Abstract

The World Health Organization declared a global pandemic in March 2020, the virus has infected and killed millions of individuals worldwide without discrimination. Due to the lack of SARS-CoV-2-specific treatment options and rapidly mutating variants, the virus triggered waves of infection and death. Computer-assisted drug design techniques have allowed rapid virtual screening and molecular docking for the identification of numerous biological hit compounds. The Schrodinger glide software was used to perform high-throughput virtual screening on a database of 2055 flavonoid derivative compounds against the SARS-CoV-2 main protease 6LU7. The Glide Docking scores narrowed the database to ten hit molecules with the PubChem CIDs 1882879, 1866522, 941256, 5703289, 626515, 1974731, 654250, 5490127, 941927, and 5282073. Their scores ranged between −8.073, −7.981, −7.754, −7.933, −7.911, −7.903, −7.875, −7.854, −7.826, and −7.821 kcal/mol, respectively. They were also studied for their binding properties, including binding interactions, binding orientation and binding energies.

Keywords: Flavonoids dataset, SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) inhibitors, High-throughput virtual screening (HTVS), Molecular docking

Specifications Table

| Subject | Pharmaceutical Sciences – Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) |

| Specific subject area | Structure-Based Drug Desing (SBDD) and virtual screening of databases of flavonoids as prospective SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro) Inhibitors. |

| Type of data | Raw data of protein target curation and molecular docking-based high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) for 2055 PubChem compounds are presented in tables. |

| Data collection | Molecular docking-based HTVS screening for the identification of virtual drug-like molecules related to flavonoids basic scaffold search in PubChem database. |

| Data source location | Institution: School of Postgraduate Studies, IMU University (Formerly known as International Medical University) City/Town/Region: Kuala Lumpur Country: Malaysia |

| Data accessibility | Avupati, Vasudeva Rao; Eema, Mariyam (2024), “Curation data of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro) PDB entries and Glide_High-throughput virtual screening (HTVS)_Flavonoids Docking Scores”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/bt4ycypphk.1 Link: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/bt4ycypphk/1 |

| Related research article | None |

1. Value of the Data

-

•

The molecular docking simulation-based virtual screening data presented in this article is of greater importance for the design, discovery, and development of new molecules consisting of a flavonoid scaffold as prospective novel SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor.

-

•

The predicted molecular docking simulation could be useful to explore the virtual binding properties such as binding energy, binding interactions, and binding roles of the hit molecules consisting of a flavonoid backbone to develop as novel SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors.

-

•

The predicted molecular docking simulation data also helps researchers to review the binding profile of flavonoids within the catalytic binding site region of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

-

•

The acquired data revealed the variability of chemical structural features with respect to the flavonoids binding potential to the SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

2. Background

One promising target that has emerged from the proteins encoded by the SARS-CoV-2 genome is main protease, Mpro [[1], [2], [3]]. By selectively utilising different flavonoids to target SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, numerous in silico studies have revealed positive outcomes. The SARS-CoV-2 Mpro structure's 3D protein structure ID for PBD: 6LU7 is the primary target of most molecular docking investigations. In a large-scale in silico investigation, Rameshkumar et al. virtually screened 458 flavonoids and reduced the field to 36 molecules based on interaction energy values > −9 kcal/mol. Individual docking of each of the top 10 lead compounds against protein targets was performed. According to the findings, agathisflavone binds to major proteases with the maximum binding energy value of −8.4 kcal/mol [4]. In a different study conducted by Ghosh et al., eight polyphenols from green tea were chosen because they were already known to have antiviral effects on a variety of RNA viruses. According to his findings, all eight of them had strong binding affinities for Mpro, with binding energies ranging from −7.1 to −9.0 kcal/mol. Only three polyphenols, namely gallocatechin-3-gallate, epicatechin-gallate, and epigallocatechin gallate, were discovered to have substantial interactions with either one or both of Mpro's catalytic residues (His41 and Cys145) [5]. Numerous flavonoids have higher Mpro affinities and lower binding energies than commonly prescribed medications, according to recent investigations. Hesperidin, rhoifolin, and pectolinarin exhibited greater binding affinity to Mpro than the antiviral medications, according to a study comparing them to chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine (pre-existing antiviral malaria drugs) [6]. Another study found that hesperidin had a binding free energy of −8.6 kcal/mol when the flavonoid components in an orange peel (Citrus sp.) were examined. It was comparatively higher than the binding free energy of nelfinavir, an antiviral medication already on the market used to treat HIV (−8.6 kcal/mol) [7]. Hesperidin was also recognised by Hadni et al. as a possible Mpro inhibitor, along with Bilobetin, Silibinin, Amentoflavone, Tomentin A, Tomentin B, and 4′-O-methuldiplacone [8]. However, rutin was found to be the most effective inhibitor in a study comparing the activity of hesperidin, rutin, and other medications including ritonavir, emetine, and lopinavir in the binding site of SARS-Cov-2 Mpro 6Y84 [9]. Several more studies with rutin also revealed positive outcomes. Out of 38 glycosylated flavonoids, Cherrak et al. were able to pinpoint the three substances that had the highest affinity for the active site. They were quercetin-3-rhamonoside and myricetin-3-rutinoside in addition to rutin, and their binding energies were −9.2, −9.7, and −9.3 correspondingly (86). Teli et al. virtually tested 170 substances and identified acetoside, solanine, and rutin as inhibitors of the Mpro and spike glycoprotein dual receptors. Additionally discovered to covalently block Mpro were acetoside and curcumin[10]. A study using the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro 6YNQ supported these findings by showing that rutin had the maximum binding energy (−8.7 kcal/mol) among 21 chosen flavonoids and indicated perfect interaction with the catalytic sites [11].

