Abstract

Background

Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPSs) are common in people with dementia (PWD), but their associations with the risk of institutionalization and mortality are controversial. The objective of this study was to estimate the incidence of institutionalization and death among PWD treated in primary care (PC) and to analyse the associations between NPSs and these events.

Methods

This was a longitudinal analytical observational study of PWD in PC with a 4-year follow-up. Data on sociodemographic, clinical and functional characteristics and prescribed treatments for dementia were collected. NPSs were examined with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) scale and according to the presence of clinically relevant neuropsychiatric subsyndromes. The incidence of institutionalization and cumulative mortality were calculated annually and at four years. Survival analysis with Kaplan‒Meier curves and Cox regression was performed to analyse the influence of NPSs on institutionalization and mortality.

Results

A total of 124 patients with a mean age of 82.5 (8.0) years were included, and 69.4% were women. At four years, the institutionalization rate in a nursing home was 29.8% (95% CI 22.0; 38.7), with a median time to institutionalization of 13.2 months (IQR: 6.8–31.5). The mortality rate was 48.4% (95% CI 39.3; 57.5), with a median survival time of 21.7 months (IQR: 14.2–32.0). The NPI score was associated with institutionalization (HR 1.27, 95% CI 1.12, 1.45) and mortality (HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.40, 1.54). Among the subsyndromes, the presence of clinically relevant apathy was associated with institutionalization (HR 2.23, 95% CI 1.29, 3.88) and mortality (HR 1.56, 95% CI 1.34, 1.81).

Conclusions

In PWD who were followed up in the community for four years, one-third of the patients were institutionalized, and half died. The intensity of the NPSs influences both institutionalization and mortality, with subsyndrome apathy (formed by the symptoms of apathy and appetite alterations) being the one that most influences both outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-025-06339-0.

Keywords: Dementia, Incidence, Mortality, Institutionalization, Neuropsychiatric symptoms, Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, Apathy, Neuropsychiatric Inventory, Primary care

Background

Dementia is a major global health challenge, with a prevalence among people over 65 years old ranging from 7.1% to 16%, according to studies from Europe and the USA [1–3]. The physical and mental deterioration caused by dementia not only impacts the quality of life of those affected, but also has significant consequences for their families, caregivers and society as a whole, resulting in a substantial economic burden [4, 5].

One of the most difficult problems to address in people with dementia (PWD) is the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia or neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPSs). These manifestations frequently appear (50–98%) at any stage of the disease [6–11], and their presence worsens the disease prognosis, increasing the risk of progression to severe dementia [12, 13], institutionalization [14–23] and mortality [12, 15, 24–26]. NPSs can be evaluated with different scales, among which one of the most commonly used is the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) [27]. For its study and management, its grouping into neuropsychiatric subsyndromes can also be considered [28].

The NPSs that have been most frequently associated with an increased risk of mortality are depression, anxiety, delusions, hallucinations, apathy, irritability, and agitation/aggressiveness [12, 15, 24–26, 29]. Mortality is also associated with a higher value on the NPI scale [24, 26], and the presence of at least one clinically relevant NPS (NPI scale value ≥ 4) [12, 24, 30].

On the other hand, the NPSs that have been most strongly associated with institutionalization are agitation/aggressiveness, disinhibition, delusions and hallucinations [17, 19, 20, 31–33]. The total NPI score [21, 22], the presence of at least one NPS [16, 18], a higher number of symptoms [20] or highly symptomatic status [15] have also been described as predictors of institutionalization. However, there are other studies in which this association between the presence of NPSs and mortality [33, 34] or institutionalization [34, 35] has not been reported, considering that caregiver overload is a predictor of both death [34] and patient admission to a residence [34, 35].

Therefore, there is no uniformity in the results of studies on the impact of NPSs on institutionalization and mortality, which justifies continuing research in this field.

The objective of this study was to estimate the incidence of institutionalization and death among PWD treated in primary care (PC) and to analyse the associations between NPSs and these events.

Methods

Study design, setting and participants

This was a longitudinal analytical observational cohort study with a 4-year prospective follow-up in two health centres in the urban municipalities of Alcorcón and Villaviciosa de Odón (Madrid Region-Spain), which serve a population of 43,594 inhabitants, of which 9,247 are ≥ 65 years old. This article was prepared according to the STROBE recommendations [36].

Patients who were diagnosed with dementia, identified in the electronic medical records (EHR) of the Community of Madrid with the code P70 according to the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) and/or were receiving specific treatment (anticholinesterase and/or memantine) who had at least one consultation or received some care in a PC setting in 2015 and who had a known caregiver who agreed to participate in the study were included if they signed the informed consent form. Institutionalized or deceased patients were excluded on the start date of the study. Additionally, those with previous major mental disorders such as schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders and caregivers who did not understand the Spanish language were excluded. The follow-up period was from November 18, 2015, to November 17, 2019.

A total of 356 PWD were identified, 176 of whom met the inclusion criteria, with 129 agreeing to participate in the study. With this sample size and an expected annual mortality rate of 6% [37, 38], the precision of our result would be 4.1%, and for an expected proportion of annual institutionalization of 16% [32, 35, 37, 38], the precision would be 6.3%.

Variables

Baseline data

Baseline sociodemographic, clinical, and functional data were collected by reviewing the patient's EHR and by interviewing the main caregiver, which included standardized questionnaires. Patient variables included age, sex and educational level; functional assessment via the Barthel Index for Activities of Daily Living [39] with the dependency levels established by Shah et al. [40] (independent:100 points; slight dependency: 91–99 points, moderate dependency: 61–90 points, severe dependency: 21–60 points, total dependency: < 21 points); the developmental phase of dementia according to Reisberg's Global Deterioration Scale (GDS), where GDS 3 is mild cognitive decline and GDS 7 is very severe cognitive decline [41]; specific treatment for dementia (anticholinesterase and/or memantine); treatment for NPSs with neuroleptics and comorbidities according to the Charlson index [42]. This index includes 19 well-defined clinical situations to which a score of 1, 2, 3 or 6 points is assigned (a maximum of 33 points); it is one of the most commonly used validated indices to evaluate comorbidities [43]; has good test–retest reliability; has adequate inter- and intraobserver validity; and is significantly correlated with mortality, disability, readmission, and mean stay [44]. For this work, the index was categorized into ≤ 2 points and > 2 points to differentiate patients with no or low comorbidity (0–2 points) from those with high comorbidity (> 2 points) [45].

Data on the NPSs were collected via the validated version for the Spanish population of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), whose total score (0–144) is calculated via the product of frequency by severity (intensity) of twelve symptoms [27, 46]. To group the NPSs, the classification of Aalten et al. 2007 was used, which consists of four subsyndromes [47]: “hyperactivity” subsyndrome (agitation/aggression, disinhibition, irritability/lability, aberrant motor behaviour and elation/euphoria); “psychosis” subsyndrome (delusions, hallucinations, sleep behaviour); “affective” subsyndrome (depression, anxiety); and “apathy” subsyndrome (apathy/indifference and appetite/eating behaviour). For this study, clinically significant or clinically relevant subsyndromes were considered when at least one NPS of the subsyndrome had a value on the NPI scale ≥ 4 [48, 49]. Although the expressions"clinically significant"[6, 50–52] and"clinically relevant"[47, 53, 54] are used interchangeably in the literature, in our study, we use the term “clinically relevant”.

