Abstract

Background

Cardiac Amyloidosis (CA) remains highly underdiagnosed, especially among patients with causes of increased ventricular wall thickness, such as aortic stenosis (AS). The prevalence of CA throughout the spectrum of mild to severe AS is unknown and specific validated diagnostic parameters for this population are lacking. Here, we propose and prospectively evaluate a screening algorithm for CA among patients with mild to severe AS.

Methods

In this prospective, single-center study (NCT05010980), we included patients ≥ 65 years with mild to severe AS, an interventricular septum thickness > 11 mm, and at least one of the following criteria: Sokolow-Lyon-Index to left ventricular mass index ratio < 1.6 or stroke volume index < 35 ml/m2. Participants were prospectively screened for CA according to current guideline recommendations.

Results

After screening 2126 patients of whom 187 were eligible, 57 participants were enrolled and completed the diagnostic work-up. Mean age was 83 ± 0.7 years and 71% were male. 30% of the participants had mild, 37% had moderate and 33% had severe AS, respectively. Overall 26% of participants were diagnosed with CA. The prevalence of CA was higher among patients with mild AS (41%) compared to participants with moderate (24%) or severe AS (16%, p = 0.01). Within this preselected patient population, troponin (AUC:0.9, p < 0.0001) and NT-proBNP (AUC:0.86, p < 0.0001) further improved discrimination of patients with and without CA.

Conclusion

The prevalence of CA among AS patients fulfilling the preselected inclusion criteria was high, especially among those with mild to moderate AS. Implementing these criteria in clinical protocols could improve early diagnosis of CA.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Cardiac amyloidosis, Aortic stenosis, Screening algorithm

Introduction

Cardiac amyloidosis (CA) is a leading cause of heart failure and is associated with poor long-term survival. Although distinct therapies, especially for the treatment of transthyretin CA (ATTR), have been introduced during the last decades [1–3]residual risk is high, particularly due to often-delayed diagnosis of CA. In clinical practice, the diagnosis of both, ATTR- and light chain (AL) CA, is often challenging, especially among patients with alternative explanations for left ventricular hypertrophy. Accordingly, Nitsche et al. found CA highly underdiagnosed among patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) and reported a CA prevalence of up to 8% within this cohort [4]. Although in their retrospective analyses parameters as low stroke-volume index (SVI) and reduced ratio of Sokolow-Lyon-index (SLI) to left ventricular mass index (LVMI) were reported to support screening for CA [4]there is no screening algorithm for CA established in clinical practice. Additionally, the prevalence and development of CA among patients with mild to moderate CA is unknown, although recent findings of amyloid depositions within the aortic valve suggest a direct association between CA and AS progression [5].

To understand the course of AS among patients with CA and to establish early diagnosis among these vulnerable patients it is of utmost importance to establish a clinically applicable screening algorithm for all patients with AS at risk for CA.

Aims

Here, we aimed to prospectively evaluate the real-world feasibility of a diagnostic screening algorithm for CA within the complete spectrum of mild to severe AS.

Methods

Study design and ethical approval

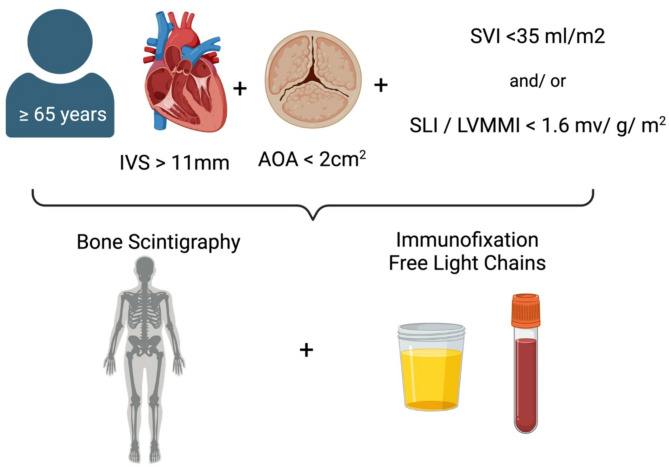

Patients were screened prospectively when scheduled for echocardiography between 2021 and 2023 at the University Hospital Duesseldorf and included if they signed informed written consent, were at least 65 years of age, had an interventricular septum (IVS) diameter > 11 mm, were diagnosed with mild to severe AS, defined as aortic valve orifice area calculated by velocity time integral < 2cm2 (severe AS: <1cm2, moderate AS: 1–1,5cm [2] and mild AS: 1,5-2cm [2]) and fulfilled at least one of the following criteria, which were previously reported with high specificity to detect CA among patients with severe AS [4] (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1.