The purpose of this study was to perform a molecular docking simulation-based virtual screening using a database of flavonoid derivatives against SARS-CoV-2 main protease 6LU7. Furthermore, the in silico stable binding properties such as binding energy, binding interaction and binding orientation of the top 10 hit compounds was analysed based on Glide Docking scores, with the lowest scores prioritized. While previous studies have been conducted on flavonoids, this study utilises a much larger database consisting of 2055 derivatives with the intention of speeding up SARS-CoV-2 specific drug development efforts. Summarized below (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, Fig. 11, Fig. 12, Fig. 13, Fig. 14, Fig. 15, Fig. 16, Fig. 17, Fig. 18, Fig. 19, Fig. 20, Table 1) are the binding orientation, ligand-interaction diagrams and docking scores of 10 hit molecules out of the with the most stable binding conformations out of the 2055 flavonoid derivatives with their chemical structure and Glide Docking Scores. They potentially exhibit inhibitory activity against the main protease 6LU7. Docking studies on the 10 hit molecules of flavonoid derivative compounds showed hydrogen bonding with the residues HID 164, HID 163, LEU 141, GLU 166, SER 144, and GLY 143. The most common residue appears to be LEU 141. The number of hydrogen bonds ranged from 1 to 3, with most of the hit molecules having just 1 H-bond. Table 1 below summarizes this information accordingly.

Fig. 1.

Three-dimensional (3D) binding orientation of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 1 (PubChem CID: 1882879) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