Finally, data on variables related to the caregiver, namely, employment status and caregiver overload, were collected by means of the short Zarit test for dementia [55], which is a shortened form of the Spanish validation of the Zarit test [56, 57]. This test explores 4 items related to self-care, irritability and overload, with scores ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always) for each item. The minimum score is 4 points, the maximum score is 20 points, and a score ≥ 10 is considered overload.

Follow-up data

The measures of institutionalization and death outcomes were measured at 1, 2, 3 and 4 years. The data were obtained from electronic clinical records and administrative registers. Institutionalization was defined as permanent admission to a nursing home. The date of death or institutionalization was then regarded as the end of the observation period. Death and institutionalization during the follow-up period were considered "events". The institutionalization outcome was measured from the start of inclusion in the cohort until admission to a nursing home. For the event of death, all patients were followed from their inclusion in the cohort until their death, regardless of whether or not they had been admitted to a nursing home. The events 'death', 'other dropout' or 'end of study' were censored, and the observation period was measured as days from baseline to the occurrence of the target or censoring event.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive statistics, means, medians or proportions were used. Chi-squared tests and Student’s t tests were used for comparisons of the baseline characteristics of the patients who were lost to follow-up versus those of patients who completed the follow-up. The cumulative annual and 4-year incidence rates of institutionalization and death were calculated. The mean and median times to death or institutionalization were calculated.

A survival analysis was conducted. Kaplan‒Meier survival curves were generated according to NPSs intensity and according to the presence (or absence) of neuropsychiatric subsyndromes. Log-rank tests were used to test for differences between curves. Cox regression was used to calculate univariate and adjusted multivariate hazard ratios (HRs) to determine the influence of NPSs on the institutionalization and death of patients with dementia. For each event (mortality or institutionalization), two multivariate models (Cox regression) were constructed, one using the NPI value categorized using the median as the cut-off point [26, 35], and the other considering the presence of clinically relevant subsyndromes. The models were adjusted for the remaining variables collected.

The proportional hazards assumption was checked via graphical methods [58] and by studying the Schoenfeld residuals [59]. The selection of the best model was performed by assessing its alignment with the theoretical framework and the goodness of fit measured through the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) [60]. Since the data originated from two different centres, standard errors were calculated by means of robust methods [61].

SPSS 26.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and STATA 15 were used for the statistical analysis.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Alcorcón Foundation University Hospital on 23 September 2015 (for the initial analysis) and 02 July 2019 (for the follow-up study).

Results

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the 129 patients who were initially included in the study, the epidemiological characteristics of the caregivers, and the data related to care-related burden have been previously described [11, 62]. Five of the 129 patients did not have data on mortality or institutionalization at four years. The participants included in the analyses did not differ significantly from those excluded (Supplement 1).

The 124 patients included had a mean age of 82.5 (SD 8.0) years, and 69.4% were women.

During the 4-year follow-up period, 37 patients were institutionalized (29.8%, 95% CI 22.0; 38.7): 12.1% in the first year, 5.9% in the second year, 9.9% in the third year, and 13.6% in the fourth year. Sixty of the 124 patients died (48.4%, 95% CI 39.3; 57.5): 8.9% in the first year, 16.8% in the second year, 20.2% in the third year, and 14.7% in the fourth year. The percentage of deaths among institutionalized patients was 45.9% (95% CI 29.5; 63.1), and among noninstitutionalized patients, it was 49.4% (95% CI 38.5; 60.4).

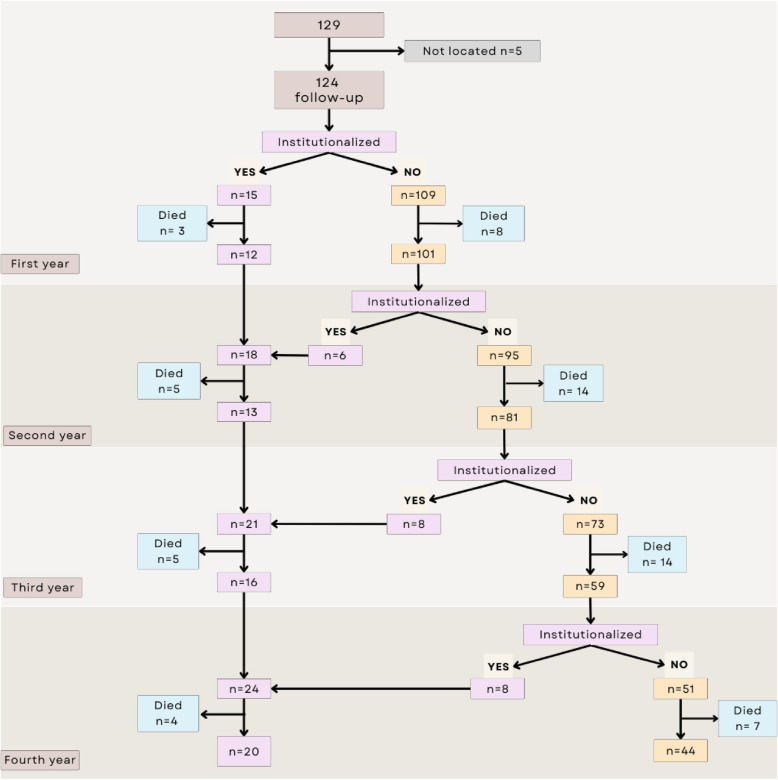

The median follow-up was 45.1 months (IQR: 22.3–47.0), with a mean time of 35.1 (SD 14.3) months. The flow chart of the follow-up of the patients is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Patient follow-up flow chart (flow chart)

Institutionalization

In the 37 institutionalized patients, the median from their inclusion in the study to their admission to residence was 13.2 months (IQR: 6.8–31.5) [mean 19.4 (14.4) months]. The Kaplan‒Meier curve for institutionalization is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Survival curve for institutionalization

The survival curves for institutionalization according to the total NPI value, with the median used as the cut-off point (21 points), and the presence of neuropsychiatric subsyndromes, is shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

Fig. 3.

Survival curve for institutionalization according to the total NPI score

Fig. 4.

Survival curve for institutionalization according to the presence of clinically relevant neuropsychiatric subsyndromes

Supplement 2 shows the institutionalization survival curves according to other factors related to the patient or caregiver.

