane transport, acyltransferase activity, transferring groups other than amino-acyl groups, peptide transport, siderophore-dependent iron import into cell and transmembrane transporter activity were significantly enriched by the trisindolines. Table 4 shows the GO enrichment analysis of the trsiindoline treated MRSA cell.

Table 4.

Gene ontology (GO) and KEGG analysis of differential expressed genes (DEGs) in MRSA treated with compounds 3e, 3g and 3n

| Go enrichment analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Description | Count | |

| 3e | ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter complex | 7 | |

| Membrane | 45 | ||

| Phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar phosphotransferase system | 8 | ||

| Protein-N(PI)-phosphohistidine-sugar phosphotransferase activity | 5 | ||

| ATPase-coupled transmembrane transporter activity | 3 | ||

| 3g | Membrane | 170 | |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar phosphotransferase system | 19 | ||

| Protein-N(PI)-phosphohistidine-sugar phosphotransferase activity | 13 | ||

| Nickel cation transport | 17 | ||

| Plasma membrane | 139 | ||

| Transmembrane transport | 23 | ||

| Acyltransferase activity, transferring groups other than amino-acyl groups | 13 | ||

| Peptide transport | 7 | ||

| 3n | Siderophore-dependent iron import into cell | 7 | |

| Transmembrane transporter activity | 19 | ||

| Membrane | 73 | ||

| Phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar phosphotransferase system | 10 | ||

| Nucleic acid binding | 8 | ||

| ABC-type transporter activity | 5 | ||

| KEGG pathway analysis | |||

| Compound | Category | Sub-category | Count |

| 3e | Human Diseases | Infectious disease: bacterial | 17 |

| Metabolism | Global and overview maps | 29 | |

| Metabolism | Amino acid Metabolism | 6 | |

| Metabolism | Amino acid Metabolism | 8 | |

| Metabolism | Amino acid Metabolism | 9 | |

| Metabolism | Energy Metabolism | 5 | |

| Environmental Information Processing | Membrane Transport | 18 | |

| Environmental Information Processing | Membrane Transport | 17 | |

| 3g | Metabolism | Carbohydrate metabolism | 16 |

| Human Diseases | Infectious disease: bacterial | 28 | |

| Metabolism | Amino acid metabolism | 19 | |

| Human Diseases | Drug resistance: antimicrobial | 11 | |

| Metabolism | Amino acid metabolism | 15 | |

| Metabolism | Carbohydrate metabolism | 16 | |

| Metabolism | Global and overview maps | 75 | |

| Metabolism | Energy metabolism | 15 | |

| Metabolism | Glycan biosynthesis and metabolism | 16 | |

| Metabolism | Global and overview maps | 22 | |

| 3n | Human Diseases | Infectious disease: bacterial | 22 |

| Metabolism | Amino acid metabolism | 11 | |

DEGs between the trisindolines treated (3e, 3g and 3n) and untreated MRSA as noticed in GO and KEGG analyses are mentioned in the Supplementary Tables S4–S9 along with gene annotation.