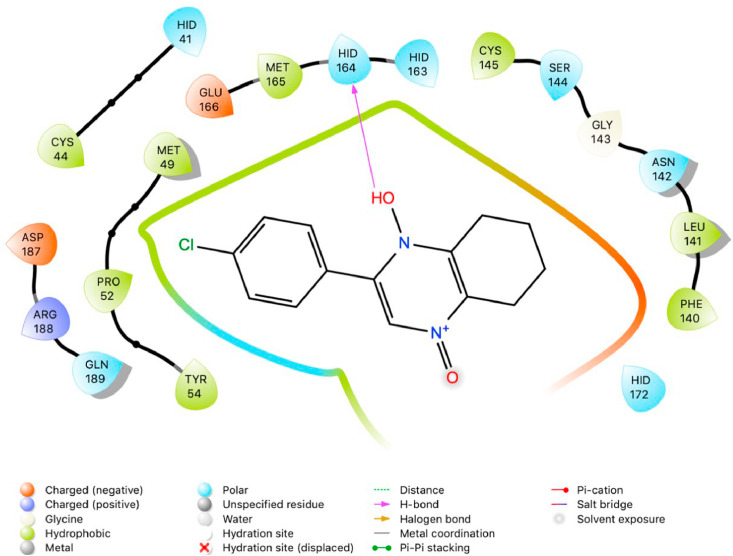

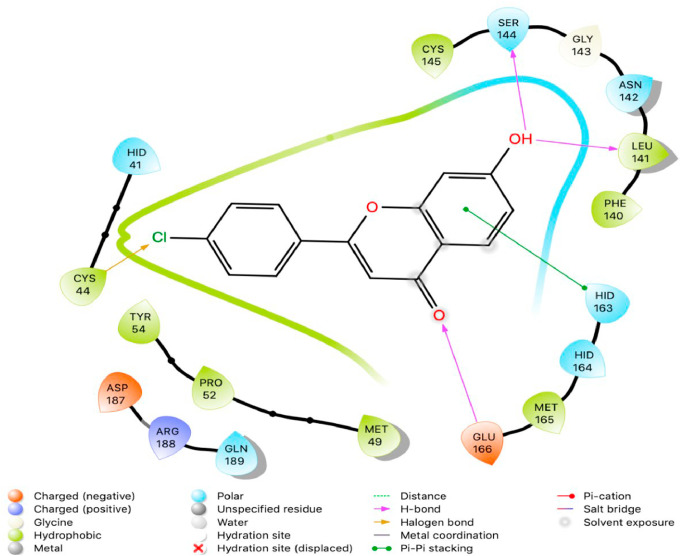

Fig. 2.

Two-dimensional (2D) Ligand Interaction Diagram (LID) of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 1 (PubChem CID: 1882879) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 3.

Three-dimensional (3D) binding orientation of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 2 (PubChem CID: 1866522) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

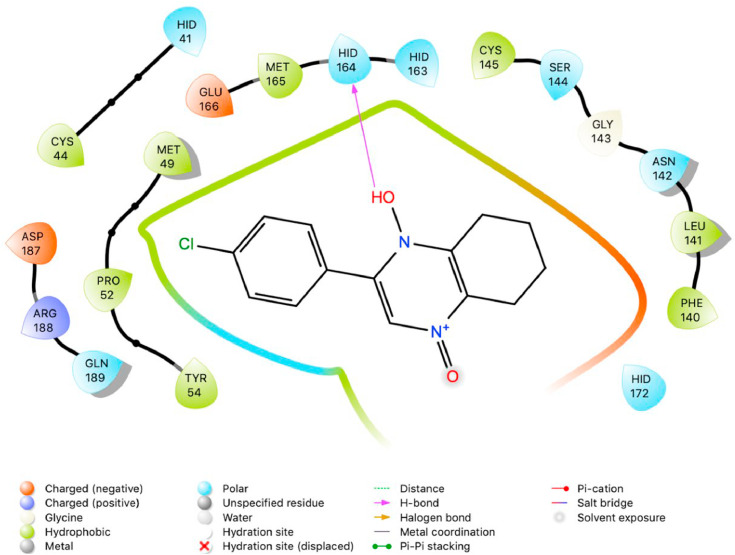

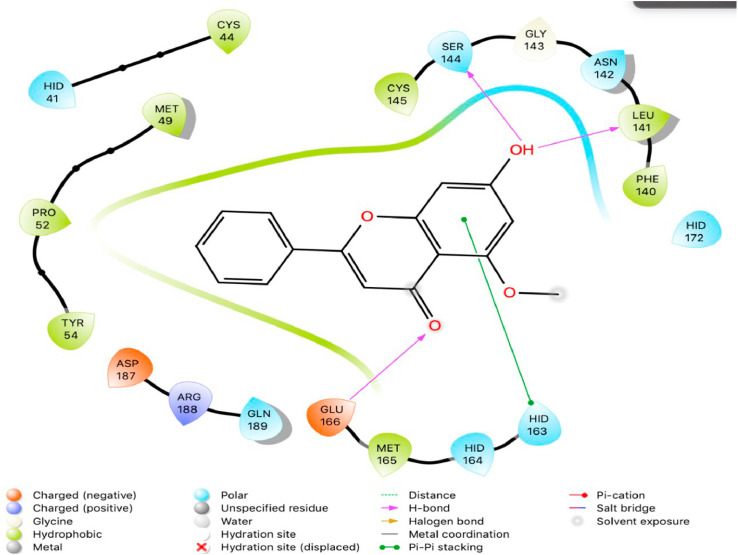

Fig. 4.

Two-dimensional (2D) Ligand Interaction Diagram (LID) of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 2 (PubChem CID: 1866522) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