In the univariate analysis, institutionalization was associated with a total NPI score > 21 points (HR 1.23, 95% CI 1.16; 1.32) and the presence of clinically relevant apathy subsyndrome (HR 2.26, 95% CI 1.31; 3.91). Other associated variables were being male (HR 1.33, 95% CI 1.02; 1.73), having a lower educational level (HR 1.52, 95% CI 1.26, 1.84) and being in treatment for dementia (HR 1.36, 95% CI 1.00; 1.84) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Factors associated with institutionalization (univariate and multivariate Cox regression models)

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1(1) | Model 2(2) | ||||||||

| HR | (95% CI) | p | HR | (95% CI) | p | HR | (95% CI) | p | |

| Patient age (< 80 years) | 1.11 | (0.27; 4.54) | 0.882 | ||||||

| Patient sex (female) | 1.33 | (1.02; 1.73) | 0.031 | 1.45 | (1.05; 2.00) | 0.025 | 1.41 | (1.00; 2.00) | 0.052 |

| Patient studies (≥ secondary) | 1.52 | (1.26; 1.84) | 0.000 | 1.33 | (1.21; 1.47) | 0.000 | 1.60 | (1.58; 1.61) | 0.000 |

| Barthel index (independence, little or moderate dependence, > 60 points) | 1.07 | (0.74; 1.55) | 0.715 | ||||||

| GDS stage (GDS 3–5 mild-moderate dementia) | 0.85 | (0.35; 2.07) | 0.719 | ||||||

| Treatment for dementia (No) | 1.36 | (1.00; 1.84) | 0.049 | 1.43 | (1.10; 1.87) | 0.009 | |||

| Neuroleptic treatment (No) | 1.17 | (0.91; 1.50) | 0.232 | ||||||

| Charlson index (≤ 2 points) | 0.97 | (0.71; 1.33) | 0.852 | ||||||

| Caregiver's employment status (Does not work) | 1.28 | (0.38; 4.28) | 0.688 | ||||||

| Presence of caregiver overload (No) | 1.38 | (0.72; 2.65) | 0.336 | ||||||

| Apathy subsyndrome (No)(1) | 2.26 | (1.31; 3.91) | 0.004 | 2.23 | (1.29; 3.88) | 0.004 | |||

| Hyperactivity subsyndrome (No)(1) | 1.51 | (0.68; 3.40) | 0.314 | ||||||

| Affective subsyndrome (No)(1) | 0.66 | (0.27; 1.60) | 0.356 | ||||||

| Psychosis subsyndrome (No)(1) | 0.86 | (0.47; 1.60) | 0.640 | ||||||

| NPI Scale (≤ 21 points) | 1.23 | (1.16; 1.32) | 0.000 | 1.25 | (1.05; 1.49) | 0.012 | |||

In bold: p statistically significant. GDS Global Deterioration Scale (GDS 3: mild CD, borderline impairment. GDS 4: moderate CD, mild dementia. GDS 5: moderately severe CD, moderate dementia. GDS 6: severe CD, moderately severe dementia. GDS 7: very severe CD, severe dementia)

1Cox regression model adjusted for the presence of clinically relevant neuropsychiatric subsyndromes (that is, having at least some neuropsychiatric symptoms with an NPI value ≥ 4)

AIC: 321.19

BIC: 324.01

2Cox regression model adjusted for the NPI score

AIC: 325.64

BIC: 328.46

In the multivariate analysis, in Model 1, which analyses the NPSs through subsyndromes, institutionalization was associated with the presence of clinically relevant apathy subsyndrome (HR 2.23, 95% CI 1.29; 3.88) in addition to male sex (HR 1.45, 95% CI 1.05; 2.00) and to a lower educational level (HR 1.33, 95% CI 1.21; 1.47). In Model 2, when the NPSs were analysed through the NPI scale, institutionalization was associated with a total NPI score > 21 points (HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.05; 1.49), and in addition to sex and educational level, institutionalization was associated with treatment for dementia (HR 1.43, 95% CI 1.10; 1.87) (Table 1).

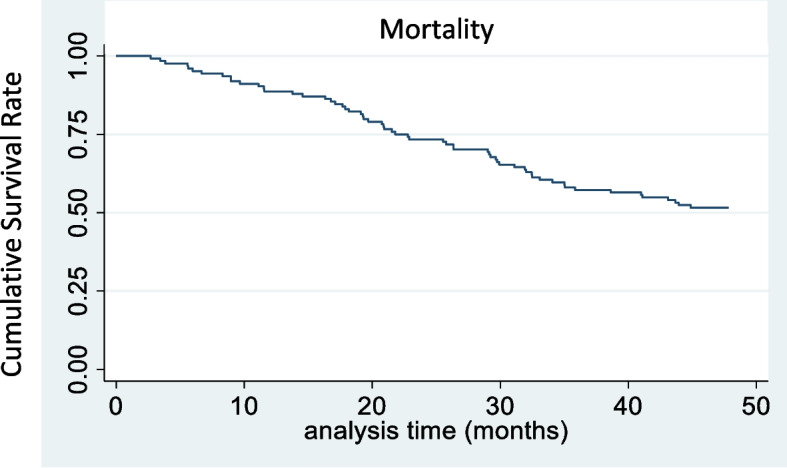

Mortality

The median time to death was 21.7 months (IQR: 14.2–32.0) [mean 22.9 (SD 11.6) months], 21.8 months for the institutionalized group and 21.5 months for the noninstitutionalized group [mean 24.2 (SD 12.3) and 22.4 (SD 11.4), respectively]. Figure 5 shows the Kaplan‒Meier curves for overall mortality.

Fig. 5.

Survival curves for overall mortality

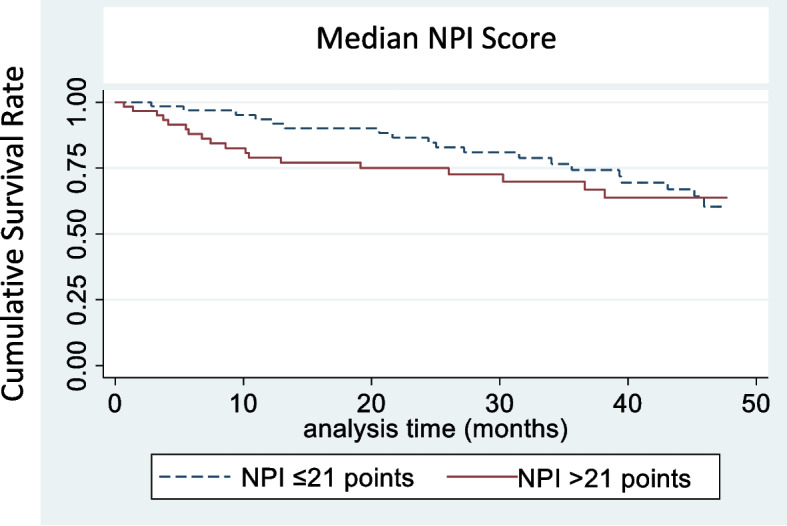

The curves for mortality according to the total NPI score, with the median used as the cut-off point (21 points), and the type of neuropsychiatric subsyndromes are shown in Figs. 6 and 7.