The KEGG pathway analysis revealed that Compounds 3e, 3g and 3n significantly affect several common pathways, such as infection-related pathway (sao05150), amino acid metabolism, energy metabolism etc. as depicted in Table 4. For the infection-related pathway, all three compounds consistently target pivotal virulence factors, such as Clumping factor A (up-regulated) and Clumping factor B (up-regulated), which are fibrinogen-binding proteins essential for bacterial adhesion to host tissues and immune evasion. Additionally, Gamma-hemolysin components B and C (down-regulated) and Gamma-hemolysin H-gamma-ii subunit (down-regulated), which contribute to cytotoxicity by lysing host cells, are shared targets. The Immunoglobulin G-binding protein A (Staphylococcal protein A) (down-regulated) and Immunoglobulin-binding protein Sbi (down-regulated) are also common across the compounds, highlighting their role in immune evasion through binding and neutralizing host antibodies. The Staphylococcal complement inhibitor (SCIN) (down-regulated) and Chemotaxis inhibitory protein (CHIPS) (down-regulated) are consistently targeted, both of which play key roles in evading host complement-mediated killing and neutrophil chemotaxis. Additionally, these compounds disrupt amino acid biosynthesis, central carbon metabolism, nitrogen assimilation and nucleotide synthesis, effectively impairing bacterial growth and survival. All three compounds target key enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of essential amino acids. Compound 3e prominently affects pathways related to arginine, threonine and branched-chain amino acids by targeting enzymes like argininosuccinate synthase (EC 6.3.4.5) (up-regulated), homoserine dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.3) (down-regulated) and 2-isopropylmalate synthase (EC 2.3.3.13) (up-regulated). Similarly, compound 3g impacts arginine biosynthesis through enzymes like carbamoyl phosphate synthetase (down-regulated) and ornithine carbamoyltransferase (EC 2.1.3.3) (down-regulated). Compound 3n shares these targets while also disrupting arginine deiminase (EC 3.5.3.6) (down-regulated), further limiting arginine availability for bacterial metabolism and growth. The compounds collectively impair glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, essential pathways for ATP generation and biosynthetic precursor supply. Compound 3e disrupts glycolytic enzymes such as triosephosphate isomerase (EC 5.3.1.1) (up-regulated) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (EC 1.2.1.) (down-regulated). Additionally, it targets transaldolase (down-regulated) and ketol-acid reductoisomerase (EC 1.1.1.86) (down-regulated) affecting energy flow through the TCA cycle. Compounds 3g and 3n share these disruptions and uniquely inhibit fumarate hydratase (EC 4.2.1.2) (down-regulated), pyruvate dehydrogenase (EC 1.2.4.1) (down-regulated) and succinate dehydrogenase (EC 1.3.5.1) (down-regulated) further impairing aerobic respiration and redox homeostasis. Compounds 3g and 3n uniquely disrupt nitrogen metabolism by targeting urease subunits (EC 3.5.1.5) (up-regulated), carbamate kinase (EC 2.7.2.2) (down-regulated) and associated pathways. These enzymes are critical for nitrogen assimilation, which is essential for biosynthesis and cellular regulation. The inhibition of these pathways limits bacterial access to nitrogen, a key growth-limiting nutrient. Compound 3n specifically affects nucleotide biosynthesis through phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase (PurQ, EC 6.3.5.3) (up-regulated) impairing purine synthesis. This disruption compromises DNA and RNA production, further inhibiting bacterial replication and survival. Compound 3g uniquely targets teichoic acid synthesis pathways, including teichoic acid D-alanyltransferase (up-regulated) and related enzymes, which are critical for maintaining bacterial cell wall integrity and resistance to environmental stresses.

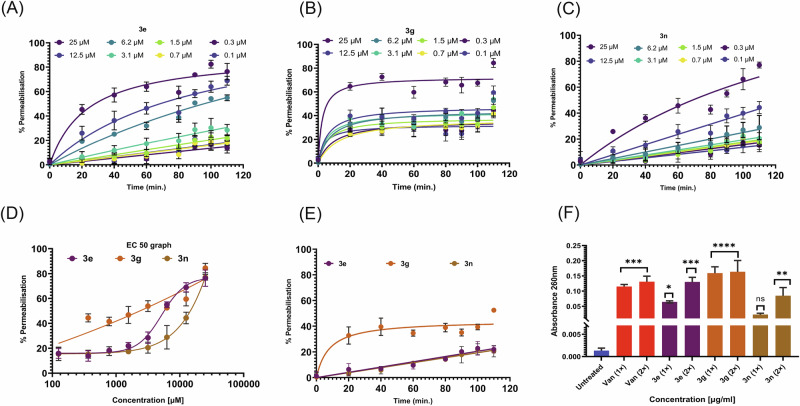

MRSA membrane disruption and permeabilization potential of the trisindolines

The transcriptomic data provided crucial hints about MRSA membrane target as probable mechanism of action of the selected trisindolines. In order to understand whether these compounds were able to disrupt the MRSA membrane, compounds 3e, 3g and 3n were subjected to MRSA culture with PI dye and incubated over time. The PI dye is unable to cross the membranes of live cells, but can enter cells that are impaired or have compromised membranes. Once inside the cell, PI binds to DNA and RNA, and becomes fluorescent. Elucidating the membrane disruption capability of the trisindolines to permit the entry of PI into MRSA cells was indicated by the increase in fluorescence, as represented in Fig. 6A–C. Undeniably, significant membrane disruption was observed for compounds 3e, 3g and 3n, at different concentrations, as we observed increased fluorescence over time and concentration-dependent manner. Moreover, the effective concentration 50 (EC50) was also calculated for these compounds subsequently after 2 h incubation period, found 1.5 µg/ml for 3e and 3n; and 2.4 µg/ml for compound 3g as shown in Fig. 6D. Additionally, PI dye permeabilization kinetics of 3e and 3n at MIC displayed slower permeabilization of 20–30%, as depicted in Fig. 6E. However, compound 3g showed significant permeabilization efficacy of 50–60% maximum after 2 h incubation, as shown in Fig. 6E, which supported our transcriptomics analysis.

Fig. 6. Membrane disruption potential of the trisindolines.

