Abstract

Background

Esophageal cancer (EC) has a high incidence and is highly invasive. It is meaningful to employ invasion-related genes (IRGs) to predict patients’ prognosis.

Methods

We launched a weighted correlation network analysis to screen for EC tumor differentially expressed IRGs (module genes) from the TCGA-ESCA dataset. By executing univariate-LASSO-multivariate Cox regression analyses, we stepwise selected module genes to obtain prognostic feature genes and create a model. We validated the model using the external GEO dataset GSE53624. We assessed the model’s independent prognosis prediction ability. A nomogram was plotted and further validated later. GSEA was undertaken on high-risk groups (Group H). We compared immunity and tumor mutations in Group H and the low-risk group (Group L) and made small molecular drug predictions on prognostic genes.

Results

A risk prognostic model consisting of 10 genes (ARMCX2, RGS16, APLN, TRIM28, AKAP4, ZC3H12B, MAD1L1, TWIST1, TMTC2, and TADA2B) was created. ZC3H12B was significantly linked with TADA 2B, AKAP4, and TWIST1 (P < 0.01). The model exhibited a good predictive performance, functioning as an independent prognostic factor. The predictive accuracy of the nomogram was relatively high. Pathways that were significantly enriched in Group H included base excision repair, cysteine and methionine metabolism, and porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism (P < 0.05). Compared with Group L, Group H had higher expression of relevant immune genes and a higher degree of tumor mutation (P < 0.05). ZC3H12B was significantly linked with immune cells (macrophages and iDCs), showing a high degree of mutation. The IC50 values of Lomustine, Dexrazoxane, Batracylin, and Buthioninesulphoximine were significantly positively linked with the expression of ZC3H12B (P < 0.01).

Conclusion

The 10-gene prognostic model can independently predict patients’ prognosis. The great correlation between ZC3H12B and multiple feature genes and immune cells may be tightly linked to EC progression.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-025-03095-w.

Keywords: Tumor invasion, Esophageal cancer, Weighted correlation network analysis, Immunity, Gene set enrichment analysis

Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is a malignant tumor originating from the esophageal epithelium, including esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), ranking the 11th among most commonly diagnosed cancers globally and the 7th among leading culprit of cancer death [1]. The key contributors of EC mainly include smoking [2], alcohol consumption [3], and overweight [4]. The conventional treatment strategies for EC include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and molecule-targeted therapy [5, 6]. Despite tremendous advances in these treatment methods, the survival rate for EC patients remains very low [1]. Accurate prognosis is crucial for early intervention in the disease to elevate patient survival rates. However, the existing prognosis biomarkers still cannot offer an accurate prognosis prediction for EC patients. Innovating effective prognostic biomarkers is a common goal of researchers.

EC usually exhibits strong invasiveness, which is an essential step in the progression of EC [7]. EC tumors grow rapidly and can invade the esophageal mucosa and spread to surrounding tissues in a short period, such as the esophageal wall, lymphatic vessels, nerves, etc [8–10]. Among them, lymph node metastasis is the major pathway for the spread of most solid tumors [11]. The formation of distant metastatic lesions leads to impaired esophageal function in patients, worsening their condition and suffering. Due to the strong invasive nature of EC, there are often no obvious symptoms in the early stages, leading to the tumor being detected only at an advanced stage, resulting in an adverse prognosis [12]. Although the mechanisms leading to EC invasion are increasingly elaborated through in vitro and animal models, laboratory results have so far not been translated into clinically relevant treatments [13, 14]. Therefore, applying invasion-related genes (IRGs) in prognosis prediction for guiding personalized clinical treatment of EC patients is essential.

This research resorted to weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) to screen for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with EC tumor invasion and built a prognostic model with these genes. Later, a series of analyses and verifications were carried out on the model to probe into the relationship between the model and immunity and tumor mutations. Ultimately, potential therapeutic targets and drugs for treating EC were mined based on the model feature genes. This research can provide some reference for the prediction of the survival rate of EC patients and doctors’ evaluation of clinical treatment options.

Materials and methods

Data download

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) provided mRNA expression data (normal: 13, tumor: 185), mutations, and clinical data for EC (TCGA-ESCA). The TCGA dataset was utilized as the training set. Chip data (GSE53624: cancer and adjacent normal tissue from 119 EC patients) was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) as a verification set. 97 IRGs were obtained from the former research [15] (Table S1).

Differential expression analysis of genes in the EC sample

The “edgeR” package [16] was applied to conduct differential expression analysis of genes between normal and tumor groups in ESCA, with normalized treatments followed. Subsequently, further differential screening of these genes was carried out (|logFC|>0.5, FDR < 0.05) [17] to obtain DEGs.

DEGs associated invasion screened by WGCNA

Scores of EC IRGs were calculated using the “GSVA” package [18]. A gene co-expression network was created to screen gene modules related to tumor invasion scores. To set up a co-expression network, we clustered all cancer samples according to the expression amount of the samples and excluded abnormal samples using 5e + 6 as the height threshold. The construction of a weighted adjacency matrix and the selection of a feasible soft threshold were necessary for ensuring a scale-free network. The adjacency relationships were then transformed into a topological overlap matrix. Hierarchical clustering was performed on the genes to identify modules containing related genes. The minimum size of the gene dendrogram was set to 30, and the cut line for the module dendrogram was set at 0.25 to merge some similar modules. Finally, the tumor invasion-related DEGs in modules with a correlation greater than 0.25 were selected as the basis for subsequent studies. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were undertaken on these DEGs.