Fig. 6.

Survival curve for mortality according to the total NPI score

Fig. 7.

Survival curves for mortality according to the presence of clinically relevant neuropsychiatric subsyndromes

Survival and mortality curves according to other factors related to the patient are shown in Supplement 3.

In the univariate analysis, mortality was associated with a total NPI score > 21 points (HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.05; 2.26), apathy (HR 1.71, 95% CI 1.63; 1.80) and psychosis (HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.37; 2.06), which are clinically relevant. Other variables associated with mortality were older patient age (HR 2.25, 95% CI 1.59; 3.20), a higher level of dependence (HR 2.95, 95% CI 1.97; 4.41), greater severity of dementia (HR 2.97, 95% CI 1.18; 7.45), treatment with neuroleptics (HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.05; 1.28) and a higher Charlson index score (HR 1.62, 95% CI 1.39; 1.90) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with mortality (univariate and multivariate Cox regression models)

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1(1) | Model 2(2) | ||||||||

| HR | (95% CI) | p | HR | (95% CI) | p | HR | (95% CI) | p | |

| Patient age (< 80 years) | 2.25 | (1.59; 3.20) | 0.000 | 2.22 | (1.61; 3.06) | 0.000 | 2.08 | (1.62; 2.69) | 0.000 |

| Patient sex (female) | 1.18 | (0.76; 1.85) | 0.462 | ||||||

| Patient studies (≥ secondary) | 1.18 | (0.99; 1.40) | 0.072 | ||||||

| Barthel index (independence, little or moderate dependence, > 60 points) | 2.95 | (1.97; 4.41) | 0.000 | ||||||

| GDS stage (GDS 3–5 mild-moderate dementia) | 2.97 | (1.18; 7.45) | 0.020 | 3.40 | (1.45; 7.98) | 0.005 | 3.38 | (1.34; 8.52) | 0.010 |

| Treatment for dementia (No) | 0.63 | (0.38; 1.05) | 0.078 | ||||||

| Neuroleptic treatment (No) | 1.16 | (1.05; 1.28) | 0.003 | ||||||

| Charlson index (≤ 2 points) | 1.62 | (1.39; 1.90) | 0.000 | 1.67 | (1.29; 2.17) | 0.000 | 1.78 | (1.40; 2.26) | 0.000 |

| Apathy subsyndrome (No)(1) | 1.71 | (1.63; 1.80) | 0.000 | 1.66 | (1.47; 1.87) | 0.000 | |||

| Hyperactivity subsyndrome (No)(1) | 0.82 | (0.35; 1.89) | 0.638 | ||||||

| Affective subsyndrome (No)(1) | 1.30 | (0.96; 1.75) | 0.091 | ||||||

| Psychosis subsyndrome (No)(1) | 1.68 | (1.37; 2.06) | 0.000 | ||||||

| NPI Scale (≤ 21 points) | 1.54 | (1.05; 2.26) | 0.026 | 1.47 | (1.38; 1.58) | 0.000 | |||

In bold: p statistically significant. GDS Global Deterioration Scale (GDS 3: mild CD, borderline impairment. GDS 4: moderate CD, mild dementia. GDS 5: moderately severe CD, moderate dementia. GDS 6: severe CD, moderately severe dementia. GDS 7: very severe CD, severe dementia)

1Cox regression model adjusted for the presence of neuropsychiatric subsyndromes clinically relevant (that is, they have at least some neuropsychiatric symptoms with an NPI value ≥ 4)

AIC: 512.35

BIC: 515.17

2Cox regression model adjusted for total NPI score

AIC: 513.88

BIC: 516.70

In the multivariate analysis, in Model 1, which analyses the NPSs through subsyndromes, mortality was associated with the presence of clinically relevant apathy subsyndrome (HR 1.66, 95% CI 1.47; 1.87), older patient age (HR 2.22, 95% CI 1.61; 3.06), advanced stages of dementia (GDS 6–7) (HR 3.40, 95% CI 1.45; 7.98) and > 2 points according to the Charlson index (HR 1.67, 95% CI 1.29; 2.17). In Model 2, which analyses the NPSs through the NPI scale, mortality was associated with a total NPI score > 21 points (HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.38; 1.58), older patient age (HR 2.08, 95% CI 1.62; 2.69), higher GDS (greater severity) (HR 3.38, 95% CI 1.34; 8.52) and Charlson index > 2 points (HR 1.78, 95% CI 1.40; 2.26) (Table 2).

Discussion

In patients with dementia followed up in PC, the NPSs influence institutionalization and mortality, with subsyndrome apathy (formed by symptoms of apathy and appetite alterations) being the most associated with both.

In the four years of follow-up, one-third of the patients were institutionalized. The median duration from the start of the study until they entered a nursing home was 13 months. The annual incidence of institutionalization was 5.9 to 13.6 institutionalized per 100 person-years. Other studies carried out in specialized memory clinics in France and the Netherlands have reported a higher annual incidence of institutionalization, ranging from 11.8–23.5% [32, 35, 37, 38]. These differences may be related to sociocultural and economic factors that influence the decision to enter a family member in a residence, as well as the severity of dementia, since the published incidence is higher when the population has moderate–severe dementia [35] than when other studies include only mild–moderate dementia [37, 38].

Half of the patients died during the 4-year follow-up. The median duration from the start of the study to death was 22 months. The annual incidence of mortality that we found in our study was 8.9 to 20.2 deaths/100 person-years, which was higher than that reported in other studies, which reported incidences ranging from 5.9–7.4% [37, 38]. The higher mortality in our study can be attributed to the greater severity of dementia, since these studies included only patients with mild–moderate dementia and lowest average NPI score.

Factors associated with institutionalization

In our study, institutionalization was associated with the total NPI score and the presence of apathy subsyndrome when the symptoms are very intense. In other studies, highly symptomatic NPSs have also been described as predictors of patient institutionalization [15]. In addition, high values on the NPI scale or a greater number of symptoms in patients have been reported [15, 20–22]. The presence of apathy in PWD has also been associated with a higher risk of admission to a residence, regardless of the burden of the caregiver [63], and this is especially notable for patients with early-onset dementia [64] and those with Lewy body dementia [65]. On the other hand, altered appetite, which is part of the apathy subsyndrome, has been described as a predictor of institutionalization along with other NPSs, although in only a few studies [17].

However, we did not find a relationship between institutionalization and other NPSs or subsyndromes, in contrast to other studies in which an associations with agitation/aggressiveness [17, 19, 20] and disinhibition [17, 31], symptoms within the hyperactivity subsyndrome, and delusions and hallucinations, which are part of the psychosis subsyndrome [17, 19, 20, 33], and anxiety and depression (affective subsyndrome) were reported [19, 20].

