Abstract

The indiscriminate use of antibiotics in food-producing animals contributes to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), posing a global threat. Understanding the factors associated with antibiotic use is critical to combat resistance while maintaining animal health. This study examined antibiotic use practices, mortality rates, biosecurity levels, as well as the associations between biosecurity and antibiotic use, and between biosecurity and mortality, in semi-intensive broiler farms in Kenya.

The study was conducted in 129 semi-intensive farms with total flock sizes between 200 and 2000 birds across three peri-urban counties in Kenya. Data were collected prospectively over one production cycle, with farms visited biweekly using questionnaires and a drug bin approach. Biosecurity levels were assessed by a panel of experts who weighted scores for various external and internal biosecurity subcategories. Directed acyclic graphs (DAG) described potential relationships between explanatory variables, confounders and outcome. Logistic regression analysis was conducted with antibiotic use as the outcome variable. Explanatory variables with P < 0.25 in the univariable logistic regression were included in the multivariable regression. Similarly, linear regression was conducted using mortality as the outcome.

Overall, 72% of farms used antibiotics, primarily for prophylaxis (66%), with erythromycin and oxytetracycline being the most commonly used antibiotics. The median mortality rate across the production cycle was 6%. There was no significant difference in mortality between farms using antibiotics and those not using antibiotics. Biosecurity practices were low, with a median biosecurity score of 14.3/67.9. Univariable screening suggested potential associations between antibiotic use and vaccination of day-old chicks, flock size, cleaning protocol for chicken drinkers, resting period between batches, feed store cleaning, water source, distance from neighbouring farms, and age. However, these were not significant in multivariable logistic regression. Linear regression showed an association between mortality and biosecurity measures, specifically disease management and visitor entry regulation.

This study highlights widespread antibiotic use, low biosecurity implementation, and variability in mortality rates in the farms surveyed. There is a gap in farmers’ implementation of effective biosecurity measures and understanding of prudent antibiotic use. An urgent need exists to develop comprehensive data collection methodologies, education, and interventions to promote responsible antibiotic stewardship and cost-effective biosecurity practices among poultry farmers in Kenya.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12917-025-04948-w.

Keywords: Antimicrobials, Semi-intensive, Livestock, Biosecurity, LMICs

Background

Imprudent use of antibiotics in food-producing animals has been identified as a key contributor to the global threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [1, 2]. AMR poses a significant risk to human health, animal health and welfare, food safety and security, as well as economic development [3]. The latest ANIMUSE report (9th report) by the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) shows a 5% global decrease in antimicrobial use in food-producing animals between 2020 and 2022. Regional trends indicate reductions in Africa (20%), Europe (23%), the Americas (4%), Asia and the Pacific (2%). However, the Middle East reported a notable increase of 43% [4]. While these figures suggest progress in reducing antimicrobial use, particularly in some low-and middle-income regions, the overall demand for antibiotics is expected to rise in coming years, largely driven by the increasing consumption of animal-source protein, especially poultry meat in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) [5].

Poultry meat is the most consumed animal-source protein globally, with LMICs significantly contributing to this consumption due to factors such as affordability, availability, and ease of production [6–9]. Kenya’s poultry industry, like in other LMICs, is experiencing exponential growth driven by increasing demand from a rapidly urbanizing population, increased population growth and improved standard of living [10]. This growth has driven more intensive production practices, such as larger flock sizes, which place greater strain on limited resources and increase the risk of disease outbreaks [11, 12]. Consequently, there is an increase in antibiotic usage for treating or preventing poultry infections and growth promotion [13, 14]. This trend is particularly pronounced in broiler production systems, characterized by rapid growth rates and high stocking densities [15, 16]. Broilers, primarily raised for meat, have a shorter production cycle compared to layers, leading to a more intensive antimicrobial use to prevent and treat diseases within a shorter timeframe [16–18].

In Kenya, chicken production systems are categorized into four distinct sectors based on their levels of biosecurity: large-scale commercial (Sector 1) with high biosecurity; medium-scale commercial (Sector 2) with moderate to high biosecurity; small-scale commercial (Sector 3) with low to minimal biosecurity; and backyard farming (Sector 4) with minimal biosecurity [19]. Most poultry farmers in Kenya operate with small (Sector 3) and medium-scale (Sector 2) systems, managing a total flock of 200–2000 birds per farm. These farms, referred to as semi-intensive farms in our study, vary in scale depending on economic capacity, disease management practices and market demand [20, 21].

Broiler production in Kenya has shown significant growth over the recent years, reflecting the increasing demand for poultry meat. Nationally, the number of broiler chicken slaughtered reached 66,672,135 in 2022 and increased slightly to 66,873,016 in 2023. Correspondingly, poultry meat production rose to 93,341 tons in 2022 and 93,622 tons in 2023. Regional data also reflect varying trends in broiler populations. For instance, Kiambu county recorded a population of 533,562 broilers in 2022, which declined to 439,334 in 2023. Conversely, Kajiado county showed a sharp rise from 273,370 in 2022 to 1,004,948 in 2023, indicating increasing investments in broiler farming in the region. Machakos county reported a relatively stable broiler populations with 421,177 in 2022 and 446,989 in 2023 [22]. These statistics highlight the dynamic nature of broiler production across different counties, informing the selection of study sites and the interpretation of antibiotic use patterns.

Several studies have highlighted the widespread use of antibiotics in the Kenyan poultry industry, largely enabled by the over-the-counter availability of antibiotics without prescription [23–27]. Kariuki et al., 2023 [13] investigated antibiotic usage patterns in Kenyan poultry farms and found that a significant proportion of farmers routinely administer antibiotics to their chicken, often without proper veterinary oversight. Other studies in Kenya have reported high levels of antibiotic usage in the poultry industry where tetracyclines and sulfonamides, which are broad-spectrum antibiotics, were frequently used and preferred by farmers as they are affordable compared to other antibiotics [14, 24]. However, there is a paucity of information characterizing antibiotic use (administered for prophylaxis or therapy) among semi-intensive broiler farmers– those rearing between 200 and 2000 broilers, typically in semi enclosed structures (Sectors 2 & 3) and using commercial feed. In Kenya, the addition of antibiotics is not allowed in imported feed according to Veterinary Medicine Directorate (VMD) [28]. Locally produced feed could, in theory, contain antibiotics, as there is currently no law explicitly prohibiting their use as feed additives and feed manufacturers are not required to report on antibiotic usage. While a few studies from Kenya documented widespread antibiotic use in poultry systems, most provide only broad overviews without collecting granular data on drivers of use [13, 25, 27, 29]. Our study aims to fill this gap by offering a more detailed and system-specific analysis of the factors influencing antibiotic use within semi-intensive broiler production.

Understanding the factors that influence antibiotic use in semi-intensive broiler farms is crucial for identifying stewardship interventions. Our study aimed to determine antibiotic use practices focusing on the purpose and type of antibiotic used in Kenyan semi-intensive broiler farms. Additionally, we aimed to estimate mortality rates and biosecurity levels in the study farms and the associations between biosecurity and antibiotic use as well as between biosecurity and mortality.