Correlation analysis

To examine the relationships among the feature genes, the final feature genes were subjected to Pearson correlation analysis, with the rcorr function in “Hmisc” [19] applied to detect correlation coefficients and significant p-values. A heatmap was drawn.

Screening prognosis-related features to construct and validate a prognostic model

Clinical data were combined with the expression levels of DEGs in the module based on the samples, and tumor samples with survival times greater than 30 days were retained. Univariate Cox regression analysis on these genes was completed by utilizing the “survival” package [20]. Candidate genes were screened based on p-value (p-value < 0.05). To prevent model overfitting, the “glmnet” package was employed [21] in the LASSO Cox regression analysis on candidate genes, with cross-validation conducted to select the penalty parameter lambda to remove highly correlated genes and reduce model complexity. The “survival” package was applied in multivariate regression analysis on those candidate genes to set up the prognostic model. The model formula is riskscore=∑xi*βi (xi: gene expression; βi: the corresponding gene coefficient obtained from multivariate Cox regression).

After obtaining the risk score for all EC patients based on the model formula, the median model score was calculated. Samples were clustered into a high-risk group (Group H) and a low-risk group (Group L) based on the median risk score. Subsequently, using the risk scores of the samples, the survival curves for patients in the Group H and Group L were plotted using the “survival” package. By utilizing the “timeROC” package [22], we calculated the AUC values of the 1 year, 3 year, and 5 year receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of EC patients and drew ROC curves. The distribution map of patient risk scores, patient survival status, and a heat map of the expression levels of prognostic genes in EC patients in Group H and Group L were drawn. Finally, the performance of the model was verified using the external GEO dataset GSE53624. The model was also applied to calculate the risk score and the median risk score for each patient in the GEO dataset. The patients were also divided into Group H and Group L. Survival curves and ROC curves of patients in this dataset were drawn to judge the validity of the model.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

With the normalized expression matrix obtained from “edgeR” and the risk group labels, we created the input file. We then employed the GSEA software to conduct the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis on Group H.

Independent prognostic analysis

Combined with risk scores and clinical information (including EC TMN stage and tumor stage), model scores for patients at each clinical stage were compared, and Wilcoxon’s test was utilized to compare their significance. At the same time, the patient’s clinical characteristics (gender, age, T, M, N, Stage) and the prognostic model risk score were combined to perform univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis on the samples. Corresponding forest maps were drawn to determine whether the model can be applied as an independent prognostic factor. With the use of the “rms” package [23], a nomogram on the risk score of the prognostic model and the patient’s clinical characteristics (gender, age, T, M, N, Stage) was graphed to predict the patient’s 1, 3 and 5 year survival rates, with corresponding correction curves generated to verify the predictive effect of the nomogram.

Immune analysis

The single sample GSEA (ssGSEA) was completed by utilizing “GSVA” [18] and “estimate” [24] packages, with the immune cells and immune function scores of Group L and Group H calculated and a box plot drawn. The expression levels of immune checkpoints in Group H and Group L were analyzed. Box plots were graphed. The expression levels of HLA genes in the two groups were collected and recorded.

Analyses of tumor mutation burden (TMB) and copy number variation

Based on EC’s mutation data, the mutation status of genes in all samples was plotted by utilizing the “maftools” package [25]. A waterfall chart was plotted to display the top 30 genes with higher mutation levels. The mutation status of candidate genes in the model across all samples was displayed. The TMB score of each sample was then calculated. The TMB values of Group H and Group L were subjected to the Wilcoxon test, and the violin chart was drawn.

Drug sensitivity prediction

To determine potential disease treatment targets and applicable drugs, the CellMiner database (https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer/) was chosen to screen for antitumor drugs that were greatly related to prognostic characteristics and had visible differences in IC50 between Groups H and L.

Results

Acquisition of differentially expressed tumor IRGs in EC

Differential expression analysis yielded 5745 EC tumor-related differential genes, including 2987 up-regulated genes and 2785 down-regulated genes in EC tumors (Fig. 1A). Tumor IRGs play a crucial role in tumor development. We intended to probe into the differentially expressed IRGs in EC. First, the GSVA package was applied to calculate the scores of IRGs in different EC samples, which were used as trait inputs in WGCNA. Before building the network and screening relevant modules, cancer samples were clustered and no abnormal samples were found. The similarity matrix of gene expression was transformed into an adjacency matrix. Based on the approximate scale-free topology, the soft threshold was 5 and the R2 was 0.95 (Fig. 1B). Connectivity information was also preserved as much as possible at this time (Fig. 1C). Next, hierarchical clustering was constructed, and dynamic tree cutting was applied to identify modules co-expressing with tumor IRGs, resulting in a total of 24 gene modules (a distance greater than 0.25) (Fig. 1D). Herein, a positive correlation module (purple, cyan) with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.5 and a negative correlation module (tan) with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.4 were selected. The three modules contained 152 (purple), 121 (cyan), and 136 (tan) DEGs, respectively (Fig. 1E). Among the 409 module genes, there were a total of 178 upregulated tumor genes (Table S2) and 231 downregulated tumor genes (Table S3) (Fig. 1F). GO enrichment analysis revealed that these 409 module genes were considerably aggregated in functions such as extracellular matrix structural components, endopeptidase activity, sulfur compound binding, integrin binding, and collagen binding (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1G). KEGG enrichment analysis demonstrated great aggregation in pathways such as muscle cytoskeleton, protein digestion and absorption, and ECM receptor interaction (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1H).