On the other hand, we found that being male, having a lower level of education or being in treatment for dementia were associated with institutionalization. A systematic review on the predictors of admission to residences in older people revealed that the results for both male sex and a low level of education or low income were inconsistent, with the strongest predictors being age, dementia or functional impairment [66]. In a study carried out in Spain with people in a situation of dependency, the risk of institutionalization was three times higher among men than among women [67]. However, in studies carried out in PWD, there were no consistent results, since some studies have shown that the risk of institutionalization was greater among women [68, 69], whereas others showed this to be true among males [70, 71].

With respect to the educational level of the patients, other authors have reported more institutionalization of patients with a higher level of education [23, 31]. These differences from the work we present may be due to the sociocultural context. In our population, although we could not collect data on the socioeconomic level of the patients, we consider that the level of the studies can be interpreted as a"proxy"of the economic level. A lower educational level would imply having fewer economic resources, which would limit the possibility of hiring external help to maintain care at home and could force institutionalization when the level of dependency increases and more time of care is needed. In this sense, in our case, the low level of education of the patients was associated with caregiver overload in a previous work [62]. Managing behavioural symptoms can be difficult, and caregivers are sometimes unable to control the situation, which can lead to the institutionalization of patients [72]. The presence of caregiver overload has been described in multiple studies as a predictor of institutionalization [16, 18, 20, 23, 31, 34, 35, 73, 74]; however, we have not been able to demonstrate such an association.

In other studies, symptomatic treatments for NPSs, such as neuroleptics, have been shown to increase the risk of institutionalization [21], although in our case, we were not able to verify this association. In our study, we found that the specific treatment for dementia (anticholinesterase drugs and memantine) is related to admission to the nursing home. The findings in other studies are variable. One of them reported that patients who had received treatment before or within the year of diagnosis had a higher risk of admission to residences than did those without treatment; their interpretation was that patients without treatment were in earlier stages of the disease [69], which could explain the association between anticholinesterase or memantine treatment and admission. However, other authors reported either that patients who were undergoing treatment had a lower risk of institutionalization [75, 76] or that there was no association between the two [77].

Factors associated with mortality

Regarding the relationship between NPSs and mortality, the results revealed that a higher score on the NPI scale, which analyses the intensity of NPSs, is associated with mortality, which is consistent with the findings of other studies [24, 26]. Among the different NPSs, only the presence of apathy subsyndrome was associated with mortality in our study. Apathy has been described as a predictor of mortality, as well as an isolated symptom [24, 78, 79], as when it is part of the apathy subsyndrome (apathy and/or appetite disturbances) [15, 26]. Some authors suggest that this may be explained by the fact that apathy leads to a more serious clinical profile in Alzheimer's dementia patients, with worse functional progression and a higher risk of mortality [80]. A listless neurobehavioral profile also predicts death in patients with frontotemporal degeneration [81]. Apathy in dementia can aggravate the difficulty in controlling chronic diseases and lead to social isolation, which could accelerate cognitive and functional progression [82, 83] and increase the risk of mortality [26, 84]. In contrast to other neuropsychiatric symptoms (for example, depression) that might have a fluctuating course, apathy is more stable over time, correlating with the progression of dementia [85].The associations between apathy and survival may be causal or reflect common influences of a third factor on both specific factors of the disease. Apathy can accelerate the rapid decline towards death, or it can represent a marker of other underlying factors, such as anatomical or neurotransmitter alterations, which are correlated with both apathy and survival [81]. On the other hand, difficulty eating, loss of appetite and weight loss are very common in patients with advanced dementia and increase the risk of mortality [24].

In our study, we also found an association between mortality and the presence of psychotic symptoms (delusions and/or hallucinations), as in other studies [12, 24, 25], although this association could not be confirmed in the multivariate analysis. An association with agitation has been reported [12, 24, 25, 29], and one study reported no relationship between subsyndromes and mortality [33].

Neuroleptic treatment in PWD has been associated with mortality in several studies [24, 86–89]. In our case, we found an association only in the univariate analysis, as was the case with psychotic symptoms, which are usually treated with these drugs. Notably, the use of neuroleptics, especially those used for agitation and psychotic symptoms, was shown to be associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events [90] and a higher risk of apathy [80], both of which can increase mortality.

With respect to other sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, mortality increased in older, more dependent patients and those with more severe dementia, which has been described in the literature as being associated with age [12, 24, 25, 88, 91, 92] and with disease severity [25, 88, 91].

In our study, having > 2 points as measured via the Charlson index was associated with mortality. In PWD, comorbidities are frequent, cause an increase in disability, reduce the quality of life of the patient and the caregiver [93] and increase the risk of mortality [24, 92, 94]. There is no unanimity on how to analyse comorbidities in mortality studies. Although the Charlson index is one of the most widely used indices in the assessment of comorbidities [43], it does not include situations closely related to institutionalization or death among elderly individuals, such as hip fracture.

Limitations and strengths

Although limited by geographical area, which may limit its external validity, the population included in our study has allowed us to carry out a prospective study of representative sample of PWD in our region who live and are cared for in the community. There were no expected differences in the evolution of PWD between the two municipalities of the Madrid region where we conducted the study and other places of the national territory, since the characteristics of the patients are similar to those of other territories with a wide representation in terms of age groups, sex and educational levels [11]. Although the sample size can be considered small, compared with other studies, we included our entire eligible population with a low number of refusals to participate and patients not located. In addition, we included patients with dementia of all ages, in any stage of severity and with dementia of any aetiology.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms can be analysed as isolated symptoms, as a group of symptoms or subsyndromes, with the global measure of the NPI scale, among other methods, which makes it difficult to compare studies. In this work, we have chosen some of the measures that best represent the NPSs, that is, the presence or absence of symptoms grouped into subsyndromes and the global values of the NPI scale in which the intensities of twelve NPSs are measured.

The frequency and severity of NPSs differ according to the different subtypes of dementia, which can influence the probability of institutionalization and death. Dementia subtypes were not considered because of the lack of up-to-date and reliable information on all patients and because this question is of relative interest in PC since, in our context, the management of PWD with NPSs is related mainly to the type of symptom that presents.

Notably, the organization and characteristics of residential centres may differ between countries, which in part limits the generalizability of the results. Data published in Spain for the year 2022 indicate that there are more than 5,000 residential centres for the elderly that offer a total of 381,514 places, of which only 14% are publicly owned and managed. These centres have very heterogeneous characteristics and levels of care [95].

A key strength of our study is its prospective design with a 4-year follow-up, which allowed us to provide solid evidence on the role of NPSs in the institutionalization and survival of patients with dementia. This methodological approach addresses the limitations found in previous research and improves the validity and comparability of our findings.

In this work, the NPSs were examined at the beginning of the study, and mortality and institutionalization were verified throughout the 4 years. Our objective was not to determine the change in the pattern of the NPSs, which has already been studied in other studies [96]. Rather, the temporary presence of certain NPSs may have repercussions in the future, either because of the repercussions of the NPSs on the patient or caregiver or because many of these symptoms persist over time.