Membrane permeabilization activity of three selected hits at different concentrations against MRSA cells measured through propidium iodide (PI) assay over time A–C Membrane disruption and permeabilization effect of trisindoline derivatives (3e, 3g and 3n) at varying concentrations with respect to time. D EC50 (effective concentration) of compounds (3e, 3g and 3n) displayed permeabilization effect after 80 min. E Membrane permeabilization effect of compounds represented at their MIC. F Cell membrane integrity assay of MRSA suspensions treated with compounds at MIC and their 2 × MIC. In each cases, values are from three independent replicates.

Cell membrane integrity assay

Due to membrane disruption, cells’ cytoplasmic and genomic content including low molecular mass molecules, proteins, DNA, RNA, nucleotides and other intracellular components leak out from the lysed cells. Figure 6F displayed the amount of nucleic content released from lysed bacterial cells upon treatment with prioritized compounds (3e, 3g and 3n), as the absorbance at 260 nm increased significantly compared to the untreated cells. This assay further suggested that the compounds could damage bacterial membrane within 2 h of treatment at their 2 × MIC more efficiently than MIC. Our results clearly showed that the compounds (3e, 3g and 3n) were effective in disrupting the membrane integrity, which further helped to leak out the cellular components.

SEM analysis further confirms membrane disruption of MRSA by the trisindolines

Since, MRSA membrane disruption was noticed in the presence of the trisindolines, as depicted in our earlier assay, we further directed our study to visualize and confirm the membrane-disrupting ability of the trisindolines against MRSA. For that purpose, scanning electron microscopy was performed. We incubated MRSA in LB medium along with tested compounds at their MIC and 2×MIC. As depicted in Fig. 7B–I, MRSA with treated compounds 3e, 3g, 3n and vancomycin displayed alterations in their membrane integrity with clear disruption and bulging, followed by disruptive cell morphology and lysis of MRSA cells. On the contrary, untreated cells signified smooth and pristine edge without imperfections in MRSA cell wall (Fig. 7A). This electron microscopy study clearly indicates membrane disturbance and damage in the cell wall integrity of MRSA, proving the membrane-disruptive nature of the trisindolines.

Fig. 7. Visualization of the trisindolines induced membrane damage by SEM analysis.

A Untreated MRSA Control, B–I SEM images (Scale-1 μm) of MRSA cells treated with compound 3e, 3g and 3n along with standard drug vancomycin, displayed bulging and disruptions in the cell membrane. (Green boxes depicted enlarged view of the MRSA disruption for the compounds).