Materials and methods

Study location and identification of study farms

The study was purposively conducted in Kajiado, Kiambu, and Machakos counties of Kenya. These peri-urban counties neighbour Nairobi city, which serves as a major market for poultry and its products. They are also among the leading counties in poultry production [11, 19].

In the absence of a central farm registry, a farm mapping exercise was undertaken to develop our sampling pool. This involved visiting and collecting demographics and spatial data from a total of 1711 semi-intensive broiler farms in the three counties: 1461 farms (85%) in Kiambu, 170 (10%) in Kajiado, and 80 (5%) in Machakos counties. This mapping was conducted in collaboration with local government and private animal health practitioners and supplemented by snowballing sampling through farmer networks. From this mapped pool, 129 farms were randomly selected for inclusion in the study. Eligible farms were those keeping between 200 and 2000 broiler birds and having at least one flock of broilers less than 14 days old at the time of the first visit. The random selection was performed across all mapped farms.

Study design and data collection

A prospective study was conducted between November and December 2022 following one flock per farm across 129 previously identified farms. On farms with multiple flocks, only a single flock was tracked. For example, a farm with 200 birds in total, divided into two flocks, a single flock of 100 birds would be selected for follow up. Each selected flock was visited every 14 days until the end of its production cycle, with a maximum of four visits depending on the length of the production cycle (average of 33–35 days) and the timing of the first visit. A flock was defined as a group of chickens of the same age housed together. A written consent was obtained from the farm owner or manager interviewed. To ensure appropriate adherence to biosecurity measures, the field boots and equipment were disinfected between farm visits, disposable overalls were worn, research vehicles were kept outside the farm and the tyres disinfected between visits.

Data were collected at two levels– farm-level and flock-level - using the FarmUse questionnaire [30]. The questionnaire captured a range of information, including farmer demographics (e.g., duration of involvement in poultry farming, attitudes toward antibiotic use), farm characteristics (e.g., total number of birds, presence of other livestock), and farm management practices (e.g., biosecurity measures, animal health practices). We also gathered data on - access to and use of antimicrobials, as well as flock level information on sales and mortality. Seven veterinarians were trained as field enumerators for data collection. The questionnaire was administered to either the farm owner or manager, and the interviews lasted approximately two hours. The questionnaire was pretested on six farms that were part of the mapped farm pool and met the study’s inclusion criteria but were not among the 129 farms selected for longitudinal follow-up. During pretesting, we assessed whether farm owners or managers clearly understood the questions and were able to provide appropriate responses. We also evaluated whether the enumerators were able to administer the questionnaire consistently and as intended. Additionally, we verified that the data were accurately recorded in the digital forms, successfully uploaded without technical errors and correctly displayed in the exported spreadsheet. Based on the pretest findings, the questionnaire was refined to improve clarity, flow and overall data quality.

During the initial visit, comprehensive data were collected on various aspects, including farmer and farm demographics, and farms biosecurity practices at farm level. At flock level, information on administered medicines and vaccines for the period between day old and the time of first visit, and birds’ health status were recorded. At the end of the first visit, farmers were requested to dispose of all packaging (bottles, sachets, etc.) “of any medicines used for poultry in the study flock into provided ‘Drug bins’ (containers) throughout the complete production cycle”.

In the subsequent visits, flock details, health status, medicines and vaccines administered were collected, with the help of a medicine photobook– a visual guide developed by the research team to help farmers identify the medicines they used [30]. Additionally, enumerators ensured at the first visit that participants understood that they should dispose of all empty medicine packaging in the drug bins, and they collected all the contents from the bins at the subsequent visits. A review of the drug bins contents was conducted to extract information from the empty medicine packaging and identify antibiotics, which was cross-referenced with the records from the questionnaire. Data were collected via Open Data Kit (ODK) [31] and uploaded to secured databases at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Nairobi, Kenya.

Data management and analysis

Data analysis was conducted using R statistical software version 4.2.2 [32]. Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics involving summarizing categorical variables such as antibiotic use using proportions, while continuous variables such as mortality using means, standard deviations, medians, and interquartile ranges.

Antibiotics use was defined as any reported instance of use, whether for disease prevention, disease treatment or post-vaccination at any point in the production cycle. Data on antibiotic use was collected through the questionnaire administered during farm visits and verified by examining the antibiotic packages found in the drug bins. Based on this information, each flock was classified as either having used antibiotics or not.

The production cycle mortality rate was determined by calculating the cumulative number of dead chickens per flock divided by the total number of chickens at the beginning of the cycle. The mortalities were compared between farms using antibiotics and those not using antibiotics during the cycle using the Mann-Whitney U test.

To assess the biosecurity of the study farms, a panel of ten experts with poultry experience in LMICs - including veterinarians, a microbiologist, and poultry diseases specialists - allocated weighted scores tailored to the Kenyan context, based on the biosecurity data collected from the study farms. The categorization of biosecurity measures into external and internal was guided by the Biocheck.UGent™, tool for broiler production, as described by Gelaude et al. [33, 34]. The process involved assigning scores to each question within the questionnaire, with scores ranging between 0.5 and 2. The scores were then aggregated for each subcategory (Supplementary Materials 1). The total score included both internal and external biosecurity, with scores ranging from zero (indicating the total absence of any biosecurity measure) to 100 (reflecting perfect biosecurity measures). In our study, data obtained for external biosecurity subcategories included the purchase of day-old chicks, infrastructure and biological vectors, feed and water management, visitor and farm worker protocols, manure and carcass disposal practices, and farm location. Internal biosecurity subcategories comprised of disease management strategies, cleaning and disinfection protocols and materials and measures between compartments (Supplementary Materials 1). We did not collect data on the depopulation of broilers and materials supplies in the external biosecurity subcategories. Therefore, our total score was 67.9 where maximum internal biosecurity was 25.6 and external was 42.3.

We constructed a directed acyclic graph (DAG) a priori, using the DAGgitty package [35] to illustrate potential relationships between possible explanatory variables, confounders, and the outcome - antibiotic use - during the current production cycle (Supplementary Material 2). The DAG was used primarily for conceptual clarification and to support our understanding on potential causal pathways, but it did not guide variable selection for the logistic regression model. Univariable logistic regression analyses were then performed to test for associations between the explanatory variables and antibiotic use as the outcome variable. The explanatory variables assessed in the univariable regression included vaccination of day old chicks, vaccination of chicken during the production cycle, existence of a separate area for sick chicken, flock size, average number of chicken per flock, existence of a functional footbath at the chicken house, existence of protocols for cleaning chicken drinkers and feeders, resting period between batches, checking disinfection outcome, existence of a feed store cleaning process, division of the farm into clean(restricted) and dirty areas, existence of an automated water drinking system, source of water, location of feed storage within the farm, storage of feed within the store (on the floor, elevated), chicken feed store sealed from vermin and pets, fencing of the farm, entry or presence of wild birds into the chicken house, entry or frequency of vermin into the chicken house, rearing of backyard chicken, keeping pets, entry of visitors into the chicken house, existence of a visitor entry protocol, distance to neighbouring farms, number of flocks per farm and demographic factors i.e. age, level of education, broiler farming experience, and county. Explanatory variables with P < 0.25 in univariable screening were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. Variable selection for the final multivariable model was performed using backward elimination, based on the likelihood ratio test (LRT) using ‘drop1’ function until only statistically significant variables (P < 0.05) remained.