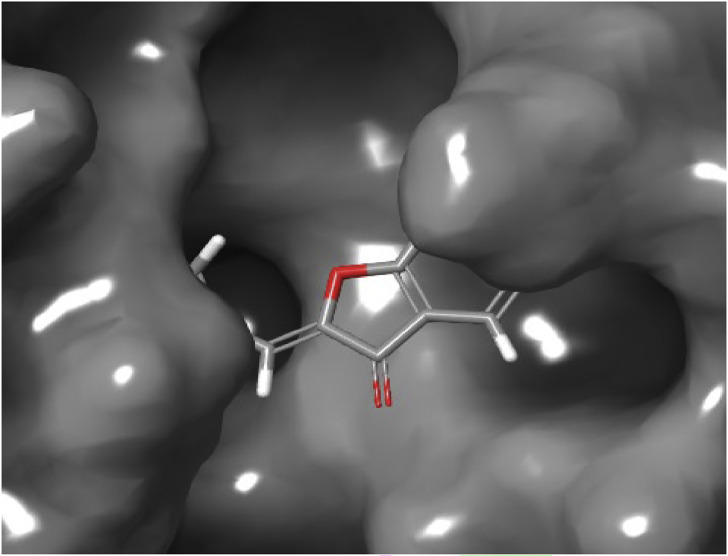

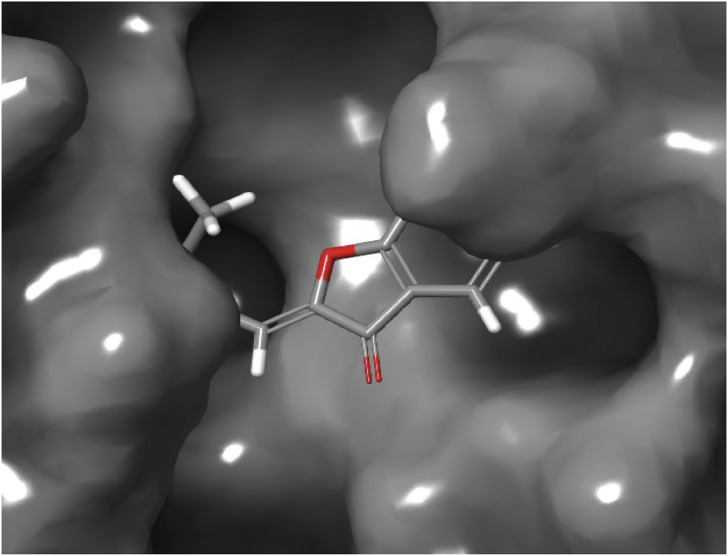

Fig. 5.

Three-dimensional (3D) binding orientation of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 3 (PubChem CID: 941256) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

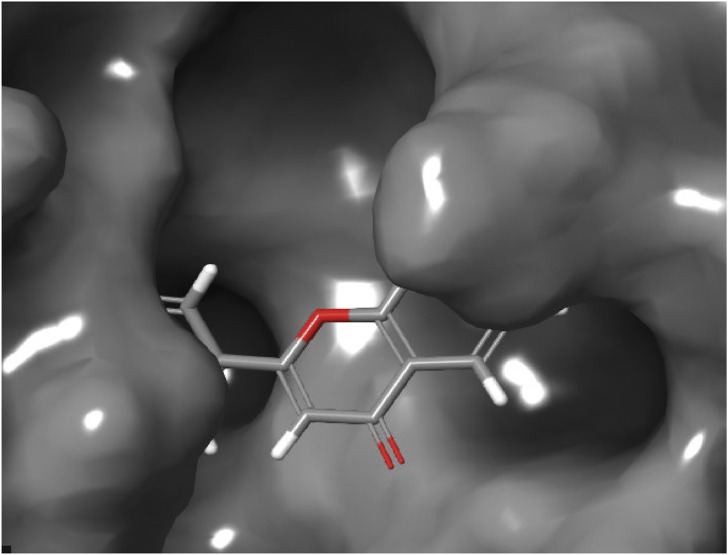

Fig. 6.

Two-dimensional (2D) Ligand Interaction Diagram (LID) of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 3 (PubChem CID: 941256) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 7.

Three-dimensional (3D) binding orientation of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 4 (PubChem CID: 5703289) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 8.

Two-dimensional (2D) Ligand Interaction Diagram (LID) of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 4 (PubChem CID: 5703289) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 9.

Three-dimensional (3D) binding orientation of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 5 (PubChem CID: 626515) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 10.

Two-dimensional (2D) Ligand Interaction Diagram (LID) of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 5 (PubChem CID: 626515) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 11.

Three-dimensional (3D) binding orientation of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 6 (PubChem CID: 1974731) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 12.

Two-dimensional (2D) Ligand Interaction Diagram (LID) of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 6 (PubChem CID: 1974731) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 13.

Three-dimensional (3D) binding orientation of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 7 (PubChem CID: 654250) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 14.

Two-dimensional (2D) Ligand Interaction Diagram (LID) of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 7 (PubChem CID: 654250) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 15.

Three-dimensional (3D) binding orientation of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 8 (PubChem CID: 5490127) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 16.

Two-dimensional (2D) Ligand Interaction Diagram (LID) of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 8 (PubChem CID: 5490127) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 17.