Fig. 1.

Screening of differentially expressed invasion-related module genes in EC. A Volcano plot of DEGs in tumors. Green represents all down-regulated DEGs, while red represents all up-regulated DEGs. B Scale-free topology fitting index for different soft thresholds (x-axis). C Analysis of average connectivity (y-axis) for different soft thresholds (x-axis). D Gene clustering tree. E Correlation between different modules and cancer invasion scores. F Heat map of the expression of 409 DEGs selected by WGCNA in normal and tumor samples. Light red indicates upregulated DEGs; light green indicates downregulated DEGs; red indicates upregulated module genes; green indicates downregulated module genes. G GO enrichment analysis results of 409 differentially expressed module genes selected by WGCNA. H KEGG enrichment analysis results of 409 differentially expressed module genes selected by WGCNA

Building of a prognostic model related to tumor invasion

409 module genes were included to create a prognostic model. After combining the expression data of invasion-related module genes with clinical data, univariate Cox regression analysis was performed, filtering out 28 candidate genes linked with survival using a p-value < 0.05 as the threshold (Table S4). Subsequently, a LASSO Cox analysis was undertaken on these 28 genes, resulting in 17 feature genes (Table S5) (Fig. 2A-B). The multivariate Cox regression analysis was processed on the 17 feature genes, with 10 prognostic feature genes (Table S6) ultimately screened out to form a prognostic model (Fig. 2C). Pearson correlation analysis of these 10 prognostic genes demonstrated that the gene pairs with strong correlation included: ZC3H12B-TADA2B (Correlation coefficient: 0.44, P < 0.001), RGS16-TWIST1 (Correlation coefficient: 0.44, P < 0.001), ZC3H12B-AKAP4 (Correlation coefficient: 0.26, P < 0.001) MAD1L1-TWIST1 (Correlation coefficient: 0.23, P < 0.01), ARMCX2-RGS16 (Correlation coefficient: 0.19, P < 0.01) and ZC3H12B-TWIST1 (Correlation coefficient: -0.19, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2D). Among them, ZC3H12B had a great linkage with most feature genes.

Fig. 2.

Construction of invasion-related prognostic model. A LASSO coefficient spectrum of LASSO Cox analysis. B Coefficient distribution plot generated for the log(λ) sequence in the LASSO model. C Forest plot of multivariate Cox regression D Heatmap of correlation coefficients and p-values. *: 0.01 ≤ p < 0.05; **: 0.001 ≤ p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001