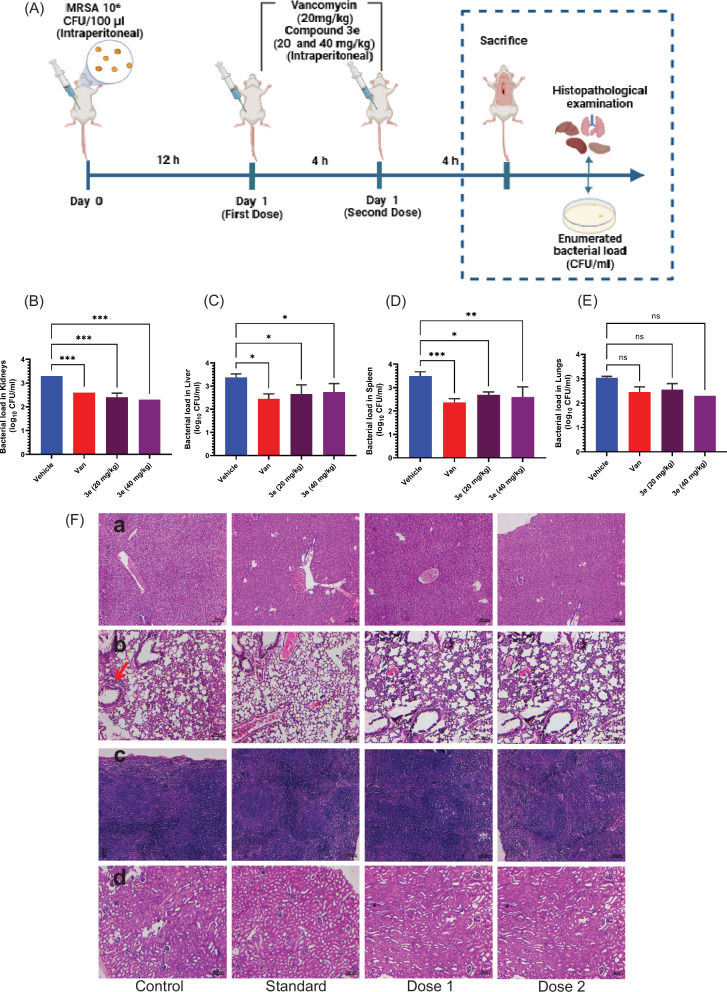

In vivo efficacy of compound 3e on MRSA infected mouse systemic model

Due to the most significant efficacy of compound 3e against MRSA, we further investigate the in vivo efficacy of this compound for its drug-like bactericidal potential against the MRSA-induced systemic infection model. The experimental design was represented in the schematic diagram Fig. 8A. Mice were first inoculated with 100 µl MRSA suspension (106 cells/100 µl) and observed for 12 h post-infection. Then, mice were treated with vancomycin (20 mg/Kg), as positive control) and two doses of compound 3e (20 and 40 mg/Kg), were administered intra-peritoneally over a period of 4 h incubation as depicted in schematic representation. MRSA counts after 3e treatment was included as key player in this study. After compound treatment, samples were mainly extracted from lungs, liver, spleen and kidneys and subjected for CFU enumeration. The effect of two doses (Group III and IV) were compared with standard control (positive group II, vancomycin) and disease control (Vehicle control group I), as represented in Fig. 8B–E. As displayed in Fig. 8B–D, significant reduction of MRSA load (1–2 log fold) were observed in the samples enumerated from kidneys, liver and spleen. However, <1 log fold reduction in MRSA colonies was observed in the case of lungs (Fig. 8E). Furthermore, significant reduction in colony number was observed for vancomycin at 20 mg/Kg, compared to disease control (vehicle). Planktonic MRSA-infected mice showed significant reduction for 40 mg/Kg dose compared to 20 mg/Kg dose. We further analyzed the histopathological studies at the end of the treatment set to analyze the toxic effect of compound 3e on different organs of mouse Fig. 8F.

Fig. 8. In vivo efficacy of trisindoline derivative 3e.

A Schematic representation depicting MRSA-induced Systemic infection model (B–E). Therapeutic efficacy of compound 3e in MRSA-induced mouse systemic infection model depicted eradication potential in vivo, computed as reduction in the MRSA CFU in major organs like kidneys, liver, spleen and lungs respectively. F H&E stained histopathology of (a) Liver (b) Lung (c) Spleen and (d) Kidneys (x100 magnification). Infection control group mice showed vacuolar degeneration of hepatocytes, congestion, emphysema, denudation of alveolar epithelium, and focal infiltration of mononuclear cells in the lungs (arrow). Lymphoid hyperplasia of the spleen and vacuolar degeneration of the kidneys are evident. The treated groups and standards had a mild degree of congestion in the lungs and cell swelling in the kidneys and spleen.

On histopathology examination, the infection control group mice showed loss of hepatic architecture with a moderate degree of vacuolar degeneration of hepatocytes with congestion, emphysema, denudation of alveolar epithelium and focal infiltration of mononuclear cells in the lungs. Cell swelling and vacuolar degeneration of tubular epithelial cells, shrinkage of glomeruli and a moderate degree of lymphoid hyperplasia are also evident in the infected mice. However, standard and treated groups mice manifested a mild degree of congestion in the lungs, minimal cell swelling of tubular epithelium and lymphoid hyperplasia in the kidneys and spleen. This in vivo study clearly signifies the potential of compound 3e to efficiently restrict the growth of MRSA-infected mice without imposing toxicity to major organs.

Discussion

MRSA is known as crucial etiological pathogen responsible for severe infections that enforce considerable impact on global health. Moreover, emergence of multidrug resistance in S. aureus mainly in clinical settings tremendously distorted the treatment options available in clinics for the treatment of S. aureus-related infections52. This distressing trend of MRSA infection demands novel strategies and therapeutics as antistaphylococcal agents. In this present research, we have strategically designed and synthesized a small library of 15 trisindoline derivatives. The library was screened against MRSA. Out of 15 compounds, 8 have emerged as positive hits possessing significant antistaphylococcal potential. Interestingly, hits were depicted as advantageous antistaphylococcal behavior, highlighting their strong inhibitory effect against MDR clinical isolates.