Three-dimensional (3D) binding orientation of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 9 (PubChem CID: 941927) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 18.

Two-dimensional (2D) Ligand Interaction Diagram (LID) of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 9 (PubChem CID: 941927) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 19.

Three-dimensional (3D) binding orientation of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 10 (PubChem CID: 5282073) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Fig. 20.

Two-dimensional (2D) Ligand Interaction Diagram (LID) of the virtual screening hit molecule ranked 10 (PubChem CID: 5282073) at the active binding site region of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Table 1.

Summary of top 10 flavonoid hit molecules identified by High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) using Glide molecular docking simulation protocol.

| PubChem CID of the Hit Molecule | Two dimensional (2D) Chemical Structure of the Hit Compound | High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) Glide Docking Score (kcal/mol) of the Hit Molecule | Number of H-bonds formed at the target binding site | Hydrogen bond forming amino acids at the target binding site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1882879 |  |

−8.073 | 1 | HID 164 |

| 1866522 |  |

−7.981 | 1 | HID 164 |

| 941256 |  |

−7.954 | 2 | LEU 141 GLU 166 |

| 5703289 |  |

−7.933 | 3 | SER 144 GLU 166 LEU 141 |

| 626515 |  |

−7.911 | 3 | HID 163 SER 144 GLY 143 |

| 1974731 |  |

−7.903 | 1 | HID 164 |

| 654250 |  |

−7.875 | 1 | HID 164 |

| 5490127 |  |

−7.854 | 3 | GLU 166 SER 144 LEU 141 |

| 941927 |  |

−7.826 | 2 | GLU 166 LEU 141 |

| 5282073 |  |

−7.821 | 2 | SER 144 LEU 141 |

3. Data Description

4. Experimental Design, Materials and Methods

4.1. Target protein selection and preparation

The RCSB PDB is a global resource that allows access to annotated information about the three-dimensional (3D) structures of macromolecules (e.g., nucleic acids, proteins) and associated small molecules (e.g., medicines, cofactors, inhibitors) in the PDB archive, thereby supporting the study of these structures and their interactions. In addition, they encourage the development of standards that govern the deposition, representation, annotation, and validation of atomic structure data obtained through a wide range of experimental techniques. It is crucial that all PDB data be represented uniformly in order to provide consistent search and analysis capabilities to all PDB users. Constant efforts are being made to establish a more consistent and comprehensive archive, along with the capacity to browse, search, and report data. The SARS-CoV-2 Mpro 6LU7 drug target protein was selected by systematic analysis of the database of protein entries deposited in the protein data bank server. The RCSB PDB database provides a COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 resource page with access to all SARS-CoV-2 PDB structures. The section titled "main proteases" contains 647 structures. Each main protease was scrutinised individually, and the final protein target for docking (PDB ID: 6LU7) was chosen using a specific criterion comprising multiple factors [12].

First, the structure of the target must be determined by X-ray diffraction spectroscopy with a resolution between 1.0 and 3.0 Å (the lower the value, the higher the resolution). According to RCSB PDB, 6LU7 protein target structure was determined by X-ray diffraction spectroscopy with a resolution of 2.16 Å. Second, it must contain a co-crystallized ligand complex with no breaks in its 3D protein structure. Third, for the Ramachandran plot statistics, none of the residues should exist in disallowed regions. The PDBsum website (www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbsum/) was consulted to establish that the 6LU7 protein contained a co-crystallized ligand complex with no protein breaks in its 3D structure and to discern that, according to Ramachandran plot statistics, 90.6 % of residues were located in the most favoured region and 0.4 % in the disallowed region.

Finally, the resultant target docking protein's database was prepared in such a way that all heteroatoms (i.e., non-receptor atoms such as water, ions) were removed and subjected to molecular docking simulation steps. These include specifying the receptor grid, selecting the docking precision, setting the docking options, specifying the source of the ligands, setting the docking output properties and finally visualising docking results respectively by using GPU licensed molecular visualisation software like Rasmol or Raswin and Swiss PDB viewer. Following are the steps in brief.

-

Step 1:

The RCSB PDB website was accessed.

-

Step 2:

The COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 Resource page was accessed and ‘Main proteases’ section was selected

-

Step 3:

Spectroscopy method and resolution was assessed on RCSB PDB website for protein targets.

-

Step 4:

The PDBsum website was accessed.

-

Step 5:

The protein target was searched.

-

Step 6:

In the ‘Protein’ section, the presence / absence of chain breaks was checked.