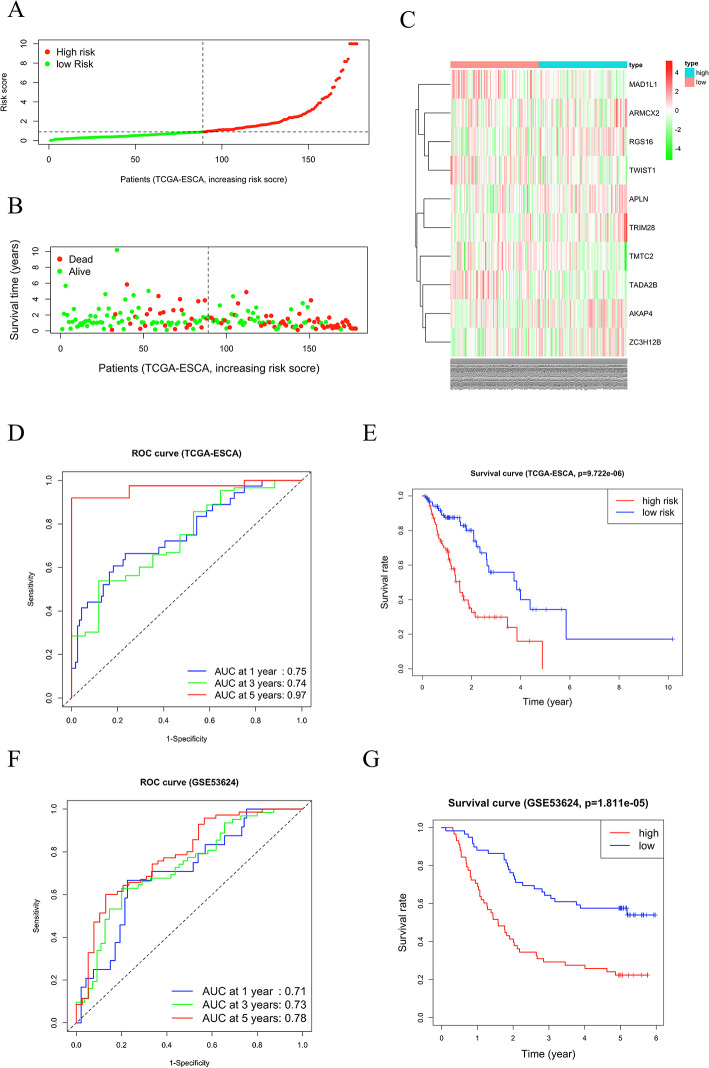

Validation of the prognostic model

Next, we employed the training and verification sets to verify the model’s performance. Using the previously obtained prognostic feature model, we calculated the risk scores of the TCGA clinical samples. We clustered the patients in TCGA into Group H and Group L based on the median score (Fig. 3A). Compared to Group L patients, those in Group H had a shorter survival time and a higher number of deaths (Fig. 3B). Compared with patients in Group L, in Group H, the upregulated prognostic genes included ARMCX2, RGS16, APLN, TRIM28, AKAP4, and ZC3H12B, and downregulated prognostic genes included MAD1L1, TWIST1, TMTC2 and TADA2B (Fig. 3C). The AUC values of the ROC curves for patients at 1, 3, and 5 years were 0.75, 0.74, and 0.97 (Fig. 3D). The survival curve manifested that there were great differences in survival rates between Group H and Group L. The survival rate of patients in Group H was significantly lower than that of patients in Group L (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3E). We further utilized the GSE53624 validation set to demonstrate the broad applicability of the model. The risk score for each patient in the GSE53624 validation set was calculated based on the expression levels of the model feature genes and the model coefficients. Patients in the GSE53624 validation set were similarly categorized into Group H and Group L according to the median risk score. The ROC curves for the validation set patients at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years had AUC values of 0.71, 0.73, and 0.78, respectively (Fig. 3F). The survival curve results demonstrated that the survival rate in Group H was significantly lower than that in Group L (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3G).

Fig. 3.

Validation of the model using the TCGA-ESCA training set. A Risk score distribution map. B Survival status distribution map. C Heatmap of expression levels of prognostic feature genes. D ROC curves E Survival analysis of Group H and Group L. F ROC curves of the GEO validation set (GSE53624). G Survival analysis of Group H and Group L in the GEO validation set (GSE53624)

Drawing and analyzing EC tumor prognosis nomogram

According to the analysis above, the EC invasion-related prognostic model was relatively accurate in predicting survival outcomes. Moreover, the risk scores of the tumor population in advanced EC cancer were considerably higher than those of the early-stage cancer population (Fig. 4A). The univariate regression analysis showed that M, N, stage, and risk score had significant meaning (p-value < 0.001) (Fig. 4B). Multivariate regression analysis manifested that only riskScore was significant (p-value < 0.001) (Fig. 4C). The model score constructed in this research was a factor that can predict EC prognosis independently (p < 0.001). Risk models were further combined with clinical characteristics to create nomograms to predict patient survival (Fig. 4D). The 1- and 3 year correction curves displayed that the predicted survival rate of the model had a high fit with the actual survival rate (Fig. 4E–F). Since there were only 4 samples with survival times greater than 5 years, an accurate calibration curve for 5 years was not plotted. Therefore, when the tumor IRG model and clinical features jointly predicted patients’ survival, they also had a good predictive ability.

Fig. 4.

Construction and verification of the prognosis nomogram. A The violin plot of Riskscore and clinical information. B Forest plot of univariate regression analysis. C Forest plot of multivariate regression analysis. D The nomogram incorporates scores of the prognostic model and clinical information. E 3 year risk prediction calibration curve. F 3 year risk prediction calibration curve

GSEA results

Due to the poorer survival rate of patients in Group H, we aimed to explore the biological pathways that may affect these patients. GSEA software was utilized to perform KEGG pathway enrichment analysis on the genes of patients in Group H. The genes of patients in Group H were remarkably enriched in base-excision repair, cysteine and methionine metabolism, and porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism pathways (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

GSEA pathway enrichment analysis in Group H

Immune microenvironment analysis of groups H and L

It is well known that tumor progression is inextricably linked to tumor immune microenvironment. Therefore, we further compared the immune microenvironment of patients in Group H and Group L. By using ssGSEA, different immune cell and immune function scores were calculated based on the level of gene expression in each sample. Scores related to three types of immune cells (iDCs, macrophages, mast cells) and one type of immune function (Type-II-IFN-Response) were considerably different between Group H and Group L. The score in Group H was significantly lower (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A). Correlation analysis was conducted between the scores of these four types of immune cells and immune functions and ten feature genes. ZC3H12B was significantly inversely linked with immune cells macrophages and iDCs (P < 0.001). TWIST1 was significantly positively linked with immune cells macrophages and iDCs (P < 0.001). Macrophages were also significantly inversely linked with TADA2B and AKAP4 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6B). Through immune checkpoint analysis, compared to Group H EC patients, the gene expression levels of three immune checkpoints (CCL19, BTNL2, and CD44) were significantly higher in Group L (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6C). The HLA boxplot displayed that the expression levels of the six HLAs (HLA-DQB1, HLA-DOA, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DRB1, HLA-DRA, HLA-DOB) were significantly higher in Group L (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Immune analysis of Group H and Group L. A Box plot of immune cell and immune function scores calculated by ssGSEA in Group H and Group L. B Heatmap of the correlation between four immune cells with significant differences in Group H and Group L and 10 feature genes related to immune function. C Boxplot of immune checkpoint expression levels. D Boxplot of HLA expression. *0.01 ≤ p < 0.05; **0.001 ≤ p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Analysis of tumor mutations in groups H and L

We analyzed gene mutations in 18 TCGA-ESCA samples containing 10 feature genes. Four of the 10 genes (ZC3H12B, TADA2B, TWIST1, and AKAP4) were found to have mutations in 50% of the samples (Fig. 7A). The gene with the highest mutation rate was ZC3H12B (mutation rate: 22%). Next, the degree of gene mutations in Group H and Group L patients was analyzed. The TMB in Group H was significantly higher than that in Group L (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7B). However, the top 5 mutated genes with the highest mutation degree within the two groups were the same, namely TP53, TTN, MUC16, CSMD3, and SYNE1 (Fig. 7C–D). Since the gene mutations in Group H and Group L were similar, we launched a further analysis of mutations in all TCGA-ESCA samples. The majority were missense mutations, with SNPs being the most common mutation type, particularly C to T mutations (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7.