We also conducted univariable linear regression analyses to test for associations between biosecurity practices and mortality (outcome). Specifically, we used the weighted overall scores for each biosecurity category per farm as explanatory variables. These categories included: purchase of day-old chicks, infrastructure and biological vectors, feed and water management, visitor and farm worker protocols, manure and carcass disposal practices, farm location, disease management strategies, cleaning and disinfection protocols and materials and measures between compartments and county. Variables with P < 0.25 in the univariable screening were included in a multivariable linear regression model. The same backward elimination process was applied until the statistically significant variables (P < 0.05) remained. Prior to conducting the linear regression, the mortality data was log-transformed to approximate a normal distribution of residuals. The fit of the final model was evaluated using a normal Q-Q plot.

Results

Farm and farmers socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 129 semi-intensive broiler farms in the three study counties were included in the study (Fig. 1). Overall, 81% of the study farms were located in Kiambu, 15% in Kajiado and 4% in Machakos counties, corresponding to the distribution of the mapped farms population.

Fig. 1.

Locations of study farms. Map (A) illustrates Kenya and highlights the three study counties (blue shade). Map (B) provides a detailed view of the mapped locations (red dots) of the farms within these three study counties. Map (C) provides a detailed view of the specific locations (blue dots) of the farms within these three study counties, including Nairobi County, the market hub for the study counties, and International Livestock Research Institute (red dot)

The median flock size was 400 (IQR: 300 to 510) (Fig. 2). In addition to rearing broilers, the majority of the farmers also kept dual-purpose chicken (i.e. raised for both meat and eggs,40%) and cattle (34%).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of flock size in the study farms. This plot illustrates the distribution of flock sizes observed during one production cycle across 129 farms

The respondents had a median age of 50 years (IQR: 43 to 59). The majority were female (79%). Half of the farmers had up to secondary school education. Additionally, 57% reported having attended a day-long training on poultry-related production practices, with half of these trainings provided by drug or feed companies. The topics included in these trainings, ranked from most to least common, included increasing production, biosecurity, vaccination, treating diseases, detecting diseases, and antimicrobial resistance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of demographic characteristics of semi-intensive broiler study farmers in Kenya

| Variable | Antibiotic use | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 93) n (%) | No (N = 36) n (%) | |

| County | ||

| Kajiado | 12 (13) | 7 (19) |

| Kiambu | 77 (83) | 28 (78) |

| Machakos | 4 (4.3) | 1 (2.8) |

| Respondent | ||

| Manager | 3 (3.2) | 5 (14) |

| Owner | 90 (97) | 31 (86) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 75 (81) | 27 (75) |

| Male | 18 (19) | 9 (25) |

| Age group | ||

| 21–30 | 0 | 3 (8.3) |

| 31–40 | 15 (16) | 3 (8.3) |

| 41–50 | 28 (30) | 16 (44) |

| 51–60 | 29 (31) | 7 (19) |

| 61–80 | 21 (23) | 7 (19) |

| Marital status ( N = 121*) | ||

| Married | 73 (81) | 26 (84) |

| Single | 8 (8.9) | 2 (6.5) |

| Widowed | 7 (7.8) | 2 (6.5) |

| Divorced/separated | 2 (2.2) | 1 (3.2) |

| Poultry related training | ||

| Day course | 57 (61) | 17 (47) |

| Diploma/certificate | 2 (2.2) | 0 |

| Other | 2 (2.2) | 0 |

| Topics trained | ||

| Increasing production | 47(51) | 7(19) |

| Biosecurity | 25(27) | 10(28) |

| Vaccination | 17(18) | 4(11) |

| Treating diseases | 15(16) | 5(14) |

| Detecting diseases | 14(15) | 3(8) |

| Antimicrobial resistance | 1(1.1) | 2(6) |

*The farm manager were not asked the question on marital status

Antibiotic use practices

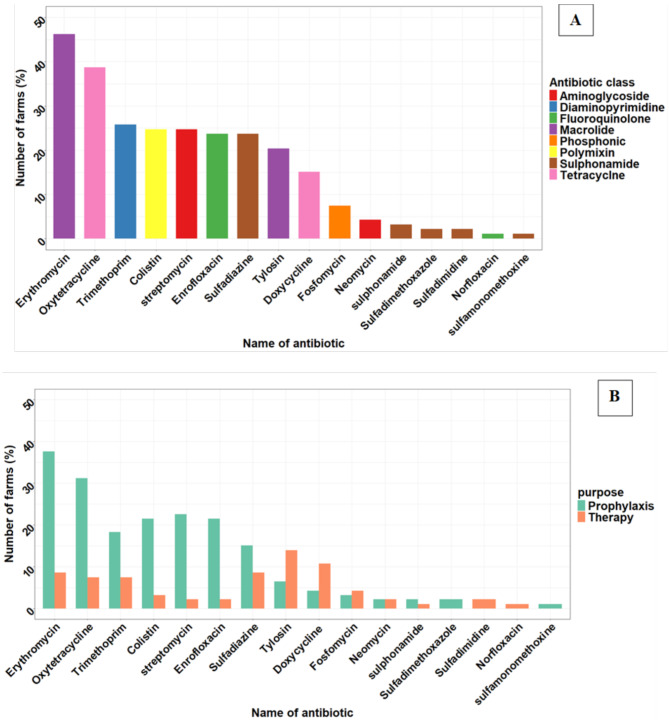

A total of 72% (n = 93/129) of the flocks used antibiotics during the production cycle. Antibiotics were primarily reported to be used solely for prophylaxis (66%, n = 61/93), solely for therapy (20%, n = 19/93), or both prophylaxis and therapy (14%, n = 13/93). Among the farms using antibiotics, 45% (42/93) used antibiotics combined with vitamins, 43% (40/93) used antibiotics combined with other antibiotics, 22% (20/93) used single antibiotics, and 4% (4/93) used combined antibiotics with vitamins and mineral supplements. Across the 93 farms, a total of 16 antibiotics from eight classes were reported, with erythromycin (46%), and oxytetracycline (39%) being the most commonly used (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Antibiotic use in 129 semi-intensive broiler farms one production cycle across three counties in Kenya. Panel A illustrates the overall antibiotic use and classification by antibiotic class among the study farms. Panel B breaks down antibiotics use by purpose, highlighting those used for prophylaxis and therapy

Mortality

The mean mortality rate across the production cycle on the sampled farms was 11% with some farms experiencing higher rates (Range: 1 to 100%, Fig. 4). There were no significant differences in mortality rates between farms using antibiotics and those not using antibiotics (P = 0.2).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of production cycle mortality rates across the 129 study flocks

Biosecurity practices

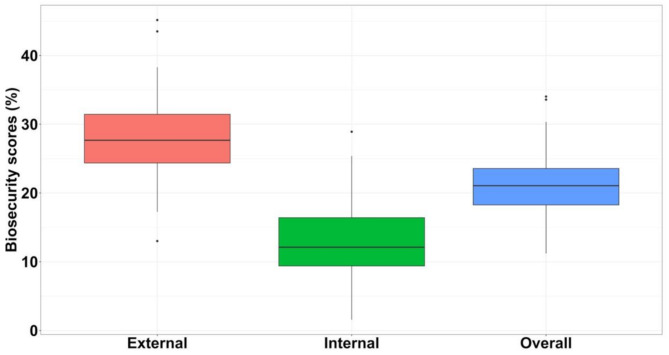

The total median biosecurity score for the study farms was 14.3/67.9 (IQR: 12.4 to16.0). Specifically, the farms had a median external biosecurity score of 11.7/42.3 (IQR: 10.3 to13.3), and a median internal biosecurity score of 3.1/25.6 (IQR: 2.4 to 4.2) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