The SAR analysis of the trisindoline derivatives revealed distinct group-wise trends in their antibacterial activity against MRSA. As in Group 1, halogenation (Br, Cl and F) was identified as a critical factor for efficacy, with bromine-substituted 3e exhibiting the highest potency, which supported the findings from other resources39. In contrast, dithiomethyl substitution rendered the compound inactive, highlighting the specificity of halogenation in driving antibacterial activity. Additionally, in Group 2 most derivatives with nitro, methyl or fluorine substitutions showed no antibacterial activity, except for bromine-substitution. This finding further underscores the pivotal role of bromine in enhancing antibacterial efficacy. Moreover, in Group 3 combination of bromine substitution with chloroindole substitutions in active derivatives further enhanced their antibacterial potential, demonstrating the synergistic impact of these structural modifications on MRSA inhibition. These strategic modifications in indole and isatin highlight the importance of specific halogen substitutions, particularly bromine, chlorine and fluorine in conferring potent antibacterial activity to trisindoline derivatives. Noticeably, most of the hits were able to meet the selectivity criteria against RAW 264.7 & HEK 293 (SI > 10-fold of respective MIC value), hence revealed least lethality, and feeble hemolysis towards red blood cells, licensed the biocompatibility parameters as safer and efficient molecules, a noteworthy feature of any antibacterial agents.

Furthermore, several in vitro antistaphylococcal evaluations were carried out with the positive compounds. As expected, these compounds effectively demonstrated killing potency at MIC and, more profoundly at 2×MIC value. Biofilm strategy conferred by MRSA makes chronic infections more invulnerable and conventional antibiotics less operative according to previous literature53,54. However, our molecules not only portrayed inhibitory effect to MRSA biofilm establishment, but also strongly penetrate preformed biofilm matrix and disrupt MRSA biofilm matrix, signifying clear potency as antibiofilm agents. Often synergizing medications reduce dosage, enhance potency and diminishes the probability of resistant development, while treating an infection55. Addressing this phenomenon, potent hits were evaluated for their combinational effect by employing checkerboard assay with standard antibiotic vancomycin. The selected hits were able to synergies vancomycin. This synergism might be attributed due to the combinational effect of the compounds along with vancomycin on MRSA cell wall, as observed in our mechanistic investigations. MRSA was considered as facultative intracellular pathogen, conferring its ability to reside within macrophages, adapt immune-evasion strategy, hence make difficult to treat metastatic infection56,57. Moreover, intracellular pool of MRSA not only responsible for chronic and persistent infections but also responsible for guard against extracellular components, leading to drug resistance58,59. Uncovering this, we screened the positive antistaphylococcal trisindolines to specifically target intracellular MRSA without imposing harm to infected host cells. As expected, trisindoline molecules tremendously eradicate intracellular bacterial viability after 24 h infection. Inspiringly, all potent hits were able to significantly eliminate bacterial count (within 2 log folds reduction) in ex vivo settings, suggesting their strong anti-intracellular appearances. The low propensity to develop resistance is the most prominent characteristic of antibacterial agents60,61. To comprehend this, selected hits (3e, 3g and 3n) were examined for the resistance development potential. As anticipated, MRSA was unable to induce any resistance towards trisindoline derivatives, as compared to norfloxacin. This feature of trisindolines might be able to overcome the ability to generate resistance by MRSA.

The transcriptomic analysis of MRSA treated with trisindoline derivatives (3e, 3g and 3n) reveals significant transcriptional changes, with compound 3g inducing the highest number of DEGs, followed by 3n and 3e. GO analysis highlights that all three compounds target critical cellular processes, including membrane-associated proteins, ABC transporters essential for nutrient uptake, efflux and stress adaptation. The disruption of phosphotransferase system (PTS)-related genes and processes like peptide transport and siderophore-dependent iron import indicates a broad-spectrum effect on bacterial metabolism and survival. KEGG pathway analysis corroborates these findings, showing disruption of infection-related pathways, including virulence factors like clumping factors, gamma-hemolysins, SCIN and CHIPS. Key metabolic pathways, including amino acid biosynthesis, glycolysis, the TCA cycle and nitrogen metabolism were also affected. Collectively, the data suggest that trisindolines exert their antibacterial effects by impairing membrane integrity, transmembrane transport and core metabolic processes, highlighting their broad-spectrum potential against MRSA. To validate the membrane integrity disruption, we have performed two additional assays. PI dye-based membrane permeabilization and cell integrity assays were performed to test whether trisindoline derivatives disrupt and permeabilize the MRSA membrane. As reported earlier, one key failure observed in conventional antibacterial development that distorted their therapeutics capacities is meager permeability62,63. Interestingly, positive trisindoline derivatives displayed significant membrane disruption and permeabilization effect in a concentration-dependent manner. This membrane disruption nature of the molecules was further confirmed and visualized by our SEM investigations, where clear membrane damage was noticed in the treated cells. Due to their superior in vitro antibacterial potential, no cytotoxicity, no resistance development, remarkable permeabilization and suitable in silico ADME parameters, we further analyzed the compound 3e (MIC = 0.7 µg/ml) in in vivo settings. MRSA, pathogen of interest, well-renowned for their multiple infectious turmoil and bloodstream being one of them, most deadly and intractable. Therefore, we selected MRSA-induced systemic infection model to examine the in vivo antimicrobial potential of potent lead. Consequently, selected lead (3e) out of 8 potent hits, was administered to reduce the bacterial burden in MRSA-induced systemic infection model. Encouragingly, compound 3e significantly reduced the bacterial count in different organs including lungs, liver, spleen and kidneys. Moreover, potent lead offered no toxicity to major organs as displayed in histopathological study.