Tumor mutation analysis of Group H and Group L. A Mutations of 10 feature genes in the samples. B TMB violin diagram of Group H and Group L. C Waterfall chart of the top 30 gene mutations in Group H. D Waterfall chart of the top 30 gene mutations in Group L. E Summary of mutations in tumor samples

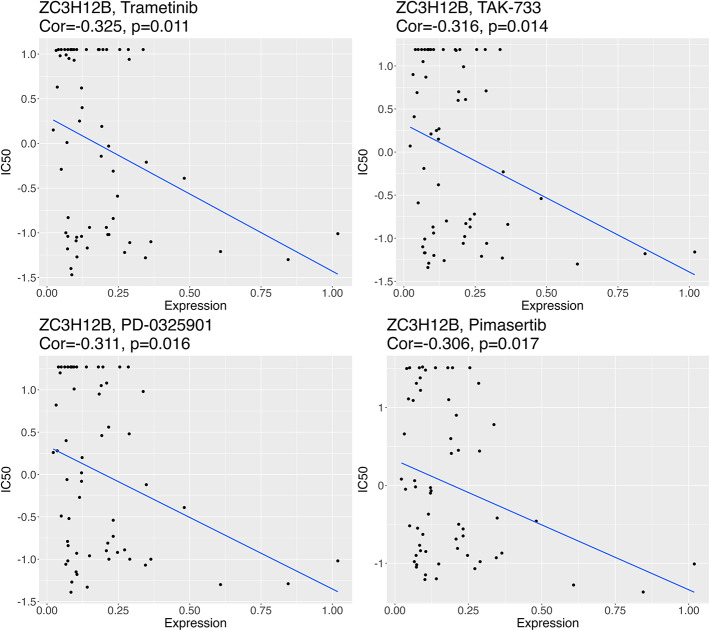

Exploration of the correlation between ZC3H12B and four drugs

As mentioned before, ZC3H12B had the highest negative correlation coefficient with immune cells in Group H and Group L, significantly linked with the most feature genes. Therefore, we used the CellMiner database to further predict the relationship between the characteristic gene ZC3H12B and the drug sensitivity of common clinical small molecular drugs. The IC50 values of the drugs Trametinib, PD-0325901, Pimasertib, and TAK-733 were significantly inversely linked with the expression level of the feature gene ZC3H12B (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Correlation analysis of ZC3H12B with the sensitivity to four drugs

Discussion

409 EC differential module genes were screened through WGCNA. After filtering these genes through univariate-LASSO-multivariate Cox regression analyses, a risk prognostic model for 10 genes (ARMCX2, RGS16, APLN, TRIM28, AKAP4, ZC3H12B, MAD1L1, TWIST1, TMTC2 and TADA2B) was obtained. This tumor invasion-related model was able to accurately predict the survival outcomes of EC patients, serving as an independent prognostic factor. Great correlations were detected among multiple prognosis features, especially for ZC3H12B. The significantly correlated genes included: ZC3H12B-TADA2B (correlation coefficient: 0.44, P < 0.001), ZC3H12B-AKAP4 (correlation coefficient: 0.26, P < 0.001), ZC3H12B-TWIST1 (correlation coefficient: − 0.19, P < 0.01). Furthermore, in subsequent analysis, the gene ZC3H12B was significantly inversely linked with immune cells: macrophages and iDCs (P < 0.001). Moreover, ZC3H12B had the highest mutation degree among all feature genes. ZC3H12B is a new active member of the ZC3H12 protein family, known to be implicated in the inflammatory process [26]. This gene has a bearing on the progression of other tumors. miR-320a can also repress the tumorigenesis, invasion, and angiogenesis of ovarian cancer by targeting ZC3H12B [27]. By using ZC3H12B as a potential therapeutic target, we further predicted the relationship of it with small molecular drugs. The results revealed that the IC50 values of the drugs Trametinib, PD-0325901, Pimasertib, and TAK-733 were significantly inversely linked with the expression level of the characteristic gene ZC3H12B (P < 0.05), indicating that when this gene was upregulated in patients, these drugs may serve as potential anti-EC tumor medications. Although there is little research centering on the mechanism of ZC3H12B in EC, we will focus on this gene in future research to deeply excavate its mechanism in EC progress and its interaction with drugs.

Compared to Group L patients, in Group H, the prognostic feature genes that were highly expressed included ARMCX2, RGS16, APLN, TRIM28, AKAP4, and ZC3H12B, while the low-expressed genes included MAD1L1, TWIST1, TMTC2, and TADA2B. RGS16 reinforces the proliferation and migration of EC cells [28]. TWIST1 can activate cancer stem cell marker genes, facilitating the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor progression of EC [29]. In this investigation, RGS16 and MAD1L1 were greatly positively linked with TWIST1. Moreover, in the immune analysis, TWIST1 was significantly positively linked with immune cells (macrophages and iDCs) (P < 0.001). TWIST1 can induce CCL2 and recruit macrophages to boost breast tumor angiogenesis [30]. However, TWIST1 was a protective factor as found in this research. The function of TWIST1 in EC necessitated further exploration. APLN can affect EC malignant progression through the miR-204-5p/APLN axis and the PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway [31, 32]. Liu et al. [33]. pointed out that the overexpression of TRIM28 may play an instrumental part in the occurrence and metastasis of EC. ARMCX, as a member of the armadillo gene family, is primarily clustered on the X chromosome and is also referred to as X-linked [34]. Previous studies have confirmed that ARMCX family members regulate the WNT signaling pathway by modulating the interaction between E-cadherin and transcription factors of the T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) family, which is closely associated with tumor progression [34, 35].The high expression of ARMCX2 has a bearing on poor prognosis in gastric cancer patients [34]. ARMCX2 has been found to undergo methylation in chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cells [36]. AKAP4, a member of the A-kinase anchoring protein family, is typically expressed only in human germ cells [37]. In recent years, AKAP4 has also been recognized as a novel tumor antigen and a promising biomarker in multiple cancers [38, 39]. Similarly, AKAP4 overexpression has been shown to promote EC cell migration and invasion, likely by regulating the expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers [37]. Mitotic arrest deficient-like 1 (MAD1L1) is a checkpoint gene whose altered expression is associated with chromosomal instability [40]. CHPF can directly interact with MAD1L1 to promote malignant progression in glioma by modulating the cell cycle [41]. Therefore, we conducted functional enrichment analysis on these four genes. The results showed that ARMCX2, TMTC2, and MAD1L1 were significantly enriched only in the high-expression group, and we displayed the top three enriched functions (Figure S1A–C). These findings suggest the need for further exploration and validation of the mechanistic roles of these signature genes in EC progression.