Inclusion criteria and screening algorithm. Patients ≥ 65 years with an IVS > 11 mm, AOA < 2cm2 and one additional criterium either SVI < 35 ml/m2 and/or SLI/LVMI < 1.6 mV/g/m2 were scheduled for bone-scintigraphy, immunofixation in serum and urine and serum free light chain assays. IVS: interventricular septum, AOA: aortic valve orifice area, SVI: stroke volume index, SLI: Sokolow-Lyon index, LVMI: leftventricular myocardial mass index; created in biorender.com

Sokolow-Lyon-Index (SLI) to left ventricular mass index (LVMI) ratio as calculated by echocardiography < 1.6 mv/g/m2.

Stroke-Volume-Index (SVI) < 35 ml/m2 as calculated by echocardiography using the continuity equation across the left ventricular outflow tract.

In cases of suspected severe or marginal moderate to severe low-flow low-gradient AS calcium scoring by cardiac computer tomography (CT) has been used to distinguish between severe and pseudo severe AS as described previously [6, 7]. In cases of on-going uncertainty low-dose dobutamine stress echocardiography would have been performed, which was not necessary among this cohort.

The study has been approved by ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of the Heinrich-Heine-University in Duesseldorf (reference number: 2021 − 1427). All studies were carried out in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. The trial has been registered a priori (NCT05010980).

Diagnostic work up for CA

Diagnostic work up after fulfilling the above listed criteria was conducted as recommended by the 2021 ESC Guidelines [8] using a non-invasive approach based on bone-scintigraphy, serum free light-chains and immunofixation in serum and urine (Fig. 1). If necessary further diagnostics (magnetic resonance, right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy or consultation of the hematology service) were performed.

To further improve our diagnostic algorithm patients with and without CA were compared and ROC-analyses were performed with the parameters which differed between the groups.

Statistics

Normal distribution was tested by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and groups were compared using an unpaired students t-test. Categorical variables were compared using a chi-square test. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). In cases of non-normal distribution data are presented as median [25%; 75% percentile] and compared using a Mann-Whitney test. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analyses were performed using the Wilson/ Brown-Method. Statistical significance was assumed if p was < 0.05. All analyzes were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9 for macOS.

Results

Patient characteristics

After screening 2126 patients, 187 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Of these, 62 patients were included and 57 completed the diagnostic algorithm for CA (five patients were excluded because of an incomplete diagnostic work-up). Mean age was 83.2 ± 0.74 years and 72% were male, 46% of patients presented with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I or II and median NT-proBNP was 1344 pg/ml [ IQR: 656; 3808]. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome (5.3%), spinal canal stenosis (7%) and polyneuropathy (3.5%) were low among the investigated cohort. Further baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, echocardiographic and clinical parameters of included patients stratified by AS severity. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) or median [25;75 percentile] in cases of non-normal distribution, n = 57; p < 0.05 was considered statistical significant; BMI: body-mass-index, IVS: interventricular septum, LVMI: left ventricular mass index, SLI: sokolow-lyon-index, SVI: stroke volume index, LAVI: left-atrial volume index, TAPSE: tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, pasys: systolic pulmonary artery pressure, LVEF: leftventricular ejection fraction, LVEDD: left ventricular enddiastolic diameter, AOA: aortic valve orifice area, hs: high sensitive, GFR: glomerular filtration rate, AVB: atrioventricular block, BBB: bundle branch block, ACE: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ARNI: angiotensin-receptor-neprilycin inhibitor, SGLT2I: sodium-glucose-cotransporter 2 inhibitor

Diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis

According to the 2021 ESC Guidelines most patients (87%) were diagnosed with CA non-invasively. Endomyocardial biopsy was performed in four patients (7%) and in two of those CA has been confirmed. Eleven patients (19%) were consulted by the hematology service of whom three (27%) were diagnosed with AL CA and four were diagnosed with ATTR CA (36%). In four patients (36%) CA has been excluded.