Few studies that analyse NPSs in PWD have been conducted in PC [8, 48], even though it is at this level of care that their management and monitoring are usually carried out. In Spain, we have only found one study in which they evaluated the risk of mortality in people with apathy and Alzheimer's disease in hospitals [80] and another carried out in people who lived in the community in which they investigated the associations between institutionalization and functional dependence and NPSs [97].

Clinical and research applications

From the perspective of PC, it is necessary to continue investigating the impact of NPSs on institutionalization and mortality, as well as on the quality of life of patients and caregivers by designing studies with larger sample sizes that consider sociocultural factors and monitor the possible biases that may occur in such a complex field due to the multiple interactions of different clinical and sociofamily circumstances.

Neurobehavioral characteristics could be useful for predicting survival [81]. The study of apathy may be of special interest, with the development of more effective and user-friendly measurement tools in clinical practice that allow its early detection [81] and differentiate it from depression to avoid unnecessary treatments. Although apathy has a neuropathological basis [81], it can be associated with treatments such as neuroleptics [80]. These drugs are indicated in the management of other NPSs, such as delusions or agitation, when their intensity entails severe anguish to the patient and/or danger to the caregivers or the patients themselves, while reassessing their need from time to time [72, 98–100]. Antidepressants have also been associated with worsening apathy over time [101]. Investigating the periods of use of neuroleptics and other psychoactive drugs used to treat NPSs and observing their impact on the progression of the NPSs treated, on the appearance of new NPSs or on the triggering of therapeutic cascades may be helpful toward developing management strategies.

We must also continue addressing the question regarding the most appropriate way to measure comorbidity in patients with dementia, evaluating possible groupings of diseases and/or drugs, which allows the design of indices or global measures that can be incorporated into the analyses to better explain the relationships between NPSs and institutionalization or mortality.

Conclusions

The institutionalization and mortality of people with dementia under follow-up in primary care are associated with the intensity of neuropsychiatric symptoms measured with the NPI scale and with the presence of apathy. Mortality was associated with older age, severity of dementia or greater comorbidity, whereas being male or having a low educational level were risk factors for institutionalization.

Given the importance of apathy for both institutionalization and mortality, it seems appropriate to investigate adequate methods of early detection and management of this symptom that can improve the prognosis of patients and help caregivers. In the same way, it is important to see the role that the treatments used in dementia can have in the appearance and/or worsening of apathy, in the worsening of cognitive deterioration and in the secondary use of other drugs by causing therapeutic cascades. It is also advisable to implement training measures, for both health workers and caregivers, to help detect NPSs, provide guidance on their prevention and management, and avoid the initiation and/or prolongation of drug treatments when they are not necessary.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and caregivers who agreed to participate in the study and the researchers Rosalía Delgado Puebla, Paula García Domingo, Erika Hernández Melo and Javier López de Haro de Torres who participated in the initial data collection.