External, internal, and overall biosecurity scores in 129 semi-intensive broiler farms across the three counties

Among the top external biosecurity measures, infrastructure and biological vectors scored a median of 6/10 (IQR = 5.2 to 6.7) and feed and water scored a median of 3.4/8 (IQR: 2.4 to 4.4). For internal biosecurity, cleaning and disinfection scored a median of 2.3/11.6 (IQR:1.3 to 2.8) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

External and internal biosecurity subcategories scores in 129 semi-intensive farms across three counties in Kenya

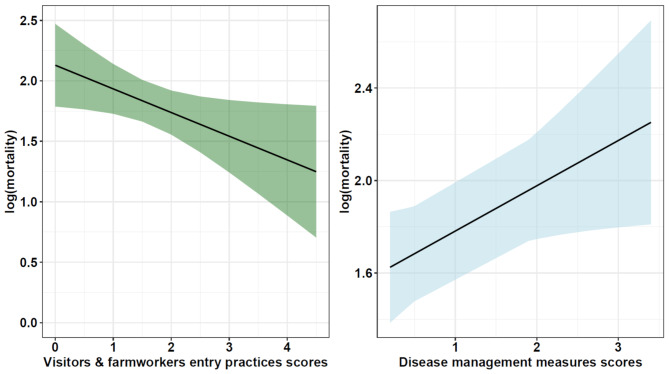

The univariable screening analysis suggested potential associations between various explanatory variables and antibiotic use (with P < 0.25). The variables identified included vaccination of day-old chicks, flock size, the existence of protocol for cleaning chicken drinkers, the resting period between batches, the existence of a feed store cleaning process, the source of water, the distance to neighbouring farms and age (Table 2). These variables were included in the multivariable logistic regression, but after the backward selection process, no variable remained in our final best fitting model according to the LRT. Conversely, farms that had implemented disease management practices (OR = 1.2; CI– 1.0,1.5,P = 0.03), and visitor and farm workers biosecurity measures (OR = 0.8;CI– 0.7,1.0, P = 0.03) were associated with mortality rates (Fig. 7).

Table 2.

Univariable logistic analysis results for antibiotic use in 129 semi-intensive broiler farms in Kenya

| Variable | Levels | Antibiotic use | Coefficient | OR(95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 93) n (%) or median (IQR) | No (N = 36) n (%) or median (IQR) | |||||

| Internal biosecurity | ||||||

| Disease management | ||||||

| Day old chicks vaccinated | No | 19(20) | 4(11) | 1.56 | Ref | |

| Yes | 74(80) | 32(89) | -0.72 | 0.5 (0.2,1.6) | 0.22* | |

| Vaccination during the production cycle | No | 48 (52) | 18 (50) | 0.98 | Ref | 0.87 |

| Yes | 45 (48) | 18 (50) | -0.39 | 0.9 (0.4.2.0) | ||

| Farms have separate area for sick chicken | No | 59 (63) | 24 (67) | 0.89 | Ref | |

| Yes | 34 (37) | 12 (33) | 0.14 | 1.2(0.5,2.6) | 0.73 | |

| Flock size | Median (IQR) | 400 (300, 600) | 350 (300, 425) | 0.001 | 1(1,1) | 0.22* |

| Average number of chicken per flock | Median (IQR) | 400 (300, 500) | 400 (300, 550) | 0.001 | 1(1,1) | 0.92 |

| Cleaning and disinfection | ||||||

| Farms have footbath per chicken room | No | 74 (80) | 28 (78) | 0.97 | Ref | |

| Yes | 19 (20) | 8 (22) | -0.11 | 0.9(0.4,2.3) | 0.82 | |

| Farms have drinkers cleaning protocol | No | 20(22) | 12(33) | 0.51 | Ref | |

| Yes | 73(78) | 24(67) | 0.6 | 1.8(0.8,4.3) | 0.17* | |

| Farms have feeders cleaning protocol | No | 27 (29) | 12 (33) | 0.81 | Ref | |

| Yes | 66 (71) | 24 (67) | 0.2 | 1.2(0.5,2.8) | 0.63 | |

| Resting period between batches | < 7 days | 32 (34) | 8 (22) | 1.39 | Ref | |

| 8–14 days | 46 (49) | 20 (56) | -0.76 | 0.5(0.2,1.5) | 0.20* | |

| 15–30 days | 15 (16) | 8 (22) | -0.55 | 0.6(0.2,1.5) | 0.25* | |

| Farmers check disinfection outcome | Never | 47 (51) | 17 (47) | 1.02 | Ref | |

| Sometimes | 13 (14) | 2 (5.6) | 0.85 | 2.4(0.5,11.5 | 0.39 | |

| Always | 33 (35) | 17 (47) | -0.35 | 0.7(0.3,1.6) | 0.29 | |

| Chicken feed store cleaning procedure | None | 19 (20) | 6 (17) | 1.15 | Ref | |

| Sweep | 40 (43) | 12 (33) | 0.05 | 1.1(0.3,3.2) | 0.93 | |

| Clean and disinfect | 22 (24) | 14 (39) | -0.7 | 0.5(0.2,1.6) | 0.23* | |

| Sweep & clean with water | 12 (13) | 4 (11) | -0.05 | 1.0(0.2,4.1) | 0.94 | |

| Farm divided(clean-restricted area/dirty area) | No | 72 (77) | 25 (69) | 1.06 | Ref | |

| Yes | 21 (23) | 11 (31) | -0.41 | 0.7(0.3,1.6) | 0.35 | |

| Materials and measures between compartments | ||||||

| No. of locks per farm | Median(IQR) | 2 (1, 2) | 2(1, 3) | -0.06 | 0.9(0.6,1.4) | 0.75 |

| External biosecurity | ||||||

| Feed and water | ||||||

| Farms have chicken automated drinkers | No | 82 (88) | 29 (81) | 1.04 | Ref | |

| Yes | 11 (12) | 7 (19) | -0.59 | 0.6(0.2,1.6) | 0.27 | |

| Farms’ water source | Dam | 4 (4.3) | 3 (8.3) | 0.29 | Ref | |

| Borehole | 45 (48) | 21 (58) | 0.47 | 1.6(0.3,7.8) | 0.56 | |

| Municipal | 39 (42) | 10 (28) | 1.07 | 2.9(0.6,15.2) | 0.20* | |

| Rainwater | 5 (5.4) | 2 (5.6) | 0.63 | 1.9(0.2,17.3) | 0.58 | |

| Location of chicken feed store | Within the chicken house | 49 (53) | 20 (56) | 0.89 | Ref | |