-

Step 7:

The Ramachandran plot was checked.

-

Step 8:

The Ramachandran Plot statistics were checked.

4.2. Ligand selection and preparation

The chemical structures of flavonoids were selected through the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). These compounds were subjected for molecular modelling using ChemDraw software, and the modelled structures then imported into ChemDraw3D software to create a database of 3D energy minimised ligands. Energy minimised structures were considered for molecular docking-based virtual screening processes.

-

Step 1:

The PubChem database was accessed to prepare the ligand database for virtual screening.

-

Step 2:

The basic chemical scaffold of the flavonoids (Flavan) was used to search the database using a set of search filters.

-

Step 3:

The two-dimensional chemical structure of the “Flavan” was drawn using ChemDraw software and the SMILES code: C1(C2=CC CC C2)CCC3=C(O1)C CC C3 was extracted to initiate the search on the PubChem Database.

-

Step 4:

The search yielded 19,051 compounds based on the 3D similarity search and other structural properties including rotatable bond count, heavy atom count, H-bond donor count, H-bond acceptor count, polar area (Ų), and XLogP, which were used as filtering criteria from 2004 to 2022, a total of 18 years, to prepare the ligand database for screening. The compounds were organised into a series based on the PubChem databaseʼs CID code. Subsequently, this database was imported into the Entrez database in order to refine its properties. The database was reduced to 17,172 compounds using the Rule of Five as the first filter under the chemical properties category. The database was then further reduced to 5602 compounds by selecting 'Bioassay Tested' under the Bioactivity Experiments category. Finally, the refinement was extended to the selection of the depositor category, NIH molecular libraries, for a more authentic database creation, resulting in 2054 flavonoids in the database. The three-dimensional structures of the compounds were retrieved from the PubChem database as a 3D coordinate type, non-compressed SDF file with conformation number equal to 1. For computational molecular docking-based virtual screening, SDF files are the most frequently used molecular modelling format.

4.3. Molecular docking simulation-based virtual screening procedure

-

Step 1:

After downloading the flavonoid derivates from PubChem database, the compounds were uploaded into Maestro platform for molecular modelling. The database of 2055 three-dimensional molecules were subjected to the energy minimization using LigPrep software via OPLUS forcefield.

-

Step 2:

Next, the protein target PDB ID: 6LU7 was downloaded on to the workplace and further subjected to protein preparation using the Schrodinger Protein Preparation Wizard. The protein target was pre-processed, followed by energy minimization.

-

Step 3:

The energy minimized target protein was subjected to binding site preparation using Schrodinger Glide Receptor Grid Generation software. Then, the prepared binding site file and prepared ligand database were used for performing molecular docking studies using Glide.

-

Step 4:

Schrodinger Glide “ligand docking” module was used to perform High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS), after which the docking results were used to analyse the binding properties and molecule hits against the selected SARs-CoV-2 main protease target protein.