Abbreviations

- NPSs

Neuropsychiatric symptoms

- PWD

People with dementia

- PC

Primary care

- NPI

Neuropsychiatric Inventory

- STROBE

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology

- EHR

Electronic health record

- ICPC

International Classification of Primary Care

- GDS

Global deterioration scale

- CD

Cognitive decline

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- BIC

Bayesian information criterion

Authors’ contributions

VG, MCH and IDC conceived the study. VG, MCH, JM and IDC contributed to the design. VG and MCH were responsible for the data collection. VG, MCH, JM and IDC analysed and interpreted the data. VG and MCH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JM and IDC revised the manuscript and provided substantive contributions. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study received a grant for manuscript translation and publication from the Foundation for Research and Biomedical Innovation in Primary Care (FIIBAP) 2024.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (vgarcia@salud.madrid.org) upon reasonable request. All the data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was carried out following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Alcorcón Foundation University Hospital on September 23, 2015 (for baseline analysis) and July 2, 2019 (for the follow-up study). Informed consent was requested from the caregivers responsible for the patients who were interviewed and, in the case of professional caregivers, from the legal representative of the patient. All caregivers were educated enough to read and understand the informed consent form. At the discretion of the responsible physician, consent was also requested from patients who were considered capable of providing it.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bacigalupo I, Mayer F, Lacorte E, Di Pucchio A, Marzolini F, Canevelli M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of dementia in Europe: estimates from the highest-quality studies adopting the DSM IV diagnostic criteria. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66:1471–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lethin C, Rahm Hallberg I, RenomGuiteras A, Verbeek H, Saks K, Stolt M, et al. Prevalence of dementia diagnoses not otherwise specified in eight European countries: A cross-sectional cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blass B, Ford CB, Soneji S, Zepel L, Rosa TD, Kaufman BG, et al. Incidence and prevalence of dementia among US Medicare beneficiaries, 2015–21: population based study. BMJ. 2025;389: e083034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hao M, Chen J. Trend analysis and future predictions of global burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: a study based on the global burden of disease database from 1990 to 2021. BMC Med. 2025;23: 378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jönsson L, Tate A, Frisell O, Wimo A. The costs of dementia in Europe: an updated review and meta-analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2023;41:59–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haibo X, Shifu X, Tze Pin N, Chao C, Guorong M, Xuejue L, et al. Prevalence and severity of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in community dwelling Chinese: findings from the Shanghai three districts study. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17:748–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liew TM. Symptom clusters of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and their comparative risks of dementia: a cohort study of 8530 older persons. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:1054.e1-1054.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thyrian JR, Eichler TS, Wucherer D, Dreier A, Teipel S, Hoffmann W. Behavioral and psychiatric symptoms in people with dementia in primary care. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:611. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siafarikas N, Selbaek G, Fladby T, Šaltyte Benth J, Auning E, Aarsland D. Frequency and subgroups of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and different stages of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30:103–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Alberca JM, Pablo Lara J, González-Barón S, Barbancho MA, Porta D, Berthier M. Prevalence and comorbidity of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2008;36:265–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.García-Martín V, de Hoyos-Alonso MC, Ariza-Cardiel G, Delgado-Puebla R, García-Domingo P, Hernández-Melo E, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and subsyndromes in patients with different stages of dementia in primary care follow-up (NeDEM project): a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters ME, Schwartz S, Han D, Rabins PV, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as predictors of progression to severe Alzheimer’s dementia and death: the cache county dementia progression study. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:460–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper C, Sommerlad A, Lyketsos CG, Livingston G. Modifiable predictors of dementia in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:323–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afram B, Stephan A, Verbeek H, Bleijlevens MHC, Suhonen R, Sutcliffe C, et al. Reasons for institutionalization of people with dementia: informal caregiver reports from 8 European countries. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:108–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tun SM, Murman DL, Long HL, Colenda CC, Von Eye A. Predictive validity of neuropsychiatric subgroups on nursing home placement and survival in patients with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:314–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, Sands L, Lindquist K, Dane K, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287:2090–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porter CN, Miller MC, Lane M, Cornman C, Sarsour K, Kahle-Wrobleski K. The influence of caregivers and behavioral and psychological symptoms on nursing home placement of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: a matched case–control study. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4: 205031211666187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen YJ, Wang WF, Jhang KM, Chang MC, Chang CC, Liao YC. Prediction of institutionalization for patients with dementia in Taiwan according to condition at entry to dementia collaborative care. J Appl Gerontol. 2022;41:1357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luppa M, Luck T, Brähler E, König HH, Riedel-Heller SG. Prediction of institutionalisation in dementia: a systematic review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26:65–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toot S, Swinson T, Devine M, Challis D, Orrell M. Causes of nursing home placement for older people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29:195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brodaty H, Connors MH, Xu J, Woodward M, Ames D. Predictors of institutionalization in dementia: a three year longitudinal study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40:221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park DG, Lee S, Moon YM, Na DL, Jeong JH, Park KW, et al. Predictors of institutionalization in patients with Alzheimer’s disease in South Korea. J Clin Neurol. 2018;14: 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cepoiu-Martin M, Tam-Tham H, Patten S, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB. Predictors of long-term care placement in persons with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31:1151–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bränsvik V, Granvik E, Minthon L, Nordström P, Nägga K. Mortality in patients with behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: a registry-based study. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25:1101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russ TC, Batty GD, Starr JM. Cognitive and behavioural predictors of survival in Alzheimer disease: results from a sample of treated patients in a tertiary-referral memory clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:844–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang MF, Lee WJ, Yeh YC, Lin YS, Lin HF, Wang SJ, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and mortality among patients with mild cognitive impairment and dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022;121:1705–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cummings JL. The neuropsychiatric inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology. 1997;48(5 Suppl 6):S10-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Der Linde RM, Dening T, Matthews FE, Brayne C. Grouping of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:562–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anatchkova M, Brooks A, Swett L, Hartry A, Duffy RA, Baker RA, et al. Agitation in patients with dementia: a systematic review of epidemiology and association with severity and course. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31:1305–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabins PV, Schwartz S, Black BS, Corcoran C, Fauth E, Mielke M, et al. Predictors of progression to severe Alzheimer’s disease in an incidence sample. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:204–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villars H, Gardette V, Frayssignes P, Deperetti E, Perrin A, Cantet C, et al. Predictors of nursing home placement at 2 years in Alzheimer’s disease: A follow-up survey from the THERAD study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;37:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benoit M, Robert PH, Staccini P, Brocker P, Guerin O, Lechowski L, et al. One-year longitudinal evaluation of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. The REALFR Study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2005;9:95–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wergeland JN, Selbæk G, Bergh S, Soederhamn U, Kirkevold Ø. Predictors for nursing home admission and death among community-dwelling people 70 years and older who receive domiciliary care. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. 2015;5:320–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirono N, Tsukamoto N, Inoue M, Moriwaki Y, Mori E. Predictors of long-term institutionalization in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: role of caregiver burden. Brain Nerve. 2002;54:812–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Vugt ME, Stevens F, Aalten P, Lousberg R, Jaspers N, Verhey FRJ. A prospective study of the effects of behavioral symptoms on the institutionalization of patients with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2005;17:577–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4: e297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cortes F, Nourhashémi F, Guérin O, Cantet C, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Andrieu S, et al. Prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease today: a two-year prospective study in 686 patients from the REAL-FR study. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4:22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gillette-Guyonnet S, Andrieu S, Nourhashemi F, Gardette V, Coley N, Cantet C, et al. Long-term progression of Alzheimer’s disease in patients under antidementia drugs. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:579–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel index for stroke rehabilitation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:703–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, De Leon MJ, Crook T. The global deterioration scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1136–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hermansson J, Carlqvist P, Kennedy K, Pietri G. PRM4 measuring comorbidity in administrative data. Value Health. 2011;14: A421. [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM. How to measure comorbidity. A critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:221–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.González Silva Y, Abad Manteca L, José Fernández-Gómez M, Martín-Vallejo J, de la Red Gallego José Luis Pérez-Castrillón H, Río Hortega Valladolid U. Utility of the Charlson Comorbidity Index in older people and concordance with other comorbidity indices. 2021;14:64–70

- 46.Vilalta-Franch J, Lozano-Gallego M, Hernández-Ferrándiz M, Llinàs-Reglà J, López-Pousa SLO. Neuropsychiatric Inventory: propiedades psicométricas de su adaptación al español. Rev Neurol. 1999;29:15–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aalten P, Verhey FRJ, Boziki M, Bullock R, Byrne EJ, Camus V, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes in dementia: results from the European alzheimer disease consortium - part I. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24:457–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borsje P, Lucassen PLBJ, Bor H, Wetzels RB, Pot AM, Koopmans RTCM. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia in primary care. Fam Pract. 2019;36:437–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liao Y, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Kan CN, Chia RSL, Chai YL, et al. The protective effect of vitamin B12 on neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia-free older adults in a multi-ethnic population. Clin Nutr. 2025;44:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2002;288:1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Corcoran C, Steffens DC, Norton MC, Lyketsos CG, et al. The persistence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Selbæk G, Engedal K, Bergh S. The prevalence and course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home patients with dementia: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:161–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gonfrier S, Andrieu S, Renaud D, Vellas B, Robert PH. Course of neuropsychiatric symptoms during a 4-year follow up in the REAL-FR cohort. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16:134–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Teipel SJ, Thyrian JR, Hertel J, Eichler T, Wucherer D, Michalowsky B, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in people screened positive for dementia in primary care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gort A, Mingot M, March J, Gómez X, Soler T, Nicolás F. Utilidad de la escala de Zarit reducida en demencias. Med Clin (Barc). 2010;135:447–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20:649–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martín M, Salvadó I, Nadal S, Miji L, Rico J. Adaptación para nuestro medio de la escala de sobrecarga del cuidador (Caregiver Burden Interview) de Zarit. Revista de Gerontología. 1996;:338–45.