| Separate house | 44 (47) | 16 (44) | 0.12 | 1.1(0.5,2.4) | 0.77 | |

| Storage of chicken feed | On the floor | 31 (34) | 16 (44) | 0.66 | Ref | |

| Elevated | 61 (66) | 20 (56) | 0.45 | 1.6(0.7,3.5) | 0.26 | |

| Chicken store sealed | No | 46 (50) | 22 (61) | 0.74 | Ref | |

| Yes | 46 (50) | 14 (39) | 0.45 | 1.6(0.7,3.4) | 0.26 | |

| Infrastructure and biological factors | ||||||

| Farm fenced | No | 23 (25) | 10 (28) | 0.83 | Ref | |

| Yes | 70 (75) | 26 (72) | 0.16 | 1.2(0.5,2.8) | 0.72 | |

| Wild animal entry into the farms | Yes | 32 (34) | 13 (36) | 0.9 | Ref | |

| No | 61 (66) | 23 (64) | 0.07 | 1.1(0.5,2.4) | 0.86 | |

| Frequency of vermin problem | Often | 42 (45) | 18 (50) | 0.85 | Ref | |

| Sometimes | 37 (40) | 11 (31) | 0.37 | 1.4(0.6,3.4) | 0.41 | |

| Never | 14 (15) | 7 (19) | -0.15 | 0.9(0.3,2.5) | 0.78 | |

| Farms keep backyard chicken | Yes | 48 (52) | 15 (42) | 1.16 | Ref | |

| No | 45 (48) | 21 (58) | -0.4 | 0.7(0.3,1.5) | 0.31 | |

| Farms keep pets | None | 22 (24) | 6 (17) | 1.3 | Ref | |

| Cats | 19 (20) | 10 (28) | -0.66 | 0.5(0.2,1.7) | 0.28 | |

| Dogs | 8 (8.6) | 5 (14) | -0.83 | 0.4(0.1,1.8) | 0.26 | |

| Dogs & cats | 44 (47) | 15 (42) | -0.22 | 0.8 (0.3,2.4) | 0.68 | |

| Visitors and farmworkers | ||||||

| Farms allow visitor entry | Yes | 68 (73) | 27 (75) | 0.92 | Ref | |

| No | 25 (27) | 9 (25) | 0.1 | 1.1(0.5,2.7) | 0.83 | |

| Farms have visitor entry protocol | No | 19 (20) | 7 (19) | 0.99 | Ref | |

| Yes | 74 (80) | 29 (81) | -0.06 | 0.9(0.4,2.5) | 0.9 | |

| Location of the farm | ||||||

| Distance to neighbouring farms | Less than 500 | 40 (43) | 21 (58) | 0.64 | Ref | |

| Between 500–1 km | 34 (37) | 7 (19) | 0.94 | 2.6(1.0,6.7) | 0.05* | |

| More than 1 km | 19 (20) | 8 (22) | 0.22 | 1.3(0.5,3.3) | 0.66 | |

| Demographic factors | ||||||

| Age | Median (IQR) | 52 (43, 59) | 47 (43, 56) | 0.03 | 1.0(0.9,1.1) | 0.09* |

| Farmers’ level of education | Primary | 19 (20) | 9 (25) | 0.75 | Ref | |

| Secondary | 48 (52) | 17 (47) | 0.29 | 1.3(0.5,3.5) | 0.56 | |

| Tertiary | 26 (28) | 10 (28) | 0.21 | 1.2(0.4,3.6) | 0.7 | |

| Farmers broiler farming experience | Median (IQR) | 6 (3, 10) | 5.5 (3, 10) | 0.002 | 1(1.0,1–1) | 0.93 |

| County | Machakos | 4 (4) | 1 (3) | 1.39 | Ref | |

| Kajiado | 12 (13) | 7 (19) | -0.85 | 0.4 (0,4.6) | 0.49 | |

| Kiambu | 77 (83) | 28 (78) | -0.37 | 0.7 (0.1,6.4) | 0.74 | |

Summary of farms with internal and external biosecurity measures and demographic factors, in relation to antibiotic use. The associations between biosecurity measures and antibiotic use are presented, displaying the model coefficients, odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI), and p-values. Values marked with an asterisk (*) had P < 0.25 and were included in multivariable model

Fig. 7.

Effect of Disease Management and Visitor and Farmworker Practices on Mortality Rate. The plot shows predicted mortality rates based on scores for visitor and farmworker practices (green plot) and disease management practices (blue plot). Higher scores indicate greater adoption of these practices by farmers. The shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals around the predicted values

Discussion

In this study, we determined the proportion of antibiotic use, biosecurity practices, and mortality, and investigated the association between biosecurity practices and antibiotic use, as well as between biosecurity practices and mortality, in semi-intensive broiler farms in selected counties in Kenya over one production cycle. Mortality rates were generally low but highly variable within the low range, and two-thirds of the farms reported antibiotic use. Implementation of biosecurity measures was generally low, and more than half of the farms did not vaccinate their chickens during the cycle. While certain factors such as cleaning protocols for chicken drinkers and feeders, resting period between batches, feed store cleaning process, water source, and distance to neighbouring farms suggested an association with antibiotic use in the univariable screening analysis, none of these variables remained significant in the multivariable model. No difference in mortality was observed between farms using and not using antibiotics. However, certain biosecurity practices such as the implementation of disease management practices and the regulation of entry access for visitors and farm workers showed a significant association with mortality.

Two-thirds of the farmers reported using antibiotics primarily for prophylaxis. The use of antibiotics for disease prevention is a common practice in Kenya [13, 14, 24, 25] and in other LMICs [36–39], reflecting a widespread but often irrational approach to poultry disease management -particularly when the risk of disease is not well-defined nor evidence based. This practice frequently leads to indiscriminate and unnecessary use in healthy animals. In many cases, prophylaxis is used as a workaround for underlying issues such as poor biosecurity, inadequate hygiene, or inadequate vaccination rather than addressing the actual drivers of disease. While there may be specific scenarios where preventative use is justified, the routine, non-targeted administration of antibiotics to healthy animals is not necessarily rational nor responsible. Day-old chicks (DOCs) are legally required to be vaccinated against Marek’s disease at the hatchery, and many suppliers also routinely vaccinate against Newcastle disease and infectious bronchitis. During the grow-out period, additional vaccinations—particularly for Newcastle disease and Gumboro (infectious bursal disease) (Table 2)—may be administered depending on farmer knowledge, available resources and access to vaccines. However, we do not have specific vaccination records for each farm included in the study as it is not required by law for farmers to vaccinate broilers nor keep records.

Among the study farms, the most commonly used antibiotics were erythromycin and oxytetracycline. Their popularity can be attributed to several factors: their broad-spectrum effectiveness against a wide range of bacteria, low cost, easy accessibility, and previous success in similar conditions [13, 25]. Similar findings were reported in studies from Tanzania, Ghana, and Kenya [13, 24, 29, 40, 41], where tetracyclines, sulfonamides, fluoroquinolones, and macrolides were commonly used in poultry farming.