4.4. Outcomes

The present global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has boosted the utilization of in silico drug development techniques. In contrast to traditional drug development approaches, its appeal is due to its low cost and faster and more efficient development of life-saving treatments. This can expedite the creation of effective treatments that potentially save countless lives. In this study, 2055 flavonoid derivative compounds were subjected to a high-throughput virtual screening against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro 6LU7 by using Schrodinger software. Ten hit molecules with the lowest Glide Docking scores were selected and their binding properties, including binding interactions, binding orientation, and binding energy, were studied. These values approximate the ligand binding free energy. In this study, it was noted that scores − 8.073 kcal/mol or below indicates efficient binding. Table provides a summary of the hit molecules and their scores. They have the power to inhibit 6LU7, hence interfering with the replication and transcription abilities of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Within the dataset of flavonoid derivatives downloaded from the PubChem database, Among the identified compounds, PubChem CID 1882879 (3-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-oxido-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinoxalin-1-ium 1-oxide) exhibited a binding energy of −8.073 kcal/mol and formed 1 hydrogen bond with HID 164. PubChem CID 1866522 (3-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-oxido-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinoxalin-1-ium 1-oxide) demonstrated a binding energy of −7.981 kcal/mol with 1 hydrogen bond to HID 164. PubChem CID 941256 ((2Z)-6‑hydroxy-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)−4-oxo-1H-pyran-3-carboxylic acid) had a binding energy of −7.954 kcal/mol, forming 2 hydrogen bonds with LEU 141 and GLU 166. PubChem CID 5703289 (5,7-dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)−4H-1-benzopyran-4-one) achieved a binding energy of −7.933 kcal/mol with 3 hydrogen bonds to SER 144, GLU 166, and LEU 141. PubChem CID 626515 (5,7-dihydroxy-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)−2-(3,4-dihydroxybenzyl)-4H-chromen-4-one) presented a binding energy of −7.911 kcal/mol, forming 3 hydrogen bonds with HID 163, SER 144, and GLY 143. Additionally, PubChem CID 1974731 (5,7-dihydroxy-2-(3‑hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)−4H-chromen-4-one) had a binding energy of −7.903 kcal/mol with 1 hydrogen bond to HID 164, while PubChem CID 654250 (5,7,3′,4′-tetrahydroxyflavanone) showed a binding energy of −7.875 kcal/mol with 1 hydrogen bond to HID 164. PubChem CID 5490127 (3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxyflavone) exhibited a binding energy of −7.854 kcal/mol, forming 1 hydrogen bond with HID 164. PubChem CID 941927 (2,3-dihydro-3,5,7-trihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)−4H-1-benzopyran-4-one) had a binding energy of −7.826 kcal/mol, forming 1 hydrogen bond with HID 164. Finally, PubChem CID 5282073 (5,7,3′,4′-tetrahydroxyflavone) displayed a binding energy of −7.821 kcal/mol, forming 2 hydrogen bonds with SER 144 and LEU 141. The binding site residues for these compounds included THR 24, THR 25, THR 26, HIS 41, PHE 140, LEU 141, ASN 142, GLY 143, CYS 145, HIS 163, HIS 164, MET 165, GLU 166, PRO 168, HIS 172, GLN 189, THR 190, ALA 191, and GLN 192. The study hypothesizes that these compounds, particularly those forming hydrogen bonds with key residues like LEU 141 and GLU 166; could significantly inhibit the protease activity of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro 6LU7, literature also revealed that interaction with these amino acids is significant for binding to the target site and exhibits inhibitory properties [12].

In summary, this study identified ten hit molecules in a database of flavonoid derivatives which have the potential to inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The application of molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations has facilitated the acceleration of drug screening, significantly reduced the cost of drug design, and continued to increase the process' accuracy and efficiency. Ten compounds with the PubChem CIDs 1882879, 1866522, 941256, 5703289, 626515, 1974731, 654250, 5490127, 941927, and 5282073 have indeed been identified in this study as potential SARS-CoV-2 infection treatments. These compounds had the lowest binding scores among 2055 flavonoid compounds, indicating strong binding with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro 6LU7 and weak binding with off-target molecules. Consequently, essential viral replication and transcription processes can be strongly inhibited with minimal adverse effects on patients. Presently, no biological experiments have been carried out for this research. These compounds must undergo structural optimization, in vitro studies, in vivo studies, and human clinical trials in order to become viable drug candidates. This will enhance the compound's physicochemical properties and allow for the enhancement of potency while reducing undesirable side effects. The final product will be a clinically useful medication with well-established efficacy, safety at confirmed dosages, and good patient tolerance.

The novel SARS-CoV-2 virus first made headlines in December 2019. However, the world was woefully underprepared for this virus's aggressiveness. Since the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic in March 2020, the virus has infected and killed millions of individuals worldwide without discrimination. Due to the lack of SARS-CoV-2-specific treatment options and rapidly mutating variants, the virus triggered waves of infection and death. Computer-assisted drug design techniques have allowed rapid virtual screening and molecular docking for the identification of numerous biological hit compounds. This study used the Schrodinger software to perform high-throughput virtual screening on a database of 2055 flavonoid derivative compounds against the SARS-CoV-2 main protease 6LU7. The Glide Docking scores narrowed the database to ten hit molecules with the PubChem CIDs 1882879, 1866522, 941256, 5703289, 626515, 1974731, 654250, 5490127, 941927, and 5282073. Their scores ranged between −8.073, −7.981, −7.754, −7.933, −7.911, −7.903, −7.875, −7.854, −7.826, and −7.821 kcal/mol, respectively. They were also studied for their binding properties, including binding interactions, binding orientation and binding energies. The compounds had hydrogen bonds ranging from 1 to 3, and the hydrogen bond interacting residues were HID 164, LEU 141, GLU 166, SER 144, HID 163, and GLY 143. Ligands with the capability to form hydrogen bond interactions with these amino acids that are essential for viral replication and transcription can significantly suppress the protease activity of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Hence, this information demonstrates that these compounds have the potential to inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 main protease 6LU7. These compounds can be developed into viable drug candidates following structural optimization, in vitro studies, in vivo studies, and human clinical trials. Hopefully, other scientists can use the results of this study to develop lifesaving treatments for those affected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In conclusion, high-throughput molecular docking simulations confirmed that these ten compounds can form stable conformational structures with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro 6LU7 and can successfully inhibit the virus. It is hoped that this study provides research ideas that can be used by other scientists in the development of a drug to treat SARS-CoV-2.