All patients with diagnosed ATTR CA were offered genetic testing, five patients (42%) were finally tested, and all were diagnosed with wild-type ATTR (wtATTR).

Perugini-scores, as reported after bone-scintigraphy, were 2 in six patients and 3 in another six patients with ATTR CA, among patients with AL CA one had a Perugini-score of 2 the others were rated as Perugini-score 0. CA was excluded in two patients with Perugini-score 1.

Cardiac amyloidosis in dependence of aortic stenosis

Mild AS was present in 17, moderate AS in 21 and severe AS in 19 patients. Overall, 15 patients (26%) were diagnosed with CA (ATTR: 12, AL: 3, Fig. 2A). In patients with mild AS, 41% were diagnosed with CA; whereas in those with moderate AS, 24%, and among those with severe AS, 16% had CA (Fig. 2B). Logistic regression revealed a higher probability of CA in patients with greater aortic valve orifice area (AOA) (G2 = 6.24, p = 0.01, AUC: 0.7, p = 0.02), whereas within the other screening parameters only IVS hypertrophy (G2 = 5.1; p = 0.02; AUC: 0.67, p = 0.04) revealed a higher probability of CA diagnosis above the determined threshold for inclusion (Age: G2 = 3.47; p = 0.06; AUC: 0.68, p = 0.04; SVI: G2 = 0.001; p = 0.97; AUC: 0.51, p = 0.9; SLI/LVMI: G2 = < 0.001; p = 0.99; AUC: 0.55, p = 0.99).

Fig. 2.

Frequency of Cardiac Amyloidosis using the predefined screening algorithm. A: Frequency of ATTR and AL CA among included patients and B: Prevalence of CA was associated with severity of aortic stenosis (G2 = 6.24, p = 0.01, AUC: 0.7, p = 0.02 by logistic regression). ATTR: transthyretin amyloidosis, AL: light-chain amyloidosis, CA: cardiac amyloidosis, AUC: area under the curve

Median IVS was 14 mm and did not differ according to AS severity, nor did SVI, SLI/ LVMM or left atrial volume index (Table 1).

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was within the normal range among all groups but was the lowest among patients with mild AS (Table 1). NT-proBNP and hs Troponin T at baseline were highest in patients with mild AS. Groups did not differ according to baseline heart failure medications or diuretic dose (Table 1).

Patient characteristics with and without cardiac amyloidosis

Patients with CA were more likely to suffer from NYHA classes III or IV and had higher values of NT-proBNP and hs troponin T (Table 2). Additionally, CA patients had a bigger IVS, a lower LVEF and a lower TAPSE (Table 2). Atrioventricular blockade of any grade was more common among patients with CA. Further details are listed in Table 2. Within this preselected patient population, hs troponin (AUC: 0.9, p < 0.0001) and NT-proBNP (AUC: 0.86, p < 0.0001) further improved discrimination of patients with and without CA, as indicated by ROC-analyses. A cut-off for hs Troponin T of > 40.5 ng/l reached a sensitivity of 91.7% and a specificity of 80.6%, using a NT-proBNP cut-off of 1516 ng/l a sensitivity of 93.3% and a specificity of 70.7% was reached.

Table 2.