The widespread use of antibiotics, with fourteen out of sixteen antibiotics being primarily for prophylaxis purposes, combined with the common practice of purchasing products that contain both antibiotics and vitamins and minerals, raises concerns about potential overuse and misuse in broiler production. These combined formulations may lead farmers to unintentionally administer antibiotics when their intention is to support flock nutrition. Notably, half of the antibiotics used were classified as critically important antibiotics for human medicine, including macrolides, fluoroquinolones, phosphonic acid derivatives, and polymyxins. Highly important antibiotics, including tetracyclines and sulfonamides, were also commonly used in the study farms [42]. The extensive use of these antibiotics suggests a significant lack of awareness regarding prudent use of antibiotics. This issue has been reported in other countries in Europe, America, Asia, and Africa [24, 41, 43–48]. The Veterinary Medicine Directorate (VMD), which regulates veterinary and agricultural products in Kenya, does not license imported commercial feed containing antibiotics. While there is no formal prohibition, locally produced feed could theoretically contain antibiotics. A proposed guideline by VMD [28], if adopted, would explicitly ban the use of antibiotics as feed additives. Nonetheless, it remains possible that some feed manufacturers, agrovets or farmers add additives into feed either for growth promotion or as a route of administration for antibiotics for therapeutic or prophylaxis purposes. However, we did not investigate this practice, which remains an important area for future research.

Broiler farming is characterized by a short production cycle, rapid growth rates and high stocking density necessitating stringent measures to prevent the entry and spread of diseases [16, 18]. Our study showed high variability in mortality rates across farms, but these rates did not differ significantly between farms using antibiotics and those not using them. This suggest that factors other than antibiotic use, such as disease exposure, feed quality, growth rates, feed conversion ratio, vaccination schedules (including vaccine quality) and the quality of day-old chicks may influence mortality. However, we did not investigate these factors in this study.

Overall, limited biosecurity practices were observed on the farms. Biosecurity is an essential tool for supporting standard poultry farming, especially in countries where farmers are facing continuous disease challenges that spread due to inadequate implementation of farm biosecurity [49–51]. Previous studies in LMICs including Kenya have shown that farmers lack a comprehensive understanding of which biosecurity measures to implement, the rationale behind their implementation or the ability to implement them [29, 52–54]. Our study suggested mixed effectiveness of biosecurity measures. The observed association between disease management measures and mortality may indicate that these measures alone are insufficient to reduce mortality or are more commonly adopted by farms already experiencing higher disease burdens. In contrast, the implementation of visitors and farmworkers entry regulations was associated with reduced mortality, suggesting a potential protective effect, highlighting the importance of controlling farm access. It is also possible that farmers are relying primarily on a few, easily implementable biosecurity measures, mostly structural or equipment based, combined with antibiotic use, which they may perceive as a more cost-effective approach [29, 54]. Our findings highlight the need to evaluate the cost-effectiveness and sustainability of biosecurity measures that could be implemented in the context of the production intensity of the type of farms studied here.

Our regression analysis did not reveal significant associations between putative drivers and antibiotic use. Most of the study farms are homogeneous in practices, investments and adherence to biosecurity measures, receiving day-old chicks and other inputs from similar sources, making it difficult to identify factors that affect the differences in antibiotic use. It is possible that we did not include all the factors influencing antibiotic use in our study. These factors could include disease exposure, access to antibiotics, knowledge of antibiotics use and attitude towards their use, such as the belief that antibiotics are necessary for better productivity and reduced mortality and fear of loss [55]. Additionally, the source and quality of day-old chicks could be a critical factor in producing broilers with low morbidity and mortality [56]. Further investigation into these additional variables and practices may provide a better understanding of the complexities surrounding antibiotic use in our study population.

A limitation of our study is that, although we examined a wide range of putative factors associated with antibiotic use, some relevant relationships may have been missed. We have no information about specific requirements that the farmers were subject to due to specific contracts, where they might have to fulfil specific biosecurity measures and the like. Such requirements or specific contracts with specific stores could lead to residual confounding effects. Also, we started the study with farms with broilers at different ages, from day-old chicks to two-week-old, leading to unsynchronized data collection. Consequently, for farms where birds were already more than a day old at the time of the first visit, mortality and antibiotic use data were collected retrospectively. This could introduce the possibility of recall bias, as farmers may have forgotten or misreported the number of birds that died, or the antibiotics administered during the early days of the flock. Additionally, data were collected over a relatively short period (November to December), which may not capture seasonal variations in disease occurrence or antibiotic use. Environmental conditions and management practices often shift across seasons, and this temporal limitation could introduce bias into our findings. Another limitation is the use of drug bins to collect empty medicine packaging, which, while a useful tool for monitoring on-farm antibiotic use, may be subject to bias, as some farmers may have unintentionally or intentionally omitted packaging. We attempted to limit this bias by regularly engaging farmers, visually showing them the medicine packages, they may have used. However, some underreporting of antibiotic use may have still occurred. Despite these limitations, our findings indicate extensive antibiotic use. There is a need for systematic quantitative data on antibiotic use, which is lacking in many LMICs [57]. Such data would enable more accurate measurement of antibiotic usage patterns, trends, and contributing factors facilitating evidence-based decision-making and development and iteration of targeted interventions to promote responsible antibiotic use. Systematic data collection throughout the entire production cycle would also allow for a more accurate understanding of how antibiotic usage patterns vary across different stages of broiler production, recognizing the usage may change in response to bird age, disease risk, or management practices. Finally, we conducted our study in three out of 47 Kenyan counties, which may not fully represent the country’s semi-intensive poultry production. However, they are peri-urban counties where poultry farming is practiced, and the farm management practices in other peri-urban counties with similar rearing system are likely comparable. Therefore, the results from this study could be considered reflective of semi-intensive broiler poultry practices in Kenya.

Conclusion

Our study highlights poor biosecurity practices, low to moderate but highly variable mortality rates, and widespread use of antibiotics, mainly for prophylactic purposes, among semi-intensive broiler farmers in Kenya. Although our study did not find a direct link between biosecurity and antibiotic use, we did observe an association between certain biosecurity measures and mortality. These findings reveal a gap in farmers’ practices regarding the implementation of effective biosecurity measures and prudent antibiotic use.

Our findings provide insights that can guide the development of more comprehensive data collection methodologies, incorporating additional variables and practices. These insights can inform the design of targeted interventions and policies aimed at promoting responsible antibiotic stewardship and improving biosecurity measures within the poultry farming community. Lastly, many respondents in our study were women, and previous studies have highlighted that women frequently face structural barriers to accessing veterinary services, medicines, and critical information, hindering their ability to implement biosecurity and stewardship practices effectively [58]. As such, technical solutions to reducing AMU and AMR must be inclusive and equitable.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Department of Veterinary Services in Kajiado, Machakos and Kiambu counties for their support. We extend our gratitude to the farmers in these counties who allowed us to collect data on their farms, as well as the numerous enumerators who participated in the data collection.

Author contributions

N. K: Data curation, formal analysis, software, validation, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, visualization, D.M: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Data curation, formal analysis, software, validation, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, visualization, E.I: Investigation, Data curation, software, validation, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, visualization, J.N: Investigation, validation, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, V.H: Conceptualization, Methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, M.M: Conceptualization, Methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, S.N: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, data curation, formal analysis, software, validation, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, A.M: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, formal analysis, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Copenhagen University. This study was funded by the CGIAR One Health Initiative “protecting human health through one health approach”, which is supported by contributors to the CGIAR Trust Fund (https://www.cgiar.org/funders/). Additional support for Søren S. Nielsen was from the European Union’s Horizon Europe Project 10113646 EUPAHW.”