Limitations

The study outcomes rely on predictive simulations alone, which indicates hypotheses that need continuation studies to test the hypotheses generated in this research. Computational method validation does not guarantee experimental method validation since both domains are scientifically different; one is virtual, and the other one is real. It may create some false positive outcomes in some cases due to several factors that are not aligned in experimental and computational methods used in new drug discovery and development.

Ethics Statement

The authors have read and follow the ethical requirements for publication in Data in Brief and confirming that the current work does not involve human subjects, animal experiments, or any data collected from social media platforms.

CRediT Author Statement

Vasudeva Rao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software Mariyam Eema: Validity tests, Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation. Vasudeva Rao, Mariyam Eema: Visualization, Investigation. Vasudeva Rao: Supervision. Mariyam Eema: Software, Validation.: Vasudeva Rao, Mariyam Eema: Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

All authors are thankful to the IMU University Vice Chancellor, DVCs and Pro-VCs, Director and Deputy Directors of IRDI, Dean and Associate Deans, School of Postgraduate Studies for providing the facilities to complete our final year research project for the fulfilment of the award of MSc in Molecular Medicine program at IMU University (Formerly known as International Medical University). This research was funded by IMU Joint-Committee on Research & Ethics, Project ID No MMM 1-2022(05).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability

References

- 1.Ng T.I., Correia I., Seagal J., DeGoey D.A., Schrimpf M.R., Hardee D.J., et al. Antiviral drug discovery for the treatment of COVID-19 infections. Viruses. 2022;14(5):961. doi: 10.3390/v14050961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vangeel L., Chiu W., De Jonghe S., Maes P., Slechten B., Raymenants J., et al. Remdesivir, molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir remain active against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and other variants of concern. Antiviral Res. 2022;198 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2022.105252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luttens A., Gullberg H., Abdurakhmanov E., Vo D.D., Akaberi D., Talibov V.O., et al. Ultralarge virtual screening identifies SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors with broad-spectrum activity against coronaviruses. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144(7):2905–2920. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c08402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rameshkumar M.R., Indu P., Arunagirinathan N., Venkatadri B., El-Serehy H.A., Ahmad A. Computational selection of flavonoid compounds as inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 main protease, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and spike proteins: a molecular docking study. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021;28(1):448–458. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh R., Chakraborty A., Biswas A., Chowdhuri S. Evaluation of green tea polyphenols as novel corona virus (SARS CoV-2) main protease (Mpro) inhibitors – an in silico docking and molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021;39(12):4362–4374. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1779818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tallei T.E., Tumilaar S.G., Niode N.J., Fatimawali Kepel BJ, Idroes R., et al. Potential of plant bioactive compounds as SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) and spike (S) glycoprotein inhibitors: a molecular docking study. Scientifica (Cairo) 2020;2020:1–18. doi: 10.1155/2020/6307457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Won Bang J., Dat Nguyen M., Kim Y., Mohamed Tap F., Bahiyah Ahmad Khairudin N., et al. Analysis of flavonoid compounds of Orange (Citrus sp.) peel as anti-main protease of SARS-CoV-2: a molecular docking study. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022;951(1) [cited 2022 Oct 14] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadni H., Fitri A., Benjelloun A.T., Benzakour M., Mcharfi M. Evaluation of flavonoids as potential inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease and spike RBD: molecular docking, ADMET evaluation and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2022;99(10) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das P., Majumder R., Mandal M., Basak P. In-Silico approach for identification of effective and stable inhibitors for COVID-19 main protease (M pro) from flavonoid based phytochemical constituents of Calendula officinalis. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021;39(16):6265–6280. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1796799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teli D.M., Shah M.B., Chhabria M.T. In silico screening of natural compounds as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease and spike RBD: targets for COVID-19. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021;7:1–25. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.599079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arora S., Lohiya G., Moharir K., Shah S., Yende S. Identification of potential flavonoid inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease 6YNQ : a molecular docking study. Digit. Chin. Med. 2020;3(4):239–248. [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Monica G., Bono A., Lauria A., Martorana A. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease for treatment of COVID-19: covalent inhibitors structure–activity relationship insights and evolution perspectives. J. Med. Chem. 2022;65(19):12500–12534. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.