In summary, herein, we successfully synthesized 15 trisindoline derivatives and identified 8 effective molecules with potent anti-MRSA efficacy with significant inhibitory effect on multidrug resistant clinical isolates of S. aureus. Validation from cytotoxicity data compiled with significant antistapylococcal susceptibility on biofilm matrix signifies capabilities of synthesized molecules. The confirmed synergistic combinations with vancomycin further imply their potential for combinational therapy along with negligible propensity towards drug resistance. This work also provided powerful insights into the detailed MOA of trisindoline derivatives as MRSA membrane-disrupting agents. Most importantly, the given in vivo efficacy of the compound surfaced the way for future clinical development. Taken altogether, compound 3e emerged as a promising candidate for MRSA-related infections.

Methods

Chemistry

All the chemicals used in experiments were purchased from commercial sources mostly from Sigma Aldrich, TCI chemicals, Avra synthesis and were used without further purification. All compounds were characterized by spectroscopic data. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained using Bruker DPX- 400 and 101 MHz spectrometers with TMS as internal standard. Chemical shift (∂) is expressed in ppm, J values are given in Hz and deuterated DMSO was used as solvent. The High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) was also recorded using XEVO-G2-XS-Q-TOF mass spectrometer. All the reactions were monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC). Column chromatography was performed on silica gel (60–120 mesh). The yield of synthesized compounds was achieved to be >80%.

Synthesis of 3,3-di(indolyl)indolin-2-one (3a)

In an oven dried single neck round bottom flask charged with magnetic bead, isatin 1a (20 mg, 0.14 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), 2a (31.8 mg, 0.27 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) and Montmorillonite K10 in 2 mL of CH2Cl2 were added and the reaction mixture was sealed with rubber septum. The resulting mixture was stirred for 4-5 h at room temperature until the reaction was completed (monitored by TLC). After completion of reaction, the solution was transferred into the separatory funnel and washed with ethyl acetate. The residue left was purified by column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ethyl acetate and hexane to acquire a pure product 3a as colorless viscous liquid (93.12% yield, 46 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.97 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 2H), 10.62 (s, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.24 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 4H), 7.05–6.99 (m, 3H), 6.94 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H), 6.81 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 179.28, 141.75, 137.38, 135.07, 128.32, 126.16, 125.36, 124.74, 121.96, 121.44, 121.23, 118.72, 114.77, 112.08, 110.08, 53.05. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C24H17N3ONa [M + Na]+ 386.1269, found 386.1269.

Synthesis of 6,6”-difluoro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3b)

The compound 3b was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (97.62% yield, 53 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.07 (s, 2H), 10.67 (s, 1H), 7.28–7.13 (m, 6H), 7.01 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 2H), 6.76–6.67 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 179.01, 160.28, 157.94, 146.70, 141.68, 137.33, 137.21, 134.57, 128.50, 125.28, 122.93, 122.17, 122.10, 114.91, 110.23, 107.49, 107.25, 98.07, 97.82, 86.09, 67.52, 52.80. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C24H14N3OF2 [M-H]+ 398.1105, found 398.1099.

Synthesis of 5,5”-dichloro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3c)

The compound 3c was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (88.49% yield, 52 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.15 (s, 2H), 10.70 (s, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.28–7.17 (m, 4H), 7.02 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (dd, J = 15.1, 4.8 Hz, 3H), 6.85 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.8 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 178.90, 141.65, 137.81, 134.45, 128.58, 126.37, 125.72, 125.26, 124.90, 122.38, 122.19, 119.23, 114.99, 111.73, 110.31, 52.70, 27.31. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C24H14N3OCl2 [M-H]+ 430.0514, found 430.0508.

Synthesis of 6,6”-dichloro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3 d)

The compound 3d was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (88.49% yield, 52 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.27 (s, 2H), 10.78 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 3H), 7.11–7.06 (m, 3H), 7.05–6.96 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 178.96, 141.61, 135.90, 134.07, 128.75, 127.01, 126.56, 125.32, 123.45, 122.34, 121.62, 120.05, 114.34, 113.85, 110.35, 52.60. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C24H14N3OCl2 [M-H]+ 430.0514, found 430.0511.