Data availability

Available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The collection of data adhered to the legal requirements of the Government of Kenya. Ethical approval for human data collection was obtained from the ILRI Institutional Research Ethics Committee (ILRI-IREC2022-34). Written informed consent was obtained from study participants.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Søren S. Nielsen and Arshnee Moodley are joint senior and corresponding authors.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Naomi P. Kemunto and Dishon M. Muloi share first authorship and contributed equally to this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Søren S. Nielsen, Email: saxmose@sund.ku.dk

Arshnee Moodley, Email: a.moodley@cgiar.org, Email: asm@sund.ku.dk.

References

- 1.Tang KL, Caffrey NP, Nóbrega DB, Cork SC, Ronksley PE, Barkema HW et al. Restricting the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals and its associations with antibiotic resistance in food-producing animals and human beings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet Health. 2017;1:e316–27. Available from: 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30141-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.O’ Neil Jim. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations the review on antimicrobial resistance. 2016. Available from: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final paper_with cover.pdf

- 3.WHO. World Health Organization-Antimicrobial resistance. 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance

- 4.WOAH. Ninth Annual Report on Antimicrobial Agents Intended for Use in Animals - WOAH - World Organisation for Animal Health. 2025. Available from: https://www.woah.org/en/document/ninth-annual-report-antimicrobial-agents-intended-for-use-in-animals/

- 5.Van Boeckel TP, Pires J, Silvester R, Zhao C, Song J, Criscuolo NG et al. Global trends in antimicrobial resistance in animals in low- and middle-income countries. Science (1979). 2019;365. Available from: 10.1126/science.aaw1944 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Omondi SO. Poultry Value Chain in Two Medium-Sized Cities in Kenya; Insights From Cluster Theory. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:601299. Available from: 10.3389/fvets.2022.601299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation (FAO)-FAOSTAT database. [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data

- 8.OECD-FAO. Organization for Economic Co-operation Development (OECD)-Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Agricultural Outlook 2021–2030. 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2021/07/oecd-fao-agricultural-outlook-2021-2030_31d65f37.html

- 9.FAO. Mapping supply and demand for animal-source foods to 2030, by T.P. Robinson & F. Pozzi. Animal Production and Health Working Paper. No. 2. Rome. 2011 [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/4/i2425e/i2425e.pdf

- 10.Mottet A, Tempio G. Global poultry production: current state and future outlook and challenges. Worlds Poult Sci J. 2017;73:245–56. Available from: 10.1017/S0043933917000071. [Google Scholar]

- 11.KNBS. 2019 Population and Housing Census - Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.knbs.or.ke/reports/kenya-census-2019/

- 12.Mbae R, Kimoro B, Kibor BT, Wilkes A, Odhong’ C, van Dijk S et al. The Livestock Sub-sector in Kenya’s NDC: A scoping of gaps and priorities. UNIQUE|Livestock sub-sector NDC report. Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases (GRA) & CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases (GRA) & CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS); 2020. Available from: 10568/110439.

- 13.Kariuki JW, Jacobs J, Ngogang MP, Howland O. Antibiotic use by poultry farmers in Kiambu County, Kenya: exploring practices and drivers of potential overuse. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2023;12:3. Available from: 10.1186/s13756-022-01202-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Mutua F, Kiarie G, Mbatha M, Onono J, Boqvist S, Kilonzi E et al. Antimicrobial Use by Peri-Urban Poultry Smallholders of Kajiado and Machakos Counties in Kenya. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;12:905. Available from: 10.3390/antibiotics12050905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Wilcox CH, Sandilands V, Mayasari N, Asmara IY, Anang A. A literature review of broiler chicken welfare, husbandry, and assessment. Worlds Poult Sci J. 2024;80:3–32. Available from: 10.1080/00439339.2023.2264824

- 16.Haque MH, Sarker S, Islam MS, Islam MA, Karim MR, Kayesh MEH et al. Sustainable Antibiotic-Free Broiler Meat Production: Current Trends, Challenges, and Possibilities in a Developing Country Perspective. Biology (Basel). 2020;9:1–24. Available from: 10.3390/biology9110411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Solano-Blanco AL, González JE, Medaglia AL. Production planning decisions in the broiler chicken supply chain with growth uncertainty. Operations Research Perspectives. 2023;10:100273. Available from: 10.1016/j.orp.2023.100273

- 18.Mehdi Y, Létourneau-Montminy MP, Gaucher ML, Chorfi Y, Suresh G, Rouissi T et al. Use of antibiotics in broiler production: Global impacts and alternatives. Anim Nutr. 2018;4:170–8. Available from: 10.1016/j.aninu.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Nyaga P. Poultry sector country review Kenya - Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) animal production and health division. 2007 [cited 2025 Jun 24]; Available from: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/951d138a-eb4a-4244-a66b-9b0fa997c834/content

- 20.FAO, Africa Sustainable L. 2050: Business models along the poultry value chain in Kenya– Evidence from Kiambu and Nairobi City Counties. Business models along the poultry value chain in Kenya. 2022; Available from: 10.4060/CB8190EN

- 21.Omiti JM, Okuthe SO. An overview of the poultry sector and status of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) in Kenya: Background paper. International Food Policy Research Institute; 2009. Available from: 10568/161820.

- 22.KNBS. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics - National agriculture production report. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 24]; Available from: https://www.knbs.or.ke/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/National-Agriculture-Production-Report-2024.pdf

- 23.Kemp SA, Pinchbeck GL, Fèvre EM, Williams NJ. A Cross-Sectional Survey of the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Antimicrobial Users and Providers in an Area of High-Density Livestock-Human Population in Western Kenya. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:727365. Available from: 10.3389/fvets.2021.727365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Muloi D, Fèvre EM, Bettridge J, Rono R, Ong’are D, Hassell JM et al. A cross-sectional survey of practices and knowledge among antibiotic retailers in Nairobi, Kenya. J Glob Health. 2019;9:010412. Available from: 10.7189/jogh.09.020412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Rware H, Monica KK, Idah M, Fernadis M, Davis I, Buke W et al. Examining antibiotic use in Kenya: farmers’ knowledge and practices in addressing antibiotic resistance. CABI Agriculture and Bioscience. 2024;5:1–15. Available from: 10.1186/s43170-024-00223-4

- 26.Ndukui JG, Gikunju JK, Aboge GO, Mbaria JM, Ndukui JG, Gikunju JK et al. Antimicrobial Use in Commercial Poultry Production Systems in Kiambu County, Kenya: A Cross-Sectional Survey on Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices. Open J Anim Sci. 2021;11:658–81. Available from: 10.4236/OJAS.2021.114045

- 27.FAO. Poultry development review - Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2013 [cited 2025 Jun 24]; Available from: https://www.fao.org/4/i3531e/i3531e.pdf

- 28.Government of Kenya-Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD). Registration of additives for use in animal nutrition. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 24]; Available from: https://vmd.go.ke/sites/default/files/2023-01/Guidelines for Registration of Feed Additives.pdf

- 29.Kiambi S, Mwanza R, Sirma A, Czerniak C, Kimani T, Kabali E et al. Understanding Antimicrobial Use Contexts in the Poultry Sector: Challenges for Small-Scale Layer Farms in Kenya. Antibiotics 2021, Vol 10, Page 106. 2021;10:106. Available from: 10.3390/ANTIBIOTICS10020106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Muloi DM, Ibayi EL, Murphy M, Njaramba J, Nielsen SS, Hoffmann V et al. FarmUSE: Assessment of antimicrobial use in poultry farms. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI. 2024. Available from: 10568/145014.