Demographic, echocardiographic and clinical parameters of included patients stratified by the diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) or median [25;75 percentile] in cases of non-normal distribution, n = 57; p < 0.05 was considered statistical significant; BMI: body-mass-index, IVS: interventricular septum, LVMI: left ventricular mass index, SLI: sokolow-lyon-index, SVI: stroke volume index, LAVI: left-atrial volume index, TAPSE: tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, pasys: systolic pulmonary artery pressure, LVEF: leftventricular ejection fraction, LVEDD: left ventricular enddiastolic diameter, AOA: aortic valve orifice area, hs: high sensitive, GFR: glomerular filtration rate, AVB: atrioventricular block, BBB: bundle branch block, ACE: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ARNI: angiotensin-receptor-neprilycin inhibitor, SGLT2I: sodium-glucose-cotransporter 2 inhibitor

Discussion

The screening algorithm evaluated here resulted in a diagnosis of CA in more than every fourth patient. Application of the here-proposed algorithm is the first used for patients with mild to severe AS and solely requires routinely performed echocardiography and ECG, which distinguishes it from alternative scores. The RAISE-score for example, was tested in patients scheduled for TAVR only and comprises echocardiography, biomarkers, systemic involvement, and electrocardiographic changes, making it more complex in clinical practice [9].

In line with their findings our data suggest the addition of Troponin T and NT-proBNP to improve diagnostic accuracy also in patients with mild to moderate AS.

Importantly, although the underlying pathomechanisms differ substantially [10]not only ATTR but also AL CA, has been detected with this algorithm in a few cases.

The higher prevalence of CA in mild to moderate AS in this study is possibly linked to the screening algorithm. More specifically, participants with severe AS were more likely to fulfill the screening criteria (increased septal wall thickness and reduced SVI) due to the AS alone as compared to those with low to moderate AS, in whom only the combined hit of CA and AS led to these structural alterations. In addition, LVEF was lower, whereas NT-proBNP and Troponin T were higher in patients with mild AS. These findings may be explained by a relatively high proportion of patients with AL-CA, which is known for its cardiotoxicity [10]or a relatively high myocardial amyloid burden compared to patients with moderate or severe AS. This may have led to the patient’s clinical presentation and therefore to a selection bias in our cohort, but these considerations remain speculative. Still, our results suggest that clinicians should not only focus on patients with severe AS but consider CA across the whole spectrum of AS.

The interplay between AS progression and CA is not completely understood. Recent studies suggest both an accelerated AS progression caused by amyloid deposits within the valve causing increased pressure overload and an increased probability of amyloid deposition in valves of AS patients [5, 11, 12]. This is sought to be caused by increased sheer stress, consecutive endothelial dysfunction, and lipid infiltration, which most likely explain immuno-histological evidence of amyloid within 44% of explanted valves after aortic valve replacement [5, 11, 12].

The prevalence of CA among AS patients has been reported from 4 to 16% in different cohorts. Differences within the reported prevalence are most likely caused by varying diagnostic modalities (e.g. CMR [13] in comparison to EMB or bone-scintigraphy [4, 14, 15]), investigated populations (older populations after TAVR [4, 14] compared to SAVR [15]) and distinct inclusion criteria increasing the probability of CA [16, 17]. In our cohort the prevalence of CA seems to be substantially higher as in the overall AS population which is consistent with the previous studies since our cohort has been preselected using parameters expected to increase the probability to detect CA [4].

Limitations of our study are the small sample size and its single center character which forbid generalizability and may have led to an overestimation of CA prevalence, especially regarding to the AS subgroups, since patients undergoing echocardiography in an university hospital may have led to a selection bias. Additionally, echocardiographic AOA measurement as the main parameter for AS grading, bears a potential for misinterpretation in some cases, but is a simple screening estimate of AS grading on the other hand. Nevertheless, our results concerning patients with severe AS go in line with previous reports.

Conclusion

The prevalence of CA among AS patients fulfilling the preselected inclusion criteria was high, especially among those with mild to moderate AS. Further studies are needed before implementing these criteria into clinical protocols which afterwards could improve early diagnosis of CA in AS patients.

Acknowledgements

Figure 1 and the graphical abstract was created with biorender.com, Figure 2 was created with GraphPad Prism 9.