Synthesis of 5,5”-dibromo-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3e)

The compound 3e was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (91.74% yield, 65 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.25 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 10.76 (s, 1H), 7.39–7.35 (m, 4H), 7.28 (td, J = 7.7, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.19–7.14 (m, 3H), 7.06–6.96 (m, 2H), 6.92 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 178.95, 141.63, 136.13, 134.03, 128.77, 127.71, 126.44, 125.33, 124.14, 123.10, 122.34, 114.33, 114.25, 111.55, 110.34, 52.61. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C24H14N3OBr2 [M-H]+ 517.9504, found 517.9497.

Synthesis of 6,6”-bis(methylthio)-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3 f)

The compound 3f was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (92.04% yield, 57 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.81 (s, 2H), 10.58 (s, 1H), 7.27–7.15 (m, 4H), 7.05–6.82 (m, 6H), 6.77 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 128.26, 125.38, 124.96, 123.06, 121.90, 120.80, 111.81, 109.96, 40.10, 21.91. LCMS, m/z calcd. for C26H20N3OS2 found to be 455.20.

Synthesis of 5’-bromo-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3g)

The compound 3g was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (91.98% yield, 36 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.04 (s, 2H), 10.80 (s, 1H), 7.47–7.36 (m, 3H), 7.31 (s, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.08–6.98 (m, 3H), 6.90 (s, 2H), 6.84 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 178.78, 141.11, 137.45, 137.39, 131.19, 127.80, 125.94, 124.88, 121.60, 120.94, 118.93, 113.96, 113.65, 112.25, 112.21, 53.26. LCMS, m/z calcd. for C24H15BrN3O found to be 442.25.

Synthesis of 5’-fluoro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3h)

The compound 3h was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (93.08% yield, 43 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.03 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 10.68 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.12–6.97 (m, 5H), 6.91 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H), 6.83 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 179.19, 159.51, 157.16, 137.97, 137.39, 136.82, 136.74, 125.99, 124.88, 121.55, 121.04, 118.87, 114.83, 114.60, 114.10, 112.98, 112.74, 112.18, 110.93, 110.84, 53.56. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C24H15N3OF [M-H]+ 380.1199, found 380.1200.

Synthesis of 5’-nitro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3i)

The compound 3i was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (96.44% yield, 41 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.38 (s, 1H), 11.11 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 2H), 8.25 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (dd, J = 8.3, 3.0 Hz, 3H), 7.06 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 6.85 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 179.43, 148.24, 142.68, 137.48, 135.74, 125.96, 125.83, 125.06, 121.73, 120.77, 120.54, 119.09, 113.27, 112.35, 110.43, 53.00. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C24H15N4O3 [M-H]+ 407.1144, found 407.1136.

Synthesis of 5’-methyl-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3j)

The compound 3j was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (93.93% yield, 44 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.95 (s, 2H), 10.50 (s, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.06–6.99 (m, 4H), 6.89 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 6.86–6.78 (m, 4H), 2.18 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 179.27, 139.31, 137.36, 135.09, 130.68, 128.60, 126.15, 125.90, 124.80, 121.41, 121.29, 118.69, 114.85, 112.06, 109.81, 53.08, 21.26. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C25H18N3O [M-H]+ 376.1450, found 376.1444.

Synthesis of 7’-chloro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3k)

The compound 3k was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (93.56% yield, 41 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.06 (s, 3H), 7.50–7.14 (m, 6H), 7.13–6.69 (m, 7H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 179.04, 170.84, 139.47, 137.39, 136.71, 128.32, 125.97, 124.84, 124.00, 123.33, 121.51, 121.03, 118.85, 114.29, 114.05, 112.18, 60.24. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C24H15N3OCl [M-H]+ 396.0904, found 396.0900.

Synthesis of 6,6”-dichloro-5’-fluoro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3l)

The compound 3l was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (91.67% yield, 50 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.23 (s, 2H), 10.77 (s, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.17–7.03 (m, 3H), 6.99 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 6.90 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.8 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 178.78, 159.57, 157.21, 137.78, 136.12, 126.42, 125.86, 124.72, 122.22, 119.34, 114.89, 114.31, 112.93, 111.78, 111.11, 53.18. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C24H13N3OFCl2 [M-H]+ 448.0420, found 448.0423.

Synthesis of 5,5”-dibromo-5’-methyl-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3m)

The compound 3m was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (90.33% yield, 60 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.23 (s, 2H), 10.65 (s, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H), 7.16 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.08 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.96–6.87 (m, 4H), 2.55–2.48 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 178.99, 139.18, 136.12, 134.01, 131.14, 129.06, 127.68, 126.55, 125.89, 124.11, 123.17, 114.34, 111.50, 110.08, 52.65, 21.25. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C25H16N3OBr2 [M-H]+ 531.9660, found 531.9655.