Due to the poor prognosis in Group H, we aimed to explore the reasons behind it. GSEA results showed that Group H was greatly enriched in multiple pathways, including base excision repair, cysteine and methionine metabolism, and porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism pathways. Among them, base excision repair was connected with platinum resistance in EC. When the excision repair-related gene ERCC1 is mutated or low levels of ERCC1 are expressed, EC patients are more sensitive to platinum chemotherapy [42]. DNA polymerase β is a key enzyme in the base excision repair system, and its deficiency boosts the occurrence of precancerous lesions in EC mice [43]. Cystatin 1 activates the VEGF-MAPK/ERK-MMP9/2 signaling axis and facilitates lymph node metastasis and lymphangiogenesis in ECs [44]. Another study manifested that cysteine protease inhibitor 1 can reinforce cancer cell metastasis by mediating the oxidative phosphorylation /MEK/ERK axis in ESCC [45]. Liu et al. [46]. pointed out that porphyrin photosensitizer treatment is effective in EC across different clinical stages, with adverse reactions being mild, making it a superior palliative treatment option.

The prognostic model established in this study has the potential to significantly impact clinical practice for EC patients. By stratifying patients into risk groups based on the model’s risk score, clinicians can identify high-risk patients for more intensive monitoring and consider more aggressive adjuvant therapies—such as intensified chemotherapy or targeted treatments—to mitigate recurrence risks and improve survival outcomes. Furthermore, the model’s application may vary across different clinical stages of EC. For early-stage EC patients, the model could help identify those with a higher risk of recurrence despite initially favorable prognoses. These patients may benefit from adjuvant therapies typically reserved for advanced cases, potentially improving their long-term survival rates. Conversely, for advanced-stage EC patients, the model could refine prognostic stratification, enabling more personalized treatment plans. For instance, Qi et al. [47] developed a novel prognostic model for EC using bioinformatics and network pharmacology based on immune-related genes. Their study demonstrated that the model could effectively distinguish pathological stage distributions between high- and low-risk groups and provided more accurate prognostic predictions for EC patients than conventional clinical features. Similarly, Sha et al. [48] constructed a prognostic model based on RNA-binding proteins, which not only enabled effective EC patient risk stratification but also exhibited strong diagnostic performance for the model genes. In summary, the practical application of our 10-gene prognostic model in clinical settings holds promise for improving personalized management of EC patients, guiding clinicians in selecting optimal treatment intensity and strategies.