Abbreviations

- CA

Cardiac amyloidosis

- ATTR

Transthyretin

- AL

Light chain

- AS

Aortic stenosis

- TAVR

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement

- SLI

Sokolow-Lyon index

- LVMI

Left ventricular mass index

- SVI

Stroke-volume index

- IVS

Interventricular septum

- vATTR

Variant-type transthyretin

- wtATTR

Wild-type thransthyretin

- AOA

Aortic valve orifice area

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

Author contributions

FV: Data curation; Validation; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Conceptualization; Writing – original draft. EZ, JMH, JH, CM, KK, SA: Data curation, Validation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. RF, RP, MS: Conceptualization; Validation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. CJ, TZ, RW: Supervision; Writing – review & editing; Visualization MK: Supervision; Conceptualization; Writing – review & editing. AP, DS: Formal Analysis, Conceptualization; Project administration; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding

None.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of the Heinrich-Heine-University in Duesseldorf (reference number: 2021 − 1427). All studies were carried out in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Amin Polzin and Daniel Scheiber have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Maurer MS, Schwartz JH, Gundapaneni B, Elliott PM, Merlini G, Waddington-Cruz M, et al. Tafamidis treatment for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1007–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontana M, Berk JL, Gillmore JD, Witteles RM, Grogan M, Drachman B et al. Vutrisiran in patients with transthyretin amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2024.2025;392:33-44 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Nies RJ, Ney S, Kindermann I, Bewarder Y, Zimmer A, Knebel F, et al. Real-world characteristics and treatment of cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis: A multicentre, observational study. ESC Heart Fail; 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Nitsche C, Aschauer S, Kammerlander AA, Schneider M, Poschner T, Duca F et al. Light-chain and transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis in severe aortic stenosis: prevalence, screening possibilities, and outcome. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(10):1852-1862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Honda K, Tasaki M, Yamano T, Ueda M, Naiki H, Tanaka N et al. High frequency of occult transthyretin and Apolipoprotein AI-type amyloid in aortic valves removed by valve replacement for aortic stenosis. Amyloid. 2025;32(1):22-28 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Clavel MA, Burwash IG, Pibarot P. Cardiac imaging for assessing Low-Gradient severe aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:185–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clavel MA, Magne J, Pibarot P. Low-gradient aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2645–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Authors/Task Force M, McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European society of cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24:4–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nitsche C, Scully PR, Patel KP, Kammerlander AA, Koschutnik M, Dona C, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of concomitant aortic stenosis and cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:128–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voss F, Zweck E, Ipek R, Schultheiss HP, Roden M, Kelm M, et al. Myocardial mitochondrial function is impaired in cardiac Light-Chain amyloidosis compared to transthyretin amyloidosis. JACC Heart Fail; 2024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Jaiswal V, Agrawal V, Khulbe Y, Hanif M, Huang H, Hameed M, et al. Cardiac amyloidosis and aortic stenosis: a state-of-the-art review. Eur Heart J Open. 2023;3:oead106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kristen AV, Schnabel PA, Winter B, Helmke BM, Longerich T, Hardt S, et al. High prevalence of amyloid in 150 surgically removed heart valves–a comparison of histological and clinical data reveals a correlation to Atheroinflammatory conditions. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2010;19:228–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavalcante JL, Rijal S, Abdelkarim I, Althouse AD, Sharbaugh MS, Fridman Y, et al. Cardiac amyloidosis is prevalent in older patients with aortic stenosis and carries worse prognosis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017;19:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castano A, Narotsky DL, Hamid N, Khalique OK, Morgenstern R, DeLuca A, et al. Unveiling transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis and its predictors among elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2879–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treibel TA, Fontana M, Gilbertson JA, Castelletti S, White SK, Scully PR et al. Occult transthyretin cardiac amyloid in severe calcific aortic stenosis: prevalence and prognosis in patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Longhi S, Lorenzini M, Gagliardi C, Milandri A, Marzocchi A, Marrozzini C, et al. Coexistence of degenerative aortic stenosis and Wild-Type Transthyretin-Related cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:325–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balciunaite G, Rimkus A, Zurauskas E, Zaremba T, Palionis D, Valeviciene N, et al. Transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis in aortic stenosis: prevalence, diagnostic challenges, and clinical implications. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2020;61:92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.