Synthesis of 5,5”-dichloro-5’-methyl-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3n)

The compound 3n was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (93.88% yield, 52 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.21 (s, 2H), 10.63 (s, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (s, 2H), 7.06 (dd, J = 14.5, 5.7 Hz, 3H), 6.93 (dd, J = 11.9, 6.8 Hz, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 179.00, 139.19, 135.90, 134.08, 131.13, 129.03, 127.00, 126.67, 125.87, 123.41, 121.59, 120.14, 114.45, 113.82, 110.08, 52.66. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C25H16N3OCl2 [M-H]+ 444.0670, found 444.0667.

Synthesis of 5,5”,7’-trichloro-[3,3’:3’,3”-terindolin]-2’-one (3o)

The compound 3o was synthesized according to the general procedure 3a and purified using column chromatography over silica gel (60–120 mesh) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (60:40) as eluent to obtained colorless viscous (91.42% yield, 47 mg). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.29 (s, 2H), 11.17 (s, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 3H), 7.04 (dd, J = 16.5, 8.9 Hz, 3H), 6.95 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 178.74, 139.33, 135.92, 135.74, 128.72, 126.85, 126.63, 123.98, 123.75, 123.57, 121.74, 119.87, 114.56, 113.96, 113.68, 53.46. HRMS (ESI), m/z calcd. for C24H13N3OCl3 [M-H]+ 464.0124, found 464.0119.

Bacteria and culture conditions

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 15187) was experimented in this research for anti-staphylococcal characterization64. MRSA was cultivated in Luria Bertani broth, Miller consists of Casein enzymic hydrolysate 1%, yeast extract 0.5% and sodium chloride 1% or Luria Agar Base, Miller’s Modification composed of Tryptone 1%, yeast extract 1%, sodium chloride 0.05% and agar 1.5% or Tryptone Soya Broth includes Tryptone 1.7%, soya peptone 0.3%, sodium chloride 10%, dextrose 0.25%, di potassium hydrogen phosphate 0.25% and sodium pyruvate 1%) were used. The bacterial cultures were appropriately grown and sustained at 37 °C under constant shaking at 160 rpm (REMI Orbital Shaking Incubator CIS-24 PLUS). The present research also includes multidrug resistant clinical isolates of S. aureus (SA-01 to SA-21).

Antimicrobial susceptibility assays (MIC and MBC)

The MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) values of the synthesized trisindoline compounds were determined using a modified resazurin dye-based microtiter dilution method, as previously described64–66. The bacteria were incubated at 37 °C overnight and then transferred to fresh nutrient broth (LB) during the logarithmic growth phase. Further, the bacteria were diluted to a concentration of OD600 = 0.05 in LB. The synthesized compounds were dissolved in DMSO and then added to 96-well plates serially with 100 μl of bacteria in LB. The samples were then incubated at 37 °C for 15–16 h in an incubator. After that, resazurin dye (0.04%) was added to the plates and incubated for 1 h. The percentage of staphylococcal growth in the presence of compounds was calculated based on the fluorescence value (570 nm) of the resazurin due to bacterial respiration. The MIC was determined by the cell viability percentage at different concentrations of the tested compounds67. Finally, the results were expressed as an average of the MICs obtained from three independent experiments.

We determined the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of the compounds against MRSA, by taking 10 μl of the cultures from each well of the microtiter plate were spread on LB agar plates. The concentration of the compounds at which no colonies were formed was recorded as the MBC value for the corresponding concentration.

Hemolytic activity assay

Hemolytic effect of trisindoline derivatives was examined with slight modification according to previously existed protocol68,69. Fresh rabbit blood was collected from healthy rabbit, prevented for coagulation with anticoagulant EDTA. In brief, cells were centrifuged at first for 5000 rpm for 10 min, followed by five times per minute washing with 1×PBS until the supernatant showed clear phase. A 1:10 dilution was prepared as RBCs suspension in 1×PBS and incubated with compound at various concentrations (50 µM, 40 µM, 30 µM, 20 µM, 10 µM and 5 µM) in 96-well pates for about 4 h at 37 °C. Afterwards, the suspension was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min. and clear supernatant of 100 µl for each concentration was transferred to fresh 96-well microtiter plate. Furthermore, hemoglobin level was observed at absorbance 577 nm. The physiological pH was considered as negative control and 1% Triton X-100 was treated as positive control. The experimental set up was replicated three times and the percent hemolytic activity was calculated according to reported equation:

Hemolytic Ratio (%) = Sample (OD577)-Negative control (OD577)/Positive control (OD577)-Negative control (OD577) × 100

In vitro cytotoxicity assay