- 58.Christensen E. Multivariate survival analysis using Cox’s regression model. Hepatology. 1987;7:1346–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–26. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wagenmakers EJ, Farrell S. AIC model selection using Akaike weights. Psychon Bull Rev. 2004;11:192–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams RL. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000;56:645–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.García-Martín V, de Hoyos-Alonso MC, Delgado-Puebla R, Ariza-Cardiel G, del Cura-González I. Burden in caregivers of primary care patients with dementia: influence of neuropsychiatric symptoms according to disease stage (NeDEM project). BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dufournet M, Dauphinot V, Moutet C, Verdurand M, Delphin-Combe F, Krolak-Salmon P, et al. Impact of cognitive, functional, behavioral disorders, and caregiver burden on the risk of nursing home placement. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:1254–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bakker C, de Vugt ME, van Vliet D, Verhey FRJ, Pijnenburg YA, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, et al. Predictors of the time to institutionalization in young- versus late-onset dementia: results from the needs in young onset dementia (Needyd) study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Breitve MH, Brønnick K, Chwiszczuk LJ, Hynninen MJ, Aarsland D, Rongve A. Apathy is associated with faster global cognitive decline and early nursing home admission in dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, König HH, Brähler E, Riedel-Heller SG. Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A systematic review. Age Ageing. 2010;39:31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pinzón-Pulido S, Garrido Peña F, Reyes Alcázar V, Lima-Rodríguez JS, RaposoTriano MF, MartínezDomene M, et al. Factores predictores de la institucionalización de personas mayores en situación de dependencia en Andalucía. Enferm Clin. 2016;26:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Runte R. Predictors of institutionalization in people with dementia: a survey linked with administrative data. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Joling KJ, Janssen O, Francke AL, Verheij RA, Lissenberg-Witte BI, Visser PJ, et al. Time from diagnosis to institutionalization and death in people with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16:662–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heyman A, Peterson B, Fillenbaum G, Pieper C. Predictors of time to institutionalization of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: the CERAD experience, Part XVII. Neurology. 1997;48:1304–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang SW, Chang KH, Escorpizo R, Hu CJ, Chi WC, Yen CF, et al. Using the World Health Organization disability assessment schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) for predicting institutionalization of patients with dementia in Taiwan. Medicine. 2015;94:e2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. London; 2018. [PubMed]

- 73.Hébert R, Dubois MF, Wolfson C, Chambers L, Cohen C. Factors associated with long-term institutionalization of older people with dementia: data from the Canadian study of health and aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M693–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eska K, Graessel E, Donath C, Schwarzkopf L, Lauterberg J, Holle R. Predictors of institutionalization of dementia patients in mild and moderate stages: a 4-year prospective analysis. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. 2013;3:426–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Black CM, Fillit H, Xie L, Research S, Hu X, Kariburyo MF. Economic burden, mortality, and institutionalization in patients economic burden, mortality, and institutionalization in patients newly diagnosed with alzheimer’s disease newly diagnosed with alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61:185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Wahed AS, Saxton J, Sweet RA, Wolk DA, et al. Long-term effects of the concomitant use of memantine with cholinesterase inhibition in Alzheimer disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Belger M, Haro JM, Reed C, Happich M, Argimon JM, Bruno G, et al. Determinants of time to institutionalisation and related healthcare and societal costs in a community-based cohort of patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20:343–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van der Linde RM, Matthews FE, Dening T, Brayne C. Patterns and persistence of behavioural and psychological symptoms in those with cognitive impairment: the importance of apathy. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32:306–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hölttä EH, Laakkonen ML, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS, Pitkälä KH. Apathy: prevalence, associated factors, and prognostic value among frail, older inpatients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:541–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vilalta-Franch J, Calvó-Perxas L, Garre-Olmo J, Turró-Garriga O, López-Pousa S. Apathy syndrome in Alzheimer’s disease epidemiology: prevalence, incidence, persistence, and risk and mortality factors. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33:535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lansdall CJ, Coyle-Gilchrist ITS, Vázquez Rodríguez P, Wilcox A, Wehmann E, Robbins TW, et al. Prognostic importance of apathy in syndromes associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2019;92:E1547-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parrotta I, Maltais M, Rolland Y, Spampinato DA, Robert P, de Souto Barreto P, et al. The association between apathy and frailty in older adults: a new investigation using data from the MAPT study. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24:1985–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu CW, Schneider LS, Soleimani L, Neugroschl J, Grossman HT, Schimming C, et al. Understanding the role of neuropsychiatric symptoms in functional decline in alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2025. 10.1176/APPI.NEUROPSYCH.20250015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nijsten JMH, Leontjevas R, Pat-El R, Smalbrugge M, Koopmans RTCM, Gerritsen DL. Apathy: risk factor for mortality in nursing home patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:2182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Teixeira AL, Gonzales MM, De Souza LC, Weisenbach SL. Revisiting Apathy in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Conceptualization to Therapeutic Approaches. Behav Neurol. 2021;2021:6319826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.López-Pousa S, Olmo JG, Franch JV, Estrada AT, Cors OS, Nierga IP, et al. Comparative analysis of mortality in patients with Alzheimer’s disease treated with donepezil or galantamine. Age Ageing. 2006;35:365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yeh T-C, Tzeng N-S, Li J-C, Huang Y-C, Hsieh H-T, Chu C-S, et al. Mortality risk of atypical antipsychotics for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;39:472–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Connors MH, Ames D, Boundy K, Clarnette R, Kurrle S, Mander A, et al. Predictors of mortality in dementia: the PRIME study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52:967–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Maust DT, Kim HM, Seyfried LS, Chiang C, Kavanagh J, Schneider LS, et al. Antipsychotics, other psychotropics, and the risk of death in patients with dementia: number needed to harm. JAMA Psychiatr. 2015;72:438–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sacchetti E, Turrina C, Valsecchi P. Cerebrovascular accidents in elderly people treated with antipsychotic drugs: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2010;33:273–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Todd S, Barr S, Roberts M, Passmore AP. Survival in dementia and predictors of mortality: a review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28:1109–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee M, Chodosh J. Dementia and life expectancy: what do we know? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:466–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fox C, Smith T, Maidment I, Hebding J, Madzima T, Cheater F, et al. The importance of detecting and managing comorbidities in people with dementia? Age Ageing. 2014;43:741–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peters ME, Rosenberg PB, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Welsh-Bohmer KA, et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in CIND and its subtypes: the cache county study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:416–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Área de Estadísticas de la Subdirección General de Planificación, Ordenación y Evaluación del Instituto de Mayores y Servicios Sociales. Censo de Centros Residenciales De Servicios Sociales en España: Situación año 2022. Ministerio de Derechos Sociales, Consumo y Agenda 2030. Disponible en: https://www.dsca.gob.es/sites/default/files/publicaciones/Censo-centros-residenciales-2022.pdf. 2022.

- 96.Castillo-García IM, López-Álvarez J, Osorio R, Olazarán J, Ramos Garciá MI, Agüera-Ortiz L. Clinical trajectories of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild-moderate to advanced dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;86:861–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Risco E, Cabrera E, Jolley D, Stephan A, Karlsson S, Verbeek H, et al. The association between physical dependency and the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms, with the admission of people with dementia to a long-term care institution: a prospective observational cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:980–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Frederiksen KS, Cooper C, Frisoni GB, Frölich L, Georges J, Kramberger MG, et al. A European academy of neurology guideline on medical management issues in dementia. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1805–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Eyler AE, Hilty DM, Horvitz-Lennon M, Jibson MD, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:543–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Herrmann N, Lanctôt KL, Hogan DB. Pharmacological recommendations for the symptomatic treatment of dementia: the Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia 2012. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013;5 Suppl 1:S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 101.Donovan NJ, Wadsworth LP, Lorius N, Locascio JJ, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, et al. Regional cortical thinning predicts worsening apathy and hallucinations across the Alzheimer disease spectrum. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:1168–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (vgarcia@salud.madrid.org) upon reasonable request. All the data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.