- 31.Hartung C, Anokwa Y, Brunette W, Lerer A, Tseng C, Borriello G. Open data kit: Tools to build information services for developing regions. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. 2010; Available from: 10.1145/2369220.2369236

- 32.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/

- 33.Gelaude P, Schlepers M, Verlinden M, Laanen M, Dewulf J. Biocheck.UGent: A quantitative tool to measure biosecurity at broiler farms and the relationship with technical performances and antimicrobial use. Poult Sci. 2014;93:2740–51. Available from: 10.3382/ps.2014-04002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Biocheck.UGentTM. About biosecurity| Biocheck.UGent. [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://biocheckgent.com/en/surveys

- 35.Textor J, van der Zander B, Gilthorpe MS, Liśkiewicz M, Ellison GT. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package ‘dagitty.’ Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1887–94. Available from: 10.1093/IJE/DYW341 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Carrique-Mas JJ, Trung NV, Hoa NT, Mai HH, Thanh TH, Campbell JI et al. Antimicrobial usage in chicken production in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015;62 Suppl 1:70–8. Available from: 10.1111/ZPH.12165 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Manishimwe R, Nishimwe K, Ojok L. Assessment of antibiotic use in farm animals in Rwanda. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2017;49:1101–6. Available from: 10.1007/s11250-017-1290-z [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Om C, McLaws ML, Antibiotics. Practice and opinions of Cambodian commercial farmers, animal feed retailers and veterinarians. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5:1–8. Available from: 10.1186/s13756-016-0147-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Donkor ES, Newman MJ, Yeboah-Manu D. Epidemiological aspects of non-human antibiotic usage and resistance: implications for the control of antibiotic resistance in Ghana. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2012;17:462–8. Available from: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02955.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Boamah V, Agyare C. Antibiotic Practices and Factors Influencing the Use of Antibiotics in Selected Poultry Farms in Ghana. J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;2. Available from: 10.4172/2472-1212.1000120

- 41.Azabo R, Dulle F, Mshana SE, Matee M, Kimera S. Antimicrobial use in cattle and poultry production on occurrence of multidrug resistant Escherichia coli. A systematic review with focus on sub-Saharan Africa. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:1000457. Available from: 10.3389/fvets.2022.1000457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.WHO. Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine: 6th revision- World Health Organization (WHO). 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/312266/9789241515528-eng.pdf?ua=1

- 43.Samuel M, Fredrick Wabwire T, Tumwine G, Waiswa P. Antimicrobial Usage by Small-Scale Commercial Poultry Farmers in Mid-Western District of Masindi Uganda: Patterns, Public Health Implications, and Antimicrobial Resistance of E. coli. Vet Med Int. 2023;2023:6644271. Available from: 10.1155/2023/6644271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Ibrahim N, Chantziaras I, Mohsin MAS, Boyen F, Fournié G, Islam SS et al. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of antimicrobial usage and biosecurity on broiler and Sonali farms in Bangladesh. Prev Vet Med. 2023;217. Available from: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2023.105968 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Van TTH, Yidana Z, Smooker PM, Coloe PJ. Antibiotic use in food animals worldwide, with a focus on Africa: Pluses and minuses. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;20:170–7. Available from: 10.1016/J.JGAR.2019.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Persoons D, Dewulf J, Smet A, Herman L, Heyndrickx M, Martel A et al. Antimicrobial use in Belgian broiler production. Prev Vet Med. 2012;105:320–5. Available from: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2012.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Wongsuvan G, Wuthiekanun V, Hinjoy S, Day NPJ, Limmathurotsakul D. Antibiotic use in poultry: a survey of eight farms in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:94–100. Available from: 10.2471/BLT.17.195834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Kasimanickam V, Kasimanickam M, Kasimanickam R. Antibiotics Use in Food Animal Production: Escalation of Antimicrobial Resistance: Where Are We Now in Combating AMR? Med Sci (Basel). 2021;9. Available from: 10.3390/MEDSCI9010014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Souillard R, Allain V, Dufay-Lefort AC, Rousset N, Amalraj A, Spaans A et al. Biosecurity implementation on large-scale poultry farms in Europe: A qualitative interview study with farmers. Prev Vet Med. 2024;224. Available from: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2024.106119 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Delpont M, Salazar LG, Dewulf J, Zbikowski A, Szeleszczuk P, Dufay-Lefort AC et al. Monitoring biosecurity in poultry production: an overview of databases reporting biosecurity compliance from seven European countries. Front Vet Sci. 2023;10:1231377. Available from: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1231377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Tilli G, Laconi A, Galuppo F, Mughini-Gras L, Piccirillo A. Assessing Biosecurity Compliance in Poultry Farms: A Survey in a Densely Populated Poultry Area in North East Italy. Animals (Basel). 2022;12. Available from: 10.3390/ANI12111409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Caudell MA, Dorado-Garcia A, Eckford S, Creese C, Byarugaba DK, Afakye K et al. Towards a bottom-up understanding of antimicrobial use and resistance on the farm: A knowledge, attitudes, and practices survey across livestock systems in five African countries. PLoS One. 2020;15. Available from: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Pham-Duc P, Cook MA, Cong-Hong H, Nguyen-Thuy H, Padungtod P, Nguyen-Thi H et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of livestock and aquaculture producers regarding antimicrobial use and resistance in Vietnam. PLoS One. 2019;14. Available from: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Truong DB, Doan HP, Doan Tran VK, Nguyen VC, Bach TK, Rueanghiran C et al. Assessment of Drivers of Antimicrobial Usage in Poultry Farms in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam: A Combined Participatory Epidemiology and Q-Sorting Approach. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6:431474. Available from: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Kayendeke M, Denyer-Willis L, Nayiga S, Nabirye C, Fortané N, Staedke SG et al. Pharmaceuticalised livelihoods: antibiotics and the rise of Quick Farming in peri-urban Uganda. J Biosoc Sci. 2023;55:995–1014. Available from: 10.1017/S0021932023000019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Figuié M, Batie C, Macuamule C, Cuinhane C, Goutard F. AMR as a Global and One Health Issue: the Challenge to Adapt a Global Strategy in Two Low- and Middle-income Countries, Mozambique and Vietnam. EuroChoices. 2024;23:72–7. Available from: 10.1111/1746-692X.12438

- 57.Schar D, Sommanustweechai A, Laxminarayan R, Tangcharoensathien V. Surveillance of antimicrobial consumption in animal production sectors of low- and middle-income countries: Optimizing use and addressing antimicrobial resistance. PLoS Med. 2018;15. Available from: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Emdin F, Galiè A, Moodley A, Van Rogers S. Gender and antimicrobial resistance: a conceptual framework for researchers working in livestock systems. Front Vet Sci. 2025;11:1456605. Available from: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1456605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.