Through a series of bioinformatics analyses, this research constructed a well-performing 10-gene prognostic model related to tumor invasion. The feature gene ZC3H12B had strong interactions with other prognostic genes and multiple immune cells. The mutation rate of this gene was relatively high. Research limitations still exist, as follows: Firstly, this study is a pure bioinformatics analysis based on public data, and the clinical applicability of this model needs to be verified clinically. Second, the sample size in the database is relatively limited, which may bias the results of the study. Therefore, we plan to expand the sample size and conduct prospective clinical trials in the future to further validate the reliability of our prognostic model. Finally, the extent of interaction between ZC3H12B and other prognostic feature genes and its relationship with tumor progression has not been explored in depth. In future research, we will deeply dig out the function of prognostic feature genes through cell experiments and mouse experiments. In summary, the prognostic model can help identify EC patients who are more likely to experience adverse outcomes, allowing for early intervention of the disease. Secondly, by predicting the possible future progression of the disease, the research can provide patients with more personalized treatment recommendations. This research also provides valuable data for subsequent EC clinical trials, laying the groundwork for further research on this tumor.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Xueqiong Deng contributed to the study design and wrote the manuscript. Yiming Liu conducted the literature search and acquired the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. 10.3322/caac.21834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma P, Barrett Esophagus A, Review. JAMA. 2022;328(7):663–71. 10.1001/jama.2022.13298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katada C, Yokoyama T, Yano T, Suzuki H, Furue Y, Yamamoto K, Doyama H, Koike T, Tamaoki M, Kawata N, et al. Alcohol consumption, multiple Lugol-voiding lesions, and field cancerization. DEN Open. 2024;4(1):e261. 10.1002/deo2.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tay SW, Li JW, Fock KM. Diet and cancer of the esophagus and stomach. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021;37(2):158–63. 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou X, Ren T, Zan H, Hua C, Guo X. Novel immune checkpoints in esophageal cancer: from biomarkers to therapeutic targets. Front Immunol. 2022;13:864202. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.864202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He S, Xu J, Liu X, Zhen Y. Advances and challenges in the treatment of esophageal cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11(11):3379–92. 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo X, Zhu R, Luo A, Zhou H, Ding F, Yang H, Liu Z. EIF3H promotes aggressiveness of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by modulating snail stability. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):175. 10.1186/s13046-020-01678-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang M, Li Y, Xiao Y, Yang M, Chen J, Jian Y, Chen X, Shi D, Chen X, Ouyang Y, et al. Nicotine-mediated OTUD3 downregulation inhibits VEGF-C mRNA decay to promote lymphatic metastasis of human esophageal cancer. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):7006. 10.1038/s41467-021-27348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuji T, Matsuda S, Takeuchi M, Kawakubo H, Kitagawa Y. Updates of perioperative multidisciplinary treatment for surgically resectable esophageal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2023;53(8):645–52. 10.1093/jjco/hyad051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forjaz G, Ries L, Devasia TP, Flynn G, Ruhl J, Mariotto AB. Long-term Cancer survival trends by updated summary stage. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32(11):1508–17. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-23-0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu N, Cai J, Jiang J, Lin Y, Wang X, Zhang W, Kang M, Zhang P. Biomarkers of lymph node metastasis in esophageal cancer. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1457612. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1457612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph A, Raja S, Kamath S, Jang S, Allende D, McNamara M, Videtic G, Murthy S, Bhatt A. Esophageal adenocarcinoma: A dire need for early detection and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2022;89(5):269–79. 10.3949/ccjm.89a.21053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu W, Zhang Y, Li X, Wang X, Yuan Y. miR-375 inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by targeting XPR1. Curr Gene Ther. 2021;21(4):290–8. 10.2174/1566523220666201229155833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Han Y, Xiao W, Gao Y, Sui Z, Ren P, Meng F, Tang P, Yu Z. USP4 promotes the proliferation, migration, and invasion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by targeting TAK1. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(11):730. 10.1038/s41419-023-06259-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan H, Yan M, Zhang G, Liu W, Deng C, Liao G, Xu L, Luo T, Yan H, Long Z, et al. CancerSEA: a cancer single-cell state atlas. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D900–8. 10.1093/nar/gky939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang Y, Yang Y, Zhang X, Li N, Yuan B, Jin L, Bao S, Li M, Zhao D, Li L, et al. A Co-Expression network reveals the potential regulatory mechanism of LncRNAs in relapsed hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:745166. 10.3389/fonc.2021.745166. From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yi C, Liu J, Deng W, Luo C, Qi J, Chen M, Xu H. Macrophage elastase (MMP12) critically contributes to the development of subretinal fibrosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):78. 10.1186/s12974-022-02433-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su Z, He Y, You L, Zhang G, Chen J, Liu Z. Coupled scRNA-seq and Bulk-seq reveal the role of HMMR in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1363834. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1363834. From NLM Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Z, Wang J, Fan Z, Yang Y, Meng X, Ma Z, Niu J, Guo R, Tran LJ, Zhang J, et al. Investigating the prognostic role of LncRNAs associated with disulfidptosis-related genes in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Gene Med. 2024;26(1):e3608. 10.1002/jgm.3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar R, Lathwal A, Kumar V, Patiyal S, Raghav PK, Raghava GPS, CancerEnD. A database of cancer associated enhancers. Genomics. 2020;112(5):3696–702. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Y, Liu J, Liang D. Comprehensive analysis reveals key genes and environmental toxin exposures underlying treatment response in ulcerative colitis based on in-silico analysis and Mendelian randomization. Aging. 2023;15(23):14141–71. 10.18632/aging.205294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farinelli A, Bedani PL, Gilli P. [Renal osteodystrophy. Physiopathological and clinical aspects]. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1986;38(4):417–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan X, Jin X, Wang J, Hu Q, Dai B. Placenta inflammation is closely associated with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13(5):4068–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng X, Ma Y, Bai Y, Huang T, Lv X, Deng J, Wang Z, Lian W, Tong Y, Zhang X, et al. Identification and validation of immunotherapy for four novel clusters of colorectal cancer based on the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2022;13:984480. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.984480. From NLM Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen A, Ye Y, Chen F, Xu Y, Zhang Z, Zhao Q, Zeng ZL. Integrated multi-omics analysis identifies CD73 as a prognostic biomarker and immunotherapy response predictor in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2022;13:969034. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.969034. From NLM Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wawro M, Wawro K, Kochan J, Solecka A, Sowinska W, Lichawska-Cieslar A, Jura J, Kasza A. ZC3H12B/MCPIP2, a new active member of the ZC3H12 family. RNA. 2019;25(7):840–56. 10.1261/rna.071381.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Y, Xu M, Jing C, Wu X, Chen X, Zhang W. Extracellular vesicle-derived miR-320a targets ZC3H12B to inhibit tumorigenesis, invasion, and angiogenesis in ovarian cancer. Discov Oncol. 2021;12(1):51. 10.1007/s12672-021-00437-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Zhu Q, Cao X, Ni B. RGS16 regulates Hippo-YAP activity to promote esophageal cancer cell proliferation and migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2023;675:122–9. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2023.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khales SA, Mozaffari-Jovin S, Geerts D, Abbaszadegan MR. TWIST1 activates cancer stem cell marker genes to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumorigenesis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):1272. 10.1186/s12885-022-10252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Low-Marchelli JM, Ardi VC, Vizcarra EA, van Rooijen N, Quigley JP, Yang J. Twist1 induces CCL2 and recruits macrophages to promote angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2013;73(2):662–71. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou Y, Xu R, Luo J, Li X, Zhong Y, Sun Z. Dysregulation of miR-204-5p/APLN axis affects malignant progression and cell stemness of esophageal cancer. Mutat Res. 2022;825:111791. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2022.111791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Wang G, Liu X, Yun D, Cui Q, Wu X, Lu W, Yang X, Zhang M. Inhibition of APLN suppresses cell proliferation and migration and promotes cell apoptosis in esophageal cancer cells < em > in vitro, through activating PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway. Eur J Histochem. 2022;66(3). 10.4081/ejh.2022.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Liu B, Li X, Liu F, Li F, Wei S, Liu J, Lv Y. Expression and significance of TRIM 28 in squamous carcinoma of esophagus. Pathol Oncol Res. 2019;25(4):1645–52. 10.1007/s12253-018-0558-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang T, Zhong H, Qin Y, Wei W, Li Z, Huang M, Luo X. ARMCX family gene expression analysis and potential prognostic biomarkers for prediction of clinical outcome in patients with gastric carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020(3575038). 10.1155/2020/3575038. From NLM Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Iseki H, Takeda A, Andoh T, Takahashi N, Kurochkin IV, Yarmishyn A, Shimada H, Okazaki Y, Koyama I. Human arm protein lost in epithelial cancers, on chromosome X 1 (ALEX1) gene is transcriptionally regulated by CREB and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(6):1361–6. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01541.x. From NLM Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeller C, Dai W, Steele NL, Siddiq A, Walley AJ, Wilhelm-Benartzi CS, Rizzo S, van der Zee A, Plumb JA, Brown R. Candidate DNA methylation drivers of acquired cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer identified by methylome and expression profiling. Oncogene. 2012;31(42):4567–76. 10.1038/onc.2011.611. From NLM Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li S, Qin X, Li Y, Guo A, Ma L, Jiao F, Chai S. AKAP4 mediated tumor malignancy in esophageal cancer. Am J Translational Res. 2016;8(2):597–605. From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang B, Hu Q, Zhang J, Jin Z, Ruan Y, Xia L, Wang C. Silencing of A-kinase anchor protein 4 inhibits the metastasis and growth of non-small cell lung cancer. Bioengineered. 2022;13(3):6895–907. 10.1080/21655979.2021.1977105. From NLM Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Q, Tang H, Hu F, Qin C. Knockdown of A-kinase anchor protein 4 inhibits hypoxia-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via suppression of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in human gastric cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(12):10013–20. 10.1002/jcb.27331. From NLM Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun Q, Zhang X, Liu T, Liu X, Geng J, He X, Liu Y, Pang D. Increased expression of mitotic arrest deficient-like 1 (MAD1L1) is associated with poor prognosis and insensitive to taxol treatment in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;140(2):323–30. 10.1007/s10549-013-2633-8. From NLM Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo H, Huang K, Cheng M, Long X, Zhu X, Wu M. The HNF4A-CHPF pathway promotes proliferation and invasion through interactions with MAD1L1 in glioma. Aging. 2023;15(20):11052–66. 10.18632/aging.205076 From NLM Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhuo ZG, Zhu YK, Deng HY, Li G, Luo J, Alai GH, Lin YD. Predictive value of excision repair Cross-Complementation group 1 in the response to Platinum-Based chemotherapy in esophageal cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Oncol Res Treat. 2020;43(4):160–9. 10.1159/000505378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qin J, Zhu Y, Ding Y, Niu T, Zhang Y, Wu H, Zhu L, Yuan B, Qiao Y, Lu J, et al. DNA polymerase beta deficiency promotes the occurrence of esophageal precancerous lesions in mice. Neoplasia. 2021;23(7):663–75. 10.1016/j.neo.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo J, Song Z, Muming A, Zhang H, Awut E. Cysteine protease inhibitor S promotes lymph node metastasis of esophageal cancer cells via VEGF-MAPK/ERK-MMP9/2 pathway. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2024;397(8):6051–9. 10.1007/s00210-024-03014-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang L, Chen X, Wang J, Chen M, Chen J, Zhuang W, Xia Y, Huang Z, Zheng Y, Huang Y. Cysteine protease inhibitor 1 promotes metastasis by mediating an oxidative phosphorylation/mek/erk axis in esophageal squamous carcinoma cancer. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):4985. 10.1038/s41598-024-55544-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu H, Liu Y, Wang L, Ruan X, Wang F, Xu D, Zhang J, Jia X, Liu D. Evaluation on Short-Term therapeutic effect of 2 porphyrin Photosensitizer-Mediated photodynamic therapy for esophageal Cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2019;18:1533033819831989. 10.1177/1533033819831989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qi P, Qi B, Gu C, Huo S, Dang X, Liu Y, Zhao B. Construction of an immune-related prognostic model and potential drugs screening for esophageal cancer based on bioinformatics analyses and network Pharmacology. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2024;12(5):e1266. 10.1002/iid3.1266. From NLM Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sha Y, Reyimu A, Liu W, He C, Kaisaier A, Paerhati P, Li L, Zou X, Xu A, Cheng X, et al. Construction and validation of a prognostic model for esophageal cancer based on prognostic-related RNA-binding protein. Med (Baltim). 2024;103(37):e39639. 10. 1097/MD.0000000000039639 From NLM Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.